Choledochal Stenting for Treatment of Extrahepatic Biliary Obstruction in Dogs with Ruptured Gallbladder: 2 Cases

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

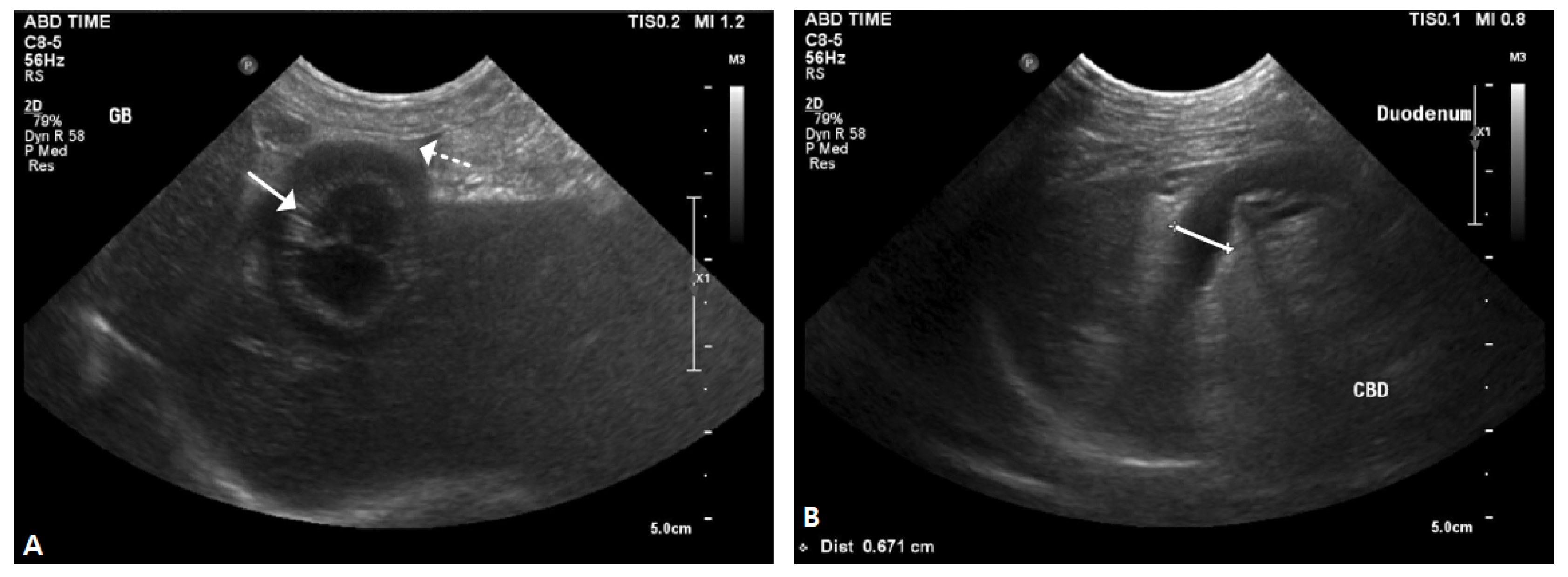

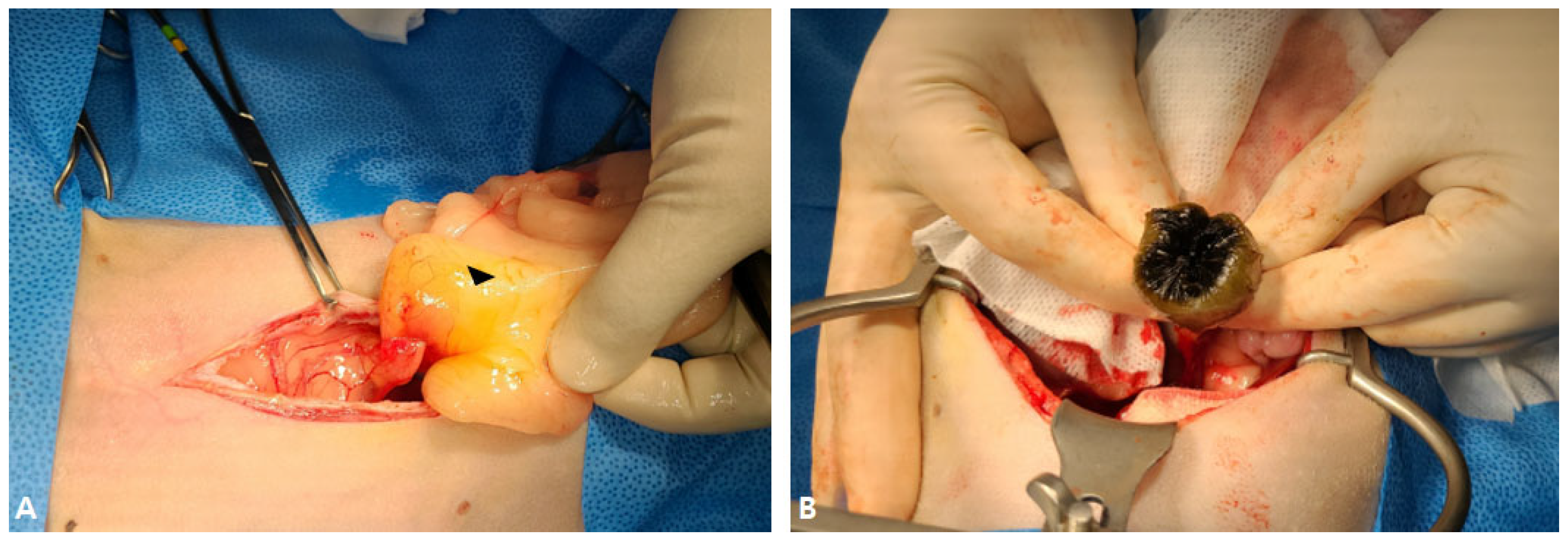

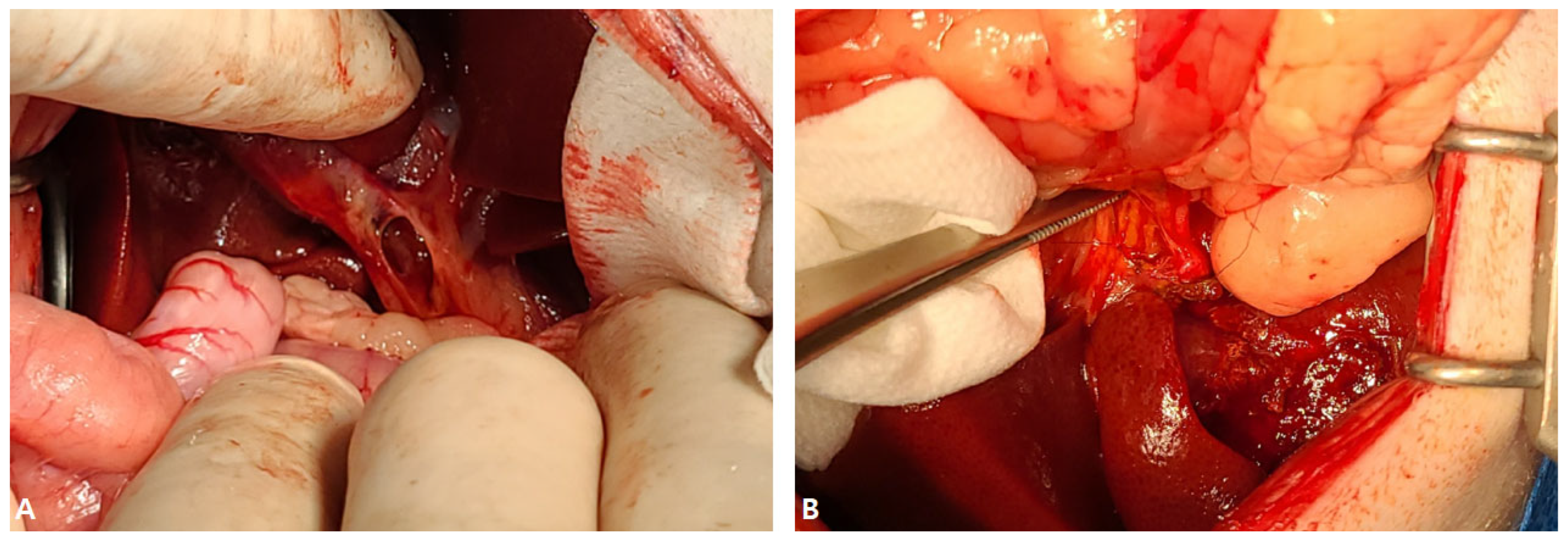

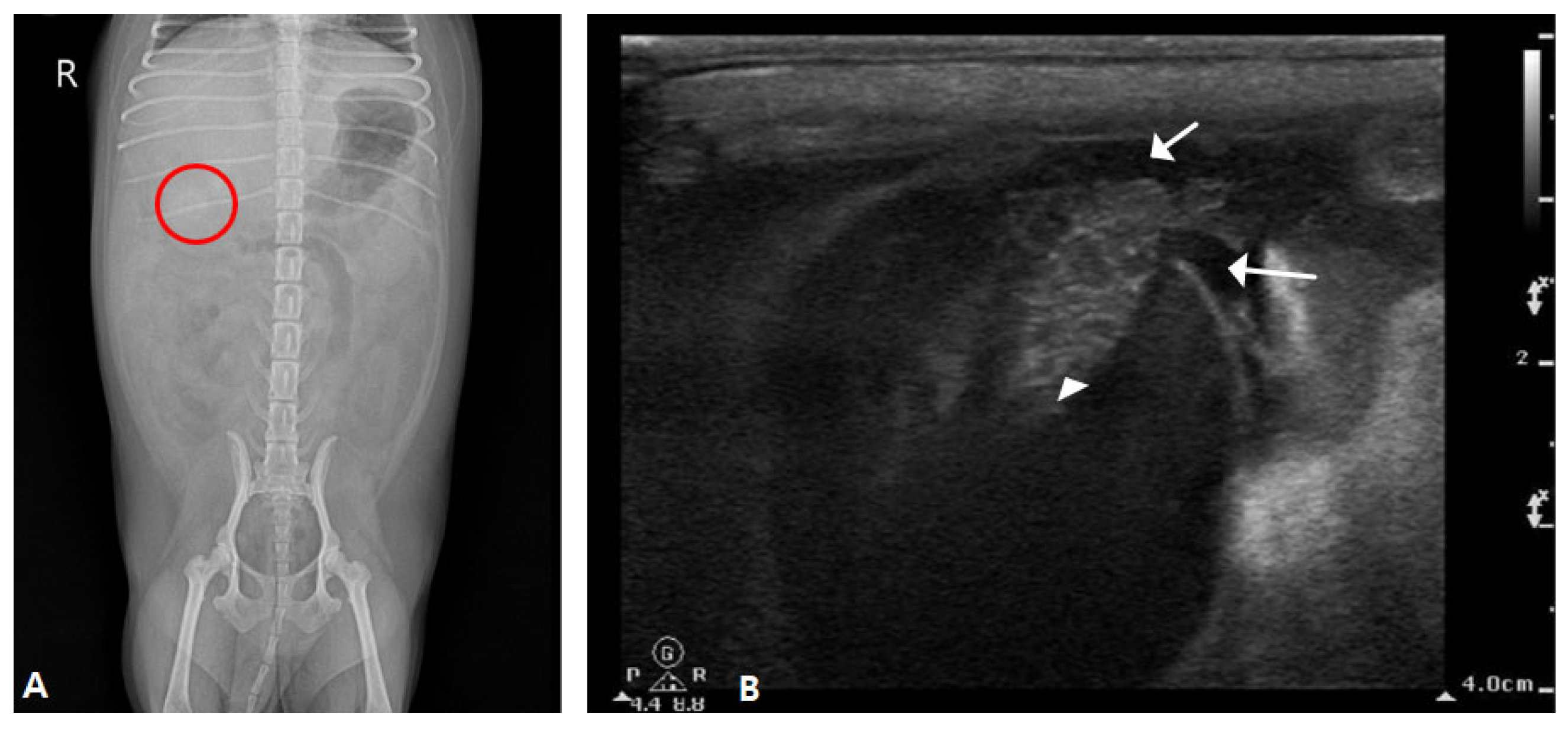

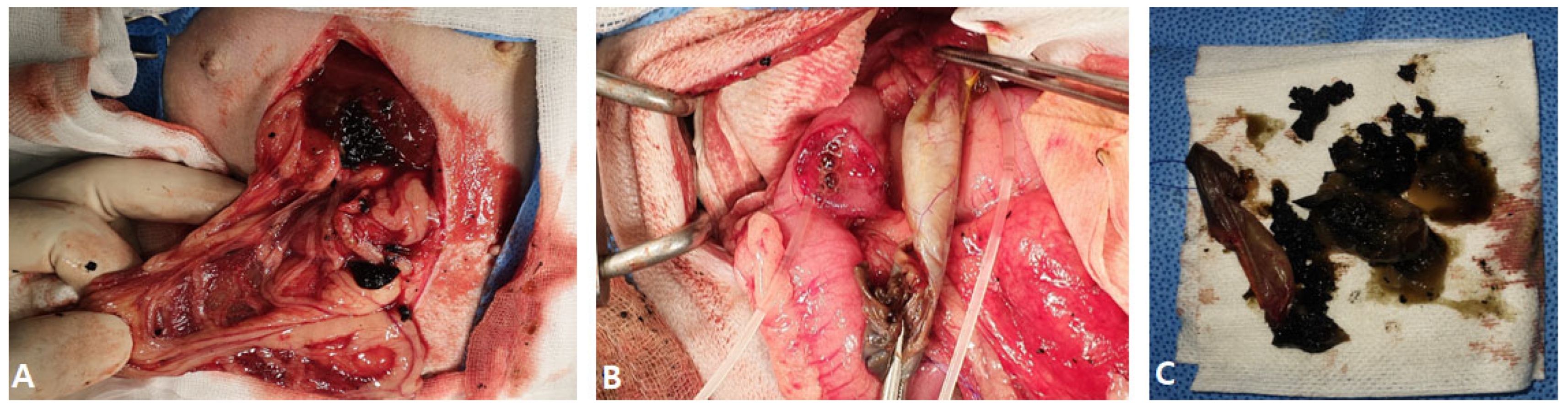

2.1. Case I

2.2. Case II

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gookin, J.L.; Mathews, K.G.; Seiler, G. Diagnosis and management of gallbladder mucocele formation in dogsi. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2025, 263, 777–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cleary, K.; Chong, W.L.; Angles, J.M. Features, management and long-term outcome in dogs with pancreatitis and bile duct obstruction treated medically and surgically: 41 dogs (2015–2021). J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2023, 261, 1694–1701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilkinson, A.R.; De Monaco, S.M.; Panciera, D.L.; Otoni, C.C.; Leib, M.S.; Larson, M.M. Bile duct obstruction associated with pancreatitis in 46 dogs. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2020, 34, 1794–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, J.H.; Noh, M.Y.; Yoon, H.Y. Intrahepatic Duct Incision and Closure for the Treatment of Multiple Cholelithiasis in a Dog. Vet. Sci. 2024, 11, 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matthiesen, D.T. Complications associated with surgery of the extrahepatic biliary system. Prev. Vet. Med. 1989, 1, 295–313. [Google Scholar]

- Bergen, J.L.; Travis, B.M.; Pike, F.S. Clinical use of uncovered balloon-expandable metallic biliary stents for treatment of extrahepatic biliary tract obstructions in cats and dogs: 11 cases (2012–2022). Vet. Surg. 2024, 53, 320–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butler, T.; Bexfield, N.; Dor, C.; Fantaconi, N.; Heinsoo, I.; Kelly, D.; Kent, A.; Pack, M.; Spence, S.J.; Ward, P.M.; et al. A multicenter retrospective study assessing progression of biliary sludge in dogs using ultrasonography. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2022, 36, 976–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newman, S.J.; Steiner, J.M.; Woosley, K.; Williams, D.A.; Barton, L. Histologic assessment and grading of the exocrine pancreas in the dog. J. Vet. Diagn. Investig. 2006, 18, 115–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palermo, S.M.; Brown, D.C.; Mehler, S.J.; Rondeau, M.P. Clinical and Prognostic Findings in Dogs with Suspected Extrahepatic Biliary Obstruction and Pancreatitis. J. Am. Anim. Hosp. Assoc. 2020, 56, 270–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chmelovski, R.A.; Granick, J.L.; Ober, C.P.; Young, S.J.; Thomson, C.B. Percutaneous transhepatic cholecystostomy drainage in a dog with extrahepatic biliary obstruction secondary to pancreatitis. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2020, 257, 531–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parkanzky, M.; Grimes, J.; Schmiedt, C.; Secrest, S.; Bugbee, A. Long-term survival of dogs treated for gallbladder mucocele by cholecystectomy, medical management, or both. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2019, 33, 2057–2066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guess, S.C.; Harkin, K.R.; Biller, D.S. Anicteric gallbladder rupture in dogs: 5 cases (2007–2013). J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2015, 247, 1412–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Worley, D.R.; Hottinger, H.A.; Lawrence, H.J. Surgical management of gallbladder mucoceles in dogs: 22 cases (1999–2003). J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2004, 225, 1418–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossanese, M.; Williams, P.; Tomlinson, A.; Cinti, F. Long-Term Outcome after Cholecystectomy without Common Bile Duct Catheterization and Flushing in Dogs. Animals 2022, 12, 2112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayhew, P.D.; Richardson, R.W.; Mehler, S.J.; Holt, D.E.; Weisse, C.W. Choledochal tube stenting for decompression of the extrahepatic portion of the biliary tract in dogs: 13 cases (2002–2005). J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2006, 228, 1209–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pike, F.S.; Berg, J.; King, N.W. Gallbladder mucocele in dogs: 30 cases (2000–2002). J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2004, 224, 1615–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Test Item | Measured Value | Reference Range |

|---|---|---|

| Album | 3 g/dL | 2.3–4.0 g/dL |

| Alanine Transferase (ALT) | 401 U/L | 10–125 U/L |

| Alkaline Phosphatase (ALKP) | 1.888 U/L | 23–212 U/L |

| Gamma-glutamyl Transferase (GGT) | 11 U/L | 0–11 U/L |

| Total bilirubin (TB) | 3.1 mg/dL | 0–0.9 mg/dL |

| C-reactive Protein (CRP) | 50 mg/L | 0–1 mg/dL |

| Test Item | Measured Value | Reference Range |

|---|---|---|

| Album | 2.3 g/dL | 2.3–4.0 g/dL |

| Alanine Transferase (ALT) | 155 U/L | 10–125 U/L |

| Alkaline Phosphatase (ALKP) | 1.944 U/L | 23–212 U/L |

| Gamma-glutamyl Transferase (GGT) | 23 U/L | 0–11 U/L |

| Total bilirubin (TB) | 0.4 mg/dL | 0–0.9 mg/dL |

| C-reactive Protein (CRP) | 13.6 mg/L | 0–1 mg/dL |

| Test Item | Measured Value | Reference Range |

|---|---|---|

| White Blood Cell Count (WBC) | 24.34 × 109/L | 5.05–16.76 × 109/L |

| Albumin | 2.1 g/dL | 2.3–4.0 g/dL |

| Alanine Transferase (ALT) | 437 U/L | 10–125 U/L |

| Alkaline Phosphatase (ALKP) | 1.659 U/L | 23–212 U/L |

| Gamma-glutamyl Transferase (GGT) | 27 U/L | 0–11 U/L |

| Total bilirubin | 2.4 mg/dL | 0–0.9 mg/dL |

| C-reactive Protein (CRP) | 13.6 mg/L | 0–1 mg/dL |

| Canine Pancreatic Lipase (cPL) | 1.4353 ng/mL | 200–400 ng/mL |

| Test Item | Postoperative Day | Measured Value | Reference Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Albumin | Day 3 | 2.3 g/dL | |

| Day 6 | 3.6 g/dL | ||

| Alanine Transferase (ALT) | Day 3 | 193 U/L | 10–125 U/L |

| Day 6 | 122 U/L | ||

| Alkaline Phosphatase (ALKP) | Day 3 | 1.633 U/L | 23–212 U/L |

| Day 6 | 624 U/L | ||

| Gamma-glutamyl Transferase (GGT) | Day 3 | 12 U/L | 0–11 U/L |

| Day 6 | 7 U/L | ||

| Total bilirubin (TB) | Day 3 | 0.8 mg/dL | 0–0.9 mg/dL |

| Day 6 | 0.5 mg/dL | ||

| C-reactive Protein (CRP) | Day 3 | 5.9 mg/L | 0–1 mg/dL |

| Day 6 | 3.7 mg/L | ||

| Canine Pancreatic Lipase (cPL) | No record | No record | 200–400 ng/mL |

| Day 6 | 86.1 ng/mL |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, S.-H.; Seo, J.-H.; Cho, J.-H. Choledochal Stenting for Treatment of Extrahepatic Biliary Obstruction in Dogs with Ruptured Gallbladder: 2 Cases. Vet. Sci. 2025, 12, 673. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci12070673

Lee S-H, Seo J-H, Cho J-H. Choledochal Stenting for Treatment of Extrahepatic Biliary Obstruction in Dogs with Ruptured Gallbladder: 2 Cases. Veterinary Sciences. 2025; 12(7):673. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci12070673

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Shin-Ho, Jeong-Hyun Seo, and Jae-Hyeon Cho. 2025. "Choledochal Stenting for Treatment of Extrahepatic Biliary Obstruction in Dogs with Ruptured Gallbladder: 2 Cases" Veterinary Sciences 12, no. 7: 673. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci12070673

APA StyleLee, S.-H., Seo, J.-H., & Cho, J.-H. (2025). Choledochal Stenting for Treatment of Extrahepatic Biliary Obstruction in Dogs with Ruptured Gallbladder: 2 Cases. Veterinary Sciences, 12(7), 673. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci12070673