1. Introduction

The study of external incompressible flows at high Reynolds numbers around bluff bodies finds many engineering applications, such as cables of suspension bridges, chimneys, heat exchanger tubes, nuclear power plants, offshore platforms, power cables, subsea pipelines, tall buildings, and so on. Flows past bluff bodies include fundamental subjects such as the occurrence of massive boundary layer separation, instability, transition, and formation of a periodic wake downstream of a solid boundary. Consequently, an underlying understanding of the fluid dynamics in flows past bluff bodies is required and challenged. The circular cylinder is the best-known representative of the bluff bodies. The occurrence of flows past a circular cylinder is common in many engineering problems; therefore, this flow configuration has been widely studied, which is also classified as a classical problem in fluid mechanics.

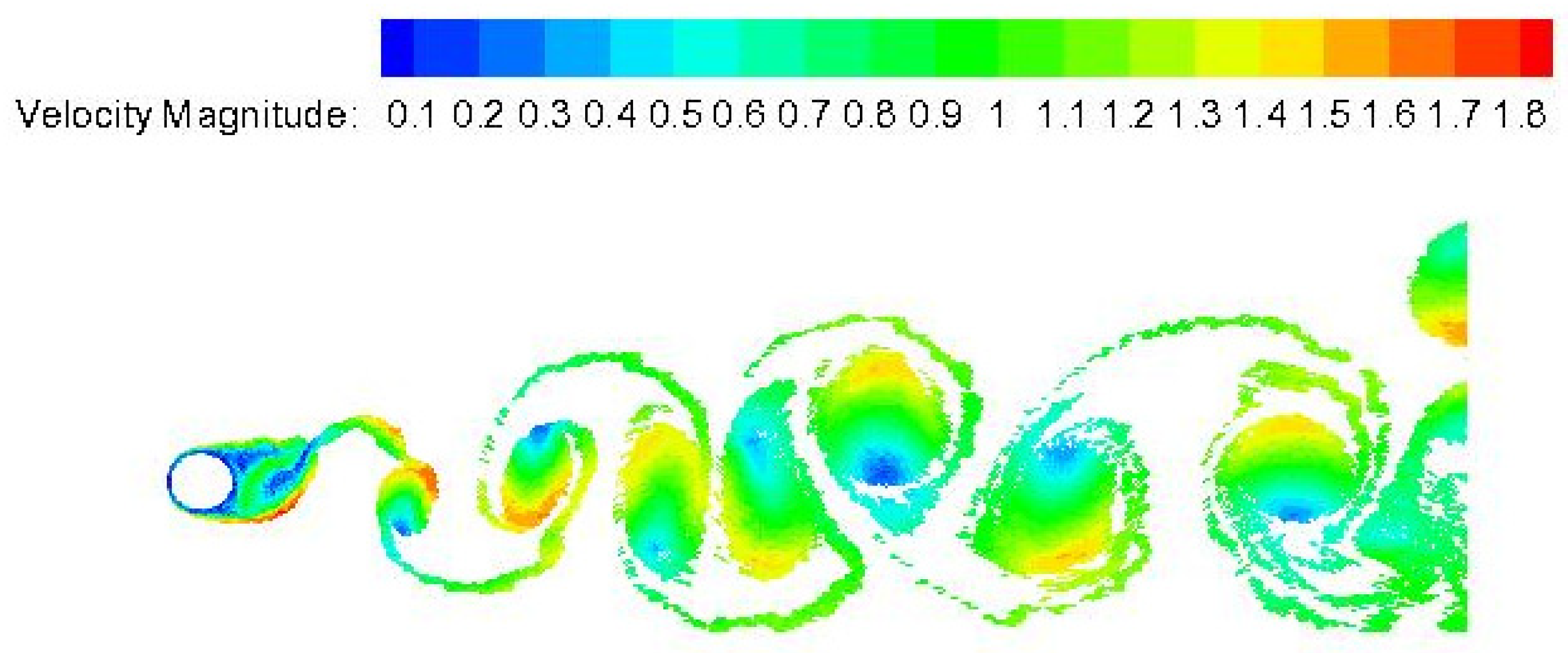

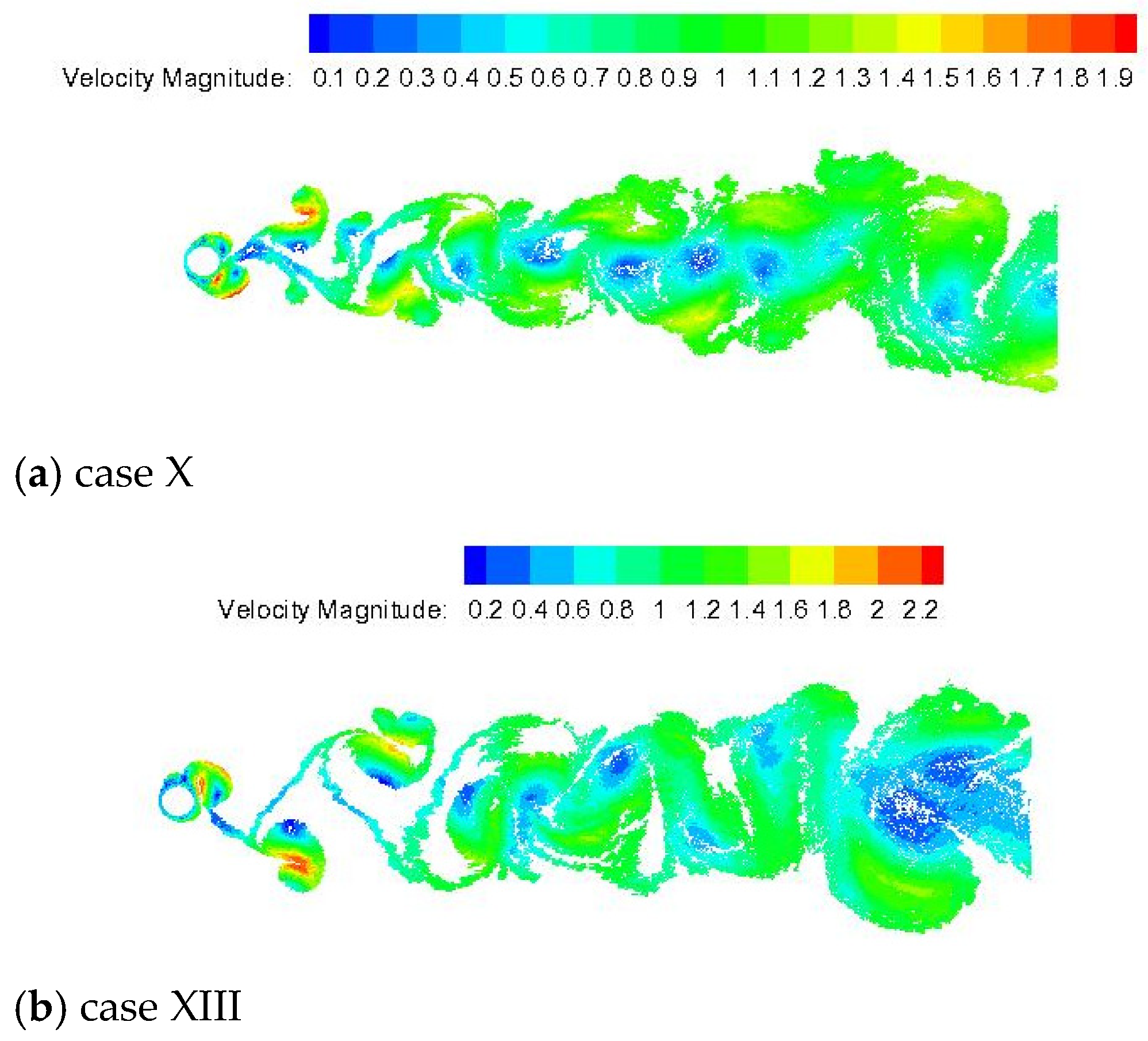

The analysis of this class of flow plays a key role in testing numerical algorithms. Our research group has adopted an interesting strategy aimed at developing discrete vortex methods to enhance the understanding of flow physics from a Lagrangian approach. Accurate solution of detached vortex structures is critical for different problems of bluff body aerodynamics. In this context, many previous investigators have solved fluid–structure interaction (FSI) problems using Lagrangian Vortex Methods (LVM). In a Lagrangian fashion, the major vorticity-containing regions of the flow field are discretized using computational points (discrete point vortices) moving with the fluid particles. This numerical approach avoids stability problems of explicit schemes (or cumbersome implementation of implicit schemes) and mesh refinement problems in regions of high rates of strain; all calculation is restricted to the vorticity-containing regions, and no explicit choice of the outer boundaries is required a priori; no boundary condition is required far from the solid boundaries into the fluid domain. On the other hand, the velocity field computation over the computational points demands a number of operations at each time step proportional to the square of the number of discrete point vortices present in the fluid domain during every time step. This may lead to very large CPU times if a long-time solution is performed. There is no doubt that the future LVM computations, necessary to achieve more complex flow approximations, will need to be continually strengthened with novel high-performance computing parallelism techniques and powerful algorithms [

1].

Recent literature records have pointed to different algorithms to reduce the computational time associated with LVM; some of them are based on improved multipole expansions [

2,

3], and others use parallel implementation with CUDA technology [

4]. The vortex methods have also supported a neural network description of Lagrangian vortices and their interaction dynamics; the purpose was to reconstruct the high-resolution Eulerian flow field in a physically precise form [

5].

The mathematical background and numerical treatment of the LVM are well introduced in the literature, such as a time-stepping scheme to compute viscous effect [

6], vorticity diffusion [

7], solid boundary discretization using a panels method [

8], turbulence modeling [

9], and vorticity generation from the solid surface [

10]. Many algorithms have been implemented to solve problems with diverse sets of characteristics, such as flows around bluff bodies including turbulence modeling, rough surface effect, wall confinement, structural vibration, and mixed convection heat transfer.

Bimbato et al. [

11] developed a two-dimensional rough surface model blended with large-eddy simulation (LES) theory, whose purpose was to alter the boundary layer flow and flow separation. The second-order velocity structure function model of the filtered velocity field was associated with a set of points strategically located close to the circular cylinder surface. The key idea was that the set point would inject momentum in the boundary layer, simulating surface roughness effect. A delay in the separation of the hydrodynamic boundary layer was successively captured in accordance with the expected physics for the problem. Oliveira et al. [

12] applied the rough surface model developed by Bimbato et al. [

11] to investigate circular cylinder aerodynamics in ground effect. The full cessation of the vortex shedding mechanism was captured with combined effects of wall confinement and surface roughness. However, no attempt was made by the authors to include heat transfer and structural vibration.

Narsipur et al. [

13] implemented a vortex method to study the perching and hovering maneuvers, which are two bio-inspired flight maneuvers presenting applicability in engineering problems, especially for small-scale uncrewed air vehicles. Zou et al. [

14] developed a vortex method related to an accurate and efficient dynamic model for robotic fish.

Kumar et al. [

15] employed the vortex method to investigate the flapping motion of a rectangular wing. The parametric dependence of kinematic parameters such as aspect ratio, asymmetric ratio, and reduced frequency on the aerodynamic performance was investigated and discussed.

Hirata et al. [

16] developed a LVM to investigate flows around an oscillating circular cylinder, which moved with constant velocity in a quiescent Newtonian fluid with constant properties. The authors presented a detailed study of the influence of frequency and oscillation amplitude on the aerodynamic loads and vortex shedding frequency in the lock-in regime. Wang et al. [

17] investigated the VIV of deepwater drilling risers in the time domain using the vortex method; the study contributed to the optimal design and engineering control of deepwater drilling risers. However, the latter two papers did not include results with surface roughness effects.

Chiaradia et al. [

18] incorporated the combined effects of turbulence and mixed convection heat transfer to a LVM algorithm. The work presented two examples of application, namely the problems of circular cylinder aerodynamics and airplane wake vortex behavior in the vicinity of a ground plane; however, no surface roughness effects were investigated.

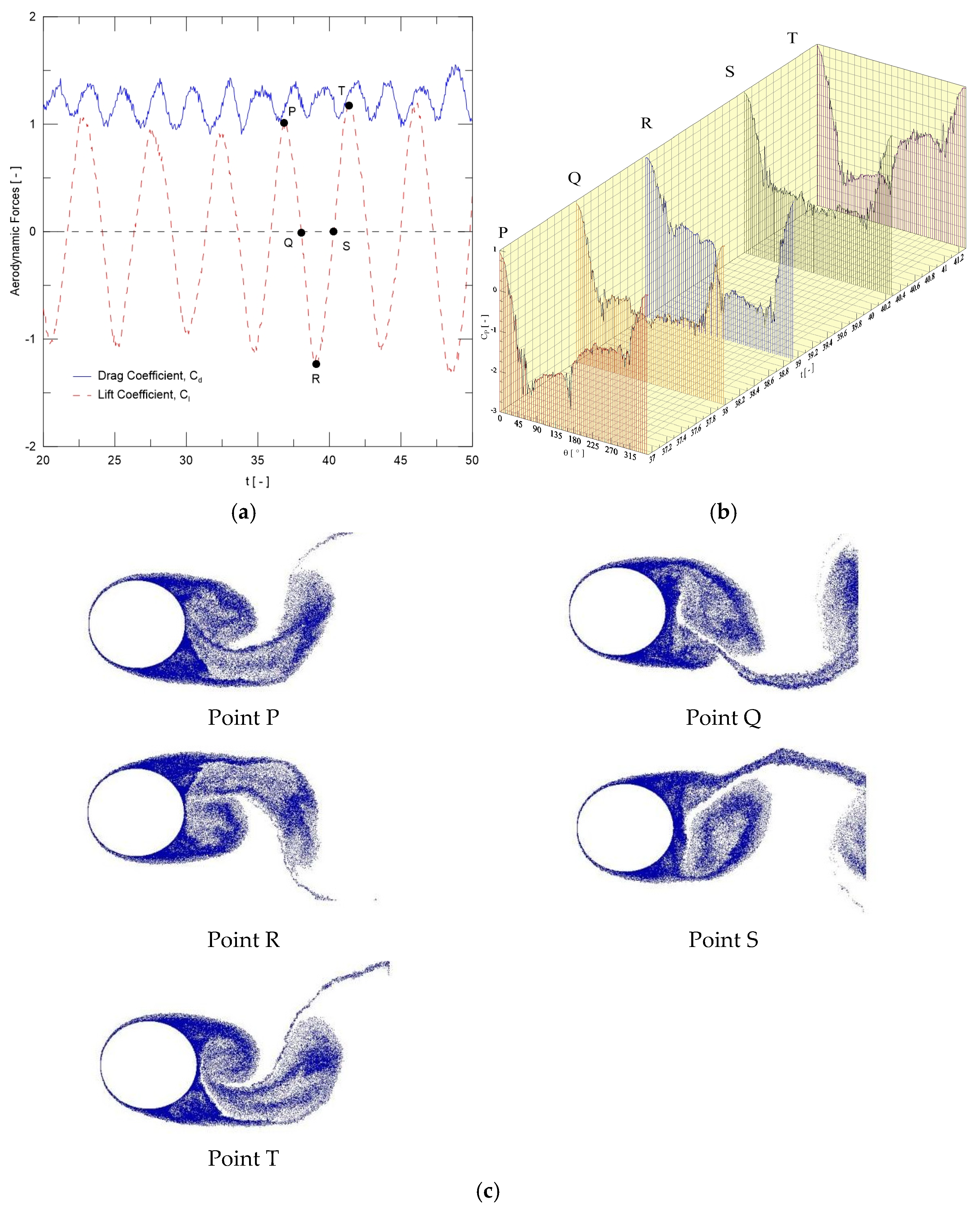

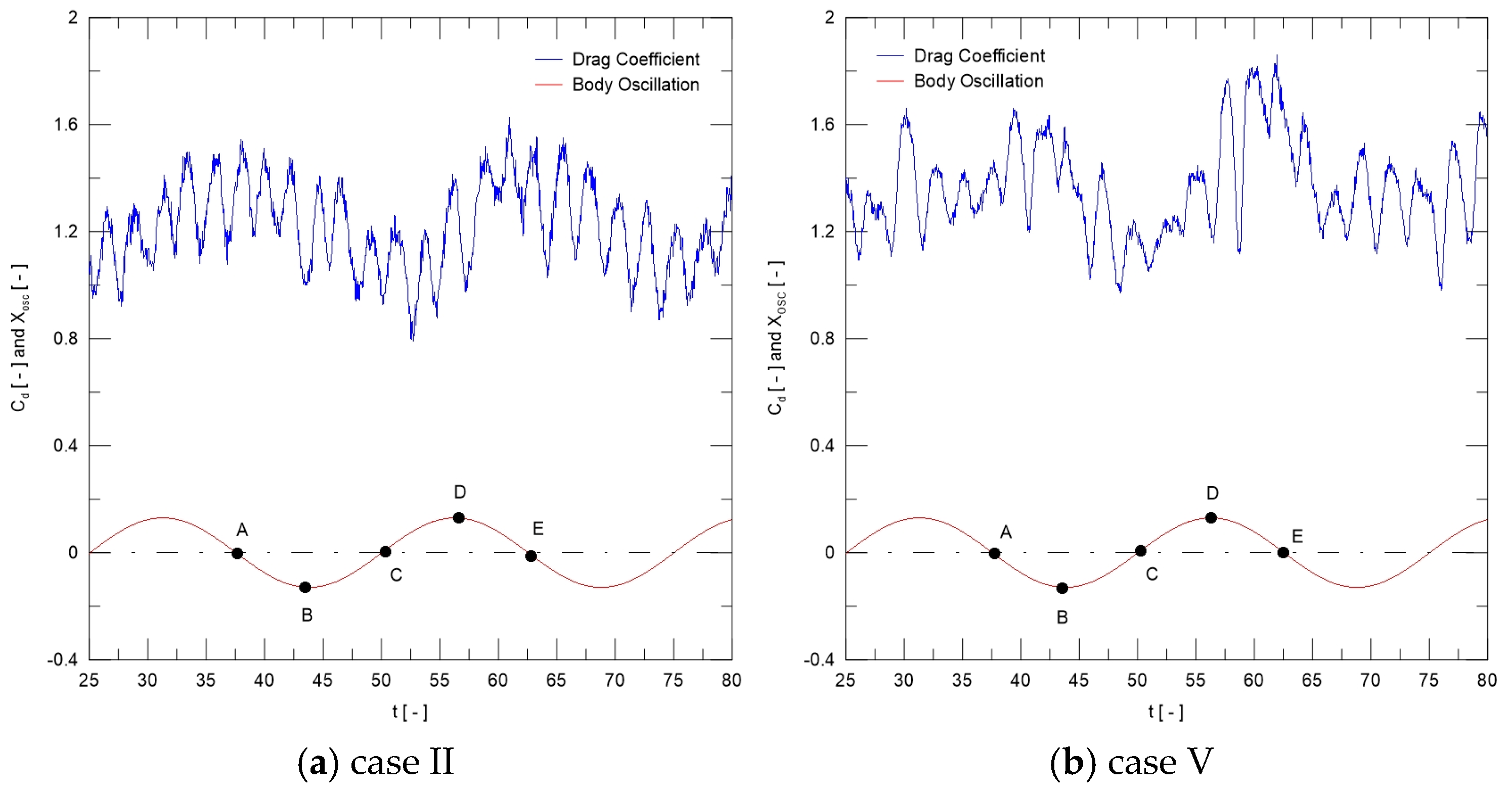

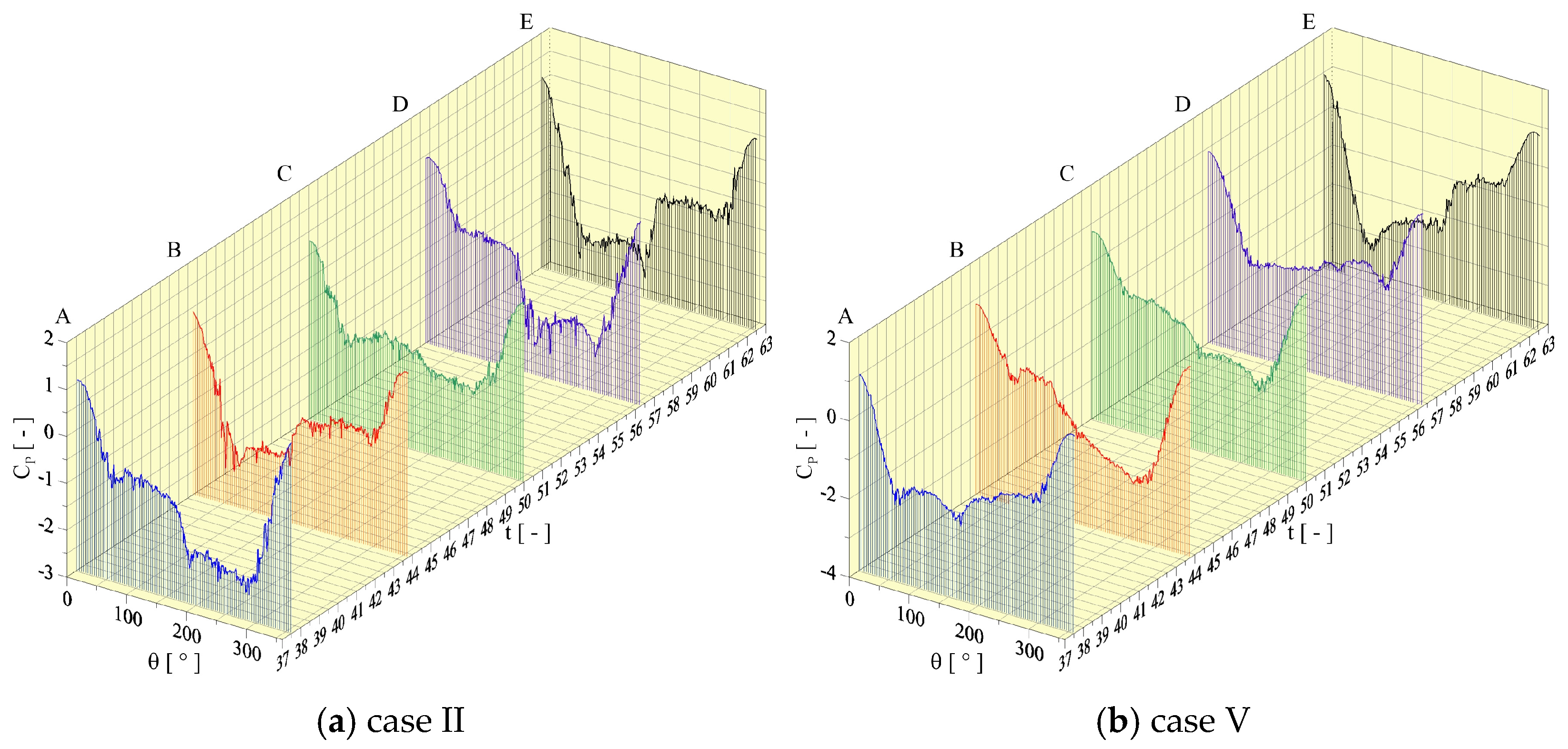

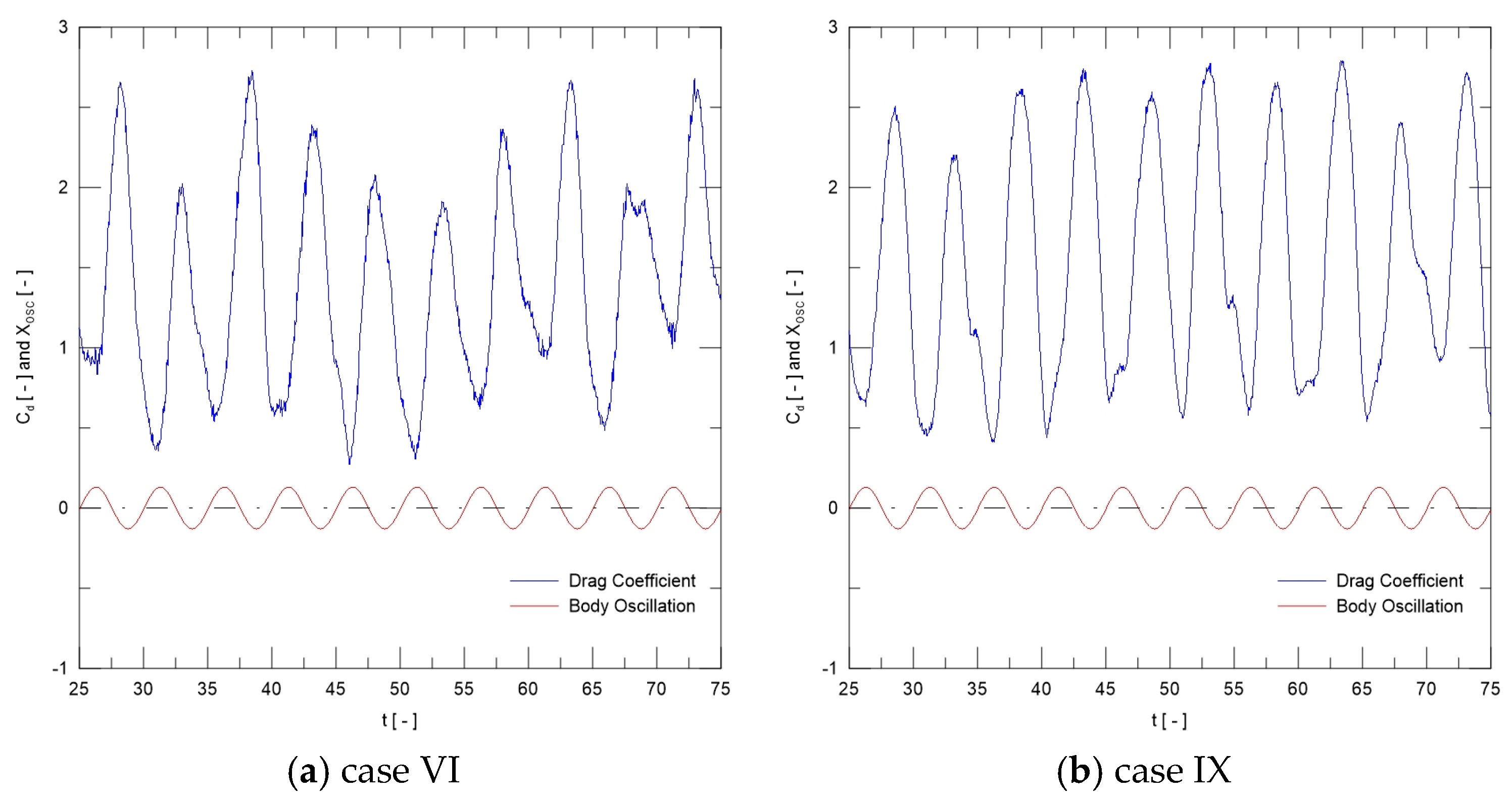

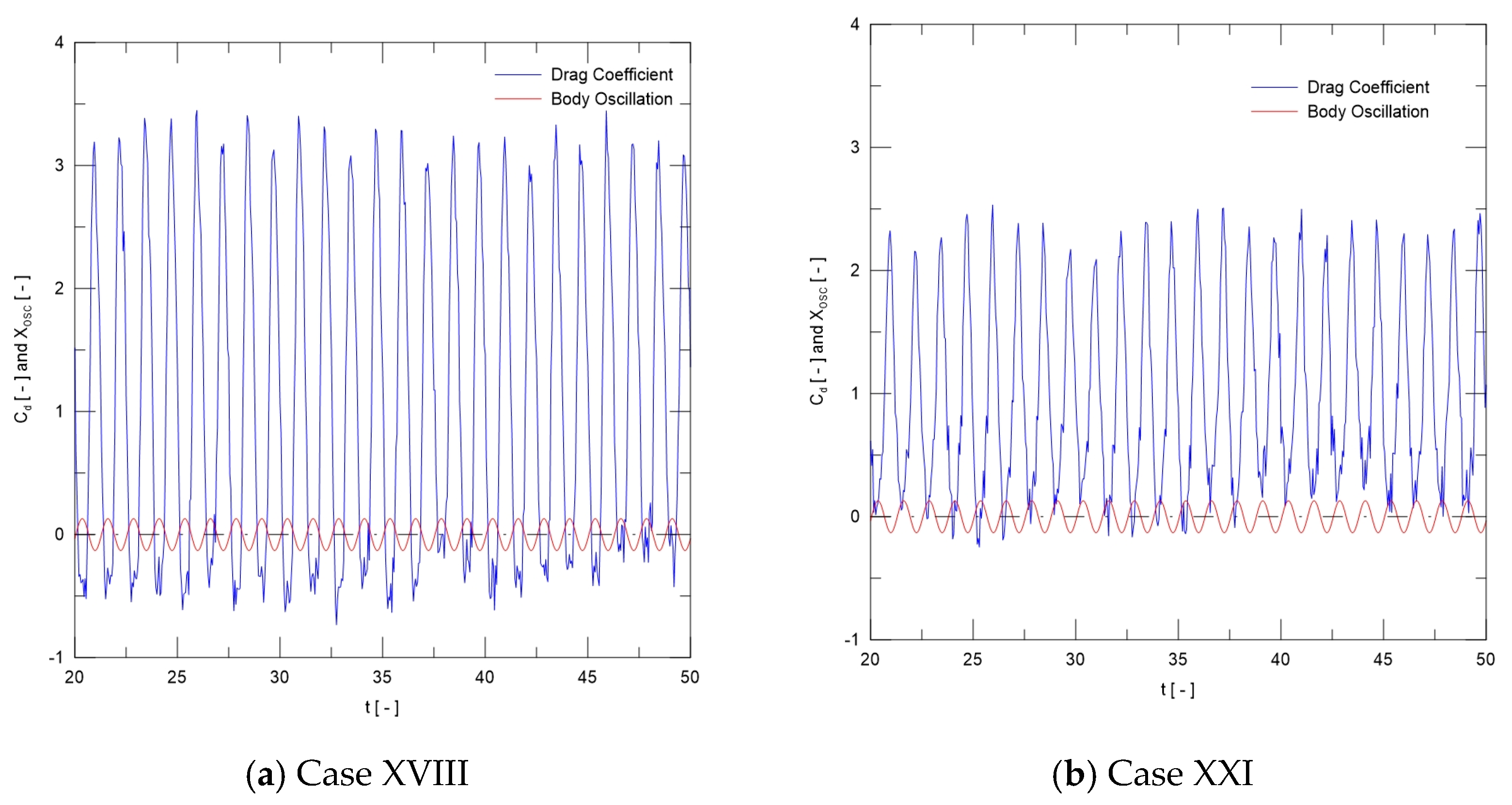

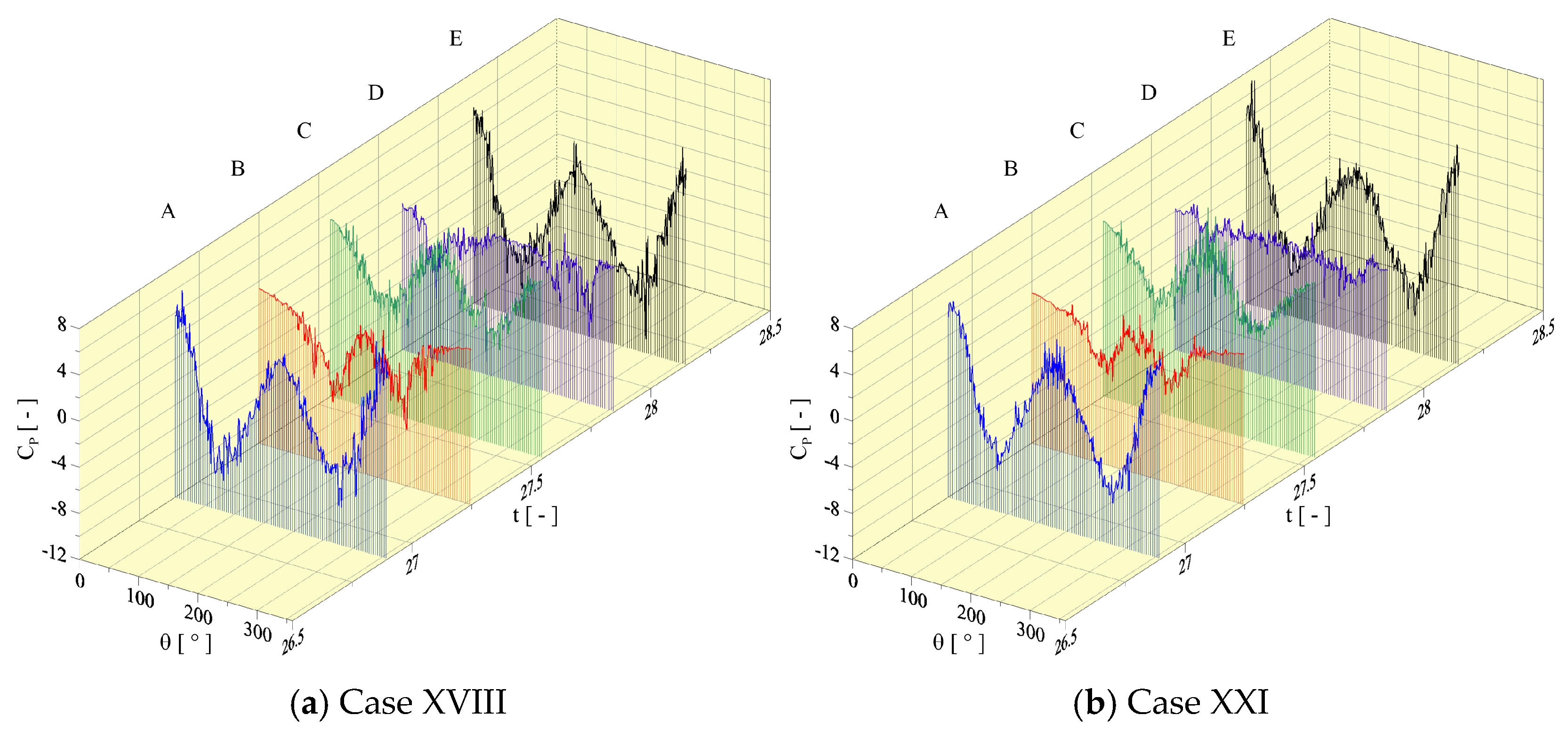

The literature has also explained flows past an immovable circular cylinder in terms of the temporal history of the lift and drag coefficients, in which they oscillate in time with approximately constant amplitude [

16]. The lift coefficient oscillates about zero with a dimensionless frequency equal to the Strouhal number, defined as St = fD/U

∞, where f is the classical vortex shedding frequency forming the viscous wake behind an immovable cylinder, D is the outer cylinder diameter, and U

∞ is the uniform freestream velocity. On the other hand, the drag coefficient simultaneously oscillates with a dimensionless frequency approximately equal to twice the Strouhal number. The Strouhal number presents a value approximately constant and equal to 0.19 for a large range of the Reynolds number, Re [

16]. This behavior reveals that the incoming flow generates an oscillation motion on the cylinder surface because the vortices are alternatively shed, constructing the Von Kármán vortex street. In this case, an additional oscillation motion relative to the incoming flow can also be generated by an unsteady periodic perturbation superimposed on the uniform freestream, impacting immovable cylinder aerodynamics. In this flow condition, the flow is further controlled by both the frequency of the external oscillatory driving force,

f0, and the oscillation amplitude, A. The forced oscillation technique is, therefore, able to simulate conditions in which a structure is placed in fluid flows, and flow-induced vibration (FIV) can appear as a hazard for structural safety. Vortex-induced vibration (VIV) is a type of FIV defined as the vibration caused by vortex shedding from the structure. It is necessary to design VIV suppression techniques for real-life engineering structures.

Zhao [

19] reviewed the most recent studies for suppressing the VIV of circular cylinders related to passive and active flow control devices. The passive flow control devices interfere with shear layer, flow separation, or viscous wake interaction. The reviewed devices were control rods, porous layers, splitters, and rough surface. On the other hand, active control devices need external energy and can induce a modification on the flow separation or viscous wake interaction. The energy requirement makes active control more costly, and the author reviewed the following devices: jet flow, rotating cylinder, and rotating control rods.

The problem of oscillatory wake formation behind a circular cylinder under streamwise oscillation motion has attracted less attention in the research community, which, however, is equally important to problems like vortex-induced vibration of transverse vibration motion, either induced or forced. In general, experimental studies of controlled forced vibration are generally conducted by water flume tests, varying oscillation amplitude and frequency. Bearman [

20] postulated that a cylinder under free vibration, combined with a small increase in flow velocity, will experience large changes in its oscillation amplitude, possibly accompanied by a change in the vortex formation mode. Therefore, it is more difficult to study such jumps, or transitions, for a cylinder under the condition of free vibration. On the other hand, controlled forced vibration of a cylinder requires a large number of runs to more precisely map the conditions under which energy transfers from the fluid to the body. It is important to comment that the majority of the numerical studies of VIV control have been performed under low Reynolds number laminar flow regimes, more precisely for Re ≤ 200. On the contrary, the Reynolds numbers fall within the turbulent flow regime in most water and wind engineering applications.

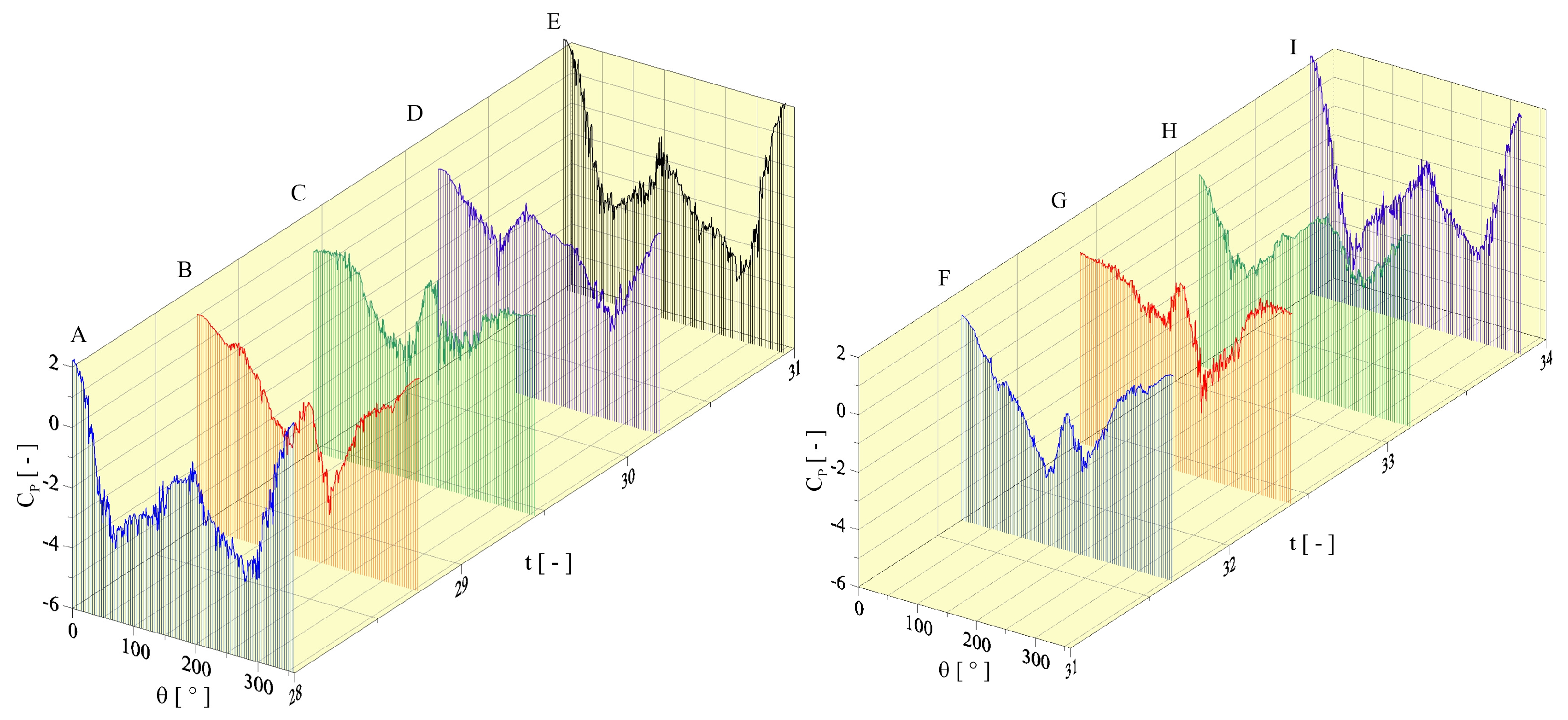

Ongoren and Rockwell [

21] experimentally investigated the vortex formation regimes of a cylinder undergoing controlled oscillations at arbitrary angle δ with respect to the freestream velocity. For most experiments, a constant value of dimensionless oscillation amplitude was chosen as A/D = 0.13 for δ = 0°, with the Reynolds number kept fixed at Re = 855. The oscillation frequency adopted by the authors is here redefined as

f0, and the natural vortex-shedding frequency from corresponding immovable cylinder is also redefined as

f [

16]. The authors considered a frequency relation in the range 0.5 ≤

f0/

f ≤ 4.0 and identified two basic modes, which are the symmetric and anti-symmetric vortex formation. The work classified these two basic modes into five submodes: S mode for the symmetric formation regime, and A-I, II, III, IV modes for the anti-symmetric formation regime. The symmetric S mode appeared at all excitation angles δ, except at δ = 90°. The anti-symmetric A-II, A-III, and A-IV modes exhibited period (i.e., one body oscillation cycle) doubling relative to the classical Kármán street formation of the anti-symmetric A-I mode. Furthermore, the A-III and A-IV modes present formation of counter-rotating vortex pairs. The A-III and A-IV modes appeared only for δ = 0°. Interestingly, the A-II mode was captured only for δ ≠ 0°. In general, these modes either can be phase-locked with the cylinder oscillatory motion, or they can compete and switch between symmetric and anti-symmetric vortex formation. The authors did not include investigation about rough surface effects.

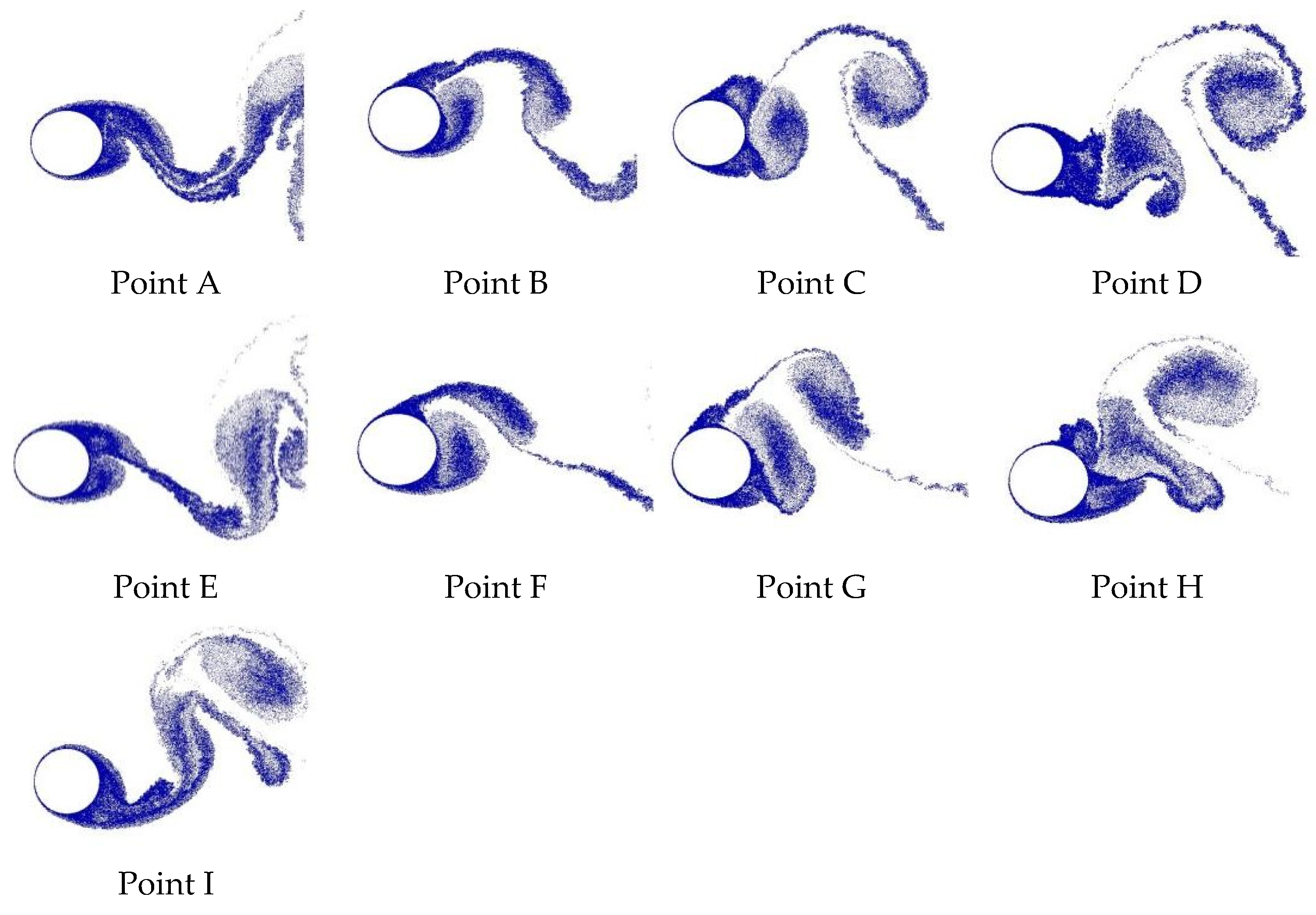

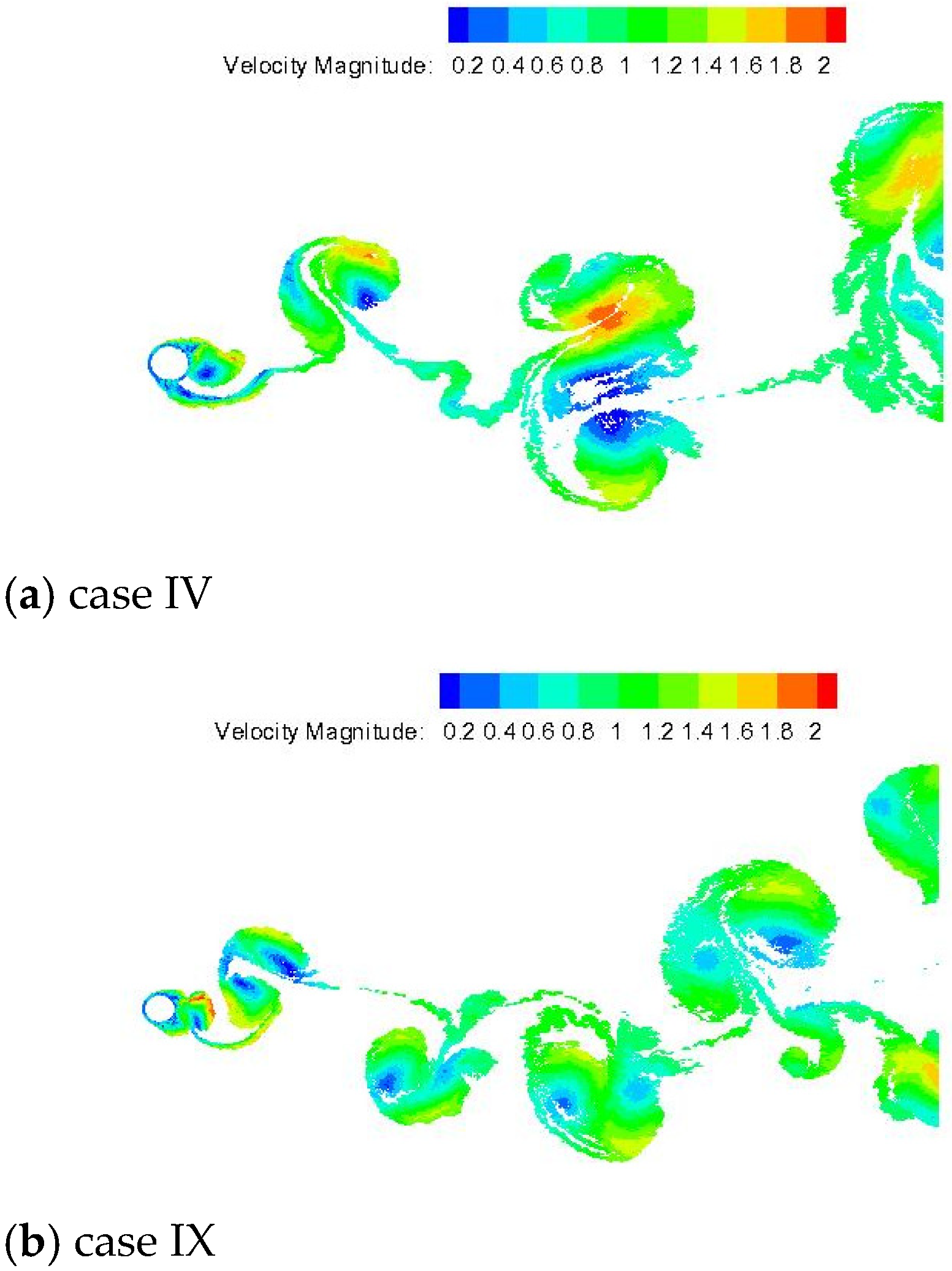

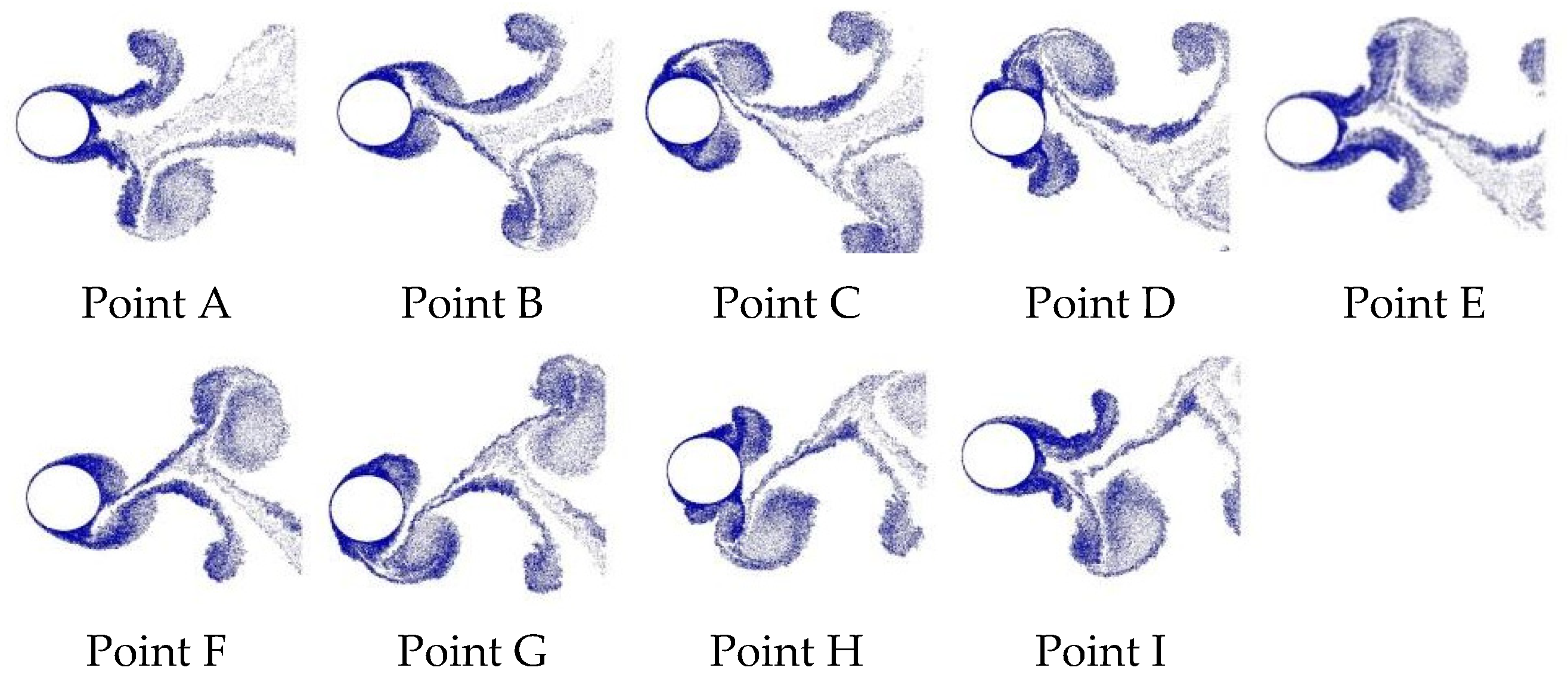

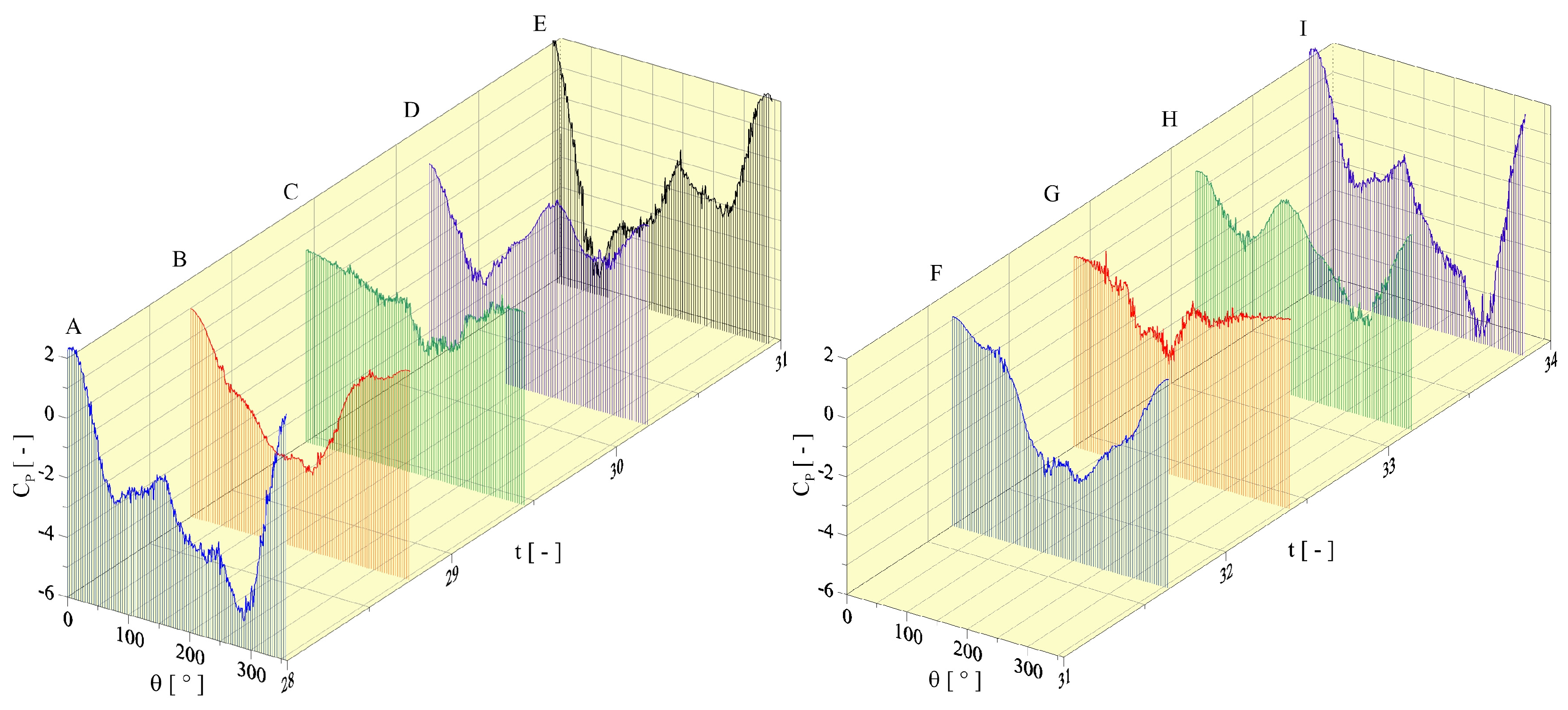

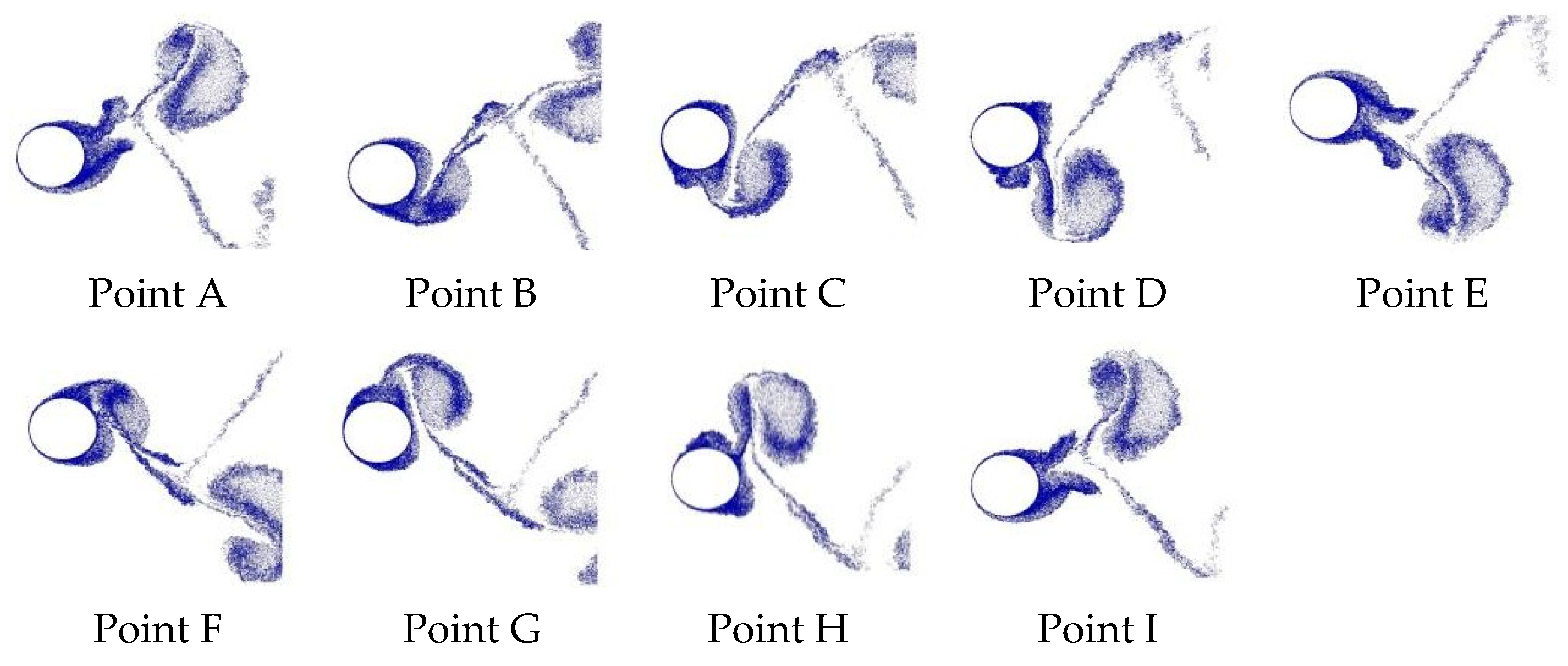

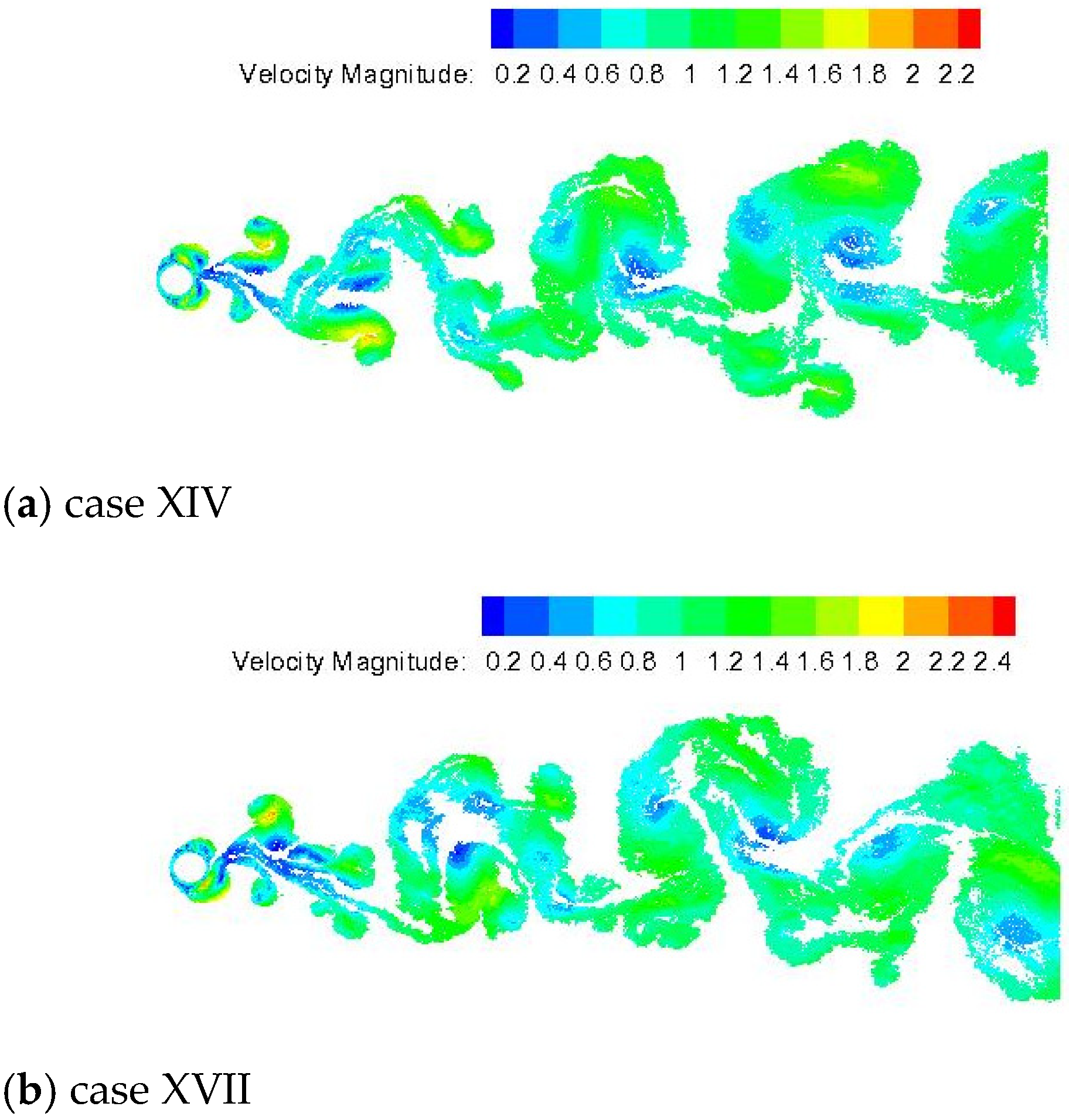

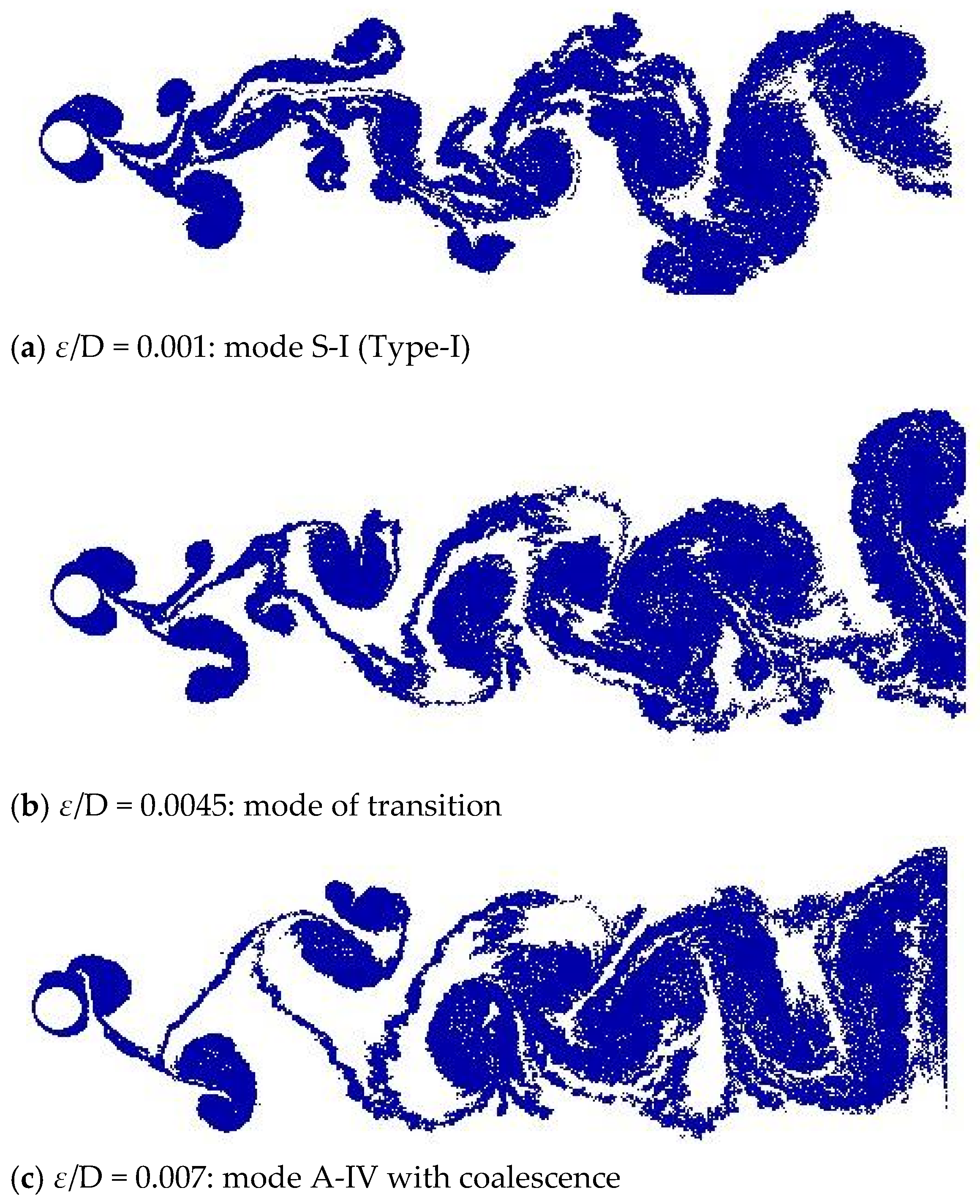

In general, previous studies of the flow behind a streamwisely oscillating cylinder have reported six modes, i.e., A-I, A-II, A-III, A-IV, S-I, and S-II, in which the maximum oscillation amplitude is about (A/D)

max < 0.8 and the maximum forcing frequency is about (

f0/

f)

max < 3. Additionally, Hu et al. [

22] studied the wake modes behind a circular cylinder under streamwise forced oscillation at Reynolds numbers in the range of Re = 360–460, which are visualized using the laser-induced fluorescence technique. The forcing frequency

f0/

f ranged from 0.0 to 6.85, and the amplitude A/D was investigated for 0.2, 0.5, and 1.0. Typical flow modes reported by Xu et al. [

23] were also observed by the authors, such as asymmetric modes, symmetric modes, and Chaotic modes. Three rarely reported modes in previous numerical studies, C-I, C-II, and S-III, were confirmed by Hu et al. [

22]. These modes typically occur at higher amplitude and/or

f0 ranges than those investigated in previous works. The lock-in regime at a fixed amplitude generally follows the order of S-I (Type-I) mode, A modes, S-I (Type II) mode, and S-II/S-III and C modes (Chaotic modes) as the time invariant

f0 increases. In general, the different vortex formation modes have been captured in terms of the following control parameters: forcing amplitude, body forcing frequency, and Reynolds number based on the freestream velocity. However, the roughness effect was not reported by all authors. Of particular interest for the present work, the S-I (Type I) mode is identified when a pair of vortices is shed in phase from both sides of the cylinder during one oscillation cycle and immediately coalesce in the near wake region. And, the Chaotic mode C-I is characterized when small-scale vortices form, lose their stability quickly, and coalesce to form vortices of larger scale [

23].

This paper contributes to the VIV literature by investigating two-dimensional, incompressible, unsteady flow past a rough cylinder under sinusoidal oscillation motion in a streamwise direction. There is limited data related to LVM with surface roughness effects to simulate flows past a circular cylinder forced to oscillate with respect to the freestream. In the past, our research group has reported that the use of two-dimensional LES-based turbulence modeling is necessary to stabilize the numerical solution and enables the development of rough surface models [

9,

11,

12]. The advantage of combining the LES model and LVM is that the concept of differences of velocity (velocity fluctuations) is used instead of derivatives (rates of deformation). The local eddy viscosity coefficient is computed over every discrete point vortex along with the vorticity diffusion process during the time stepping. In other words, that computation considers the small-scale effect of the flow through the concept of differences in velocity among discrete point vortices. The results contribute to the knowledge of the context in which roughness effects importantly modify the vortex formation modes synchronized with the forced oscillation motion imposed on the body surface over the frequency ratio

f0/

fCD = 1.0. The roughness model developed by Bimbato et al. [

11] is once again validated in the present study.

2. Mathematical Formulation

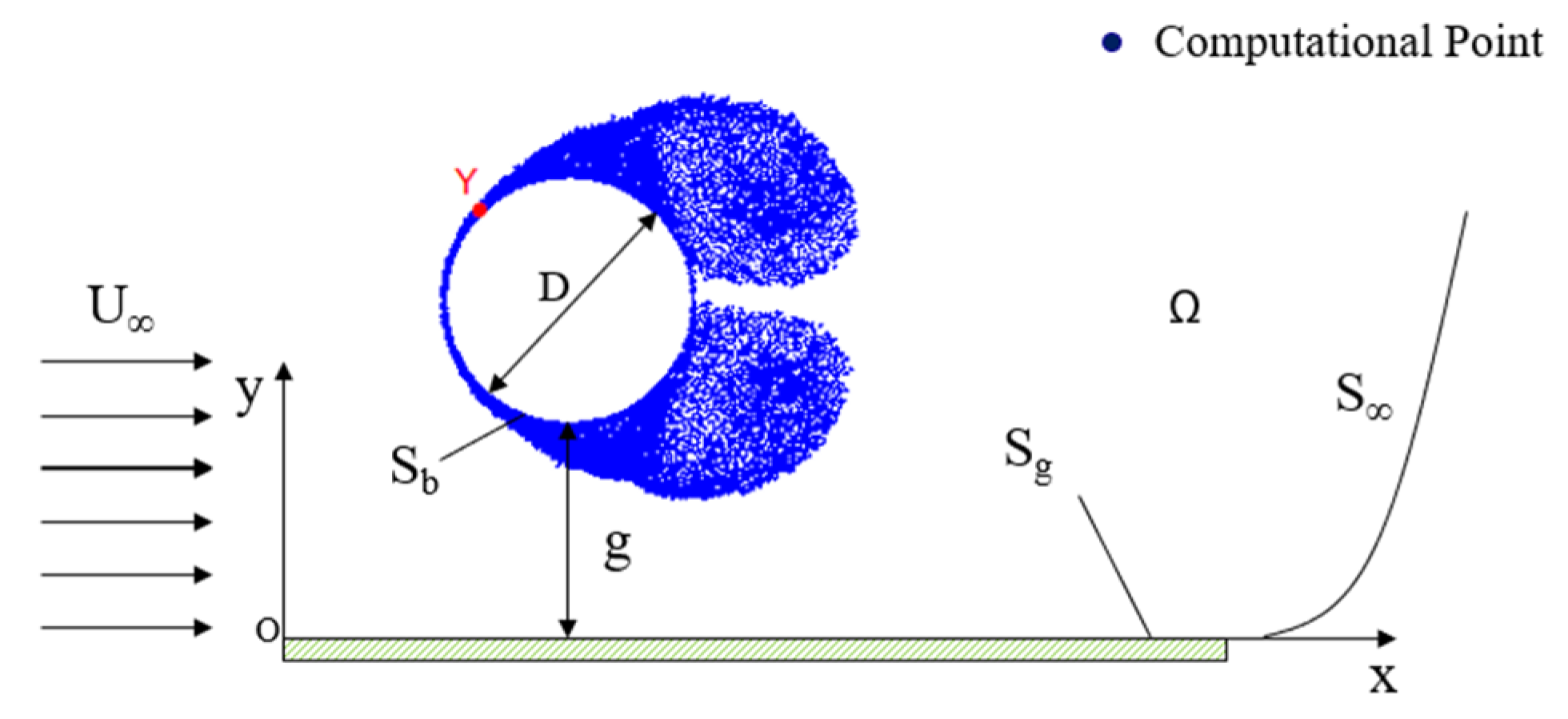

Figure 1 illustrates the flow past a circular cylinder of outer diameter D, immersed in a semi-infinite fluid domain Ω with a uniform flow of freestream velocity U

∞. The semi-infinite fluid domain is defined by surface S = S

b ∪ S

g ∪ S

∞, where S

b is the cylinder surface, S

g is the ground plane surface, and S

∞ defines the far away fluid boundary. The gap between the cylinder bottom and the ground plane is defined by g. In a Lagrangian manner, the vorticity generated from solid surfaces is discretized and represented by computational points, so-called nascent discrete point vortices. In LVM, these computational points are commonly created on solid surfaces at every time step in a typical numerical simulation.

In order to non-dimensionalize all the quantities in the general formulation, D is adopted as the representative length and U∞ is chosen as the representative velocity. The dimensionless time is then defined by tU∞/D.

In

Figure 1, the ground plane is adopted as the inertial frame from which the circular cylinder is forced to oscillate with respect to the freestream at a large gap-to-diameter ratio, namely g/D = 1000. Thus, there is no interference of wall confinement over the oscillatory motion of the circular cylinder.

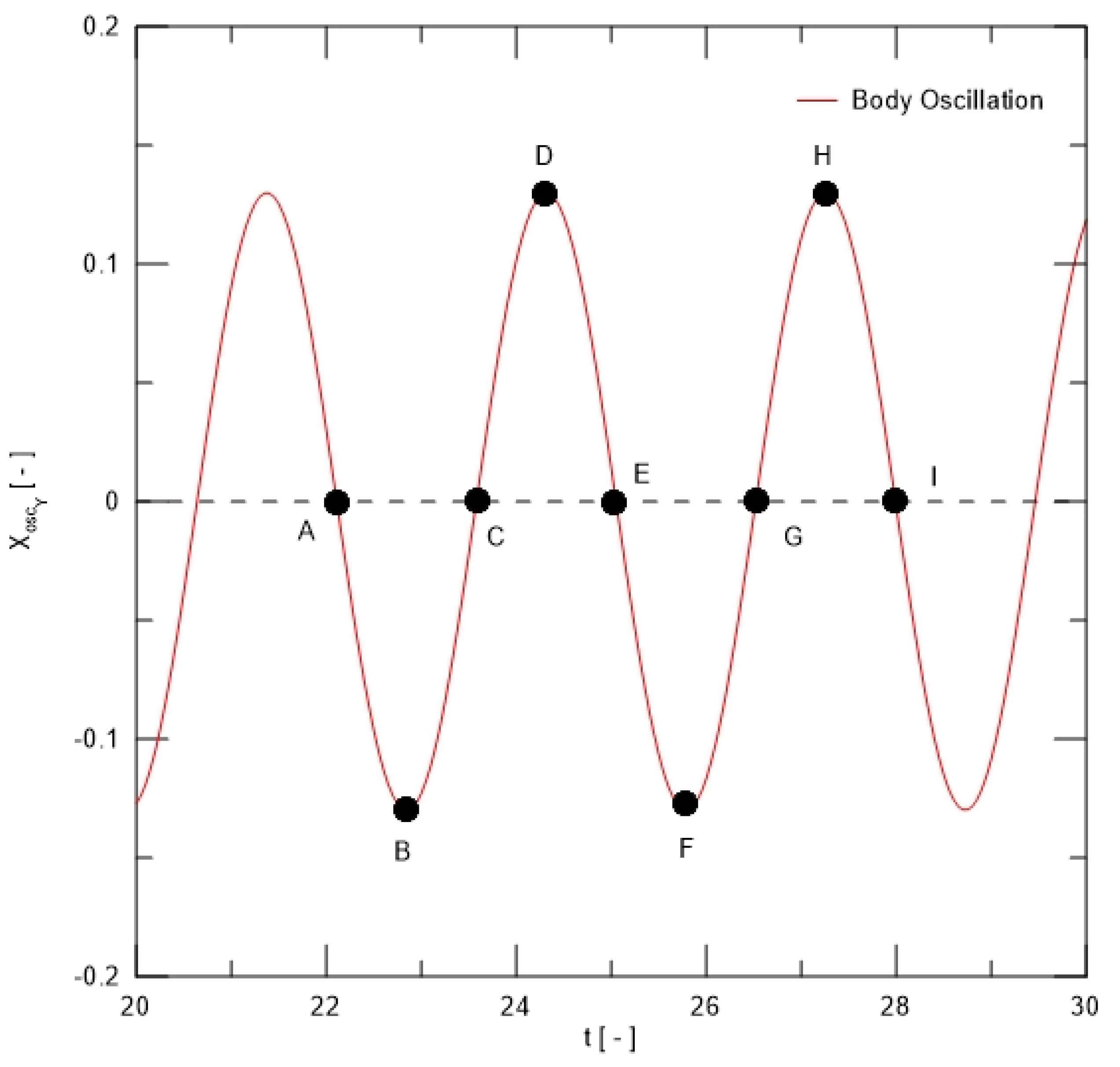

Figure 2 describes the oscillatory motion of point Y placed at the cylinder surface; this point is also identified in

Figure 1. The instantaneous position and velocity of point Y are defined as follows, respectively:

where A is the oscillation amplitude and

f0 is the body oscillation frequency.

The flow is assumed to be incompressible and two-dimensional, and the fluid is assumed to be Newtonian with constant kinematic viscosity ν. The unsteady flow developed from the boundary layer separation on the cylinder surface generates an oscillatory wake downstream of the body. The governing equations for the problem are the vorticity transport equation and pressure Poisson equation. The vorticity transport equation is obtained by taking the curl of the Navier–Stokes equations including some algebraic manipulations, which also eliminates the pressure term. In two dimensions, this equation can be written as follows [

9,

11,

12]:

The pressure Poisson equation is obtained by taking the divergence of the Navier–Stokes equations including some algebraic manipulations, resulting in the following differential equation:

In Equations (3) and (4),

is the filtered velocity field,

is the filtered pressure field, and

is the only non-zero component of the filtered vorticity field (in a direction normal to the plane of flow). The vorticity is a vector quantity, represented by the curl of the velocity field. A “filtered field” is interpreted as the component of the field that remains after removing the small scales related to turbulent motions through a filtering process [

9]. The eddy viscosity coefficient is then identified by ν

t, the Reynolds number, defined as follows:

The flow is started impulsively from rest. The impermeability and no-slip boundary conditions are imposed on the cylinder surface (at r = D/2 = 0.5) as follows, respectively:

where

n and

t are unit vectors normal and tangential to the cylinder surface, respectively. For the ground plane, only the impermeability condition is imposed (at y = 0 and 0 ≤ x ≤ 10D).

Additionally, the perturbation in the semi-infinity fluid domain due to the surfaces S

b and S

g (

Figure 1) fades away, that is:

3. Algorithm of the Lagrangian Vortex Method

The left-hand side of the vorticity transport equation, Equation (3), carries all the information needed for the vorticity advection, while the right-hand side governs the vorticity diffusion and turbulent motions. Chorin [

6] proposed the viscous splitting algorithm, which, for the same time stepping Δt of the numerical simulation, establishes that the vorticity advection is governed by the following equation in a Lagrangian manner:

The vorticity diffusion and turbulent motions are additionally governed by:

where Equations (9) and (10) converge to the original Equation (3) when the time stepping Δt tends to zero.

In the present numerical approach, a cloud of NV discrete point vortices, each of constant strength Γ

k and core size σ

0k, represents the instantaneous vorticity field in the following form [

7]:

3.1. Generation of Source Panels and Discrete Point Vortices

The cylinder and ground plane surfaces are discretized and represented by flat panels. Every flat panel has a central point, the so-called pivotal point, where the boundary conditions of the problem (Equations (6) and (7)) must be more precisely imposed.

The panels method [

24] is employed to represent the solid surfaces of the problem, where NP source panels are generated during every time step; the source strength per panel length is assumed as constant. The source strengths are obtained by solving a linear system of algebraic equations to ensure the impermeability condition (Equation (6)) and mass conservation on every pivotal point due to the incident flow, the source panels, the vortex cloud, and the cylinder oscillation velocity (Equation (2)).

The vorticity flow is represented by proper distribution of discrete point vortices. The strength of the nascent discrete point vortices is obtained by imposing the no-slip condition (Equation (7)) and the global circulation conservation on every pivotal point due to the incident flow, the source panels, the vortex cloud, and the cylinder oscillation velocity (Equation (2)).

Thus, the panels method is combined with the point-vortex representation (vortex cloud) and uniform flow of freestream velocity to construct a flow field over discrete point vortices, which characterizes the Lagrangian description.

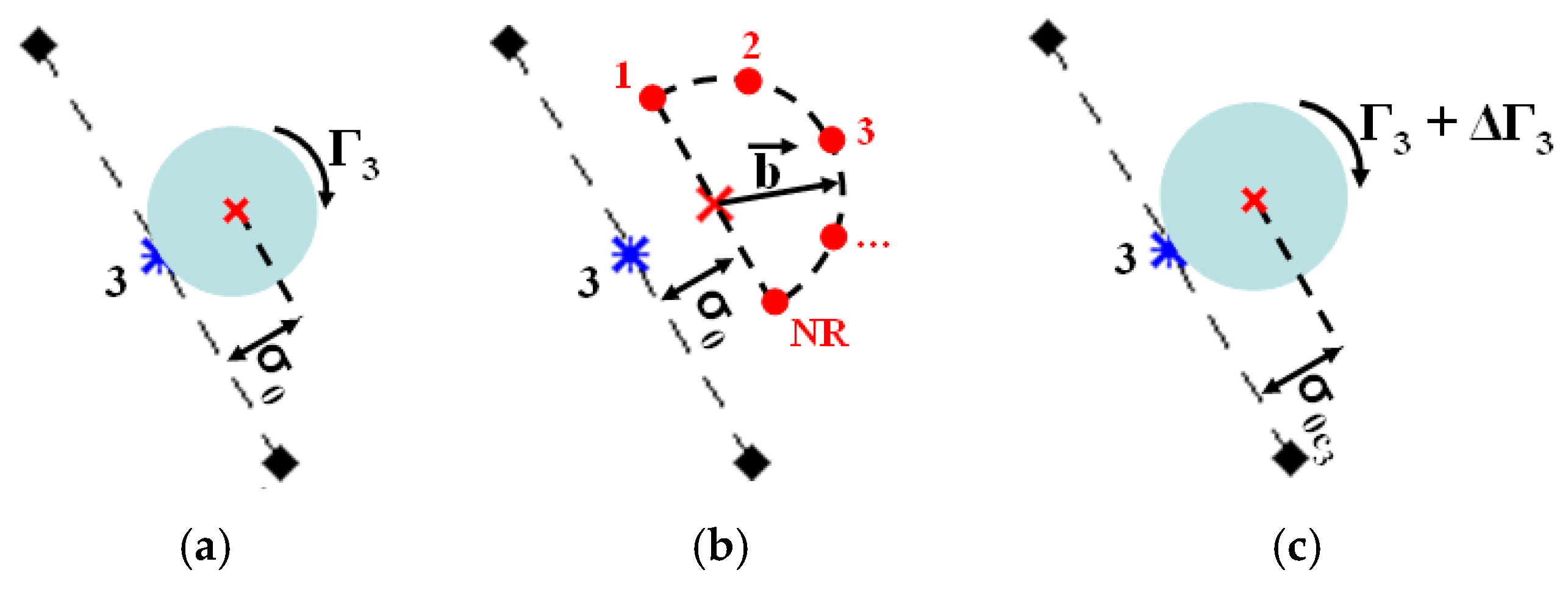

Figure 3a exemplifies the instantaneous generation of a discrete point vortex from the cylinder surface with no roughness model. Additionally, the center of every nascent discrete point vortex is placed at the shedding point. The viscous effect is confined within the vortex core, σ

0.

Figure 3b exemplifies the key idea of the roughness model, which is inspired by momentum injection into the boundary layer during the vorticity shedding from a flat panel. The roughness model modifies the viscous core, σ

0, and the vortex strength, Γ

v, of every nascent discrete point vortex. The three steps necessary to apply the roughness are as follows: (i) the vortex strength, Γ

v, is obtained by solving a linear system of algebraic equations to ensure the non-slip condition on every pivotal point because of incident flow, source panels, vortex cloud, and oscillatory motion of the cylinder; (ii) a semicircle of radius

, centered at the shedding point, is necessary to evaluate turbulent activities into the boundary layer, where ε represents the interference of a selected average roughness height [

11]; and (iii) the vortex strength, Γ

v, must be corrected by solving once more the linear system of algebraic equations to ensure the non-slip condition.

Figure 3c illustrates the effective creation and shedding of a discrete point vortex including the idea of momentum injection into the boundary layer.

Bimbato et al. [

11] adopted a numerical approach to capture the velocity differences among the centere of the ith shedding point and NR = 21 rough points, as sketched in

Figure 3b, where the second-order velocity structure function model of the filtered velocity field is given as follows:

where the multiplication factor (1 + ε) defines the kinetic energy gain associated with the momentum injection. After some numerical tests, Bimbato et al. [

11] defined a set of NR = 21 rough points to compute the average velocity differences required to calculate the second-order velocity structure function of the filtered velocity field.

The viscous core is corrected in the following form [

11]:

3.2. The Velocity Field

The instantaneous velocity field is computed over every discrete point vortex from three contributions, namely the incident flow, source panels, and vortex cloud.

The contribution of the uniform flow of freestream velocity over the kth discrete point vortex is easily computed as follows:

The contribution of the solid surfaces, via source panels, over the kth discrete point vortex is obtained as follows [

24]:

where n represents the two components of the velocity vector, NP is the total number of source panels,

is the uniform source density, and

defines the nth component of the velocity induced at the kth discrete point vortex by the ith source panel.

The vortex cloud contribution is evaluated through the Biot–Savart law. Thus, the velocity induced over the kth discrete point vortex is computed as follows [

25]:

where n represents the two components of the velocity vector, NV is the total number of discrete point vortices,

is the strength of every discrete point vortex, and

corresponds to the nth component of the velocity induced by the jth discrete point vortex (of unitary strength) at the position of the kth discrete point vortex.

3.3. The Pressure Field

The drag and lift coefficient computation is based on Equation (4), and it starts with the following definition of stagnation pressure over every pivotal point:

where

,

is the static pressure, ρ is the fluid density, and

is the velocity. The solution to Equation (4) is obtained in accordance with the following integral formulation [

26]:

such that the pressure field can be calculated at fluid domain points of interest, in which

for points of the fluid domain and

for points over solid surfaces,

is the fundamental solution to the Laplace equation, and

represents the normal unit vector pointing from a solid surface to the fluid domain.

Equation (19) presents the static pressure distribution over the NP pivotal points as an unknown value. The static pressure is then obtained by solving a linear system of algebraic equations. The solution to Equation (19) also enables the computation of drag and lift coefficients as follows, respectively [

11,

12]:

where

is the reference pressure far from the solid boundaries, C

pi is the pressure coefficient,

represents the length of the ith flat panel, and

is the anti-clockwise orientation angle of the same flat panel.

It should be noted that the pressure field is instantaneously computed only after the boundary conditions (Equations (6) and (7)) are verified over the pivotal point of every flat panel.

3.4. The Advective Problem

The advective problem is governed by Equation (9) and, therefore, the advective motion of every discrete point vortex is determined by the integration of every vortex path equation, which can be written using an explicit Euler scheme [

27] as follows:

where dt is interpreted as time stepping, i.e.,

, in which its value is evaluated from an estimate of the velocity and advective length of the flow [

11,

12,

18]. A purely Lagrangian description does not require the explicit treatment of advective derivatives [

28].

3.5. The Diffusive Problem and Turbulent Motions

The turbulent motions are considered through the concept of the local eddy viscosity coefficient, ν

t; see Equations (3), (10), (13) and (25). The eddy viscosity coefficient is instantaneously calculated at the position of every discrete point vortex, being defined as follows [

11,

29]:

where C

k = 1.4 is the Kolmogorov constant, σ

0 is the viscous core of the ith point vortex, and

is the local second-order velocity structure function of the filtered field [

9,

29], as follows:

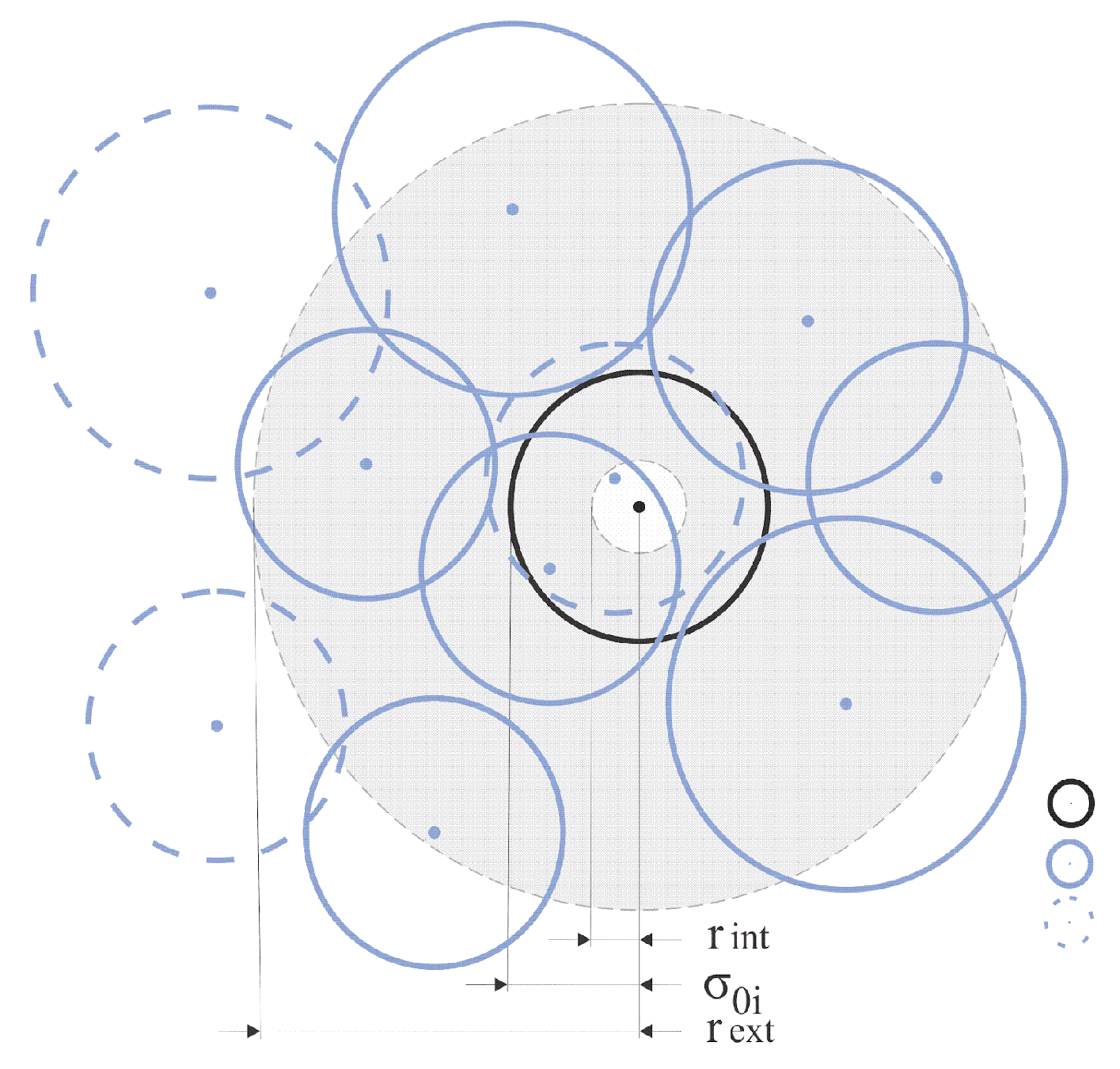

where the summation is calculated by counting the number N of discrete point vortices located inside of an annulus, where

defines the distance between the center of the annulus (center of the ith viscous core under analysis) and centers of other discrete point vortices placed between the internal (r

int) and the external (r

ext) radius of the same annulus [

9,

11], as illustrated in

Figure 4.

In

Figure 4, the circle in black defines the viscous core of the discrete point vortex under analysis; the circles in blue with solid lines represent discrete point vortices inside of the annulus; and the circles in blue with dashed lines represent discrete point vortices not contributing to the calculation of the local second-order velocity structure function of the filtered velocity field associated with the ith viscous core related to vortex i.

The vorticity diffusion (or molecular diffusion due to the viscosity effect) is computed using a statistical technique known as the Random Walk Method (RWM). Thus, the diffusive motion of every discrete point vortex is evaluated in the following manner [

6,

9]:

where P and Q are random numbers between 0.0 and 1.0. P and Q are also random displacements with mean equal to zero and a variance given by twice the product of the kinematic viscosity and time.

The convergence of the advection and diffusion problems was previously demonstrated by Carvalho et al. [

30].

Finally, the LVM algorithm, described in this section, was implemented using an in-house code via parallel computing (OpenMP). The steps are as follows:

- (i)

Initial specifications of the problem geometry (

Figure 1) including NP pivotal points and starting flow.

- (ii)

Generation of NP source flat panels to ensure the impermeability condition on pivotal points of both cylinder and ground plane surfaces including mass conservation.

- (iii)

Generation and shedding of M discrete point vortices with no roughness model to ensure the no-slip condition only on pivotal points of the cylinder surface, including global circulation conservation.

- (iv)

Correction for viscous core and vortex strength of all nascent discrete point vortices because of surface roughness effect; imposition of the no-slip condition (Equation (7)) and the global circulation conservation on every pivotal point due to incident flow, source panels, vortex cloud, and cylinder oscillation velocity (Equation (2)), and use of Equation (13).

- (v)

Computation of the velocity field at every discrete point vortex in the real plane (i.e., for y > 0), as sketched in

Figure 1.

- (vi)

Computation of the distributed and integrated aerodynamic loads.

- (vii)

Advection of the cluster of discrete point vortices.

- (viii)

Computation of turbulent motions near every discrete point vortex.

- (ix)

Vorticity diffusion using the RWM with LES theory.

- (x)

Reflection of discrete point vortices that accidentally migrate inside the cylinder and ground plane.

- (xi)

Cylinder oscillation in accordance with Equation (1).

- (xii)

Computation of the velocity field at every pivotal point to ensure the no-slip condition and, consequently, to obtain a new generation of discrete point vortices. This computation includes the contribution of the incident flow, vortex cloud, and oscillatory motion of the cylinder (see Equation (2)).

- (xiii)

Advance time by Δt.