Abstract

Increasing pollution and public health concerns over persistent pollutants necessitate efficient methods like photocatalytic degradation. Despite its potential in air and water treatment, the scale-up of this technology is limited due to insufficient modeling studies. This research explores the photocatalytic degradation of benzo[a]pyrene (BaP) using immobilized zinc oxide (ZnO) photocatalysts in a 500 mm length annular reactor. The reactor has a 150 mm porous ZnO domain and a UV lamp. Process variables such as the BaP concentration, residence time, surface irradiance, and catalyst zone length were modeled using computational fluid dynamics (CFD). CFD simulations using a pseudo-first-order kinetic model revealed that optimizing these parameters significantly improved the degradation efficiency. The results revealed that optimizing these parameters enhanced the degradation efficiency by over thirteen times compared to the initial setup. The increased residence time, reduced BaP concentration, and improved surface irradiance allowed for more efficient pollutant breakdown, while a longer catalyst zone supported more complete reactions. However, challenges like the high recombination rates of electron–hole pairs and susceptibility to photo-corrosion persist for ZnO. Further studies are recommended to address these challenges.

1. Introduction

Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) are contaminants found widely in the environment, such as in ambient air. It is produced primarily when a fuel such as coal, petrol, wood, and oil is not fully combusted [1]. In this regard, PAHs are a ubiquitous organic pollutant with three major sources: pyrogenic, petrogenic, and biological. Seventeen PAHs are determined to cause adverse health effects. Several of these are noted mutagens, teratogens, and carcinogens, posing a worrying threat to human well-being [2]. With PAHs being moderately persistent in the environment, bioaccumulation can happen, with exposure occurring on a regular basis for most people [1]. This prompts the study and research on effective environmental remediation processes. Photocatalytic degradation using substances such as titanium dioxide (TiO2) destroys the organic contaminant in a relatively shorter length of time [3].

Many existing studies on the photocatalytic degradation of PAHs have discussed the impact of such pollutants in different environments such as soil, water, and air, and how photocatalysis can remediate such effects [3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12]. Numerous studies also include a discussion of where photocatalytic degradation is in terms of the current knowledge of photocatalysts, photocatalytic reactors, and their viability for applications of a larger scale. Photocatalytic degradation is an effective and cost-efficient method for removing persistent organic pollutants like PAHs from the environment [11]. This process involves the use of semiconductor catalysts, which generate reactive radicals upon exposure to light, leading to the degradation of organic pollutants into simpler products like carbon dioxide (CO2) and water (H2O) [5,11]. TiO2 is the most studied photocatalyst due to its low cost and stability, but zinc oxide (ZnO) is also a promising alternative due to its similar bandgap energy and better absorption across a wide spectrum of solar radiation [6,7]. However, ZnO has limitations such as a high rate of electron–hole recombination and low optical absorption capabilities, which can be addressed through modifications such as microstructure tuning or coupling with other semiconductors [8,9]. The reactor configuration is also important in photocatalytic degradation, with continuous flow reactors showing potential for large-scale industrial applications. Computational fluid dynamics (CFD) can be used to simulate and optimize photocatalytic reactors, providing insights into the flow and distribution of reactants and products within the reactor [10]. CFD simulations can also help identify optimal reactor configurations and design parameters to enhance the photocatalytic efficiency [12].

Photocatalysis has shown great potential as a remediation method, with it removing harmful chemicals using available solar energy and catalytic materials with low or negligible toxicity. However, it has its drawbacks, which are not often addressed in the current literature [13]. Photocatalytic processes have several limitations, which are often attributed to a low photoconversion efficiency [14]. To clarify, conventional photocatalytic reactors present limitations like a poor light distribution inside the reactor and low surface areas for the photocatalyst per unit volume of reactor [15]. These result in a need for more optimized photocatalytic reactor configurations.

The present rapid development of the industry has been heavily reliant on non-renewable energy sources and has caused an increase in the atmospheric carbon dioxide concentration, resulting in concerning energy and environmental crises [16,17,18]. It is thus imperative to understand better how to develop technology for the sustainable growth of society. Pollutants such as PAHs are some of the most frequently detected petroleum hydrocarbons and have a significant detrimental impact on the environment and health due to their environmental persistence, potential bioaccumulation, and toxicity [19].

From several studies such as Ekanem et al. (2019) and Ekere et al. (2019) that have studied sediment and water samples for PAHs, the concentrations of PAHs in these samples are found to be around 5940 ng/g to 9723.9 ng/g dry weight (dw), with a mean value of 7762.7 ng/g dw [20,21,22,23]. Several of the PAHs studied have also been classified as carcinogenic and have been found to comprise 46% of a water sample, according to the US Environmental Protection Agency (US EPA) [24]. Hence, the World Health Organization (WHO) declares that the maximum permissible level for PAHs in drinking water is 200 ng/L [22]. Given the general concentration of PAHs in water and soil, effective removal methods and techniques are critical in addressing the current problem through a reduction in PAHs to levels safe for drinking water production [24].

For that matter, the role of photocatalysis becomes critical for its capability to effectively degrade even complex pollutants while being an environmentally friendly technology [25]. Developing a more efficient photocatalytic degradation method for PAHs such as benzo[a]pyrene (BaP) using a reactor configuration is then beneficial for environmental protection and will help in the development of other environmental remediation processes that utilize such technology. As PAHs contaminate bodies of water, the degradation of these pollutants through photocatalysis helps reduce the impact of pollution on marine ecosystems [26].

With that said, our study aims to develop a model for an annular, photocatalytic reactor using CFD through ANSYS® Fluent software Academic Version 2024 R1, and perform simulations of the photocatalytic degradation of BaP using an immobilized ZnO photocatalyst. In addition, the effects of varying operation conditions, namely, the residence time, initial BaP concentration, surface irradiance, and catalyst zone length, on the reaction rate and degradation efficiency are determined. This study will be significant in developing optimum reactor configurations and operating parameters for the efficient photocatalytic degradation of PAHs using immobilized ZnO and reducing the costs of building reactors for experimental studies. As this study is carried out through CFD, the following are also considered: fluid flow, heat and mass transfer, and the primary chemical reaction involved in photocatalytic degradation. Subsequently, this study will not include the degradation of other PAHs, the modification of the photocatalyst for enhancement like the doping of another semiconductor to reduce electron–hole recombination and improve photon absorption, and other factors that affect the overall performance of a photocatalytic reaction like the reactor material type, pH, and reaction temperature.

2. Materials and Methods

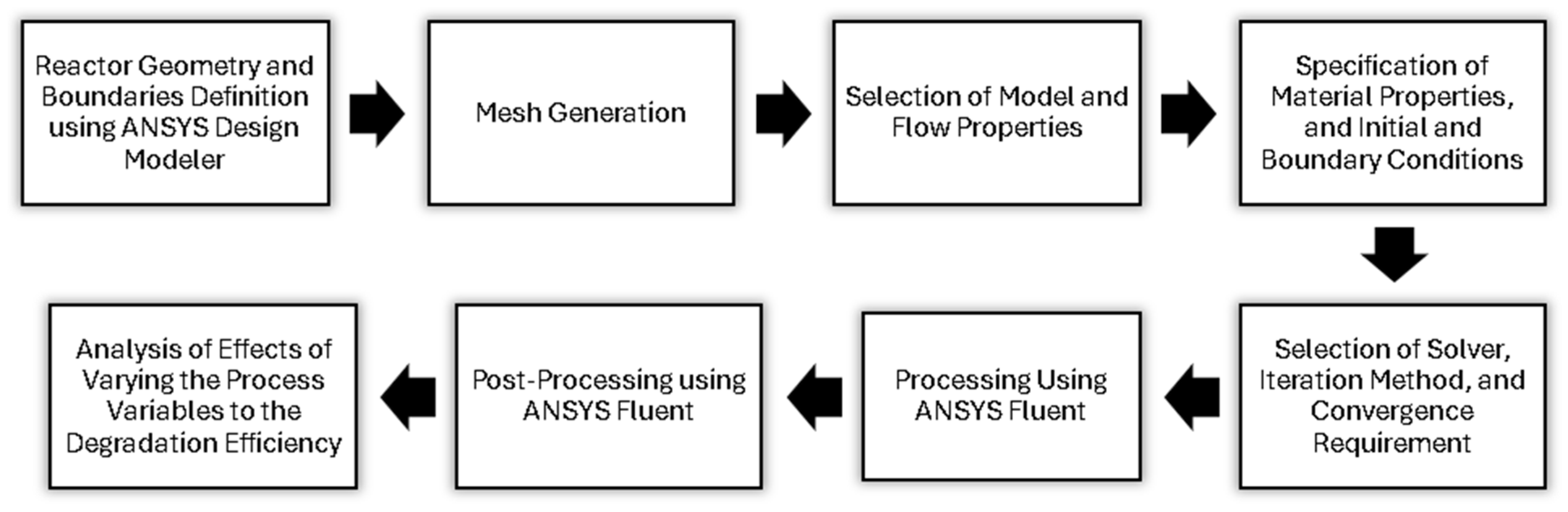

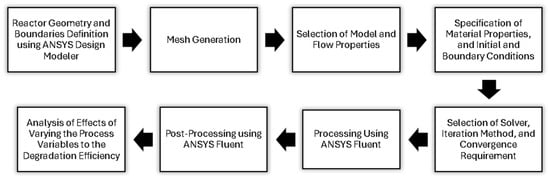

This study utilizes the mathematical modeling tool CFD in predicting the phenomena of fluid flow as it simulates according to the laws of conservation concerning mass, momentum, and energy of fluid motion. To better understand, Figure 1 and Table 1 detail the process involving computational fluid dynamics and the summary of equations governing the model, respectively.

Figure 1.

Summary of computational fluid dynamics analysis.

Table 1.

Summary of CFD model governing equations.

The figure above outlines the process of achieving this study’s objectives. Initially, the reactor geometry and specifications, including inlet and outlet diameters and catalyst zone lengths, were established. The reactor geometry and mesh were then developed using the Design Modeler and Meshing tool within the ANSYS® Workbench. Models for fluid flow, species transport, and radiation were identified, and the physical properties of the BaP solution, ZnO photocatalysts, and boundary conditions were all defined beforehand. Accordingly, the CFD analysis was conducted on an Intel® i7-8650U computer with 8 GB RAM. We have used ANSYS® Fluent Academic Version 2024 R1 for our CFD software (www.ansys.com). Then, we have varied the parameters such as catalyst zone length, initial BaP concentration, residence time, and surface irradiance to evaluate their impact on photocatalytic degradation efficiency. The analysis of the results was performed using the CFD Post-Processing Tool in ANSYS® Fluent. Using the tool, various visualizations such as contour plots and vector plots were generated and used in the interpretation of the simulations’ outcomes.

2.1. Governing Kinetic Transport Equations and Kinetics

To model the transport and chemical reaction, ANSYS® Fluent will be utilized as it can solve for the mass, momentum, and species conservation equations. The fluid involved is assumed to be Newtonian, incompressible and isothermal with physical properties that are constant. The simulation was conducted under a steady-state, laminar flow and a photocatalytic surface reactions model. Table 1 summarizes the governing equations used in the CFD model. We advise the readers to check the included references mentioned in the table for details of each equation used in the study. Because the inlet velocity is laminar, a laminar flow model is utilized in the study. The continuity equation (Equations (2) and (3)) describes the governing equation for the conservation of mass, Equation (4) expresses the mass conservation equation for chemical species (i) in the computational domain, and Equation (5) uses Fick’s First Law of Diffusion to express the diffusive flux.

The dependence of reaction rate on BaP concentration and radiation was modeled using a User-Defined Function (UDF) based on the simulation by Nourizade, Rahmani et al., where LVREA is the local volumetric rate of energy absorption [29]. Equation (6) expresses the equation adopted from the UDF by Nourizade, Rahmani et al. The rate of BaP degradation is given by Equation (7), wherein k1 is the apparent kinetic constant, m is the reaction order with respect to LVREA, and C is the initial pollutant concentration. From the study of Cemera-Roda et al., for systems with ZnO photocatalysts and moderate to intense photon fluxes, the value of m is equal to 0.5 [30]. Most photocatalytic reactions follow the Langmuir–Hinshelwood–Hougen–Watson model (Equations (8) and (9)) because it reduces complex kinetics to a pseudo-first-order equation. Most specifically, it can be used for the approximation of the reaction mechanism at constant UV irradiance, wherein r is the reaction rate, C is the pollutant concentration in the solution, t is time, and Kapp is the apparent kinetic constant which considers the effects of variables including catalyst concentration. In this study, Kapp was set to a value of 0.027 h−1 or 7.5 × 10−5 s−1 (R2 = 0.99) based on the experimental results of Rachna, Rani et al. on the photocatalytic degradation of BaP [31]. Using the equations described, the rate of BaP degradation is given by the equation below.

2.2. Defining Boundary and Initial Conditions

The boundary conditions for the CFD model were defined as follows. At the inlet, the velocity of the fluid was specified to have a laminar flow of 9.08 × 10−3 m/s and the initial inlet mass fraction of BaP was set to 1 × 10−6, equivalent to 1 ppm of the pollutant in the solution. However, later in the study, the inlet mass fraction of BaP was changed to determine the effects of varying initial pollutant concentrations on the degradation efficiency. At the outlet, the boundary condition pressure was set to a value of 1 atm. The direction of the fluid flow is normal to the tube walls, and a no-slip boundary condition was imposed for all reactor walls. Except for the wall where the ZnO surface reaction of PAH degradation occurs (the 150 mm middle length of the outer pipe of the annular reactor, as shown in Figure 2), a zero diffusive flux of species was set at the walls. The defined boundary condition at the surface reaction of degradation was based on the rate equation shown in Table 1. It will be assumed that the degradation of the PAH in water occurs at room temperature, 25 °C (298.15 K).

2.3. Modeling of Radiation Field, Flow Domain, and Geometry

Photoreactor modeling requires analysis of the reactor’s hydrodynamics, radiation transfer equation (RTE), reaction kinetics, and mass balance. To understand the nature of the flow of the solution and radiation field within the annular reactor, hydrodynamic modeling is required. Hydrodynamic modeling enables full spatial characterization of the flow inside the reactor [32].

Irradiance strength on the surface of the catalyst relies on the uniformity of the radiation field. Therefore, a uniform intensity across the entire catalyst surface is assumed. The radiation field provided by the UV lamp in annular photocatalytic reactors is modeled using the Discrete Ordinates method (DO). The Discrete Ordinates Model (DOM) is used in simulations of various types of photochemical or photocatalytic (immobilized or slurry) reactors due to its accuracy. DOM is selected as the numerical method to discretize the angular space in various directions represented by the radiative transport equation (RTE). This method was used due to its reliability amongst available models in capturing the behavior of radiation distribution inside the reactor. The boundary conditions used to solve the RTE (Equation (1)) with the DOM in the simulation include a uniform distribution of diffuse emission on the lamp surface, semi-transparent inner walls with specular transmission and zero emissivity, and a constant temperature of 1 K and emissivity of 1 for the outside walls. The surface irradiance was initially set to 60 W/m2, which was varied to higher values later in the study to determine the effects of the intensity of surface irradiance on the reaction rate and degradation efficiency.

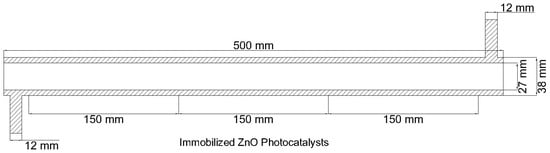

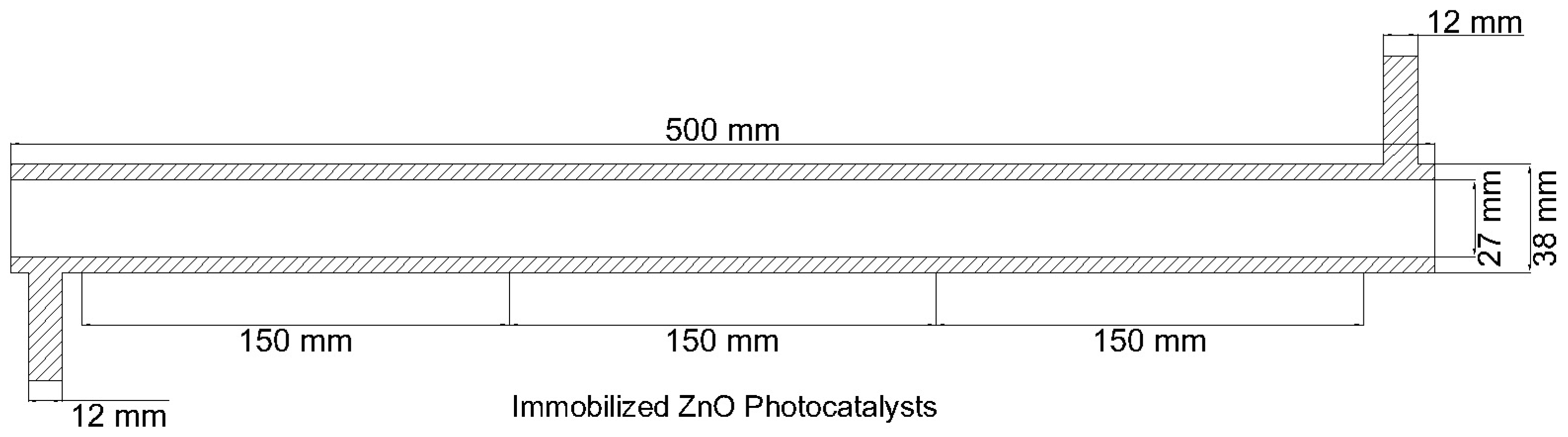

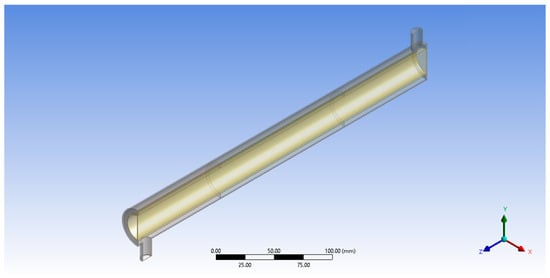

For the photocatalytic degradation of PAHs in an aqueous solution, an annular reactor geometry based on the immobilized TiO2-based annular photocatalytic reactor used in the experimental study by Kumar et al. was considered [33]. Figure 2 shows the schematic diagram of the annular photocatalytic reactor used in this study for the CFD simulations.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of the annular reactor [34].

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of the annular reactor [34].

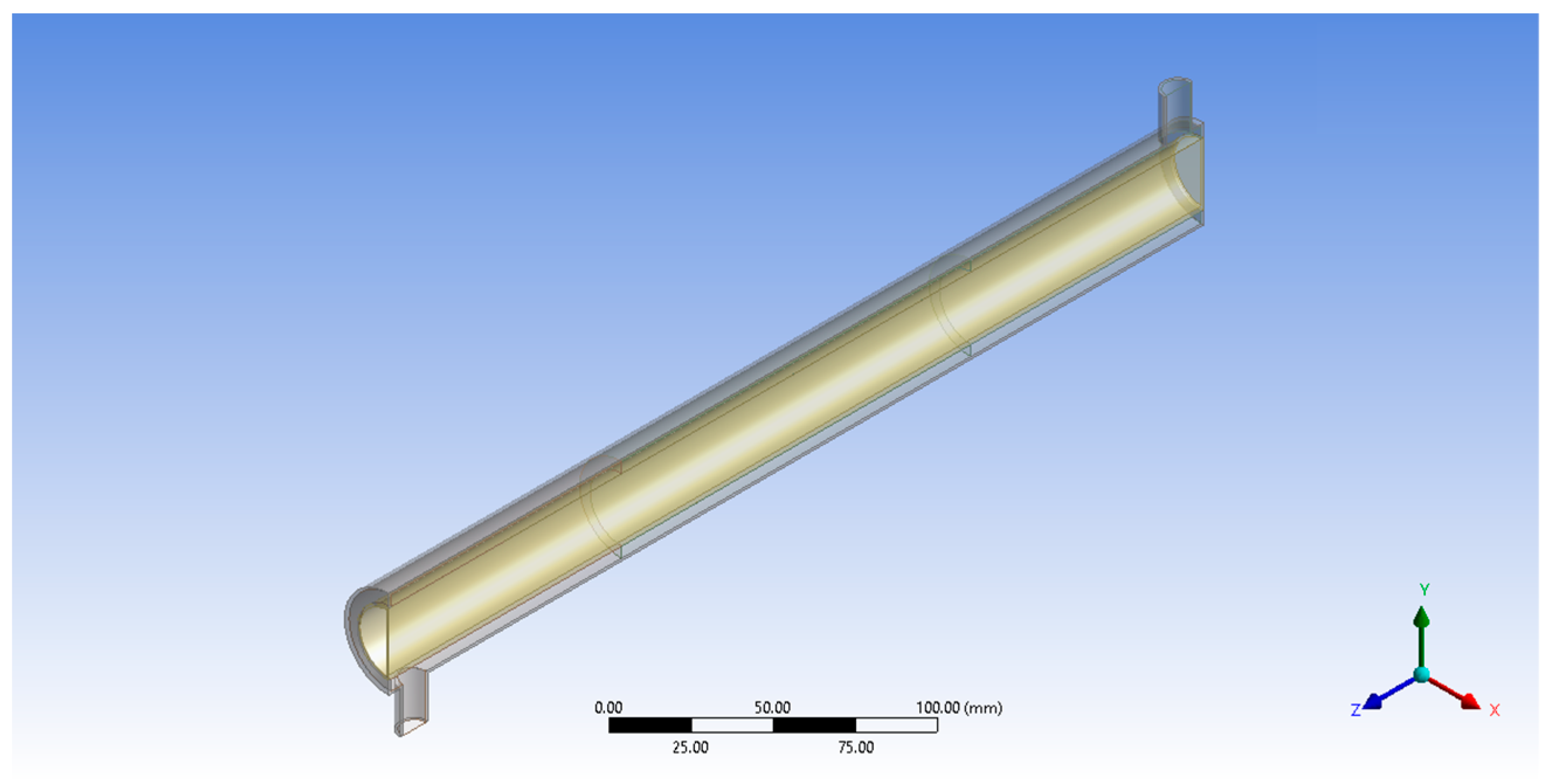

Following the specifications from Figure 2, ANSYS® Design Modeler was used to create a geometry model of the annular reactor (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Geometry model for annular reactor.

The total reactor length is 500 mm, with the central 450 mm used for the photocatalytic degradation of the BaP. The inlet and outlet tubes, placed at opposite ends of the reactor, have a diameter of 12 mm. The 38 mm inner diameter wall is made of a Pyrex glass tube and the inner tube with 27 mm inner diameter at the center of the reactor is made of quartz glass and houses the cylindrical UV lamp that serves as the reactor’s light source. The inner surface of the outer Pyrex glass tube is the porous zone coated with the ZnO photocatalyst to set up the photocatalytic surface reaction. The immobilized photocatalyst forms the central 150 mm reactor length in the middle of the reactor. This was changed later in the study when the effects of catalyst zone length were investigated. The reactor specifications used in modeling are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Annular reactor specifications.

The simulation parameters have been configured to optimize accuracy and computational efficiency for studying photocatalytic degradation processes as shown in Table 3. The gradient method was set to “Least Squares Cell-Based” due to its robustness and precision in handling unstructured meshes, which are prevalent in the complex geometries of photocatalytic reactors. This method ensures accurate gradient calculations, enhancing the overall solution accuracy. “PRESTO!” (Pressure Staggering Option) was selected as the discretization scheme for pressure as it provides precise pressure–velocity coupling, along with the SIMPLE algorithm, in scenarios involving high-speed flows, steep pressure gradients, or rotating machinery, thus capturing the intricate behavior of fluid flow involving the study’s premises for photocatalytic processes [34]. The momentum equations were solved using the “Second-Order Upwind” scheme, which offers higher accuracy for convective terms by making use of a broader stencil of cells critical for detailed transport and diffusion process simulation. Lastly, the Discrete Ordinates radiation model employs the “First Order Upwind” scheme for its computational efficiency, which is essential for effectively simulating light interaction with photocatalysts in extensive or complex domains without incurring excessive computational costs.

Table 3.

Solution methods.

The default values for the under-relaxation factors (URFs) were utilized. The scaled residuals were monitored to a criterion of 1 × 10−4 for the continuity and momentum variables, and 1 × 10−6 for the concentrations to ensure the convergence of the numerical solution. The solution of the model was utilized to determine the concentration field, degradation efficiency, and reaction rate constants.

2.4. Generation of Grid and Establishment of Simulation Strategy

In generating the surface mesh and the distribution of grids in specified horizontal and vertical plates for the annular reactor, the ANSYS Mesh tool was used in creating the model’s mesh volume composed of tetrahedrons. For a complex geometry like an annular reactor, it is required to perform a grid or mesh independence study to determine the optimal grid design for the model. In ensuring that the simulation results were grid-independent, mesh sizes ranging from coarse to fine were generated.

2.5. Post-Processing of Simulation

To review the simulation, FLUENT® has post-processing tools integrated into its Fluent solver. Tools to be used in analyzing CFD results are contour plots, streamlines, path lines, and XY plotting. Numerical data for analysis provided by FLUENT such as flux reports and surface integrals are to be used as well.

2.6. Properties Involved in Reaction of CFD Model

In computational fluid dynamics, reaction modeling requires defining chemical kinetics and interactions among reactants, intermediates, and products within the domain of simulation. This process involves the specification of reaction mechanism, stoichiometry, reaction rate expressions, and used catalysts. Through modeling, reactions in various phases or those that are considered volumetric, surface, or multi-phase reactions may be simulated. FLUENT®, in this case, also supports complex reaction kinetics since it integrates even the principles of transport phenomena and fluid flow, which allows for detailed analysis of the photocatalytic degradation processes. Table 4 presents the physical properties set for the reaction. To further simplify the model, the physical properties of the solution were assumed to be the same as water (at 25 °C) since the pollutant concentration is considerably small. Therefore, the solution was set to have a density of 998.2 kg/m3 and a viscosity of 1.003 × 10−4 Pa·s. Except for BaP, Pyrex glass, and ZnO, the properties of the other chemical species involved in the reaction were obtained from the Fluent Database. Otherwise, the other materials were manually defined by adding a User-Defined Database.

Table 4.

Reaction physical property parameters of the CFD model.

Pollutant Properties

The pollutant chosen for the simulation is the PAH benzo[a]pyrene (BaP). BaP is considered the main representative of PAHs as it is ubiquitously found in the air, surface water, soil, and sediments. The chemical and physical properties of this organic compound, as summarized in Table 5, were obtained from several reference sources.

Table 5.

Physical properties of benzo[a]pyrene at reference temperature 298.15 K.

2.7. Process Variables Defined

The effects of differing the length of the packing material, initial BaP concentration, residence time, and surface irradiance on the system behavior and photocatalytic degradation efficiency were investigated. To evaluate the influence of retention on the degradation efficiency, four values of residence time were examined: 700, 800, 900, and 1000 s. The effect of initial BaP concentration was also examined with values of 0.5, 1, 10, and 20 in parts per million (ppm). Additionally, the varying light intensities with values of 60, 80, and 120 watts per square meter (W/m2) were observed. There are three lengths of the photocatalyst (porous zone) examined: 100, 150, and 200 millimeters (mm).

2.8. Photocatalytic Activity

The degradation efficiency of the photocatalyst under various conditions was evaluated and quantified using the following equation:

wherein C0 represents the initial BaP concentration and Ct is the BaP concentration in the reaction solution after some time t. Given that the reaction kinetics are of pseudo-first order, the rate constant k was calculated using the integrated rate law for first-order reactions:

3. Results and Discussion

This study presents the results of CFD modeling of an annular reactor for the photocatalytic degradation of BaP, a polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon that is considered one of the most carcinogenic of the PAH pollutants. The effects of variables such as residence time, initial pollutant concentration, surface irradiance intensity, and catalyst zone length on the efficiency of degradation and reaction rate were analyzed.

3.1. Mesh Independence Test

Prior to simulating the different parameters and performing the analysis, a mesh independence test was conducted to determine the optimal mesh to be used. This test was performed using the ANSYS® Workbench Meshing tool by generating different mesh configurations and analyzing the results to identify at which point further mesh refinement no longer significantly alters parameters, indicating grid independence.

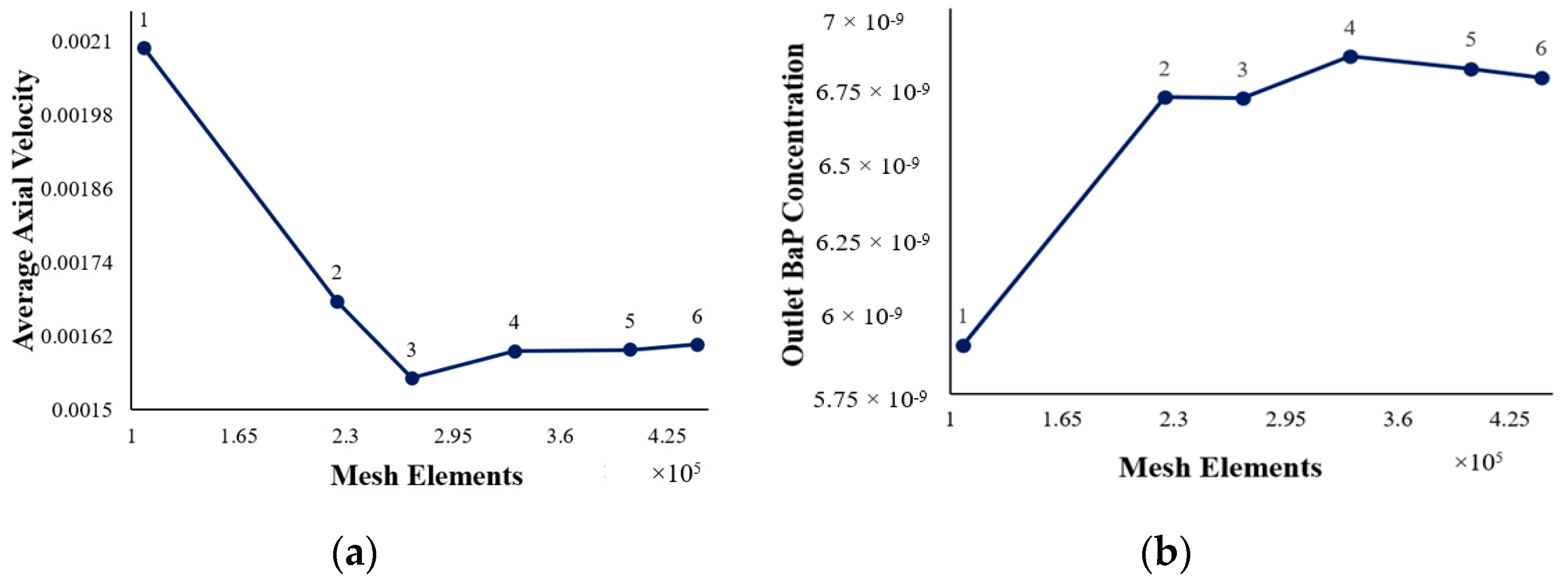

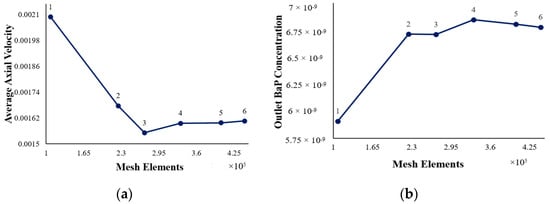

As given in the table above (Table 6), the grid was refined by increasing the number of cell volumes and decreasing the element size from 2.0 × 10−3 m to 1.15 × 10−3 m. The inlet velocity was set at 9.08 × 10−3 m/s. The dependency of the average axial velocity inside the reactor and outlet BaP concentration on the mesh size was assessed using these meshes. Figure 4 displays the axial velocity as a function of the mesh elements and the outlet BaP concentration as a function of the mesh elements.

Table 6.

Mesh element sizes used in this study.

Figure 4.

(a) Axial velocity at differing mesh element numbers; (b) outlet BaP concentrations at differing mesh element numbers.

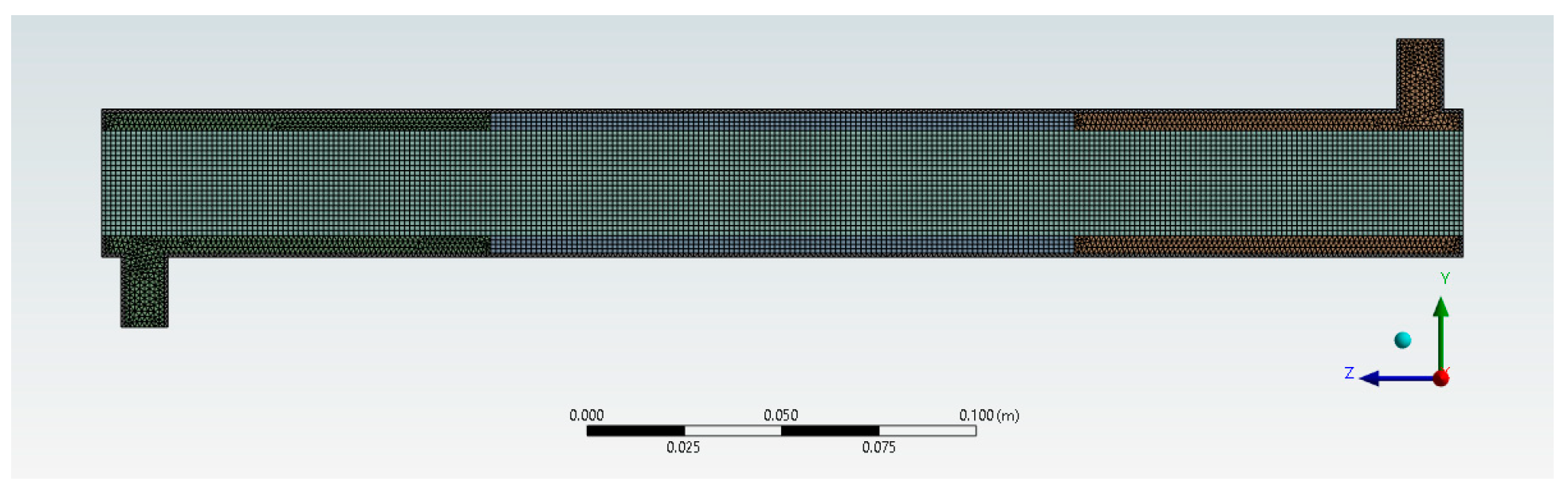

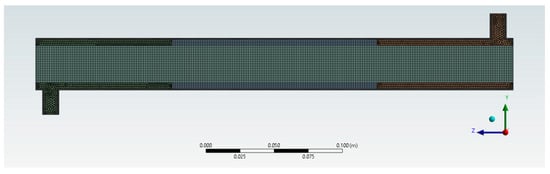

These findings obtained through the mesh independence test show that mesh 4 with an element size of 1.3 × 10−3 m is grid-independent with regard to the average axial velocity and outlet BaP concentration. Thus, mesh 4 with its 332,124 elements and 103,426 nodes was selected for the subsequent CFD simulations. The final mesh configuration is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Generated optimal mesh configuration.

3.2. CFD Simulation Results of the Photocatalytic Degradation of BaP in Annular Reactor

This section presents the results of the CFD simulations after geometry creation and the generation of the mesh. Using the model parameters for the solution method outlined earlier, convergence was achieved based on the initial conditions. Consequently, the researchers were now able to simulate the varying process variables, the results of which are essential in the detailed comprehension of the fluid flow, reaction kinetics, and transport phenomena involved in the process of degradation.

3.2.1. Velocity Profile

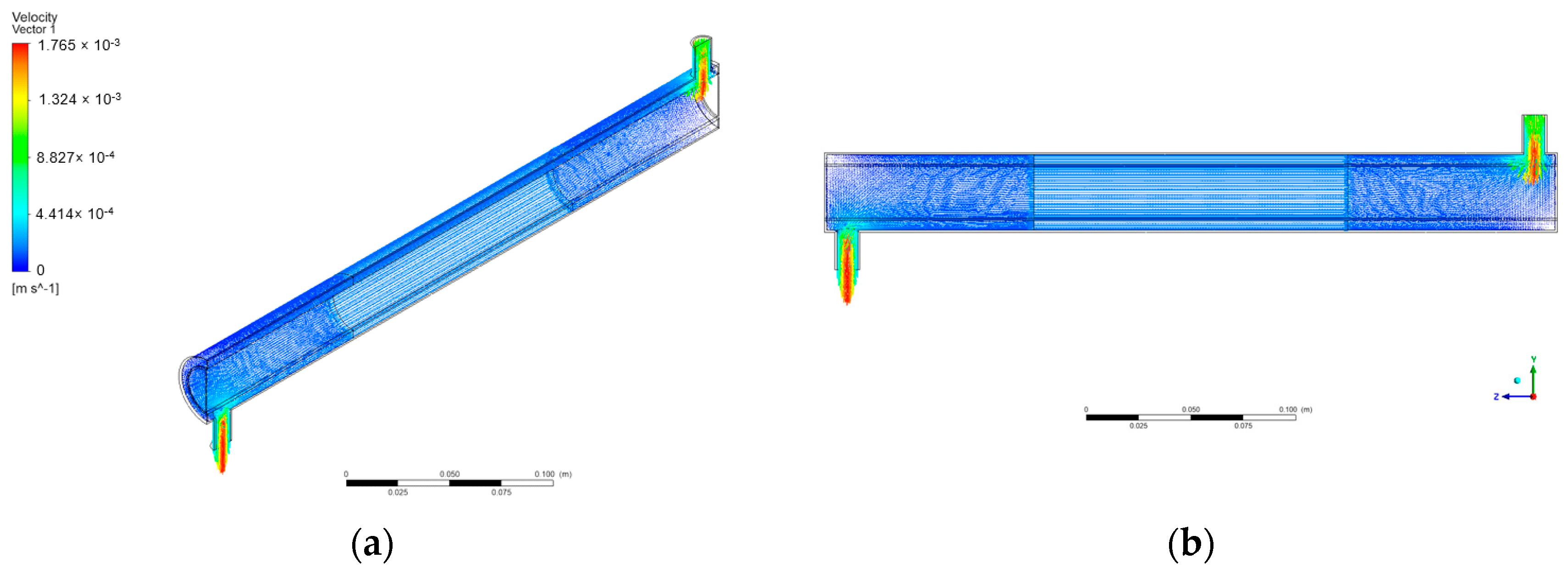

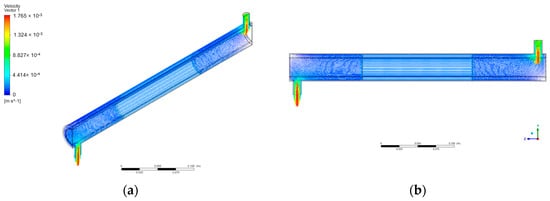

The water contaminated with BaP was defined as incompressible, Newtonian, isothermal, and had constant value physical properties. Figure 6 shows several orientations of the velocity vectors in the annular reactor with the inlet velocity set at 9.08 × 10−3 m/s.

Figure 6.

Velocity vectors in annular reactor: (a) isometric view; (b) axis-symmetric view.

As shown in Figure 6, the velocity vectors show a noticeable velocity gradient from the inlet tube to the annular space of the reactor. This follows the principle behind the continuity equation that, for a mass flow rate to be conserved, in this case, the velocity of the fluid in the annular space decreases accordingly with the sudden increase in the cross-sectional area. Also, the region in the center shows that the velocity is reduced compared to the regions near the inlet and outlet. This is due to the region being porous containing immobilized ZnO photocatalysts. The CFD simulation of Sozzi and Taghipour shows a similar velocity behavior in their reactor, with the annular flow velocity changing correspondingly over the reactor’s cross-sectional area with the flow direction’s 90-degree change from the inlet to the annulus [40].

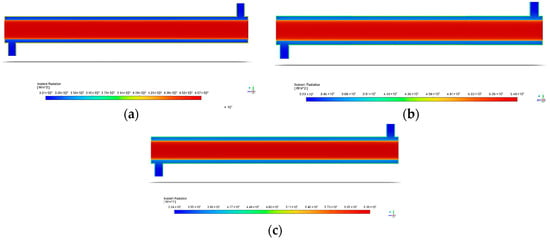

3.2.2. Radiation Profile

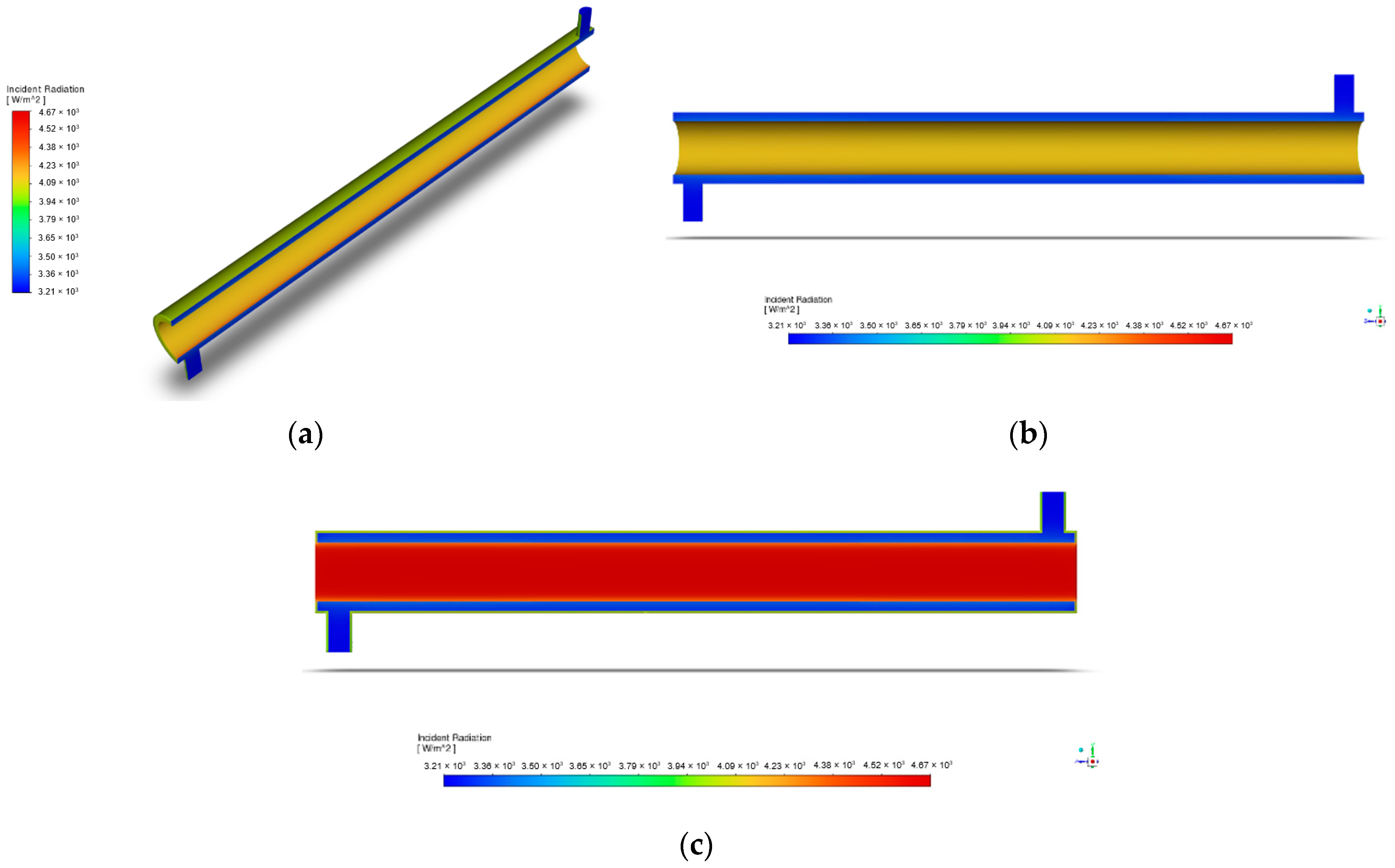

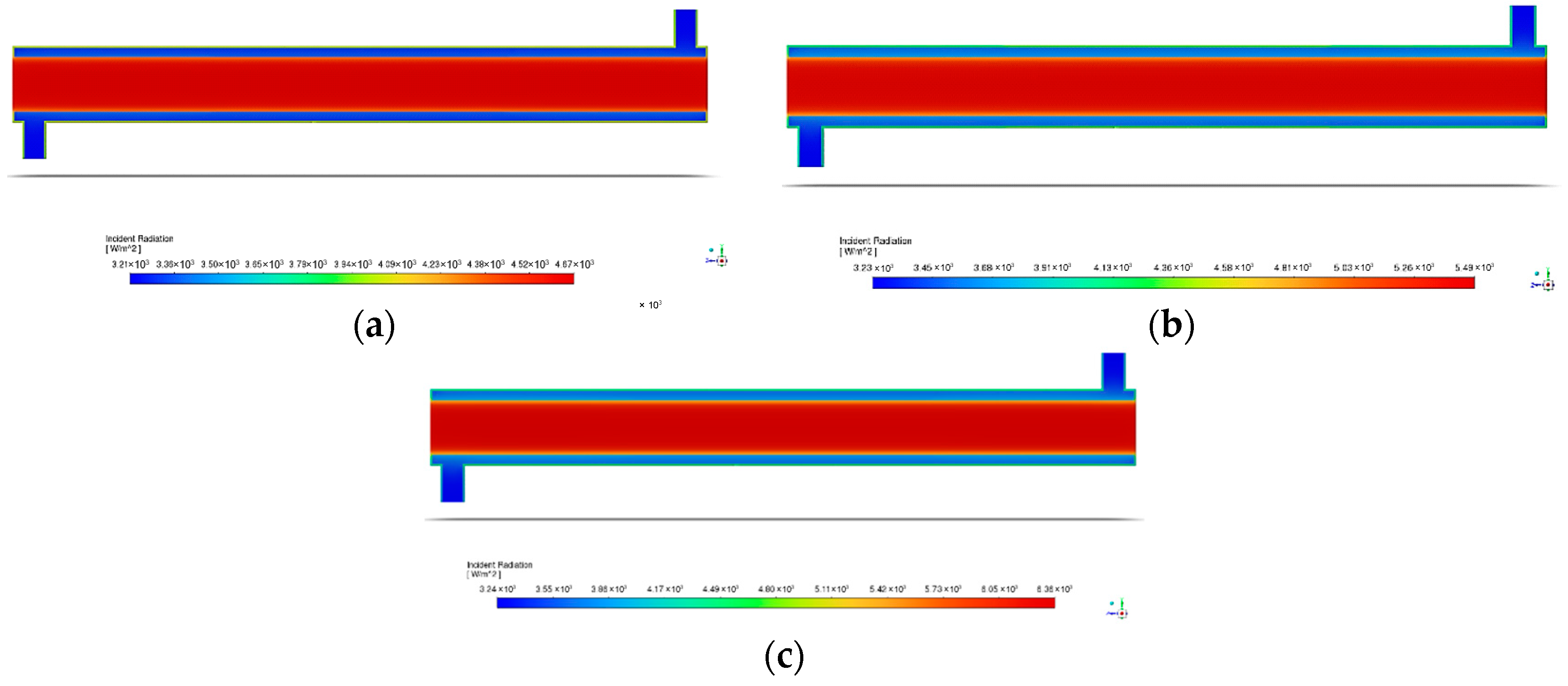

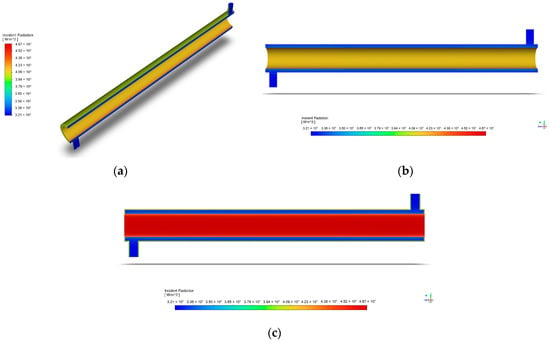

Crucial in the accurate modeling of the thermal radiation in the reactor, the radiation profile displays the distribution and intensity of radiative heat transfer within the computational domain. Figure 7 represents the radiation profile at the indicated initial condition of a light intensity with a value of 60 W/m2.

Figure 7.

Radiation profile of annular reactor: (a) isometric view; (b) axis-symmetric view; (c) incident radiation.

To explain, Figure 7 shows how the incoming radiant energy in the geometry is spread out through the collision of energy with surfaces or space within the computational domain. For instance, Figure 7c displays how the incident radiation is concentrated in the reactor’s inner region, where the UV lamp is situated. The opposite is said of the areas that are further from the light source, where a decrease in irradiance is observed. Such a figure that makes use of the Discrete Ordinates Model presents a similar radiation profile with the annular reactor of Moreno-SanSegundo et al. and is supported by the study of Barbosa et al. as a reliable model in the prediction of the radiation distribution inside a reactor [28,41].

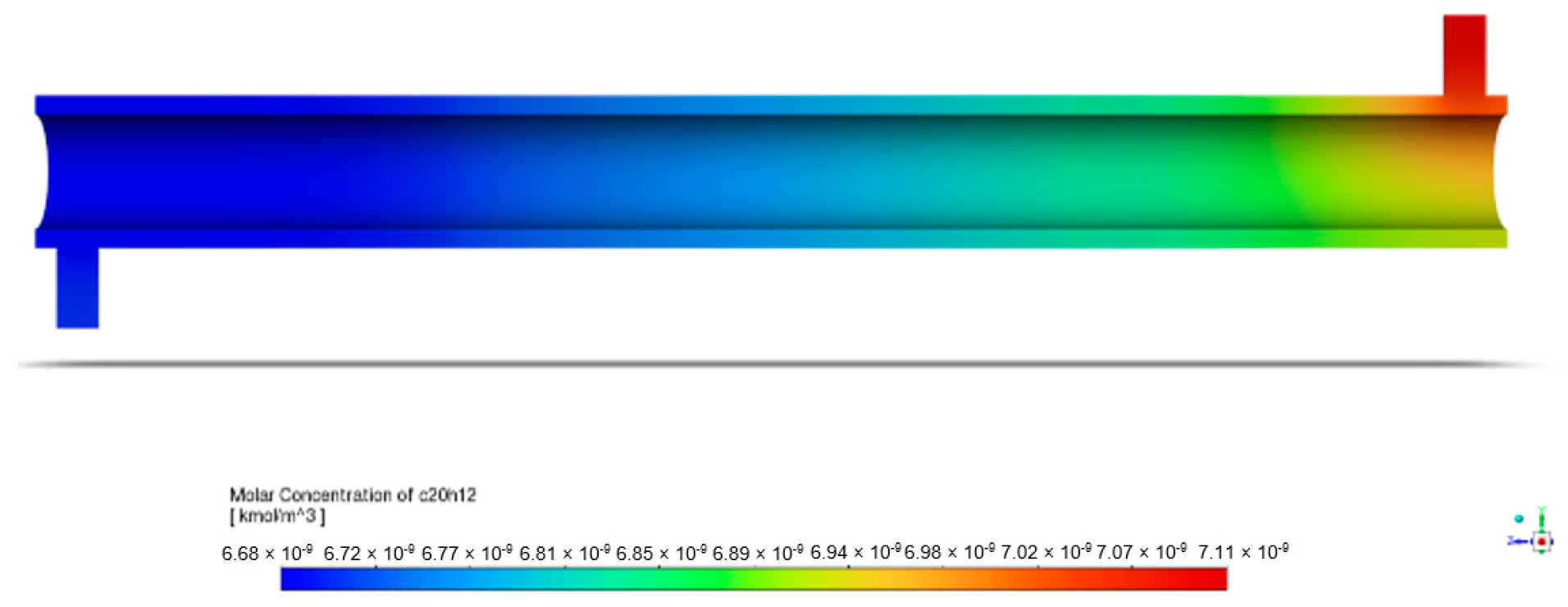

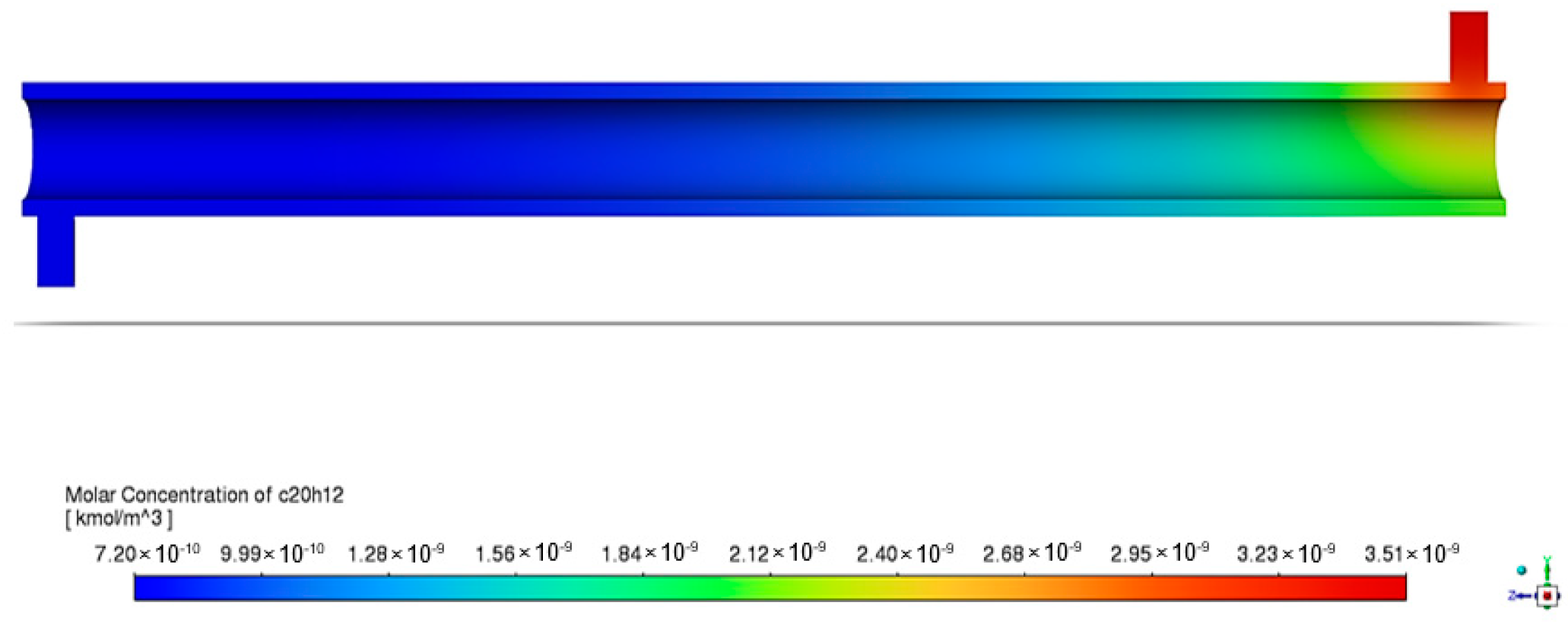

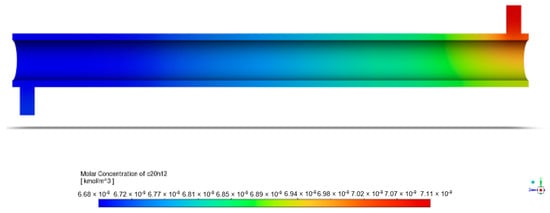

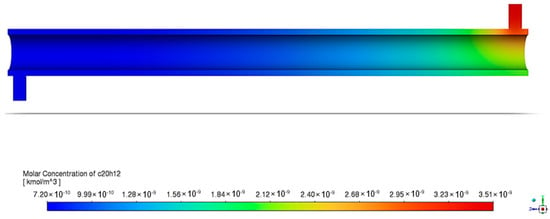

3.2.3. Molar Concentration Contours of BaP

The following figure is a graphical representation of the distribution of the species concentration within the system. This is crucial to identifying reaction zones and evaluating the reactor performance. With light and ZnO photocatalysts, BaP degradation in the annular reactor was observed under initial conditions of 1 ppm of BaP, 150 mm porous zone length, and light intensity of 60 W/m2, as represented by Figure 8. The inlet BaP had a molar concentration of kmol/m3.

Figure 8.

Contours of BaP molar concentration in annular reactor.

The figure’s gradient legend provides insight into the molar concentration contours within the annular reactor, with red indicating regions of high BaP concentration and blue representing areas of low BaP concentration. As the pollutant travels through the reactor, its molar concentration steadily decreases along the reactor length. By the time it reaches the outlet of the annular reactor, the molar concentration of BaP has diminished to kmol/m3. This gradual reduction illustrates the reactor’s efficiency in reducing the pollutant concentration, which was calculated to be 5.87%.

The apparent decrease starting at the inlet must be noted first. In addition to the ZnO photocatalysts positioned in the central part of the reactor, the UV radiation present throughout the entire reactor length also played a role in BaP mineralization. Chen et al. [42] documented the photodegradation of perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) under 254 nm UV light and 185 nm VUV light following pseudo-first order kinetics, observing a similar phenomenon. The presence of UV radiation throughout may possibly account for the changes in concentration within the reactor even before the fluid reached the annular space, where ZnO was immobilized.

To further validate the kinetics of the reaction, the following figures show an evident linear trend, with the pollutant BaP’s molar concentration decreasing over time. This signifies that photocatalytic degradation occurred. With that said, there are multiple studies that have reported the degradation of BaP and similar PAHs under similar conditions such as using UV light and ZnO photocatalysts [31,43,44,45].

BaP degradation was possible with the use of ZnO photocatalysts in the porous zone of the reactor. Zinc oxide photocatalysts have a wide bandgap energy, meaning they are capable of high-energy photon absorption such as in the ultraviolet range. As explained by Rajamanickam and Shanthi, the mechanism of photodegradation involving zinc oxide is initiated by its illumination with a radiation energy higher than the bandgap energy it possesses [46]. The irradiation then generates electrons and holes in the conduction band, which is shown in the equation below.

The electron–hole pair formed may either recombine within the bulk lattice or migrate to the surface, where they can react with adsorbates [47]. The trapping of holes initiates a reaction leading to the formation of hydroxyl radicals, as described by the following equation.

The electrons are then captured by dissolved oxygen, leading to the formation of superoxide ions.

The photocatalytic degradability by ZnO involves the oxidation of organic molecules (OM) through the hydroxyl radicals and holes. The reactions are as follows:

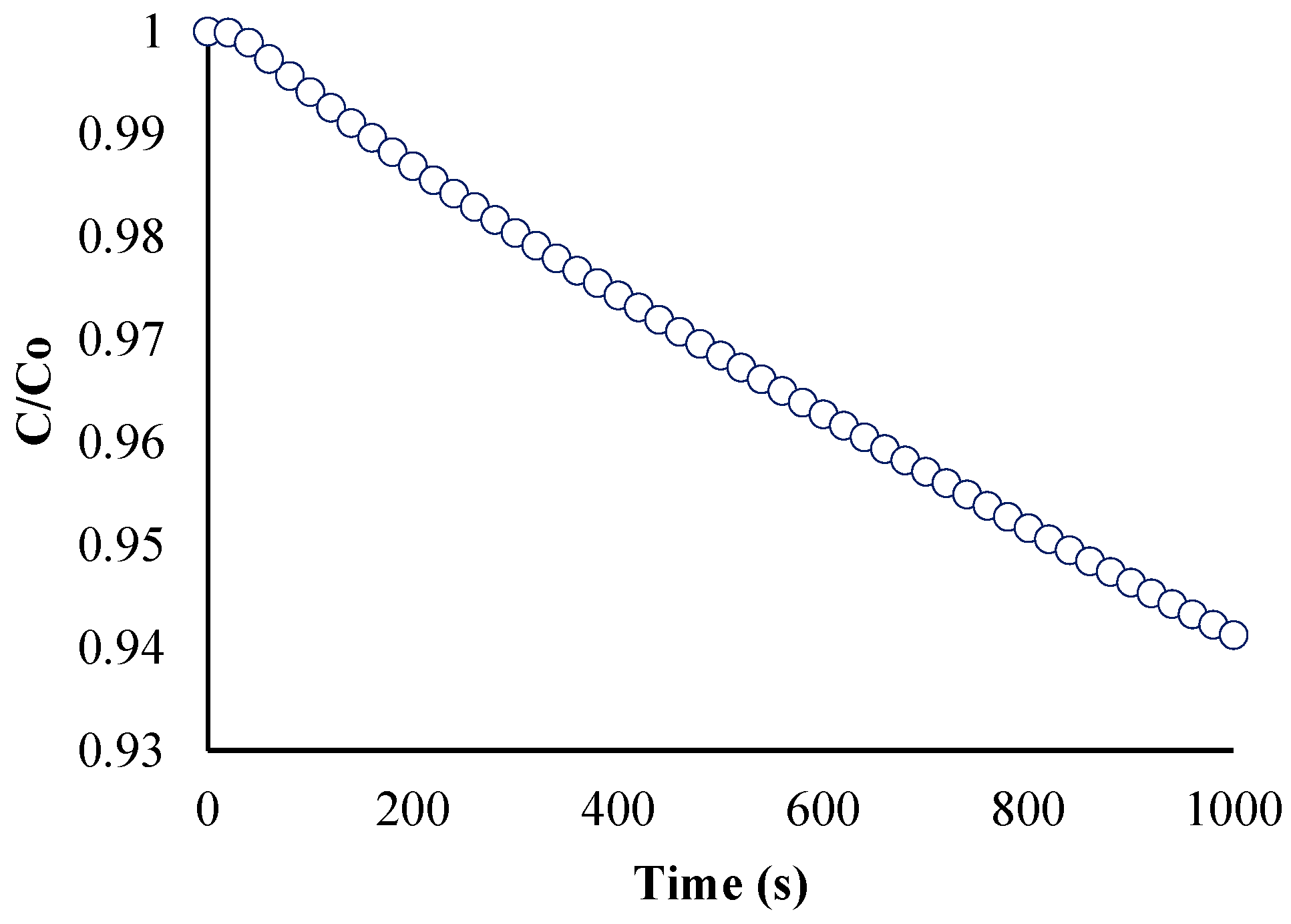

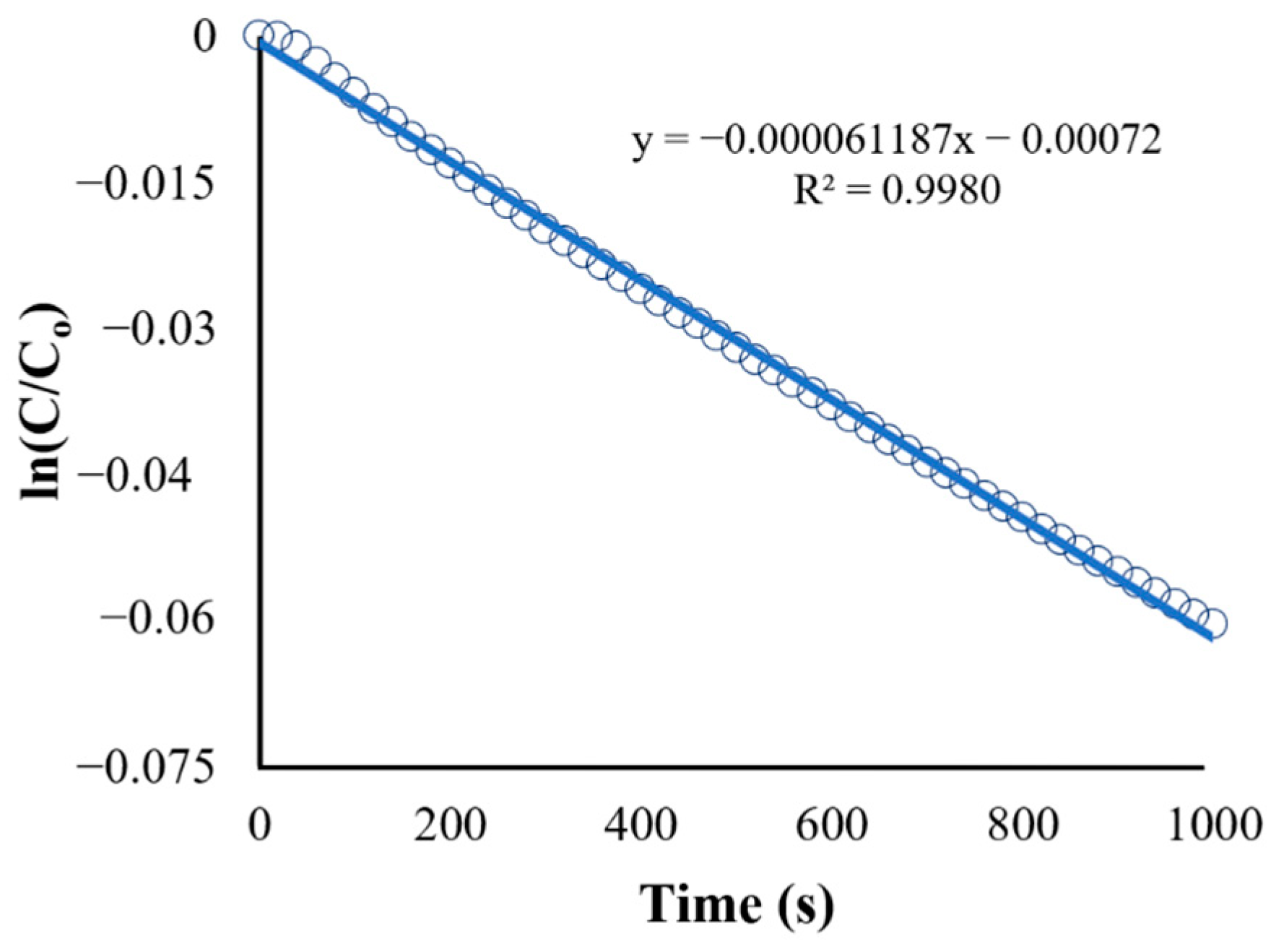

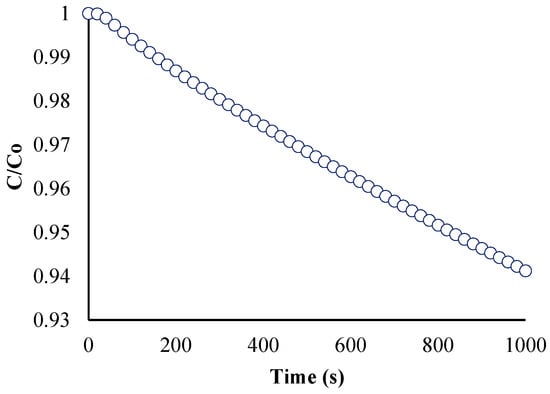

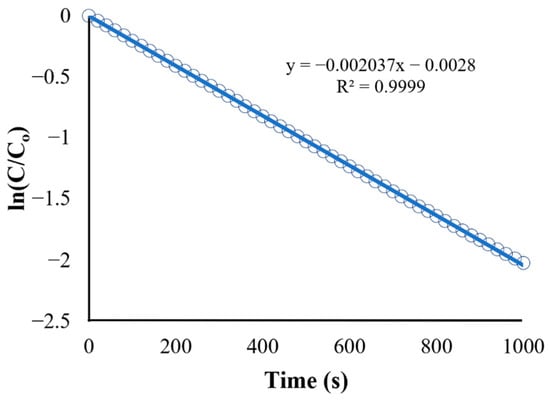

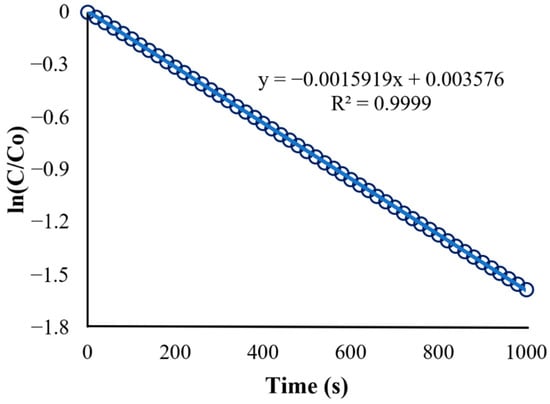

To confirm if the reaction order of the model is pseudo-first order, two plots were created. The first plot (Figure 9) is the ratio of the BaP concentration at time t to the initial BaP concentration (or C/C0) vs. time. This shows the gradual decrease in the concentration of BaP at the start of the reaction (t = 0) over time.

Figure 9.

Ratio of BaP concentration at time (t) to initial concentration versus time.

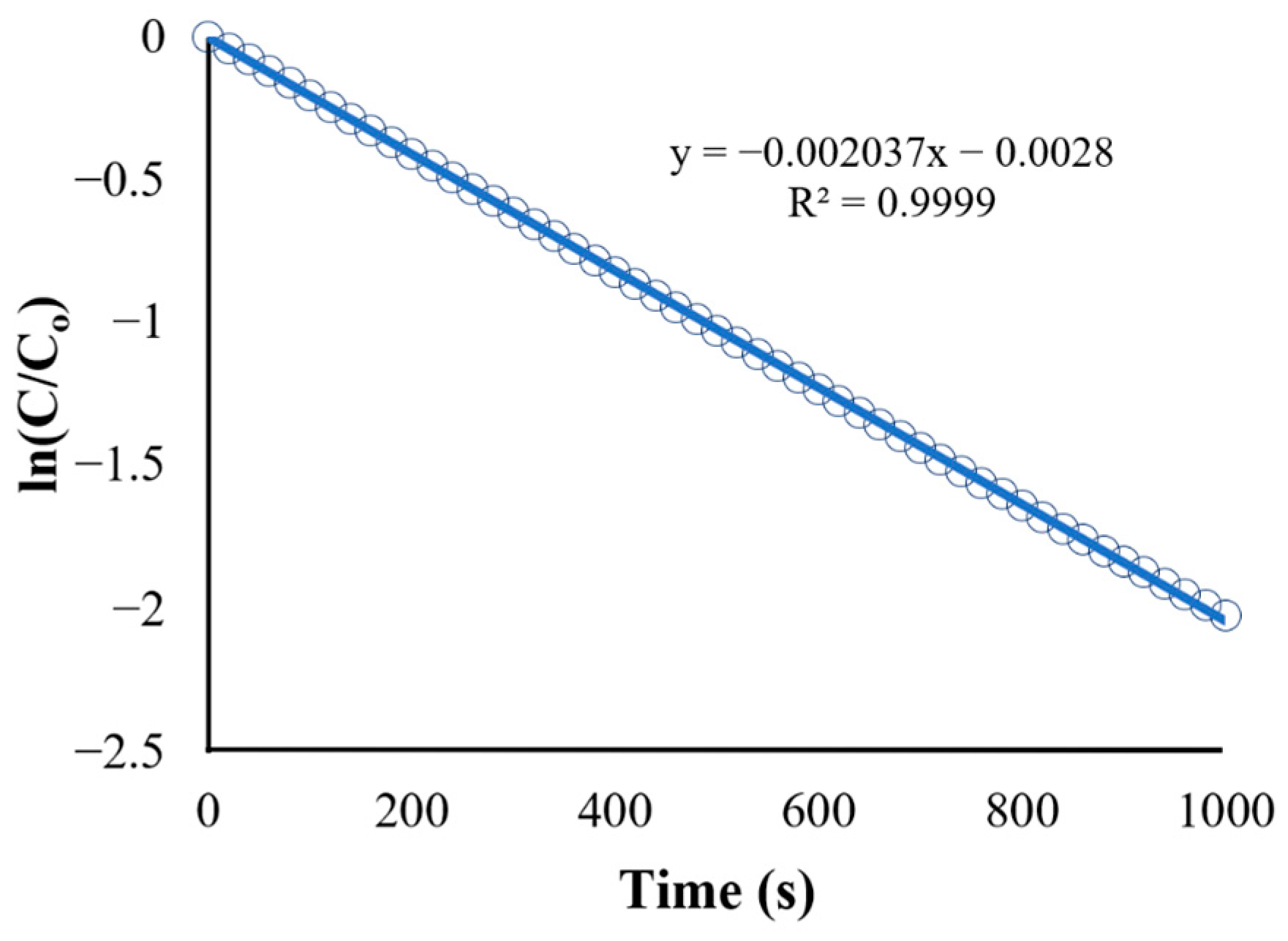

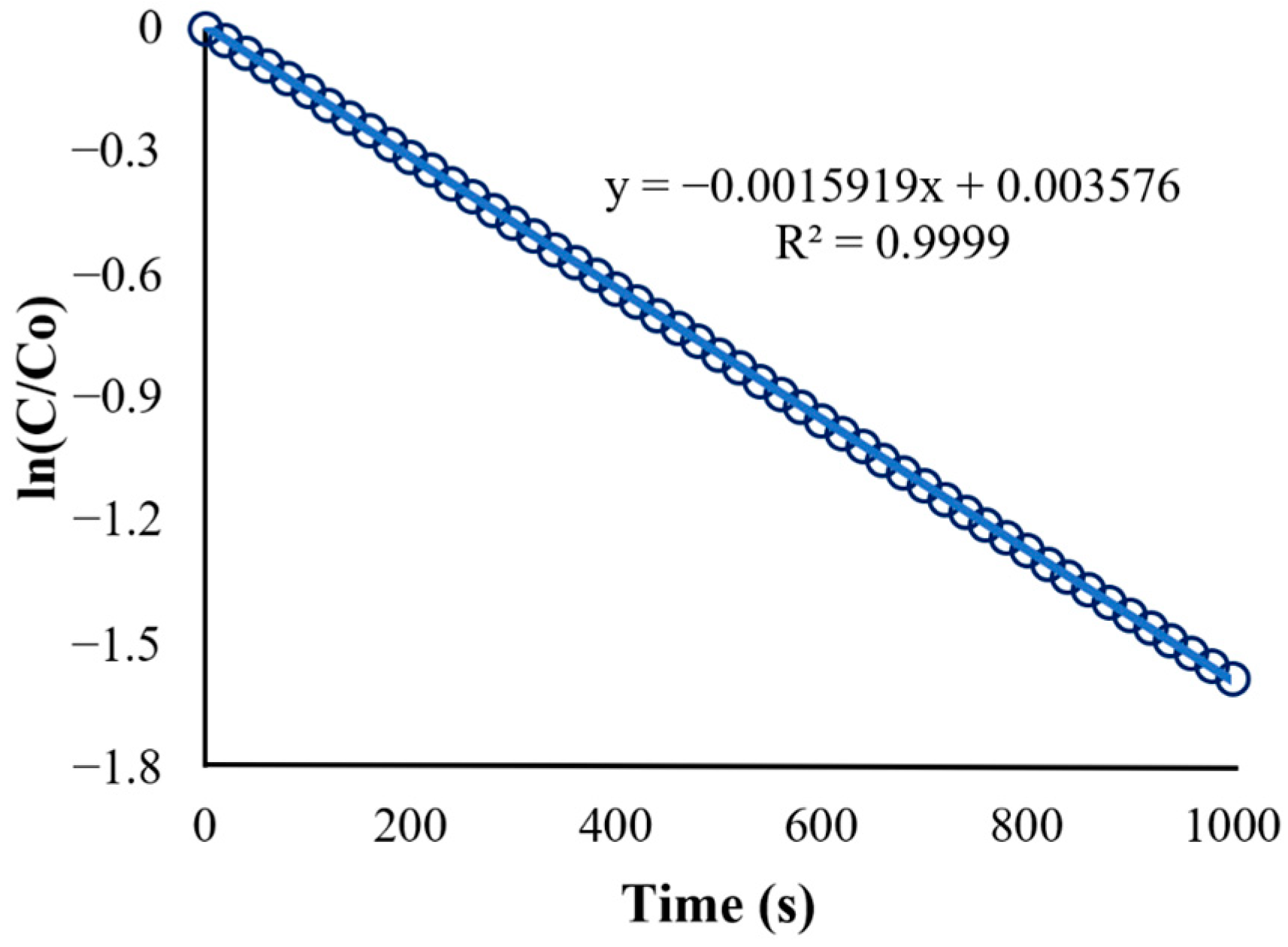

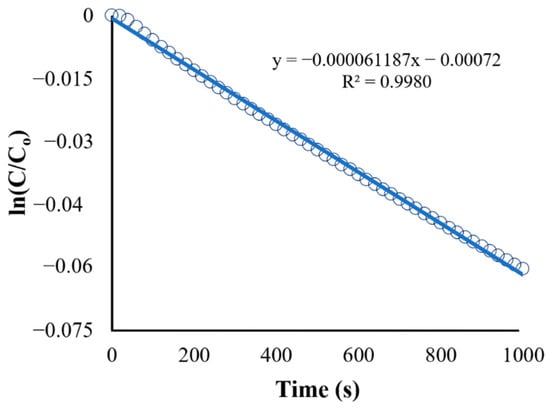

The second plot (Figure 10) is the natural logarithm of C/C0 (or ln[C/C0]) vs. time. It shows a straight-line plot used to determine the reaction rate constant (k) based on the integrated rate law for first-order reactions (Equation (13)), which is in the form of . The obtained equation from Figure 11 is as follows:

Figure 10.

Kinetics of BaP degradation using initial conditions.

Figure 11.

Kinetics of BaP degradation using initial condition obtained rate constant.

The slope of the straight-line equation corresponds to the reaction rate constant, which makes k = s−1 (R2 = 0.9980). A regression analysis was used to obtain the R-squared value of 0.998, and the model fits the first-order model. In fact, the first-order model is particularly suitable for low initial pollutant concentrations because the reaction rate is directly proportional to the concentration, as expected of first-order kinetics [48]. Other studies utilizing ZnO as a photocatalyst in the degradation of various organic pollutants have shown a similar fit for the reaction such as in the study of Sliem et al., wherein the photocatalyst ZnO in various media was evaluated for its performance in anthracene degradation. The paper showed that the correlation coefficient constant for the fitted line and the rate constants was graphically obtained for each photocatalyst in different media, and the concentration data plots produced a straight line, indicating that the photocatalytic degradation of anthracene follows a pseudo-first-order kinetic model [49].

The reaction rate constant obtained from the initial condition (k = s−1) was used as the new value for Kapp in the UDF. The result for the degradation of BaP using the obtained reaction rate constant is shown in Figure 11. Although both linearized plots have the same trend, the recorded observed reaction rate constant (k) using the adjusted UDF is equal to 0.002037 s−1, which is higher than the rate constant for the initial condition. The discrepancy between the rate constant values can be attributed to the use of more accurate values for parameters such as photocatalyst properties and pollutant characteristics in the simulation and adjusted UDF, leading to a more precise representation of the reaction kinetics and conditions in the CFD simulation.

Numerical solutions to fluid flow problems are approximations of the actual reactions being modeled. As CFD relies on equations of transport phenomena and heat transfer, it is susceptible to errors from domain discretization and modeling approaches. Discrepancies can occur between the actual flow and the mathematical models used, highlighting the importance of validating CFD results. As such, it is important to refer to similar studies to validate the accuracy of the simulation. Table 7 presents previous studies on the photocatalytic degradation of BaP for comparison.

Table 7.

Similar studies on BaP degradation.

As traditional statistical analysis such as ANOVA may only be applied to groups with multiple data points, such means could not be used for validation given that similar studies have not published their raw data as well. The lack of publicly available raw data has been challenging, as only approximately one-third of papers published are found to include these [55]. If there are remotely close studies, it is often true that they have manipulated other factors out of scope such as pH levels, which makes comparisons difficult, as there are additional variables to consider. Thus, it must be understood that the single data point per study (the reaction rate constants) cannot be analyzed traditionally due to a lack of within-group variability [56]. Hence, the conclusive validity is a result of a thorough subjective analysis backed by studies.

The analysis starts by first comparing the differences between this study and others. Previous studies paired zinc oxide with sunlight and did not make use of a continuous flow system. To give context, the common methodology for the first two studies in the table is that of a batch process because the setup used essentially utilizes a flask, with the solution containing a given PAH concentration and catalyst dose. The flask is then exposed to sunbeams with a set irradiation time. For every decided interval, the researchers take a certain amount of the solution from the flask exposed to a light source and have the concentration measured using either UV-VIS spectroscopy or gas chromatography–mass spectrometry.

With that said, the photocatalyst zinc oxide has a wide bandgap energy. This simply means that it requires a stronger light source for effective activation since the energy necessary to excite electrons from the valence band to the conduction band is higher [57]. Not only is a UV lamp a stable and controlled light source, but it also provides higher energy photons than sunlight, which varies throughout the day [58]. Also, it has been found that a continuous flow system benefits immobilized photocatalysts as it prevents the accumulation of intermediates within the solution, which may hinder photon travel [59]. For the third study that gave its kinetic rate constant and made use of titanium dioxide, the absorption capacity of zinc oxide is higher and may exhibit higher degradation efficiencies, as proven by the studies of Janotti and Van de Walle (2009), wherein they had stated that compared to TiO2, not only is the production cost of ZnO approximately 75% lower, it also has higher absorption efficacy across a large fraction of the light spectrum [60].

A study by Abebe also stated that the photocatalytic activity of ZnO may be higher than TiO2 with its higher absorption capacity [61]. Hence, the reaction rate constant obtained, which is 0.1222 min−1 (or 0.002037 s−1), being significantly higher than the reaction rate constants of the other studies is expected. The higher degradation efficiency naturally follows the same logic as it is dependent on the kinetic rate constant.

However, it is worth noting that ZnO photocatalysts may exhibit certain limitations that affect their performance in pollutant degradation, resulting in lower efficiencies compared to other photocatalysts. A possible issue is the high recombination rate of photogenerated electron–hole pairs, which reduces the availability of charge carriers for photocatalytic reactions [29,62]. Additionally, ZnO is also prone to photo-corrosion under UV light, leading to the dissolution of ZnO into Zn2+ ions, which decreases its stability and effectiveness [63,64]. Addressing these likely challenges—electron–hole recombination, photo-corrosion, and a limited surface area—is essential for improving ZnO. The need for various improvements shows the current novelty of using ZnO in photocatalytic degradation applications and, thus, the consideration of doping or coupling with other semiconductor photocatalysts may be points to consider in future studies.

3.3. Effects of Varying Process Variables on the Degradation Efficiency

Factors such as the pH of the solution, light intensity, radiation time, catalytic loading, and concentration of pollutants are some of the process variables that affect the degradation efficiency of photocatalytic systems [65]. The present study considers the effects of (1) the initial BaP concentration, (2) residence time, (3) surface irradiance intensity, and (4) length of the porous catalyst zone on the degradation capability of the UV/ZnO annular reactor.

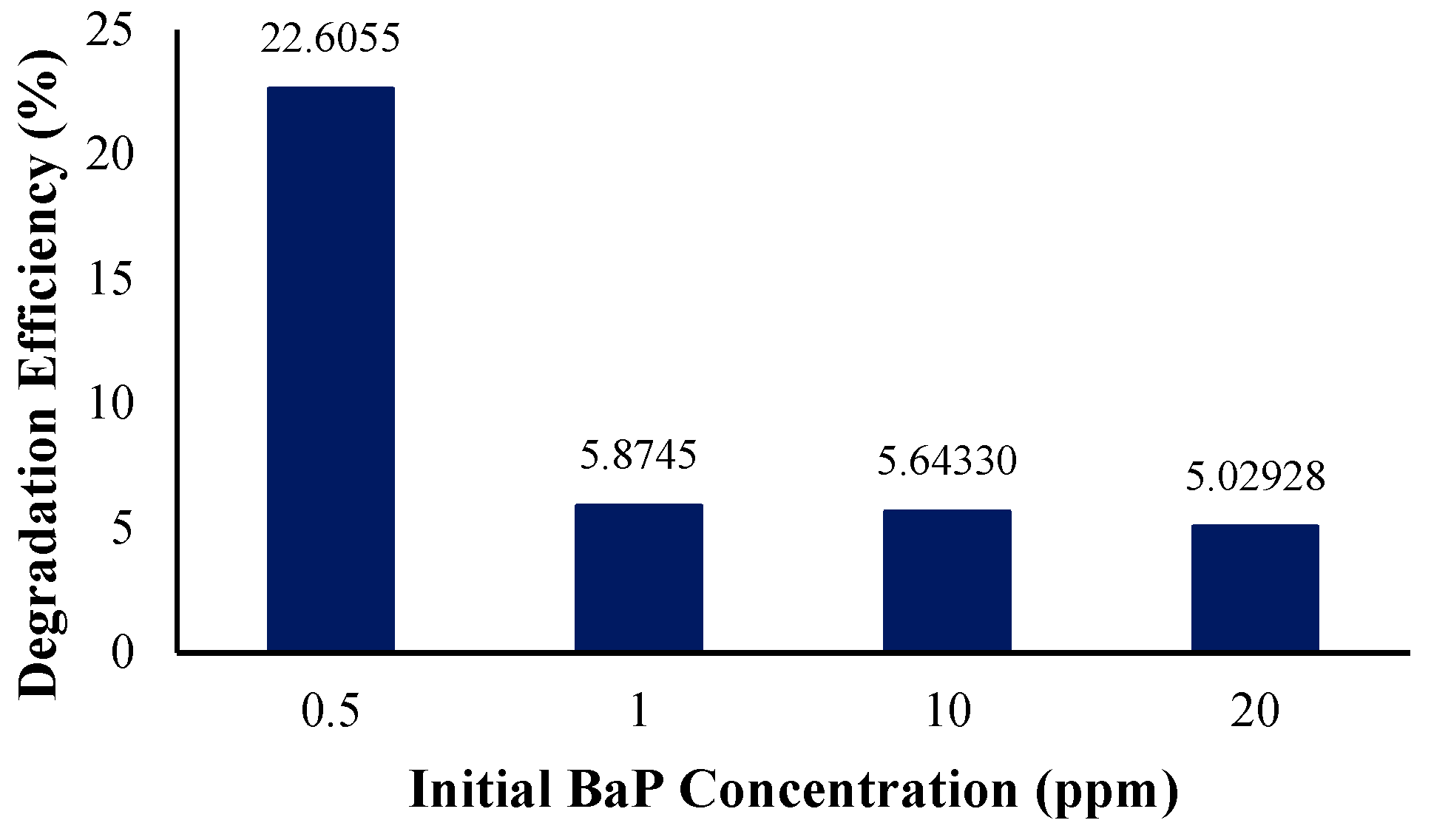

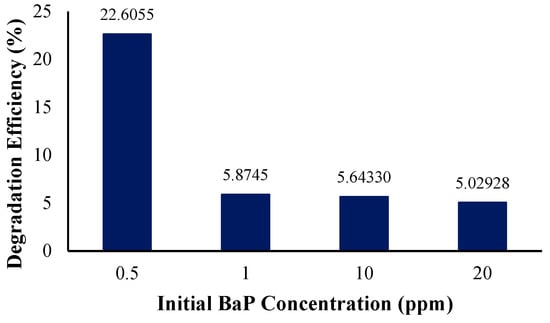

3.3.1. Effect of Initial BaP Concentration

In determining the effect of the initial pollutant concentration on the reaction rate and photocatalytic degradation, the initial BaP concentration was varied from 1 ppm to concentrations of 0.5, 10, and 20 ppm while keeping the other initial condition parameters the same (light intensity = 60 W/m2 and catalyst zone length = 150 mm).

Figure 12 shows the degradation efficiency at different initial BaP concentrations in the solution. It was determined that the efficiency decreases with an increase in the initial pollutant concentration, with the highest degradation efficiency recorded for the simulation with the lowest initial concentration of 0.5 ppm of BaP in the solution. At the lowest initial concentration of BaP, 22% of the BaP was removed from the solution. However, as the initial concentration of the target pollutant became more concentrated in the solution, the degradation efficiency and observed reaction rate constant (Table 8) decreased and did not vary significantly. This is similar to Rajamanickam and Shanthi’s study, wherein an increase in the initial concentration resulted in a decrease in degradation over the same period of time. This may be attributed to the high pollutant concentrations decreasing the path length of photons entering the solution. In other words, a significant amount of the light is absorbed by the pollutant rather than the photocatalyst, resulting in efficiency reduction [46]. Another study highlighting the effect of the initial concentration is that of Rachna et al., wherein the increase in the amount of PAH in the reaction mixture ultimately limited electron–hole formation or simply the process of photocatalytic degradation, as exemplified by the decreasing linear trend and negative slope with respect to the increase in concentration [66,67,68,69]. Several studies that show similar trends also report and conclude that as the number of PAHs exceeds a specific value, the number of active species causing degradation is less than that of the PAH molecules. It may then be concluded that higher concentrations do not simply benefit PAH degradation as soon as a certain threshold is surpassed [54,70,71].

Figure 12.

Degradation efficiency with variation in initial BaP concentration.

Table 8.

Observed rate constants for varying initial BaP concentration.

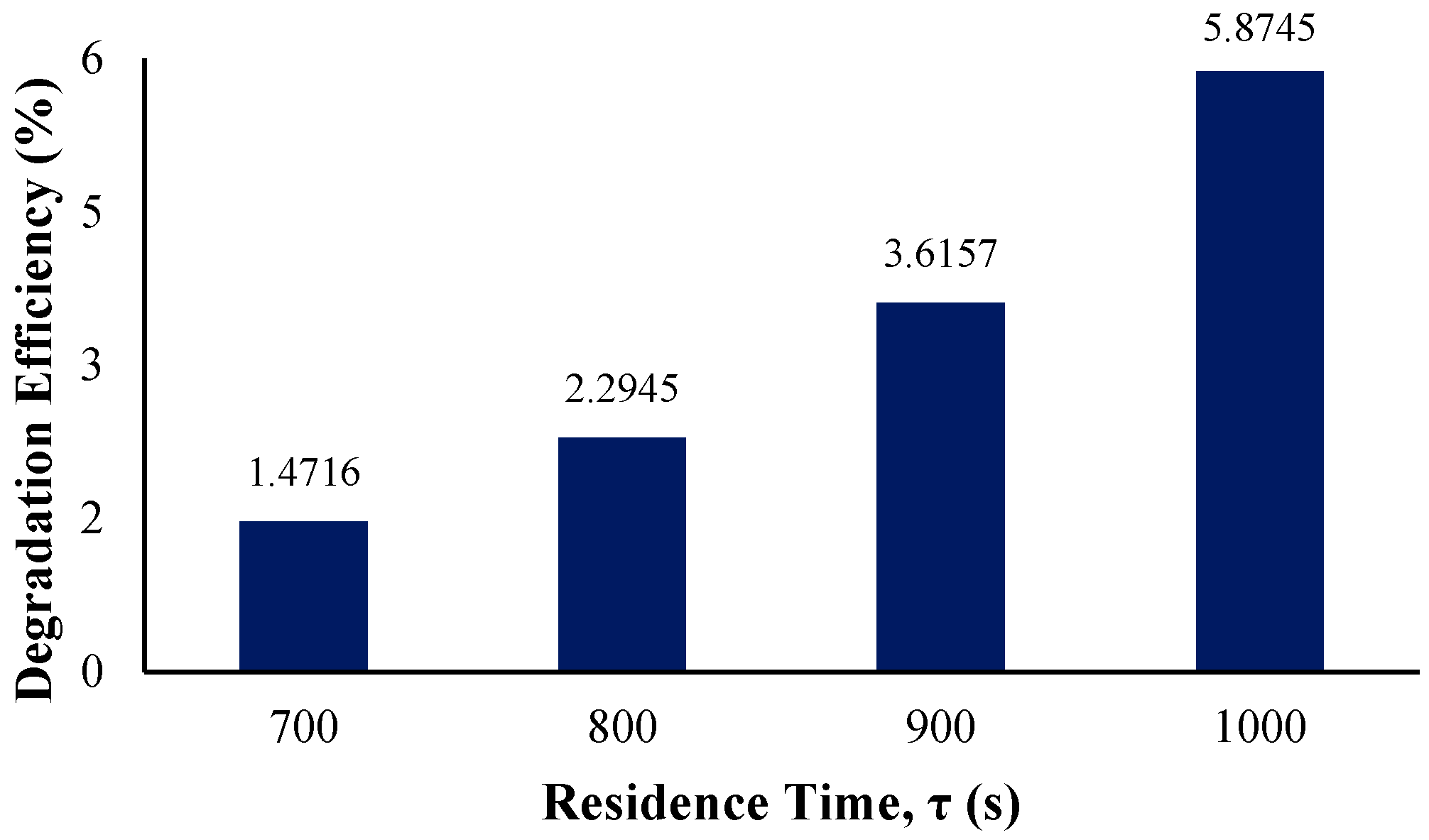

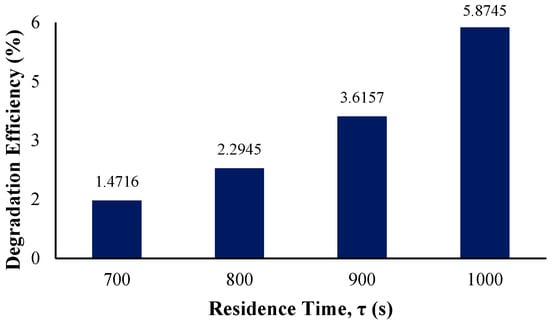

3.3.2. Effect of Residence Time

In determining the effect of the residence time on the photocatalytic degradation efficiency of BaP and reaction rate constant, an initial residence time of 700 s was observed with increments of 100 with the longest residence time being 1000 s. The figure below displays the degradation efficiency per residence time.

As observed from Figure 13, the more the residence time is lengthened, the higher the resulting overall degradation efficiency. Similarly to the study of phenol photodegradation by Wardhani et al., the enhanced degradation is simply due to the longer exposure of the pollutant with the photocatalyst surface and the increased irradiation time [72].

Figure 13.

Degradation efficiency with variation in residence time.

To explain, reactions occur with electromagnetic radiation exposure, UV light, to be specific, on the photocatalyst, resulting in activation. At a molecular level, the semiconductor ZnO generates electron–hole pairs that initiate the photocatalytic reaction with its UV absorption. These photogenerated electrons reduce the oxygen present on the photocatalysts’ exterior, which then results in the formation of superoxide radicals. Simultaneously, the holes oxidize water or hydroxide ions, producing hydroxyl radicals. These reactive oxygen species (ROS), such as hydroxyl radicals and superoxide radicals, can degrade BaP by mechanisms like hydrogen atom abstraction from its molecular structure or cleavage of the pollutant’s complex aromatic rings, leading to the formation of intermediates that are further broken down into water and carbon dioxide [51,73].

In simple terms, an increase in the residence time ensures that pollutant BaP remains in contact with the surface of photocatalyst ZnO long enough to allow for more interactions with ROS, enhancing the degradation efficiency, like in the study of Alam et al. on reactive yellow photodegradation, where degradation was enhanced with a longer residence time [74]. This extended exposure also provides opportunities for the complete breakdown of the intermediate products, which means less harmful by-product reduction [75]. This highlights that photocatalytic degradation obeys pseudo-first-order kinetics, which certainly means that increasing the residence time is adequate by itself to help the reaction approach completion. After all, higher-order kinetics would have a more complicated relationship between reaction completion and residence time with the consideration of the reaction rate depending on the concentration of two or more reactants and the dynamics of the photocatalytic degradation reaction [76].

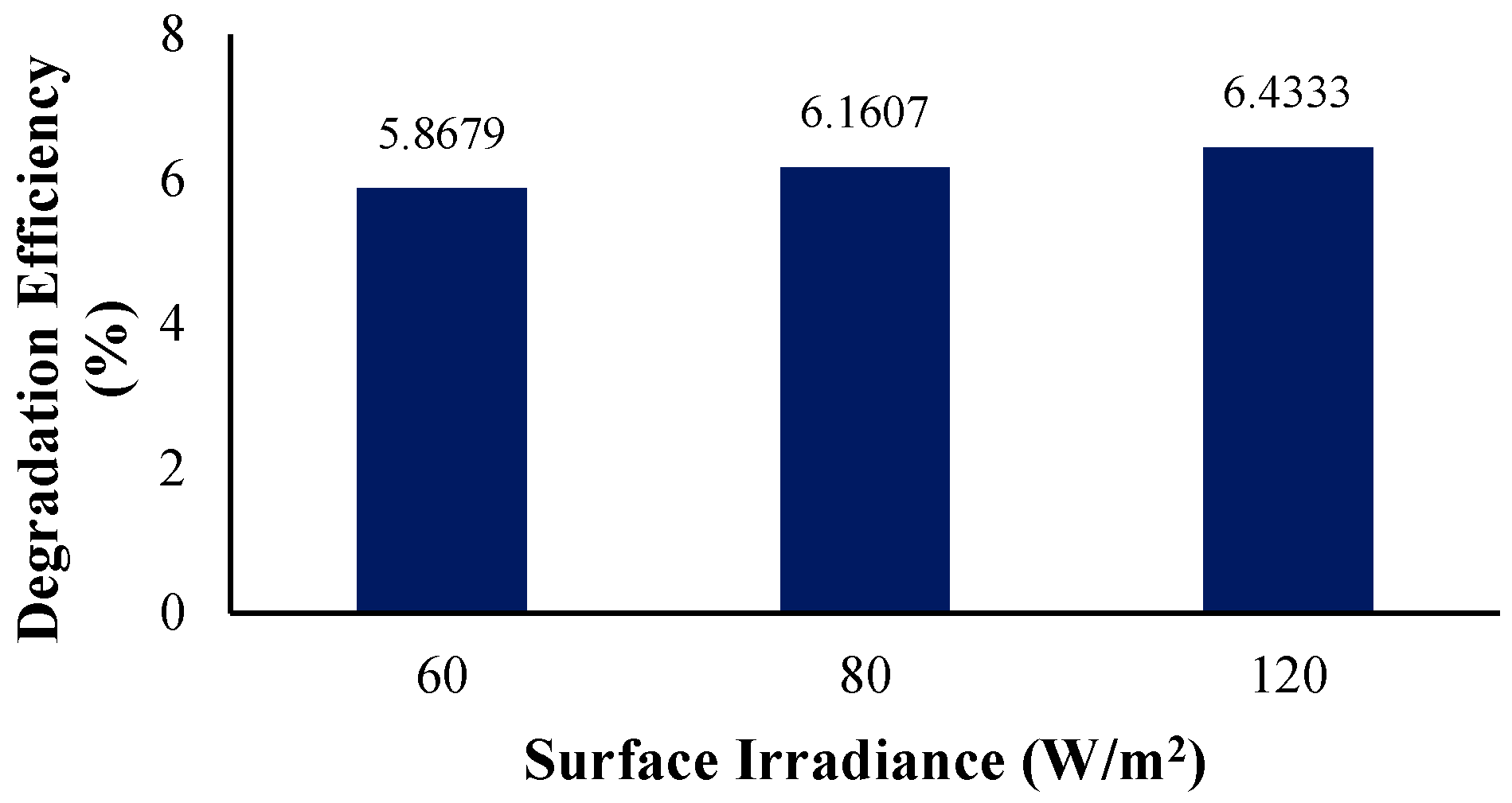

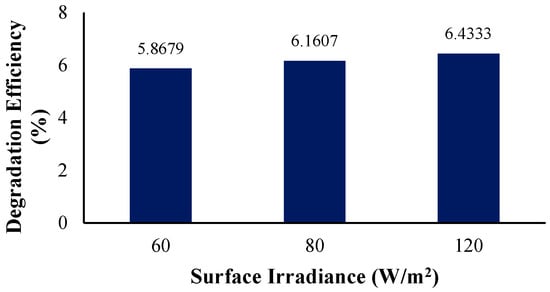

3.3.3. Effect of Surface Irradiance Intensity

To initiate a photocatalytic reaction, semiconductor catalysts such as zinc oxide need exposure to light. The importance of understanding the impact of surface irradiance lies in its influence on the efficient utilization of the photocatalyst, resulting in a maximized process of pollutant degradation. In this research, an initial surface irradiance of 60 W/m2 was used to facilitate the process. The irradiation intensity was varied only up to 120 W/m2. To clarify, previous studies have shown that while the reaction rate may linearly increase with rising light intensity, it becomes independent of surface irradiation beyond this range [77].

Figure 14 illustrates the incident radiation within the reactor at various light intensities. For all light intensities, the incident radiation decreases as the distance from the source increases. From Figure 15, the degradation efficiency increases with the rise in the surface irradiance intensity. This is possibly due to several reasons, with the first being that the UV light provided energy that excited the electrons to higher energy levels, causing better degradation of BaP [54,71]. To explain, the exposure to light caused ZnO to generate electron–hole pairs or the charge carriers that participate in redox reactions that result in pollutant degradation [42,78]. However, the increase in the degradation efficiency is rather small. This may be due to the rapid recombination of generated electron–hole pairs. As these pairs are generated, they are expected to migrate to the photocatalyst surface and participate in the required redox reaction, but there are cases where the pairs recombine before reaching the surface. Zinc oxide’s high bandgap can lead to a significant recombination of photogenerated charge carriers [79]. This ultimately reduces the number of charge carriers available, thereby limiting the increase in the photocatalytic degradation efficiency [80,81], as seen in Figure 15.

Figure 14.

Contour of the annular reactor inside with varying light intensities of (a) 60 W/m2; (b) 80 W/m2; and (c) 120 W/m2.

Figure 15.

Degradation efficiency with variation in surface irradiance intensity.

Table 9 below displays the rate constants obtained from simulating the differing irradiance intensities 60 W/m2, 80 W/m2, and 120 W/m2. Since the degradation efficiencies have shown an increasing trend, the rate constants also increase with the rise in the surface irradiance intensity. Overall, the lowest degradation efficiency, 5.87%, was observed for the lowest light intensity of 60 W/m2 with a rate constant of 6.3968 × 10−5 s−1. For 80 W/m2, the degradation percentage increased to 6.16% with a rate constant of 6.4304 × 10−5 s−1. On the other hand, at the highest light intensity of 120 W/m2, with a rate constant of 6.5975 × 10−5 s−1, the highest degradation efficiency of 6.43% was observed.

Table 9.

Observed rate constants for varying surface irradiance.

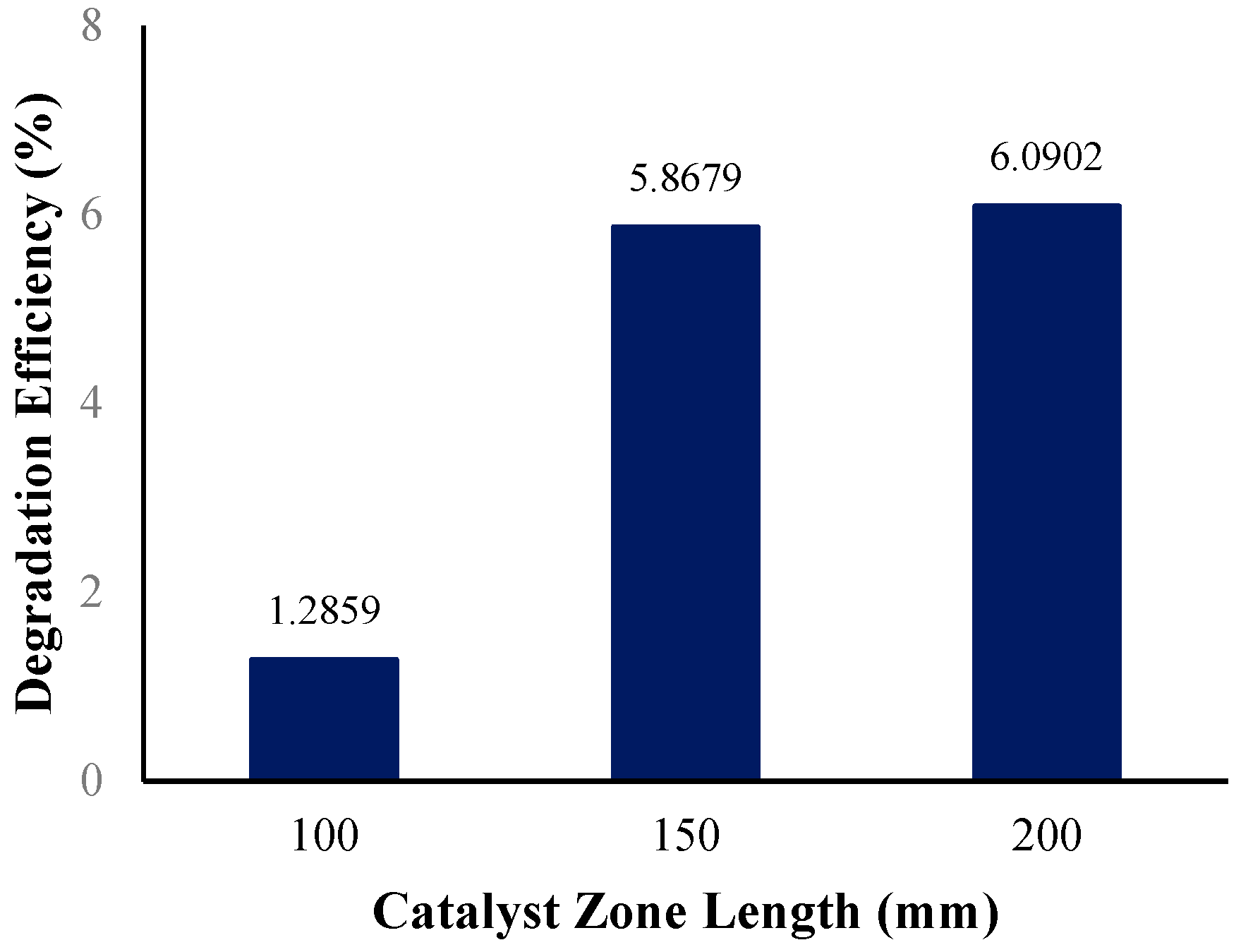

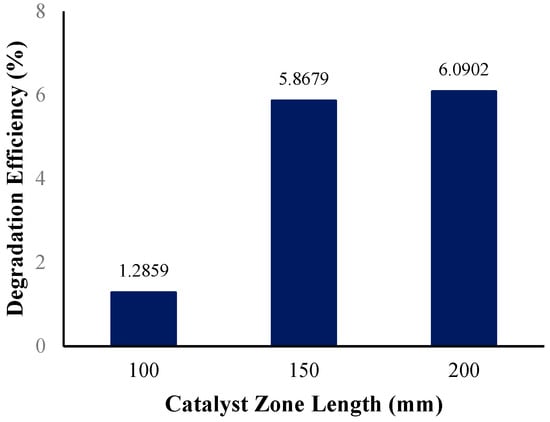

3.3.4. Effect of Catalyst Zone Length

The middle tube length holding the immobilized ZnO photocatalyst in the annular reactor was initially set to a length of 150 mm. In determining the effect of the catalyst zone length on the photocatalytic degradation efficiency, the reactor geometry of the annular reactor was modified twice to shorten the catalyst zone length to 100 mm and lengthen it to 200 mm. Figure 16 shows the photocatalytic degradation efficiencies at various catalyst zone lengths.

Figure 16.

Degradation efficiency with variation in catalyst zone length.

Catalyst loading (in this case, catalyst zone length) is among several process variables that significantly affect the degradation efficiency in photocatalysis systems [82]. The reactor with the longest catalyst zone (measuring 200 mm) had the highest degradation efficiency, at 6.09%, while the reactor with the shortest catalyst zone (measuring 100 mm) had the lowest degradation efficiency, at 1.29%. It can be said that the annular reactor with a 200 mm catalyst zone length performed better in reducing the BaP present in the solution compared to the reactors with a shorter catalyst zone. A longer catalyst zone in the annular reactor provides more active sites on the catalyst surface (more immobilized ZnO photocatalysts) for the fluid to flow, over which means a longer contact time for the fluid and catalysts. The increase in the number of active sites causes an increase in the number of absorbed photons producing many hydroxyl radicals, resulting in an increase in the degradation of the target pollutant [83]. Rate constants observed from the simulated operating conditions, summarized in Table 10, were obtained from the best-fitted line of the concentration vs. time plots (Supplementary Information).

Table 10.

Observed rate constants for varying catalyst zone length.

The observed trend in the effect of increasing the catalyst zone length on the BaP degradation efficiency in this study agrees with similar previous experimental studies, where an increase in the catalyst dose improved the degradation of target pollutants like PAHs, such as anthracene [49] naphthalene, phenanthrene [84], and BaP [50]. In the study by Mohammadi et al., the removal rate of BaP was improved by increasing the ZnO catalyst dose, but the catalyst dose also reached a limit or maximum dose, where the removal rate of BaP started to decrease. A possible reason for this decrease is due to the reduced surface area of the photocatalyst caused by the agglomeration of catalyst clusters, resulting in reduced light penetration [50]. This highlights the importance of determining the optimum catalyst dose or loading to be used, in this case, the tube length containing the immobilized ZnO photocatalysts, to achieve the best efficiency for the degradation of the target pollutant.

3.4. Degradation of BaP Under the Best Conditions

After determining the effects of the different process variables on the degradation efficiency of BaP, we have used the conditions from previous runs that resulted in the highest degradation efficiencies to analyze their effect on the overall photocatalytic degradation. It must be noted that these are not equated to optimum conditions, as higher or lower values based on the trends observed per variable may result in better degradation efficiencies. The parameters used are summarized in Table 11.

Table 11.

Best conditions observed for process variables.

Figure 17 shows the decrease in the BaP concentration as it flows along the length of the annular reactor. The significant improvement in the overall degradation is apparent, as displayed by Figure 18 and its linearity. The reaction rate constant at the chosen best conditions is , which has a higher value than previous runs that observed the effects of each process variable. This means that the reaction proceeds more quickly under specified conditions; hence, the degradation efficiency is significantly higher at 79.44% than the degradation efficiency for the previous setup.

Figure 17.

BaP molar concentration contour in annular reactor under optimum conditions.

Figure 18.

Kinetics of BaP degradation under optimum conditions.

This significant increase in efficiency can be attributed to the low fluid inlet velocity and longer residence time causing less radial mixing, which affects mass transfer. Then, the small initial concentration of BaP may prevent unnecessary photon travel hindrances, while the high surface irradiance for increased photon absorption, enhanced reaction rate, and, finally, the catalyst zone length also result in an increased residence time, allowing for better contact time and a complete reaction [85].

4. Conclusions

This study investigates the photocatalytic degradation of the persistent and carcinogenic benzo[a]pyrene with immobilized ZnO photocatalysts using CFD modeling. We developed an annular reactor with a porous domain of immobilized ZnO photocatalysts to determine the impact of varying process variables such as the initial BaP concentration, residence time, surface irradiance intensity, and catalyst zone length on the overall degradation efficiency.

From testing the axial velocity and outlet BaP concentration, the mesh with an element size of 1.3 × 10−3 m was found to be grid-independent regarding the average axial velocity and outlet BaP concentration. This mesh, comprising 103,426 nodes and 332,124 mesh elements, was used in the CFD simulations. The models, physical properties, boundary conditions (inlet, outlet, and wall conditions), solver settings, and convergence requirements were then established in the CFD model.

We have varied the parameters from the initial conditions while keeping other variables constant. The simulation’s accuracy was validated through a thorough subjective analysis backed by similar experimental studies found previously. The initial BaP concentration was inversely proportional to the degradation efficiency, with the highest percentage degradation of BaP observed when the initial pollutant concentration was at its lowest, which was 0.5 ppm for this study. As for the residence time, an increase in its value ensures that the pollutant BaP remains in contact with the photocatalyst, which is necessary to allow chances for a more complete breakdown, preventing the formation of by-products. This effect is conclusive when involving pseudo-first-order kinetics, unlike in higher orders, where more than two reactants are involved, and the reaction dynamics may be entirely different. Furthermore, it was found that the surface irradiance intensity is directly correlated with the reaction rate and degradation efficiency. Of the three light intensities tested, the highest light intensity simulated, 120 W/m2, yielded the highest BaP degradation, consistent with studies showing that pollutant degradation improves with increased electron excitation. Extending the catalyst zone length from an initial length of 150 mm to 200 mm also improved the degradation efficiency due to longer residence times.

In summary, the highest degradation percentage occurred at the best conditions simulated with the highest surface irradiance of 120 W/m2, longest catalyst zone length of 200 mm, longest residence time of 1000 s, and smallest initial BaP concentration of 0.5 ppm. The photocatalytic degradation under the best conditions selected was able to achieve a degradation efficiency of 79.44%, almost thirteen times more than that of the degradation efficiency under the initial conditions. Thus, to ensure substantial pollutant degradation using an immobilized ZnO as a photocatalyst, the following must be considered: a low initial pollutant concentration, sufficient residence time, a high surface irradiance intensity, and an extended catalyst zone. The CFD model developed could serve as a starting point in future pilot plant-scale studies, as this would significantly reduce costs in building physical reactors.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/fluids10020051/s1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.R.A. and M.L.B.; methodology, M.L.B.; software, M.L.B.; validation, H.R.A., M.L.B. and J.A.M.; formal analysis, H.R.A.; investigation, H.R.A.; resources, H.R.A., M.L.B. and J.A.M.; data curation, M.L.B.; writing—original draft preparation, H.R.A.; writing—review and editing, H.R.A.; supervision, J.A.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by Mapua University.

Data Availability Statement

The data are contained within the article or Supplementary Materials.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our sincerest appreciation to Mapua University for the use of the computer laboratory facilities and the software.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of the data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Abdel-Shafy, H.I.; Mansour, M.S.M. A Review on Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons: Source, Environmental Impact, Effect on Human Health and Remediation. Egypt. J. Pet. 2016, 25, 107–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.H.; Jahan, S.A.; Kabir, E.; Brown, R.J.C. A Review of Airborne Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) and Their Human Health Effects. Environ. Int. 2013, 60, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pelizzetti, E.; Minero, C.; Carlin, V.; Borgarello, E. Photocatalytic Soil Decontamination. Chemosphere 1992, 25, 343–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, M.J.; Soares, S.A.R.; Santos, I.D.F.; Pepe, I.M.; Teixeira, L.R.; Pereira, L.G.; Silva, L.B.A.; Celino, J.J. Optimization of the Photocatalytic Degradation Process of Aromatic Organic Compounds Applied to Mangrove Sediment. Heliyon 2020, 6, e05163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, H.T.; Phan Thi, L.A.; Dao Nguyen, N.H.; Huang, C.W.; Le, Q.V.; Nguyen, V.H. Tailoring Photocatalysts and Elucidating Mechanisms of Photocatalytic Degradation of Perfluorocarboxylic Acids (PFCAs) in Water: A Comparative Overview. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2020, 95, 2569–2578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, R.; Zhang, D.; Mo, Y.; Song, L.; Brewer, E.; Huang, X.; Xiong, Y. Photocatalytic Activity of Polymer-Modified ZnO under Visible Light Irradiation. J. Hazard. Mater. 2008, 156, 80–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ong, C.B.; Ng, L.Y.; Mohammad, A.W. A Review of ZnO Nanoparticles as Solar Photocatalysts: Synthesis, Mechanisms and Applications. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 81, 536–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litton, C.W.; Reynolds, D.C.; Collins, T.C. Zinc Oxide Materials for Electronic and Optoelectronic Device Applications; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011; ISBN 9780470519714. [Google Scholar]

- Nur, H.; Misnon, I.I.; Wei, L.K. Stannic Oxide-Titanium Dioxide Coupled Semiconductor Photocatalyst Loaded with Polyaniline for Enhanced Photocatalytic Oxidation of 1-Octene. Int. J. Photoenergy 2007, 2007, 098548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klenov, O.P.; Noskov, A.S. Computational Fluid Dynamics in the Development of Catalytic Reactors. Catal. Ind. 2011, 3, 331–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, V.H.; Smith, S.M.; Wantala, K.; Kajitvichyanukul, P. Photocatalytic Remediation of Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs): A Review. Arab. J. Chem. 2020, 13, 8309–8337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janczarek, M.; Kowalska, E. Computer Simulations of Photocatalytic Reactors. Catalysts 2021, 11, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavel, M.; Anastasescu, C.; State, R.N.; Vasile, A.; Papa, F.; Balint, I. Photocatalytic Degradation of Organic and Inorganic Pollutants to Harmless End Products: Assessment of Practical Application Potential for Water and Air Cleaning. Catalysts 2023, 13, 380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iervolino, G.; Zammit, I.; Vaiano, V.; Rizzo, L. Limitations and Prospects for Wastewater Treatment by UV and Visible-Light-Active Heterogeneous Photocatalysis: A Critical Review. Top. Curr. Chem. 2020, 378, 225–264. [Google Scholar]

- Mosleh, S.; Ghaedi, M. Photocatalytic Reactors: Technological Status, Opportunities, and Challenges for Development and Industrial Upscaling. Interface Sci. Technol. 2021, 32, 761–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.Y.; Yuan, L.; Li, S.H.; Tang, Z.R.; Xu, Y.J. One-Dimensional Copper-Based Heterostructures toward Photo-Driven Reduction of CO2 to Sustainable Fuels and Feedstocks. J. Mater. Chem. A Mater. 2019, 7, 8676–8689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza, J.A.; Lee, D.H.; Kang, J.H. Comparative Analysis of the Photocatalytic Removal of Methylene Blue and Pyrene on TiO2 and WO3/TiO2 Particles. Desalination Water Treat. 2020, 200, 351–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Yang, M.Q.; Liu, S.; Sun, Y.; Xu, Y.J. Waltzing with the Versatile Platform of Graphene to Synthesize Composite Photocatalysts. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 10307–10377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldos, H.I.; Zouari, N.; Saeed, S.; Al-Ghouti, M.A. Recent Advances in the Treatment of PAHs in the Environment: Application of Nanomaterial-Based Technologies. Arab. J. Chem. 2022, 15, 103918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, S.; Kjellerup, V.; Davis, A.P. Occurrence and Removal of Polychlorinated Biphenyls (PCBs) in Urban Stormwater. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Maryland, College Park, MD, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekanem, A.N.; Osabor, V.N.; Ekpo, B.O. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) Contamination of Soils and Water around Automobile Repair Workshops in Eket Metropolis, Akwa Ibom State, Nigeria. SN Appl. Sci. 2019, 1, 447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Polynuclear Aromatic Hydrocarbons. In Guidelines for Drinking-Water Quality; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 1998; Volume 2, pp. 123–152. [Google Scholar]

- Ekere, N.R.; Yakubu, N.M.; Oparanozie, T.; Ihedioha, J.N. Levels and Risk Assessment of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Water and Fish of Rivers Niger and Benue Confluence Lokoja, Nigeria. J. Environ. Health Sci. Eng. 2019, 17, 383–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grmasha, R.A.; Abdulameer, M.H.; Stenger-Kovács, C.; Al-sareji, O.J.; Al-Gazali, Z.; Al-Juboori, R.A.; Meiczinger, M.; Hashim, K.S. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in the Surface Water and Sediment along Euphrates River System: Occurrence, Sources, Ecological and Health Risk Assessment. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2023, 187, 114568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, X.; Tang, R.; Xiong, S.; Zheng, J.; Li, L.; Zhou, Z.; Gong, D.; Deng, Y.; Su, L.; Liao, C. Application of Natural Minerals in Photocatalytic Degradation of Organic Pollutants: A Review. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 812, 152434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sustainable Development Goals|United Nations Development Programme. Available online: https://www.undp.org/sustainable-development-goals (accessed on 4 February 2024).

- Duran, J.E.; Mohseni, M.; Taghipour, F. Modeling of Annular Reactors with Surface Reaction Using Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD). Chem. Eng. Sci. 2010, 65, 1201–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-SanSegundo, J.; Casado, C.; Marugán, J. Enhanced Numerical Simulation of Photocatalytic Reactors with an Improved Solver for the Radiative Transfer Equation. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 388, 124183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nourizade, M.; Rahmani, M.; Javadi, A. Simulation of a Photocatalytic Reactor Using Finite Volume and Discrete Ordinate Method: A Parametric Study. Amirkabir J. Mech. Eng. 2021, 53, 573–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camera-Roda, G.; Loddo, V.; Palmisano, L.; Parrino, F. Guidelines for the Assessment of the Rate Law of Slurry Photocatalytic Reactions. Catal. Today 2017, 281, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rachna; Rani, M.; Shanker, U. Sunlight Mediated Improved Photocatalytic Degradation of Carcinogenic Benz[a]Anthracene and Benzo[a]Pyrene by Zinc Oxide Encapsulated Hexacyanoferrate Nanocomposite. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2019, 381, 111861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devipriya, B.; Mohanan, S.; Surenjan, A. CFD Modelling of an Immobilised Photocatalytic Reactor for Phenol Degradation. Water Sci. Technol. 2023, 88, 2121–2135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, J.; Bansal, A. Photocatalytic Degradation in Annular Reactor: Modelization and Optimization Using Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) and Response Surface Methodology (RSM). J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2013, 1, 398–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, J.; Bansal, A. CFD Simulations of Immobilized-Titanium Dioxide Based Annular Photocatalytic Reactor: Model Development and Experimental Validation. Indian J. Chem. Technol. 2016, 22, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benzo[a]Pyrene. Available online: https://webbook.nist.gov/cgi/cbook.cgi?ID=50-32-8 (accessed on 8 July 2024).

- Document Display|NEPIS|US EPA. Available online: https://nepis.epa.gov/Exe/ZyNET.exe/P100SOKG.txt?ZyActionD=ZyDocument&Client=EPA&Index=2016%20Thru%202020&Docs=&Query=%28density%29%20OR%20FNAME%3D%22P100SOKG.txt%22%20AND%20FNAME%3D%22P100SOKG.txt%22&Time=&EndTime=&SearchMethod=1&TocRestrict=n&Toc=&TocEntry=&QField=&QFieldYear=&QFieldMonth=&QFieldDay=&UseQField=&IntQFieldOp=0&ExtQFieldOp=0&XmlQuery=&File=D%3A%5CZYFILES%5CINDEX%20DATA%5C16THRU20%5CTXT%5C00000005%5CP100SOKG.txt&User=ANONYMOUS&Password=anonymous&SortMethod=h%7C-&MaximumDocuments=1&FuzzyDegree=0&ImageQuality=r75g8/r75g8/x150y150g16/i425&Display=hpfr&DefSeekPage=x&SearchBack=ZyActionL&Back=ZyActionS&BackDesc=Results%20page&MaximumPages=1&ZyEntry=3&SeekPage=f (accessed on 8 July 2024).

- Benzo[a]Pyrene (CAS 50-32-8)—Chemical & Physical Properties by Cheméo. Available online: https://www.chemeo.com/cid/18-179-4/Benzo-a-pyrene#ref-joback (accessed on 8 July 2024).

- Lelet, M.I.; Larina, V.N.; Petrov, A.V.; Silyakova, E.O.; Suleimanov, E.V. Benzo[a]Pyrene: Standard Thermodynamic Properties from Adiabatic and Combustion Calorimetry and Density Functional Theory. J. Chem. Eng. Data 2021, 66, 3678–3685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odajima, T.; Onishi, M.; Sato, N.; Kashiwabara, M.; Ichida, T.; Takamatsu, T.; Yuki, S. Halogenation of Benzo[a]Pyrene by Myeloperoxidase. Jpn. J. Oral. Biol. 1985, 27, 282–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sozzi, D.A.; Taghipour, F. Computational and Experimental Study of Annular Photo-Reactor Hydrodynamics. Int. J. Heat. Fluid. Flow. 2006, 27, 1043–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, I.S.O.; Santos, R.J.; Dias, M.M.; Faria, J.L.; Silva, C.G. Radiation Models for Computational Fluid Dynamics Simulations of Photocatalytic Reactors. Chem. Eng. Technol. 2023, 46, 1059–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Wu, Z.; Liu, D.; Gao, Z. Preparation of ZnO Photocatalyst for the Efficient and Rapid Photocatalytic Degradation of Azo Dyes. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2017, 12, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukwevho, N.; Fosso-Kankeu, E.; Waanders, F.; Bunt, J.; de Bruyn, D.; Kumar, N.; Ray, S.S. Sol-Gel Preparations of ZnO/SnO2 Composite Photocatalysts Applied for the Degradation of PAH’s under Visible Light. In Proceedings of the 10th Int’l Conference on Advances in Science, New Delhi, India, 10 November 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vela, N.; Martínez-Menchón, M.; Navarro, G.; Pérez-Lucas, G.; Navarro, S. Removal of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) from Groundwater by Heterogeneous Photocatalysis under Natural Sunlight. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2012, 232, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sliem, M.A.; Salim, A.Y.; Abdelnaby, R.M.; Genidy Mohamed, G.; Amin, A.S. Photocatalytic Degradation of Naphthalene in Aqueous Dispersion of Nanoparticles: Effect of Different Parameters. Benha J. Appl. Sci. 2022, 2022, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajamanickam, D.; Shanthi, M. Photocatalytic Degradation of an Organic Pollutant by Zinc Oxide—Solar Process. Arab. J. Chem. 2016, 9, S1858–S1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turchi, C.S.; Ollis, D.F. Photocatalytic Degradation of Organic Water Contaminants: Mechanisms Involving Hydroxyl Radical Attack. J. Catal. 1990, 122, 178–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhadian, M.; Sangpour, P.; Hosseinzadeh, G. Preparation and Photocatalytic Activity of WO3-MWCNT Nanocomposite for Degradation of Naphthalene under Visible Light Irradiation. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 39063–39073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sliem, M.A.; Salim, A.Y.; Mohamed, G.G. Photocatalytic Degradation of Anthracene in Aqueous Dispersion of Metal Oxides Nanoparticles: Effect of Different Parameters. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2019, 371, 327–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, M.J.; Fadaei, A.; Jalali, S.; Shekoohmandi, H.; Khaniabadi, Y.O.; Kianizadeh, M. Benzo[a]Pyrene Decomposition by UV/ZnO Process: Treatment Condition Optimization by Design of Experiments. Polycycl. Aromat. Compd. 2022, 42, 3253–3263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Li, P.; Gong, Z.; Li, X. Photocatalytic Degradation of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons on Soil Surfaces Using TiO2 under UV Light. J. Hazard. Mater. 2008, 158, 478–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umukoro, E.H.; Peleyeju, M.G.; Ngila, J.C.; Arotiba, O.A. Photocatalytic Degradation of Acid Blue 74 in Water Using Ag–Ag2O–ZnO Nanostuctures Anchored on Graphene Oxide. Solid. State Sci. 2016, 51, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Wen, M.; Huang, Z.; Wu, Q.; Liu, J.; Tu, T. Construction of Cu@ZnO Nanobrushes Based on Cu Nanowires and Their High-Performance Selective Degradation of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons. J. Mater. Chem. A Mater. 2015, 3, 600–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanker, U.; Jassal, V.; Rani, M. Degradation of Toxic PAHs in Water and Soil Using Potassium Zinc Hexacyanoferrate Nanocubes. J. Environ. Manag. 2017, 204, 337–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio, K. Why Researchers Should Publish Their Data. Available online: https://www.povertyactionlab.org/blog/3-20-19/why-researchers-should-publish-their-data (accessed on 31 July 2024).

- Sinharay, S. An Overview of Statistics in Education. In International Encyclopedia of Education; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2010; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, S.H.; Morais, M.; Nunes, D.; Oliveira, M.J.; Rovisco, A.; Pimentel, A.; Águas, H.; Fortunato, E.; Martins, R. High UV and Sunlight Photocatalytic Performance of Porous ZnO Nanostructures Synthesized by a Facile and Fast Microwave Hydrothermal Method. Materials 2021, 14, 2385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahman Tamuri, A.; Nizam Lani, M.; Elisha Kundwal, M.; Assyafiq Sahar, M.; Sarah Akmal Abu Bakar, N.; Elisha Kundel, M.; Mat Daud, Y. Ultravoilet (UV) Light Spectrum of Flourescent Lamps. In Proceedings of the 8th SEATUC Symposium, Johor Bahru, Malaysia, 3–5 March 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, C.G.; Lee, A.-L.; Vilela, F. Heterogeneous Photocatalysis in Flow Chemical Reactors. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2020, 16, 1495–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janotti, A.; Van de Walle, C.G. Fundamentals of Zinc Oxide as a Semiconductor. Rep. Prog. Phys. 2009, 72, 126501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abebe, B.; Murthy, H.C.A.; Zereffa, E.A. Multifunctional Application of PVA-Aided Zn-Fe-Mn Coupled Oxide Nanocomposite. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2021, 16, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nadikatla, S.K.; Chintada, V.B.; Gurugubelli, T.R.; Koutavarapu, R. Review of Recent Developments in the Fabrication of ZnO/CdS Heterostructure Photocatalysts for Degradation of Organic Pollutants and Hydrogen Production. Molecules 2023, 28, 4277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, Z.; Wenk, J.; Mattia, D. Increased Photocorrosion Resistance of ZnO Foams via Transition Metal Doping. RSC Adv. 2023, 13, 2438–2450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, K.M.; Benitto, J.J.; Vijaya, J.J.; Bououdina, M. Recent Advances in ZnO-Based Nanostructures for the Photocatalytic Degradation of Hazardous, Non-Biodegradable Medicines. Crystals 2023, 13, 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amakiri, K.T.; Angelis-Dimakis, A.; Canon, A.R. Recent Advances, Influencing Factors, and Future Research Prospects Using Photocatalytic Process for Produced Water Treatment. Water Sci. Technol. 2022, 85, 769–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rani, M.; Shanker, U. Promoting Sun Light-Induced Photocatalytic Degradation of Toxic Phenols by Efficient and Stable Double Metal Cyanide Nanocubes. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 25, 23764–23779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rani, M.; Shanker, U.; Chaurasia, A.K. Catalytic Potential of Laccase Immobilized on Transition Metal Oxides Nanomaterials: Degradation of Alizarin Red S Dye. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2017, 5, 2730–2739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rani, M.; Shanker, U.; Jassal, V. Recent Strategies for Removal and Degradation of Persistent & Toxic Organochlorine Pesticides Using Nanoparticles: A Review. J. Environ. Manag. 2017, 190, 208–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satheesh, R.; Vignesh, K.; Suganthi, A.; Rajarajan, M. Visible Light Responsive Photocatalytic Applications of Transition Metal (M = Cu, Ni and Co) Doped α-Fe2O3 Nanoparticles. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2014, 2, 1956–1968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Jia, H.; Nulaji, G.; Gao, H.; Wang, F.; Wang, C. Photolysis of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) on Fe3+-Montmorillonite Surface under Visible Light: Degradation Kinetics, Mechanism, and Toxicity Assessments. Chemosphere 2017, 184, 1346–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shanker, U.; Jassal, V.; Rani, M. Green Synthesis of Iron Hexacyanoferrate Nanoparticles: Potential Candidate for the Degradation of Toxic PAHs. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2017, 5, 4108–4120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardhani, S.; Purwonugroho, D.; Fitri, C.W.; Prananto, Y.P. Effect of PH and Irradiation Time on TiO2-Chitosan Activity for Phenol Photo-Degradation. In Proceedings of the AIP Conference Proceedings, Sofia, Bulgaria, 26–30 August 2018; American Institute of Physics Inc.: College Park, MD, USA, 2018; Volume 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann, M.R.; Martin, S.T.; Choi, W.; Bahnemann, D.W. Environmental Applications of Semiconductor Photocatalysis. Chem. Rev. 1995, 95, 69–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.M.; Bin Mukhlish, M.Z.; Uddin, S.; Das, S.; Ferdous, K.; Khan, M.R.; Islam, M.A. Photocatalytic Degradation of Reactive Yellow in Batch and Continuous Photoreactor Using Titanium Dioxide. J. Sci. Res. 2012, 4, 665–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Liu, P.; Huang, F. Photocatalytic Degradation of Volatile Organic Compounds in an Annular Reactor Under Realistic Indoor Conditions. Environ. Eng. Sci. 2015, 32, 331–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nosaka, Y.; Nosaka, A. 6: Kinetics and Mechanism in Photocatalysis. In Introduction to Photocatalysis: From Basic Science to Applications; The Royal Society of Chemistry: London, UK, 2016; ISBN 978-1-78262-320-5. [Google Scholar]

- Sujatha, G.; Shanthakumar, S.; Chiampo, F. UV Light-irradiated Photocatalytic Degradation of Coffee Processing Wastewater Using TiO2 as a Catalyst. Environments 2020, 7, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Zhang, W.; Li, Q.; Liu, H.; Wang, X. Preparations and Applications of Zinc Oxide Based Photocatalytic Materials. Adv. Sens. Energy Mater. 2023, 2, 100069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuama, A.N.; Alzubaidi, L.H.; Jameel, M.H.; Abass, K.H.; bin Mayzan, M.Z.H.; Salman, Z.N. Impact of Electron–Hole Recombination Mechanism on the Photocatalytic Performance of ZnO in Water Treatment: A Review. J. Solgel Sci. Technol. 2024, 110, 792–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enesca, A.; Isac, L. The Influence of Light Irradiation on the Photocatalytic Degradation of Organic Pollutants. Materials 2020, 13, 2494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, H.; Yusuf, M.; Song, S.; Park, S.; Park, K.H. Efficient Photocatalytic Degradation of Dyes Using Photo-Deposited Ag Nanoparticles on ZnO Structures: Simple Morphological Control of ZnO. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 8709–8717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yunus, N.N.; Hamzah, F.; So’Aib, M.S.; Krishnan, J. Effect of Catalyst Loading on Photocatalytic Degradation of Phenol by Using N, S Co-Doped TiO2. In Proceedings of the IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, Busan, Republic of Korea, 25–27 August 2017; Institute of Physics Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2017; Volume 206. [Google Scholar]

- Van-Pham, D.-T.; Tri Nguyen, M.; Ohdomari, K.; M Hassan, S.S.; M El Azab, W.I.; Ali, H.R.; M Mansour, M.S. Green Synthesis and Characterization of ZnO Nanoparticles for Photocatalytic Degradation of Anthracene. Adv. Nat. Sci. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2015, 6, 045012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukwevho, N.; Fosso-Kankeu, E.; Waanders, F.; Kumar, N.; Ray, S.S.; Yangkou Mbianda, X. Photocatalytic Activity of Gd2O2CO3·ZnO·CuO Nanocomposite Used for the Degradation of Phenanthrene. SN Appl. Sci. 2019, 1, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saygı, G.; Kap, Ö.; Özkan, F.Ç.; Varlikli, C. Photocatalytic Reactors Design and Operating Parameters on the Wastewater Organic Pollutants Removal. In Photocatalysis for Environmental Remediation and Energy Production: Recent Advances and Applications; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; pp. 103–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).