Abstract

Background/Objectives: The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) into dental diagnostics is rapidly evolving, offering opportunities to improve diagnostic precision, reproducibility, and accessibility of care. This systematic review examined the clinical performance of AI-based diagnostic tools in dentistry compared with traditional methods, with particular attention to radiographic assessment, orthodontic classification, periodontal disease detection, and other relevant specialties. Methods: Comprehensive searches of PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science were carried out for articles published from January 2015 to June 2025, in accordance with PRISMA guidelines. Only English-language clinical studies investigating AI applications in dental diagnostics were included. Fifteen studies fulfilled the inclusion criteria and underwent quality appraisal and risk-of-bias assessment. Results: Across diverse dental fields, AI systems showed encouraging diagnostic capabilities. Radiographic algorithms enhanced lesion detection and anatomical landmark identification, while machine learning models successfully classified malocclusions and periodontal status. Photographic image analysis demonstrated potential in geriatric and preventive care. However, methodological variability, limited sample sizes, and the absence of external validation constrained generalizability. Study quality ranged from high to moderate, with some reports affected by bias or incomplete data reporting. Conclusions: AI holds considerable promise as an adjunct in dental diagnostics, particularly for imaging-based evaluation and clinical decision support. Broader clinical adoption will require methodological harmonization, rigorous multicenter trials, and validation of AI systems across diverse patient populations.

1. Introduction

Artificial intelligence (AI) is increasingly being recognized as a practical tool in dentistry, with applications extending from image-based diagnostics to risk prediction models [1]. Rather than remaining a distant or purely theoretical concept, AI has already been implemented in specific diagnostic workflows, supported by a growing body of research that demonstrates its utility in processing complex datasets, detecting subtle radiographic features, and synthesizing large volumes of clinical information [2,3,4,5,6,7]. These capabilities offer opportunities to improve diagnostic precision, reproducibility, and efficiency across a range of dental specialties [8,9].

Recent investigations have explored AI applications in key diagnostic challenges, ranging from the detection of periapical lesions on radiographs to the classification of skeletal malocclusions and the prediction of periodontal disease risk [10,11]. In several diagnostic domains—particularly those involving repetitive tasks or prone to inter-operator variability—AI performance has equaled or surpassed that of experienced clinicians [12]. Beyond improving diagnostic accuracy, AI holds potential to expand access to care, providing decision-support tools for practitioners in remote or resource-limited settings and enabling earlier screening and monitoring pathways [13,14,15,16].

One of AI’s most compelling attributes is its adaptability [17,18,19]. Whether applied to anatomical landmark detection in cone beam computed tomography or to photographic analysis of the oral cavity in geriatric patients, AI models can be tailored to diverse clinical contexts [20,21,22]. Nonetheless, current development is hindered by notable limitations: many systems are trained on small, single-institution datasets, rarely undergo external validation, and often rely on retrospective designs with heterogeneous labeling protocols [23,24,25,26]. These factors, combined with the absence of standardized methodological frameworks, can limit clinical applicability [27,28,29,30,31]. Additionally, as AI tools begin to exert greater influence on diagnostic decision-making, concerns regarding transparency, bias, and ethical deployment must be addressed [32,33,34,35].

Despite these constraints, the trajectory of AI integration into dental diagnostics is unmistakable [36,37,38,39,40]. It is poised to become a routine component of diagnostic workflows, complementing rather than replacing human clinical judgment. When implemented thoughtfully, AI can strengthen decision-making, reduce diagnostic variability, and contribute to equitable and high-quality patient care.

This review synthesizes recent evidence on AI applications in dental diagnostics, with emphasis on radiographic interpretation, orthodontic classification, periodontal and peri-implant disease screening, and geriatric oral health. By highlighting both the current capabilities and the existing shortcomings of these technologies, we aim to provide a balanced, evidence-based perspective to guide their integration into everyday practice. In doing so, we also seek to outline realistic expectations for the role of AI in dentistry—where it currently stands and where it may be headed (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of diagnostic methods with AI assistance.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. PICO Question

The PICO approach is typically used to evaluate the effect of an intervention on a specific condition, in this case, the use of AI and its implication in dentistry.

In patients undergoing dental diagnostic procedures (P), does the application of artificial intelligence technologies—such as machine learning and deep learning (I)—enhance diagnostic accuracy and efficiency (C) compared to conventional diagnostic methods performed by dental professionals (O)?

By comparing AI-based approaches with traditional diagnostic techniques, this review seeks to evaluate the effectiveness and clinical value of AI in dental diagnostics, particularly in terms of performance, reliability, and its potential to support clinical decision-making.

2.2. Protocol and Registration

Our search was performed following the method of Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines and registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Review Registry guidelines (PROSPERO ID: CRD420251104023).

2.3. Search Processing

The electronic databases PubMed, Scopus and Web of Science were searched to find papers that matched our topic dating from 1 January 2015, up to 30 June 2025. The Medical Subject Headings (MESH) terms entered in search engines were: (“artificial intelligence” OR “machine learning” OR “deep learning” OR “neural networks”) AND (“dental” OR “dentistry” OR “oral health” OR “odontology”) AND (“diagnosis” OR “diagnostic” OR “detection” OR “screening”) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Article screening strategy.

2.4. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The inclusion criteria were the following: (1) English language; (2) any type of observational study, i.e., retrospective cohort, prospective cohort, cross-sectional and randomized controlled trials; (3) open access; (4) articles concerning the use of AI in dental diagnostics.

The exclusion criteria were the following: (1) other languages except English; (2) reviews, meta-analysis and case–control; (3) off-topic articles; (4) in vivo studies; (5) in vitro studies.

2.5. Data Processing

The reviewers (A.F., L.B., C.C.) screened the records according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Doubts have been resolved by consulting the senior reviewer (F.I.). The selected articles were downloaded into Zotero.

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection and Characteristics

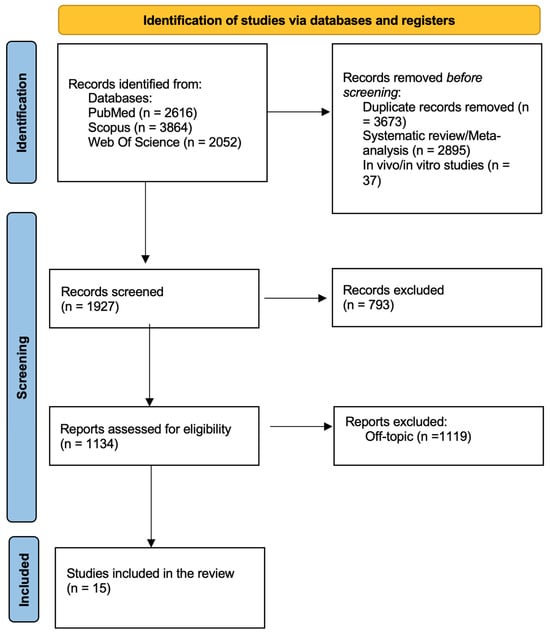

A total of 8532 records were identified using the keywords (“artificial intelligence” OR “machine learning” OR “deep learning” OR “neural networks”) AND (“dental” OR “dentistry” OR “oral health” OR “odontology”) AND (“diagnosis” OR “diagnostic” OR “detection” OR “screening”). When applicable, the automatic filters entered were only in English, only clinical studies and free full text. The consulted databases were PubMed (2616), Scopus (3864) and Web of Science (2052).

After screening, 3673 duplicated articles, 2895 systematic reviews/meta-analysis and 37 in vivo/in vitro studies were excluded. Then 793 articles were excluded by the analysis of titles, leading to 1134 records assessed for eligibility. After eligibility assessment, 15 studies (Table 2) were included in the final analysis, and 1119 were excluded by the abstract. The process is summarized in Figure 2.

Table 2.

Analysis of the studies included in the discussion section.

Figure 2.

PRISMA flow diagram illustrating the study selection process.

3.2. Quality Assessment and Risk of Bias of Included Articles

A structured risk of bias evaluation was performed across seven domains to evaluate the methodological quality of the included studies: (D1) bias resulting from confounding; (D2) bias resulting from exposure measurement; (D3) bias in the selection of study participants; (D4) bias resulting from post-exposure interventions; (D5) bias resulting from missing data; (D6) bias resulting from outcome measurement; and (D7) bias in the selection of the reported result. The approach was adapted from the ROBINS-I tool to better fit the characteristics of diagnostic AI studies, where exposures correspond to algorithmic applications rather than clinical interventions. The seven domains were retained, but the terminology and examples were adjusted to reflect diagnostic accuracy outcomes and dataset-related biases [56].

Every study was assessed and categorized by domain as either low risk, high risk, extremely high risk, some concerns, or no information. Most studies (60%) had some issues in at least one area, especially with regard to participant selection (D3), outcome assessment (D6), and confounding factors (D1). This was particularly true for cross-sectional and observational research, where blinding was frequently not disclosed and participant allocation was not randomized.

The five studies (Navarro-Fraile et al., Wang et al., Al-Sarem et al., Pul et al., and Zhou et al.) were noteworthy for their robust methodologies, which included randomization, objective outcome measurement (e.g., CBCT, segmentation accuracy), and complete reporting. These studies were deemed to have an overall low risk of bias.

On the other hand, three studies (Uribe et al., Muramatsu et al., and Pépin et al.) were judged to have a high overall risk of bias, mainly because of subjective outcome assessments, inadequate reporting, and poorly controlled confounding variables. Despite being systematic, the Uribe et al. study had high risk in several categories since it lacked objective measures for evaluating exposure and outcomes as well as uniform criteria for dataset inclusion.

Some issues were found with the remaining studies (e.g., Stillhart, Deng, Ghensi, Yıldız), especially with regard to the use of subjective pain or diagnostic scores without uniform calibration across examiners, potential selection bias, and the transparency of data management.

Overall, even though a few of studies showed excellent methodological rigor, the sample’s variation in design quality and reporting procedures highlights the need for more uniformity in AI-focused diagnostic research in dentistry. When evaluating generalizability to clinical practice or interpreting pooled findings, risk of bias should be taken into account.

A summary of the risk of bias for each study is provided in Table 3.

Table 3.

Risk of bias of the articles.

4. Discussion

The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) into dental diagnostics represents a rapidly evolving frontier in clinical practice and research [57,58]. Across various branches of dentistry, AI has demonstrated the ability to improve diagnostic accuracy, reduce variability, and support clinical decision-making through automated data analysis [59,60]. This discussion synthesizes the findings from recent studies on AI applications in different dental specialties, highlighting progress, common challenges, and areas for future development.

4.1. Radiographic and Imaging Diagnostics

A significant portion of the included studies focused on the use of artificial intelligence in radiographic interpretation and anatomical landmark detection [42,50,61]. Pul et al. (2024) and Zhou et al. (2025) showed that AI support significantly improved the diagnostic accuracy of dentists in identifying periapical radiolucency, especially among less experienced clinicians [51,55,62]. Picoli et al. (2023) further demonstrated AI’s utility by comparing 3D AI-generated models with CBCT and panoramic imaging for third molar risk assessment, concluding that AI offers a reliable alternative for presurgical planning [52]. Wang et al. (2025) and Al-Sarem et al. (2024) explored AI’s role in CBCT analysis, particularly in automating mandibular landmark detection and dental structure segmentation, helping to simplify implant planning and asymmetry analysis [45,46]. These studies highlight how AI tools can support more precise and consistent image interpretation, regardless of clinical experience [63,64,65].

4.2. Orthodontics and Skeletal Malocclusion Assessment

AI applications in orthodontics were investigated in several studies [66,67,68]. Midlej et al. (2024) developed machine learning models with high accuracy (up to 0.99) for classifying skeletal class II and III malocclusions using cephalometric data [53]. Schwab et al. (2024), although not using AI, provided normative morphological data on the sella turcica in the Austrian population, useful as a reference for future AI model training [44,69]. Navarro-Fraile et al. (2024) applied AI-based segmentation tools to assess orthodontic treatment-related root resorption, showing comparable results to manual analysis [42,70,71]. These findings confirm the growing role of AI in orthodontic diagnosis and treatment planning [72,73,74].

4.3. Periodontology and Implantology

Deng et al. (2023) proposed an innovative strategy for periodontal screening by combining artificial intelligence with salivary biomarkers and self-reported indicators. Their findings demonstrated encouraging potential for non-clinical and rapid screening approaches, although diagnostic accuracy remained limited by the binary nature of traditional classification methods. In contrast, Ghensi et al. (2025) investigated the peri-implant microbiome through shotgun metagenomic analysis, revealing that a patient’s history of periodontitis plays a crucial role in shaping early biofilm formation around implants. Shotgun genomics (or shotgun metagenomics) is a DNA sequencing technique that analyzes all the genetic material present in a sample. The DNA is fragmented, sequenced, and reconstructed using computational algorithms, allowing the identification of all microorganisms present and the study of their diversity, providing a more comprehensive view compared to traditional targeted methods [47,48].

This study underscores the relevance of microbiome-based profiling for identifying early signs of peri-implant disease and tailoring preventive strategies. Taken together, these contributions illustrate how advanced computational tools and omics-based analyses are reshaping oral diagnostics. Artificial intelligence, when integrated with biological and microbial data, holds promise for more precise, personalized, and predictive models of screening and disease prevention in periodontal and peri-implant care.

4.4. Geriatric and Preventive Dentistry

Muramatsu et al. (2021) specifically addressed the needs of the aging population by developing convolutional neural networks (CNNs) capable of assessing oral health status from simple photographic images. Their system demonstrated strong performance in identifying markers such as poor oral hygiene, mucosal dryness, and other signs associated with progressive oral health deterioration. Importantly, this approach illustrates how AI-based image analysis can reduce reliance on resource-intensive clinical examinations, offering a viable solution for populations with limited access to dental professionals [49,75,76]. For elderly patients—who are often homebound, institutionalized, or living in remote areas—such tools could provide timely monitoring, early detection of oral health decline, and prompt referral for appropriate care. The study therefore highlights the broader potential of artificial intelligence in promoting equitable oral healthcare delivery, while also suggesting avenues for integrating CNN-based screening into telemedicine and community care settings [77,78,79].

4.5. Orofacial Pain and Temporomandibular Disorders

Yıldız et al. (2023) developed AI-based predictive models for diagnosing temporomandibular disorders (TMD) using clinical and psychological data [50,80,81]. Their ensemble model (Bagging MARS) achieved the best results, particularly in settings without radio-diagnostic tools. Stillhart et al. (2024) explored the use of automated facial recognition to detect dental pain expressions but found limited sensitivity to expression changes [41,49,51]. These studies open new possibilities for non-invasive diagnostic support in orofacial pain.

4.6. Sleep Medicine in Dentistry

Pépin et al. (2024) introduced an AI-based approach to analyse mandibular movements in patients with obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA) treated with oral appliances [54]. The model was able to distinguish sleep stages and respiratory events based on mandibular signals, suggesting a potential non-invasive, home-based alternative to traditional polysomnography [82,83,84,85,86,87,88].

4.7. Limitations and Future Directions

Despite the promising results, the studies analysed present several limitations [89,90,91,92,93,94,95]. Many had small sample sizes, such as those reported by Picoli, R. S., et al. (2021) and Pul, M., et al. (2022), limiting the generalizability of the findings. Some investigations, including Stillhart, A., et al. (2024), reported insufficient sensitivity of AI models to specific clinical cues like pain expressions. Several studies were based on retrospective data, for example, Muramatsu, C., et al. (2021) and Navarro-Fraile, J., et al. (2023), which may introduce bias and weaken causal inference. Furthermore, limited dataset standardization, as highlighted by Uribe, S., et al. (2024), and the lack of external validation represent critical obstacles to clinical translation [41,42,43,49,51,52]. Future research should prioritize multicentre trials, standardized data collection, and rigorous prospective validation [43,96,97]. Future research should prioritize multicenter trials, standardized data collection, and rigorous prospective validation [46]. Moreover, it is important to provide a broader interpretation of the results in the context of existing literature, highlighting how our findings fit within the current body of research on the role of artificial intelligence in dentistry. In this perspective, the integration between AI-based algorithms and computer software should also be explored, as exemplified by the Co-Mask R-CNN collaborative learning-based method for tooth instance segmentation, as well as the use of smartphone applications, which are emerging as valuable tools to support daily clinical practice [98,99]. These integrations represent potential future developments to enhance accessibility, efficiency, and personalization in dental care. Addressing model transparency and ethical considerations is also essential to foster trust and adoption in everyday dental practice.

4.8. Ethical, Medico-Legal, and Cognitive Considerations

Beyond the technical and methodological limitations, the integration of AI into dental practice also raises important medico-legal and ethical challenges. Issues related to data privacy and security are particularly relevant, as the use of sensitive patient data for training and deploying AI models requires strict compliance with regulations such as General Data Protection Regulation and Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, alongside robust anonymization and cybersecurity measures to protect against misuse [30,43]. Moreover, medico-legal accountability remains a critical question: in cases of diagnostic errors or treatment failures, it is unclear whether liability should rest with the clinician, the AI developer, or the healthcare institution. Another important concern is the potential for automation bias, where clinicians may over-rely on AI-generated outputs and neglect their own clinical judgment. Such overdependence could lead to errors, especially when AI models encounter atypical or underrepresented cases not adequately captured in training datasets [100,101]. To mitigate these risks, AI systems should be implemented as decision-support tools rather than autonomous diagnostic agents, with clear guidelines promoting clinician oversight, transparency, and interpretability. This critical reflection emphasizes that the future of AI in dentistry depends not only on technological advances but also on establishing ethical frameworks, medico-legal safeguards, and education strategies to support responsible and balanced adoption [75,102,103].

5. Conclusions

The application of artificial intelligence in dental diagnostics holds considerable potential for improving diagnostic accuracy, efficiency, and clinical decision-making. Recent evidence highlights that AI-based tools, particularly those employed for radiographic analysis and automated classification of oral conditions, can help reduce inter-operator variability and enhance diagnostic reliability. These advantages are especially relevant in settings with limited resources or among less experienced clinicians, where AI can act as a valuable decision-support tool.

Nevertheless, the current body of research is limited by heterogeneous methodological quality, the absence of standardized datasets, and insufficient external validation, which constrain the generalizability and clinical implementation of these findings. Future research should prioritize multicentre, prospective studies with harmonized protocols, rigorous external validation, and transparent AI algorithms. Addressing these challenges will be essential to ensure the safe, effective, and ethically responsible integration of AI into routine dental practice, ultimately supporting improved patient outcomes and more equitable oral healthcare delivery.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.D.I., G.M. and A.F.; methodology, L.B., C.C. and M.C.; software, D.D.V., F.I. and A.M.I.; validation, G.D. and A.P.; formal analysis, A.D.I., G.M. and A.F.; investigation, L.B., C.C. and M.C.; resources, D.D.V., F.I. and A.M.I.; data curation, G.D. and A.P.; writing—original draft preparation, A.D.I., G.M. and A.F.; writing—review and editing, L.B., C.C. and M.C.; visualization, D.D.V., F.I. and A.M.I.; supervision, G.D. and A.P.; project administration, A.D.I., G.M. and A.F.; funding acquisition, L.B., C.C. and M.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AFC | Automated Face Coding |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| CBCT | Cone Beam Computed Tomography |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| IAN | Inferior Alveolar Nerve |

| M3M | Mandibular Third Molar |

| MESH | Medical Subject Headings |

| MJA | Mandibular Jaw Movement Analysis |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| OSA | Obstructive Sleep Apnea |

| PCA | Principal Component Analysis |

| RF | Random Forest |

| SVM | Support Vector Machine |

| TMD | Temporomandibular Disorders |

| VAS | Visual Analogue Scale |

References

- Nguyen, T.T.; Larrivée, N.; Lee, A.; Bilaniuk, O.; Durand, R. Use of Artificial Intelligence in Dentistry: Current Clinical Trends and Research Advances. J. Can. Dent. Assoc. 2021, 87, l7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, A.; Alderman, J.E.; Palmer, J.; Ganapathi, S.; Laws, E.; McCradden, M.D.; Oakden-Rayner, L.; Pfohl, S.R.; Ghassemi, M.; McKay, F.; et al. The Value of Standards for Health Datasets in Artificial Intelligence-Based Applications. Nat. Med. 2023, 29, 2929–2938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Findik, Y.; Yildirim, D.; Baykul, T. Three-Dimensional Anatomic Analysis of the Lingula and Mandibular Foramen: A Cone Beam Computed Tomography Study. J. Craniofac. Surg. 2014, 25, 607–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, K.-H.; Lee, K.-J.; Lee, S.-H.; Baik, H.-S. Three-Dimensional Computed Tomography Analysis of Mandibular Morphology in Patients with Facial Asymmetry and Mandibular Prognathism. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2010, 138, 540.e1-e8; discussion 540–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuzoff, D.V.; Tuzova, L.N.; Bornstein, M.M.; Krasnov, A.S.; Kharchenko, M.A.; Nikolenko, S.I.; Sveshnikov, M.M.; Bednenko, G.B. Tooth Detection and Numbering in Panoramic Radiographs Using Convolutional Neural Networks. Dentomaxillofac. Radiol. 2019, 48, 20180051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zohud, O.; Lone, I.M.; Midlej, K.; Obaida, A.; Masarwa, S.; Schröder, A.; Küchler, E.C.; Nashef, A.; Kassem, F.; Reiser, V.; et al. Towards Genetic Dissection of Skeletal Class III Malocclusion: A Review of Genetic Variations Underlying the Phenotype in Humans and Future Directions. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 3212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inchingolo, F.; Dipalma, G.; Paduanelli, G.; De Oliveira, L.A.; Inchingolo, A.M.; Georgakopoulos, P.I.; Inchingolo, A.D.; Malcangi, G.; Athanasiou, E.; Fotopoulou, E.; et al. Computer-Based Quantification of an Atraumatic Sinus Augmentation Technique Using CBCT. J. Biol. Regul. Homeost. Agents 2019, 33, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Silverman, F.N. Roentgen Standards Fo-Size of the Pituitary Fossa from Infancy through Adolescence. Am. J. Roentgenol. Radium Ther. Nucl. Med. 1957, 78, 451–460. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Aro, K.; Wei, F.; Wong, D.T.; Tu, M. Saliva Liquid Biopsy for Point-of-Care Applications. Front. Public. Health 2017, 5, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, G.S.; Reitsma, J.B.; Altman, D.G.; Moons, K.G.M. Transparent Reporting of a Multivariable Prediction Model for Individual Prognosis or Diagnosis (TRIPOD): The TRIPOD Statement. BMC Med. 2015, 13, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dipalma, G.; Inchingolo, A.D.; Inchingolo, A.M.; Piras, F.; Carpentiere, V.; Garofoli, G.; Azzollini, D.; Campanelli, M.; Paduanelli, G.; Palermo, A.; et al. Artificial Intelligence and Its Clinical Applications in Orthodontics: A Systematic Review. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 3677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topol, E.J. High-Performance Medicine: The Convergence of Human and Artificial Intelligence. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceratti, C.; Maspero, C.; Consonni, D.; Caprioglio, A.; Connelly, S.T.; Inchingolo, F.; Tartaglia, G.M. Cone-Beam Computed Tomographic Assessment of the Mandibular Condylar Volume in Different Skeletal Patterns: A Retrospective Study in Adult Patients. Bioengineering 2022, 9, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maspero, C.; Abate, A.; Inchingolo, F.; Dolci, C.; Cagetti, M.G.; Tartaglia, G.M. Incidental Finding in Pre-Orthodontic Treatment Radiographs of an Aural Foreign Body: A Case Report. Children 2022, 9, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malcangi, G.; Patano, A.; Guglielmo, M.; Sardano, R.; Palmieri, G.; Di Pede, C.; de Ruvo, E.; Inchingolo, A.D.; Mancini, A.; Inchingolo, F.; et al. Precision Medicine in Oral Health and Diseases: A Systematic Review. J. Pers. Med. 2023, 13, 725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarano, A.; Noumbissi, S.; Gupta, S.; Inchingolo, F.; Stilla, P.; Lorusso, F. Scanning Electron Microscopy Analysis and Energy Dispersion X-Ray Microanalysis to Evaluate the Effects of Decontamination Chemicals and Heat Sterilization on Implant Surgical Drills: Zirconia vs. Steel. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 2837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segù, M.; Campagnoli, G.; Di Blasio, M.; Santagostini, A.; Pollis, M.; Levrini, L. Pilot Study of a New Mandibular Advancement Device. Dent. J. 2022, 10, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maret, D.; Telmon, N.; Treil, J.; Caron, P.; Nabet, C. Pituitary Adenoma as an Incidental Finding in Dental Radiology: A Case Report. Ann. Intern. Med. 2014, 160, 290–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Correa, L.R.; Spin-Neto, R.; Stavropoulos, A.; Schropp, L.; da Silveira, H.E.D.; Wenzel, A. Planning of Dental Implant Size with Digital Panoramic Radiographs, CBCT-Generated Panoramic Images, and CBCT Cross-Sectional Images. Clin. Oral. Implants Res. 2014, 25, 690–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimonte, M.; Inchingolo, F.; Minonne, A.; Arditi, G.; Dipalma, G. Bone SPECT in Management of Mandibular Condyle Hyperplasia. Report of a Case and Review of Literature. Minerva Stomatol. 2004, 53, 281–285. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Inchingolo, F.; Pacifici, A.; Gargari, M.; Acitores Garcia, J.I.; Amantea, M.; Marrelli, M.; Dipalma, G.; Inchingolo, A.M.; Rinaldi, R.; Inchingolo, A.D.; et al. CHARGE Syndrome: An Overview on Dental and Maxillofacial Features. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2014, 18, 2089–2093. [Google Scholar]

- Balzanelli, M.; Distratis, P.; Catucci, O.; Amatulli, F.; Cefalo, A.; Lazzaro, R.; Aityan, K.S.; Dalagni, G.; Nico, A.; De Michele, A.; et al. Clinical and Diagnostic Findings in COVID-19 Patients: An Original Research from SG Moscati Hospital in Taranto Italy. J. Biol. Regul. Homeost. Agents 2021, 35, 171–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talaat, W.M.; Adel, O.I.; Al Bayatti, S. Prevalence of Temporomandibular Disorders Discovered Incidentally during Routine Dental Examination Using the Research Diagnostic Criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders. Oral. Surg. Oral. Med. Oral. Pathol. Oral. Radiol. 2018, 125, 250–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valesan, L.F.; Da-Cas, C.D.; Réus, J.C.; Denardin, A.C.S.; Garanhani, R.R.; Bonotto, D.; Januzzi, E.; de Souza, B.D.M. Prevalence of Temporomandibular Joint Disorders: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin. Oral. Investig. 2021, 25, 441–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, L.; Zhang, L.-X.; Meng, H.-Y.; Ren, Y.-H.; Lai, Y.-K.; Kobbelt, L. PRS-Net: Planar Reflective Symmetry Detection Net for 3D Models. IEEE Trans. Vis. Comput. Graph. 2021, 27, 3007–3018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurusu, A.; Horiuchi, M.; Soma, K. Relationship between Occlusal Force and Mandibular Condyle Morphology. Evaluated by Limited Cone-Beam Computed Tomography. Angle Orthod. 2009, 79, 1063–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashir, N.Z.; Rahman, Z.; Chen, S.L.-S. Systematic Comparison of Machine Learning Algorithms to Develop and Validate Predictive Models for Periodontitis. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2022, 49, 958–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, J.; Durham, J. Temporomandibular Disorders. BJA Educ. 2021, 21, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, A. The “Wits” Appraisal of Jaw Disharmony. Am. J. Orthod. 1975, 67, 125–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagl, B.; Schmid-Schwap, M.; Piehslinger, E.; Rausch-Fan, X.; Stavness, I. The Effect of Tooth Cusp Morphology and Grinding Direction on TMJ Loading during Bruxism. Front. Physiol. 2022, 13, 964930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Touche, R.; Fernández-de-las-Peñas, C.; Fernández-Carnero, J.; Escalante, K.; Angulo-Díaz-Parreño, S.; Paris-Alemany, A.; Cleland, J.A. The Effects of Manual Therapy and Exercise Directed at the Cervical Spine on Pain and Pressure Pain Sensitivity in Patients with Myofascial Temporomandibular Disorders. J. Oral. Rehabil. 2009, 36, 644–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, D.E.; Holtzman, D.; Bolen, J.; Stanwyck, C.A.; Mack, K.A. Reliability and Validity of Measures from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS). Soz. Praventivmed. 2001, 46 (Suppl. S1), S3–S42. [Google Scholar]

- Martinot, J.-B.; Le-Dong, N.-N.; Malhotra, A.; Pépin, J.-L. Respiratory Effort during Sleep and Prevalent Hypertension in Obstructive Sleep Apnoea. Eur. Respir. J. 2023, 61, 2201486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaêta-Araujo, H.; Oliveira-Santos, N.; Mancini, A.X.M.; Oliveira, M.L.; Oliveira-Santos, C. Retrospective Assessment of Dental Implant-Related Perforations of Relevant Anatomical Structures and Inadequate Spacing between Implants/Teeth Using Cone-Beam Computed Tomography. Clin. Oral. Investig. 2020, 24, 3281–3288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vervaeke, S.; Collaert, B.; Cosyn, J.; Deschepper, E.; De Bruyn, H. A Multifactorial Analysis to Identify Predictors of Implant Failure and Peri-Implant Bone Loss. Clin. Implant. Dent. Relat. Res. 2015, 17 (Suppl. S1), e298–e307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heitz-Mayfield, L.J.A. Peri-Implant Diseases: Diagnosis and Risk Indicators. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2008, 35, 292–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcantonio Junior, E.; Romito, G.A.; Shibli, J.A. Peri-Implantitis as a “Burden” Disease. Braz. Oral. Res. 2019, 33, e087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chapple, I.L.C.; Mealey, B.L.; Van Dyke, T.E.; Bartold, P.M.; Dommisch, H.; Eickholz, P.; Geisinger, M.L.; Genco, R.J.; Glogauer, M.; Goldstein, M.; et al. Periodontal Health and Gingival Diseases and Conditions on an Intact and a Reduced Periodontium: Consensus Report of Workgroup 1 of the 2017 World Workshop on the Classification of Periodontal and Peri-Implant Diseases and Conditions. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2018, 45 (Suppl. S20), S68–S77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamp, S.E.; Nyman, S.; Lindhe, J. Periodontal Treatment of Multirooted Teeth. Results after 5 Years. J. Clin. Periodontol. 1975, 2, 126–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, J.; Lobbezoo, F.; van Selms, M.K.A.; Chattrattrai, T.; Aarab, G.; Mitrirattanakul, S. Physical, Psychological and Socio-Demographic Predictors Related to Patients’ Self-Belief of Their Temporomandibular Disorders’ Aetiology. J. Oral. Rehabil. 2021, 48, 109–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stillhart, A.; Häfliger, R.; Takeshita, L.; Stadlinger, B.; Leles, C.R.; Srinivasan, M. Screening for Dental Pain Using an Automated Face Coding (AFC) Software. J. Dent. 2025, 155, 105647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrella, N.-F.; Alexandra, D.-S.; Yun, C.; Palma-Fernández, J.C.; Alejandro, I.-L. AI-aided volumetric root resorption assessment following personalized forces in orthodontics: Preliminary results of a randomized clinical trial. J. Evid. Based Dent. Pract. 2025, 25, 102095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uribe, S.E.; Issa, J.; Sohrabniya, F.; Denny, A.; Kim, N.N.; Dayo, A.F.; Chaurasia, A.; Sofi-Mahmudi, A.; Büttner, M.; Schwendicke, F. Publicly Available Dental Image Datasets for Artificial Intelligence. J. Dent. Res. 2024, 103, 1365–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwab, J.; Stucki, L.; Fitzek, S.; Tithphit, A.; Hönigl, A.; Stackmann, S.; Horn, I.; Thenner, H.; Dasser, P.; Woitek, R.; et al. Radiological Assessment of Sella Turcica Morphology Correlates with Skeletal Classes in an Austrian Population: An Observational Study. Oral. Radiol. 2025, 41, 169–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wu, W.; Christelle, M.; Sun, M.; Wen, Z.; Lin, Y.; Zhang, H.; Xu, J. Automated Localization of Mandibular Landmarks in the Construction of Mandibular Median Sagittal Plane. Eur. J. Med. Res. 2024, 29, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Sarem, M.; Al-Asali, M.; Alqutaibi, A.Y.; Saeed, F. Enhanced Tooth Region Detection Using Pretrained Deep Learning Models. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2022, 19, 15414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, K.; Zonta, F.; Yang, H.; Pelekos, G.; Tonetti, M.S. Development of a Machine Learning Multiclass Screening Tool for Periodontal Health Status Based on Non-Clinical Parameters and Salivary Biomarkers. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2024, 51, 1547–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghensi, P.; Heidrich, V.; Bazzani, D.; Asnicar, F.; Armanini, F.; Bertelle, A.; Dell’Acqua, F.; Dellasega, E.; Waldner, R.; Vicentini, D.; et al. Shotgun Metagenomics Identifies in a Cross-Sectional Setting Improved Plaque Microbiome Biomarkers for Peri-Implant Diseases. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2025, 52, 999–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muramatsu, M.; Muramatsu, M.; Takahashi, N.; Hagiwara, A.; Hagiwara, J.; Takamatsu, Y.; Morooka, R.; Ochi, M.; Kaitani, T. Image Diagnosis Models for the Oral Assessment of Older People Using Convolutional Neural Networks: A Retrospective Observational Study. J. Clin. Nurs. 2022, 31, 3550–3559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldız, N.T.; Kocaman, H.; Yıldırım, H.; Canlı, M. An Investigation of Machine Learning Algorithms for Prediction of Temporomandibular Disorders by Using Clinical Parameters. Medicine 2024, 103, e39912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pul, U.; Tichy, A.; Pitchika, V.; Schwendicke, F. Impact of Artificial Intelligence Assistance on Diagnosing Periapical Radiolucencies: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Dent. 2025, 160, 105868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Picoli, F.F.; Fontenele, R.C.; Van der Cruyssen, F.; Ahmadzai, I.; Trigeminal Nerve Injuries Research Group; Politis, C.; Silva, M.A.G.; Jacobs, R. Risk Assessment of Inferior Alveolar Nerve Injury after Wisdom Tooth Removal Using 3D AI-Driven Models: A within-Patient Study. J. Dent. 2023, 139, 104765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Midlej, K.; Watted, N.; Awadi, O.; Masarwa, S.; Lone, I.M.; Zohud, O.; Paddenberg, E.; Krohn, S.; Kuchler, E.; Proff, P.; et al. Lateral Cephalometric Parameters among Arab Skeletal Classes II and III Patients and Applying Machine Learning Models. Clin. Oral. Investig. 2024, 28, 511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pépin, J.-L.; Cistulli, P.A.; Crespeigne, E.; Tamisier, R.; Bailly, S.; Bruwier, A.; Le-Dong, N.-N.; Lavigne, G.; Malhotra, A.; Martinot, J.-B. Mandibular Jaw Movement Automated Analysis for Oral Appliance Monitoring in Obstructive Sleep Apnea: A Prospective Cohort Study. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2024, 21, 814–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui, H.; Xiao, M.; Jiang, X.; Li, J.; Qiao, F.; Yin, B.; Wang, Y.; Wu, L. Development and Validation of a Predictive Nomogram for Bilateral Posterior Condylar Displacement Using Cone-Beam Computed Tomography and Machine-Learning Algorithms: A Retrospective Observational Study. BMC Oral. Health 2025, 25, 916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterne, J.A.; Hernán, M.A.; Reeves, B.C.; Savović, J.; Berkman, N.D.; Viswanathan, M.; Henry, D.; Altman, D.G.; Ansari, M.T.; Boutron, I.; et al. ROBINS-I: A Tool for Assessing Risk of Bias in Non-Randomised Studies of Interventions. BMJ 2016, 355, i4919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Wang, J.; Huang, D.; Wang, Z.; Hu, M.; Liu, H.; Jiang, H. A Comparative Study of Condyle Position in Temporomandibular Disorder Patients with Chewing Side Preference Using Cone-Beam Computed Tomography. J. Oral. Rehabil. 2022, 49, 265–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozsari, S.; Güzel, M.S.; Yılmaz, D.; Kamburoğlu, K. A Comprehensive Review of Artificial Intelligence Based Algorithms Regarding Temporomandibular Joint Related Diseases. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 2700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pittayapat, P.; Jacobs, R.; Bornstein, M.M.; Odri, G.A.; Kwon, M.S.; Lambrichts, I.; Willems, G.; Politis, C.; Olszewski, R. A New Mandible-Specific Landmark Reference System for Three-Dimensional Cephalometry Using Cone-Beam Computed Tomography. Eur. J. Orthod. 2016, 38, 563–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Melo, F.; Milanesi, F.C.; Angst, P.D.M.; Oppermann, R.V. A Systematic Review of the Microbiota Composition in Various Peri-Implant Conditions: Data from 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing. Arch. Oral. Biol. 2020, 117, 104776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Salvador, A.; Torres-Sánchez, I.; Sáez-Roca, G.; López-Torres, I.; Rodríguez-Alzueta, E.; Valenza, M.C. Age Group Analysis of Psychological, Physical and Functional Deterioration in Patients Hospitalized for Pneumonia. Arch. Bronconeumol. 2015, 51, 496–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sorsa, T.; Gursoy, U.K.; Nwhator, S.; Hernandez, M.; Tervahartiala, T.; Leppilahti, J.; Gursoy, M.; Könönen, E.; Emingil, G.; Pussinen, P.J.; et al. Analysis of Matrix Metalloproteinases, Especially MMP-8, in Gingival Creviclular Fluid, Mouthrinse and Saliva for Monitoring Periodontal Diseases. Periodontology 2016, 70, 142–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikeda, K.; Kawamura, A.; Ikeda, R. Assessment of Optimal Condylar Position in the Coronal and Axial Planes with Limited Cone-Beam Computed Tomography. J. Prosthodont. 2011, 20, 432–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gada, S.K.; Nagda, S.J. Assessment of Position and Bilateral Symmetry of Occurrence of Mental Foramen in Dentate Asian Population. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2014, 8, 203–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paknahad, M.; Shahidi, S. Association between Mandibular Condylar Position and Clinical Dysfunction Index. J. Craniomaxillofac. Surg. 2015, 43, 432–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerhardt, M.d.N.; Fontenele, R.C.; Leite, A.F.; Lahoud, P.; Van Gerven, A.; Willems, H.; Smolders, A.; Beznik, T.; Jacobs, R. Automated Detection and Labelling of Teeth and Small Edentulous Regions on Cone-Beam Computed Tomography Using Convolutional Neural Networks. J. Dent. 2022, 122, 104139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dot, G.; Schouman, T.; Chang, S.; Rafflenbeul, F.; Kerbrat, A.; Rouch, P.; Gajny, L. Automatic 3-Dimensional Cephalometric Landmarking via Deep Learning. J. Dent. Res. 2022, 101, 1380–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhelst, P.-J.; Matthews, H.; Verstraete, L.; Van der Cruyssen, F.; Mulier, D.; Croonenborghs, T.M.; Da Costa, O.; Smeets, M.; Fieuws, S.; Shaheen, E.; et al. Automatic 3D Dense Phenotyping Provides Reliable and Accurate Shape Quantification of the Human Mandible. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 8532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kao, Z.-K.; Chiu, N.-T.; Wu, H.-T.H.; Chang, W.-C.; Wang, D.-H.; Kung, Y.-Y.; Tu, P.-C.; Lo, W.-L.; Wu, Y.-T. Classifying Temporomandibular Disorder with Artificial Intelligent Architecture Using Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2023, 51, 517–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Yang, H.; Sun, Y.; Wang, Y. Comparison Between Interactive Closest Point and Procrustes Analysis for Determining the Median Sagittal Plane of Three-Dimensional Facial Data. J. Craniofac Surg. 2016, 27, 441–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ileșan, R.R.; Beyer, M.; Kunz, C.; Thieringer, F.M. Comparison of Artificial Intelligence-Based Applications for Mandible Segmentation: From Established Platforms to In-House-Developed Software. Bioengineering 2023, 10, 604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeCun, Y.; Bengio, Y.; Hinton, G. Deep Learning. Nature 2015, 521, 436–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, J.-H.; Yeom, H.-G.; Shin, W.; Yun, J.P.; Lee, J.H.; Jeong, S.H.; Lim, H.J.; Lee, J.; Kim, B.C. Deep Learning Based Prediction of Extraction Difficulty for Mandibular Third Molars. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinayahalingam, S.; Berends, B.; Baan, F.; Moin, D.A.; van Luijn, R.; Bergé, S.; Xi, T. Deep Learning for Automated Segmentation of the Temporomandibular Joint. J. Dent. 2023, 132, 104475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjafield, A.V.; Ayas, N.T.; Eastwood, P.R.; Heinzer, R.; Ip, M.S.M.; Morrell, M.J.; Nunez, C.M.; Patel, S.R.; Penzel, T.; Pépin, J.-L.; et al. Estimation of the Global Prevalence and Burden of Obstructive Sleep Apnoea: A Literature-Based Analysis. Lancet Respir. Med. 2019, 7, 687–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowley, K.E.; Rajaratnam, S.M.W.; Shea, S.A.; Epstein, L.J.; Czeisler, C.A.; Lockley, S.W. Harvard Work Hours, Health and Safety Group Evaluation of a Single-Channel Nasal Pressure Device to Assess Obstructive Sleep Apnea Risk in Laboratory and Home Environments. J. Clin. Sleep. Med. 2013, 9, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duyan Yüksel, H.; Orhan, K.; Evlice, B.; Kaya, Ö. Evaluation of Temporomandibular Joint Disc Displacement with MRI-Based Radiomics Analysis. Dentomaxillofac. Radiol. 2025, 54, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaitanya, B.; Pai, K.M.; Chhaparwal, Y. Evaluation of the Effect of Age, Gender, and Skeletal Class on the Dimensions of Sella Turcica Using Lateral Cephalogram. Contemp. Clin. Dent. 2018, 9, 195–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanco-Míguez, A.; Beghini, F.; Cumbo, F.; McIver, L.J.; Thompson, K.N.; Zolfo, M.; Manghi, P.; Dubois, L.; Huang, K.D.; Thomas, A.M.; et al. Extending and Improving Metagenomic Taxonomic Profiling with Uncharacterized Species Using MetaPhlAn 4. Nat. Biotechnol. 2023, 41, 1633–1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trzepizur, W.; Cistulli, P.A.; Glos, M.; Vielle, B.; Sutherland, K.; Wijkstra, P.J.; Hoekema, A.; Gagnadoux, F. Health Outcomes of Continuous Positive Airway Pressure versus Mandibular Advancement Device for the Treatment of Severe Obstructive Sleep Apnea: An Individual Participant Data Meta-Analysis. Sleep 2021, 44, zsab015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katakami, K.; Shimoda, S.; Kobayashi, K.; Kawasaki, K. Histological Investigation of Osseous Changes of Mandibular Condyles with Backscattered Electron Images. Dentomaxillofac. Radiol. 2008, 37, 330–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersson, P.; Hallberg, I.R.; Renvert, S. Inter-Rater Reliability of an Oral Assessment Guide for Elderly Patients Residing in a Rehabilitation Ward. Spec. Care Dent. 2002, 22, 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aoki, T.; Kudo, M.; Endo, M.; Nakayama, Y.; Amano, A.; Naito, M.; Ota, Y. Inter-Rater Reliability of the Oral Assessment Guide for Oral Cancer Patients between Nurses and Dental Hygienists: The Difficulties in Objectively Assessing Oral Health. Support. Care Cancer 2019, 27, 1673–1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dobai, A.; Markella, Z.; Vízkelety, T.; Fouquet, C.; Rosta, A.; Barabás, J. Landmark-Based Midsagittal Plane Analysis in Patients with Facial Symmetry and Asymmetry Based on CBCT Analysis Tomography. J. Orofac. Orthop. 2018, 79, 371–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajda, P. Machine Learning for Detection and Diagnosis of Disease. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2006, 8, 537–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asnicar, F.; Thomas, A.M.; Passerini, A.; Waldron, L.; Segata, N. Machine Learning for Microbiologists. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2024, 22, 191–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le-Dong, N.-N.; Martinot, J.-B.; Coumans, N.; Cuthbert, V.; Tamisier, R.; Bailly, S.; Pépin, J.-L. Machine Learning-Based Sleep Staging in Patients with Sleep Apnea Using a Single Mandibular Movement Signal. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2021, 204, 1227–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, R.V.d.; Pinto-Monteiro, A.K.d.A.; Martins, C.C.; Granville-Garcia, A.F.; Paiva, S.M. Malocclusion and Socioeconomic Indicators in Primary Dentition. Braz. Oral. Res. 2014, 28, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iskra, T.; Stachera, B.; Możdżeń, K.; Murawska, A.; Ostrowski, P.; Bonczar, M.; Gregorczyk-Maga, I.; Walocha, J.; Koziej, M.; Wysiadecki, G.; et al. Morphology of the Sella Turcica: A Meta-Analysis Based on the Results of 18,364 Patients. Brain Sci. 2023, 13, 1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammed, F.K.; Abdullah, A.O.; Liu, Y. Morphology, Incidence of Bridging, Dimensions of Sella Turcica, and Cephalometric Standards in Three Different Racial Groups. J. Craniofac Surg. 2019, 30, 2076–2081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heimer, M.V.; Tornisiello Katz, C.R.; Rosenblatt, A. Non-Nutritive Sucking Habits, Dental Malocclusions, and Facial Morphology in Brazilian Children: A Longitudinal Study. Eur. J. Orthod. 2008, 30, 580–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, C.R.T.; Rosenblatt, A.; Gondim, P.P.C. Nonnutritive Sucking Habits in Brazilian Children: Effects on Deciduous Dentition and Relationship with Facial Morphology. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2004, 126, 53–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lévy, P.; Kohler, M.; McNicholas, W.T.; Barbé, F.; McEvoy, R.D.; Somers, V.K.; Lavie, L.; Pépin, J.-L. Obstructive Sleep Apnoea Syndrome. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2015, 1, 15015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mongan, J.; Halabi, S.S. On the Centrality of Data: Data Resources in Radiologic Artificial Intelligence. Radiol. Artif. Intell. 2023, 5, e230231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindqvist, L.; Seleskog, B.; Wårdh, I.; von Bültzingslöwen, I. Oral Care Perspectives of Professionals in Nursing Homes for the Elderly. Int. J. Dent. Hyg. 2013, 11, 298–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koistinen, S.; Olai, L.; Ståhlnacke, K.; Fält, A.; Ehrenberg, A. Oral Health-Related Quality of Life and Associated Factors among Older People in Short-Term Care. Int. J. Dent. Hyg. 2020, 18, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoneyama, T.; Hashimoto, K.; Fukuda, H.; Ishida, M.; Arai, H.; Sekizawa, K.; Yamaya, M.; Sasaki, H. Oral Hygiene Reduces Respiratory Infections in Elderly Bed-Bound Nursing Home Patients. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 1996, 22, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Yang, J.; Liu, H.; Yu, P.; Jiang, X.; Liu, R. Co-Mask R-CNN: Collaborative Learning-Based Method for Tooth Instance Segmentation. J. Clin. Pediatr. Dent. 2024, 48, 161–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascadopoli, M.; Zampetti, P.; Nardi, M.G.; Pellegrini, M.; Scribante, A. Smartphone Applications in Dentistry: A Scoping Review. Dent. J. 2023, 11, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, K.-H.; Beam, A.L.; Kohane, I.S. Artificial Intelligence in Healthcare. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2018, 2, 719–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carra, M.C.; Gueguen, A.; Thomas, F.; Pannier, B.; Caligiuri, G.; Steg, P.G.; Zins, M.; Bouchard, P. Self-Report Assessment of Severe Periodontitis: Periodontal Screening Score Development. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2018, 45, 818–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, F.A.; Pike, F.; Alvarez, K.; Angus, D.; Newman, A.B.; Lopez, O.; Tate, J.; Kapur, V.; Wilsdon, A.; Krishnan, J.A.; et al. Bidirectional Relationship between Cognitive Function and Pneumonia. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2013, 188, 586–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rollman, G.B.; Gillespie, J.M. The Role of Psychosocial Factors in Temporomandibular Disorders. Curr. Rev. Pain. 2000, 4, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).