1. Introduction

Surgical palliation of SV patients is performed in up to three stages to separate the pulmonary and systemic blood flow. Stage I palliation is performed in the newborn period (if needed) to balance the pulmonary and systemic blood flow. After a few months, a bidirectional cavopulmonary connection (BCPC) is performed to partially separate the pulmonary circulation, while a total cavopulmonary connection (TCPC) then results in a complete oxygenation of the venous blood [

1]. After TCPC, blood circulation relies entirely on a passive venous return to drive blood flow through the pulmonary arteries without the assistance of a sub-pulmonary ventricle. A common problem in single ventricle patients after BCPC and TCPC is the development of different types of collateral vessels, due to various reasons [

2,

3,

4].

In the case of a single ventricle diastolic or systolic failure or obstruction in the BCPC or TCPC pathway, postcapillary end diastolic pressure (EDP) of the systemic ventricle or pulmonary artery pressure (PAP) raises disproportionally [

5,

6]. For pressure relief and a reduction of the transpulmonary gradient, veno-venous collaterals (VVCs) form by dilation of pre-existing embryologic venous channels. VVCs originate from the systemic veins and either drain into the pulmonary (PV) or the systemic venous (SV) system. The reported incidence of VVCs in single ventricle patients varies from 14 to 31% [

6,

7,

8]. After BCPC, the systemic venous to systemic venous collaterals lead to a run-off of blood flow into the low-pressure circulation of the inferior vena cava (IVC) [

2,

9] and therefore to pressure reduction. Thus, the effective pulmonary blood flow is reduced and, together with the right-to-left shunt via the VVCs, this might lead to systemic arterial desaturation [

10]. In patients with reduced oxygen saturation or exercise-related hypoxia, the treatment option is an interventional closure to increase systemic oxygen saturation, although the effect of embolization is controversially discussed, mainly because of the risk of recurrence. Additionally, VVCs increase the risk of paradoxical thromboembolism [

10,

11]. Small collateral vessels can be easily closed using metal spirals (coils), whereas large vessels may require placement of intravascular devices [

12].

Aortopulmonary collaterals (APCs) are persistent/reopened segmental arteries or newly formed vessels which connect the aorta or aortic branches with the pulmonary artery vessel bed. They form in conditions with compromised pulmonary blood flow in order to increase the pulmonary circulation and oxygen saturation [

13,

14]. Hypoxia is known to stimulate the release of angiogenic factors, promoting the growth of new vessels, including APCs, to enhance oxygen delivery to the lungs [

15]. A high pulmonary vascular resistance also encourages the formation of APCs, to ensure some degree of pulmonary perfusion.

The reported prevalence of these collaterals in single ventricle patients varies between 18 to 85% [

16,

17]. APCs contribute to the development of high pulmonary pressures, which in turn imposes an additional workload and hemodynamic burden on the SV [

2,

14]. Transcatheter closure is mostly performed (using coils or occlusion devices) in patients with elevated SV end diastolic pressure or pulmonary pressure, but also prior to surgical procedures, in order to avoid massive intraoperative backflow to the pulmonary arteries [

6,

17,

18]. The effectiveness of APC closure is controversially discussed, as new collaterals are reported to be very likely to develop [

17].

In this study, we describe a cohort of SV patients that underwent the interventional closure of VVC and/or APCs. We sought to determine the differences in patients with and without VVCs or APCs closure in relation to patient characteristics, clinical course, such as length of intensive care unit (ICU) or hospital stay, hemodynamics, oxygen levels and pulmonary artery dimensions.

4. Discussion

In this single-center retrospective study of 135 patients with single ventricle physiology undergoing staged Fontan palliation, we compared anatomical and clinical outcomes between patients with and without interventional closure of collateral vessels. We found that: (1) veno-venous collaterals (VVCs) and aortopulmonary collaterals (APCs) were frequent findings; (2) their closure was not associated with improved pulmonary artery growth or postoperative outcomes; and (3) fenestration and hemodynamic status influenced the likelihood of VVC closure. These results suggest that collateral closure reflects patient-specific hemodynamic conditions, rather than serving as an isolated therapeutic target.

The wide range in the reported prevalence of collateral vessels (14–31%; 18–85%, respectively) [

6,

7,

8,

16,

17] likely reflects heterogeneity in definitions, imaging modalities, and timing of evaluation across studies. Some authors include only angiographically relevant vessels, whereas others report all collaterals identified by non-invasive imaging. Differences in patient stage and inclusion of both VVCs and APCs also contribute to the observed variability.

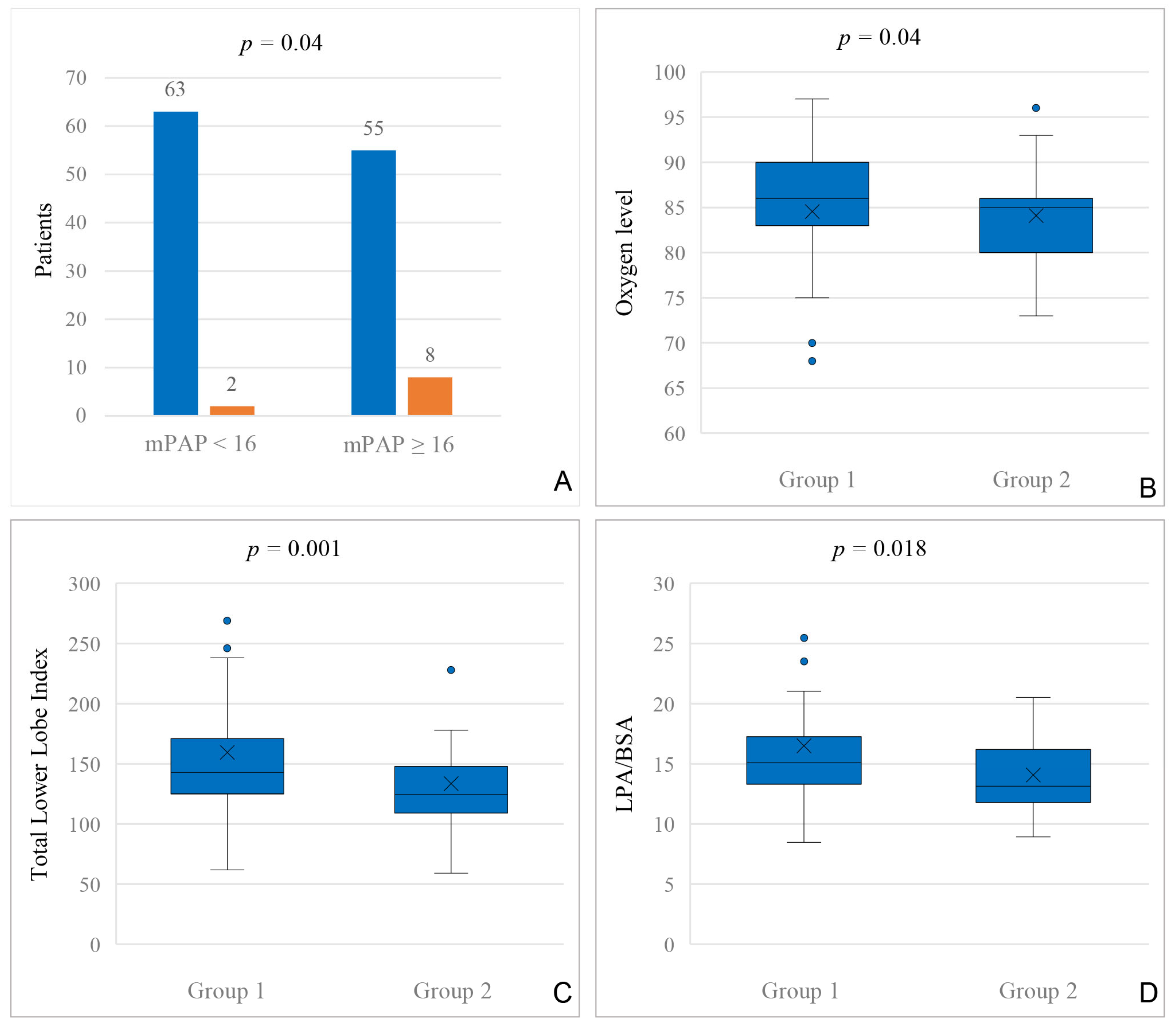

In our cohort, 25% of the patients had transcatheter VVC closure, mostly between BCPC and TCPC. As veno-venous collaterals reduce the effective pulmonary blood flow in single ventricle patients, it is interesting to see their effect on pulmonary artery growth. In our cohort, patients who underwent VVC closure at any time had a lower Nakata index before BCPC compared to patients without VVC closure. Before TCPC, we could not find a difference in Nakata indices in patients with and without VVC closure, but it is of note that in this cohort, stenting of the central PAs between BCPC and TCPC was frequent [

23]. In fact, before TCPC, we found a difference in the total lower lobe index (LLI), which bypasses the possible bias generated by a central PA stent. Additionally, there are studies suggesting the use of LLI as a more appropriate measure of pulmonary artery growth, especially after BCPC [

24]. As Poterucha et al. discussed, one of the reasons for the formation of veno-venous collaterals can be an anatomical obstruction leading to redirection of the blood flow and formation of VVCs to maintain adequate circulation [

6]. In our cohort, we found a significantly lower LPA/BSA index in patients with VVC closure, both before BCPC and TCPC. LPA/BSA is more likely to determine single left-sided pulmonary artery obstructions, as it is calculated—other than the Nakata index—by using only the left pulmonary artery cross sectional area. This indicates a former anatomical, post-surgical, or hemodynamical obstruction on the left side in patients with VVC closure.

In our cohort, the VVCs most frequently occurred unilaterally in the range of the left venous arch. It is important to understand that left-sided VVCs most likely form because of various pre-existing embryologic venous channels, which anatomically occur more often on the left side.

Veno-venous collaterals form in situations with an elevated trans-pulmonary gradient [

5] being an expression of a malfunction in the passive pulmonary blood flow after BCPC or TCPC. They thus might form as some sort of natural fenestration [

6]. We could not find general hemodynamic differences between patients with and without VVC closure, neither before BCPC nor before TCPC; however, the concomitant use of Sildenafil in a large proportion of patients may have influenced these findings. Our findings are congruent to recently published data from Nguyen Cong et al. [

5], who describe similar hemodynamics before TCPC in their cohort of 635 patients with and without veno-venous collaterals.

Sugiyama et al. describe a connection of higher mean pulmonary artery pressure and the diameter of the veno-venous collaterals in patients after TCPC [

11]. Interestingly, in our cohort before BCPC, a mPAP of 16 mmHg or higher was found more often in patients who received a VVC closure after TCPC. This might be helpful to predict patients with a higher risk for VVC development already in an early stage and suggests a compromised hemodynamical BCPC status in patients with VVC development [

25]. These patients should thus receive a fenestration during TCPC in order to reduce the pulmonary artery pressure and prevent the subsequent formation of VVCs.

Furthermore, patients with interventional closure of VVCs more often had systemic therapy with sildenafil, even if not statistically relevant, and a higher incidence of Fontan fenestration, which might be other indicators for worse hemodynamics. But the observation that patients without fenestration were less likely to undergo VVC closure should be interpreted cautiously. Fenestration was typically performed in patients with less favorable hemodynamics, and this association may therefore reflect underlying physiological differences, rather than a direct effect of VVC closure. It is conceivable that some patients with prior collateral closure experienced hemodynamic worsening, prompting the creation of a surgical fenestration as a controlled decompression pathway. Conversely, fenestration may have served as a standardized and safer substitute for spontaneous venovenous collaterals. These hypotheses remain speculative and warrant further investigation in larger, longitudinal cohorts.

Besides hemodynamic differences in patients with veno-venous collaterals, VVCs are a common cause of cyanosis in single ventricle patients [

2,

5,

10,

11]. Ngyuen Cong et al. describe significantly lower oxygen saturation before BCPC in patients that have VVCs closure after BCPC [

5], whereas in our study, we could not find different oxygen levels before BCPC for patients with VVC closure after BCPC. In the cardiac catheterization before TCPC, patients with VVC closure had significantly lower oxygen levels. This contrasts with the finding of Nguyen Cong et al., who describe no different oxygen levels pre-TCPC in patients with and without VVCs closure [

5].

Although oxygen levels before the closure of VVCs may vary, multiple studies show congruent data on the increase in oxygen levels after the embolization of veno-venous collaterals [

5,

10,

26], which was also the trend for our cohort.

Veno-venous collaterals are known to be associated with longer hospital stays. Ngyuen Cong et al. describe a correlation between VVCs and hospital stay (not ICU stay) [

5]. In our study, embolization of veno-venous collaterals was associated with longer overall hospital stay, both after BCPC and TCPC. Besides the length of hospital stay, we also found an association of VVC closure and longer intensive care length of stay, both after BCPC and TCPC. This indicates that those who were embolized are high-risk patients and possibly had borderline hemodynamics, as mean PAP was significantly higher and pulmonary artery growth was significantly lower.

In summary, the decision to close VVCs remains controversial. While closure may improve oxygen saturation and reduce right-to-left shunting, VVCs can act as natural decompression pathways in patients with elevated venous pressures. In such settings, closure may worsen hemodynamics, underscoring the need for careful, individualized assessment. Furthermore, the risk of a recurrence remains high, even after successful closure.

In our cohort, 39% of the patients underwent transcatheter closure of aortopulmonary collaterals. APC closure was more often performed after BCPC (34%) than after TCPC (9%). Beside hypoxia being the main factor for APC growth by stimulating the release of angiogenic factors [

15], anatomy or pulmonary artery size have been suggested in previous studies as other aetiologic factors for the development of APCs [

16,

27]. In our study, APC closure was predominant in single RV patients with a history of a Norwood I procedure or a comprehensive stage I and II. Also, patients in our cohort were younger when they were operated on for BCPC. Schmiel et al. examined associated factors of APC development in 430 single ventricle patients with staged palliation. They also described that APCs were associated with a previous Norwood procedure and a younger age at BCPC [

28].

The presence of aortopulmonary collaterals results in a left-to right shunt with a volume load of the pulmonary arteries and the systemic ventricle [

2]. Thus, it has been suggested that the presence of APCs might lead to an elevation of PA pressure [

29,

30]. Nevertheless, there are also studies that show no difference in hemodynamic parameters in association with aortopulmonary collateral formation [

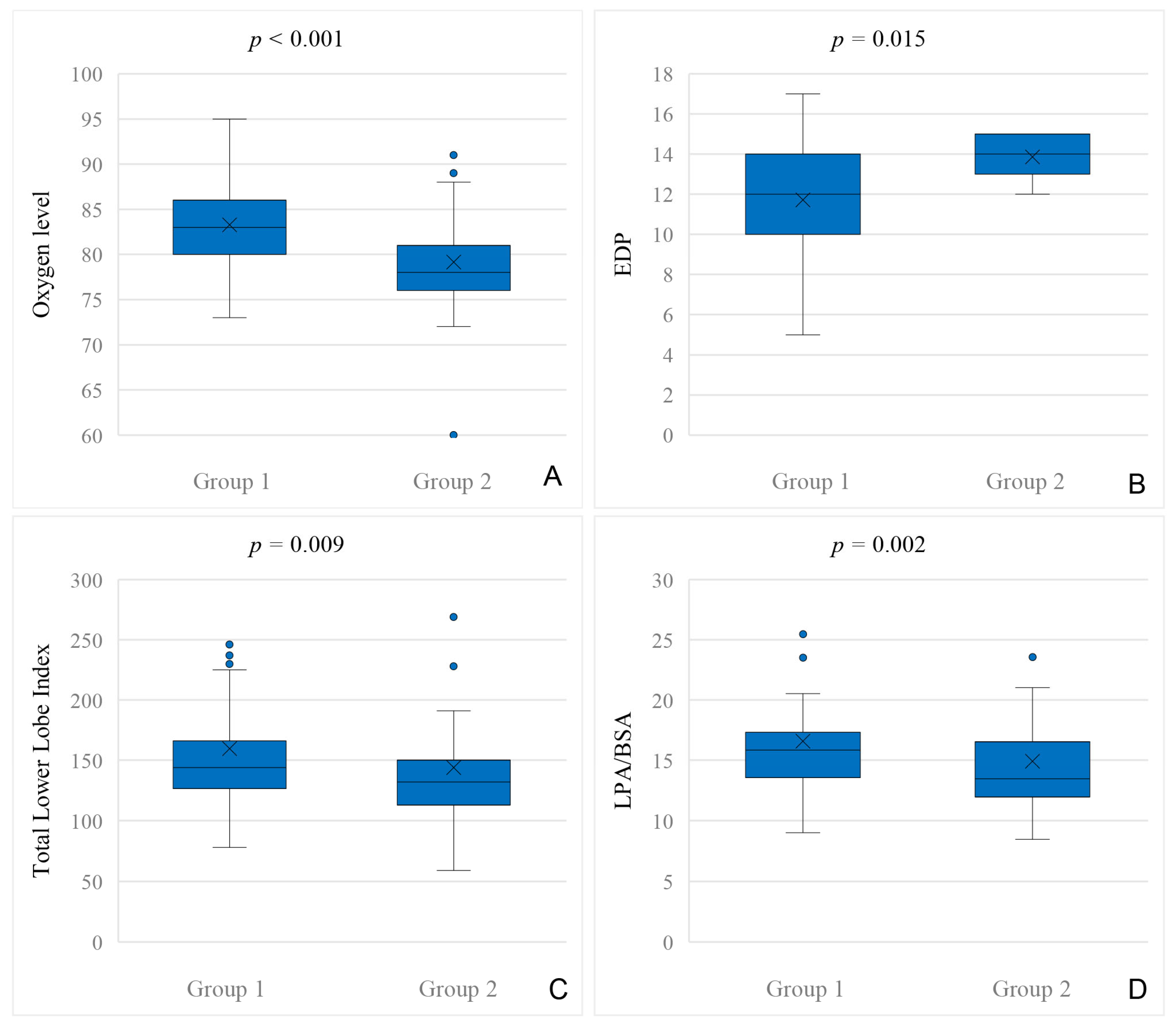

31]. We could not find general hemodynamic differences between patients with and without APC closure, neither in cardiac catheterization before BCPC nor before TCPC. The only hemodynamic difference we could find in our data was a higher EDP before TCPC in patients who underwent APC closure after TCPC. Thus, a higher EDP before TCPC might indicate a higher risk for developing APCs after TCPC.

Patients with APC closure had significantly lower oxygen levels prior to BCPC, which is congruent to the findings of Schmiel et al., who describe lower oxygen saturation at Norwood I hospital discharge as an independent risk factor for the development of APCs in HLHS patients [

31]. Although, the comparison between this study and our data should be interpreted with caution, both measurements reflect the patient’s condition at a similar stage of single ventricle palliation, provided that no supplemental oxygen was given prior to catheterization.

Although most transcatheter APC closures were performed in patients after BCPC, we could not find a difference in the length of ICU stays after BCPC. Nevertheless, there was an association with longer ICU and hospital stays after TCPC and hospital stays after BCPC. Interestingly, the patients who underwent APC closure after BCPC also had a longer ICU and hospital stay after TCPC. These results might indicate that patients with APCs before TCPC are especially high-risk patients with impaired pulmonary artery perfusion, due to preexistent compromised hemodynamics and reduced pulmonary artery growth. Osawa et al. similarly concluded in their study published in 2023 that there is a correlation between aortopulmonary collaterals before TCPC and prolonged chest tube duration and chylothorax [

32]. Also, Grosse-Wortmann et al. describe a correlation between aortopulmonary collaterals and the duration of hospital stay [

30]. On the contrary, our results are different to recently published data by Schmiel et al., who describe no difference in ICU stay after TCPC in patients who received interventional closure of APCs before TCPC [

28].

The clinical relevance of APCs can be related to their interplay with PA growth, which is a key factor in the outcome of SV patients [

23]. Our understanding is that aortopulmonary collaterals form in order to increase pulmonary blood flow [

13]. They are known to be associated with insufficient pulmonary vessel growth [

28], either because the presence of APCs prevent adequate antegrade perfusion or PA growth was insufficient in the first place and APC formation occurred. The results of our study support this hypothesis, as we found significantly smaller pulmonary arteries in patients who underwent transcatheter APC closure before TCPC compared to the patients who did not. Interestingly, we could not find a difference in pulmonary vessel growth before BCPC. Again, these results are congruent to recently published data: Staehler et al. describe a correlation of aortopulmonary collaterals with a lower pulmonary artery index before TCPC, but this group could not find a significant correlation of these markers at the time before BCPC [

14]. Latus et al. have described similar results, as they found a correlation of smaller pulmonary arteries and aortopulmonary collateral flow [

33].

Staehler et al. conclude that before BCPC, pulmonary arterial flow might be determined by anatomical features, such as the size of the aortopulmonary shunt or pulmonary stenosis, rather than the pulmonary artery size itself. They conclude from their data that after BCPC, as the passive blood flow via SVC becomes the only pulmonary blood flow, PA size might then become a representative marker for the development of APCs [

14]. Our study results support this hypothesis. We also found a correlation of surgical/anatomical features, such as the previously mentioned correlation of a Norwood I or a comprehensive stage I and II procedure with a higher prevalence of APC closure (as explained above). It therefore might be an important factor that PA size is more helpful to predict the development of aortopulmonary collaterals in patients after BCPC, rather than before.

Limitations

This study is limited by its retrospective and not-randomized, single-center design. The time of development for veno-venous or aortopulmonary collaterals may differ from the time of its transcatheter embolization. Additionally, there is a lack of incorporation and comparison of patients with collateral vessels, where transcatheter closure of collateral vessels was not performed, as the comparison was not based on the occurrence but rather on the interventional embolization of the collateral vessel. The follow-up data after TCPC is relatively short and thus, there is a lack of understanding of the effect of collateral vessel closure in terms of long-time outcome. Longitudinal analysis of hemodynamic trends and their relationship with clinical outcomes would provide valuable additional insights and therefore should be observed in future studies. The comparison of our data with other publications is limited, as indications for interventional closure of VVCs or APCs are individual and vary from center to center.