Abstract

The development of high-performance solid-state energy storage devices is constrained by the limited ionic conductivity of gel electrolytes. To address this challenge, an inductively coupled nitrogen plasma (ICP) surface modification strategy was applied to poly(vinyl alcohol)–potassium hydroxide (PVA–KOH) gel electrolytes. The optimal plasma treatment parameters (150 W, 20 s) were identified based on ionic conductivity measurements. Comprehensive characterization confirmed that plasma treatment effectively introduced nitrogen-containing polar functional groups on the gel surface, induced surface nitrogen doping, increased surface roughness, and disrupted the hydrogen bond network. These synergistic microstructural modifications and chemical modifications increased interfacial polarity and facilitated ion transport, resulting in a 26% enhancement in the ionic conductivity compared with the pristine gel. Solid-state supercapacitors fabricated with the optimized gel electrolyte exhibits improved energy density, enhanced rate capability, and reduced interfacial impedance. These findings demonstrate that nitrogen-induced ICP treatment is an effective surface engineering strategy for improving gel electrolyte performance and advancing solid-state supercapacitor technologies.

1. Introduction

In recent years, driven by the global transition towards renewable energy and the rapid advancement of flexible wearable electronics, solid-state energy storage devices have emerged as a focal point of intensive research [1,2]. Among these devices, solid-state supercapacitors have garnered significant attention due to their inherent safety and structural flexibility [3,4,5]. Compared with conventional liquid electrolytes, which suffer from critical limitations such as leakage volatilization, and poor mechanical stability, solid-state electrolytes enhance device safety and long-term reliability while enabling improved mechanical flexibility [6,7,8]. However, commercialization of solid-state supercapacitors is still hindered by the limited ionic conductivity of solid electrolytes, which results in insufficient electrode–electrolyte interfacial contact and sluggish ion transport efficiency [6,9]. These limitations lead to high interfacial resistance, reduced ionic conductivity and poor rate performance in practical devices. Therefore, developing advanced electrolyte design strategies that optimize electrode–electrolyte interactions and enhance ion transport efficiency has become a critical research direction in this field [10,11].

Gel electrolytes, which immobilize liquid electrolytes within three-dimensional polymer networks through bicontinuous structures, are considered promising electrolytes for next-generation applications [12,13]. Among them, poly(vinyl alcohol) (PVA)-based gel electrolytes have been extensively investigated owing to their excellent film-forming ability, chemical stability, mechanical flexibility, and environmental friendliness [14,15]. The abundant hydroxyl (–OH) groups along the PVA polymer chains readily form hydrogen bonds with water molecules, effectively confining the aqueous electrolyte within the polymer matrix. As a result, PVA-based gel polymer electrolytes (PVA-GPEs) exhibit relatively high ionic conductivity while maintaining good mechanical integrity and processability [13,16]. Nevertheless, strong interchain hydrogen bonding and partial crystallinity in conventional PVA gels restrict polymer segment mobility and hinder ion migration, thereby limiting room-temperature ionic conductivity and interfacial ion transport performance [17].

To overcome these limitations, various strategies have been explored to enhance ion transport in PVA-based gel electrolytes, including polymer blending, incorporation of inorganic fillers, chemical crosslinking, and structural regulation [18,19,20]. Although these approaches can improve ionic conductivity to some extent, they often introduce additional challenges, such as compromised mechanical flexibility, increased interfacial resistance, or complex fabrication processes. Surface engineering has emerged as an effective alternative strategy for modulating electrolyte properties without altering the bulk composition [4,6]. By selectively modifying surface chemistry and microstructure, surface treatments can improve interfacial compatibility, increase surface polarity, and facilitate ion transport while preserving the intrinsic properties of the gel electrolyte.

Plasma treatment is a versatile and environmentally friendly surface modification technique that enables precise control over surface chemistry and morphology under mild conditions. In particular, inductively coupled plasma (ICP) systems offer high plasma density, uniform treatment, and low ion bombardment energy, making them suitable for modifying polymer-based materials [21,22]. By precisely controlling ICP parameters (power, treatment duration, and working gas, e.g., Ar, O2, N2), physical etching can increase material surface area and roughness. For instance, Adusei et al. enhanced fiber specific surface area via O2 plasma treatment [23]. Additionally, reactive plasma species can bombard polymer chains to introduce oxygen- or nitrogen-containing polar functional groups; Pi et al., for instance, grafted polar groups onto carbon fabric surfaces using N2 plasma [24]. This synergistic physical–chemical modification is hypothesized to construct efficient ion transport pathways on PVA gel surfaces while reducing electrolyte–electrode contact resistance. Notably, most plasma-based studies focus on electrode modification [25], with limited research on plasma treatment (especially ICP) for solid electrolyte surface engineering. While atmospheric-pressure O2 plasma treatment of PVA films for supercapacitors has been explored [26], systematic investigations into the effects of plasma on PVA gel electrolyte conductivity and device interfacial resistance remain scarce—representing a critical gap for innovative exploration.

In this study, an inductively coupled nitrogen plasma (N2-ICP) treatment was applied to PVA–KOH gel electrolytes to enhance their ionic transport properties. By systematically optimizing plasma power and treatment time, the effects of nitrogen plasma modification on surface chemistry, microstructure, ionic conductivity, and electrochemical performance were investigated. Results demonstrate that N2-ICP treatment effectively introduces nitrogen-containing polar groups, increases surface roughness, and disrupts hydrogen bond networks, thereby constructing enhanced ion transport pathways. Under optimal conditions, the ionic conductivity of modified gels is improved by ~26% relative to pristine samples. Solid-state supercapacitors assembled with these electrolytes exhibit significantly reduced interfacial impedance and a high specific capacitance of 161.6 F·g−1. This work provides a simple and scalable surface-engineering strategy for improving gel electrolyte performance and advancing solid-state energy storage technologies.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Preparation of PVA-KOH Gel Electrolyte and Nitrogen Gas Inductively Coupled Plasma Treatment

To enhance the electrochemical performance of PVA gel electrolytes, this study employed nitrogen inductively coupled plasma (N2-ICP) technology to surface-modify PVA-KOH gel electrolytes under various process conditions.

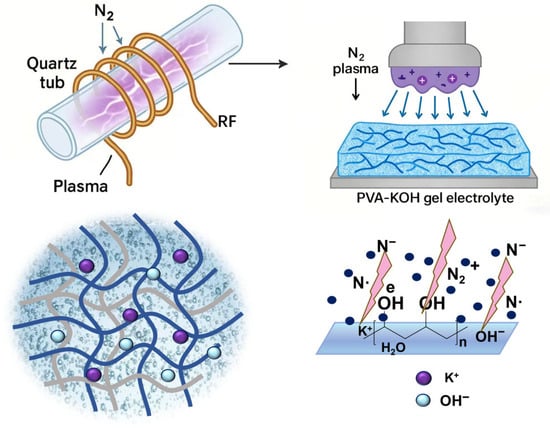

The PVA-KOH gel electrolyte was prepared by dispersing PVA-124 powder in deionized water, mixing it with a specific concentration of KOH solution, and then undergoing freeze–thaw (see Section 4.2 for detailed preparation methods) [19,27]. The internal structure of the gel electrolyte is roughly depicted in the lower left of Figure 1. After obtaining the gel electrolyte, the sample was placed in the center of a quartz tube reaction chamber. Under low-pressure conditions, nitrogen gas was introduced, and both surfaces of the gel electrolyte were exposed to discharge, yielding the modified NPK series of gel electrolytes (see Section 4.2 for specific preparation methods and conditions). The specific plasma treatment apparatus and process are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Schematic Diagram of Nitrogen Gas Electromagnetic-Coupled Plasma Treatment of PVA-KOH Gel Electrolyte.

2.2. Ionic Conductivity Assessment and Process Parameter Screening Based on EIS

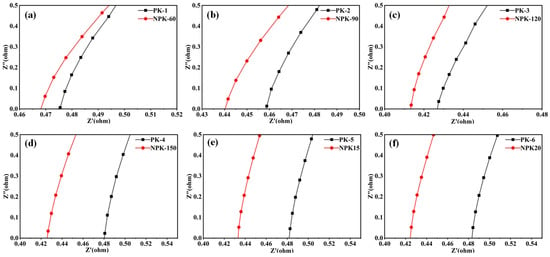

To determine the optimal plasma treatment parameters, we systematically investigated the effects of varying treatment power and duration on the ionic conductivity of PVA-KOH gel electrolytes. Specifically, we employed a symmetrical 304 stainless steel current collector as the blocking electrode and measured the ionic conductivity of the gel electrolyte using the AC impedance method (EIS) [28]. The Nyquist plots of all gel electrolytes are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Comparison of Nyquist plots for PVA-KOH gel electrolytes under different N2 plasma treatment conditions. (a–f) Nyquist plots of PVA-KOH gel electrolytes at varying plasma treatment power/time: (a) PK-1 and NPK-60, (b) PK-2 and NPK-90, (c) PK-3 and NPK-120, (d) PK-4 and NPK-150, (e) PK-5 and NPK-15, (f) PK-6 and NPK-20.

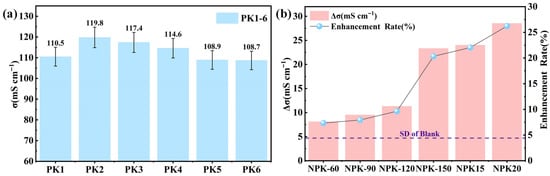

To accurately evaluate the plasma treatment effect, a paired control experimental design was adopted in this study. Figure 3a shows the distribution of ionic conductivities of six parallel-prepared blank samples (PK1–PK6), with a standard deviation of 4.7 mS·cm−1. The conductivity fluctuation (standard deviation of 4.7 mS·cm−1) shown in Figure 3a indicates that even when following the exact same preparation process, the PVA-KOH gels still have intrinsic microstructural differences. These differences are likely due to the freeze–melt process. During the freeze–melt process, the nucleation, growth orientation, and subsequent melting behavior of ice crystals are highly uncertain. This leads to microscopic differences in the porous network formed by ice crystal templates in the gel, including pore size distribution, connectivity, and pore wall structure. These preparation-induced inhomogeneities are the main cause of the initial fluctuation in gel ionic conductivity. To ensure that the conclusions about the plasma treatment effect are not disturbed by this initial fluctuation, we adopted a key strategy: instead of directly comparing the absolute conductivities of different samples after treatment, we precisely calculated the conductivity change (Δσ) before and after treatment for each sample. Based on this, Figure 3b shows the absolute improvement values (Δσ) and relative enhancement rates under all treatment conditions.

Figure 3.

The influence of plasma treatment on the ionic conductivity of PVA-KOH gel electrolyte: (a) The distribution of ionic conductivity of blank PVA-KOH gel and its inherent fluctuation. (b) The increase value (Δσ) and relative increase rate of ionic conductivity of PVA-KOH gel under different treatment conditions.

As shown in Figure 2a–d, by extracting the bulk resistance (Rb) from the Nyquist plots and calculating the conductivity, it was found that as the power increased from 60 W to 150 W, Δσ significantly increased from 8.1 mS·cm−1 to 23.3 mS·cm−1, and the relative improvement rate increased from 7.3% to 20.3% (the corresponding samples are marked as NPK-60 to NPK-150). The improvement value at 150 W far exceeded the intrinsic fluctuation of the samples (4.7 mS·cm−1). This indicates that power is the key influencing factor, and 150 W is the optimal power condition.

Under the optimal power of 150 W, we further investigated the effect of processing time (15 s, 20 s, samples marked as NPK15 and NPK20). As shown in Figure 2e,f and Figure 3b, extending the processing time from 10 s to 20 s, Δσ further increased from 23.3 mS·cm−1 to 28.5 mS·cm−1, with a relative improvement rate of 26.2%. To rigorously assess the significance of the time effect, we compared the differences in Δσ corresponding to different processing times with the intrinsic fluctuation (4.7 mS·cm−1). Compared with 10 s, the improvement value at 20 s increased by 5.2 mS·cm−1, clearly exceeding the system fluctuation, indicating that the 20 s treatment was better. However, the improvement value between 20 s and 15 s was 4.5 mS·cm−1, close to the system fluctuation (4.7 mS·cm−1). This suggests that the improvement range from 15 s to 20 s is approaching saturation, and the benefit of extending the processing time is limited.

In summary, the inductively coupled plasma (ICP) treatment can significantly enhance the ionic conductivity of gel electrolytes, with the treatment power (150 W) being the key parameter affecting the modification effect. Under this optimal power condition, a treatment duration of 20 s shows a more significant increase in conductivity compared to 10 s. Based on the experimental validation of effectiveness and stability, this study determines 150 W–20 s as the main research conditions for subsequent experiments.

2.3. Surface Chemistry Analysis of Gel Electrolytes Based on FTIR and XPS

To investigate the mechanism behind the enhancement of PK ion conductivity, we employed Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) and X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) to examine the differences in surface chemical composition before and after plasma treatment of the PVA-KOH gel electrolyte.

2.3.1. FT-IR Analysis

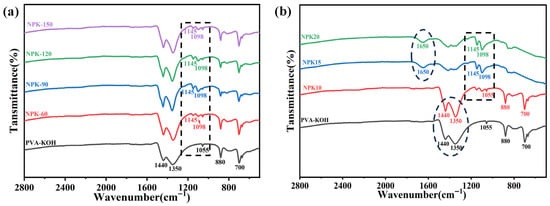

Figure 4 shows the Fourier Transform Infrared (FT-IR) spectra of different gel electrolytes in the mid-infrared fingerprint region (2800–500 cm−1). FT-IR can reveal changes in the plasma-treated PVA-KOH gel at the molecular vibration level. First, absorption peaks at 1440, 1350, and 880 cm−1—all characteristic of PVA are observable in the FTIR spectra of both the PVA-KOH gel electrolyte and the original PK sample under different treatment powers [29,30]. Specifically, the peaks at 1440 and 1350 cm−1 correspond to the bending vibration of –CH2 groups and the deformation vibration of C–H bonds in the PVA backbone, respectively. The peak at 880 cm−1 is attributed to the C–C stretching vibration along the carbon chain backbone of PVA.

Figure 4.

Effect of plasma treatment power and time on the FT-IR of PVA-KOH gel electrolyte: (a) FT-IR changes in PVA-KOH gel electrolyte under different plasma treatment powers, (b) FT-IR changes in PVA-KOH gel electrolyte under different plasma treatment times.

In Figure 4a, FTIR spectra exhibit systematic variations in the 1000–1200 cm−1 range under different treatment powers (fixed time of 10 s). All plasma-treated samples display new absorption peaks near 1098 and 1145 cm−1. Specifically, the peaks at 1145 and 1098 cm−1 are typically attributed to asymmetric C–O–C stretching vibrations [31]. Here, they correspond to the dehydration reaction between PVA molecular chains under plasma bombardment, where partial hydroxyl groups dehydrate to form ether bonds. In a nitrogen atmosphere, the peak intensity at 1145 cm−1 may also be indirectly related to C–N bond formation (a secondary effect). Nitrogen doping likely alters the local chemical polarity of the electrolyte, thereby enhancing the infrared activity of C–N bonds. The emergence of these two new peaks suggests that N2-ICP treatment successfully introduced new oxygen- or nitrogen-containing polar functional groups into the gel network, which is expected to enhance interactions between the gel and K+ ions.

As the plasma treatment time increases, NPK15 and NPK20 exhibit infrared characteristic peaks that are entirely distinct from those of the power group. The results infer that extending the nitrogen plasma treatment time can significantly alter the surface chemical state of the PVA-KOH gel. FTIR analysis indicates that as the treatment time increases from 10 s to 20 s, the absorption peaks at 1098 cm−1 (C-O-C stretching vibration) and 1145 cm−1 (C-N stretching vibration) progressively intensify. This indicates an increase in the number of surface ether bonds and an enhancement of nitrogen doping levels.

New absorption peaks appear near 1650 cm−1 in the NPK15 and NPK20 samples, likely corresponding to N-H bending or C=N stretching vibrations [32]. This indicates that plasma treatment generated more complex amine or imine functional groups on the gel surface. Moreover, the characteristic peaks of PVA’s intrinsic CH2 bending (~1440 cm−1) and C-C backbone vibrations (~880, 700 cm−1) were significantly weakened or even eliminated. This indicates that the polymer surface structure underwent chemical restructuring (possibly cross-linking) and etching under prolonged plasma exposure [33,34]. It should be noted that the 1650 cm−1 peak in NPK15 and NPK20 samples may also contain minor contributions from C=O vibrations, originating from oxidation of the highly reactive surface by air following plasma activation. Collectively, these changes indicate that treatment duration is a key parameter governing the type, doping level, and chemical composition of nitrogen functional groups on the gel surface. These phenomena further provide a chemical explanation for the observed increase in gel ionic conductivity with extended treatment time.

In FTIR analysis, we observed that nitrogen ICP treatment significantly altered the surface chemical composition of PVA-KOH gel, especially introducing chemical bonds potentially associated with nitrogen. To explain this observation and verify the form of nitrogen present, we performed X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) characterization on PK and NPK20 samples.

2.3.2. XPS Analysis

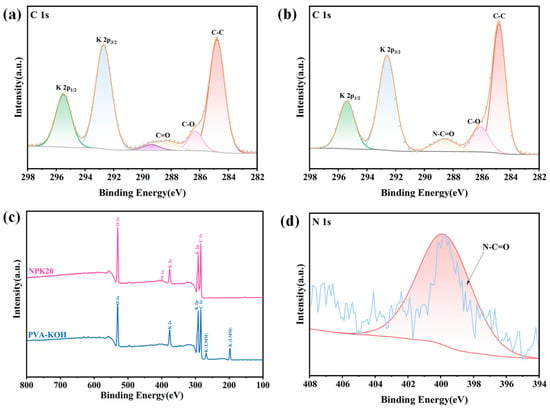

Figure 5a,b show the C1s spectra of PK and NPK20 gel electrolytes, respectively. After charge calibration, the peak at 284.8 eV in Figure 5a corresponds to the C–C bond in the PVA backbone. A characteristic PVA binding energy signal at 286.1 eV is observed, attributed to the abundant primary hydroxyl groups (–CH2–OH) along the PVA molecular chain [35]. Concurrently, residual carbonyl groups from incompletely hydrolyzed vinyl acetate in the PVA sample produce weak peaks at 288.0 eV and 289.4 eV [36]. Moreover, the distinct K 2p double peak (292.6 eV and 295.6 eV) confirms the enrichment of potassium ions (K+) on the gel surface. These K+ ions exhibit strong interactions with PVA hydroxyl groups and water molecules [37]. Figure 5b shows that after 150 W, 20 s plasma treatment, a new peak appears at 288.7 eV in the C1s spectrum of the NPK20 gel electrolyte. This binding energy is characteristic of the carbonyl carbon in amide groups (–N–C=O). This new peak correlates with the 1650 cm−1 peak in the aforementioned infrared spectrum, confirming our previous conjecture that reactive nitrogen species within the plasma chamber have doped the carbon backbone of the PVA surface. To further elucidate the variations in surface chemical states, we analyzed the high-resolution O 1s spectrum (see Supplementary Figure S3). This spectrum provides corroborative evidence from the oxygen element for the carbonyl carbon signal (288.7 eV) in the C1s spectrum, which is assigned to the amide group (-N-C=O). Simultaneously, the pre-treatment C=O (288.0 eV) and O–C=O (289.4 eV) peaks completely disappear, indicating that plasma etching effectively removed unstable oxide layers or impurities from the surface.

Figure 5.

XPS of PVA-KOH Gel Electrolyte Before and After Plasma Treatment: (a) C1s spectrum of PVA-KOH gel electrolyte. (b) C1s spectrum of NPK20 gel electrolyte. (c) Full XPS spectrum of PVA-KOH and NPK20. (d) N1s spectrum of NPK20 gel electrolyte.

Figure 5c shows a comparison of the full XPS spectra for the PK and NPK20 gel samples. The figure clearly displays the main peaks and Auger peaks for C, O, and K elements. The characteristic peaks with binding energies of 198.8 and 268.8 eV are attributed to the K(LMM) Auger peak, confirming the enrichment of K+ on the gel surface. Following nitrogen plasma treatment, both potassium Auger peaks completely disappeared, while a N 1s signal at 399.8 eV appeared in the full spectrum. This phenomenon directly indicates that the plasma treatment process successfully introduced nitrogen while simultaneously etching away the potassium salts from the material’s outermost layer. Fitting the high-resolution N 1s spectrum of the NPK20 sample yielded Figure 5d, revealing an asymmetric broad peak at 400.0 eV [38]. This energy range is characteristic of N 1s signals from nitrogen-containing functional groups such as amines, amides, and imines, further corroborating our earlier inference regarding nitrogen doping. In summary, XPS analysis indicates that nitrogen plasma treatment successfully achieved nitrogen-doped modification on the PVA-KOH gel surface, forming a thin layer rich in C-N and amide bonds.

To distinguish the respective contributions of physical bombardment and chemical doping in plasma modification, we conducted a control experiment: the gel was treated with argon (Ar) plasma under the same process parameters (150 W, 20 s), and the sample was labeled APK20. The full XPS spectrum and high-resolution N 1s spectrum of APK20 (see Supplementary Figure S1) showed that Ar plasma treatment only exerted physical cleaning and etching effects (the surface K+ signal was significantly weakened) without introducing any nitrogen signal. Critically, this difference in chemical composition directly led to a divergence in performance. Although Ar plasma treatment could slightly improve interface contact through physical cleaning (its conductivity data are provided in Supplementary Table S1), the NPK20 sample exhibited significantly higher ionic conductivity (Figure 3 in the main text). This strongly demonstrates that the surface chemical modification (i.e., nitrogen doping) induced by nitrogen plasma treatment is the dominant factor enhancing the ionic conductivity of the PVA-KOH gel, outweighing the contribution of pure physical effects.

Combined FTIR and XPS analysis revealed that nitrogen plasma treatment precisely modified the surface of PVA-KOH gel through the synergistic effects of physical bombardment and chemical reactions. First, it removes surface potassium salts while breaking C–H and C–O bonds in PVA chains to introduce nitrogen-containing functional groups like amino and amide groups. And the surface polymer chain structure has undergone significant reorganization. Ultimately, an ultra-thin polymer-modified layer is formed on the material surface. This layer not only helps maintain the gel’s high ionic conductivity but also holds promise for optimizing its interface compatibility and stability with electrodes. The above provides a critical interfacial foundation for comprehensively enhancing the performance of solid-state supercapacitors.

2.4. Structural Analysis of Gel Electrolytes

Through FTIR and XPS analysis in the preceding section, we observed that nitrogen ICP treatment achieved chemical modification of the gel surface via nitrogen doping and functional group introduction. The process also revealed that plasma interaction with the material extends beyond chemical modification to include significant physical etching effects, as evidenced by XPS analysis. So how to select characterization techniques to analyze the phase structure and morphology of gel electrolytes is crucial for understanding the enhancement of their ionic conductivity. To this end, we sequentially employed scanning electron microscopy (SEM) to analyze the morphology of the gel electrolyte, X-ray diffraction (XRD) to investigate the crystallization behavior of the samples, and Raman spectroscopy combined with FTIR in the 500–4000 cm−1 wavenumber range to analyze the internal hydrogen bonding within the gel electrolyte.

2.4.1. SEM Analysis

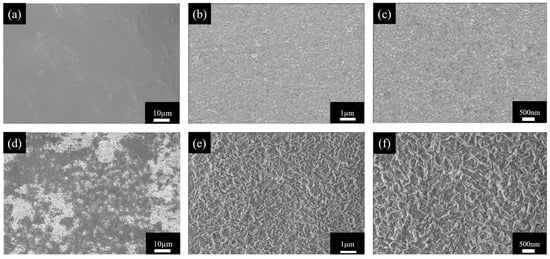

We first systematically characterized the surface morphology of the gel before and after modification using scanning electron microscopy (SEM), with results shown in Figure 6. Figure 6a–c displays the surface morphologies of the pristine PVA-KOH gel electrolyte (PK) after simple water washing and freeze-drying, with resolutions of 10 µm, 1 µm, and 500 nm, respectively. The pristine gel exhibits an overall smooth and dense surface, featuring only minor micrometer-scale wrinkles formed by drying shrinkage, characteristic of a typical homogeneous hydrogel structure.

Figure 6.

SEM images of PVA gel electrolyte at different resolutions: (a–c) Surface morphology of PVA-KOH gel: (a) 10 µm, (b) 1 µm, (c) 500 nm. (d–f) Surface morphology of NPK20 gel after plasma treatment: (d) 10 µm, (e) 1 µm, (f) 500 nm.

In contrast, the surface morphology of the sample treated with (150 W/20 s) nitrogen ICP and similarly freeze-dried (NPK-20) underwent significant changes Figure 6d–f. A frosted texture is observable even under low magnification. High-magnification images further reveal that the surface consists of numerous nanoscale protrusions and pores, exhibiting distinct roughening and porosity. This morphological transformation resulted from the physical bombardment and etching of the gel surface by high-energy particles within the plasma. The increased surface roughness implies a significant enhancement in the gel’s effective specific surface area during actual electrode–electrolyte contact. This provides more sites and shorter diffusion paths for ion transport. Such an increase in gel surface area facilitates reduced interfacial impedance and enhanced charge transfer efficiency. Through SEM analysis, we find that the gel’s surface physical morphology has been optimized. This optimization will synergize with the chemical modification discussed in Section 2.3, collectively forming the physical basis for the enhanced ionic conductivity of the gel.

2.4.2. XRD and Raman Analysis

To investigate whether the plasma’s influence extends into the material’s interior and alters its intrinsic structure, we systematically analyzed the gel’s crystal structure and chemical bonding state at two levels: long-range order and molecular vibrations.

We employed X-ray diffraction (XRD) to investigate the crystallization behavior of the material. Raman spectroscopy to characterize changes in the polymer’s internal carbon chains and hydrogen bond network. We aim for the combined analysis to comprehensively elucidate the mechanism by which plasma treatment affects the structure of PVA-KOH gel. The relevant results are shown in Figure 7a–c.

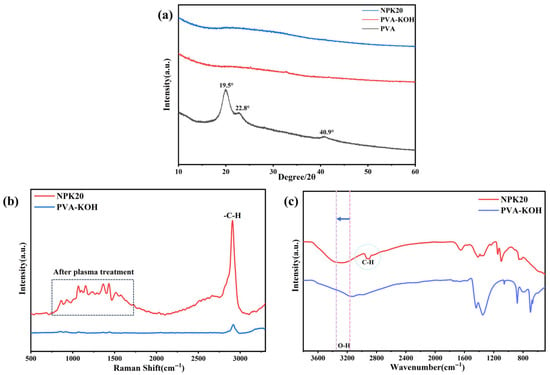

Figure 7.

Structural characterization of PVA-KOH gel electrolyte before and after modification: (a) XRD patterns of PVA, PVA-KOH, and NPK20; (b) Raman spectra; (c) FTIR spectra.

XRD analysis in Figure 7a first revealed the effect of KOH on the crystallization behavior of PVA gel. Pure PVA exhibits typical semi-crystalline characteristics, with diffraction peaks attributable to the (101), (200), and (111) crystal planes observed at 2θ ≈ 19.5°, 22.8°, and 40.9°, respectively [39]. These peaks originate from the dense hydrogen-bond network between PVA molecular chains. Following KOH incorporation, the XRD pattern of the PVA-KOH gel (PK) undergoes fundamental changes: all sharp crystalline peaks disappear completely, replaced by a broadened, significantly weakened diffuse peak around 19.5°. This indicates that K+ and OH− ions act as plasticizers, completely disrupting the original crystalline regions of PVA and transforming the system into an amorphous state. Notably, after 150 W, 20 s nitrogen plasma treatment, the XRD pattern of the NPK-20 sample almost completely overlapped with that of PK, showing no new diffraction peaks or significant peak position shifts. The XRD results infer that plasma treatment did not alter the bulk long-range ordered structure of the gel. Based on the previous SEM, XPS and FT-IR results, the plasma modification effect is mainly concentrated on the surface and near-surface regions of the gel.

To obtain further evidence of physical state changes in the samples, we performed Raman spectroscopy analysis on the gel electrolyte before and after modification. The Raman spectra Figure 7b revealed subtle evolutions in the surface-localized structure at the molecular vibrational scale.

In the untreated PK gel Raman spectrum, only one prominent peak is observed at 2910 cm−1, which is assigned to the C–H stretching vibration of the (–CH2) group in the PVA structural unit. Beyond this peak, signals in other spectral regions are faint, presenting as a flat baseline. This phenomenon indicates that intrinsic vibrations of PVA molecular chains are strongly suppressed in the pristine PVA-KOH composite system. This behavior is attributed to the formation of a dense and robust hydrogen-bond network between high-concentration KOH and PVA hydroxyl groups. Such intense intermolecular interactions not only restrict the vibrational degrees of freedom of PVA main chains and side chains but may also reduce the Raman scattering cross-section of most vibrational modes by altering electron cloud distribution, thereby masking their characteristic signals. Following 150 W, 20 s nitrogen plasma treatment, the Raman spectrum of the sample underwent fundamental changes. In addition to a significant enhancement in the intensity of the C-H stretching vibration peak at 2910 cm−1, distinct characteristic peaks emerged at multiple positions including 856, 925, 1067, 1155, 1360, and 1430 cm−1. Based on literature comparisons, these newly observed peaks can be attributed as follows: the peaks at 856 and 925 cm−1 originate from the C–C backbone stretching vibrations of the PVA backbone; The peaks at 1067 and 1155 cm−1 correspond to C–O stretching and C–O–C vibrational modes; while the peaks at 1360 and 1430 cm−1 are attributed to CH2 bending and scissoring vibrations [40].

Based on the XRD results, the differences observed in the Raman spectra are primarily attributed to the relaxation of the intramolecular hydrogen bond network within the gel. To reinforce our perspective, Figure 7c presents the FTIR spectra of both samples in the 400–4000 cm−1 wavenumber range, enabling a combined infrared analysis of intramolecular hydrogen bond changes. It can be observed that the O-H stretching vibration peak of the gel shifts from 3150 cm−1 to the higher wavenumber range of 3240–3400 cm−1. indicating that plasma treatment weakened the strong hydrogen bonding between PVA and KOH. This opened the previously tightly constrained PVA molecular chains, restoring the Raman activity of skeletal vibrations (C–C, C–O) and CH2 deformation vibrations, thereby enabling the observation of abundant intrinsic vibration signals in the samples. The weakened hydrogen bonding enhanced the mobility of PVA segments, leading to an increase in the gel’s ionic conductivity [6,41].

In summary, the synergistic analysis of XRD and Raman spectroscopy indicates that plasma treatment weakens the surface hydrogen bond network while preserving the bulk amorphous structure. This releases the local motion freedom of polymer segments, thereby creating a more favorable microenvironment for ion transport in the surface region. This physical structural optimization synergizes with surface chemical modification, collectively contributing to the effective enhancement of ionic conductivity.

2.5. Analysis of the Electrochemical Performance of SSC Electrodes Assembled Using Modified Gel Electrolytes

In previous discussions, we observed that nitrogen ICP treatment significantly enhances the ionic conductivity of PVA-KOH gel through the synergistic effects of physical structure optimization and surface chemical modification. To validate the effectiveness of this material-level optimization in practical energy storage devices, symmetric supercapacitors (SSCs) were assembled using the original PK gel and the NPK-20 gel modified under optimal conditions as electrolytes, with activated carbon as the electrode. The two supercapacitors were designated SSC-1 and SSC-2 based on their respective gels, and their electrochemical performance was systematically compared. Detailed assembly procedures are provided in Section 4.4.

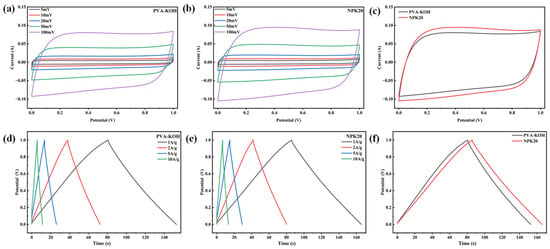

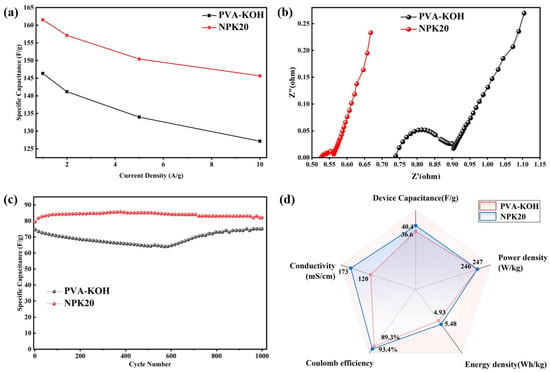

Figure 8 shows the cyclic voltammetry (CV) curves of the two devices at different scan rates and the constant current discharge (GCD) curves at various current densities. Within the scan rate range of 5 to 100 mV·s−1 Figure 8a,b, both devices exhibit nearly rectangular CV curves, indicating their predominant double-layer capacitive behavior. However, at the same scan rates, the NPK20-based device exhibits higher response currents. Particularly at the high scan rate of 100 mV·s−1 Figure 8c, SSC-2 maintains superior CV rectangularity with a more gradual current decline at the voltage window edges, indicating that the plasma-modified gel-assembled device demonstrates superior rate performance.

Figure 8.

Comparison of electrochemical performance between symmetric supercapacitors based on PVA-KOH and NPK20 gel electrolytes: (a,b) Cyclic voltammetry curves at different scan rates; (c) CV curve comparison at 100 mV·s−1; (d,e) constant current charge–discharge curves at different current densities; (f) GCD curve comparison at 1 A·g−1.

To further quantitatively compare device performance differences, Figure 8d,e shows constant-current charge–discharge curves at different current densities. At all tested current densities (1 to 10 A·g−1), the NPK20-based devices exhibited longer discharge times than SSC-1. Calculations based on GCD curves at 1 A·g−1 Figure 8f indicate that the plasma-treated device achieved a single-electrode mass-specific capacitance of 161.6 F·g−1, representing a 10.3% improvement over the 146.5 F·g−1 of the pristine device. Comparing capacity retention at different current densities (as shown in Figure 9a), SSC-1 exhibited only 86.8% capacity retention at 10 A·g−1 compared to 1 A·g−1, while SSC-2 achieved 89.8%. This indicates superior rate performance for devices assembled with NPK20. Notably, devices assembled with NPK20 exhibit lower voltage drop IR, attributed to the modified gel electrolyte’s reduced bulk and interfacial impedance.

Figure 9.

Comprehensive Evaluation and Comparison of Supercapacitor Performance Before and After Modification: (a) rate performance of specific capacitance; (b) Nyquist plots of SSC-1 and SSC-2; (c) long-term cycling stability at 1 A·g−1; (d) radar chart for comprehensive comparison.

To investigate the impedance characteristics of the devices in depth, we performed AC impedance spectroscopy (EIS) analysis, with results shown in Figure 9b. The Nyquist plots of both devices exhibit a straight line in the low-frequency region, characteristic of ideal double-layer capacitor behavior. However, their performance diverges significantly in the high-frequency region. The SSC-1 device based on the original PK electrolyte exhibits a discernible small semicircle at approximately 0.74 Ω in the real part of the impedance, transitioning thereafter to a 45° Warburg diffusion line. The minor semicircle in the PK sample’s Nyquist plot is typically attributed to weak charge transfer at the electrode–electrolyte interface. This may stem from unstable interface contact caused by potassium salt precipitation on the gel electrolyte surface, or from minor pseudocapacitive effects induced by surface oxygen-containing functional groups. In contrast, devices assembled with NPK-20 electrolyte exhibited near-ideal EDLC impedance response: the high-frequency region transitioned directly from the equivalent series resistance (ESR, ~0.526 Ω) to the 45° diffusion line without observable semicircular features [42]. This discrepancy indicates purer electrode–electrolyte interfaces in NPK-20-assembled devices. Combining the preceding analysis, we infer that plasma treatment likely eliminates interfacial defects through the following mechanisms: first, it removes surface impurities and unstable oxide layers; second, the introduced nitrogen-containing polar functional groups form stronger physical coupling with the activated carbon electrode, thereby suppressing non-ideal interfacial charge transfer. And plasma treatment significantly reduced the ESR from 0.739 Ω to 0.526 Ω, a decrease of 28.8%, indicating that the modified gel exhibits lower interfacial contact resistance and superior ion transport efficiency.

To test the devices’ cycle stability, we subjected two devices to 1000 charge–discharge cycles at a current density of 1 A·g−1. At 1 A·g−1, the NPK20 gel-assembled device demonstrated outstanding cycling performance (Figure 9c). Its discharge time gradually increased from an initial 78 s to 85.6 s, eventually stabilizing at 82 s after 1000 cycles. Capacity retention reached 105%, with coulombic efficiency consistently approaching 100%. This cycling performance correlates with the low impedance and stable interface revealed in EIS, indicating that plasma modification promotes sustained electrolyte wetting and electrochemical activation of the electrode. In contrast, the cycling process of the device based on the original PK gel exhibited instability: the discharge time rapidly decayed from 75 s to 64 s, partially recovering to approximately 75 s in the later stages. This “decay-recovery” phenomenon corroborates the semicircular pattern observed in the high-frequency region of PK’s EIS, reflecting unstable factors such as side reactions and poor contact at the original interface. Cycling tests further demonstrate that nitrogen ICP treatment not only reduces interfacial impedance but also constructs a more stable electrode–electrolyte interface, significantly enhancing the device’s long-term operational reliability. Following cycling stability testing, we calculated and compared the energy density and power density of both devices (Figure 9d). The NPK-20 gel-based device achieved an energy density of 5.5 W·h·kg−1 at a power density of 247 W·g−1, outperforming the SSC-1 device.

The electrochemical tests above demonstrate that the nitrogen plasma surface modification strategy can enhance the performance of SSC by optimizing the gel electrolyte.

3. Conclusions

This study employed nitrogen inductively coupled plasma (N2-ICP) technology to surface-modify PVA-KOH gel electrolytes. We systematically investigated the influence of plasma treatment power and duration on material structure and electrochemical performance, then applied the modified material in symmetric supercapacitors to validate its practical effectiveness.

First, we determined that 150 W and 20 s represent the optimal plasma modification conditions, under which the gel ionic conductivity increased by 26%. To elucidate the mechanism behind the enhanced gel ionic conductivity, FT-IR and XPS analyses revealed that the improvement stemmed from the introduction of surface-bound nitrogen-containing polar functional groups. The incorporation of these polar groups enabled the device to maintain wettability during long-term operation. Combined SEM and XRD analysis confirmed that modification primarily acted on the material surface. While significantly increasing surface roughness and effective specific surface area, the plasma treatment did not alter the amorphous structure of the gel phase. Comprehensive Raman and FT-IR analysis further revealed that plasma treatment loosened the hydrogen bond network on the gel surface, enhancing polymer chain mobility and creating a more favorable microenvironment for ion migration. Finally, we applied the modified gel to activated carbon symmetric supercapacitors, achieving comprehensive performance enhancements. Specifically, the single-electrode mass-specific capacitance increased by 11%, the equivalent series resistance decreased by 28.8%, and the effective ionic transport performance of the device improved by 44%. During long-term cycling tests, the modified device demonstrated excellent capacity retention and interfacial stability.

In summary, nitrogen ICP treatment represents an efficient, eco-friendly surface engineering strategy. This work provides novel insights for designing and fabricating high-performance, long-lifetime gel electrolytes, demonstrating the application potential of plasma technology in flexible energy storage devices.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

All chemicals and materials were used as received without additional purification. Specific details are as follows:

Chemical Reagents: Polyvinyl alcohol (PVA-124, Mw = 195,000 g/mol, >99% hydrolyzed, Shanghai Aladdin Bio-Chem Technology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China), Potassium hydroxide (KOH, AR, Shanghai Aladdin Bio-Chem Technology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China), Anhydrous ethanol (C2H5OH, AR, Sinopharm Group Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China).

Active Electrode Material: Activated carbon (YP-50F, Kuraray, Tokyo, Japan). Conductive Additive: Conductive carbon black (Super P Li, TIMCAL, Bodio, Switzerland). Binder: Polytetrafluoroethylene emulsion (PTFE, D210C, Daikin, Osaka, Japan). Current Collector: Foam nickel (NF, Shanghai Yan-Wen Technology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China).

Solvent: All water used was ultrapure with a conductivity of 2 µS/cm.

4.2. Preparation of PVA-KOH Gel Electrolyte

First, 3 g of polyvinyl alcohol (PVA-124) powder was dissolved in 25 mL of deionized water. The solution was then continuously stirred at more than 600 rpm in a 90 °C water bath for 90 min to ensure complete dissolution. Next, we slowly added 3 g of KOH, dissolved it in 6 mL of deionized water to the PVA solution, and continuously stirred for another 20 min to obtain a homogeneous PVA-KOH mixture (with both PVA and KOH at a concentration of 8.11 wt%). The mixture was then centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 8 min to remove entrapped air, poured the degassed mixture into a polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) mold with a depth of 2 mm and placed it in a sealed Petri dish to prevent water evaporation. The mold was then frozen at −25 to −30 °C for 180 min, and afterwords thawed at room temperature for at least 60 min. It was then demolded to obtain the initial PVA-KOH gel electrolyte. Finally, we placed the resulting gel in a sealed Petri dish and allowed it to undergo structural relaxation at ambient conditions for 12 h to ensure stable performance for subsequent testing.

4.3. N2 Inductively Coupled Plasma Treatment of PVA-KOH Gel Electrolyte

The radio frequency inductively coupled plasma (RF-ICP) system consists of two primary subsystems: the vacuum system and the plasma excitation system. The vacuum system comprises a gas delivery unit, a vacuum pump, and a quartz chamber designed to maintain low-pressure conditions. The plasma excitation system includes a radio frequency power generator, an impedance matching network, and a copper induction coil (n = 8) wound around the outer surface of the quartz tube. A cooling system is integrated into the apparatus to ensure that the reaction chamber temperature remains below 50 °C during plasma discharge, thereby maintaining thermal stability throughout the process. A schematic illustration of the experimental setup and plasma discharge configuration is provided in Figure 1.

In the experimental procedure, the gel lay on a porcelain boat with dimensions of 80 mm × 50 mm and positioned at the center of the induction coil, ensuring that the sample remained within 50 mm from the top of the coil. The system was then evacuated using a vacuum pump to achieve a pressure range of 15–20 Pa. High-purity nitrogen was introduced through a mass flow controller at a constant flow rate of 30 sccm. Plasma discharge was initiated once the pressure stabilized below 20 Pa. The RF power settings were predetermined prior to sample placement. Treatment duration was recorded starting from the moment of plasma ignition. Upon completion of the discharge process, the nitrogen flow and vacuum pump were sequentially shut down, after which the sample was retrieved and properly labeled. Both sides of the gel electrolyte have undergone plasma treatment. The marked time is the plasma treatment time on one side, and the treatment times on both sides are equal.

In this study, nitrogen-doped PVA-KOH materials (designated as NPK) were synthesized via the RF-ICP method. The system operated at a fixed frequency of 13.56 MHz, employing nitrogen as the process gas at a flow rate of 30 sccm, with the chamber pressure maintained between 15 and 20 Pa. PVA-KOH samples were subjected to nitrogen plasma treatment at RF powers of 60, 90, 120, and 150 W for a fixed duration of 10 s, yielding samples labeled as NPK-60, NPK-90, NPK-120, and NPK-150, respectively. To evaluate the influence of treatment time, additional experiments were performed at 150 W for durations of 15 s and 20 s, resulting in samples designated as NPK15 and NPK20.

4.4. Preparation of AC Electrodes and Assembly of Solid-State Supercapacitors

Preparation of Electrode Materials: In this work, commercial activated carbon (YP-50F, Kuraray) was employed as the primary active material, featuring a specific surface area of ~1692 m2/g, a median particle size (D50) of ~5.6 µm (with D10 = 1.9 µm and D90 = 9.7 µm), and a bulk density of 0.3 g/mL. Super P (specific surface area ~62 m2/g) served as the conductive additive to construct a high-efficiency 3D electronic conduction network within the electrode, thereby minimizing contact impedance. Initially, activated carbon and conductive carbon black were weighed in an 85:10 mass ratio and transferred to an agate mortar, followed by grinding for 30 min to achieve homogeneous mixing. Subsequently, polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) emulsion (60 wt%) was introduced as the binder, and anhydrous ethanol was added as the dispersant via dropwise mixing. The solid mass ratio of activated carbon, carbon black, and PTFE binder was strictly maintained at 85:10:5 throughout the process. After thorough grinding to form a viscous, dough-like mixture, the composite was repeatedly rolled using a film rolling machine to obtain a uniform thin film. The film was then pressed onto a nickel foam current collector under a pressure of 10 MPa. The resulting electrode sheets were first dried in an oven at 80 °C for 60 min, and subsequently transferred to a vacuum drying oven at 60 °C for 5 h to completely remove residual solvents. Finally, the electrode sheets were cut into 1.5 × 1.5 cm squares. Gravimetric analysis revealed that the areal loading of the active material was approximately 5 mg/cm2, with an electrode thickness of 0.15 mm.

Assembly of Solid-State Supercapacitors: Two as-prepared electrode sheets were used as the positive and negative electrodes, respectively. Approximately 30 µL of 6 M KOH solution was drop-cast onto the surface of each electrode to optimize electrode–electrolyte interfacial contact. A pre-fabricated PVA-KOH gel electrolyte (with dimensions slightly larger than the electrodes and a thickness of ~2 mm) was then placed between the two electrodes, and gentle pressing was applied to form an “electrode–electrolyte–electrode” sandwich structure. Finally, the assembly was wrapped with plastic film and hermetically sealed using a plastic heat sealer, yielding the solid-state supercapacitor device ready for electrochemical testing.

4.5. Characterization Methods for Gel Electrolyte Materials

The gel electrolyte was characterized using the following methods.

Field Emission Scanning Electron Microscopy (FE-SEM): The morphology and microstructure of the samples were characterized using a Zeiss Gemini SEM 500 field emission scanning electron microscope (Carl Zeiss AG, Oberkochen, Germany). Prior to analysis, all samples were freeze-dried at −70 °C for 24 h to ensure complete removal of moisture. To improve electrical conductivity, the dried samples were sputter-coated with a thin gold film for 60 s. Imaging was performed at an accelerating voltage of 2 kV.

X-ray Diffraction (XRD): The crystallization behavior of the materials was evaluated using a Panalytical X’Pert Powder X-ray diffractometer (Malvern Panalytical B.V., Almelo, The Netherlands). All samples were freeze-dried at −70 °C for 24 h prior to measurement. Data were collected using Cu Kα radiation over a 2θ range of 10° to 60°, with a scanning rate of 2°/min.

Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FT-IR): The chemical bonds and functional groups in the materials were analyzed using a Thermo Fisher Scientific Nicolet iS5 FT-IR spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA). All samples were freeze-dried at −70 °C for 24 h prior to measurement. Freeze-dried solid samples were directly analyzed using an Attenuated Total Reflection (ATR) accessory, and spectra were recorded over a wavenumber range of 4000–400 cm−1.

Raman Spectroscopy: Molecular vibrations and polymer chain structures were investigated using a Thermo Fisher Scientific DXR2xi confocal Raman microscope (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA). All samples were analyzed with a 532 nm laser excitation source under microscopic point-scanning mode, and Raman spectra were typically collected in the range of 100–3300 cm−1.

X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS): Surface elemental composition and chemical states were determined using a Thermo Scientific ESCALAB Xi+ X-ray photoelectron spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA). To satisfy the requirements of the high-vacuum analysis environment, hydrogel samples were pre-treated by freeze-drying to obtain solid forms. All samples were freeze-dried at −70 °C for 24 h prior to measurement. The resulting solids were mounted on conductive tape, transferred into the analysis chamber via a load-lock system, and analyzed under ultra-high vacuum conditions (<1 × 10−9 Pa). All binding energies were calibrated relative to the C1s peak of adventitious carbon.

Elemental Organic Analysis (CHNO/S): The elemental composition (C, H, N, O) of the samples was quantitatively determined using an Elementar vario MICRO cube elemental analyzer (Elementar Analysensysteme GmbH, Langenselbold, Germany). Prior to analysis, all samples were freeze-dried under vacuum at −70 °C for 24 h to completely remove moisture and obtain uniform, stable and representative solid powders.

4.6. Electrochemical Performance Testing

All electrochemical tests were conducted on an electrochemical workstation (CHI760E, Shanghai Chen-Hua Instruments Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China), using a standard two-electrode configuration. Tests employed a symmetrical supercapacitor device with a sandwich structure, secured using specialized fixtures where the reference electrode and counter electrode were clamped at one end and the working electrode at the other.

Detailed electrochemical testing methods, parameters, and formulas are provided in Supplementary Materials.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/gels12020109/s1, Supplementary characterization data: Figure S1: XPS spectra of the sample treated with argon plasma (APK20): (a) full XPS spectrum of PVA-KOH and APK20; (b) N1s spectrum of APK20 gel electrolyte. Figure S2: (a,b) surface of NPK20 electrolyte at 200 nm resolution, (c,d) cross-section of NPK20 electrolyte after liquid nitrogen brittle fracture at 200 nm resolution. Figure S3: (a) O1s spectrum of PVA-KOH gel electrolyte; (b) O1s spectrum of NPK20 gel electrolyte. Figure S4: (a) Raman Spectral changes in PVA-KOH gel electrolyte under different plasma treatment powers, (b) Raman Spectral changes in PVA-KOH gel electrolyte under different plasma treatment times. Table S1: Ionic conductivity of PVA-KOH gel electrolytes before and after plasma treatment. Table S2: Charge and discharge data of assembled solid-state supercapacitors. Table S3: The performance of assembled solid-state supercapacitors. Table S4: Elemental organic CHNS/O-analysis results of NPK20 gel electrolyte.

Author Contributions

Y.L.: Conceptualization, Study design, Investigation, Experimentation, Formal analysis, Data analysis, Interpretation, Writing—original draft, Writing—Review and Editing; G.C.: Supervision, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Resources provision, Writing—Review and Editing; S.F.: Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition, Resources provision, Writing—review & editing, Critical revision; W.D.: Experimentation, Study design, Visualization, Supervision, Project administration; J.S.: Supervision, Funding acquisition, Writing—Review and Editing; K.X.: Experimentation, Resources, Visualization; Z.W.: Study design, Visualization, Resources; J.T.: Experimentation, Study design, Visualization. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Hunan Provincial Key Research and Development Program: Development of Large-Scale High-Density Plasma Chemical Vapor Deposition Equipment, (the Key Research and Development Program of Hunan Province, No. 2024WK2023), July 2024–July 2026.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the editor for the supervision of the manuscript and the assistance provided in the process. We also thank the anonymous reviewers for their selfless efforts in offering numerous suggestions to help improve the quality of our article. We are grateful to Shaban Muhammad for his assistance in polishing the article. We acknowledge the use of DeepSeek-V3.2 to help organize the logic of this article and of Deepl Windows to translate the original Chinese manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Simon, P.; Gogotsi, Y. Perspectives for electrochemical capacitors and related devices. Nat. Mater. 2020, 19, 1151–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yip, B.R.P.; Chen, C.-F.; Jiang, Y.; Ohayon, D.; Bazan, G.C.; Wang, X.-H. Aqueous asymmetric pseudocapacitor featuring high areal energy and power using conjugated polyelectrolytes and Ti3C2Tx MXene. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 7984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, C.W.; Wu, C.A.; Hou, S.S.; Kuo, P.L.; Hsieh, C.T.; Teng, H. Gel electrolyte derived from poly(ethylene glycol) blending poly(acrylonitrile) applicable to roll-to-roll assembly of electric double layer capacitors. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2012, 22, 4677–4685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuaibu, A.D.; Shah, S.S.; Alzahrani, A.S.; Aziz, M.A. Advancing gel polymer electrolytes for next-generation high-performance solid-state supercapacitors: A comprehensive review. J. Energy Storage 2025, 107, 114851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.-W.; Woottapanit, P.; Geng, S.-N.; Chanajaree, R.; Shen, Y.; Lolupiman, K.; Limphirat, W.; Pakornchote, T.; Bovornratanaraks, T.; Zhang, X.-Y. A multifunctional quasi-solid-state polymer electrolyte with highly selective ion highways for practical zinc ion batteries. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.-Y.; Zhong, C.; Liu, J.; Ding, J.; Deng, Y.-D.; Han, X.-P.; Zhang, L.; Hu, W.-B.; Wilkinson, D.P.; Zhang, J.-J. Opportunities of flexible and portable electrochemical devices for energy storage: Expanding the spotlight onto semi-solid/solid electrolytes. Chem. Rev. 2022, 122, 17155–17239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubal, D.P.; Chodankar, N.R.; Kim, D.H.; Gomez-Romero, P. Towards flexible solid-state supercapacitors for smart and wearable electronics. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2018, 47, 2065–2129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Yu, M.; Wang, G.; Tong, Y.; Li, Y. Flexible solid-state supercapacitors: Design, fabrication and applications. Energy Environ. Sci. 2014, 7, 2160–2181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Wang, Q. Hofmeister effect-aided assembly of enhanced hydrogel supercapacitor with excellent interfacial contact and reliability. Small Methods 2019, 3, 1900558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alipoori, S.; Mazinani, S.; Aboutalebi, S.H.; Sharif, F. Review of PVA-based gel polymer electrolytes in flexible solid-state su-percapacitors: Opportunities and challenges. J. Energy Storage 2020, 27, 101072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Wu, D.; Shang, Y.; Shen, H.; Xi, S.; Wang, X.; Li, W.; Wang, Q. Regenerated hydrogel electrolyte towards an all-gel su-percapacitor. Sci. China Mater. 2022, 65, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Liu, H.; Yin, Q.; Wu, J.; Chen, P.; Zhang, G.; Liu, G.; Wu, C.; Xie, Y. A zwitterionic gel electrolyte for efficient solid-state supercapacitors. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 11782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Li, H.; Tang, Z.; Liu, Z.; Ruan, Z.; Ma, L.; Yang, Q.; Wang, D.; Zhi, C. Hydrogel electrolytes for flexible aqueous energy storage devices. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2018, 28, 1804560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Holze, R. Polymer electrolytes for supercapacitors. Polymers 2024, 16, 3164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, X.; Pan, J.; Zhao, Y.; Liao, M.; Peng, H. Gel polymer electrolytes for electrochemical energy storage. Adv. Energy Mater. 2018, 8, 1702184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, T.; Zou, Y.; Zhang, X.; Li, D.; Guo, X.; Yang, D. Hydrogen bond interpenetrated agarose/PVA network: A highly ionic conductive and flame-retardant gel polymer electrolyte. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 9856–9864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabhakaran, V.; Mehdi, B.L.; Ditto, J.J.; Engelhard, M.H.; Wang, B.; Gunaratne, K.D.D.; Johnson, D.C.; Browning, N.D.; Johnson, G.E.; Laskin, J. Rational design of efficient electrode–electrolyte interfaces for solid-state energy storage using ion soft landing. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 11399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Rouelle, N.; Qiu, A.; Oh, J.-A.; Kempaiah, D.M.; Whittle, J.D.; Aakyiir, M.; Xing, W.; Ma, J. Hydrogen bonding-reinforced hydrogel electrolyte for flexible, robust, and all-in-one supercapacitor with excellent low-temperature tolerance. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 37977–37985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Liu, J.; Song, Z.; Han, X.; Deng, Y.; Zhong, C.; Hu, W. Porous nanocomposite gel polymer electrolyte with high ionic conductivity and superior electrolyte retention capability for long-cycle-life flexible zinc–air batteries. Nano Energy 2019, 56, 454–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, H.; Zhang, J.; Cheng, H.; Hong, L.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, X. A high-voltage gel electrolyte with a low salt concentration for quasi-solid-state flexible supercapacitors. Energy Fuels 2022, 36, 9295–9302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.; Ming, F.; Alshareef, H.N. Applications of plasma in energy conversion and storage materials. Adv. Energy Mater. 2018, 8, 1801804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Zhang, L.-H.; Zhang, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, J.-L.; Fang, Z. The application of plasma technology for the preparation of supercapacitor electrode materials. Dalton Trans. 2024, 53, 5749–5769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adusei, P.K.; Gbordzoe, S.; Kanakaraj, S.N.; Hsieh, Y.-Y.; Alvarez, N.T.; Fang, Y.; Johnson, K.; McConnell, C.; Shanov, V. Fabrication and study of supercapacitor electrodes based on oxygen plasma functionalized carbon nanotube fibers. J. Energy Chem. 2020, 40, 120–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pi, X.; Sun, X.; Wang, R.; Chen, C.; Wu, S.; Zhan, F.; Zhong, J.; Wang, Q.; Ostrikov, K.K. MoS2 nanosheets on plas-ma-nitrogen-doped carbon cloth for high-performance flexible supercapacitors. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2023, 629, 227–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Chen, J.; Sun, S.; Huang, Z.; Zhang, X.; Li, X.; Dong, H. Plasma-enabled synthesis and modification of advanced materials for electrochemical energy storage. Energy Storage Mater. 2022, 50, 161–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.-H.; Jekal, S.; Kim, C.-G.; Chu, Y.-R.; Noh, J.; Kim, M.S.; Lee, N.; Song, W.-J.; Yoon, C.M. Facile enhancement of electrochemical performance of solid-state supercapacitor via atmospheric plasma treatment on PVA-based gel-polymer electrolyte. Gels 2023, 9, 351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Liu, J.; Ding, J.; Deng, Y.; Han, X.; Hu, W.; Zhong, C. Investigation of the environmental stability of poly (vinyl alcohol)–KOH polymer electrolytes for flexible zinc–air batteries. Front. Chem. 2019, 7, 678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.-J.; Wu, H.; Hu, Y.; Young, M.; Wang, H.; Lynch, D.; Xu, F.; Cong, H.; Cheng, G. Ionic conductivity of polyelectrolyte hydrogels. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 5845–5852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadiq, N.M.; Aziz, S.B.; Kadir, M.F.Z. Development of Flexible Plasticized Ion Conducting Polymer Blend Electrolytes Based on Polyvinyl Alcohol (PVA): Chitosan (CS) with High Ion Transport Parameters Close to Gel Based Electrolytes. Gels 2022, 8, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jipa, I.; Stoica, A.; Stroescu, M.; Dobre, L.-M.; Dobre, T.; Jinga, S.; Tardei, C. Potassium sorbate release from poly (vinyl alco-hol)-bacterial cellulose films. Chem. Pap. 2012, 66, 138–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korbag, I.; Mohamed Saleh, S. Studies on the formation of intermolecular interactions and structural characterization of poly-vinyl alcohol/lignin film. Int. J. Environ. Stud. 2016, 73, 226–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonia, J.; Viju, N.C.; Dsouza, R.; Venkadesh, A.; Naveen, M.H.; Prasad, K.S. Surface engineered low-cost paper electrodes for enhanced electrocatalytic activity. Electrochim. Acta 2024, 474, 143578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrebdi, T.A.; Ahmed, H.A.; Alrefaee, S.H.; Pashameah, R.A.; Toghan, A.; Mostafa, A.M.; Alkallas, F.H.; Rezk, R.A. Enhanced ad-sorption removal of phosphate from water by Ag-doped PVA-NiO nanocomposite prepared by pulsed laser ablation method. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2022, 20, 4356–4364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavitha, C.M.; Eshwarappa, K.M.; Shilpa, M.P.; Shetty, S.J.S.; Surabhi, S.; Shashidhar, A.P.; Karunakara, N.; Gurumurthy, S.C.; Sanjeev, G. Tuning the optical and electrical properties by gamma irradiation of silver nanoparticles decorated graphene oxide on glutaraldehyde crosslinked polyvinyl alcohol matrix. Mater. Res. Bull. 2024, 173, 112685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdani, A.; Dudani, N.; Takahama, S.; Bertrand, A.; Prévôt, A.S.H.; El Haddad, I.; Dillner, A.M. Fragment ion-functional group relationships in organic aerosols using aerosol mass spectrometry and mid-infrared spectroscopy. Atmos. Meas. Tech. Discuss. 2021, 15, 2857–2874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heydari, H.; Salehian, S.; Amiri, S.; Soltanieh, M.; Musavi, S.A. UV-cured polyvinyl alcohol-MXene mixed matrix membranes for enhancing pervaporation performance in dehydration of ethanol. Polym. Test. 2023, 123, 108046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogawa, S.; Tsuda, Y.; Sakamoto, T.; Okigawa, Y.; Masuzawa, T.; Yoshigoe, A.; Abukawa, T.; Yamada, T. Evaluation of doped potassium concentrations in stacked Two-Layer graphene using Real-time XPS. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2022, 605, 154748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, X.; Gao, Q.; Bu, S.; Xu, Z.; Shen, D.; Liu, B.; Lee, C.-S.; Zhang, W. Plasma-assisted synthesis of nickel-cobalt nitride–oxide hybrids for high-efficiency electrochemical hydrogen evolution. Mater. Today Energy 2021, 21, 100784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assender, H.E.; Windle, A.H. Crystallinity in poly (vinyl alcohol)2. Computer modelling of crystal structure over a range of tacticities. Polymer 1998, 39, 4303–4312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosas, J.; Virya, A.; Lian, K. Roles of hydrogen bonds in ionic conductivity in the LiNO3–poly (vinyl alcohol) electrolyte: A real-time Raman Spectroscopic Study. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2024, 128, 1139–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Liu, G. Concurrently Improving both Mechanical and Electrochemical Performances of Quasi-Solid-State Electrical Double-Layer Capacitors by a Rational Design of Gel Polymer Electrolytes. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 16, 56997–57003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathis, T.S.; Kurra, N.; Wang, X.; Pinto, D.; Simon, P.; Gogotsi, Y. Energy storage data reporting in perspective—Guidelines for interpreting the performance of electrochemical energy storage systems. Adv. Energy Mater. 2019, 9, 1902007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.