Abstract

As one of the few carotenoid-producing microorganisms, Rhodotorula mucilaginosa remains underexplored for its antioxidant activity. This study investigated the effects of R. mucilaginosa JAASSRY on D-galactose-induced aging mice. The high-dose JAASSRY (HR) significantly increased body weight by 9.89% compared to the model group (AM), while reducing organ indices of the spleen, liver, kidneys, and brain (p < 0.01). Compared with the AM group, the HR group exhibited increased serum activities of SOD (20.26%), GSH-Px (9.03%), and CAT (133.01%), with a 24.87% decrease in MDA level. In brain tissue, SOD, GSH-Px, and CAT activities increased by 79.49%, 8.45%, and 60.23%, respectively, while MDA decreased by 8.29%. R. mucilaginosa JAASSRY also dose-dependently alleviated structural damage in the hippocampus and spleen and improved motor strength and learning-memory capacity. Furthermore, R. mucilaginosa JAASSRY increased the abundance of Lactobacillus and reduced Proteobacteria, Helicobacter, and Oscillospira, while enhancing antioxidant capacity by modulating nucleotide, lipid, and carbohydrate metabolism. Lactobacillus and Pediococcus were positively correlated with memory latency and CAT/SOD activities (p < 0.05), whereas Actinormyces and Dehalobacterium showed negative correlations. Notably, HR performed comparably or superiorly to β-carotene in improving cerebral oxidative stress and beneficial microbiota, suggesting its potential in neuroprotection and gut–brain axis regulation. In conclusion, R. mucilaginosa JAASSRY mitigates aging-related oxidative damage and behavioral deficits by modulating gut microbiota structure and function, demonstrating its promise as a β-carotene alternative in animal husbandry and functional foods.

1. Introduction

Rhodotorula mucilaginosa, a basidiomycetous yeast of the genus Rhodotorula, is one of the few microorganisms known to produce carotenoids [1,2,3]. In recent years, it has attracted considerable attention due to its rich content of bioactive compounds, particularly carotenoids. Both the whole yeast cells and their intracellular extracts have demonstrated an ability to scavenge free radicals, exhibit antioxidant activity, and alleviate oxidative damage [4]. Additionally, studies have confirmed that R. mucilaginosa exhibits high in vitro activity and displays antagonistic effects against various pathogenic bacteria [5]. However, current research on Rhodotorula yeasts remains largely focused on aquaculture applications—for example, in enhancing growth performance and body colouration in aquatic species [6,7]. In contrast, the probiotic mechanisms of R. mucilaginosa in mammalian aging models remain poorly investigated.

The antioxidant properties of carotenoids are widely acknowledged by consumers. One study demonstrated that flake food containing Orange Sweet Potato and Red Rice, with a total β-carotene content of 25.77 mg/L, exhibited 85% antioxidant activity, categorizing it as potent; moreover, flakes with different formulation ratios were well accepted in terms of sensory attributes [8]. The value of R. mucilaginosa biomass lies primarily in its rich profile of diverse carotenoids, such as β-carotene [9], lycopene [10], and torularhodin [11]. These pigments do not exist in isolation but form a natural complex antioxidant system. It is precisely the existence of this system that makes the interaction mechanism between R. mucilaginosa and their hosts potentially exhibit unique complexity. Currently, there is a lack of direct experimental evidence regarding whether R. mucilaginosa can modulate systemic oxidative stress and thereby improve cognitive function via the “gut–brain” axis. The absence of insights into this key mechanism hinders the broader application of R. mucilaginosa in the feed and food industries.

D-galactose, a commonly used agent for inducing aging, is widely employed in studies investigating senescence mechanisms and screening anti-aging compounds. Specifically, D-galactose induces oxidative stress by generating excessive free radicals [12], thereby damaging cell membranes, proteins, and DNA structures, which ultimately leads to cellular dysfunction and apoptosis [13,14]. Furthermore, D-galactose can trigger mitochondrial dysfunction, disrupting cellular energy metabolism [15] and accelerating the cellular senescence process [16]. Thus, within a D-galactose-induced aging model—particularly when combined with other pharmaceutical interventions—the assessment of oxidative damage in animal organs serves as an effective approach for evaluating the anti-aging efficacy of such interventions [17,18].

Based on the core mechanism of D-galactose-induced aging through oxidative stress, this study selected four key indicators for systematic assessment: superoxide dismutase (SOD), glutathione peroxidase (GSH-Px), catalase (CAT), and malondialdehyde (MDA). In terms of antioxidant defense, SOD, GSH-Px, and CAT form an interconnected network of intracellular antioxidant enzymes. SOD serves as the primary defense against oxidative damage by catalyzing the dismutation of superoxide anion radicals into hydrogen peroxide [19]. CAT then directly decomposes hydrogen peroxide into water [20], while GSH-Px reduces lipid peroxides, thereby preventing their conversion into toxic aldehydes [21]. The activities of these three enzymes collectively reflect the organism’s overall capacity to eliminate free radicals and maintain oxidative balance. For the assessment of oxidative damage, MDA—as a terminal metabolite of lipid peroxidation chain reactions—serves as a direct indicator of the extent of damage to polyunsaturated fatty acids caused by free radicals [22]. Measuring tissue MDA levels provides an objective quantification of structural damage to biomembranes induced by D-galactose. This multi-faceted and cross-validated detection strategy not only accurately evaluates the severity of D-galactose-induced oxidative stress but also comprehensively reveals the regulatory effects of drug interventions on oxidative balance in the aging model, covering both antioxidant capacity and oxidative damage dimensions.

This study employed a D-galactose-induced aging mouse model, using β-carotene as a positive control. We systematically investigated the protective effects of different concentrations of R. mucilaginosa JAASSRY on oxidative stress, behavioral performance, and gut microbiota in aging mice. The findings aim to establish a theoretical foundation for developing R. mucilaginosa—which is rich in natural carotenoids and other compounds—into novel antioxidant microecological agents for anti-aging applications. Furthermore, this work lays the groundwork for creating innovative feed and food additives that could serve as potential alternatives to β-carotene.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals and Materials

Specific pathogen-free (SPF) male Kunming (KM) mice were obtained from Liaoning Changsheng Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Liaoyang, Liaoning, China, Animal Production License No. SCXK (Liao) 2020-0001).

The R. mucilaginosa JAASSRY strain was isolated and identified by the Food Microbiology Team at the Institute of Agro-product Processing, Jilin Academy of Agricultural Sciences (Changchun, Jilin Province, China). This strain is deposited in the China General Microbiological Culture Collection Center (CGMCC, Beijing, China) with the accession number CGMCC No. 22900.

2.2. Strain Activation

A single colony was inoculated into a modified LB medium (containing 5 g/L yeast extract, 10 g/L peptone, 10 g/L NaCl, 0.8 mL/L soybean oil, and 3 g/L glucose) and cultured at 30 °C with shaking at 180 rpm for 48 h. A 5% (v/v) inoculum of the seed culture was transferred into 200 mL of fresh medium and cultured for another 48 h under the same conditions. The resulting bacterial suspension had a viable count of 1.2 × 108 CFU/mL and a carotenoid content of 325.85 ± 11.78 μg/g.

2.3. Experimental Animal Grouping Design

All animal experiments were performed in compliance with the guidelines approved by the Laboratory Animal Management and Ethics Committee of the Institute of Agro-food Technology, Jilin Academy of Agricultural Sciences (NO. LAMECJAAS-2025-010-04). A total of thirty healthy male SPF Kunming (KM) mice (approximately 18–20 g each) were used in the study. The animals were housed under a standard light-dark cycle with the ambient temperature maintained at (23 ± 1) °C. All mice had free access to water and a standard maintenance diet. Following a one-week acclimatization period, the formal experiment was initiated.

Following the acclimatization period, KM mice were randomly assigned into five groups (n = 6) for a 42-day experiment: (1) Control group (CK): administered a daily intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of 200 mg/kg physiological saline along with an oral gavage of 0.2 mL physiological saline. (2) Model group (AM): received a daily i.p. injection of 200 mg/kg D-galactose (Shanghai Yuanye Bio-Technology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) together with an oral gavage of 0.2 mL physiological saline [23]. The remaining three groups were subjected to D-galactose modeling and concurrently received the following oral treatments: (3) β-carotene group (BC): given a daily oral gavage of 200 mg/kg β-carotene (Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) [24]. (4) Low-dose R. mucilaginosa JAASSRY group (LR, viable bacterial count: 1.0 × 106 CFU/mL) and (5) High-dose R. mucilaginosa JAASSRY group (HR, viable bacterial count: 1.0 × 1010 CFU/mL): administered a daily oral gavage of 0.2 mL of the respective R. mucilaginosa JAASSRY suspension. The cellular carotenoid contents in the LR and HR groups were 243.55 ± 8.54 μg/g and 387.41 ± 10.25 μg/g, respectively.

Dietary intake, mental state, fur condition, and body weight were observed and recorded daily throughout the experiment.

2.4. Behavioral Tests

2.4.1. Tail Suspension Test

The apparatus consisted of an experimental chamber (35 cm × 60 cm) with a black background and a hook at the top. During the test, the mouse’s tail was fixed with adhesive tape and suspended using a cotton rope. The mouse was suspended for 6 min, and the total immobility time during the last 5 min was recorded. After each test, the chamber was cleaned of feces, urine, and fur, and any odor influence was removed using a 75% (v/v) ethanol solution.

2.4.2. Grip Strength Measurement

The mouse was placed on the grid of the grip strength meter and induced to grip the mesh with its forelimbs. The time until the mouse lost its grip under traction and the grip force at the moment of release were recorded. Multiple measurements were taken, and the average value was calculated.

Grip impulse (g·s) = Grip force (g) × Grip duration (s)

2.4.3. Step-Down Test

The step-down test consisted of three phases: adaptation, learning, and memory. Mice were first allowed to adapt to the reaction chamber for 3 min. An alternating current shock (38 V) was then delivered. After receiving the shock, the mouse’s correct response was to escape by jumping onto the platform. If the mouse jumped down from the platform, it was considered an error. A 5 min training session was conducted following this method. For each mouse, the latency to jump onto the platform after the shock and the number of errors (receiving shocks on the grid) were recorded as the training score. If a mouse did not jump down from the platform within 5 min, the latency was recorded as 300 s. A test was conducted 24 h later, where the mouse was placed gently on the platform, and the latency of the first descent and the number of errors within 5 min were recorded as the learning score. The test was repeated one week later to assess the memory score.

2.5. Animal Tissue Collection

After the final administration, mice were fasted for twelve hours with free access to water, then weighed, and blood samples were collected via orbital puncture. Following euthanasia, brain, liver, kidney, and spleen tissues were rapidly dissected on ice. These tissues were flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen for subsequent organ index calculation and further analysis. Fecal samples were aseptically collected and stored at −80 °C. The organ index was calculated using the following formula:

Organ index (%) = [Organ weight (g)/Body weight (g)] × 100%

2.6. H&E Staining

Spleen and brain tissues were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (pH 7.4), dehydrated through a graded ethanol series, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned at 5 μm thickness. Sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), and the tissue morphology was observed under a light microscope.

2.7. Determination of Antioxidant Indices

Blood samples collected from the mandibular angle/retro-orbital plexus were placed in a 37 °C incubator for 2 h. Serum was separated by centrifugation at 3000 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C. The activities of superoxide dismutase (SOD), malondialdehyde (MDA), catalase (CAT), and glutathione peroxidase (GSH-Px) in the serum were determined according to the instructions of the commercial kits (Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, Nanjing, China).

Brain tissues were homogenized in ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (1:9, w/v) and centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 15 min at 4 °C. The resulting supernatant was collected for the analysis of the four oxidative stress markers.

2.8. Gut Microbiota Analysis

Mouse fecal samples, stored in sterile centrifuge tubes, were sent to Shanghai Personalbio Biotechnology Co., Ltd. for 16S rRNA sequencing analysis. The hypervariable V3-V4 regions of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene were amplified using PCR with the universal bacterial primers 341F (5′-CCTAYGGGRBGCASCAG-3′) and 806R (5′-GGACTACNNGGGTATCTAAT-3′). Purified amplicons were used to construct libraries on the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) following standard protocols. Raw sequencing data in fastq format were processed using the QIIME2 (version 2019.4) pipeline, including quality filtering, removal of duplicate sequences, and clustering into operational taxonomic units (OTUs) at a 97% similarity threshold, while singletons (OTUs appearing only once across all samples) were removed. Species annotation was performed based on the Greengenes database (v13.8). For further analysis, alpha and beta diversity metrics were calculated based on OTU relative abundance. Additionally, R software was used for cluster analysis and comparison of species composition, community structure, population abundance, and microbial diversity indices of the mouse gut microbiota. Principal component analysis (PCA) was performed using the Bray–Curtis distance algorithm. Finally, we employed the Random Forest algorithm (via the classify-samples-ncv function in q2-sample-classifier) to identify the most representative differential microbial taxa from the phylum to genus level between groups.

2.9. Statistical Analysis

All experimental data (including three parallel datasets per group) were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics 27 software. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare mean values among groups, followed by the Least Significant Difference (LSD) test for multiple comparisons. Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Effects of R. mucilaginosa JAASSRY on Body Weight and Organ Indices in Aging Mice

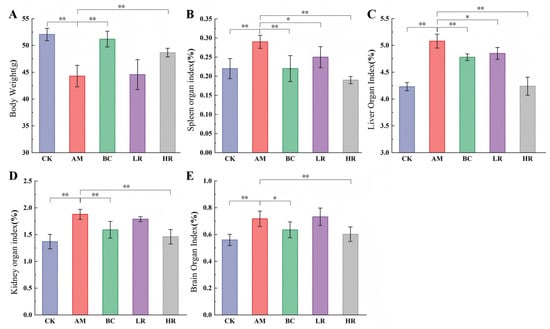

In this study, body weight and major organ (liver, spleen, kidney, and brain) indices were measured to evaluate the systemic effects of R. mucilaginosa JAASSRY on overall growth status and organ atrophy or abnormal enlargement in aging mice, thereby elucidating its potential protective role against metabolic decline and organ dysfunction during aging. Compared with the CK, mice in the AM group exhibited a significant reduction in body weight by 14.93% (p < 0.01). Relative to the AM group, intervention with either high-dose R. mucilaginosa JAASSRY or β-carotene significantly increased body weight by 9.89% and 15.58%, respectively (p < 0.01) (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Effects of R. mucilaginosa JAASSRY on Body Weight and Organ Indices in Aging Mice (A) Body weight of mice. (B) Spleen organ index. (C) Liver organ index. (D) Kidney organ index. (E) Brain organ index. (CK: Control group, AM: Model group, BC: β-carotene group, LR: Low-dose R. mucilaginosa JAASSRY group, HR: High-dose R. mucilaginosa JAASSRY group. Compared with the AM group, * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01).

Compared with the CK, the AM group showed significantly increased organ indices for the liver, spleen, kidney, and brain by 20.09%, 31.81%, 37.23%, and 28.13%, respectively (p < 0.01). Both high-dose R. mucilaginosa JAASSRY and β-carotene interventions comprehensively reversed these alterations. Notably, the HR group significantly reduced the indices of the liver, spleen, kidney, and brain by 16.54%, 34.48%, 22.34%, and 16.03%, respectively (p < 0.01). The low-dose R. mucilaginosa JAASSRY also led to significant improvements in the spleen and liver indices (p < 0.05) (Figure 1B–E). These results indicate that the intervention effect of the high-dose R. mucilaginosa JAASSRY bacterial suspension is comparable to that of β-carotene and may even exert superior regulatory effects on organs such as the liver and kidney.

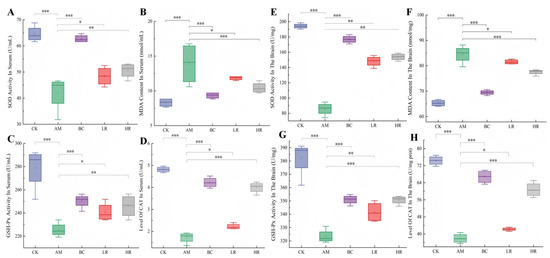

3.2. Effects of R. mucilaginosa JAASSRY on Serum and Cerebral Oxidative Stress Indicators in Aging Mice

The activities of SOD, GSH-Px, and CAT as well as the content of MDA were measured in serum and cerebral tissue to systematically evaluate the effects of R. mucilaginosa JAASSRY on antioxidant defense capacity and lipid peroxidation damage in aging mice, thereby elucidating its potential role in mitigating age-related oxidative stress and its dose–response relationship. In both serum and brain tissues, the activities of SOD, GSH-Px, and CAT in the AM group were significantly lower than those in the CK (p < 0.05), whereas the MDA content was significantly increased (p < 0.05). Compared with the AM group, the HR group demonstrated significant increases in serum SOD, GSH-Px, and CAT activities by 20.26%, 9.03%, and 133.01%, respectively, accompanied by a 24.87% reduction in serum MDA content. In brain tissue, the activities of these three antioxidant enzymes were significantly elevated by 79.49%, 8.45%, and 60.23%, respectively, while the MDA level was significantly reduced by 8.29% (p < 0.05; Figure 2). These findings suggest that R. mucilaginosa JAASSRY can dose-dependently alleviate systemic oxidative damage in aging mice, with the ameliorative effect of the high-dose formulation being comparable to that of β-carotene.

Figure 2.

Effects of R. mucilaginosa JAASSRY on Serum and Cerebral Oxidative Stress Indicators in Aging Mice (A–D) Serum SOD activity, MDA level, GSH-Px activity, and CAT level. (E–H) Brain SOD activity, MDA level, GSH-Px activity, and CAT level. (CK: Control group, AM: Model group, BC: β-carotene group, LR: Low-dose R. mucilaginosa JAASSRY group, HR: High-dose R. mucilaginosa JAASSRY group. Compared with the AM group, * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001).

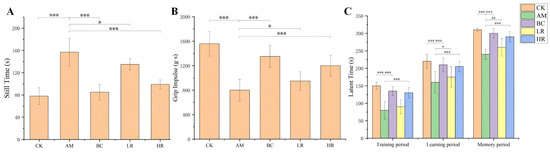

3.3. Effects of R. mucilaginosa JAASSRY on Behavioral Performance in Aging Mice

Behavioral indices, including immobility time in the tail suspension test, grip impulse, and step-down latencies during training, learning, and memory phases, were employed to comprehensively evaluate the effects of R. mucilaginosa JAASSRY on motor capacity, spontaneous activity, and learning-memory function in aging mice, thereby systematically elucidating its intervention effects on age-related neurobehavioral degenerative changes [25]. Relative to the CK, mice in the AM group exhibited a 101.28% significant increase in immobility time in the tail suspension test (p < 0.01) and a 48.65% significant reduction in grip impulse (p < 0.01). Compared with the AM group, interventions with either R. mucilaginosa JAASSRY or β-carotene significantly ameliorated these behavioral deficits (p < 0.05). Notably, the HR group showed a 36.94% significant decrease in immobility time and a 50% significant increase in grip impulse (p < 0.05) (Figure 3A,B).

Figure 3.

(A) Immobility time in the tail suspension test. (B) Grip impulse. (C) Step-down latency. (CK: Control group, AM: Model group, BC: β-carotene group, LR: Low-dose R. mucilaginosa JAASSRY group, HR: High-dose R. mucilaginosa JAASSRY group. Compared with the AM group, * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001).

In the step-down test, the AM group displayed significantly shorter latencies during the training, learning, and memory phases—by 46.67%, 27.27%, and 22.58%, respectively—compared to the CK (p < 0.01). In contrast, both the HR and BC groups demonstrated significantly prolonged step-down latencies across all three phases relative to the AM group (p < 0.01) (Figure 3C). These results collectively demonstrate that R. mucilaginosa JAASSRY intervention effectively enhanced muscle strength and spontaneous activity, while also markedly improving learning and memory capacities in aging mice.

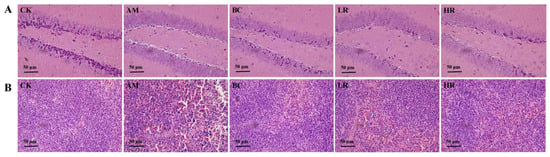

3.4. Effects of R. mucilaginosa JAASSRY on Histopathological Structure in Aging Mice

Histopathological examination of hippocampal and splenic tissues was performed to evaluate the ameliorative effects of R. mucilaginosa JAASSRY on microstructural damage in key organs (the nervous system and immune organ) of aging mice, thereby revealing its potential protective role against age-related degenerative alterations at the histomorphological level [26]. Compared with the CK, hippocampal tissue in the AM group exhibited neuronal atrophy and vacuolation, while splenic tissue showed structural damage characterized by cellular atrophy or swelling with widened intercellular spaces. Both R. mucilaginosa JAASSRY and β-carotene interventions effectively mitigated these histopathological injuries. Notably, the restorative effect observed in the HR group was comparable to that achieved by β-carotene (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Effects of R. mucilaginosa JAASSRY on Histopathological Structure in Aging Mice (A) Hippocampal tissue H&E-stained section of mice. (B) Splenic tissue H&E-stained section of mice. (CK: Control group, AM: Model group, BC: β-carotene group, LR: Low-dose R. mucilaginosa JAASSRY group, HR: High-dose R. mucilaginosa JAASSRY group).

3.5. Effects of R. mucilaginosa JAASSRY on the Structure and Function of Gut Microbiota in Aging Mice

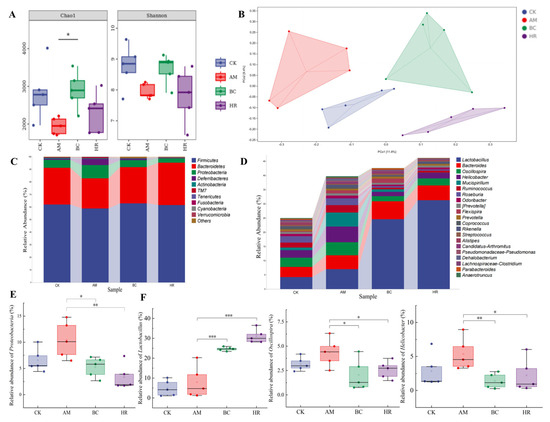

By systematically analyzing the α-diversity (Chao1 and Shannon indices), β-diversity, and structural characteristics at the phylum and genus levels of the gut microbiota, this study aimed to elucidate the core mechanisms by which high-dose R. mucilaginosa JAASSRY modulates intestinal microecological homeostasis in aging mice from the gut-body axis perspective, and to clarify the integrated biological pathway through which it enhances systemic antioxidant defense and alleviates age-related oxidative damage via multi-target synergistic actions by remodeling the probiotic/pathogen balance and restoring intestinal barrier function and metabolic activity [27].

Based on preliminary experimental data, the high-dose R. mucilaginosa JAASSRY demonstrated superior antioxidant capacity. Therefore, we further investigated the impact of the HR group on the structure and function of the gut microbiota in aging mice.

Alpha diversity was assessed using the Chao1 index for species richness and the Shannon index for community diversity. The Chao1 index was significantly lower in the AM group than in the CK. Following intervention with high-dose R. mucilaginosa JAASSRY and β-carotene, the Chao1 index increased significantly by 48.7% (p < 0.05) and 18.2% (p > 0.05), respectively. The Shannon index also exhibited a similar improving trend (Figure 5A). Beta diversity analysis revealed a clear separation among groups. Both the HR and BC groups were distanced from the AM group and clustered closer to the CK, indicating a beneficial modulatory effect of JAASSRY on microbial community structure (Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

(A) Alpha diversity analysis (Chao1 and Shannon index). (B) Beta diversity principal coordinates analysis (PCoA) based on Bray–Curtis distance. (C) Relative abundance of microbiota at the phylum level. (D) Relative abundance of microbiota at the genus level. Relative abundance of Proteobacteria (E) Lactobacillus, Oscillospira, and Helicobacter (F) (CK: Control group, AM: Model group, BC: β-carotene group, HR: High-dose R. mucilaginosa JAASSRY group. Compared with the AM group, * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001).

At the phylum level, the relative abundance of Proteobacteria in the AM group was significantly higher than that in the CK (p < 0.05). The relative abundances of Proteobacteria in both the BC and HR groups were significantly lower than that in the AM group (p < 0.05) (Figure 5C,E).

At the genus level, the abundances of Oscillospira, Helicobacter, and Mucispirillum were abnormally elevated in the AM group. Compared with the AM group, intervention with high-dose R. mucilaginosa JAASSRY and β-carotene significantly increased the relative abundance of Lactobacillus (p < 0.01). In contrast, the relative abundances of Oscillospira and Helicobacter were significantly reduced in both the BC and HR groups (p < 0.05) (Figure 5D,F).

These results indicate that high-dose R. mucilaginosa JAASSRY not only produces effects comparable to β-carotene in ameliorating tissue damage and oxidative stress but also exhibits similar efficacy in modulating gut microbiota structure. This suggests the potential of R. mucilaginosa JAASSRY as a functional alternative to β-carotene.

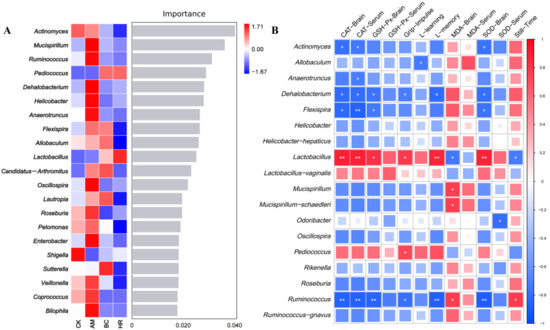

3.6. Correlation Analysis Between Gut Microbiota Changes and Antioxidant Indicators

By integrating Random Forest model screening and Spearman correlation analysis, this study systematically dissected the dynamic changes in key signature bacterial genera of the gut microbiota in aging mice following high-dose R. mucilaginosa JAASSRY intervention, as well as the multi-dimensional association network between these changes and multi-tissue redox homeostasis as well as higher-order neurobehavioral functions. This work aimed to elucidate, from a cross-system interaction perspective of the “microbiome–oxidative stress–neurobehavior” axis, the holistic process through which this strain activates endogenous antioxidant defenses and reverses aging-related oxidative damage and behavioral decline by precisely modulating the structure of the intestinal microecology [28].

Random Forest model analysis identified eight high-abundance genera that best characterized the microbiota structure in the AM group: Mucispirillum, Ruminococcus, Dehalobacterium, Helicobacter, Anaerotruncus, Oscillospira, Enterobacter, and Bilophila. The abundances of these genera were substantially reduced in the HR group (ranging from 52.7% to 100%). In comparison, the regulatory trend of these genera in the BC group was similar to that in the HR group, with the exceptions of Flexispira and Allobaculum. Notably, the abundances of Pediococcus and Lactobacillus, which were low in the CK and AM groups, were markedly upregulated in both the BC and HR groups, further confirming the similar regulatory effect of R. mucilaginosa JAASSRY and β-carotene on the microbiota. The two most abundant genera best representing the microbiota structure in the HR group were Pediococcus and Lactobacillus (Figure 6A).

Figure 6.

(A) Random forest model analysis of marker genus. Importance on the right side indicates that from top to bottom species are of decreasing importance to the model, and it can be assumed that these genus at the top of the importance scale are marker genus for differences between groups. (B) Spearman correlation analysis between gut microbiota and indicators of oxidative stress and behavioral performance. (CK: Control group, AM: Model group, BC: β-carotene group, HR: High-dose R. mucilaginosa JAASSRY group. Compared with the AM group, * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01).

To assess the potential association between alterations in the gut microbiota structure and the oxidative stress levels as well as behavioral performance in aging mice, we performed a correlation analysis between microbiota abundance and physiological indicators in the AM and HR groups. The results showed that Lactobacillus was significantly positively correlated with the latency in the memory phase, the CAT and SOD activities in brain, and the CAT activity in serum (p < 0.01). It was also significantly positively correlated with grip impulse and the GSH-Px activity in brain (p < 0.05), while negatively correlated with immobility time and the MDA level in brain (p < 0.05). In contrast, Actinormyces, Dehalobacterium, Flexispira, and Ruminococcus exhibited opposite correlations with these indicators. Furthermore, Anaerotruncus and Odoribacter were negatively correlated with the CAT and SOD activities in serum, respectively (p < 0.05). Allobaculum was negatively correlated with the latency in the learning phase (p < 0.05). Mucispirillum and Mucispirillum_schaedleri were positively correlated with the MDA level of brain (p < 0.05). Pediococcus was positively correlated with grip impulse (p < 0.05) (Figure 6B). These findings indicated that the structural changes in the gut microbiota modulated by high-dose R. mucilaginosa JAASSRY effectively improve the oxidative stress levels and behavioral performance in aging mice.

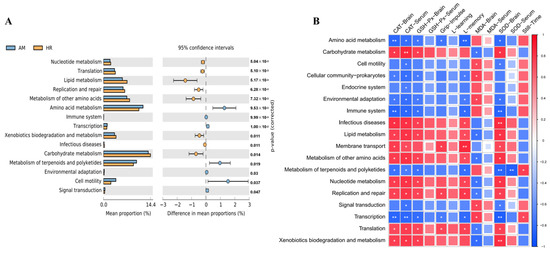

3.7. Effects of R. mucilaginosa JAASSRY on Metabolic Function of Gut Microbiota in Aging Mice

Functional prediction of gut microbiota metabolic pathways using PICRUSt2 and correlation analysis with oxidative stress indicators and behavioral parameters were performed to systematically elucidate the potential mechanism by which high-dose R. mucilaginosa JAASSRY influences systemic and cerebral oxidative stress status in aging mice through modulation of gut microbial metabolism, thereby alleviating aging-related damage [29].

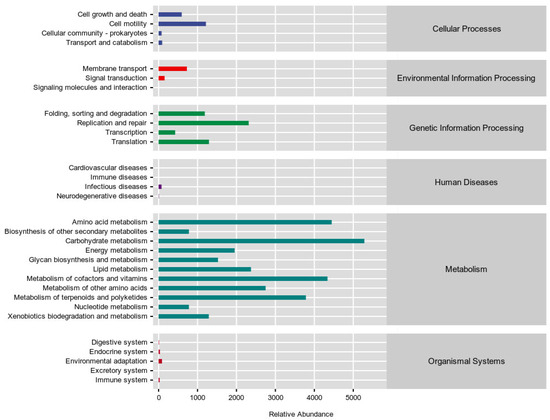

PICRUSt2 was employed to predict the functional potential of the gut microbiota based on the abundance of marker gene sequences in fecal samples. While the overall gene expression levels in primary signaling pathways were similar between the AM and HR groups (Figure A1), significant alterations were observed in secondary signaling pathways. Compared with the AM group, the HR group exhibited increased microbial gene abundances associated with nucleotide metabolism, lipid metabolism, and carbohydrate metabolism (Figure 7A).

Figure 7.

Effects of R. mucilaginosa JAASSRY on Metabolic Function of Gut Microbiota in Aging Mice (A) Metabolic pathways showed significant differences in functional gene expression abundance in the AM group vs. the HR group. (B) Spearman correlation analysis between metabolic pathways and indicators of oxidative stress and behavioral performance. (AM: Model group, HR: High-dose R. mucilaginosa JAASSRY group. Compared with the AM group, * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01).

Spearman correlation analysis was further performed to explore the relationships between microbial metabolic pathways and physiological indicators (Figure 7B). Pathways such as nucleotide, lipid, and carbohydrate metabolism showed positive correlations with serum CAT activity, brain CAT, GSH-Px, and SOD activities, as well as memory phase latency, whereas they were negatively correlated with brain MDA levels. In contrast, metabolic pathways including amino acid metabolism, environmental adaptation, and transcription demonstrated opposite correlation trends with these indicators.

These findings suggest that high-dose R. mucilaginosa JAASSRY may modulate systemic and cerebral oxidative stress by regulating core metabolic functions—such as nutrient metabolism and transcriptional activity—in the gut microbiota, thereby ultimately alleviating oxidative damage and reducing the degree of aging in mice.

4. Discussion

Rhodotorula mucilaginosa is one of the limited number of microorganisms known to be capable of producing carotenoids. For years, it has been utilized in aquaculture and animal husbandry to enhance production yield, improve disease resistance in fish and shrimp, and intensify the coloration of aquatic products. However, its potential health benefits for mammals and humans remain largely unexplored. In this study, the self-screened strain R. mucilaginosa JAASSRY was used to intervene in the D-galactose-induced aging mice, and its effects on organ indices, behavioral performance, oxidative stress levels, as well as the structure and function of the intestinal microbiota were systematically investigated. The results provided important evidence supporting its potential as a natural supplement or an alternative to β-carotene.

Compared with the CK, the AM group exhibited significant alterations in hippocampal histology, characterized by a progression from an originally orderly and regular cellular arrangement to conditions marked by neuronal atrophy and enlarged intercellular spaces. Following intervention with a specific concentration of R. mucilaginosa JAASSRY, the hippocampal tissue structure showed varying degrees of recovery, indicating its potential to ameliorate atrophy and functional decline in the hippocampus of aging mice [30].

In the AM group, characteristic alterations were observed in four key oxidative stress indicators in both serum and brain tissue: the activities of SOD, GSH-Px, and CAT were significantly suppressed, while MDA levels were markedly elevated, consistent with previous findings by Hu et al. [31]. These four parameters collectively constitute a core system for assessing systemic oxidative stress status. SOD serves as the primary defense against superoxide anion radicals, and its decreased activity directly impairs the cellular capacity for radical clearance [32]. GSH-Px plays an essential role in hydrogen peroxide metabolism, and its reduction can lead to the accumulation of hydroxyl radicals [33]. CAT, a key component of the hydrogen peroxide detoxification system, contributes to oxidative damage cascades when its activity is inadequate [34]. Meanwhile, MDA, as a terminal product of lipid peroxidation, reflects the extent of damage to cellular membranes when its content rises [35]. Notably, intervention with R. mucilaginosa JAASSRY effectively counteracted these changes in aging mice. In particular, under high-dose conditions, its efficacy in enhancing SOD, CAT, and GSH-Px activities in both serum and brain tissue was comparable to that of β-carotene. Simultaneously, this change was accompanied by a decrease in MDA levels. This coordinated shift indicates that the strain not only enhanced the organism’s antioxidant capacity but also effectively translated this enhancement into tangible suppression of oxidative damage. To explain this significant upregulation of enzyme activities, we propose the following two mechanisms. First, direct induction of the host’s endogenous antioxidant pathways: the carotenoids and other bioactive components abundantly present in R. mucilaginosa may act as activators of the Nrf2 signaling pathway [36]. Nrf2 is a key transcription factor that regulates a suite of antioxidant response elements, including the synthesis of SOD, CAT, and GSH-Px [37]. Second, systemic modulation through the gut microbiota–systemic metabolism axis: this study has confirmed that R. mucilaginosa significantly alters the structure of the gut microbiota. The improvement of gut microbiota is closely associated with an increase in beneficial metabolites such as short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs). SCFAs have been demonstrated to possess anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties and can influence gene expression and energy metabolism in distal organs via the circulatory system [38]. Therefore, the strain may foster an internal environment conducive to optimizing the function of the host’s antioxidant enzyme system by reshaping a healthier intestinal microecology, thereby generating systemic antioxidant and anti-inflammatory signals. Consistently, another study reported similar modulations of oxidative stress markers, demonstrating that administration of R. mucilaginosa ZTHY2 in immunosuppressed mice increased the activities of SOD, CAT, and GSH in spleen tissue while reduced the MDA levels [39]. Unlike classic antioxidants such as β-carotene, which directly donate electrons to scavenge free radicals, R. mucilaginosa JAASSRY does not substantially introduce exogenous antioxidant molecules. Instead, similar to some functional probiotics—for example, Lactobacillus fermentum LF-HFY02, which primarily exhibits the ability to systemically enhance the host’s endogenous antioxidant defense system and significantly elevate the activities of key enzymes such as SOD, GSH-Px, and CAT [31]. In contrast, structurally complex plant polysaccharides such as Angelica sinensis polysaccharide (ASP) have been shown not only to reduce ROS and 8-OHdG but also to deeply intervene in cellular senescence signaling pathways and regulate key development/aging-related signals [40]. Although the present study demonstrates that R. mucilaginosa JAASSRY exerts a potent reversal effect on oxidative stress markers, its improvement of systemic aging hallmarks and multi-tissue functions suggests that it may harbor a similarly multi-layered anti-aging mechanism that extends beyond mere antioxidant activity. This provides an important direction for future investigations into whether it regulates specific signaling pathways.

In this study, aging mice exhibited prolonged immobility time in the tail suspension test and decreased grip strength, alongside significantly shortened latency in the step-down test. These behavioral alterations collectively reflect typical age-related declines in motor function and cognitive ability. Intervention with R. mucilaginosa JAASSRY effectively reversed the deterioration of these behavioral indicators. In terms of motor function, the marked improvement in grip strength suggests that R. mucilaginosa JAASSRY may mitigate aging-associated loss of muscle strength, potentially through mechanisms such as regulation of neuromuscular junction function [41] or enhancement of mitochondrial energy metabolism [42]. Regarding cognitive performance, the increased latency across all phases of the step-down test, particularly during the memory phase, indicates a neuroprotective effect of R. mucilaginosa JAASSRY. This may involve the mechanisms as attenuation of oxidative damage in the hippocampus and modulation of brain-derived neurotrophic factor expression [43]. Compared with the β-carotene group, the high-dose R. mucilaginosa (HR) group exhibited a more pronounced trend in improving grip strength. This may be attributed to the whole-cell bioactive composition in it, including carotenoids and polysaccharides. That is the multiple active substances present in R. mucilaginosa cells may act synergistically to activate the oxidative defense system, thereby demonstrating distinct advantages in protecting neuromuscular function.

R. mucilaginosa JAASSRY also exerted significant beneficial effects on the gut microbiota of aging mice. 16S rRNA sequencing analysis revealed that R. mucilaginosa JAASSRY effectively reshaped the gut microbial structure in aging mice. At the phylum level, it significantly suppressed the elevated abundance of Proteobacteria observed in the AM group. Previous studies have indicated that the relative abundance of Proteobacteria is lower in normal mice compared with aging mice [44], and the effect of R. mucilaginosa JAASSRY observed here is consistent with that report. At the genus level, the intervention significantly increased the relative abundance of Lactobacillus (p < 0.01) and significantly reduced the relative abundances of Oscillospira and Helicobacter (p < 0.05). These results indicate that R. mucilaginosa JAASSRY effectively inhibited the expansion of potential pathogens such as Helicobacter, while promoting the proliferation of beneficial bacteria such as Lactobacillus. Previous research has shown that in aging rats, interventions with L. fermentum DR9 and L. helveticus OFS 1515 could increase the intestinal abundance of Lactobacillus, thereby enhancing intestinal barrier function through modulation of the gut microbiota [45]. Another study comparing young and aged mice reported that the relative abundance of Oscillospira tended to be higher in young mice—a trend contrasting with the reduction observed following JAASSRY treatment in our experiment—suggesting that R. mucilaginosa JAASSRY had microbial regulatory effects targeting specific genus [46]. Notably, random forest analysis identified Lactobacillus and Pediococcus as representative genera in the high-dose R. mucilaginosa (HR) group. These genera showed significant correlations with multiple antioxidant indicators, including positive correlations with brain CAT and SOD activities and a negative correlation with brain MDA content. Previous studies have demonstrated that a kelp fermentation broth prepared using P. pentosaceus exerted beneficial effects in D-galactose-induced aging mice, effectively preventing increases in MDA levels in serum and brain tissue, elevating superoxide dismutase and catalase activities and total antioxidant capacity, while also improving gut microbial community structure [47].

In the present study, as a recognized potential pathogen, Helicobacter was not only a representative high-abundance genus in the AM group, but also identified as a potential biomarker of aging-associated microbial dysbiosis. It has been reported that Helicobacter can accelerate cellular aging by inducing chronic inflammation [48] and oxidative stress [49]. In our experiment, the reduction in Helicobacter abundance following R. mucilaginosa JAASSRY intervention, along with the concurrent improvement in antioxidant indicators, suggested that R. mucilaginosa JAASSRY may directly inhibit Helicobacter growth or competitively suppress its colonization by restoring beneficial bacteria such as Lactobacilli, thereby contributing to delayed aging in mice.

With respect to microbial metabolic function, compared to the AM group, the HR group exhibited significantly elevated gene abundances related to nucleotide metabolism, lipid metabolism, and carbohydrate metabolism. These metabolic pathways were positively correlated with antioxidant indicators such as serum CAT and brain SOD activities, suggesting that R. mucilaginosa JAASSRY may modulate the host’s oxidative stress status by restructuring the metabolic potential of the gut microbiota. Enhanced nucleotide metabolism could facilitate the renewal and repair of intestinal epithelial cells [50], upregulation of carbohydrate metabolism may supply substrates for short-chain fatty acid production [51], and improved lipid metabolism might help mitigate lipid peroxidation damage [52]. In contrast, pathways such as amino acid metabolism and environmental adaptation, which showed abnormal activity in the AM group, were negatively correlated with oxidative stress parameters. This pattern may reflect a state of metabolic reprogramming under aging conditions, wherein fundamental metabolic processes are suppressed as the microbiota diverts resources to cope with environmental stress [53]. R. mucilaginosa JAASSRY appears to counteract this unfavorable metabolic shift, redirecting microbial activity toward core metabolic pathways that are critical for host health maintenance.

As mentioned above, R. mucilaginosa JAASSRY optimizes the metabolic function of the gut microbiota by promoting the proliferation of beneficial bacteria such as Lactobacillus and inhibiting the growth of harmful bacteria such as Helicobacter. This microbial remodeling may subsequently modulate the host’s systemic oxidative stress status via the gut–brain axis. In contrast to direct supplementation with single-component antioxidants such as β-carotene, R. mucilaginosa JAASSRY exhibits multi-target and systemic regulatory properties.

R. mucilaginosa JAASSRY strain on systemic and cerebral oxidative stress, histopathology, behavior, and gut microbiota in a D-galactose-induced aging model, several limitations remain that require resolution in future research. First, the underlying mechanisms require further elucidation. Although this study preliminarily observed that bacterial intervention can modulate nucleotide, lipid, and carbohydrate metabolism to enhance antioxidant capacity, the specific signaling pathways and key metabolite changes remain unclarified. Validation through transcriptomics and metabolomics will be crucial for elucidating the core molecular mechanisms. Second, the causal relationship between gut microbiota alterations and phenotypic improvements needs further verification. Future studies should employ fecal microbiota transplantation experiments or germ-free animal models to directly test whether the microbiota modulated by R. mucilaginosa can independently replicate its anti-aging phenotypes, thereby establishing a causal role for its “gut–brain axis”-mediated effects. Finally, sample size and intervention duration could be further optimized. Although the animal sample size in this study meets preliminary pharmacodynamic evaluation standards, a larger cohort would enhance statistical power and allow for more in-depth subgroup analyses. Moreover, extending the intervention period or implementing different intervention windows would help assess its long-term effects and potential for preventive applications.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that R. mucilaginosa JAASSRY effectively mitigates cerebral oxidative damage and behavioral impairments in D-galactose-induced aging mice. The underlying mechanism is mediated through the remodeling of gut microbiota structure, characterized by an increased abundance of beneficial bacteria such as Lactobacillus, suppression of potentially harmful bacteria including Proteobacteria and Helicobacter, and subsequent regulation of key microbial metabolic pathways involving nucleotide, lipid, and carbohydrate metabolism. Notably, high-dose R. mucilaginosa JAASSRY yielded effects comparable or even superior to β-carotene in ameliorating cerebral oxidative stress markers and promoting the colonization of probiotic bacteria, highlighting its potential as a microbial-based alternative to conventional antioxidant supplements. These findings provided a scientific basis for the application of β-carotene-producing R. mucilaginosa in functional foods targeting healthy aging and sustainable animal production and offered a multi-targeted and systemic intervention strategy against age-related decline.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.F., X.X. and J.W.; methodology, X.M. and Y.H.; software, Y.H. and D.L.; validation, M.S. and X.W.; formal analysis, H.N. and X.M.; resources, X.W.; data curation, F.A. and X.X.; writing—original draft preparation, F.A.; writing—review and editing, M.H., H.X. and J.W.; supervision, Y.F., M.H., H.X., J.W. and D.L.; funding acquisition, J.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Jilin Science and Technology Development Plan (YDZJ202403012CGZH).

Institutional Review Board Statement

All animal experiments were approved by the Laboratory Animal Management and Ethics Committee of the Institute of Agro-food Technology, Jilin Academy of Agricultural Sciences (NO. LAMECJAAS-2025-010-04).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

We thank all of the members of the laboratory for their support and constructive comments, and all authors included in this section have consented to the acknowledgement.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SOD | superoxide dismutase |

| MDA | malondialdehyde |

| CAT | catalase |

| GSH-Px | glutathione peroxidase |

Appendix A

Figure A1.

Relative abundance of KEGG signaling pathway functional gene expression in each group.

References

- Sailwal, M.; Mishra, P.; Bhaskar, T.; Pandey, R.; Ghosh, D. Time-resolved transcriptomic profile of oleaginous yeast Rhodotorula mucilaginosa during lipid and carotenoids accumulation on glycerol. Bioresour. Technol. 2023, 384, 129379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Q.; Lyu, L.; Xue, H.; Shah, A.M.; Zhao, Z.K. Engineering a Non-Model Yeast Rhodotorula mucilaginosa for Terpenoids Synthesis. Synth. Syst. Biotechnol. 2024, 9, 569–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mattos, M.V.C.d.V.d.; Michelon, M.; Burkert, J.F.d.M. Production and stability of food-grade liposomes containing microbial carotenoids from Rhodotorula mucilaginosa. Food Struct. 2022, 33, 100282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosqueda-Martínez, E.; Chiquete-Félix, N.; Castañeda-Tamez, P.; Ricardez-García, C.; Gutiérrez-Aguilar, M.; Uribe-Carvajal, S.; Mendez-Romero, O. In Rhodotorula mucilaginosa, active oxidative metabolism increases carotenoids to inactivate excess reactive oxygen species. Front. Fungal Biol. 2024, 5, 1378590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentina, J.C.; Ah-Hen, K.S.; Alvarado, R.; Stevenson, J.; Briceño, E.; Montenegro, O.; González-Esparza, A. Survival of Spray-Dried Rhodotorula mucilaginosa Isolated from Natural Microbiota of Murta Berries and Antagonistic Effect on Botrytis cinerea. Food Technol. Biotechnol. 2019, 57, 222–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Huang, E.; Li, X.; Xie, Y.; Tong, T.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Q. Effects of dietary marine red yeast supplementation on growth performance, antioxidant, immunity, lipid metabolism and mTOR signaling pathway in Juvenile Tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). Aquac. Rep. 2024, 37, 102196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Liu, Y.; Luo, K.; Zhang, S.; Wei, C.; Wang, L.; Qiu, Y.; Tian, X. ‘Biotic’ potential of the red yeast Rhodotorula mucilaginosa strain JM-01 on the growth, shell pigmentation, and immune defense attributes of the shrimp, Penaeus vannamei. Aquaculture 2023, 572, 739543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jati, I.R.A.P.; Darmoatmodjo, L.M.Y.D.; Suseno, T.I.P.; Ristiarini, S.; Wibowo, C. Effect of Processing on Bioactive Compounds, Antioxidant Activity, Physicochemical, and Sensory Properties of Orange Sweet Potato, Red Rice, and Their Application for Flake Products. Plants 2022, 11, 440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Cortes, A.; Garcia-Vásquez, J.A.; Aranguren, Y.; Ramirez-Castrillon, M. Pigment Production Improvement in Rhodotorula mucilaginosa AJB01 Using Design of Experiments. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bo, S.; Ni, X.; Guo, J.; Liu, Z.; Wang, X.; Sheng, Y.; Zhang, G.; Yang, J. Carotenoid Biosynthesis: Genome-Wide Profiling, Pathway Identification in Rhodotorula glutinis X-20, and High-Level Production. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 918240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Xie, Z.; Zhao, D.; Li, B.; Wang, D.; Chang, L.; Feng, F.; Zheng, L.; Wang, X.; Shao, M.; et al. Multi-omics analysis provides insights into the enhancement of β-carotene and torularhodin production in oleaginous red yeast Sporobolomyces pararoseus under H2O2-induced oxidative stress. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 197, 115947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, B.; Guo, Q.; Wang, Z.; Shao, J.-B.; Liu, K.; Du, Z.-D.; Gong, S.-S. D-Galactose-induced oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction in the cochlear basilar membrane: An in vitro aging model. Biogerontology 2020, 21, 311–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pantiya, P.; Thonusin, C.; Ongnok, B.; Chunchai, T.; Kongkaew, A.; Nawara, W.; Arunsak, B.; Chattipakorn, N.; Chattipakorn, S.C. Long-term D-galactose Administration Mimics Natural Aging in Rat’s Hippocampus. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2023, 19, e073540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, R.; Lee, W.-Y.; Park, H.-J. Effects of Melatonin on Liver of D-Galactose-Induced Aged Mouse Model. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2023, 45, 8412–8426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumbalová, Z.; Uličná, O.; Kucharská, J.; Rausová, Z.; Vančová, O.; Melicherčík, Ľ.; Tvrdík, T.; Nemec, M.; Kašparová, S. D-galactose-induced aging in rats—The effect of metformin on bioenergetics of brain, skeletal muscle and liver. Exp. Gerontol. 2022, 163, 111770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, J.; Yun, Y.; Xue, J.; Sun, M.; Kim, S. D-galactose induces astrocytic aging and contributes to astrocytoma progression and chemoresistance via cellular senescence. Mol. Med. Rep. 2019, 20, 4111–4118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Li, A.; Zhang, X.; Iqbal, M.; Aabdin, Z.U.; Xu, M.; Mo, Q.; Li, J. Effect of Bacillus subtilis isolated from yaks on D-galactose-induced oxidative stress and hepatic damage in mice. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1550556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, T.; Li, M.; Wang, Y.; Cao, J.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Cheng, G. Protective Effect of Que Zui Tea on d-Galactose-Induced Oxidative Stress Damage in Mice via Regulating SIRT1/Nrf2 Signaling Pathway. Molecules 2024, 29, 1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Zhang, N.; Srivastava, A.K.; He, G.; Tai, Z.; Wang, Z.; Yang, S.; Xie, X.; Li, X. Superoxide dismutase positively regulates Cu/Zn toxicity tolerance in Sorghum bicolor by interacting with Cu chaperone for superoxide dismutase. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 480, 135828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, M.R.; Sampaio, I.H.; Teodoro, B.G.; Sousa, T.A.; Zoppi, C.C.; Queiroz, A.L.; Passos, M.A.; Alberici, L.C.; Teixeira, F.R.; Manfiolli, A.O.; et al. Hydrogen peroxide production regulates the mitochondrial function in insulin resistant muscle cells: Effect of catalase overexpression. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)—Mol. Basis Dis. 2013, 1832, 1591–1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Yan, Q.; Gao, C.; Lin, L.; Wei, J. Study on antioxidant effect of recombinant glutathione peroxidase 1. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 170, 503–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toto, A.; Wild, P.; Graille, M.; Turcu, V.; Crézé, C.; Hemmendinger, M.; Sauvain, J.-J.; Bergamaschi, E.; Guseva Canu, I.; Hopf, N.B. Urinary Malondialdehyde (MDA) Concentrations in the General Population—A Systematic Literature Review and Meta-Analysis. Toxics 2022, 10, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatterjee, K.; Mazumder, P.M.; Banerjee, S. Vitamin K2 Protects Against D-Galactose Induced Ageing in Mice. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2025, 990, 177277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Csepanyi, E.; Czompa, A.; Haines, D.; Lekli, I.; Bakondi, E.; Balla, G.; Tosaki, A.; Bak, I. Cardiovascular Effects of Low Versus High-Dose Beta-Carotene in a Rat Model. Pharmacol. Res. 2015, 100, 148–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choy, K.H.C.; Luo, J.K.; Wannan, C.M.J. Cognitive behavioral markers of neurodevelopmental trajectories in rodents. Transl. Psychiatry 2021, 11, 556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Ji, Z.; Zhang, B.; Geng, L.; Cai, Y.; Nie, C.; Li, J.; Zuo, Y.; Sun, Y.; Xu, G.; et al. Spatial transcriptomic landscape unveils immunoglobin-associated senescence as a hallmark of aging. Cell 2024, 187, 7025–7044.e34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Chen, Z.; Jiang, Z. Cordycepin prevents radiation ulcer by inhibiting cell senescence via NRF2 and AMPK in rodents. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 2538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mossad, O.; Batut, B.; Yilmaz, B. Gut microbiota drives age-related oxidative stress and mitochondrial damage in microglia via the metabolite N6-carboxymethyllysine. Nat. Neurosci. 2022, 25, 295–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Wu, J.; Dong, Q.; Ma, J.; Gao, H.; Liu, G.; Chen, Y.; Ning, J.; Lv, X.; Zhang, M.; et al. The crosstalk between oxidative stress and DNA damage induces neural stem cell senescence by HO-1/PARP1 non-canonical pathway. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2024, 223, 443–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, W. Nobiletin Mitigates D-Galactose-Induced Memory Impairment via Improving Hippocampal Neurogenesis in Mice. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, T.; Chen, R.; Qian, Y.; Ye, K.; Long, X.; Park, K.-Y.; Zhao, X. Antioxidant effect of Lactobacillus fermentum HFY02-fermented soy milk on D-galactose-induced aging mouse model. Food Sci. Hum. Wellness 2022, 11, 1362–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, A.; Bian, W.-P.; Feng, S.-L.; Pu, S.-Y.; Wei, X.-Y.; Yang, Y.-F.; Song, L.-Y.; Pei, D.-S. Role of manganese superoxide dismutase (Mn-SOD) against Cr(III)-induced toxicity in bacteria. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 403, 123604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tumilaar, S.G.; Hutabarat, G.S.; Hardianto, A.; Kurnia, D. Computational Studies of Allylpyrocatechol from Piper betle L. as Inhibitor Against Superoxide Dismutase, Catalase, and Glutathione peroxidase as Antioxidant Enzyme. Lett. Drug Des. Discov. 2022, 21, 559–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyfi Zouleh, R.; Rahimnejad, M.; Najafpour-Darzi, G.; Sabour, D.; Almeida, J.M.S.; Brett, C.M.A. A catalase enzyme biosensor for hydrogen peroxide at a poly(safranine T)-ternary deep eutectic solvent and carbon nanotube modified electrode. Microchem. J. 2023, 195, 109475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabowo, R.; Mariana, S. Measurement of malondialdehyde (MDA) level and superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity in the pancreatic tissue after the intervention of orange water kefir in the hyperlipidemic rats model. Int. J. Surg. 2022, 100, 106527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.; Zhao, J.; Ma, L.; Chen, J.; Xu, J.; Rahman, S.U.; Feng, S.; Li, Y.; Wu, J.; Wang, X. Lycopene Attenuates Zearalenone-Induced Oxidative Damage of Piglet Sertoli Cells Through the Nuclear Factor Erythroid-2 Related Factor 2 Signaling Pathway. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021, 225, 112737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, D.V.; Suryajaya, K.G.; Manh, K.; Duong, A.N.; Chan, J.Y. Characterization of NFE2L1-616, an Isoform of Nuclear Factor-Erythroid-2 Related Transcription Factor-1 That Activates Antioxidant Response Element-Regulated Genes. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 19900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X.; Wang, L.; Bhat, O.M.; Lohner, H.; Li, P.-L. Differential Effects of Short Chain Fatty Acids on Endothelial Nlrp3 Inflammasome Activation and Neointima Formation: Antioxidant Action of Butyrate. Redox Biol. 2018, 16, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, K. Rhodotorula mucilaginosa ZTHY2 Attenuates Cyclophosphamide-Induced Immunosuppression in Mice. Animals 2023, 13, 3376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, X.Y.; Zhang, Y.Y.; Li, J.; Xia, J.Y.; Chen, X.B.; Jing, P.W.; Song, X.Y.; Wang, L.; Wang, Y.P. Angelica Sinensis Polysaccharide Prevents Hematopoietic Stem Cells Senescence in D-Galactose-Induced Aging Mouse Model. Stem Cells Int. 2017, 2017, 3508907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koizumi, H. Impact of the contraction of medial forearm muscles during grip tasks in different forearm positions on medial support at the elbow joint. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 2023, 71, 102783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, S. Targeting the mTOR-mitochondrial function axis: Calcitriol attenuates sarcopenic obesity with lipid dysregulation etiology. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2026, 242, 305–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Izquierdo-Altarejos, P.; Sanchez-Huertas, C.; Moreno-Manzano, V.; Felipo, V. OS150—Extracellular vesicles from mesenchimal stem cells reduce neuroinflammation in hippocampus and restore cognitive function in hyperammonemic rats. J. Hepatol. 2022, 77, S103–S104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.G. Impacts of Aging and Blackcurrant Supplementation on the Gut Microbiome Profile of Female Mice (P20-031-19). Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2019, 3, nzz040.P20-031-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hor, Y.-Y. Lactobacillus sp. improved microbiota and metabolite profiles of aging rats. Pharmacol. Res. 2019, 146, 104312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conley, M.N. Aging and serum MCP-1 are associated with gut microbiome composition in a murine model. PeerJ 2016, 4, e1854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, W. Probiotic Fermentation of Kelp Enzymatic Hydrolysate Promoted its Anti-Aging Activity in D-Galactose-Induced Aging Mice by Modulating Gut Microbiota. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2023, 67, 2200766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S. Helicobacter pylori-positive chronic atrophic gastritis and cellular senescence. Helicobacter 2023, 28, e12944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waragai, Y.; Kuroda, M.; Kodama, K.; Kanno, Y.; Miyata, M. Su1395 Effects of Helicobacter Pylori Eradication for Elderly Patients. Gastroenterology 2020, 158, S-575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Cao, Y.; Xu, C.; Zhang, S.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Bao, W. Comprehensive transcriptomic and metabolomic analysis of porcine intestinal epithelial cells after PDCoV infection. Front. Vet. Sci. 2024, 11, 1359547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frampton, J.; Murphy, K.G.; Frost, G. Short-chain fatty acids as potential regulators of skeletal muscle metabolism and function. Nat. Metab. 2020, 2, 840–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Ma, Y.; Xie, Y.; Zhao, D.; Li, C. Carrageenan in meat: Improvement in lipid metabolism due to Sirtuin1-mediated fatty acid oxidation and inhibited lipid bioavailability. Food Funct. 2023, 14, 5404–5416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, Y.; Huang, J.; Zhou, R.; Zhang, S.; Qin, H.; Tang, H.; Pan, Q.; Tang, H. Bioaugmented Daqu-induced variation in community succession rate strengthens the interaction and metabolic function of microbiota during strong-flavor Baijiu fermentation. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 182, 114806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.