Abstract

Background: This paper aims to conduct an umbrella review of the effects of physical activity programmes for older adults (aged 70 and above). Methods: Comprehensive literature searches were conducted in MEDLINE, PubMed, EMBASE, PsychINFO, and Cochrane Library databases for English SRs. Inclusion criteria were systematic reviews that included randomised controlled trials examining physical activity interventions in older adults. The data extracted were participant characteristics, physical activity interventions, and outcomes examined. A synthesis of results was conducted using the PRISMA guidelines, and the quality of the studies was assessed using the Assessment of Multiple Systematic Reviews-2 (AMSTAR-2). Results: Ten systematic reviews on 186 research articles were included. The AMSTAR-2 revealed that 4 out of 10 reviews were of high quality and 1 out of 10 were of moderate quality. The study samples in each systematic review ranged from 6 to 1254 participants. The total overall sample size for the 10 included studies was 22,652 participants. Across the included reviews, there was mixed evidence on whether physical activity interventions could improve outcomes in older adults across various settings. Conclusions: Sample sizes and findings in each included systematic review varied. The findings of this review emphasise the importance of physical activity as a vital component in maintaining and enhancing health, as well as combating poor health as we age. It also highlights the need for a deeper understanding of the specific physical activity requirements for those aged 70 and above. Future systematic reviews may focus on streamlined reporting of dosing of physical activity and specific intervention types, such as group versus single.

1. Introduction

Today, people live longer than they did in previous decades, thanks to advances in healthcare and improved survival rates. By 2050, one in four people will be over 65 [1], and by 2074, the number of people over 80 is projected to triple [2]. As the population ages, quality of life, mental and physical health, and cognitive function are important factors. The growing ageing population has critical societal and economic considerations, particularly regarding public health. The shift in population ageing began in higher-income countries, such as Japan, and is now being experienced in low- and middle-income countries as well [1,3]. The World Health Organisation and the UN Decade of Ageing have emphasised the importance of active ageing by promoting healthy ageing, lifelong learning, financial security, and active participation in society. However, maintaining physical and mental health as we age can bring challenges [3].

Physical activity is a vital component of healthy ageing. Evidence has established that regular physical activity is essential for maintaining the physical and mental health of older adults [4,5,6,7]. Physical activity can be a protective factor for non-communicable diseases such as diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, and certain cancers [8,9]. The health benefits can also reduce the risk of falls, improving cognitive function and immune response [10,11]. Older adults must adhere to the recommended physical activity guidelines for optimal effects. The World Health Organisation [12] recommends at least 150–300 min of moderate-intensity or 75–150 min of vigorous-intensity activity per week for older adults. As the population ages, physical inactivity levels generally increase in men and women [12]. It is estimated that globally, 42% of older adults are not meeting the recommended levels of physical activity, and inactivity levels are twice as high in high-income countries compared to low-income countries [12]. Previous research has indicated that as we age, several issues can develop that may impact one’s level of physical activity and mental health, fragility, cognitive abilities, socioeconomic status, and location/home setting [3,8,13,14,15,16].

Several systematic reviews and meta-analyses have investigated physical activity interventions across several populations [17,18,19,20]. To our knowledge, no rapid umbrella review on the effects of physical activity programmes for older adults (aged 70+) has been published. Therefore, to synthesise and evaluate the available evidence, we conducted an umbrella review of systematic reviews that assessed physical activity interventions in older adults.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Structure of Umbrella Review

An umbrella review is a systematic collection and evaluation of several systematic reviews and meta-analyses [21]. To support our evidence on associations, we sought to collect information from systematic reviews that involved randomised controlled trials. We compared results from each systematic review and meta-analysis, which provided quantitative data. This umbrella review adhered to the JBI guidelines where applicable [22], the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews (PRISMA) guidelines [23] and the protocol was registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (Prospero registration number: CRD42024521063).

2.2. Search Strategy

LB searched Ovid Medline, PubMed, Web of Science, Embase, Scopus, and EBSCOhost (PsycINFO, CINAHL) from 2022 to 2024. The search was conducted between May and June 2024. Search terms are listed in the Supplementary material (Table S1). The search strategy was limited to articles published in the English language only. The reference lists of the included studies were searched and tested against the inclusion criteria to find any additional potential studies. Following the removal of duplicates, titles and abstracts were screened for eligibility by two authors, RN and LB. A third author was available to resolve discrepancies when required (ROS).

2.3. Eligibility Criteria

A study was considered for this rapid review if it met the following inclusion criteria (a) investigated physical activity programmes in older adults aged 70 and older; (b) investigated physical activity programmes in older adults where average age > 70 years old and (c) included an intervention programme that included only physical activity as the intervention component. Excluded studies were those which (a) included participants from outside the included age bracket (average age is < 70 years old); (b) were published in languages other than English; (c) were conference abstracts, study protocols, theses or dissertations; (d) were opinion pieces (e) were studies without a relevant population group, i.e., staff reporting how programmes worked; (f) qualitative papers for programme evaluation; (g) were studies developing interventions without participants; (h) secondary analysis papers and (i) studies published before 2022.

2.4. Selection of Reviews

Database searches were exported into Excel, and duplicates were removed. Title, abstract and full-text screening were conducted. A pool of three reviewers assessed the eligibility of the primary studies. The two reviewers discussed and attempted to resolve disagreements; a third reviewer intervened when a consensus could not be reached. The PRISMA guidelines will be adhered to improve reporting transparency (Table S2). Data was extracted using a standardised Excel form by two reviewers. A third reviewer verified the completeness of the extracted data, and a third reviewer resolved any discrepancies or disagreements. The information extracted included type of study, number of participants, outcome measures, details on the intervention (setting, duration, frequency, providers/resources, theoretical framework, content, and control), study length, significant findings, and risk of bias.

2.5. Methodological Quality Assessment

The Assessment of Multiple Systematic Reviews version 2 (AMSTAR2) checklist, comprising 16 items, was used by two reviewers (RN and ROS) to independently assess the quality of the methods reported in the studies (e.g., comprehensive search strategy, risk of bias, heterogeneity, etc.). This valid and reliable tool includes ratings for quality of the study design, method of analysis, reporting of results, and risk of bias [24]. The AMSTAR 2 score is categorised as high in studies that have no or one non-critical weakness, moderate with more than one non-critical weakness, low when the study has only one serious flaw without or with non-critical weaknesses, and critically low when a study has more than one essential flaw without or with non-critical weaknesses. Discrepancies between the AMSTARS 2 scores for the articles were resolved by discussion with a third reviewer (LB). Evaluating individual components within the reviews was beyond the scope of this umbrella review.

2.6. Data Extraction and Synthesis

Two reviewers extracted the data independently. For each eligible review, we extracted the key study characteristics, including authors, year of publication, journal, population, and outcome examined. We recorded a summary of the appraisal methods and interpretations of their findings. The extracted data were synthesised to address the study’s aims. The data were compiled into a single Microsoft Excel spreadsheet (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA). Results were summarised through descriptive statistics. Due to different outcome measures of each included study, no statistical comparison was completed in this umbrella review.

2.7. Deviations from Registered Protocol

Some changes were made to the registered protocol of Prospero (CRD42024521063), and the protocol was updated. This was due to the number of initial search results. The initial protocol examined primary RCTS investigating physical activity interventions in older adults between 2014 and 2024. The decision was made to change the rapid review to a rapid umbrella review on systematic reviews from 2022 to 2024.

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

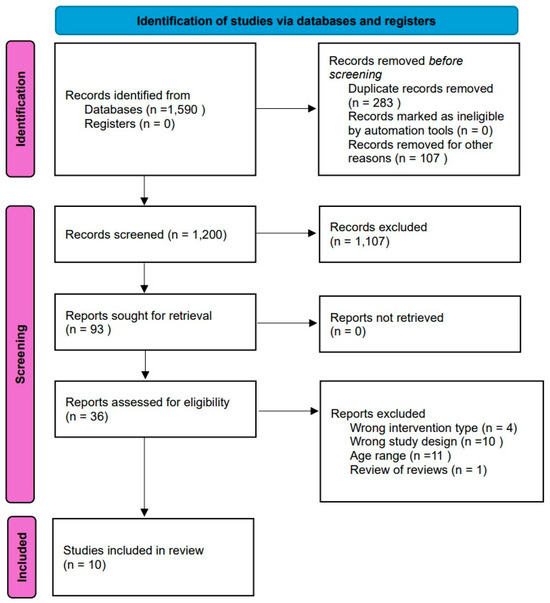

Following the initial database searches, 1590 articles were identified using the search strategy (Figure 1). Duplicates were removed, leaving 93 articles. Titles and abstracts were screened, and 57 articles were removed, leaving 36 articles for full-text review. A total of 26 studies were excluded from the review (Table S3). 10 studies met the inclusion criteria and were included within the rapid umbrella review. Review findings will be discussed based on the PICO search strategy (Population, Intervention, Comparison, and Outcome) [25].

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

3.2. Characteristics of Included Systematic Reviews

The 10 included studies comprised 10 systematic reviews, 8 of which included a meta-analysis (Table 1). Studies were published between 2022 and 2024, encompassing 186 research articles. The study samples in each systematic review ranged from 6 to 1254 participants. The total overall sample size for the 10 included studies was 22,652 participants. All studies had an average age of more than 70 years. Studies examined: fear of falling in community-dwelling older adults [26,27,28], sedentary older adults [29], older adults after hip fractures [30], frail older adults [31], older adults living in LTI and diagnosed with dementia [32], older adults with a clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease [33], older adults with dementia [34] and older adults with cognitive or without cognitive impairment [35]. While each systematic review examined physical activity interventions, they all focused on how physical activity impacted other health-related outcomes. Six of the studies examined cognition or dementia [27,29,32,33,34,35], three studies examined falls, frailty, or bone conditions (e.g., fractures) [26,30,31], and one examined generic health outcomes [28]. All systematic reviews included only randomised controlled trials.

Table 1.

Review findings.

3.3. Intervention Programmes

As shown in Table 1, a range of intervention strategies were used within the included systematic reviews. The most common type of exercise intervention was multicomponent with a range of balance, resistance and aerobic exercises (n = 6) [26,28,29,30,32,33], two involved Tai Chi [27,34], one included rhythmic physical activity [35] and another focused on resistance bands training [31]. Interventions were either individualised or in a group setting. Some studies were conducted in community settings, at home, via video consultation, or in person. Caregivers or healthcare professionals supervised some studies; others were unsupervised. Exercise dose varied across the included systematic reviews, with the total duration of the interventions ranging from two weeks to 24 months, and from two to five times a week. Some trials included repetitive activities, with sessions lasting between 15 and 150 min. The duration of each exercise session ranged from 15 to 135 min. Interventions lasted between 4 and 96 weeks. Sessions lasted 30–150 min and were performed at a frequency of two to four times per week, at light to moderate intensity.

3.4. Outcome Measures and Study Designs

All studies included in the systematic reviews were randomised controlled trials. Outcome measures varied across studies (Table S3). The most common outcomes explored in the included systematic reviews were cognitive function, physical or motor function, or functional movement. Standard scales included Barthel Index, Mini-Mental State Examination, Montreal Cognitive Assessment, Berg Balance Scale, Geriatric Depression Scale, Walking Speed, Tinetti Assessment Tool Scale, and Timed Up and Go.

All studies used a method of quality appraisal, with some assessing the evidence using two tools. The tools used included the PEDro Scale (n = 4) [26,32,33,35], the JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist for RCT studies (n = 1) [31], and the Cochrane risk of bias tool for randomised trials (RoB-2) (n = 6) [27,28,29,30,31,34]. The quality of evidence was evaluated using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) (n = 3) [28,32,33]. A random effects model was used for all eight studies which conducted a meta-analysis [26,27,28,29,30,31,34,35].

3.5. Summary of Intervention Effects

Overall, across the 10 included studies, there were mixed results on whether physical activity interventions would improve outcomes in older adults across various community settings. There was no consistent evidence on which intervention type is the most suitable.

3.5.1. Effects on Falls, Frailty or Bone Conditions

Three studies examined fall, frailty, or bone conditions (e.g., fractures) [26,30,31]. Feng et al. [26] reported no statistically significant effect on subgroups based on type of exercise, duration of interventions, primary or secondary outcome measures, and individual- or group-based exercises. Results from this study showed an overall small to moderate effect size of exercise interventions in reducing the fear of falling.

Zhang et al. [30] reported a significant moderate improvement in overall physical function after a hip fracture compared to the non-exercise group. Meta-regression analysis revealed that the overall result was not substantial in terms of the overall function. Subgroup analysis revealed that neither aerobic nor balance exercise alone had a significant impact on overall physical function. However, the exercise intervention showed a negligible effect on mobility compared to the non-exercise group. Aerobic and resistance exercise alone showed no effect on mobility promotion, but balance exercises improved mobility.

Saragih et al. [31] reported that resistance band exercise reduced frailty after 24 weeks and reduced depression after both 12 weeks and 24 weeks. However, no significant effects were observed for frailty after 12 weeks, and no significant effects were observed for grip strength, leg strength, activities of daily living or quality of life at any time.

3.5.2. Effects on Cognition or Dementia

Six of the studies examined cognition or dementia [27,29,32,33,34,35]. Park et al. [27] reported that Tai Chi and Qigong had small effect sizes on improving cognitive and physical function. Still, no significant differences were found between the effect sizes according to the intervention duration. Zhao et al. [29] reported a significant combined effect, indicating that physical exercise (multi-component and aerobic exercises) can improve cognitive function.

Oliveria et al. [32] reported on the effects of physical exercise on physical, cognitive, and functional capacity, with 10 studies showing mixed results. Multimodal exercise programmes showed mixed results, with 1 study indicating no significant difference in functional performance or cognitive function, while another showed significant effects on functional performance. The subsequent multi-modal intervention examined quality of life and found significant improvements. High Intensity exercise interventions showed mixed results, two studies found no significant difference in depression, functionality, balance and cognitive function, and the final high intensity study indicated a significant difference, with those exercising less likely to suffer moderate/severe lesions in falls. One study looked at strengthening exercises and found significant improvements in physical function. The final intervention type was aerobic exercise programmes. One study found an initial considerable effect on physical and cognitive function, but the authors noted that this effect did not remain after 9 weeks. The final two also reported significant differences in cognitive function.

Oliveria et al. [33] reported a low level of evidence with no effect on mobility, muscle strength, postural balance, cardiorespiratory function, activities of daily living and flexibility with aerobic exercise. The authors reported that multimodal exercises with a shorter overall time offered more benefits to older adults than more extended protocols, e.g., 12 months. Liu et al. [34] reported three studies that showed significant effects on cognitive function for Tai chi interventions but no significant impact on improving physical function or depression symptoms.

Sánchez-Alcalá et al. [35] reported that among the studies assessing depression, six reported statistically significant improvements supporting the rhythmic physical activity-based intervention. In contrast, three studies, utilising the HADS reported that the intervention did not yield statistically significant improvements in this variable. In terms of anxiety, two of the included studies reported statistically significant improvements assessed using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS). Conversely, two studies did not observe any improvement in anxiety. Overall, a subgroup analysis found a statistically significant median effect favouring interventions based on rhythmic physical activity for GDS-15. The second subgroup analysis, which comprised studies using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, found a small mean effect that was not statistically significant.

3.5.3. Effects on Generic Health Outcomes

One included review examined generic health outcomes [28]. Nicolson et al. [28] reported no difference between therapeutic exercise and non-exercised comparators on self-reported physical function or performance-based physical function at follow-up. Psychosocial outcomes differed across the included studies. The Geriatric Depression Scale showed no difference in scores at follow-up for a 16-week multicomponent training, whereas a 6-month aerobic exercise programme showed significant improvements on the Philadelphia Geriatric Morale Scale. For falls, two studies reported no difference between groups, while one reported substantial reductions for all falls following a multicomponent home exercise programme. Exercise appeared to reduce the risk of mortality during follow-up.

3.6. Summary of Quality and Publication Bias

Overall, studies showed low to moderate quality of evidence with some concerns on bias levels (Table 1). Asymmetric funnel plots indicate possible publication bias [26,27]. Egger’s test was non-significant [29,31]. Egger’s test showed no apparent publication bias [30,34,35].

3.7. Critical Appraisal

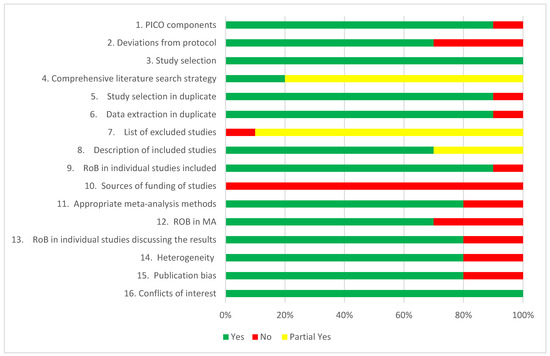

AMSTAR-2 ratings revealed four systematic reviews of high quality, one of moderate quality, and five of low quality. Of the reviews, 10% addressed conflicts of interest, 90% included PICO components, and completed study selection. Very few reviews listed the excluded studies or the reasons for exclusion. ROB assessment was addressed by 90% of the reviews. However, two studies did not conduct a meta-analysis. Publication bias was addressed by 80% of reviews. No studies detailed the funding sources of all included studies (Table 2 and Figure 2).

Table 2.

Results of the AMSTAR checklist items.

Figure 2.

A summary of results in percentage based on AMSTAR 2 Ratings.

3.8. Heterogeneity

Two studies did not assess heterogeneity, and no meta-analysis was conducted. Three studies showed no to low heterogeneity, one showed moderate heterogeneity, and four showed substantial heterogeneity.

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of Findings

This is the first umbrella review to investigate the effects of physical activity programmes for older adults aged 70 and above. Globally, there are approximately 90 million people aged 70 and above, which is expected to continue rising due to increased life expectancy and a declining birth rate. Existing evidence highlights the importance of physical activity (PA) as a vital component in maintaining and enhancing health, as well as combating poor health as we age. The findings of this review, along with the increasing number of people aged 70 and above, underscore the importance of and emphasises the need for a more comprehensive understanding of the specific PA requirements for individuals aged 70 and the benefits of physical activity programmes that incorporate aerobic, muscle-strengthening, and balance exercises at least 2 days a week to support active ageing.

Our umbrella review identified 10 systematic reviews, eight of which conducted a meta-analysis. AMSTAR-2 ratings revealed four high-quality systematic reviews, one moderate-quality review, and five low-quality reviews. Based on these AMSTAR 2 ratings, the methodological flaws in the low-quality reviews suggest that higher-quality reviews are needed. These flaws, such as failing to report sources of funding, not using a comprehensive search strategy, or not including a rationale for excluded studies, increase the risk of bias and reduce the reliability of the findings. In particular, the lack of a comprehensive search strategy may increase the risk of publication bias and omission of relevant studies. Similarly, the lack of justification for excluding the studies can undermine the objectivity of the review process. Finally, the lack of discussion around funding sources can skew meta-analysis results and introduce bias in the results or study inclusion. Overall, studies showed low to moderate quality of evidence, with some concerns regarding bias levels, as indicated by Egger’s test.

Nevertheless, findings demonstrated that the role of physical activity interventions for older adults has been explored across an impressive number of outcomes, covering a wide range of issues such as fear of falling, frailty/bone conditions, cognition or dementia, and general health outcomes such as depression. The one study on generic health outcomes [28] reported no difference between therapeutic and non-exercised comparators in physical function at follow-up; however, a significant improvement was observed with aerobic exercise in Geriatric Morale. The three studies [26,30,31] examining falls, frailty, or bone conditions reported on individual and group-based exercises, with no significant effects; however, balance and resistance exercises showed some improvement in frailty and mobility. The six studies [27,29,32,33,34,35] examining cognition or dementia showed that multicomponent or aerobic exercise, as well as rhythmic physical activity interventions, resulted in improvements in cognitive function, suggesting that this type of intervention may be beneficial for individuals over the age of 70.

Across the 10 included studies, there was mixed evidence on whether physical activity interventions could improve outcomes in older adults across various settings, including home, community, and residential settings. There was no consistent evidence on which intervention type is the most suitable (e.g., multicomponent, aerobic, resistance). However, studies on aerobic exercises have suggested significant improvements in physical or cognitive function [29,30,32], but the evidence is inconclusive regarding the duration of this effect. Additionally, the heterogeneity of the included reviews was moderate to high, indicating variability in the intervention effects among the studies. Therefore, significant differences could be overlooked or underestimated. We have presented the results for different groups of the older adult population with cognitive impairments, frailty, or just living in a community dwelling. These findings could be valuable for developing and planning activity programmes and interventions for older adults in future research, including an increased focus on muscle strengthening activities [36]. Overall, due to the variability of the evidence and the level of detail included, the results are inconclusive, and unfortunately, the findings do not provide a definitive conclusion.

4.2. Practical Implications and Future Research

This rapid umbrella review provides a first attempt at synthesising reviews on physical activity interventions for adults aged 70 and above. The review could serve as a helpful starting point for future research or an evidence base to inform the development of practice and policy. Our review highlighted several gaps within the current literature on physical activity programmes for adults aged 70 and older. The review highlights the need for high-quality RCTs evaluating the effects of physical activity programmes for older adults aged 70+ and identifies the most suitable intervention for this age group. Future randomised controlled trials and systematic reviews should examine the long-term effects of physical activity on older adults, the impact of physical activity on their loneliness and cognitive function, and focus on which types of intervention programmes work best in this age group, as well as whether group or individual activities yield different results. Very few of the included studies within the systematic reviews discussed the intensity in detail; therefore, intensity should be examined further. While research with older adults can be challenging, tackling these and moving forward with research is essential.

4.3. Strengths and Limitations

Conducting an umbrella review on physical activity programmes for older adults (aged > 70 years) has many strengths and limitations. A rapid umbrella review is a timely approach, with the results of this review providing relevant evidence that can be used to strengthen public health policies and systems for older adults. Umbrella reviews are beneficial as they are a valuable research resource involving a systematic and standardised assessment of evidence in a broad area of research [21,37].

A strength of the review conducted was adhering to the review protocol, which also increased the likelihood of capturing all relevant studies through a solid search strategy across electronic databases. The strict criteria in the final selection of the searched literature, along with adherence to the registered protocol, ensured a high-quality methodology. The data screening, extraction, and quality assessment were conducted by two reviewers, with any disagreements resolved by a third reviewer. We critically appraised the evidence in each included systematic review and explored levels of heterogeneity across the included studies.

Several limitations should be acknowledged in this umbrella review, as the original studies have limitations and a paucity of data, with the quality of evidence dependent on the quality of the reviews [21,37]. The inclusion of low-quality studies may also be limiting due to their impact on the credibility of the results. The systematic reviews also varied significantly in their outcome measures, making comparisons challenging. Another limitation of the review is that the included articles were primarily studies published in English, potentially missing relevant articles in other languages. Given the growing evidence base for physical activity interventions and research on older adults in countries such as Spain, China, or Japan, future reviews should be conducted with additional searches for non-English publications. No statistical analysis was performed due to the range of outcomes and types of interventions included, which would make comparison challenging through this method.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, although physical interventions in older adults have been extensively studied for several outcomes and show promise, definitive and conclusive findings cannot be drawn from this review, as the results are not yet definitive and remain inconclusive. The findings of this review, along with the scarcity of studies in the population aged 70 and above, underscore the need for more high-quality randomised controlled trials (RCTs) examining the impact of physical activity on health outcomes as we age. Furthermore, this review emphasises the need for a more comprehensive understanding of the specific PA requirements for individuals aged 70 and above. Based on these AMSTAR 2 ratings, the methodological flaws in the low-quality reviews suggest that higher-quality reviews are needed. In undertaking this review, it became evident that connected factors, such as social isolation, loneliness, and nutrition, are underrepresented in RCTs within the 70+ population, and how physical activity programmes can impact these critical risk factors for active and healthy ageing. Future research should also examine the broader implementation of such programmes.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/geriatrics10040098/s1, Table S1: Suggested search terms. Table S2: PRISMA checklist. Table S3: Excluded Studies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.O., L.B. and R.D.N.; methodology, L.B. and R.D.N.; validation, R.O., L.B. and R.D.N.; formal analysis, R.D.N. and R.O.; investigation, R.O., L.B. and R.D.N.; data curation, R.O., L.B. and R.D.N.; writing—original draft preparation, R.O., L.B. and R.D.N.; writing—review and editing, R.O., L.B. and R.D.N.; visualisation, R.O., L.B. and R.D.N.; supervision, R.O.; project administration, L.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

This study did not create or analyse new data, and data sharing does not apply to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- United Nations. Ageing. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/global-issues/ageing (accessed on 26 October 2022).

- United Nations Population Fund. Ageing. Available online: https://www.unfpa.org/ageing (accessed on 15 December 2024).

- World Health Organisation. Ageing and Health. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241565042/ (accessed on 14 November 2024).

- Izquierdo, M.; Singh, M.F. Promoting resilience in the face of ageing and disease: The central role of exercise and physical activity. Ageing Res. Rev. 2023, 88, 101940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, M.Y.; Ou, K.L.; Chung, P.K.; Chui, K.Y.; Zhang, C.Q. The relationship between physical activity, physical health, and mental health among older Chinese adults: A scoping review. Front. Public Health 2023, 10, 914548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organisation. Promoting Physical Activity for Older People. A Toolkit for Action. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240076648 (accessed on 14 November 2024).

- Langhammer, B.; Bergland, A.; Rydwik, E. The importance of physical activity exercise among older people. BioMed Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 7856823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organisation. Prevalence of Insufficient Physical Activity. Available online: http://www.who.int/gho/ncd/risk_factors/physical_activity_text/en/ (accessed on 14 November 2024).

- Cunningham, C.; O’Sullivan, R.; Caserotti, P.; Tully, M.A. Consequences of physical inactivity in older adults: A systematic review of reviews and meta-analyses. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2020, 30, 816–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herring, M.P.; Puetz, T.W.; O’Connor, P.J.; Dishman, R.K. Effect of exercise training on depressive symptoms among patients with a chronic illness: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arch. Intern. Med. 2012, 172, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Payette, H.; Gueye, N.D.; Gaudreau, P.; Morais, J.A.; Shatenstein, B.; Gray-Donald, K. Trajectories of physical function decline and psychological functioning: The Quebec longitudinal study on nutrition and successful aging (NuAge). J. Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2011, 66 (Suppl. 1), i82–i90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organisation. Physical Activity. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/physical-activity (accessed on 14 November 2024).

- World Health Organisation. Global Levels of Physical Inactivity in Adults: Off Track for 2030. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240096905 (accessed on 14 November 2024).

- Behr, L.C.; Simm, A.; Kluttig, A.; Grosskopf, A. 60 years of healthy aging: On definitions, biomarkers, scores and challenges. Ageing Res. Rev. 2023, 88, 101934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bantham, A.; Ross, S.E.; Sebastião, E.; Hall, G. Overcoming barriers to physical activity in underserved populations. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2021, 64, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lebrasseur, A.; Fortin-Bédard, N.; Lettre, J.; Raymond, E.; Bussières, E.L.; Lapierre, N.; Faieta, J.; Vincent, C.; Duchesne, L.; Ouellet, M.C.; et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on older adults: Rapid review. JMIR Aging 2021, 4, e26474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, D.; Dlima, S.D.; Gluchowski, A.; Hall, A.; Elliott, E.; Munford, L. The effectiveness and acceptability of physical activity interventions amongst older adults with lower socioeconomic status: A mixed methods systematic review. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2024, 21, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, B.; Olds, T.; Curtis, R.; Dumuid, D.; Virgara, R.; Watson, A.; Szeto, K.; O’Connor, E.; Ferguson, T.; Eglitis, E.; et al. Effectiveness of physical activity interventions for improving depression, anxiety and distress: An overview of systematic reviews. Br. J. Sports Med. 2023, 57, 1203–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinheiro, M.B.; Oliveira, J.; Bauman, A.; Fairhall, N.; Kwok, W.; Sherrington, C. Evidence on physical activity and osteoporosis prevention for people aged 65+ years: A systematic review to inform the WHO guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2020, 17, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devereux-Fitzgerald, A.; Powell, R.; Dewhurst, A.; French, D.P. The acceptability of physical activity interventions to older adults: A systematic review and meta-synthesis. Soc. Sci. Med. 2016, 158, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belbasis, L.; Bellou, V.; Ioannidis, J.P. Conducting umbrella reviews. BMJ Med. 2022, 1, e000071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aromataris, E.; Fernandez, R.; Godfrey, C.; Holly, C.; Khalil, H.; Tungpunkom, P. Chapter 10: Umbrella reviews. In JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; JBI: Adelaide, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shea, B.J.; Reeves, B.C.; Wells, G.; Thuku, M.; Hamel, C.; Moran, J.; Moher, D.; Tugwell, P.; Welch, V.; Kristjansson, E.; et al. AMSTAR 2: A critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ 2017, 358, j4008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, J.P.; Altman, D.G.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Jüni, P.; Moher, D.; Oxman, A.D.; Savović, J.; Schulz, K.F.; Weeks, L.; Sterne, J.A.C.; et al. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2011, 343, d5928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, C.; Adebero, T.; DePaul, V.G.; Vafaei, A.; Norman, K.E.; Auais, M. A systematic review and meta-analysis of exercise interventions and use of exercise principles to reduce fear of falling in community-dwelling older adults. Phys. Ther. 2022, 102, pzab236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, M.; Song, R.; Ju, K.; Shin, J.C.; Seo, J.; Fan, X.; Gao, X.; Ryu, A.; Li, Y. Effects of Tai Chi and Qigong on cognitive and physical functions in older adults: Systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression of randomized clinical trials. BMC Geriatr. 2023, 23, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicolson, P.J.; Duong, V.; Williamson, E.; Hopewell, S.; Lamb, S.E. The effect of therapeutic exercise interventions on physical and psychosocial outcomes in adults aged 80 years and older: A systematic review and Meta-analysis. J. Ageing Phys. Act. 2021, 30, 517–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, L.; Song, Z.; Di, T.; Dong, X.; Song, X.; Han, X.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, B.; et al. Physical activity and cognition in sedentary older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2022, 87, 957–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Butts, W.J.; You, T. Exercise interventions, physical function, and mobility after hip fracture: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Disabil. Rehabil. 2022, 44, 4986–4996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daryanti Saragih, I.; Yang, Y.P.; Saragih, I.S.; Batubara, S.O.; Lin, C.J. Effects of resistance bands exercise for frail older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled studies. J. Clin. Nurs. 2022, 31, 43–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Oliveira, E.A.; Correa, U.A.; Sampaio, N.R.; Pereira, D.S.; Assis, M.G.; Pereira, L.S. Physical exercise on physical and cognitive function in institutionalized older adults with dementia: A systematic review. Ageing Int. 2024, 49, 700–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braz de Oliveira, M.P.; Moreira Padovez, R.D.; Serrão, P.R.; de Noronha, M.A.; Cezar, N.O.; Andrade, L.P. Effectiveness of physical exercise at improving functional capacity in older adults living with Alzheimer’s disease: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Disabil. Rehabil. 2023, 45, 391–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, D.M.; Wang, L.; Huang, L.J. Tai Chi Improves Cognitive Function of Dementia Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Altern. Ther. Health Med. 2023, 29, 90. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- NSanchez-Alcala, M.; Aibar-Almazan, A.; Afanador-Restrepo, D.F.; Carcelen-Fraile, M.D.; Achalandabaso-Ochoa, A.; Castellote-Caballero, Y.; Hita-Contreras, F. The impact of rhythmic physical activity on mental health and quality of life in older adults with and without cognitive impairment: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 7084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, M.A. Exercise and osteoporotic fracture prevention. Part 2: Prescribing exercise. Med. Today 2007, 8, 31–41. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, G.J.; Kang, H. Introduction to umbrella reviews as a useful evidence-based practice. J. Lipid Atheroscler. 2022, 12, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).