Abstract

Species of Pseudoplagiostomataceae were mainly introduced as endophytes, plant pathogens, or saprobes from various hosts. Based on multi-locus phylogenies from the internal transcribed spacers (ITS), the large subunit of nuclear ribosomal RNA gene (LSU), partial DNA-directed RNA polymerase II subunit two gene (rpb2), the partial translation elongation factor 1-alpha gene (tef1α), and the partial beta-tubulin gene (tub2), in conjunction with morphological characteristics, we describe three new species, viz. Pseudoplagiostoma alsophilae sp. nov., P. bambusae sp. nov., and P. machili sp. nov. Molecular clock analyses on the divergence times of Pseudoplagiostomataceae indicated that the conjoint ancestor of Pseudoplagiostomataceae and Apoharknessiaceae occurred in the Cretaceous period. and had a mean stem age of 104.1 Mya (95% HPD of 86.0–129.0 Mya, 1.0 PP), and most species emerged in the Paleogene and Neogene period. Historical biogeography was reconstructed for Pseudoplagiostomataceae by the RASP software with a S–DEC model, and suggested that Asia, specifically Southeast Asia, was probably the ancestral area.

1. Introduction

Pseudoplagiostomataceae Cheew., M.J. Wingf. and Crous, a monotypic family, was introduced by Cheewangkoon, M.J. Wingf. and Crous, and Pseudoplagiostoma Cheew., M.J. Wingf. and Crous (type species: Pseudoplagiostoma eucalypti Cheew., M.J. Wingf., and Crous) was designated as the type of genus [1]. At present, Pseudoplagiostoma comprises ten species including P. castaneae T.C. Mu, J.W. Xia, and X.G. Zhang, P. corymbiae Crous and Summerell, P. corymbiicola Crous, P. dipterocarpi Suwannarach, and Lumyong, P. dipterocarpicola X. Tang, R.S. Jayawardena, P. eucalypti, P. mangiferae Dayarathne, Phookamsak, and K.D. Hyde, P. myracrodruonis A.P.S.L. Pádua, T.G.L. Oliveira, Souza-Motta, and J.D.P. Bezerra, P. oldii Cheew., M.J. Wingf. and Crous, and P. variabile Cheew., M.J. Wingf. and Crous in the Index Fungorum (accession date: 6 December 2022). The family was introduced in both asexual and sexual morphs. The sexual morph is characterized by immersed, beaked, ostiole ascomata, unitunicate asci, a non-amyloid subapical ring, hyaline ascospores that are 1-septate near the middle or aseptate, with terminal, elongated hyaline appendages. The asexual morph is characterized by superficial and immersed conidiomata with masses of apically proliferous conidiogenous cells and hyaline, ellipsoidal conidia, but with no conidiophores [1,2,3].

Pseudoplagiostoma species were mainly reported as endophytes, plant pathogens, or saprobes in various regions, viz. Asia, North America, Oceania, and South America [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9]. As a type species, P. eucalypti was reported with more than 40 strains in the whole world (NCBI Nucleotide database, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nucleotide/, accessed on 6 December 2022). More than half of the P. eucalypti strains were distributed in Asia, including China, Malaysia, Thailand, and Viet Nam. Pseudoplagiostoma eucalypti, P. oldii and P. variabile possessed host preferences, and they almost occurred on Eucalyptus [1,10]. Recently, Pseudoplagiostoma as an endophyte from Castanea mollissima and Dipterocarpus sp. was introduced by Mu et al. [2] and Tang et al. [9]. This was the first time that Pseudoplagiostoma species had been found on the host of Castanea and Dipterocarpus.

The classifications were initially based on phenotype, and with the development of molecular technology, phylogenetic analysis of multi-gene provided reliable evidence for the classifications of phenotype [11,12,13]. However, this has led to significant changes in many lineages, and many unsuitable introductions of secondary ranking. Recently, Hyde et al. [13] used ‘temporal banding’ to revalued the position of higher taxa in the Ascomycota Caval.-Sm. They believed that the taxa of higher hierarchical levels should be older than lower levels. Thus, ‘temporal banding’ was regarded as a novel approach, using molecular clock analyses to standardize taxonomic ranking [11,13,14,15,16,17]. The concept of molecular clock studies is evaluating divergence times of lineages based on the assumption that mutations occur at balanced rate over time, and gradually become a reliable tool to calculate evolutionary events and explore new insights into genetic evolution [18,19,20]. Moreover, Hyde et al. [13] proposed a series of evolutionary periods including, families: 50–150 Mya, orders: 150–250 Mya, subclasses: 250–300 Mya, classes: 300–400 Mya, subphyla: 400–550 Mya, phyla > 550 Mya, and provided recommendations for ranking taxa with evidence for divergence times. The key to draw conclusions from divergence data was stabilize the phylogenetic trees.

In this article, three new species were described by combining phylogeny and morphology, viz. Pseudoplagiostoma alsophilae sp. nov., P. bambusae sp. nov., and P. machili sp. nov. At the same time, a hypothesis for specific divergence time and origin of Pseudoplagiostomataceae was proposed.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Isolation and Morphology

Diseased leaves of Alsophila spinulosa (Wall. ex Hook.) R. M. Tryon, Bambusoideae sp., Machilus nanmu (Oliver) Hemsley were collected from Fujian and Hainan Province during 2021 and 2022 in China. The cultures of Pseudoplagiostomataceae were isolated from diseased and non-diseased tissues of sample leaves using tissue isolation methods [21]. The diseased leaves with obvious disease spots were selected as experimental materials, and the surfaces of the materials were cleaned with sterile deionized water. The leaf samples with typical spot symptoms were first surface sterilized for 30 s in 75% ethanol, then rinsed in sterile deionized water for 45 s, in 2.5% sodium hypochlorite solution for 2 min, then rinsed four times in sterile deionized water for 45 s [22]. The pieces were blotted on sterile filter paper to dry, then transferred onto the PDA flats (PDA medium: potato 200 g, agar 15–20 g, dextrose 15–20 g, deionized water 1 L, pH ~7.0, available after sterilization), and incubated at 23 °C for 3–5 days. Hyphal tips were then removed to new PDA flats to gain pure cultures Simultaneously, inoculate on Petri dishes containing pine needle agar (PNA) [23], and incubated at 23 °C under continuous near ultraviolet light to promote sporulation.

After 10–14 days of incubation, morphological characters should be recorded, including graphs of the colonies were taken at the 10th and 14th day using a digital camera (Canon G7X), morphological characters of conidiomata using a stereomicroscope (Olympus SZX10), and micromorphological structures were observed using a microscope (Olympus BX53). All cultures were deposited in 10% sterilized glycerin and sterile water at 4 °C for future studies. Micromorphological structural measurements were taken using the Digimizer software (https://www.digimizer.com/, accessed on 6 December 2022), with 25 measurements taken for each structure [22]. Voucher specimens were deposited in the Herbarium Mycologicum Academiae Sinicae, Institute of Microbiology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China (HMAS), and Herbarium of the Department of Plant Pathology, Shandong Agricultural University, Taian, China (HSAUP). Ex-holotype living cultures were deposited in the Shandong Agricultural University Culture Collection (SAUCC). Taxonomic information of the new taxa was submitted to MycoBank (http://www.mycobank.org, accessed on 6 December 2022).

2.2. DNA Extraction and Amplification

Genomic DNA was extracted from fungal mycelia grown on PDA, using a kit (OGPLF-400, GeneOnBio Corporation, Changchun, China) according to the manufacturer’s protocol [24]. Gene sequences were obtained from five loci including the internal transcribed spacer regions with the intervening 5.8S nrRNA gene (ITS), the partial large subunit nrRNA gene (LSU), the partial DNA-directed RNA polymerase II subunit two gene (rpb2), the partial translation elongation factor 1-alpha gene (tef1α), and the partial beta-tubulin gene (tub2) were amplified by the primer pairs and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) programs listed in Table 1. Amplification reactions were performed in a 20 μL reaction volume, which contained 10 μL 2 × Hieff Canace® Plus PCR Master Mix (With Dye) (Yeasen Biotechnology, Cat No. 10154ES03), 0.5 μL of each forward and reverse primer (10 μM) (TsingKe, Qingdao, China), and 1 μL template genomic DNA, adjusted with distilled deionized water to a total volume of 20 μL. PCR amplification products were visualized on 2% agarose electrophoresis gel. DNA Sequencing was performed using an Eppendorf Master Thermocycler (Hamburg, Germany) at the Tsingke Company Limited (Qingdao, China) bi-directionally. Consensus sequences were obtained using MEGA 7.0 [25]. All sequences generated in this study were deposited in GenBank (Table 2).

Table 1.

Molecular markers and their PCR primers and programs used in this study.

Table 2.

Information of specimens used in this study.

2.3. Phylogenetic Analyses

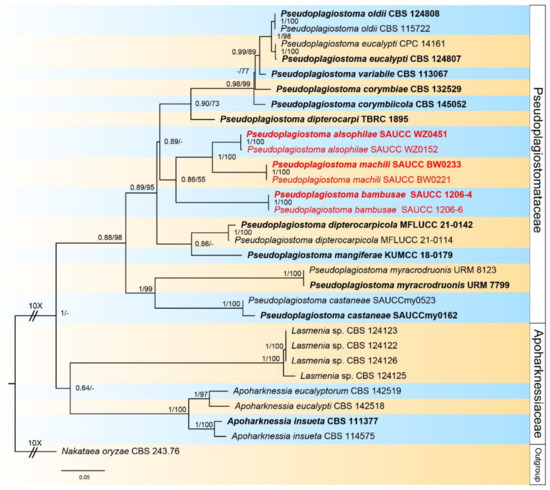

Novel sequences obtained in this study and related sets of sequences from Mu et al. [2] were aligned with MAFFT v. 7 and corrected manually using MEGA 7 [33]. Multi-locus phylogenetic analyses were based on the algorithms maximum likelihood (ML) and Bayesian inference (BI) methods. The ML was run on the CIPRES Science Gateway portal (https://www.phylo.org, accessed on 6 December 2022) [34] using RaxML–HPC2 on XSEDE v. 8.2.12 [35] and employed a GTRGAMMA substitution model with 1000 bootstrap replicates. Other parameters were default. For Bayesian inference analyses, the best model of evolution for each partition was determined using Modeltest v. 2.3 [36] and included the analyses. The BI was performed in MrBayes on XSEDE v. 3.2.7a [37,38,39], and two Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) chains were run, starting from random trees, for 2,000,000 generations. Additionally, sampling frequency of 100th generation. The first 25% of trees were discarded as burn-in, and BI posterior probabilities (PP) were conducted from the remaining trees. The consensus trees were optimized using FigTree v. 1.4.4 (http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree, accessed on 6 December 2022), and embellished with Adobe Illustrator CC 2019 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

A phylogram of the Pseudoplagiostomataceae and Apoharknessiaceae, based on a concatenated ITS, LSU, rpb2, tef1α, and tub2 sequence alignment, with Nakataea oryzae (CBS 243.76) as outgroup. BI posterior probabilities and maximum likelihood bootstrap support values above 0.60 and 50% are shown at the first and second position, respectively. Ex-type cultures are marked in bold face. Strains obtained in the present study are in red. Some branches are shortened for layout purposes—these are indicated by two diagonal lines with the number of times. The scale bar at the left–bottom represents 0.05 substitutions per site.

2.4. Divergence Time Estimation

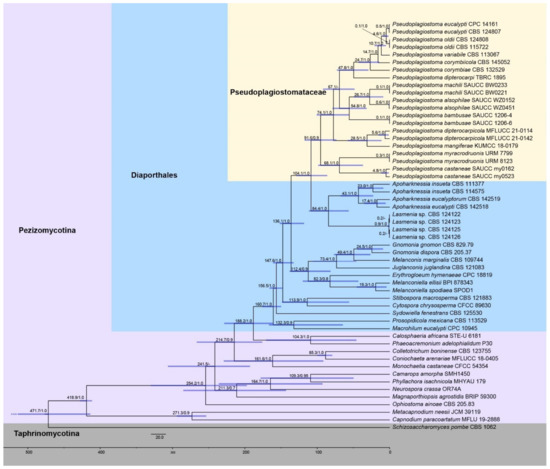

An ITS + LSU + rpb2 + tef1α + tub2 sequence dataset with 54 strains was used to infer the divergence times of species in the family Pseudoplagiostomataceae (Figure 2). An XML file was conduct with BEAUti v. 2 and run with BEAST v. 2.6.5. The rates of evolutionary changes at nuclear acids were estimated using MrModeltest v. 2.3 with the GTR substitution model [36,40]. Divergence time and corresponding CIs were taken with a Relaxed Clock Log Normal and the Yule speciation prior. Three fossil time points, i.e., Protocolletotrichum deccanense [41], Spataporthe taylorii [42], and Paleopyrenomycites devonicus [43,44], representing the divergence time at Capnodiales, Diaporthales, and Pezizomycotina were selected for calibration, respectively. The offset age with a gamma distributed prior (scale = 20 and shape = 1) was set as 65, 136, and 400 Mya for Colletotrichum, Diaporthales, and Pezizomycotina, respectively. After 100,000,000 generations, the first 20% were removed as burn in. Convergence of the log file was checked for with Tracer v. 1.7.2 (ESS > 200 was considered convergence). Afterwards, a maximum clade credibility (MCC) tree was integrated with TreeAnnotator v. 2.6.5, and annotating clades with posterior probability (PP) > 0.7.

Figure 2.

An estimated divergence of Pseudoplagiostomataceae generated from molecular clock analyses using a combined dataset of ITS, LSU, rpb2, tef1α, and tub2 sequences. Estimated mean divergence time (Mya) and posterior probabilities (PP) > 0.7 are annotated at the internodes. The 95% highest posterior density (HPD) interval of divergence time estimates is marked by horizontal blue bars.

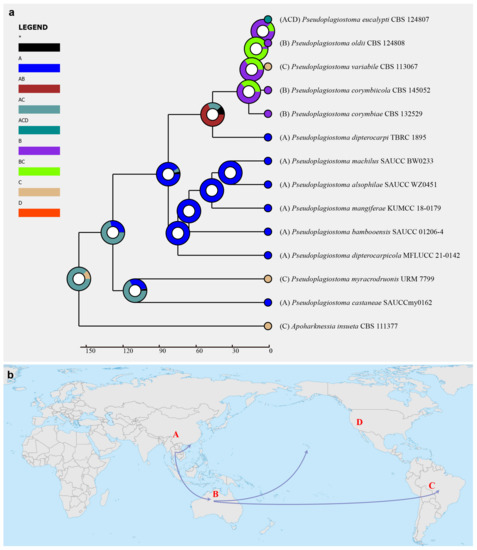

2.5. Inferring Historical Biogeography

The Reconstruct Ancestral State in Phylogenies (RASP) v. 4.2 was used to reconstruct historical biogeography for the family Pseudoplagiostomataceae [45,46]. Maximum clade credibility (MCC) tree, consensus tree, and states were checked with RASP before analysis. Based on the results, we select the Statistical Dispersal–Extinction–Cladogenesis (S–DEC) model. The geographic distributions for Pseudoplagiostomataceae were identified in four areas: (A) Asia, (B) Oceania, (C) South America, and (D) North America.

3. Results

3.1. Phylogenetic Analyses

Alignment contained 25 strains representing Pseudoplagiostomataceae and Apoharknessiaceae, and the strain CBS 243.76 of Nakataea oryzae was used as outgroup. The dataset had an aligned length of 3343 characters including gaps were obtained, viz. LSU: 1–842, ITS: 843–1544, rpb2: 1545–2215, tef1α: 2216–2813, tub2: 2814–3343 (Supplementary File S1). Of these, 2059 were constant, 303 were parsimony-uninformative, and 981 were parsimony-informative. The ModelTest suggested that the BI used the Dirichlet base frequencies, and the GTR + I + G evolutionary mode for LSU, ITS, and tub2, GTR + I for rpb2, and HKY + G for tef1α. The topology of the ML tree was consistent with that of the Bayesian tree, and, therefore, only shown the topology of the ML tree as a representative for recapitulating evolutionary relationship within the family Pseudoplagiostomataceae. The final ML optimization likelihood was −14,845.00184. The 25 strains were assigned to 18 species clades on the phylogram (Figure 1). Based on the phylogenetic resolution and morphological analyses, the present study introduced three novel species of the Pseudoplagiostomataceae, viz. Pseudoplagiostoma alsophilae sp. nov., P. bambusae sp. nov., and P. machili sp. nov.

3.2. Divergence Time Estimation for Pseudoplagiostomataceae

Divergence time estimation (Figure 2) showed that Pseudoplagiostomataceae occurred early with a mean stem age of 104.1 Mya [95% highest posterior density (HPD) of 86.0–129.0 Mya, 1.0 PP], and a mean crown age of 91.6 Mya (95% HPD of 73.4–117.6 Mya, 0.9 PP), which was consistent with a previous study [13]. The clade of Pseudoplagiostoma eucalypti and P. oldii with a mean stem age of 10.7 Mya (95% HPD of 4.9–20.9 Mya), and a mean crown age of 4.6 Mya (95% HPD of 1.5–9.7 Mya), which was consistent with previous studies [47]. While the clade of Pseudoplagiostoma eucalypti and P. oldii evolved most recently, the clade of P. myracrodruonis and P. castaneae diverged the earliest in the genus with a stem age of 68.1 Mya (95% HPD of 39.7–98.8 Mya). The stem/crown age of other species are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Inferred divergence time of species in the genus Pseudoplagiostoma.

3.3. The Historical Biogeography of Pseudoplagiostomataceae

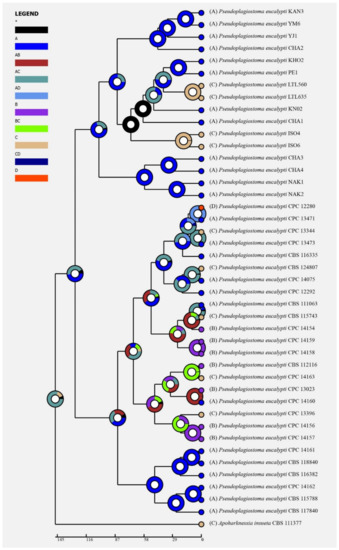

Historical biogeography scenarios of Pseudoplagiostomataceae were inferred by RASP (Figure 3). The RASP analysis indicated that Asia is the original center of Pseudoplagiostomataceae, and suggests that five dispersal events (one from Asia to Oceania, one from Oceania to Asia, two from Oceania to South America, and one from Oceania to North America) and four vicariance (Pseudoplagiostoma eucalypti, P. oldii, P. variabile, P. dipterocarpi and P. castaneae) events emerged during the distribution of this genus (Figure 3a). Meanwhile, eight species were found in Asia, three in Oceania, three in South America, and one in North America, indicating that Asia is still the center of Pseudoplagiostomataceae species. Afterwards, a total of 42 specimens of P. eucalypti (twenty-five in Asia, seven in Oceania, nine in North America and one in South America) have been collected, suggesting that Asia is the ancestral area (Figure 4). Meanwhile, possible concealed dispersal routes were indicated (Figure 3b): (1) Asia to Oceania, (2) Oceania to North America and (3) Oceania to South America.

Figure 3.

(a) Ancestral state reconstruction and divergence time estimation of Pseudoplagiostomataceae using a dataset containing ITS, LSU, rpb2, tef1α, and tub2 sequences. A pie chart at each node suggested the possible ancestral distributions deduced from Statistical Dispersal–Extinction–Cladogenesis (S–DEC) analysis completed in RASP. A black asterisk stands for other ancestral ranges. (b) Possible dispersal routes of Pseudoplagiostomataceae. Areas were marked as follows: (A) Asia, (B) Oceania, (C) South America, (D) North America, (A,B) Asia and Europe, (A,C) Asia and South America, (B,C) Oceania and South America, and (A,C,D) Asia, South America, and North America.

Figure 4.

Ancestral state reconstruction and divergence time estimation of Pseudoplagiostoma eucalypti using a dataset containing ITS, LSU, rpb2, tef1α, and tub2 sequences. A pie chart at each node indicates the possible ancestral distributions deduced from Statistical Dispersal–Extinction–Cladogenesis (S–DEC) analysis completed in RASP. A black asterisk stands for other ancestral ranges. Areas were marked as follows: (A) Asia, (B) Oceania, (C) South America, (D) North America, (A,B) Asia and Europe, (A,C) Asia and South America, (B,C) Oceania and South America, and (A,C,D) Asia, South America, and North America.

3.4. Taxonomy

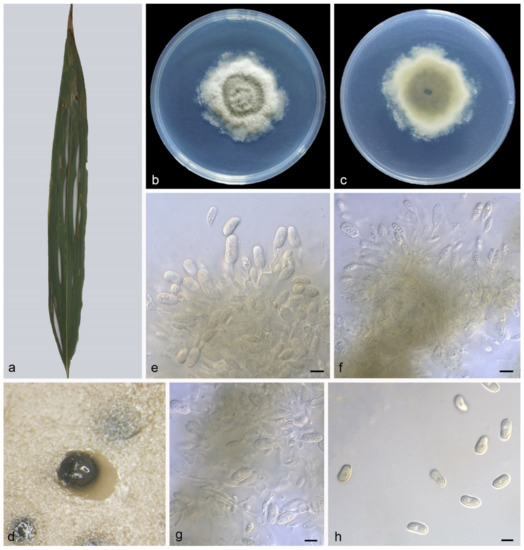

3.4.1. Pseudoplagiostoma alsophilae Z.X. Zhang, Z. Meng and X.G. Zhang, sp. nov.

MycoBank—No: MB846483

Etymology—The epithet “alsophilae” pertains to the generic name of the host plant Alsophila spinulosa.

Type—China. Hainan Province, Wuzhishan National Nature Reserve, on diseased leaves of Alsophila spinulosa, 20 May 2021, Z.X. Zhang, holotype HMAS 352298, ex-holotype living culture SAUCC WZ0451.

Description—Leaf is endogenic and associated with leaf spots. Sexual morph (PDA): Ascomata 300–450 × 300–400 μm, buried or attached to the surface of mycelia, aggregative or solitary, globose to elliptical, brown to black, exuding hyaline asci. Asci 60–110 × 12–19 μm, unitunicate, 8-spored, subcylindrical to long obovoid, wedge-shaped. Ascospores 19–24 × 8–10.5 μm, overlapping uni- to bi-seriate, lageniform, sharpening to apex, hyaline, median 1- septate. Asexual morph (PNA): Conidiomata pycnidial, growing on the surface of pine needles, globose to subglobose, 150–250 × 200–300 μm, solitary, black, exuding creamy yellow conidia. Conidiophores indistinct, often reduced to conidiogenous cells. Conidiogenous cells hyaline, smooth, multi-guttulate, cylindrical to ampulliform, attenuate towards apex, phialidic, 8–13 × 1.5–3 μm. Conidia aseptate, globose to irregular globose, broad ellipsoid, apex obtuse, base tapering, hyaline, smooth, guttulate, 17–21 × 13–15 μm (mean = 19.3 ± 1.2 × 14.2 ± 0.6 μm, n = 30), base with peg-like hila, 1.0–1.5 μm diam, see Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Pseudoplagiostoma alsophilae (holotype HMAS 352298). (a), leaves of host plant; (b,c), (left-above, right-reverse) after 15 days on PDA (b) and PNA (c); (d,g), colony overview; (e,f), asci and ascospores; (h,i), conidiogenous cells with conidia. Scale bars: (e,f,h,i), 10 μm.

Culture characteristics—Colonies on PDA flat at 23 °C for 14 days in dark reach 77–83 mm in diameter, grey-white to creamy white with irregular margin, spread like petals from the inside and outside, reverse is similar. Colonies on PNA flat at 23 °C for 14 days in dark reach 33–36 mm in diameter, white with regular margin, with slight aerial mycelia, reverse is similar.

Additional specimen examined—China. Hainan Province, Wuzhishan National Nature Reserve, on dead leaves of a broadleaf tree, 20 May 2021, Z.X. Zhang, HSAUP WZ0152, living culture SAUCC WZ0152.

Notes—Phylogenetic analyses of five combined genes (LSU, ITS, rpb2, tef1α and tub2) showed Pseudoplagiostoma alsophilae sp. Nov. formed an independent clade and was closely related to P. dipterocarpi, P. dipterocarpicola, and P. mangiferae (Figure 1). In detail, P. alsophilae is distinguished from P. dipterocarpi by 50/507 bp in ITS and 21/838 in LSU, from P. dipterocarpicola by 57/600 in ITS, 8/820 in LSU, 67/211 in tef1α and 96/481 in tub2, and from P. mangiferae by 64/573 in ITS and 10/778 in LSU. The morphological characteristics of P. alsophilae differing from P. dipterocarpi, P. dipterocarpicola, and P. mangiferae are listed in Table 4 [3,8,9].

Table 4.

Asexual morphological features of Pseudoplagiostoma species.

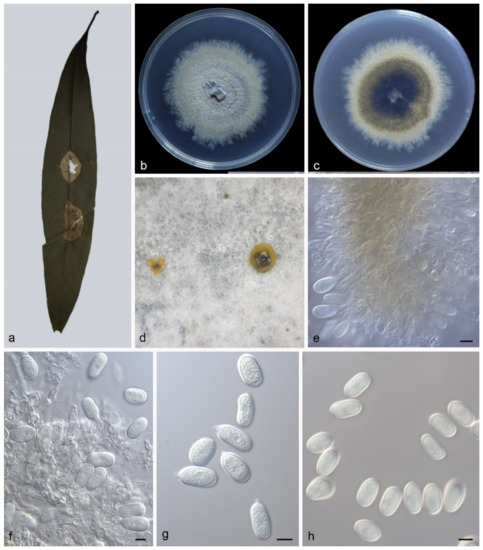

3.4.2. Pseudoplagiostoma bambusae Z.X. Zhang, Z. Meng, and X.G. Zhang, sp. nov.

MycoBank—No: MB846484

Etymology—The epithet “bambusae” pertains to the host plant Bambusoideae.

Type—China. Fujian Province, Fujian Wuyi Mountain National Nature Reserve, on diseased leaves of Bambusoideae sp., 15 October 2022, Z.X. Zhang, holotype HMAS 352300, ex-holotype living culture SAUCC 1206-4.

Description—Leaf is endogenic and associated with leaf spots. Conidiomata pycnidial, aggregated or solitary, globose to irregular, 200–250 × 150–250 μm, formed on agar surface, slimy, black, semi-submerged, exuding hyaline conidia. Conidiophores indistinct, often reduced to conidiogenous cells. Conidiogenous cells hyaline, smooth, cylindrical to ampulliform, attenuate towards apex, phialidic, 5–13 × 1.5–2.5 μm. Conidia aseptate, oblong to broad ellipsoid, base tapering, hyaline, smooth, guttulate, slightly depressed in the middle, 13–20 × 5.7–7.6 μm (mean = 15.2 ± 1.6 × 6.7 ± 0.5 μm, n = 30), base with inconspicuous to conspicuous hilum, 1.0–1.3 μm diam, see Figure 6. Sexual morph: unknown.

Figure 6.

Pseudoplagiostoma bambusae (holotype HMAS 352300). (a) leaves of host plant; (b,c) inverse and reverse sides of colony after 15 days on PDA; (d) colony overview; (e–g) conidiogenous cells with conidia; (h) conidia. Scale bars: (e–h), 10 μm.

Culture characteristics—Colonies on PDA flat at 23 °C for 14 days in dark reach 43–48 mm in diameter, bluish-green to grey-white, with moderate aerial mycelia and undulate margin, reverse is similar.

Additional specimen examined—China. Fujian Province, Fujian Wuyi Mountain National Nature Reserve, on diseased leaves of Bambusoideae sp., 15 October 2022, Z.X. Zhang, HSAUP 1206-6, living culture SAUCC 1206-6.

Notes—Phylogenetic analyses of five combined genes showed Pseudoplagiostoma bambusae sp. nov. formed an independent clade and was closely related to P. alsophilae and P. machili (Figure 1). In detail, P. bambusae is distinguished from P. alsophilae by 48/613 bp in ITS, 12/828 in LSU, 144/535 in tef1α and 53/477 in tub2, and from P. machili by 67/615 in ITS, 9/828 in LSU, 156/536 in tef1α and 71/485 in tub2. Morphologically, P. bambusae differs from P. alsophilae and P. machili in several characteristics, as shown in Table 4.

3.4.3. Pseudoplagiostoma machili Z.X. Zhang, Z. Meng, and X.G. Zhang, sp. nov.

MycoBank No: MB846485

Etymology—The epithet “machili” pertains to the generic name of the host plant Machilus nanmu.

Type—China. Hainan Province, Bawangling National Forest Park, on diseased leaves of Machilus nanmu, 19 May 2021, Z.X. Zhang, holotype HMAS 352299, ex-holotype living culture SAUCC BW0233.

Description—Leaf is endogenic and associated with leaf spots. Conidiomata pycnidial, aggregated or solitary, globose to irregular, 150–200 × 100–250 μm, black, exuding yellow conidia. Conidiophores indistinct, often reduced to conidiogenous cells. Conidiogenous cells hyaline, smooth, cylindrical to ampulliform, attenuate towards apex, phialidic, 7–16 × 2–3.5 μm. Conidia aseptate, ellipsoid to broad ellipsoid, apex obtuse, base tapering, hyaline, smooth, guttulate, 17.5–23 × 10.5–13.5 μm (mean = 20.7 ± 1.6 × 12.4 ± 0.7 μm, n = 30), base with inconspicuous to conspicuous hilum, 1.3–1.5 μm diam, see Figure 7. Sexual morph: unknown.

Figure 7.

Pseudoplagiostoma machili (holotype HMAS 352299). (a) leaves of host plant; (b,c) inverse and reverse sides of colony after 15 days on PDA; (d) colony overview; (e,f), Conidiogenous cells with conidia; (g,h) conidia. Scale bars: (e–h) 10 μm.

Culture characteristics—Colonies on PDA flat at 23 °C for 14 days in dark reach 58–62 mm in diameter, grey-white to creamy white, with moderate aerial mycelia and undulate margin, reverse is similar.

Additional specimen examined—China. Hainan Province, Bawangling National Forest Park, on diseased leaves of Machilus nanmu, 19 May 2021, Z.X. Zhang, HSAUP BW0221, living culture SAUCC BW0221.

Notes—Based on phylogeny and morphology, strains SAUCC BW0233 and SAUCC BW0221 were identified to the same species Pseudoplagiostoma machili sp. nov. For details, please refer to the notes for Pseudoplagiostoma bambusae.

4. Discussion

In the present study, three new species (Pseudoplagiostoma alsophilae, P. bambusae, and P. machili) from three hosts (Alsophila spinulosa, Bambusoideae sp., Machilus nanmu) in two provinces of China were illustrated and described (Figure 5, Figure 6 and Figure 7). P. alsophilae reproduced both asexually and sexually, while P. bambusae and P. machili only reproduced asexually. Most species of Pseudoplagiostomataceae were isolated from Eucalyptus (Myrtaceae) (Pseudoplagiostoma corymbiae, P. corymbiicola, P. eucalypti, P. oldii, and P. variabile), especially P. eucalypti with more than 40 strains [1,4,5,10]. Recently, other hosts were reported, including Anacardiaceae (P. mangiferae and P. myracrodruonis), Dipterocarpaceae (P. dipterocarpi and P. dipterocarpicola), Fagaceae (P. castaneae) [2,3,7,8,9]. This study puts more families in the host list, and they are Cyatheaceae (P. alsophilae), Gramineae (P. bambusae), and Lauraceae (P. machili). It has significant research value in regional species diversity and ecological diversity.

Currently, the divergence and ranking of taxa across the kingdom Fungi, especially the phylum Ascomycota, have significant theoretical and practical significance, and gradually become a reliable and referential evidence before introducing new higher taxa [11,13,14,15,16,17]. Our analysis of molecular clock indicates that Pseudoplagiostomataceae was closely related to Apoharknessiaceae, which was most deeply diverged during the Paleogene, with a mean stem age of 104.1 Mya (95% HPD of 86.0–129.0 Mya), and full supports (1.0 PP, Figure 2 and Table 3). Even though Hyde et al. [13] only included two species of the Pseudoplagiostomataceae, its divergence time was coincided with this study. In the present study, a mean stem age of Diaporthales reached 188.2 Mya and was fully supported earlier than in the previous study [13,47]. Therefore, both new fossil findings and new species findings have an impact on the divergence time of the orders. Of course, the impact was controllable, and it must be in certain evolutionary periods.

Macrofungi have been widely applied for biogeographical analyses [24,48,49,50,51]. Our study suggested that the species distribution and speciation of Pseudoplagiostomataceae had a particular biogeographical pattern, and these species appeared to originate in Asia, particularly in Southeast Asia. Previous studies suggested that the Indian continent collided with the Eurasian continent at ~60 Mya, which was consistent with some speciation of the Pseudoplagiostomataceae, and formed the Hengduan–Himalayan area which was a global biodiversity hotspot [52,53,54,55,56,57]. Based on the discovered specimens and biogeographical information, this study is more inclined to explain that Pseudoplagiostomataceae species originated in Asia and spread to Hawaii and South America through Malaysia, Australia, New Zealand, and more than 20,000 independent islands in the South Pacific, and frequent hurricanes and circulating ocean currents in the South Pacific are the best spore carriers. The humid climate in the southern hemisphere and the rich tropical host plants, such as Quercus sp. and Eucalyptus sp., are also suitable for the reproduction and evolution of Pseudoplagiostomataceae species [58,59]. Dispersal, vicariance, and extinction of species may be related to the Indian continent collided with the Eurasian; however, this claim needs more species and fossil evidence to support it.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/jof9010082/s1, Supplementary File S1: The combined ITS, LSU, rpb2, tef1α, and tub2 sequences.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, software, Z.Z.; validation, formal analysis, X.L. (Xinye Liu); investigation, resources, M.T.; data curation, writing—original draft preparation, Z.Z.; writing—review and editing, visualization, X.L. (Xiaoyong Liu) and J.X.; supervision, Z.M.; project administration, X.Z.; funding acquisition, X.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China (nos. 31750001, 31900014, and U2002203).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable for studies involving humans or animals.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The sequences from the present study were submitted to the NCBI database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/, accessed on 6 December 2022) and the accession numbers were listed in Table 2.

Acknowledgments

We thank Heng Zhao (Institute of Microbiology, Beijing Forestry University) for some guidance and technical support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Cheewangkoon, R.; Groenewald, J.Z.; Verkley, G.J.M.; Hyde, K.D.; Wingfield, M.J.; Gryzenhout, M.; Summerell, B.A.; Denman, S.; Toanun, C.; Crous, P.W. Re-evaluation of Cryptosporiopsis eucalypti and Cryptosporiopsis-like species occurring on Eucalyptus leaves. Fungal Divers. 2010, 44, 89–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, T.C.; Zhang, Z.X.; Liu, R.Y.; Li, Z.; Zhang, X.G.; Xia, J.W. Morphological and molecular identification of Pseudoplagiostoma castaneae sp. nov. (Pseudoplagiostomataceae, Diaporthales) in Shandong Province, China. Nova Hedwig. 2022, 114, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suwannarach, N.; Kumla, J.; Lumyong, S. Pseudoplagiostoma dipterocarpi sp. nov., a new endophytic fungus from Thailand. Mycoscience 2016, 57, 118–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crous, P.W.; Summerell, B.A.; Shivas, R.G.; Burgess, T.I.; Decock, C.A.; Dreyer, L.L.; Granke, L.L.; Guest, D.I.; Hardy, G.E.; Hausbecket, M.K.; et al. Fungal Planet description sheets: 107–127. Persoonia 2012, 28, 138–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crous, P.W.; Luangsa-Ard, J.J.; Wingfield, M.J.; Carnegie, A.J.; Hernandez-Restrepo, M.; Lombard, L.; Roux, J.; Barreto, R.W.; Baseia, I.G.; Cano-Lira, J.F.; et al. Fungal Planet description sheets: 785–867. Persoonia 2018, 41, 238–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crous, P.W.; Wingfield, M.J.; Cheewangkoon, R.; Carnegie, A.J.; Burgess, T.I.; Summerell, B.A.; Edwards, J.; Taylor, P.W.J.; Groenewald, J.Z. Foliar pathogens of eucalypts. Stud. Mycol. 2019, 94, 125–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezerra, J.D.P.; Pádua, A.P.S.L.; Oliveira, T.G.L.; Paiva, L.M.; Guarnaccia, V.; Fan, X.L.; Souza-Motta, C.M. Pseudoplagiostoma myracrodruonis (Pseudoplagiostomataceae, Diaporthales): A new endophytic species from Brazil. Mycol. Prog. 2019, 18, 1329–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phookamsak, R.; Hyde, K.D.; Jeewon, R.; Bhat, D.J.; Jones, E.B.G.; Maharachchikumbura, S.S.N.; Raspé, O.; Karunarathna, S.C.; Wanasinghe, D.N.; Hongsanan, S.; et al. Fungal diversity notes 929–1035: Taxonomic and phylogenetic contributions on genera and species of fungi. Fungal Divers. 2019, 95, 1–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Jayawardena, R.S.; Stephenson, S.L.; Kang, J.C. A new species Pseudoplagiostoma dipterocarpicola (Pseudoplagiostomataceae, Diaporthales) found in northern Thailand on members of the Dipterocarpaceae. Phytotaxa 2022, 543, 233–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.L.; Yang, S.W.; Chiang, C.Y. The First Report of Leaf Spot of Eucalyptus robusta Caused by Pseudoplagiostoma eucalypti in Taiwan. Plant Dis. 2016, 100, 1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.G.; Ariyawansa, H.A.; Hyde, K.D.; Maharachchikumbura, S.S.N.; Zhao, R.L.; Phillips, A.J.L.; Jayawardena, R.S.; Thambugala, K.M.; Dissanayake, A.J.; Wijayawardene, N.N.; et al. Perspectives into the value of genera, families and orders in classification. Mycosphere 2016, 7, 1649–1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.L.; Zhou, J.L.; Chen, J.; Margaritescu, S.; Sánchez-Ramírez, S.; Hyde, K.D.; Callac, P.; Parra, L.A.; Li, G.-J.; Moncalvo, J.-M. Towards standardizing taxonomic ranks using divergence times—A case study for reconstruction of the Agaricus taxonomic system. Fungal Divers. 2016, 78, 239–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyde, K.D.; Maharachchikumbura, S.S.N.; Hongsanan, S.; Samarakoon, M.C.; Lücking, R.; Pem, D.; Harishchandra, D.; Jeewon, R.; Zhao, R.-L.; Xu, J.-C.; et al. The ranking of fungi: A tribute to David L. Hawksworth on his 70th birthday. Fungal Divers. 2017, 84, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beimforde, C.; Feldberg, K.; Nylinder, S.; Rikkinen, J.; Tuovila, H.; Dorfelt, H.; Gube, M.; Jackson, D.J.; Reitner, J.; Seyfullah, L.J.; et al. Estimating the Phanerozoic history of the Ascomycota lineages: Combining fossil and molecular data. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2014, 78, 386–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hongsanan, S.; Sánchez-Ramírez, S.; Crous, P.W.; Ariyawansa, H.A.; Zhao, R.L.; Hyde, K.D. The evolution of fungal epiphytes. Mycosphere 2016, 7, 1690–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samarakoon, M.C.; Hyde, K.D.; Promputtha, I.; Ariyawansa, H.A.; Hongsanan, S. Divergence and ranking of taxa across the kingdoms Animalia, Fungi and Plantae. Mycosphere 2016, 7, 1678–1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Divakar, P.K.; Crespo, A.; Kraichak, E.; Leavitt, S.D.; Singh, G.; Schmitt, I.; Lumbsch, H.T. Using a temporal phylogenetic method to harmonize family- and genus-level classification in the largest clade of lichen-forming fungi. Fungal Divers. 2017, 84, 101–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bromham, L.; Penny, D. The modern molecular clock. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2003, 4, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S. Molecular clocks: Four decades of evolution. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2005, 6, 654–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijaykrishna, D.; Jeewon, R.; Hyde, K.D. Molecular taxonomy, origins and evolution of freshwater ascomycetes. Fungal Divers. 2006, 23, 351–390. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, N.; Voglmayr, H.; Ma, C.Y.; Xue, H.; Piao, C.G.; Li, Y. A new Arthrinium-like genus of Amphisphaeriales in China. MycoKeys 2022, 92, 27–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, N.; Voglmayr, H.; Xue, H.; Piao, C.G.; Li, Y. Morphology and Phylogeny of Pestalotiopsis (Sporocadaceae, Amphisphaeriales) from Fagaceae Leaves in China. Microbiol. Spectr. 2022, 10, e03272-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, U.; Nakashima, C.; Crous, P.W.; Groenewald, J.Z.; Moreno-Rico, O.; Rooney-Latham, S.; Blomquist, C.L.; Haas, J.; Marmolejo, J. Phylogeny and taxonomy of the genus Tubakia s. lat. Fungal Syst. Evol. 2018, 1, 41–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, H.; Zhou, M.; Liu, X.Y.; Wu, F.; Dai, Y.C. Phylogeny, Divergence Time Estimation and Biogeography of the Genus Onnia (Basidiomycota, Hymenochaetaceae). Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 907961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Tamura, K. MEGA7: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2016, 33, 1870–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, T.J.; Bruns, T.; Lee, S.; Taylor, F.J.R.M.; Lee, S.H.; Taylor, L.; Shawe-Taylor, J. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal rna genes for phylogenetics. In PCR Protocols: A Guide to Methods and Applications; Innis, M.A., Gelfand, D.H., Sninsky, J.J., Eds.; Academic Press Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1990; pp. 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehner, S.A.; Samuels, G.J. Taxonomy and phylogeny of Gliocladium analysed from nuclear large subunit ribosomal DNA sequences. Mycol. Res. 1994, 98, 625–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilgalys, R.; Hester, M. Rapid genetic identification and mapping of enzymatically amplified ribosomal DNA from several Cryptococcus species. J. Bacteriol. 1990, 172, 4238–4246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.J.; Whelen, S.; Hall, B.D. Phylogenetic Relationships among Ascomycetes: Evidence from an RNA polymerse II subunit. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1999, 16, 1799–1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donnell, K.; Kistler, H.C.; Cigelnik, E.; Ploetz, R.C. Multiple Evolutionary Origins of the Fungus Causing Panama Disease of Banana: Concordant Evidence from Nuclear and Mitochondrial Gene Genealogies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1998, 95, 2044–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbone, I.; Kohn, L.M. A method for designing primer sets for speciation studies in filamentous ascomycetes. Mycologia 1999, 91, 553–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glass, N.L.; Donaldson, G.C. Development of primer sets designed for use with the PCR to amplify conserved genes from filamentous ascomycetes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1995, 61, 1323–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katoh, K.; Rozewicki, J.; Yamada, K.D. MAFFT online service: Multiple sequence alignment, interactive sequence choice and visualization. Brief. Bioinform. 2019, 20, 1160–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, M.A.; Pfeiffer, W.; Schwartz, T. The CIPRES science gateway: Enabling high-impact science for phylogenetics researchers with limited resources. In Proceedings of the 1st Conference of the Extreme Science and Engineering Discovery Environment. Bridging from the Extreme to the Campus and Beyond, Chicago, IL, USA, 16 July 2012; p. 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamatakis, A. RAxML Version 8: A tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 1312–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nylander, J.A.A. MrModelTest v. 2. Program distributed by the author. In Evolutionary Biology Centre; Uppsala University: Uppsala, Sweden, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Huelsenbeck, J.P.; Ronquist, F. MRBAYES: Bayesian inference of phylogeny. Bioinformatics 2001, 17, 754–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ronquist, F.; Huelsenbeck, J.P. MrBayes 3: Bayesian Phylogenetic Inference under Mixed Models. Bioinformatics 2003, 19, 1572–1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronquist, F.; Teslenko, M.; van der Mark, P.; Ayres, D.L.; Darling, A.; Höhna, S.; Larget, B.; Liu, L.; Suchard, M.A.; Huelsenbeck, J.P. MrBayes 3.2: Efficient Bayesian phylogenetic inference and model choice across a large model space. Syst. Biol. 2012, 61, 539–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posada, D.; Crandall, K.A. Modeltest: Testing the model of DNA substitution. Bioinformatics 1998, 14, 817–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kar, R.K.; Sharma, N.; Verma, U.K. Plant pathogen Protocolletotrichum from a Deccan intertrappean bed (Maastrichtian), India. Cretac. Res. 2004, 25, 945–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronson, A.W.; Klymiuk, A.A.; Stockey, R.A.; Tomescu, A.M.F. A perithecial Sordariomycete (Ascomycota, Diaporthales) from the Lower Cretaceous of Vancouver Island, British Columbia, Canada. Int. J. Plant Sci. 2013, 174, 278–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, T.N.; Hass, H.; Kerp, H. The oldest fossil ascomycetes. Nature 1999, 399, 648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, T.N.; Hass, H.; Kerp, H.; Krings, M.; Hanlin, R.T. Perithecial ascomycetes from the 400 million year old Rhynie chert: An example of ancestral polymorphism. Mycologia 2005, 97, 269–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Y.; Blair, C.; He, X. RASP 4: Ancestral state reconstruction tool for multiple genes and characters. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2020, 37, 604–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Y.; Harris, A.J.; Blair, C.; He, X. RASP (Reconstruct Ancestral State in Phylogenies): A tool for historical biogeography. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2015, 87, 46–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guterres, D.C.; Galvao-Elias, S.; de Souza, B.C.P.; Pinho, D.B.; Dos Santos, M.; Miller, R.N.G.; Dianese, J.C. Taxonomy, phylogeny, and divergence time estimation for Apiosphaeria guaranitica, a Neotropical parasite on bignoniaceous hosts. Mycologia 2018, 110, 526–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hibbett, D.S.; Hansen, K.; Donoghue, M.J. Phylogeny and biogeography of Lentinula inferred from an expanded rDNA dataset. Mycol. Res. 1998, 102, 1041–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Chen, J.J.; Cui, B.K.; Zhou, L.W.; Korhonen, K.; Dai, Y.C. Phylogeny, divergence time estimation, and biogeography of the genus Heterobasidion (Basidiomycota, Russulales). Fungal Divers. 2015, 71, 185–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Ramírez, S.; Tulloss, R.E.; Amalfi, M.; Moncalvo, J.M. Palaeotropical origins, boreotropical distribution and increased rates of diversification in a clade of edible ectomycorrhizal mushrooms (Amanita section Caesareae). J. Biogeogr. 2015, 42, 351–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, C.; Sánchez-Ramírez, S.; Kuhar, F.; Kaplan, Z.; Smith, M.E. The Gondwanan connection—Southern temperate Amanita lineages and the description of the first sequestrate species from the Americas. Fungal Biol. 2017, 121, 638–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.S.; Zhao, X.X.; Liu, Z.F.; Lippert, P.C.; Graham, S.A.; Coe, R.S.; Yi, H.S.; Zhu, L.D.; Liu, S.; Li, Y.L. Constraints on the early uplift history of the Tibetan Plateau. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 4987–4992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copley, A.; Avouac, J.P.; Royer, J.Y. India-Asia collision and the Cenozoic slowdown of the Indian plate: Implications for the forces driving plate motions. J. Geophys. Res. 2010, 115, B03410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, L.; Maksatbek, S.; Cai, F.L.; Wang, H.Q.; Song, P.P.; Ji, W.Q.; Xu, Q.; Zhang, L.Y.; Muhammad, Q.; Upendra, B. Processes of initial collision and suturing between India and Asia. Sci. China Earth Sci. 2017, 60, 635–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najman, Y.; Jenks, D.; Godin, L.; Boudagher-Fadel, M.; Millar, I.; Garzanti, E.; Horstwood, M.; Bracciali, L. The Tethyan Himalayan detrital record shows that India-Asia terminal collision occurred by 54 Ma in the Western Himalaya. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2017, 459, 301–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.F.; Wu, F.Y. The timing of continental collision between India and Asia. Sci. Bull. 2018, 63, 1649–1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Zhang, L.; Liao, R.; Sun, S.; Li, C.; Liu, H. Plate convergence in the Indo-Pacific region. J. Oceanol. Limnol. 2020, 38, 1008–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopper, S.D.; Gioia, P. The Southwest Australian Floristic Region: Evolution and Conservation of a Global Hot Spot of Biodiversity. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2004, 35, 623–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swee–Hock, S. The Population of Malaysia; Institute of Southeast Asian Studies: Pasir Panjang, Singapore, 2007. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).