Abstract

In this perspective, we discuss the limitations of medical guidelines as it relates to the management of uncommon invasive fungal infections (IFIs) or infrequent manifestations of more common IFIs. We emphasize the difficulties to define “gold standards” for diagnostics and treatment based on limited and low-quality evidence. We posit that such “guidelines” based on scarce data may be suboptimal and could be in some cases even harmful. Specifically, guidelines are often seen as rigid rules to follow which can prevent a critical examination of the nuanced management of individual patients with rare IFIs. We also emphasize that guidelines are often not updated frequently enough and therefore may not reflect the current treatment landscape. For all those reasons, we suggest that the term “guidance” may be more appropriate than “guidelines” for rare IFIs. Finally, we pose several questions regarding constructing future “Guidelines”/“Guidance for such entities”.

What constitutes a guideline is controversial and has spurred debates in their relevance to medical practices [1,2,3]. Although written with good intentions and providing notable benefits, they could also pose distinct challenges to heath care providers, patients, and heath care utilization [4]. Specifically, guidelines could inadvertently steer prescribing practices down potentially uncertain paths and often perpetuate the mentality of groupthink and agreeable narratives anchored on a less-than-compelling evidence base. One has witnessed those conundrums with the surviving sepsis campaign, management of cardiovascular diseases, and even dosing schemes of antimicrobial guidelines [5,6,7]. The practice of indiscriminately conforming to published guidelines has led to “mandates,” influenced billing practices, and set tones for “standards of care.” The debate intensifies when guidelines are developed for uncommon diseases. In these unfamiliar scenarios, providers turn to the best available information for guidance of guidelines, which are written based on limited literature of anecdotal cases; small, retrospective, often-single-institution studies; or registries that might be unsuitable for guideline construction [8,9,10,11]. However, the best use for uncontrolled small series is the description of toxicities of therapies, recognition of epidemics, and initial identification of unrecognized syndromes [12].

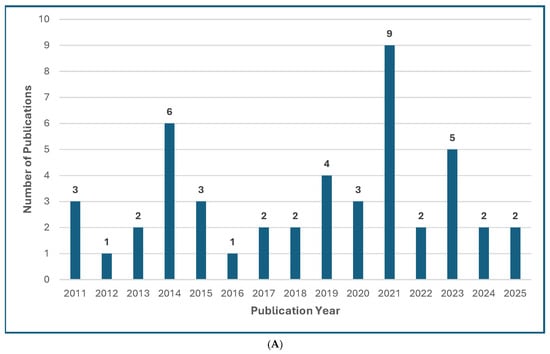

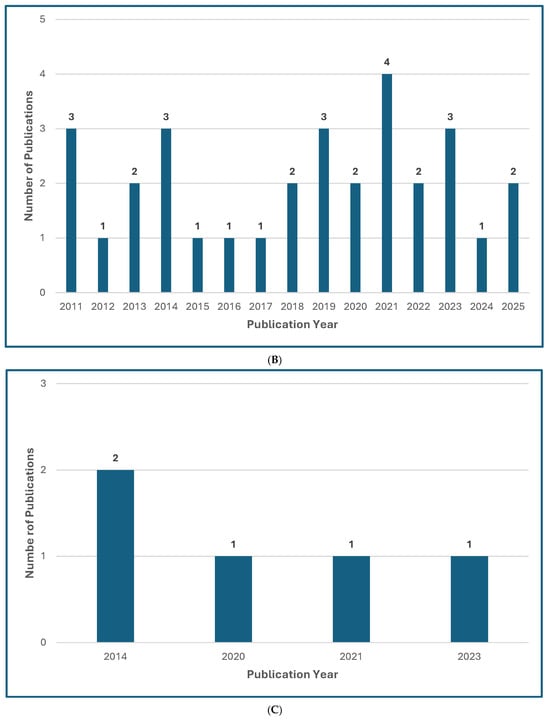

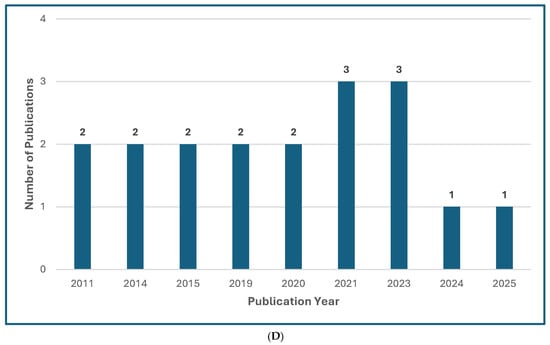

Several recently published manuscripts offer global guidelines for the diagnosis and management of rare opportunistic yeast and mold infections [13,14,15,16,17,18] (Figure 1), which has compounded widespread “guideline fatigue.” The authors of these guidelines are to be commended for summarizing a large volume of literature and for trying to offer their best practical guidance for very complex and unusual mycoses. Admittedly, the senior author of this editorial has participated as a coauthor or senior author of “guidelines” focusing on rare mycoses, or from commenting on the treatment of unusual manifestations or clinical scenarios of common mycoses [15,16,17,18].

Many issues exist for guidelines for rare mycoses, which are multifactorial. Specifically, case reports, short case series, and synthesis of data from registries are challenged by publication and reporting biases. For example, there is no denominator nor is there a sense of what is reported as the typical manifestations of a particular rare fungal disease [19,20,21]. The heterogeneity and complexity of such entities is significant [22]. The same argument can be made for uncommon manifestations of the most frequent mycoses such as candidiasis, aspergillosis, and cryptococcosis where the pivotal randomized controlled studies focused on the predominant clinical manifestations of those mycoses (i.e., fungemia for Candida, lung infections for Aspergillus, and meningitis in Cryptococcus [23,24,25,26,27,28]). Specifically, there is a paucity of quality data to inform the practice of unusual clinical manifestations of common mycoses (e.g., Candida endocarditis [29]), and those are subject to the same uncertainties seen with developing therapeutic recommendations of rare mycosis.

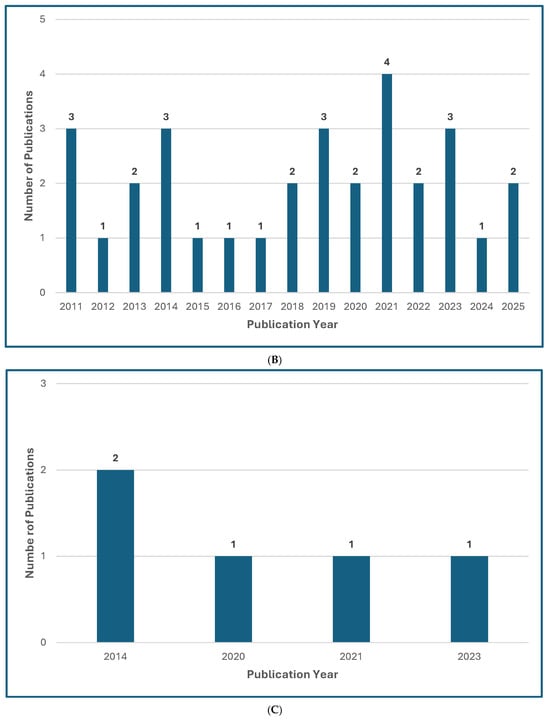

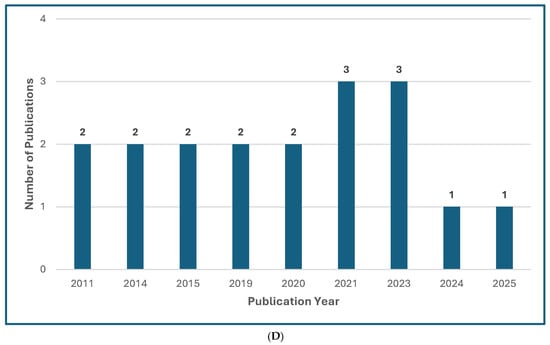

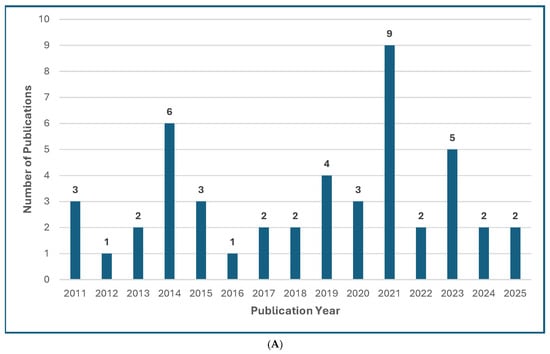

Figure 1.

Treatment Guideline Trends for Unusual or Rare Fungi. (A) Trend of Publications on Treatment Guidelines for Unusual Fungal Infections, n = 47 [13,14,18,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73]. (B) Trend of Publications on Treatment Guidelines Mentioning Mucormycosis, n = 31 [18,31,33,34,35,36,39,40,41,42,43,44,48,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,61,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,71,73]. (C) Trend of Publications on Treatment Guidelines Mentioning Only Rare Molds (not Aspergillus, not Mucorales), n = 5 [14,38,60,62,72]. (D) Trend of Publications on Treatment Guidelines Mentioning Rare Yeasts, n = 18 [13,30,31,33,37,38,41,42,45,47,55,58,59,60,62,65,67,70]. A qualified medical librarian conducted a comprehensive search of literature published from 2005 to 2025. Medline (Ovid), Embase (Ovid), and Scopus were queried using both natural language and controlled vocabulary terms for clinical guidelines, recommendations, consensus statements, and best practices; relevant mold and yeast organism terms; and terms related to international, national, and professional medical societies. After deduplication, 77 relevant results were identified. We excluded guidelines not available in English and pediatric guidelines and included a total of 47 guideline publications.

To compound the challenges, it is unclear at times if those unusual fungi reported in case reports, case series, or registries contain misidentified fungi. Those misclassification errors could result in erroneous conclusions. The difficulties in proper identification and differentiation of some of these uncommon fungi on morphological grounds is at times challenging for the average clinical laboratory, as these labs do not have the critical volume of cases and the expertise in identification of uncommon fungi. Although rapid diagnostic platforms, such as Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization Time-of-Flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF), holds promise as a fast and accurate identification tool for fungal identification, its performance might be less robust for the identification of uncommon fungi due to lack of expanded libraries for such fungi [74]. The problem of fungal identification is further amplified in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) that often lack the appropriate infrastructure for reliable identification of fungi, especially the uncommon fungi [75]. Of note, such global guidelines have been developed to promote diagnosis and management of invasive fungal infections (IFIs), including rare IFIs in LMIC [76]. Unless these fungi are reliably identified by molecular phylogenetic methods, classification biases remain a concern.

In addition to all these quandaries, unusual fungal infections afflict a very heterogeneous population at risk, ranging from immunocompetent patients (e.g., mold infections such as mucormycosis following trauma, rare yeast infections in intravenous drug users) to patients with profound and complex defects in a net state of immunosuppression. Most of these infections have no surrogate biomarkers for early diagnosis. Additionally, there is a diversity of affected sites, and the correlation of cell-free in vitro susceptibility with outcomes is difficult to ascertain [77]. Additional confounders are the common co-infections [76], especially in high-risk patients [78], and the “survival bias” in patients who recover from neutropenia or have their metabolic effect corrected [22].

Treatment recommendations are even more problematic to be codified into “guidelines” of uncommonly reported and intrinsically resistant yeasts [79] and molds [18]. Many such patients are treated with a variety of combination and salvage therapies, making it increasingly difficult to discern which antifungal therapy should really be used. Importantly, very ill patients with uncommon opportunistic mycoses have multiple interventions occurring simultaneously or sequentially [22], including surgery, and do not account for the activity of agents in the context of continuous immunosuppression [80]. This adds several levels of complexity in assessment. For example, fusariosis seen at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center has been an uncommon infection typically seen in patients with relapsed or refractory hematologic cancers, and its outcome is predominantly host-driven [81]. The lack of association between antifungal in vitro susceptibilities with fusariosis outcomes demonstrates the intricacies of interpreting laboratory data and fusariosis management [22,77,82], where poor host immunity was the key decider of antifungal response, especially for opportunistic mycoses.

Finally, guidelines are not routinely published on a reliable schedule. Oftentimes, it takes several years, sometimes nearly a decade, for guidelines to update. For example, the ESCMID and ECMM guidelines for rare yeasts were published in 2014 and were not updated until 2021 [13,30]. The delayed process of reviewing and publishing also means that information is behind the times and does not account for the best currently available data. This frequently leaves out potential advances in therapy of the newer promising agents [83].

We believe that a better term might be guidance instead of guidelines and that providers should have a healthy cautionary approach when interpreting published “guidelines” without the nuances of patient-level individualization [51]. Several interesting questions remain when one constructs a thoughtful guidance/guideline for mycoses in general, and even more importantly, for rare mycoses (Table 1).

Table 1.

Questions regarding constructing fungal “Guidelines”/“Guidance”.

Author Contributions

D.P.K., conceptualization; N.N.V. and D.P.K., data curation, preparation, review and editing; D.P.K., supervision and project administration. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Rachel S. Hicklen, from the Research Medical Library at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, for her expert assistance with the information to produce the figure. D.P.K. acknowledges the Robert C. Hickey Endowment in Clinical Care.

Conflicts of Interest

NNV declares no conflict of interest. DPK received research support from Astellas Pharma; received consultant fees from Astellas Pharma, Matinas, Basilea, Knight, Inc., Gilead Sciences, and AVIR pharma; and is a member of the data review committee for MundiPharma Therapeutics, AbbVie, and the Mycoses Study Group.

References

- Guallar, E.; Laine, C. Controversy over clinical guidelines: Listen to the evidence, not the noise. Ann. Intern. Med. 2014, 160, 361–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spellberg, B.; Shorr, A.F. Opinion-Based Recommendations: Beware the Tyranny of Experts. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2021, 8, ofab490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spellberg, B.; Wright, W.F.; Shaneyfelt, T.; Centor, R.M. The Future of Medical Guidelines: Standardizing Clinical Care With the Humility of Uncertainty. Ann. Intern. Med. 2021, 174, 1740–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolf, S.H.; Grol, R.; Hutchinson, A.; Eccles, M.; Grimshaw, J. Clinical guidelines: Potential benefits, limitations, and harms of clinical guidelines. BMJ 1999, 318, 527–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prescott, H.C.; Ostermann, M. What is new and different in the 2021 Surviving Sepsis Campaign guidelines. Med. Klin. Intensiv. Notfmed. 2023, 118 (Suppl. S2), 75–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rybak, M.J.; Le, J.; Lodise, T.; Levine, D.; Bradley, J.; Liu, C.; Mueller, B.; Pai, M.; Wong-Beringer, A.; Rotschafer, J.C.; et al. Executive Summary: Therapeutic Monitoring of Vancomycin for Serious Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Infections: A Revised Consensus Guideline and Review of the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, the Infectious Diseases Society of America, the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society, and the Society of Infectious Diseases Pharmacists. J. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. Soc. 2020, 9, 281–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teicholz, N. A short history of saturated fat: The making and unmaking of a scientific consensus. Curr. Opin. Endocrinol. Diabetes Obes. 2023, 30, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pande, A.; Non, L.R.; Romee, R.; Santos, C.A.Q. Pseudozyma and other non-Candida opportunistic yeast bloodstream infections in a large stem cell transplant center. Transpl. Infect. Dis. 2017, 19, e12664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajme-Lopez, S.; González-Lara, M.F.; Martínez-Gamboa, R.A.; Rangel-Cordero, A.; Ponce-de-León, A. Geotrichum spp: An overlooked and fatal etiologic agent in immunocompromised patients. A case series from a referral center in Mexico. Med. Mycol. 2022, 60, myac022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tshisevhe, V.; Mitton, B.; Skosana, L. Invasive Geotrichum klebahnii fungal infection: A case report. Access Microbiol. 2021, 3, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graeff, L.D.; Seidel, D.; Vehreschild, M.J.G.T.; Hamprecht, A.; Kindo, A.; Racil, Z.; Demeter, J.; De Hoog, S.; Aurbach, U.; Ziegler, M.; et al. Invasive infections due to Saprochaete and Geotrichum species: Report of 23 cases from the FungiScope Registry. Mycoses 2017, 60, 273–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kempen, J.H. Appropriate use and reporting of uncontrolled case series in the medical literature. Arch. Ophthalmol. 2011, 151, 7–10.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.C.-A.; Perfect, J.; Colombo, A.L.; Cornely, O.A.; Groll, A.H.; Seidel, D.; Albus, K.; de Almedia, J.N.; Garcia-Effron, G.; Gilroy, N.; et al. Global guideline for the diagnosis and management of rare yeast infections: An initiative of the ECMM in cooperation with ISHAM and ASM. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2021, 21, e375–e386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoenigl, M.; Salmanton-García, J.; Walsh, T.J.; Nucci, M.; Neoh, C.F.; Jenks, J.D.; Lackner, M.; Sprute, R.; Al-Hatmi, A.M.S.; Bassetti, M.; et al. Global guideline for the diagnosis and management of rare mould infections: An initiative of the European Confederation of Medical Mycology in cooperation with the International Society for Human and Animal Mycology and the American Society for Microbiology. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2021, 21, e246–e257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappas, P.G.; Kontoyiannis, D.P.; Perfect, J.R.; Chiller, T.M. Real-Time Treatment Guidelines: Considerations during the Exserohilum rostratum Outbreak in the United States. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2013, 57, 1573–1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, T.F.; Thompson, G.R., III; Denning, D.W.; Fishman, J.A.; Hadley, S.; Herbrecht, R.; Kontoyiannis, D.P.; Marr, K.A.; Morrison, V.A.; Nguyen, M.H.; et al. Practice Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Aspergillosis: 2016 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2016, 63, e1–e60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dadwal, S.S.; Hohl, T.M.; Fisher, C.E.; Boeckh, M.; Papanicolaou, G.; Carpenter, P.A.; Fisher, B.T.; Slavin, M.A.; Kontoyiannis, D. American Society of Transplantation and Cellular Therapy Series, 2: Management and Prevention of Aspergillosis in Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation Recipients. Transplant. Cell. Ther. 2021, 27, 201–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Douglas, A.P.; Lamoth, F.; John, T.M.; Groll, A.H.; Shigle, T.L.; Papanicolaou, G.A.; Chemaly, R.F.; Carpenter, P.A.; Dadwal, S.S.; Walsh, T.J.; et al. American Society of Transplantation and Cellular Therapy Series: #8-Management and Prevention of Non-Aspergillus Molds in Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation Recipients. Transplant. Cell. Ther. 2025, 31, 194–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skiada, A.; Pavleas, I.; Drogari-Apiranthitou, M. Rare fungal infectious agents: A lurking enemy. F1000Research 2017, 6, 1917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firacative, C. Invasive fungal disease in humans: Are we aware of the real impact? Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz. 2020, 115, e200430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmanton-García, J.; Koehler, P.; Kindo, A.; Falces-Romero, I.; García-Rodríguez, J.; Ráčil, Z.; Chen, S.C.-A.; Klimko, N.; Desoubeaux, G.; Thompson, G.R., III; et al. Needles in a haystack: Extremely rare invasive fungal infections reported in FungiScope®—Global Registry for Emerging Fungal Infections. J. Infect. 2020, 81, 802–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamoth, F.; Kontoyiannis, D.P. Therapeutic Challenges of Non-Aspergillus Invasive Mold Infections in Immunosuppressed Patients. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2019, 63, 10-1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pappas, P.G.; Kauffman, C.A.; Andes, D.R.; Clancy, C.J.; Marr, K.A.; Ostrosky-Zeichner, L.; Reboli, A.C.; Schuster, M.G.; Vazquez, J.A.; Walsh, T.J.; et al. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Candidiasis: 2016 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2016, 62, e1–e50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cornely, O.A.; Sprute, R.; Bassetti, M.; Chen, S.C.-A.; Groll, A.H.; Kurzai, O.; Lass-Flörl, C.; Ostrosky-Zeichner, L.; Rautemaa-Richardson, R.; Revathi, G.; et al. Global guideline for the diagnosis and management of candidiasis: An initiative of the ECMM in cooperation with ISHAM and ASM. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2025, 25, e280–e293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keighley, C.; Cooley, L.; Morris, A.J.; Ritchie, D.; Clark, J.E.; Boan, P.; Worth, L.J.; the Australasian Antifungal Guidelines Steering Committee. Consensus guidelines for the diagnosis and management of invasive candidiasis in haematology, oncology and intensive care settings, 2021. Intern. Med. J. 2021, 51 (Suppl. S7), 89–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, A.P.; Smibert, O.C.; Bajel, A.; Halliday, C.L.; Lavee, O.; McMullan, B.; Yong, M.K.; van Hal, S.J.; Chen, S.C.; the Australasian Antifungal Guidelines Steering Committee. Consensus guidelines for the diagnosis and management of invasive aspergillosis, 2021. Intern. Med. J. 2021, 51 (Suppl. S7), 143–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epelbaum, O.; Marinelli, T.; Haydour, Q.; Pennington, K.M.; Evans, S.E.; Carmona, E.M.; Husain, S.; Knox, K.S.; Jarrett, B.J.; Azoulay, E.; et al. Treatment of Invasive Pulmonary Aspergillosis and Preventive and Empirical Therapy for Invasive Candidiasis in Adult Pulmonary and Critical Care Patients: An Official American Thoracic Society Clinical Practice Guideline. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2025, 211, 34–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.C.; Harrison, T.S.; Bicanic, T.A.; Chayakulkeeree, M.; Sorrell, T.C.; Warris, A.; Hagen, F.; Spec, A.; Oladele, R.; Govender, N.P.; et al. Global guideline for the diagnosis and management of cryptococcosis: An initiative of the ECMM and ISHAM in cooperation with the ASM. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2024, 24, e495–e512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Ami, R.; Bassetti, M.; Bouza, E.; Kosman, A.; Vena, A.; ESCMID Fungal Infection Study Group. Candida endocarditis: Current perspectives on diagnosis and therapy. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arendrup, M.C.; Boekhout, T.; Akova, M.; Meis, J.F.; Cornely, O.A.; Lortholary, O.; ESCMID EFISG study group and ECMM. ESCMID and ECMM joint clinical guidelines for the diagnosis and management of rare invasive yeast infections. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2014, 20 (Suppl. S3), 76–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, S.B.; Ramasubramanian, V.; Prasad, N.; Saraf, N.; Soman, R.; Makharia, G.; Varughese, S.; Sahay, M.; Deswal, V.; Jeloka, T.; et al. South Asian Transplant Infectious Disease Guidelines for Solid Organ Transplant Candidates, Recipients, and Donors. Transplantation 2023, 107, 1910–1934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassetti, M.; Azoulay, E.; Kullberg, B.J.; Ruhnke, M.; Shoham, S.; Vazquez, J.; Giacobbe, D.R.; Calandra, T. EORTC/MSGERC Definitions of Invasive Fungal Diseases: Summary of Activities of the Intensive Care Unit Working Group. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021, 72 (Suppl. 2), S121–S127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, P.K.; Chakrabarti, A.; Sinha, S.; Pande, R.; Gupta, S.; Kumar, A.A.; Mishra, V.K.; Kumar, S.; Bhosale, S.; Reddy, P.K. ISCCM Position Statement on the Management of Invasive Fungal Infections in the Intensive Care Unit. Indian J. Crit. Care Med. 2024, 28 (Suppl. 2), S20–S41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blyth, C.C.; Gilroy, N.M.; Guy, S.D.; Chambers, S.T.; Cheong, E.Y.; Gottlieb, T.; McGuinness, S.L.; Thursky, K.A. Consensus guidelines for the treatment of invasive mould infections in haematological malignancy and haemopoietic stem cell transplantation, 2014. Intern. Med. J. 2014, 44, 1333–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brunet, K.; Rammaert, B. Mucormycosis treatment: Recommendations, latest advances, and perspectives. J. Mycol. Med. 2020, 30, 101007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bupha-Intr, O.; Butters, C.; Reynolds, G.; Kennedy, K.; Meyer, W.; Patil, S.; Bryant, P.; Morrissey, C.O.; Australasian Antifungal Guidelines Steering Committee. Consensus guidelines for the diagnosis and management of invasive fungal disease due to moulds other than Aspergillus in the haematology/oncology setting, 2021. Intern. Med. J. 2021, 51 (Suppl. 7), 177–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.C.; Blyth, C.C.; Chen, S.C.; Khanina, A.; Morrissey, C.O.; Roberts, J.A.; Thursky, K.A.; Worth, L.J.; Slavin, M.A.; Australasian Antifungal Guidelines Steering Committee. Introduction to the updated Australasian consensus guidelines for the management of invasive fungal disease and use of antifungal agents in the haematology/oncology setting, 2021. Intern. Med. J. 2021, 51 (Suppl. 7), 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhary, A.; Meis, J.F.; Guarro, J.; de Hoog, G.S.; Kathuria, S.; Arendrup, M.C.; Arikan-Akdagli, S.; Akova, M.; Boekhout, T.; Caira, M.; et al. ESCMID and ECMM joint clinical guidelines for the diagnosis and management of systemic phaeohyphomycosis: Diseases caused by black fungi. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2014, 20 (Suppl. 3), 47–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornely, O.A.; Alastruey-Izquierdo, A.; Arenz, D.; Chen, S.C.; Dannaoui, E.; Hochhegger, B.; Hoenigl, M.; Jensen, H.E.; Lagrou, K.; Lewis, R.E.; et al. Global guideline for the diagnosis and management of mucormycosis: An initiative of the European Confederation of Medical Mycology in cooperation with the Mycoses Study Group Education and Research Consortium. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2019, 19, e405–e421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornely, O.A.; Alastruey-Izquierdo, A.; Arenz, D.; Chen, S.C.A.; Dannaoui, E.; Hochhegger, B.; Hoenigl, M.; Jensen, H.E.; Lagrou, K.; Lewis, R.E.; et al. ESCMID and ECMM joint clinical guidelines for the diagnosis and management of mucormycosis 2013. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2014, 20 (Suppl. 3), 5–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Cossio Tejido, S.; Lleti, M.S. Impact of current clinical guidelines on the management of invasive fungal disease. Rev. Iberoam. Micol. 2025, 42, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freifeld, A.G.; Bow, E.J.; Sepkowitz, K.A.; Boeckh, M.J.; Ito, J.I.; Mullen, C.A.; Raad, I.I.; Rolston, K.V.; Young, J.A.; Wingard, J.R.; et al. Clinical practice guideline for the use of antimicrobial agents in neutropenic patients with cancer: 2010 update by the infectious diseases society of america. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2011, 52, e56–e93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Vidal, C.; Carratalà, J.; Lortholary, O. Defining standards of CARE for invasive fungal diseases in solid organ transplant patients. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2019, 74 (Suppl. 2), ii16–ii20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giudice, G.; Cutrignelli, D.A.; Sportelli, P.; Limongelli, L.; Tempesta, A.; Gioia, G.D.; Santacroce, L.; Maiorano, E.; Favia, G. Rhinocerebral Mucormycosis with Orosinusal Involvement: Diagnostic and Surgical Treatment Guidelines. Endocr. Metab. Immune Disord. Drug Targets 2016, 16, 264–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hald, M.; Arendrup, M.C.; Svejgaard, E.L.; Lindskov, R.; Foged, E.K.; Saunte, D.M.; Danish Society of Dermatology. Evidence-based Danish guidelines for the treatment of Malassezia-related skin diseases. Acta Derm. Venereol. 2015, 95, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinz, W.J.; Buchheidt, D.; Christopeit, M.; von Lilienfeld-Toal, M.; Cornely, O.A.; Einsele, H.; Karthaus, M.; Link, H.; Mahlberg, R.; Neumann, S.; et al. Diagnosis and empirical treatment of fever of unknown origin (FUO) in adult neutropenic patients: Guidelines of the Infectious Diseases Working Party (AGIHO) of the German Society of Hematology and Medical Oncology (DGHO). Ann. Hematol. 2017, 96, 1775–1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henning, M.A.S.; Hay, R.; Rodriguez-Cerdeira, C.; Szepietowski, J.C.; Piraccini, B.M.; Ferreirós, M.P.; Arabatzis, M.; Sergeev, A.; Nenoff, P.; Kotrekhova, L.; et al. Position statement: Recommendations on the diagnosis and treatment of Malassezia folliculitis. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2023, 37, 1268–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honavar, S.G. Code Mucor: Guidelines for the Diagnosis, Staging and Management of Rhino-Orbito-Cerebral Mucormycosis in the Setting of COVID-19. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 2021, 69, 1361–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurraß, J.; Wiesmüller, G.A. The German guideline on medical clinical diagnostics for indoor mold exposure: Key messages. Allergo J. Int. 2024, 33, 106–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, B.S.; Chen, W.T.; Kung, H.C.; Wu, U.I.; Tang, J.L.; Yao, M.; Chen, Y.C.; Tien, H.F.; Chang, S.C.; Chuang, Y.C.; et al. 2016 guideline strategies for the use of antifungal agents in patients with hematological malignancies or hematopoietic stem cell transplantation recipients in Taiwan. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 2018, 51, 287–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kontoyiannis, D.P.; Lewis, R.E. Treatment Principles for the Management of Mold Infections. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2014, 5, a019737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kulkarni, R.; Misra, U.K.; Meshram, C.; Kochar, D.; Modi, M.; Vishnu, V.Y.; Garg, R.K.; Surya, N. Epidemic of Mucormycosis in COVID-19 Pandemic: A Position Paper. Ann. Indian Acad. Neurol. 2022, 25, 7–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kung, H.C.; Huang, P.Y.; Chen, W.T.; Ko, B.S.; Chen, Y.C.; Chang, S.C.; Chuang, Y.C.; Infectious Diseases Society of Taiwan; Medical Foundation in Memory of Dr. Deh-Lin Cheng; Foundation of Professor Wei-Chuan Hsieh for Infectious Diseases Research and Education; et al. 2016 guidelines for the use of antifungal agents in patients with invasive fungal diseases in Taiwan. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 2018, 51, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leroux, S.; Ullmann, A.J. Management and diagnostic guidelines for fungal diseases in infectious diseases and clinical microbiology: Critical appraisal. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2013, 19, 1115–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limper, A.H.; Knox, K.S.; Sarosi, G.A.; Ampel, N.M.; Bennett, J.E.; Catanzaro, A.; Davies, S.F.; Dismukes, W.E.; Hage, C.A.; Marr, K.A.; et al. An official American Thoracic Society statement: Treatment of fungal infections in adult pulmonary and critical care patients. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2011, 183, 96–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, N.; Bajwa, S.J.S.; Joshi, M.; Mehdiratta, L.; Kurdi, M. Second wave of COVID-19 pandemic and the surge of mucormycosis: Lessons learnt and future preparedness: Indian Society of Anaesthesiologists (ISA National) Advisory and Position Statement. Indian J. Anaesth. 2021, 65, 427–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maschmeyer, G.; Carratalà, J.; Buchheidt, D.; Hamprecht, A.; Heussel, C.P.; Kahl, C.; Lorenz, J.; Neumann, S.; Rieger, C.; Ruhnke, M.; et al. Diagnosis and antimicrobial therapy of lung infiltrates in febrile neutropenic patients (allogeneic SCT excluded): Updated guidelines of the Infectious Diseases Working Party (AGIHO) of the German Society of Hematology and Medical Oncology (DGHO). Ann. Oncol. 2015, 26, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendling, W.; Brasch, J.; Cornely, O.A.; Effendy, I.; Friese, K.; Ginter-Hanselmayer, G.; Hof, H.; Mayser, P.; Mylonas, I.; Ruhnke, M.; et al. Guideline: Vulvovaginal candidosis (AWMF 015/072), S2k (excluding chronic mucocutaneous candidosis). Mycoses 2015, 58 (Suppl. 1), 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, R.; Assi, M.; AST Infectious Diseases Community of Practice. Endemic fungal infections in solid organ transplant recipients-Guidelines from the American Society of Transplantation Infectious Diseases Community of Practice. Clin. Transplant. 2019, 33, e13553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mochizuki, T.; Tsuboi, R.; Iozumi, K.; Ishizaki, S.; Ushigami, T.; Ogawa, Y.; Kaneko, T.; Kawai, M.; Kitami, Y.; Kusuhara, M.; et al. Guidelines for the management of dermatomycosis (2019). J. Dermatol. 2020, 47, 1343–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthu, V.; Agarwal, R.; Patel, A.; Kathirvel, S.; Abraham, O.C.; Aggarwal, A.N.; Bal, A.; Bhalla, A.S.; Chhajed, P.N.; Chaudhry, D.; et al. Definition, diagnosis, and management of COVID-19-associated pulmonary mucormycosis: Delphi consensus statement from the Fungal Infection Study Forum and Academy of Pulmonary Sciences, India. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2022, 22, e240–e253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nenoff, P.; Reinel, D.; Mayser, P.; Abeck, D.; Bezold, G.; Bosshard, P.P.; Brasch, J.; Daeschlein, G.; Effendy, I.; Ginter-Hanselmayer, G.; et al. S1 Guideline onychomycosis. J. Dtsch. Dermatol. Ges. 2023, 21, 678–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roland, L.T.; Humphreys, I.M.; Le, C.H.; Babik, J.M.; Bailey, C.E.; Ediriwickrema, L.S.; Fung, M.; Lieberman, J.A.; Magliocca, K.R.; Nam, H.H.; et al. Diagnosis, Prognosticators, and Management of Acute Invasive Fungal Rhinosinusitis: Multidisciplinary Consensus Statement and Evidence-Based Review with Recommendations. Int. Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2023, 13, 1615–1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudramurthy, S.M.; Hoenigl, M.; Meis, J.F.; Cornely, O.A.; Muthu, V.; Gangneux, J.P.; Perfect, J.; Chakrabarti, A.; ECMM and ISHAM. ECMM/ISHAM recommendations for clinical management of COVID-19 associated mucormycosis in low- and middle-income countries. Mycoses 2021, 64, 1028–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruhnke, M.; Cornely, O.A.; Schmidt-Hieber, M.; Alakel, N.; Boell, B.; Buchheidt, D.; Christopeit, M.; Hasenkamp, J.; Heinz, W.J.; Hentrich, M.; et al. Treatment of invasive fungal diseases in cancer patients-Revised 2019 Recommendations of the Infectious Diseases Working Party (AGIHO) of the German Society of Hematology and Oncology (DGHO). Mycoses 2020, 63, 653–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Camps, I.; Aguado, J.M.; Almirante, B.; Bouza, E.; Ferrer-Barbera, C.F.; Len, O.; Lopez-Cerero, L.; Rodríguez-Tudela, J.L.; Ruiz, M.; Solé, A.; et al. Guidelines for the prevention of invasive mould diseases caused by filamentous fungi by the Spanish Society of Infectious Diseases and Clinical Microbiology (SEIMC). Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2011, 17 (Suppl. 2), 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoham, S.; Dominguez, E.A.; AST Infectious Diseases Community of Practice. Emerging fungal infections in solid organ transplant recipients: Guidelines of the American Society of Transplantation Infectious Diseases Community of Practice. Clin. Transplant. 2019, 33, e13525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.; Huprikar, S.; Burdette, S.D.; Morris, M.I.; Blair, J.E.; Wheat, L.J.; American Society of Transplantation; Infectious Diseases Community of Practice; Donor-Derived Fungal Infection Working Group. Donor-derived fungal infections in organ transplant recipients: Guidelines of the American Society of Transplantation, infectious diseases community of practice. Am. J. Transplant. 2012, 12, 2414–2428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skiada, A.; Lanternier, F.; Groll, A.H.; Pagano, L.; Zimmerli, S.; Herbrecht, R.; Lortholary, O.; Petrikkos, G.L.; European Conference on Infections in Leukemia. Diagnosis and treatment of mucormycosis in patients with hematological malignancies: Guidelines from the 3rd European Conference on Infections in Leukemia (ECIL 3). Haematologica 2013, 98, 492–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, G.R., 3rd; Le, T.; Chindamporn, A.; Kauffman, C.A.; Alastruey-Izquierdo, A.; Ampel, N.M.; Andes, D.R.; Armstrong-James, D.; Ayanlowo, O.; Baddley, J.W.; et al. Global guideline for the diagnosis and management of the endemic mycoses: An initiative of the European Confederation of Medical Mycology in cooperation with the International Society for Human and Animal Mycology. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2021, 21, e364–e374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tissot, F.; Agrawal, S.; Pagano, L.; Petrikkos, G.; Groll, A.H.; Skiada, A.; Lass-Flörl, C.; Calandra, T.; Viscoli, C.; Herbrecht, R. ECIL-6 guidelines for the treatment of invasive candidiasis, aspergillosis and mucormycosis in leukemia and hematopoietic stem cell transplant patients. Haematologica 2017, 102, 433–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tortorano, A.M.; Richardson, M.; Roilides, E.; van Diepeningen, A.; Caira, M.; Munoz, P.; Johnson, E.; Meletiadis, J.; Pana, Z.D.; Lackner, M.; et al. ESCMID and ECMM joint guidelines on diagnosis and management of hyalohyphomycosis: Fusarium spp., Scedosporium spp. and others. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2014, 20 (Suppl. 3), 27–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, H.Y.; Chang, P.H.; Huang, Y.S.; Tsai, C.S.; Chen, K.Y.; Lin, I.F.; Hsih, W.H.; Tsai, W.L.; Chen, J.A.; Yang, T.L.; et al. Recommendations and guidelines for the diagnosis and management of Coronavirus Disease-19 (COVID-19) associated bacterial and fungal infections in Taiwan. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 2023, 56, 207–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lau, A.F. Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption Ionization Time-of-Flight for Fungal Identification. Clin. Lab. Med. 2021, 41, 267–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arastehfar, A.; Wickes, B.L.; Ilkit, M.; Pincus, D.H.; Daneshnia, F.; Pan, W.; Fang, W.; Boekhout, T. Identification of Mycoses in Developing Countries. J. Fungi 2019, 5, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoenigl, M.; Gangneux, J.; Segal, E.; Alanio, A.; Chakrabarti, A.; Chen, S.C.; Govender, N.; Hagen, F.; Klimko, N.; Meis, J.F.; et al. Global guidelines and initiatives from the European Confederation of Medical Mycology to improve patient care and research worldwide: New leadership is about working together. Mycoses 2018, 61, 885–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamoth, F.; Lewis, R.E.; Kontoyiannis, D.P. Role and Interpretation of Antifungal Susceptibility Testing for the Management of Invasive Fungal Infections. J. Fungi 2020, 7, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egge, S.L.; Wurster, S.; Cho, S.-Y.; Jiang, Y.; Axell-House, D.B.; Miller, W.R.; Kontoyiannis, D.P. Co-Occurrence of Gram-Negative Rods in Patients with Hematologic Malignancy and Sinopulmonary Mucormycosis. J. Fungi 2024, 10, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chitasombat, M.N.; Kofteridis, D.P.; Jiang, Y.; Tarrand, J.; Lewis, R.E.; Kontoyiannis, D.P. Rare opportunistic (non-Candida, non-Cryptococcus) yeast bloodstream infections in patients with cancer. J. Infect. 2012, 64, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kontoyiannis, D.P.; Selleslag, D.; Mullane, K.; Cornely, O.A.; Hope, W.; Lortholary, O.; Croos-Dabrera, R.; Lademacher, C.; Engelhardt, M.; Patterson, T.F. Impact of unresolved neutropenia in patients with neutropenia and invasive aspergillosis: A post hoc analysis of the SECURE trial. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2018, 73, 757–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuo, T.; Wurster, S.; Jiang, Y.; Sasaki, K.; Tarrand, J.; Lewis, R.E.; Kontoyiannis, D.P. Invasive fusariosis in patients with leukaemia in the era of mould-active azoles: Increasing incidence, frequent breakthrough infections and lack of improved outcomes. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2024, 79, 297–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nucci, M.; Jenks, J.; Thompson, G.R., III; Hoenigl, M.; Dos Santos, M.C.; Forghieri, F.; Rico, J.C.; Bonuomo, V.; López-Soria, L.; Lass-Flörl, C.; et al. Do high MICs predict the outcome in invasive fusariosis? J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2021, 76, 1063–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamoth, F.; Lewis, R.E.; Kontoyiannis, D.P. Investigational Antifungal Agents for Invasive Mycoses: A Clinical Perspective. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2022, 75, 534–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornely, O.A.; Koehler, P.; Arenz, D.; Mellinghoff, S.C. EQUAL Aspergillosis Score 2018: An ECMM score derived from current guidelines to measure QUALity of the clinical management of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis. Mycoses 2018, 61, 833–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellinghoff, S.C.; Hoenigl, M.; Koehler, P.; Kumar, A.; Lagrou, K.; Lass-Flörl, C.; Meis, J.F.; Menon, V.; Rautemaa-Richardson, R.; Cornely, O.A. EQUAL Candida Score: An ECMM score derived from current guidelines to measure QUAlity of Clinical Candidaemia Management. Mycoses 2018, 61, 326–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sprute, R.; Bethe, U.; Chen, S.C.-A.; Cornely, O.A. EQUAL Trichosporon Score 2022: An ECMM score to measure QUALity of the clinical management of invasive Trichosporon infections. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2022, 77, 1779–1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shiferaw, K.B.; Roloff, M.; Balaur, I.; Welter, D.; Waltemath, D.; Zeleke, A.A. Guidelines and standard frameworks for artificial intelligence in medicine: A systematic review. JAMIA Open 2025, 8, ooae155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teh, B.W.; Mikulska, M.; Averbuch, D.; de la Camara, R.; Hirsch, H.H.; Akova, M.; Ostrosky-Zeichner, L.; Baddley, J.W.; Tan, B.H.; Mularoni, A.; et al. Consensus position statement on advancing the standardised reporting of infection events in immunocompromised patients. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2024, 24, e59–e68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).