Abstract

Three new species of Clonostachys are introduced based on specimens collected from China. Clonostachys chongqingensis sp. nov. is distinguished by pale yellow to pale orange-yellow perithecia with a very low papilla, clavate to subcylindrical asci possessing ellipsoidal to elongate-ellipsoidal spinulose ascospores 13–16 × 4.5–5.5 μm; it has acremonium- to verticillium-like conidiophores and ellipsoidal to rod-shaped conidia. Clonostachys leptoderma sp. nov. has pinkish-white subglobose to globose perithecia on a well-developed stroma and with a thin perithecial wall, clavate to subcylindrical asci with ellipsoidal to elongate-ellipsoidal spinulose ascospores 7.5–11 × 2.5–3.5 μm; it produces verticillium-like conidiophores and ellipsoidal to subellipsoidal conidia. Clonostachys oligospora sp. nov. features solitary to gregarious perithecia with a papilla, clavate asci containing 6–8 smooth-walled ascospores 9–17 × 3–5.5 μm; it forms verticillium-like conidiophores and sparse, subfusiform conidia. The morphological characteristics and phylogenetic analyses of combined nuclear ribosomal DNA ITS1-5.8S-ITS2 and beta-tubulin sequences support their placement in Clonostachys and their classification as new to science. Distinctions between the novel taxa and their close relatives are compared herein.

1. Introduction

Clonostachys Corda, typified by C. araucaria Corda, is characterized by solitary to gregarious, subglobose or globose to ovoid perithecia that are white, yellow, pale orange, tan, or brown; perithecial walls are KOH− and LA−; there are narrowly clavate to clavate asci containing eight ascospores; it produces penicillium-, verticillium-, gliocladium-, or acremonium-like conidiophores, cylindrical to narrowly flask-shaped phialides, and ellipsoidal to subfusiform conidia [1]. Members of the genus usually have a broad range of lifestyles and occur on the bark of recently dead trees, decaying leaves, and less frequently on other fungi, nematodes, and insects [1,2,3]. They are economically important in the fields of pharmaceutics and agriculture [4]. For instance, the secondary metabolites produced by C. byssicola Schroers exhibited antibacterial activities [5], and strains of C. rosea (Link) Schroers, Samuels, Seifert & W. Gams have been widely used as biocontrol agents [6].

About 100 names have been created under the genus Clonostachys (www.indexfungorum.org (accessed on 1 July 2022)), among which 65 species are commonly accepted [2,3,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20]. Twenty-four species are known from China [2,7,21]. In this study, three additional taxa are introduced based on morphological characteristics and sequence analyses of combined nuclear ribosomal DNA ITS1-5.8S-ITS2 (ITS) and beta-tubulin (BenA) regions. Comparisons between these novel species and their close relatives are performed.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sampling and Morphological Studies

Specimens were collected from Chongqing and Yunnan Province and were deposited in the Herbarium Mycologicum Academiae Sinicae (HMAS). Cultures were obtained by single ascospore isolation from fresh perithecium and are preserved in the State Key Laboratory of Mycology, Institute of Microbiology, Chinese Academy of Sciences. The methods of Hirooka et al. [22] were generally followed for morphological observations. Perithecial wall reactions were tested in 3% potassium hydroxide (KOH) and 100% lactic acid (LA). Longitudinal sections through the perithecia were made with a freezing microtome (YD-1508-III, Jinhua, China) at a thickness of 6–8 μm. Photographs were taken using a Canon G5 digital camera (Tokyo, Japan) connected to a Zeiss Axioskop 2 plus microscope (Göttingen, Germany). For colony characteristics and growth rates, strains were grown on potato dextrose agar (PDA) (200 g potato + 2% (w/v) dextrose + 2% (w/v) agar) and synthetic low-nutrient agar (SNA) [23] in 90 mm plastic Petri dishes at 25 °C for 2 weeks with alternating periods of light and darkness (12 h/12 h).

2.2. DNA Extraction, PCR Amplification, and Sequencing

The genomic DNA was extracted from fresh mycelium following the method of Wang and Zhuang [24]. Five primer pairs, namely ITS5/ITS4 [25], T1/T22 [26], acl1-230up/acl1-1220low [27], Crpb1a/rpb1c [28], and EF1-728F/EF2 [29,30], were used to amplify the sequences of ITS, BenA, ATP citrate lyase (ACL1), the largest subunit of RNA polymerase II (RPB1), and translation elongation factor 1-α (TEF1), respectively. PCR reactions were performed on an ABI 2720 Thermal Cycler (Applied Biosciences, Foster City, CA, USA) with a 25 μL reaction system consisting of 12.5 μL Taq MasterMix, 1 μL of each primer (10 μM), 1 μL template DNA, and 9.5 μL ddH2O. DNA sequencing was carried out in both directions with the same primer pairs using an ABI 3730 XL DNA Sequencer (Applied Biosciences, Foster City, CA, USA). Newly achieved sequences and those retrieved from GenBank are listed in Table 1. Fusarium acutatum Nirenberg & O’Donnell and Nectria cinnabarina (Tode) Fr. were chosen as outgroup taxa.

Table 1.

Sequences used in this study.

2.3. Sequence Alignment and Phylogenetic Analyses

Sequences were assembled and aligned with BioEdit 7.0.5 [31] and converted to nexus files by ClustalX 1.8 [32]. To confirm the taxonomic positions of the new species, ITS and BenA sequences were combined and analyzed with Bayesian inference (BI), maximum likelihood (ML), and maximum parsimony (MP) methods. A partition homogeneity test (PHT) was performed with 1000 replicates in PAUP*4.0b10 [33] to evaluate the statistical congruence between the two loci. The BI analysis was conducted by MrBayes 3.1.2 [34] using a Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) algorithm. Nucleotide substitution models were determined by MrModeltest 2.3 [35]. Four Markov chains were run simultaneously for 1,000,000 generations with the trees sampled every 100 generations. A 50% majority rule consensus tree was computed after excluding the first 2500 trees as “burn-in”. Bayesian inference posterior probability (BIPP) was determined from the remaining trees. The ML analysis was performed via IQ-Tree 1.6.12 [36] using the best model for each locus, as chosen by ModelFinder [37]. The MP analysis was performed with PAUP 4.0b10 [33] using heuristic searches with 1000 replicates of random addition of sequences and subsequent TBR (tree bisection and reconnection) branch swapping. The topological confidence of the resulting trees and statistical support of the branches were tested in maximum parsimony bootstrap proportion (MPBP) with 1000 replications and each with 10 replicates of the random addition of taxa. Trees were examined by TreeView 1.6.6 [38]. The maximum likelihood bootstrap (MLBP) values, MPBP values greater than 70%, and BIPP values greater than 90% were shown at the nodes.

3. Results

3.1. Phylogeny

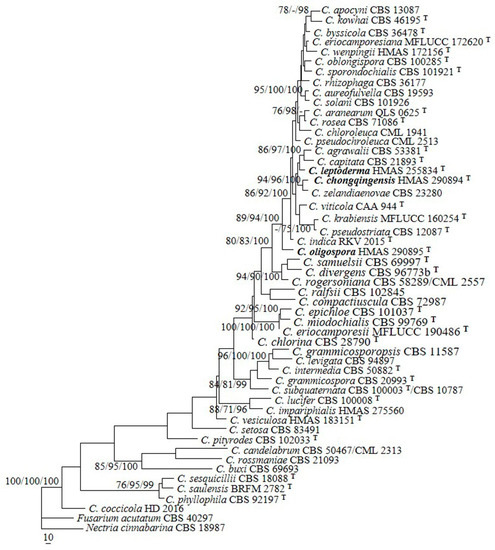

The sequences of ITS and BenA from 50 representative species of Clonostachys were analyzed. The PHT (p = 0.05) indicated that the individual partitions were not highly incongruent [39]; thus, the two loci were combined for phylogenetic analyses. In the MP analysis, the datasets included 1159 nucleotide characters, of which 543 bp were constant, 154 were variable and parsimony-uninformative, and 462 were parsimony-informative. The MP analysis resulted in 123 most parsimonious trees (tree length = 2794, consistency index = 0.4098, homoplasy index = 0.5902, retention index = 0.4677, rescaled consistency index = 0.1917). One of the MP trees generated is shown in Figure 1. The topologies of the BI and ML trees were similar to that of the MP tree. The isolates 12581, 12672, and 11691 were grouped with the other Clonostachys taxa investigated (MPBP/MLBP/BIPP = 100%/100%/100%), which confirmed their taxonomic positions. The isolate 12581 was grouped with C. agrawalii (Kushwaha) Schroers and C. capitata Schroers, with low statistical support. The isolate 12672 clustered with C. zelandiaenovae Schroers (MPBP/MLBP/BIPP = 94%/96%/100%), and 11691 formed a separate lineage.

Figure 1.

A maximum parsimony tree generated from analyses of combined ITS and BenA sequences of Clonostachys species. The MP analysis was performed using heuristic searches with 1000 replicates. MPBP (left) and MLBP (middle) values greater than 70% and BIPP (right) values greater than 90% were shown at the nodes. Fusarium acutatum and Nectria cinnabarina were chosen as outgroup taxa.

3.2. Taxonomy

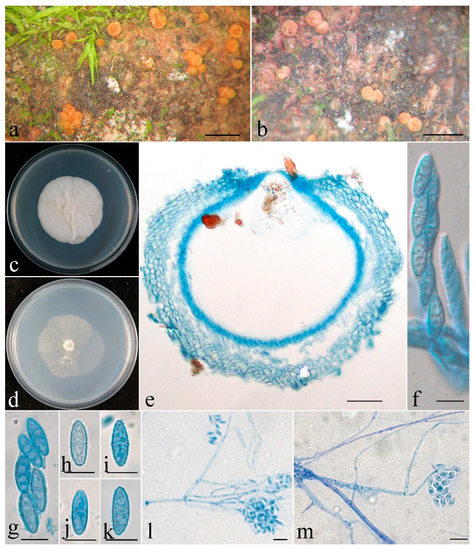

- Clonostachys chongqingensis Z.Q. Zeng and W.Y. Zhuang, sp. nov. (Figure 2).

Fungal Names: FN571276.

Etymology: The specific epithet refers to the type locality of the fungus.

Typification: China, Chongqing City, Jinfo Mountain, 29°2′50″ N 107°11′0″ E, on rotten bark of Alnus sp., 25 October 2020, Z.Q. Zeng, H.D. Zheng, X.C. Wang, C. Liu 12672 (holotype HMAS 290894).

DNA barcodes: ITS OP205475, BenA OP205324, ACL1 OP493559, TEF1 OP493562.

The mycelium was not visible on the natural substratum. Perithecia were superficial, solitary to gregarious, non-stromatic or with a basal stroma, subglobose to globose, with very low papilla and slightly roughened surface; they mostly did not collapse upon drying, and a few were slightly pinched at the apical portion, colored pale yellow to pale orange-yellow. There was no color change in 3% KOH or 100% LA, and the size was 304–353 × 294–392 μm. Perithecial walls were two-layered, 40–70 μm thick; the outer layer was of textura globulosa to textura angularis, 30–45 μm thick, with cells 5–15 × 3–12 μm and cell walls 0.8–1 μm thick. The inner layer was of textura prismatica, 10–25 μm thick, with cells 8–14 × 2.5–3.5 μm and cell walls 1–1.2 μm thick. Asci were clavate to subcylindrical, eight-spored, with a round and simple apex, and 60–85 × 6–13 μm. Ascospores were ellipsoidal to elongate-ellipsoidal, uniseptate, hyaline, spinulose, and uniseriate or irregular-biseriate, and 13–16 × 4.5–5.5 μm.

Figure 2.

Clonostachys chongqingensis (holotype). (a,b) Ascomata on natural substratum; (c) colony after 2 weeks at 25 °C on PDA; (d) colony after 2 weeks at 25 °C on SNA; (e) median section through the perithecium; (f) asci with ascospores; (g–k) ascospore; (l,m) conidiophores, phialides, and conidia. Bars: (a,b) = 1 mm; (e) = 50 μm; (f–m) = 10 μm.

Colonies on PDA were 53 mm in diam. in average after 2 weeks at 25 °C; their surface was cottony, with a dense, whitish aerial mycelium. Colonies on SNA were 50 mm in diam. in average after 2 weeks at 25 °C; their surface was velvet, with a sparse, whitish aerial mycelium. Conidiophores were acremonium- to verticillium-like, arising from aerial hyphae and septate. Phialides were subulate tapered toward the apex, 15–74 μm long, 1.6–2.5 μm wide at the base, and 0.3–0.4 μm wide at the tip. Conidia were ellipsoidal to rod-shaped, unicellular, smooth-walled, hyaline, and 4–10 × 2.5–4 μm.

Notes: Morphologically, the species most resembles C. sesquicillii Schroers in having superficial, solitary to gregarious ascomata and clavate to subcylindrical asci with eight ellipsoidal, single-septate, spinulose ascospores [1]. However, the perithecia of the latter are often laterally or apically pinched when dry and have shorter asci (35–63 μm long) and smaller ascospores (8.2–14.4 × 2.2–4.4 μm) [1]. The two-locus phylogeny indicated the two fungi are remotely related (Figure 1).

Phylogenetically, C. chongqingensis is closely related to C. zelandiaenovae (Figure 1). The latter differs in its well-developed stroma, narrowly clavate asci with an apex ring, and wider ascospores (3.8–7.4 μm wide) [1].

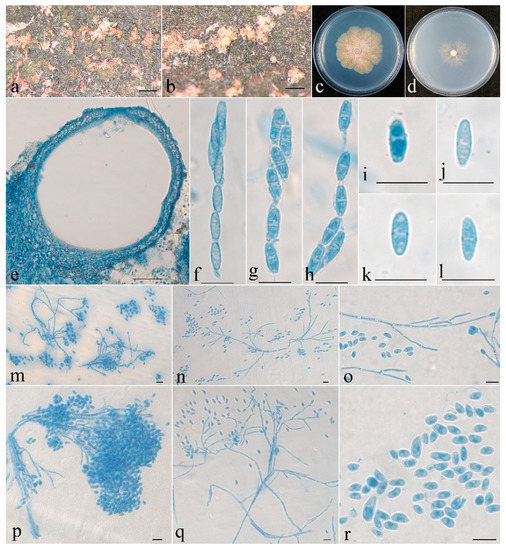

- Clonostachys leptoderma Z.Q. Zeng and W.Y. Zhuang, sp. nov. (Figure 3)

Fungal Names: FN571277.

Etymology: The specific epithet refers to the thin-walled perithecia.

Typification: China, Chongqing City, Jinyun Mountain, 29°49′46″ N 106°22′49″ E, on rotten bark, 23 October 2020, Z.Q. Zeng, H.D. Zheng, X.C. Wang, C. Liu 12581 (holotype HMAS 255834).

DNA barcodes: ITS OP205474, BenA OP205323, RPB1 OP493564, TEF1 OP493561.

Figure 3.

Clonostachys leptoderma (holotype). (a,b) Ascomata on natural substratum; (c) colony after 2 weeks at 25 °C on PDA; (d) colony after 2 weeks at 25 °C on SNA; (e) median section through the perithecium; (f–h) asci with ascospores; (i–l) ascospore; (m–q) conidiophores, phialides, and conidia; (r) conidia. Bars: (a,b) = 1 mm; (e) = 50 μm; (f–r) = 10 μm.

The mycelium was not visible on the natural substratum. Perithecia were superficial, solitary to gregarious, with a well-developed stroma, subglobose to globose, non-papillate, with surface slightly roughened, and did not collapse upon drying. They were pinkish-white, did not change color in 3% KOH or 100% LA, and were with a size of 216–284 × 206–265 μm. Perithecial walls were two-layered, 13–45 μm thick; the outer layer was of textura globulosa to textura angularis, 8–23 μm thick, with cells 5–10 × 4–8 μm and cell walls 1–1.2 μm thick; the inner layer was of textura prismatica, 5–22 μm thick, with cells 5–12 × 2–3 μm and cell walls 0.8–1 μm thick. Asci were clavate to subcylindrical, 6–8-spored, with a round and simple apex, and 53–63 × 4.8–7 μm. Ascospores were ellipsoidal to elongate-ellipsoidal, uniseptate, hyaline, spinulose, uniseriate or irregular-biseriate, and 7.5–11 × 2.5–3.5 μm.

Colonies on PDA was 31 mm in diam. in average after 2 weeks at 25 °C; their surface was cottony, with a dense, whitish aerial mycelium, and it produced a yellowish-brown pigment in medium. Colony on SNA were 18 mm in diam. in average after 2 weeks at 25 °C, with a sparse, whitish aerial mycelium. Conidiophores were verticillium-like, arising from aerial hyphae; they were septate, with dense phialides. Phialides were subulate, tapering toward the apex, 9–18 μm long, 1.5–2.5 μm wide at the base, and 0.2–0.3 μm wide at the tip. Conidia were subglobose, ellipsoidal to subellipsoidal, unicellular, smooth-walled, hyaline, and 2–7 × 2–5 μm.

Notes: Morphologically, the fungus is most similar to C. epichloe Schroers in having solitary to gregarious perithecia and ellipsoidal, bi-cellular, spinulose ascospores of a similar size [1]. Nevertheless, the latter differs in its smaller perithecia (140–240 × 140–200 μm) that is pinched when dry, its wider asci (5–10 μm wide) [1], and the presence of 36 bp and 132 bp divergences in the ITS and BenA regions. Obviously, they are not conspecific.

Phylogenetically, C. leptoderma is closely related to C. capitata and C. agrawalii (Figure 1). Clonostachys capitata can be differentiated by its thicker perithecial wall (45–60 μm thick), wider asci (7–12 μm wide), and larger ascospores (11.6–18.8 × 3.6–5.8 μm) [1]. Clonostachys agrawalii, which is known to have only an asexual stage, can be easily distinguished by its bi- to quarter-verticillate conidiophores and its cylindrical to flask-shaped, somewhat larger phialides (7–42 × 1.4–3.4 μm) [1].

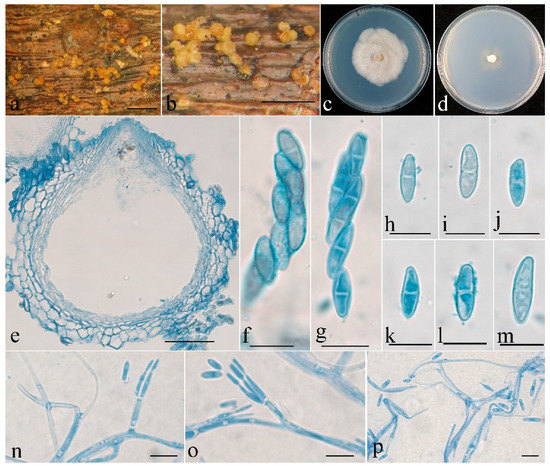

- Clonostachys oligospora Z.Q. Zeng and W.Y. Zhuang, sp. nov. (Figure 4)

Fungal Names: FN571278.

Etymology: The specific epithet refers to the very few conidia produced.

Typification: China, Yunnan Province, Chuxiong Prefecture, Zixi Mountain, Xianrengu, 25°54′0″ N 101°24′46″ E, on a rotten twig, 23 September 2017, Y. Zhang, H.D. Zheng, X.C. Wang, Y.B. Zhang 11691 (holotype HMAS 290895).

DNA barcodes: ITS OP205473, BenA OP205322, ACL1 OP493560, RPB1 OP493563.

The mycelium was not visible on the natural substratum. Perithecia were superficial, solitary to gregarious, either with a basal stroma or non-stromatic. They were subglobose to globose and papillate, with surface slightly warted; the warts were 6–25 μm high. They did not collapse upon drying, were colored pale yellow to light yellow, did not change color in 3% KOH or 100% LA, and were 225–274 × 225–265 μm. The perithecial walls were two-layered, 25–48 μm thick; the outer layer was of textura globulosa to textura angularis, 15–38 μm thick, with cells 8–18 × 9–15 μm and cell walls 0.5–0.8 μm thick; the inner layer was of textura prismatica, 10–15 μm thick, with cells 5–8 × 1.5–2.5 μm and cell walls 0.8–1 μm thick. Asci were clavate, 6–8-spored, with a rounded and simple apex, and 45–65 × 7.5–11 μm. Ascospores were ellipsoidal, uniseptate, hyaline, smooth-walled, uniseriate or irregular biseriate, and 9–17 × 3–5.5 μm.

Colonies on PDA were 50 mm in diam. in average after 2 weeks at 25 °C; their surface was cottony, with a dense, whitish aerial mycelium. Colonies on SNA were 25 mm in diam. in average after 2 weeks at 25 °C, with a sparse, whitish aerial mycelium. Conidiophores were verticillium-like, arising from aerial hyphae, and septate. Phialides were subulate, tapering toward the apex, 9–15 μm long; they were 1.5–2.5 μm wide at the base and 0.2–0.3 μm wide at the tip. Conidia were sparse, subfusiform, unicellular, smooth-walled, hyaline, and 5–13 × 1.8–2.2 μm.

Notes: Among the known species of Clonostachys, this fungus resembles C. setosa (Vittal) Schroers in terms of solitary to gregarious perithecia and ascospores that are ellipsoidal, bi-cellular, smooth-walled, and of a similar size [1]. However, the latter fungus is distinguished by asci with an apical ring, as well as by conidiophores that are penicillium-like and cylindrical conidia that are slightly larger (8.6–19.2 × 2–3.2 μm) [1]. In addition, there are 47 bp and 128 bp divergences in the ITS and BenA regions between HMAS 290895 and CBS 834.91. Both morphology and DNA sequence data support their distinction at the species level.

Figure 4.

Clonostachysoligospora (holotype). (a,b) Ascomata on natural substratum; (c) colony after 2 weeks at 25 °C on PDA; (d) colony after 2 weeks at 25 °C on SNA; (e) median section through the perithecium; (f,g) asci with ascospores; (h–m) ascospore; (n–p) conidiophores, phialides, and conidia. Bars: (a,b) = 1 mm; (e) = 50 μm; (f–p) = 10 μm.

4. Discussion

Although Clonostachys was established in 1839, the name was not commonly used until Schroers’ monographic treatment of the genus, from which 44 species were accepted [1]. The generic name Bionectria Speg. was introduced later [40], and the genus was reviewed by Rossman et al. [41]; in that work, the species included those previously placed in the Nectria ochroleuca group, the N. ralfsii group, and the N. muscivora group, as well as those having Sesquicillium W. Gams asexual stages. Clonostachys and Bionectria are of anamorph and teleomorph connections [1,41]. According to the current International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants [42], under the principle that one fungus requires one name, Clonostachys was recommended as the preferable name [43].

The previous phylogenetic overview of Clonostachys that was based on two-locus (ITS and BenA) sequence analyses showed that the genus is monophyletic [19,20]. Our analyses provided a similar tree topology, and species of the genus formed a well-supported clade (MPBP/MLBP/BIPP = 100%/100%/100%), including the three new taxa (Figure 1). Clonostachys oligospora is a well-separated lineage in between C. indica Prasher & R. Chauhan and C. samuelsii Schroers. Clonostachys chongqingensis clustered with C. zelandiaenovae, receiving relatively high statistical support (MPBP/MLBP/BIPP = 94%/96%/100%), and had moderate sequence divergences, i.e., 11/518 bp (2.1%) for ITS and 15/557 bp (2.7%) for BenA. Clonostachys leptoderma was grouped with C. agrawalii and C. capitata, which is poorly supported. Compared with the previously demonstrated phylogenies [19,20], minor changes were detected. For example, C. pseudostriata Schroers formerly constituted a separate lineage by itself [19,20]; whereas, with the joining of the new species, the fungus seemed to be closely related to C. krabiensis Tibpromma & K.D. Hyde and C. viticola C. Torcato & A. Alves, with low statistical support. Comparisons between each new species and closely related taxa are provided in Table 2. Along with the discovery of additional new species, the relationships among the species of the genus will become well-established.

Table 2.

Morphological comparisons of the new species and their close relatives.

More than 220 secondary metabolites have been reported from species of the genus. For example, C. byssicola, C. candelabrum (Bonord.) Schroers, C. compactiuscula (Sacc.) D. Hawksw. & W. Gams, C. grammicospora Schroers & Samuels, C. pityrodes Schroers, C. rogersoniana Schroers, and C. rosea were demonstrated to have the potential for biocontrol application [4,44,45,46,47]. Meanwhile, strains of C. rosea were occasionally reported as an opportunistic phytopathogen [48,49]. Therefore, studies on the biodiversity of Clonostachys are of theoretical and practical importance and need to be carried out continuously and extensively. China is diverse in climate, vegetation, and geographic structures and has rich niches for organisms [50,51]. Large-scale surveys in unexplored regions will significantly improve our knowledge of fungal species diversity.

5. Conclusions

The species diversity of the genus Clonostachys was investigated, and three new species were discovered. With the joining of the new species, the phylogenetic relationships among species of the genus are updated.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.-Y.Z.; methodology, Z.-Q.Z.; software, Z.-Q.Z.; validation, Z.-Q.Z.; formal analysis, Z.-Q.Z.; investigation, Z.-Q.Z.; resources, W.-Y.Z. and Z.-Q.Z.; data curation, Z.-Q.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.-Q.Z.; writing—review and editing, W.-Y.Z. and Z.-Q.Z.; visualization, Z.-Q.Z.; supervision, Z.-Q.Z. and W.-Y.Z.; project administration, W.-Y.Z.; funding acquisition, W.-Y.Z. and Z.-Q.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31870012, 31750001), the National Project on Scientific Groundwork, Ministry of Science and Technology of China (2019FY100700), and the Frontier Key Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (QYZDY-SSWSMC029).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The names of the new species were formally registered in the database Fungal Names (https://nmdc.cn/fungalnames (accessed on 11 August 2022)). Specimens were deposited in the Herbarium Mycologicum Academiae Sinicae (HMAS). The newly generated sequences were deposited in GenBank (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank (accessed on 22 September 2022)).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank H.D. Zheng, X.C. Wang, Y.B. Zhang, Y. Zhang, and C. Liu for collecting specimens jointly for this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Schroers, H.J. A monograph of Bionectria (Ascomycota, Hypocreales, Bionectriaceae) and its Clonostachys anamorphs. Stud. Mycol. 2001, 46, 1–214. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W.H.; Han, Y.F.; Liang, J.D.; Zou, X.; Liang, Z.Q.; Jin, D.C. A new araneogenous fungus of the genus Clonostachys. Mycosystema 2016, 35, 1061–1069. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Torcato, C.; Gonçalves, M.F.M.; Rodríguez-Gálvez, E.; Alves, A. Clonostachys viticola sp. nov., a novel species isolated from Vitis vinifera. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2020, 70, 4321–4328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, P.P.; Zhang, X.P.; Xu, D.; Zhang, B.W.; Lai, D.W.; Zhou, L.G. Metabolites from Clonostachys fungi and their biological activities. J. Fungi 2020, 6, 229. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, C.J.; Kim, C.J.; Bae, K.S.; Kim, Y.H.; Kim, W.G. Bionectins A-C, epidithiodioxopiperazines with anti-MRSA activity, from Bionectria byssicola F120. J. Nat. Prod. 2006, 69, 1816–1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iqbal, M.; Dubey, M.; McEwan, K.; Menzel, U.; Franko, M.A.; Viketoft, M.; Jensen, D.F.; Karlsson, M. Evaluation of Clonostachys rosea for control of plant-parasitic Nematodes in soil and in roots of carrot and wheat. Phytopathology 2018, 108, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, W.Y. (Ed.) Flora Fungorum Sinicorum. Vol. Nectriaceae et Bionectriaceae; Science Press: Beijing, China, 2013; p. 162. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Rossman, A.Y. Lessons learned from moving to one scientific name for fungi. IMA Fungus 2014, 5, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombard, L.; Van der Merwe, N.A.; Groenewald, J.Z.; Crous, P.W. Generic concepts in Nectriaceae. Stud. Mycol. 2015, 80, 189–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dao, H.T.; Beattie, G.A.C.; Rossman, A.Y.; Burgess, L.W.; Holford, P. Four putative entomopathogenic fungi of armoured scale insects on Citrus in Australia. Mycol. Prog. 2016, 15, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, G.M.; Abreu, L.M.; Carvalho, V.G.; Schroers, H.J.; Pfenning, L.H. Multilocus phylogeny of Clonostachys subgenus Bionectria from Brazil and description of Clonostachys chloroleuca sp. nov. Mycol. Prog. 2016, 15, 1031–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasher, I.B.; Chauhan, R. Clonostachys indicus sp. nov. from India. Kavaka 2017, 48, 22–26. [Google Scholar]

- Lechat, C.; Fournier, J. Clonostachys spinulosispora (Hypocreales, Bionectriaceae), a new species on palm from French Guiana. Ascomycete.org 2018, 10, 127–130. [Google Scholar]

- Lechat, C.; Fournier, J. Two new species of Clonostachys (Bionectriaceae, Hypocreales) from Saül (French Guiana). Ascomycete.org 2020, 12, 61–66. [Google Scholar]

- Tibpromma, S.; Hyde, K.D.; McKenzie, E.H.C.; Bhat, D.J.; Phillips, A.J.L.; Wanasinghe, D.N.; Samarakoon, M.C.; Jayawardena, R.S.; Dissanayake, A.J.; Tennakoon, D.S.; et al. Fungal diversity notes 840–928: Micro-fungi associated with Pandanaceae. Fungal Divers. 2018, 93, 1–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lechat, C.; Fournier, J.; Chaduli, D.; Lesage-Meessen, L.; Favel, A. Clonostachys saulensis (Bionectriaceae, Hypocreales), a new species from French Guiana. Ascomycete.org 2019, 11, 65–68. [Google Scholar]

- Lechat, C.; Fournier, J.; Gasch, A. Clonostachys moreaui (Hypocreales, Bionectriaceae), a new species from the island of Madeira (Portugal). Ascomycete.org 2020, 12, 35–38. [Google Scholar]

- Forin, N.; Vizzini, A.; Nigris, S.; Ercole, E.; Voyron, S.; Girlanda, M.; Baldan, B. Illuminating type collections of nectriaceous fungi in Saccardo’s fungarium. Persoonia 2020, 45, 221–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyde, K.D.; Dong, Y.; Phookamsak, R.; Jeewon, R.; Bhat, D.J.; Jones, E.B.G.; Liu, N.; Abeywickrama, P.D.; Mapook, A.; Wei, D.; et al. Fungal diversity notes 1151–1276: Taxonomic and phylogenetic contributions on genera and species of fungal taxa. Fungal Divers. 2020, 100, 5–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perera, R.H.; Hyde, K.D.; Maharachchikumbura, S.S.N.; Jones, E.B.G.; McKenzie, E.H.C.; Stadler, M.; Lee, H.B.; Samarakoon, M.C.; Ekanayaka, A.H.; Camporesi, E.; et al. Fungi on wild seeds and fruits. Mycosphere 2020, 11, 2108–2480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Z.Q.; Zhuang, W.Y. Three new Chinese records of Hypocreales. Mycosystema 2017, 36, 654–662. [Google Scholar]

- Hirooka, Y.; Kobayashi, T.; Ono, T.; Rossman, A.Y.; Chaverri, P. Verrucostoma, a new genus in the Bionectriaceae from the Bonin islands, Japan. Mycologia 2010, 102, 418–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nirenberg, H.I. Studies on the morphologic and biologic differentiation in Fusarium section Liseola. Mitt. Biol. Bundesanst. Land-Forstw. 1976, 169, 1–117. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Zhuang, W.Y. Designing primer sets for amplification of partial calmodulin genes from penicillia. Mycosystema 2004, 23, 466–473. [Google Scholar]

- White, T.J.; Bruns, T.; Lee, S.; Taylor, J. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. In PCR Protocols: A Guide to Methods and Applications; Innis, M.A., Gelfland, D.H., Sninsky, J.J., White, T.J., Eds.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1990; pp. 315–322. [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell, K.; Cigelnik, E. Two divergent intragenomic rDNA ITS2 types within a monophyletic lineage of the fungus Fusarium are nonorthologous. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 1997, 7, 103–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gräfenhan, T.; Schroers, H.J.; Nirenberg, H.I.; Seifert, K.A. An overview of the taxonomy, phylogeny and typification of nectriaceous fungi in Cosmospora, Acremonium, Fusarium, Stilbella and Volutella. Stud. Mycol. 2011, 68, 79–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castlebury, L.A.; Rossman, A.Y.; Sung, G.H.; Hyten, A.S.; Spatafora, J.W. Multigene phylogeny reveals new lineage for Stachybotrys chartarum, the indoor air fungus. Mycol. Res. 2004, 108, 864–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbone, I.; Kohn, L.M. A method for designing primer sets for speciation studies in filamentous ascomycetes. Mycologia 1999, 91, 553–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donnell, K.; Kistler, H.C.; Cigelnik, E.; Ploetz, R.C. Multiple evolutionary origins of the fungus causing Panama disease of banana: Concordant evidence from nuclear and mitochondrial gene genealogies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1998, 95, 2044–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, T.A. BioEdit: A user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/NT. Nucleic Acids Symp. Ser. 1999, 41, 95–98. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, J.D.; Gibson, T.J.; Plewniak, F.; Jeanmougin, F.; Higgin, D.G. The ClustalX windows interface: Flexible strategies for multiple sequences alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997, 25, 4876–4883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swofford, D.L. PAUP 4.0b10: Phylogenetic Analysis Using Parsimony (* and Other Methods); Sinauer Associates: Sunderland, MA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Ronquist, F.; Huelsenbeck, J.P. MrBayes 3: Bayesian phylogenetic inference under mixed models. Bioinformatics 2003, 19, 1572–1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nylander, J.A.A. MrModeltest v2.0. Program Distributed by the Author; Evolutionary Biology Centre, Uppsala University: Uppsala, Sweden, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, L.T.; Schmidt, H.A.; von Haeseler, A.; Minh, B.Q. IQ-TREE: A fast and effective stochastic algorithm for estimating maximum likelihood phylogenies. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2015, 32, 268–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chernomor, O.; von Haeseler, A.; Minh, B.Q. Terrace aware data structure for phylogenomic inference from supermatrices. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2016, 65, 997–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, R.D. TreeView: An application to display phylogenetic trees on personal computers. Comp. Appl. Biosci. 1996, 12, 357–358. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cunningham, C.W. Can three incongruence tests predict when data should be combined? Mol. Biol. Evol. 1997, 14, 733–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spegazzini, C. Fungi costaricenses nonnulli. Bol. Acad. Nac. Cienc. Córdoba 1919, 23, 541–609. [Google Scholar]

- Rossman, A.Y.; Samuels, G.J.; Rogerson, C.T.; Lowen, R. Genera of Bionectriaceae, Hypocreaceae and Nectriaceae (Hypocreales, Ascomycetes). Stud. Mycol. 1999, 42, 1–248. [Google Scholar]

- Turland, N.J.; Wiersema, J.H.; Barrie, F.R.; Greuter, W.; Hawksworth, D.L.; Herendeen, P.S.; Knapp, S.; Kusber, W.H.; Li, D.Z.; Marhold, K.; et al. International Code of Nomenclature for Algae, Fungi, and Plants (Shenzhen Code); Koeltz Scientific Books: Berlin, Germany, 2018; p. 254. [Google Scholar]

- Rossman, A.Y.; Seifert, K.A.; Samuel, G.J.; Minnis, A.M.; Schroers, H.J.; Lombard, L.; Crous, P.W.; Põldma, K.; Cannon, P.F.; Summerbel, R.C.; et al. Genera in Bionectriaceae, Hypocreaceae, and Nectriaceae (Hypocreales) proposed for acceptance or rejection. IMA Fungus 2013, 4, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Ren, F.; Guo, Z.; Liu, J.; Liu, X.; Liu, G.; Che, Y. Rogersonins A and B, imidazolone N-oxide-incorporating indole alkaloids from a verG disruption mutant of Clonostachys rogersoniana. J. Nat. Prod. 2019, 82, 462–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouchi, T.; Watanabe, Y.; Nonaka, K.; Muramatsu, R.; Noguchi, C.; Tozawa, M.; Hokari, R.; Ishiyama, A.; Koike, R.; Matsui, H.; et al. Clonocoprogens A, B and C, new antimalarial coprogens from the Okinawan fungus Clonostachys compactiuscula FKR-0021. J. Antibiot. 2020, 73, 365–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.B.; Li, S.D.; Ren, Q.; Xu, J.L.; Lu, X.; Sun, M.H. Biology and applications of Clonostachys rosea. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2020, 129, 486–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, T.; Xiang, L.G.; Zhuang, W.Y.; Zeng, Z.Q.; Yu, Z.H. Screening of antagonistic Closnostachys strains against Phytophthora nicotianae. Microbiol. China 2022, 49, 3860–3872. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.A.; Kang, M.J.; Kim, T.D.; Park, E.J. First report of Clonostachys rosea causing root rot of Gastrodia elata in Korea. Plant Dis. 2020, 104, 3069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, M.E.; Parvin, M.S. First report of Clonostachys rosea causing root rot of Beta vulgaris in North Dakota, USA. New Dis. Rep. 2020, 42, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Z.Q.; Zhuang, W.Y. Current understanding of the genus Hypomyces (Hypocreales). Mycosystema 2015, 34, 809–816. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Y.N.; Mao, X.L. (Eds.) 100 Years of Mycology in China; Science Press: Beijing, China, 2015; p. 763. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).