Abstract

Cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.) is a globally important crop valued for both fresh consumption and processing, particularly in the United States. It was the first specialty crop among horticultural crops with a publicly available draft genome, providing a foundation for molecular breeding and trait discovery. However, cucumber production faces significant yield losses due to a wide range of biotic stresses. The crop is highly susceptible to fungal, viral, and bacterial pathogens throughout its lifecycle. To combat these challenges, breeders deploy conventional and contemporary breeding strategies to develop disease-resistant cultivars. Advances in high-throughput sequencing and genomic tools, such as quantitative trait loci mapping, genome-wide association studies, and genomic selection, have accelerated the identification and subsequent integration of resistance genes and loci into elite cucumber germplasm. This review highlights recent progress in resistance breeding for biotic stress management in cucumber, with a focus on major diseases caused by fungal, viral, and bacterial pathogens. It emphasizes the role of genomic tools, the discovery of key resistance genes and QTLs, and the potential of modern breeding approaches to improve crop resilience. Continued innovation and integration of emerging technologies will be essential for developing durable, broad-spectrum resistance in future cucumber cultivars.

1. Introduction

The Cucurbitaceae family, known for its diverse fruit-bearing species, encompasses several economically important crops cultivated worldwide [1]. Among them, the cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.) stands out as the second most widely cultivated cucurbit, valued for its immature fruit, which is consumed fresh or processed [2]. Cucumber is a diploid species with a chromosome number of 2n = 2x = 14, cultivated across tropical, subtropical, and temperate climates [3]. Cucumbers were domesticated from the Indo-Gangetic plains for traits such as reduced bitterness and improved fruit quality [4]. Over time, it spread to Europe and North America, becoming a widely grown crop known for its nutritional value, high water content, and traditional medicinal applications [5].

The Cucumis genus also includes other agriculturally significant species such as Cucumis melo (melon), Cucumis anguria (West Indian gherkin), and Cucumis metuliferus (kiwano), although these are generally cultivated on a smaller scale, often for ornamental purposes or specialty markets [6]. However, C. sativus has been adopted as a model species for sex determination studies due to its distinctive floral biology [7]. Typically, the flower is monoecious (bearing both male and female flowers), but gynoecious lines (producing only female flowers) are widely cultivated to enhance yield [8]. Interestingly, even in the absence of honeybees, parthenocarpic fruit development occurs in 30–36% of flowers [9]. Plants are fast-growing and yield 20–25 pounds of fruit per plant within 50–70 days of planting [10]. Fruit quality is mainly determined by its shape, size, skin texture, and internal flesh structure [11,12]. Nutritionally, fruit contains 96.4% water and minimal levels of protein, fat, vitamin B, and useful enzymes like proteases and ascorbate oxidase. In addition, they contain natural compounds such as cucurbitacin, which have anti-inflammatory and potential anti-cancer benefits, adding to their nutritional and medicinal value [13].

Globally, cucumbers and gherkins are key horticultural commodities, with China leading production at over 22.9 million tonnes annually [14]. In the US, major production occurs in Michigan, Florida, North Carolina, Texas, California, and Georgia, with Michigan as the top producer, followed by Florida. Although the global market is projected to reach USD 1.96 billion by 2030 with a 4.4% compound annual growth rate (CAGR) [15], the US fresh cucumber [16] market output declined sharply, from 1.087 billion to 314 million pounds between 2000 and 2020, a >70% drop [17,18]. This reduction reflects rising labor costs, postharvest losses, environmental stress, and most critically, biotic and abiotic pressures limiting productivity and sustainability.

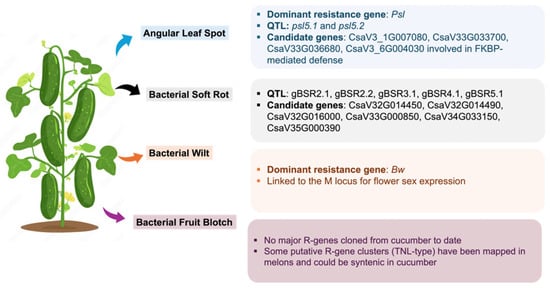

Globally, biotic stresses cause major yield losses, estimated at 30% in rice, 22.5% in maize, 21.5% in wheat, 21.4% in soybean, 17.2% in potato, and 50–80% in cucumber [19,20]. Diseases caused by fungal and oomycete pathogens are among the most damaging, including downy mildew (DM), powdery mildew (PM), anthracnose, scab, leaf spot, gummy stem blight (GSB), fusarium wilt (FW), and phytophthora fruit rot [21]. These diseases contribute to severe foliar damage, fruit rot, and, in extreme cases, complete plant collapse, resulting in significant economic losses [21]. Alongside fungal pathogens, aphid-transmitted viruses such as cucumber mosaic virus (CMV), cucumber green mottle mosaic virus (CGMMV), watermelon mosaic virus (WMV), zucchini yellow mosaic virus (ZYMV), and papaya ringspot virus (PRSV), and bacterial diseases like angular leaf spot (ALS), bacterial soft rot (BSR), bacterial wilt (BW), and bacterial fruit blotch (BFB) are also responsible for substantial reduction in yield [21].

In response to these challenges, disease resistance is a major goal in the cucumber breeding program. Traditional methods such as mass selection and hybrid development have produced resistant cultivars but are limited by long breeding cycles and environmental variability. In recent decades, molecular tools have revolutionized cucumber breeding with the advent of marker-assisted selection (MAS), quantitative trait locus (QTL) mapping, and genome-wide association studies (GWAS), which have significantly enhanced the precision and speed of selecting resistant genotypes [22]. The availability of a high-quality cucumber reference genome and extensive genomic resources has accelerated the discovery of resistance genes and alleles by integrating omics technologies. Advanced genome editing technologies such as CRISPR/Cas9, base editing, and prime editing are now being explored for targeted modification of susceptibility genes (S-genes) or the introduction of novel resistance alleles [23]. This review aims to synthesize current knowledge on breeding for disease resistance in cucumber, focusing on fungal, viral, and bacterial pathogens. It explores both classical and molecular approaches, highlights key discoveries in resistance loci, and evaluates the application of emerging tools such as gene editing and omic-assisted breeding to accelerate the development of durable, broad-spectrum resistance in cucumber.

2. Genetic Resources

Plant genetic resources (landraces, wild relatives, and diverse cultivars) are the foundation for improving yield and resilience to biotic stress in cucumber. Harnessing this diversity enables the discovery and introgression of qualitative and quantitative resistance loci into elite lines. By characterizing genetic diversity, population structure, and linkage disequilibrium, breeders can pinpoint novel alleles linked to key pathogens. In the following sections, we delve into the characterization and utilization of cucumber germplasm, dissect the structure and breadth of its gene pool, and explore the genomic resources and database platforms that underpin modern breeding strategies.

2.1. Germplasm Resources

Exploitable allelic diversity is fundamental to crop improvement; curated cucumber germplasm collections enable discovery and deployment of trait-associated alleles for disease resistance, yield, and quality, providing the genetic foundation for resilient cultivar development. Globally, there are over 1750 gene banks dedicated to conserving plant genetic resources [24,25]. Various gene banks, including the N.I. Vavilov Research Institute of Plant Industry (St. Petersburg, Russia) [26], the International Plant Genetic Resources Institute (IPGRI), Rome, Italy [27], The United States National Plant Germplasm System (NPGS) maintains web-based Germplasm Resources Information (GRIN), Washington, DC, USA (http://www.ars-grin.gov), accessed on 10 November 2025 [28], the National Agriculture and Food Research Organization (NARO), Tsukuba, Ibaraki, Japan (https://www.naro.affrc.go.jp/archive/nias/eng/genresources/index.html, accessed on 19 November 2025), accessed on 10 November 2025 [29], and the Crop Germplasm Resources Institute (CGRI), Beijing, China) [30] contribute to the long-term conservation and utilization of valuable accessions. Among these, the US holds the largest cucumber collection, with the NPGS playing a central role in maintaining and distributing accessions for breeding purposes [28]. The NPGS GRIN database maintains extensive phenotypic records for Cucumis species, comprising cultivars, landraces, and varieties collected globally [28]. The NPGS maintains its cucumber collection at its Ames, Iowa, facility, which comprises 1314 cucumber accessions [25]. These accessions are primarily classified into eight geographic groups based on their countries of origin: India/South Asia (216), East Asia (293), Central/West Asia (113), Turkey (161), Europe (314), Africa (33), North America (97), and 7 from other regions. The Indian/South Asian group includes 184 accessions from India and 32 Plant Introductions (PIs) from surrounding regions such as Bhutan, Malaysia, Nepal, Myanmar, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, and Thailand [31,32]. These collections are indispensable for dissecting genetic diversity and identifying loci underlying key agronomic traits. Multiple accessions contribute to resistance in cucumber breeding; PI 197087 is among the most prominent used donors, particularly in DM and anthracnose. Lv et al. utilized a large collection of 3342 accessions obtained from the national germplasm center in China, the Netherlands, and the US to investigate genetic diversity using 23 highly polymorphic simple sequence repeat (SSR) markers [33]. Similarly, a GWAS was done using 1234 cucumber (C. sativus) accessions from the NPGS collection, which revealed patterns of genetic diversity and relationships within the collection [34].

2.2. Cucumber Gene Pool

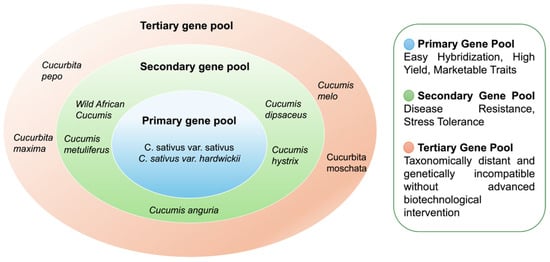

Crop wild relatives (CWR) are crucial sources of genetic variation for improving cultivated species. Cucumber germplasm resources are categorized into primary (GP-1), secondary (GP-2), and tertiary (GP-3) gene pools based on cross-compatibility and genetic relationships (Figure 1) [35,36]. Exploiting the genetic variation present across these pools enables breeders to introduce novel alleles into cultivated varieties, thereby enhancing adaptability, productivity, and resilience to biotic and abiotic stresses [37]. However, successful hybridization between cultivated cucumber and its wild relatives remains challenging. The GP-1 encompasses Cucumis sativus var. sativus and its wild progenitor, Cucumis sativus var. hardwickii accessions (1320 accessions at NPGS) [28]. These accessions include elite cultivars, breeding lines, and heirlooms. While this pool is the most accessible for breeding due to high cross-compatibility, it remains genetically narrow because of domestication bottlenecks and the reliance on small founder populations [38,39]. In contrast, GP-2 includes wild African varieties (often cross-incompatible) and Cucumis hystrix (rarely cross-compatible), presenting a greater challenge for gene introgression [40]. The GP-3 consists of general species that are distantly related, including Cucumis melo L. and Cucurbita L., which are not cross-compatible [40,41,42].

Figure 1.

Gene pool hierarchy of Cucumis sativus: Primary, Secondary, and Tertiary sources of genetic diversity.

Despite the challenges, the resistance to cucumber green mottle mosaic virus, Javanese root-knot nematode, and scab has been successfully introgressed from wild relatives (Cucumis sativus var. Hardwickii) to cultivated cucumber [43,44,45]. Limited success has been achieved from crosses involving the GP-2. For example, sterile hybrids were obtained from crosses with Cucumis hystrix, resulting in Cucumis hytivus [46,47]. With recent genomic advancements, cucumber pan-genome sequencing has provided valuable insights about the potential use of wild accessions for breeding and genetic studies. Leveraging chromosome-level assemblies, approximately 4.3 million genetic variants, including 56,214 structural variants (SVs), were identified [48]. Harnessing such genetic diversity across the entire cucumber gene pool is therefore crucial for breeding resilient cultivars that can withstand emerging pathogens and secure future food production.

2.3. Genome Sequencing and Database Resources

Genomic repositories and databases that host reference assemblies of cultivated varieties and wild relatives, along with multi-omics datasets, gene expression profiles, genome browsers, and genome editing tools, serve as essential platforms for marker development, gene discovery, trait mapping, population genomics, and molecular breeding in cucumber. The cucumber genome (diploid) is relatively small, with an estimated size of 367 Mb based on flow cytometry [49]. Several international research initiatives, including the International Cucurbit Genomics Initiative (ICuGI) and the United States Department of Agriculture—Agricultural Research Service (USDA-ARS) at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, have advanced cucumber breeding and genomics through next-generation sequencing (NGS). So far, only a few cucumber genotypes have been sequenced, including the East Asian cultivar ‘Chinese Long’ (9930), the North European cultivar B10, the North American cultivar Gy14, and one wild relative, C. hystrix [50,51,52,53].

The Chinese long (9930) genome, sequenced at 72.2X coverage, produced a 243.5 Mbp assembly that shows strong collinearity with melon, establishing cucumber as an important resource for comparative genomics [50,54]. Similarly, the North European cultivar B10 was sequenced using the Sanger method, resulting in a ~342 Mbp genome [52,55]. In North America, the Gy14 line, valued for its gynoecious flowering and desirable horticultural traits, was assembled to 203 Mbp, comprising 4322 scaffolds [51,52]. Comparative studies among these cultivated genomes reveal more than 90% protein sequence identity [55]. Beyond cultivated varieties, the wild relative C. hystrix has been sequenced, resulting in a chromosome-scale genome assembly of 289 Mbp with over 90% of sequences anchored onto 12 chromosomes [53]. This wild species harbors nucleotide-binding site (NBS) resistance genes that confer strong resistance against biotic stresses like DM and root-knot nematode. A chromosome-level assembly of C. sativus cv. ‘Tokiwa,’ using Oxford Nanopore sequencing, is 20% longer and contains 10% more annotated genes compared to existing genomes [56]. However, NGS still struggles to fully detect structural variants (SVs).

Several genomic databases are available online to provide comprehensive access to cucumber genome assemblies and associated data. Major platforms include Cucumber-DB, CuGenDB, CuGenDBv2, NCBI Assembly, the Weng Lab Database, and the JGI Genome Portal (Table 1) [57]. The Cucumber-DB hosts 12 genome assemblies, variant data, expression atlases, and analysis tools such as JBrowse2, Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST), primer design, and CRISPR modules. CuGenDBv2 currently contains 34 genome assemblies from 27 cucurbit species, facilitating comparative and functional genomics research [58]. The NCBI Assembly database offers chromosome-level assemblies such as Cucumber9930V3, while the Weng Lab and JGI portals provide reference genomes and BLAST search tools for widely used lines like ‘9930’ and Gy14 [59]. Collectively, these repositories provide curated genomic resources and serve as essential tools for advancing molecular breeding, enabling precise marker development, gene discovery, trait dissection, population genomics, and the development of improved cucumber cultivars.

Table 1.

Key genomic databases for cucumber with reference assemblies, features, data accessibility, and analysis tools (all database information verified and last accessed on 10 November 2025).

3. Host-Pathogen Interaction Mechanisms

Plant diseases are broadly classified as infectious or non-infectious. Non-infectious diseases result from unfavorable environmental conditions and do not spread between plants, while infectious diseases, caused by fungi, bacteria, or viruses, are transmissible and account for major yield and economic losses. Disease development depends on the presence of a susceptible host, a virulent pathogen, and favorable environmental conditions, the concept known as the classic disease triangle [62]. Pathogens enter plants through various routes, such as direct penetration by fungi or through wounds, stomata, or insect vectors in the case of viruses and bacteria [63]. To counter infection, plants rely on both constitutive and inducible defense mechanisms. Constitutive defenses include structural barriers such as the waxy cuticle, lignified cell walls, and preformed antimicrobial compounds. Inducible defenses are activated upon pathogen recognition [62]. The first layer, pattern-triggered immunity (PTI), is initiated when pattern-recognition receptors (PRRs) detect conserved pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs). The second layer, effector-triggered immunity (ETI), involves intracellular nucleotide-binding leucine-rich repeat (NLR) receptors that recognize specific pathogen effectors, often leading to a localized hypersensitive response (HR) [62,64,65]. These immune responses are coordinated through calcium signaling, mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) cascades, and hormone pathways involving salicylic acid (SA), jasmonic acid (JA), and ethylene (ET) [66]. Defense outputs include the production of antimicrobial peptides, phytoalexins, reactive oxygen species (ROS), and RNA interference (RNAi) mechanisms that target viral genomes. Long-term protection is reinforced through systemic acquired resistance (SAR) and induced systemic resistance (ISR) [66].

Fungal pathogens typically invade from the plant surface using specialized structures such as appressoria and enzymes that degrade the cell wall. They secrete effectors to suppress PTI and manipulate host signaling [67]. Biotrophic fungi avoid triggering HR to maintain host cell viability, while necrotrophs promote cell death to release nutrients. The viral pathogens replicate intracellularly and evade host RNA silencing by producing viral suppressors of RNA silencing (VSRs) that block small RNA pathways [67]. Moreover, bacterial pathogens, particularly Gram-negative species, utilize the type III secretion system (T3SS) to deliver effectors into host cells, suppressing PTI and ETI and altering hormone signaling [67].

Integrated cucumber defense relies on the coordination of PTI and ETI, regulated by hormone crosstalk (SA–JA–ET) and MAPK activation [65]. Key regulators include CsNPR1 (SA pathway), transcription factors CsWRKY33 and CsMYB44, metabolic genes like CsPAL, and pathogenesis-related proteins such as CsPR1. RNAi components (CsAGO1, CsDCL2, CsRDR1) further enhance antiviral protection. Host cell death plays a pivotal role in resistance. The HR, a form of programmed cell death triggered by ETI, restricts pathogen spread through ROS accumulation and PR gene activation. In cucumber, HR is essential for defense against P. xanthii and P. syringae [67]. Transcriptomic analyses of P. xanthii have identified 53–87 candidate secreted effector proteins (CSEPs) expressed during early infection [68]. Beyond immune signaling, the STAY-GREEN (SGR) gene encodes a chloroplast Mg-dechelatase that links chlorophyll degradation to plant immunity. Beyond senescence, SGR regulates defense by balancing ROS production and hormonal signaling during infection [65]. In Arabidopsis, its expression correlates with HR timing after Pseudomonas syringae challenge [69]. In cucumber, the recessive allele CsSGR impairs Mg-dechelatase activity, maintaining chlorophyll stability and enhancing resistance [70]. This mutation elevates SA and JA levels, induces defense genes (CsPR1, CsPAL, CsLOX), and strengthens HR confinement of pathogens [65]. Thus, CsSGR integrates chlorophyll metabolism with hormonal and ROS-mediated defenses for broad, durable resistance in cucumber [65].

4. Major Fungal and Oomycetes Diseases

Cucumber production is challenged by diverse fungal and oomycete pathogens, which include biotrophs that feed on living cells (e.g., Podosphaera xanthii) and hemibiotrophs that have a dual life cycle, first as biotrophs thriving on living tissue before turning necrotrophic and killing their host and feeding on dead tissue (e.g., Colletotrichum orbiculare, Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. cucumerinum, Phytophthora capsici, Corynespora cassiicola, and Pseudoperonospora cubensis). Despite varying life cycles, infection typically follows a similar pattern, beginning with establishing contact with host tissue, hydrating, sensing the surface, germinating, and penetrating via appressoria, stomata, wounds, or vascular entry points and releasing effectors to weaken immunity. These diseases collectively cause substantial yield losses: TLS ~20–70% in China, DM ~50–80% in Ukraine, PM ~50–70%, and GSB ~17–43% [71,72]. The following sections provide detailed insights into each major fungal disease, describing their host responses and current progress in developing resistant cultivars.

4.1. Downy Mildew

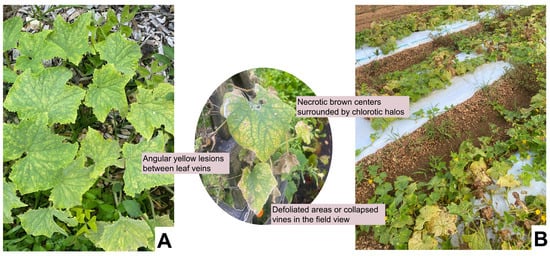

Downy mildew (DM), caused by the obligate biotroph Pseudoperonospora cubensis, is one of the most destructive diseases affecting cucumber production in humid regions [73]. Over the decades, this pathogen has been responsible for annual yield losses of up to 80% [74]. It exhibits a broad host range, infecting over 60 different plant species within the Cucurbitaceae family [73,75,76]. Symptoms typically begin as small, angular, chlorotic lesions delimited by veins on the adaxial leaf surface, which enlarge, turn from yellow to brown, become necrotic, and, in severe epidemics, lead to extensive defoliation and plant death (Figure 2) [77,78]. Sporulation of P. cubensis is favored by high relative humidity (>94%) and a dark period of >6 h, with optimal temperatures for infection around 15 °C [77,79]. Sporangia, dispersed by wind or water splashes, release biflagellate zoospores upon deposition on damp leaves; the zoospores move to stomatal apertures, encyst, and germinate, forming germ tubes that penetrate the leaf [80,81]. Beneath the stomata, a substomatal vesicle and intercellular hyphae are established; these hyphae form clavate haustoria in mesophyll cells for nutrient uptake and effector delivery that suppress host defenses [82,83]. Under favorable circumstances, sporangiophores then emerge via stomata, usually on the abaxial leaf surface, to generate additional sporangia, causing secondary spread [80]. The management for this historically relied on fungicide applications, using active ingredients such as cyazofamid, ametoctradin, propamocarb hydrochloride, and azoxystrobin [84]. However, fungicides offer only short-term protection and rarely provide lasting control, focusing on host resistance as the most reliable option.

Figure 2.

Foliar symptoms of downy mildew on cucumber under natural infection in the field. (A) Early infection showing angular yellow lesions confined by veins on the upper leaf surface, (B) field view illustrating widespread canopy yellowing, defoliation, and vine collapse under humid conditions. The inset highlights typical necrotic brown centers surrounded by chlorotic halos characteristic of disease progression (All photos clicked by author).

Developing resistant cultivars remains one of the most effective long-term strategies, reducing reliance on chemical control and supporting sustainable production. In 1946, Jenkins evaluated the line P.R. 37 for DM response and reported trait–disease associations without formal inheritance analysis [85]. Early breeding efforts in the US led to the release of the cultivar ‘Palmetto,’ but its resistance quickly broke down due to pathogen evolution or new race introduction. In 1954, PI 197087, an accession from India, was identified for its resistance to DM, which provided effective protection in the southeastern US for over four decades [86,87]. Subsequent genetic studies indicated predominantly recessive control of resistance in cucumber. Shimizu et al. showed that resistance in ‘Aojihai’ was governed by three recessive genes (s1, s2, s3) [88], and later work proposed that a single recessive gene (p) conditions resistance in ‘Poinsett,’ likely introgressed from PI 197087 [89]. The widely deployed dm-1 locus, first identified in PI 197087, became foundational in commercial breeding; molecular evidence links dm-1 to the CsSGR (stay-green) locus on chromosome 5 [90]. Over time, additional inheritance models were reported, including epistatic interactions and multigene control [91], and by 1990, some studies described resistance governed by interacting dominant and recessive genes [92].

Other findings indicated that resistance could be controlled by three recessive genes (dm-1, dm-2, and dm-3), where dm-3 and either dm-1 or dm-2 needed to be homozygous recessive for maximum resistance [93]. Multiple-resistant accessions, such as PI 197088, PI 605996 (India), and PI 330628 (Pakistan), were identified in large-scale screening [94]. IIHR-438 showed the highest resistance, followed by IIHR-433, while Swarna agethi and IIHR-431 were highly susceptible. Resistant genotypes exhibited significantly higher POD, PPO, SOD activities, and total phenol content [95].

Molecular breeding approaches have significantly advanced the identification of genetic loci associated with DM resistance, in which numerous QTLs have been identified using molecular markers such as SSRs and SNPs. A study using the F2:3 lines constructed from parents ‘WI 7120’ and ‘9930’ identified four QTLs, dm2.1, dm4.1, dm5.1, and dm6.1, associated with resistance based on a linkage map with 328 SSR and SNP markers. Among these, dm4.1 and dm5.1 exhibited major additive effects (R2 = 15–30%), indicating their significant contribution to resistance [96]. Another study utilized Bulked Segregant Analysis (BSA) in conjunction with NGS by using the ‘TH118FLM’ and ‘WMEJ’ as parents to construct F2:3 lines to detect five QTLs: dm2.2, dm4.1, dm5.1, dm5.2, and dm6.1. Within this set, dm2.2 demonstrated the most significant effect on DM resistance [97]. In a cross specifically designed between the resistant accession ‘PI 197088’ and the susceptible line ‘Changchunmici’, five QTLs were successfully mapped to chromosomes 1, 3, 4, and 5 using 141 SSR markers. Among these, dm4.1 consistently appeared across all experiments, accounting for 27% of the phenotypic variation in resistance. Other QTLs from this study, such as dm1.1 and dm5.2, exhibited moderate effects, while dm3.1 and dm5.1 were classified as minor-effect QTLs. The accession PI 197088 itself has been shown to possess polygenic resistance to DM [98].

Further, in-depth research has shown that DM4.1, once considered a single major QTL for DM resistance, is composed of three distinct sub-QTLs, each influencing specific disease symptoms. DM4.1.1 is primarily associated with pathogen-induced necrosis, a host cell death response linked to plant defense mechanisms. DM4.1.2 exerts an additive effect in reducing sporulation, a key stage in the pathogen’s life cycle, with fine mapping narrowing its interval to Chr4:15,309,857–15,738,683, containing 40 predicted genes. DM4.1.3 has a recessive effect on chlorosis, helping maintain leaf greenness during infection, and is in the same interval as the secondary sporulation peak [99,100].

To identify causal genes responsible for these resistance traits, Near-Isogenic Lines (NILs) were developed by introgressing these sub-QTLs into a susceptible line, HS279, which possesses a favorable horticultural trait. Transcriptomic analysis of these NILs indicated that resistance from sub-QTL DM4.1.1 and/or DM4.1.2 likely involves defense signaling pathways, while resistance due to sub-QTL DM4.1.3 appears to be independent of known defense pathways. Fine-mapping and functional analyses identified CsLRK10L2, a Receptor-Like Kinase (RLK), as the most probable causal gene for DM4.1.2. This gene, which carries a loss-of-function mutation in HS279, was significantly upregulated upon P. cubensis inoculation in resistant lines, and its heterologous expression induced necrosis. CsLRK10L2 functions as a DAMP oligogalacturonan receptor involved in pectin breakdown, a key step in plant defense, with a 551 bp insertion likely responsible for its resistance-conferring role. Another key gene, CsAAP2A, encoding an amino acid transporter, was identified as a novel susceptibility gene (S-gene) for DM [101]. Loss-of-function mutations in CsAAP2A, as in resistant cucumber lines, reduce amino acid levels after infection, potentially limiting nutrient availability to the pathogen and enhancing resistance [102]. Another study identified three major QTLs (dm2.1, dm2.2, and dm5.1) associated with DM resistance in cucumber. Fine mapping and expression analysis revealed CsACO, CsCA, and CsSTPK as potential candidate genes [103]. Together, these findings provide a strong molecular foundation for targeted breeding strategies to develop cucumber varieties with durable resistance to DM.

Furthermore, GWAS of 97 cucumber lines identified 18 loci, with 6 consistently associated with stable resistance (dmG1.4, dmG4.1, dmG4.3, dmG5.2, dmG7.1, and dmG7.2). Candidate genes for these loci include Csa1G575030 for dmG1.4 and Csa5G606470 (a WRKY transcription factor) for dmG5.2 [104]. The transcriptome profiling has revealed differentially expressed genes (DEGs) associated with defense mechanisms, including hormone signaling, pathogen recognition, and ROS production. Key genes implicated in defense include Csa5G139760 (acidic chitin endonuclease), Csa6G080320 (LRR and transmembrane domain kinase), Csa5G471600 (retroviral receptor-like protein), and Csa5G544050 and Csa5G564290 (RNA-dependent RNA polymerases) [105]. Another candidate gene, Csa5M622830.1, encodes a GATA transcription factor that may inhibit nutrient supply to pathogens. Additionally, the CsSGR gene, which is a magnesium chelatase gene, has been found to regulate chlorophyll degradation, and its mutation can provide durable DM resistance. KEGG analysis has demonstrated that P. cubensis infection significantly alters several metabolic pathways related to defense mechanisms in cucumber genotypes [106]. Changes in pathogenesis-related proteins such as peroxidase, polyphenol-oxidase (PPO), and superoxide dismutase (SOD) further indicate a complex resistance mechanism [105]. One study identified 48 CsMADS-box genes in cucumber and analyzed their SVs, conserved motifs, and chromosomal distribution. Expression profiling revealed that many genes are tissue-specific, being highly expressed in roots, leaves, flowers, and ovaries, while several genes, including CsMADS07 and CsMADS16, responded to multiple stresses such as high temperature, salinity, DM, and PM [107].

Proteomic analysis has also identified various proteins that are differentially expressed between resistant and susceptible cucumber lines [108]. Most of these proteins are involved in defense, cellular repair, and energy metabolism [108]. For instance, zinc finger-homeodomain (ZHD) proteins, such as CsZHD1-3, CsZHD6, CsZHD8, and CsZHD10, function as plant-specific TFs that respond to DM [109]. RNA interference (RNAi) studies in C. sativus plants have shown that higher salicylic acid (SA) levels confer greater DM resistance than in wild-type plants. This enhanced resistance may be attributed to the interaction of CsIVP, a negative regulator, with CsNIMIN1 within the SA-signaling pathway [110].

CRISPR/Cas9 technology offers an efficient approach to enhancing DM resistance in cucumbers by enabling targeted genetic modifications. This genome-editing tool is crucial for elucidating the precise functions of various genes involved in cucumber growth, development, and stress responses. In 2023, a significant advancement in cucumber-DM research involved the first confirmed use of CRISPR/Cas9 to effectively boost cucumber’s resistance. This study identified a SNP in the STAYGREEN (CsSGR) coding region at the gLTT5.1 locus, which is linked to low-temperature tolerance [111]. CRISPR/Cas9-generated knockout mutants of CsSGR exhibited increased tolerance to various biotic and abiotic stresses, including infection by P. cubensis, low temperatures, salinity, and water deficit [112]. This demonstrates a dual benefit of CsSGR gene modification, enhancing both environmental resilience and disease resistance. A single SNP in its coding region leads to a nonsynonymous amino acid substitution in the CsSGR protein, contributing to disease resistance. The mechanism of CsSGR-mediated resistance likely involves the inhibition of reactive oxygen species (ROS) over-accumulation and the overbuild-up of phytotoxic catabolites in the chlorophyll degradation pathway. This represents a novel function for this highly conserved plant protein [113].

4.2. Fusarium Wilt

Fusarium wilt (FW), caused by the soil-borne vascular pathogen Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. cucumerinum, is a serious fungal disease belonging to the Ascomycetes class [114,115,116]. This pathogen was first reported in Florida in 1955 as a cause of significant losses in commercial field-grown cucumber crops [117], with subsequent reports in greenhouse cucumbers in North Carolina in 1979 [118]. F. oxysporum f. sp. cucumerinum produces macroconidia, microconidia, mycelia, and chlamydospores, which act as propagules for infection and allow the pathogen to survive in the soil for many years, making simple control methods like crop rotation ineffective. The disease thrives in optimal temperatures of 24–27 °C, with no growth above 37 °C, and can cause severe symptoms, including seedling damping-off, plant stunting, yellowing, wilting of older leaves, and distinct brown vascular discoloration, ultimately leading to plant death [119]. The pathogen is primarily host-specific to cucumber, though muskmelon and watermelon exhibit slight sensitivity [120].

Compared to other cucumber diseases like PM and DM, there are limited reports on molecular breeding efforts for FW resistance in cucumber. Early studies suggested that FW resistance is governed by multiple genes, although a single gene for FW resistance has also been reported [121,122,123]. Research has identified several important QTLs on chromosome 2: Foc2.1 was mapped between SSR03084 and SSR17631, with the latter marker showing an 87.88% accuracy for resistance validation among 46 cucumber germplasm [124]. Another major QTL, fw2.1, has been fine-mapped to a physical distance of 0.60 Mb (InDel1248093–InDel1817308) and contains 80 candidate genes [125]. Additionally, an amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP) marker was converted into codominant markers (SCE12M50B and SCE12M50A) linked to the Foc gene, with SCE12M50B also being linked to the Ccu locus controlling scab resistance in cultivar SMR-18 [126,127]. Despite these findings, the molecular mechanisms and functions of these genetic loci remain largely unverified.

Recent advances in proteomic and transcriptomic analyses have begun to shed light on the defense mechanisms against FW in cucumber. Studies comparing resistant and susceptible varieties have identified numerous differentially expressed proteins, with 15 over-accumulated proteins mainly involved in defense and stress responses, oxidation-reduction, metabolism, transport, and jasmonic acid and redox signaling [128]. NLR family and stress-related proteins may be crucial in the defense responses, alongside defense mechanisms against oxidation, detoxification, and carbohydrate metabolism [129]. Transcriptomic analyses within the fw2.1 QTL have identified 12 DEGs, five of which show significantly higher expression in resistant lines, including Csa2G007990 (calmodulin), Csa2G009430 (a transmembrane protein), Csa2G009440 (a serine-rich protein), and two novel genes (Csa2G008780 and Csa2G009330) [125].

Furthermore, defense-related genes, including 14 chitinase genes (e.g., CsChi23, which facilitates rapid immune reactions) and those involved in abscisic acid (ABA) and ethylene signaling, are activated upon Foc inoculation [130,131,132]. Comparative proteomic analysis between resistant (Rijiecheng) and susceptible (Superina) cultivars identified four candidate susceptibility genes, TMEM115, TET8, TPS10, and MGT2 [133]. Additionally, the identification of a chitinase CsChi23 promoter polymorphism demonstrates the application of silicon in enhancing resistance by promoting antioxidant potential and photosynthetic capacity [134].

4.3. Scab

Cucumber scab, caused by Cladosporium cucumerinum, has a significant impact on cucumber production, particularly in cool, humid environments. First reported in the US in 1887, this black spot disease leads to substantial economic losses due to seedling mortality and impaired fruit quality [135]. The resistance to scab primarily traces back to the ‘Maine No. 2’ cultivar, identified in early studies, and forms the genetic basis for most commercial scab-resistant varieties today [136]. To discover new sources of resistance, 188 cucumber accessions were inoculated with the scab. Nine accessions (NSL5731, 255933, 264666, 264667, 306785, 342951, 354952, 458845, and 535881) exhibited complete resistance with no visible symptoms [137].

Resistance to cucumber scab is primarily governed by a single dominant gene, Ccu, which has been mapped on chromosome 2 [138,139]. The Ccu gene, conferring scab resistance, has been mapped using multiple marker systems. The restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) marker CMTC51 is closely linked to resistance at 0.5 cM, flanked by the Fdp2 and Mdh3 allozyme markers [140]. AFLP markers E20M64 and E14M49-F-158-P2 are linked to Ccu at 4.83 cM and 1.9 cM, respectively [141]. Early simple sequence repeat (SSR) studies identified CSWCT02B at 28.7 cM, but later mapping placed Ccu on linkage group 2 (chr 2) with SSR03084 and SSR17631 tightly linked at 0.7 cM and 1.6 cM, achieving 98.3% accuracy [142]. More recent studies have identified even closer markers, Indel01 and Indel02, which delimit the Ccu gene to a 140 kb region containing four nucleotide-binding site (NBS)-type resistance gene analogs (RGAs) [143,144]. Further refinement narrowed the candidate region to 191 kb (bin C2B123), with Csa2G021710, an NBS gene, identified as a strong candidate for Ccu [145]. Interestingly, the Ccu gene is also linked to the Foc gene, which confers resistance to FW, suggesting potential for developing cucumber varieties with multiple disease resistance [146]. While Ccu is the primary contributor to resistance, some research indicates a more complex genetic model, especially in highly resistant materials, involving additional genes with additive-dominance-epistatic effects [147].

4.4. Target Leaf Spot

Target leaf spot (TLS), caused by the necrotrophic phytopathogenic ascomycetous fungus Corynespora cassiicola, is a severe foliar disease affecting cucumber worldwide, leading to significant yield reduction [148]. The disease symptoms typically appear on older leaves as small, round, or angular yellow spots that can expand into larger necrotic areas with light brown centers and dark brown borders [149]. In severe cases, these spots may develop a “shot hole” or shredded appearance as the centers fall out, eventually leading to defoliation. Infected fruit can also become darkened and shriveled [150]. Severe infestation leads to 20–70% yield reduction [150].

Resistance to TLS was initially reported to be controlled by a single dominant gene, Cca, in the cucumber cultivar ‘Royal Sluis 72502’ [151]. Three key genes, cca-1, cca-2, and cca-3, have been molecularly tagged, making them accessible for MAS. In an F2-derived population from the cross between Q5 (resistant) and P57-1 (susceptible), resistance was controlled by a single recessive gene, cca-1, which showed strong linkage to the co-dominant EST-SSR marker CSFR33 [152]. Further, this marker was validated in 30 diverse germplasm lines, with a 93% prediction accuracy [153]. The other recessive gene, cca-2, controls TLS resistance in the wild accession PI 183967, localized between markers SSR10954 and SSR16890 on Chr 6 [149]. While both cca-1 and cca-2 contribute to resistance, their exact genetic relationship and interaction remain largely unexplored. Another significant recessive TLS resistance gene, cca-3, was mapped to a 79-kb region on chr 6. Within this defined region, Csa6M375730, a gene encoding a CC-NB-ARC type resistance homolog, was identified as a strong candidate for cca-3 [154].

Recent GWAS elucidated the genetic basis of TLS resistance. Three novel loci, gTLS5.1, gTLS5.2, and gTLS7.1, identified on chromosomes 5 and 7, are associated with TLS resistance in adult cucumber plants. This study pinpointed five candidate genes, including CsaV3_5G010580 for gTLS5.1 and CsaV3_7G026140, CsaV3_7G026180, CsaV3_7G026200, and CsaV3_7G026220 for gTLS7.1, which are potentially causal for TLS resistance [155]. Beyond specific resistance genes, the molecular mechanisms underlying defense against Corynespora cassiicola infection involve complex pathways. The ERF transcription factor CsERF004 plays a role in resistance via the SA and ethylene pathways [156]. Furthermore, resistance has been linked to genes and microRNAs involved in secondary metabolism, particularly the phenylpropanoid pathway, which contributes to the plant’s defense response [156,157]. An NB-LRR domain gene on chromosome 6 has also been identified as a potential candidate for resistance, emphasizing the involvement of diverse genetic and molecular elements, including cassiicolin, in the host’s response to infection [154].

4.5. Gummy Stem Blight

Gummy Stem Blight (GSB) is a ubiquitous disease caused by three genetically distinct species of the fungus, Stagonosporopsis cucurbitacearum (syn. Didymella bryoniae), S. citrulli, and S. caricae, leading to substantial yield and quality losses in cucumber production, with no commercially resistant cultivars currently available. Fautrey and Roumeguere first reported it in France on cucumber and in Delaware on watermelon in 1891 [72,158]. This disease can lead to substantial yield and quality losses in cucurbit production, with reported reductions ranging from 17% to 43% [159]. GSB manifests under warm (24–25 °C) and humid (85% relative humidity) conditions, with symptoms appearing 3 to 12 days post-spore germination. The pathogen infects all above-ground parts of the plant, including leaves, stems, and fruits. Stem lesions are initially circular and tan to dark brown, progressing to cankers on crowns, main stems, and vines, often accompanied by a characteristic red to amber gummy exudate [160]. Leaf symptoms typically present as pale yellow or brown V-shaped or marginal dead tissue, while fruit lesions are irregular, circular, initially yellow, then turn gray to brown, and become soft, wet, and sunken. The fungus can persist in plant debris for up to two years, with spores dispersed by water, air, and human activity. Internal fruit rot can occur through flower-end infection, while external rot often results from surface wounds [161].

Current management strategies integrate cultural and chemical practices, including the use of certified disease-free seeds, seed treatment, removal of weeds and volunteer plants, reduction in crop residue, and crop rotation with non-host crops [162]. Despite these efforts, commercially resistant cucumber cultivars are not yet available, and the pathogen has developed resistance to several widely used fungicides. However, genetic resistance sources like ‘Homegreen,’ ‘Little John,’ and ‘Transamerica’ have been identified in the US National Cucumber Germplasm Collection [163,164]. Numerous QTLs associated with GSB resistance have been identified across the cucumber genome. In one study, 52 introgression lines (ILs) derived from a C. hystrix × C. sativus cross and eight cucumber cultivars/lines were evaluated for GSB resistance using a whole-plant assay. Three ILs, HH1-8-1-2, HH1-8-5, and HH1-8-1-16, were identified as resistant, and two QTLs were mapped: one on chromosome 4 spanning a 12 cM interval (3.569 Mbp) and another on chromosome 6 spanning an 11 cM interval (1.299 Mbp) [165]. In another study on a 160 F9 RILs population from the cross of PI 183967 (resistant) with C. sativus accession 931 (susceptible), three QTLs were located on chromosome 3 (gsb3.1, gsb3.2, gsb3.3), and one each on chromosome 4 (gsb4.1), chromosome 5 (gsb5.1), and chromosome 6 (gsb6.1). Among these, gsb5.1 on chromosome 5 was identified as a stable major-effect QTL, consistently detected across three seasons and accounting for the highest phenotypic variation at 17.9%. Fine mapping narrowed the gsb3.1 locus to a 38 kb interval, predicting six genes, with four (Csa3G020050, Csa3G020060, Csa3G020090, and Csa3G020590) showing differential expression in resistant versus susceptible lines after fungal inoculation [166].

Zhang et al. [167] indicated that resistance is controlled by three pairs of additive epistatic major genes. They identified five QTLs: gsb-s1.1 on chromosome 1, gsb-s2.1 on chromosome 2, and gsb-s6.1, gsb-s6.2, and gsb-s6.3 on chromosome 6. However, gsb-s6.2 contributed the highest phenotypic variation for GSB resistance in cucumber stems. The study also predicted 117 candidate genes related to GSB resistance between markers SSR04083 and SSR02940. Hu et al. [168] made a notable contribution by identifying a candidate gene on pseudo-chromosome 4 associated with resistance. This research involved the development of an accurate and efficient detection (AED) genetic map. This map is composed of 12,932 recombination bin markers, collectively spanning 1818 cM.

More recently, Han et al. [169] conducted a GWAS and identified 35 single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) associated with GSB resistance. Furthermore, four specific candidate genes were highlighted as potentially involved in this resistance: Csa3G129470, Csa5G606820, Csa5G606850, and Csa6G079730.

4.6. Phytophthora Fruit Rot

Fruit rot is caused by a soilborne oomycete, Phytophthora capsici, that requires warm and wet conditions for optimal growth and disease development. This pathogen primarily infects young fruits, producing water-soaked lesions that develop a white, powdery, or yeast-like growth under moist conditions. This growth consists of lemon-shaped, microscopic sporangia that are readily spread by splashing water, accelerating disease development [170,171]. Fruit may become completely affected and collapse, even postharvest, with younger, smaller cucumbers more susceptible than older, larger ones [171].

Specific fungicides like Presidio®, Orondis®, Zampro®, Revus®, Forum®, Omega®, Ridomil Gold SL, phosphorous acid products, Tanos®, Ranman®, and copper-based options are applied to combat resistance development [172,173]. Screening of the US cucumber collections successfully identified the PIs 109483, 178884, and 214049 as sources of resistance to fruit rot [174]. PS 547 cultivar is resistant to seedling damping-off caused by Phytophthora drechsleri identified in greenhouse-controlled conditions [175]. Another pathogen, Pythium aphanidermatum, can also cause fruit rot and incites similar symptoms characterized by distinct white, enlarged, water-soaked lesions [176].

Currently, no cucumber cultivar with complete resistance is commercially available, though some accessions show reduced sporulation or partial resistance. Two main types of resistance have been identified, i.e., age-related resistance (ARR) and young fruit resistance. ARR, observed in mature fruit (12–16 days post-pollination), involves rapid transcriptional changes and has been linked to a major QTL (qPARR3.1, ~10 Mb) on chromosome 3 [177]. Young fruit (8–12 days post-pollination) resistance is a quantitative trait, and a study was done using an F2 mapping population (n = 362) between ‘Gy14’ (susceptible) and ‘A4-3’ (resistant) revealed significant QTLs linked to young fruit resistance on chromosomes 1, 5, and 6 [178]. Among these, the QTL on chromosome 5 (qPFR5.1) was the most significant contributor to resistance. In the same study, a complementary GWAS was carried out using a core collection (n = 388) to identify 11 significant SNPs associated with resistance, each with varying contribution to the phenotype (0.38–24.49%) [178]. Resistant alleles were predominantly found in accessions from India and South Asia. XP-GWAS was also performed, which is a variation in GWAS that focuses on individuals with extreme phenotypes to increase the power of detecting QTLs. This method helps to confirm the reproducibility of QTLs identified by GWAS. For young fruit resistance, XP-GWAS was performed on bulks of 29 most resistant and 29 most susceptible accessions, identifying 165 significant SNPs across all seven chromosomes, with 39 significant SNPs on chromosomes 1 and 5. The XP-GWAS SNP identified on chromosome 5 overlapped with the QTL found by QTL-seq [178].

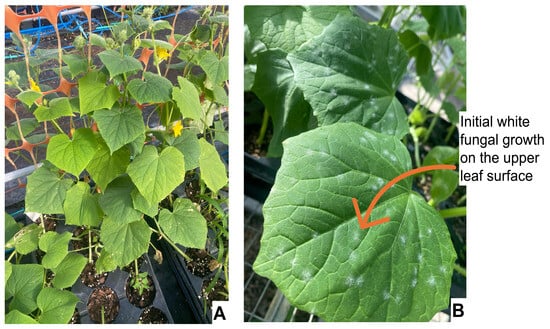

4.7. Powdery Mildew

Powdery mildew (PM) is one of the most destructive foliar diseases of cucumber, primarily caused by two obligate biotrophic fungi, Podosphaera xanthii (syn. Sphaerotheca fuliginea) and Golovinomyces cichoracearum (syn. Erysiphe cichoracearum). PM leads to severe yield losses ranging from 20% to 40% [179]. PM infection is characterized by the formation of white, powdery fungal colonies on both upper and lower leaf surfaces, petioles, and stems, which gradually result in leaf chlorosis, necrosis, and premature senescence, ultimately reducing photosynthetic efficiency and fruit quality (Figure 3) [179,180]. The disease spreads rapidly under warm and humid conditions due to its short incubation period and high sporulation rate.

Figure 3.

Early symptoms of powdery mildew infection on cucumber under greenhouse conditions. (A) Healthy cucumber canopy before infection, showing normal leaf morphology and color. (B) Early infection phase characterized by initial white fungal growth (arrow) on the upper leaf surface, representing primary conidial colonies of P. xanthii. These colonies later expand, coalesce, and lead to chlorosis and tissue senescence in advanced stages (All photos clicked by the author).

The inheritance of PM resistance in cucumber is complex and can be controlled by multiple genes or a single gene, depending on the cultivar and genetic material [181]. Early genetic studies suggested that PM resistance in varieties such as Puerto Rico 37, PI 200815, PI 200818, PI 279465, PI 197087, and Natsu Fushinari was governed by recessive genes [182,183,184,185]. The QTLs has been mapped recurrently on chr 1,2,3,4,5, and 6 with pm5.1/pm5.2 emerging as major, often recessive loci across diverse populations (RILs from Santou × PI197088-1; S06 × S94; K8; CSPMR1 × Santou; WI2757 × True Lemon), with several PM/DM loci co-segregating (dm1.1/pm1.2, dm5.1/pm5.1, etc.) [186,187,188,189,190]. In NCG-122, PM resistance in the stem is controlled by the recessive gene pm-s, mapped to chromosome 5 with the Mlo-related gene Csa5G623470 as a probable candidate [191]. In F2 derived from WI 2757 X True lemon, six QTLs, pm1.1 and pm1.2 (Chr1) conferred leaf resistance; pm3.1 (Chr3) and pm4.1 (Chr4) were susceptibility-associated; and the major loci pm5.1 and pm5.2 (Chr5) were identified [192]. The pm5.1 was a major resistance QTL for PM, and annotation identified the gene as an MLO-like recessive resistance gene [193]. Several PM QTLs co-localize with DM resistance QTLs, including pm2.1–dm2.1, pm5.1–dm5.2, and pm6.1–dm6.1 [194].

Functional characterization of candidate genes has revealed important mechanisms underlying PM resistance in cucumber. Among them, MLO genes play a central role as susceptibility genes [195]. CsMLO1 is one of 13 identified MLO homologs in cucumber (CsaMLO1-13) [196]. The ectopic expression of CsMLO1 in a PM-resistant Atmlo2-Atmlo12 double-mutant results in the recovery of PM susceptibility in Arabidopsis [196]. Similarly, overexpression of CsaMLO1 or CsaMLO8 completely restores PM susceptibility in a tomato mlo mutant [197]. CRISPR/Cas9 was used to generate loss-of-function mutants for CsaMLO1, CsaMLO8, and CsaMLO11 in the PM-susceptible ADR27 cucumber inbred line [196,197,198].

GWAS study identified qgf5.1 and qgf3.1 loci, which are associated with green flesh [104] and another study on 94 accessions detected 18 loci on chr1–6 (three novel: pmG2.1, pmG3.1, pmG4.1) [199]. Previously, it was identified that CsaV3_5G024720 (CsABA2), encoding xanthoxin dehydrogenase, was a candidate gene regulating PM response. Later, they functionally validated CsABA2 and identified a missense SNP associated with PM resistance [200].

Furthermore, transcriptomic analyses have identified DEGs that include genes encoding TFs, peroxidase, NBS proteins, β-glucanase, and chitinase. The SA pathway also appears to play a crucial role in CsPM5.2-mediated PM resistance [108]. Furthermore, miRNAs such as Csa-miR172c and Csa-miR395a were found to regulate defense-associated transcripts during infection, and lncRNAs have been implicated in PM resistance by regulating various target genes and signaling pathways [201].

Several candidate genes and regulatory factors have been identified that play crucial roles in PM resistance in cucumber. Among them, Csa1M064780 and Csa1M064790, encoding cysteine-rich receptor-like protein kinases, are considered strong candidates involved in pathogen recognition and signal transduction [202]. Another key gene, Csa5M622830, encoding a GATA transcription factor, was identified as a single recessive gene potentially responsible for complete PM resistance introgressed from C. hystrix [203]. Several TFs, including GRAS, DoF, eIF2α, polygalacturonase (PG), UDP-glycosyltransferase (UGT), and serine/threonine protein kinases (STPKs), are also differentially expressed following PM inoculation [204].

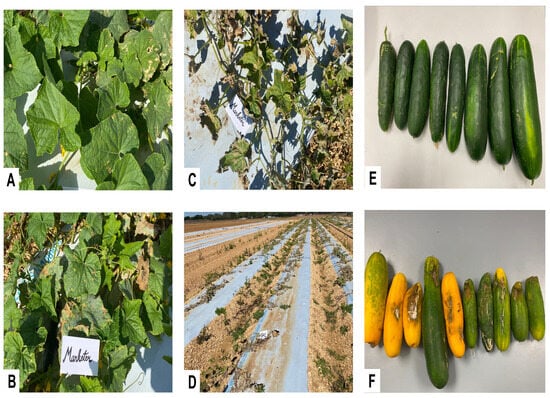

4.8. Anthracnose

Anthracnose is a destructive foliar disease that can lead to significant yield losses (60%), particularly in warm and humid conditions [205]. This disease is caused by the fungus Colletotrichum orbiculare [206,207]. Symptoms typically begin as small, water-soaked or yellowish areas that rapidly enlarge into brown lesions, sometimes with a grayish-white center and dark brown edges [208,209,210]. Fruits can turn black, shrivel, and die, while older fruits develop round, water-soaked spots that become dark green to brown and sunken with age (Figure 4). Under wet conditions, pinkish-colored spore masses may ooze from these sunken spots on fruits [208,211]. Several races of anthracnose have been identified based on their varying virulence on different host cultivars, including Race 0, Race 1, Race 2, Race 2B, and Race 4, among which Race 1 is considered the most virulent [212,213,214,215,216]. Effective management and control of anthracnose rely significantly on understanding the pathogen’s diversity, identifying genetic resistance in host plants, and employing advanced breeding [217]. PI 197087 was one of the first reported sources of anthracnose resistance, and its derivative SC50 (PI 234517) also served as an early identified source of resistance, which is governed by several major genes [218]. The five PI lines (PI 175111, PI 175120, PI 179676, PI 183308, and PI 183445) also showed moderate resistance, and the resistance in PI 175111 was controlled by a single dominant gene that is assigned by the Ar gene [219]. In cucumber line 19B, the resistance is controlled by a single recessive gene, Cla [151].

Figure 4.

Progressive symptoms of anthracnose and its impact on cucumber plants and fruits under field conditions. (A) Healthy cucumber plant showing vigorous vegetative growth before infection. (B) Early disease symptoms are characterized by small, water-soaked, angular necrotic spots bounded by leaf veins. (C) Disease progression with lesion coalescence, leaf necrosis, and canopy decline. (D) Field view illustrating severe anthracnose outbreak with extensive defoliation, vine collapse, and stand loss. (E) Healthy, marketable cucumber fruits exhibiting uniform green color, smooth texture, and proper shape. (F) Diseased and unmarketable fruits displaying yellowing, deformation, cracking, and necrotic fruit rot associated with severe anthracnose infection (All photos clicked by the author).

Many resistant varieties, such as Gy14 and WI2757 in the US, were originally derived from PI 197087 [220]. The African Citron W695 and accession AR79-95 were found to be resistant to anthracnose race 2 [72,221]. Improved cultivars and breeding lines of US origin, including ‘Dual,’ ‘Regal,’ ‘Slice,’ and Gy3, were identified as the most resistant cultigens in field tests, based on multiple environment data [222]. Other cucumber cultivars, ‘Asiastrike,’ ‘Tongilbaedadagi,’ ‘Daeseon,’ ‘Cheongrokmatjjang,’ ‘Nokyacheongcheong,’ and ‘Asianogak’ were moderately resistant to C. orbiculare [223]. A codominant AFLP marker, E24M48-251 bp/245 bp, was identified as closely linked to the anthracnose resistance gene, with a genetic distance of 2.727 cM [224]. This AFLP marker was successfully converted into a sequence characterized amplified region (SCAR) marker (SCEM178/172) for identifying resistance in line ‘66’ [225,226]. Other genotypes found to be superior in their response to disease incidence include LC-1-1, LC-2-2, LC-15-5, CGN-20969, CGN-20953, Poinsette, and K-75.

The Super Zad and Rania hybrid cultivars showed a disease severity of 19.7% and 27.57%, respectively, in greenhouse conditions when treated with SA, which suppresses the mycelial growth [227]. Pan et al. [220] fine-mapped the shared anthracnose-resistance locus (cla) in Gy14 and WI2757 to a 32-kb interval on Chr5, implicating STAYGREEN (CsSGR); a single-nucleotide change in CsSGR’s third exon in Gy14 causes an amino-acid substitution conferring recessive loss-of-susceptibility, with WI2757 carrying the same gene plus a minor-effect QTL. Another study on accession Ban Kyuri (G100) revealed that resistance to Race 0 is conferred by a major locus, An5, and a minor locus, An6.2, corresponding to lysM receptor-like kinase 3 (CsaV3_5G036150) and a wall-associated receptor kinase-like gene (CsaV3_6G048820), respectively. Moreover, resistance to Race 1 was linked to a major QTL, An2, along with three minor loci, An1.1, An1.2, and An6.1, which co-localize with genes encoding PRRs [214]. QTL mapping studies indicated the CsSGR in PI 197087 contributes to resistance to three diseases, including the anthracnose (cca), DM (dm1), and ALS (psl) [220].

5. Major Viral Diseases

Cucumber is susceptible to numerous viral pathogens that pose serious threats to global production and quality. These viruses vary in genome type, transmission mode, and host interaction, including aphid-borne potyviruses (e.g., ZYMV, PRSV, WMV, MWMV), seed- and contact-transmitted tobamoviruses (e.g., CGMMV), and whitefly- or thrips-transmitted viruses (e.g., CVYV, CYSDV, MYSV). Collectively, they cause leaf mosaic, chlorosis, stunting, and malformed fruits, resulting in yield losses ranging from 10% to over 50% depending on the strain, host susceptibility, and the environment. This section provides an overview of major cucumber viruses, including their epidemiology, genetic basis of resistance, and recent advances in molecular breeding and genome editing, which offer promising strategies for developing durable virus-resistant cultivars.

5.1. Cucumber Mosaic Virus (CMV)

CMV is a globally prevalent and highly infectious Cucumovirus (family Bromoviridae) that significantly threatens cucumber production worldwide [228,229,230]. First noted in cucumber more than a century ago, CMV infects >1200 plant species in 100+ families worldwide, spanning vegetable crops, ornamentals, and weeds [231,232]. The virus is efficiently transmitted by over 80 species of aphids, such as Aphis gossypii, in a stylet-borne, nonpersistent manner [229,233]. CMV can damage cucumber crops throughout their entire growth cycle. Infected plants display a range of severe symptoms, including strong leaf mosaic patterns, distortion, puckering, vein banding, stunted growth, reduced flower production, and fruit lesions. It leads to significant yield reductions, which can range from 10% to 20% [234]. The inheritance of CMV resistance in cucumber has shown divergent patterns, including dominant and recessive genetic inheritance, often controlled by a single gene [235,236,237,238].

An early study on ‘Chinese Long’ suggests a single dominant genetic inheritance in pickling cultivars, leading to the creation of the first CMV-resistant cucumber variety, ‘Shamrock’ [239,240,241]. Later, it was reported that it followed a polygenic inheritance pattern for resistance [242]. The cultivars TMG-1 and the Himalayan landraces (Srinagar Local-I and -II and Paprola Local) have also shown single dominant gene control over CMV resistance. Allelism tests among the three Himalayan landraces revealed that the genes controlling CMV resistance in Srinagar Local-I and -II were allelic, but Paprola Local was non-allelic [243,244].

Further QTL studies were done for MAS; using a RIL population, a recessive CMV-resistance QTL, cmv6.1, was mapped to a 624-kb interval on chromosome 6 bounded by SSR9-56 and SSR11-177, with SSR11-1 tightly linked; it explained 31.7% (2016) and 28.2% (2017) of phenotypic variance, and SSR11-1 classified resistance status with 94% accuracy across 78 cucumber accessions [245]. Within the 1624 kb region of the cmv6.1 QTL, nine genes potentially related to disease resistance were identified. One specific gene, Csa6M133680, had four single-base substitutions in its coding sequences (CDSs) and two in its 3′-untranslated region, and its expression levels were 4.4 times greater in the resistant ‘02245’ line compared to the susceptible ‘65G’ line after CMV inoculation [245]. Moreover, a resistance hotspot for CMV has been detected on chromosome 5, co-localizing with the RDR1 gene. This hotspot also confers resistance to other viruses like CVYV, CGMMV, and WMV [246,247,248]. Further, studies have also shown that Bacillus subtilis can induce systemic resistance against CMV in cucumber, leading to a significant reduction in disease severity and viral accumulation [249].

Transcriptomic analysis revealed the upregulation of over 250 defense-related genes, including PR1 and LOX, in cucumber for the stimulated defense response [249]. The eIF4E is widely recognized as a susceptibility factor for viral infections, but natural or engineered variants can provide resistance, particularly against members of the Potyvirus genus [250]. In the case of CMV, the viral 2b protein acts as a suppressor of PTGS, a key host defense mechanism [251]. Interestingly, a mutant strain lacking 2b (Fny-CMVΔ2b) triggers jasmonic acid–dependent defenses that reduce aphid survival and reproduction, with this resistance mediated by the viral 1a replication protein but suppressed when 2b is present [252]. This ability of 2b to counter aphid resistance is conserved across divergent CMV strains, including both Fny-CMV (subgroup IA) and LS-CMV (subgroup II), showing the central role of 2b in viral adaptation [253].

5.2. Cucumber Green Mottle Mosaic Virus (CGMMV)

CGMMV is a significant plant pathogen belonging to the Tobamovirus genus within the Virgaviridae family [254]. It was first identified in 1935, infecting cucumber plants in England, and has since spread globally, primarily through the international seed trade [255,256,257]. CGMMV is known for its particle stability, ease of contact transmission, and seed transmissibility, which contribute to its complex disease cycle and ability to spread over long distances without a vector [258,259]. It is a rod-shaped virus, approximately 300 nm in length and 15–18 nm in diameter, with a positive-sense single-stranded RNA genome of about 6.4 kb, causing significant economic losses in cucurbit crops worldwide, with reported yield losses of 10–15% [260]. Typical symptoms include systemic green mottle mosaic on foliage, and some isolates can induce severe fruit symptoms like pulp deterioration [261].

Despite extensive efforts, CGMMV resistance resources have not been found in cultivated cucumbers, only in melons and wild Cucumis species [262,263]. For instance, C. figarei and C. ficifolius have shown immunity to CGMMV, while ‘Kachri’ and FM 1 exhibited symptomless resistance, tolerating the infection [264]. However, C. sativus var. hardwickii has shown resistance and has been utilized to introduce CGMMV resistance into breeding lines [264]. Another study reported that C. sativus var. sikkimensis showed intermediate symptoms, and two Indian-originated C. sativus accessions (BGV001358 and CGN19818) exhibited mild symptoms against both Asian and European strains of CGMMV [265]. Wild relatives like Cucumis anguria and Cucumis ficifolius showed no symptoms when exposed to both CGMMV strains [265]. Some cucumber varieties, such as ‘Katrina’, have shown low infection levels and high fruit yield, while others like ‘Jawell’, ‘RZ 22-551’, ‘Sunniwell’, ‘Bonbon’, and ‘Dee Lite’ displayed tolerance, maintaining high yields despite high infection levels. Recessive polygenes confer partial resistance in some cucumber varieties [266]. RNA interference (RNAi)-based technologies, including artificial microRNA (amiRNA) and synthetic trans-acting small interfering RNA (syn-tasiRNA), have successfully blocked CGMMV accumulation in cucumber [267].

5.3. Watermelon Mosaic Virus (WMV)

WMV is a potyvirus transmitted by aphids in a non-persistent manner [257,268]. It causes systemic symptoms such as mosaic and dwarfism, as well as fruit malformation [269]. Resistance to WMV in some cucumber lines, such as ‘02245’, is controlled by a single recessive gene designated as wmv 02245, mapped to chromosome 6 [270]. The cucumber variety ‘Surinam’ exhibits resistance to Watermelon mosaic virus 1 (WMV-1) as a monogenic recessive trait, with the gene symbol wmv-1-1 [243]. Research has identified markers linked to WMV-resistant genes in cucumber, which can be useful for marker-assisted breeding. Cultivar ‘Kyoto 3 feet long’, resistance to WMV is attributed to a single dominant gene, denoted as Vw [271]. Inbred line ‘Taichung Mou Gua’ (TMG-1) exhibits a complex inheritance pattern for resistance to WMV involving two distinct mechanisms. The first is conferred by the recessive gene wmv-2 on chromosome 6, which provides whole-plant resistance, including cotyledons. The second mechanism is an epistatic interaction involving wmv-3 and either a dominant allele (Wmv-4) from WI-2757 or a recessive allele (wmv-4) linked 20–30 cM from wmv-3, conferring resistance expressed only in true leaves [272].

5.4. Moroccan Watermelon Mosaic Virus (MWMV) and Zucchini Yellow Fleck Virus (ZYFV)

MWMV and ZYFV are potyviruses that can infect cucurbits, including cucumber [273]. MWMV was first reported in Morocco, causing severe damage characterized by leaf deformation; affected plants showed malformation and blistering of leaves and fruit [274]. Inbred line TMG-1 carries resistance to MWMV governed by a single recessive gene, mwm, as demonstrated in F1, F2, and backcross populations [275]. Further studies on F3 families, derived from F2 individuals selected for Zucchini Yellow Mosaic Virus (ZYMV) resistance, suggest that the mwm gene also controls ZYMV resistance or is tightly linked to the ZYMV resistance gene [275]. Another study found that cucumber plants with knocked-out eIF4E genes exhibited resistance to MWMV [276].

Moreover, ZYFV has been reported in several Mediterranean countries, with an isolate obtained from squirting cucumber (Ecballium elaterium L.) in France and Israel [277,278,279]. In cucumber, ZYFV causes severe mosaic, stunting, and deformation of leaves and fruit. Resistance to ZYFV has been identified in the TMG-1 cultivar from Taiwan, conferred by a single recessive gene, which has been designated zyf [280,281].

5.5. Zucchini Yellow Mosaic Virus (ZYMV)

ZYMV is an aphid-borne potyvirus that severely impacts cucurbit crops, including cucumber. ZYMV is particularly damaging during the summer to early autumn seasons, affecting fruit yield and quality worldwide [282]. Resistance to ZYMV is primarily governed by recessive genes [283]. Several inbred lines have been identified with this resistance, including TMG-1, Dina-1, Formosa (single recessive inheritance), and A192-18 (partial resistance) [284,285]. Amano et al. [246] mapped the zym-1 gene, conferring resistance to ZYMV in the cucumber inbred line ‘A192-18,’ as a single recessive locus located on linkage group VI (LG VI) within an interval containing six candidate genes [246]. Sequence comparison between resistant and susceptible parents identified Vacuolar Protein Sorting 4 (CsVPS4) as the most likely candidate gene for the zym-1 locus. Further analysis revealed that the resistance gene zym-1 in the cultivar TGM-1 (zmvTGM-1), A192-18 (zymA192-18) and Dina-1 (zymvDina) is allelic [246,285]. It is apparent from all the studies that zym-1 carries distinct mutations in different resistant sources. These mutations result in variations in resistance phenotypes and their dominance [286,287].

Allele tests among zymTMG-1, zymDina-1, and zymA192-18 suggest they are strongly linked. Initial genetic maps developed using DNA-based markers like RAPD, AFLP, and RFLP for ZYMV resistance were found to be less polymorphic and not tightly linked to the resistance-governing locus [288,289]. Further, a linkage map developed using 125 SSR markers successfully mapped the recessive locus zymA192-18 to chromosome 6. This locus encompasses six candidate genes from the Japanese inbred line A192-18 [285]. The VPS4-like gene in resistant cucumber lines A192-18, Dina-1, and TMG-1 encodes the same protein sequence despite variations in the introns, indicating genetic uniformity for ZYMV resistance from diverse germplasm sources [246]. A resistance hotspot on chromosome 6 has been identified near the putative VPS4 gene location, which confers resistance to both ZYMV and PRSV [290]. The zym locus, which confers resistance to ZYMV, has garnered significant attention because it has demonstrated resistance to all 173 ZYMV isolates worldwide. Despite this broad resistance, the melon ZYMV resistance line PI 414723 has been observed to lose its resistance to certain ZYMV isolates [289].

5.6. Papaya Ring Spot Virus (PRSV)

PRSV is a significant threat to cucurbit production worldwide, including cucumber [291]. This virus belongs to the genus Potyvirus within the family Potyviridae and is aphid-transmitted, with Myzus persicae being a known vector [292]. It primarily affects papaya and cucurbit hosts, existing as two pathotypes: P and W [293,294,295]. PRSV-W causes severe damage to cucumber production [286,295]. Infected cucumber plants exhibit symptoms such as leaf chlorosis, mosaic, malformation like blisters, narrow leaf blades, and malformed fruits [291].

Resistances to PRSV-W have been identified, primarily in exotic germplasm, necessitating transfer to elite cultivated backgrounds [296]. Molecular markers tightly linked to PRSV-W and ZYMV resistances have been identified to facilitate more efficient selection for virus resistance [296]. In a study, 22 immune lines and 17 highly tolerant lines of USDA Plant Introduction (PI) accession lines of cucumber were identified as resistant to a Nigerian cucumber strain of PRSV-W [297]. Inheritance of PRSV resistance has been reported to be both single recessive and single dominant [287]. TMG-1 carries a dominant gene (Prsv-2) conferring resistance, although it is better described as tolerance since high viral titers can persist in young leaves without symptoms [287,296]. Surinam Local exhibits resistance through a single recessive locus (Prsv-1), while Dina-1 shows dominant to incompletely dominant resistance cosegregating with Prsv-2 [243,296,298]. The Chinese inbred line 02245 harbors a recessive resistance gene (prsv02245) on chromosome 6 and additionally provides resistance to WMV [299]. This gene was flanked by two SSR markers, SSR11-177 and SSR11-1, at genetic distances of 1.1 cM and 2.9 cM from the prsv02245 locus, respectively. The physical distance between these two markers was approximately 600 kb. The accuracy rate of marker-assisted selection for PRSV resistance among 35 cucumber lines using the SSR11-177 marker was over 80% [299]. Recently, CRISPR/Cas9 technology was effectively used to generate cucumber cultivars resistant to WMV, ZYMV, and PRSV by targeting the eIF4E gene [292].

5.7. Cucumber Vein Yellowing Virus (CVYV)

CVYV is a positive-sense single-stranded RNA genome of 9·7kb that causes severe yield losses in cucurbit crops, particularly in Mediterranean countries [257,300,301]. It is a member of the genus Ipomovirus within the family Potyviridae [302]. CVYV is primarily transmitted by the whitefly Bemisia tabaci in a semi-persistent mode, but it can also be transmitted mechanically in experimental conditions [302]. Several cucumber accessions have demonstrated partial resistance to CVYV, including CE0749, C.sat-10, C.sat-11, C.sat-14, C.sat-40, Kyoto-3-feet, and TMG-1 [303]. CVYV resistance was first identified in the Japanese cucumber variety Kyoto-3-feet [304]. Subsequently, four accessions (C.sat-10, C.sat-11, C.sat-14, and C.sat-40) were identified from a screening of 46 Spanish cucumber landraces that displayed fewer symptoms and lower levels of CVYV, exhibiting partial resistance with a genetic inheritance pattern [304]. Further investigation revealed that the CVYV resistance in C.sat-10 follows a single dominant genetic inheritance pattern [305]. Most Spanish cucumber accessions are highly susceptible [305]. Additionally, a Dutch-type cucumber accession, CE0749, was found to carry a monogenic, incompletely dominant resistance locus (CsCvy-1) on chromosome 5, spanning 625 kb with 24 annotated genes, which explains over 80% of CVYV resistance. Although several partially resistant accessions were reported, they proved insufficient for durable resistance [306].

5.8. Melon Yellow Spot Virus (MYSV)

MYSV is caused by a distinct virus species belonging to the genus Tospovirus within the family Bunyaviridae or Tospoviridae and is transmitted by thrips [307,308]. First identified in 1992, MYSV has caused severe damage to melon and cucumber production in Japan [309,310]. Symptoms in infected cucumber plants include necrotic spots, mosaic patterns, and yellow spots that can fuse to form large necrotic areas [309]. For resistance breeding, Sugiyama et al. (2009) evaluated 398 cucumber accessions from 26 geographical origins for MYSV resistance through mechanical inoculation [310]. They identified 13 accessions that displayed mild disease symptoms, and ultimately, 10 of these, including 27028923, 27028930, 27028932, 27028933, C4-6-5, C6-14, Cucumber-125, Yamakyuri-1, Yamakyuri-2, and Wa-19, showed no disease symptoms [311]. Double-antibody sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (DAS-ELISA) revealed that accession 27028930 was resistant to the melon isolate MYSV-S, while Yamakyuri-1 showed moderate resistance to the cucumber isolate FuCu05P [311]. QTL analysis was done, using accession 27028930, which identified four QTLs linked to MYSV-FuCu05P resistance located on chromosomes 1, 3, 4, and 7 [311]. Two major QTLs, designated Swf-1 on chromosome 1 and Swf-2 on chromosome 3, were contributed by the resistant accession 27028930. One minor QTL, Swf-4 on chromosome 7, was also derived from 27028930. However, another minor QTL, Swf-3 on chromosome 4, originated from the susceptible cultivar ‘Tokiwa’ [311].

5.9. Cucurbit Yellow Stunting Disorder Virus (CYSDV)

Cucurbit yellow stunting disorder virus (CYSDV) belongs to the genus Crinivirus within the family Closteroviridae [312,313]. CYSDV is primarily transmitted by the tobacco whitefly (Bemisia tabaci), specifically biotypes B and Q, in a semi-persistent manner [314]. CYSDV was first identified in the United Arab Emirates during 1982 and has since spread to numerous countries, including Syria, Turkey, Jordan, Spain, Portugal, Morocco, and North American countries [315,316]. The initial symptoms of CYSDV infection include interveinal chlorosis (yellowing) and green spots on the oldest leaves. As the disease progresses, these chlorotic spots enlarge, leading to the yellowing of entire leaves, with the veins typically remaining green [317]. Severely affected leaves can also become brittle. This disease can result in significant yield and quality losses in affected crops. The host range of CYSDV was initially thought to be restricted to members of the family Cucurbitaceae, including melon, cucumber, marrow, and squash [318]. Developing resistant cultivars is considered an economically and environmentally sound approach for managing CYSDV. To date, no cucumber accessions resistant to CYSDV have been reported in the scientific literature [319].

Several other PI lines in the USDA GRIN collection have shown partial resistance against CYSDV, including PI 177364, PI 211589, PI 293432, PI 279807, PI 605923, Ames 13334, and NLS 5746. These lines exhibited delayed infection and less severe symptoms. Among them, PI 211589 (from Afghanistan), PI 605923 (from India), and Ames 13334 (from Spain) displayed relatively higher tolerance to CYSDV. This suggests that potential sources of CYSDV resistance may originate from Asia and Spain [319]. Further study evaluating 300 accessions under natural infection found 24 accessions with partial symptoms; however, under controlled artificial inoculation, only A1 and A2 exhibited resistance, characterized by a delayed onset of CYSDV infection and reduced symptom severity compared to susceptible controls at 8 and 12 weeks post-inoculation [320]. Moreover, resistance to CYSDV was identified in accession PI 250147, and three QTLs were identified, with one major QTL (QTL1) on chromosome 4, which was found to explain 42% of the resistance. Interestingly, this QTL is located between two loci conferring resistance to powdery mildew [321]. Later, locus cysdv5.1 was identified to control CYSDV resistance in PI 250147 and followed a single genetic inheritance pattern [322].

6. Bacterial Disease Resistance