1. Introduction

Sweet potato [

Ipomoea batatas (L.) Lam.] is a resilient and economically important crop that has attracted worldwide attention due to its high production. Most of the world’s sweet potato cultivation is concentrated in Asia and Africa, as these two continents account for 95% of the global production. Asia is the top sweet-potato-producing continent, followed by Africa, the Americas, Oceania, and Europe [

1]. Due to its high adaptability to a variety of environments, sweet potato is grown in a wide range of geographic regions, including mountainous areas where it is exposed to a variety of biotic and abiotic stresses provided by the harsh soil conditions [

2]. Recent climate change developments have also increased threats to global crop production, including that of sweet potato. Such environmental variability can influence the incidence, severity, and geographic range of plant diseases [

3].

The cultivation of sweet potato has been greatly affected by foot rot disease, which is caused by the fungal plant pathogen

Diaporthe destruens (also known as

Plenodomus destruens). Foot rot of sweet potato caused by

Diaporthe destruens was first described in the United States in 1912 [

4]. In Japan, occurrence of this disease was first reported in Okinawa Prefecture in 2018 [

5]. Before its identification, foot rot disease had already been reported repeatedly in East Asian countries and subsequently spread throughout Japan [

6]. The situation has become extremely serious in Okinawa, Kagoshima, and Miyazaki prefectures, Japan, where the disease has hindered the supply of raw materials for confectioneries, sweet potato shochu (a Japanese distilled liquor), starch, and products for fresh consumption [

5,

7]. Therefore, sweet potato cultivars that are resistant to foot rot are urgently needed, as is the agronomic control against foot rot. At present, a high-quality draft genome of

Diaporthe destruens is available, providing a useful genomic resource [

8]. However, no sweet potato cultivars with complete resistance to foot rot have been selected, and the genes that are involved in such resistance have also not been identified.

Setoguchi et al. [

9] established a fundamental technique for selecting sweet potato cultivars resistant to foot rot by analyzing polyphenols in disease-free healthy stems. Cultivars with lower stem polyphenol content were less susceptible to foot rot, while cultivars with higher stem polyphenol content were more susceptible to foot rot. In particular, they found strong correlations with several polyphenols, including 3,4-dicaffeoylquinic acid and chlorogenic acid. They proposed the use of stem polyphenols as a marker for selecting sweet potato cultivars resistant to foot rot. In general, polyphenols, mainly phenylpropanoids and flavonoids, are widely recognized to contribute to plant disease resistance. Among them, chlorogenic acid has been highlighted as a key component of plant defense [

10,

11]. In plant defense against pathogens, these compounds may act indirectly as signaling molecules or be directly mediated through the toxic effects of phytoanticipins (active compounds constitutively stored in plant tissues) and phytoalexins (active compounds newly synthesized upon pathogen detection) [

12,

13].

However, metabolites, including polyphenols, are known to be strongly affected by environmental factors, such as temperature, light, and water availability, and their association with disease resistance is not always consistent across environmental conditions. Therefore, although stem polyphenols represent a promising indicator of foot rot susceptibility, their reliability as a selection marker requires validation in diverse breeding materials [

14,

15].

Currently, cutting-edge crop breeding practices utilize genomics-based approaches, such as molecular markers, genomic selection, and genome editing tools, for precise and efficient improvement in crop production [

16,

17,

18]. However, traits that consist of complex gene networks can be difficult to breed using molecular markers. The production of secondary metabolites is crucial for plant tolerance to biotic and abiotic stresses and serves not only as a defense mechanism but also as a potential biomarker for stress tolerance [

19]. Ondobo et al. [

20] found a negative correlation between the size of necrotic lesions and the total phenolic content in leaves of cocoa affected by black pod disease caused by

Phytophthora megakarya, and selected six disease-resistant cocoa lines. Furthermore, Chitarrini et al. [

21] conducted extensive metabolomics studies using resistant grapevine cultivars and Bianca grape leaves infected with downy mildew (

Plasmopara viticola), identifying 53 putative metabolites as markers for the first time, highlighting the potential of metabolite markers for breeding disease-resistant cultivars.

Taking these findings into consideration, if the basic technology proposed by Setoguchi et al. [

9] can be utilized in actual crossbreeding, the potential for primary selection of foot-rot-resistant strains of sweet potato using polyphenol markers will increase. In the present study, we crossed the sweet potato cultivars ‘Tamaakane’ and ‘Konaishin’, which have been shown to be moderately resistant to foot rot, and analyzed the polyphenols in the stems of their progeny seedlings to investigate the relationship between polyphenol content and foot rot resistance. We also grew a sweet potato line that showed the same level of resistance as ‘Tamaakane’, evaluated its agronomic traits, and tested its storage roots through inoculation with the foot rot pathogen. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate the applicability of stem polyphenol markers in a crossbreeding population and assess foot rot resistance in sweet potato based on inoculation tests using storage roots. Previous studies, such as Setoguchi et al. [

9], focused on variety panels, whereas our study tests the predictivity of these markers in a breeding context.

2. Materials and Methods

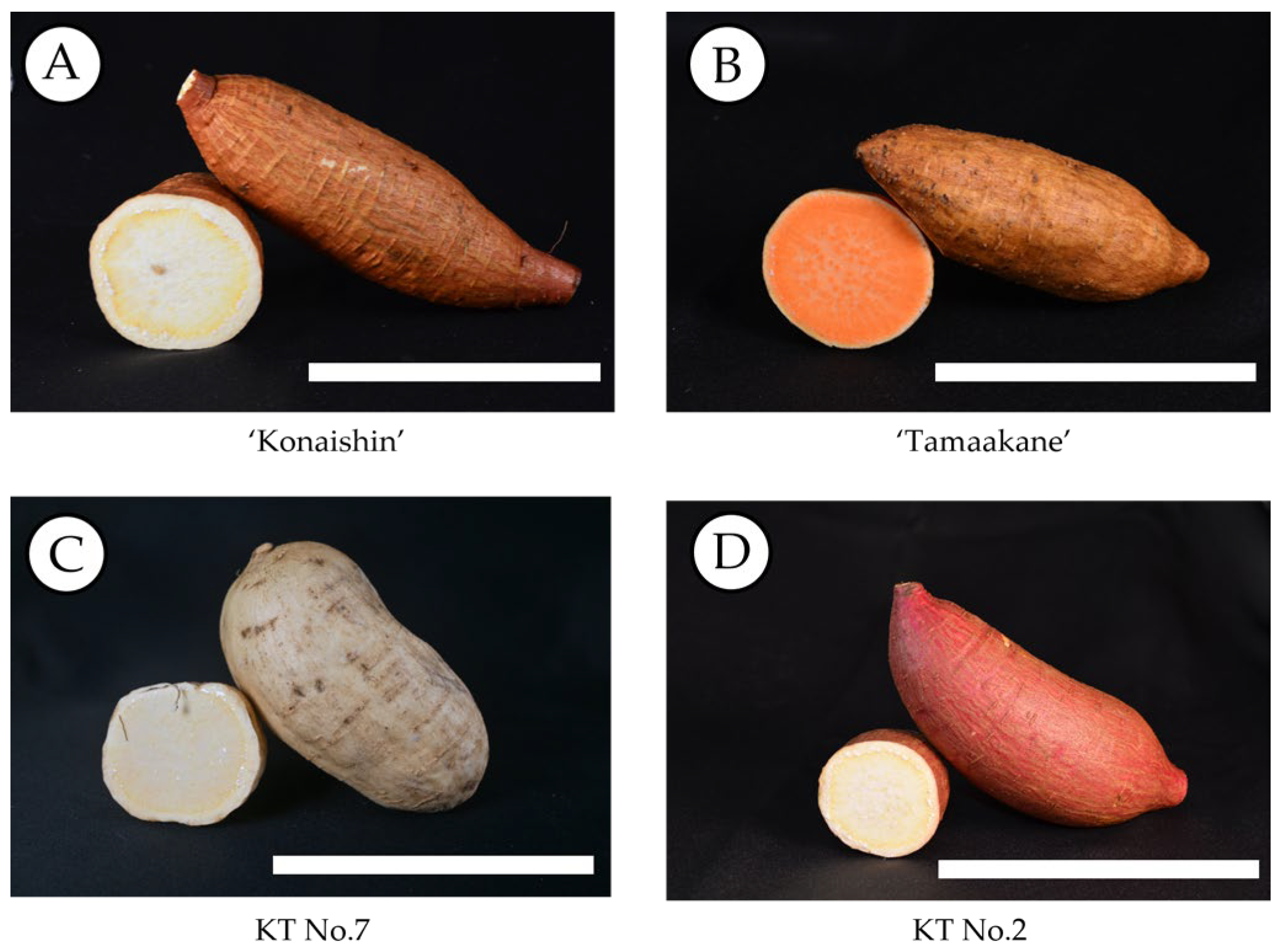

2.1. Plant Materials

Four sweet potato cultivars were used throughout this experiment: ‘Tamaakane’, ‘Konaishin’, ‘Kokei No. 14’, and ‘Beniharuka’. These cultivars were selected based on known information on foot rot ecology and control measures [

22]. ‘Tamaakane’ (strong) and ‘Konaishin’ (slightly strong) show moderate resistance to foot rot, whereas ‘Kokei No. 14’ (slightly weak) and ‘Beniharuka’ (weak) are susceptible. As far as we are aware, no sweet potato cultivars grown in Japan have been confirmed to be completely free from foot rot infection. ‘Tamaakane’ and ‘Konaishin’ were used as breeding materials, while ‘Beniharuka’ and ‘Kokei No. 14’ were used as control cultivars for evaluating disease resistance and productivity in subsequent generations.

2.2. Crossing

Crossing was conducted using ‘Konaishin’ as the seed parent and ‘Tamaakane’ as the pollen parent according to the method described by Nakagawa et al. [

23], in the research greenhouse at the Research Institute for Bioresources and Biotechnology, Ishikawa Prefectural University (36°30′20.1″ N, 136°35′43″ E). To induce flowering,

Ipomoea nil Kidachi was used as the rootstock, and the two cultivars were used as scions for grafting. These grafted plants were cultivated in a greenhouse under natural light at 15–25 °C. All side shoots of the

Ipomoea nil Kidachi rootstock were removed, and the main stem was grown to a length of approximately 300 mm and cultivated until it had more than 10 unfolded leaves.

Grafting was performed using the cleft grafting method. Flowering was observed approximately six weeks after grafting. Anthers including pollen were artificially removed from the flowers of ‘Tamaakane’ using sharp-tipped tweezers, and the collected anthers were applied to the stigma of ‘Konaishin’ to perform cross-pollination. The cross-pollination was conducted from September to October 2021, resulting in the acquisition of 17 seeds. In December 2021, the hybrid seeds were treated with sulfuric acid, thoroughly washed with water immediately after treatment, and planted in 10.5 cm diameter pots containing commercially available artificial potting soil (Nafco Co., Fukuoka, Japan). Ultimately, 15 hybrids were obtained and numbered from KT No. 1 to KT No. 15.

2.3. Cultivation Trials of Hybrids

Fourteen hybrids of ‘Konaishin’ and ‘Tamaakane’ (one strain died during seedling cultivation) were propagated by cuttings into three to five plants each and cultivated at an experimental farm at Kushima AoiFarm Co. in Kushima City, Miyazaki prefecture (31°33′30.6″ N, 131°14’45.7″ E). Fifty plants each of ‘Konaishin’ and ‘Tamaakane’ were planted as controls. After fertilization, the andosol soil contained ammonia nitrogen at 1.9 mg 100 g

−1, nitrate nitrogen at 0.32 mg 100 g

−1, effective phosphoric acid at 28.7 mg 100 g

−1, and exchangeable potassium at 42.0 mg 100 g

−1 and had a pH of 5.9. Detailed cultivation practices such as irrigation and pesticide application were carried out using methods partially modified from the South Kyushu Region Sweet Potato Cultivation Guidelines (

https://www.alic.go.jp/starch/japan/example/200712-03.html, accessed on 20 November 2025) published by the National Agriculture & Livestock Industries Corporation. Each cutting was transplanted on 22 May 2022 at a planting density of 0.84 m × 0.30 m. To check the yield and size of the storage roots, we harvested them at the end of October 2022. Sampling of stems and storage roots from the trial-cultivated plants was conducted randomly to avoid field location and edge effects.

2.4. Stem Polyphenol Analysis

Stem samples of the hybrids of ‘Konaishin’ and ‘Tamaakane’ (KT No. 2 to No. 15) and their parents were collected up to approximately 40 cm from the base of three plants, using the method described by Setoguchi et al. [

9] (

Figure 1). The collected samples were frozen at −30 °C immediately after collection, lyophilized (FUD-1100, Tokyo Rikakikai, Tokyo, Japan), ground, and stored at −30 °C until analysis. The total polyphenol content of stems from different cultivars was determined using the Folin–Ciocalteu method [

24].

First, 0.02 g of lyophilized powder was weighed, and 5 mL of 80% methanol was added. The powder was then extracted for 15 min in an ultrasonic generator. The extraction was filtered through a 0.20 µm syringe filter. Phenol and saturated sodium carbonate reagents were added to the extract and allowed to stand at room temperature for 30 min, after which the absorbance was measured at 760 nm by spectrophotometry. Standard solutions of 20, 50, 100, 150, and 200 mg L−1 were prepared using gallic acid as a sample. The results are expressed as the equivalent of gallic acid per 100 g of fresh weight (FW). Three biological replicates were performed for each treatment.

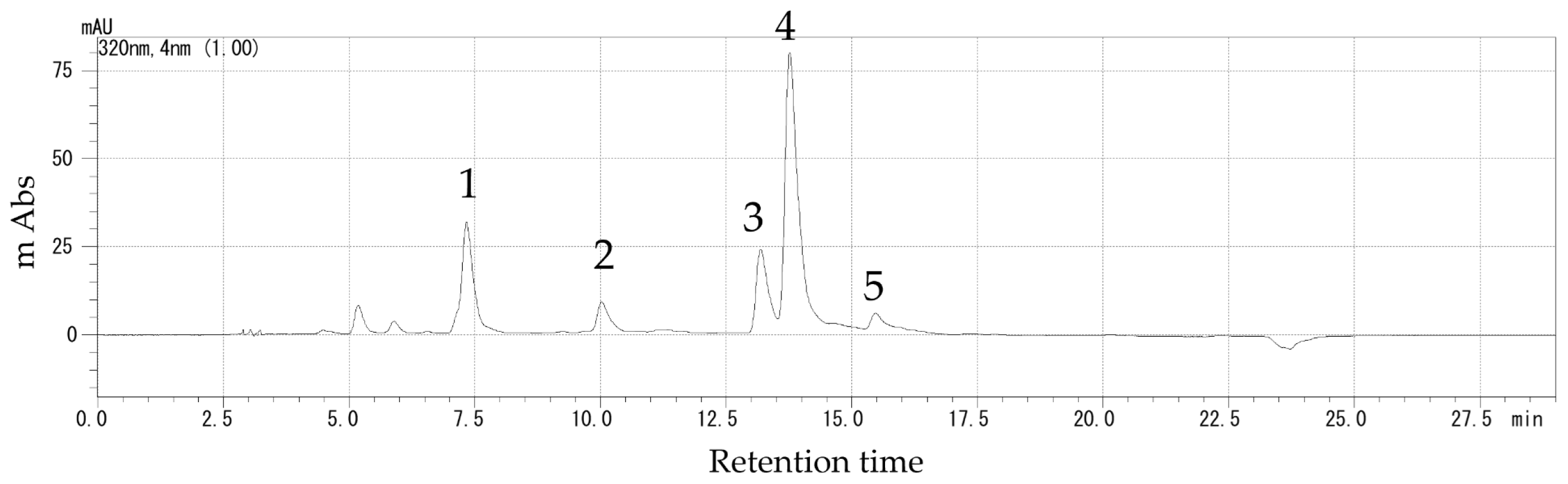

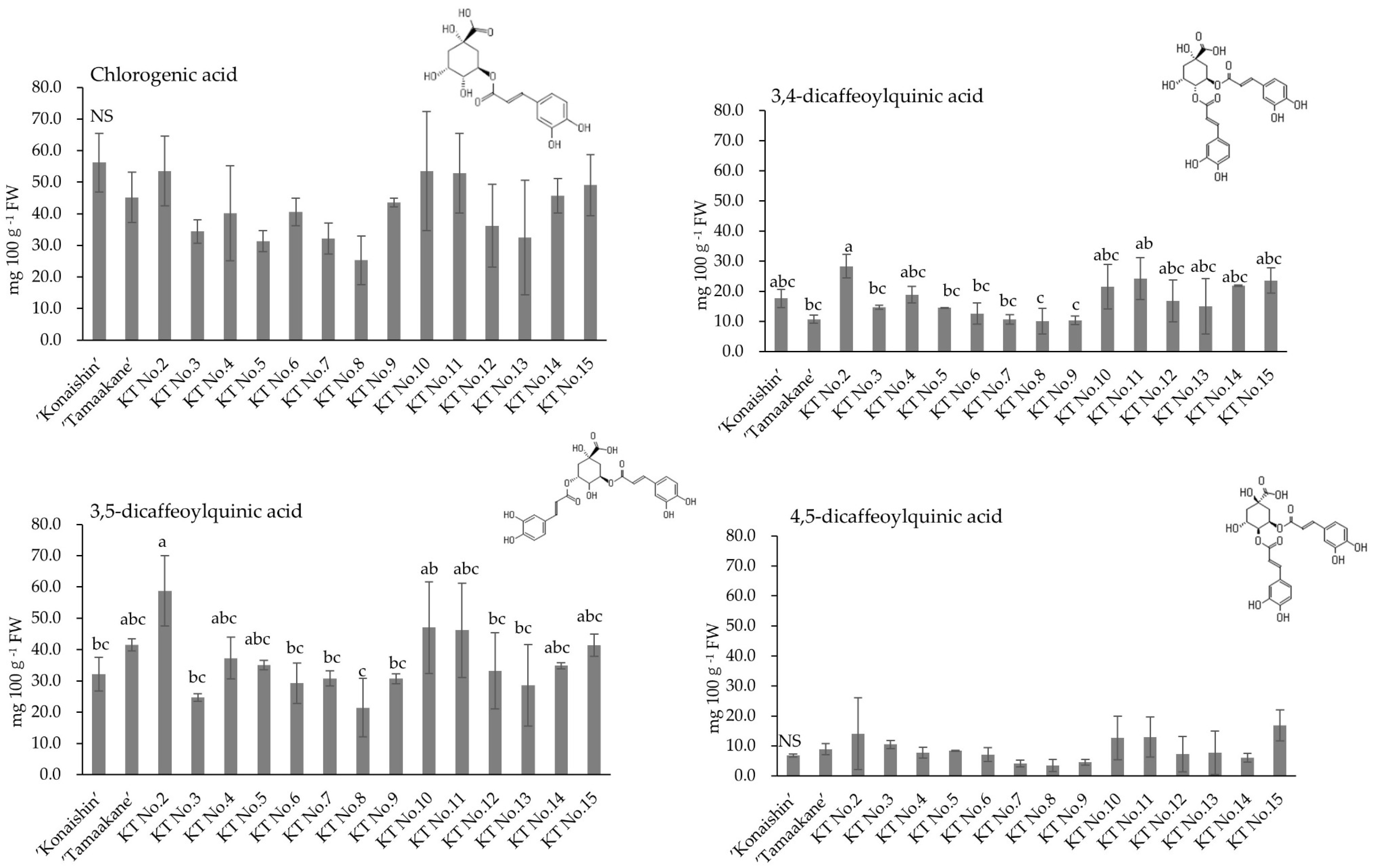

To further investigate the polyphenols in the stems, we used high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) to determine the polyphenol composition [

25]. Polyphenols were extracted using the same method as described above for measuring total polyphenol content. The extracts were analyzed by reversed-phase HPLC using a Prominence LC solution system and an ODS-3 column (particle size 5.0 μm, inner dia. 4.6 mm × length 250 mm; Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan). The mobile phases were A: 100% ethanol, B: 20 mM KH2PO4 (pH 2.4). The binary gradient was as follows: 85–68%B (0–12 min), 68%B (12–15 min), 50–55%B (15–20 min), and 85%B (20–29 min). The column temperature was maintained at 40 °C, the detection wavelength was 320 nm, and the flow rate was 1.0 mL·min

−1. Chlorogenic acid, caffeic acid, 3,4-dicaffeoylquinic acid, 3,5-dicaffeoylquinic acid, and 4,5-dicaffeoylquinic acid were identified by comparing the retention times and spectra with pure standards. The results are expressed in mg 100 g

−1 FW, and the respective percentages were calculated (

Figure 2). Three biological replicates were performed for each treatment.

2.5. Foot Rot Inoculation

To investigate the resistance of the hybrids of ‘Konaishin’ and ‘Tamaakane’ (KT No. 2 to No. 15) and their parents to foot rot, we conducted an inoculation test using potted nurseries of each hybrid, following the method of Setoguchi et al. [

9]. In addition, ‘Konaishin’ and ‘Tamaakane’, the parents of these hybrids, were tested as controls. Cuttings of these cultivars were collected from the field on 2 September 2021, and transplanted into 10.5 cm diameter black pots on the same day. Nurseries were grown in an unheated glass greenhouse and used for the test once they reached a height of approximately 30 cm (5 nodes or more).

The foot rot was inoculated by making a small cut in the base of the stem (approximately 2 cm above the ground) using a toothpick. The experiment began on 20 September 2022, and the nursery plants were grown in an unheated greenhouse for five weeks. Six strains of foot rot pathogen that we had labeled A to F were used, which were collected from diseased sweet potato plants or storage roots in sweet potato fields in Miyazaki and Kagoshima prefectures (

Table 1). Five weeks after inoculation, disease severity was evaluated using the criteria described in

Table 2 on a scale of 0 to 5. Disease severity was calculated from the disease index using the following formula:

Three biological replicates were tested.

Table 1.

List of foot rot (Diaporthe destruens) isolated from sweet potato cultivated in the southern Kyushu region used in this study.

Table 1.

List of foot rot (Diaporthe destruens) isolated from sweet potato cultivated in the southern Kyushu region used in this study.

| Strain z | Sweet Potato Cultivars from Which the Fungus Was Isolated | Organ | Sampling Site |

|---|

| A | ‘Koganesengan’ | stem | Kanoya-shi, Kagoshima |

| B | ‘Shiroyutaka’ | stem | Kanoya-shi, Kagoshima |

| C | ‘Koganesengan’ | stem | Kanoya-shi, Kagoshima |

| D | Unclear | storage root | Miyazaki-shi, Miyazaki |

| E | Unclear | storage root | Miyakonojo-shi, Miyazaki |

| F | Unclear | stem | Miyazaki-shi, Miyazaki |

Table 2.

Evaluation criteria based on symptoms observed after inoculation with foot rot (Diaporthe destruens) using potted sweet potato nurseries.

Table 2.

Evaluation criteria based on symptoms observed after inoculation with foot rot (Diaporthe destruens) using potted sweet potato nurseries.

| Evaluation Criteria | Symptoms After Infection with Foot Rot |

|---|

| 0 | No symptoms |

| 1 | Only the inoculation site was browned |

| 2 | Disease progresses within 3 nodes |

| 3 | Disease progresses beyond 3 nodes |

| 4 | Disease develops on the entire plant but plant does not die |

| 5 | Plant dies |

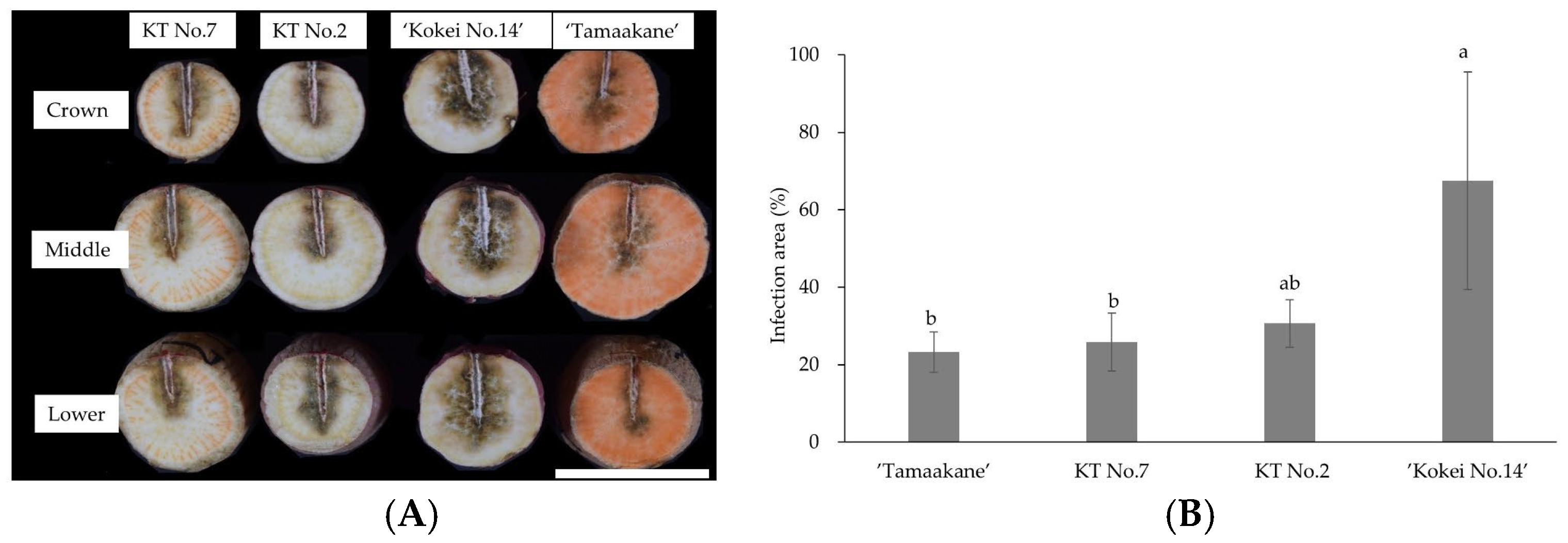

Inoculation tests were conducted using storage roots of KT No. 7 (which had been evaluated as having “strong” resistance to foot rot) and KT No. 2 (which had been evaluated as having “weak” resistance) based on inoculation tests on stems described above. Storage roots of ‘Tamaakane’ (which is highly resistant to foot rot) and ‘Kokei No. 14’ (weakly resistant to foot rot) were used as controls.

For the tests, moderately sized storage roots were selected from each strain and carefully washed. Strain E of foot rot fungus was then attached to a sterilized toothpick and inoculated by inserting approximately 2 cm into the side of the storage root at three sites per storage root: a crown site, a middle site, and a lower site. The inoculated storage roots were cultured in an artificial climate chamber (Cool Incubator A1201-2V, Ikuta Industry Co., Osaka, Japan) maintained at 28 °C and 85% humidity. After six days of culture, the inoculation sites on the storage roots were cut with a knife, and the blackened infected area was manually selected using the polygon tool in ImageJ 1.54g software [

27]. The infected area for each cultivar and hybrid was calculated by dividing the infected area by the total area and multiplying by 100.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

All experimental data were obtained from triplicate measurements (three extracts from three independent plants, three measurements per extract), and the data in the figures are the means ± standard deviation. Multiple comparisons were performed using Tukey’s multiple range test or the Games-Howell test with Excel 4.09 Statistics.

4. Discussion

To protect themselves from biological stress, plants have developed various sensory systems [

28]. As a result, they have evolved a rich array of defense mechanisms to combat diverse pathogens and pests including viruses, nematodes, bacteria, fungi, and herbivorous insects [

29]. One of the key components of these defense mechanisms is polyphenols, which are secondary metabolites with diverse functions that mitigate biological stresses [

30].

Recently, Setoguchi et al. [

9] focused on polyphenols in the stems, the main infection site of foot rot in the field and proposed that polyphenols could be a potential selection marker for foot rot resistance based on a unique fungal strategy that differed from those described in previous reports. They revealed that cultivars with low stem polyphenol content exhibit low susceptibility to foot rot, whereas cultivars with high stem polyphenol content show high susceptibility. Furthermore, they reported strong positive correlations between susceptibility to foot rot and several polyphenols, including 3,4-dicaffeoylquinic acid and chlorogenic acid. In this study, we aimed to verify whether foot-rot-resistant sweet potato lines could be selected by growing seedlings from crosses of sweet potato cultivars and analyzing their stem polyphenols.

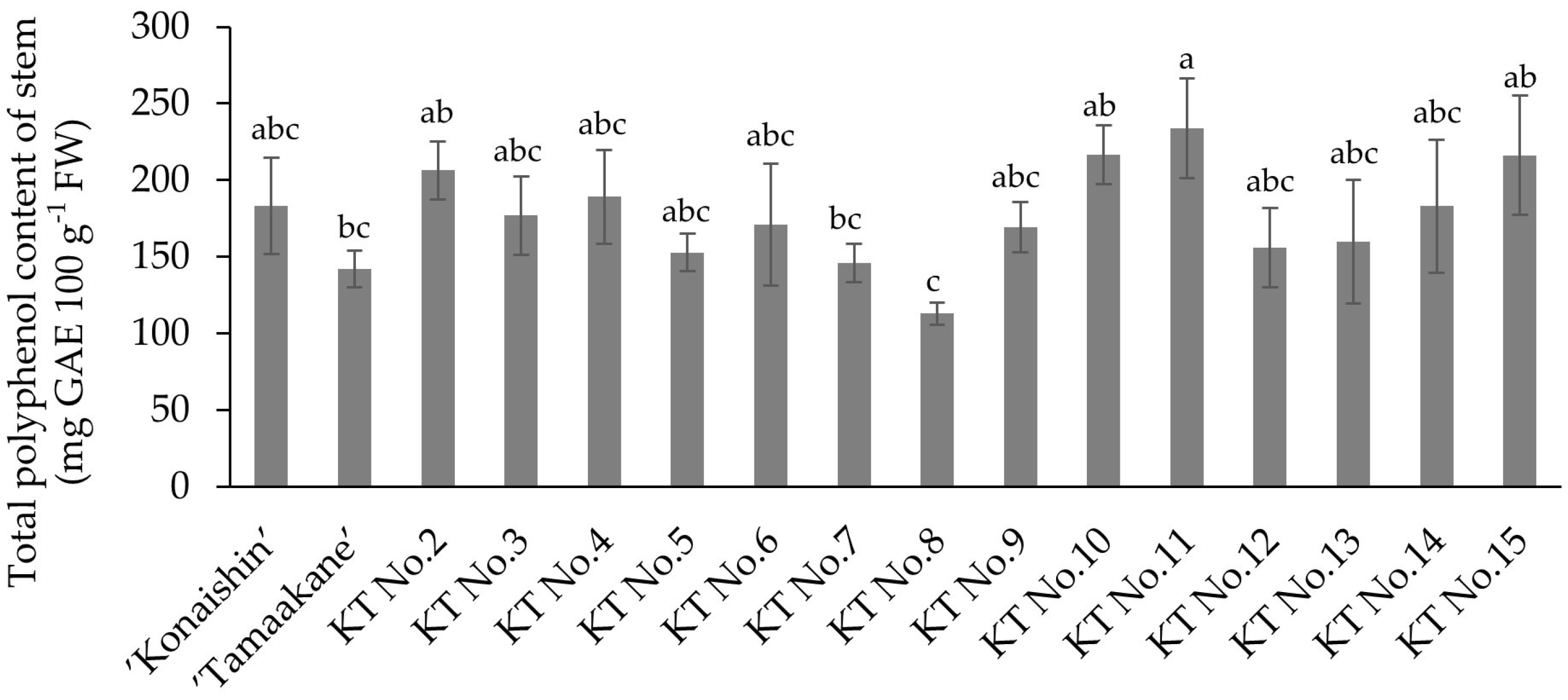

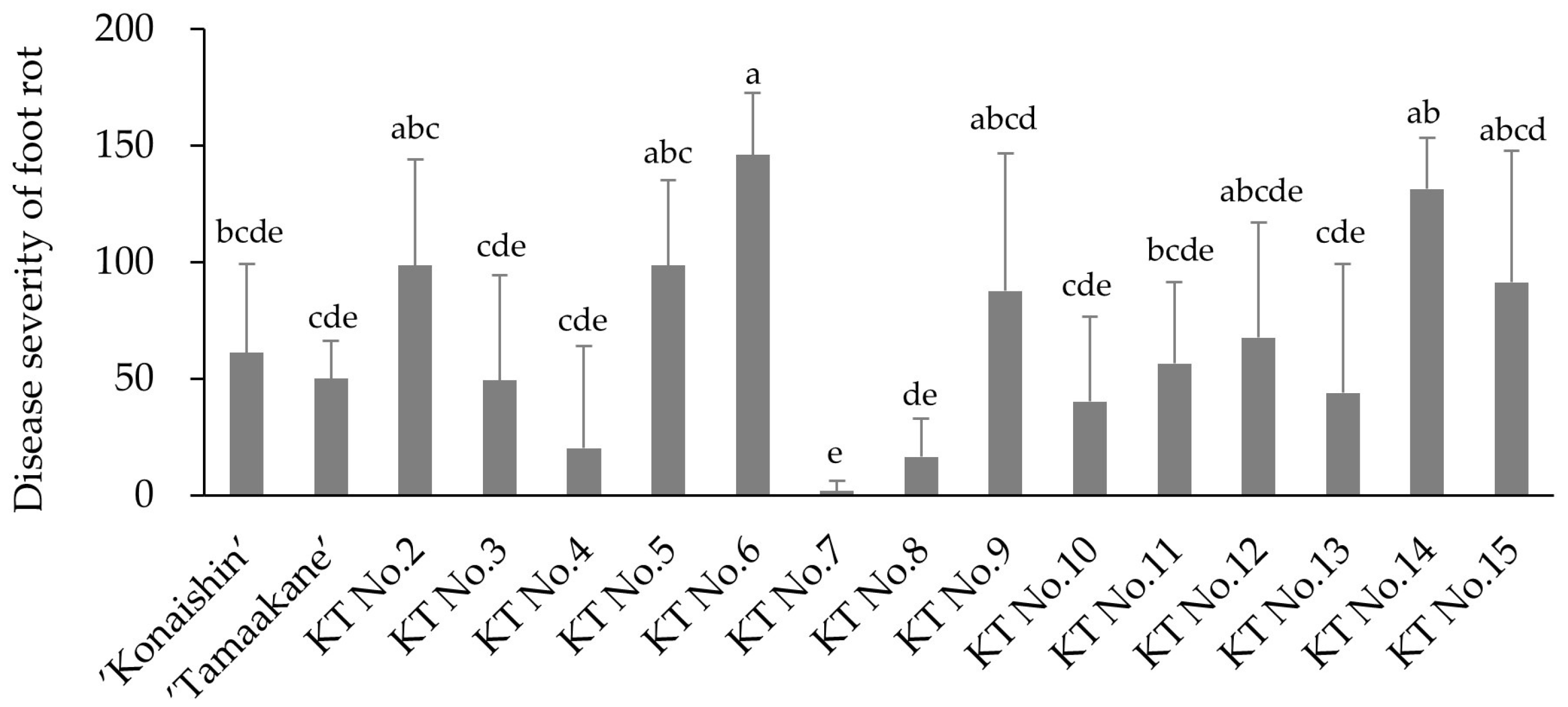

The 14 hybrids derived from ‘Konaishin’ and ‘Tamaakane’, which are reported to be resistant to foot rot, showed a wide range in both total polyphenol content and resistance to foot rot. Among these hybrids, KT No. 7, which has a low total polyphenol content in the stems, had the lowest disease severity value after direct inoculation with foot rot fungus. This result is consistent with the trend reported by Setoguchi et al. [

9] and suggests that stem polyphenols could serve as a preliminary indicator of foot rot resistance. However, not all hybrids showed the same tendency. For example, KT No. 8 also had a low stem polyphenol content, whereas KT No. 11 had the highest among the hybrids, but their disease severity values were not consistent with their polyphenol level. These findings indicate that the relationship between stem polyphenol content and foot rot resistance is not always straightforward, and that polyphenol content should be regarded as a supportive rather than decisive indicator in the selection of resistant lines.

Setoguchi et al. [

9] also conducted in vitro growth tests using media supplemented with polyphenols and found that low concentrations of chlorogenic acid-supplemented media promoted the growth of the foot rot fungus, suggesting that the pathogen may metabolize chlorogenic acid as a nutrient source. Furthermore, although polyphenols such as chlorogenic acid contained in sweet potatoes vary depending on the organ and genotype, it is presumed that infection begins when the concentration of polyphenols such as chlorogenic acid in the stem reaches an optimal level for infection by the foot rot pathogen. In other words, it may be difficult for foot rot infection to develop in plant genotypes that have a low polyphenol concentration in the stem (the main site of infection). In this study, KT No. 7, which had a low total polyphenol content in the stem, also showed resistance to foot rot. However, no significant correlation was found between the disease severity value of foot rot and the total polyphenol content, chlorogenic acid content, 3,4-dicaffeoylquinic acid content, or 3,5-dicaffeoylquinic acid content in any of the hybrids.

The concentrations and composition of phytochemicals such as polyphenols in plants are known to be affected by seasonal variations [

31,

32]. In particular, this has been reported to be due to variations in soil composition, seasonal responses to various pathogens, and environmental variables (abiotic factors) such as temperature and precipitation [

33,

34]. To minimize the influence of such environmental variability in the present study, all plant materials were cultivated under the same field conditions and managed using identical agronomic practices. In addition, stem samples from all lines were collected on the same day and at the same developmental stage to reduce temporal variation.

Using polyphenols, which are susceptible to such biological and non-biological influences, as markers may make it difficult to accurately determine the degree of disease resistance expression; however, using these polyphenol markers and comparing them with the control area under the same conditions, it is highly likely that only cultivars with strong disease resistance can be selected in the primary screening.

Generally, storage roots infected with sweet potato foot rot are characterized by dark brown discoloration that starts primarily from the crown site, becoming slightly hardened and decayed. Usui and Kushima [

35] established an experimental method to evaluate differences in infection capacity based on a four-level scale. This method involves infecting storage root sections with foot rot pathogens in vitro and assessing the degree of discoloration caused by infection of the storage roots. Furthermore, Kobayashi et al. [

36] evaluated foot rot resistance in contaminated areas by assessing the degree of blackening at the stem base and the frequency of healthy storage root weight at harvest for each strain.

As described above, evaluating storage root discoloration is considered a crucial indicator for assessing the degree of resistance to foot rot. To evaluate the infectivity of potato late blight disease caused by Phytophthora infestans, potato storage root sections are infected in vitro, and the disease lesion area indicating mycelial growth after an incubation period is used for assessment [

37]. Based on these findings, we established a method for meticulously evaluating the resistance of sweet potato to foot rot using sweet potato storage roots. However, to assess the degree of resistance in greater detail, further examination of experimental conditions such as culture environment, inoculation site, and the growth stage of storage roots is required.

The key breeding objectives for table use cultivars are excellent taste, good appearance, disease and pest resistance, and high yield. In addition, breeding programs for cultivars suitable for food processing as starch-producing cultivars have also been actively promoted [

38]. The breeding parents used in this study, ‘Konaishin’ and ‘Tamaakane’, are relatively resistant to foot rot disease and are used as raw material for starch and shochu (Japanese distilled liquor), respectively. Although the starch characteristics of KT No. 7 selected in this study were not investigated, this line showed storage root yield and storage root morphology similar to those of ‘Konaishin’. Therefore, KT No. 7 has potential as a breeding material for starch production with high resistance to foot rot.

As described above, the selection method using stem polyphenols as markers [

9] successfully selected hybrid lines with foot rot resistance comparable to that of ‘Tamaakane’, demonstrating the potential reliability of this technique. Furthermore, evaluation of the resistance to foot rot in storage roots of KT No. 7, which was selected as a candidate line with low polyphenol content, confirmed a resistance level equivalent to that of ‘Tamaakane’. These results indicate that the use of polyphenol markers in sweet potato breeding is a promising approach that enables easy and efficient primary selection using stems as test material.

In our population of 14 hybrid lines derived from ‘Konaishin’ and ‘Tamaakane’, we further evaluated the practical efficiency of using stem polyphenol content as a preliminary screening criterion. KT No. 8 and KT No. 7 showed the lowest total stem polyphenol contents (112.9 and 145.9 mg GAE 100 g−1 FW, respectively), and these two lines also exhibited the lowest disease severity values (16.4 and 1.8), indicating the strongest resistance in our inoculation tests. Therefore, by selecting only the lines with lower stem polyphenol contents, the number of candidates requiring inoculation testing could be reduced from 14 to 2, while still retaining the two most resistant lines. These results suggest that stem polyphenol profiling can serve as a practical and efficient pre-screening tool for enriching resistant candidates prior to inoculation testing.