Abstract

Chemical traits (primary and secondary metabolites) are important features of plants. An increasing number of studies have focused on the ecological significance of secondary metabolites in plant parts, especially in pollen. Ericaceae species exhibit significant morphological variations and diverse colors, are widely distributed throughout China and are popular ornamental garden plants. The chemical trait of pollen in Ericaceae species and their potential ecological significance remain unclear. We selected a total of nine Ericaceae species from three nature reserves in southwestern China, which were the predominant flowering Ericaceae plants for each site, and measured their floral characteristics, nectar volume and sugar concentration. We determined the types of pollinators of these species based on a literature review and used UPLC-QTOF-MS to analyze the types and relative contents of primary metabolites (amino acids and fatty acids) and secondary metabolites (terpenoids, phenolics and nitrogenous compounds) in the pollen and other tissues, including the stems, leaves, petals and nectar. The results showed that each species exhibited unique floral characteristics. Enkianthus ruber, Pieris formosa, Rhododendron agastum, R. irroratum, R. virgatum and R. rubiginosum were pollinated by bees, and R. delavayi, R. decorum and R. excellens were pollinated by diverse animals (bees, birds and Lepidoptera). The pollen of these Ericaceae species was rich in phenolics and terpenoids, especially flavonoids. Grayanotoxin, andromedotoxin and asebotin (toxic diterpene compounds) were also detected in the pollen of some of the Ericaceae species in our study, and their response value was low. The relative contents and diversity of secondary metabolites in the pollen were higher than those in the nectar but lower than those in the leaves, petals and stems. The five chemical compounds with the highest content (four flavonoids, one triterpene) in the pollen were also detected in the stems, leaves and petals, and the response value of most of these chemicals in pollen was not significantly correlated with that in other tissues. Rhododendron species has a closer relationship with chemical traits in pollen compared with Enkianthus and Pieris species. The response value of total secondary metabolites in the pollen of species pollinated only by bees was higher than that of species pollinated by diverse animals. Our research indicates that the pollen of ericaceous species contains a wide array of metabolites, establishing a foundation for advancing the nutritional potential of the pollen of horticultural ericaceous species and deepening our understanding of its chemical and ecological significance.

1. Introduction

Chemical traits (types and contents of chemical compounds) are important features of plants, and plant secondary metabolites (mainly including terpenoids, phenolics and nitrogenous compounds) play a crucial role in coordinating plant interactions with biotic and abiotic factors [1,2,3]. In recent years, attention has been focused on the adaptive significance of secondary metabolites in floral tissues, especially in pollen. There are three hypotheses that may explain the existence of defensive metabolites in pollen: the pleiotropy hypothesis, the antimicrobial hypothesis and the protection-against-pollen-collection hypothesis [4], the last of which proposes that plants experience selection to reduce pollen losses to poor-quality pollinators [5]. The contents of secondary metabolites such as terpenes [6], alkaloids [7] and phenols [8] in pollen, as well as their toxicity and digestibility, have a profound impact on the foraging behavior of pollinators such as bees [9,10,11,12,13].

Ericaceae species are distributed worldwide. In China, there are 22 genera and approximately 826 species, which exhibit significant morphological variations and diverse colors; they are widely distributed throughout China, mainly in the mountainous areas of the southwestern region. Many genera and species of Ericaceae are popular ornamental garden plants that have been widely used around the world, commonly including Rhododendron and Enkianthus species in China. Multiple chemical components have been identified in Ericaceae, including flavonoids, volatile oils, coumarins, phenolic compounds and diterpenoid toxins, and they are used in the pharmaceutical and healthcare and personal product industries. It is known that some species of Rhododendron and Pieris have varying degrees of toxicity in their leaves and flowers, which can cause poisoning in humans and animals. The most toxic components are tetracycline diterpenoid toxins and andromedotoxin [14]. Rhododendron, one of the largest ericaceous genera, produces pollen arranged in tetrads, with outer walls displaying various ornamentation, and the pollen grains within the anthers are connected by viscin threads, facilitating the quantification of pollen removal and deposition. Rhododendron species are pollinated not only by bees but also by other animals (e.g., birds or Lepidoptera) [15,16]. For example, Song et al. [16] found that birds pollinated R. cyanocarpum, R. delavayi, R. lacteum and R. neriiflorum; butterflies pollinated R. yunnanense; moths pollinated R. decorum and R. edgeworthii; and bees pollinated R. microphyton, R. racemosum, R. rubiginosum, R. simsii, R. trichocladum and R. virgatum.

Flavonoids and diterpenoid compounds have been reported in Rhododendron species. Huang et al. [17] identified seven flavonoids, namely, myricetin-3-O-β-D-glucoside, myricetin-3′-O-β-D-xylopyraoside, hyperoside, isoquercitin, avicularin, quercitroside and quercetin, in the leaves and green branches of R. mariae with UPLC-QTOF-MS. Duan et al. [18] tentatively identified about three hundred metabolites from the healthy and petal blight flowers of Rhododendron agastum using UPLC-QTOF-MS/MS. Our previous research found that three Rhododendron species were rich in flavonoids, steroids, terpenes, phenylpropanoids and alkaloids (with UPLC-QTOF-MS), and the secondary metabolites of Rhododendron species were not easily influenced by environmental factors such as altitude, light, temperature, and humidity [19]. The nectar of R. ponticum is rich in grayanotoxins (diterpenoid toxins, LC-MS analysis method) [20].. The grayanotoxins are lethal to honeybees and sublethal to solitary bees but do not exhibit adverse effects on the survival or behavior of bumblebees, and the three primary pollinator groups exhibit varying responses to the nectar toxin found in R. ponticum [21]. Furthermore, grayanotoxin I is a significant toxin found in the leaves of Rhododendron species (LC-MS), and its concentration is notably higher in leaves compared to petals and nectar, which suggests that Rhododendron species may often face a functional trade-off between defending themselves against herbivores and attracting pollinators [22]. The chemical traits of pollen of Ericaceae species remain unclear. It is unknown whether the pollen of Ericaceae species contains toxic chemicals, whether the chemicals in pollen are related to those in other tissues (such as stems, leaves, petals, nectar) and whether the chemical traits in pollen among different genera of Ericaceae species are different.

To investigate the floral traits, pollinator types and, in particular, chemical traits in the pollen and other tissues of nine common Ericaceae species in southwestern China, we measured the floral traits as well as nectar volume and nectar sugar concentration and identified the types of pollinators of the nine Ericaceae by reviewing the literature [15,16,23,24,25,26] and based on our own observation. The UPLC-QTOF-MS analysis method was used to analyze the chemical compounds in the stems, leaves, petals, pollen and nectar.

2. Materials and Methods

We selected nine Ericaceae species in this study: one Enkianthus species (E. ruber), one Pieris species (P. formosa) and seven Rhododendron species (R. agastum, R. delavayi, R. decorum, R. irroratum, R. excellens, R. virgatum and R. rubiginosum) (Figure 1A–J). We conducted research on R. agastum, R. delavayi and R. irroratum at the Baili Rhododendron Nature Reserves, Bijie city, Guizhou province (105°45′–106°4′ E, 27°8′–27°20′ N), in April 2020, which were the dominant species of the Baili Rhododendron Nature Reserve at this time of year according to Hu et al. [27]. Research on R. decorum, R. virgatum and R. rubiginosum was conducted at Cangshan Nature Reserve, Dali City, Yunnan province (25°41′ N, 100°5′ E), during early May 2020, which were the predominant flowering Ericaceae plants at Cangshan during this time period. Research on E. ruber, P. formosa and R. excellens was conducted at Laoshan Nature Reserve, Malipo County, Yunnan province (104°49′ E, 23°94′ N) in mid-May 2020. They were the dominant Ericaceae species at Laoshan during this period. The pollinator types and behavior of these nine Ericaceae species have mostly been reported in detail.

Figure 1.

Inflorescences of nine Ericaceae species showing diverse floral morphology: (A) Enkianthus ruber, (B) Pieris formosa, (C) Rhododendron agastum, (D) R. delavayi, (E) R. decorum, (F) R. irroratum, (G) R. excellens, (H) R. virgatum, (I) R. rubiginosum; measurement of floral characteristics (J) of nine Ericaceae species (R. rubiginosum as an example) a: corolla length, b: corolla width, c: tube length, d: floral opening diameter, e: pistil length, f: stamens length, g: anther length, h: anther width, i: anther thickness, j: stigma length, k: stigma width, l: stigma thickness. Honeybee (Apis, (K)) and bumblebee (Bombus, (L)) pollinated Enkianthus ruber. Two different bumblebees (M,N) pollinated Pieris formosa. The E. ruber, P. formosa, R. agastum, R. irroratum, R. virgatum, R. rubiginosum were pollinated only by bees (bumblebees and honeybees). R. delavayi, R. decorum, R. excellens were pollinated not only by bees but also by other animals (birds and Lepidoptera).

2.1. Measurement of Floral Traits

To investigate the floral traits of E. ruber, P. formosa, R. agastum, R. delavayi, R. decorum, R. irroratum, R. excellens, R. virgatum and R. rubiginosum, we randomly collected 20 flowers from 20 different individuals in field populations and measured twelve reproductive traits (comprising corolla length, corolla width, floral tube length, flower opening diameter, pistil length, stamen length, anther length, anther width and anther depth, stigma length, stigma width and stigma depth) to 0.01 mm using a caliper micrometer. The measurements of floral characteristics are shown in Figure 1K. These floral features were important because they indicated the flower’s size and the spacing between stamens and pistils. We could even predict the effectiveness of pollinators based on whether the size of an insect’s body mechanically matched the floral features.

To investigate nectar volume and concentration among the nine Ericaceae species, we randomly bagged and labeled 25 flower buds before anthesis from 25 different plants in each species. During the first day of flowering, nectar was extracted from bagged flowers between 8:00 am and 10:00 am using glass microcapillary tubes. We gently collected nectar by inserting microcapillary tube into the base of the flowers. The nectar is naturally drawn into the tubes due to capillary pressure. If one microcapillary tube is insufficient, we use two or three microcapillary tubes until all the nectar in the flowers is fully collected. The length (L) of microcapillary tube occupied by nectar was measured with a caliper micrometer. The total volume (Vtotal) and length (Ltotal) of one standard microcapillary were calculated. The volume of each nectar sample (V) is equal to L/Ltotal ∗ Vtotal. Nectar sugar concentration was measured (as g sugar per 100 g solution) with a handheld refractometer (Eclipse 0–50%, 45–80%; Bellingham and Stanley Ltd., Basingstoke, United Kingdom).

2.2. The Types and Behavior of Pollinators of the Nine Ericaceae Species

We identified the types and behavior of the pollinators of Rhododendron agastum [23], R. delavayi [15,16,24], R. decorum (Huang 2015; Song et al., 2018) [16,24], R. irroratum [24,26], R. excellens [25], R. virgatum [16] and R. rubiginosum [16,24] using a literature review. The pollinator types and behavior of Enkianthus ruber and Pieris formosa were not identified with certainty in the review. To identify the pollinator types and behavior of E. ruber and P. formosa, we randomly chose about 15 individuals each for E. ruber and P. formosa, respectively, at Laoshan Nature Reserve and observed pollinator behavior from 9:00 am to 10:00 pm on May 10, 12, 13 in 2020. We recorded the types of visitors and whether the insects contacted pollens and conspecific stigmas during their visit. Each session lasted 30 min and we conducted pollinator observation for at least 30 h.

2.3. Metabolites in Different Tissues of the Nine Ericaceae Species

To compare the metabolites, including primary (amino acids and fatty acids) and secondary metabolites (terpenoids, phenolics and nitrogenous compounds) of pollen and other tissues, including the stems, leaves, petals, and nectar of these nine Ericaceae species, we randomly chose three plants per species and collected fresh stems, leaves and petals separately in the field populations and kept them dry using a silica-gel desiccant. In each plant, we randomly chose three buds and bagged them. The flowers were unbagged when the anthers were newly dehisced, and we collected the pollen grains and nectar in sufficient amounts (at least 0.1 g). The pollen grains and nectar were stored at −20 °C before extraction and chemical analysis. In each plant, the stems, leaves, petals, pollen and nectar were all collected and marked with a corresponding number.

The frozen nectar was redissolved at room temperature, and then samples of 0.01 g were weighed with a microbalance (Sartorius BAS124S). We added 1 mL methanol to the nectar samples and extracted for 48 h. Next, 0.01 g of stems, leaves, petals and pollen samples were weighed and then sonicated (ultrasonic homogenizer, JY92-IIDN) for 7 min with 1 mL methanol in a 2 mL microcentrifuge tube. They were then incubated without shaking for 48 h at room temperature. The samples were centrifuged for 6 min at 8000 rpm (Centrifuge 5430R, Eppendorf), and the supernatant was transferred to a vial (1.5 mL).

The chemical compounds in different tissues were analyzed using ultra-performance liquid chromatography (ACQUITY UPLC H-class; Waters) with a flow-through-needle (FTN) sample manager using quadrupole/time-of-flight mass spectrometers (Xevo G2-XS QTof; Waters). First, 2 μL aliquots of tissue extract were injected into a C18 column (ACQUITY UPLC BEH, 1.7 μm, 2.1 mm × 100 mm, 40 °C). Acquisition mode: ESI+, MS. Acquisition range: 50–1500 Da (scanning time 0.1 s). Samples were eluted with solvents: A, H2O (with 0.01% formic acid); B, Acetonitrile (with 0.01% formic acid). The program was as follows: A = 95%, B = 5% at 0 min; A = 95%, B = 5% at 2 min; A = 2%, B = 98% at 17 min; A = 2%, B = 98% at 20 min. The flow rate was 0.4 mL/min. Three samples were analyzed for stems, leaves, petals, pollen and nectar from the nine Ericaceae species.

UPLC-QTOF-MS has been widely used to identify or tentatively identify the chemical compounds in plants [28,29,30,31]. UPLC has been utilized for high-resolution chromatographic separation, offering exceptional sensitivity and faster analysis of chemical ingredients in natural product extracts [32] and high-resolution mass spectrometers. Quadrupole/time-of-flight mass spectrometers (QTOF-MS) provide accurate mass information with low mDa precision (e.g., <5 mDa), enabling the prediction of the elemental composition of chemical entities. Furthermore, the fragment ion data generated by these spectrometers can be utilized for structural confirmation, even in the absence of pure standards. High-throughput screening solutions for natural products require automated data processing and scientific libraries to facilitate the identification of both known and unknown chemical ingredients in natural product extracts. Using the UNIFI data processing workflow, component information is automatically matched with the traditional medicine library following the 2010 edition of the Chinese Pharmacopoeia for potential identifications. The traditional medicine library within UNIFI contains over 6000 compounds derived from 600 herbs, including names (in both Mandarin and English), chemical structures, molecular formulas, average molecular masses, mono-isotopic molecular masses, and plant origins for each compound.

We also created a customized library (see Table S1) of chemical compounds of Enkianthus, Pieris, Rhododendron that includes their chemical structure (mol. files), chemical name based on references [33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41]. The traditional medicine library (2010 edition of the Chinese Pharmacopoeia) and the customized library were incorporated into the UNIFI analysis method to show chemical components with a good match. The listed chemical component of each sample contains the following information: compound name, molecular formula, exact mass mono-isotopic molecular weight, response intensity, retention time, exact mass error in mDa or ppm, ionization mode, adduct ions and identification status. The results could be summarized directly as component tables or component plots. The value of response intensity (unit: counts) represented the iron peak area of each chemical [30]. Each sample had the same weight and volume and was analyzed using the same methods. Therefore, the higher the content of a given chemical substance in one sample, the larger the iron peak area and the greater the value of response intensity. PubChem (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) (assessed on 17 September 2024), Chemical Book (https://www.chemicalbook.com/) (accessed on 18 September 2024), MedChemExpress (http://www.medchemexpress.cn) (accessed on 17 September 2024) and Chemsrc (https://www.chemsrc.com) (accessed on 18 September 2024) were supplementarily used to analyze the chemical components.

2.4. Data Analysis

To visualize the difference in floral traits (corolla length, corolla length, floral tube length, flower opening diameter, pistil length, stamen length, anther length, anther width, anther depth, stigma length, stigma width and stigma depth) among the nine Ericaceae species, we used non-metric multi-dimensional scaling (NMDS) based on the Bray–Curtis distances between each species’ floral traits with the vegan package in R. To further quantify the significance of differences in floral traits among species, a PERMANOVA analysis across the nine Ericaceae species was conducted in with the adonis package in R. To illustrate the varying scale of floral traits among the nine species and further explore the differences in these traits among the different species, we compared them using a generalized linear model (GLM) with normal distribution and identity-link function, with the floral traits as the dependent variable and the species as the factor. To explore whether the chemicals in pollen were related to those in other tissues, Pearson correlation analysis of the five most common chemicals in pollen and those in stems, leaves and petals was conducted. We compared the value of response intensity of chemicals in pollen among the different species at each research site with normal distribution and identity-link function, using the value of response intensity of chemicals in pollen as the dependent variable and the species as the factor. GLM analysis and Pearson correlation analysis were conducted using SPSS 20.0 software.

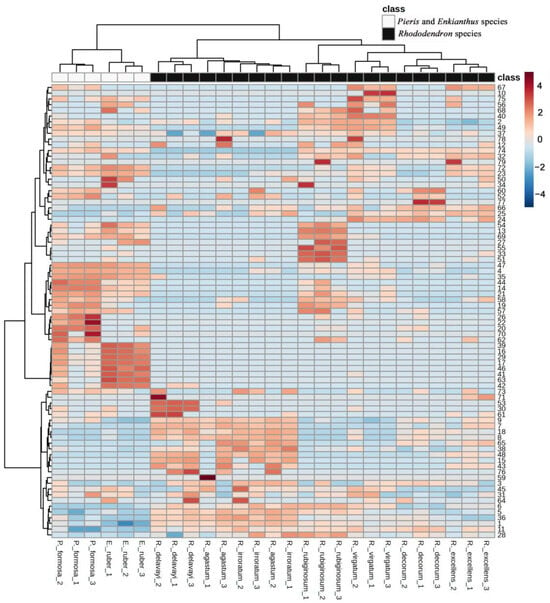

We performed a hierarchical cluster analysis (HCA) and created cluster heat maps to show the value of response intensity (representing the iron peak area) for each chemical in each pollen sample from the nine Ericaceae species. The HCA was performed and graphs were generated using MetaboAnalyst6.0 (https://www.metaboanalyst.ca/MetaboAnalyst/ModuleView.xhtml) (accessed on 25 September 2024). The data for the chemical response value were standardized with Log10 function conversion.

3. Results

3.1. Comparison of Floral Traits Among the Nine Ericaceae Species

Based on the fusion of petals, the flower morphology of the nine Ericaceae species could be categorized into three types: open funnel-shaped, bell-shaped or tubular. The diameters of these flowers range from approximately 5 to 110 mm, and they exhibit a variety of colors: white, yellow, pink, red and purplish red (Figure 1). Each species exhibited unique floral characteristics, visible using NMDS multivariate ordination based on the twelve floral traits that were measured (Figure 2). A PERMANOVA analysis of the floral characteristics across nine Ericaceae species showed that different species had distinct floral traits (F8,171 = 334.04, p = 0.001). The corolla length (107.80 ± 2.94 mm), corolla widths (110.48 ± 2.73 mm), floral tube length (83.54 ± 1.45 mm), floral opening diameter (70.54 ± 2.29 mm), pistil length (105.99 ± 2.50 mm), stamen length (82.47 ± 2.18 mm), anther length (10.84 ± 0.17 mm), anther width (2.45 ± 0.07 mm), anther thickness (1.57 ± 0.03 mm), stigma length (6.03 ± 0.13 mm), stigma width (5.31 ± 0.12 mm) and stigma thickness (2.89 ± 0.08 mm) of R. excellens were all significantly larger than those of the other eight Ericaceae species (all p < 0.05, Table 1).

Figure 2.

Non-metric multi-dimensional scaling-based ordination of Bray–Curtis distances of floral traits among Enkianthus ruber, Pieris formosa, Rhododendron agastum, R. decorum, R. delavayi, R. excellens, R. irroratum, R. rubiginosum, R. virgatum. Samples clustered strongly by species. Ellipses show 95% confidence bands for floral traits (dotted line). Colors indicate different species. Ordinations are based on the floral traits of corolla length, corolla width, floral tube length, flower opening diameter, pistil length, stamen length, anther length, anther width and anther depth, stigma length, stigma width and stigma depth.

Table 1.

Comparison of floral traits (mean ± SE) among Enkianthus ruber, Pieris ormosa, Rhododendron agastum, R. delavayi, R. decorum, R. irroratum, R. excellens, R. virgatum and R. rubiginosum with GLM. For each trait, the different lowercase at the upper right of the value indicated a significant difference between species (p < 0.005). The species with the largest value is highlighted in bold for each floral trait.

There were significant differences in nectar volume and nectar concentration among the nine Ericaceae species (Table 1). The nectar volume (17.30 ± 2.09 μL) of R. agastum was larger than that of the other species (Wald χ2 =320.70, df = 8, p < 0.001), and the nectar sugar concentration (66.96 ± 2.43%) of R. virgatum was higher than that of the other species (Wald χ2 = 1186.33, df = 8, p < 0.001).

3.2. Identification of the Types of Pollinators of the Nine Ericaceae Species

According to related studies and our own observations, six species (Enkianthus ruber, Pieris formosa, Rhododendron agastum, R. irroratum, R. virgatum, R. rubiginosum) were pollinated only by bees (bumblebees and honeybees) (henceforth ’bee-pollinated’). Three species (R. delavayi, R. decorum, R. excellens) were pollinated not only by bees (bumblebees and honeybees) but also by other animals (birds and Lepidoptera) (henceforth ’diverse animal-pollinated’).

Specifically, E. ruber was pollinated by honeybees (Figure 1L) and bumblebees (Figure 1M). P. formosa was pollinated by bumblebees (Figure 1N,O). R. agastum was pollinated by honeybees (Apis cerana). R. irroratum was pollinated by bumblebees and honeybees (A. cerana). R. virgatum was pollinated by bumblebees (B. avanus, B. festivus, B. friseanus) and honeybees (A. cerana). R. rubiginosum was pollinated by bumblebees (B. festivus) and honeybees (A. cerana). R. delavayi was pollinated by birds (Heterophasia melanoleuca, Leiothrichidae; Pycnonotus jocosus, Pycnonotidae; Aethopyga gouldiae, Nectariniidae), bumblebees (B. friseanus) and honeybees (A. cerana). R. decorum was pollinated by moths, bumblebees (B. festivus) and honeybees (A. cerana). R. excellent was pollinated by bumblebees (B. flavescens) and honeybees (A. cerana) during the day and by hawkmoths (Acosmeryx naga, Cechetra lineosa, Cechetra scotti, Daphnis hypothous, Notonagemia analis) at night.

3.3. Chemical Composition Analysis

The Pieris formosa was taken as an example, and its base peak chromatograms of the stems, leaves, petals, pollen and nectar by UPLC-QTOF-MS were shown in Figure 3. We analyzed chemical substances with a high value of response intensity in stems, leaves, petals, pollen and nectar, as well as typical toxic diterpenoids in Rhododendron. The cumulative average response values of these substances constitute 95% of the total response values for all chemicals detected. The chemical substance with a low value of response intensity and only detected in one or two samples were considered unstable and uncertain results and were ignored. Since our primary focus is on the chemical traits of pollen, Table 2 provides detailed information on the chemical compounds characterized and tentatively identified in pollen. Additionally, Table 3 highlights the five chemical compounds with the highest relative amount in the stems, leaves, petals, pollen and nectar. All the compounds were characterized by interpreting their mass spectra and taking into account the data provided by the references. In this study, the compounds are classified into five groups: amino acid, fatty acid, terpenoids (including diterpenes and triterpenes), phenolics (including flavonoids, phenylpropanoids, quinoids, phenolic aldehydes) and nitrogenous compounds.

Figure 3.

The peak chromatogram of stem, leaf, petal, pollen and nectar of Pieris formosa analyzed with UPLC-Qtof-MS. Different color indicate different plant tissure.

Table 2.

The chemical compounds tentatively identified in the pollen of Enkianthus ruber, Pieris ormosa, Rhododendron agastum, R. delavayi, R. decorum, R. irroratum, R. excellens, R. virgatum and R. rubiginosum with UPLC-QTOF-MS.

Table 3.

The five chemical compounds with the highest content are the stem, leaf, petal, pollen and nectar of nine Ericaceae species. ‘Presence’ represents the number of species in which the substance was present. ‘Percent of response intensity (%)’ represents the value of response intensity of this substance/the total value of response intensity of chemical compounds *100.

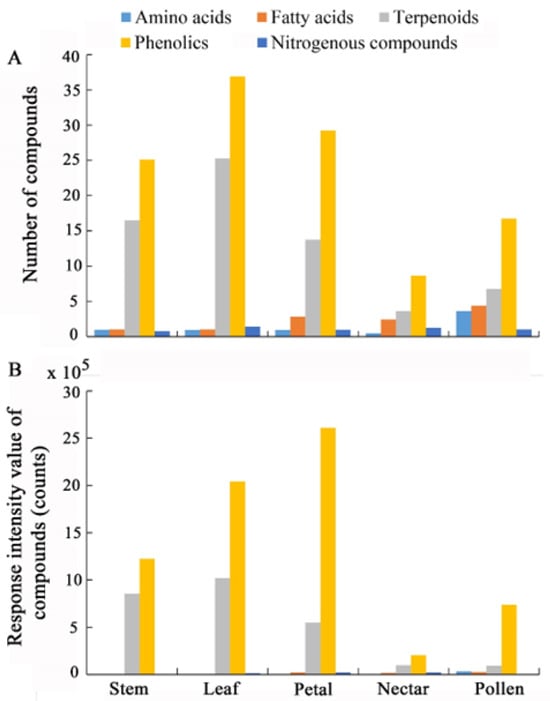

The numbers of chemical substances tentatively identified in leaves (138) and petals (98) were higher than those in pollen (79), stems (78) and nectar (49). The stems, leaves, petals, pollen and nectar of these nine Ericaceae species were all richer and more abundant in terpenoids and phenolics (Figure 4A,B). For stems, the value of response intensity of phenolics (1.22 × 106 counts) and terpenoids (8.55 × 105 counts) were higher than that of fatty acid (2.85 × 103 counts), nitrogenous compounds (2.23 × 103 counts) and animo acid (1.87 × 103 counts). For leaves, the value of response intensity of phenolics (2.04 × 106 counts) and terpenoids (1.02 × 106 counts) were higher than that of nitrogenous compounds (1.41 × 104 counts), fatty acid (4.75 × 103 counts) and animo acid (1.52 × 103 counts). For petals, the value of response intensity of phenolics (2.61 × 106 counts) and terpenoids (5.49 × 105 counts) were higher than that of nitrogenous compounds (2.05 × 104 counts), fatty acid (2.12 × 104 counts) and animo acid (4.32 × 103 counts). For nectar, the value of response intensity of phenolics (2.03 × 105 counts) and terpenoids (9.90 × 104 counts) were higher than that of nitrogenous compounds (2.08 × 104 counts), fatty acid (1.80 × 104 counts) and animo acid (2.23 × 103 counts). For pollen, the value of response intensity of phenolics (7.37 × 105 counts) and terpenoids (9.20 × 104 counts) were higher than that of animo acid (3.29 × 104 counts), fatty acid (2.52 × 104 counts) and nitrogenous compounds (3.93 × 103 counts) (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

Number of chemical compounds (mean, (A)) and response intensity values of chemical compounds (mean, (B)) in the stem, leaf, petal, pollen and nectar for all the nine Ericaceae species. The chemical compounds include amino acids (in light blue), fatty acids (in orange), terpenoids (in gray), phenolics (in yellow) and nitrogenous compounds (in deep blue).

The five chemical compounds with the highest relative amount in stems, leaves, petals, pollen and nectar of the nine Ericaceae species are shown in Table 3. Olean-12-ene-3,11-dione (a triterpene) appeared in stems (17.69%, 9; response value of this substance as a percentage of the total chemical response value, number of species in which it was present), leaves (9.21%, 9) and pollen (3.04%, 8). Procyanidin B4_1 (a flavonoid) appeared in the stems (9.19%, 9), leaves (4.41%,9) and petals (22.41%, 6). Quercetin (a flavonoid) appeared in the stems (7.07%, 9), leaves (13.69%, 9), petal (22.41%, 9), pollen (5.38%, 9). The flavonoid kaempferol appeared in the petals (7.74%, 9) and pollen (48.45%, 9).

The response value of kaempferol, apigenin 7-O-glucoside and olean-12-ene-3,11-dione in the pollen was not significantly related to that in the stems, leaves and petals (all p > 0.05). The response value of quercetin in pollen was significantly positively correlated with that in the stems (r = 0.433, p = 0.024) and petals (r = 0.432, p = 0.025), and was not significantly related with that in leaves (r = 0.209, p = 0.295). The response value of quercetin 7-O-α-L rhamnoside in the pollen was significantly positively correlated with that in the leaves (r = 0.504, p = 0.007) and was not significantly related with that in stem and in petal (all p > 0.05) (Table 4).

Table 4.

The Pearson’s correlation of the five most common chemicals (Kaempferol, Quercetin, Apigenin 7-O-glucoside, Olean-12-ene-3,11-dione, Quercetin 7- O-α-L rhamnoside) in pollen and these chemicals in stem, leaf and petal of nine Ericaceae species. “/” indicated Apigenin 7-O-glucoside was not detected in the stem. The values significantly correlated with were in bold.

Grayanotoxin I, grayanotoxin VII, grayanotoxin IX, andromedotoxin, rhodojaponin VI and asebotin were also detected in the stems, leaves, petals, pollen and nectar of these nine Ericaceae species (Table 5). The value of response intensity of these well-known toxic diterpene compounds in the petals was larger than that in other tissues and the response value of these toxic chemical compounds in the pollen was low.

Table 5.

The value of response intensity of grayanotoxin I, grayanotoxin VII, grayanotoxin IX, andromedotoxin, rhodojaponin VI, asebotin (well-known toxic diterpene compounds) in the stems, leaves, petals, pollen and nectar of nine Ericaceae species. “/” indicates the diterpene compound was not detected in the tissue of the species.

The hierarchical clustering analysis showed the value of response intensity of each chemical in all the pollen samples from the nine Ericaceae species. Three samples of the pollen metabolites from one species were clustered together except R. agastum. The inconsistency of sampling habitats in the wild may lead to differences in their chemical composition. Seven Rhododendron species were clustered on one branch, P. formosa, and E. ruber were clustered on another branch. This result indicated that Rhododendron species have a closer chemical relationship compared with species from other genera of Ericaceae (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Heat map cluster analysis of chemical value of response intensity in pollen 496 of Enkianthus ruber and Pieris formosa (in open bar); Rhododendron species (R. agastum, R. delavayi, R. decorum, R. irroratum, R. excellens, R. virgatum, R. rubiginosum, in black) after UPLC-Qtof-MS analysis. For the heat map cluster analysis, high and low abundance are indicated by red and blue colors. The numbers 1–79 represent chemical names, which are shown in Table 2.

In Baili Rhododendron Nature Reserve, the value of response intensity of secondary metabolites in the pollen of R. irroratum (bee-pollinated species), R. agastum (bee-pollinated species) and R. delavayi (diverse animal-pollinated species) was not significantly different (Wald χ2 = 3.659, df = 2, p = 0.160) (Figure 6A). In Cangshan Nature Reserve, the value of response intensity of secondary metabolites in pollen for R. rubiginosum and R. virgatum (bee-pollinated species) was significantly higher (Wald χ2 = 53.365, df = 2, p < 0.001) than that for R. decorm (diverse animal-pollinated species) (Figure 6B). In Laoshan Nature Reserve, the value of response intensity of secondary metabolites in the pollen of P. formosa (bee-pollinated species) was significantly higher than that of R. excellens (diverse animal-pollinated species) (Wald χ2 = 8.322, df = 2, p = 0.016), and was not significantly different from E. ruber (bee-pollinated species) (Figure 6C).

Figure 6.

Comparison of value of response intensity of pollen of R. irroratum, R. agastum and R. delavayi in Baili Rhododendron Natural reserves. The value of response intensity of pollen of R. rubiginosum, R. decorm and R. virgatum in Cangshan Natural Reserve. The value of response intensity of secondary metabolites in pollen for P. formosa, E. ruber and R. excellens in Laoshan Natural reserves. Bee-pollinated species are in open bars and diverse animal-pollinated species are in grey bars. Different words above the bars indicate significant differences among species. The number in the bar represents the number of pollen samples for each treatment.

4. Discussion

The size, color and shape of the flowers, as well as the nectar volume and nectar sugar concentration, varied significantly among the nine Ericaceae species. The number of chemical compounds and the value of response intensity of the secondary metabolites in the Ericaceae species were all larger than those of the primary metabolites. The Ericaceae species were rich in terpenoids and phenolics. The response intensity of the secondary metabolites in the petals, leaves and stems was significantly larger than that in the pollen and nectar, and the number of chemical compounds and value of response intensity of secondary metabolites were higher in the pollen than in the nectar. The five chemical compounds with the highest content (four flavonoids, one triterpene) in pollen could also be detected in the stems, leaves and petals, but not detected in nectar. Only the response value of quercetin in the pollen was significantly positively correlated with that in the stems and petals, and the response value of quercetin 7-O-α-L rhamnoside in the pollen was significantly positively with that in the leaves. The pollen of some species also contained low contents of toxic diterpene compounds. Rhododendron species have a closer relationship for chemical traits in pollen compared with species from other genera of Ericaceae. The total value of response intensity of the secondary metabolites in the pollen of the bee-pollinated species was larger than that of the diverse animal-pollinated species.

4.1. Ecological Significance of Secondary Metabolites in Pollen

Secondary metabolites (mainly including terpenoids, phenolics and nitrogenous compounds) in pollen play a crucial role in coordinating plant interactions with visitors [5,42,43](Wang et al., 2019; Brochu et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2024). Pollen plays two important roles in angiosperm reproduction. As male gametes of plants, pollen carries the male gametophyte for plant reproduction. Pollen is usually the reward that plants give to pollinators because pollen provides essential amino acids and proteins for the growth and development of the larvae of bees and other insects. Pollen removed by bees cannot be used for reproduction. As pollen resources are limited, if the pollen is collected by flower visitors, there will be less pollen left for pollination and fertilization. Therefore, there is competition for limited pollen resources between plants and bee pollinators. On the one hand, plants need to attract pollinators for pollination, and on the other hand, they must prevent bees from consuming and collecting too much pollen [44]. The toxic quinolizidine alkaloids in the pollen of Lupinus can strongly increase the mortality of some Osmiini bees, which only forage for pollen during a visit, and these detrimental effects were medicated by host–plant association [45]. The pollen of R. molle had a higher concentration of toxic rhodojaponin Ⅲ, and pollen toxicity in flowers may discourage pollen robbers (bees) from consuming too many pollen grains [46]. The pollen of the nine species of Ericaceae investigated in our study contained grayanotoxin I, grayanotoxin IX, andromedotoxin and asebotin. These toxic compounds in pollen may limit bumblebee and honeybee pollen grooming behavior. The five chemical compounds with the highest content in the pollen of the nine Ericaceae species in our study were kaempferol (flavonoids), quercetin (flavonoids), apigenin 7-o-glucoside (quinones), olean-12-ene-3,11-dione (triterpenes) and quercetin 7-rhamnoside (flavonoids). These flavonoids are important secondary metabolites produced by plants that serve multiple functions, including plant growth, development and protection against various stresses [47]. Kaempferol exhibits anticarcinogenic, anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, antifungal and antiprotozoal activities [48]. Kaempferol is essential for pollen germination and pollen tube growth and thus affects seed production in plants [49]. The interaction between these chemical substances in Ericaceae plants and their visitors requires continuous research in the future.

4.2. Comparison of Secondary Metabolite in Pollen and Other Tissues

Chemical dissimilarities between pollen and other tissues are widespread [4] (Rivest and Forrest, 2020). The pleiotropy hypothesis suggests that secondary compounds in pollen could be a pleiotropic consequence of the production of the compounds in other plant organs or tissues and is influenced by the concentration of defense compounds in nearby tissues or vascular fluids [50]. However, the qualitative composition of the secondary metabolites in pollen and anthers may differ considerably from that of other plant organs [43,51,52]. Rivest et al. [52] showed a positive relationship between alkaloid concentrations in the pollen and petals of Lupinus argenteus, and this proved that pollen defense compounds partly originate from spillover. However, the pollen and petals exhibited quantitatively (but not qualitatively) distinct alkaloid profiles, suggesting that plants can adjust pollen alkaloid composition independently from that of adjacent tissues. The diversity and relative contents of the secondary metabolites in the leaves, stems and petals of the nine Ericaceae species in our study were higher than those in the pollen. The chemical composition of the secondary metabolites of the pollen grains of the nine Ericaceae species differs considerably from that of other tissues. Although the five chemical compounds with the highest content in pollen were also detected in the stems, leaves and petals, the response value of most of these chemicals in the pollen was not significantly correlated with that in other tissues. These results indicated that pollen secondary metabolites were not simply a pleiotropic consequence of their presence in other tissues and plants may partially regulate the production or allocation of these metabolites in anthers and pollen [53,54].

Some studies have compared the secondary metabolites between pollen grains and nectar, which are the most important floral reward and showed that pollen had a greater variety of metabolites and significantly higher relative contents than nectar [5,43,46,55]. The pollen of Rhododendron molle had a higher concentration of toxic rhodojaponin Ⅲ than the petals and leaves, and this toxic compound was not detected in nectar [46]. The diversity and value of response intensity of the secondary metabolites in the pollen of the nine Ericaceae species in our study were also higher than those in nectar. Pollen plays two important roles in angiosperm reproduction, not only as a male gametophyte for plant reproduction but also as a reward that plants give to pollinators. The sole function of nectar is to reward the mutualists, making it unnecessary to possess the same level of chemical defense as pollen. Toxic compounds in pollen may discourage pollen robbers (bees) or less effective pollinators from taking the freely accessible pollen grains, while the toxin-free or toxin-less nectar rewards effective pollinators, promoting pollen transfer.

4.3. Different Pollination Behavior of Bees, Birds and Lepidoptera

The pollination behavior of bees, birds and Lepidoptera are different. According to a review of 53 studies that describe pollen theft from more than 80 plant species in almost 40 families, Hymenoptera and Apoidea (bees) animals are considered the most common pollen thieves, including Apis mellifera, Halictidae, Perdita spp., Bombus spp. and mixed bees [56]. For example, honeybees (Apis spp.) display remarkable flexibility in their manipulation of flowers, which could predispose them to pollen theft [57]. Given that bees are the most important group of flower visitors worldwide [58], it is likely that pollen theft is significantly more prevalent than what is currently reflected in the available literature. Birds and Lepidoptera visit flowers primarily for nectar and do not groom pollen [59]. Pollen grains that adhere to beaks or feathers can easily be deposited on receptive flowers during subsequent visits, resulting in minimal pollen loss during transfer [60].

According to a study of 13 Rhododendron species in the Eastern Himalayas region, bees (most species were bumblebees) often foraged nectar from Rhododendron flowers and facilitated pollen release by buzzing the anthers and sometimes deliberately grooming clusters and packing them into corbiculae. The pollen tetrads placed on the birds and Lepidoptera bodies were not seen to be removed. The birds and Lepidoptera did not regularly groom Rhododendron pollen [16]. Cai et al. [25] showed that bumblebees collected pollen grains of R. excellens on their legs and abdomens by vibrating their anthers. Viscin threads with aggregated pollen sometimes hung from bumblebees, which indicated that the pollen grains could be deposited on stigmas even without direct contact between bumblebees and sigma if these hanging viscin threads were captured by sticky stigmas. Honeybees usually forage the nectars flowing to the openings of the flowers. Hawkmoths usually forage nectar by entering the flowers and perching on the corolla, style or stamens and can carry hanging viscin threads with aggregated pollen. Feng et al. [46] showed that R. molle was pollinated by both butterflies and bumblebees, and butterflies did not differ from bumblebees in the number of pollen grains removed per visit but deposited more pollen grains on the stigma per visit. In our study, Enkianthus ruber, Pieris formosa, Rhododendron agastum, R. irroratum, R. virgatum and R. rubiginosum (bee-pollinated species) in our study contains higher contents of secondary metabolites (especially terpenoids compounds) in pollen grains than R. delavayi, R. decorum and R. excellens (species pollinated by bees, birds and Lepidoptera). Birds and Lepidoptera play an important role in reproductive success for R. delavayi, R. decorum and R. excellens, which usually visit flowers for nectar and do not groom and collect pollen grains. The plants with birds and Lepidoptera as important pollinators may not experience as much selection pressure to limit pollen loss, and the amount of secondary metabolites in their pollen may be less.

Pollinator differences may relate to the variation in floral traits. A study of 15 Rhododendron species in the Hengduan Mountains region revealed that Rhododendron species visited by birds had significantly larger flower opening diameters and floral tube depths than species primarily pollinated by insects [15]. Another study showed that bird- and Lepidoptera-pollinated Rhododendron species produced longer pollen-connecting threads, which connected more pollen grains than bee-pollinated Rhododendron species, and the results indicated that pollinators mediated selection of such pollen packaging strategies [16]. Plants with a high nectar volume, a low sugar concentration and a high sucrose-to-hexose ratio are mainly visited by birds [61,62,63].

An increasing amount of evidence indicates that pollination syndromes include not only morphological traits but also floral chemical traits [64,65,66]. Previous studies have shown that pollen nutritional content is a key element for understanding host–plant choices and their evolution among bees. The secondary metabolites in plant tissues, especially in pollen and nectar, may play an important role in plant–pollinator interactions and the coevolution of plants and insects. Another study showed that the high species diversity of Rhododendron in Asia is related to the wide altitudinal range and significant variations in annual precipitation in this region, and the adaptation of leaf functional traits in this genus has also contributed to species diversity [67]. Further research may explore the interaction between plant chemical traits, pollinator types and environmental factors over a wider geographical range and with more species.

5. Conclusions

Our results showed that the Ericaceae species varied significantly in their floral characteristics and nectar traits. The pollen of the Ericaceae species was rich in phenolics and terpenoids, especially flavonoids. Well-known toxic diterpene compounds (such as grayanotoxin, andromedotoxin and asebotin) were also detected in the pollen of some Ericaceae species in our study, and their response value was low. The five chemical compounds with the highest content in pollen were also detected in the stems, leaves and petals, and the response value of most of these chemicals in pollen was not significantly correlated with that in other tissues. Rhododendron species had a closer relationship with chemical traits in pollen compared to species from other genera of Ericaceae. The response value of total secondary metabolites in the pollen of species pollinated only by bees was higher than that of species pollinated by diverse animals (bees, birds and Lepidoptera). The interaction between chemical substances in pollen and pollinator types requires continuous research in the future.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/horticulturae10121262/s1. Table S1: The chemical compounds in Enkianthus, Pieris, Rhododendron species with chemical names, chemical formulas and chemical structure (mol. files) reported in related references.

Author Contributions

X.W., Y.Y. and X.T. designed the experiments; X.W. and J.W. performed the field experiments; X.W., J.W., S.W., Y.L. and H.X. analyzed the data; X.W., J.W., Y.Y. and X.T. wrote the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China (number 32360262; 31901208), Guizhou Provincial Program on Commercialization of Scientific and Technological Achievements (number [2022] 010); Water-Fertilizer Coupling and Biodiversity Restoration in Karst Rocky Desertification (number QianJiaoJi [2023] 004); Key Laboratory of Environment Friendly Management on Alpine Rhododendron Diseases and Pests of Institutions of Higher Learning in Guizhou Province (number [2022] 044).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article and supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We thank Yan Chen, Renxiu Yao and Xiaoqin Lv, master’s students at the College of Life Science, Guizhou Normal University, for their assistance in the field experiment; Sarah Corbet (University of Cambridge) for improving the English of the manuscript; and Yi Jin, Jing Tang (associate professor at Guizhou Normal University), Qiang Fang (associate professor at Henan University of Science and Technology), Rui Chen and Gaofeng Zhu (associate professor at Guizhou Medical University) for the data analysis. We thank the reviewers for their valuable comments.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Iason, G.; Dicke, M.; Hartley, S. The ecology of plant secondary metabolites: From genes to global processes (ecological reviews). Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 2013, 171, 774. [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal, A.A.; Espinosa Del Alba, L.; López-Goldar, X.; Hastings, A.P.; White, R.A.; Halitschke, R.; Dobler, S.; Petschenka, G.; Duplais, C. Functional evidence supports adaptive plant chemical defense along a geographical cline. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2205073119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salam, U.; Ullah, S.; Tang, Z.H.; Elateeq, A.A.; Khan, Y.; Khan, J.; Khan, A.; Ali, S. Plant metabolomics: An overview of the role of primary and secondary metabolites against different environmental stress factors. Life 2023, 13, 706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivest, S.; Forrest, J.R.K. Defence compounds in pollen: Why do they occur and how do they affect the ecology and evolution of bees? New Phytol. 2020, 225, 1053–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.Y.; Tang, J.; Wu, T.; Wu, D.; Huang, S.Q. Bumblebee rejection of toxic pollen facilitates pollen transfer. Curr. Biol. 2019, 29, 1401–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flamini, G.; Cioni, P.L.; Morelli, I. Use of solid phase micro-extraction as a sampling technique in the determination of volatiles emitted by flowers, isolated flower parts and pollen. J. Chromatogr. A 2003, 998, 229–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dübecke, A.; Beckh, G.; Lüllmann, C. Pyrrolizidine alkaloids in honey and bee pollen. Food Addit. Contam. Part A-Chem. Anal. Control Expo. Risk Assess. 2011, 28, 348–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De-Melo, A.A.M.; de Almeida-Muradian, L.B. Chemical composition of beepollen. In Bee Products—Chemical and Biological Properties; Alvarez-Suarez, J., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 221–259. [Google Scholar]

- Thorp, R.W. The collection of pollen by bees. Plant Syst. Evol. 2000, 222, 211–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, S.E.J.; Idrovo, M.E.P.; Arias, L.J.L.; Belmain, S.R.; Stevenson, P.C. Herbivore defence compounds occur in pollen and reduce bumblebee colony fitness. J. Chem. Ecol. 2014, 40, 878–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heiling, J.M.; Cook, D.D.; Lee, S.T.; Irwin, R.E. Pollen and vegetative secondary chemistry of three pollen-rewarding lupines. Am. J. Bot. 2019, 106, 643–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, L.S.; Fowler, A.E.; Malfi, R.L.; Anderson, P.R.; Coppinger, L.M.; Deneen, P.M.; Lopez, S.; Irwin, R.E.; Farrell, I.W.; Stevenson, P.C. Assessing chemical mechanisms underlying the effects of sunflower pollen on a gut pathogen in bumble bees. J. Chem. Ecol. 2020, 46, 649–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stevenson, P.C. For antagonists and mutualists: The paradox of insect toxic secondary metabolites in nectar and pollen. Phytochem. Rev. 2020, 19, 603–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, M.Y.; Fang, R.Z.; He, M.Y.; Hu, L.Z.; Yang, H.B.; Qin, H.N.; Min Tl Chamberlain, D.F.; Stevens, P.F.; Wallace, G.D. Ericaceae. Flora China 2005, 14, 242–517. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Z.H.; Song, Y.P.; Huang, S.Q. Evidence for passerine bird pollination in Rhododendron species. AoB PLANTS 2017, 9, plx062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.P.; Huang, Z.H.; Huang, S.Q. Pollen aggregation by viscin threads in Rhododendron varies with pollinator. New Phytologist 2019, 221, 1150–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, H.Q.; Feng, Y.F.; Rui, W.; Jiang, M.M.; Han, L. Analysis of flavonoids in Rhododendron mariae by UPLC/Q-TOF-MS. China J. Chin. Mater. Medica 2009, 34, 875–878, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Duan, S.G.; Hong, K.; Tang, M.; Tang, J.; Liu, L.X.; Gao, G.F.; Shen, Z.J.; Zhang, X.M.; Yi, Y. Untargeted metabolite profiling of petal blight in field-grown Rhododendron agastum using GC-TOF-MS and UHPLC-QTOF-MS/MS. Phytochemistry 2021, 184, 112655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, R.X.; Chen, Y.; Lv, X.Q.; Wang, J.H.; Yang, F.J.; Wang, X.Y. Altitude-related environmental factors shape the phenotypic characteristics and chemical profile of Rhododendron. Biodivers. Sci. 2022, 30, 22259, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiedeken, E.J.; Stout, J.C.; Stevenson, P.C.; Wright, G.A. Bumblebees are not deterred by ecologically relevant concentrations of nectar toxins. J. Exp. Biol. 2014, 217, 1620–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiedeken, E.J.; Egan, P.A.; Stevenson, P.C.; Wright, G.A.; Brown, M.J.F.; Power, E.F.; Farrell, I.; Matthews, S.M.; Stout, J.C. Nectar chemistry modulates the impact of an invasive plant on native pollinators. Funct. Ecol. 2016, 30, 885–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fattorini, R.; Egan, P.A.; Rosindell, J.; Farrell, I.W.; Stevenson, P.C. Grayanotoxin I variation across tissues and species of Rhododendron suggests pollinator-herbivore defence trade-offs. Phytochemistry 2023, 212, 113707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.L. Natural Hybridization Origin of Rhododendron agastum (Ericaceae) in Yunnan, China (Doctor Research). Ph.D. Thesis, Kunming Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Science, Kunming, China, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Huang. The pollination system and floral evolution of Genus Rhododendron (Ericaceae). Ph.D. Thesis, Wuhan University, Wuhan, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, B.; Peng, D.; Liu, C.; Tan, G. Neglecting nocturnal pollinators has long masked hawkmoth pollination in Rhododendron. Arthropod-Plant Interact. 2024, 18, 1135–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, W.Y.; Wu, Y.W.; Bai, T.; Xie, W.J.; Dong, Y.; Zhang, J.L. Breeding system and hybridization affinity of Rhododendron irroratum. Bull. Bot. Res. 2024, 44, 370–379. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, D.M.; Dong, X.; Wu, J.M.; Hu, L.Y.; Tang, M.; Wang, X.Y. Comparison of floral traits of three Rhododendron species in different habitats. Guihaia 2022, 42, 161–173, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Cádiz-Gurrea, M.D.; Fernández-Arroyo, S.; Joven, J.; Segura-Carretero, A. Comprehensive characterization by UHPLC-ESI-Q-TOF-MS from an Eryngium bourgatii extract and their antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities. Food Res. Int. 2013, 50, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Lv, B.; Li, P.; Ma, X.; Wang, T.; Zhou, Q.; Wang, X.; Gao, X. Bioactivity-integrated UPLC/Q-TOF-MS of Danhong injection to identify NF-κB inhibitors and anti-inflammatory targets based on endothelial cell culture and network pharmacology. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2015, 174, 270–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, L.; Shi, A.M.; Liu, H.Z.; Meruva, N.; Liu, L.; Hu, H.; Yang, Y.; Huang, C.; Li, P.; Wang, Q. Identification of chemical ingredients of peanut stems and leaves extracts using UPLC-QTOF-MS coupled with novel informatics UNIFI platform. J. Mass Spectrom. 2016, 51, 1157–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, L.X.; Yin, F.; Li, X.Y.; Fang, J.H.; Li, H.J.; Xu, X.H.; Xia, P.G.; Liang, Z.S.; Zhang, X.D. UPLC-Q-TOF-MSE Based Profiling of the Chemical Composition of Different Parts of Tetrastigma hemsleyanum. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2024, 19, 1934578X241239494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swartz, M.E. UPLC™: An introduction and review. J. Liq. Chromatogr. Relat. Technol. 2005, 28, 1253–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, D.M.; Hu, M.Y. Research advances in the research on Rhododendron Molle (Blume) G. Don. Nat. Prod. Res. Dev. 1995, 11, 109–113, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Dai, S.J.; Chen, R.Y.; Yu, D.Q. Studies on the flavonoid compounds of Rhododendron anthopogonoides. China J. Chin. Mater. Medica 2004, 29, 44–47, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Dai, S.J.; Yu, D.Q. Studies on the flavonoids in stem of Rhododendron anthopogonoide II. China J. Chin. Mater. Medica 2005, 30, 1830–1833, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.M.; Pan, Y.Y.; Li, R.T.; Li, H.Z. Study on Chemical Constituents of Pieris Formosa. J. Kunming Univ. Sci. Technol. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2011, 36, 56–63. [Google Scholar]

- Niu, C.S. Studies on the Chemical Constituents and Bioactivity from Sterns of Pieris jormosa and Studies on the Sesquiterpenes from the Roots of lllicium majus. Master’s Thesis, Chinese Academy of Medical Science & Peking Union Medical College, Beijing, China, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, N.; Zheng, G.J.; He, M.J.; Feng, Y.Y.; Liu, J.J.; Wang, M.C.; Zhang, H.Q.; Zhou, J.F.; Yao, G.M. Grayanane diterpenoids from the Leaves of Rhododendron auriculatum and their analgesic activities. J. Nat. Prod. 2019, 82, 1849–1860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.Q.; Ma, S.G.; Lin, M.B.; Hou, Q.; Ma, M.; Yu, S.S. Hydroxylated ethacrylic and tiglic acid derivatives from the stems and branches of Enkianthus chinensis and their potential anti-inflammatory activities. J. Nat. Prod. 2020, 83, 2867–2876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.Y.; Sun, Y.Y. The medicinal value of Rhododendron dauricuml. Q. For. By-Prod. Spec. China 2000, 2, 46. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.J.; Su, H.G.; Peng, X.R.; Bi, H.C.; Qiu, M.H. An updated review of the genus Rhododendron since 2010: Traditional uses, phytochemistry, and pharmacology. Phytochemistry 2024, 217, 113899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brochu, K.K.; Dyke, M.; Milano, N.J.; Petersen, J.D.; Danforth, B.N. Pollen defenses negatively impact foraging and fitness in a generalist bee (Bombus impatiens: Apidae). Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 3112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Feng, H.H.; Liu, Y.L.; Huang, S.Q. Lethal effects of tea-oil Camellia on honeybee larvae due to pollen toxicity. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunau, K.; Piorek, V.; Krohn, O.; Pacini, E. Just spines: Mechanical defense of malvaceous pollen against collection by corbiculate bees. Apidologie 2015, 46, 144–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivest, S.; Muralidhar, M.; Forrest, J.R.K. Pollen chemical and mechanical defences restrict host-plant use by bees. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2024, 291, 20232298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, H.H.; Lv, X.W.; Yang, X.C.; Huang, S.Q. High toxin concentration in pollen may deter collection by bees in butterfly-pollinated Rhododendron molle. Ann. Bot. 2024, 20, mcae047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dias, M.C.; Pinto, D.C.G.A.; Silva, A.M.S. Plant flavonoids: Chemical characteristics and biological activity. Molecules 2021, 26, 5377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Periferakis, A.; Periferakis, K.; Badarau, I.A.; Petran, E.M.; Popa, D.C.; Caruntu, A.; Costache, R.S.; Scheau, C.; Caruntu, C.; Costache, D.O. Kaempferol: Antimicrobial properties, sources, clinical, and traditional applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 15054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vogt, T.; Pollak, P.; Tarlyn, N.; Taylor, L.P. Pollination- or wound-induced kaempferol accumulation in Petunia stigmas enhances seed production. Plant Cell 1994, 6, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kessler, A.; Halitschke, R. Testing the potential for conflicting selection on floral chemical traits by pollinators and herbivores: Predictions and case study. Funct. Ecol. 2009, 23, 901–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritmejerytė, E.; Boughton, B.A.; Bayly, M.J.; Miller, R.E. Unique and highly specific cyanogenic glycoside localization in stigmatic cells and pollen in the genus Lomatia (Proteaceae). Ann. Bot. 2020, 126, 387–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivest, S.; Lee, S.T.; Cook, D.; Forrest, J.R.K. Consequences of pollen defense compounds for pollinators and antagonists in a pollen-rewarding plant. Ecology 2024, 105, e4306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Heiling, S.; Baldwin, I.T.; Gaquerel, E. Illuminating a plant’s tissue specific metabolic diversity using computational metabolomics and information theory. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, E7610–E7618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer-Young, E.C.; Tozkar, C.O.; Schwarz, R.S.; Chen, Y.; Irwin, R.E.; Adler, L.S.; Evans, J.D. Nectar and pollen phytochemicals stimulate honey bee (Hymenoptera: Apidae) immunity to viral infection. J. Econ. Entomol. 2017, 110, 1959–1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer-Young, E.C.; Farrell, I.W.; Adler, L.S.; Milano, N.J.; Stevenson, P.C. Chemistry of floral rewards: Intra- and interspecific variability of nectar and pollen secondary metabolites across taxa. Ecol. Monogr. 2019, 89, e01335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hargreaves, A.L.; Harder, L.D.; Johnson, S.D. Consumptive emasculation: The ecological and evolutionary consequences of pollen theft. Biol. Rev. 2009, 84, 259–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westerkamp, C. Honeybees are poor pollinators—why? Plant Syst. Evol. 1991, 177, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danforth, B.N.; Fang, J.; Sipes, S. Analysis of family-level relationships in bees (Hymenoptera: Apiformes) using 28S and two previously unexplored nuclear genes: CAD and RNA polymerase II. Mol. Phylogenetics Evol. 2006, 39, 358–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harder, L.D. Pollen-size comparisons among animal-pollinated angiosperms with different pollination characteristics. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 1998, 64, 513–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muchhala, N.; Thomson, J.D. Fur versus feathers: Pollen delivery by bats and hummingbirds and consequences for pollen production. Am. Nat. 2010, 175, 717–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, P.; Castellanos, M.C.; Wolfe, A.D.; Thomson, J.D. Shifts between bee bird pollination in Penstemons. In Plant-Pollinator Interactions: From Specialization to Generalization; Waser, N.M., Ollerton, J., Eds.; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2006; pp. 47–68. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, Q.; Chen, Y.Z.; Huang, S.Q. Generalist passerine pollination of a winter-flowering fruit tree in central China. Ann. Bot. 2012, 109, 379–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, S.G.; Huang, Z.H.; Chen, Z.B.; Huang, S.Q. Nectar properties and the role of sunbirds as pollinators of the golden-flowered tea (Camellia petelotii). Am. J. Bot. 2017, 104, 468–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shuttleworth, A.; Johnson, S.D. The importance of scent and nectar filters in a specialized wasp-pollination system. Funct. Ecol. 2009, 23, 931–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiner, C.N.; Hilpert, A.; Werner, M.; Linsenmair, K.E.; Bluthgen, N. Pollen amino acids and flower specialisation in solitary bees. Apidologie 2010, 41, 476–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burger, H.; Buttala, S.; Koch, H.; Ayasse, M.; Johnson, S.D.; Stevenson, P.C. Nectar cardenolides and floral volatiles mediate a specialized wasp pollination system. J. Exp. Biol. 2024, 227, jeb246156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, X.M.; Yang, M.Q.; Li, C.L.; Huang, S.X.; Jin, W.T.; Shen, T.T.; Wang, F.; Li, X.H.; Yoichi, W.; Zhang, L.H.; et al. Spatiotemporal evolution of the global species diversity of Rhododendron. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2022, 39, msab314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).