Abstract

The ascomycete family Nectriaceae includes soil-borne saprobes, plant pathogens and human pathogens, biodegraders, and biocontrol agents for industrial and commercial applications. Cinnamomum camphora is a native tree species that is widely planted in southern China for landscaping purposes. During a routine survey of Eucalyptus diseases in southern China, disease spots were frequently observed on the leaves of Ci. camphora trees planted close to Eucalyptus. The asexual fungal structures on the leaf spots presented morphological characteristics typical of the Nectriaceae. The aim of this study is to identify these fungi and determine their pathogenic effect on Ci. camphora. Of the isolates obtained from 13 sites in the Fujian and Guangdong Provinces, 54 isolates were identified based on the DNA phylogeny of the tef1, tub2, cmdA, and his3 regions and morphological features. Two isolates were identified as Calonectria crousiana, and fifty-two isolates were described as a new genus, including a single species. These fungi were named Recticladiella inexpectata gen. et sp. nov. The identification of the new genus was based on strong DNA base differences in each of the four sequenced gene regions. The conidiophores of this fungus had several avesiculate stipe extensions tapering toward a straight, occasionally slightly curved terminal cell, distinguishing it from other phylogenetically close Nectriaceae genera. The results indicate that R. inexpectata is distributed in wide geographic regions in southern China. Inoculation showed that R. inexpectata and Ca. crousiana caused lesions on the leaves of Ci. camphora seedlings within 6 days of inoculation, indicating that they are pathogenic to native Ci. camphora in China.

1. Introduction

The ascomycete family Nectriaceae Tul. and C. Tul. (Hypocreales Lindau, Hypocreomycetidae O.E. Erikss. and Winka, Sordariomycetes O.E. Erikss. and Winka, and Pezizomycotina O.E. Erikss. and Winka) is characterized by uniloculate ascomata that are white, yellow, and orange-red to purple and associated with phialidic asexual morphs producing amerosporous to phragmosporous conidia [1,2]. Members of the Nectriaceae are found in various environments, and some species are important human or plant pathogens [3]. Lombard et al. [3] resolved most taxonomic discordances within the family of Nectriaceae based on morphological and molecular phylogenetic analyses, and 47 genera were re-evaluated. Based on the most recent results, at least 79 genera within this family were accepted [4,5,6]. The Nectriaceae includes numerous important plant pathogens, such as Fusarium Link and Calonectria De Not. species [7,8,9]. These pathogens are causal agents of fruit rot, leaf blight, leaf spot, stem canker, branch wilt, and root rot in many forestry, agricultural, and horticultural plants across the globe [3,10,11].

Cinnamomum camphora (L.) J. Presl (Lauraceae Juss, Laurales Juss. ex Bercht. and J. Presl) is an evergreen tree species that is widely distributed in subtropical regions, including China, Japan, and northeastern Australia [12,13]. Cinnamomum camphora is native to China and distributed in approximately 14 provinces (autonomous regions), especially in southern, southeastern, and southwestern regions of the country [14,15]. In China, Ci. camphora trees are mainly used for landscaping purposes [16] and as furniture and building materials [17]. Cinnamomum camphora tree oil extracted from these trees is widely used to produce medicine, cosmetics, pesticides, and repellents [18,19].

Research on Nectriaceae fungi in China began in 1982, and the first specimen of this group of fungi was collected in Hangzhou, Zhejiang Province. The fungus Calonectria uredinophila Syd. and P. Syd. was identified as a novel species and recently renamed Nectriopsis uredinophila (Syd.) W.Y. Zhuang and X.M. Zhang [20,21]. To date, 16 genera and over 100 species of Nectriaceae have been identified in China [22]. These fungi have been isolated from agricultural crops, horticultural plants, and forestry plants distributed across the country [4,9,23,24].

Cinnamomum camphora is a common landscaping tree species in China, and research on diseases occurring in these trees has drawn increasing attention. At least 30 diseases associated with Ci. camphora trees have been reported in this country, 22 of which are caused by fungal pathogens [14]. Limited research has been conducted on the diversity and pathogenicity of Nectriaceae fungi in Ci. camphora trees in China. To date, the only reported disease caused by Nectriaceae fungi affecting these trees is stem cankers caused by Fusarium decemcellulare Brick [25]. Recently, during disease surveys on Eucalyptus L’Hér. trees in China, we found a leaf spot disease occurring on Ci. camphora trees planted in nurseries alongside urban–rural roadways and in urban green areas in Fujian and Guangdong Provinces. The asexual structures of the pathogen present morphological characteristics typical of the Nectriaceae. The aim of this study is to identify these fungi based on multi-gene phylogenetic analyses, and combine the morphological characteristics and evaluate their pathogenicity in Ci. camphora.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Disease Symptoms, Sample Collection, and Fungal Isolation

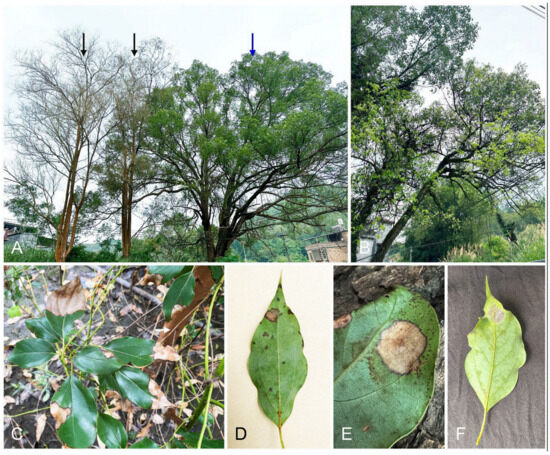

In June and July 2024, we conducted surveys of Eucalyptus tree diseases in Fujian and Guangdong Provinces in southern China. We found heavy defoliation in Ci. camphora trees planted around Eucalyptus trees in nurseries, villages, and urban regions (Figure 1A,B). The typical symptoms included leaf blight and spots (Figure 1C). The disease initially presented as water-soaked and gray lesions on the leaves (Figure 1D). As it rapidly spread, the lesions progressed to a dark color and covered a significant portion of the leaf blade (Figure 1E), ultimately leading to defoliation. White conidiophores with the typical morphological characteristics of the Nectriaceae were observed on the spotted leaves (Figure 1F).

Figure 1.

Disease symptoms in Cinnamomum camphora trees caused by Recticladiella inexpectata. (A) One approximately 50-year-old Ci. camphora tree (indicated by blue arrow) was planted around two approximately 45-year-old Eucalyptus exserta trees (indicated by black arrows). The whole leaves of the E. exserta trees fell after infection for unknown reasons. New leaves appeared after infection by R. inexpectata on the Ci. camphora tree. (B) Young light-yellow leaves appeared on Ci. camphora trees after infection with R. inexpectata. (C) The infected leaves of a 1-year-old Ci. camphora tree were blighted. A Ci. camphora tree was planted close to the E. urophylla hybrid tree (white arrow indicates the stem). (D) Water-soaked, small lesions, and light-brown spots on an infected leaf. (E) Typical leaf spot on a Ci. camphora leaf. (F) White conidiophores appeared on the spot of the infected leaf.

Diseased leaves with typical Nectriaceae conidiophores produced on the leaf spots were collected from 31 diseased Ci. camphora trees at 13 sites in two provinces: five sites in the Zhangzhou Region, one site in the Longyan Region, one site in the Sanming Region in Fujian Province, five sites in the Heyuan Region, and one site in the Meizhou region in the Guangdong Province. These diseased leaf samples were transported to the laboratory for fungal isolation, morphological study, and further molecular research.

Diseased leaves were incubated in moist dishes (diameter of 70 mm and height of 16 mm; tissue paper moistened with sterile water) at room temperature for 1–2 days to induce Nectriaceae sporulation. Fungal isolates with morphological characteristics typical of the Nectriaceae were isolated from diseased leaves. For single-conidium isolation, each conidiophore mass of Nectriaceae produced on the diseased leaves was transferred to 2% (v/v) malt extract agar (MEA) (20 g of malt extract powder (Qingdao Hope Bio-Technology Co., Ltd., Qingdao, Shandong, China) and 20 g of agar powder (Beijing Solarbio Science and Technology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China) per liter of water) with a sterile needle under a stereoscopic microscope (Carl Zeiss Suzhou Co., Ltd., Suzhou, Jiangsu, China). After incubation at 25 °C for 3–4 h, the germinated conidia were individually transferred onto fresh MEA under a stereoscopic microscope and incubated at 25 °C for 7–10 days to obtain single-conidium cultures. One single-conidium culture was obtained from each diseased leaf with white conidiophore masses. All obtained single-conidium cultures were maintained in the Culture Collection (CSFF) at the Forest Pathogen Center (FPC), College of Forestry, Fujan Agricultural and Forestry University (FAFU) in Fuzhou, Fujian Province, China. Representative isolates were also deposited at the China General Microbiological Culture Collection Centre (CGMCC), Beijing, China, and dried cultures with sexual and/or asexual structures in a metabolically inactive state served as dried specimens and were deposited in the Mycological Fungarium of the Institute of Microbiology, Chinese Academy of Sciences (HMAS), Beijing, China.

2.2. DNA Extraction, PCR Amplification, and Sequencing

Total genomic DNA extraction was performed for all Nectriaceae isolates obtained in this study. Each single-conidium isolate was cultivated on 2% (w/v) MEA at 25 °C for 7 days. The mycelia were collected using a sterilized bamboo skewer and transferred to 2 mL Eppendorf tubes. The total genomic DNA of each isolate was extracted following the cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) method described by Van Burik et al. [26]. The extracted DNA was dissolved by adding 30 μL of TE buffer (1 M Tris–HCl and 0.5 M EDTA, pH 8.0), and 2.5 µL of RNase (10 mg/mL) was added to degrade the RNA. The mixture was incubated at 37 °C for 1 h. The DNA concentration of each isolate was measured by using a NanoDrop Lite Plus spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). All DNA samples were diluted to approximately 100 ng/µL by using Water-DEPC Treated Water (Sangon Biotech Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) and stored at −20 °C for further use.

Based on previous studies, partial gene regions, including translation elongation factor 1-alpha (tef1), β-tubulin (tub2), calmodulin (cmdA), and histone H3 (his3), were used as DNA barcodes to distinguish genus and species in Nectriaceae [3,27,28]. Fragments of the tef1, tub2, cmdA, and his3 genes were amplified by using the primer pairs EF1-728F [27]/EF2 [29], T1 [30]/CYLTUB1R [31], CAL-228F [27]/CAL-2Rd [32], and CYLH3F/CYLH3R [31], respectively. The PCR amplification reaction followed the method described by by Liu et al. [28].

By using the same primers used for PCR amplification, the amplification products of all Nectriaceae isolates were sequenced in the forward and reverse directions. Sequence reactions were performed by Sangon Biotech (Shanghai) Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). The tef1, tub2, cmdA, and his3 gene regions were sequenced for all Nectriaceae isolates obtained in this study. All obtained sequences were edited and assembled by using MEGA v. 7.0 software [33] and submitted to GenBank (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov; accessed on 6 December 2024).

2.3. Multigene Phylogenetic Analyses

By using the sequences of the tef1, tub2, cmdA, and his3 regions of all isolates obtained in this study, all Nectriaceae isolates were preliminarily identified by conducting a standard nucleotide BLAST search. To conduct phylogenetic analyses, the sequences of the ex-type strains of closely related species were downloaded from the NCBI database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). The sequences generated in the current study and the sequences downloaded from the NCBI database were aligned by using MAFFT online v. 7 (http://mafft.cbrc.jp/alignment/server; accessed on 3 November 2024) [34] with the iterative refinement method (FFT-NS-i setting). The alignments were edited manually with MEGA v. 7.0 software [33] when necessary. The sequences of each of the tef1, tub2, cmdA, and his3 regions as well as combinations of the four regions, were analyzed.

The maximum likelihood (ML) and Bayesian inference (BI) methods were used for the phylogenetic analyses of the four individual sequences of the tef1, tub2, cmdA, and his3 regions, as well as for a concatenated dataset of all four regions. The ML analyses were performed by using PHYML v. 3.0 [35]. The default GTR substitution matrix was used for the analyses. In PHYML, the maximum number of retained trees was set to 1000, and nodal support was conducted by performing non-parametric bootstrapping with 1000 replicates. The BI analyses were performed by using MrBayes v. 3.2.6 [36] on the CIPRES Science Gateway v. 3.3. Four Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) chains were run from a random starting tree for generations of five million generations, and the trees were sampled every 100th generation. The first 25% of the trees sampled were discarded as burn-in, and the remaining trees were used to determine the posterior probabilities. The sequence data of Stachybotrys chartarum (Ehrenb.) S. Hughes CBS 129.13 were used as an outgroup taxon [3]. The Phylogenetic trees were viewed by using MEGA v. 7.0 [33].

2.4. Morphology

Based on the DNA sequence comparisons, the mycelial plugs of all isolates presented as novel species were transferred onto synthetic nutrient-poor agar (SNA) [37] and incubated at 25 °C to test their conidiophore production. The isolates that produced conidiophores on SNA in 14 days were selected for morphological study. Furthermore, autoclaved carnation leaf pieces were added to the SNA cultures to induce greater sporulation [38]. The asexual structures were mounted in sterile water and examined by using a Zeiss Axio Imager. A2 compound microscope (Carl Zeiss Ltd., Jena, Germany).

To induce sexual structures, the isolates of each novel species were crossed with each other in all possible combinations on minimum salt agar (MSA) [39]. Isolates crossed with themselves served as controls. Sterile toothpicks were placed on the surface of MSA media [39]. All crosses and controls were incubated at 25 °C for 4–8 weeks and were considered successful when the isolate combinations or isolates produced perithecia extruding viable ascospores.

For the isolates selected to represent the holotype specimens, 50 measurements were made for each taxonomically informative structure (such as the conidial length and width), and 25 for other structures. For the no-holotype specimens, 25 measurements were made for each taxonomically informative structure and 10 measurements were made for other structures. For the taxonomically informative structures, minimum, maximum, and average (mean) values are presented as (minimum–) (average − standard deviation)–(average + standard deviation) (–maximum). Extremes and averages are presented for other fungal structures.

To determine the optimal growth temperature for novel species, 5 mm mycelial plugs taken from the actively growing edges of the cultures were transferred to fresh MEA plates and incubated at 5–35 °C in 5 °C intervals, with 5 replicate plates per temperature per isolate. Colony diameters were measured after 7 days. Based on 7-day-old cultures grown on MEA at 25 °C, the colony color was described based on the color charts by Rayner [40], and the colony morphology was described. All descriptions were deposited in MycoBank (www.mycobank.org).

2.5. Inoculation Tests

The pathogenicity of three isolates of R. inexpectata (CSFF 26013, CSFF 26015, and CSFF 26033) and two isolates of Calonectria crousiana (CSFF 26024 and CSFF 26025) was tested by inoculating these fungi on Cinnamomum camphora S.F. Chen, L. Lombard, M.J. Wingf. and X.D. Zhou seedlings. Cinnamomum camphora seedlings of 40–60 cm in height with healthy leaves were used for inoculation. Mycelial plugs of 5 mm in diameter were cut from the actively growing margins of the 7-day-old MEA cultures and used to inoculate the leaves of Ci. camphora seedlings. For each isolate, 10 mycelial plugs were used to inoculate the abaxial surface of 10 leaves of 3–4 Ci. camphora seedlings. For the negative control, 10 sterile MEA plugs were used to inoculate 10 leaves. No wounds were made on the inoculated leaves. All inoculated and negative control seedlings were kept in moist plastic chambers and maintained under stable climatic conditions as follows: 85–99% humidity and 25–27 °C. The entire experiment was repeated a second time using the same method. Inoculation was performed from October to November 2024 at the Forestry Pathogen Center (FPC), College of Forestry, Fujian Agricultural and Forestry University, Fuzhou, Fujian Province, China.

On the day on which the most pathogenic isolate nearly rotted the entire inoculated leaf, the plastic chambers were removed, and all inoculated and negative control leaves were collected. To measure the lesion lengths on each leaf, the diameter of each lesion was measured, and the average diameter (length) of each leaf was calculated. Re-isolation was conducted to confirm Koch’s postulates. Small pieces of the discolored leaves (approximately 0.25 mm × 0.25 mm) were cut from the lesion edge and placed on 2% MEA at room temperature. Re-isolation was performed for all leaves inoculated with each isolate and the negative control. The identities of the re-isolated fungi were verified according to the culture morphology, the fruiting structure morphology, and the disease symptoms produced on the inoculated leaves compared with the original fungi used for inoculation.

The results were analyzed in EXCEL (2019). Single-factor analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed to define the effects of the fungal isolates on lesion length. To test the significance of the means, F-values with p < 0.05 were considered significantly different. The standard errors of the means of lesion length for each fungal isolate and the negative control were calculated.

3. Results

3.1. Fungal Isolation

Conidiophore masses were produced on the diseased leaves of all 31 sampled Ci. camphora trees. One or two single-conidium cultures obtained from each sampled tree were selected, and 54 Nectriaceae isolates were used for further study (Table 1) and separated into two groups by conidiophore and conidium morphology. Two isolates (Group One) produced significantly larger conidiophores and conidia than the other 52 isolates (Group Two), and the length of the conidia of the isolates in Group One was nearly twice that of the isolates in Group Two.

Table 1.

Isolates sequenced and used for phylogenetic analyses, morphological studies and inoculation tests in this study.

3.2. Multigene Phylogenetic Analyses

The amplicons generated for the tef1, tub2, cmdA, and his3 regions of fungi isolated in this study were approximately 480, 570, 685, and 450 bp, respectively. A BLAST search using the sequences of the tef1, tub2, cmdA, and his3 regions allowed us to divide the 54 isolates obtained in this study into two groups. Two isolates (CSFF 26024 and CSFF 26025), Group One, were of the genus Calonectria and were closest to the isolates of Ca. crousiana in the Ca. reteaudii species complex. The other 52 isolates in Group Two were closest to Curvicladiella cignea (Decock and Crous) Decock and Crous based on the tef1, tub2, and cmdA regions and closest to Calonectria species based on the his3 region. The sequences of the ex-type specimen strains and additional strains of all molecularly identified Calonectria species in the Ca. reteaudii (Bugnic.) C. Booth species complex and the representative Calonectria species in each of the other nine species complexes were downloaded from GenBank [28]. The ex-type specimen strains and additional strains of all molecularly identified species of Curvicladiella Decock and Crous and the species that were phylogenetically close to Curvicladiella were also downloaded from GenBank (Table 2). All downloaded sequences were used for comparisons and phylogenetic analyses.

Table 2.

Isolates from other studies used in the phylogenetic analyses for this study.

Isolates CSFF 26024 and CSFF 26025 in Group One were used for phylogenetic analyses. For the 52 isolates in Group Two, the genotype of each isolate was generated based on the tef1, tub2, cmdA, and his3 regions. Six genotypes were generated, and two isolates of each genotype were used for phylogenetic analyses. A total of 14 isolates were selected.

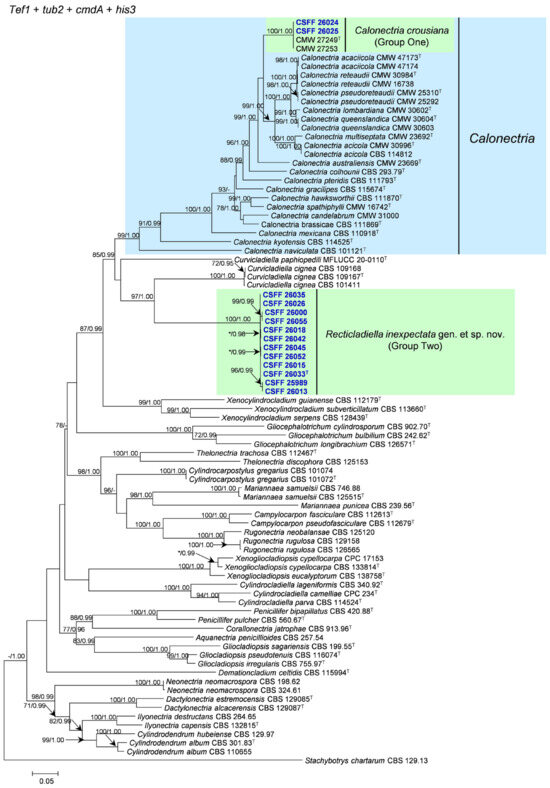

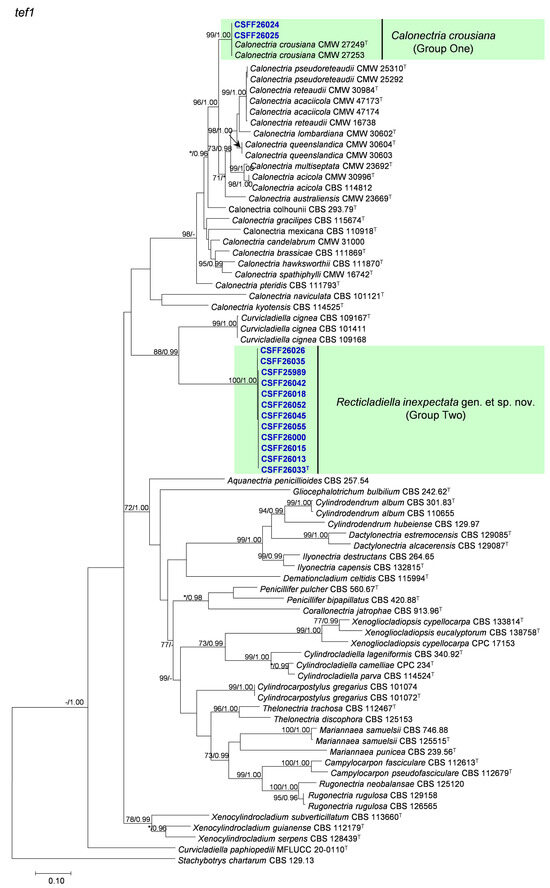

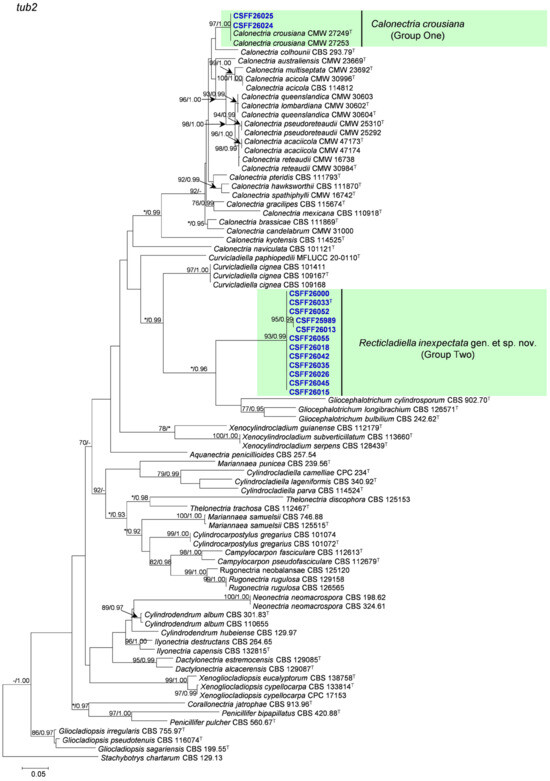

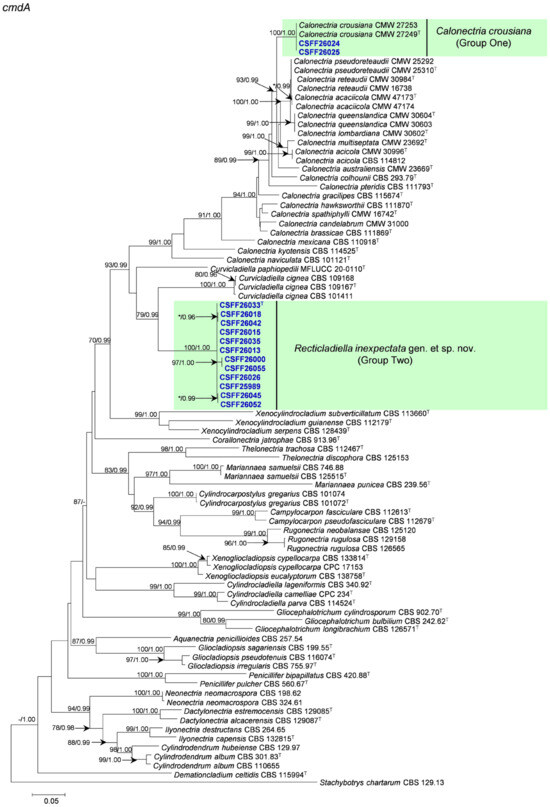

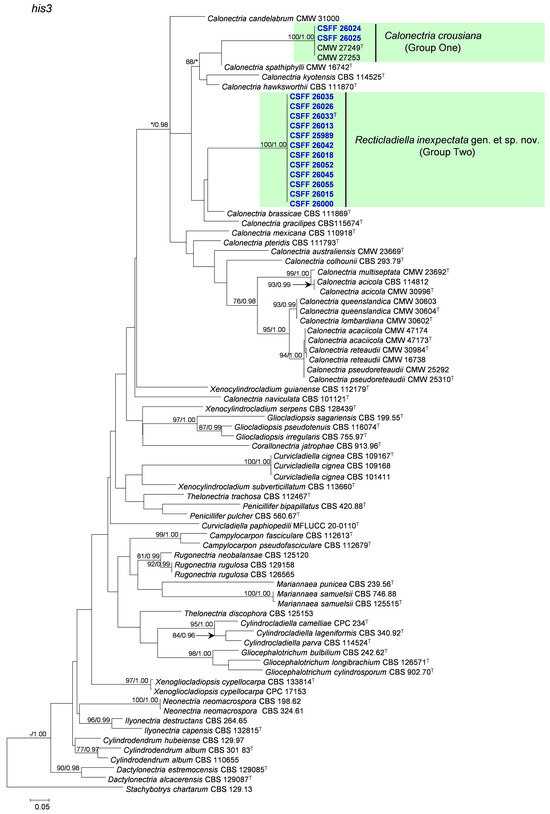

The phylogenetic analysis results indicate that the overall topologies generated from the BI analyses were similar to those from the ML analyses for each of tef1, tub2, cmdA, and his3 and the four-gene combination datasets. Consequently, only the ML tree with ML bootstrap support values and BI posterior probabilities is presented. The ML tree generated based on a combination of four gene sequences is presented in Figure 2, and those generated based on each of the four gene sequences are presented in Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5 and Figure 6. The phylogenetic analyses of tef1, tub2, cmdA, and his3 and the four-gene combination datasets consistently showed that CSFF 26024 and CSFF 26025 grouped in the same clade with ex-type isolate CMW 27249 of Ca. crousiana (Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5 and Figure 6). Therefore, isolates CSFF 26024 and CSFF 26025 were identified as Ca. crousiana. The 12 isolates in Group Two formed one independent clade for each of the tef1, tub2, cmdA, and his3 regions, showing a long tree length, high bootstrap and posterior probability support values (100%/1, 93%/0.99, 100%/1, and 100%/1, respectively), and phylogenetic similarity to Cu. cignea in tef1 and cmdA trees, Cu. cignea and Gliocephalotrichum species in the tub2 tree, and Calonectria species in the his3 tree (Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5 and Figure 6). The combined tree for tef1, tub2, cmdA, and his3 further demonstrates that the 12 isolates formed one independent clade with long tree length and high bootstrap and posterior probability values (100%/1) which was the most similar to species of Curvicladiella and Calonectria (Figure 2). Based on the phylogenetic analyses of tef1, tub2, cmdA, and his3 and their combined datasets, the 12 isolates in Group Two were identified as a novel taxon.

Figure 2.

The phylogenetic tree of Nectriaceae species based on maximum likelihood (ML) analyses of the combined tef1, tub2, cmdA, and his3 gene sequence dataset in this study. Bootstrap values ≥ 70% from the ML analysis and posterior probabilities values _≥ 0.95 obtained from Bayesian inference (BI) are indicated at the nodes as ML/BI. Bootstrap values < 70% or posterior probabilities values < 0.95 are marked with “*”, and absent analysis values are marked with “-”. “*/*”, “*/-”, “-/*”, and “-/-” are not displayed. Ex-type isolates are indicated with “T”. The isolates reported in this study are highlighted in bold and blue.

Figure 3.

The phylogenetic tree of Nectriaceae species based on maximum likelihood (ML) analyses of the tef1 gene sequence dataset in this study. Bootstrap values ≥ 70% from the ML analysis and posterior probabilities values _≥ 0.95 obtained from Bayesian inference (BI) are indicated at the nodes as ML/BI. Bootstrap values < 70% or posterior probabilities values < 0.95 are marked with “*”, and absent analysis values are marked with “-”. “*/*”, “*/-”, “-/*”, and “-/-” are not displayed. Ex-type isolates are indicated with “T”. The isolates reported in this study are highlighted in bold and blue.

Figure 4.

The phylogenetic tree of Nectriaceae species based on maximum likelihood (ML) analyses of the tub2 gene sequence dataset in this study. Bootstrap values ≥ 70% from the ML analysis and posterior probabilities values _≥ 0.95 obtained from Bayesian inference (BI) are indicated at the nodes as ML/BI. Bootstrap values < 70% or posterior probabilities values < 0.95 are marked with “*”, and absent analysis values are marked with “-”. “*/*”, “*/-”, “-/*”, and “-/-” are not displayed. Ex-type isolates are indicated with “T”. The isolates reported in this study are highlighted in bold and blue.

Figure 5.

The phylogenetic tree of the Nectriaceae species based on maximum likelihood (ML) analyses of the cmdA gene sequence dataset in this study. Bootstrap values ≥ 70% from the ML analysis and posterior probabilities values _≥ 0.95 obtained from Bayesian inference (BI) are indicated at the nodes as ML/BI. Bootstrap values < 70% or posterior probabilities values < 0.95 are marked with “*”, and absent analysis values are marked with “-”. “*/*”, “*/-”, “-/*”, and “-/-” are not displayed. Ex-type isolates are indicated with “T”. The isolates reported in this study are highlighted in bold and blue.

Figure 6.

The phylogenetic tree of Nectriaceae species based on maximum likelihood (ML) analyses of the his3 gene sequence dataset in this study. Bootstrap values ≥ 70% from the ML analysis and posterior probabilities values _≥ 0.95 obtained from Bayesian inference (BI) are indicated at the nodes as ML/BI. Bootstrap values < 70% or posterior probabilities values < 0.95 are marked with “*”, and absent analysis values are marked with “-”. “*/*”, “*/-”, “-/*”, and “-/-” are not displayed. Ex-type isolates are indicated with “T”. The isolates reported in this study are highlighted in bold and blue.

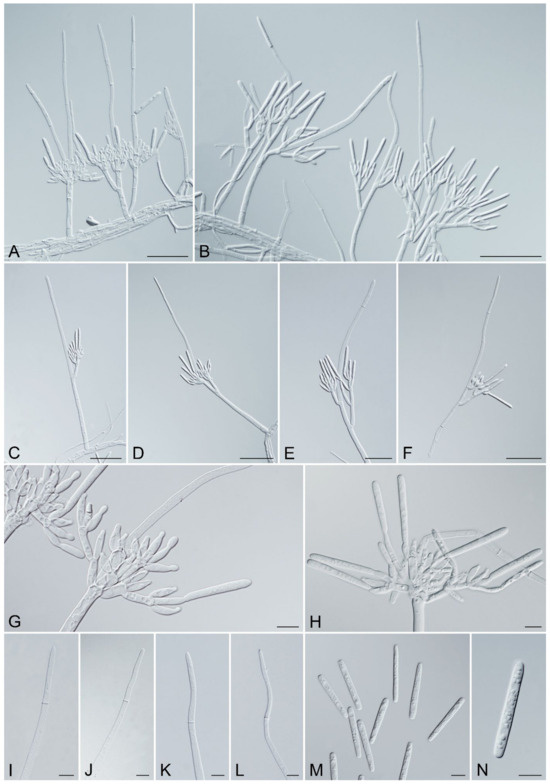

3.3. Morphology

Consistent with the phylogenetic analyses, the morphology of the 54 Nectriaceae isolates from Ci. camphora was separated into two distinct groups based on the morphological characteristics of the asexual structures, consistent with the two phylogenetic lineages representing the different genera recognized in this study. Both groups produced septate stipe extensions. Isolates in Group One (isolates CSFF 26024, and CSFF 26025) stipe extension tapered toward a clavate vesicle, and macroconidia (1–)3-septate and approximately two times the length of those in Nectriaceae isolates in Group Two, which presented morphological characteristics consistent with Ca. crousiana [47]. The stipe extensions of Group Two isolates tapered toward a terminal cell that was straight or occasionally slightly curved, making it morphologically significantly different from the phylogenetically close genera Calonectria (stipe extensions tapering toward a terminal vesicle) [47] and Curvicladiella (stipe extensions tapering toward a terminal cell that is curved similar to a swan neck) [60].

Based on phylogenetic analyses and morphological characteristics, the Group Two isolates clearly represented a previously undescribed genus and species. Based on three isolates of Group Two (CSFF 26013, CSFF 26015, and CSFF 26033), which represented a novel species, no sexual structures were produced in the crossing tests on MSA. Asexual structures were common for the three isolates on the SNA medium. The unknown genus and species are described as follows:

Taxonomy

Recticladiella S.F. Chen, gen. nov. MycoBank MB 856872.

Etymology: Rectus means straight in Latin, in reference to the terminal cells of the stipe extensions, always straight, which differ from its phylogenetically close genus Curvicladiella with curved terminal cells.

Description: Sexual morph not observed. Conidiophores penicillate, hyaline, consisting of a stipe, a penicillate arrangement of fertile branches, and several avesiculate stipe extensions. Stipe septate, hyaline, smooth; stipe extensions septate, straight to flexuous or sinuous, tapering toward a terminal cell; terminal cell straight, occasionally slightly curved. Conidiogenous apparatus with multiple branches. Primary branches aseptate, secondary branches aseptate, and tertiary branches aseptate, with each terminal branch producing multiple phialides. Phialides elongate doliiform to reniform or subcylindrical, hyaline, aseptate, and apex with minute periclinal thickening and inconspicuous collarette. Conidia cylindrical, rounded at both ends, straight, occasionally slightly curved, septate, lacking a visible abscission scar, held in parallel cylindrical clusters by colorless slime.

Type species: Recticladiella inexpectata F.Y. Han and S.F. Chen

Recticladiella inexpectata F.Y. Han and S.F. Chen, sp. nov. MycoBank MB 856873. Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Recticladiella inexpectata (ex-type CSFF 26033). (A,B) Penicillate conidiophores with one to two stipe extensions. (C–F) Penicillate conidiophores with straight (C) to flexuous (D–F) stipe extensions. (G,H) Penicillate conidiogenous apparatus. (I–L) Straight terminal cell (I), occasionally slightly curved (J–L). (M,N) Conidia. Scale bars: A–F = 50 μm; G–N = 10 μm.

Etymology: Inexpectatus means unexpected in Latin, in reference to having identified the new taxon unexpectedly.

Description: Sexual morph not observed. Conidiophores penicillate, hyaline, consisting of a stipe, a penicillate arrangement of fertile branches, and several avesiculate stipe extensions. Stipe septate, up to 3, septate, hyaline, smooth, 33–89.5 × 4–8.5 μm (avg. = 61.5 × 5.5 μm); stipe extensions, 1–2, septate, straight to flexuous or sinuous, 24.5–201.5 μm (avg. = 93.5 μm) long, tapering toward a terminal cell; terminal cell, straight, occasionally slightly curved, 27.5–90 μm (avg. = 49 μm) long, (2–)3–4.5(–5) μm (avg. = 4 μm) in diameter. Conidiogenous apparatus 15–104 μm (avg. = 53 μm) wide, 12–82 μm (avg. = 49.5 μm) long. Primary branches aseptate, 9–34.5 × 3–7 μm (avg. = 20 × 4.5 μm); secondary branches aseptate, 10.5–31.5 × 3–6 μm (avg. = 15 × 4.5 μm); tertiary branches aseptate, 9–19 × 2.5–4.5 μm (avg. = 13 × 4 μm), each terminal branch producing 2–5 phialides. Phialides elongate doliiform to reniform, or subcylindrical, hyaline, aseptate, 7.5–17.5 × 2.5–5 μm (avg. = 12 × 3.5 μm), apex with minute periclinal thickening and inconspicuous collarette. Conidia cylindrical, rounded at both ends, straight, occasionally slightly curved, (32–)36–41(–46.5) × (3.5–)4–5.5(–6) μm (avg. = 38.5 × 5 μm), 1-septate, lacking a visible abscission scar, held in parallel cylindrical clusters by colorless slime.

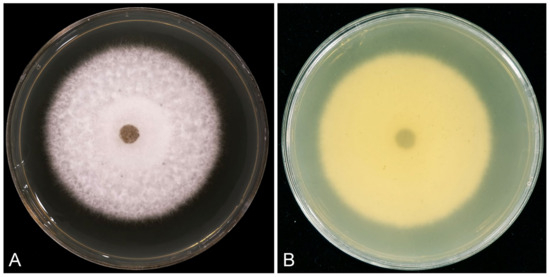

Culture characteristics: Colonies white on the surface and salmon in reverse on MEA after 7 days, with smooth margins, extensive aerial mycelium in the middle and at the margins, and chlamydospores were not observed (Figure 8). Optimal growth temperature at 25 °C, nearly no growth at 5 °C and 35 °C; after 7 days, 5 mm mycelial plug colonies at 5 °C, 10 °C, 15 °C, 20 °C, 25 °C, 30 °C, and 35 °C reached 5.5 mm, 12.3 mm, 21.7 mm, 31.0 mm, 54.6 mm, 52.5 mm, and 5.6 mm, respectively.

Figure 8.

Morphological characteristics of Recticladiella inexpectata (ex-type CSFF 26033) colony on MEA after seven days at 25 °C. (A) White on the surface. (B) Salmon in reverse.

Ecology and distribution: Recticladiella inexpectata isolated from leaves of 1–150-year-old Ci. camphora trees planted in Fujian and Guangdong Provinces, China.

Typus: China, Fujian Province, Zhangzhou Region, Longhai District, Chengxi Town, 24°29′99.5″ N, 117°61′43.19″ E, from the leaf of a Ci. camphora tree, July 2024, ShuaiFei Chen, Ying Liu, SuXin Huang, LiSha Wang, and JiaCheng Fang (holotype HMAS 353355, fungarium specimen preserved as dried culture with asexual structures in metabolically inactive state; culture ex-type CSFF 26033 = CGMCC 3.28323). GenBank accession numbers PQ727744 (tef1), PQ727798 (tub2), PQ727852 (cmdA), and PQ727690 (his3).

Additional material examined: Fujian Province, Zhangzhou Region, Longhai District, Chengxi Town, 24°33′10.62″ N, 117°64′70.47″ E, from leaf of a Ci. camphora tree, July 2024, ShuaiFei Chen, Ying Liu, SuXin Huang, LiSha Wang, and JiaCheng Fang (HMAS 353356, fungarium specimen of dried culture with asexual structures in metabolically inactive state; culture CSFF 26015 = CGMCC 3.28322). GenBank accession numbers PQ727729 (tef1), PQ727783 (tub2), PQ727837 (cmdA), and PQ727675 (his3).

Notes: Recticladiella inexpectata has been described as a new genus and species based on multi-gene DNA sequence comparisons and morphological characteristics. Before this study, several Nectriaceae genera phylogenetically close to Recticladiella produced stipe extensions: Calonectria, Cylindrocladiella Boesew., Curvicladiella, Gliocephalotrichum J.J. Ellis and Hesselt., Xenocylindrocladium Decock, Hennebert and Crous, and Xenogliocladiopsis Crous and W.B. Kendr. Recticladiella (stipe extensions single to multiple, septate, no vesicle) can be distinguished from Calonectria (stipe extensions: single to multiple, septate, with vesicles), Cylindrocladiella (stipe extensions: single, aseptate, with vesicles), Gliocephalotrichum (stipe extension number unknown, septate, with vesicles), Xenocylindrocladium (stipe extensions: single, septate, no vesicle), and Xenogliocladiopsis (stipe extensions: single, septate, no vesicle) based on the morphology of their stipe extensions [28,60,68,77,78,79]. Recticladiella is the most morphologically similar to Curvicladiella, both of which produce single to multiple stipe extensions that are septate and without a vesicle but with a terminal cell. The stipe extension terminal cells of Curvicladiella are curved similar to a swan neck, while those of Recticladiella are straight and occasionally slightly curved [60]. Furthermore, Recticladiella can be easily distinguished from its most phylogenetically close genus, Curvicladiella, based on the DNA sequences of each of the tef1, tub2, cmdA, and his3 gene regions. Recticladiella inexpectata and Cu. cignea are the type species of their genera. Based on the comparisons between the ex-type isolates of R. inexpectata (CSFF 26033) and Cu. cignea (CBS 109167), there are 92, 102, 119, and 80 base differences in the tef1, tub2, cmdA, and his3 gene regions, respectively.

3.4. Inoculation Tests

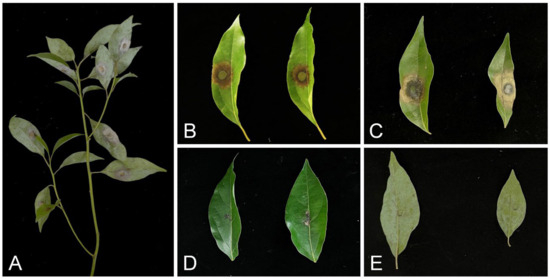

The inoculation results show that the R. inexpectata isolates produced lesions on the inoculated leaves in both experiments two days after inoculation. Five days after inoculation, diseased lesions appeared on the leaves inoculated with Ca. crousiana. The most pathogenic isolate, CSFF 26015, nearly rotted the entire inoculated leaf 6 days after inoculation (Figure 8A), and the lesion length was measured for all inoculated isolates. The leaves of Ci. camphora seedlings inoculated with R. inexpectata isolates (CSFF 26013, CSFF 26015, and CSFF 26033) and Ca. crousiana isolates (CSFF 26024 and CSFF 26025) displayed spots, lesions, and blight (Figure 9A–D). No disease symptoms were observed in the leaves of the negative control seedlings (Figure 9E). The fungal colony shared the same morphological characteristics as the plants originally inoculated with R. inexpectata (Figure 8) and Ca. crousiana [47] isolates that were successfully re-isolated from the leaf lesions. No Recticladiella or Calonectria were re-isolated from the negative control leaves. Consequently, Koch’s postulates were fulfilled.

Figure 9.

Symptoms on leaves of Ci. camphora seedlings caused by R. inexpectata and Ca. crousiana mycelial plugs and MEA plugs (negative controls). (A) Cinnamomum camphora seedling leaves six days after inoculation with R. inexpectata isolate CSFF 26015 in experiment two. (B,C) Leaves six days after inoculation with isolate CSFF 26015 in Experiment One (B) and experiment two (C). (D) Leaves six days after inoculation with Ca. crousiana isolate CSFF 26024 in experiment two. (E) Leaves six days after inoculation with MEA plugs in Experiment Two.

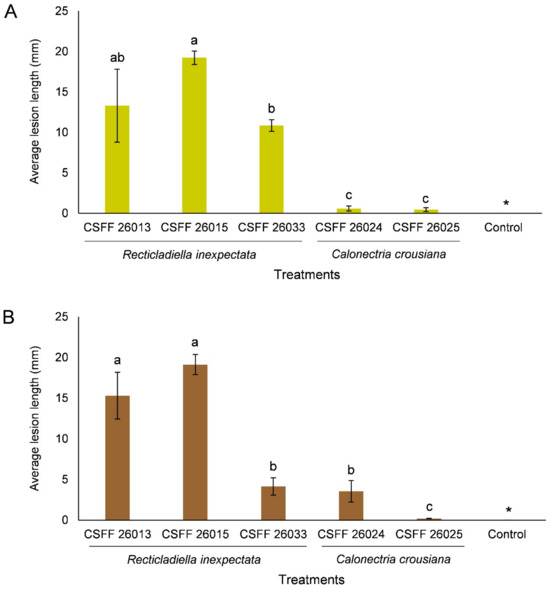

The ANOVA showed that the results of the replicated inoculation tests were significantly different (p < 0.05). Thus, the data for each experiment were analyzed separately. The inoculation results of the two experiments consistently showed that the R. inexpectata isolates (CSFF 26013, CSFF 26015, and CSFF 26033) were more pathogenic than the Ca. crousiana isolates (CSFF 26024 and CSFF 26025) (Figure 10A,B). Recticladiella inexpectata isolates CSFF 26013 and CSFF 26015 produced significantly longer lesions than Ca. crousiana isolates CSFF 26024 and CSFF 26025. Of the R. inexpectata isolates, CSFF 26015 produced significantly longer lesions than CSFF 26033 in both experiments (Figure 10A,B).

Figure 10.

Histograms showing the average lesion lengths on leaves resulting from the inoculation trials of Ci. camphora with three isolates of R. inexpectata, two isolates of Ca. crousiana, and a negative control. Two experiments (A,B) were conducted. The vertical bars represent the standard errors of the means. Different letters above the error bars indicate treatments that were significantly different (p = 0.05). “*” represents no lesions produced by the negative control in both experiments.

4. Discussion

Cinnamomum camphora trees are widely planted in China, especially for landscaping purposes. Research on diseases associated with these trees in China is relatively limited. One potential reason is that people believe that the oil of this tree species can prevent pathogen infection. In this study, we identified two Nectriaceae species, Ca. crousiana, and R. inexpectata, from the diseased leaves of Ci. camphora trees planted in southern China. The identification of these two species was supported by four-gene DNA sequence comparisons and morphological characteristics. The inoculation study demonstrated that both species were pathogenetic to the tested Ci. camphora seedlings.

Recticladiella represents a new genus in the Nectriaceae. It can be distinguished from all other genera in the family based on the DNA sequence data of the tef1, tub2, cmdA, and his3 gene regions. Morphologically, this genus is the most similar to Curvicladiella and Calonectria. The morphology of this genus differs from all other Nectriaceae genera in terms of the number of stipe extensions, presence or absence of septa, presence or absence of a vesicle, and curved or straight terminal cells [7,28,60].

Inoculation tests showed that R. inexpectata caused disease in native Ci. camphora seedlings. The R. inexpectata isolates produced disease symptoms on inoculated Ci. camphora leaves within two days, these fungi are clearly leaf pathogens of Ci. camphora. Cinnamomum camphora was isolated from native Ci. camphora trees planted in a range of geographic regions in southern China. Recticladiella inexpectata may be a native pathogen in China, and it has the potential to spread to new hosts and areas. We hypothesize that there are more Recticladiella species distributed on native Ci. camphora trees and other tree species in China.

Calonectria crousiana was first isolated and identified from Eucalyptus leaves in Fujian Province in 2011 [47]. In this study, Ca. crousiana was isolated from one diseased Ci. camphora tree planted in one nursery. Inoculation tests in previous studies and this study showed that Ca. crousiana is pathogenic to the tested Eucalyptus genotypes and Ci. camphora seedlings. These results suggest that Ca. crousiana may have a wider plant host range. Calonectria crousiana may be native to native Chinese Ci. camphora trees and spread to non-native Eucalyptus trees, but confirmation of this hypothesis requires more systematic research.

Reports of Nectriaceae associated with Ci. camphora are currently limited. Few species in four genera of Nectriaceae were reported in Ci. camphora (https://fungi.ars.usda.gov; search on 7 December 2024). These include Calonectria ilicicola Boedijn and Reitsma, Cylindrocladiella sp., Fusarium oxysporum Schltdl., and F. solani (Mart.) Sacc. in the United States; F. decemcellulare Brick in China; and Neonectria castaneicola (W. Yamam. and Oyasu) Tak. Kobay. and Hirooka and N. cinnamomea (Brayford and Samuels) Brayford and Samuels in Japan [7,25,80,81,82,83,84]. Fusarium decemcellulare was proved to cause root rot in Ci. camphora seedlings in China [25]. Whether there are other species pathogenic to Ci. camphora is still not clear. However, some species were isolated from the diseased tissues of Ci. camphora; for instance, N. castaneicola was isolated from the cracked rough back of Ci. camphora trees [81].

The results of this study expand our understanding of the species diversity, geographic distribution, and pathogenicity of Nectriaceae species in native Ci. camphora trees in China. Besides the identification of the new genus and species R. inexpectata, this is also the first report of Ca. crousiana in Ci. camphora. These results emphasize that there are many pathogens of woody plants, including some native trees, that remain to be discovered in China. In the future, disease surveys and investigations need to be conducted in wider regions on native Ci. camphora trees and plantation trees, such as commercial Eucalyptus, to further understand species diversity, pathogenicity, and potential plant health threats in China.

Author Contributions

S.C. collected the samples. S.C. conceived and designed the experiments. F.H. performed the laboratory work and inoculation tests. S.C. analyzed the data. All authors wrote and revised the paper. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Fujian Agricultural and Forestry University High Level Talent Program (Project No. 118-118360020), and the National Ten-thousand Talents Program (Project No. W03070115).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ying Liu, LiSha Wang, HongBin Dong, XiaoMei Liu, SuXin Huang and JiaCheng Fang for their assistance in collecting samples. We thank Ying Liu for her assistance in analyzing the data.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Rossman, A.Y.; Samuels, G.J.; Rogerson, C.T.; Lowen, R. Genera of Bionectriaceae, Hypocreaceae and Nectriaceae (Hypocreales, Ascomycetes). Stud. Mycol. 1999, 42, 1–248. [Google Scholar]

- Rossman, A.Y. Towards monophyletic genera in the holomorphic Hypocreales. Stud. Mycol. 2000, 45, 27–34. [Google Scholar]

- Lombard, L.; Van der Merwe, N.A.; Groenewald, J.Z.; Crous, P.W. Generic concepts in Nectriaceae. Study Mycol. 2015, 80, 189–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; White, J.F.; Malik, K.; Li, C.J. Molecular assessment of oat head blight fungus, including a new genus and species in a family of Nectriaceae. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2024, 471, 110715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Han, S.L.; Zhang, Y.Y.; Cai, L.; Zhao, P. Heteroverticillium phytelephatis gen. et sp. nov. intercepted from nuts of Phytelephas macrocarpa, with an updated phylogenetic assessment of Nectriaceae. Mycology 2023, 14, 155–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perera, R.H.; Hyde, K.D.; Jones, E.B.G.; Maharachchikumbura, S.S.N.; Bundhum, D.; Camporesi, E.; Akulov, A.; Liu, J.K.; Liu, Z.Y. Profile of Bionectriaceae, Calcarisporiaceae, Hypocreaceae, Nectriaceae, Tilachlidiaceae, Ijuhyaceae fam. nov., Stromatonectriaceae fam. nov. and Xanthonectriaceae fam. nov. Fungal Divers. 2023, 118, 95–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crous, P.W. Taxonomy and Pathology of Cylindrocladium (Calonectria) and Allied Genera; APS Press: St. Paul, MN, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Crous, P.W.; Lombard, L.; Sandoval-Denis, M.; Seifert, K.A.; Schroers, H.J.; Chaverri, P.; Gené, J.; Guarro, J.; Hirooka, Y.; Bensch, K.; et al. Fusarium: More than a node or a foot-shaped basal cell. Stud. Mycol. 2021, 98, 100116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.Q.; Wingfield, M.J.; Barnes, I.; Chen, S.F. Calonectria in the age of genes and genomes: Towards understanding an important but relatively unknown group of pathogens. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2022, 23, 1060–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiello, D.; Guarnaccia, V.; Vitale, A.; LeBlanc, N.; Shishkoff, N.; Polizzi, G. Impact of Calonectria diseases on ornamental horticulture: Diagnosis and control strategies. Plant Dis. 2022, 106, 1773–1787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daughtrey, M.L. Boxwood Blight: Threat to Ornamentals. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2019, 57, 189–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kameyama, Y. Development of microsatellite markers for Cinnamomum camphora (Lauraceae). Am. J. Bot. 2012, 99, e1–e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Z.; Liu, B.; Yang, Y.; Ferguson, D.K. Phylogeny and taxonomy of Cinnamomum (Lauraceae). Ecol. Evol. 2022, 12, e9378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, D.C.; Zhong, C.M.; Chen, Y.L.; Zhang, L.P.; Huang, Y.P. Research progress of distribution and prevention of disease in Cinnamomum camphora (L.) Presl in China. Biol. Disaster Sci. 2018, 41, 176–183. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, F.; Bi, L.W.; Zhao, Z.D. Review on plant resources and chemical composition of Camphor tree. Nat. Prod. Res. Dev. 2017, 29, 517–531. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.; Yan, W. Conservation and applications of camphor tree (Cinnamomum camphora) in China: Ethnobotany and genetic resources. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2016, 63, 1049–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.P.; Wu, X.X.; Yong, L.; Li, X.M.; Zhang, D.Q.; Chen, Y.Y. Efficient extraction of bioenergy from Cinnamomum camphora leaves. Front. Energy Res. 2020, 8, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afrin, F.; Chouhan, G.; Islamuddin, M.; Want, M.Y.; Ozbak, H.A.; Hemeg, H.A. Cinnamomum cassia exhibits antileishmanial activity against Leishmania donovani infection in vitro and in vivo. PLoS Neglected Trop. Dis. 2019, 13, e0007227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.; Zeng, C.; Zeng, Z.; Wang, B.; Gong, D. Cinnamomum camphora Seed Kernel Oil Ameliorates Oxidative Stress and Inflammation in Diet-Induced Obese Rats. J. Food Sci. 2016, 81, H1295–H1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teng, S.C. Notes on Hypocreales from China. Sinensia 1934, 4, 269–298. [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang, W.Y. Taxonomy and related studies on the nectrioid fungi from China. Chin. Bull. Life Sci. 2010, 22, 1083–1085. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, Z.Q.; Zhuang, W.Y. Five species of Nectriaceae new to China. Mycosystema 2022, 41, 1008–1017. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- He, J.; Li, D.W.; Cui, W.L.; Zhu, L.H.; Lin, H. Morphological and phylogenetic analyses reveal three new species of Fusarium (Hypocreales, Nectriaceae) associated with leaf blight on Cunninghamia lanceolata in China. Mycokeys 2024, 101, 45–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Deng, Y.; Wang, F.H.; Jeewon, R.; Zeng, Q.; Xu, X.L.; Liu, Y.G.; Yang, C.L. Morphological and molecular analyses reveal two new species of Microcera (Nectriaceae, Hypocreales) associated with scale insects on walnut in China. Mycokeys 2023, 98, 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, W.L.; Hu, Y.C.; Wu, T.; Luan, F.G.; Zheng, Y.M.; Zhou, L.F.; Zhou, X.D. Fusarium decemcellulare Brick causes root rot of Cinnamomum camphora (Linn) Presl. For. Pathol. 2024, 54, e12867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Burik, J.A.H.; Schreckhise, R.W.; White, T.C.; Bowden, R.A.; Myerson, D. Comparison of six extraction techniques for isolation of DNA from filamentous fungi. Med. Mycol. 1998, 36, 299–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carbone, I.; Kohn, L.M. A method for designing primer sets for speciation studies in filamentous ascomycetes. Mycologia 1999, 91, 553–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.L.; Li, J.Q.; Wingfield, M.J.; Duong, T.A.; Wingfield, B.D.; Crous, P.W.; Chen, S.F. Reconsideration of species boundaries and proposed DNA barcodes for Calonectria. Stud. Mycol. 2020, 97, 100106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Donnell, K.; Kistler, H.C.; Cigelnik, E.; Ploetz, R.C. Multiple evolutionary origins of the fungus causing Panama disease of banana: Concordant evidence from nuclear and mitochondrial gene genealogies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1998, 95, 2044–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donnell, K.; Cigelnik, E. Two divergent intragenomic rDNA ITS2 types within a monophyletic lineage of the fungus Fusarium are nonorthologous. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 1997, 7, 103–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crous, P.W.; Groenewald, J.Z.; Risède, J.M.; Simoneau, P.; Hyde, K.D. Calonectria species and their Cylindrocladium anamorphs: Species with sphaeropedunculate vesicles. Stud. Mycol. 2004, 50, 415–430. [Google Scholar]

- Groenewald, J.Z.; Nakashima, C.; Nishikawa, J.; Shin, H.D.; Jama, A.N.; Groenewald, M.; Braun, U.; Crous, P.W. Species con-cepts in Cercospora: Spotting the weed among the roses. Stud. Mycol. 2013, 75, 115–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Tamura, K. MEGA7: Molecular evolutionary genetic analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2016, 33, 1870–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katoh, K.; Standley, D.M. MAFFT Multiple sequence alignment software Version 7: Improvements in performance and usability. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013, 30, 772–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guindon, S.; Gascuel, O. A simple, fast, and accurate algorithm to estimate large phylogenies by maximum likelihood. Syst. Biol. 2003, 52, 696–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronquist, F.; Teslenko, M.; Van Der Mark, P.; Ayres, D.L.; Darling, A.; Höhna, S.; Larget, B.; Liu, L.; Suchard, M.; Huelsenbeck, J. MrBayes 3.2: Efficient Bayesian phylogenetic inference and model choice across a large model space. Syst. Biol. 2012, 61, 539–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nirenberg, H.I. A simplified method for identifying Fusarium spp. occurring on wheat. Can. J. Bot. 1981, 59, 1599–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Chen, S.F. Cylindrocladiella species from Cunninghamia lanceolata plantation soils in southwestern China. Fungal Syst. Evol. 2024, 13, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerber, J.C.; Correll, J.C. Characterization of Glomerella acutata, the teleomorph of Colletotrichum acutatum. Mycologia 2001, 93, 216–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayner, R.W. A Mycological Colour Chart; Commonwealth Mycological Institute and British Mycological Society: London, UK, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Pham, N.Q.; Barnes, I.; Chen, S.F.; Liu, F.F.; Dang, Q.N.; Pham, T.Q.; Lombard, L.; Crous, P.W.; Wingfield, M.J. Ten new species of Calonectria from Indonesia and Vietnam. Mycologia 2019, 111, 78–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadgil, P.; Dick, M. Fungi silvicolae novazelandie: 10. New Zealand J. For. Sci. 2004, 44, 30. [Google Scholar]

- Lombard, L.; Crous, P.W.; Wingfield, B.D.; Wingfield, M.J. Phylogeny and systematics of the genus Calonectria. Study Mycol. 2010, 66, 31–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crous, P.W.; Groenewald, J.Z.; Risède, J.M.; Simoneau, P.; Hyde, K.D. Calonectria species and their Cylindrocladium anamorphs: Species with clavate vesicles. Study Mycol. 2006, 55, 213–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lombard, L.; Wingfield, M.J.; Alfenas, A.C.; Crous, P.W. The forgotten Calonectria collection: Pouring old wine into new bags. Study Mycol. 2016, 85, 159–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peerally, M.A. Calonectria colhounii sp. nov., a common parasite of tea in Mauritius. Trans. Br. Mycol. Soc. 1973, 61, 89–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.F.; Lombard, L.; Roux, J.; Xie, Y.J.; Wingfield, M.J.; Zhou, X.D. Novel species of Calonectria associated with Eucalyptus leaf blight in Southeast China. Persoonia 2011, 26, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crous, P.W.; Mchau, G.R.A.; Zyl, W.H.V.; Wingfield, M.J. New species of Calonectria and Cylindrocladium isolated from soil in the tropics. Mycologia 1997, 89, 653–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Terashita, T. A new species of Calonectria and its conidial state. Trans. Mycol. Soc. Jpn. 1968, 8, 124–129. [Google Scholar]

- Lombard, L.; Zhou, X.D.; Crous, P.W.; Wingfield, B.D.; Wingfield, M.J. Calonectria species associated with cutting rot of Euca-lyptus. Persoonia 2010, 24, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marin-Felix, Y.; Groenewald, J.Z.; Cai, L.; Chen, Q.; Marincowitz, S.; Barnes, I.; Bensch, K.; Braun, U.; Camporesi, E.; Damm, U.; et al. Genera of phytopathogenic fungi: GOPHY 1. Study Mycol. 2017, 86, 99–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schoch, C.L.; Crous, P.W.; Wingfield, B.D.; Wingfield, M.J. The Cylindrocladium candelabrum species complex includes four distinct mating populations. Mycologia 1999, 91, 286–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crous, P.W.; Wingfield, M.J.; Mohammed, C.; Yuan, Z.Y. New foliar pathogens of Eucalyptus from Australia and Indonesia. Mycol. Res. 1998, 102, 527–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crous, P.W.; Wingfield, M.J.; Alfenas, A.C. Additions to Calonectria. Mycotaxon 1993, 46, 217–234. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, J.C.; Crous, P.W.; Old, K.M.; Dudzinski, M.J. Non-conspecificity of Cylindrocladium quinqueseptatum and Calonectria quin-queseptata based on a β-tubulin gene phylogeny and morphology. Can. J. Bot. 2001, 79, 1241–1247. [Google Scholar]

- EI-Gholl, N.E.; Uchida, J.Y.; Alfenas, A.C.; Schubert, T.; Alfieri, S.; Chase, A. Induction and description of perithecia of Calonectria spathiphylli sp. nov. Mycotaxon 1992, 45, 285–300. [Google Scholar]

- Cabral, A.; Rego, C.; Nascimento, T.; Oliveira, H.; Groenewald, J.Z.; Crous, P.W. Multi-gene analysis and morphology reveal novel Ilyonectria species associated with black foot disease of grapevines. Fungal Biol. 2012, 116, 62–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halleen, F.; Schroers, H.J.; Groenewald, J.Z.; Crous, P.W. Novel species of Cylindrocarpon (Neonectria) and Campylocarpon gen. nov. associated with black foot disease of grapevines (Vitis spp.). Study Mycol. 2004, 50, 431–455. [Google Scholar]

- Herrera, C.S.; Rossman, A.Y.; Samuels, G.J.; Lechat, C.; Chaverri, P. Revision of the genus Corallomycetella with Corallonectria gen. nov. for C. jatrophae (Nectriaceae, Hypocreales). Biology 2013, 32, 518–544. [Google Scholar]

- Decock, C.; Crous, P.W. Curvicladium gen. nov., a new hyphomycete genus from Frech Guiana. Mycologia 1998, 90, 276–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Song, L.C.; Feng, Y.; Ding, H.X.; Liu, Z.Y. First Report of Leaf Blight on Paphiopedilum Caused by Curvicladiella sp. (GZCC19-0342) in China. Plant Dis. 2020, 104, 2754–3089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombard, L.; Shivas, R.G.; To-Anum, C.; Crous, P.W. Phylogeny and taxonomy of the genus Cylindrocladiella. Mycol. Prog. 2012, 11, 835–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Coller, G.J.; Denman, S.; Groenewald, J.Z.; Lamprecht, S.C.; Crous, P.W. Characterisation and pathogenicity of Cylindro-cladiella spp. associated with root and cutting rot symptoms of grapevines in nurseries. Australas. Plant Pathol. 2005, 34, 489–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombard, L.; Crous, P.W. Phylogeny and taxonomy of the genus Gliocladiopsis. Persoonia 2012, 28, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lombard, L.; Cheewangkoon, R.; Crous, P.W. New Cylindrocladiella spp. From Thailand soils. Mycosphere 2017, 8, 1088–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crous, P.W.; Allegrucci, N.; Arambarri, A.M.; Cazau, M.C.; Groenewald, J.Z.; Wingfield, M.J. Dematiocladium celtidis gen. sp. nov. (Nectriaceae, Hypocreales), a new genus from Celtis leaf litter in Argentina. Mycol. Res. 2005, 109, 833–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Decock, C.; Huret, S.; Charue, P. Anamorphic fungi from French Guyana: Two undescribed Gliocephalotrichum species (Nectria-ceae, Hypocreales). Mycologia 2006, 98, 488–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombard, L.; Serrato-Diaz, L.M.; Cheewangkoon, R.; French-Monar, R.D.; Decock, C.; Crous, P.W. Phylogeny and taxonomy of the genus Gliocephalotrichum. Persoonia 2014, 32, 127–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombard, L.; Bezuidenhout, C.M.; Crous, P.W. Ilyonectria black foot rot associated with Proteaceae. Australas. Plant Pathol. 2013, 42, 337–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luangsa-ard, J.J.; Hywel-Jones, N.L.; Manoch, L.; Samson, R.A. On the relationships of Paecilomyces sect. Isarioidea species. My-Cological Res. 2005, 109, 581–589. [Google Scholar]

- Gräfenhan, T.; Schroers, H.J.; Nirenberg, H.I.; Seifert, K.A. An overview of the taxonomy, phylogeny, and typification of nectriaceous fungi in Cosmospora, Acremonium, Fusarium, Stilbella, and Volutella. Study Mycol. 2011, 68, 79–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castlebury, L.A.; Rossman, A.Y.; Hyten, A.S. Phylogenetic relationships of Neonectria/Cylindrocarpon on Fagus in North America. Can. J. Bot. 2006, 84, 1417–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuels, G.J. Nectria and Penicillifer. Mycologia 1989, 81, 347–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Emden, J.H. Penicillifer, a new genus of hyphomycetes from soil. Acta Bot. Neerl. 1968, 17, 54–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaverri, P.; Salgado, C.; Hirooka, Y.; Rossman, A.Y.; Samuels, G.J. Delimitation of Neonectria and Cylindrocarpon (Nectriaceae, Hypocreales, Ascomycota) and related genera with Cylindrocarpon-like anamorphs. Study Mycol. 2011, 68, 57–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crous, P.W.; Decock, C.; Schoch, C.L. Xenocylindrocladium guianense and X. subverticillatum, two new species of hyphomycetes from plant debris in the tropics. Mycoscience 2001, 42, 559–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decock, C.; Hennebert, G.L.; Crous, P.W. Nectria serpens sp. nov. and its hyphomycetous anamorph Xenocylindrocladium gen. nov. Mycol. Res. 1997, 101, 786–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crous, P.W.; Kendrick, W.B. Arnaudiella eucalyptorum sp. nov. (Dothideales, Ascomycetes), and its hyphomycetous anamorph Xenogliocladiopsis gen. nov., from Eucalyptus leaf litter in South Africa. Can. J. Bot. 1994, 72, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boesewinkel, H.J. Cylindrocladiella, a new genus to accommodate Cylindrocladium parvum and other small-spored species of Cylindrocladium. Can. J. Bot. 1982, 60, 2288–2294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- French, A.M. California Plant Disease Host Index; California Department of Food and Agriculture: Sacramento, CA, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Hirooka, Y.; Kobayashi, T.; Natsuaki, K.T. Neonectria castaneicola and Neo. rugulosa in Japan. Mycologia 2005, 97, 1058–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirooka, Y.; Kobayashi, T. Taxonomic studies of nectrioid fungi in Japan. I: The genus Neonectria. Mycoscience 2007, 48, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, J.W. Tri-Ology Technical Report; Division of Plant Industry: Gainesville, FL, USA, 1992; Volume 31, pp. 5–8. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, J.W. Tri-Ology Technical Report; Division of Plant Industry: Gainesville, FL, USA, 1993; Volume 32, pp. 7–8. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).