Abstract

Triploid breeding is a promising approach for developing seedless varieties, but the long juvenile phase of perennial fruit trees necessitates efficient early selection. In loquat (Eriobotrya japonica), a fruit crop with high demand for seedlessness, the relative contributions of hybridity, ploidy level, and parent-of-origin effects (POEs) to triploid seedling vigor remain elusive. To dissect these factors, we established a comprehensive experimental system comprising reciprocal diploid (2x), triploid (3x), and tetraploid (4x) hybrids from two genetically distinct cultivars. The ploidy, hybridity and genetic architecture of hybrid and parental groups were verified using flow cytometry, chromosome counting, newly developed InDel markers and genome-wide SNP analysis. Phenotypic evaluation of eight vigor-related traits revealed that plant height and soluble starch content were the most robust indicators of triploid heterosis in loquat. Notably, paternal-excess triploids [3x(p)] consistently outperformed all other groups. Quantitative analysis revealed POE as the main positive driver of triploid heterosis (+10.37% for plant height), far exceeding the negative impacts of hybridity (−12.75%) and ploidy level (−20.87%). These findings demonstrate that POE predominantly drives seedling vigor heterosis in triploid loquat. We propose a practical breeding strategy that combines prioritizing paternal-excess crosses with novel InDel markers for rapid verification of superior seedless progeny.

1. Introduction

Loquat (Eriobotrya japonica (Thunb.) Lindl.) is a subtropical evergreen fruit crop valued for its fresh fruit and medicinal properties [1]. However, most of its cultivated varieties are diploid (2n = 2x = 34) producing fruits that typically contain three to five seeds, which significantly hampers its marketability and consumer appeal (Figure S1). Triploid, characterized by 3 chromosome sets, offers a promising strategy for developing seedless or reduced-seed fruits, as successfully applied in fruit crops like banana [2], watermelon [3], citrus [4] and grape [5]. Beyond seedlessness, triploids often exhibit enhanced vigor compared to their diploid counterparts, manifested as increased biomass accumulation, improved stress tolerance, and elevated secondary metabolite content—a phenomenon known as polyploid heterosis [6].

To harness these benefits, various methods have been employed for triploid breeding in fruit trees, including interploidy hybridization [7], protoplast fusion [8] and natural triploid selection [9]. Among these, interploidy crosses between diploid (2x) and tetraploid (4x) have proven to be the most effective method, yielding the highest frequency of triploid offspring [10]. However, triploid heterosis in inherently highly heterozygous fruit trees is shaped by the intricate interplay among hybridity (heterozygosity from different parents), ploidy level (the effect of having three chromosome sets versus two or four), and parent-of-origin effects (POE), which arise from imbalanced genomic dosage contributed by maternal and paternal parents (a 2m:1p ratio in 4x × 2x crosses vs. a 1m:2p ratio in 2x × 4x crosses) [11,12]. Therefore, it is of paramount importance to clearly understand the quantitative contributions of these factors, as this is essential for establishing an efficient breeding strategy aimed at maximizing triploid heterosis.

Moreover, another major bottleneck for efficient breeding is the long juvenile period of the perennial fruit tree, which can span many years before fruit-related traits can be evaluated. This makes conventional selection inefficient and costly [13]. Consequently, it is of paramount importance to establish reliable early-stage selection criteria. Seedling vigor traits, such as plant height and biomass accumulation, have been shown to be valuable indicators for the long-term growth potential, environmental adaptability, and eventual productivity of adult trees [14,15]. Therefore, understanding the genetic determinants of triploid heterosis during seedling stages provides a strong basis for accelerating the genetic improvement cycle, making it possible to screen out promising genotypes at an early stage. While studies in model plants like Arabidopsis [11] and maize [16] have highlighted the importance of POE and hybridity to triploid heterosis, the quantitative contribution of hybridity, ploidy level, and POE has not yet been systematically applied to triploid heterosis at early stage in fruit trees like loquat.

Therefore, this study aimed to (i) establish a comprehensive experimental system comprising reciprocal 2x, 3x, and 4x hybrids with a clear genetic background; (ii) validate the ploidy, hybridity and genetic architecture of hybrid and parental groups using cytological methods, and novel InDel markers and genome-wide SNP analysis based on whole-genome resequencing; (iii) systematically evaluate seedling vigor traits to identify key heterotic traits as early-stage indicators of triploid heterosis; and (iv) quantitatively dissect the relative contributions of hybridity, ploidy, and POE to the key heterotic traits of triploid loquat. This study provides a foundational understanding of the genetic basis for seedling vigor heterosis in triploid loquat and offers an actionable strategy for the genetic improvement of seedless loquat varieties.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials

The experimental system was established using 4 loquat lines as parents (Table 1): L2 (2n = 2x = 34) and L4 (2n = 4x = 68) derived from a red-fleshed cultivar ‘Longquan No. 1’; R2 (2n = 2x = 34) and R4 (2n = 4x = 68) derived from white-fleshed cultivar ‘Ruantiaobaisha’. The hybrid groups include (i) reciprocal 2x hybrids (R2 × L2 and L2 × R2) (by convention the maternal parent is listed prior to the paternal parent in a cross); (ii) reciprocal 3x hybrids consisted of maternal-excess triploids [3x(m): R4 × R2, R4 × L2, L4 × R2, and L4 × L2] and paternal-excess triploids [3x(p): L2 × L4, R2 × R4, L2 × R4, and R2 × L4]; and (iii) reciprocal 4x hybrids (R4 × L4 and L4 × R4). In addition to the F1 hybrids, progeny from the self-pollination of each parental line (L2, L4, R2, and R4) were also generated. These selfed progeny were included in all experiments to serve as parental controls for phenotypic and genetic analyses, following the strategy described in [17]. Crosses were carried out by removing immature anthers from unopened flower buds of the maternal parent and pollinating the stigma with pollen from the paternal parent. Seeds collected from these groups were germinated and initially grown on soil under a 16/8 h (light/dark) cycle. After 6 months, seedlings were transplanted to the Polyploid Loquat Germplasm Nursery of Southwest University (Beibei District, Chongqing, China).

Table 1.

Summary of crossing design.

2.2. Flow Cytometry and Chromosome Spreads

Ploidy levels of all F1 progeny were routinely determined by flow cytometry as previously described [18]. Approximately 0.5 cm2 of leaves from 3-month-old seedlings were collected and finely minced in 1 mL of cell extraction buffer. The homogenate was filtered through a 400-mesh sieve into a 2 mL centrifuge tube. The filtrate was then stained with 200 μL of DAPI staining buffer and incubated in the dark for 5 min. Fluorescence intensity ranges for known diploid were used as control. After establishing fluorescence baselines for known ploidies, samples were analyzed on a CyFlow® Ploidy Analyzer (Sysmex, Germany) by comparing their peak distributions to a diploid control.

To corroborate the flow cytometry results, chromosomes at mitotic metaphase were prepared according to Wang et al. [19]. Samples were prepared from 1.0–1.5 cm root tips and then pre-treated with 2 mmol·L−1 8-hydroxyquinoline in the dark for 3 h, followed by fixation in Carnoy’s fluid (3:1 methyl alcohol:acetic acid). Enzymatic hydrolysis was carried out at 37 °C for 3 h using a solution of 3% cellulose and 0.3% pectinase. Slides with chromosome spreads were obtained and stained with 5% Giemsa solution. Chromosomes were observed and photographed using a fluorescence microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) to confirm the ploidy levels.

2.3. Whole-Genome Resequencing and Variant Calling

For whole-genome resequencing, a total of 2–3 young, fully expanded leaves were collected from the apical shoots of 6-month-old hybrid progeny and their corresponding parental controls. For each hybrid and parental line, a total of 12 individual plants were selected. These 12 individuals were then randomly assigned to three independent biological replicates, with each replicate consisting of an equal amount of pooled leaf tissue from 4 different plants. High-quality genomic DNA was extracted from these pooled samples using the cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) method [20]. Paired-end sequencing libraries (about 300 bp insert size) were constructed and sequenced on an Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform to an average depth of 10× per sample. High-quality paired-end reads were aligned to the Eriobotrya japonica ‘Jiefangzhong’ reference genome (accession: CNP0001531, released by South China Agricultural University; https://db.cngb.org/search/project/CNP0001531, accessed on 31 December 2025) using the BWA-MEM algorithm (v0.7.12-r1039). Post-alignment processing, including sorting and duplicate marking, was performed using Picard tools (v1.107).

Variant calling was performed across all samples using the GATK (v3.8) HaplotypeCaller pipeline. Raw variants were subjected to stringent filtering criteria (Fisher Strand Bias (FS) < 200, read depth (DP) > 4, quality by depth (QD) ≥ 2.0, and ReadPosRankSum ≥ −20.0) to obtain a high-confidence set of SNPs and InDels. The functional impact of these variants was annotated using ANNOVAR (v20200607). Genetic distance (GD) was calculated using the p-distance method. A phylogenetic tree was constructed for cluster analysis based on the total SNP dataset (GDtotal) using MEGA X software (version 10.2.6). The tree was inferred using the Neighbor-Joining (NJ) method, with evolutionary distances computed using the p-distance model. The heatmap in Figure A1 was generated using the pheatmap package in R (v1.0.12). Selected InDels were used to design markers for hybrid verification via PCR-based fragment analysis (primer sequences in Table S1). PCR amplification for the selected InDel markers was performed in a 20 µL reaction volume containing 0.2 µL of rTaq polymerase (5 U/µL), 2 µL of 10× PCR buffer (containing 15 mM Mg2+), 2 µL of dNTP mix (2.5 mM each dNT), 1.6 µL of each forward and reverse primer (10 µM), 2 µL of genomic DNA (approx. 50 ng), and 10.6 µL of nuclease-free water. The PCR cycling conditions were as follows: an initial denaturation at 94 °C for 4 min; followed by 33 cycles of denaturation at 94 °C for 30 s, annealing at 50–60 °C for 50 s, and extension at 72 °C for 60 s; and a final extension at 72 °C for 10 min. The resulting PCR products were separated and visualized by electrophoresis on a 2.5% high-resolution agarose gel stained with an appropriate DNA dye. A 100 bp DNA ladder was used as a size standard. The DNA fragments were visualized and documented under a gel imaging system. Raw resequencing data have been deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) under accession number PRJNA1267686.

2.4. Phenotyping and Statistical Analysis

To accurately characterize the growth status of seedlings, all hybrid groups and their parental controls were used for phenotypic measurements under strictly maintained uniform growth conditions throughout the experiment. Subsequently, a total of 8 physiological and biochemical indicators related to seedling vigor were measured at 12 and 24 months after planting (MAP). For each group, 12 individual plants were randomly selected for all phenotypic measurements. Plant height was measured using a tape measure; leaf area was determined with a Li-300A portable leaf area meter (LI-3000C; LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE, USA); leaf number was manually counted; stomatal density was assessed on 0.5 cm2 leaf segments near the midrib using scanning electron microscopy (SEM), following standard fixation, dehydration, and gold sputter-coating procedures as described by [21] and calculated as the number of stomata per square centimeter; leaf starch content was assayed using the Starch Assay Kit SA-20 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions; chlorophyll a and b contents were determined spectrophotometrically, approximately 0.2 g of minced leaf tissue was extracted in 50 mL of a 1:1 (volume ratio) mixture of 99% acetone and 95% ethanol in the dark until completely bleached, absorbance values were recorded at 663 nm and 645 nm, and chlorophyll concentrations were calculated using the following formulas:

OD663 and OD645 are absorbances at 663 and 645 nm, respectively. Based on the phenotypic data, the extent of heterosis was quantified by calculating mid-parent heterosis (MPH) and better-parent heterosis (BPH) for all groups. The MPH and BPH were calculated by the formulas as follows: MPH = [F1 − (P1 + P2)/2]/[(P1 + P2)/2] × 100% and BPH = (F1 − HP)/HP × 100%, where F1 is the value of F1 hybrids, P1 and P2 are the phenotypic value of parents, HP is the phenotypic value of higher value parents. Factorial contribution analysis of genetic effects on heterotic vigor traits of triploid were conducted based on the following formulas:

All measured data were processed and graphed using Microsoft Excel 2003. Data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA for multiple comparisons and independent sample t-test for two groups comparisons; different lowercase letters denote significant differences among groups (p < 0.05).

3. Results

3.1. Validation of Ploidy and Hybridity in F1 Hybrids

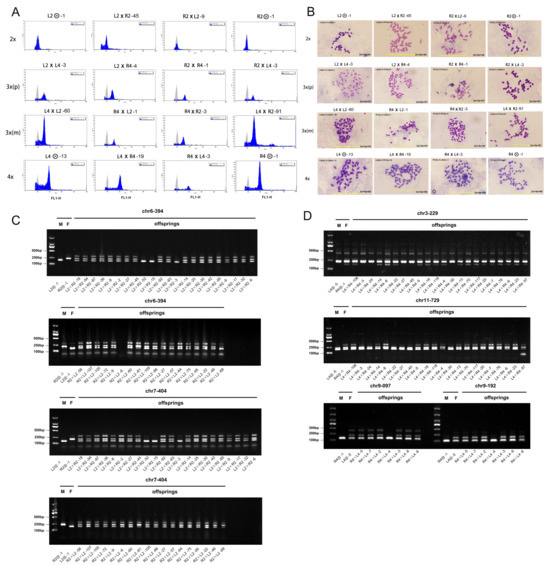

Three complementary methods were employed to confirm all F1 hybrid groups used in this study were true hybrids with the expected ploidy levels (Figure 1). Flow cytometry was initially used for ploidy assessment by measuring the relative DNA content [22]. The 2x, 3x, and 4x individuals showed primary fluorescence peaks at approximately 200, 300 and 400 relative fluorescence units (RFU), respectively (Figure 2A). To validate these results, chromosome counts were performed on mitotic metaphase spreads from root tip (Figure 2B). The counts confirmed the expected chromosome numbers, with 34 for 2x, 51 for 3x, and 68 for 4x hybrids and selfed progeny, consistent with flow cytometry results. For homoploid crosses, which involve parents at the same ploidy level (i.e., 2x × 2x or 4x × 4x), neither flow cytometry nor chromosome counts could distinguish true hybrids from selfed progeny. Therefore, insertion-deletion (InDel) markers were developed using whole-genome resequencing data to identify polymorphic sites. InDel loci that were homozygous and polymorphic between the female and male parents (with a fragment size difference >50 bp) were selected, ensuring heterozygosity in true hybrids [23]. Based on this strategy, a total of 41 InDel primer pairs were validated on parental genomic DNA, yielding 15 polymorphic pairs for 2x parents (L2 and R2) and 10 for 4x parents (L4 and R4) (Table S1). Due to the co-dominant nature of InDel markers, true hybrids were expected to amplify bands from parents or exhibit a paternal-specific band [18]. Progeny were confirmed as true hybrids only if results from at least two InDel markers consistently showed hybridity patterns. We found that an average of 3 to 4 polymorphic markers were successfully amplified to confirm the hybrid status for each cross combination. Representative examples of these results are shown in Figure 2C,D. For reciprocal crosses at 2x level, markers chr7-404 and chr6-394 effectively amplified distinguished parental bands (Figure 2C). For crosses at 4x level, markers chr3-229 and chr11-729 were selected for L4 × R4, while chr9-097 and chr9-192 were used for R4 × L4 (Figure 2D). Among the screened progeny, the percentages of true hybrids were 86.36% for L2 × R2, 94.44% for R2 × L2, 72.73% for L4 × R4 and 85.71% for R4 × L4, respectively (Table S2). Non-hybrid individuals were excluded from further analyses.

Figure 1.

Field growth of all hybrid and parental groups at 24 months after planting (MAP).

Figure 2.

Validation of ploidy level and hybridity in F1 hybrid and parental groups of loquats. (A), Representative flow cytometry analysis of relative DNA content in leaf nuclei; The distinct fluorescence intensity peaks correspond to diploid (2x, about 200 RFU), triploid (3x, about 300 RFU), and tetraploid (4x, about 400 RFU) individuals; RFU, Relative Fluorescence Units (X-axis = fluorescence intensity, Y-axis = nuclei count). (B), Chromosome counting from root tip metaphase spreads; Chromosome numbers are indicated for diploid (2n = 2x = 34), triploid (2n = 3x = 51), and tetraploid (2n = 4x = 68) individuals; scale bar = 20 μm. (C), Amplification of representative InDel primers (chr6-394, chr7-404) in the diploid F1 hybrids and their parents. (D), Amplification of representative InDel primers (chr3-229, chr11-729 for L4 × R4 and chr9-097, chr9-192 for R4 × L4) in the tetraploid F1 hybrids and their parents; F = female parent, M = male parent. In (C,D), these markers effectively distinguished true-hybrids from false-hybrids based on their banding patterns. True-hybrids were confirmed by the co-inheritance of fragments from both the maternal (F) and paternal (M) parents, resulting in a heterozygous profile (e.g., L2 × R2-46 in (C)). Conversely, individuals exhibiting only a single parental band were identified as false-hybrids arising from self-pollination and were excluded from all subsequent analyses (e.g., L2 × R2-45 in (C), which matches the maternal L2 profile).

3.2. SNP-Based Genetic Architecture of Hybrids and Parental Groups

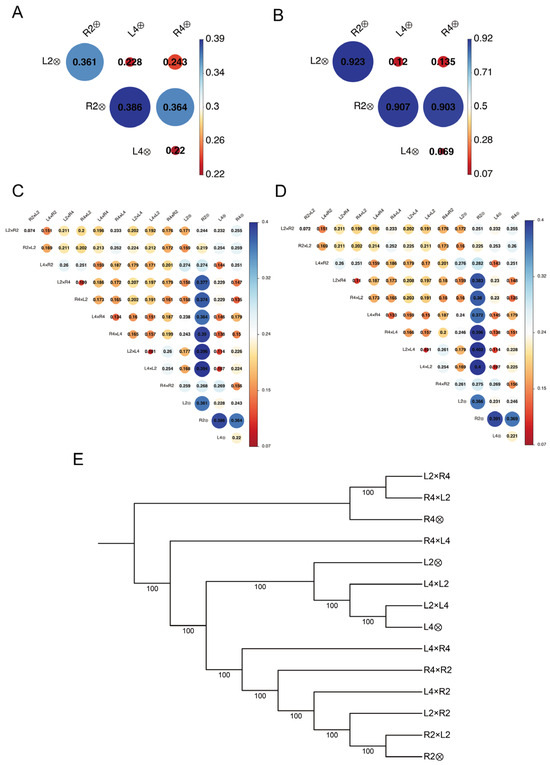

To elucidate the genetic architecture of the loquat hybrid and parental groups, a high-quality set of 7,538,804 SNP markers was obtained from whole-genome resequencing data after quality control and filtering, as detailed in Section 2.3, with an average mapping rate of 98% and high base quality scores (Q20 > 97.61%, Q30 > 93.17%) (Table S3). Genetic distances among parental groups highlighted their divergence (Figure 3A,B). The total genetic distance (GDtotal), calculated from all SNPs, revealed that L4 and R4 were the most closely related parents (GDtotal = 0.220), whereas L4 and R2 were the most divergent (GDtotal = 0.386) (Figure 3A). To specifically capture fixed genetic variation, we calculated the homozygous genetic distance (GDhomo) using 408,157 fixed SNP loci, identifying L2 and R2 as the most distant cross (GDhomo = 0.923) and L4 and R4 as the closest (GDhomo = 0.069) (Figure 3B). This broad GDhomo range (0.069 to 0.923) underscores the significant homozygous differentiation among the parental groups. Genetic distance matrices for the entire group, including all F1 hybrids and corresponding parental control, showed GDtotal values from 0.074 to 0.396 (Figure 3C). To mitigate potential bias from missing data, a second matrix, GDfilt, was calculated after the stringent exclusion of all SNP loci with missing calls, yielding values from 0.072 to 0.402 (Figure 3D).

Figure 3.

SNP-based genetic structure of F1 hybrid and parental groups. (A), Pairwise total genetic distance (GDtotal) among parental group calculated from 7,538,804 SNPs. (B), Pairwise homozygous genetic distance (GDhomo) among parental group calculated from 408,157 homozygous differential SNPs. In (A,B), circle size and color intensity are proportional to the genetic distance. (C), Heatmap of the GDtotal matrix for F1 hybrid and parental groups. (D), Heatmap of the filtered genetic distance (GDfilt) matrix, calculated after exclusion of all loci with missing calls. (E), Dendrogram from cluster analysis of F1 hybrid and parental groups based on GDtotal.

Phylogenetic analysis based on GDtotal delineated the genetic relationships among all groups (Figure 3E). Diploid hybrids (L2 × R2 and R2 × L2) clustered closely with R2, while 4x hybrids (L4 × R4 and R4 × L4) grouped with L4. Triploid progeny from R4 × L2 and L2 × R4 clustered predominantly with the tetraploid parent R4, suggesting a strong influence of parental genome dosage on genetic similarity. Notably, all samples derived from ‘Longquan No. 1’ (L2, L4, L4 × L2, and L2 × L4) formed a cohesive monophyletic clade, whereas ‘Ruantiaobaisha’-derived parents (R2 and R4) diverged into separate branches, indicating clear genetic differentiation between these parental materials and their progeny.

3.3. Phenotypic and Factorial Contribution Analysis of Seedling Vigor Heterosis in Triploid Loquat

To quantify heterosis in triploid hybrids, we evaluated reciprocal 2x, 3x(m), 3x(p) and 4x hybrids, along with their corresponding parental controls under uniform growth conditions (Figure 1). Eight seedling vigor traits were measured at 12 and 24 months after planting (MAP), all of which showed approximately normal distributions at 24 MAP (Figure S2), with data processed and analyzed as described in Section 2.4 (Figure 4; Tables S4 and S5). The 24 MAP data were prioritized for stable, long-term genetic effects, while 12 MAP reflected early vigor.

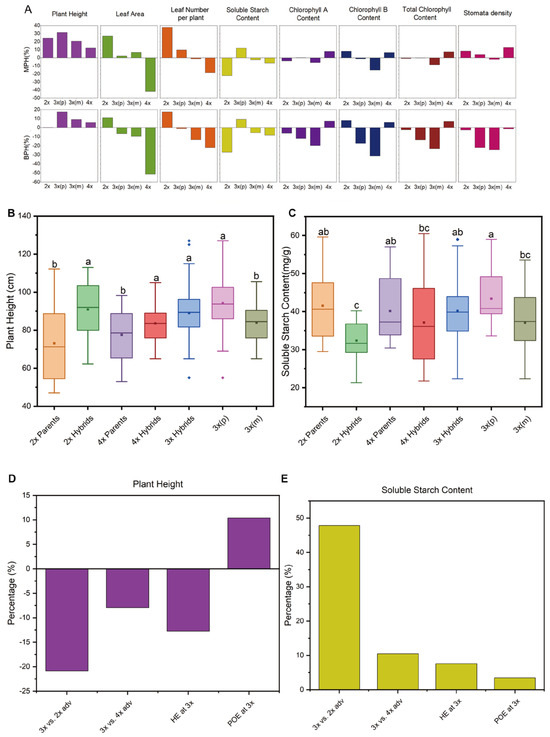

Figure 4.

Heterosis and factorial contribution analysis of seedling vigor traits in different loquat groups. (A), Mid-parent heterosis (MPH) and best-parent heterosis (BPH) values for eight seedling traits at 24 months after planting (MAP); Each bar represents the mean heterosis value for F1 hybrids within the diploid (2x), paternal-excess triploid [3x(p)], maternal-excess triploid [3x(m)], and tetraploid (4x) group. (B,C), Box plot comparisons of (B) plant height and (C) soluble starch content among hybrid and parental groups at 24 MAP; groups are shown parents and F1 hybrids at the 2x and 4x levels, and 3x hybrids categorized by 3x(p) and 3x(m); In each box, the central line indicates the median and the square indicates the mean; diamond symbols represent outlier observations lying outside the main distribution; different lowercase letters denote significant differences among groups (one-way ANOVA with Duncan’s test, p < 0.05). (D,E), Factorial contribution analysis of different genetic effects on plant height (D) and soluble starch content (E); bars represent the relative contribution (%) of the ploidy effect [advantage of 3x hybrids versus 2x parents (3x vs. 2x adv.) and advantage of 3x hybrids versus 2x parents (3x vs. 4x adv.)], the hybridity effect at the 3x level (HE at 3x), and parent-of-origin effect at the 3x level (POE at 3x).

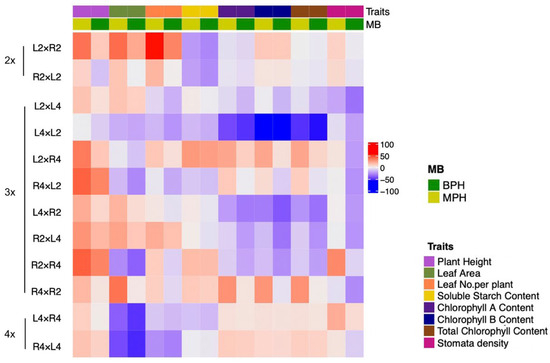

At 24 MAP, analyses of mid-parent heterosis (MPH) and best-parent heterosis (BPH) uncovered trait-specific variations across ploidy levels (Figure 4A). Plant height consistently showed significant positive MPH and BPH in all groups, with 3x(p) hybrids exhibiting the strongest heterotic effect (MPH = +31.49%; BPH = +17.63%). For leaf area, MPH was positive in 2x and 3x groups, peaking at +27.25% in 2x, but was negative for the 4x group. For leaf number per plant, MPH was positive in the 2x and 3x(p) groups, while BPH was positive only in the 2x group. Soluble starch content displayed notable positive heterosis in 3x(p) hybrids (MPH = +12.07%; BPH = +9.42%), underscoring its role in metabolic advantages. In contrast, stomata density presented positive MPH in most groups except for 3x(m), while BPH was negative across all hybrid groups. Overall, these observations positioned plant height and soluble starch content emerged as the most robust indicators of triploid heterosis, especially in 3x(p), and emphasized POE as revealed by the trends of reciprocal crosses in the heatmap analysis (Figure A1).

Given the consistent and significant heterosis observed in 3x hybrids for plant height and soluble starch content, which are well-established as indicators of seedling growth and metabolic efficiency, these traits were selected for detailed quantitative evaluation of the relative contributions of various effects, including hybridity, ploidy level, and POE. Box plot analyses revealed variations in trait performance across ploidy levels and genetic groups (Figure 4B,C). Notably, 3x(p) hybrids displayed the highest median values for both plant height (approximately 95 cm) and soluble starch content (approximately 45 mg·g−1), significantly surpassing other groups (p < 0.05). This standout performance of 3x(p), in sharp contrast to the intermediate or inferior performance of their reciprocal 3x(m) counterparts, suggests that POE, rather than triploid itself, is a primary determinant of heterosis in these traits [24].

The relative magnitude of factorial contribution was quantified through percentage changes in 4 key comparisons (Figure 4D,E). For plant height, POE exerted the strongest positive influence (+10.37%), markedly higher than the hybridity effect at the 3x level (−12.75%) (Figure 4D). In contrast, the advantage of 3x hybrids relative to 2x parents (3x vs. 2x adv.) yielded a negative impact (−20.87%), as did the advantage over 4x parents (3x vs. 4x adv., −7.95%). This finding underscores POE at 3x level as a pivotal enhancer of plant height, capable of overcoming the inherent negative effects associated with increased ploidy and hybridity. Interestingly, soluble starch content presented a divergent profile (Figure 4E). The 3x advantage relative to 2x parents was positive (+47.84%), with a milder positive effect against 4x parents (+10.48%). Meanwhile, the hybridity effect (HE at 3x) contributed positively (+7.58%), though POE at 3x level exhibited a lower positive effect (+3.47%). Collectively, these findings reveal trait-specific variations in triploid loquat, highlighting plant height and soluble starch accumulation as key heterotic traits for seedling vigor. Notably, POE dominates plant height enhancement and provides consistent positive contributions to soluble starch accumulation, underscoring its pivotal role in triploid heterosis. This result indicates that parental genome dosage effects, potentially involving dosage-dependent gene regulation and POE-specific epigenetic modifications, interactively shape triploid heterosis [17,24].

4. Discussion

Triploid heterosis is a complex phenomenon influenced by the interplay of hybridity, ploidy level, and parental genome dosage. Debates on its primary driver are often framed and advanced through the gene balance hypothesis [25] and empirical insights from gene expression analysis in polyploids [26]. Existing research dissects these contributions using model species, such as A. thaliana and maize, that allow for the construction of isogenic or allopolyploid systems to simplify genetic backgrounds [27,28]. However, for highly heterozygous perennial tree species like loquat, their inherent genetic complexity and long generation cycles make disentangling these factors challenging, leaving a gap in understanding triploid heterosis mechanisms in economically important fruit crops.

To address this, we strategically utilized diploid-tetraploid crosses derived from intra-cultivar (L2 × L4, R2 × R4, L4 × L2, R4 × R2) and inter-cultivar crosses (L2 × R4, R2 × L4, R4 × L2, L4 × R2) to generate a comprehensive set of triploid hybrid groups. Genome-wide SNP analysis revealed that the genetic distances between groups were not solely determined by whether parents originated from the same cultivar. For instance, the genetic distance of R2 × R4 (GDtotal = 0.364) was significantly greater than that of L2 × R4 (GDtotal = 0.243). This underscores the complex genetic heterogeneity inherent in loquat, where even intra-cultivar crosses could exhibit genetic differentiation likely due to somaclonal variation or accumulated mutations during polyploidization [6,29]. However, reciprocal triploids exhibited consistently lower genetic distances (GDtotal and GDfilt: 0.101–0.110) compared to non-reciprocal triploids (0.228–0.402) (Figure 3C,D), providing evidence for systematic POE-mediated regulation independently of allelic diversity. This validates our experimental system for isolating POE from genetic background variations, enabling precise quantification of parental genome dosage contributions to heterotic phenotypes. It is important to clarify that while we use the ter POE to accurately describe the observed phenotypic differences arising from the direction of the cross, this phenomenon is fundamentally a specific manifestation of a broader ‘Genomic Dosage Effect’ (GDE), driven by the imbalanced contribution of parental genomes. In line with this, our findings extend observations from banana, where 4x maternal genomes primarily drive growth traits, while 2x paternal genomes influence disease resistance [30], highlighting the role of POE across diverse crop species. Notably, the L2 × L4 reciprocal crosses, exhibiting the lowest genetic distance among all diploid-tetraploid crosses, offered an optimal system for reducing genetic background noise and maximizing POE signal detection.

Using this system with reciprocal triploids, namely 3x(m) and 3x(p), alongside 2x and 4x controls, we quantified heterosis for eight seedling vigor traits at 12 and 24 MAP. Our data revealed distinct MPH and BPH, with plant height and soluble starch content as the most robust indicators of positive heterosis, particularly in 3x(p) hybrids (Figure 4A). Remarkably, plant height heterosis peaked at 12 MAP, while soluble starch content was more significant at 24 MAP. This temporal shift suggests developmental stage-specific POE, with early growth potentially linked to paternal dosage effects on cell division and later metabolic traits reflecting prolonged physiological processes and resource allocation [31]. Similar stage-specific heterosis is observed in allotetraploid canola (Brassica napus) hybrids, exhibiting dynamic gene expression for photosynthesis, glycolysis, and stress resistance across developmental stages [32]. Nevertheless, traits like chlorophyll content and stomata density showed mixed or negative heterosis. This indicates the trait-specific responses to ploidy, parental dosage and hybridity, as exemplified by Arabidopsis studies showing paternal dosage enhances rosette leaf volume but can negatively affect growth rate and photosynthesis [11], and by sugar beet, where heterozygosity more strongly impacts root and sugar yield than gene dosage, though paternal dosage regulates seed vigor and ovule size [33]. Additionally, box plot analyses further confirmed 3x(p) superiority in median values for plant height and soluble starch content, with statistical significance (p < 0.05; Figure 4B,C), highlighting POE as a key driver rather than triploidy alone.

Factorial contribution analysis reveals that POE is the decisive factor driving heterosis in triploid loquat. For plant height, POE not only counteracted but surpassed the negative effects of the hybridity (−12.75%) and elevated ploidy level (−20.87%). This phenomenon points to a dosage-dependent regulatory mechanism where the paternal-excess genome dosage confers a significant growth advantage. This could be mediated by several factors, such as the altered expression of dosage-sensitive genes involved in cell division and growth, or other POE-specific epigenetic modifications, which collectively enhance overall vigor [34]. In contrast, soluble starch content demonstrated a more synergistic interplay, with triploid advantages amplified by complementary positive contributions from hybridity and POE, suggesting optimized resource allocation by elevated ploidy [17]. These findings are consistent with observations in Arabidopsis allopolyploids, where POE influences dosage-dependent gene regulation for starch metabolism [16,27,35].

In summary, our findings provide a practical strategy for improving the breeding efficiency of seedless loquat. We propose prioritizing paternal-excess (2x × 4x) crosses and utilizing our developed InDel markers for the efficient selection of highly vigorous 3x(p) hybrids at the seedling stage. Nonetheless, this conclusion was drawn on seedling-stage performance and requires long-term validation to determine if the early vigor is predictive of desirable fruit traits. Furthermore, an in-depth understanding into the roles of allele-specific expression (ASE) and allele-specific methylation (ASM) is necessary to unravel the mechanism basis of POE-driven triploid heterosis.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/horticulturae11101175/s1. Figure S1. Parental plants and their fruit cross-sections. A, Diploid parent L2. B, Tetraploid parent L. C, Diploid parent R2. D, Tetraploid parent R4; Figure S2. Normal distribution of seedling growth traits of all hybrid progeny and their corresponding parental controls at 24 months after planting. A, Seedling height. B, Leaf area. C, Leaf number. D, Soluble starch content. E, Chlorophyll A content. F, Chlorophyll B content. G, Total chlorophyll content. H, Stomatal density; Table S1. Information of InDel marker sequences and corresponding primer sequences; Table S2. Identification of hybrid and InDel universality information; Table S3. Statistics of SNP annotation results for whole genome resequencing; Table S4. Eight traits in diploid, triploid and tetraploid plants over two years; Table S5. Mid-parent advantage and over-parent advantage of eight traits in diploid, triploid and tetraploid hybrids over two years.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.Z. and G.L.; methodology, C.Z.; software, T.Y.; formal analysis, T.Y. and D.W.; investigation, C.Z. and L.J.; resources, G.L. and Q.G.; data curation, J.D.; writing—original draft preparation, C.Z.; writing—review and editing, G.L. and D.W.; visualization, J.L.; supervision, G.L. and D.W.; project administration, D.W.; funding acquisition, G.L. and Q.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 31701876), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2023YFD1600804-4), and the Chongqing Science and Technology Commission (CSTB2025NSCQ-GPX0548).

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Figure A1.

Heatmap representing the MPH and BPH values for eight seedling traits across specific cross combinations at different ploidy levels. The y-axis lists reciprocal crosses (i.e., L2 × R2 and R2 × L2) grouped by ploidy (2x, 3x, 4x). The x-axis corresponds to the eight seedling traits, color-coded by the bar above the heatmap (matching the ‘Traits’ legend). The color scale on the right indicates the magnitude and sign of the values, ranging from approximately −100 (blue) through white/light colors (near zero) to 100 (red). The legend ‘MB’ indicates MPH and BPH.

References

- Su, W.; Jing, Y.; Lin, S.; Yue, Z.; Yang, X.; Xu, J.; Wu, J.; Zhang, Z.; Xia, R.; Zhu, J.; et al. Polyploidy Underlies Co-Option and Diversification of Biosynthetic Triterpene Pathways in the Apple Tribe. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2101767118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heslop-Harrison, J.S.; Schwarzacher, T. Domestication, Genomics and the Future for Banana. Ann. Bot. 2007, 100, 1073–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmud, E.; Zhu, H.; Kaseb, M.O.; Sajjad, M.Z.; He, N.; Lu, X.; Liu, W. Polyploidization Impact on Plant Architecture of Watermelon (Citrullus lanatus). Horticulturae 2024, 10, 569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lourkisti, R.; Oustric, J.; Quilichini, Y.; Froelicher, Y.; Herbette, S.; Morillon, R.; Berti, L.; Santini, J. Improved Response of Triploid Citrus Varieties to Water Deficit Is Related to Anatomical and Cytological Properties. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2021, 162, 762–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.-S.; Lee, J.-C.; Jeong, H.-N.; Um, N.-Y.; Heo, J.-Y. A Red Triploid Seedless Grape ‘Red Dream’. HortScience 2022, 57, 741–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Zhang, Y.; He, H.; He, G.; Deng, X.W. From Hybrid Genomes to Heterotic Trait Output: Challenges and Opportunities. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2022, 66, 102193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, D.; Curk, F.; Evrard, J.C.; Froelicher, Y.; Ollitrault, P. Preferential Disomic Segregation and C. Micrantha/C. Medica Interspecific Recombination in Tetraploid ‘Giant Key’ Lime; Outlook for Triploid Lime Breeding. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grosser, J.W.; Gmitter, F.G. Protoplast Fusion for Production of Tetraploids and Triploids: Applications for Scion and Rootstock Breeding in Citrus. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2011, 104, 343–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Cheng, Z.-M.; Zhi, S.; Xu, F. Breeding Triploid Plants: A Review. Czech J. Genet. Plant Breed. 2016, 52, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramakrishnan, R.; Banadka, A.; Dubey, S.; Al-Khayri, J.M.; Nagella, P. Advances in Triploid Plant Production: Techniques, Benefits, and Applications. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2025, 160, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fort, A.; Ryder, P.; McKeown, P.C.; Wijnen, C.; Aarts, M.G.; Sulpice, R.; Spillane, C. Disaggregating Polyploidy, Parental Genome Dosage and Hybridity Contributions to Heterosis in Arabidopsis Thaliana. New Phytol. 2016, 209, 590–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duszynska, D.; McKeown, P.C.; Juenger, T.E.; Pietraszewska-Bogiel, A.; Geelen, D.; Spillane, C. Gamete Fertility and Ovule Number Variation in Selfed Reciprocal F1 Hybrid Triploid Plants Are Heritable and Display Epigenetic Parent-of-Origin Ef-fects. New Phytol. 2013, 198, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurid, P.-É. Integration of Architectural Types in French Programme s of Ligneous Fruit Species Genetic Improvement. Fruits 2000, 55, 141–152. [Google Scholar]

- Akpertey, A.; Dadzie, A.M.; Adu-Gyamfi, P.K.K.; Ofori, A.; Padi, F.K. Effectiveness of Juvenile Traits as Selection Criteria for Yield Efficiency in Kola. Sci. Hortic. 2017, 216, 264–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammami, S.B.M.; León, L.; Rapoport, H.F.; de la Rosa, R. A New Approach for Early Selection of Short Juvenile Period in Olive Progenies. Scientia Horticulturae 2021, 281, 109993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, H.; Dogra Gray, A.; Auger, D.L.; Birchler, J.A. Genomic Dosage Effects on Heterosis in Triploid Maize. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 2665–2669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, M.; Zhang, C.; Chen, Z.J. Ploidy and Hybridity Effects on Growth Vigor and Gene Expression in Arabidopsis Thaliana Hybrids and Their Parents. G3 Genes Genomes Genet. 2012, 2, 505–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, J.; Cheng, P.; Wu, D.; Yan, S.; Wang, P.; Wang, H.; Yuan, T.; Xu, Y.; He, Q.; Jing, D.; et al. Triploid and Aneuploid Hybrids Obtained from Hybridization between Eriobotrya Japonica and E. Cavaleriei. Sci. Hortic. 2023, 319, 112135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Yang, Y.; Lei, C.; Xia, Q.; Wu, D.; He, Q.; Jing, D.; Guo, Q.; Liang, G.; Dang, J. A Female Fertile Triploid Loquat Line Produces Fruits with Less Seed and Aneuploid Germplasm. Sci. Hortic. 2023, 319, 112141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varma, A.; Padh, H.; Shrivastava, N. Plant Genomic DNA Isolation: An Art or a Science. Biotechnol. J. 2007, 2, 386–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthaeus, W.J.; Schmidt, J.; White, J.D.; Zechmann, B. Novel Perspectives on Stomatal Impressions: Rapid and Non-Invasive Surface Characterization of Plant Leaves by Scanning Electron Microscopy. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0238589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochatt, S.J. Flow Cytometry in Plant Breeding. Cytom. Part A 2008, 73A, 581–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, W.; Wang, B.; Xiao, Y.; Huang, J.; Wang, D.; Wang, S.; Li, W.; Zhang, Q.; Huang, F.; Shi, C.; et al. InDel Markers for Identifying Interspecific Hybrid Offspring of Apple and Pear. Plants 2025, 14, 646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henry, I.M.; Dilkes, B.P.; Tyagi, A.P.; Lin, H.-Y.; Comai, L. Dosage and Parent-of-Origin Effects Shaping Aneuploid Swarms in A. Thaliana. Heredity 2009, 103, 458–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birchler, J.A.; Veitia, R.A. The Gene Balance Hypothesis: From Classical Genetics to Modern Genomics. Plant Cell 2007, 19, 395–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.J. Molecular Mechanisms of Polyploidy and Hybrid Vigor. Trends Plant Sci. 2010, 15, 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fort, A.; Tuteja, R.; Braud, M.; McKeown, P.C.; Spillane, C. Parental-Genome Dosage Effects on the Transcriptome of F1 Hybrid Triploid Embryos of Arabidopsis Thaliana. Plant J. 2017, 92, 1044–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jullien, P.E.; Berger, F. Parental Genome Dosage Imbalance Deregulates Imprinting in Arabidopsis. PLoS Genet. 2010, 6, e1000885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Wang, D.; Dong, Y.; Ling, Z.; Bai, H.; Jin, X.; Hu, X.; et al. Decoupling Subgenomes within Hybrid Lavandin Provide New Insights into Speciation and Monoterpenoid Diversification of Lavandula. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2023, 21, 2084–2099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barekye, A.; Tongoona, P.; Derera, J.; Laing, M.D.; Tushemereirwe, W.K. Contribution of Synthetic Tetraploids (AAAA) and Diploids (AA) to Black Sigatoka Resistance and Bunch Weight to Their Triploid Progenies. Field Crops Res. 2011, 122, 284–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Yin, Y.; Zhang, A.; Lu, Q.; Wen, X.; Zhu, Z.; Zhang, L.; Lu, C. Comparative Proteomic Study Reveals Dynamic Proteome Changes between Superhybrid Rice LYP9 and Its Parents at Different Developmental Stages. J. Plant Physiol. 2012, 169, 387–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, J.; Hu, K.; Shalby, N.; Zhuo, C.; Wen, J.; Yi, B.; Shen, J.; Ma, C.; Fu, T.; Tu, J. Comparative Transcriptomic Analysis Reveals the Molecular Mechanism Underlying Seedling Biomass Heterosis in Brassica Napus. BMC Plant Biol. 2022, 22, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hallahan, B.F.; Fernandez-Tendero, E.; Fort, A.; Ryder, P.; Dupouy, G.; Deletre, M.; Curley, E.; Brychkova, G.; Schulz, B.; Spillane, C. Hybridity Has a Greater Effect than Paternal Genome Dosage on Heterosis in Sugar Beet (Beta vulgaris). BMC Plant Biol. 2018, 18, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, D.; Mudunkothge, J.S.; Galli, M.; Char, S.N.; Davenport, R.; Zhou, X.; Gustin, J.L.; Spielbauer, G.; Zhang, J.; Barbazuk, W.B.; et al. Paternal Imprinting of Dosage-Effect Defective1 Contributes to Seed Weight Xenia in Maize. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 5366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Zhang, C.; Ko, D.K.; Chen, Z.J. Genome-Wide Dosage-Dependent and -Independent Regulation Contributes to Gene Expression and Evolutionary Novelty in Plant Polyploids. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2015, 32, 2351–2366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).