Abstract

Molecularly imprinted polymers (MIPs) are promising sorbents for selectively capturing pharmaceutically active compounds (PhACs), but design remains slow because candidate screening is largely experimental or based on computationally expensive methods. We present MIP–PhAC, an open, curated resource of polymer–pharmaceutical interaction energies generated from molecular dynamics (MD) followed by MM/PBSA analysis, with a small DFT subset for cross-method comparison. This resource is comprised of two complementary datasets: MIP–PhAC-Calibrated, a benchmark set with manually verified pH-7 microstates that reports both monomeric (pre-polymerized) and polymeric (short-chain) MD/MMPBSA energies and includes a DFT subset; and MIP–PhAC-Screen, a broader, high-throughput collection produced under a uniform automated workflow (including automated protonation) for rapid within-polymer ranking and machine learning development. For each MIP—PhAC pair we provide ΔG* components (electrostatics, van der Waals, polar and non-polar solvation; −TΔS omitted), summary statistics from post-convergence frames, simulation inputs, and chemical metadata. To our knowledge, MIP–PhAC is the largest open, curated dataset of polymer–pharmaceutical interaction energies to date. It enables benchmarking of end-point methods, reproducible protocol evaluation, data-driven ranking of polymer–pharmaceutical combinations, and training/validation of machine learning (ML) models for MIP design on modest compute budgets.

Dataset: DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.17514456

Dataset License: CC BY-NC 4.0

1. Summary

Pharmaceutically active compounds (PhACs) are increasingly detected in surface and drinking waters; even at low concentrations they pose ecological and public health risks [1,2,3]. Molecularly imprinted polymers (MIPs) are promising for this task, but design remains slow and costly because screening is largely experimental or depends on resource-intensive calculations [4,5]. To address this gap, we assembled MIP–PhAC, which spans 20 PhACs and 24 functional monomers and consists of the following: (i) MIP–PhAC-Calibrated, a curated benchmark with manually verified pH-7 microstates that includes monomeric (pre-polymerized; n = 60 systems) and polymeric (short-chain; n = 60 systems) molecular dynamics (MD) simulations plus a DFT subset (n = 12 systems), where n denotes the number of unique MIP-PhAC combinations; (ii) MIP–PhAC-Screen, a high-throughput collection generated by an automated pipeline (including automated protonation) covering 19 × 23 attempted pairs, 434 of which converged.

To the best of our knowledge, MIP–PhAC is the largest open, curated dataset of polymer–pharmaceutical interaction energies to date. We assembled it to enable within-polymer ranking, calibration, and development of machine learning models for predicting binding interactions from pharmaceutical and polymer descriptors with the goal of accelerating MIP polymer design [6]. The release includes ready-to-use master tables, per-frame energy components, and complete simulation/input archives to support transparent reuse and extension. The systems were built from SMILES, parameterized with GAFF2, packed in 6 × 6 × 6 nm boxes, solvated with SPC water, and simulated in GROMACS [7,8,9,10]. Only the post-convergence frames (defined by a global t95 cutoff) were analyzed with gmx_MMPBSA to report ΔG* means and standard deviations (SDs) (kcal·mol−1; see the Methods section) [11,12]. Representative low-energy conformations were also used to compute a small DFT subset, providing cross-method reference energies.

The dataset supports ongoing projects on ML-based rank prediction, protocol development for longer polymer MD with explicit ions, and application-oriented screens for priority pollutants. We will also perform experimental validation of computed interaction energies via adsorption studies, to be reported separately. In the future, we plan to expand the resource to more complex interaction systems and additional solvents, and to improve our automated pipelines so that users can rapidly generate predictions for new pharmaceutical–polymer combinations. This work was supported by the Croatian Science Foundation (HRZZ-IP-2022-10-4400, “MIPdePharma”). No publications based on this dataset have yet appeared; related manuscripts are in preparation.

2. Data Description

The MIP–PhAC resource contains two complementary MD datasets describing polymer–pharmaceutical interactions intended to aid MIP design. The MIP–PhAC-Calibrated dataset serves as a curated benchmark containing manually verified microstates (charges and protonation adjusted to pH 7) and both monomeric “pre-polymerized” and short-chain polymeric systems (60 unique systems each), along with an additional smaller DFT subset (12 systems) for cross-method validation. The choice of 60 systems reflects the full set of combinations between four representative polymers and the 15 pharmaceuticals currently available in our laboratory, selected to enable future integration of experimentally measured retention data. The MIP–PhAC-Screen expands coverage to 19 pharmaceuticals × 23 polymers (437 attempts); 3 systems failed repeatedly and were excluded, yielding 434 reported systems. The screen was generated with an automated workflow (including automated protonation). All systems were analyzed with MM/PBSA, and we report binding free energies (ΔG*) in kcal mol−1. Lower more negative ΔG* indicates stronger binding.

The datasets collectively include 20 pharmaceuticals and 24 polymeric monomer units (Table 1 and Table 2). The 20 pharmaceuticals included in MIP–PhAC were selected because they represent environmentally relevant, analytically challenging targets for which commercially available MIPs often show inadequate performance. Selection criteria included (i) documented frequent occurrence in environment monitoring programs, including EU “Watch List” substances; (ii) literature reports of persistence, toxicity, and removal difficulty; and (iii) physicochemical indicators of poor biodegradability and bioaccumulation potential (e.g., BIOWIN < 0.5).

Functional monomers were chosen to reflect the interaction diversity relevant to MIP design. Different interaction types provide distinct selectivity profiles [13], so we selected a set of widely used monomers spanning a broad range of physicochemical properties and interaction mechanisms [14,15].

Together these combinations provide a diverse sampling of pharmaceutical–polymer interactions for benchmarking or model development.

Table 1.

Pharmaceutically active compounds included in MIP–PhAC datasets. Each entry lists the compound name, molecular formula, CAS number, molecular weight (Mw), pKa values, logarithm of the octanol/water partition coefficient (log Kow), and dataset inclusion. Physiochemical properties were retrieved from PubChem [16].

Table 1.

Pharmaceutically active compounds included in MIP–PhAC datasets. Each entry lists the compound name, molecular formula, CAS number, molecular weight (Mw), pKa values, logarithm of the octanol/water partition coefficient (log Kow), and dataset inclusion. Physiochemical properties were retrieved from PubChem [16].

| Full PhAC Name | Empirical Formula | CAS | Mw | pKa | log Kow | Dataset Membership Calibrated | Dataset Membership Screen |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amoxicilin | C16H19N3O5S | 26787-78-0 | 365.4 | 3.2; 11.7 | 0.87 | ✓ | ✓ |

| Atenolol | C14H22N2O3 | 29122-68-7 | 266.34 | 9.16 | 0.16 | ✓ | ✓ |

| Diazepam | C16H13ClN2O | 439-14-5 | 284.74 | 3.4 | 2.82 | ✓ | ✓ |

| Diclofenac | C14H11Cl2NO2 | 15307-86-5 | 296.1 | 4.15 | 4.51 | ✓ | ✓ |

| Carbamazepine | C15H12N2O | 298-46-4 | 236.27 | 13.9 | 2.77 | ✓ | ✓ |

| Procaine | C13H20N2O2 | 59-46-1 | 236.31 | 8.05 | 1.92 | ✓ | ✓ |

| Sulfamethazine | C12H14N4O2S | 57-68-1 | 278.33 | 2.65; 7.65 | 0.89 | ✓ | ✓ |

| Sulfamethoxazole | C10H11N3O3S | 723-46-6 | 253.28 | 1.6; 5.7 | 0.89 | ✓ | ✓ |

| Torasemide | C16H20N4O3S | 56211-40-6 | 348.4 | 7.1 | 3.36 | ✓ | ✓ |

| β-estradiol | C18H24O2 | 50-28-2 | 272.4 | 10.46 | 4.01 | ✓ | ✓ |

| Venlafaxine | C17H27NO2 | 93413-69-5 | 277.4 | 9.5 | 3.2 | ✓ | ✓ |

| O-Desmethylvenlafaxine | C16H25NO2 | 142761-12-4 | 263.37 | 9.45; 10.66 | 2.72 | ✓ | ✓ |

| Hydroxychloroquine | C18H26ClN3O | 118-42-3 | 335.9 | 9.67 | 3.6 | ✓ | ✓ |

| Metoclopramide | C14H22ClN3O2 | 364-62-5 | 299.79 | 9.3 | 2.66 | ✓ | ✓ |

| Trimethoprim | C14H18N4O3 | 738-70-5 | 290.32 | 7.12 | 0.91 | X | ✓ |

| Amitriptyline | C20H23N | 50-48-6 | 277.4 | 9.4 | 4.9 | X | ✓ |

| β-Sitosterol | C29H50O | 83-46-5 | 414.7 | - | 9.3 | X | ✓ |

| Miconazole | C18H14Cl4N2O | 22916-47-8 | 416.1 | 6.91 | 6.1 | X | ✓ |

| Clotrimazole | C22H17ClN2 | 23593-75-1 | 344.8 | 4.1 | 5.92 | X | ✓ |

| Dexamethasone | C22H29FO5 | 50-02-2 | 392.5 | 1.18; 3.4 | 1.83 | ✓ | X |

Each dataset folder (Calibrated/, Screen/) contains a master summary table, raw per-frame data, and simulation archives. The Calibrated master table (master_table_calibrated.xlsx) includes an overview sheet (Info) and three data sheets (Monomer_Energy, Polymer_Energy, DFT_Energy) listing pharmaceutical and polymer identifiers, predicted mean affinity (ΔG* for MM/PBSA and ΔG for DFT), and SD.

We additionally report a PhAC self-interaction metric (mean ΔG* and SD) obtained by running the same monomeric MM/PBSA pipeline on ligand-only boxes; this supports interpretation of concentration-dependent effects in pharmaceutical–polymer retention. The Screen workbook (master_table_screen.xlsx) also includes an overview sheet and a single “Data” sheet with the mean and SD of ΔG* across pharmaceutical–polymer pairs. Raw per-frame MM/PBSA energies are collected in a single CSV file, located in raw_data/ Energy_raw_data_multyterm.csv, with rows as trajectory frames and columns following the naming scheme {PolymerID}_{PhACID}_{term}. Terms include per-component energy contributions and the total (ΔG*). Molecular metadata in PhAC_data/ and Polymer_data/ (SMILES, formal charge, names/IDs) are provided for descriptor construction. Each simulation is archived in Simulations/ within the main ZIP containing the production trajectory (.xtc), topology (topol.top), and final equilibrated structure (.gro). Template inputs for PackMol, GROMACS, and gmx_MMPBSA (.inp, .mdp, .in) are provided in inputs/ to enable full reproducibility [7,11,17]. The primary quantitative output is the predicted binding affinity, obtained with gmx_MMPBSA. As absolute ΔG* values can shift across different polymer environments, comparisons are most reliable within a single polymer series. The DFT subset provides reference energies for cross-method benchmarking. All files are provided in open, machine-readable formats suitable for direct integration into statistical or machine learning pipelines.

Table 2.

Monomeric units included in MIP–PhAC datasets. Each row lists the monomer name, formula, CAS number, polymer type (neutral/anionic/cationic), number of monomers used in the simulation, and dataset inclusion. Monomer metadata (empirical formula, CAS) were obtained from the PubChem database [16].

Table 2.

Monomeric units included in MIP–PhAC datasets. Each row lists the monomer name, formula, CAS number, polymer type (neutral/anionic/cationic), number of monomers used in the simulation, and dataset inclusion. Monomer metadata (empirical formula, CAS) were obtained from the PubChem database [16].

| Full Monomer Name | Empirical Formula | CAS | Polymer Type | Simulation Size Monomeric (n) | Simulation Size Polymeric (Chains × Monomers) | Dataset Membership Calibrated | Dataset Membership Screen |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Methacrylic acid | C4H6O2 | 79-41-4 | Anionic | 87 | 20 × 10-mer | ✓ | ✓ |

| 4-Vinylpyridine | C7H7N | 100-43-6 | Neutral | 76 | 16 × 10-mer | ✓ | ✓ |

| 2-Hydroxyethyl methacrylate | C6H10O3 | 868-77-9 | Neutral | 69 | 13 × 10-mer | ✓ | ✓ |

| Oasis HLB *** | NA | NA | Neutral | 21 | 8 × 5-mer | ✓ | X |

| Acrylic acid | C3H4O2 | 79-10-7 | Anionic | 93 | - | X | ✓ |

| Itaconic acid | C5H6O4 | 97-65-4 | Anionic | 72 | - | X | ✓ |

| 2-(Trifluoromethyl)acrylic acid | C4H3F3O2 | 381-98-6 | Anionic | 75 | - | X | ✓ |

| 4-Vinylbenzoic acid | C9H8O2 | 1075-49-6 | Anionic | 60 | - | X | ✓ |

| Trans-3-(3-Pyridyl)acrylic acid | C8H7NO2 | 19337-97-4 | Anionic | 61 | - | X | ✓ |

| Allylamine | C3H7N | 107-11-9 | Cationic | 96 | - | X | ✓ |

| N-(2-Aminoethyl)acrylamide | C5H10N2O | 23918-29-8 | Cationic | 67 | - | X | ✓ |

| 2-(Diethylamino)ethyl methacrylate | C10H19NO2 | 105-16-8 | Cationic | 43 | - | X | ✓ |

| [2-(Trimethylammonio)ethyl] methacrylate | C9H18NO2 | 5039-78-1 | Cationic | 49 | - | X | ✓ |

| Methacrylamide | C4H7NO | 79-39-0 | Neutral | 86 | - | X | ✓ |

| Acrylamide | C3H5NO | 79-06-1 | Neutral | 92 | - | X | ✓ |

| Acrylonitrile | C3H3N | 107-13-1 | Neutral | 97 | - | X | ✓ |

| Methyl methacrylate | C5H8O2 | 80-62-6 | Neutral | 80 | - | X | ✓ |

| Ethylstyrene | C10H12 | 3454-07-7 | Neutral | 62 | - | X | ✓ |

| Styrene | C8H8 | 100-42-5 | Neutral | 75 | - | X | ✓ |

| N-Vinylpyrrolidone | C6H9NO | 88-12-0 | Neutral | 75 | - | X | ✓ |

| Ethyl urocanate (ethyl ester) | C8H10N2O2 | 27538-35-8 | Neutral | 55 | - | X | ✓ |

| 4-Vinylimidazole | C5H6N2 | 25189-76-8 | Neutral | 82 | - | X | ✓ |

| N-Vinylimidazole | C5H6N2 | 1072-63-5 | Neutral | 82 | - | X | ✓ |

| 2-Vinylpyridine | C7H7N | 100-69-6 | Neutral | 76 | - | X | ✓ |

*** commercialized sorbent, supplied by Waters; no single empirical formula; it is a copolymer.

3. Methods

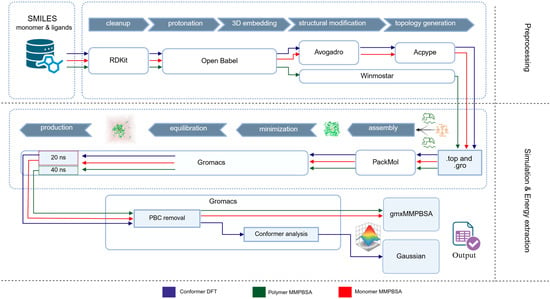

We generated two related MD datasets describing polymer–pharmaceutical interactions (see the Data Description section). Both datasets were produced using an integrated computational workflow for molecular preparation, simulation, and analysis, summarized in Figure 1. A detailed example of the data acquisition workflow is provided in Appendix A, using the 2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate and diazepam system as a representative case.

3.1. Molecule Preparation and Parameterization

Ligand structures were standardized from SMILES using RDKit (version 2023.09.4) and embedded/protonated with Open Babel (version 3.1.0) [8,9,18]. Molecular metadata form monomers and PhACs were retrieved from the PubChem database [16]. In MIP–PhAC-Calibrated, microstates were reviewed in Avogadro (version 1.2) and edited where necessary to reflect pH 7; MIP–PhAC-Screen retained the automated assignments [19]. Polymer environments were represented in two forms. For pre-polymerization, we used pools of a single unique functional monomer surrounding a single PhAC. To approximate post-polymerization packing, we constructed analogous systems composed of several short chains generated from monomer outputs with Winmostar V10 polymerization tools [20]. To avoid simulation instabilities while retaining sufficient functional monomers for meaningful sampling, monomeric systems used 30–100 monomers, scaled inversely with molecular volume to maintain a stable monomer to box volume ratio. Owing to their inherently greater stability, polymeric systems were packed at approximately twice the density used for monomeric simulations. All species were parameterized with GAFF2 via acpype (version 2023.10.27) (antechamber [AmberTools]) [10,21,22].

Figure 1.

Overview of the computational workflow used in the creation of the MIP_PhAC datasets. Schematic overview of the integrated pipeline for dataset generation and analysis. Ligand and polymer structures were standardized, protonated, and parameterized (top), assembled into solvated simulation boxes (middle), and simulated in GROMACS for 20 ns (monomeric) or 40 ns (polymeric) production runs. Post-processing included PBC correction, conformer analysis, and MM/PBSA or DFT energy calculations. Colored arrows indicate the three methodological branches used in this work: monomeric MM/PBSA, polymeric MM/PBSA, and the DFT reference subset. RDKit, Open Babel, Avogadro, Winmostar, PackMol, GROMACS, gmx_MMPBSA, and Gaussian were used as indicated. Created with BioRender.com [23].

3.2. System Assembly and Molecular Dynamics

Final topology assembly was performed with ParmEd (version 4.2.2) [24], which was used to merge acpype-generated topologies. Each system was packed in a 6 × 6 × 6 nm cubic box using PackMol (version 20.010) with a single PhAC in the center surrounded by {n} monomers/polymers (Table 2), solvated with SPC water, and neutralized with Na+/Cl− [17,25]. This box size was chosen based on preliminary tests showing that 4 nm boxes were unstable during NPT equilibration, while 6 nm and 8 nm boxes showed similar stability and energy profiles; 6 nm therefore provided the best balance between stability and computational efficiency. Simulations were performed in GROMACS 2023.1 using GAFF2 parameters for both pharmaceuticals and monomers/polymers [7]. After steepest-descent energy minimization, systems underwent three equilibration phases at 293.15 K with a 0.5 fs timestep: NVT with Nose–Hoover thermostat; NPT with Nose–Hoover thermostat and Berendsen barostat at 1 bar; and NPT with the Nose–Hoover thermostat and Parrinello–Rahman barostat at 1 bar [26,27,28,29]. Polymeric systems (4 unique polymers) exhibited equilibrated densities of 971.84–1076.03 kg·m−3 (lowest for HLB; highest for methacrylic acid). Monomeric simulations (24 unique monomers) ranged from 965.24 to 1040.02 kg·m−3 (lowest for ethylstyrene; highest for itaconic acid). These values fall within the expected range and confirm adequate packing across all simulations.

Production trajectories were then run for 20 ns for monomeric simulations and 40 ns for polymeric simulations using PME electrostatics (cutoff 1.2 nm), the Verlet scheme for nonbonded interactions, and a van der Waals cutoff of 1.2 nm with force-switch from 1.0 nm [30]. Thermal equilibration occurred rapidly under this protocol. Temperature profiles showed that monomeric systems reached thermal stability within ~5 ps, whereas polymeric systems stabilized within ~30 ps. From each trajectory we extracted 1000 frames for further analysis.

3.3. Convergence Assessment and Analysis Window

Trajectories were recentered (-center -pbc mol -ur compact) and aligned (rot + trans) to remove periodic boundary artifacts. We computed an average, scaled monomer/polymer RMSD and applied a 10-frame moving average. The stabilization time tstab was defined as the earliest time at which a subsequent 50-frame window remained within ±5% of its local mean. Across systems (434 monomeric and 60 polymeric), we then defined a global t95 as the 95th percentile of tstab. Monomeric systems stabilized rapidly (median 1.40 ns; t95 = 3.18 ns), whereas polymeric systems required longer sampling (median 6.24 ns; t95 = 19.17 ns). Based on this, we applied a conservative burn-in of 3.18 ns (monomeric) and 19.17 ns (polymeric) and analyzed only post-burn-in frames.

3.4. MM/PBSA Calculations

End-point binding energies were computed with gmx_MMPBSA v1.6.2 using

with the non-polar contribution modeled as SASA-only with the entropic term −TΔS omitted [11,12]. Poisson–Boltzmann settings followed the tool’s recommended parameters. Component and total energies were averaged over post-burn-in frames.

3.5. DFT Subset

For a subset of neutral ligand–fragment complexes, Gibbs free energies were evaluated using Gaussian 16 [31]. Structures were optimized with the B3LYP functional [32,33] and the 6-31+G(d,p) basis set. The Conductor-like Polarizable Continuum Model (CPCM) to account for solvent effects, with water as the solvent [34,35]. The binding energies were calculated from Gibbs free energy differences using the formula

where Gcomplex is the Gibbs free energy of the pharmaceutical–monomer complex, Gpharmaceutical is the Gibbs free energy of the free pharmaceutical, Gmonomer is the Gibbs free energy of the free monomer, and n is the number of monomer units, which varied depending on the stoichiometric ratio. The ratios for each pharmaceutical–monomer pair were systematically varied to explore the impact of stoichiometry on binding interactions. These calculations were performed to evaluate the stability and strength of the non-covalent interactions between the pharmaceuticals and monomers in aqueous environments.

4. User Notes and Data Limitations

The datasets are designed for (i) within-polymer ranking of PhACs, (ii) benchmarking end-point methods and workflow variants, and (iii) developing ML models that map ligand/polymer descriptors to MM/PBSA ranks. Monomeric systems approximate pre-polymerization chemistry; short-chain polymeric systems approximate local packing after polymerization. Neither reproduces full network topology, crosslink density, or porosity. Cooperative effects beyond the simulated length scales may be underrepresented. Known limitations are as follows: (i) The Screen dataset uses automated protonation; edge-case microstates (multiprotic/tautomeric species) can be misassigned; verify SMILES and charges if microstate sensitivity is important. (ii) Reported ΔG* from MM/PBSA excludes −TΔS and uses SASA-only for the non-polar term; treat values as interaction score, not as absolute binding free energies. (iii) Cross-polymer comparisons can drift due to dielectric and packing differences; prefer within-polymer ranking. (iv) Crosslinkers, porogens, salts, and co-monomers present in experimental MIPs are not modeled; when relating ΔG* to retention/adsorption, note that these missing components can affect selectivity and capacity. Future studies will expand solvent conditions and polymer chemistry, incorporate explicit crosslinkers/ions, refine microstate assignment, and provide replicated trajectories for uncertainty estimation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.M.P. and M.L.; methodology, D.V., D.M., and R.V.; software, D.V. and D.M.; validation, D.V., M.L., and D.M.; formal analysis, D.V.; investigation, D.V. and D.M.; resources, D.M.P. and M.L.; data curation, D.V. and D.M.; writing—original draft preparation, D.V., M.L., and D.M.; writing—review and editing, D.V., M.L., D.M., R.V., Ž.M., K.T.Č., and D.M.P.; visualization, D.V. and M.L.; supervision, D.M.P., M.L., and R.V.; project administration, D.M.P.; funding acquisition, D.M.P. and M.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Croatian Science Foundation under the project “Development of molecularly imprinted polymers for use in analysis of pharmaceuticals and during advanced water treatment processes” (MIPdePharma) (HRZZ-IP-2022-10-4400). M.L. received funding from Next Generation EU, grant number IA-INT-2024-BioAntroPoP.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The full dataset is available at DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.17743761.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript/study, the authors used ChatGPT 5.1 licensed to M.L. for improving coding pipelines. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication. M.L., D.M., and R.V. would like to acknowledge the Zagreb University Computing Centre (SRCE) for granting computational resources for the SUPEK cluster.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PhAC | Pharmaceutically active compound |

| MIP | Molecularly imprinted polymer |

| MD | Molecular dynamics |

| DFT | Density functional theory |

| MM/PBSA | Molecular Mechanics/Poisson–Boltzmann Surface Area |

| SPC | Simple Point Charge (water model) |

| GAFF2 | General AMBER Force Field 2 |

| RMSD | Root-mean-square deviation |

| PBC | Periodic boundary conditions |

| PME | Particle Mesh Ewald |

| NVT | Constant number, volume, temperature ensemble |

| NPT | Constant number, pressure, temperature ensemble |

| SASA | Solvent-accessible surface area |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| SMILES | Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System |

| CPCM | Conductor-like Polarizable Continuum Model |

| MK | Merz–Kollman (electrostatic potential charges) |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Worked Example: 2-Hydroxyethyl Methacrylate–Diazepam Workflow

To illustrate the complete workflow shown in Figure 1, we provide an example of how the data were obtained for the monomeric system composed of 2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate (HEMA) and diazepam. All files referred to below are included in the dataset archive under

MIP_PhAC\Example

Appendix A.1.1. Molecular Input and Standardization

- Specification of species

Pharmaceutical (PhAC)

- Pharmaceutical: diazepam

- ID: TDIA

- SMILES: CN1C(=O)CN=C(C2=C1C=CC(=C2)Cl)C3=CC=CC=C3

Functional monomer:

- Name: 2-Hydroxyethyl methacrylate (HEMA)

- ID: NHEM

- SMILES: CC(=C)C(=O)OCCO

- Standardization and 3D generation

SMILES were standardized using RDKit (fragment removal, valence normalization).

Protonation states were assigned for pH 7 with Open Babel, and one low-energy conformer per species was generated. Relaxation was performed using MMFF94 forcefield.

Output:

- T_TDIA.mol2

- P_NHEM.mol2

These MOL2 files serve as the input to the parameterization step.

Appendix A.1.2. Parameterization and Topology Generation

- GAFF2

- parameterization (acpype)

Both molecules were parameterized using acpype (AmberTools/antechamber backend) with GAFF2 and AM1-BCC charges:

acpype -i <molecule>.mol2 -c bcc -a gaff

Output folders:

- T_TDIA.acpype/

- P_NHEM.acpype/

Within each folder, acpype produced the following:

- <ID>_GMX.gro—GROMACS coordinates

- <ID>_GMX.itp—GROMACS include topology

- <ID>_GMX.top—standalone topology

- posre_<ID>.itp—position restraint file

- Monomer count selection

The number of HEMA monomers that will be used in the simulation was determined by comparing and scaling the molecular volume of all the functional monomers (using RDKit). For this monomer, n = 69 HEMA monomers.

Appendix A.1.3. System Assembly

- PackMol placement

A 3 × 3 × 3 nm cubic box was constructed with PackMol using script:

tolerance 2.0

filetype pdb

output system.pdb

structure TDIA.pdb

number 1

center

add_amber_ter

fixed 0. 0. 0. 0. 0. 0.

end structure

structure NHEM.pdb

number 69

inside box -15. -15. -15. 15. 15. 15.

add_amber_ter

outside sphere 0. 0. 0. 2.

end structure

- Topology merge (ParmEd)

A unified topology was constructed using ParmEd, combining ligand and monomer .itp files, positioning restraints, and including water/ion.

Outputs:

- topol.top

- system.gro

These constitute the full starting system.

Appendix A.1.4. Molecular Dynamics Simulation

MD was performed with GROMACS 2023.1 using GAFF2. All .mdp files are included in the example folder.

- Minimization and equilibration

- Minimization: steepest descent

- Equilibration:

- ○

- NVT (62.5 ps), Nose–Hoover, 293.15 K

- ○

- NPT (500 ps), Berendsen, 1 bar

- ○

- PT (500 ps), Parrinello–Rahman, 1 bar

- Production

- Duration: 20 ns

- PME electrostatics, 1.2 nm cutoffs

- 1000 trajectory frames written

- Outputs:

- step5_production_noIon.tpr

- step5_production_noIon.xtc

Appendix A.1.5. Trajectory Post-Processing

Trajectory conditioning was performed using the following:

gmx trjconv -center -pbc mol -ur compact

gmx trjconv -fit rot+trans

Output for analysis:

- cen_energy_fit.xtc

- Stabilization time inspection

Scaled RMSD with a 10-frame moving average placed the stabilization point of 95% of all the simulations (435 systems) at 3.18 ns (t95); therefore, only frames >3.18 ns were considered valid in the MM/PBSA results.

Appendix A.1.6. MM/PBSA Binding Energy Calculation

Binding energies were computed using gmx_MMPBSA v1.6.2.

Input:

- topol.top

- cen_energy_fit.xtc

- mmpbsa.in

Key parameters:

- Polar solvation: PB with default gmx_MMPBSA settings

- Non-polar solvation: SASA-only

- Entropy (−TΔS): omitted in ΔG*

- Outputs

- FINAL_RESULTS_MMPBSA.csv (Per-frame CSV)

Energy results for the HEMA x diazepam system:

| Energy term | Value (kcal·mol−1) |

| Electrostatic | −2.2 ± 2.8 |

| van der Waals | −15.1 ± 7.6 |

| Polar solvation | +9 ± 5.3 |

| Non-polar solvation | −2.2 ± 0.9 |

| ΔG* | −10.5 ± 5.2 |

The corresponding columns appear in the following:

Energy_raw_data_multyterm_monomeric.csv; (NHEM_TDIA)

Appendix A.1.7. Files Provided for the Example

Molecule-level inputs

- <ID>.mol2

- <ID>_GMX.itp, <ID>_GMX.top, <ID>_GMX.gro, posre_<ID>.itp

Assembled system

- system.pdb, system.gro, topol.top

Simulation files

- step5_production_noIon.tpr, step5_production_noIon.xtc

- step4.{1-3}_equilibration_noIon.mdp

- step5_production_noIon.mdp

Post-processed data

- cen_energy_fit.xtc

- index.ndx

- mmpbsa.in

Energy outputs

- FINAL_RESULTS_MMPBSA.csv

References

- Duan, L.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, B.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, F.; Sui, Q.; Xu, D.; Yu, G. Seasonal Occurrence and Source Analysis of Pharmaceutically Active Compounds (PhACs) in Aquatic Environment in a Small and Medium-Sized City, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 769, 144272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Royano, S.; Navarro, I.; de la Torre, A.; Martínez, M.Á. Investigating the Presence, Distribution and Risk of Pharmaceutically Active Compounds (PhACs) in Wastewater Treatment Plants, River Sediments and Fish. Chemosphere 2024, 368, 143759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Song, Y.; Deng, N.; Ren, Y.; Ma, R.; Jiang, K. Novel Insights into the Morphological Effects of Trace Organic Contaminants on Water/PhAC Selectivity in Nanofiltration of Sewage. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 497, 139672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajpal, S.; Mishra, P.; Mizaikoff, B. Rational In Silico Design of Molecularly Imprinted Polymers: Current Challenges and Future Potential. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 6785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zare, E.N.; Fallah, Z.; Le, V.T.; Doan, V.-D.; Mudhoo, A.; Joo, S.-W.; Vasseghian, Y.; Tajbakhsh, M.; Moradi, O.; Sillanpää, M.; et al. Remediation of Pharmaceuticals from Contaminated Water by Molecularly Imprinted Polymers: A Review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2022, 20, 2629–2664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowdon, J.W.; Ishikura, H.; Kvernenes, M.K.; Caldara, M.; Cleij, T.J.; van Grinsven, B.; Eersels, K.; Diliën, H. Identifying Potential Machine Learning Algorithms for the Simulation of Binding Affinities to Molecularly Imprinted Polymers. Computation 2021, 9, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, M.J.; Murtola, T.; Schulz, R.; Páll, S.; Smith, J.C.; Hess, B.; Lindahl, E. GROMACS: High Performance Molecular Simulations through Multi-Level Parallelism from Laptops to Supercomputers. SoftwareX 2015, 1–2, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Boyle, N.M.; Banck, M.; James, C.A.; Morley, C.; Vandermeersch, T.; Hutchison, G.R. Open Babel: An Open Chemical Toolbox. J. Cheminform. 2011, 3, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- RDKit. Available online: https://www.rdkit.org/ (accessed on 2 November 2025).

- He, X.; Man, V.H.; Yang, W.; Lee, T.-S.; Wang, J. A Fast and High-Quality Charge Model for the next Generation General AMBER Force Field. J. Chem. Phys. 2020, 153, 114502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdés-Tresanco, M.S.; Valdés-Tresanco, M.E.; Valiente, P.A.; Moreno, E. gmx_MMPBSA: A New Tool to Perform End-State Free Energy Calculations with GROMACS. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2021, 17, 6281–6291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massova, I.; Kollman, P.A. Combined Molecular Mechanical and Continuum Solvent Approach (MM-PBSA/GBSA) to Predict Ligand Binding. Perspect. Drug Discov. Des. 2000, 18, 113–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutavdžić Pavlović, D.; Nikšić, K.; Livazović, S.; Brnardić, I.; Anžlovar, A. Preparation and Application of Sulfaguanidine-Imprinted Polymer on Solid-Phase Extraction of Pharmaceuticals from Water. Talanta 2015, 131, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Row, K.H. Characteristic and Synthetic Approach of Molecularly Imprinted Polymer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2006, 7, 155–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Introduction to Molecularly Imprinted Polymer. In Interface Science and Technology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; Volume 33, pp. 511–556.

- Kim, S.; Thiessen, P.A.; Bolton, E.E.; Chen, J.; Fu, G.; Gindulyte, A.; Han, L.; He, J.; He, S.; Shoemaker, B.A.; et al. PubChem Substance and Compound Databases. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, D1202–D1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez, L.; Andrade, R.; Birgin, E.G.; Martínez, J.M. PACKMOL: A Package for Building Initial Configurations for Molecular Dynamics Simulations. J. Comput. Chem. 2009, 30, 2157–2164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riniker, S.; Landrum, G.A. Better Informed Distance Geometry: Using What We Know To Improve Conformation Generation. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2015, 55, 2562–2574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanwell, M.D.; Curtis, D.E.; Lonie, D.C.; Vandermeersch, T.; Zurek, E.; Hutchison, G.R. Avogadro: An Advanced Semantic Chemical Editor, Visualization, and Analysis Platform. J. Cheminform. 2012, 4, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Themefisher Winmostar (TM). Available online: https://winmostar.com (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Sousa da Silva, A.W.; Vranken, W.F. ACPYPE—AnteChamber PYthon Parser interfacE. BMC Res. Notes 2012, 5, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Case, D.A.; Aktulga, H.M.; Belfon, K.; Cerutti, D.S.; Cisneros, G.A.; Cruzeiro, V.W.D.; Forouzesh, N.; Giese, T.J.; Götz, A.W.; Gohlke, H.; et al. AmberTools. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2023, 63, 6183–6191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scientific Image and Illustration Software|BioRender. Available online: https://www.biorender.com/ (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Shirts, M.R.; Klein, C.; Swails, J.M.; Yin, J.; Gilson, M.K.; Mobley, D.L.; Case, D.A.; Zhong, E.D. Lessons Learned from Comparing Molecular Dynamics Engines on the SAMPL5 Dataset. J. Comput. Mol. Des. 2016, 31, 147–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berendsen, H.J.C.; Grigera, J.R.; Straatsma, T.P. The missing term in effective pair potentials. J. Phys. Chem. 1987, 91, 6269–6271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parrinello, M.; Rahman, A. Polymorphic Transitions in Single Crystals: A New Molecular Dynamics Method. J. Appl. Phys. 1981, 52, 7182–7190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, D.J.; Holian, B.L. The Nose–Hoover Thermostat. J. Chem. Phys. 1985, 83, 4069–4074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berendsen, H.J.C.; Postma, J.P.M.; van Gunsteren, W.F.; DiNola, A.; Haak, J.R. Molecular Dynamics with Coupling to an External Bath. J. Chem. Phys. 1984, 81, 3684–3690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nosé, S. A Molecular Dynamics Method for Simulations in the Canonical Ensemble. Mol. Phys. 1984, 52, 255–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darden, T.; York, D.; Pedersen, L. Particle Mesh Ewald: An N⋅log(N) Method for Ewald Sums in Large Systems. J. Chem. Phys. 1993, 98, 10089–10092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisch, M.J.; Trucks, G.W.; Schlegel, H.B.; Scuseria, G.E.; Robb, M.A.; Cheeseman, J.R.; Scalmani, G.; Barone, V.; Petersson, G.A.; Nakatsuji, H.; et al. Gaussian 16, Revision B.01; Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford, CT, USA, 2016; GaussView 5.0. Wallingford, E.U.A. Available online: https://gaussian.com/ (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Lee, C. Development of the Colle-Salvetti Correlation-Energy Formula into a Functional of the Electron Density. Phys. Rev. B 1988, 37, 785–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becke, A.D. Density-functional Thermochemistry. III. The Role of Exact Exchange. J. Chem. Phys. 1993, 98, 5648–5652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barone, V.; Cossi, M. Quantum Calculation of Molecular Energies and Energy Gradients in Solution by a Conductor Solvent Model. J. Phys. Chem. A 1998, 102, 1995–2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cossi, M.; Rega, N.; Scalmani, G.; Barone, V. Energies, Structures, and Electronic Properties of Molecules in Solution with the C-PCM Solvation Model. J. Comput. Chem. 2003, 24, 669–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).