Abstract

Glutathione reductase (GR) is essential for maintaining cellular redox homeostasis by sustaining reduced glutathione (GSH) levels. In Hypsizygus marmoreus, GR silencing led to impaired mycelial growth, elevated reactive oxygen species (ROS) accumulation, and disrupted antioxidant enzyme activity, ultimately hindering fruiting body development. Mitochondrial size was markedly reduced in GR-silenced strains, indicating compromised cellular metabolism. Supplementation with the reducing agent vitamin C (Vc) partially restored redox balance and enzyme activity in a developmental stage–dependent manner, alleviating the defects caused by GR suppression. Moreover, GR was found to influence lignocellulose-degrading enzyme activity, further linking redox regulation to substrate utilization. Overall, these findings demonstrate that GR plays a central role in coordinating redox balance, energy metabolism, and enzyme function in H. marmoreus, providing new insights for enhancing industrial mushroom production through antioxidant regulation.

1. Introduction

Hypsizygus marmoreus, commonly known as beech mushroom, is an edible basidiomycete mushroom widely cultivated in eastern Asia because of its unique flavor, firm texture, and high nutritional value [1,2,3,4]. In China, H. marmoreus are the third most cultivated edible mushroom. Their annual production reaches 546,200 tons, representing about 55% of the edible mushroom consumer market [5]. In addition to its culinary importance, H. marmoreus contains bioactive compounds with antioxidant and immunomodulatory properties, making it a valuable resource for functional food development [6]. The life cycle of most edible mushrooms comprises the mycelial phase, primordium formation, and fruiting body development. Unlike other wood-decaying fungi, H. marmoreus exhibits a distinctive developmental characteristic wherein, even after complete mycelial colonization of the cultivation substrate, a prolonged post-ripening phase of approximately 40–50 days is required prior to the initiation of fruiting [7]. This extended post-ripening period represents a major bottleneck limiting the efficiency of H. marmoreus cultivation. Accumulating evidence suggests that substantial amounts of ROS are generated during this stage, which may adversely affect fruiting body morphogenesis and development [8,9,10].

ROS, including hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), superoxide anions (O2−), and hydroxyl radicals (OH−), are natural byproducts of aerobic metabolism and act as signaling molecules in various biological processes [11,12]. In fungi, moderate ROS levels are required for normal morphogenesis and development, whereas excessive ROS accumulation can lead to oxidative damage and growth inhibition [10,13,14,15,16]. Therefore, maintaining intracellular ROS homeostasis is essential for normal fungal development and stress resistance. This balance is achieved through enzymatic and nonenzymatic antioxidant systems such as superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT), and the glutathione (GSH) system [17,18,19]. Among them, GR is essential for regenerating GSH from its oxidized form (oxidized glutathione, GSSG) as a flavoprotein oxidoreductase, thus sustaining the cellular redox environment [20,21,22].

In edible mushroom, emerging evidence indicates that GR activity is closely associated with developmental transitions and stress responses. For example, in Pleurotus ostreatus, GR activity in fruiting body development stage is significantly elevated, accompanied by increased antioxidant capacity and reduced lipid peroxidation levels [23]. Transcriptomic analysis of postharvest Lentinula edodes fruiting bodies revealed that the expression of the gr gene was approximately three times greater than that in freshly harvested samples, suggesting that GR may play an important role during fungal maturation and the postripening stage by maintaining ROS homeostasis [24]. Under nitrogen-limiting conditions in Ganoderma lucidum, the transcription factor GCN4 directly activates the expression of genes encoding multiple antioxidant enzymes, including GR, to reduce ROS accumulation and thereby influence secondary metabolism, such as the synthesis of ganoderic acids [25]. However, despite these observations, the specific physiological role of GR in H. marmoreus, particularly during the critical post-ripening and fruiting stages, remains unclear.

In this study, we aimed to clarify how GR-mediated redox regulation influences the transition from vegetative to reproductive growth in H. marmoreus. By constructing GR-silenced strains and applying exogenous vitamin C (Vc), we investigated the effects of GR on ROS balance, mycelial growth, and fruiting body development. This work addresses a key knowledge gap regarding the redox-based regulatory mechanisms underlying mushroom morphogenesis and provides a theoretical basis for optimizing industrial cultivation of H. marmoreus.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Culture Conditions

The fungal strain used in the current study was wild-type (WT) H. marmoreus SIEF3133 (GMCC5.01974), which was stored in the China General Microbiological Culture Collection Center. The nucleotide sequence of its internal transcribed spacer 1 (ITS1) region has been deposited in the GenBank database under the accession number: FJ609271.1. The WT and gri strains were subsequently grown on potato dextrose agar (PDA) at 25 °C under dark conditions. Escherichia coli (TOP10) (Sangon Biotech, Shanghai, China) was used for plasmid construction and cultured in Luria–Bertani (LB) medium supplemented with ampicillin (100 μg/mL). Vc (both from Sangon Biotech, Shanghai, China) was used in this study. Cultivation was performed using the previously described method, both the WT and gri strains of H. marmoreus were grown on a substrate medium composed of sawdust, wheat bran, and corncob [9]. The experimental setup comprised the WT as a control, along with the gri-3 and gri-5 strains, each cultivated in four trays (64 bottles). During the water supplementation phase, an external treatment of 4 mM L-ascorbic acid was applied to two trays (32 bottles) per strain.

2.2. Gene Cloning and RNAi Transformants

From the transcriptome data for H. marmoreus [26], a gr gene sequence was identified. On the basis of the GR sequence, primers were designed to amplify the GR fragment from cDNA by PCR. The RNAi vector was constructed according to the experimental protocol described by [27]. The primers used for amplification of the GR fragment for RNAi vector construction are listed in Supplementary Table S1. The GR fragment was inserted into the BamHI and KnpI sites of the RNAi silencing vector pAN7-dual [27], and the resulting construct was named pAN-dual-GRxi. The pAN-dual-GRxi vector was then introduced into H. marmoreus via electroporation using an Eppendorf electroporator (Eppendorf AG, Hamburg, Germany). Electroporation was performed twice at 1500 V for 3 ms in 2 mm cuvettes, following the method described by [27]. Transformants were selected on PDA medium supplemented with 20 μg/mL hygromycin B. Ten transformants were ultimately selected and subcultured for eight generations on PDA medium without hygromycin B. Transcription levels were subsequently measured to ensure stable silencing efficiency during the detection period.

2.3. Mycelial Growth Rate and ROS Measurement

WT and gri strains were cultured in the dark at 25 °C for 10 days, after which their mycelial growth rates were measured on PDA medium. The colony diameters of the WT and gri strains were measured, and the growth conditions of the mycelia were documented using a Nikon G16 camera (Takara, Dalian, China). Quantification of H2O2 levels in the WT and gri strains cultured in PDB under shaking conditions, as well as measurement of intracellular H2O2 in mycelia at three developmental stages following Vc treatment, was performed using an H2O2 assay kit (Keming Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Suzhou, China). Mycelial plugs from the WT and gri strains were subsequently inoculated onto PDA plates, followed by ROS staining analysis as previously described. Specifically, ROS were detected by fluorescence microscopy (Zeiss Axio Imager L88 microscope with 40× magnification) following staining with 20,70-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (DCHF-DA) for 20 min [9]. Following the pooling of three biological replicates per treatment, the analysis was performed in three technical replicates.

2.4. Observations of Mitochondrial Morphology and Measurement of Mitochondrial Complex Activity Levels

The WT and two gri strains (gri-3 and gri-5) were cultured in PDB medium at 25 °C with shaking at 150 rpm for 10 days. Mycelial pellets with diameters of 3–4 mm from the WT and gri strains were selected and fixed at 4 °C in 2.5% glutaraldehyde and 1.5% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer (pH 7.4). After being washed with the same buffer, cells were post-fixed with 6% KMnO4 in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer for 1 h. Subsequently, they were washed with 30% ethanol, dehydrated through a graded ethanol series, and embedded in Epon 812. The samples were then sent to the Instrumental Analysis Center of Shanghai Jiao Tong University for mitochondrial structural analysis. Mitochondrial structure was examined using a 120-kV transmission electron microscope (Waltham of Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA) following the method described by [28]. In addition, the activity levels of mitochondrial complexes I, II, III, IV, and V in the mycelia of the WT, gri-3 and gri-5 strains were determined using mitochondrial complex I, II, III, IV, and V assay kits. Mitochondrial protein levels in the mycelia were quantified using a BCA protein assay kit (Keming Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Suzhou, China). Following the pooling of three biological replicates per treatment, the analysis was performed in three technical replicates.

2.5. Determination of Antioxidant Enzyme Activity Levels

To assess antioxidant enzyme activity levels, the WT and gri strains were cultured in PDB medium. The cultures were incubated in the dark at 25 °C with shaking at 150 rpm for two weeks. Mycelia were subsequently harvested, after which the activities of antioxidant enzymes were measured. GR, GPX, and SOD levels were determined using antioxidant enzyme assay kits (Keming Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Suzhou, China). In addition, the levels of three antioxidant enzymes (GR, GPX and SOD) and CAT were measured at three developmental stages of H. marmoreus, namely, during mycelial regeneration (H-M), mycelial pigmentation (H-V), and primordium formation (H-P), using the same assay kits. Following the pooling of three biological replicates per treatment, the analysis was performed in three technical replicates.

2.6. Analysis of Redox-Active Compounds

The culture conditions and treatment methods for the samples were the same as previously described. After cultivation, the mycelia were collected, and the levels of GSH and GSSG were measured using GSH and GSSG assay kits (Keming Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Suzhou, China), respectively. The GSH/GSSG ratio was calculated on the basis of the values obtained from the assay kits. Malondialdehyde (MDA) activity and anti-superoxide anion activity were measured using the corresponding assay kits (Keming Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Suzhou, China). In addition, mycelia from three developmental stages (H-M, H-V, and H-P) were harvested from the substrate medium, and the GSH and GSSG levels were measured following a previously described method [29]. Following the pooling of three biological replicates per treatment, the analysis was performed in three technical replicates.

2.7. Determination of the Activity Level of Lignocelluloses

To evaluate the activity levels of enzymes related to cellulose and lignin degradation, sawdust substrates from the mycelial culture medium were collected during the vegetative growth stage of H. marmoreus. Afterward, 25 g of substrate from cultures of the WT and gri strains was added to 50 mL of distilled water and shaken at 200 rpm for 30 min at 25 °C. The mixture was filtered through nonwoven fabric, and the filtrate was centrifuged at 6000× g for 20 min at 4 °C. The resulting supernatant was used to determine the composition and degradation of the lignocellulosic components. Commercial assay kits (Keming Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Suzhou, China) were used to measure the levels and activities of lignocellulolytic enzymes, including cellulase (Cel), laccase (Lac), lignin peroxidase (Lip), and manganese peroxidase (Mnp). Following the pooling of three biological replicates per treatment, the analysis was performed in three technical replicates.

2.8. Gene Expression Analysis by qRT-PCR

Ten transformants were randomly selected and cultured in PDB medium at 25 °C in the dark for 10 days. gri knockdown and WT mycelia were then collected using nonwoven fabric, flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80 °C before total RNA extraction. In addition, the WT and two gri strains were cultured in PDB medium for 12 days. Mycelia were collected as previously described and used to assess the expression of antioxidant enzyme-related genes. mRNA extraction and cDNA synthesis were performed according to the methods described by [27]. The obtained mRNA and cDNA were used for gene expression analysis, with the primers listed in Supplementary Table S1. The internal control gene used was 18S RNA, and the qRT-PCR was performed as described by [27]. The data were analyzed using the 2−ΔΔCT method [30]. Following the pooling of three biological replicates per treatment, the analysis was performed in three technical replicates.

2.9. Statistical Analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Data analysis and graphing were performed using GraphPad Prism 8.0. Before conducting statistical comparisons, data were tested for normality and homogeneity of variances. Statistical significance analysis was completed using IBM SPSS Statistics 23 with Duncan’s multiple range test at a probability of p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. The gr Gene Impaired Mycelial Growth and Induced Oxidative Stress in H. marmoreus

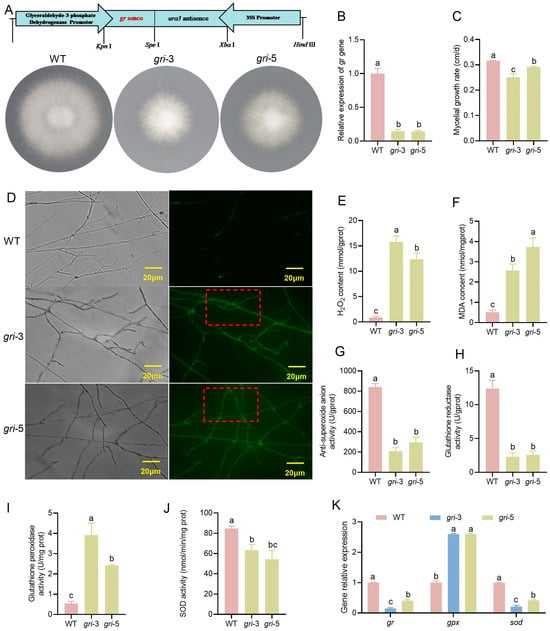

To investigate the function of GR in H. marmoreus, gri knockdown strains were generated via RNA interference (RNAi) technology. Meanwhile, we also successfully screened the gr gene knockdown strains, gri-3 and gri-5 (Figure 1A). These strains were selected on the basis of their significantly reduced gr gene transcript levels, with gene silencing efficiencies reaching 80%, as confirmed by qPCR analysis (Figure 1B). Compared with the WT strain, the gr gene-silenced strains showed a significant reduction in colony diameter and mycelial growth rate, with the gri-3 strain showing a pronounced effect (Figure 1A,C). Fluorescence microscopy revealed a marked increase in hyphal branching and stronger ROS fluorescence signals in the gri knockdown strains, whereas no such phenomenon was observed in the WT strain (Figure 1D). Similarly, the levels of H2O2 and the lipid peroxidation product MDA significantly increased in the gri strains (Figure 1E,F), indicating elevated intracellular ROS levels. Anti-superoxide anion activity is an indicator of an organism’s ability to scavenge superoxide radicals, which are key contributors to membrane lipid peroxidation [31]. Therefore, anti-superoxide anion activity can be used as an indirect measure of lipid peroxidation. The results revealed that anti-superoxide anion activity in the gri strains was significantly lower than that in the WT strain (Figure 1G), indicating that gr gene silencing reduced the ability to scavenge O2−, thereby promoting its accumulation and increasing the degree of membrane lipid peroxidation.

Figure 1.

Construction of silenced strains and analysis of the redox status of H. marmoreus cells. (A) Schematic diagram of silencing vector construction and the growth phenotype of the silenced strains. (B) Relative expression of gr-silenced strains. (C) Hyphal growth rate of the silenced strains. (D) Detection of intracellular ROS in the mycelium, As indicated by the red box, there is evident ROS staining within the mycelium. (E–G) Analysis of H2O2 (E), Malondialdehyde (F), and anti-superoxide anion activity (G) in the wild-type and silenced strains. (H–J) Analysis of the activities of the GR (H), GPX (I) and SOD (J) enzymes in the wild-type and silenced strains. (K) The relative expression levels of the gr, gpx and sod genes; different letters denote statistically significant differences compared with the control according to multiple comparison tests (p < 0.05).

Antioxidative enzymes play crucial roles in eliminating ROS free radicals in living organisms. When the gr gene was silenced, the corresponding GR enzyme activity was significantly reduced in the gri strains; SOD activity was also suppressed, whereas GPX activity markedly increased (Figure 1H–J). Moreover, there may be some correlation between gene expression and enzyme activity, as the trends in gene expression levels were generally consistent with those in enzyme activity (Figure 1K). Notably, compared with the gri-3 strain, the gri-5 strain presented higher gene expression levels.

3.2. The gr Gene Disrupts Mitochondrial Structure and Suppresses the Activity of Key Respiratory Complexes in H. marmoreus

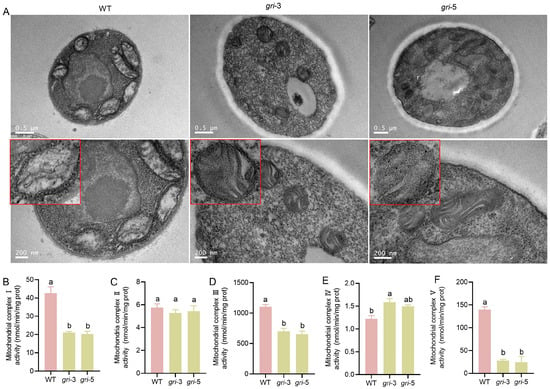

The primary function of mitochondria is to produce energy (ATP) for cells. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) analysis (Figure 2A) revealed pronounced ultrastructural alterations in mitochondria. In the WT strain, the mitochondria exhibited well-organized cristae and a dense matrix, features essential for the optimal function of the electron transport chain (ETC). In contrast, gri strains displayed a disrupted crista architecture, reduced crista density, and abnormal matrix organization. Such morphological abnormalities are likely to compromise mitochondrial electron transport and ATP synthesis, as cristae provide the primary structural platform for the assembly of ETC complexes. It is noteworthy that not only did the mitochondrial volume shrink, but the quantity also decreased between 30% and 44%. These observations suggest that GR plays a pivotal role in maintaining mitochondrial integrity in H. marmoreus, potentially through the regulation of cellular redox homeostasis and the preservation of membrane structure and cristae organization.

Figure 2.

Mitochondrial morphology and mitochondrial complex activity levels in the wild-type and gri strains. (A) Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images showing mitochondrial ultrastructure, the red box indicates an enlarged view of the mitochondria. (B–F) Activities of mitochondrial complexes I–V were measured in the wild-type and gri strains; different letters indicate statistically significant differences compared with the control group, as determined by multiple comparison tests (p < 0.05).

Mitochondrial respiratory chain complexes (I–V) are central to oxidative phosphorylation, the primary ATP-generating pathway in fungal cells. As shown in Figure 2B–F, the activities of complexes I, III, and V were significantly reduced in the gri strains, indicating the disruption of oxidative phosphorylation and a consequent decline in ATP production. Since ATP is essential for biosynthesis, cellular motility, and defense responses, compromised energy metabolism is expected to impair fungal growth, development, and stress resistance. In contrast, the activities of complexes II and IV were only marginally affected, suggesting that alternative electron transfer routes may partially compensate for the functions of these complexes. Taken together, the alterations in mitochondrial morphology and respiratory complex activity indicate that silencing of the gr gene disrupts mitochondrial architecture and impairs respiratory function in H. marmoreus. The disorganization of cristae likely exacerbates functional deficits by reducing the membrane surface area available for respiratory complex assembly.

3.3. The gr Gene Regulates Fruiting Body Development and Mediates Redox Substance Accumulation in H. marmoreus

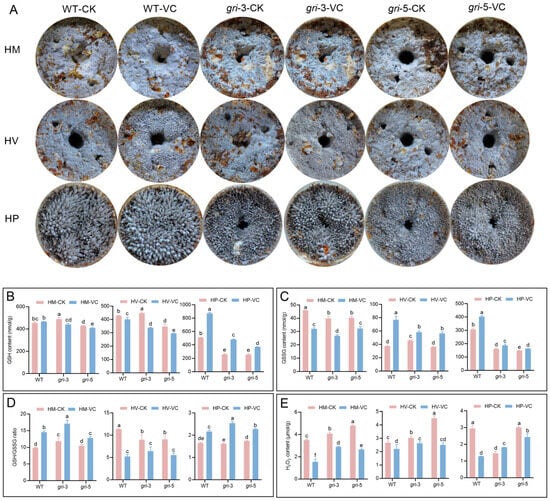

Given the sensitivity of the gri strains to oxidative stress, exogenous Vc supplementation during fruiting body development in H. marmoreus may also influence ROS homeostasis. To investigate the compensatory effects of Vc during the developmental stages of gri strains and elucidate the functional role of GR and the regulatory mechanisms of Vc compensation, two groups, a control group (CK, no additional treatment) and a Vc-treated group (exogenous addition of Vc), were established during three key developmental stages—mycelial regeneration (HM), mycelial pigmentation (HV), and primordium (HP). Phenotypic and physiological changes in both the WT and gri strains were assessed. Compared with the WT strain, the gri strains (gri-3 and gri-5) exhibited pronounced morphological abnormalities at all developmental stages (Figure 3A). During the HM stage, the gri strains displayed sparse hyphae and cavities, whereas the hyphal density was partially restored in the Vc-treated group. At the HV stage, pigmentation was disordered in the gri strains but became more regular upon Vc supplementation. In the HP stage, the gri strains presented sparse and unevenly distributed primordia, which were alleviated by Vc treatment. These results indicate that GR plays a critical role in maintaining normal fruiting body morphogenesis and that Vc can partially mitigate the developmental defects caused by GR silencing. The glutathione (GSH) content is shown in Figure 3B. At the HM stage, the GSH levels did not significantly change after Vc supplementation in either the WT or gri strains, indicating that the endogenous redox system remains stable at this stage and that exogenous antioxidant input has limited effects. At the HV stage, the GSH content decreased upon the addition of Vc to both the WT and gri strains, with a more pronounced decline in the gri-3 strain, suggesting that this metabolically active phase triggers strain-specific responses to Vc. At the HP stage, the GSH levels markedly increased in both the WT and gri strains following Vc treatment, suggesting that the increased compensatory effects of Vc during reproductive development were likely due to increased demands for redox homeostasis. In the HM stage, GSSG levels decreased in both the WT and gri strains upon Vc supplementation (Figure 3C). These findings indicate that the activity of Vc, an antioxidant, facilitates the conversion of GSSG to GSH, resulting in lower GSSG levels in the Vc group than in the CK group. During the HV stage, GSSG levels increased significantly in both the WT and the strains after the addition of Vc, with a more prominent increase in the WT strain. This stage represents the metabolic transition from vegetative to reproductive growth, during which time elevated ROS production occurs. In WT strains with intact GR expression, the synergistic effect between GR activity and Vc may contribute to increased GSSG turnover. At the HP stage, GSSG level increased only slightly in response to Vc treatment in both strains. Notably, compared with the WT strain, the gri strains maintained significantly lower GSSG levels under both treatment conditions. These findings suggest that ROS production is relatively low during primordium initiation and that the demand for precise redox control limits fluctuations in GSSG levels even under antioxidant intervention.

Figure 3.

(A) Morphological phenotypes of H. marmoreus fruiting bodies at different developmental stages: mycelial regeneration (HM), mycelial pigmentation (HV), and primordium (HP). The strains included wild-typeand gri strains under control and Vc supplemented conditions. The contents of GSH (B), GSSG (C), the GSH/GSSG ratio (D) and H2O2 (E) were measured in H. marmoreus at various developmental stages; different letters indicate statistically significant differences compared with the control group, as determined by multiple comparison tests (p < 0.05).

The GSH/GSSG ratio, a critical indicator of cellular redox balance, inversely reflects the degree of oxidative stress. As shown in Figure 3D, this ratio increased in both the WT and gri strains following Vc treatment at the HM and HP stages. During the HM stage, basal metabolic activity and ROS levels are low, and Vc may increase reducing power by cooperating with GR, leading to a higher GSH/GSSG ratio. At the HP stage, where metabolic remodeling and precise redox regulation are essential for primordium differentiation, Vc supplementation further increased the ratio. This effect was more pronounced in the gri strains, likely because of the enhanced compensatory activity of Vc in the absence of GR function. In contrast, at the HV stage, the GSH/GSSG ratio decreased after the addition of Vc. This stage involves a metabolic burst and excessive ROS accumulation, which may overwhelm the redox system, and Vc supplementation could transiently disrupt the dynamic redox equilibrium, thereby aggravating oxidative stress. In the WT strain, H2O2 levels were consistently lower in the Vc-treated group than in the CK group across all stages, with the most pronounced effect observed during the HP stage (Figure 3E). These findings suggest that the endogenous antioxidant system in the WT strain is robust and that Vc further promotes ROS scavenging, maintaining low oxidative stress. At the HM stage, H2O2 levels in the gri strains were higher than those in the WT strain, likely because of impaired GSH regeneration resulting from GR silencing, which compromised efficient H2O2 detoxification. Vc supplementation significantly reduced the H2O2 content, indicating that Vc can directly scavenge H2O2 and alleviate oxidative stress at early stages. At the HV stage, the production of ROS—including H2O2—increased sharply because of high metabolic activity. Among the gri strains lacking GR-mediated redox buffering, H2O2 levels in the Vc-treated group were still lower than those in the CK group but remained higher than those in the WT-VC group, suggesting that while the efficacy of Vc is limited under high oxidative loads, it still partially mitigates the accumulation of ROS, particularly in gri-5. At the HP stage, owing to the influence of growth and development, changes during the primordium period were irregular.

Overall, GR silencing disrupts redox homeostasis during fruiting body development in H. marmoreus, leading to morphological abnormalities and redox imbalance at the HM, HV and HP stages. Vc treatment alleviates developmental defects and oxidative stress in a stage-dependent manner by scavenging ROS and modulating glutathione metabolism. The rescuing effect of Vc is particularly significant during the primordium formation stage, underscoring its potential to improve oxidative stress tolerance and developmental stability under GR-deficient conditions.

3.4. The gr Gene Influences Antioxidant Enzyme Activity During the Development of H. marmoreus

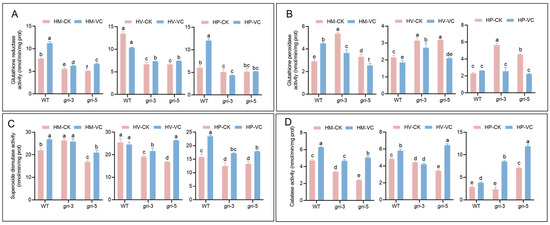

To investigate the impact of gr gene silencing on the antioxidant enzyme system during different developmental stages of H. marmoreus and the regulatory effects of Vc supplementation, the activities of four key antioxidant enzymes were assessed (Figure 4A–D). Among gri strains, GR activity was significantly lower in the CK group than in the WT group across all developmental stages (Figure 4A). Compared with that in the WT group, the GR activity in the WT-Vc group slightly increased but remained markedly lower in the gri-Vc group, indicating that compared with that in the WT group, the restorative effect of Vc supplementation on the GR activity in the silenced strains was limited. Notably, GR activity peaked at the HV stage, which was consistent with elevated metabolic activity and redox demand during the pigmentation transition. The activity of GPX, which is responsible for the use of GSH to detoxify H2O2 and other peroxides and protect cells from oxidative damage, was determined. At all stages, the GPX activity of the gri strains in the CK group was greater than that in the WT group, indicating a compensatory response to GR silencing (Figure 4B). In the HM and HP stages, GPX activity in the WT-Vc group was elevated compared with that in the WT-CK group, suggesting that although GSH metabolism remains stable in the WT group, Vc can reduce GPX consumption by directly scavenging ROS. However, at the HV stage, characterized by a surge in metabolic activity and ROS production, Vc acted as a potent antioxidant that directly neutralized ROS, which in turn suppressed GPX demand. In all stages, the GPX activity of the gri-Vc group was significantly lower than that of the gri-CK group, likely because of impaired GSH regeneration caused by GR silencing. Vc accelerated the consumption of GSH and suppressed its synthesis, leading to substrate limitation for GPX and thereby reducing its activity. As the first line of defense against ROS, SOD converts superoxide radicals (O2−) into hydrogen peroxide, and its activity is depicted in Figure 4C. In most stages, SOD activity in the WT-Vc group was comparable to or slightly greater than that in the WT-CK group, especially during HM and HV, suggesting that the intrinsic antioxidant capacity of WT is stable and that Vc may alleviate the downstream oxidative burden by directly scavenging ROS, reducing the stress on SOD. At the HM stage, compared with that in the WT-CK group, the SOD activity in the gri-CK group was altered. Although GR silencing disrupted glutathione cycling and promoted the accumulation of ROS, especially O2−, the expected upregulation of SOD activity was not observed, possibly because of the limited compensatory capacity of the strain. This highlights the strain-specific antioxidant response to Vc. At the HV stage, the SOD activity of the gri-Vc strains markedly increased because of excessive ROS accumulation and impaired GSH cycling. At the HP stage, SOD activity in the gri-Vc group also increased under Vc treatment, reflecting an adaptive response to redox demands during primordium formation, although the activity remained lower than that in the WT-Vc group because of the basal deficiency caused by GR silencing. CAT directly breaks down H2O2 and is vital for removing excess hydrogen peroxide. In all stages, CAT activity in the WT-Vc group was consistently greater than that in the WT-CK group (Figure 4D), indicating that Vc cooperates with CAT to maintain intracellular redox homeostasis by reducing the CAT workload through direct ROS scavenging. In the HM and HV stages, CAT activity was lower in the gri-CK group than in the WT-CK group because of disrupted glutathione cycling and excessive H2O2 accumulation resulting from GR silencing. Upon Vc treatment, CAT activity in the gri-Vc group increased, likely because Vc not only directly scavenges H2O2, reducing the oxidative burden but also modulates redox signaling, inducing CAT expression or activation. Thus, compared with that in the gri-CK group, CAT activity in the gri-Vc group was generally greater throughout development. GR silencing alters the activities of GR, GPX, SOD, and CAT, disrupting antioxidant homeostasis. Vc treatment, by scavenging ROS and modulating enzyme activity, partially relieves oxidative stress caused by GR deficiency in a stage-specific manner. These findings elucidate the dynamic antioxidant regulation in H. marmoreus and provide insights into the mechanism of Vc-mediated redox compensation.

Figure 4.

Activities of four key antioxidant enzymes in H. marmoreus at different developmental stages: mycelial regeneration, mycelial pigmentation, and primordium. The strains included wild-type and gri strains under control and Vc-treated conditions. The activities of GR (A), GPX (B), SOD (C) and CAT (D) were measured; different letters indicate statistically significant differences compared with the control group, as determined by multiple comparison tests (p < 0.05).

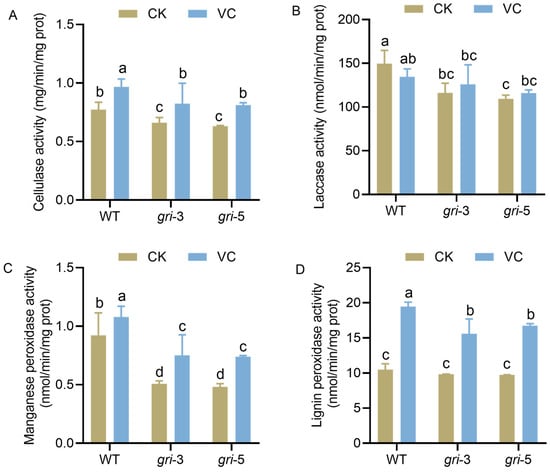

3.5. Vc Supplementation Restores Lignocellulose-Degrading Enzyme Activity in H. marmoreus gri Strains

The effects of gri and Vc treatment on lignocellulolytic enzyme activity in H. marmoreus were investigated. Cellulases are essential for breaking down cellulose into utilizable sugars, serving as a critical pathway for carbon acquisition. Laccase (Lac), manganese peroxidase (MnP), and lignin peroxidase (LiP) synergistically degrade lignin, facilitating the breakdown of the lignocellulose structural barrier. The cellulase activity increased in the WT strains following Vc treatment (Figure 5A). These findings suggest that Vc may regulate metabolic signaling—such as by modulating intracellular ROS levels—to activate cellulase biosynthetic pathways and increase carbon degradation capacity. A similar increase in cellulase activity was observed in the gri strains after Vc supplementation. However, the extent of the increase was slightly reduced compared with that in the WT strain, likely due to redox imbalance caused by GR silencing, indicating a fundamental constraint on carbon metabolism. In the WT strains, the effects of Vc treatment were minimal or even slightly inhibitory, possibly because of the fact that redox status was already balanced and because basal laccase activity was sufficient to meet the demands for lignin degradation, which limited the room for further enhancement by Vc. In contrast, the gri strains exhibited a modest increase in laccase activity upon Vc treatment (Figure 5B). GR silencing disrupted redox-related signaling pathways involved in lignin degradation, whereas Vc helped restore redox homeostasis, thereby partially rescuing laccase function and alleviating the impairment of lignin degradation. MnP activity was significantly elevated in the WT strains upon Vc supplementation. Vc likely alleviated the ROS-induced repression of MnP synthesis, thereby enhancing Mn-dependent lignin degradation. In the gri strains, MnP activity improved even more markedly following Vc treatment (Figure 5C). GR silencing led to excessive ROS accumulation, which negatively affected enzyme production. Vc restored MnP activity by scavenging inhibitory ROS and improving the intracellular environment for enzyme biosynthesis, highlighting a strong rescue effect. Vc treatment significantly increased LiP activity in WT strains, likely by optimizing the intracellular redox potential and promoting a favorable catalytic environment. In the gri strains, LiP activity was initially suppressed because of GR silencing but was markedly restored after Vc supplementation (Figure 5D). These findings indicate that Vc can help reestablish redox homeostasis, increase enzyme synthesis and catalytic function, and ultimately relieve the bottleneck in lignocellulose degradation. In conclusion, gr gene silencing impaired the activities of key lignocellulose-degrading enzymes in H. marmoreus, thereby limiting efficient carbon source utilization. Vc supplementation, by modulating redox status and metabolic signaling pathways, enhances the activities of cellulase, Lac, MnP, and LiP, mitigating the negative effects of GR silencing and improving the lignocellulose degradation capacity of the fungus.

Figure 5.

Activities of four key lignocellulose-degrading enzymes in H. marmoreus. The strains included wild-type and gri strains under control and Vc-treatment conditions. The activities of cellulase (A), Laccase (B), Manganese peroxidase (C), and Lignin peroxidase (D) were measured; different letters indicate statistically significant differences compared with the control group, as determined by multiple comparison tests (p < 0.05).

4. Discussion

H. marmoreus is among the most widely cultivated edible mushroom in industrial production in China. Nevertheless, its relatively long postripening phase, lasting approximately 40–50 days, substantially prolongs the overall cultivation cycle and has been recognized as a major bottleneck restricting improvements in production efficiency [29]. Exogenous supplementation with saponin, kojic acid, and hydrogen-rich water enhances the activities of antioxidant enzymes and the capacity for ROS scavenging in H. marmoreus. These treatments concurrently shorten fruiting body development and thereby improve the efficiency of industrial-scale production [32,33]. Therefore, eliminating the excessive accumulation of ROS and maintaining intracellular redox homeostasis are critical for mycelial growth and fruiting body development in H. marmoreus [29]. The fruiting body development and differentiation in basidiomycetes are regulated by redox homeostasis and ROS signaling [10,34,35,36]. In fungi, intracellular ROS are scavenged through enzymatic reactions of the antioxidant system, among which GR, a key component of the GSH-GSSG cycle, plays a pivotal role in regulating cellular redox homeostasis [37,38,39]. In this study, we demonstrate that as a key enzyme in the GSH-dependent antioxidant system, GR is essential for maintaining intracellular redox equilibrium in H. marmoreus. Silencing the gr gene led to increased oxidative stress, disrupted mitochondrial architecture, and developmental abnormalities, especially during the morphogenesis of the fruiting body.

During both the mycelial growth phase and the fruiting body development stage in edible mushroom, ROS are generated and accompanied by dynamic changes in antioxidant enzyme activity [10,40]. GR silencing resulted in significantly reduced GSH regeneration and a disrupted GSH/GSSG balance, confirming the pivotal role of GR in sustaining cellular reducing ability. The accompanying increase in H2O2 and MDA levels suggests intensified lipid peroxidation and oxidative damage, which is consistent with previous findings in fungi and plants where GR loss leads to ROS overaccumulation and oxidative injury [41,42]. This demonstrates that GR-mediated redox imbalance triggers a massive ROS burst in hyphae. In Ganoderma lucidum, downregulation of the glutathione peroxidase gene (GPX) leads to an imbalance in redox status and a reduced capacity for ROS scavenging [43]. However, in our study, although GPX activity was somewhat increased in the gri strains, the overall capacity for ROS scavenging was still reduced. In addition, the downregulation of mitochondrial complex I and III activity and the deformation of cristae in the gri strains further indicate that GR is indispensable for mitochondrial integrity and energy metabolism [44,45,46,47]. Our study revealed that silencing the gr gene led to a significant reduction in mitochondrial size, suggesting that excessive intracellular ROS may impair normal mitochondrial formation and function. ROS may inhibit energy metabolism by disrupting mitochondrial formation or act as a signal to regulate hyphal development. In fungi, Vc is typically used as a reducing agent to scavenge intracellular ROS. As a hydrogen donor, Vc can reduce oxidized GSH back to its reduced form, thereby replenishing cellular GSH and contributing to the maintenance of intracellular redox homeostasis [29,48]. The exogenous application of Vc alleviated oxidative damage and partially reversed developmental defects in a stage-dependent manner. Vc restored the GSH/GSSG ratio and decreased ROS levels, particularly during the HP stage, supporting its role as a redox regulator. Notably, although Vc treatment did not restore GR activity, the loss of GR activity was compensated for via the modulation of the activity of other ROS-scavenging enzymes, such as GPX, SOD, and CAT. This finding is in line with the results of studies showing that Vc can directly scavenge ROS and enhance antioxidant responses under abiotic stress [10,49,50]. Exogenous reducing agent addition further confirms that ROS from mycelial damage suppresses fruiting body development. However, this study has limitations. Notably, the RNAi approach may have off-target effects, and gr gene overexpression was not achieved. Future work should employ gene editing technologies to further investigate gr gene function.

During the prolonged postripening period of H. marmoreus, not only is intracellular redox homeostasis involved, but changes in the activities of lignocellulolytic enzymes also occur. The activity levels of these enzymes directly influence the substrate conversion efficiency of H. marmoreus [51]. Interestingly, the impairment of lignocellulose-degrading enzymes in gri strains suggests that redox imbalance affects not only stress defense but also nutrient acquisition. GR silencing decreased cellulase and ligninolytic enzyme activities, thereby potentially limiting carbon metabolism and substrate utilization. Vc intervention increases the activities of cellulase, laccase, MnP, and LiP, especially in gri strains, possibly by optimizing the intracellular redox potential and relieving ROS-mediated transcriptional repression [52]. These findings highlight the broad regulatory role of redox homeostasis in fungal metabolism and enzyme expression.

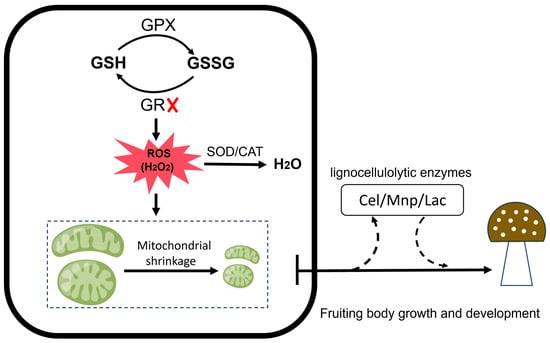

5. Conclusions

GR is a central component of the antioxidant machinery in H. marmoreus and is essential for mitochondrial function, enzyme activity, and fruiting body development. Silencing the gr gene disrupts cellular redox homeostasis, leading to a significant accumulation of ROS. This inhibits normal cell growth and development, notably by reducing mitochondrial size and impairing cellular energy metabolism. Furthermore, the silencing of the gr gene indirectly inhibits lignocellulose activity (e.g., Cel, Mnp and Lac), which impairs fruiting body development in H. marmoreus (Figure 6). These findings not only provide insights into the growth and industrial cultivation of edible mushroom, but also hold great significance for developing antioxidant additives to shorten the cultivation cycle and enhance yield and quality.

Figure 6.

Schematic diagram illustrating the roles of GSH/GSSG, GPX, and GR in regulating reactive oxygen species levels and their mechanistic effects on mitochondrial function, lignocellulolytic enzyme activity, and fruiting body development.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/horticulturae11121441/s1, Table S1: Primers for construction of silent plasmids and primers for qRT-PCR of the validation gene.

Author Contributions

H.H., H.C. and J.Z. designed the experiments; H.H. and J.Z. collected the samples and carried out the experiment; Y.Z., Q.W., T.X. and Y.Y. collated and analyzed the data; Y.Z. and H.H. wrote the manuscript; H.C. and J.Z. reviewed and edited. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the Agriculture Research System of Shanghai, China [Grant No. 202509].

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article and Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jing Zhao for providing assistance in performing the experiments.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Son, S.Y.; Park, Y.J.; Jung, E.S.; Singh, D.; Lee, Y.W.; Kim, J.-G.; Lee, C.H. Integrated metabolomics and transcriptomics unravel the metabolic pathway variations for different sized beech mushrooms. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 6007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, J.; Lin, J.; Yan, J.; Zhang, C.; Wang, T.; Gan, B. Evaluation of the nutritional value, umami taste, and volatile organic compounds of Hypsizygus marmoreus by simulated salivary digestion in vitro. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2023, 7, 100591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kala, K.; Lazur, J.; Karnafał, J.; Pająk, W.; Sulkowska-Ziaja, K.; Muszynska, B. Beech mushroom (Hypsizygus marmoreus, Agaricomycetes) cultivation and outstanding health-promoting properties: A Review. Int. J. Med. Mushrooms 2024, 26, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, J.N.; Yadav, A.N. A comprehensive review on multifunctional bioactive properties of elm oyster mushroom Hypsizygus ulmarius (Bull.) Redhead (Agaricomycetes): Current research, challenges and future trends. Heliyon 2025, 11, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, L.L.; Guo, L.Z.; Yu, H. Label-Free Comparative proteomics analysis revealed heat stress responsive mechanism in Hypsizygus marmoreus. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 541967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kała, K.; Pająk, W.; Sułkowska-Ziaja, K.; Krakowska, A.; Lazur, J.; Fidurski, M.; Marzec, K.; Zięba, P.; Fijałkowska, A.; Szewczyk, A.; et al. Hypsizygus marmoreus as a source of indole compounds and other bioactive substances with health-promoting activities. Molecules 2022, 27, 8917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Q.; Arshad, M.; Li, Y.; Zhang, H.; Gu, Y.; Yu, X.; Zhao, K.; Ma, M.; Zhang, L.; He, M.; et al. Transcriptomic profiling revealed important roles of amino acid metabolism in fruiting body formation at different ripening times in Hypsizygus marmoreus. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1169881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tudzynski, P.; Heller, J.; Siegmund, U. Reactive oxygen species generation in fungal development and pathogenesis. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2012, 15, 653–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Hai, H.; Wang, H.; Wang, Q.; Chen, M.; Feng, Z.; Ye, M.; Zhang, J. Hydrogen-rich water mediates redox regulation of the antioxidant system, mycelial regeneration and fruiting body development in Hypsizygus marmoreus. Fungal Biol. 2018, 122, 310–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Hao, H.; Wu, X.; Wang, Q.; Chen, M.; Feng, Z.; Chen, H. The functions of glutathione peroxidase in ROS homeostasis and fruiting body development in Hypsizygus marmoreus. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2020, 104, 10555–10570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Autréaux, B.; Toledano, M.B. ROS as signalling molecules: Mechanisms that generate specificity in ROS homeostasis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007, 8, 813–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmström, K.M.; Finkel, T. Cellular mechanisms and physiological consequences of redox-dependent signalling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2014, 15, 411–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Shi, L.; Chen, D.; Ren, A.; Gao, T.; Zhao, M. Functional analysis of the role of glutathione peroxidase (GPx) in the ROS signaling pathway, hyphal branching and the regulation of ganoderic acid biosynthesis in Ganoderma lucidum. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2015, 82, 168–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cano-Dominguez, N.; Alvarez-Delfin, K.; Hansberg, W.; Aguirre, J. NADPH oxidases NOX-1 and NOX-2 require the regulatory subunit NOR-1 to control cell differentiation and growth in Neurospora crassa. Eukaryot. Cell 2008, 7, 1352–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, L.; He, T.; Farrar, S.; Ji, L.; Liu, T.; Ma, X. Antioxidants maintain cellular redox homeostasis by elimination of reactive oxygen species. Cell Physiol. Biochem. 2017, 44, 532–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Sun, L.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zheng, J. Imbalanced GSH/ROS and sequential cell death. J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 2022, 36, e22942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ighodaro, O.M.; Akinloye, O.A. First line defence antioxidants-superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT) and glutathione peroxidase (GPX): Their fundamental role in the entire antioxidant defence grid. Alex. J. Med. 2018, 54, 287–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irato, P.; Santovito, G. Enzymatic and non-enzymatic molecules with antioxidant function. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgiou-Siafis, S.K.; Tsiftsoglou, A.S. The key role of GSH in keeping the redox balance in mammalian cells: Mechanisms and significance of GSH in detoxification via formation of conjugates. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, G.; Li, N.; Liu, Y.; Yu, L.; Yan, J.; Luo, L. Sinorhizobium meliloti glutathione reductase is required for both redox homeostasis and symbiosis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2018, 84, e01937-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, I.; Shimizu, M.; Hoshino, T.; Takaya, N. The glutathione system of Aspergillus nidulans involves a fungus-specific glutathione s-transferase. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 8042–8053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wangsanut, T.; Pongpom, M. The role of the glutathione system in stress adaptation, morphogenesis and virulence of pathogenic fungi. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 10645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamad, D.; El-Sayed, H.; Ahmed, W.; Sonbol, H.; Ramadan, M.A.H. GC-MS analysis of potentially volatile compounds of Pleurotus ostreatus polar extract: In vitro antimicrobial, cytotoxic, immunomodulatory, and antioxidant activities. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 834525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakamoto, Y.; Nakade, K.; Sato, S.; Yoshida, K.; Miyazaki, K.; Natsume, S.; Konno, N. Lentinula edodes genome survey and postharvest transcriptome analysis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2017, 83, e02990-16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lian, L.; Wang, L.; Song, S.; Zhu, J.; Liu, R.; Shi, L.; Ren, A.; Zhao, M. GCN4 regulates secondary metabolism through activation of antioxidant gene expression under nitrogen limitation conditions in Ganoderma lucidum. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2021, 87, e00156-21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Chen, H.; Chen, M.; Wang, H.; Wang, Q.; Song, X.; Hao, H.; Feng, Z. Kojic acid-mediated damage responses induce mycelial regeneration in the basidiomycete Hypsizygus marmoreus. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0187351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Chen, H.; Chen, M.; Wang, H.; Song, X.; Feng, Z. Construction and application of a gene silencing system using a dual promoter silencing vector in Hypsizygus marmoreus. J. Basic Microbiol. 2017, 57, 78–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piotr, K.; Marcin, G.; Beata, P.; Anna, S.; Katarzyna, W.; Jan, F.; Kurlandzka, A. Newly identified protein Imi1 affects mitochondrial integrity and glutathione homeostasis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEMS Yeast Res. 2015, 15, fov048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Hao, H.; Han, C.; Wang, H.; Wang, Q.; Chen, M.; Juan, J.; Feng, Z.; Zhang, J. Exogenous l-ascorbic acid regulates the antioxidant system to increase the regeneration of damaged mycelia and induce the development of fruiting bodies in Hypsizygus marmoreus. Fungal Biol. 2020, 124, 551–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT Method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.S. Effect of diethyl phthalate on biochemical indicators of carp liver tissue. Toxin Rev. 2015, 34, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Zhang, J.; Hao, H.; Feng, Z.; Chen, M.; Wang, H.; Ye, M. Hydrogen-rich water increases postharvest quality by enhancing antioxidant capacity in Hypsizygus marmoreus. AMB Express 2017, 7, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Hao, H.; Chen, M.; Wang, H.; Feng, Z.; Chen, H. Hydrogen-rich water alleviates the toxicities of different stresses to mycelial growth in Hypsizygus marmoreus. AMB Express 2017, 7, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- You, B.J.; Chang, W.T.; Chung, K.R.; Kuo, Y.H.; Yang, C.S.; Tien, N.; Hsieh, H.-C.; Lai, C.-C.; Lee, H.-Z. Effect of solid-medium coupled with reactive oxygen species on ganoderic acid biosynthesis and MAP kinase phosphorylation in Ganoderma lucidum. Food Res. Int. 2012, 49, 634–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, X.; Wang, F.; Zhang, H.; Bai, J.; Dong, Q.; Yue, P.; Jiang, X.; Li, X.; Wang, L.; Guo, J. iTRAQ-based comparative proteome analyses of different growth stages revealing the regulatory role of reactive oxygen species in the fruiting body development of Ophiocordyceps sinensis. Peer J. 2021, 9, e10940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y.; Boiti, A.; Vallone, D.; Foulkes, N.S. Reactive oxygen species signaling and oxidative stress: Transcriptional regulation and evolution. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasanuzzaman, M.; Hossain, M.A.; da Silva, J.A.T.; Fujita, M. Plant response and tolerance to abiotic oxidative stress: Antioxidant defense is a key factor. In Crop Stress and Its Management: Perspectives and Strategies; Venkateswarlu, B., Shanker, A.K., Shanker, C., Maheswari, M., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 261–315. [Google Scholar]

- James, M.R.; Doss, K.E.; Cramer, R.A. New developments in Aspergillus fumigatus and host reactive oxygen species responses. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2024, 80, 102521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattila, H.K.; Österman-Udd, J.; Mali, T.L.E.; Lundell, T. Basidiomycota fungi and ROS: Genomic perspective on key enzymes involved in generation and mitigation of reactive oxygen species. Front. Fungal Biol. 2022, 3, 837605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwankwegu, A.S.; Hongsanan, S.A.; Nwankwegu, U.P.; Xie, N. Exploring the critical environmental optima and biotechnological prospects of fungal fruiting bodies. Microb. Biotechnol. 2025, 18, e70210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korge, P.; Calmettes, G.; Weiss, J.N. Increased reactive oxygen species production during reductive stress: The roles of mitochondrial glutathione and thioredoxin reductases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2015, 1847, 514–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.M.; Lin, W.R.; Kao, C.H.; Hong, C.Y. Gene knockout of glutathione reductase 3 results in increased sensitivity to salt stress in rice. Plant Mol. Biol. 2015, 87, 555–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, A.; Liu, R.; Miao, Z.; Zhang, X.; Cao, P.; Chen, T.; Li, C.; Shi, L.; Jiang, A.; Zhao, M. Hydrogen-rich water regulates effects of ROS balance on morphology, growth and secondary metabolism via glutathione peroxidase in Ganoderma lucidum. Environ. Microbiol. 2017, 19, 566–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gostimskaya, I.; Grant, C.M. Yeast mitochondrial glutathione is an essential antioxidant with mitochondrial thioredoxin providing a back-up system. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2016, 94, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ježek, P.; Jabůrek, M.; Holendová, B.; Engstová, H.; Dlasková, A. Mitochondrial cristae morphology reflecting metabolism, superoxide formation, redox homeostasis, and pathology. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2023, 39, 635–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.H.; Wang, H.C.; Chang, C.J.; Lee, S.Y. Mitochondrial glutathione in cellular redox homeostasis and disease manifestation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.F.; Zhang, S.B.; Zhai, H.C.; Lv, Y.Y.; Hu, Y.S.; Cai, J.P. Hexanal induces early apoptosis of Aspergillus flavus conidia by disrupting mitochondrial function and expression of key genes. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2021, 105, 6871–6886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Cao, P.; Ren, A.; Wang, S.; Yang, T.; Zhu, T.; Shi, L.; Zhu, J.; Jiang, A.-L.; Zhao, M.-W. SA inhibits complex III activity to generate reactive oxygen species and thereby induces GA overproduction in Ganoderma lucidum. Redox Biol. 2018, 16, 388–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akram, N.A.; Shafiq, F.; Ashraf, M. Ascorbic acid-a potential oxidant scavenger and its role in plant development and abiotic stress tolerance. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanwal, R.; Maqsood, M.F.; Shahbaz, M.; Naz, N.; Zulfiqar, U.; Ali, M.F.; Jamil, M.; Khalid, F.; Ali, Q.; Sabir, M.A.; et al. Exogenous ascorbic acid as a potent regulator of antioxidants, osmo-protectants, and lipid peroxidation in pea under salt stress. BMC Plant Biol. 2024, 24, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galic, M.; Stajic, M.; Simonić, J. Hypsizygus Marmoreus—A novel potent degrader of lignocellulose residues. Cellul. Chem. Technol. 2020, 54, 977–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, A.; Wang, W.; Guo, S.; Li, C.; Wang, X.; Fei, Q. Insight into the role of antioxidant in microbial lignin degradation: Ascorbic acid as a fortifier of lignin-degrading enzymes. Biotechnol. Biofuels Bioprod. 2025, 18, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).