Simple Summary

Toxoplasmosis in buffaloes represents an important One Health concern due to its combined economic, environmental, and public health implications. Toxoplasma gondii, the causative agent of toxoplasmosis, can induce severe clinical consequences in infected animals and humans. In Egypt, water buffaloes are used as a major source of milk and meat production. This study revealed the existence of T. gondii antibodies in 7% of the tested buffaloes from Sohag governorate, southern Egypt. We also found the season was a predisposing factor for seropositivity for T. gondii, as the highest seropositivity was recorded in spring (10.7%). T. gondii infection in buffaloes can pose a health risk to people—infections could be passed on by consuming raw milk or meat. This study presents novel and valuable information on the seroprevalence of T. gondii in Sohag, southern Egypt. These findings contribute to regional, data-driven surveillance efforts and underscore the value of buffaloes as sentinel animals for environmental contamination. Additionally, our study contributes to the regional surveillance of T. gondii as a zoonotic pathogen and minimizes its risks in the veterinary and public health sectors.

Abstract

Toxoplasmosis is a globally prevalent protozoan parasitic disease of livestock, among others, with significant zoonotic potential. This study aimed to assess the seroprevalence of Toxoplasma gondii antibodies in serum samples from water buffaloes (Bubalus bubalis) in Sohag governorate, Upper Egypt. In addition, several factors related to animals, management, and environment were analyzed to identify the risk factors for T. gondii infection. A cross-sectional epidemiological approach was employed, with samples collected from various locations across the region and tested using a commercially available indirect enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (iELISA). Animal and environmental factors were evaluated to identify potential risk factors for the disease. The overall seroprevalence of T. gondii among the tested buffaloes was 7% (24/342). Seasonal variations were observed, with the highest seropositivity recorded in spring (10.7%; 11/103), followed by autumn (8%; 2/25), summer (5.6%; 7/125), and winter (2.2%; 2/89). High seropositivity was detected in aborted females, at 19% (4/21), and in repeated breeders, at 10.5% (4/38), in relation to buffaloes showing anestrus (no positive cases), although the differences were not statistically significant. Our findings suggest that T. gondii is endemic in Sohag, with water buffaloes serving as sentinel animals for the disease. The spring season appears to be a risk factor for infection. Further studies are needed to assess the potential risk to humans, particularly regarding the consumption of raw or undercooked buffalo meat infected with T. gondii.

1. Introduction

Farmers rely on buffalo for their milk, meat, and long productive life [1]. Toxoplasmosis, caused by Toxoplasma gondii, is a widespread protozoan parasitic disease. T. gondii is highly adaptive and can persist long-term in tissue cysts within hosts. Felids are the definitive hosts, while various animals and humans serve as intermediate hosts [2]. Anti-T. gondii antibodies have been recorded in all countries and regions of the world and in most animal species [3]. Transmission occurs primarily through ingestion of contaminated food or water containing sporulated oocysts, meat containing tissue cysts, and less frequently via tachyzoites crossing the placenta, causing congenital toxoplasmosis. Approximately one-third of the global human population [2] and a quarter of livestock and poultry are infected [4].

T. gondii was first recognized as a cause of abortion in sheep in 1957, and has since been recognized as serious risk to pregnant animals, potentially causing abortion, mummification, stillbirth, or embryonic death. T. gondii is a major foodborne parasite causing toxoplasmosis, often transmitted by consuming raw/undercooked meat containing tissue cysts or unwashed produce contaminated with oocysts from cat feces [2]. It poses severe risks to pregnant women (congenital infection) and immunocompromised people [2]. In addition, T. gondii is a significant occupational pathogen, particularly for individuals in close contact with animals, raw meat, or contaminated soil. Prevention requires thorough cooking or freezing of meat, washing produce, and pasteurization of milk [2,5]. The only available vaccine, Toxovax® (Intervet), reduces T. gondii-induced abortion in sheep [6].

In water buffalo, T. gondii has been linked to longer calving-to-conception intervals due to early embryonic death and resorption [7]. T. gondii in buffalo poses a potential public health risk as a food-borne pathogen through the consumption of infected meat (cysts) [8] and milk (tachyzoites) [9]. The serological prevalence of toxoplasmosis in buffalo ranges from 0% to 87.79% [10], with regional variations: 0% in Australia, 13.43% in Asia, 20% in Europe, 28.42% in North America, 10.22% in South America, and 21.15% in Africa. The weighted global prevalence is estimated at 22.26% [11].

In Egypt, T. gondii antibodies have been detected in various animal species, with seroprevalence rates of 38.7% in sheep, 28.7% in goats, 23.6% in cattle, 22.6% in donkeys [12], and 34.4% in buffaloes [13]. In Sohag, the overall seroprevalence in domestic ruminants (cattle, buffalo, sheep, goats) is 47.9%, with buffaloes showing a higher rate of 58.6%, indicating widespread infection in Upper Egypt [14]. In Assuit, seroprevalence varies from 20% (LAT) to 74.5% (ELISA) [15], while in Giza, it is 22.5% [16]. A recent study reported a 7.4% seroprevalence in buffaloes [17].

This study aims to assess the seroprevalence of T. gondii in buffaloes across different locations in Sohag and explore risk factors related to both animal and environmental factors to help inform strategies for controlling the infection. This study provided foundational epidemiological data on the presence and seasonal distribution of T. gondii in water buffaloes in Sohag, southern Egypt, highlighting spring as a period of elevated risk.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Statement

All relevant institutional, national, and/or international guidelines pertaining to the use and care of animals were followed. This study was conducted according to instructions established by the “Research Bioethic Committee- RBC” of the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Qena University, Qena, Egypt. The protocols were approved by the Research Code of Ethics at Qena University number “VM/SVU/25(7)-07” in accordance with the OIE guidelines for animal usage and studies. Blood samples were collected after consultation with officials and animal owners.

2.2. Animal Population and Geographic Location (Study Area)

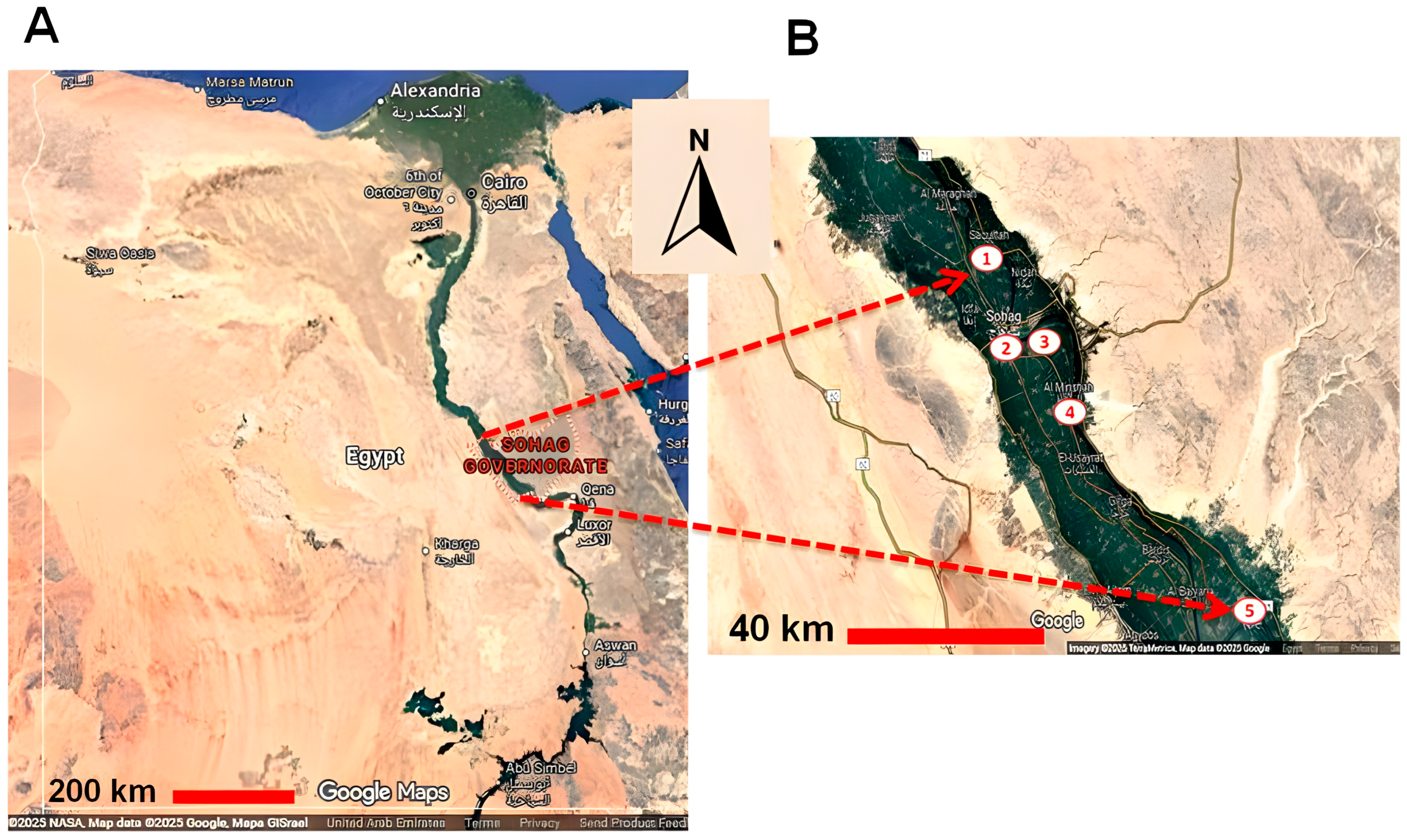

This cross-sectional study was performed from October 2020 to October 2022. A total of 342 buffalo blood samples were randomly collected from five cities located in the Nile valley in the Sohag governorate, southern Egypt. Sohag governorate is located in Upper Egypt and is rich in livestock. Five cities were chosen for this study (Sohag, El-Monsha, Akhmium, Saqulta, Dar-Elsalam). Buffaloes of different ages, sexes, locations, management types, and other factors were sampled (Figure 1). The availability of samples and owner cooperation determined the numbers and groups of tested animals.

Figure 1.

A landscape map of Egypt illustrating the cities used for sample collection in Sohag governorate. The location of Sohag governorate in upper/southern Egypt (A), and the location of cities used for sample collection, all situated in the Nile valley: 1: Saqultah, 2: Sohag, 3: Akhmim, 4: Al Minshah, 5: Dar-Elsalam (B).

2.3. Sample Collection and Serum Preparation

The jugular vein was used for blood collection via venipuncture utilizing a sterile disposable plain Vacutainer tube (Smilelab®, Stockholm, Sweden) and needle, devoid of anticoagulants. Sera were isolated from blood samples using centrifugation at 3000 rpm for 10 min. Sera were aliquoted into 1.5 mL Eppendorf tubes post-centrifugation, transported to the laboratory of Qena University (Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Qena University, Qena, Egypt) and maintained at −20 °C until utilized for ELISA testing.

2.4. Epidemiological Data

Epidemiological data were obtained by a semi-structured questionnaire distributed to animal owners to collect information on potential risk factors associated with both animals and their environment. The animal-related characteristics included age (<1 year, 1 to 3 years, >3 years), sex (female or male), body weight (<100 kg, 100 to 300 kg, >300 kg), and, for adult females exclusively, reproductive problems (yes or no). Reproductive problems were defined as abortion, recurrent breeding, and anestrus. The environmental characteristics considered included geographic location (Saqultah, Sohag, Akhmim, Al Minshah, Dar-Elsalam), sampling season (spring, summer, fall, winter), presence of cats or dogs (yes or no), and management style, as either a smallholder (5–20 animals per owner) or an individual (less than 5 animals per owner). All tested water buffaloes belonged to the local breed identified as Egyptian water buffalo breed.

2.5. Processing and Analysis of Data

All serum samples were tested for antibodies to T. gondii by iELISA using a commercial ID Screen® Toxoplasmosis Indirect Multi-Species test kit based on the P30 antigen of T. gondii (ID. Vet. Grabels, France, TOXO-MS-2P, LOT 159). Manufacturer’s instructions were followed for preparation of samples and buffers and for all testing procedures. Except for distilled water (DW), all reagents and buffers were provided in the same kit. Serum samples and controls were diluted 1:2 and added to the wells and incubated at room temperature (24 °C) for 45 min. Then, plates were washed thrice by washing buffer provided by the company after diluting 20 times by distilled water. An amount of 100 µL of conjugated antibodies (10 times diluted) was added to the wells and incubated again at RT for 30 min. After three further washes, 100 µL of substrate solution was added to the wells and they were incubated in a dark place for 15 min. Then, stop solution (100 µL) was added to all wells and the ODs of all ELISA data were read at 450 nm and quantified using an Infinite® F50 ELISA reader (Tecan Group Ltd., Mannedorf, Switzerland). The ODs obtained were used to calculate the percentage of sample (S)-to-negative (N) ratio (S/N%) for each of the test samples according to the following formula: S/N (%) = OD sample/OD negative control × 100. Samples with an S/N% more than 60% were regarded as negative, those with an S/N% between 50% and 60% were regarded as doubtful, and the test was considered positive if the S/N% was less than 50%.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

The significance of the differences in the prevalence rates and risk factors (age, sex, weight, reproductive problems, location, season, contact with cats and dogs, and management) was analyzed using Fisher’s exact test, 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) (including a continuity correction), and odds ratios (ORs) using an online statistical website www.vassarstats.net (accessed on 22 September 2025). Additionally, p-values and odds ratios were confirmed with GraphPad Prism version 5 (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA) [18].

3. Results

3.1. Seroprevalence and Associated Animal-Related Risk Factors of T. gondii in Buffaloes from Sohag

The overall seroprevalence to T. gondii in water buffalo of the Sohag governorate was 7% (24/342). Seropositivity was slightly higher in buffaloes > 3 years old (8.5%, 13/153) compared to those 1–3 years (5.5%, 9/164) and <1 year old (8%, 2/25). Males showed higher seropositivity (8%, 6/75) than females (6.8%, 18/276). For weight, buffaloes < 100 kg had the highest seropositivity (11.1%, 1/9), followed by those >300 kg (7.4%, 17/230) and 100–300 kg (5.8%, 6/103). In adult females, seropositivity was higher in aborted buffaloes (19%, 4/21) than repeat breeders (10.5%, 4/38). However, differences in sex, weight, and reproductive problems were not statistically significant (p > 0.05) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Effect of animal-related risk factors on seroprevalence of T. gondii in buffaloes.

3.2. Environmental Risk Factors of T. gondii in Buffaloes from Sohag

Seropositivity varied with the location of the buffaloes: The highest seropositivity was found in Sohag city, at 18.2% (2/11), followed by Akhmium, at 7.3% (20/273), Saquelta, at 4.5% (1/22), and Dar-Elsalam, at 3.8% (1/26), but differences were non-significant (p > 0.05). Seroprevalence of T. gondii varied by season: 10.7% (11/103) in spring, 5.6% (7/125) in summer, 2.2% (2/89) in winter, and 8% (2/25) in autumn, with a statistically significant difference between spring and winter (p = 0.022). Seropositivity was slightly higher in buffaloes with contact with cats and dogs (7.4%, 5/68) compared to those without contact (6.9%, 19/274). Additionally, smallholder management had a higher seroprevalence (10.8%, 4/37) compared to individual management (6.6%, 20/305). However, differences in contact with cats and dogs and management systems were not statistically significant (p > 0.05) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Effect of environmental factors on seroprevalence of T. gondii in buffaloes.

4. Discussion

Buffaloes act as reservoirs for many pathogens potentially affecting human health, environmental contamination, and food safety. Despite buffalo being considered a relatively resistant host, natural T. gondii infections have been reported [10]. This study aimed to determine the seroprevalence of T. gondii in water buffaloes from Sohag, southern Egypt, as a crucial step for developing prevention and control strategies in water buffaloes, a key source of milk and meat. Serological tests, particularly for IgG antibodies, are commonly used to diagnose toxoplasmosis in buffalo, as IgM persists only for a few weeks [19]. The iELISA test used in this study is highly specific, with minimal cross-reactivity, as confirmed by the manufacturer (ID. Vet, France), and is an effective diagnostic tool for various animals [20]. Our results corroborated the endemicity of T. gondii in Sohag using high numbers of water buffaloes for the first time. Season was identified as a predisposing factor of infection. As buffaloes are mainly infected by oocysts present in their food or in water, the observed seroprevalence indicates environmental contamination. Thus, humans are also at risk of infection through oocysts present on produce or in water, in addition to the potential infection risk when consuming raw milk or raw/undercooked meat of seropositive buffaloes. Pregnant women and immunocompromised individuals should especially try to avoid infection.

The T. gondii prevalence in water buffaloes was 7% (24/342). The global prevalence varies due to different parasite genotypes in different regions [21]. Our findings fall within the global range of 0–87.79% [10], aligning with studies from China (7.5%) [22], Iraq (7.4%) [23], and from Zimbabwe (5.6%) [24]. However, it was higher than studies in Brazil (1.1%) [25], India (2.9%) [26], and in the Philippines (1.9%) [27], but lower than those in Argentina (25.4%) [28], Italy (13.7%) [7], and in Mexico (30.7%) [29]. When comparing our results with studies from Egypt, our seroprevalence was similar to that reported by Selim et al. [17] but lower than studies by Farag et al. (58.6%) [14], Ibrahim et al. (8.2%) [30], Hassanain et al. (34.4%) [13], Kuraa and Malek (74.5%) [15], El-Fadaly et al. (17.1%) [31], and Ibrahim et al. (16.82%) [32]. It is higher than the rates reported by Rifaat et al. (5%) [33], and Hussein et al. (3%) [8].

We assessed various animal and environmental factors influencing T. gondii seropositivity in buffaloes. While buffaloes are generally resistant to toxoplasmosis [34], risk factors include the presence of cats, farm hygiene, and age [10]. Cats are key in the transmission and prevalence of T. gondii, shedding large numbers of oocysts in their feces [35]. In Egypt, the T. gondii prevalence in domestic cats reaches up to 97%, especially in rural areas, suggesting high environmental contamination with oocysts, putting not only livestock but also humans at risk of infection [36,37]. The high seroprevalence in Egypt is linked to this factor. Additionally, T. gondii prevalence is higher in humid, rain-prone areas, which favor oocyst sporulation [38].

Our analysis showed no significant differences in T. gondii seropositivity based on age, sex, weight, or reproductive issues. Seroprevalence typically increases with age, as older animals are more likely to have prolonged exposure to the parasite [39]. Female buffaloes, often older due to reproductive and milk production management, generally show higher seropositivity than males [40], though no significant difference was found in this study, consistent with other reports [41,42].

For body weight, seropositivity was 7.4% in buffaloes >300 kg and 11.1% in buffaloes <100 kg, both higher than in the 100–300 kg group (5.8%), but the differences were not significant. Older buffaloes (>300 kg) may have a higher infection risk due to longer exposure, while the higher seropositivity in lighter buffaloes (<100 kg), typically younger animals, may suggest vertical transmission. However, the lack of T. gondii in aborted fetuses limits the epidemiological significance of these findings [35,43].

Regarding reproductive problems, seropositivity was higher in buffaloes with a history of abortion (19%) compared to repeat breeders (10.5%), though the difference was not statistically significant. This aligns with the findings of Canada et al. [44] and Alvarado-Esquivel et al. [41]. While T. gondii is a known cause of abortion in other livestock, its link to abortion in buffaloes remains unclear, though some studies suggest it may cause reproductive issues like embryonic death and extended calving-to-conception intervals [41].

Seropositivity in our tested cities ranged from 3.8% to 18.2%, with no statistically significant differences. While location often affects T. gondii seroprevalence in bovines [12,45,46], the lack of significant differences in this study may be due to the proximity of the cities, similar management practices, and also the low sample sizes in some cities.

The seroprevalence of T. gondii was highest in spring (10.7%, p = 0.022), likely due to increased daylight, warmer temperatures, and more active behavior due to the breeding season in cats, leading to greater exposure to infections [47]. This study contrasts with others that found higher seroprevalence in summer [48] or winter [23].

Regarding contact with cats and dogs, seropositivity was similar in buffaloes with (7.4%) and without (6.9%) such contact, contrary to expectations, as cats are the definitive host of T. gondii [49]. In Egypt, cats have a high T. gondii prevalence [50], and dogs can act as mechanical carriers [51]. This result may be influenced by common management practices in Sohag, where dogs are used as guards, but the lack of seroprevalence data for cats and dogs in Sohag limits our understanding.

In Sohag, farmers generally keep female calves of buffaloes, even if they appear weak, which may lead to increased probability of the presence of diseases. Infected females may also maintain the infection via vertical transmission (no need for repeated cat contact). Furthermore, female buffaloes are more exposed to stress factors such as reproduction and milk production than male buffaloes. This may increase the probability of recurrent infections. All these factors might be responsible for the endemicity of T. gondii infection in buffaloes.

For management type, seroprevalence was higher in smallholder (10.8%) than individual management systems (6.6%), though the difference was not significant. These findings align with studies by Fereig et al. [12] in Qena and Metwally et al. [52] in Beheira, northern Egypt.

Regarding the limitations of this study, it would be beneficial to investigate the seroprevalence of T. gondii among cats and dogs present on the farms. Extending the investigation to more cities and regions from the Sohag governorate and including a higher number of buffaloes should be addressed in further studies. Such aspects would greatly help to gain more inclusive data and allow better interpretation of the results.

Our epidemiological data can serve as the foundational evidence for risk assessments of T. gondii infection in the tested animals and regions, allowing public health officials and organizations to transition from reactive measures to proactive, evidence-based risk mitigation. By analyzing the distribution and predisposing factors for the infection, our epidemiological data allows for the identification of high-risk populations, transmission pathways, and the effectiveness of potential interventions. Our study highlights the need to test raw milk or dairy products to assess whether viable T. gondii is present, and if so, to implement surveillance strategies for milk supply chains. Furthermore, the risk of transmission through consumption practices (e.g., raw or undercooked products) should be evaluated. In the meantime, public health authorities should advise farmers and consumers to pasteurize milk and to cook meat well in order to minimize the risk of infection through buffalo products.

In conclusion, toxoplasmosis in buffaloes represents an important One Health concern due to its combined economic, environmental, and public health implications. This study provides foundational epidemiological data on the presence and seasonal distribution of T. gondii in water buffaloes in Sohag, southern Egypt, highlighting spring as a period of elevated risk. These findings contribute to regional, data-driven surveillance efforts and underscore the value of buffaloes as sentinel animals for environmental contamination. Given the limited baseline information available for this region, the identified patterns can support future risk assessment and guide targeted control strategies. In the absence of effective vaccines, early detection, improved farm hygiene, and strengthened monitoring systems remain essential components of disease management. Expanded serological and molecular surveys involving larger sample sizes and multiple animal species are recommended to more accurately characterize transmission dynamics. Integrating routine testing of aborted animal cases and monitoring of definitive hosts, such as cats, would further enhance surveillance capacity. These measures, combined with improved food-safety awareness, can help reduce the potential zoonotic transmission of T. gondii within the broader One Health framework.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and design, A.O.A., C.F.F. and R.M.F.; experiments, formal analysis, and investigation, A.O.A., W.Q., C.F.F. and R.M.F.; resources and shared materials, A.O.A., W.Q., F.A.K., C.F.F. and R.M.F.; writing—original draft, A.O.A., W.Q., C.F.F. and R.M.F.; writing—review and editing, A.O.A., W.Q., F.A.K., C.F.F. and R.M.F.; project administration and funding acquisition, C.F.F. and R.M.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study did not receive any special funds.

Institutional Review Board Statement

All applicable international, national, and/or institutional guidelines for the care and use of animals were followed. The protocols were approved by the Research Code of Ethics at Qena University, number VM/SVU/25(7)-07.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We thank all veterinarians who helped in collecting blood samples and the animal owners for their cooperation in providing animals and the required data and information of each animal.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- FAO. Befs Assessment for Egypt: Sustainable Bioenergy Options from Crop and Livestock Residues; Food and Agriculture Organization: Rome, Italy, 2017; Available online: https://openknowledge.fao.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/1de76462-e838-43ed-bc57-75d33fb32ba2/content (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Dubey, J.P. Toxoplasmosis of Animals and Humans, 2nd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Dubey, J.P.; Murata, F.H.A.; Cerqueira-Cézar, C.K.; Kwok, O.C.H.; Grigg, M.E. Recent epidemiologic and clinical importance of Toxoplasma gondii infections in marine mammals: 2009–2020. Vet. Parasitol. 2020, 288, 109296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajimohammadi, B.; Ahmadian, S.; Firoozi, Z.; Askari, M.; Mohammadi, M.; Eslami, G.; Askari, V.; Loni, E.; Barzegar-Bafrouei, R.; Boozhmehrani, M.J. A Meta-Analysis of the Prevalence of Toxoplasmosis in Livestock and Poultry Worldwide. Ecohealth 2022, 19, 55–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharif, M.; Sarvi, S.; Shokri, A.; Hosseini Teshnizi, S.; Rahimi, M.T.; Mizani, A.; Ahmadpour, E.; Daryani, A. Toxoplasma gondii infection among sheep and goats in Iran: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Parasitol. Res. 2015, 114, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurr, J.; Holec-Gasior, L.; Hiszczyńska-Sawicka, E. Current status of toxoplasmosis vaccine development. Expert Rev. Vaccines 2009, 8, 791–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciuca, L.; Borriello, G.; Bosco, A.; D’Andrea, L.; Cringoli, G.; Ciaramella, P.; Maurelli, M.P.; Di Loria, A.; Rinaldi, L.; Guccione, J. Seroprevalence and Clinical Outcomes of Neospora caninum, Toxoplasma gondii and Besnoitia besnoiti Infections in Water Buffaloes (Bubalus bubalis). Animals 2020, 10, 532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussein, D.E.; Khashaba, A.M.A.; Kamar, A.M. Advanced Studies on Toxoplasma in Buffalo Meat. Alex. J. Vet. Sci. 2023, 77, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehkordi, F.S.; Borujeni, M.R.; Rahimi, E.; Abdizadeh, R. Detection of Toxoplasma gondii in raw caprine, ovine, buffalo, bovine, and camel milk using cell cultivation, cat bioassay, capture ELISA, and PCR methods in Iran. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 2013, 10, 120–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Barros, L.D.; Garcia, J.L.; Bresciani, K.D.S.; Cardim, S.T.; Storte, V.S.; Headley, S.A. A Review of Toxoplasmosis and Neosporosis in Water Buffalo (Bubalus bubalis). Front. Vet. Sci. 2020, 7, 455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shariatzadeh, S.A.; Sarvi, S.; Hosseini, S.A. The global seroprevalence of Toxoplasma gondii infection in bovine: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Parasitology 2021, 148, 1417–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fereig, R.M.; Mahmoud, H.Y.A.H.; Mohamed, S.G.A.; AbouLaila, M.R.; Abdel-Wahab, A.; Osman, S.A.; Zidan, S.A.; El-Khodary, S.A.; Mohamed, A.E.A.; Nishikawa, Y. Seroprevalence and epidemiology of Toxoplasma gondii in farm animals in different regions of Egypt. Vet. Parasitol. Reg. Stud. Rep. 2016, 3–4, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassanain, M.A.; El-Fadaly, H.A.; Hassanain, N.A.; Shaapan, R.M.; Barakat, A.M.; Abd El Razik, K.A. Serological and molecular diagnosis of toxoplasmosis in human and animals. World J. Med. Sci. 2013, 9, 243–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farag, S.I.; Cano-Terriza, D.; Gonzálvez, M.; Salman, D.; Aref, N.M.; Mubaraki, M.A.; Jiménez-Martín, D.; García-Bocanegra, I.; Elmahallawy, E.K. Serosurvey of selected reproductive pathogens in domestic ruminants from Upper Egypt. Front. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10, 1267640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuraa, H.M.; Malek, S.S. Seroprevalence of Toxoplasma gondii in ruminants by using latex agglutination test (LAT) and enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) in Assuit governorate. Trop. Biomed. 2016, 33, 711–725. [Google Scholar]

- Shaapan, R.M.; Hassanain, M.A.; Khalil, F.A.M. Modified agglutination test for serologic survey of Toxoplasma gondii infection in goats and water buffaloes in Egypt. Res. J. Parasitol. 2010, 5, 13–17. [Google Scholar]

- Selim, A.; Alshammari, A.; Gattan, H.S.; Alruhaili, M.H.; Rashed, G.A.; Shoulah, S. Seroprevalence and associated risk factors for Toxoplasma gondii in water buffaloes (Bubalus bubalis) in Egypt. Comp. Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2023, 101, 102058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fereig, R.M.; El-Alfy, E.-S.; Alharbi, A.S.; Abdelraheem, M.Z.; Almuzaini, A.M.; Omar, M.A.; Kandil, O.M.; Frey, C.F. Seroprevalence of Toxoplasma gondii in Cattle in Southern Egypt: Do Milk and Serum Samples Tell the Same Story? Animals 2024, 14, 3122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, N.; Qayyum, M. Seroprevalence and risk factors for toxoplasmosis in large ruminants in northern Punjab, Pakistan. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries. 2014, 8, 1022–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastiu, A.I.; Gyorke, A.; Villena, I.; Balea, A.; Niculae, M.; Pall, E.; Spinu, M.; Cozma, V. Comparative Assessment of Toxoplasma gondii Infection Prevalence in Romania Using 3 Serological Methods. Bull. UASVM Vet. Med. 2015, 72, 102–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertranpetit, E.; Jombart, T.; Paradis, E.; Pena, H.; Dubey, J.; Su, C.; Mercier, A.; Devillard, S.; Ajzenberg, D. Phylogeography of Toxoplasma gondii points to a South American origin. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2017, 48, 150–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, F.; Yu, X.; Yang, Y.; Hu, S.; Chang, H.; Yang, J.; Duan, G. Seroprevalence and Risk Factors of Toxoplasma gondii Infection in Buffaloes, Sheep and Goats in Yunnan Province, Southwestern China. Iran. J. Parasitol. 2015, 10, 648–651. [Google Scholar]

- Kazem, R.J.; Ali, I.K. Seropositivity and Other Determinants Associated with Toxoplasmosis in Local Buffalo in Iraq. Open J. Vet. Med. 2024, 14, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hove, T.; Dubey, J.P. Prevalence of Toxoplasma gondii antibodies in sera of domestic pigs and some wild game species from Zimbabwe. J. Parasitol. 1999, 85, 372–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, S.P.; Mota, R.A.; Faria, E.B.; Fernandes, E.F.T.S.; Neto, O.L.S.; Albuquerque, P.P.F. Occurrence of IgG antibodies against Neospora caninum and Toxoplasma gondii in buffalo (Bubalus bubalis) raised in state of Para. Pesqui. Vet. Bras. 2010, 30, 443–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Sandhu, K.S.; Bal, M.S.; Kumar, H.; Verma, S.; Dubey, J.P. Serological survey of antibodies to Toxoplasma gondii in sheep, cattle, and buffaloes in Punjab, India. J. Parasitol. 2008, 94, 1174–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konnai, S.; Mingala, C.N.; Sato, M.; Abes, N.S.; Venturina, F.A.; Gutierrez, C.A.; Sano, T.; Omata, Y.; Cruz, L.C.; Onuma, M.; et al. A survey of abortifacient infectious agents in livestock in Luzon, the Philippines, with emphasis on the situation in a cattle herd with abortion problems. Acta Trop. 2008, 105, 269–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konrad, J.L.; Campero, L.M.; Caspe, G.S.; Brihuega, B.; Draghi, G.; Moore, D.P. Detection of antibodies against Brucella abortus, Leptospira spp., and apicomplexa protozoa in water buffaloes in the Northeast of Argentina. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2013, 45, 1751–1756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltazar-Pérez, J.; Utrera-Quintana, F.; Camacho-Ronquillo, J.; González-Garduño, R.; Jiménez-Cortez, H.; Villa-Mancera, A. Prevalence of Neospora caninum, Toxoplasma gondii and Brucella abortus in water buffalo (Bubalus bubalis): Climatic and environmental risk factors in eastern and southeast Mexico. Microb. Pathog. 2022, 173, 105871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, H.M.; Abdel-Rahman, A.A.H.; Bishr, N.M. Seroprevalence of Neospora caninum and Toxoplasma gondii IgG and IgM antibodies among buffaloes and cattle from Menoufia Province, Egypt. J. Parasit. Dis. 2021, 45, 952–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Fadaly, H.A.; Hassanain, N.A.; Shaapan, R.M.; Hassanain, M.A.; Barakat, A.M.; Abdelrahman, K.A. Molecular detection and genotyping of Toxoplasma gondii from Egyptian isolates. Asian J. Epidemiol. 2017, 10, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, H.M.; Abdel-Rahman, A.A.-H.; Bishr, N.M. Sero-positivity of anti-Toxoplasma gondii and anti-Neospora caninum antibodies among cattle and buffaloes from delta of Egypt. J. Parasit. Dis. 2025, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rifaat, M.A.; Micheal, S.A.; Morsy, T.A. Toxoplasmosis skin test survey among buffalo and cattle in U.A.R. (preliminary report). J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1968, 71, 297–298. [Google Scholar]

- Lindsay, D.S.; Dubey, J.P. Neosporosis, Toxoplasmosis, and Sarcocystosis in Ruminants: An Update. Vet. Clin. N. Am. Food Anim. Pract. 2020, 36, 205–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stelzer, S.; Basso, W.; Benavides Silván, J.; Ortega-Mora, L.M.; Maksimov, P.; Gethmann, J.; Conraths, F.J.; Schares, G. Toxoplasma gondii infection and toxoplasmosis in farm animals: Risk factors and economic impact. Food Waterborne Parasitol. 2019, 3, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Kappany, Y.M.; Rajendran, C.; Ferreira, L.R.; Kwok, O.C.H.; Abu-Elwafa, S.A.; Hilali, M.; Dubey, J.P. High prevalence of toxoplasmosis in cats from Egypt: Isolation of viable Toxoplasma gondii, tissue distribution, and isolate designation. J. Parasitol. 2010, 96, 1115–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbas, I.E.; Villena, I.; Dubey, J.P. A review on toxoplasmosis in humans and animals from Egypt. Parasitol. 2020, 147, 135–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meerburg, B.G.; Kijlstra, A. Changing climate-changing pathogens: Toxoplasma gondii in North-Western Europe. Parasitol. Res. 2009, 105, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bărburaș, D.; Györke, A.; Blaga, R.; Bărburaș, R.; Kalmár, Z.; Vişan, S.; Mircean, V.; Blaizot, A.; Cozma, V. Toxoplasma gondii in water buffaloes (Bubalus bubalis) from Romania: What is the importance for public health? Parasitol. Res. 2019, 118, 2695–2703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouatbi, M.; Amairia, S.; Amdouni, Y.; Boussaadoun, M.A.; Ayadi, O.; Al-Hosary, A.A.T.; Rekik, M.; Ben Abdallah, R.; Aoun, K.; Darghouth, M.A.; et al. Toxoplasma gondii infection and toxoplasmosis in North Africa: A review. Parasite 2019, 26, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarado-Esquivel, C.; Romero-Salas, D.; García-Vázquez, Z.; Cruz-Romero, A.; Peniche-Cardeña, A.; Ibarra-Priego, N.; Aguilar-Domínguez, M.; Pérez-de-León, A.A.; Dubey, J.P. Seroprevalence of Toxoplasma gondii infection in water buffaloes (Bubalus bubalis) in Veracruz State, Mexico and its association with climatic factors. BMC Vet. Res. 2014, 10, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyhan, Y.E.; Babür, C.; Yilmaz, O. Investigation of anti-Toxoplasma gondii antibodies in water buffaloes (Bubalus bubalis) in Samsun and Afyon provinces. Turk. Soc. Parasitol. 2014, 38, 220–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiengcharoen, J.; Thompson, R.C.; Nakthong, C.; Rattanakorn, P.; Sukthana, Y. Transplacental transmission in cattle: Is Toxoplasma gondii less potent than Neospora caninum? Parasitol. Res. 2011, 108, 1235–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canada, N.; Meireles, C.S.; Rocha, A.; da Costa, J.M.; Erickson, M.W.; Dubey, J.P. Isolation of viable Toxoplasma gondii from naturally infected aborted bovine fetuses. J. Parasitol. 2002, 88, 1247–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klun, I.; Djurkovic-Djakovoc, O.; Katic-Radivojevic, S.; Nikolic, A. Cross-sectional survey on Toxoplasma gondii infection in cattle, sheep and pigs in Serbia: Seroprevalence and risk factors. Vet. Parasitol. 2006, 135, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagmadulam, B.; Myagmarsuren, P.; Fereig, R.M.; Igarashi, M.; Yokoyama, N.; Battsetseg, B.; Nishikawa, Y. Seroprevalence of Toxoplasma gondii and Neospora caninum infections in cattle in Mongolia. Vet. Parasitol. Reg. Stud. Rep. 2018, 14, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smit, M.; Andrews, C.J.; Draganova, I.; Corner-Thomas, R.A.; Thomas, D.G. Longitudinal Study on the Effect of Season and Weather on the Behaviour of Domestic Cats (Felis catus). Animals 2025, 15, 637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amroabadi, M.A.; Rahimi, E.; Shakerian, A. Seasonal and Age Distribution of Toxoplasma gondii in Milk of Naturally Infected Animal Species and Dairy Samples. Egyptian J. Vet. Sci. 2020, 51, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, J.P.; Cerqueira-Cézar, C.K.; Murata, F.H.A.; Kwok, O.C.H.; Yang, Y.R.; Su, C. All about toxoplasmosis in cats: The last decade. Vet. Parasitol. 2020, 283, 109145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Kappany, Y.M.; Lappin, M.R.; Kwok, O.C.; Abu-Elwafa, S.A.; Hilali, M.; Dubey, J.P. Seroprevalence of Toxoplasma gondii and concurrent Bartonella spp., feline immunodeficiency virus, feline leukemia virus, and Dirofilaria immitis infections in Egyptian cats. J. Parasitol. 2011, 97, 256–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frenkel, J.K.; Lindsay, D.S.; Parker, B.B.; Dobesh, M. Dogs as possible mechanical carriers of Toxoplasma, and their fur as a source of infection of young children. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2003, 7, 292–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Metwally, S.; Hamada, R.; Sobhy, K.; Frey, C.F.; Fereig, R.M. Seroprevalence and risk factors analysis of Neospora caninum and Toxoplasma gondii in cattle of Beheira, Egypt. Front. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10, 1122092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.