Abstract

Kombucha’s growing popularity worldwide has been accompanied by a growing consumer interest in exploring new flavors and adopting healthier diets. In this preliminary consumer-driven study, we investigated the application of white hibiscus (WH) calyces in the development of novel kombucha beverages. Kombuchas were made from 100% black tea (BT), 100% WH, and 50% BT/WH blend infusions, then their pH, total titratable acidity (TTA), ethanol content, sucrose, glucose, and fructose concentrations were measured. Untrained sensory participants (N = 97) rated the kombuchas using a 9-point hedonic scale, described them using a check-all-that-apply list of attributes, and answered a willingness-to-pay (WTP) question. Tea infusion and fermentation time had a significant effect on pH, TTA, ethanol, sucrose, fructose, and glucose content (p < 0.05). High residual sugar levels observed in the WH kombucha indicated sluggish fermentation. Kombuchas differed significantly in overall-liking, color, aroma, flavor, and mouthfeel liking, and WTP (p < 0.05). Overall, BT kombucha was preferred over the WH kombuchas (100% and blend). Sensory attributes “refreshing”, “floral”, “hibiscus”, “fruity”, and “sweet” were positive drivers of acceptability, while “pungent” and “astringent” were negative drivers. Results suggest that blends containing less than 50% WH may provide more appealing sensory attributes to consumers, and that further study is needed.

1. Introduction

The functional beverage segment is the fastest-growing sector within the functional food market [1]. Among these beverages, kombucha is rapidly growing in popularity and is positioned as a healthy alternative due to its perceived health benefits. Kombucha is traditionally made from sweetened Camellia sinensis black or green tea infusion and is a rich source of bioactive compounds, which are associated with the phenolic compounds in the tea [2].

The use of alternative raw materials such as herbs, fruits, leaves, and flowers enables the production of kombuchas with distinct sensory and physicochemical properties, which provides an opportunity for product diversification, flavor innovation, and the expansion of nutritional value in kombucha [3,4,5]. Among these alternative ingredients for kombucha making, roselle (Hibiscus sabdarrifa L.) is a perennial herbaceous shrub belonging to the Malvaceae family and genus Hibiscus that comes in varying colors (e.g., dark red, green, and white), with the red and dark red roselle being the most common varieties used in beverages [6,7]. Consumption of roselle (hibiscus) beverages has been associated with health benefits, including the management of high blood pressure and diabetes [8,9,10]. Although very limited studies have been conducted on white roselle (white hibiscus), researchers have documented that, similar to the red hibiscus, it contains polyphenols, flavonoids, phenolic acids, and organic acids, with the most abundant organic acids being hibiscus acids, followed by their demethylated derivative, known for its weight loss potential [11,12].

Differences in composition may lead to differences in perceived sensory properties, which can affect consumer acceptance of a new food product or beverage. White hibiscus extracts contain higher flavonoid and phenolic acid content and have demonstrated stronger antibacterial activity than red hibiscus extracts [13,14]. When compared to red hibiscus, the white variety also has greater contents of organic acids, which contribute to the characteristic sour taste associated with hibiscus-based products [15]. The higher titratable acidity in both calyces and seeds of white hibiscus compared to the red variety can influence its overall aroma and flavor [16]. In addition, white hibiscus calyces have also been reported to have a high mineral content [17].

Typically, the fermentation of alternative substrates by the symbiotic culture of bacteria and yeast (SCOBY) impacts the nutritional value of the kombucha beverages, and it may lead to differences in phenolic compounds and antioxidant activity [3]. For instance, kombucha made with a substrate mixture of cascara, hibiscus, and red ginger extracts exhibited high antioxidant activity, with up to 93.08% radical scavenging, thereby enhancing the beverage’s functional potential and contributing to a unique, appealing sensory profile [18]. In another study, kombucha made from red hibiscus presented distinct volatile compounds and flavor profile in comparison to traditional tea-based kombuchas [19]. Moreover, it has been reported that sugar consumption in kombucha production is substrate-dependent, which has a significant impact on taste [20]. The objective of this preliminary study was to test the application of white hibiscus, a potential ingredient rich in bioactive compounds, in kombucha production and evaluate the impact of this novel ingredient on fermentation dynamics (physical and chemical changes) and on consumer perceptions of the kombucha beverages.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Kombucha Samples

Dried white hibiscus calyces were purchased from Zhicay Foods (Corona, NY, USA), and Keemun black tea was purchased from Floating Leaves Tea (Seattle, WA, USA). Cane sugar (Domino Foods, Inc.; West Palm Beach, FL, USA) and distilled water (Kroger Co.; Cincinnati, OH, USA) were purchased from a local grocery store. The SCOBYs used in this study were sourced from White Labs (San Diego, CA, USA; six batches) and Fermentaholics (Clearwater, FL, USA; three batches) and combined into a custom SCOBY. This custom SCOBY was used to inoculate the tea infusions.

Kombucha beverages were prepared in triplicate from the following tea infusions: 100% white hibiscus (WH), 100% black tea (BT), and a blend (50% WH, 50% BT). Distilled water was boiled in steel cooking pots, then tea substrates (15 g total) were steeped in one gallon (3.785 L) of boiled water for 20 min. For each gallon (3.785 L) of the 50% blend (BT/WH) kombucha, 7.5 g of white hibiscus and 7.5 g of black tea were used. After brewing, teas were sieved using a stainless-steel strainer into a fermentation jar with a spigot. For each jar, half a cup of table sugar (~100 g) was added, and the mixture was stirred with a stainless-steel spoon until fully dissolved. The sweetened infusions were allowed to cool to room temperature (~25 °C). Next, ~200 mL of previously brewed kombucha (starter tea), 300 mg of Fermaid OTM yeast nutrients (Lallemand Inc., Montreal, QC, Canada), and a portion of SCOBY were added and gently mixed with a stainless-steel spoon. To homogenize the microbial community and reduce variability, all SCOBY pellicles were combined, mixed, and then equally distributed among all nine fermentation jars. The jars were then covered with a breathable cheesecloth secured with an elastic band and stored in a dark environment at room temperature (25 °C) for primary fermentation. On day 8, 100 g of sugar was dissolved in 100 mL of distilled water and transferred into the fermentation jars via the spigot; the contents were gently stirred for 1–2 min. Samples for chemical analyses were withdrawn, stored at −20 °C, and later thawed at 4 °C prior to analysis. At the end of the fermentation, SCOBYs were removed, and the kombuchas were refrigerated at 4 °C to slow the fermentation process. Approximately 475 mL of kombucha from each jar was dispensed into a 500 mL flip-top bottle and corked for secondary fermentation (carbonation) for 7 days. The carbonated kombuchas were then stored at 4 °C until sensory evaluation.

2.2. Chemical Analysis

2.2.1. pH Analysis

The pH of the kombuchas was measured using a Thermoscientific Orion Versaster pH meter (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) calibrated with 4.00, 7.00, and 10.00 buffer solutions (Fisher Chemical SB115-500 Lot 221687 and SB107-500 Lot 221685; Fisher Chemical, Fair Lawn, NJ, USA). The pH meter electrode (Orion 8107B NUMD) was immersed in the kombucha samples to measure their pH and rinsed with distilled water between samples. The pH readings were taken on days 0, 4, 7, 8, 11, 14, and 18.

2.2.2. Sample Preparation for Chemical Analysis

Prior to the measurement of pH, TTA, ethanol, and sugar concentrations, samples were centrifuged with an Accuspin Micro 17 R microcentrifuge at 3000× g for 5 min (Fisherbrand, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and filtered through a 45 um filter to remove sediments or suspended particles and ensure a homogeneous sample.

2.2.3. Determination of Total Titratable Acidity (TTA)

Potentiometric titration determines the endpoint by measuring the change in electrical potential (voltage or pH) using an electrode, rather than relying on a color change. Total titratable acidity (TTA) was measured using a potentiometric titration method described in 21 CFR 114.90, “Titratable Acidity by Glass Electrode”, which references AOCS 22.061, “Titratable Acidity—Glass Electrode Method”, from AOAC Official Method 942.15 [21]. NaOH concentration was standardized with anhydrous potassium acid phthalate. Titration endpoint was determined in triplicate by titrating to pH 8.2 using a calibrated (pH 4.0, 7.0, 10.0) hydrogen ion (pH) glass electrode (Fisher Scientific, St Louis, MO, USA). Acidity was calculated by converting milliequivalents (meq) of titrated NaOH to meq of acetic acid, then to % acetic acid. The kombucha samples were degassed by sonicating to minimize the effect of carbonation in the analysis. For each sample, 200 mL of distilled water was placed in a beaker on a stirrer, and 5 mL of the test sample was added to the water and stirred continuously. Prior to titration, the initial volume of NaOH was recorded. The sample was then titrated potentiometrically with 0.1 M NaOH to a pH of 8.2, and the final volume was recorded. NaOH was standardized with potassium acid phthalate before use.

2.2.4. Determination of Alcohol Content

Ethanol content in kombucha samples was quantitatively determined using gas chromatography with flame ionization detection (FID). This method was adapted from a previously established procedure (JAOAC 66, 1152, 1983). A Hewlett-Packard Model 5890 (Hewlett-Packard Model 5890 CO, Palto Alto, CA, USA) gas chromatograph was equipped with a split-splitless/injector, FID, and an integrator was employed for the analysis. Separation was done using a 30 m × 0.53 mm 1.0 micron film thickness DB-WAXETR (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) wide bore polyethylene glycol-based capillary column. Prior to analysis, the air and hydrogen flow for the flame detector were optimized for the carrier gas flow. All sample and standard dilutions were performed with a diluter capable of ±0.1% precision.

For calibration, an alcohol standard solution was prepared with a concentration approximating 0.5%, which is the expected maximum ethanol content of the kombucha samples. The exact alcohol percentage of this solution was precisely determined by a pycnometer. Furthermore, a 0.2% (v/v) solution of 2-propanol in deionized water was used as the internal standard. To create the standard curve, the alcohol standard solution was diluted 1:100 with the internal standard solution. Then, at least three 1.0 μL aliquots of this mixture were injected into the gas chromatograph, and the average response ratio (RR) of the area of the ethanol peak to the area of the 2-propanol peak was calculated. For each kombucha sample, a 1:100 dilution with the internal standard solution was prepared, and a 1.0 μL aliquot was injected. The response ratio (RR) for the sample was then determined. The final ethanol concentration was calculated using the following equation:

Ethanol Concentration (sample) (% v/v) =

(RR (sample)/RR (standard)) × Ethanol Concentration (standard) (% v/v)

(RR (sample)/RR (standard)) × Ethanol Concentration (standard) (% v/v)

2.2.5. Determination of Total Sugars Using the Enzymatic Method

Sugar content was determined using the Megazyme sucrose/fructose/D-glucose kit (Cat. No: K-SUFRG, Lot 240516-01), following the manufacturer’s instructions for samples within the range of 0.04–0.8 g/L. Samples were diluted 50-fold by adding 20 μL of sample to 980 μL of distilled water. For sucrose determination, 20 μL of fructosidase (bottle 6) was added to a 96-well plate, followed by 10 μL of sample and mixing for 5 min. Subsequently, 190 μL distilled water, 10 μL buffer (bottle 1), and 10 μL NADP/ATP (bottle 2) were added, and absorbance was measured at 340 nm (A1). After adding 2 μL HK/G6P-DH (bottle 3), absorbance was measured again (A2) after 5 min of mixing. For D-glucose/D-fructose, 210 μL distilled water, 10 μL buffer, 10 μL NADP/ATP, and 10 μL sample were mixed, and absorbance was recorded at 340 nm (A1). After adding 2 μL HK/G6P-DH (bottle 3), absorbance was measured (A2), followed by addition of 2 μL PGI (bottle 4) and a final absorbance reading (A3) after 10 min. Changes in absorbance (A2–A1 for sucrose and glucose; A3–A2 for fructose) were calculated and corrected using kit-provided factors to obtain concentrations in g/L. Total reducing sugars were calculated as the sum of glucose and fructose. All measurements were performed in triplicate, and calibration was performed using known sugar standards as per the kit instructions. All absorbance measurements at 340 nm were performed using a Thermo Scientific GENESYS UV-Vis spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

2.3. Sensory Evaluation

Sensory evaluation of the three kombucha beverages (BT, WT, and blend) was conducted at the Virginia Tech Sensory Evaluation Laboratory (Blacksburg, VA, USA) in March 2025. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Virginia Tech Institutional Review Board (IRB 24-1089) before any data were collected from human subjects. Participants were recruited from the university and the surrounding area through direct emails, listservs, flyers, and/or word of mouth. Participation was voluntary and open to individuals of any gender or ethnicity who consume kombucha products, were at least 18 years old, not pregnant or breastfeeding, and not allergic to hibiscus or kombucha products. Prior experience in sensory evaluation was not required, and volunteers were offered snacks as a token of our appreciation. A total of 97 untrained adult volunteers participated in the study and completed all tasks. The demographic and consumer profile of the participants is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographics and consumer profile of sensory participants.

The sensory study consisted of hedonic testing followed by check-all-that-apply (CATA) and willingness-to-pay (WTP) questions, as well as a short survey that contained demographic and behavioral questions. The CATA list contained 26 descriptors and the “other(s)” option, and it was built after preliminary tasting of the products, discussion, and agreement among members of the research team. The CATA list consisted of the 5 basic tastes (sweet, sour, salty, bitter, and umami) and 21 sensory attributes commonly used in the literature to describe aroma, flavor, and mouthfeel of kombuchas and/or non-alcoholic beverages (bubbly, clear, cloudy, floral, berry fruit, earthy, herbal, tea-like, fermented, pungent, tangy, tart, vinegary, fruity, hibiscus, fizzy, refreshing/fresh, watery, full-bodied).

Sensory data were collected using Compusense Cloud® (Compusense Inc., Guelph, ON, Canada). Kombucha samples (¾ oz; ~22 mL) were served to panelists in disposable clear 2 oz soufflé cups with lids, which were labeled with a three-digit random code to avoid bias. Samples were served one at a time, and a balanced design was chosen. Panelists were asked to evaluate overall liking and attribute liking (color, aroma, flavor and mouthfeel) of each sample using a 9-point hedonic scale (“1—dislike extremely”; “9—like extremely”), describe their sensory characteristics using the CATA list, and use a linear scale (range = USD 0.00–USD 4.00) to answer how much they were willing to pay for the sample tasted (price per 16 fl oz (473 mL)). Their last task was to complete a short questionnaire containing demographic and behavioral questions, such as gender identification, age, ethnicity, education level, kombucha consumption frequency, consumption of other non-alcoholic beverages, and barriers to consuming kombucha.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Microsoft Excel (Microsoft 365 MSO, Version 2507 Build 16.0.19029.20136, 64-bit), R (version 4.4.1 “Race for Your Life”, released in 2024), and R Studio (version 2024.12.1+563, “Kousa Dogwood”, released in 2025) were used for statistical analysis. All analyses employed a significance criterion of p ≤ 0.05. Two-way analyses of variance (ANOVAs) were conducted to determine the effects of tea type and fermentation time on the average pH, total titratable acidity, ethanol content, and concentrations of sucrose, glucose, and fructose. Average liking scores and average WTP values were evaluated using one-way analyses of variance (ANOVAs). Post hoc comparisons were conducted using Tukey’s Honestly Significant Difference (HSD) tests to identify significant differences among groups. For the CATA data, binary codes of 0 and 1 were assigned to the unchecked and checked descriptors, respectively. Correspondence analysis (CA) was conducted to investigate the relationships between sensory attributes and different kombuchas. Penalty analysis was performed to understand the impact of the sensory descriptors on overall liking scores. Additionally, ChatGPT (GPT-4 version) was used to refine R codes for data analysis.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Chemical Analysis

3.1.1. pH, Total Titratable Acidity, and Alcohol Content

The pH, total titratable acidity (TTA), and alcohol (ethanol) content of the three beverages (100% BT, 100% WH, and 50% BT/WH blend) over an 18-day fermentation time are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

pH, total titratable acidity (TTA), and alcohol over an 18-day fermentation time *.

The pH is an important parameter that influences the course of kombucha fermentation and affects chemical and sensory properties, nutritional quality, and microbiological safety of kombucha beverages [22]. Tea infusion type, fermentation time, and the interaction factor (p < 0.05) all had significant effects on kombucha pH (p < 0.05). Post hoc analysis revealed that the pH of all beverages differed significantly (p < 0.05), which possibly reflects significant differences in the chemical composition of the substrates used for kombucha fermentation. As expected, the pH of all beverages decreased as fermentation progressed, indicating that the growth of fermenting microorganisms and metabolic activities successfully resulted in the production of organic acids. The accumulation or increase of these organic acids increased the hydrogen ion concentration, resulting in lowered pH values [23,24]. These lower pH environments are important because they prevent the growth of harmful pathogenic microorganisms [25]. However, the differences in the chemical composition of the substrates may have impacted how the SCOBY interacted with them.

The highest pH values were observed for the 100% BT, which also showed a faster pH decrease rate. This may be due to higher amounts of fermentable nutrients like caffeine and nitrogen found in black tea, which provide nourishment that stimulates the growth of acetic acid bacteria (AAB) and yeast, resulting in faster breakdown of sugars and accumulation of acids [23]. The 100% WH had the lowest pH values and showed a slower pH change. White hibiscus has a high organic acid content and can initially create a highly acidic environment during kombucha fermentation. The absolute changes in pH over the 18-day fermentation were −0.65, −0.28, and −0.36 for the black tea, white hibiscus, and 50:50, respectively. Although the black tea pH decreased the most, it was still higher than the formulations containing white hibiscus at the end of fermentation. The final pH values of the beverages in Table 2 are comparable to those reported for commercial kombuchas brewed mainly from black and green Camellia sinensis teas in Argentina, which showed pH values between 2.69 and 3.80 [26,27] and align with the typical range (2.5–3.5). This confirms that, despite the different substrate, our fermentation achieved the characteristic acidity essential for kombucha’s safety and profile. The optimal pH range for yeast activity is between 4.5 and 6.5, depending on the specific yeast strain [24]. The starting pH of all our infusions was lower than this range, which is somewhat acidic for yeast metabolism. This acidic environment can suppress yeast activity, slowing the breakdown of sugar and acid production. It is possible that the slight increase observed on pH of the 100% WH beverage on day 8 may have been influenced by a buffering effect of dissolved CO2 produced during fermentation [28]. Additionally, the optimal pH for yeast activity is not reported in the presence of a SCOBY or other microorganisms. Further investigation is needed to understand the reason behind this observation.

Total titratable acidity (TTA) of the three beverages was measured throughout the 18-day fermentation period, and mean values plus standard deviations are reported in grams per liter (g/L) of acetic acid equivalent in Table 2. TTA measures the total concentration of organic acids in a food [29], and it generally increases across all beverages throughout the fermentation period. This result is expected in kombucha fermentation, as bacteria and yeast metabolize sugars into organic acids [30]. In kombuchas, TTA reflects the fermentation dynamics and the total acid profile of the products. Thus, while acetic acid is typically the dominant organic acid produced by the SCOBY [24], TTA also accounts for other acids generated during fermentation (e.g., gluconic acid, lactic acid) as well as those naturally present in the initial tea infusion (e.g., citric, malic, and tartaric acids from hibiscus) [11,31].

TTA followed the same trends observed for pH; higher TTA values in the tea infusions were associated with low pH values (Table 2). Tea infusion, fermentation time, and their interaction had a significant effect on the kombucha’s TTA (p < 0.05). Significant TTA differences were observed between the 100% WH and 100% BT kombuchas (p < 0.05), as well as between the 50% blend (WH/BT) and the 100% BT (p < 0.05). No statistical difference was found between the 50% blend and the 100% WH beverages (p > 0.05). TTA levels changed significantly (p < 0.05) throughout the fermentation period, and the TTA patterns differed based on the fermentation days. On days 0 and 4, no significant difference was found in the TTA values among the tea types (p > 0.05). On day 7, TTA values of the 100% BT and the 100% WH were statistically different (p < 0.05), while no statistical difference was found between either the 100% BT or the 100% WH and the 50% blend (p > 0.05). After sugar was added to the beverages on day 8, 100% BT kombucha consistently had significantly lower TTA values than both 100% WH and the 50% blend (p < 0.05). However, no significant difference was found between 100% WH and 50% blend during this period (p > 0.05).

In general, a distinct order of TTA was observed, with the 100% WH and the 50% blend kombuchas having significantly higher TTA values than the 100% BT kombucha. Moreover, Tukey’s HSD test revealed significant differences between the TTA values of the 100% WH and the 100% BT (p < 0.05) from the seventh day. The effect of the tea type on total acidity may be attributed to the inherent characteristics of the tea type. For example, white hibiscus is inherently a natural source of organic acids [11,31], which contribute to the overall acid profile. Typically, hibiscus calyces are reported to have high concentrations of citric acid, hydroxycitric acid, hibiscus acid, malic acid, and tartaric acid [11]. The intrinsic acids contribute directly to the initial TTA of unfermented tea, setting the pace for a higher TTA baseline compared to the black tea kombucha. Furthermore, the significant interaction effect (p < 0.05) suggests that acidification during the 18-day fermentation period was not uniform across all tea types. During the initial fermentation days, TTA values followed an increasing trend but showed no significant differences among tea types (100% WH: 1.67 ± 0.60 g/L; blend: 1.44 ± 0.34 g/L; 100% BT: 1.05 ± 0.23 g/L). The low concentration of organic acids in the initial fermentation days may be linked to an insufficient amount of glucose for acetic acid synthesis [24,32]. By the end of fermentation, the 100% BT exhibited a significantly lower TTA (6.52 ± 0.12 g/L) compared to both 100% WH (10.09 ± 0.82 g/L) and the 50% blend (10.55 ± 1.96 g/L), with no significant difference between the latter two. Moreover, consistently, from day 7 onwards, TTA values of the 100% WH and 100% BT beverages differed significantly (p < 0.05). However, the TTA value of the blend did not differ significantly from the 100% WH. In addition, the acidity profile had an impact on sugar metabolism and alcohol production. Consistent high acid production and low pH were observed in the 100% WH kombucha, which may have contributed to the stuck fermentation observed in this tea type.

Alcohol (ethanol) content in kombucha is a critical parameter for regulatory compliance, public health and safety, religious requirements, and process control. The United States Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau requires that kombucha classified as a non-alcoholic beverage be less than 0.5% (v/v). Alcohol in kombucha fermentation is produced from the yeast’s metabolism of sugars into ethanol and CO2 [24]. All beverages produced in this study had alcohol content below the regulatory maximum and were classified as non-alcoholic beverages.

Both tea infusion and fermentation time had a significant effect on alcohol content (p < 0.05), but their interaction factor was not significant (p > 0.05). Alcohol content was significantly different between 100% BT and 100% WH beverages, as well as between the 50% BT/WH blend and the 100% WH kombuchas (p < 0.05). No statistical difference was found between the 100% BT and the 50% blend (p > 0.05).

Overall, alcohol concentrations were higher in the 100% BT kombucha than in the other two beverages. Yeast breaks down sucrose using the enzyme invertase into glucose and fructose, then utilizes the monosaccharides, preferably glucose, as their fermentable substrate to produce ethanol through a glycolytic pathway, increasing the alcohol content. Subsequently, AAB utilizes glucose to produce gluconic acid. As fermentation progresses, AAB uses the ethanol produced by yeasts to form acetic acid, thereby reducing the alcohol content [33,34,35]. The higher alcohol content in 100% BT suggests higher active sugar utilization by yeasts in this infusion, which may be partially attributed to the chemical composition of black tea. A previous study indicated that the processing method and tea leaf size have an impact on the chemical composition of tea infusion [35]. Black tea used in our study had a loose-leaf form compared to the white hibiscus calyces. This may have influenced the extraction of its tea components, leading to a more efficient use of the substrate, a faster reaction rate, and subsequently increased ethanol content [35]. Furthermore, black tea contains compounds such as caffeine, theophylline, and theobromine, which affect yeast metabolism and ethanol yield [33]. The relatively low ethanol content observed in the 100% WH kombucha may be attributed to the inefficient utilization of residual sugars by the yeast, resulting in a stuck fermentation. The decrease in ethanol content observed after reaching peak levels suggests that AAB utilized ethanol to produce acetic acid. The interaction between fermentation time and tea infusion was not statistically significant (p > 0.05). The results suggest that the effect of fermentation time on alcohol content was consistent across all tea infusions.

3.1.2. Sugar Content (Sucrose, Glucose, and Fructose)

Sucrose, glucose, and fructose concentrations were quantified to understand the sugar metabolism during the 18-day kombucha fermentation time (Table 3). A fed-batch fermentation strategy was employed, with an additional 100 g/L of sucrose added to all fermentation vessels on day 8, which explains the increased concentrations on day 8 observed in all beverages.

Table 3.

Sucrose, glucose, and fructose concentrations (g/L) over an 18-day fermentation time *.

The effects of tea infusion, fermentation time, and the interaction between them were significant on fructose concentration as well as on glucose concentration (p < 0.05). Both tea infusion and fermentation time had a significant effect on sucrose concentration (p < 0.05), but the interaction effect was not statistically significant (p > 0.05). Sucrose concentrations between the 100% WH and 100% BT beverages were significantly different (p < 0.05). Sucrose content of the blend was not significantly different from the 100% WH (p > 0.05), but it was significantly different from the 100% BT kombucha (p < 0.01). Sucrose changes over fermentation time were largely similar across all the tea types.

Sucrose is a disaccharide consisting of two monomers, glucose and fructose, joined chemically by a glycosidic bond; it can be converted into monosaccharides (glucose and fructose), which are usable forms for yeast utilization [36]. It is important in fermentation because it is the primary carbon and energy source for microorganisms and serves as fuel for complex microbial and biochemical interactions found in fermentation. As shown in Table 3, initial sucrose concentrations (day 0) for all tea infusions were between 26 g/L and 28 g/L, confirming consistent starting conditions. From day 0 to day 7 (prior to re-feeding), sucrose concentrations decreased across all fermented beverages. Following the addition of 100 g/L sucrose on day 7, sucrose concentrations immediately increased across all tea infusions, then they generally decreased, and by fermentation day 18, the final sucrose concentrations in the kombuchas were 100% BT = 30.3 ± 1.03 g/L, 100% WH = 27.3 ± 6.25 g/L, and 50% BT/WH blend = 30.3 ± 1.12 g/L. The significant decrease in sucrose concentration over time is consistent and aligned with the metabolism of kombucha fermentation reported in the literature [22].

On average, the 100% BT kombucha maintained the highest sucrose levels throughout fermentation, while 100% WH and the 50% BT/WH blend exhibited lower sucrose concentrations. This finding suggests that the distinct phytochemical and nutrient profiles of black tea and white hibiscus may have subtly influenced the overall efficiency of sucrose metabolism by the SCOBY throughout the fermentation [37,38]. For instance, specific compounds present in white hibiscus, such as its higher organic acid content and unique phenolic profile, may have created an environment that, on average, led to slightly more efficient overall sucrose consumption or hydrolysis, resulting in lower average residual sucrose levels compared to black tea.

Initial glucose and fructose concentrations (day 0) were lower in 100% BT kombucha (glucose: 0.74 ± 0.16 g/L; fructose: 0.68 ± 0.37 g/L), the 50% BT/WH blend showed intermediate levels (glucose: 1.07 ± 0.14 g/L; fructose: 1.42 ± 0.10 g/L), and the 100% WH kombucha had the highest initial concentrations (glucose: 2.28 ± 1.03 g/L; fructose: 2.55 ± 1.12 g/L). During the initial fermentation phase (days 0–7), both glucose and fructose concentrations generally increased across all tea infusions. Glucose and fructose concentrations also exhibited dynamic changes post-re-feeding, with distinct accumulation patterns observed based on tea type. In the 100% BT kombucha, glucose and fructose levels remained relatively low, but there was a slight increase from day 8, reaching final concentrations of 3.12 ± 0.25 g/L for glucose and 3.52 ± 0.43 g/L for fructose by day 18. In significant contrast, the 100% WH kombucha displayed a rapid and pronounced accumulation of both sugars; fructose peaked at 8.29 ± 0.47 g/L on day 14 before a slight decline to 7.73 ± 0.43 g/L by day 18; glucose peaked at 6.10 ± 0.72 g/L on day 14, ending at 5.88 ± 0.76 g/L. The 50% BT/WH blend kombucha showed an intermediate pattern for both sugars, with glucose levels stabilizing around 2.96 ± 0.35 g/L and fructose around 3.56 ± 0.45 g/L by day 18.

Glucose concentrations decreased over the fermentation period for all beverages. On average, 100% WH had significantly higher glucose concentrations than both 100% BT and the 50% BT/WH blend at every sampling day, whereas 100% BT and the blend did not differ significantly from each other (Table 2; p < 0.05). Fructose showed a similar pattern: 100% WH consistently exhibited higher fructose concentrations than 100% BT and the blend, while no significant differences were observed between 100% BT and the blend on any day. Across the fermentation period, average fructose levels were highest in 100% WH, intermediate in the 50% BT/WH blend, and lowest in 100% BT. The significant interaction between tea infusion type and fermentation day indicates that the magnitude of these fructose differences changed over time, with particularly large and highly significant differences between 100% WH and the other beverages on later fermentation days (e.g., days 8, 11, 14, and 18). Concentrations decreased over fermentation days for all beverages. The observed differences in residual sugar concentrations confirm that the microorganisms within the SCOBYs utilized sugars at varying rates across tea types. Over the fermentation period, the 50% blend and 100% BT kombucha displayed similar rates of change for fructose and glucose concentrations (~0.21 g/L/day for glucose, and ~0.231 g/L/day for fructose). In comparison, the 100% WH accumulated more than twice these values, with rates of 0.516 g/L/day for glucose and 0.611 g/L/day for fructose over the entire fermentation. The overall elevation in glucose and fructose concentrations across all tea varieties distinctly indicates the hydrolytic conversion of sucrose into its constituent monosaccharides, as supported by the linear reduction in sucrose concentrations presented in Table 3. However, the significantly higher accumulation may suggest its impaired utilization.

Furthermore, across all tea types, glucose was consistently observed to be the preferred substrate for microorganisms compared to fructose. The most pronounced glucose utilization, indicated by the greatest decrease in glucose concentration, occurred in the 100% BT, followed by the blend, and lastly, the 100% WH. This may suggest a preference by Saccharomyces and Acetobacter for glucose, likely due to glucose being the smaller carbohydrate monomer and the primary starting point for alcoholic fermentation [39,40], allowing yeast to immediately begin energy harvesting [41,42]. In addition, yeast cells possess hexose (Hxt) transporters that exhibit a high affinity for glucose, leading to its preferential consumption and, often, the repression of other sugars via the Crabtree effect [36,40,42].

The high concentrations of fructose and glucose observed at the end of day 18 in the 100% WH kombucha may imply incomplete, slow, or sluggish fermentation in this specific tea infusion. While sucrose breakdown was in progress, the elevated residual sugar concentrations found in the 100% WH may imply that the utilization of these simple sugars by microorganisms, including Acetobacter strains and Saccharomyces spp., was slowed [42,43]. Sluggish fermentation is recognized by excessive concentrations of residual sugars at the completion of alcoholic fermentation [44]. It is rarely attributable to a single factor but rather emerges from a combination of various adverse conditions, such as limited nutrient availability (nitrogen, phosphate), enzyme inhibitors, low pH, poor yeast strain tolerance, microbial imbalances, cation imbalances, or high substrate concentrations [44]. In the context of the 100% WH kombucha, the primary drivers of this slow fermentation appear to be the combination of the presence of enzyme inhibitors such as phenolic and flavonoids, which exhibit potent antimicrobial properties [14], and the adverse conditions of low pH and high concentrations of organic acids, particularly acetic acid [43,45]. Our data reported in Table 2 confirm that the 100% WH kombucha consistently maintained the lowest pH and highest acidity throughout the fermentation process.

While yeast can generally thrive in slightly acidic environments, a highly acidic medium creates significant stress conditions that impair their ability to utilize sugar. This results in the accumulation of simple sugars, which, despite being broken down during the hydrolytic process, are not effectively utilized by the yeast [46]. Specifically, at low pH, acetic acid (pKa = 4.75) primarily exists in its undissociated (uncharged) state (XCOOH), which readily diffuses across yeast cell membranes [46,47]. Upon entering the relatively higher pH environment of the cytosol, this undissociated acid dissociates (ionizes) into protons (H+) and acid anions (XCOO−). The subsequent accumulation of these released protons within the cell’s cytosol causes it to become more acidic, thereby lowering the cytosolic pH. This internal acidification can profoundly inhibit critical metabolic functions essential for fermentation [46,47].

Additionally, the buildup of these negatively charged acid anions within the cell generates abnormally high turgor pressure. This leads to severe oxidative stress for the yeast [43], further compromising cellular health and function. Beyond these direct toxic effects, the resulting hypertonic intracellular environment can also impair or even destroy hexose transporters [43]. This impairment significantly slows the utilization of residual sugars and diminishes the overall fermentation capacity of the yeast [42,48]. Yeast cells, specifically Saccharomyces cerevisiae, rely on a large and diverse family of these Hxt proteins embedded in their cell membranes, each exhibiting varying affinities for different sugars, allowing specific ‘matching’ and transport into the cell. If under severe stress, yeast may even destroy its Hxt transporters to prevent the uptake of excessive sugars, which can become toxic if not processed quickly enough [46]. This sequence of events associated with yeast stress culminates in sluggish fermentation, increased cell autolysis, the formation of off-flavors, a decrease in desirable fruity aromas due to the hydrolysis of volatile esters, and ultimately, accelerated aging and premature death of the yeast [42]. Furthermore, extended exposure of yeast to such a hypertonic solution (due to high internal solute concentration) can lead to a decrease in cytosol fluids, impeding the entry of substrates and the exit of products from the cell. In such stressful conditions, yeast may divert its limited carbon resources towards maintaining the activity of its transport systems rather than channeling them into ethanol production [48].

3.2. Sensory Evaluation

3.2.1. Panelist Profile

A total of 97 untrained adult volunteers tasted and evaluated all three kombucha beverages. Recruitment was mainly done within the Virginia Tech community, and most panelists self-identified as female (61.9%), aged between 18 and 24 years old (51.5%), white Caucasian (57.7%), and had completed a bachelor’s degree (41.2%) (Table 3). This demographic profile is consistent with the demographic profile of other consumer studies conducted on hibiscus and kombucha products. For instance, the gender and age distribution observed in our study was comparable to those reported by Sales et al. [49]—61% females, 47% aged 18–24—and Ndiaye et al. [50]—female (73%) and the 18–34 age group (76%). Nevertheless, the highly educated profile of the participants is a recognized limitation of conducting consumer studies on a college campus, which can limit the generalizability of the research findings. Overall, kombucha consumption was not very frequent among participants. Most participants (37.1%) reported that they consume kombucha less than once a month, 26.8% of the participants had never consumed kombucha, and only 6.2% of the participants reported that they consume kombucha daily (Table 1).

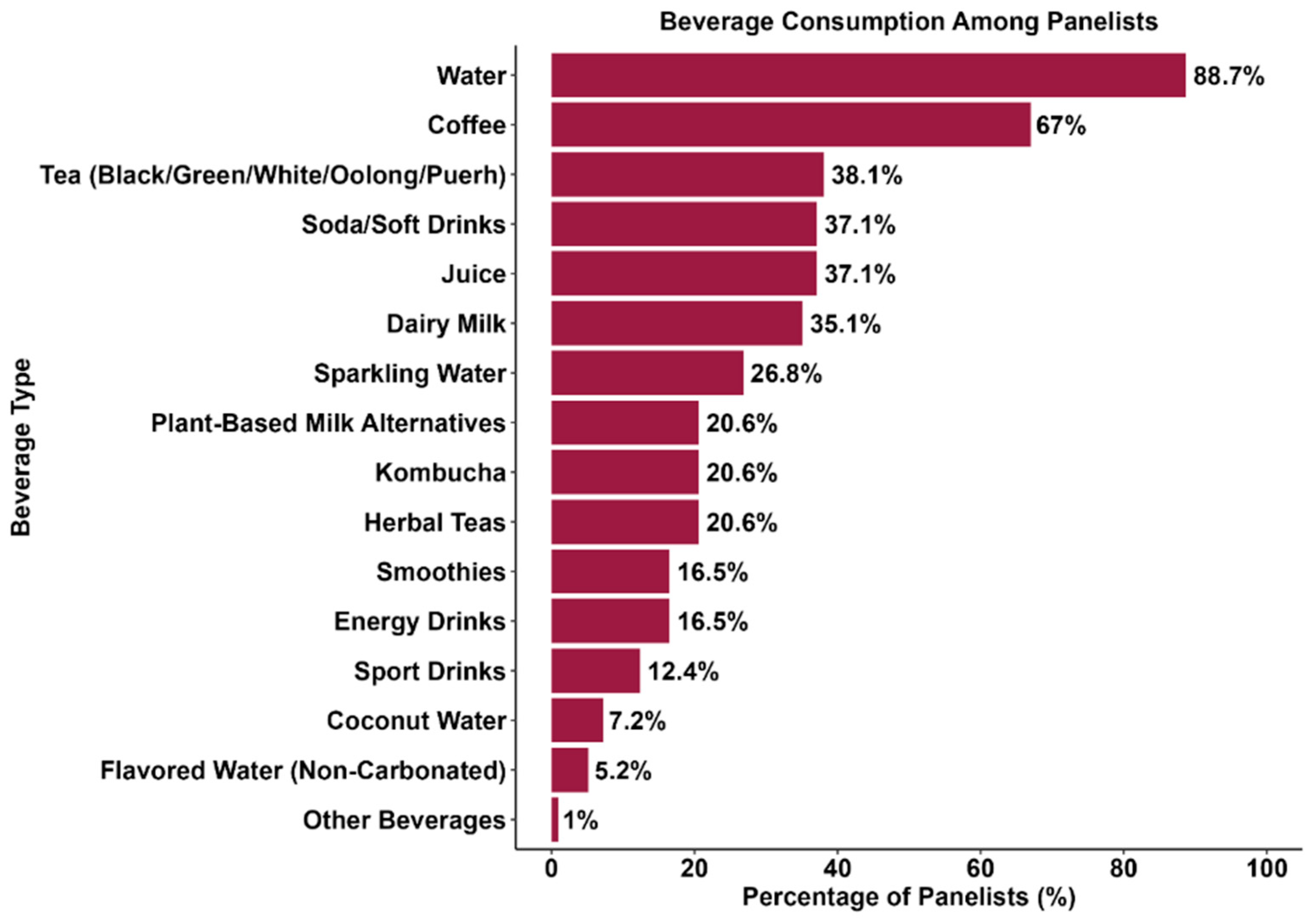

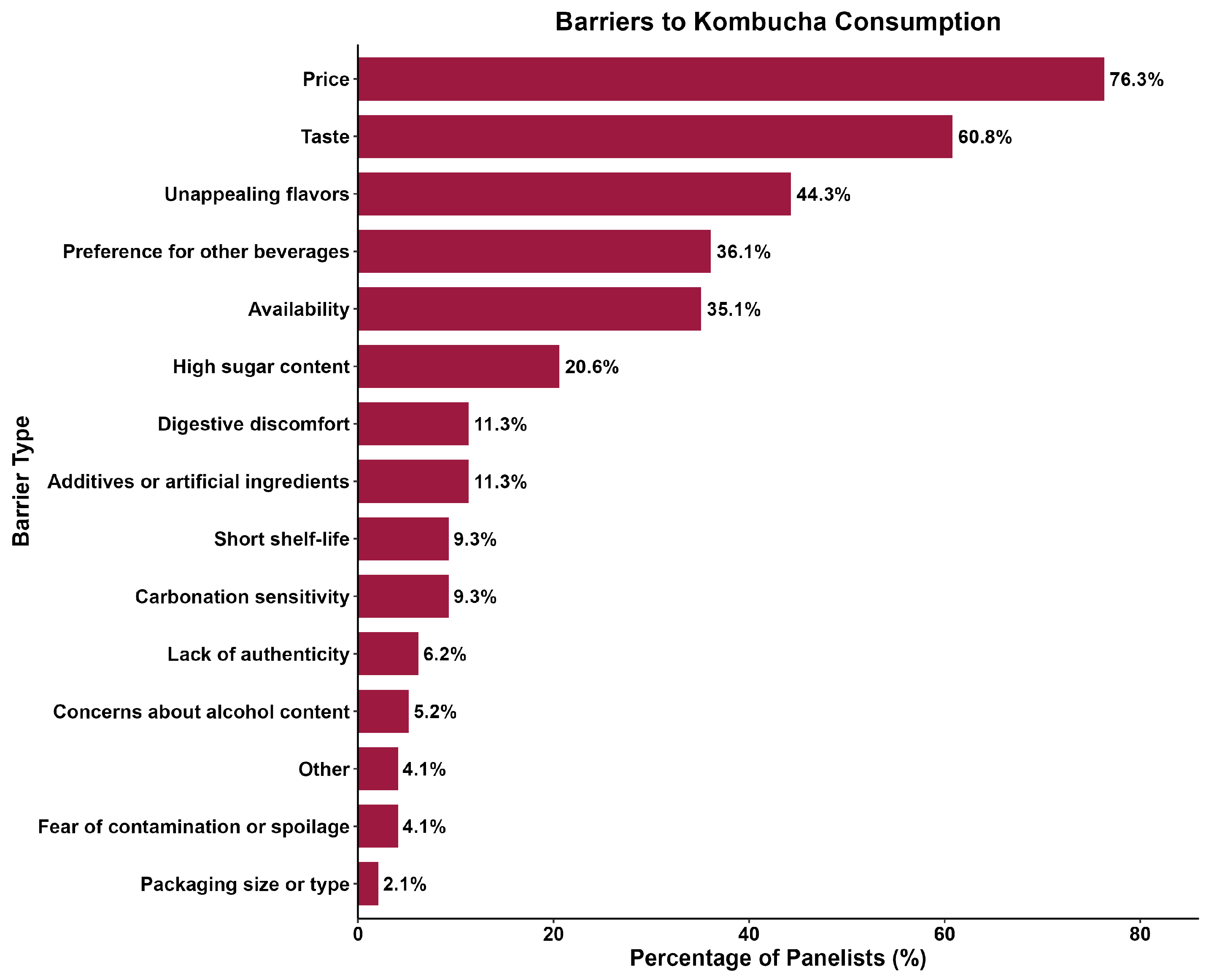

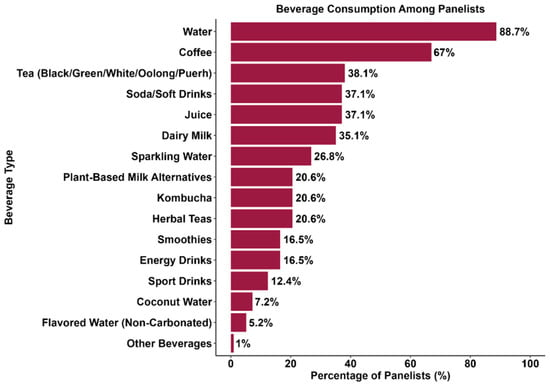

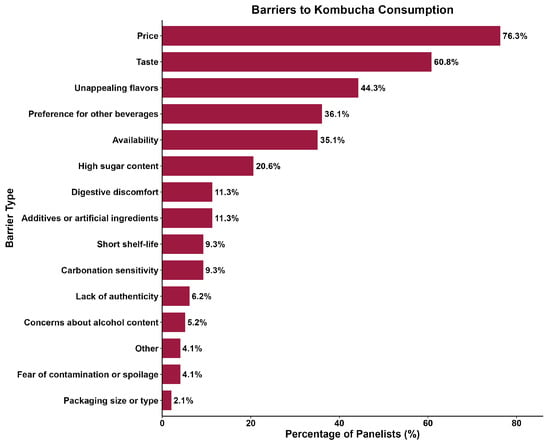

Participants were asked to select up to five non-alcoholic beverages they consume more frequently. Water and coffee were the most chosen options, respectively, followed by tea, juice, and soda/soft drinks (Figure 1). In contrast, Sales et al. [49] reported soda (73%), sparkling water (50%), and sparkling wine (42%) as the top three nonalcoholic beverages consumed by their panelists. Furthermore, only 20.6% of the panelists selected kombucha as one of their most consumed non-alcoholic beverages. When asked which factors might prevent them from purchasing kombucha more frequently, most participants answered price and taste (Figure 2). In comparison, Ndiaye et al. [50] reported aroma (34.8%), taste (25.9%), and health benefits (20.7%) as the top three reasons participants would consume hibiscus kombucha.

Figure 1.

Most frequently consumed non-alcoholic beverages (N = 97).

Figure 2.

Barriers to purchasing kombucha more frequently (N = 97).

3.2.2. Hedonic Testing and Willingness to Pay

Average hedonic scores for the three kombucha beverages (100% BT, 100% WH, and 50% blend) are reported in Table 4. The three kombuchas were significantly different in overall liking, color, flavor, and mouthfeel liking (p < 0.05). Differences observed in aroma liking were not statistically significant (p > 0.05).

Table 4.

Hedonic sensory evaluation of kombuchas.

The 100% BT kombucha was preferred overall (6.48 ± 1.54), and no significant difference in overall liking was found between the 50% BT/WH blend (5.37 ± 1.95) and the 100% WH kombuchas (5.22 ± 2.04). In comparison, other studies have reported varying overall mean acceptance scores for kombucha on a 9-point hedonic scale. Chaluvadi et al. [51] reported an overall mean acceptance of 5.3 ± 1.2 for black tea kombucha. On the other hand, Sutthiphatkul et al. [19] reported an overall liking score of 4.93 ± 1.26 for their 100% black tea kombucha and 5.33 ± 1.79 for a blend (50% red hibiscus, 50% black tea) kombucha. Interestingly, Sutthiphatkul et al. [19] also reported a higher acceptance of 6.93 ± 1.34 for their 80% black tea–20% red roselle blend kombucha.

Additionally, it is relevant to note that consumers’ familiarity with a product may influence their perception and judgment of product quality [52,53,54]. Consumer familiarity with a product, as determined by knowledge and exposure to it, has been linked to a higher liking score, a higher desire to purchase, and higher product expectations [53]. Consumers’ exposure to a product has also been linked to the frequency of consumption, which is associated with a frame of reference that provides background information and comparison points, which product assessors use to evaluate the product’s quality mentally [53,54]. As shown in Table 3, kombucha consumption among our sensory panelists was somewhat low; thus, low familiarity with the product may justify liking scores between indifference and the lower acceptance range, just slightly above the indifference score (5 = neither like nor dislike). Convenience sampling was a limitation of our study, and future research should consider the recruitment of frequent kombucha consumers.

Color is an important sensory property that influences consumers’ product acceptance and purchase intent. The color of the kombucha beverage originates from the tea pigment during steeping and infusion, as well as the changes that occur as fermentation progresses. Black tea kombucha exhibits a pale gold to deep amber color, attributed to the presence of theaflavins and thearubigins [55,56]. On the other hand, the pale yellowish lemonade color of white hibiscus kombucha is primarily associated with anthoxanthins, which are soluble pigments that vary from white to creamy yellow [57]. Participants had a significant preference for the color of the 100% BT kombucha (6.62 ± 1.56), and no significant difference was found between the color liking of the blend (6.25 ± 1.44) and the 100% WH (5.86 ± 1.77) kombuchas. The higher mean color liking score of the 100% BT kombucha indicates that panelists preferred the appearance of this sample relative to the others (Table 4). Visual appearance cues, such as color, are known to set expectations regarding the likely taste and properties of a beverage [58]. Because no instrumental color measurements or formal sensory evaluation of color were conducted, any link between this preference and the golden-amber hue typically reported for black tea kombucha should be regarded as speculative rather than demonstrated by the present data. The familiarity of panelists with the appearance of black tea beverages may also have contributed to this preference [59]. Panelists may have a preconceived notion of black tea and may lean towards the pure black tea kombucha formulation over the pure white hibiscus formulation or the blend.

The aroma of kombucha, as a fermented beverage, is derived from the tea substrates and the volatile aromatic compounds produced by the metabolic activities of the microorganisms [32]. Kombucha has a complex aroma profile composed of various volatile organic compounds, including esters, alcohols, aldehydes, and organic acids [23]. Typically, the dominant organic acid is acetic acid, produced by yeast and AAB during the fermentation process [23,60]. Acetic acid is characterized by a sour, pungent, acidic, and vinegar-like smell that is sharp and harsh and may be undesirable to consumers in excessive quantities. As shown in Table 4, any subtle aromatic contributions from the distinct tea infusions did not translate into a statistically significant difference in aroma liking (p > 0.05).

Conversely, flavor liking showed a different trend, and average flavor liking scores of the three kombuchas were statistically significantly different (p < 0.05). As shown in Table 4, the 100% BT kombucha had higher flavor liking (6.56 ± 1.70) compared to the other two kombuchas, the blend (5.32 ± 2.09) and 100% WH (5.25 ± 2.10). No significant difference was found between the flavor liking of the blend kombucha and the 100% WH kombucha (p > 0.05). The higher flavor liking observed for the 100% BT kombucha may be linked to the higher pH (3.01 ± 0.06) and lower total titratable acidity (6.52 ± 0.12) (Table 2). It has been well established that pH and acidity have an inverse relationship [23]. A higher acidity and low pH increase the perception of sourness, astringency, and acidity in kombucha, which are considered negative drivers and are found undesirable by consumers, thereby reducing the drinkability of the kombucha beverage [23]. Typically, the recommended optimum pH level for consuming kombucha to achieve a desirable balance of sweetness and tartness is between pH 3.0 and 3.5 (Kombucha—Food Source Information, The Quick Guide to Kombucha pH and Acidity|Brew Buch). The pH of 100% BT at the end of the fermentation process was 3.01 ± 0.06, which falls within the ideal range for a better sensory experience. This pH contrasts with the pH of the 100% WH (2.64 ± 0.01) and the 50% BT/WH blend (2.80 ± 0.04), which fall below the ideal range for a better sensory experience.

As shown in Table 4, the overall preference for kombucha made from 100% BT among panelists was statistically higher and may be linked to chemical parameters, such as pH and total titratable acidity. These two parameters influence how consumers perceive tartness and sourness, which are key attributes of fermented beverages [60,61,62]. Table 2 shows an inverse relationship across all the samples. The 100% BT kombucha consistently exhibited higher pH levels and lower organic acid production throughout the fermentation days compared to the other samples. On the other hand, white hibiscus is inherently rich in organic acids, which contribute to its intrinsic tart taste and tendency to have a lower pH. As fermentation progressed, the pH level in these samples decreased, and total acidity increased. This inverse relationship may suggest elevated perception of tartness, sourness, acidity, and vinegar notes among consumers, which they found unappealing or less preferred. This finding reflects the 100% BT kombucha’s lower accumulation of organic acid, resulting in less tartness and sourness compared to other samples. As presented in Figure 2, our panelists listed taste and unappealing flavors as major barriers to consuming kombucha more frequently.

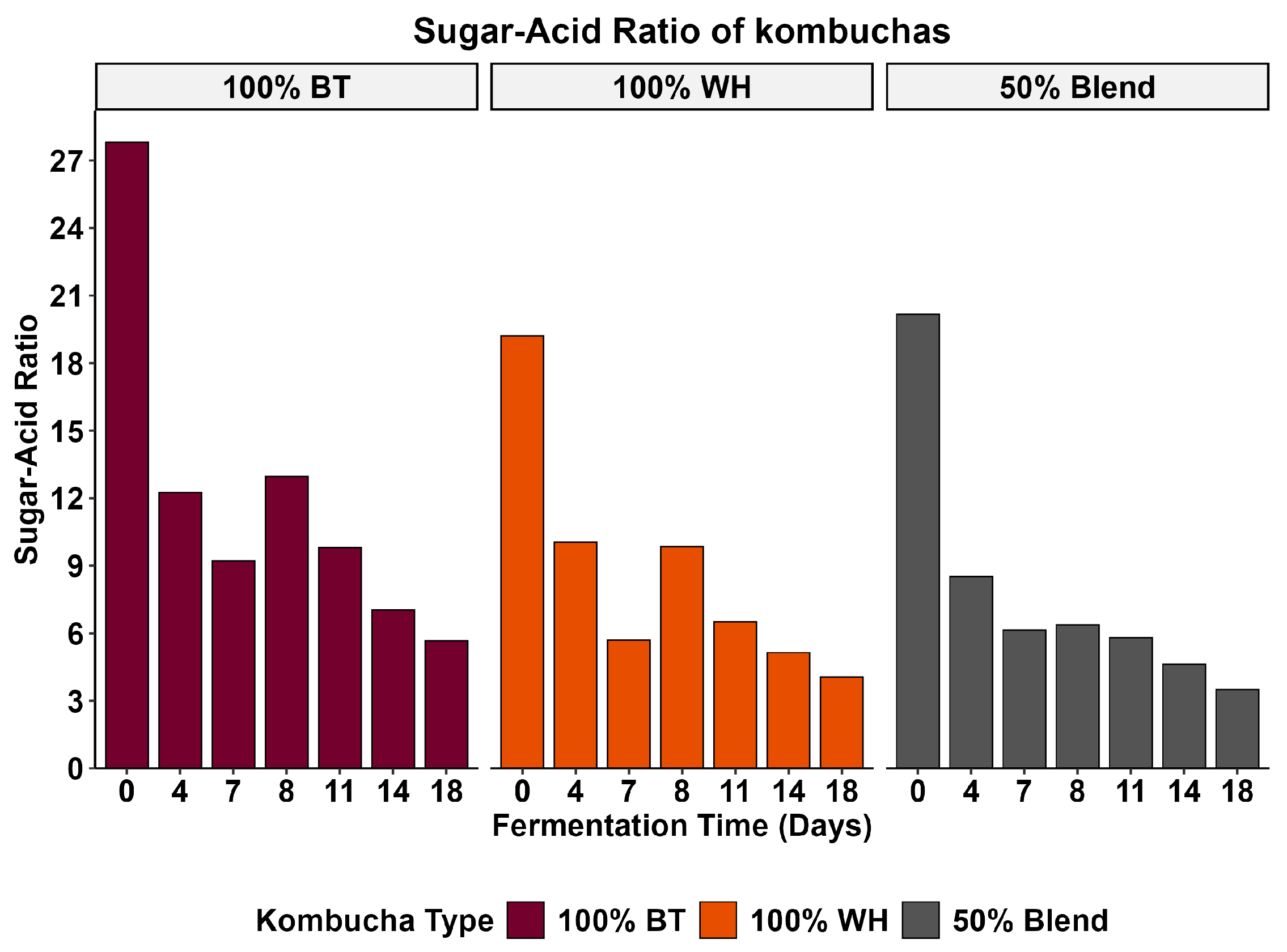

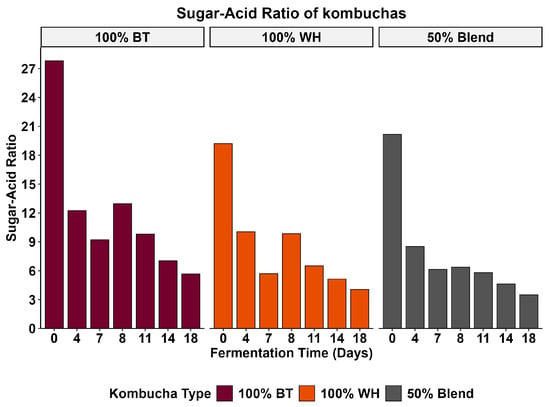

The sugar-acid ratio is an important parameter in beverages that influences the overall taste perception of the beverage [63,64]. It is the balance between the sweetness derived from sugars and the sourness contributed by the organic acid in the beverage [63]. This ratio is defined by the concentration of total sugar relative to the total organic acid produced during the fermentation process [64]. As shown in Figure 3, although our 100% WH kombucha had the highest residual sugar content and the highest total titratable acidity, it was not the most preferred beverage. The low preference for the 100% WH kombucha may be linked to a suppressive effect of acidity on sweetness, microbial stress-induced off-flavor formation, or the contribution of non-tastant flavor compounds. The higher residual sugars observed in the 100% WH suggest impaired fermentation due to adverse conditions (high pH and acidity), which may have created adverse conditions for the yeast to thrive, thereby impairing their metabolism and function [44,46]. These types of adverse conditions may also have led to increased cell autolysis and the formation of off-flavors and a decrease in fruity aroma due to the hydrolysis of volatile esters [42]. Mouthfeel refers to the physical and tactile sensations experienced in the mouth. The average mouthfeel liking of the three kombuchas was significantly different (p < 0.05). Post hoc analysis revealed that mouthfeel liking was significantly different between the 100% WH and the 100% BT kombuchas (p < 0.05). In contrast, no statistically significant differences were found between the blend and the other two kombuchas (p > 0.05). This finding suggests that while an overall difference in mouthfeel liking was detected, the primary driver was the distinction between the 100% WH and 100% BT formulations. The mouthfeel perception of the blend was similar to that of the individual tea formulations, although not significantly different from either. As shown in Table 4, the 100% BT kombucha had the highest mean mouthfeel liking score (6.40 ± 1.52), followed by the blend (5.96 ± 1.87) and 100% WH (5.72 ± 1.78).

Figure 3.

Sugar-acid ratios of kombuchas.

In our study, participants were asked to use a linear scale (range = USD 0.00–USD 4.00) to indicate their willingness to pay for 16 fl oz (473 mL) of each kombucha sample tasted, which is a typical volume for kombucha bottles sold in the United States. The average WTP amount was significantly different among kombucha samples (p < 0.05). Participants were willing to pay significantly more for the 100% BT kombucha (USD 2.45 ± USD 1.09), but no significant difference was observed between WTP values for 100% WH (USD 1.85 ± USD 1.22) and the 50% BT/WH blend (USD 1.84 ± USD 1.25). Willingness to pay (WTP) is a measure of the maximum price a consumer is willing to pay for a given quantity of a product [65]. Research shows that WTP is linked to consumers’ overall acceptance of the product [66]. In our study, participants were willing to pay more for the kombucha they liked more overall, which was the 100% BT kombucha.

WTP is used by market researchers to assess consumers’ perceived value of a product in monetary terms. In a preliminary survey study conducted in the U.S., Ndiaye et al. [50] reported WTP for three hibiscus-based non-alcoholic beverages: ready-made tea, bottled juice, and kombucha. WTP for hibiscus-based kombucha before and after their survey participants received additional information about the health benefits of hibiscus were USD 3.23 and USD 2.84, respectively. Both these WTP amounts are higher than the average WTP amounts we observed for our hibiscus kombuchas. The lower WTP observed in our study may be related to the demographic profile of our participants, who were mostly university students, or the fact that the participants of the study conducted by Ndiaye et al. [50] did not taste any sample.

3.2.3. Correspondence Analysis and Penalty Lift Analysis

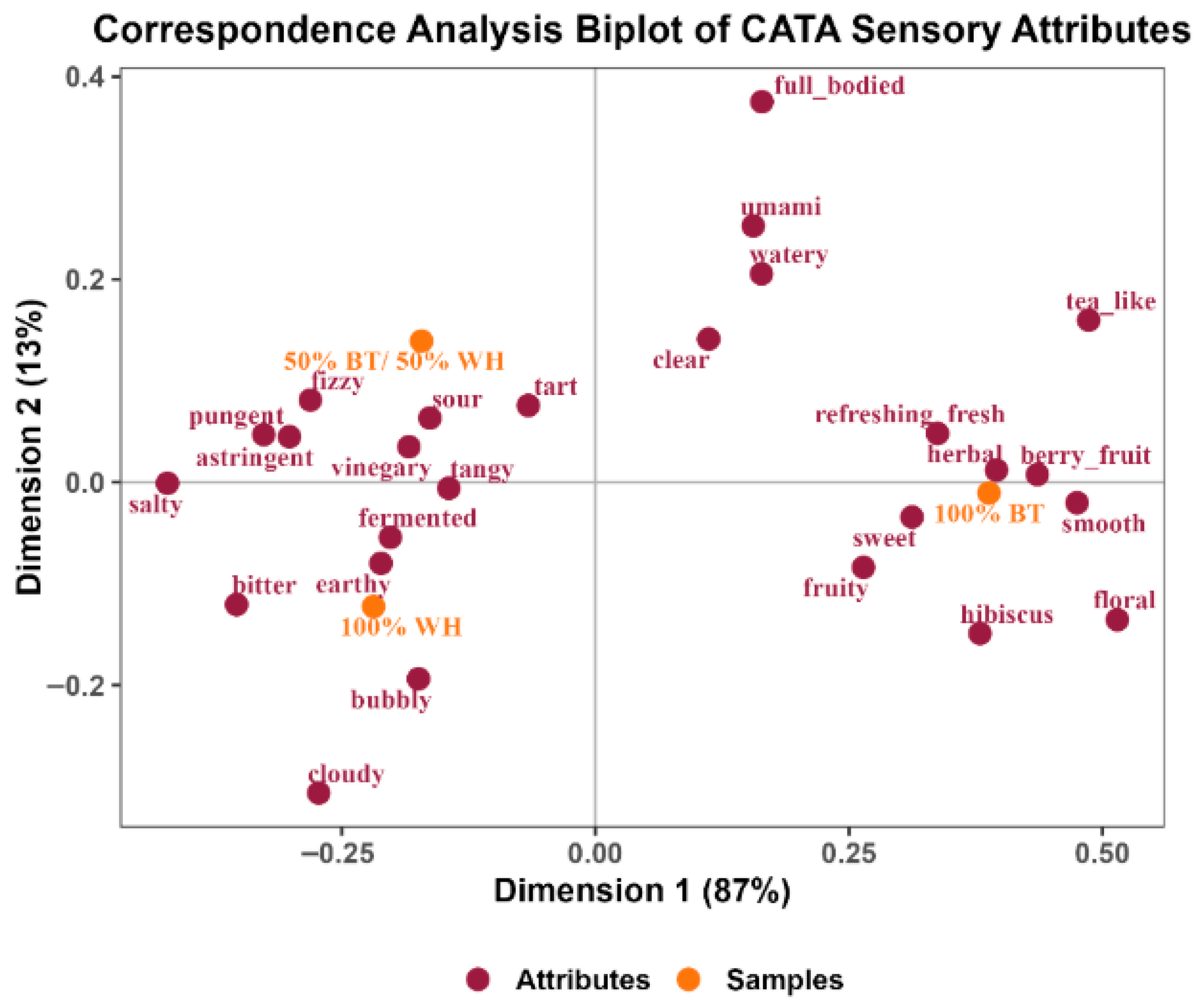

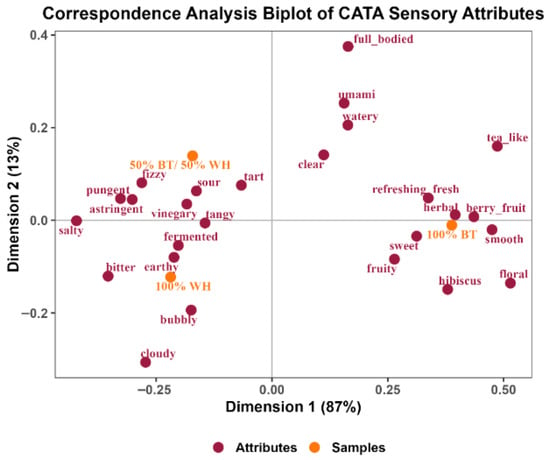

Correspondence analysis (CA) is an analytic tool that shows the association between the product or sample being evaluated and the descriptors or attributes used to describe them [67]. The CA plot (Figure 4) shows a close relationship between the sensory attributes of the 50% BT/WH blend and the 100% WH kombucha. The maroon and red dots represent the sensory attributes, and the orange dots represent the kombucha samples. Attributes close to each other are strongly associated.

Figure 4.

Correspondence analysis plot of kombucha sensory attributes.

The variability of the data was explained by dimensions 1 and 2 (87% and 13%, respectively). Dimension 1 explained the major differences captured through the CATA data among the samples based on attribute associations. As shown in Figure 4, the 100% WH and the 50% BT/WH blend kombuchas were closely related and significantly different from the 100% BT kombucha. The kombuchas made with white hibiscus were mostly associated with the following sensory attributes: bubbly, bitter, earthy, vinegar-like, fermented, salty, tart, sour, astringent, pungent, tangy, and fizzy.

The sour, tart, fermented, tangy, astringent, pungent, bitter, and vinegary attributes may be linked to the low pH and high acidity profile of 100% WH and the 50% BT/WH blend (Table 1). These sensory attributes are primarily due to the organic acids produced and the low pH observed during the fermentation process. Fizziness and bubbling are key qualities of carbonation for mouthfeel, and these sensory characteristics have been reported as positive drivers of kombucha liking [32]. Fizziness and bubble formation are a function of the CO2 generated as a byproduct of yeast fermentation of sugars [68]. Typically, they are produced during the secondary fermentation phase, where yeast metabolizes residual sugars in an airtight container. This process generates CO2, which accumulates in yeast cells in the form of bubbles [69]. Subsequently, the CO2 is trapped, leading to a buildup of pressure, resulting in increased fizziness [68]. Fizziness is associated with the tingling sensation that occurs when a carbonated beverage is consumed. “Bubbly” refers to the appearance of bubbles rising to the surface of a liquid and the sound they produce. The 50% BT/WH blend was the fizziest kombucha, while the 100% WH was the bubbliest. This may suggest more yeast metabolism of the residual sugars during the secondary fermentation process in 100% WH. It is relevant to note that increased carbonation can enhance the perception of sourness [60], which aligns with the observed higher acidity in these samples (Table 1). Moreover, excessively elevated CO2 levels can lead to an intensely harsh or sharp mouthfeel, potentially reducing overall acceptance. Additionally, the attribute “cloudy”, which was mostly associated with the 100% WH kombucha, may be attributed to the suspension of yeast cells during active fermentation, leading to increased turbidity.

The 100% BT kombucha was mostly associated with the following sensory attributes: tea-like, refreshing, berry fruit, herbal, fruity, sweet, floral, hibiscus, full-bodied, umami, and clear. The attributes associated with this kombucha were predominantly the milder or more acceptable sensory properties found in traditional kombucha made from black tea. The strong association with smooth, sweet, and floral may suggest its less acidic taste.

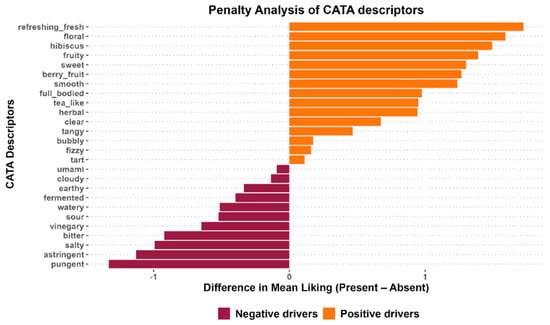

Penalty lift analysis is an analytical tool used by product developers to improve a product based on consumers’ perceptions of the product’s attributes [70]. In the development of new products, it is essential to understand which attributes contribute to a product’s likability or unlikability. Typically, penalty lift analysis is employed in conjunction with CATA and hedonic liking data to identify the attributes that contribute to the consumer’s liking or disliking of the product [71]. As an essential analytical tool, penalty lift analysis can support product developers in understanding the differences in the sensory characteristics of a product, which can guide process optimization, identify new consumer segments, and assess product suitability [71,72].

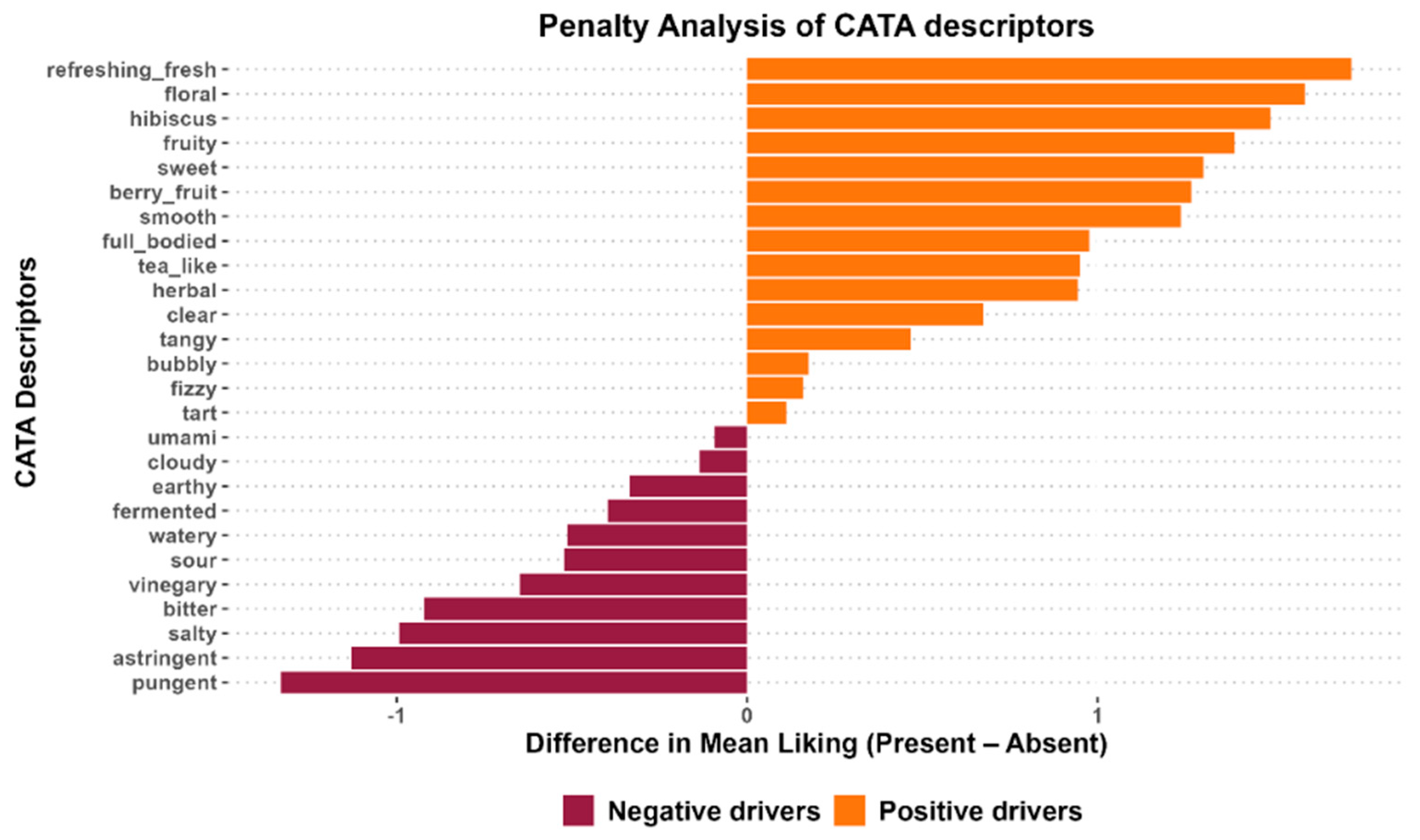

A penalty lift analysis was performed to further analyze how the overall liking of the kombuchas was affected by their sensory characteristics. Figure 5 shows the penalty lift analysis plot of CATA attributes in the kombuchas. The Y-axis represents the CATA attributes. The X-axis represents the difference in the mean liking when the attribute is present. The right horizontal orange bars indicate attributes associated with higher mean liking scores when selected by consumers (positive drivers), while attributes on the left horizontal maroon bar decreased the overall mean liking score when checked by consumers (negative drivers). The length of the horizontal bars indicates the extent of the attributes. For example, “refreshing” had the highest positive impact on the acceptability of the kombucha samples, while “pungent” had the highest negative impact.

Figure 5.

Penalty lift analysis of CATA attributes in kombucha.

To increase consumer acceptability of kombuchas containing white hibiscus, it is recommended that these positive drivers be prioritized in new formulations. To enhance these sensory characteristics, strategies such as optimizing fermentation conditions can be incorporated to slow down organic acid production. Excessive production of organic acid is associated with the bitter, astringent, pungent, and vinegary taste reported by panelists. Higher rates of these negative drivers can suppress desirable attributes, such as sweetness [73,74]. To enhance the positive drivers and reduce the negative drivers, it is recommended that fermentation parameters, such as time and temperature, be adjusted [73]. Furthermore, adding sweet, fruity-related flavors from fruits (such as strawberry, apple, cinnamon, orange, pineapple, guava, pomegranate, and watermelon) during secondary fermentation can enhance the sensory properties of kombucha [3,75]. Another point to note is that the tea substrate also has an impact on sensory drivers. White hibiscus is reported to have high organic acid content, which contributes to its highly acidic taste [14] and a soft, floral aroma derived from its volatile aromatic compounds. Though the highly acidic taste was detected by panelists, as reflected in the attributes they selected, the floral attribute was likely masked by excessive acid production, which increased the intensity of sourness.

4. Conclusions

The kombuchas differed in their physicochemical and sensory properties. pH decreased across all tea types, while total titratable acidity increased across tea types and fermentation days. Glucose, fructose, and sucrose concentrations varied across all tea types throughout the fermentation period. Conversely, tea type and fermentation time had significant effects on alcohol content. Black tea kombucha was rated highest in both sensory acceptance and willingness to pay. On the other hand, white hibiscus kombucha was rated lowest in sensory acceptance and willingness to pay. Black tea kombucha was associated with sensory descriptors like “refreshing”, “floral”, “hibiscus”, “fruity”, and “sweet”—the top five descriptors that increased its overall liking. In contrast, blend kombucha and white hibiscus kombucha were associated with sensory descriptors like “pungent”, “astringent”, “salty”, “bitter”, and “vinegary”—the five main descriptors that decreased overall liking. To increase the acceptability of white hibiscus kombucha or blends, product developers should consider exploring lower percentages of white hibiscus as an ingredient in kombucha or adding white hibiscus as a flavoring ingredient during secondary fermentation.

Limitations of Work and Future Research

The convenience sampling approach and the highly educated profile of the participants were acknowledged as limitations of the sensory evaluation study, which narrowed the conclusions. The low amount of blend formulations was another limitation of this study, and the evaluation of more blends is encouraged in future work. This consumer-driven product development work would benefit from a sequential study on the stability of the hibiscus kombucha beverages at refrigeration temperature. Moreover, the impact of white hibiscus on the microbial community dynamics throughout the fermentation of the kombuchas was not evaluated in this preliminary study, and future research is recommended.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.A. and S.O.; methodology, E.A., R.C., K.H., A.S., and S.O.; formal analysis, E.A., K.H., and A.S.; writing—original draft preparation, E.A.; writing—review and editing, R.C., K.H., A.S., and S.O.; visualization, E.A.; supervision, R.C. and S.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Virginia Tech (protocol code: 24-1089; date of approval: 23 January 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article are available from the authors upon request.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the volunteers who assisted with the sensory panels, as well as the sensory participants who evaluated our samples. The authors also thank the Virginia Tech Department of Food Science and Technology for providing financial support for this research. The authors used ChatGPT (version 4) for the purposes of improving the R codes for data analysis. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AAB | Acetic acid bacteria |

| ANOVA | Analysis of variance |

| BT | Black tea |

| CA | Correspondence analysis |

| CATA | Check-all-that-apply |

| FID | Flame ionization detection |

| HSD | Honestly Significant Difference |

| RR | Response ratio |

| SCOBY | Symbiotic culture of bacteria and yeast |

| TTA | Total titratable acidity |

| WH | White hibiscus |

| WTP | Willingness-to-pay |

References

- Giri, N.A.; Sakhale, B.K.; Nirmal, N.P. Functional Beverages: An Emerging Trend in Beverage World. In Recent Frontiers of Phytochemicals; Academic Press: London, UK, 2023; pp. 123–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, V.C.; Botelho, V.A.; Chisté, R.C. Alternative Substrates for the Development of Fermented Beverages Analogous to Kombucha: An Integrative Review. Foods 2024, 13, 1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czarnowska-Kujawska, M.; Klepacka, J.; Starowicz, M.; Lesińska, P. Functional Properties and Sensory Quality of Kombucha Analogs Based on Herbal Infusions. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dartora, B.; Crepalde, L.T.; Hickert, L.R.; Fabricio, M.F.; Ayub, M.A.Z.; Veras, F.F.; Brandelli, A.; Perez, K.J.; Sant’Anna, V. Kombuchas from Black Tea, Green Tea, and Yerba-Mate Decocts: Perceived Sensory Map, Emotions, and Physicochemical Parameters. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2023, 33, 100789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alderson, H.; Liu, C.; Mehta, A.; Gala, H.S.; Mazive, N.R.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, S.; Serventi, L. Sensory Profile of Kombucha Brewed with New Zealand Ingredients by Focus Group and Word Clouds. Fermentation 2021, 7, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahiduzzaman, M.; Jamini, T.S.; Islam, A.K.M.A. Roselle (Hibiscus sabdariffa L.): Processing for Value Addition. In Roselle; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021; pp. 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamini, T.S.; Islam, A.K.M.A. Roselle (Hibiscus sabdariffa L.): Nutraceutical and Pharmaceutical Significance. In Roselle; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021; pp. 103–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harmili, H.; Fadlilah, S.; Sucipto, A. Effectiveness of Hibiscus sabdariffa on Blood Pressure of Hypertension Patients. J. Keperawatan Respati Yogyak. 2021, 8, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilyas, R.A.; Sapuan, S.M.; Kirubaanand, W.; Zahfiq, Z.M.; Atikah, M.S.N.; Ibrahim, R.; Radzi, A.M.; Nadlene, R.; Asyraf, M.R.M.; Hazrol, M.D.; et al. Roselle: Production, Product Development, and Composites. In Roselle; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021; pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelmonem, M.; Ebada, M.A.; Diab, S.; Ahmed, M.M.; Zaazouee, M.S.; Essa, T.M.; ElBaz, Z.S.; Ghaith, H.S.; Abdella, W.S.; Ebada, M.; et al. Efficacy of Hibiscus sabdariffa on Reducing Blood Pressure in Patients With Mild-to-Moderate Hypertension: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Published Randomized Controlled Trials. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 2022, 79, e64–e74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izquierdo-Vega, J.; Arteaga-Badillo, D.; Sánchez-Gutiérrez, M.; Morales-González, J.; Vargas-Mendoza, N.; Gómez-Aldapa, C.; Castro-Rosas, J.; Delgado-Olivares, L.; Madrigal-Bujaidar, E.; Madrigal-Santillán, E. Organic Acids from Roselle (Hibiscus sabdariffa L.)—A Brief Review of Its Pharmacological Effects. Biomedicines 2020, 8, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morales-Luna, E.; Pérez-Ramírez, I.F.; Salgado, L.M.; Castaño-Tostado, E.; Gómez-Aldapa, C.A.; Reynoso-Camacho, R. The Main Beneficial Effect of Roselle (Hibiscus sabdariffa) on Obesity Is Not Only Related to Its Anthocyanin Content. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2019, 99, 596–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salinas-Moreno, Y.; Arteaga-Garibay, R.; Arroyo-Silva, A.; Ordaz-Ortiz, J.J.; Ruvalcaba-Gómez, J.M.; Gálvez-Marroquín, L.A. Antimicrobial Activity and Phenolic Composition of Varieties of Hibiscus sabdariffa L. with Red and White Calyces. CyTA J. Food 2023, 21, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yagi, S.; Uba, A.I.; Sinan, K.I.; Piatti, D.; Sagratini, G.; Caprioli, G.; Eltigani, S.M.; Lazarova, I.; Zengin, G. Comparative Study on the Chemical Profile, Antioxidant Activity, and Enzyme Inhibition Capacity of Red and White Hibiscus sabdariffa Variety Calyces. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 42511–42521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangel-García, C.A.; Reynoso-Camacho, R.; Pérez-Ramírez, I.F.; Morales-Luna, E.; De Los Ríos, E.A.; Salgado, L.M. Serum Phospholipids Are Potential Therapeutic Targets of Aqueous Extracts of Roselle (Hibiscus sabdariffa) against Obesity and Insulin Resistance. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 16538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanou, A.; Konate, K.; Dakuyo, R.; Kabore, K.; Sama, H.; Dicko, M.H. Hibiscus sabdariffa: Genetic Variability, Seasonality and Their Impact on Nutritional and Antioxidant Properties. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0261924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bello, M.I.; Dickson, M. Comparative Proximate and Mineral Element Composition in Three Varieties of Calyces of Hibiscus sabdariffa Linn. Direct Res. J. Health Pharmacol. 2020, 8, 27–31. [Google Scholar]

- Maulida, I.D.; Al Marsam, M.R.; Purnama, I.; Mutamima, A. A Novel Beverage with Functional Potential Incorporating Cascara (Coffea arabica), Roselle (Hibiscus sabdariffa), and Red Ginger (Zingiber officinale Rosc. Var. rubrum) Extracts: Chemical Properties and Sensory Evaluation. Discov. Food 2024, 4, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutthiphatkul, T.; Mangmool, S.; Rungjindamai, N.; Ochaikul, D. Characteristics and Antioxidant Activities of Kombucha from Black Tea and Roselle by a Mixed Starter Culture. Curr. Appl. Sci. Technol. 2022, 23, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Van Mullem, J.; Dias, D.R.; Schwan, R.F. The Chemistry and Sensory Characteristics of New Herbal Tea-based Komb Uchas. J. Food Sci. 2021, 86, 740–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Latimer, G.W. (Ed.) Official Methods of Analysis: 22nd Edition (2023). In Official Methods of Analysis of AOAC International; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Villarreal-Soto, S.A.; Beaufort, S.; Bouajila, J.; Souchard, J.; Taillandier, P. Understanding Kombucha Tea Fermentation: A Review. J. Food Sci. 2018, 83, 580–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laureys, D.; Britton, S.J.; De Clippeleer, J. Kombucha Tea Fermentation: A Review. J. Am. Soc. Brew. Chem. 2020, 78, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neffe-Skocińska, K.; Sionek, B.; Ścibisz, I.; Kołożyn-Krajewska, D. Acid Contents and the Effect of Fermentation Condition of Kombucha Tea Beverages on Physicochemical, Microbiological and Sensory Properties. CyTA J. Food 2017, 15, 601–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Miranda, J.F.; Ruiz, L.F.; Silva, C.B.; Uekane, T.M.; Silva, K.A.; Gonzalez, A.G.M.; Fernandes, F.F.; Lima, A.R. Kombucha: A Review of Substrates, Regulations, Composition, and Biological Properties. J. Food Sci. 2022, 87, 503–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moccia, T.; Antuña, C.; Bruzone, C.; Burini, J.A.; Libkind, D.; Alvarez, L.P. First Characterization of Kombucha Beverages Brewed in Argentina: Flavors, Off-Flavors, and Chemical Profiles. Int. J. Food Sci. 2024, 2024, 8677090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakubczyk, K.; Łopusiewicz, Ł.; Kika, J.; Janda-Milczarek, K.; Skonieczna-Żydecka, K. Fermented Tea as a Food with Functional Value—Its Microbiological Profile, Antioxidant Potential and Phytochemical Composition. Foods 2023, 13, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spedding, G. So What Is Kombucha? An Alcoholic or a Non-Alcoholic Beverage? A Brief Selected Literature Review and Personal Reflection; Brewing and Distilling Analytical Services: Lexington, KY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Sadler, G.D.; Murphy, P.A. pH and Titratable Acidity. In Food Analysis; Nielsen, S.S., Ed.; Food Science Texts Series; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2010; pp. 219–238. [Google Scholar]

- Jayabalan, R.; Marimuthu, S.; Swaminathan, K. Changes in Content of Organic Acids and Tea Polyphenols during Kombucha Tea Fermentation. Food Chem. 2007, 102, 392–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suliman, A.M.A.; Ali, A.O.; Idriss, S.E.A.A.; Abdualrahm, M.A.Y. A Comparative Study on Red and White Karkade (Hibiscus sabdariffa L.) Calyces, Extracts and Their Products. Pak. J. Nutr. 2011, 10, 680–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, T.; Grandvalet, C.; Verdier, F.; Martin, A.; Alexandre, H.; Tourdot-Maréchal, R. Microbiological and Technological Parameters Impacting the Chemical Composition and Sensory Quality of Kombucha. Comp. Rev. Food Sci. Food Safe 2020, 19, 2050–2070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakravorty, S.; Bhattacharya, S.; Chatzinotas, A.; Chakraborty, W.; Bhattacharya, D.; Gachhui, R. Kombucha Tea Fermentation: Microbial and Biochemical Dynamics. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2016, 220, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muzaifa, M.; Rohaya, S.; Nilda, C.; Harahap, K.R. Kombucha Fermentation from Cascara with Addition of Red Dragon Fruit (Hylocereus polyrhizus): Analysis of Alcohol Content and Total Soluble Solid. In International Conference on Tropical Agrifood, Feed and Fuel (ICTAFF 2021); Atlantis Press: Samarinda, Indonesia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Sievers, M.; Lanini, C.; Weber, A.; Schuler-Schmid, U.; Teuber, M. Microbiology and Fermentation Balance in a Kombucha Beverage Obtained from a Tea Fungus Fermentation. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 1995, 18, 590–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, W.L.; Raghavendran, V.; Stambuk, B.U.; Gombert, A.K. Sucrose and Saccharomyces cerevisiae: A Relationship Most Sweet. FEMS Yeast Res. 2016, 16, fov107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreeramulu, G.; Zhu, Y.; Knol, W. Kombucha Fermentation and Its Antimicrobial Activity. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2000, 48, 2589–2594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teoh, A.L.; Heard, G.; Cox, J. Yeast Ecology of Kombucha Fermentation. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2004, 95, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayikci, Ö.; Nielsen, J. Glucose Repression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEMS Yeast Res. 2015, 15, fov068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amore, T.; Russell, I.; Stewart, G.G. Sugar Utilization by Yeast during Fermentation. J. Ind. Microbiol. 1989, 4, 315–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallel, L.; Desseaux, V.; Hamdi, M.; Stocker, P.; Ajandouz, E.H. Insights into the Fermentation Biochemistry of Kombucha Teas and Potential Impacts of Kombucha Drinking on Starch Digestion. Food Res. Int. 2012, 49, 226–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verstrepen, K.J.; Iserentant, D.; Malcorps, P.; Derdelinckx, G.; Van Dijck, P.; Winderickx, J.; Pretorius, I.S.; Thevelein, J.M.; Delvaux, F.R. Glucose and Sucrose: Hazardous Fast-Food for Industrial Yeast? Trends Biotechnol. 2004, 22, 531–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piper, P.W. Resistance of Yeasts to Weak Organic Acid Food Preservatives. In Advances in Applied Microbiology; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2011; Volume 77, pp. 97–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisson, L.F. Stuck and Sluggish Fermentations. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 1999, 50, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, D.; Tu, M.; Xie, R.; Li, J.; Wu, Y.; Adhikari, S. Inhibitory Activity of Carbonyl Compounds on Alcoholic Fermentation by Saccharomyces Cerevisiae. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014, 62, 918–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piper, P.; Calderon, C.O.; Hatzixanthis, K.; Mollapour, M. Weak Acid Adaptation: The Stress Response That Confers Yeasts with Resistance to Organic Acid Food Preservatives. Microbiology 2001, 147, 2635–2642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannattasio, S.; Guaragnella, N.; Ždralević, M.; Marra, E. Molecular Mechanisms of Saccharomyces Cerevisiae Stress Adaptation and Programmed Cell Death in Response to Acetic Acid. Front. Microbio. 2013, 4, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Wu, D.; Lin, Y.; Wang, X.; Kong, H.; Tanaka, S. Substrate and Product Inhibition on Yeast Performance in Ethanol Fermentation. Energy Fuels 2015, 29, 1019–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sales, A.L.; Cunha, S.C.; Morgado, J.; Cruz, A.; Santos, T.F.; Ferreira, I.M.P.L.V.O.; Fernandes, J.O.; Miguel, M.A.L.; Farah, A. Volatile, Microbial, and Sensory Profiles and Consumer Acceptance of Coffee Cascara Kombuchas. Foods 2023, 12, 2710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndiaye, O.; Hedrick, V.E.; Neill, C.L.; Carneiro, R.C.V.; Huang, H.; Fernandez-Fraguas, C.; Guiro, A.T.; O’Keefe, S.F. Consumer Responses and Willingness-to-Pay for Hibiscus Products: A Preliminary Study. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2023, 7, 1039203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaluvadi, S.; Hotchkiss, A.T.; Smith, B.; McVaugh, B.; White, A.K.; Guron, G.K.P.; Renye, J.A.; Yam, K.L. Key Kombucha Process Parameters for Optimal Bioactive Compounds and Flavor Quality. Fermentation 2024, 10, 605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacalone, D.; Frøst, M.B.; Bredie, W.L.P.; Pineau, B.; Hunter, D.C.; Paisley, A.G.; Beresford, M.K.; Jaeger, S.R. Situational Appropriateness of Beer Is Influenced by Product Familiarity. Food Qual. Prefer. 2015, 39, 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nacef, M.; Lelièvre-Desmas, M.; Symoneaux, R.; Jombart, L.; Flahaut, C.; Chollet, S. Consumers’ Expectation and Liking for Cheese: Can Familiarity Effects Resulting from Regional Differences Be Highlighted within a Country? Food Qual. Prefer. 2019, 72, 188–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, R.-R.; Chung, S.-J.; Cho, S.A.; Shin, H.W.; Harmayani, E. Learning to Know What You like: A Case Study of Repeated Exposure to Ethnic Flavors. Food Qual. Prefer. 2019, 71, 452–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimutai, S.; Wanyoko, J.; Kinyanjui, T.; Karori, S.; Muthiani, A.; Wachira, F. Determination of Residual Catechins, Polyphenolic Contents and Antioxidant Activities of Developed Theaflavin-3,3’-Digallate Rich Black Teas. Food Nutr. Sci. 2016, 7, 180–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.S.; Chung, J.Y.; Yang, G.; Li, C.; Meng, X.; Lee, M. Mechanisms of Inhibition of Carcinogenesis by Tea. BioFactors 2000, 13, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Wandawi, H.; Al-Shaikhly, K.; Abdul-Rahman, M. Roselle Seeds: A New Protein Source. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1984, 32, 510–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinoso-Carvalho, F.; Dakduk, S.; Wagemans, J.; Spence, C. Dark vs. Light Drinks: The Influence of Visual Appearance on the Consumer’s Experience of Beer. Food Qual. Prefer. 2019, 74, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Barón, S.E.; Carmona-Escutia, R.P.; Herrera-López, E.J.; Leyva-Trinidad, D.A.; Gschaedler-Mathis, A. Consumers’ Drivers of Perception and Preference of Fermented Food Products and Beverages: A Systematic Review. Foods 2025, 14, 713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, P.; Pitts, E.R.; Budner, D.; Thompson-Witrick, K.A. Chemical Composition of Kombucha. Beverages 2022, 8, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanišová, E.; Meňhartová, K.; Terentjeva, M.; Harangozo, Ľ.; Kántor, A.; Kačániová, M. The Evaluation of Chemical, Antioxidant, Antimicrobial and Sensory pro Perties of Kombucha Tea Beverage. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 57, 1840–1846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubaidah, E.; Yurista, S.; Rahmadani, N.R. Characteristic of Physical, Chemical, and Microbiological Kombucha From Various Varieties of Apples. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2018, 131, 012040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poll, L. Evaluation of 18 Apple Varieties for Their Suitability for Juice Production. J. Sci. Food Agric. 1981, 32, 1081–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Xiao, G.; Xu, Y.; Wu, J.; Fu, M.; Wen, J. Slight Fermentation with Lactobacillus fermentium Improves the Taste (Sugar:Acid Ratio) of Citrus (Citrus reticulata Cv. Chachiensis) Juice. J. Food Sci. 2015, 80, M2543–M2547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, J.; Bijmolt, T.H.A. Accurately Measuring Willingness to Pay for Consumer Goods: A Meta-Analysis of the Hypothetical Bias. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2020, 48, 499–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]