Abstract

The treatment of azole-resistant Trichophyton indotineae poses a significant challenge for clinicians worldwide. Resistance mechanisms include amino acid substitutions in the sterol 14-α demethylase gene Erg11B, as well as overexpression of Erg11B. Additionally, efflux mechanisms mediated by fungal transporter proteins contribute to antifungal resistance. Therefore, the inhibition of fungal efflux transporters using known inhibitors could be a promising strategy to prevent treatment failure. The inhibitory effects of itraconazole in combination with various efflux pump inhibitors were evaluated. Co-treatment with quinine hydrochloride and itraconazole did not lead to a significant reduction in the inhibitory concentration (IC) values in T. indotineae isolates. In contrast, ritonavir lowered IC values by approximately 50% without affecting fungal growth when applied as monotherapy. The most pronounced effect was observed with sertraline, which demonstrated intrinsic antifungal activity at higher concentrations. When combined with itraconazole, sertraline reduced IC values to below 10% in both susceptible and resistant strains, enhancing itraconazole efficacy markedly. The increasing prevalence of antifungal resistance is a growing global health concern. These findings suggest that sertraline holds considerable potential as an adjunctive therapy for the treatment of dermatomycoses.

1. Introduction

Recalcitrant dermatomycoses have emerged as a growing public health problem and continue to pose a challenge for both the diagnosis and treatment of affected patients reviewed in [1]. In the past decade, the number of resistant Trichophyton isolates has markedly increased, necessitating the expansion of diagnostic protocols and the adaption of treatment strategies [2,3,4]. One major contributor to the rise in resistant isolates is the emergence of a novel genotype, designated as ITS type VIII within the Trichophyton mentagrophytes/interdigitale complex. These isolates have been associated with a widespread epidemic of recalcitrant dermatomycosis in India [5,6,7,8]. A high proportion of these isolates exhibited terbinafine resistance, predominantly due to point mutations that alter the amino acid sequence of the squalene epoxidase gene Erg1 [5,6,7,9]. Phylogenetic analyses based on whole-genome sequencing revealed that these isolates form a basal lineage within the T. mentagrophytes/interdigitale complex [10]. Consequently, a new species designation, Trichophyton indotineae, was recently proposed [11,12]. The absence of mating compatibility with strains of the opposite mating type supported the classification of T. indotineae as a distinct species [11,12]. In addition to terbinafine resistance, several T. indotineae isolates also displayed reduced susceptibility to itraconazole and voriconazole [5,9,13]. Azoles target the sterol 14-α demethylases, which belong to the cytochrome p450 superfamily (CYP51), referred to as Erg11 following the Candida nomenclature. Two Erg11 paralogs have been identified in T. indotineae [14]. Altered amino acid sequences associated with azole resistance have been found exclusively in the Erg11B gene of T. indotineae [14,15,16]. Genomic analyses further revealed that Erg11B is duplicated in several strains, resulting in two distinct types of genomic amplification [15,17]. Type I includes the tandem amplification of a 2.4 KB fragment of Erg11B [15], whereas type II encompasses the amplification of a 7.4 KB fragment of Erg11B and neighboring genes [17]. Both amplification types lead to Erg11B overexpression, which has been associated with reduced azole susceptibility [15,17]. Erg11B overexpression was, for instance, confirmed for the azole-resistant T. indotineae isolate UKJ 476/21 [18], which belongs to the type II amplification group [19]. Efflux-mediated antifungal resistance also contributes to treatment failure. The overexpression of the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter with homology to the multidrug resistance (MDR) transporter has been described, initially for Trichophyton rubrum MDR3 [20]. MDR3 overexpression was later also detected in the T. indotineae strains TIMM20118 and TIMM20119 [15]. However, itraconazole resistance can occur independently of MDR3 expression; Erg11B overexpression alone is sufficient to confer resistance [15]. Interestingly, exposure to fluconazole induced MDR3 expression in azole-susceptible T. indotineae strains [18].

Antifungal resistance is not always attributable to genetic alterations in drug target genes. For instance, terbinafine resistance has been observed in some T. mentagrophytes strains that retained wild-type Erg1 sequences [21]. Similarly, treatment failure in terbinafine-treated T. indotineae infections occurred despite isolates carrying wild-type Erg1 genes [22]. In the case of azole resistance in T. rubrum, mutations in Erg11B were only detected in a subset of the resistant isolates [19,23]. Therefore, molecular diagnostics targeting known resistance genes should be complemented by antifungal susceptibility assays to ensure accurate resistance profiling. Several standardized antifungal susceptibility tests utilizing broth microdilution protocols have been developed by the EUCAST or CLSI committees [24,25,26]. In addition, simplified plate-based assays have been proposed to reduce time and resource demands [27]. Nevertheless, EUCAST or CLSI protocols remain the gold standard due to their higher accuracy and reproducibility. These assays specify standardized parameters such as inoculum size, spore concentration, incubation temperature, and a two-fold (1:2) serial dilution range for antifungal agents [24,25,26]. Readouts can be assessed visually or via a spectrophotometer [24,25,26]. Microplate laser nephelometry (MLN) provides an automated method for monitoring fungal growth dynamics during antifungal susceptibility testing. The method has been validated for multiple fungal species [28], including T. indotineae [14] and T. quinckeanum [29]. EUCAST and CLSI protocols have been adapted for use with MLN to evaluate the influence of media composition, incubation temperature, and spore concentration for inoculation on itraconazole inhibitory concentrations (ICs) [19]. An optimized MLN protocol was subsequently applied to analyze the effects of co-treatment with potential efflux pump inhibitors, assessing synergistic interactions with itraconazole.

Pharmaceuticals were based on their known activity against human ABC transporters as well as their reported antifungal properties. Quinine, derived from the bark of the Cinchona tree, is classified as a first-generation inhibitor of the human MDR1 transporter [30]. Ritonavir and sertraline are both substrates of the human transporter P-gp [30]. All compounds have also been shown to exhibit antifungal activity, which may be linked to analogous effects on fungal efflux transporters. Quinine has been reported to inhibit yeast-to-hyphae morphogenesis and biofilm formation in Candida albicans [31]. Ritonavir demonstrated antifungal activity against Histoplasma capsulatum [32] and Candida auris [33]. While ritonavir alone was able to sufficiently repress fungal growth in H. capsulatum [32], it only displayed antifungal activity against Candida auris when combined with azoles [33]. Among these compounds, sertraline has been most extensively studied for its antifungal properties. Clinical evidence demonstrated that patients suffering from recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis were successfully treated with oral sertraline at 50 mg over 5–8 menstrual cycles [34]. MIC99 values ranging from 3 to 29 µg/mL were reported for C. albicans, C. glabrata, and C. parapsilosis isolates causative for the infection [34]. Other isolates of C. albicans and C. glabrata exhibited lower susceptibility against sertraline, with MIC values between 32 and 128 µg/mL [35]. For these less susceptible strains, synergistic effects were observed when sertraline was combined with essential oils from Cinnamomum verum, resulting in an approximate 90% MIC reduction for both compounds [35]. In vitro studies further showed that treatment with sertraline or fluoxetine reduced biofilm formation of C. krusei and C. parapsilosis [36]. Clinical isolates of Cryptococcus neoformans displayed in vitro MIC90 values of 2–6 µg/mL for sertraline, with additional synergistic effects observed when combined with fluconazole [37]. Moreover, sertraline exhibited specific activity against cryptococcal fungicide-tolerant persister cells [38]. The therapeutic potential of sertraline for life-threatening fungal infections has also stimulated the research of sertraline derivatives targeting ergosterol biosynthesis [39]. The fungicidal properties of sertraline were further demonstrated in Trichosporon asahii, a yeast belonging to the basidiomycota, with MIC90 values of 8 µg/mL [40]. In Coccidioides immitis, MIC values of 4–8 µg/mL were recorded, along with synergistic interactions when combined with fluconazole [41]. Finally, synergistic effects of sertraline with caspofungin have been proposed as a novel treatment approach for Trichophyton rubrum infections, particularly in cases refractory to standard antifungals [42].

Although T. indotineae infections are not life-threatening, they frequently affect large areas of the body, resulting in tinea corporis and tinea cruris. The majority of patients are young, otherwise healthy male adults. In accordance, the infection has severe consequences for social life, sports activities, and personal relationships. Treatment is increasingly challenging due to the high prevalence of terbinafine-resistant isolates. Moreover, a considerable proportion of isolates display multidrug resistance, involving terbinafine as well as several azoles. The primary goal of this study was to identify human-approved pharmaceuticals with intrinsic antifungal activity that could be repurposed in combination with first-line antifungals. Such combination strategies may provide novel therapeutic options and help to overcome current treatment failures in resistant T. indotineae infections.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Strains and Growth Conditions

Strains were obtained from routine cases at Jena University Hospital (UKJ) or from a previous study that collected strains from all parts of India [9]. Several strains were sent out to other groups and used for genomic analyses as listed in Table S1 [15,17]. Strains were pre-cultivated for three to eight weeks on Dermasel agar (Thermoscientific, Wesel, Germany) for MLN analysis. SG was prepared using Sabouraud-2% w/v glucose bouillon (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) and used for liquid growth.

2.2. Type II and I Specific PCR, qPCR, and DNA Sequencing

For strain verification, the ITS region and squalene epoxidase gene Erg1 were sequenced as described previously [8,9]. The sterol 14-α demethylase gene Erg11B was sequenced as described previously [14]. PCRs for type I or type II specific fragments were amplified as previously described [17,19]. Fragments were separated using agarose gel electrophoresis. The determination of Erg11B genomic copy numbers was performed with qPCR conditions as described for cDNA analysis [18]. Primers and calculations were performed as previously described [19]. CT values were normalized using UKJ 1676/17 as Erg11B single-copy control, as previously described [17]. The fold change was calculated using the 2−ΔΔCT method [43]. The algorithm was corrected for primer efficiency as described [44]. Two biological replicates and two technical replicates were determined with qPCR.

2.3. Medical Stock Preparations and Concentration Ranges

Itraconazole was obtained from Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA, and solved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, Carl Roth, Karlsruhe, Germany). The concentration was determined as described using a spectrophotometer [45]. The stock concentrations ranged between 0.5 and 1 mg/mL. Quinine hydrochloride (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) was dissolved in H2O for stocks of 0.4 mg/mL and sterilized using a sterile filter with a pore size of 0.2 µm. Ritonavir (Sigma Aldrich) was dissolved in 99% ethanol p.A. with a stock concentration of 7,21 mg/mL. Stocks were diluted to reach identical ethanol concentrations in MLN assays. MLN assays with ritonavir showed a final concentration of 0.5% v/v ethanol. Sertraline (Sigma Aldrich) was solved in DMSO as a stock of 20 mg/mL. Further dilutions were performed to keep the DMSO concentration constant. The final DMSO concentration of 0.25% v/v was used in MLN assays. Itraconazole in the range of 0.125 µg/mL up to 0.001 µg/mL was used for strains harboring Erg11B type II and I genomic amplifications. For azole-sensitive strains, the range starts from 0.03 µg/mL and ends at 0.0002 µg/mL.

2.4. Microplate Laser Nephelometry (MLN) Assays

MLN conditions were as previously described [29]. The conditions were adapted to the CLSI protocol [26]. The spore suspensions were adjusted to final concentrations of 3 × 103 CFU/mL, and the growth temperature was set to 34 °C. Medium was changed into SG to enhance growth conditions as described previously [19]. For the minimization of physiological differences dependent on pre-cultivation or the viability of counted spores, strains were treated exclusively with itraconazole in every assay. The controls were used for normalization, and the obtained IC50 values were set as one. Therefore, the relation was determined between single-treated and co-medicated assays. For assays using ritonavir with the solvent ethanol, the effects of ethanol in combination with itraconazole were always determined. Growth controls were obtained from untreated cells, solvent-treated cells, and cells treated exclusively with co-medicals. Growth control of untreated cells was used for normalization and to determine the relation between control and other treatments depending on the solvent or co-medicals. Two biological and two technical replicates were obtained. The plates were measured every hour for a 120 h period.

2.5. Graphical Image Preparation, Data Performance, and Statistical Analysis

Graphical images were prepared using the OriginPro 2025 (Origin-Lab Corporation, Northampton, MA, USA) software. IC50 values were performed for non-linear curves using the logistic option with the Levenberg–Marquardt algorithm of OriginPro2025 as previously described [19]. Statistical analysis was performed with IBM SPSS Statistics 30. A pairwise Mann–Whitney U test was used to determine the asymptotic significance values.

3. Results

Several T. indotineae strains included in this study have been previously analyzed and were well-characterized with respect to their antifungal resistance profile [9,14,15,17,18]. For many of these strains, whole-genome sequence data are available [15,17] (see Table S1). With regard to itraconazole susceptibility, eight of the strains exhibited resistant phenotypes, while four strains were classified as susceptible. Detailed characteristics of all strains are summarized in Table 1. All strains exhibiting genomic amplification of Erg11B (Table 1) demonstrated itraconazole resistance. Strains harboring Erg11B double mutations without genomic amplification (Table 1) displayed an increased tolerance to sertaconazole nitrate [14]. Strains carrying the Erg1 Phe397Leu substitution were highly resistant to terbinafine, whereas the Erg1 Ala448Thr mutation was not associated with high terbinafine resistance but was found to co-occur with Erg11B type II amplification [17]. Although strains UKJ1067/21 and UKJ1985/21 retained wild-type Erg1 sequences, they were isolated from a patient who experienced treatment failure with terbinafine [22].

Table 1.

Summary of the Trichophyton indotineae strains included in this study and their characteristic features.

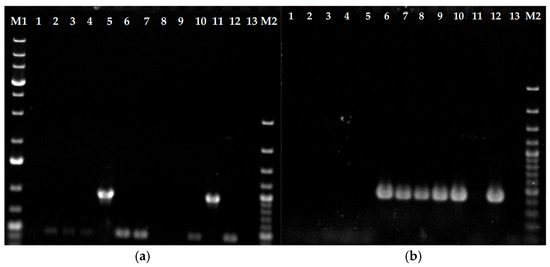

3.1. Erg11B Copy Number Determination and Type II and I Specific PCR to Verify Strain Genotypes

For verification of the genotype of T. indotineae strains, type I- and type II-specific PCR assays were performed according to a previously described protocol [17]. All strains assigned a TIMM collection number (see Table 1) displayed amplification patterns consistent with earlier reports [17] (Figure 1). However, a discrepancy was identified for strain UKJ1708/17, which displayed a type II amplification pattern, contrary to its previous classification as type I [17] (Figure 1b, lane 6). Type I amplifications were confirmed for strains UKJ1687/17 and UKJ421/18, both showing the expected 955 bp fragment (Figure 1a, lanes 5 and 11). Strain UKJ476/21 exhibited a type II-specific amplification fragment of 434 bp (Figure 1b, lane 8), which was accompanied by Erg11B overexpression, as previously described [18]. Type II-specific fragments were also detected in strains UKJ392/18, UKJ334/19, UKJ336/19, and UKJ893/19, confirming earlier results [17] (Figure 1b, lanes 7, 9, 10, and 12). UKJ262/21 displayed the same amplification pattern as UKJ1676/17 (Figure 1, lanes 1 and 2). Notably, this strain exhibited susceptibility to itraconazole, voriconazole, and sertaconazole nitrate [14].

Figure 1.

Erg11B type II (b) and I (a) genomic amplification-specific PCR. Genomic DNA from itraconazole-sensitive strains UKJ 1676/17, UKJ 262/21, UKJ 1067/21, and UKJ 1985/21 was loaded in lanes 1 to 4 of panels (a) and (b), respectively. PCR results for the itraconazole-resistant strains UKJ 1687/17, UKJ 1708/17, UKJ 392/18, UKJ 476/21, UKJ 334/19, UKJ 336/19, UKJ 421/18, and UKJ 893/19 are presented in the same order in lanes 5 to 12. Negative controls were included in lane 13. Molecular size markers were loaded in lanes M1 and M2: the 1 KB ladder Plus (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Vilnius, Lithuania) was used in lane M1 and the 100 bp Plus ladder (Thermo Fisher Scientific) in lane M2. Marker bands with three-fold DNA concentrations were visible at 0.5 KB and 1 KB for the 100 bp ladder Plus and at 0.5 KB, 1.5 KB, and 5 KB for 1 KB ladder Plus.

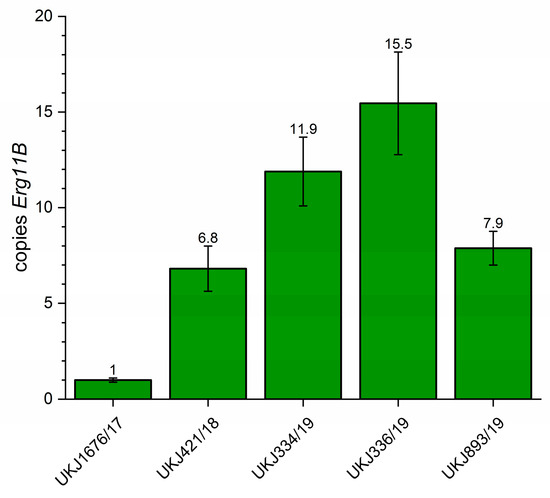

For the determination of the genomic copy number of Erg11B in T. indotineae strains exhibiting type I and II amplification patterns, quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) was performed according to previously established protocols [17,19]. In type I strains, qPCR revealed five to seven Erg11B copies arranged in tandem repeats, consistent with results obtained from whole-genome data [17]. In contrast, qPCR-derived copy numbers for type II strains deviated from genome-based estimates [17], and notable variation was observed among individual type II isolates. The results presented in Figure 2 corroborate prior findings [17,19], confirming increased variability in Erg11B copy numbers within type II strains. Specifically, strain UKJ334/19 exhibited up to 12 copies, while UKJ336/19 showed a maximum of 15 copies (Figure 2), compared to typical copy numbers of 7–8 in type II strains [17,19]. Previously reported copy numbers for TIMM20120 (UKJ334/19: 9–11 copies) and TIMM20121 (UKJ336/19: 14 copies) [17] supported the correct designation of UKJ strains with TIMM isolates. Notably, UKJ 336/19 harbors a double mutation in Erg1 (see Table 1), which correlates with high-level resistance to terbinafine.

Figure 2.

Determination of Erg11B copy number using quantitative real-time PCR. Strain UKJ1676/17, known to carry a single Erg11B copy, was used as the reference control. qPCR mean values obtained from this strain served as the normalization baseline for determining relative Erg11B copy numbers in other strains. The numbers displayed above each column represent the mean genomic Erg11B copy number for the respective strain. Error bars indicate variation in technical and biological replicates.

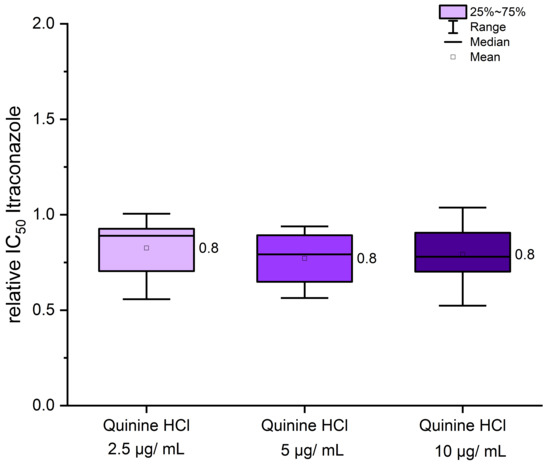

3.2. Treatment of Itraconazole in Combination with Quinine Hydrochloride Showed a Weak Effect on Inhibitory Concentrations of 50% (IC50) of T. indotineae Strains

Quinine hydrochloride is an inexpensive and widely available pharmaceutical compound that may offer potential in settings with limited healthcare resources. Its high water solubility presents an additional advantage for formulation and topical application. Microplate laser nephelometry (MLN), as previously described [11,19], was employed to determine the IC50 value (half-maximal inhibitory concentration) of itraconazole, both alone and in combination with quinine hydrochloride. Experimental parameters were adapted based on the CLSI protocol M38 [26]. Incubation was conducted at 34 °C, with a final spore titer of 3 × 103 cfu/mL for each strain. Over a total incubation time of 120 h, MLN measurements were taken every hour. Instead of RPMI1640 medium (buffered with MOPS, pH 7.0), Sabouraud glucose (SG) medium containing 2% w/v glucose was used. As demonstrated in previous studies [19], the use of SG medium led to a significant decrease in IC50 values and allowed for better discrimination between azole-resistant or azole-susceptible strains [19]. To detect even small effects, IC50 values for itraconazole alone were always determined as baseline control, thereby minimizing variability due to strain-specific pre-cultivation conditions. In Figure 3, the ratio of IC50 values from itraconazole monotherapy to those from co-treatment with quinine hydrochloride is presented. Effective co-treatment is indicated by a decrease in IC50 values relative to the itraconazole control. Increasing concentrations of quinine hydrochloride beyond a certain threshold achieved no additional effect, and a final concentration of 2.5 µg/mL was sufficient to reduce IC50 values by approximately 20% (Figure 3), from 0.081 µg/mL in the itraconazole monotherapy to around 0.068 µg/mL in the co-treatment of UKJ1708, for example. However, the degree of IC50 reduction varied among strains, as shown in Table S2. Importantly, these strain-specific responses did not correlate with specific resistance genotypes (see Table 1). Notably, certain strains, such as UKJ1676/17, UKJ1708/17, and UKJ 476/21, showed no measurable effect during quinine hydrochloride co-treatment (Table S2). Due to the modest efficacy of quinine hydrochloride, only a subset of strains was tested, and further analyses were limited.

Figure 3.

Co-treatment of itraconazole with quinine hydrochloride resulted in only a modest effect, which appeared to be independent of the strains’ genotypic background. IC50 values from itraconazole monotherapy were used for normalization (set as 1). Relative changes in IC50 values following co-treatment with quinine hydrochloride are presented as fold differences. Mean values are indicated next to the boxplots. A total of eight strains, as listed in Table S2, were included in the analysis.

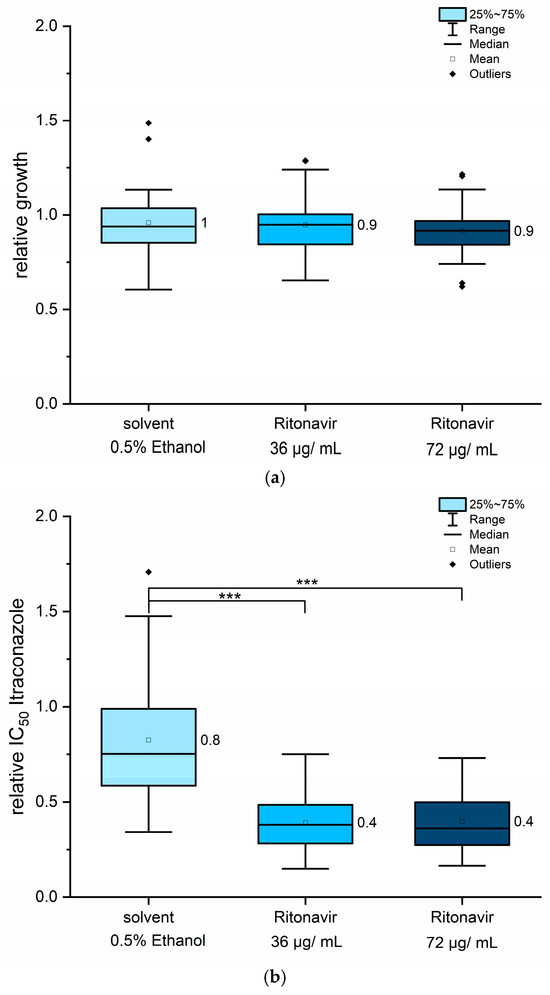

3.3. Co-Treatment with Ritonavir Showed a 50% Reduction in Itraconazole IC50 Values

In contrast to quinine hydrochloride, ritonavir is a hydrophobic compound and was therefore dissolved in ethanol. As ethanol can exert toxic effects on fungal cells, its potential influence on fungal growth was assessed as an additional control in all experiments. The final ethanol concentration was consistently maintained at 0.5% (v/v). The effects of ethanol alone or ritonavir alone (at 36 µg/mL and 72 µg/mL) on fungal growth were evaluated in the absence of itraconazole in each MLN assay for all strains. Neither 0.5% ethanol nor ritonavir in either concentration significantly affected fungal growth (Figure 4a), indicating that ritonavir alone has no intrinsic antifungal properties at the concentrations used. However, in combination with itraconazole, ritonavir led to an approximately 60% reduction in IC50 values of itraconazole (Figure 4b). The effect was observed at both 36 µg/mL and 72 µg/mL ritonavir, with no additional benefit observed at the higher concentration (Figure 4b). Interestingly, the solvent ethanol causes a modest reduction of about 20% in itraconazole IC50 values (Figure 4b), despite having no effect on growth kinetics itself (Figure 4a). This suggests that ethanol may induce physiological changes in fungal cells or influence physicochemical properties of itraconazole, for example, solubility, which influence drug sensitivity. After accounting for the ethanol effect, ritonavir itself appears responsible for approximately 50% of the observed IC50 reduction.

Figure 4.

Ritonavir, when used in combination with itraconazole, reduced IC50 values by up to 50%. The effects of ritonavir on fungal growth are shown in panel (a), while relative IC50 values for itraconazole under co-treatment are presented in panel (b). All 12 strains were included in the analysis. Mean values are displayed next to each column. Statistical analysis was performed using pairwise Mann–Whitney U tests. Asymptotic significance levels (p) are indicated (*** p < 0.001).

The strain-dependent response to ritonavir, as presented in Table 2 and in Table S3, did not correlate with any specific resistance genotype. For several strains, no solvent-associated reduction in IC50 values was observed (Table S3). For example, strains UKJ392/18, UKJ334/19, UKJ262/21, UKJ476/21, and UKJ1067/21 were unaffected by ethanol exposure (Table S3). Doubling the ritonavir concentration produced itraconazole IC50 values similar to those obtained with 36 µg/mL of ritonavir co-treatment, suggesting a saturation effect and indicating that the potentiating activity of ritonavir has an upper limit. IC50 values for itraconazole were derived from the inflection point of the respective logistic dose–response curves and were therefore less influenced by the slope of the curves. Since MIC90 values are more dependent on curve steepness, they are inherently more variable. To reduce the experimental variability, MIC90 values were obtained using identical pre-cultures and were averaged across two technical and two biological replicates. Notably, strain UKJ1708/17 exhibited MIC90 values approximately 28-fold higher than those of the susceptible strain UKJ1676/17 (Table 2). Strains UKJ1676/17 and UKJ1985/21 displayed the lowest MIC90 values and were considered susceptible isolates (Table 2). Interestingly, UKJ 1067/21 showed high MIC90 values, similar to strains with amplified Erg11B gene copies. Strain UKJ262/21 exhibited intermediate values, falling between the sensitive and resistant groups. Strains UKJ1067/21 and UKJ1985/21 were both isolated from the same patient, with the latter being recovered six months later after repeated terbinafine treatments [22]. Calculation of the fractional inhibitory concentration index (FICI) [46,47] was not feasible, because ritonavir alone does not exhibit sufficient antifungal activity. Instead, only the fractional inhibitory concentration (FIC) values for itraconazole were calculated (Table 2). FIC values for itraconazole ranged from 0.21 to 0.83, with most values clustering near 0.5 (Table 2), in agreement with the relative decrease in IC50 values observed (Figure 4b). Growth inhibition by ritonavir alone ranged from negligible to a maximum of 16% (Table 2). In contrast, reductions in MIC values for the combined treatments were consistently greater than the effects of ritonavir alone (Table 2). These findings indicate that co-administration of ritonavir and itraconazole resulted in synergistic interactions.

Table 2.

Synergistic effects of ritonavir. MIC90 values for itraconazole (ITZ) alone were compared to those obtained in combination with 36 µg/mL of ritonavir to form the fractional inhibitory concentration for itraconazole (FIC ITZ). Mean values derived from two technical replicates and two biological replicates are shown, ordered according to the MIC90 values for itraconazole alone.

3.4. Sertraline Showed Antifungal Properties and Synergistic Effects in Combination with Itraconazole

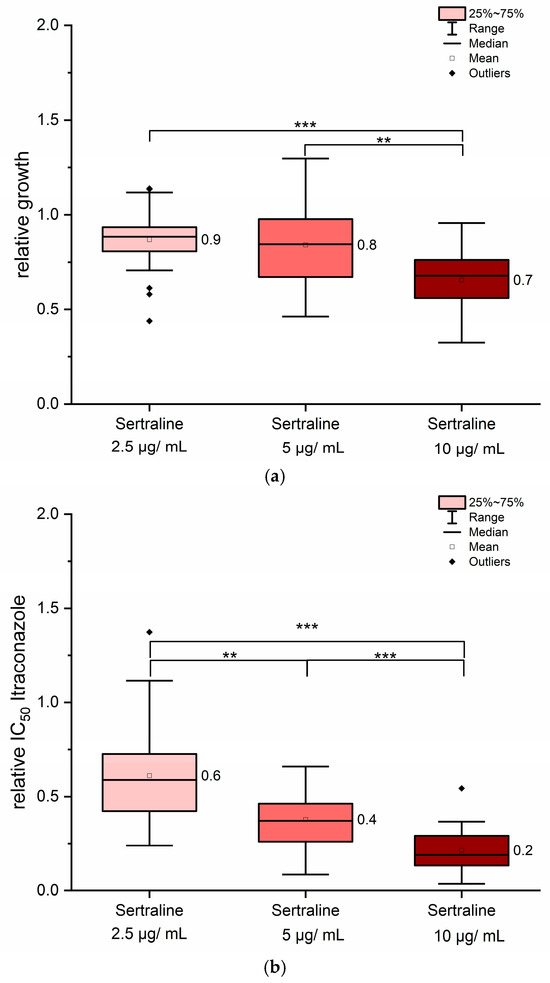

The most promising effects were observed with the combination of sertraline and itraconazole. In contrast to quinine hydrochloride and ritonavir, sertraline exhibited intrinsic antifungal activity, even in the absence of co-administration of itraconazole. To determine an appropriate concentration range, sertraline was evaluated for its standalone antifungal activity. A concentration of 20 µg/mL of sertraline resulted in complete growth inhibition in some strains. The solvent DMSO, used in a final concentration of 0.25% v/v, showed no significant influence on fungal growth. For combination treatments, sertraline concentrations between 2.5 µg/mL and 10 µg/mL were tested. At 10 µg/mL, sertraline alone caused significant growth reduction across nearly all tested strains (Figure 5a) but not below 75% of growth inhibition (Figure 5a). Therefore, MIC90 values of sertraline could be estimated above to be 10 µg/mL. In contrast, 2.5 µg/mL had no significant impact on fungal growth, while 5 µg/mL produced strain-dependent responses, suggesting intermediate sensitivity levels among isolates (Figure 5a). Although the lowest sertraline concentration (2.5 µg/mL) had no measurable antifungal effect on its own, its combination with itraconazole led to about 40% reduction in itraconazole IC50 values (Figure 5b). Doubling the sertraline concentration further reduced itraconazole IC50 values by approximately 60% and the highest sertraline concentration tested (10 µg/mL) yielded reductions of up to 80% (Figure 5b). These findings indicate a synergistic interaction between itraconazole and sertraline, enhancing antifungal efficacy beyond the additive effects of either compound alone.

Figure 5.

Sertraline exerted synergistic effects when combined with itraconazole. As shown in panel (a), sertraline alone inhibited fungal growth in a concentration-dependent manner. The ratio for itraconazole IC50 values in combination with sertraline is presented in panel (b). All 12 strains were included in the analysis. Mean values are indicated next to each column. Statistical significance was assessed using pairwise Mann–Whitney U tests. Asymptotic significance levels (p) are indicated (** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001).

The strains differed in their response to sertraline when co-administered with itraconazole, as summarized in Table S4. Nevertheless, no correlation was observed between specific genotypes and the sertraline-dependent response. Weaker effects of sertraline were noted for strains UKJ1676/17, UKJ1708/17, and UKJ334/17. In contrast, a pronounced sensitivity to sertraline was observed for UKJ392/18, UKJ421/18, UKJ893/19, and UKJ476/21 (Table S4). Interestingly, the greatest variability in strain-specific responses was observed at the highest sertraline concentration (10 µg/mL), with up to a four-fold difference in IC50 values for itraconazole. At the lowest sertraline concentration (2.5 µg/mL), variation between strains was limited to approximately two-fold. In contrast to ritonavir, no saturation effect was detected in the sertraline concentration range tested here; higher sertraline amounts consistently produced greater reductions in itraconazole IC50 values (Figure 5, Table S4). The highest MIC90 values were observed for strain UKJ1708/17, whereas the lowest values were found for UKJ1985/21 and UKJ 1676/17 (Table 2 and Table 3). Therefore, strain UKJ1708/17 exhibited approximately 22-fold higher MIC90 values compared to UKJ1676/17. Growth reduction by sertraline alone (10 µg/mL) ranged from 11% up to 53% across the tested isolates (Table 3). In contrast, reductions in MIC90 values observed for the combination of sertraline with antifungals were consistently much greater than those achieved with sertraline alone. An exception was strain UKJ334/19, for which the percentage reduction was comparable for both conditions (Table 3). Notably, combined antifungal treatment reduced MIC90 values by up to 90%, effectively bridging the gap between the most resistant isolates and the susceptible strains UKJ1676/17 and UKJ1985/21 (Table 3).

Table 3.

Synergistic effect of sertraline. MIC90 values for itraconazole alone were compared with MIC90 values combined with 10 µg/mL of sertraline. Mean values derived from two technical replicates and two biological replicates are shown, ordered according to the MIC90 values for itraconazole alone.

4. Discussion

The MLN-based method, adapted for antifungal susceptibility testing, proved suitable for detecting even subtle effects in fungal responses to the various drugs tested. The inclusion of single treatment controls for each substance in every assay eliminated influences related to pre-cultivation conditions and the physiological state of the isolates, an important requirement for reliably analyzing the impact of co-medicated compounds. While quinine hydrochloride showed only minor effects, both ritonavir and sertraline demonstrated clear synergistic interaction in combination with itraconazole. The decrease in relative IC50 values enabled the direct comparison between strains, regardless of their baseline susceptibility to different antifungal concentrations. Notably, the effects of ritonavir and sertraline were observed across both resistant and sensitive strains. Checkerboard dilution panels, commonly used to determine FICI values, often lack technical replicates and are therefore prone to variability and lower reproducibility [48]. Therefore, the inclusion of both technical and biological replicates in this study was essential, even though the dilution range was limited.

Multiple drug resistance (MDR) is frequently associated with the overexpression of ABC efflux transporters, which significantly impairs the efficacy of pharmaceutical interventions in humans. Quinine is considered a first-generation inhibitor of MDR transporters in humans [30]. Such first-generation inhibitors are often themselves substrates of the respective transporter, and their inhibitory properties were initially observed as off-target side effects [36]. Ritonavir functions as a substrate for the human ABC efflux transporter P-gp (MDR1) and the multidrug resistance-associated protein MRP1 [30]. Its role as a transport inhibitor has been demonstrated in studies investigating the uptake of technetium-labeled mebrofenin in humans [49]. Ritonavir also exhibits intrinsic antifungal activity, with a reported MIC80 of approximately 1 µg/mL (~1.4 mM) against the mycelial form of Histoplasma capsulatum [32]. Furthermore, the combination of ritonavir or saquinavir with itraconazol demonstrated synergistic antifungal effects against H. capsulatum [32]. In contrast, no antifungal activity of ritonavir alone was observed against T. indotineae strains in the present study, even at concentrations as high as 72 µg/mL. Nevertheless, ritonavir did exhibit a saturation effect when combined with itraconazole, with its potentiating effect reaching a plateau at about 50% IC50 reduction. In a recent study, lopinavir and ritonavir, when used alone, did not show antifungal activity against Candida auris strains [33]. However, in combination with various azoles, both demonstrated synergistic effects on the growth inhibition of Candida auris strains [33]. In this study, synergy was observed in nearly all Candida auris strains tested, 100% for lopinavir with itraconazole and 91% for ritonavir with itraconazole [39]. While synergistic interactions between ritonavir and itraconazole were also observed for Trichophyton indotineae strains in the present study, the overall effect was weaker.

In contrast, the combination of itraconazole with sertraline consistently demonstrated the most pronounced reductions in MIC90 values among all tested antifungal combinations in T. indotineae (Table 3). Synergistic interactions were reported when sertraline was combined with azoles against Cryptococcus neoformans [37], Trichosporon asahii [40], and Coccidioides. immitis [41]. Sertraline has also been shown to exhibit antifungal activity against Trichophyton rubrum, with synergistic effects noted in combination with caspofungin [42]. Antifungal susceptibility testing in that study followed the CLSI protocol [26], yielding MICs of 100 µg/mL with SG medium and 25 µg/mL with MOPS-buffered RPMI1640 medium for sertraline alone [42]. Caspofungin is not considered a first-line treatment for dermatomycosis, and MICs of 31–63 µg/mL for T. rubrum, depending on the growth medium, indicate relative low sensitivity [42].

Sertraline has been shown to influence the transcriptional activity of genes associated with the major facilitator superfamily (MFS) transporters and the C8-sterol isomerase involved in the ergosterol biosynthesis pathway [42]. Interestingly, synthetic sertraline derivatives also reduced ergosterol biosynthesis through the inhibition of the Δ5,6 desaturase [39]. The role of transporter expression on antifungal efflux in azole resistance was prominently shown for MDR3 in T. rubrum [20] and T. indotineae [18]. Trichophyton mentagrophytes isolates exhibiting terbinafine resistance in the absence of Erg1 mutations were found to have increased transporter expression [21]. Transcriptome analyses of resistant T. tonsurans isolates further revealed upregulation of several transporter genes in response to antifungal exposure in resistant strains, indicating that efflux regulation is multifactorial and complex [50]. RNA-seq analysis of T. rubrum treated with sertraline elucidated altered expression patterns for several ergosterol biosynthesis genes and ABC transporter genes [51]. Additionally, the ergosterol content of T. rubrum was significantly reduced when treated with sub-inhibitory concentrations of sertraline [51]. These findings and the results of the present study support the hypothesis that sertraline enhances azole efficacy by targeting components of the ergosterol biosynthesis pathway, thereby explaining the consistent synergistic effects observed in combination therapies. Expression analyses demonstrated that T. indotineae upregulated the efflux transporter MDR3 in response to fluconazole or voriconazole, but not to itraconazole, suggesting an impaired sensing mechanism for the latter [18]. A novel itraconazole formulation with improved bioavailability (SUBA-itraconazole) enables dose reduction while enhancing clinical antifungal efficacy [52].

A key limitation of this study is that the observed effects of sertraline were restricted to in vitro conditions, and in vivo studies for validation are required before clinical applications can be considered. Reported serum concentrations of sertraline [53] may be too low to achieve systemic antifungal efficacy, and its suitability for topical administration remains uncertain. Future studies are needed to determine whether sertraline can penetrate the skin sufficiently to support its use in the treatment of dermatomycoses.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that co-treatment with ritonavir or sertraline significantly enhances the antifungal efficacy of itraconazole against Trichophyton indotineae, including azole-resistant strains. The observed reduction in IC50 and MIC90 values supports the interpretation of pharmacological synergy. Together, these findings suggest that the adjunctive use of repurposed drugs such as ritonavir and sertraline may offer a promising strategy to overcome azole resistance in dermatophytes. Further in vivo studies and mechanistic analyses are warranted to validate these results and support clinical translation.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/jof11100698/s1; Table S1: Trichophyton indotineae strains and GenBank Accession Number (Acc. No.) entries; Table S2: Strain specific relative IC50 values for itraconazole after co-treatment with quinine hydrochloride; Table S3: Strain dependent reduction of IC50 values for itraconazole effect of upon co-treatment with ritonavir and ethanol alone as solvent control; Table S4: Strain dependent reduction of IC50 values for itraconazole effect upon co-treatment with sertraline.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.B. and C.W.; methodology, A.G. and A.B.; software, A.G. and A.B.; validation, A.G., A.B., and C.W.; formal analysis, A.G. and A.B.; resources, J.T. and M.F.; data curation, A.G. and A.B.; writing—original draft preparation, A.B. and C.W.; writing—review and editing, A.G., J.T., and M.F.; supervision, C.W.; project administration, J.T. and M.F.; funding acquisition, J.T. and M.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We thank Silke Uhrlaß and Pietro Nenoff for their cooperation in the past and sharing many strains with us used in this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CFU | Colony-forming units |

| DMSO | Dimethyl sulfoxide |

| FICI | Fractional inhibitory concentration index |

| IC | Inhibitory concentration |

| ITZ | Itraconazole |

| MDR | Multiple drug resistance |

| MFS | Major facilitator superfamily |

| MIC | Minimal inhibitory concentration |

| MLN | Microplate laser nephelometry |

| MOPS | 3-(N-morpholino)propane sulfonic acid |

| RPMI | Roswell Park Memorial Institute |

| SG | Sabouraud-glucose medium |

References

- Gupta, A.K.; Talukder, M.; Carviel, J.L.; Cooper, E.A.; Piguet, V. Combatting antifungal resistance: Paradigm shift in the diagnosis and management of onychomycosis and dermatomycosis. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2023, 37, 1706–1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabet, A.; Normand, A.-C.; Brun, S.; Dannaoui, E.; Bachmeyer, C.; Piarroux, R.; Hennequin, C.; Moreno-Sabater, A. Trichophyton indotineae from epidemiology to therapeutic. J. Med. Mycol. 2023, 33, 101383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.K.; Wang, T.; Mann, A.; Ravi, S.P.; Talukder, M.; Lincoln, S.A.; Foreman, H.-C.; Kaplan, B.; Galili, E.; Piguet, V.; et al. Antifungal resistance in dermatophytes—Review of the epidemiology, diagnostic challenges, and treatment strategies for managing Trichophyton indotineae infections. Expert Rev. Anti-Infect. Ther. 2024, 22, 739–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonego, B.; Corio, A.; Mazzoletti, V.; Zerbato, V.; Benini, A.; di Meo, N.; Zalaudek, I.; Stinco, G.; Errichetti, E.; Zelin, E. Trichophyton indotineae, an emerging drug-resistant dermatophyte: A review of the treatment options. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 3558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Masih, A.; Khurana, A.; Singh, P.K.; Gupta, M.; Hagen, F.; Meis, J.F.; Chowdhary, A. High terbinafine resistance in Trichophyton interdigitale isolates in Delhi, India harbouring mutations in the squalene epoxidase gene. Mycoses 2018, 61, 477–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudramurthy, S.M.; Shankarnarayan, S.A.; Dogra, S.; Shaw, D.; Mushtaq, K.; Paul, R.A.; Narang, T.; Chakrabarti, A. Mutation in the squalene epoxidase gene of Trichophyton interdigitale and Trichophyton rubrum associated with allylamine resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2018, 62, e02522-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khurana, A.; Masih, A.; Chowdhary, A.; Sardana, K.; Borker, S.; Gupta, A.; Gautam, R.K.; Sharma, P.K.; Jain, D. Correlation of in vitro susceptibility based on MICs and squalene epoxidase mutations with clinical response to terbinafine in patients with tinea corporis/cruris. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2018, 62, e01038-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nenoff, P.; Verma, S.B.; Vasani, R.; Burmester, A.; Hipler, U.-C.; Wittig, F.; Krüger, M.; Nenoff, K.; Wiegand, C.; Saraswat, A.; et al. The current epidemic of superficial dermatophytosis due to Trichophyton mentagrophytes–a molecular study. Mycoses 2019, 62, 336–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebert, A.; Monod, M.; Salamin, K.; Burmester, A.; Uhrlaß, S.; Wiegand, C.; Hipler, U.-C.; Krüger, C.; Koch, D.; Wittig, F.; et al. Alarming India-wide phenomenon of antifungal resistance in dermatophytes: A multicenter study. Mycoses 2020, 63, 717–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pchelin, I.M.; Azarov, D.V.; Churina, M.A.; Scherbak, S.G.; Apalko, S.V.; Vasilyeva, N.V.; Taraskina, A.E. Species boundaries in the Trichophyton mentagrophytes/T. interdigitale species complex. Med. Mycol. 2019, 57, 781–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kano, R.; Kimura, U.; Kakurai, M.; Hiruma, J.; Kamata, H.; Suga, Y.; Harada, K. Trichophyton indotineae sp. nov.: A new highly terbinafine-resistant anthropophilic dermatophyte species. Mycopathologia 2020, 185, 947–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.; Kong, X.; Ahmed, S.A.; Thakur, R.; Chowdhary, A.; Nenoff, P.; Uhrlaß, S.; Verma, S.B.; Meis, J.F.; Kandemir, H.; et al. Taxonomy of the Trichophyton mentagrophytes/T. interdigitale species complex, harboring the highly virulent, multiresistent genotype T. indotineae. Mycopathologia 2021, 186, 315–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Chandra, U.; Anchan, V.N.; Verma, P.; Tilak, R. Limited effectiveness of four oral antifungal drugs (fluconazole, griseofulvin, itraconazole and terbinafine) in the current epidemic of altered dermatophytosis in India: Results of a randomized pragmatic trial. Br. J. Dermatol. 2020, 183, 840–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burmester, A.; Hipler, U.-C.; Elsner, P.; Wiegand, C. Point mutations in the squalene epoxidase erg1 and sterol 14-α demethylase erg11 gene of T. indotineae isolates indicate that the resistant mutant strains evolved independently. Mycoses 2022, 65, 97–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, T.; Yaguchi, T.; Maeda, M.; Alshahni, M.M.; Salamin, K.; Guenova, E.; Feuermann, M.; Monod, M. Gene amplification of CYP51B: A new mechanism of resistance to azole compounds in Trichophyton indotineae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2022, 66, e0005922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhuiyan, M.S.I.; Verma, S.B.; Illigner, G.-M.; Uhrlaß, S.; Klonowski, E.; Burmester, A.; Noor, T.; Nenoff, P. Trichophyton mentagrophytes ITS genotype VIII/Trichophyton indotineae infection and antifungal resistance in Bangladesh. J. Fungi 2024, 10, 768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, T.; Maeda, M.; Nagai, H.; Salamin, K.; Chang, Y.-T.; Guenova, E.; Feuermann, M.; Monod, M. Two different types of tandem sequences mediate the overexpression of TinCYP51B in azole-resistant Trichophyton indotineae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2023, 67, e00933-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berstecher, N.; Burmester, A.; Gregersen, D.M.; Tittelbach, J.; Wiegand, C. Trichophyton indotineae Erg1Ala448Thr strain expressed constitutively high levels of sterol 14-α demethylase Erg11B mRNA, while transporter MDR3 and Erg11A expression was induced after addition of short chain azoles. J. Fungi 2024, 10, 731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krauße, L.; Burmester, A.; Uhrlaß, S.; Fabri, M.; Nenoff, P.; Tittelbach, J.; Wiegand, C. Significant impact of growth medium on itraconazole susceptibility in azole-resistant versus wild-type Trichophyton indotineae, rubrum, and quinckeanum isolates. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 7090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monod, M.; Feuermann, M.; Salamin, K.; Fratti, M.; Makino, M.; Alshahni, M.M.; Makimura, K.; Yamada, T. Trichophyton rubrum azole resistance mediated by a new ABC transporter, TruMDR3. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2019, 63, e00863-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gnat, S.; Lagowski, D.; Nowakiewicz, A.; Dylag, M.; Osinska, M. Complementary effect of mechanism of multidrug resistance in Trichophyton mentagrophytes isolated from human dermatophytosis of animal origin. Mycoses 2021, 64, 537–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregersen, D.M.; Berstecher, N.; Burmester, A.; Tittelbach, J.; Wiegand, C. Unexpected perseverance in tinea corporis—Special mutations found in Trichophyton indotineae dermatomycosis. JEADV Clin. Pract. 2025, 4, 867–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kano, R.; Kimura, U.; Noguchi, H.; Hiruma, M. Clinical isolate of a multi-antifungal-resistant Trichophyton rubrum. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2022, 66, e02393-21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arendrup, M.C.; Kahlmeter, G.; Guinea, J.; Meletiadis, J. How to: Perform antifungal susceptibility testing of microconidia-forming dermatophytes following the new reference EUCAST method E.Def 11.0, exemplified by Trichophyton. Clin. Microbiol. Inf. 2021, 27, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arendrup, M.C.; Guinea, J.; Meletiadis, J. Twenty years in EUCAST antifungal susceptibility testing: Progress & remaining challenges. Mycopathologia 2024, 189, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CLSI Document M38: Reference Method for Broth Dilution Antifungal Susceptibility Testing of Filamentous Fungi, 3rd ed.; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute: Wayne, PA, USA, 2017.

- Blanchard, G.; Amarov, B.; Fratti, M.; Salamin, K.; Bontems, O.; Chang, Y.-T.; Sabou, A.M.; Künzle, N.; Monod, M.; Guenova, E. Reliable and rapid identification of terbinafine resistance in dermatophytic nail and skin infections. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2023, 37, 2080–2089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fink, S.; Burmester, A.; Hipler, U.-C.; Neumeister, C.; Götz, M.R.; Wiegand, C. Efficacy of antifungal agents against fungal spores: An in vitro study using microplate laser nephelometry and an artificially infected 3D skin model. MicrobiologyOpen 2022, 11, e1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, P.; Burmester, A.; Tittelbach, J.; Wiegand, C. A new genotype of Trichophyton quinckeanum with point mutations in Erg11A encoding sterol 14-α demethylase exhibits increased itraconazole resistance. J. Fungi 2023, 9, 1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.H.; Yu, A.-M. ABC transporters in multidrug resistance and pharmacokinetics, and strategies for drug development. Curr. Phar. Des. 2014, 20, 793–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basrani, S.; Patil, S.; Chougule, S.; Kotalagi, T.; Yankanchi, S.; Karuppayil, S.M.; Jadhav, A.S. Repurposing of quinine as an antifungal antibiotic: Identification of molecular targets in Candida albicans. Folia Microbiol. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brihlante, R.S.N.; Caetano, E.P.; Riello, G.B.; Guedes, G.M.d.M.; Castelo-Branco, D.; Fechine, M.A.B.; de Oliveira, J.S.; de Camargo, Z.P.; de Mesquita, J.R.L.; Monteiro, A.J.; et al. Antiretroviral drugs saquinavir and ritonavir reduce inhibitory concentration values of itraconazole against Histoplasma capsulatum strains in vitro. Braz. J. Infect. Dis. 2016, 20, 155–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salama, E.A.; Eldesouky, H.E.; Elgammal, Y.; Abutaleb, N.S.; Seleem, M.N. Lopinavir and ritonavir act synergistically with azoles against Candida auris in vitro and in a mouse model of disseminated candidiasis. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2023, 62, 106906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lass-Flörl, C.; Dierich, M.P.; Fuchs, D.; Semenitz, E.; Ledochowski, M. Antifungal activity against Candida species of the selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitor, sertraline. Clin. Inf. Dis. 2001, 33, e135–e136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbarossa, A.; Rosato, A.; Carrieri, A.; Fumarola, L.; Tardugno, R.; Corbo, F.; Fracchiolla, G.; Carocci, A. Exploring the antibiofilm effect of sertraline in synergy with Cinnamomum verum Essential Oil to counteract Candida species. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, A.S.; Martinez-de-Oliveira, J.; Donders, G.G.G.; Palmeira-de-Oliveira, R. Anti-Candida activity of antidepressants sertraline and fluoxetine: Effect upon pre-formed biofilms. Med. Microbiol. Immun. 2018, 207, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, B.; Wu, C.; Wang, L.; Sachs, M.S.; Lin, X. The antidepressant sertraline provides a promising therapeutic option for neurotropic cryptococcal infections. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2012, 56, 3758–3766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, W.; Xie, Y.; Chen, Y.; Ding, H.; Ye, L.; Qiu, H.; Li, H.; Zhang, L.; Chen, L.; Tian, X.; et al. Fungicide-tolerant persister formation during cryptococcal pulmonary infection. Cell Host Microbe 2024, 32, 276–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Yun, Z.; Ji, C.; Tu, J.; Yang, W.; Li, J.; Liu, N.; Sheng, C. Discovery of novel sertraline derivatives as potent anti-Cryptococcus agents. J. Med. Chem. 2022, 65, 6541–6554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cong, L.; Liao, Y.; Yang, S.; Yang, R. In vitro antifungal activity of sertraline and synergistic effects in combination with antifungal drugs against planktonic forms and biofilms of clinical Trichosporon asahii isolates. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0167903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, S.; Mortimer, R.B.; Mitchell, M. Sertraline demonstrates fungicidal activity in vitro for Coccidioides immitis. Mycology 2016, 7, 99–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, C.H.L.; Rocha, F.M.G.; Bitencourt, T.A.; Martins, M.P.; Sanches, P.R.; Rossi, A.; Martinez-Rossi, N.M. Synergism between the antidepressant sertraline and caspofungin as an approach to minimize the virulence and resistance in the dermatophyte Trichophyton rubrum. J. Fungi 2022, 8, 815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfaffl, M.W. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001, 29, e45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parikh, S.K.; Patel, A.D.; Dave, J.B.; Sen, D.J. Development and validation of UV spectrophotometric method for estimation of itraconazole bulk drug and pharmaceutical formulation. Int. Drug Dev. Res. 2011, 3, 324–328. [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh, M.H.; Yu, C.M.; Yu, V.L.; Chow, J.W. Synergy accessed by checkerboard, a critical analysis. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 1993, 16, 343–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odds, F.C. Synergy, antagonism, and what the checkerboard puts between them. J. Antimicrob. Chem. 2003, 52, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scorzoni, L.; Sangalli-Leite, F.; Singulani, J.L.; Silva, A.C.A.P.; Costa-Orlandi, C.B.; Fusco-Almeida, A.M.; Mendes-Gianinni, M.J.S. Searching new antifungals: The use of in vitro and in vivo methods for evaluation of natural compounds. J. Microbiol. Meth. 2016, 123, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeifer, N.D.; Goss, S.L.; Swift, B.; Ghibellini, G.; Ivanovic, M.; Heizer, W.D.; Gangarosa, L.M.; Brouwer, K.L.M. Effect of ritonavir on 99mTechnetium-Mebrofenin disposition in humans: A semi-PBPK modeling and in vitro approach to predict transporter-mediated DDIs. CPT Pharmacomet. Syst. Pharmacol. 2013, 2, e20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sammadar, S.; Redhwan, M.A.M.; Eraiah, M.M.; Koneri, R. Clinical isolates of the anthropophilic dermatophyte Trichophyton tonsurans exhibit transcriptional regulation of multidrug efflux transporters that induce antifungal resistance. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2025, 52, 612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rocha, F.M.G.; Rocha, C.H.L.; Martins, M.P.; Sanches, P.R.; Bitencourt, T.A.; Sachs, M.S.; Martinez-Rossi, N.M.; Rossi, A. The antidepressant sertraline affects cell signaling and metabolism in Trichophyton rubrum. J. Fungi 2023, 9, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Vanderwyk, K.A.; Donnelley, M.A.; Thompson, G.R. SUBA-itraconazole in the treatment of systemic fungal infections. Future Microbiol. 2024, 14, 1171–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Guo, Z.; Tan, Y.; Li, L.; Wang, Z.; Wen, Y.; Huang, S.; Shang, D. Population pharmacokinetic approach to guide personalized sertraline treatment in Chinese patients. Heliyon 2024, 10, e25231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).