Simple Summary

This study investigated congenital malformations in pigs associated with anomalous twinning. Among the conjoined twins recorded, the most common defect was syncephalus thoracopagus or cephalothoracopagus. Some dicephalic and diprosopic anomalies were also recorded. Finally, some cases of thoraco-omphalopagus piglets were studied. The pathogenetic mechanisms of this disease, which is common in veterinary practice, are discussed. The significance of embryonic conjoined twins is frequently associated with dystocia.

Abstract

A review of congenital malformations in swine relating to abnormal twinning was carried out. The aim was to describe and estimate these defects. Among the recorded twins, the most common defect was the syncephalus thoracopagus or cephalothoracopagus. A couple of dicephali and diprosopus congenital anomalies were also registered. At last, some cases of thoraco-omphalopagus piglets were surveyed. There was also a report of an acardiac twin (hemiacardius acephalus) and a case of a conjoined parasitic twin. The pathogenetic mechanisms of this condition, frequently reported in veterinary practice, are discussed. The importance of embryonic imperfect twinning is commonly associated with dystocia.

1. Introduction

Congenital malformations are observed in various cases of veterinary practice. The domestic pig is an animal model used to evaluate potential cause–effect relationships between the environment and congenital malformations. For this reason, swine have been used as a model for an in-depth study of human congenital anomalies [1]. In addition, pig production is widely propagated all over the world. The record of congenital defects is essential in veterinary medicine and pig husbandry. In farm animals, especially in swine, embryonic duplications represent one of the biggest groups of congenital anomalies and are a common cause of dystocia and the delivery of stillborn embryos [2]. Congenital duplications (conjoined twins, parasitic twins, or acardiac twins) are unique and interesting among congenital defects [2]. These duplications form a spectrum of structures which vary from slight duplication to near separation of two individuals. According to the degree, sites, and angle of fusion, they have wide external variation [1] and are classified as acardiac, conjoined symmetric, or asymmetric twins, and unequal conjoined twins (heteropagus or parasitic twins). However, in the Nomina Embryologica Veterinaria (2017) [3], a simpler classification of twinning was suggested. According to the latter, there are the Gemini acardiaci and the Gemini conjuncti. The Gemini conjuncti are further subdivided into Gemini conjuncti symmetrici and asymmetrici (Table 1).

Table 1.

The classification of abnormal twins according to the Nomina Embryologica Veterinaria.

2. Conjoined Twins

According to the Nomina Embryologica Veterinaria (NEV) the malformed conjoined twins are subdivided into two main categories, namely symmetric and asymmetric (International Committee on Veterinary Embryological Nomenclature 2017). Furthermore, both the symmetric and asymmetric twins are classified into three general conjunction groups: cranial, medial, and caudal conjunction. Classically, the conjoined twins can be divided into dorsal, lateral, and ventral conjunction types [4]. The caudal ventral conjunction comprises the ileoischiopagus, whereas the lateral conjunction is the parapagus diprosopus and parapagus dicephalus. The rostral ventral conjunction comprises the cephalopagus, thoracopagus, and omphalopagus. When the twins are joined dorsally, they are the craniopagus, rachipagus, and pygopagus. In more detail, the presentation of various genetic anomalies is provided and contrasted with the malformations identified in our case.

2.1. Diprosopus

Among the conjoined twins presented both by Wilder (1908) [5] and Bishop (1908) [6], two diprosopi twins were evaluated. The first, characterized as diprosopus triophathalmos, possessed two snouts, two normal external ears, two tongues, several teeth, and two laterally located eyes. The median eye was composed of a double eyeball. The second was characterized as diprosopus tetrophthalmus. A bilaterally symmetrical median eye composed of two eyeballs was observed. No median ear was present. Two snouts were separated.

In the case report of Thuringer (1919) [7], the diprosopus piglet possessed two snouts, two tongues which were fused at their base, two mandibles but a single nasopharynx, and a single epiglottis. In the face, four eyes were observed within three orbits. The head had two ears. Two separate cerebri, two cerebelli, and two fused medullae oblongatae, as well as a single spinal cord were noticed. The right and left lateral cerebral hemispheres and the corresponding lateral halves of the midbrains and pontes were normal in size. Fusion of the two cerebrospinal axes was affected in the lower part of the fourth ventricle and was limited to the medulla oblongata. In addition, complete bilateral duplication of the cranial nerves, from the first to the eighth pair, was observed. However, the entire skeleton (caudally to the first dorsal vertebra) and the heart were normal.

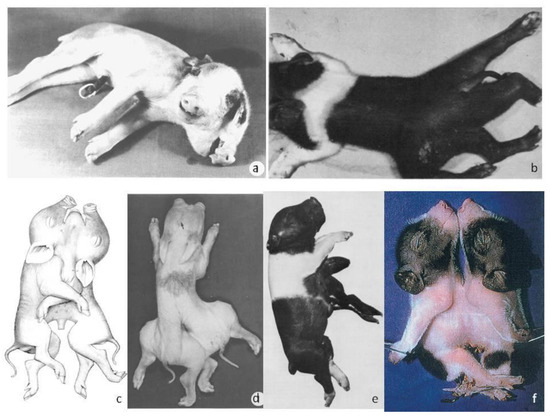

Later, diprosopus and dipygus porcine conjoined twins were studied [8]. In addition to the conjoining anomaly, these twins (Figure 1d) also exhibited ambiguous internal reproductive features. Two snouts, three eyes, and a single thorax were observed, while the twins were duplicated from the umbilicus caudally. Radiography revealed a single vertebral column in the cervical region. The vertebral columns were separated caudally from this point. There was a total of six limbs—one pair of forelimbs and two pairs of hindlimbs. Many medial structures were not developed in these twins, such as (a) medial cranial nerves V-XI1 that were absent or displaced although normal laterally, (b) medial palates that were present but shortened, and (c) medial mandibular rami that had folded back on themselves rostrally to form a midline mass between the two chins. Moreover, one lateral kidney and one lateral testis were noticed in each twin. Medial scrotal sacs were present but were devoid of a testis. Finally, a midline-like structure was observed that crossed between the twins and histological analysis revealed it to be dysplastic testicular tissue.

Figure 1.

(a) Two-headed piglet [9], (b) Dipygus pig [10], (c) Prosopothoracopagus disymmetros [11], (d) Diprosopus dipygus [8], (e) Epigastricus parasite [10], (f) Thoracopagus diplopagus [12].

2.2. Dicephalus

Groth (1964) [13] provided an illustration of a dicephalus piglet (Figure 2b) and Partlow et al. (1981) [9] provided a case report (Figure 1a). A normal body with two heads joined in the occipital region was noticed [10]. In addition, two complete snouts, four eyes, and three ears were noticed. The lower jaws were immobile because of overlapping mandibular rami. Although there was only one vertebral column, the bodies of the vertebrae, but not the neural arches, were doubled from the axis to T8. One thyroid gland and one larynx and hyoid apparatus were also observed. The two tongues were joined at their base just rostral to the single epiglottis. A completely split palate was observed in the right head but was only partially split in the left. The cranial nerves were normal and doubled except for IX, X, and XI. Moreover, fused brains were noticed at the pons–medulla junction. An anomalous midline tag of neural tissue resembling remnants of the medial halves of two nervous systems extended from this point to the level of T8.

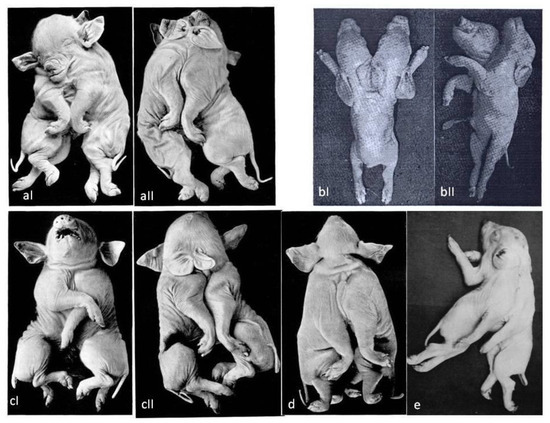

Figure 2.

(aI,aII) Cephalothoracopagus monosymmetros tetrophthalmus synotos tetrabrachius [11], (bI,bII) Dicephalus parapagus [13], (cI,cII) Cephalothoracopagus monosymmetros synotos tetrabrachius craniis a latere coalitis [11], (d) Cephalothoracopagus monosymmetros biauritus tetrabrachius [11], (e) Syncephalus pig [10].

2.3. Syncephalus Thoracopagus or Cephalothoracopagus

Otto 1841 provided the first brief description of a partially double-syncephalus pig [11]. During the following years, many cases of syncephalus thoracopagus were published. Glaser (1928) [11] published a detailed and extended account of swine cephalothoracopagus cases and discussed other similar cases described until then mainly by European scientists.

Table 2 presents brief descriptions of various malformations of Syncephalus Thoracopagus piglets. Also, in Figure 1c and Figure 2a–e some variations of Syncephalus thoracopagus are illustrated. Cephalothoracopagus is the most common case of conjoined twins in swine.

Table 2.

Brief descriptions of various malformations of Syncephalus thoracopagus.

2.4. Our Case

A case of two conjoined piglets born dead was submitted to the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, School of Health Sciences, University of Thessaly by a local pig breeder from a farm of 450 sows. There had been no prior occurrences of conjoined twins on this farm and the sow had previously delivered multiple normal piglets. Labor comprising the conjoined twins began to proceed normally. The sow delivered live and healthy piglets at 5 to 10 min intervals. All live-born piglets had a birth weight of approximately 1.1 kg. The last cub followed, but they were conjoined twins. The labor became very complicated and lasted 12 h. The sow was then administered oxytocin at a concentration of 10 IU/mL to stimulate uterine contraction. Eventually, the dead conjoined twins were withdrawn with professional assistance. The female was subsequently excluded from breeding. The case of the conjoined twins was unique on this farm.

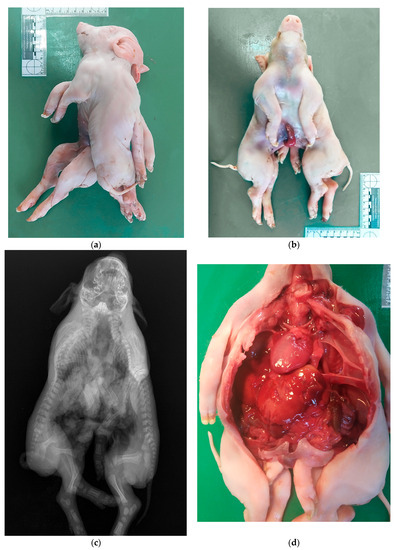

The external gross examination revealed that the two piglets were joined at the head, neck, and thorax anatomic regions, forming one-headed conjoined twins with one oral cavity, two nostrils, two eyes, four ear pinnaes, one thoracic cavity, four forelimbs, four hindlimbs, two tails, and only one umbilicus (Figure 3a,b). The conjoined piglets were both female with a normal vulva and anus each.

Figure 3.

Studied case of the two conjoined piglets: the external gross view in a lateral (a) and in a supine position (b) before necropsy; a panoramic X-ray image in a supine position (c); and a panoramic gross view of the opened body cavities, showing the single enlarged heart and the other internal organs (d). The notable findings in each image are described in detail in the above text (Section 2.3.). Personal archive of Assistant Prof. Dimitrios Doukas.

Then, an X-ray examination of the dead conjoined twins was taken, showing one extended cranial cavity and one extended thorax with 13 ribs bilaterally, ending in one sternum. Moreover, two separated and complete spinal columns were detected (Figure 3c).

Finally, a full necropsy of the specimen was performed in the necropsy room. The presence of two completely separated bodies caudal to the single umbilicus was confirmed with normal kidneys and other retroperitoneal organs in each one piglet. In contrast, cranially to the single umbilicus, the below congenital conjunction patterns were found:

- Two separated spinal cords (one per each vertebral canal);

- A single oral cavity with a single esophagus ending up in a common stomach;

- A common abdominal cavity;

- A common duodenum dividing into a Y shape, creating two separated jejunum tubes;

- A single liver and a single pancreas;

- A single larynx with a single trachea ending up in two bronchi;

- Separated lungs (one lung per bronchus);

- A single enlarged heart (Figure 3d).

2.5. Thoraco-Omphalopagus

The conjoined twins which belong in this category are normally formed piglets joined by a union that involves the thoracic and abdominal region. The union extended from the umbilical cord up to the base of the neck [27] or the point of union was along the ventral surface of the body, extending from the first rib to a point just posterior to the umbilicus [28] or the fused abdominal cavities at the cranial third of the abdomen, and the thoracic cavities were completely fused at the sternum and had pairs of ribs [12]. The thoraco-omphalopagi embryos had a single umbilical cord for both piglets.

The double pig of Baumgardner and Everham (1936) [27] possessed separate and normal legs, tails, heads, and necks. All the main structures of the digestive tracts were normal, apart from the small intestines. These joined a short distance from the duodenum, after which there was a bifurcation, and the tracts were normal to their respective end. The most interesting feature of this piglet was the development of the bile ducts. Each duct entered the stomach instead of the duodenum. The livers were fused.

Partial dissection of the swine specimen [28] revealed some interesting information concerning the arrangement of the internal organs and the region of fusion of the twins. The umbilical cord was composed of two complete sets of umbilical vessels. The sternums were completely absent, the animals were joined both at the ribs, all of which were fused, and along the anterior portion of the abdominal wall. This resulted in the formation of common thoracic and abdominal cavities, separated by a complete diaphragm. A single pericardium enclosed the two hearts, the apices of which overlapped. The livers formed a single organ; there was no definite line of demarcation between the two portions which had completely fused during development. One stomach was well-developed, while the other lacked a pyloric portion.

Postmortem examination of the two piglets [12] revealed them to be identical and symmetrical (Figure 1f). Completely separated heads and necks were observed in both piglets, with four ears, four eyes, four nostrils, and two mouths. Moreover, four duplicated and fully developed limbs were noticed. A separate abdominal and thoracic cavity was observed in each piglet, while the anatomical structures in one piglet were a mirror image of the other (similar and well-developed internal organs were noticed in both piglets). The livers were fused, with a separate gall bladder in each of them. A separate long, narrow spleen and stomach, two normal kidneys and ureters, and a urinary bladder were noticed in both piglets. In addition, a heart and a pair of lungs were observed in both piglets, with a common pericardial membrane. However, the heart and lungs were comparatively less well-developed in the one piglet [12].

3. Free Monozygotic and Parasitic Twins

A case of monozygotic asymmetrical twins, hemiacardius acephalus, was investigated [29]. The asymmetrical twins comprised a well-formed fetus and another which was defective. The hemiacardius acephalus lacked the head. The rest of the skeleton was formed and at the apical left part of the cervical region of the trunk, a rudimentary auricle with a blind ear canal was detected. An epigastricus parasite twin is illustrated in Figure 1e.

4. Discussion

Based on the literature, numerous abnormal twin classifications have been reported, based on anatomy, site of union, symmetry level of twins, and embryological development. Abnormalities in the anatomy of conjoined twins arise during the prenatal period of the pregnant animals. The implications of the aforementioned abnormalities can lead to organ dysfunction or failure and often death. However, in regard to the main causes of the development of conjoined twins, several genetic and environmental factors are proposed [4].

The origin of conjoined twins has been described by two main theories [30]. The first theory assumes that a fertilized egg splits into two embryos in the early stages of cell division. However, the individual embryos do not split completely, as is the case in the normal development of identical twins, but some body parts of the two siblings remain joined. In the development of conjoined twins, the embryo only partially separates to form two bodies, but conjoined twins are a single organism with multiple morphological duplications. Although the two fetuses develop, they remain physically joined, usually at the breast, abdomen, or pelvis. The second theory is that the two embryos are initially completely separated, but then the active stem cells find each other and join to form a new adhesion of different sizes and locations [31].

In the cases surveyed in the present review, most conjoined piglets were male and in only two of them [12,18] they were female. The imperfect embryonic twinning of piglets has occurred independently of the breed. The cumulative observations of the current survey are from the 67 records by Selby et al. (1973) [10]. The frequency of conjoined twinning is reported as 6/1000, or 0.6%, and it is considered the most common defect (without consideration of multiple anomalies), representing 51/319, or 8%, of the total number of abnormal newborn piglets [32]. In the same survey, among 57 piglets with cleft palates, 21 (36.8%) were classified under conjoined twins. In another survey of swine congenital malformations, among one hundred and seventy-four defects, four were reported as conjoined twins [32]. However, a previous study supported that the recalculation from these conservative estimates indicates that the conjoined twinning rate is approximately 0.048% of all swine births [9]. The diprosopi-dipygus animal is an extremely rare abnormality for swine (1.5% of swine-conjoined twins or 0.00072% of swine births) [10]. The frequency of conjoined twinning in different geographic areas is not fully understood. For example, no conjoined twins were noticed in a study carried out in Denmark including 29,886 births [33].

The report of each case of abnormal twins from veterinarians, farmers, and swine breeders is a crucial point. For future studies, it is very important to have access to appropriate data from farmers or swine breeders about the grandparent sows, genetic background, animal welfare conditions, nutrition, vaccinations, health status, infectious diseases, etc.

5. Conclusions

To date, several cases of congenital malformations in swine have been reported. The occurrence of newborn conjoined twins is always very interesting and unique. These anomalies are often observed during or after perinatal reproductive disorders (e.g., dystocia), mainly due to poor prenatal screening techniques in swine. Therefore, congenital malformations are an important pathological condition in pigs, and each case should be studied as an individual case because it presents particular anatomical differences. The issue of this anomaly has not yet been clearly explained. Due to the large number of newborns, it seems likely that genetic factors are negligible in the occurrence of congenital anomalies. However, breeding conditions can also be hypothetically included among the causes. For future studies, it is necessary to have access to appropriate data from farmers or pig breeders to be able to identify the pathogenetic mechanisms leading to this condition and, thus, prevent the occurrence of these anomalies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.P.; methodology, A.P., G.I.P., D.D. and V.G.P.; investigation, A.P., G.I.P., D.D. and V.G.P.; formal analysis, G.I.P.; writing—original draft preparation, A.P., G.IP., D.D. and V.G.P.; writing—review and editing, A.P. and V.G.P.; supervision, A.P. and V.G.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The present study was carried out under the appropriate approval (number 89/26 April 2023) of the Institutional Animal Use Ethics Committee (Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, University of Thessaly, Greece).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data is unavailable due to privacy.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the animal scientist of the commercial farm “Xiropal” for providing the case to the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, School of Health Sciences, University of Thessaly.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Arthur, G.H. Conjoined twins—The veterinary aspect. Vet. Rec. 1956, 68, 389–393. [Google Scholar]

- Hiraga, T.; Dennis, S.M. Congenital duplication. Vet. Clin. N. Am. Food Anim. Pract. 1993, 9, 145–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Committee on Veterinary Embryological Nomenclature [I.C.V.E.N.]. Nomina Embryologica Veterinaria, 2nd ed.; ICVEN: Ghent, Belgium, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Tejml, P.; Navratil, V.; Zabransky, L.; Soch, M. Conjoined twins in guinea pigs: A case report. Animals 2022, 12, 1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilder, H.H. The morphology of cosmobia; speculations concerning the significance of certain types of monsters. Am. J. Anat. 1908, 8, 355–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, M. Heart and anterior arteries in monsters of the dicephalus group; a comparative study of cosmobia. Am. J. Anat. 1908, 8, 441–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thuringer, J.M. The anatomy of a dicephalic pig, monosomus diprosopus. Anat. Rec. 1919, 15, 359–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McManus, C.A.; Partlow, G.D.; Fisher, K.P.S. Conjoined twin piglets with duplicated cranial and caudal axes. Anat. Rec. 1994, 239, 224–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Partlow, G.D.; Barrales, D.E.; Fisher, K.P.S. Morphology of a two-headed piglet. Anat. Rec. 1981, 199, 441–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selby, L.A.; Khalili, A.; Stewart, R.W.; Edmonds, L.D.; Marienfeld, C.J. Pathology and epidemiology of conjoined twinning in swine. Teratology 1973, 8, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaser, H. Über die cephalothoracopagen und einen prosopothoracopagus disymmetros vom schwein. Roux Arch. Dev. Biol. 1928, 113, 601–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafa, M.B.; Koma, K.L.M.K.; Acon, J. Conjoined twin piglets. Vet. Rec. 2005, 156, 779–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Groth, W. Dicephalus beim Scwein. Dtsch. Tierarzlt. Wochenschr. 1964, 71, 407. [Google Scholar]

- Wyman, J. Dissection of a double pig. Boston Med. Surg. J. 1861, 64, 535. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, S.R.; Rauch, R.W. The anatomy of a double pig (syncephalus thoracopagus). Anat. Rec. 1917, 13, 273–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Carey, E. The anatomy of a double pig, syncephalus thoracopagus, with especial consideration of the genetic significance of the circulatory apparatus. Anat. Rec. 1917, 12, 177–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, H.E.; Davis, J.S., Jr.; Blackford, S.D. The operation of a factor of spatial relationship in mammalian development as illustrated by a case of quadruplex larynx and triplicate mandible in a duplicate pig monster. Anat. Rec. 1923, 26, 311–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, G.W.; Higgins, G.M. The anatomy of an abnormal double monster (Duroq) pig. Anat. Rec. 1923, 24, 389. [Google Scholar]

- Baumgardner, W.J. A double monster pig-cephalothoracopagus monosymmetros. Anat. Rec. 1928, 37, 303–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordby, J.E.; Taylor, B.L. A syncephalus thoracopagus monster in swine. Am. Nat. 1928, 62, 34–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, E. Einige cephalothoracopagi bei Säugetieren. Virchows Arch. Pathol. Anat. Physiol. Klin. Med. 1931, 3, 706–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hetzer, H.O.; Eaton, O.N. A case of conjoined twins in the pig. Anat. Rec. 1943, 87, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halnan, C.R.E. A cephalothoracopagus pig. J. Anat. 1970, 106, 204. [Google Scholar]

- Czarnecki, C.M.; Schenk, K.M.P. A case of monster twinning (cephalothoracopagus) in the pig. Br. Vet. J. 1977, 133, 530–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulawik, M.; Pluta, K.; Wojnowska, M.; Bartyzel, B.; Nabzdyk, M.; Bukowska, D. Cephalothoracopagus (monocephalic dithoracic) conjoined twins in a pig (Sus scrofa f. domesticus): A case report. Vet. Med. 2017, 62, 470–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd Jones, T. Two anomalies in swine. Can. J. Comp. Med. Vet. Sci. 1945, 9, 287. [Google Scholar]

- Baumgardner, W.J.; Everham, B. A double monster pig-Thoracopagus Disymmetros. Trans. Kansas Acad. Sci. 1936, 39, 251–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donoghue, J.G. Conjoined twin pigs. Can. J. Comp. Med. 1951, 15, 96–97. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Schmincke, A. Vergleichende untersuchungen über die anlage des skelettsystems in tierischen mißbildungen mit einem beitrag zur makro- und mikroskopischen anatomie derselben. Virchows Arch. Pathol. Anat. Physiol. Klin. Med. 1921, 230, 564–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, R. Theoretical and analytical embryology of conjoined twins. Part I: Embryogenesis. Clin. Anat. 2000, 13, 36–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, R. Theoretical and analytical embryology of conjoined twins. Part II: Adjustments to union. Clin. Anat. 2000, 13, 97–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selby, L.A.; Hopps, H.C.; Edmonds, L.D. Comparative aspects of congenital malformations in man and swine. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 1971, 159, 1485–1490. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bille, N.; Nielsen, N.C. Congenital malformations in pigs in a post mortem material. Nord. Vet. Med. 1977, 29, 128–136. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).