Abstract

Global warming has intensified water scarcity, while excessive fertilizer use has caused soil acidification and limited nutrient availability. This study investigated the effects of biochar and chitosan xerogel on water spinach (Ipomoea aquatica Forsk.) growth under water- and fertilizer-deficient conditions. Individually, either biochar or chitosan xerogel provided limited improvement. However, the combined application of 4% biochar and 0.8% chitosan xerogel significantly restored plant performance. Under water deficiency, fresh, stem, and leaf weights increased by 1.2-, 1.3-, and 1.7-fold, while plant height and stem diameter rose by 1.2- and 1.3-fold. Similar improvements were observed under fertilizer deficiency, with up to 1.3-fold, 2.0-fold, and 1.4-fold increases in fresh, stem and leaf weight. Chlorophyll and β-carotene contents were also enhanced under both stress conditions. Additionally, the dual amendment improved uptake of nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), potassium (K), magnesium (Mg), and manganese (Mn), achieving growth comparable to optimal irrigation and fertilization. These findings demonstrate the synergistic potential of biochar and chitosan xerogel to enhance water and nutrient efficiency, supporting sustainable agriculture under resource limitations.

1. Introduction

Water is one of the most essential resources for sustaining agriculture and human livelihoods. Globally, 97.5% of the Earth’s water is seawater, leaving only 2.5% as freshwater. Of this limited freshwater supply, approximately 70% is used for agricultural purposes [1,2]. In 2016, approximately 933 million people, representing one-third of the global urban population, were affected by water scarcity. This number is projected to rise to between 1.7 and 2.4 billion by 2050 [3]. Taiwan has also experienced intermittent water shortages, particularly in 2015 and 2021, which resulted in irrigation restrictions that impacted agricultural production. Considering the essential role of agriculture in food security and rural livelihoods, improving water use efficiency is becoming increasingly critical under both current and anticipated resource constraints.

Fertilizers are also extensively applied to improve crop yield and quality. Between 1960 and 1995, global use of nitrogen and phosphorus fertilizers increased approximately 7-fold and 3.5-fold, respectively, and these figures are projected to rise by an additional 21 and 10 times by 2050. However, only 30% to 50% of applied nitrogen [4] and 10% to 20% of applied phosphorus [5] are effectively absorbed by crops. The remainder is often lost through leaching and surface runoff, leading to issues such as eutrophication and groundwater contamination. Consequently, improving fertilizer use efficiency, in parallel with conserving water resources, is essential for advancing sustainable agricultural practices and safeguarding environmental quality [6]. In this study, both water deficit and nutrient depletion were considered as key abiotic stress factors that limit crop productivity under global climate change. Global warming and the overexploitation of natural resources have exacerbated water scarcity, while excessive and unbalanced fertilizer use has resulted in soil acidification and nutrient leaching, leading to long-term fertility decline [7,8]. Consequently, enhancing soil water retention and nutrient efficiency has become central to sustainable agriculture.

Water spinach (Ipomoea aquatica Forsk.), a fast-growing leafy vegetable belonging to the Convolvulaceae family, is a staple summer crop in Taiwan and a rich source of bioactive compounds such as flavonoids and β-carotene [9]. Owing to its sensitivity to soil conditions and moisture availability, it has been widely used as a model crop for assessing plant uptake of heavy metals from contaminated soils [10]. In addition, I. aquatica demonstrates higher uptake efficiency for both ammonium and nitrate nitrogen compared to other species [11], making it an effective indicator crop for evaluating soil water and nutrient dynamics.

Biochar, a carbon-rich product derived from pyrolysis of biomass under limited oxygen conditions, is increasingly recognized as a multifunctional soil amendment. It is characterized by a high pH and porous structure [12,13]. The physicochemical properties of biochar, including yield, porosity, pH, and specific surface area, are influenced by the feedstock material and pyrolysis temperature [14,15]. Biochar application has been reported to improve soil water retention and increase bulk density [16,17], while also acting as a slow-release matrix for organic matter and nutrients [18]. As such, biochar holds significant promise for enhancing soil productivity and resource use efficiency in sustainable agriculture.

Chitin is a polysaccharide that constitutes a major structural component of the exoskeletons of crustaceans such as shrimp and crabs, as well as the cell walls of fungi and certain tissues of mollusks. It is recognized as the second most abundant natural polymer after cellulose [19]. Chitosan, which is derived from chitin through a deacetylation process, typically has a degree of deacetylation greater than 50%, enabling it to become soluble in dilute acid solutions [20]. In agricultural applications, chitosan has been employed for inducing plant defense responses, coating or disinfecting seeds, improving the post-harvest quality of horticultural products [21], and serving as a soil conditioner [22,23]. Wood vinegar, a byproduct of biomass pyrolysis, can act as a natural dilute acid capable of dissolving chitosan [24]. It also demonstrates potential for enhancing crop yield and quality [25,26] and exhibits antimicrobial and pesticidal activities [27]. As such, wood vinegar could serve as an environmentally friendly alternative to conventional chemical agents [28]. The phenolic compounds present in wood vinegar have been shown to inhibit bacterial growth at specific concentrations [29]. From previous studies, the combination of chitosan and wood vinegar may thus offer synergistic benefits for improving crop quality while also providing antimicrobial protection. Additionally, previous research has demonstrated that incorporating ammonium hydrogen phosphate into chitosan solutions prepared in acetic acid can result in the formation of a thermogelling system [30], suggesting potential for advanced formulations in agricultural applications. The combined effect of biochar and chitosan reported from the previous studies that significant yield gains under biochar–chitosan polymer composite amendments due to substantial slow-release properties to overcome excessive nutrient loss [31]. The nutrient retention behavior observed in our study corroborates previous work, which demonstrated that biochar–chitosan composites improved nutrient-use efficiency by up to 29% after 30 day under limited fertilizer input [32]. Fruit yield and quality increased significantly with increasing concentrations of chitosan and biochar [33]. This combined effect of biochar and chitosan offers a sustainable approach to improving crop resilience under limited water and nutrient availability, echoing the conceptual framework of sustainable agro-technologies [34].

Global warming and increasing human demand for resources have led to worsening water shortages, while excessive fertilizer use has resulted in soil acidification and a gradual global decline in fertilizer availability. Consequently, improving soil fertility and water retention has become a key focus for sustainable agricultural practices. Understanding the effects of different materials on plant growth is essential for optimizing crop yield and enhancing soil health. We hypothesize that the combined application of biochar and chitosan-based xerogel can synergistically enhance soil water retention, nutrient availability, and crop productivity under conditions of water and nutrient stress. The incorporation of biochar into the soil improves aeration and drainage properties. Concurrently, the application of chitosan contributes antimicrobial activity, supporting healthier plant growth. Furthermore, a key technique has been developed that involves adding ammonium hydrogen phosphate to chitosan hydrogel, enabling the formation of a water-retaining agent at ambient temperature. Phosphorus, a major macronutrient in fertilizers, is thus introduced in a water-soluble form. This multifunctional material is being evaluated for its ability to retain water and nutrients while maintaining favorable textural characteristics.

The aim of this study was to evaluate the synergistic effect of combining biochar and chitosan xerogel on water spinach under water or fertilizer stress. To achieve this, the research sought to determine the positive impact of this dual amendment on fresh biomass and yield, while simultaneously assessing the corresponding improvements in nutrient uptake. By comparing the combined treatment’s efficacy against single amendments and optimal growth conditions, the study aimed to confirm the synergistic benefit and highlight its practical importance as a sustainable strategy for enhancing crop performance while potentially reducing resource inputs. Collectively, this research sought to maximize plant vigor and nutrient efficiency in challenging agricultural settings.

Water spinach was selected as the experimental material due to its significant economic importance and nutritional value across Taiwan and other tropical regions, coupled with its short growth cycle and pronounced sensitivity to soil water and nutrient conditions. The experimental strategy was designed to systematically evaluate the effects of the amendments under defined stress levels. Initially, a quantitative number of plants were grown in a fixed volume of a peat-based substrate. Critical stress thresholds for water and fertilizer deficiency were established by treating the plants with varying irrigation volumes or nutrient concentrations to determine the point of impaired growth. Subsequently, the main experiment involved amending the substrate with biochar and chitosan xerogel, both individually and in combination, using defined dose ratios. Key plant growth parameters (PGPs), including fresh weight, stem weight, leaf weight, plant height, and stem diameter, were measured. Furthermore, plant physiological responses were assessed by quantifying leaf chlorophyll content and β-carotene content, while nutrient uptake was determined through elemental analysis of plant tissues. This framework allowed for a comprehensive understanding of how the combined amendments impact plant vigor, physiology, and nutrient acquisition under distinct water- or fertilizer-deficient states.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material and Growth Conditions

The test plant used in this study was Ipomoea aquatica Forsk. cv. Chungu Daye, a water spinach cultivar widely grown in Taiwan. Water spinach seeds of a commercial variety from Yunlin, Taiwan, were cultivated in the greenhouse at National Chung Hsing University. Square pots (20 × 20 × 10 cm) were filled with 600 g of dry peat-based substrate composed of peat, vermiculite, and perlite (3:1:1, v/v/v). Sixteen plants were grown per pot. Each square pot has a volume of approximately 4 L. Plants were watered daily, and commercial fertilizer (Hakaphos® Blue, Known-You seed Co., Ltd., Kaohsiung, Taiwan; COMPO Benelux N.V.; 4.0% ammonium nitrogen, 10.0% P2O5, 15.0% K2O, 2.0% MgO, 0.02% Zn, and 0.02% Cu) was applied every five days after the emergence of the first true leaf.

2.2. Preparation of Biochar

Mushroom waste bags were collected in Taichung, Taiwan, and then dispersed, ground and dried in an oven. Pellets was prepared using a small flat-die pelletizing machine (Fann chern Industrial Co., Ltd., Taichung, Taiwan), producing samples with a diameter of 0.8 cm and a length of ca. 3–5 cm. Biochar was produced using a quartz torrefaction reactor under nitrogen (1 L/min) at atmospheric pressure, with the following steps: (i) drying at 105 °C for 20 min, (ii) heating to 500 °C at 10 °C/min, and (iii) pyrolysis at 500 °C for 60 min. The biochar yield was 32.7%. The final product was ground into powder for use.

2.3. Preparation of Chitosan Xerogel

Wood vinegar is obtained by heat-treated the condensed liquid of Taiwan acacia (Acacia confusa) wood, which is then allowed to settle for 1 year and the supernatant liquid is collected and was kindly provided by Kunn Yih Wood Corporation Co., Ltd. in Yilan, Taiwan. Using shrimp shells and crab shells as raw materials, chitosan (Deacetylation ≥80%, ash content ca. 2%) were purchased from Charm & Beauty Co., Ltd., Taipei, Taiwan. The chitosan xerogel preparation, developed by the authors and referred from Nair et al. [30], involved dissolving chitosan (2.7% w/w) in 17.7% (w/w) wood vinegar at room temperature under stirring (450 rpm), followed by storage at 4 °C for one day. Diammonium hydrogen phosphate (1.3% w/v) was added and stirred at 500 rpm, followed by incubation at 4 °C for 6 h. The gel was dried at 40 °C for 3 days, ground, and sieved through a 1 mm mesh to obtain the xerogel powder (Supplemental Figure S1).

2.4. Experimental Design

The experiment was designed to evaluate the individual and combined effects of water management, fertilizer (Hakaphos® Blue), biochar, and chitosan xerogel on the growth and stress tolerance of water spinach under controlled conditions. The study was structured as a series of sequential experiments, each conducted under a completely randomized design (CRD) (Table 1). The first two experiments (Groups T1–T2) established the baseline water and fertilizer levels to define “control” and “deficit” conditions. Subsequent experiments (Groups T3–T6) examined the individual dose effects of biochar and chitosan xerogel under these deficit environments, while the final two experiments (Groups T7–T8) evaluated their combined (2 × 2) synergistic effects. Each treatment was replicated three times, with five plants per replicate, to ensure statistical reliability. Water volume and fertilizer concentration were set based on preliminary field recommendations for leafy vegetables in subtropical greenhouses. Biochar and chitosan xerogel were applied as soil amendments (treatments) at different application rates (0–12% w/w for biochar and 0–0.8% w/w for xerogel), mixed with the substrate prior to planting. T1 and T2 focused on baseline optimization of water and fertilizer input. T3 and T4 examined biochar dosage effects under fixed irrigation levels. T5 and T6 tested different xerogel concentrations under variable fertilizer levels. T7 and T8 combined biochar and xerogel treatments to assess potential synergistic effects. Plant height, leaf number, chlorophyll content, and fresh weight were recorded when the control plants reached 30–40 cm. This design allowed the evaluation of both individual and interactive effects of water, nutrients, and bioinputs, enabling identification of the most effective combination (notably T7-5 and T8-5, with 4% biochar and 0.4% xerogel) for improving soil water retention, nutrient efficiency, and plant growth performance.

Table 1.

Treatments and amendment combinations for plant growth.

Table 1 summarizes the factorial combinations of water, fertilizer, biochar, and xerogel levels. Each treatment code (e.g., T3-3 or T7-5) represents a unique substrate mixture replicated three times. The ranges were chosen to simulate typical subtropical vegetable cultivation scenarios and to identify optimal bioinput rates for sustainable production. Water (mL) refers to the volume applied per pot at each daily irrigation event, and Hakaphos® Blue (%) indicates the v/v dilution concentration of the fertilizer solution applied at each watering. The percentages of biochar and xerogel are expressed on a weight-per-weight (w/w) basis, calculated relative to the dry substrate mass (mass of amendment per mass of dry substrate).

2.5. Plant Growth Parameters

The experiment was conducted in the greenhouse facilities of National Chung Hsing University (NCHU), located in Taichung City, at geographic coordinates 24°7′13″ N 120°40′35″ E, with an elevation of ca. 70 m above sea level. The greenhouse conditions during the cultivation period (March 2020 to June 2021) were maintained within 20–30 °C temperature range, with 60–80% relative humidity, and controlled irrigation to simulate moderate water availability. These environmental parameters ensured consistent growth conditions for Ipomoea aquatica, minimizing the influence of external climatic variability while allowing for evaluation of soil amendment effects under semi-controlled subtropical conditions. PGPs were assessed using standardized methods [35]. Fresh weight was determined by averaging the total aboveground biomass from five randomly selected plants per treatment. Stem weight was calculated as the average mass of the stem portion (excluding leaves) from three plants. Leaf weight was measured by collecting and averaging the mass of the 2nd, 4th, and 6th newly developed leaves per plant. Plant height was recorded from the base to the apex of three representative plants. Stem diameter was measured at a position 1 cm above the first node using a digital caliper for precision. The Stem diameters were measure by Vernier caliper. Fresh weight, stem weight, and leaf weight were determined using an electronic balance. All measurements were performed by a single person. Each treatment group was replicated three times. For each replicate, samples were collected from the same cultivation pot and analyzed in triplicate. Total nitrogen (N) content was determined by the Kjeldahl method [36], which accurately quantifies organic and ammoniacal nitrogen, reflecting nitrogen assimilation efficiency. Phosphorus (P) and potassium (K) concentrations were measured after acid digestion using UV-Vis spectrophotometry (Cary 50, Varian, Mulgrave, Australia) and flame photometry, respectively, following the protocol of previous study [37]. Chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, and total chlorophyll were quantified spectrophotometrically according to Arnon (1949) to assess photosynthetic efficiency [38]. Soluble sugars were analyzed using the anthrone–sulfuric acid method [39], while total phenolic content was determined by the Folin–Ciocalteu assay [40], which estimates the antioxidant capacity and oxidative stress tolerance of plant tissues.

2.6. Mineral Element Analysis

Shoots were rinsed with 1% HCl and deionized water, dried at 100 °C (1 h) and 70 °C (3 days), and ground. For inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectroscopy (ICP-OES, PerkinElmer, Shelton, CT, USA) analysis, 0.25 g of sample was digested with 5 mL HNO3 (65%, Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) and 2 mL H2O2 (Choneye, Taipei, Taiwan) using a MarsXpress microwave system. NIST SRM 1573a (tomato leaves) was used as a standard. Diluted extracts were filtered (0.22 μm) before measurement [41]. For phosphorus, samples were diluted 400-fold with freshly prepared reagent and quantified using the molybdenum blue method at 840 nm via UV–Vis spectrophotometry (Cary 50, Varian, Mulgrave, Australia). R software (v4.1.0) was used for data visualization.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed within each experiment rather than across all groups, ensuring valid comparisons under consistent baseline conditions. The experiment was arranged in a CRD. All experimental data were subjected to one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) using SAS software 9.4 at a significance level of α = 0.05. Treatment means were compared using the least significant difference (LSD) test. Prior to ANOVA, data variability was examined, and the consistently low standard deviations across treatments indicated limited dispersion. Data normality and homogeneity of variance were visually assessed using histograms and residual plot inspections, which showed no obvious skewness or inconsistent variance patterns. Under these conditions, ANOVA is considered robust and appropriate for mean comparison in agricultural experiments.

3. Results

3.1. Optimizing Water and Fertilizer Regimes for Control and Deficit Conditions in Water Spinach

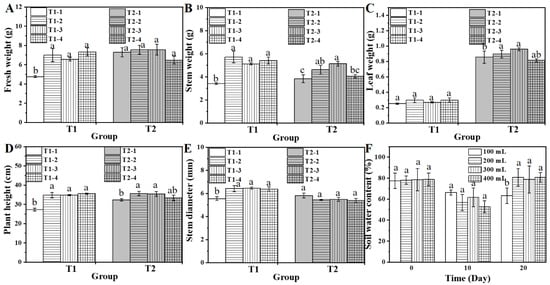

To determine the optimal water and fertilizer requirements for water spinach cultivation and to establish a basis for evaluating the combined effects of biochar and chitosan xerogel on spinach leaves under fertilizer deficiency, two preliminary experiments were conducted. In the water requirement experiment (Group T1, Figure 1A–E and Figure 2), water spinach was irrigated with 100, 200, 300, or 400 mL per pot, and substrate soil water content and plant growth PGPs, including fresh weight, stem weight, leaf weight, plant height, and stem diameter, were measured. As shown in Figure 1, water spinach irrigated with 200, 300, or 400 mL displayed similar growth patterns and appearances (T1-1 to T1-4), whereas plants receiving only 100 mL exhibited significantly lower plant weight, stem height, plant height, and stem diameter (T1-1). The soil water content measurements at 30 days confirmed a significant difference between the 100 mL group and the other treatments (Figure 1F). Consequently, subsequent experiments adopted 300 mL per pot as the control for normal watering, while 100 mL per pot was used to simulate water-deficient conditions.

Figure 1.

The effects of various water and fertilizer treatments on the fresh weight (A), stem weight (B), leaf weight (C), plant height (D), stem diameter (E), and soil moisture content (F) of the T1 treatment of water spinach. Lowercase letters (a, b, and c) indicate a significant difference at the p < 0.05 level, as determined by the ANOVA test.

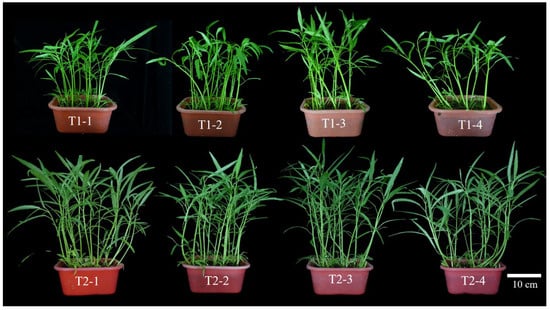

Figure 2.

Appearances of water spinach with varying amounts of water and fertilizer.

In the fertilizer requirement experiment (Group T2, Figure 1A–E and Figure 2), water spinach was treated with varying concentrations of Hakaphos® Blue (0.17%, 0.11%, 0.08%, and 0.07%). Plants receiving only 0.07% Hakaphos® Blue showed lower stem height, leaf weight, and plant height (T1-2). Normal growth was achieved with 0.11% Hakaphos® Blue, which was designated as the control treatment, whereas the 0.07% treatment was identified as the experimental condition for fertilizer deficiency. This foundation enables subsequent experiments to investigate the effect of combined biochar and chitosan xerogel treatment on water spinach under water and fertilizer deficiency.

3.2. Effect of Biochar Supplementation on Water Spinach Growth Under Water and Fertilizer Deficiency

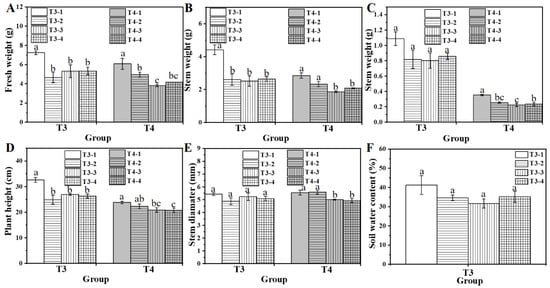

Under water deficiency, the control group (T3-1) recorded significantly higher fresh weight, stem weight, leaf weight, plant height, and better appearance than the water-deficient group (T3-2) (Figure 3A–D). However, the addition of biochar under water-deficient conditions did not significantly improve these parameters (T3-3 and T3-4) or soil water content compared to T3-2 (Figure 3F). Moreover, the fresh weight and leaf weight under fertilizer-deficient treatment (T4-2) were lower than those of the control group (T4-1), emphasizing the crucial role of adequate fertilizer concentration for water spinach growth. Biochar-treated groups (T4-3 and T4-4) exhibited slightly reduced fresh weight, stem weight, and stem diameter compared with those of the fertilizer-deficient group (T4-2). The findings indicate that elevated biochar levels did not promote growth in conditions of water or nutrient deficiency. Consequently, the selection of 4% biochar was made for subsequent combined treatment.

Figure 3.

Effect of biochar treatment on fresh weight (A), stem weight (B), leaf weight (C), plant height (D), stem diameter (E), and soil water content (F) of water spinach. Lowercase letters (a, b, and c) indicate a significant difference at the p < 0.05 level, as determined by the ANOVA test.

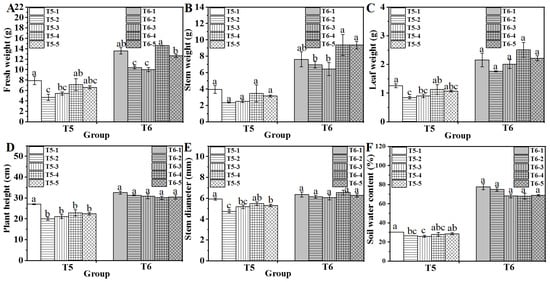

3.3. Chitosan Xerogel Treatment Mitigates Growth Inhibition in Water Spinach Under Water and Fertilizer Deficit Conditions

The appearance and impact of chitosan xerogel treatment on water spinach growth were assessed under water deficit (T5) and fertilizer deficit (T6) conditions (Figure 4 and Figure 5). Water deficit reduced growth, as the non-treated group T5-2 exhibited significantly lower PGPs than the control group T5-1. The application of 0.4% chitosan xerogel in T5-4 restored these PGPs to levels comparable to T5-1, suggesting that 0.4% chitosan xerogel mitigated the adverse effects of water deficit. Fertilizer deficiency also impaired growth, with the non-treated group T6-2 recording significantly lower PGPs than the control group T6-1. Chitosan xerogel treatments at 0.4% (T6-4) and 0.8% (T6-5) enhanced fresh weight, stem weight, and leaf weight compared to T6-2, indicating an improvement in growth potential under fertilizer deficit conditions. The investigation revealed that the treatment of soil with chitosan xerogel had no significant impact on its moisture content, as no substantial variations were observed between the treated and non-treated groups (Figure 5F). Consequently, 0.4% and 0.8% chitosan xerogel were selected for subsequent combined treatments (Figure 5).

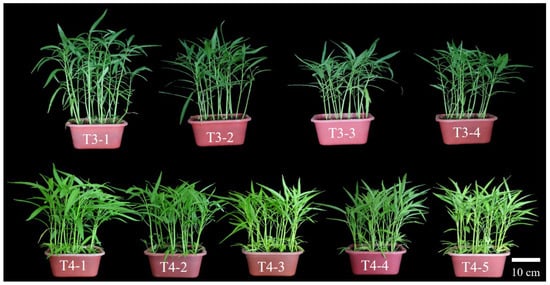

Figure 4.

Appearances of water spinach with biochar treatment or chitosan xerogel treatment.

Figure 5.

Effect of xerogel treatment on fresh weight (A), stem weight (B), leaf weight (C), plant height (D), stem diameter (E), and soil water content (F) of water spinach. Lowercase letters (a, b, and c) indicate a significant difference at the p < 0.05 level, as determined by the ANOVA test.

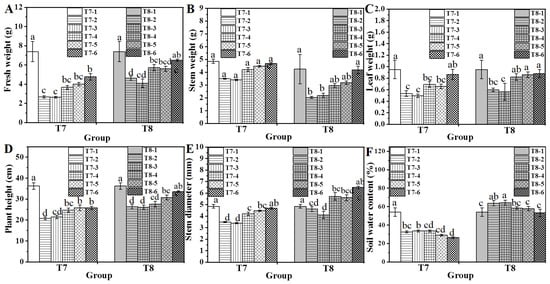

3.4. Combined Biochar and Chitosan Xerogel Treatment Restores Water Spinach Growth Under Deficit Conditions

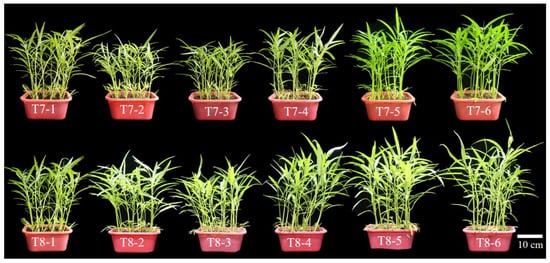

The combined treatment with biochar and chitosan xerogel was investigated for its effect on water spinach growth under water-deficient (T7) and fertilizer-deficient (T8) conditions (Figure 6). Under water deficit, the control group (T7-1) exhibited significantly higher growth potential than the untreated group (T7-2). Biochar alone (T7-3) did not improve growth compared to T7-2, while the application of 0.4% chitosan xerogel in groups T7-4 and T7-5 significantly increased PGPs relative to T7-2. Despite its soil moisture content being significantly lower (Figure 6F), the 0.8% chitosan xerogel combined treatment (T7-6) produced higher fresh weight and leaf weight than the 0.4% treatment (T7-5). The T7-5 and T7-6 plants showed better appearance than others (Figure 7). These results suggest that a higher chitosan xerogel concentration might benefit plant growth under water deficiency.

Figure 6.

Effect of xerogel/biochar combination treatment on fresh weight (A), stem weight (B), leaf weight (C), plant height (D), stem diameter (E), and soil water content (F) of water spinach. Lowercase letters (a, b, c, and d) indicate a significant difference at the p < 0.05 level, as determined by the ANOVA test.

Figure 7.

Appearances of water spinach with biochar and chitosan xerogel combined treatment.

In the fertilizer-deficient environment, the control group (T8-1) achieved significantly higher PGPs than those of the untreated group (T8-2) (Figure 6 and Figure 7). Biochar alone (T8-3) did not alter growth parameters relative to T8-2. However, the application of chitosan xerogel (T8-4) significantly improved all measured growth parameters compared to T8-2 (Figure 6). The combined treatment (T8-6) resulted in the highest PGPs comparable to T8-1 (Figure 6). In fertilizer-deficient substrates, the addition of chitosan xerogel was particularly effective in increasing the stem diameter of water spinach (T8-4, 5, and 6). Soil moisture content in groups T8-4, T8-5, and T8-6 was similar to fertilizer-sufficient control (T8-1) (Figure 6F). Nevertheless, the stem diameter exhibited a significant increase in comparison with that of T8-1, thereby suggesting that the incorporation of a xerogel composed of chitosan may be an effective solution to counteract the detrimental effects of fertilizer deficiency and promote plant growth. Additionally, the appearances of water spinach varied depending on the applied treatment (Figure 6). These results demonstrated that the combined application of 0.8% chitosan xerogel and 4% biochar restored growth potential under both water and fertilizer deficit conditions to levels similar to those in normal growing environments, suggesting that this treatment could improve substrate culture efficiency while reducing water and fertilizer usage in agricultural production under climate change conditions (Figure 6 and Figure 7).

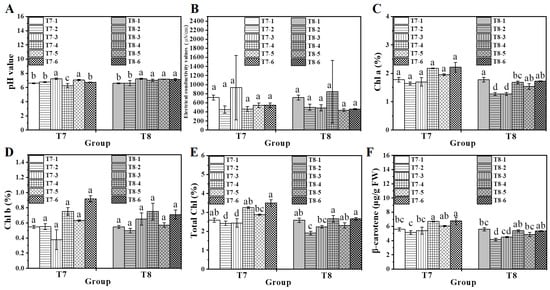

3.5. Effect of Biochar and Chitosan Xerogel Combined Treatment on Elements of Water Spinach

Substrate pH and conductivity values remained neutral across all treatments, indicating that the addition of biochar and chitosan xerogel did not alter substrate properties (Figure 8A,B). Chlorophyll and β-carotene contents in spinach leaves were subsequently analyzed (Figure 7). Under water-deficient conditions, the composite treatments of 0.4% chitosan xerogel (T7-5) and 0.8% chitosan xerogel combined with 4% biochar (T7-6) yielded significantly higher levels of chlorophyll and β-carotene in comparison to the untreated hydric-deficient group (T7-2) and the biochar-only treatment (T7-3) (Figure 8C–F).

Figure 8.

The growing medium of pH values (A) and electrical conductivity values (B) of water spinach. The chlorophyll a (C), chlorophyll b (D), total chlorophyll (E), and β-carotene (F) of water spinach planted in xerogel/biochar combination treatment medium. Lowercase letters (a, b, c, and d) indicate a significant difference at the p < 0.05 level, as deter-mined by the ANOVA test.

Under fertilizer-deficient conditions, the composite treatments with 0.4% chitosan xerogel (T8-5) and 0.8% chitosan xerogel combined with 4% biochar (T8-6) resulted in chlorophyll and β-carotene levels comparable to those of the control group (T8-1) and higher than those observed in the biochar-only treatment (T8-3) (Figure 7). These findings suggested that the combined treatment enhanced nutrient uptake, improved photosynthetic efficiency, and increased β-carotene content in spinach leaves under both water-deficient and fertilizer-deficient conditions.

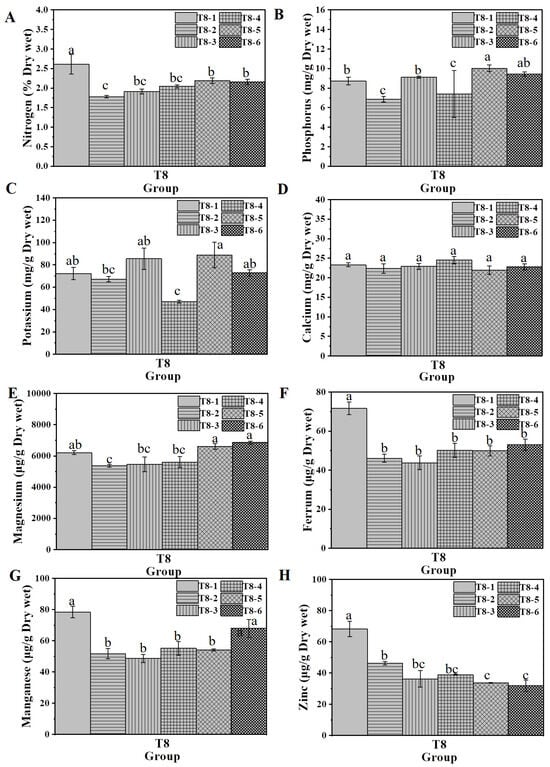

The effects of combined biochar and chitosan xerogel treatment on nutrient uptake in water spinach grown under fertilizer-deficient conditions (T8) were examined (Figure 8). In the fertilizer-deficient environment, the control group (T8-1) exhibited significantly higher concentrations of nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium, manganese, ferrum, manganese, and zinc compared to the fertilizer-deficient group (T8-2), indicating that fertilizer deficiency adversely affected the uptake of these essential nutrients. The biochar-alone treatment (T8-3) resulted in a significantly higher P and K concentration compared to T8-2 (Figure 8B,C). In contrast, the chitosan xerogel treatment alone (T8-4) reduced the K concentration relative to T8-2 (Figure 8C). The combined treatments, T8-5 (0.4% chitosan xerogel with 4% biochar) and T8-6 (0.8% chitosan xerogel with 4% biochar), yielded higher concentrations of nitrogen, phosphorus, magnesium, and manganese than T8-2, demonstrating enhanced nutrient uptake (Figure 8A–C,E). Moreover, the phosphorus concentration in T8-5 and the manganese concentration in T8-6 were higher than those in the control group (T8-1), indicating that the combined treatment can enhance the uptake of phosphorus and manganese by plants under nutrient-deficient conditions compared to normal fertilization (Figure 8C,E). Overall, the combination of 0.8% chitosan xerogel and 4% biochar significantly increased the contents of nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium, magnesium, and manganese in water spinach, which could effectively improve fertilizer efficiency and reduce fertilizer consumption.

4. Discussion

Previous studies consistently demonstrate that biochar addition can significantly enhance water holding capacity in coarse-textured soils, such as sandy or sandy loam [16,42,43]. This effect, however, is often reported to diminish as the clay content of the soil increases, given the already high moisture-holding capacity of fine-textured substrates [44]. Consistent with this literature, our study, which used peat as the main substrate (exhibiting a high intrinsic water-holding capacity of 229.4% (Figure S2A), showed that adding biochar alone, or chitosan xerogel alone, did not immediately or significantly increase substrate water content during early growth stages (Figure 3F and Figure 4). The beneficial effects on water retention only became apparent after 120 days by adding both biochar and chitosan xerogel (Figure S2B), suggesting that the substrate’s intrinsic properties masked the individual benefits of each amendment initially.

However, the mechanism for drought tolerance appears distinct from simple water retention in the substrate. Under water-deficient conditions, the application of chitosan xerogel alone was still able to restore plant vigor (Group T5, Figure 5), while biochar alone was not effective (Group T3, Figure 3). This aligns with literature suggesting that chitosan-based materials can benefit drought-stressed plants through physiological responses beyond external moisture control. For instance, the foliar application of acetic acid-dissolved chitosan has been shown to enhance proline content (an osmotic regulator), essential oil accumulation, and dry biomass in drought-stressed plants like Thymus daenensis [45]. Our results suggest that even in a high water-retention substrate, the chitosan xerogel provides a direct drought mitigation benefit to the plant, potentially by regulating internal water balance or stress pathways, as observed in other studies.

The literature widely supports that biochar can reduce nitrogen leaching and improve overall nutrient retention in soil [43,46,47], along with increasing the uptake of phosphorus (P) and potassium (K) [48,49]. Our findings partially align with this, suggesting a nutrient stabilization and buffering role for biochar. Specifically, although biochar application alone did not significantly improve overall plant biomass under nutrient-deficient conditions, it successfully maintained P and K contents in the plant tissues at levels comparable to the normal control (T8-3; Figure 7). This indicates that the presence of biochar was critical in retaining these nutrients in a plant-available form within the rhizosphere, preventing them from being lost.

Conversely, the application of chitosan xerogel alone (a composite of chitosan and wood vinegar) under fertilizer-deficient conditions enhanced water spinach fresh weight and stem weight (Figure 4). However, this growth promotion was not accompanied by a significant increase in the internal concentrations of mineral nutrients (T8-4; Figure 9). This result contrasts with the mechanism often reported for mineral amendments and suggests a growth-promoting effect independent of enhanced nutrient uptake. This could be related to chitosan’s known role in regulating plant hormone levels, promoting root development, or improving photosynthetic pigment biosynthesis and antioxidant activity [20,50,51], which are all physiological mechanisms that can enhance vegetative growth without a proportional increase in nutrient concentration. Furthermore, wood vinegar, a component of the xerogel, has been independently shown to increase the productivity of fruit/seeds [25,26] and enhance vegetative growth [52,53]. The combined application of biochar and chitosan xerogel exhibited a strong synergistic effect, significantly restoring plant growth and photosynthetic function under stress. This dual treatment enhanced nutrient uptake (N, P, K, Mg, Mn) and enabled comparable yields with reduced fertilizer and water input, highlighting its potential for sustainable and cost-efficient crop production.

Figure 9.

The plant elements (A) nitrogen, (B) phosphorus, (C) potassium, (D) calcium, (E) manganese, (F) ferrum, (G) manganese, and (H) zinc of water spinach planted in xerogel/biochar T8 combination treatment substrate. Lowercase letters (a, b, and c) indicate a significant difference at the p < 0.05 level, as determined by the ANOVA test.

This synergistic outcome can be directly attributed to the complementary roles that biochar and chitosan xerogel play in optimizing the soil–plant interface, a concept well-supported by scientific literature. The biochar primarily acts on the physical structure of the substrate; it is well-documented to improve soil structure by increasing porosity and aeration, thereby enhancing root penetration and overall root access to resources [54]. Simultaneously, the chitosan xerogel primarily addresses moisture and nutrient accessibility at the micro-level. As a hydrophilic polymer, it retains moisture near the root zone [55,56], which is absolutely vital for nutrient dissolution and the mass flow of nutrients to the root surface, particularly in drought-stressed environments. Furthermore, the inherent cationic properties of chitosan facilitate the adsorption and retention of key anions (such as nitrate and phosphate) and other cations, effectively stabilizing these nutrients in the rhizosphere and preventing leaching [57,58].

Together, these two amendments are theorized to function as a sophisticated controlled-release nutrient matrix. The biochar serves as a stable, high-surface-area sorbent, while the chitosan xerogel acts as a water-retaining, pH-sensitive polymer. This combination ensures the sustained availability of essential minerals, even under the low-input conditions of the deficient treatments. This combined mechanism, which enhances both the physical environment and the chemical accessibility of nutrients, provides a strong physiological basis for the observed superior plant performance under stress, ultimately explaining the robust recovery of growth and nutrient status.

The application of biochar and chitosan xerogel demonstrated distinct properties in enhancing stress tolerance of water spinach under water and fertilizer deficiency. Biochar improved soil aeration and structure but showed limited benefit under severe stress, as excessive biochar (≥8%) failed to enhance plant growth or soil moisture retention. Similar findings have been reported by previous study [59], indicating that biochar’s positive effect diminishes when water or nutrient availability is critically. In contrast, chitosan xerogel at concentrations of 0.4–0.8% effectively alleviated growth inhibition, restoring plant biomass and morphological traits to near-control levels. This improvement can be attributed to chitosan’s osmotic regulation, nutrient chelation, and biostimulant properties, which enhance plant resilience under abiotic stress [60]. The study was conducted in Taiwan’s subtropical region, where vegetable cultivation frequently faces intermittent drought and uneven rainfall, leading to water and nutrient stress. The combined use of biochar and chitosan therefore presents a sustainable soil amendment strategy, improving stress tolerance and stabilizing yield performance under the climatic variability characteristic of subtropical agriculture. Based on the findings of this study, the addition of biochar and chitosan xerogel to the soil can restore the growth vigor of water spinach under conditions of water or fertilizer deficiency.

These results suggest that the incorporation of appropriate amounts of biochar and chitosan xerogel into the soil during commercial production may achievement of comparable yields under reduced fertilizer application and water usage, thereby potentially leading to cost savings. The combination of bioinputs, such as biochar, chitosan, beneficial water and fertilizers efficiently, plays a vital role in advancing sustainable agriculture by improving soil health, enhancing nutrient-use efficiency, and reducing dependence on synthetic agrochemicals. The integration of bioinputs represents a sustainable agricultural strategy that simultaneously addresses soil degradation, water scarcity, and nutrient inefficiency while valorizing biowastes. This holistic approach supports both productivity and environmental protection, fulfilling the goals of climate-resilient and resource-efficient agriculture.

Future research will extend this study from controlled greenhouse conditions to open-field environments to validate the long-term agronomic and ecological performance of the biochar–chitosan system. In field applications, biochar (4%) is expected to enhance soil water retention, aeration, and nutrient holding capacity, while chitosan xerogel (0.4–0.8%) may act as a biodegradable moisture regulator that improves microbial activity and mitigates drought-induced stress. These synergistic effects are anticipated to stabilize vegetable yield and improve soil fertility under subtropical climatic variability. The next research phase will include multi-season field trials to evaluate productivity, soil health, and carbon sequestration potential.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, this study successfully demonstrated the following key findings and their broader implications: (1) Synergistic Growth Enhancement: The co-application of biochar and self-formulated chitosan xerogel exhibited synergistic effects on water spinach growth and physiology, significantly increasing key parameters like fresh weight, stem diameter, and pigment content (chlorophyll and β-carotene). This dual-amendment strategy offers a potent method for optimizing crop performance that is superior to the use of either component alone. (2) Improved Nutrient Use Efficiency: The combined treatment enhanced the plants’ ability to acquire and utilize essential nutrients, leading to elevated tissue concentrations of N, P, K, Mg, and Mn even under fertilizer-deficient conditions. This suggests a viable pathway for reducing reliance on synthetic fertilizers, thereby supporting more sustainable and cost-effective agricultural production. (3) Enhanced Environmental Resilience: The significant improvements in growth and physiological performance were maintained under both water-deficient and fertilizer-deficient conditions, even in a high-water-retention substrate. These results highlight the potential of this integrated amendment to enhance resource use efficiency and plant resilience in suboptimal environments. (4) Implications for sustainable agriculture: The findings support the integration of chitosan xerogel and biochar as a sustainable, low-input strategy to enhance crop productivity and maintain yield stability. This strategy is particularly relevant for mitigating the effects of climate change and can be tailored for semi-arid regions or controlled-environment cultivation systems where maintaining optimal soil water and nutrient balance is critical.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/horticulturae11121448/s1, Figure S1. The process of chitosan xerogel preparation. Figure S2. The (A) water-holding and (B) water-retention capacities of substrates with biochar and chitosan xerogel.

Author Contributions

I.-C.P.: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Supervision, Writing—original draft. C.-A.J.: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Writing—original draft. W.-Y.C.: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Validation, Writing—review & editing. Y.-C.C.: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Writing—review & editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Science and Technology Council (Taiwan) (113-2313-B-005-035-MY3 and 114-2321-B-005-006-), Ministry of Agriculture (Taiwan) (114AS-14.1.2-RS-06 and 110AS-17.1.2-ST-a3), and ENABLE (ENgineering in Agriculture Biotech LEadership) Center of National Chung Hsing University (114ST001B and 113ST001D). This work was also financially supported in part by the Advanced Plant and Food Crop Biotechnology Center from the Featured Areas Research Center Program within the framework of the Higher Education Sprout Project by the Ministry of Education (MOE) in Taiwan.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| RDF | Refuse derived fuels |

| PGPs | Plant growth parameters |

| LSD | Least significant difference |

References

- Kim, Y.; Lee, W.-G. Seawater and Its Resources. In Seawater Batteries: Principles, Materials and Technology; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2022; pp. 1–35. [Google Scholar]

- Flörke, M.; Kynast, E.; Bärlund, I.; Eisner, S.; Wimmer, F.; Alcamo, J. Domestic and Industrial Water Uses of the Past 60 Years as a Mirror of Socio-Economic Development: A Global Simulation Study. Glob. Environ. Change 2013, 23, 144–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Liu, Z.; Wu, J.; Pan, X.; Fang, Z.; Li, J.; Bryan, B.A. Future Global Urban Water Scarcity and Potential Solutions. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 4667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassman, K.G.; Dobermann, A.; Walters, D.T. Agroecosystems, Nitrogen-Use Efficiency, and Nitrogen Management. AMBIO J. Hum. Environ. 2002, 31, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, T.L.; Johnston, A.E. Phosphorus Use Efficiency and Management in Agriculture. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2015, 105, 275–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bijay-Singh; Craswell, E. Fertilizers and Nitrate Pollution of Surface and Ground Water: An Increasingly Pervasive Global Problem. SN Appl. Sci. 2021, 3, 518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanter, D.R.; Del Grosso, S.; Scheer, C.; Pelster, D.E.; Galloway, J.N. Why future nitrogen research needs the social sciences. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2020, 47, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.H.; Liu, X.J.; Zhang, Y.; Shen, J.L.; Han, W.X.; Zhang, W.F.; Christie, P.; Goulding, K.W.T.; Vitousek, P.M.; Zhang, F.S. Significant Acidification in Major Chinese Croplands. Science 2010, 327, 1008–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, H.; Xie, B.; Ma, S.; Zhu, X.; Fan, G.; Pan, S. Evaluation of Antioxidant Activities of Principal Carotenoids Available in Water Spinach (Ipomoea aquatica). J. Food Compos. Anal. 2011, 24, 288–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Q.; Wong, M.H.; Huang, L.; Ye, Z. Effects of Cultivars and Water Management on Cadmium Accumulation in Water Spinach (Ipomoea aquatica Forsk.). Plant Soil 2015, 391, 33–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jampeetong, A.; Brix, H.; Kantawanichkul, S. Effects of Inorganic Nitrogen Forms on Growth, Morphology, Nitrogen Uptake Capacity and Nutrient Allocation of Four Tropical Aquatic Macrophytes (Salvinia cucullata, Ipomoea aquatica, Cyperus involucratus and Vetiveria zizanioides). Aquat. Bot. 2012, 97, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, P.J.F. Structure of Non-Graphitising Carbons. Int. Mater. Rev. 1997, 42, 206–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Zwieten, L.; Kimber, S.; Morris, S.; Chan, K.Y.; Downie, A.; Rust, J.; Joseph, S.; Cowie, A. Effects of Biochar from Slow Pyrolysis of Papermill Waste on Agronomic Performance and Soil Fertility. Plant Soil 2010, 327, 235–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jindo, K.; Mizumoto, H.; Sawada, Y.; Sanchez-Monedero, M.A.; Sonoki, T. Physical and chemical characterization of biochars derived from different agricultural residues. Biogeosciences 2014, 11, 6613–6621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Chong Lua, A. Characterization of chars pyrolyzed from oil palm stones for the preparation of activated carbons. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 1998, 46, 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kammann, C.I.; Linsel, S.; Gößling, J.W.; Koyro, H.-W. Influence of biochar on drought tolerance of Chenopodium quinoa Willd and on soil–plant relations. Plant Soil 2011, 345, 195–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Dugan, B.; Masiello, C.A.; Gonnermann, H.M. Biochar particle size, shape, and porosity act together to influence soil water properties. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0179079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Xiong, X.; He, M.; Xu, Z.; Hou, D.; Zhang, W.; Ok, Y.S.; Rinklebe, J.; Wang, L.; Tsang, D.C.W. Roles of biochar-derived dissolved organic matter in soil amendment and environmental remediation: A critical review. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 424, 130387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinaudo, M. Chitin and chitosan: Properties and applications. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2006, 31, 603–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillai, C.K.S.; Paul, W.; Sharma, C.P. Chitin and chitosan polymers: Chemistry, solubility and fiber formation. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2009, 34, 641–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafari, L.; Shamekh, M.R.; Abdollahi, F.; Hamid, R. Elicitor potential of chitosan and its derivatives to enhancing greenhouse tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum Mill.) performance under deficit irrigation conditions. Sci. Hortic. 2025, 349, 114259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Faqir, Y.; Chai, Y.; Wu, S.; Luo, T.; Liao, S.; Kaleri, A.R.; Tan, C.; Qing, Y.; Kalhoro, M.T.; et al. Chitosan Microspheres-Based Controlled Release Nitrogen Fertilizers Enhance the Growth, Antioxidant, and Metabolite Contents of Chinese Cabbage. Sci. Hortic. 2023, 308, 111542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamta, S.; Vimal, V.; Verma, S.; Gupta, D.; Verma, D.; Nangan, S. Recent Development of Nanobiomaterials in Sustainable Agriculture and Agrowaste Management. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2024, 56, 103050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; He, P.; Kang, H.; Li, X. Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Effects of Edible Coating Based on Chitosan and Bamboo Vinegar in Ready to Cook Pork Chops. LWT 2018, 93, 470–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mungkunkamchao, T.; Kesmala, T.; Pimratch, S.; Toomsan, B.; Jothityangkoon, D. Wood Vinegar and Fermented Bioextracts: Natural Products to Enhance Growth and Yield of Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.). Sci. Hortic. 2013, 154, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, K.; Gu, S.; Liu, J.; Luo, T.; Khan, Z.; Zhang, K.; Hu, L. Wood vinegar as a complex growth regulator promotes the growth, yield, and quality of rapeseed. Agronomy 2021, 11, 510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, X.; Qiu, L.; Luo, S.; Kang, K.; Zhu, M.; Yao, Y. Chemical Constituents and Antimicrobial Activity of Wood Vinegars at Different Pyrolysis Temperature Ranges Obtained from Eucommia Ulmoides Olivers Branches. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 40941–40949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grewal, A.; Abbey, L.; Gunupuru, L.R. Production, Prospects and Potential Application of Pyroligneous Acid in Agriculture. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2018, 135, 152–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, R.; Cui, E.-L.; Hu, G.-Q.; Zhu, M.-Q. The Composition, Physicochemical Properties, Antimicrobial and Antioxidant Activity of Wood Vinegar Prepared by Pyrolysis of Eucommia ulmoides Oliver Branches under Different Refining Methods and Storage Conditions. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2022, 178, 114586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, L.S.; Starnes, T.; Ko, J.-W.K.; Laurencin, C.T. Development of injectable thermogelling chitosan–inorganic phosphate solutions for biomedical applications. Biomacromolecules 2007, 8, 3779–3785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafique, M.I.; Al-Wabel, M.I.; Al-Farraj, A.S.F.; Ahmad, M.; Aouak, T.; Al-Swadi, H.A.; Mousa, M.A. Incorporation of biochar and semi-interpenetrating biopolymer to synthesize new slow release fertilizers and their impact on soil moisture and nutrients availability. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 9563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Yang, F.; Xiang, K.; Chen, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; Sun, J.; Li, Y. A Multifunctional Microspheric Soil Conditioner Based on Chitosan-Grafted Poly(acrylamide-co-acrylic acid)/Biochar. Langmuir 2022, 38, 5717–5729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kayes, A.; Araf, T.; Mustaki, S.; Islam, N.; Choudhury, S. Effects of biochar and chitosan on morpho-physiological, biochemical and yield traits of water-stressed tomato plants. Int. J. Agric. Food Sci. 2024, 8, 01–09. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qaisi, A.M.; Al Tawaha, A.R.; Imran; Al-Rifaee, M.d. Effects of Chitosan and Biochar-Mended Soil on Growth, Yield and Yield Components and Mineral Composition of Fenugreek. Gesunde Pflanz. 2023, 75, 625–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, G.C. The Quantitative Analysis of Plant Growth; University of California Press: Oakland, CA, USA, 1972; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Bremner, J.M. Determination of nitrogen in soil by the Kjeldahl method. J. Agric. Sci. 1960, 55, 11–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reitemeier, R.F. Methods of analysis for soils, plants, and waters. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1963, 27, iv. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnon, D.I. Copper enzymes in isolated chloroplasts. Polyphenoloxidase in Beta Vulgaris. Plant Physiol. 1949, 24, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodge, J.E. Determination of reducing sugars and carbohydrates. Carbohydr. Chem. 1962, 1, 380–394. [Google Scholar]

- Singleton, V.L.; Rossi, J.A. Colorimetry of total phenolics with phosphomolybdic-phosphotungstic acid reagents. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 1965, 16, 144–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanmugam, V.; Lo, J.-C.; Wu, C.-L.; Wang, S.-L.; Lai, C.-C.; Connolly, E.L.; Huang, J.-L.; Yeh, K.-C. Differential expression and regulation of iron-regulated metal transporters in Arabidopsis halleri and Arabidopsis thaliana—The role in zinc tolerance. New Phytol. 2011, 190, 125–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Wang, Z.; Deng, X.; Zhao, J.; Luo, Y.; Novak, J.; Herbert, S.; Xing, B. Characteristics and Nutrient Values of Biochars Produced from Giant Reed at Different Temperatures. Bioresour. Technol. 2013, 130, 463–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, M.; Hastings, M.G.; Ryals, R. Soil Carbon and nitrogen dynamics in two agricultural soils amended with manure-derived biochar. J. Environ. Qual. 2019, 48, 727–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnes, R.T.; Gallagher, M.E.; Masiello, C.A.; Liu, Z.; Dugan, B. Biochar-induced changes in soil hydraulic conductivity and dissolved nutrient fluxes constrained by laboratory experiments. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e108340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emami Bistgani, Z.; Siadat, S.A.; Bakhshandeh, A.; Ghasemi Pirbalouti, A.; Hashemi, M. Interactive effects of drought stress and chitosan application on physiological characteristics and essential oil yield of Thymus daenensis Celak. Crop J. 2017, 5, 407–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghizadeh-Toosi, A.; Clough, T.J.; Sherlock, R.R.; Condron, L.M. Biochar adsorbed ammonia is bioavailable. Plant Soil 2012, 350, 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kammann, C.I.; Schmidt, H.-P.; Messerschmidt, N.; Linsel, S.; Steffens, D.; Müller, C.; Koyro, H.-W.; Conte, P.; Joseph, S. Plant growth improvement mediated by nitrate capture in co-composted biochar. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 11080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Sun, J.; Shao, H.; Chang, S.X. Biochar Had Effects on Phosphorus Sorption and Desorption in Three Soils with Differing Acidity. Ecol. Eng. 2014, 62, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.; Halder, M.; Siddique, M.A.B.; Razir, S.A.A.; Sikder, S.; Joardar, J.C. Banana peel biochar as alternative source of potassium for plant productivity and sustainable agriculture. Int. J. Recycl. Org. Waste Agric. 2019, 8, 407–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Han, W.; Wang, J.; Qian, Y.; Saito, M.; Bai, W.; Song, J.; Lv, G. Functions of Oligosaccharides in Improving Tomato Seeding Growth and Chilling Resistance. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2022, 41, 535–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Barman, K.; Siddiqui, M.W. 9—Chitosan: Properties and roles in postharvest quality preservation of horticultural crops. In Eco-Friendly Technology for Postharvest Produce Quality; Siddiqui, M.W., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016; pp. 269–296. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, X.; Wang, Z.; Meki, K.; Wang, X.; Liu, B.; Zheng, H.; You, X.; Li, F. Effect of co-application of wood vinegar and biochar on seed germination and seedling growth. J. Soils Sed. 2019, 19, 3934–3944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosakul, P.; Kantachote, D.; Saritpongteeraka, K.; Phuttaro, C.; Chaiprapat, S. Upgrading industrial effluent for agricultural reuse: Effects of digestate concentration and wood vinegar dosage on biosynthesis of plant growth promotor. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 14589–14600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laine, J.; Simoni, S.; Calles, R. Preparation of activated carbon from coconut shell in a small scale cocurrent flow rotary kiln. Chem. Eng. Commun. 1991, 99, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, J.; Wang, Z.; Hu, Q. Chitosan Hydrogel Structure Modulated by Metal Ions. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 36005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-C.; Chen, Y.-H. Thermo and pH-responsive methylcellulose and hydroxypropyl methylcellulose hydrogels containing K2SO4 for water retention and a controlled-release water-soluble fertilizer. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 655, 958–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamari, A.; Pulford, I.D.; Hargreaves, J.S.J. Chitosan as a potential amendment to remediate metal contaminated soil—A characterisation study. Colloids Surf. B. Biointerfaces 2011, 82, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jóźwiak, T.; Filipkowska, U.; Szymczyk, P.; Mielcarek, A. Sorption of nutrients (orthophosphate, nitrate III and V) in an equimolar mixture of P–PO4, N–NO2 and N–NO3 using chitosan. Arab. J. Chem. 2019, 12, 4104–4117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, A.; Sharma, R.; Kumar, A.; Sepehya, S. Biochar as a means to improve soil fertility and crop productivity: A review. J. Plant Nutr. 2022, 45, 2380–2388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, S.-C.; Chandrasekaran, M. Chitosan and chitosan nanoparticles induced expression of pathogenesis-related proteins genes enhances biotic stress tolerance in tomato. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 125, 948–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).