Abstract

Groundwater models form the basis for investigating subsurface processes that relate to groundwater flow. Urban cover, however, usually inhibits the collection of new subsurface or geological data. Therefore, models usually depend on existing, poor-quality, or scarce datasets. The geological domain is an integral part of any groundwater model, and as such, understanding the model’s sensitivity to the geological interpretation is key to constraining uncertainty. This research uses a recent advancement in mitigating uncertainty in geological modeling to investigate how different geological interpretations affect groundwater model uncertainty. Using the Ouseburn catchment, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, as a case study, it estimates baseflows and uses them to develop an ensemble of coupled distributed groundwater recharge and groundwater flow models using SWAc and MODFLOW, and performs a Monte Carlo analysis on the different model formulations. Results indicate that even though river baseflows are not highly affected, there is a connection between simulated groundwater level sensitivity and areas of high geological uncertainty. As the interest in the urban subsurface grows, constraining uncertainty in groundwater models is especially important for urban planning, policy making, water resources, and groundwater flooding protection. Therefore, constraining uncertainty from geological datasets is key to robust groundwater modeling.

1. Introduction

Groundwater models are crucial tools for resource management and understanding subsurface processes related to groundwater flow, especially since the subsurface is hidden and field measurements are often scarce [1]. These models are generally divided into two main categories: physical models, which are built in laboratory settings using tanks or columns filled with porous materials to directly measure hydraulic heads and flows, and mathematical models, which describe groundwater behavior through mathematical equations, such as partial differential equations or linear algebraic equations [2]. Mathematical models can be further divided into various types, including stochastic, deterministic, analytical, and numerical models. Numerical models, in particular, have become the preferred method to simulate complex groundwater systems due to their ability to simulate such systems with high precision [3]. These models typically employ Finite Differences or Finite Elements to approximate the solutions of partial differential equations at specific spatial and temporal points, making them more versatile and able to simulate complex groundwater systems in more detail.

Groundwater models, however, are an approximation of a complex natural system [2,4]. Uncertainties are therefore an integral part of a groundwater model and are caused by differences between the physical system and its mathematical approximation (i.e., the model). These uncertainties can be quite significant and affect how the model can be used to support policy or scientific inquiry [5]. Robust modeling usually depends on a good-quality input dataset and a strong conceptual understanding of the subsurface hydrogeological processes and interactions with the surface water features [6].

Within urban areas, groundwater models are also an important tool in supporting subsurface and hydrogeological investigations. The increase in urbanization has led to a set of environmental challenges in the urban subsurface [7,8,9]. As a result, there is increased focus on the urban subsurface space [10,11], especially in terms of urban groundwater flooding [12,13]. The concentration of human activities within urban areas means that groundwater flooding can cause significant social and economic damages, as well as public health implications [14,15].

Urban infrastructure at risk of groundwater flooding may include cellars, basements, underground transportation tunnels and stations, etc. [12,16]. However, an often-overlooked example of subsurface infrastructure is the sewer network. In places where the network lies below or close to the water table, groundwater infiltration can occur through cracks, joints, and other defects, and thus increase the sewer hydraulic loading. It is estimated that groundwater infiltration can account for between 30% and 72% of sewer discharge globally [17]. Furthermore, this increased hydraulic loading is particularly problematic in areas with combined sewer networks. Combined sewers are an important component of the urban flood defense infrastructure; however, they may be unable to operate properly and discharge the flood volumes they were designed to, due to the aforementioned increased hydraulic loading. This results in increased risk of untreated sewer overflows into the surrounding surface water bodies [18], resulting in reduced water quality, environmental, and public health impacts.

Moreover, there is growing interest in Blue–Green Infrastructure for surface runoff management within urban areas. However, these solutions may lead to increased groundwater recharge due to increased infiltration, and thus excessive water table rising [19]. Areas of shallow groundwater already prone to groundwater flooding can therefore be negatively impacted [20]. Ultimately, groundwater flooding can be described as part of a wider water management problem. Modeling is usually the tool used to evaluate the effects of groundwater flooding and, therefore, is key to understanding the risks that groundwater flooding poses to flood resilience.

However, robust groundwater modeling in urban areas is inhibited by numerous factors. One of these factors is the estimation of groundwater fluxes, which is an inherently difficult process and is further complicated due to the complexity of the urban environment [21]. Furthermore, there is a general lack of appropriate groundwater and subsurface data in urban areas, which further increases the uncertainty of groundwater models and poses a significant challenge to the calibration and validation process. This data scarcity can be attributed to the fact that urban groundwater has been traditionally overlooked, often considered polluted, and thus seen simply as a nuisance [22]. Furthermore, the inherent complexity of the built environment and the concentration of human activities further inhibit the collection of appropriate subsurface data.

This data-scarcity problem further extends to the geological information used for the subsurface characterization. The lack of readily available subsurface information can therefore increase model uncertainty. Furthermore, existing geological data were usually collected prior to urban development, due to the urban cover prohibiting new geological investigations [23], or during infrastructure projects. Urban development, however, tends to alter the near-surface geology, and historical records tend to be lacking in both the accuracy and detail they provide [11]. Furthermore, infrastructure is constructed during different time periods and thus, geological data obtained during the relevant site investigations can contain different information and accuracy depending on when and how they were collected [24]. As such, urban geological datasets tend to be highly uncertain and often contain records that conflict with each other [25]. These highly uncertain datasets can therefore increase uncertainty due to the geological information supporting multiple model structures. The various model structures supported by the same input data are an often-neglected element of model uncertainty [26,27] that can have a significant influence on model results [28,29].

Several approaches exist to mitigate data uncertainty in the geological model, and more specifically, uncertainty originating from clusters of geological data with conflicting information. Examples include deep learning algorithms [30,31,32,33,34], probabilistically tuning the model parameters [35], including expert knowledge as the modeling objective [36], dynamically updating the model structure as new data become available [37], as well as locally smoothing the geological interpolator depending on data quality [38].

Another recent advancement in this area is the orientation estimation and random point selection technique [24]. This method relies on the ability of kriging-based geological modeling approaches to combine multiple types of data. To that end, geological information at the locations of data clusters is converted into a different data format for the geological interpolation. Compared to other methods for dealing with geological uncertainty originating from clusters of uncertain geological data, the orientation estimation and random point selection technique is shown to provide improved performance in geological model validation, and thus model precision [24]. However, this technique has to date only been used for geological model development. Geological models usually form the basis for other scientific inquiries [39]. There is therefore a need to evaluate how the orientation estimation and random point selection technique can be used to support a hydrogeological investigation.

It is important to note that the geological setting of an area constitutes the medium through which groundwater flow occurs. Traditionally, groundwater model calibration focuses on the hydrogeological properties of the aquifer, i.e., the properties that facilitate groundwater flow. This involves the parameterization or vertical discretization of the model. Investigating the model uncertainty originating from the hydrogeological properties is an active area of research. Various methods have previously been used to optimize the parameterization and vertical discretization of groundwater models.

Usual methods involve the use of different parameterization approaches, depending on different degrees of model complexity. Ghasemizade et al. (2015) [40] used three different parameterization schemes for the shallow unsaturated zone and evaluated model performance in simulating evapotranspiration, water content, and discharge rates. Similarly, White et al. (2017) [41] investigated the importance of parameterization in simulating the effects of land use changes, using two different models: (i) a simplified model with 12 adjustable parameters, and (ii) a fully parameterized model with 1305 adjustable parameters. Cui et al. (2021) [42] used two different parameterization approaches to evaluate the effects of coal seam gas extraction on the groundwater system through a large-scale regional model.

Statistical or deep learning approaches have also been previously employed to investigate the role of parameterization in model performance. Schöniger et al. (2015) [43] used Bayesian inference to identify an optimal balance between model complexity and data availability by examining four different methods for spatially parameterizing hydraulic conductivity values. Knowling et al. (2019) [44] also employed a Bayesian framework to evaluate how different degrees of complexity in terms of parameterization affect the model’s suitability to be used for resource management and decision making. Similarly, White et al. (2020) [45] focused on the role of the vertical discretization and used a Bayesian framework to evaluate the model’s suitability in supporting decision making. Yin et al. (2021) [46] used a Bayesian multi-model uncertainty quantification framework to investigate the effects of parameter uncertainty in alluvial modeling and improve model reliability. Finally, Kawo et al. (2024) [47] adopted a machine learning approach to characterize the 3D distribution of hydraulic parameters in glacial aquifers.

For urban models, the altering of the near-surface geology by human activities can significantly influence the hydraulic properties of the geological material. Previous studies have shown that human activities can result in the formation of conduits for groundwater flow [48,49] or flow barriers [50,51]. As such, previous research has focused on the effects that urbanization has on model parameterization and how urban infrastructure can promote or inhibit groundwater flow. Attard et al. (2017) [52] investigated how the changes in the material’s hydraulic properties affect the mixing between shallow and deep groundwater. Berthier et al. (2004) [53] used a 2D model to determine the influence of soil parameters on urban runoff and water table fluctuations. Boukhemacha et al. (2015) [54] focused on the interactions between the groundwater and urban infrastructure, primarily the sewer network, for the case study of Bucharest, Romania. Similarly, Epting et al. (2008) [55] focused on interactions between urban groundwater and transportation tunnels in Basel, Switzerland.

However, in the examples mentioned earlier, the structure and shape of the geological domain are usually considered to be something predefined and therefore static. The focus in these examples is instead on the selection of appropriate parameter values, the distribution of those values within the 3D domain, and the interactions between different features of the model. However, the uncertainty in geological information is shown to lead to different interpretations of the data and thus different realizations of the geological domain [24]. Therefore, the definition and characterization of the geological domain contain uncertainty, which then propagates to the groundwater model. The effects of that uncertainty are not yet fully understood. Therefore, when it comes to investigating groundwater flooding in an urban environment, evaluating the effects of the subsurface characterization on model performance can be key to constraining model uncertainty.

Thus, there is a need to investigate how the uncertainty in the geological data used to formulate the geological model affects the performance of the groundwater model. To that end, this research aims to evaluate groundwater model sensitivity to geological information and subsurface characterization. Although several approaches exist for evaluating geological uncertainty, it is not yet fully understood how it propagates to hydrogeological investigations. This research uses a recent advancement in mitigating geological uncertainty to evaluate how it affects an urban groundwater model, by examining the case study of the Ouseburn catchment in the wider Newcastle upon Tyne (UK) area. The objectives of this research are therefore to: (i) develop an ensemble of superficial thickness models for the study area; (ii) use the orientation estimation and random point selection technique [24] to mitigate the uncertainty in the superficial thickness models due to clusters of poor-quality geological data; (iii) develop a distributed groundwater recharge model for the study area using the Surface Water Accounting Model (SWAc v2.0.1) [56]; (iv) develop a groundwater flow model of the study area using MODFLOW 6 (v6.6.2) [57]; (v) evaluate the effects of geological uncertainty on the groundwater model results, both in terms of model calibration and model validation, through a Monte Carlo analysis.

2. Conceptualization and Available Data

Development of the conceptual model was primarily driven by the availability of relevant data. The main limitation was the lack of available subsurface information, and especially the lack of groundwater level observations within the study area. As such, the main objective of the conceptual (and the subsequent numerical) model was to develop a model that was simple enough to fit the available data but still provided enough detail to investigate the research aims and objectives. It should also be noted that poor data availability is not unique to this case study, and it is a problem commonly faced by modelers around the world.

2.1. Location of the Study Area

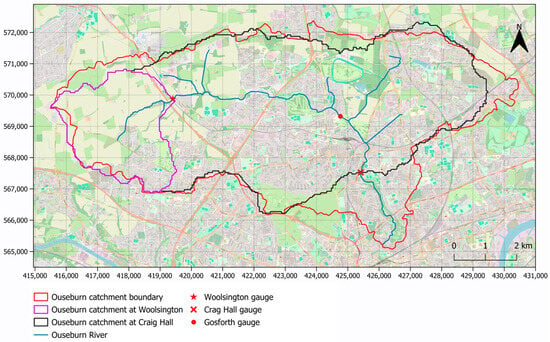

The Ouseburn catchment is a peri-urban catchment, located in the wider Newcastle upon Tyne area, in the North-East of England. The catchment covers an area of approximately 61.6 km2, and its location is presented in Figure 1. Further information about the study area is provided in the following Sections.

Figure 1.

Location of the Ouseburn catchment (contains: Map data from OpenStreetMap; OS data © Crown copyright 2025; EA data © Crown copyright 2025; coordinates in EPSG:27700).

2.2. Catchment Boundaries

Catchment boundaries for the Ouseburn were obtained from the Environment Agency (EA) [58], as well as the National River Flow Archive (NRFA). Two gauges are located along the Ouseburn River, at Woolsington (station ID: 023018) and Crag Hall (station ID: 023016), respectively, which provide daily streamflow and river water level data, and divide the catchment into two sub-catchments. A third gauge at the Gosforth Golf Club (station ID: 023054) only provides water level data, and no catchment boundaries are available. The location of the gauges and the respective catchment boundaries are presented in Figure 2. The catchment boundary provided by the EA and the sub-catchment boundaries provided by the NRFA do not entirely overlap. However, this discrepancy is considered insignificant for this research. Furthermore, the catchment provided by the EA has a different outlet; it extends further south, up to the point where the Ouseburn River enters a culvert. Thus, it encompasses a larger area of the catchment. Finally, the EA catchment offers better local details at the catchment boundary.

Figure 2.

Ouseburn catchment and sub-catchment boundaries, including the location of the streamflow and river water level gauges. Catchment boundaries at Woolsington and Crag Hall obtained from the NRFA, and Ouseburn catchment boundaries from the EA (contains: Map data from OpenStreetMap; OS data © Crown copyright 2025; EA data © Crown copyright 2025; Data from the UK National River Flow Archive; coordinates in EPSG:27700).

2.3. Model Domain

The model domain was selected to be the Ouseburn catchment, as defined by the catchment boundaries provided by the EA [58]. In terms of the 3D extent, this was defined to encompass a satisfactory bedrock thickness, the model top was selected to be the ground surface, and the model bottom was set to −15 mAOD (meters Above Ordnance Datum).

2.4. Topography

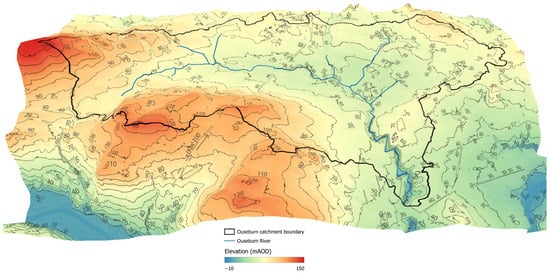

The Ouseburn catchment is characterized by gentle slopes [59]. The higher part of the catchment is in the north and west, and it follows a gentle “urbanization gradient”. The western (upstream) part of the catchment is primarily rural and used for agricultural purposes (arable land and grassland) and gradually becomes more urbanized in its eastern and southern (downstream) parts. Figure 3 shows the ground surface elevation within the Ouseburn catchment.

Figure 3.

Ground surface elevation (in mAOD) for the Ouseburn catchment (contains: OS data © Crown copyright 2025; EA data © Crown copyright 2025).

The topography was extracted using the LIDAR Composite Digital Terrain Model (DTM) with 1 m resolution [60]. The DTM was resampled to 25 × 25 m to match both the groundwater and superficial thickness model resolution. It was then used to constrain the ground surface elevation within the model.

2.5. Surface Water Features

The primary surface water feature within the area is the Ouseburn River and its tributaries. As mentioned earlier, two streamflow gauges are located along the Ouseburn River. These gauges provide daily streamflow data, available from the EA and the NRFA. More specifically, the streamflow record available for the gauge at Woolsington is for the period of 19 October 1983–30 September 2023, while for the gauge at Crag Hall, the available data period is 1 March 1975–30 September 2023. However, these records are not continuous and contain significant gaps. Finally, the river network was obtained from the OS VectorMap [61] Open Rivers layer, which was then clipped to the catchment boundary. Discontinuities were then manually adjusted to produce a continuous river network.

Stormwater detention ponds have been constructed within the catchment. These are along the central part of the Ouseburn River, near the Newcastle Great Park residential and commercial development [59], as well as the eastern part of the catchment, in the Killingworth and Longbenton areas [62]. These were designed to reduce the risk of downstream flooding and improve water quality; however, they are shown to have minimal connection to the groundwater within the area [59]. Furthermore, the baseflow index (BFI) for the catchment at Crag Hall from the CAMELS-GB database [63] is 0.39, which indicates a catchment that is dominated by surface runoff. As a result, for this research, the stormwater detention ponds were assumed not have a significant role in the hydrogeological conditions of the area. Finally, given their relatively small size compared to the grid resolution, including these features within the groundwater flow model would add increased complexity compared to the added detail they would provide.

2.6. Land Use

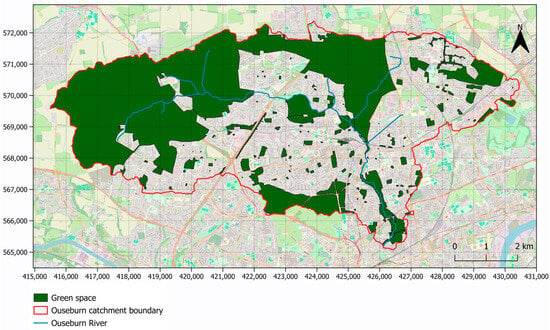

Land use data for the study area were obtained from the Ordnance Survey (OS) VectorMap [61]. More specifically, given the differences in the hydrological regime caused by urbanization, the study area was divided into two zones: (i) urban areas, and (ii) green spaces. The extent of urban zones was retrieved from the OS VectorMap Urban Extent layer. The remaining area within the catchment was then categorized as green spaces, the extent of which is presented in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Green space extent within the Ouseburn catchment (contains: Map data from OpenStreetMap; OS data © Crown copyright 2025; EA data © Crown copyright 2025; coordinates in EPSG:27700).

2.7. Climatic Data

Climatic data are available from the CAMELS-GB database [63]. For the study area, climatic data are only available for the sub-catchment at Crag Hall (ID: 023016), and the rainfall and potential evapotranspiration timeseries available are for the period of 1 October 1970–30 September 2015. Therefore, given that the sub-catchment at Crag Hall covers a significant part of the overall catchment, it was assumed that the data provided for the sub-catchment at Crag Hall are representative of the conditions across the whole of the Ouseburn catchment.

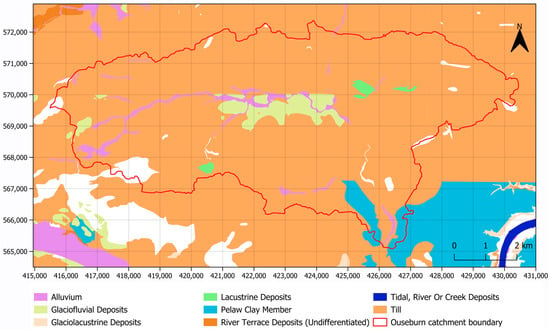

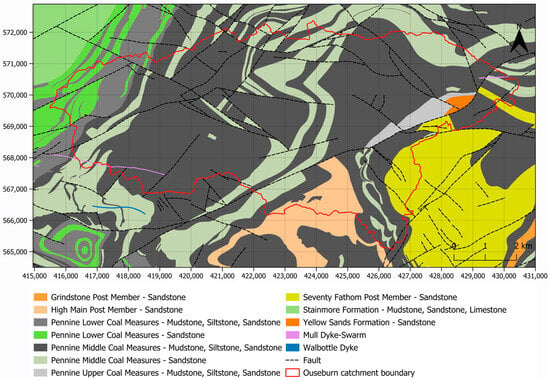

2.8. Geological Data

A detailed review of the geological setting for the study area, as well as the available geological information, is presented by Ntigkakis et al., 2025 [24]. Briefly, the bedrock across the study area is covered by superficial deposits, which primarily comprise glacial till, made ground/urban fill, as well as alluvium and glaciofluvial deposits (Figure 5). The bedrock, on the other hand, comprises fractured coal measures, which consist of a sequence of mudstones, sandstones, siltstones, and shales, as well as coal seams and seatearths (Figure 6).

Figure 5.

Map of the superficial deposits within the study area. Gaps represent areas with no superficial cover (contains EA data © Crown copyright 2025; BGS materials © UKRI 2025; coordinates in EPSG:27700).

Figure 6.

Map of the bedrock within the study area (contains: EA data © Crown copyright 2025; BGS materials © UKRI 2025; coordinates in EPSG:27700).

Geological borehole records for the study area are available from the British Geological Survey’s (BGS) GeoIndex [64]. There are 7620 borehole records within the study area, collected over a period spanning multiple decades. Shallower records (less than 10 m) were primarily collected during site investigations, and deeper ones to support historic mining activities. However, these records are of poor quality, not readily available, and spatially and temporally variable. More specifically, they are in the form of scanned physical documents and not in a digital format, thus requiring extensive preprocessing prior to use. Furthermore, due to these records being collected over different periods, they might represent the geological domain at different points in time, i.e., prior to certain infrastructure developments, and thus contradict each other. Several other inconsistences have been observed within the records, including the use of different units, the omission of coordinates, the rounding of values, and others. A more detailed overview of the available geological data is presented by Ntigkakis et al., 2025 [24].

2.9. Hydrogeology

Little information is available regarding the hydrogeology of the study area, and no aquifer test data are available for the area [65]. As such, combined with the complexity of the geological setting within the area, the assumption made for this research was to consider two homogeneous layers for the groundwater flow model, representing the superficial deposits and the bedrock, respectively. Therefore, the aquifer property values selected for each layer would account for the different properties of each material, as well as other variables that cannot be represented. Furthermore, given the knowledge about the geological domain, it was assumed that the superficial cover extends to the entirety of the model domain. Therefore, the bedrock was considered confined across the model area.

The fault lines within the bedrock also affect the hydrogeology and can either act as a conduit for groundwater flow or a partial flow barrier. There is evidence to suggest that part of the groundwater flow within the bedrock occurs through the faults and fractures [66]. However, little information is available regarding the geometry of the fault lines, and therefore, they cannot be easily represented within the groundwater model. As a result, the assumption was made not include the fault lines within the model and account for the effects they have on the groundwater flow through the selection of appropriate hydraulic conductivity values.

Abandoned coal mines are also present within the study area. These are shown to interact with the groundwater and be part of a wider network of interconnected channels throughout the wider area. However, little information is known about their geometry, location, and the flows within them. They are therefore a significant boundary condition that affects the water budget; however, the feasibility of accurately modeling these features was low given the lack of information. As such, they were omitted from the model.

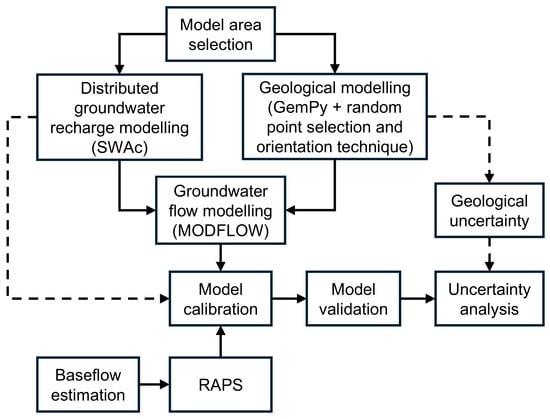

3. Methods

Figure 7 shows a graphical representation of the analysis presented within this section:

Figure 7.

Flow chart showing the steps of the analysis.

3.1. Geological Modeling

The geological model of the study area was developed using GemPy (v2.3.1) [67] and the orientation estimation and random point selection technique [24]. A detailed description of the geological modeling process is presented in Ntigkakis et al., 2025 [24]. Briefly, due to the data quality issues discussed in Section 2.8, as well as the need for borehole records to be deep enough to penetrate the bedrock, 210 borehole records were used for the development of the superficial thickness model. Geological orientations were inferred from the contact points recorded within the borehole logs by applying the orientation estimation and random point selection technique. The model was then validated against the unused borehole records, as well as the superficial deposits map (Figure 5).

3.2. MODFLOW with FloPy

MODFLOW is a modular 3D groundwater flow model developed by the US Geological Survey (USGS) [68]. It is a physically based model that uses the Finite Differences method to solve the partial differential equations of groundwater flow [69]. It uses a gridded spatial discretization approach, defined by 3D cells, to represent processes and hydrogeological properties within the model domain, under both steady state and transient conditions [68,70].

The extensive adoption of MODFLOW for groundwater modeling applications [71] has led to the development of several accompanying software packages, both commercially licensed and open source. FloPy (v3.8.1) [72] presents a script-based approach for setting up, running, and postprocessing MODFLOW-based groundwater flow and groundwater transport models. FloPy is an open source Python (v3.13.11) package and has been continuously developed and adopted since its initial introduction [73]. The use of the Python language allows FloPy-based models to be easily reproducible [72]. It also enables the modeler to tweak the core functionality and modular design of MODFLOW to develop new workflows and methods, as well as easily couple MODFLOW to other modeling frameworks. Examples include coupling MODFLOW to other hydrogeological models [74], as well as agent-based models for social–ecological modeling [75].

For this research, MODFLOW 6 [57] and FloPy [72] were used for the development of the hydrogeological model, as well as for preprocessing and postprocessing model inputs and outputs. The modeling process was split into two MODFLOW 6 simulations, each containing a single groundwater flow model, for the steady state and transient conditions, respectively. The resulting groundwater head from the steady state model was used as the initial conditions for the transient model. This workflow was chosen due to the limitation of SWAc (see Section 3.3) lacking the option to distinguish between transient and steady state conditions.

For the temporal discretization, MODFLOW uses stress periods and time steps. Stress periods are defined as periods during which all external stress (e.g., recharge, evapotranspiration, etc.) is constant, which can then be further divided into time steps. Urban environments are highly complex and dynamic, especially near the ground surface. Therefore, having a fine temporal discretization is key to simulating the near-surface water table fluctuations. As such, a daily discretization was selected, i.e., daily stress periods comprising a single time step.

The spatial discretization of the model domain was represented by a rectilinear (regular) grid of 25 × 25 m resolution. Furthermore, the model domain was split into two layers for the vertical dimension: (i) superficial deposits, and (ii) bedrock. Moreover, as discussed earlier, the assumption was made that the bedrock is confined throughout the model domain, and therefore, a minimum superficial thickness of 2 m was established. The minimum thickness selected represents the average thickness of the urban coverage, topsoil, and fill material across the model domain.

For the hydraulic properties, each layer was considered to be homogeneous. Therefore, the values selected for the hydraulic conductivities were assumed to account for the different properties of the geological materials within each layer, as well as the potential effects of fault lines or other unknown features. Furthermore, due to the depositional environment for both the superficial deposits and the bedrock, horizontal layers of impermeable or semipermeable material (e.g., clay, shale, mudstone, etc.) can be assumed for both the superficial deposits and the bedrock across the model domain (see Mills and Holliday, 1998, [66] for a more detailed overview of the geology within the study area). Therefore, anisotropic conditions were assumed for both layers, i.e., the vertical hydraulic conductivities were considered lower than the horizontal.

Finally, the river network was represented using the Streamflow Routing (SFR) package. Even though the SFR package can estimate total streamflow, the surface runoff component was removed, and the simulated streamflow only represented baseflow within the river. Given the lack of groundwater level observations, the simulated streamflow from SFR is the only metric available for model calibration. However, because the catchment is dominated by surface runoff (BFI = 0.39) [63], including surface flows within the analysis risked introducing bias towards the surface water component during calibration.

3.3. Recharge Estimation—SWAc

MODFLOW is primarily a saturated flow model, although flow in the unsaturated zone can be simulated through the Unsaturated Zone Flow (UZF) package [76]. Depending on the application and available data, however, a more detailed representation of the processes that occur within the unsaturated zone or on the ground surface may be needed. Due to its modularity, MODFLOW can therefore easily be coupled with other modeling frameworks to better suit the specific modeling application. Examples of that include the integration with the Soil and Water Assessment Tool (SWAT) [77] for coupled surface water and groundwater modeling. See Ke (2014) [70], Guzman et al. (2015) [69], Aliyari et al. (2019) [78], Sith et al. (2019) [79], Gelsinari et al. (2020) [80], Jafari et al. (2021) [81], Wang and Chen (2021) [82] for example applications of coupling MODFLOW with other frameworks.

For this research, MODFLOW was coupled with the Surface Water Accounting Model (SWAc) [56] for the simulation of the unsaturated zone. SWAc uses a 1D sequential workflow that tracks the water from the ground surface, through the soil zone and the unsaturated zone, to estimate the effective recharge, i.e., recharge that reaches the water table [56]. It follows a modular design, which means that processes can be enabled or disabled depending on the site being modeled. Furthermore, SWAc is not dependent on the spatial grid used within MODFLOW, and the 1D workflow is applied on a per-cell basis. As such, it allows for the simulation of spatially variable hydrological processes, given a set of spatially distributed properties and time variable climatic data.

Therefore, two spatial zones were selected for the recharge model: (i) urban areas, and (ii) green spaces. The spatial extent of these zones is shown in Figure 4. This followed the assumption that the green spaces within the model domain all have the same characteristics, and therefore are all described by the same hydrological processes and properties. This essentially assumed that there is the same vegetation type across the entirety of green spaces (namely, grass), as well as the same soil type, which followed the assumption that the superficial deposits can be represented as a uniform material.

As such, for the green spaces, the main processes of SWAc used were rapid runoff estimation, soil moisture accounting, and actual evapotranspiration estimation. Rapid runoff estimation was based on daily rainfall intensity and antecedent moisture conditions. As discussed earlier, however, surface runoff was removed from the model, and only the baseflow component of streamflow was considered. As such, the runoff estimated by SWAc was removed from the water balance and not allowed to infiltrate downstream. Soil moisture accounting and actual evapotranspiration estimation, on the other hand, were performed using the FAO-56 method [83]. This followed the assumption that, given the low vegetation in the area, canopy interception is not a significant process. Another assumption is that the infiltrating water percolates downwards through the root zone and into the unsaturated zone. Therefore, there is no lateral movement of water towards surface water bodies between the root and the unsaturated zones.

For the urban areas, however, the processes of the unsaturated zone could not be simulated due to the lack of available information. Therefore, recharge for these areas was represented by a single recharge component applied directly beneath the root zone, bypassing the soil moisture accounting mechanism. Conceptually, this meant that this recharge component represented the combined effective recharge from all the processes and recharge sources within the urban areas that reached the water table.

3.4. Baseflow Estimation

Urbanization is shown to have a varying effect on baseflow [84]. Various studies have examined the effect that urbanization has on baseflow, as a means to examine its effects on groundwater recharge, and found both increases and decreases in baseflow due to urbanization [85]. Unlike surface runoff, which tends to become more responsive due to urbanization, determining the effects of urbanization on baseflow is more complicated and can include sources such as wastewater management infrastructure (piped network and/or septic tanks), stormwater management ponds, etc. [86,87].

Methods for estimating the baseflow component of the streamflow can generally be grouped into two categories: (i) hydrograph separation methods, and (ii) tracer mass balance methods [88]. Given their data requirements, tracer methods are harder to apply compared to hydrograph separation methods, which depend on identifying trends within the hydrograph [89]. This is especially true in urban environments, where there is a general scarcity of available subsurface data compared to streamflow measurements. As such, this research focused on hydrograph separation methods and, more specifically, digital filter methods.

Three different methods were used: (i) the one-parameter Recursive Digital Filter (RDF) [90,91], (ii) the United Kingdom Institute of Hydrology (UKIH) method [92], and (iii) the Eckhardt method [93]. These methods were applied to the observed streamflow data from the two gauges at Woolsington and Crag Hall. Periods of missing data of less than 7 days were infilled using a 3rd order spline interpolation. It should be noted that although longer gaps could also be filled, this risks introducing bias towards the inferred values. More specifically, the estimated baseflows were used for model calibration, and inferring longer periods of data could potentially skew the calibration towards the method used to fill in the data, rather than the actual data. Following that, only time periods longer than 365 days were selected for further analysis. This is to ensure a long enough record to capture both a high-flow and a low-flow season. The resulting time series subsets with periods of continuous data were treated as independent records, i.e., the baseflow separation algorithms were applied independently to each subset. The final baseflow timeseries was obtained as the average of the estimations from the three different methods and was considered to be the “observed” baseflow for this research.

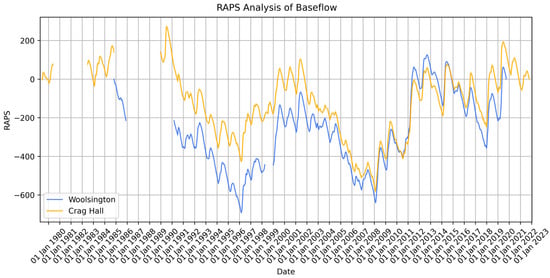

3.5. Timeseries Analysis—Rescaled Adjusted Partial Sums (RAPS)

The Rescaled Adjusted Partial Sums (RAPS) method is widely used in hydrology for timeseries analysis. RAPS is based on cumulative standardized deviations from the mean [94]. The graphical representation of RAPS is commonly used to analyze hidden trends within the timeseries [95]. More specifically, increasing trends in RAPS values indicate periods of above-average values, and similarly decreasing trends indicate periods of below-average values [96]. Within this study, RAPS was applied to the baseflow timeseries to identify any hidden patterns and guide the selection of an appropriate calibration period.

3.6. Model Calibration

Calibration of the model was performed manually, using the trial-and-error method. The calibration period was selected between 1 June 2000 and 1 September 2010, using a daily temporal discretization. The selection of the calibration period was influenced by data availability, especially in terms of river flow measurements (and thus baseflow estimations). More specifically, although longer records are available, the time series prior to the year 2000 contains significant gaps. Although gaps in the records can still be observed from 2000 onwards, these are significantly shorter (less than 1 month long) and do not overlap for the two gauges. Therefore, ensuring that there is at least one measurement of flow at any given time. Another restriction was with regards to the computational requirements. As discussed previously, the spatial discretization selected was 25 × 25 m, and the temporal discretization was set to daily stress periods. As a result, a 10-year-long simulation of the coupled distributed groundwater recharge and groundwater flow model required approximately 85 GB of system memory and 140 GB of disk space.

Furthermore, the initial 90 days were considered to be the spin-up period and removed from further analysis. This was to avoid the potential influences of the selected initial conditions. As discussed earlier, however, no groundwater level observations are available for the study area. As such, the target of the calibration was the observed baseflow at the two gauge locations at Woolsington and Crag Hall. The goodness of fit indicator used for the model calibration was the Kling-Gupta efficiency (KGE) [97] (which is widely used in hydrology), where , with KGE = 1 meaning perfect showing perfect fit between observed and simulated data. The final parameter values following model calibration are presented in Appendix A.

Automatic calibration using PEST++ (v5.2.7) [98] and pyEMU (v1.3.8) [99] was also considered. More specifically, both groundwater levels and groundwater fluxes are required to adequately constrain the inverse problem of calibration [2]. However, only flux observations were available for the study area in the form of baseflow, meaning that the PEST++ analysis did not provide meaningful results.

The lack of groundwater level observations for the study area also means that the model cannot be fully calibrated in terms of both hydraulic conductivities and recharge rates (and the parameters that influence them) [100]. Instead, only the ratio of the two can be estimated, and therefore, only their relative relation can be captured. As such, the aim of the calibration was not to produce a fully calibrated, predictive model, but rather to identify patterns in the model outputs.

3.7. Model Validation

Model validation was performed for the period between 1 June 2010 and 1 September 2013, using a daily temporal discretization. Similar to the calibration process, the initial 90 days were removed from further analysis to avoid the influence of the initial conditions.

3.8. Uncertainty Analysis

To evaluate the effects of the geological uncertainty on both the calibration and validation of the hydrogeological model, a Monte Carlo analysis was employed. During the Monte Carlo analysis, a different geological interpretation was selected for the groundwater model layer definition, resulting in different model formulations. These geological interpretations were obtained by selecting each coordinate of the geological points at random from a range of ±1 m from the recorded value within the geological borehole records. A more detailed description of how those geological interpretations were obtained is presented in Ntigkakis et al. (2025) [24].

4. Results

Evaluating model performance in terms of groundwater level simulations presents a four-dimensional problem: (i) easting, (ii) northing, (iii) groundwater level, and (iv) time. However, due to the nature of this publication (i.e., text-based printed format), only three-dimensional problems can effectively be communicated (e.g., via figures). To that end, for effectively communicating the results of this research in terms of simulated groundwater levels, the “flooding frequency” was estimated. More specifically, groundwater flooding was defined as having occurred when the simulated groundwater levels were above the ground surface. The frequency of such events was then estimated for the whole simulation period. It should be noted that despite the similarities, this does not represent a flood frequency analysis, which is an evaluation of flood risk (i.e., the product of probability and impact of an event). Instead, the flooding frequency estimated for this research is only intended to visualize a four-dimensional problem in a three-dimensional format.

4.1. Timeseries Analysis

The RAPS analysis on the baseflow timeseries at the two gauging stations are presented in Figure 8. The plot highlights that the records at both locations follow the same trends, indicating consistency between both locations. Furthermore, the RAPS analysis indicated that the selected calibration period contained both an above-average (wet) and a below-average (dry) period. Lastly, gaps within the plot indicate missing values within the baseflow timeseries, as discussed in Section 3.4.

Figure 8.

RAPS analysis of estimated baseflow for the gauging stations at Woolsington and Crag Hall. Gaps within the graph represent gaps in the original data.

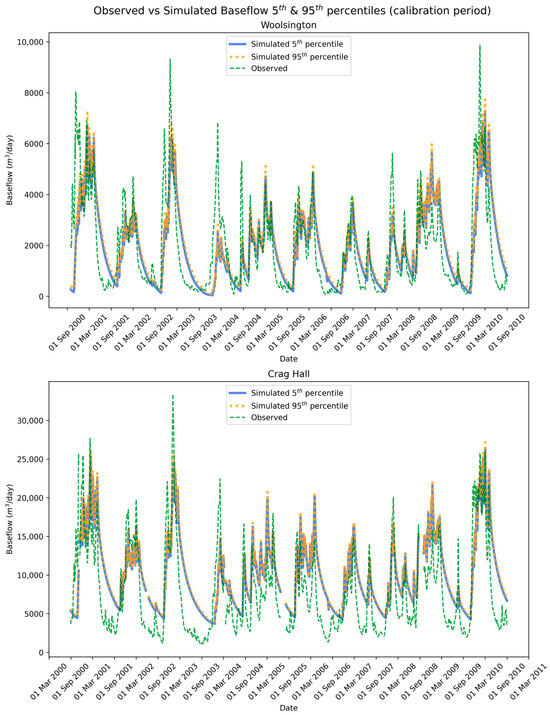

4.2. Calibration Period

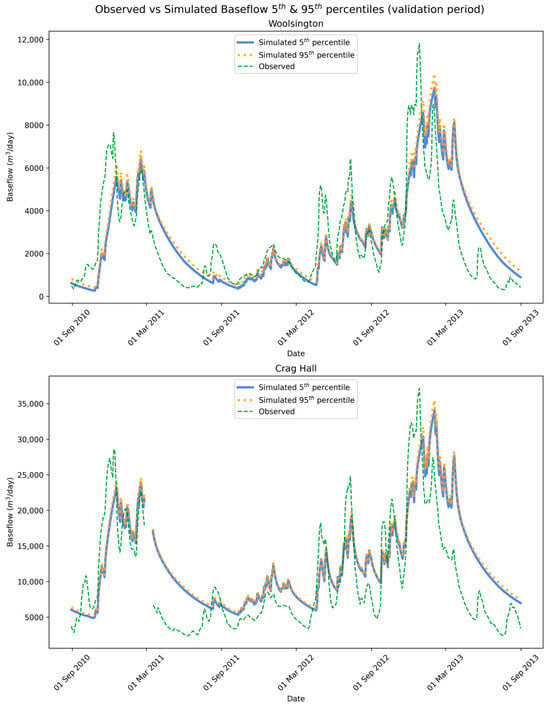

Figure 9 shows the simulated baseflow at the two gauging stations, for the 5th and 95th percentiles of the Monte Carlo analysis, for the model calibration period. The simulated baseflow at both gauging stations showed minimal variability, with the confidence interval between the two percentiles being significantly small. This indicated little variability between the different model formulations of the Monte Carlo analysis. The difference between the two percentiles for the gauge at Woolsington had an average value of 155.66 m3/day and a standard deviation of 80.65 m3/day. Similarly, for the gauge at Crag Hal, the difference between the two percentiles had an average value of 269.47 m3/day, with a standard deviation of 144.61 m3/day. Compared to the observed timeseries, there was good correlation for both gauges in terms of both the timing and magnitude of the hydrographs (Figure 9). It should be noted, however, that at both gauges, the receding parts of the hydrographs showed smoother slopes for the simulated baseflow, compared to the observed. Finally, the KGE between the observed and median simulated baseflow was 0.453 for the gauge at Woolsington and 0.277 for the gauge at Crag Hall.

Figure 9.

Observed vs. simulated baseflow percentiles at the two gauging stations for the model calibration period, following the Monte Carlo analysis with 500 different model formulations. (Top): gauging station at Woolsington. (Bottom): gauging station at Crag Hall.

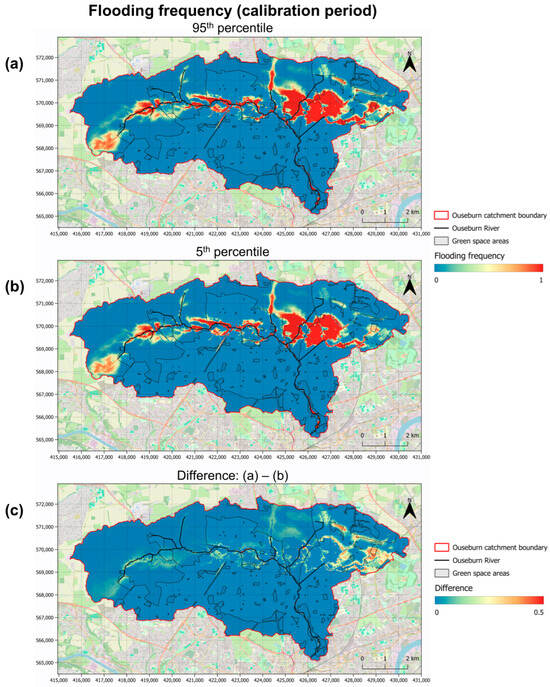

The flooding frequency for the 5th and 95th percentiles from the Monte Carlo analysis for the model calibration period is presented in Figure 10a,b. The differences plot (Figure 10c) highlighted that differences between the two percentiles can be observed in the northern half of the model domain. This was primarily around the eastern, northeastern, and western parts of the catchment, which are also areas of high geological uncertainty (see Ntigkakis et al., 2025 [24]). For the 95th percentile, the average flooding frequency was 0.12, and the standard deviation was 0.28. Similarly, for the 5th percentile, the average flooding frequency was 0.10, and the standard deviation was 0.26. That represents an approximate 18% difference in terms of average flooding frequency between the two percentiles. Finally, the plots highlighted areas in the middle and eastern parts of the catchment with significantly high flooding frequencies, indicating an overestimation of groundwater levels in those areas across the different model formulations.

Figure 10.

Spatial plot of the flooding frequency percentiles for the model calibration period, following the Monte Carlo analysis with 500 different model formulations. Shaded areas within the model domain represent the extent of green spaces. (a) 95th percentile, (b) 5th percentile, (c) Difference (a,b) (contains: Map data from OpenStreetMap; OS data © Crown copyright 2025; EA data © Crown copyright 2025; coordinates in EPSG:27700).

4.3. Validation Period

The simulated baseflow at the two gauging stations, for the 5th and 95th percentiles of the Monte Carlo analysis, for the model validation period, is shown in Figure 11. The simulated baseflow at both gauging stations showed minimal variability, with the confidence interval between the two percentiles being significantly small. This indicated little variability between the different model formulations of the Monte Carlo analysis. More specifically, for the gauge at Woolsington, the difference between the two percentiles had an average value of 208.64 m3/day and a standard deviation of 122.85 m3/day. As for the gauge at Crag Hall, the difference between the two percentiles had an average value of 365.68 m3/day and a standard deviation of 250.53 m3/day.

Figure 11.

Observed vs. simulated baseflow percentiles at the two gauging stations for the model validation period, following the Monte Carlo analysis with 500 different model formulations. (Top): gauging station at Woolsington. (Bottom): gauging station at Crag Hall.

Compared to the observed timeseries, the simulated baseflow at both gauges presented good correspondence in terms of both the timing and magnitude of the hydrographs. Again, however, the receding parts of the hydrographs for the simulated baseflow showed smoother slopes compared to the observed. Finally, the KGE between the observed and median simulated baseflow was 0.522 for the gauge at Woolsington and 0.423 for the gauge at Crag Hall.

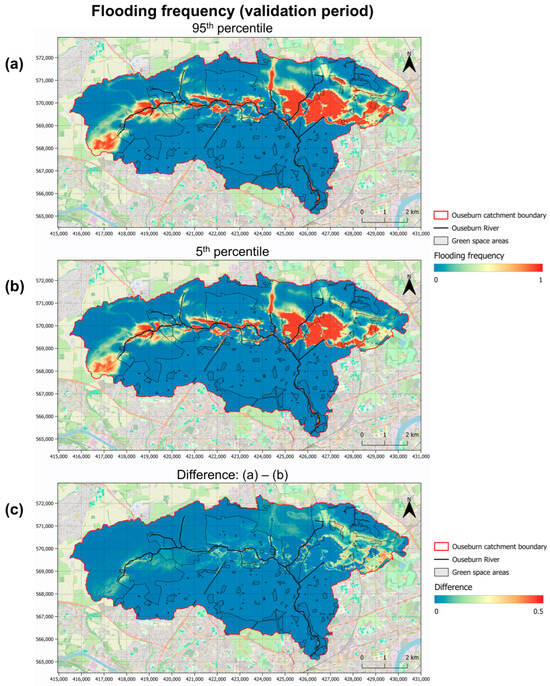

The flooding frequency for the 5th and 95th percentiles from the Monte Carlo analysis for the model validation period is presented in Figure 12a,b. Differences between the two percentiles (Figure 12c) can again be observed at the same areas as the model calibration period, namely around the eastern, northeastern, and western parts of the catchment. For the 95th percentile, the average flooding frequency was 0.15, and the standard deviation was 0.28. Similarly, for the 5th percentile, the average flooding frequency was 0.13, and the standard deviation was 0.27. That represents an approximate 14% difference in terms of average flooding frequency between the two percentiles. Finally, the plots highlighted areas in the middle and eastern parts of the catchment with significantly high flooding frequencies, indicating an overestimation of groundwater levels in those areas across the different model formulations.

Figure 12.

Spatial plot of the flooding frequency percentiles for the model validation period, following the Monte Carlo analysis with 500 different model formulations. Shaded areas within the model domain represent the extent of green spaces. (a) 95th percentile, (b) 5th percentile, (c) Difference (a,b) (contains: Map data from OpenStreetMap; OS data © Crown copyright 2025; EA data © Crown copyright 2025; coordinates in EPSG:27700).

5. Discussion

This study focused on investigating the influence of geological uncertainty on the hydrogeological modeling process. More specifically, it focused on the uncertainty originating from highly uncertain geological datasets, a common problem for urban areas [8,11], and how it affects the calibration and validation of a groundwater model. To that end, it used a case study of an urban catchment with a highly uncertain geological dataset and a recent advancement in mitigating uncertainty in the geological model to develop an ensemble of geological interpretations. It then used common practices in hydrogeological modeling to develop, calibrate, and validate both a distributed groundwater recharge and a groundwater flow model. Finally, it performed an uncertainty analysis to evaluate how the geological uncertainty influences the hydrogeological model calibration and validation.

To evaluate the effects of the geological uncertainty on the groundwater model results, this research employed a Monte Carlo analysis. More specifically, it evaluated the effects of altering the groundwater model layer definition through different geological formulations. This effectively treated the model structure as a variable rather than something static, which remains unchanged throughout the modeling process, thus accounting for different geological interpretations using the same available information.

In terms of model calibration, simulated baseflows at the two gauging stations presented little variability between the different model formulations. The small variability in simulated baseflows was indicated by the very narrow confidence intervals for the 5th and 95th percentiles. Therefore, it was expected that the geological uncertainty would not have a big influence on the model calibration process, due to the narrow confidence intervals in simulated baseflows.

In terms of flooding frequency, however, the confidence intervals between the 5th and 95th percentiles for the model calibration were noticeably wider. As a reminder, this research did not perform a flooding frequency analysis, and the term “flooding frequency” is only used as an indicator of simulated groundwater levels over time. As such, the wide confidence intervals indicated higher uncertainty in the simulated groundwater levels. This is primarily significant in the eastern and northeastern parts of the catchment, which are the areas with higher degrees of geological uncertainty (see Ntigkakis et al., 2025 [24]). There is therefore evidence to suggest that different geological realizations, and thus different model structures, can lead to a difference in simulated groundwater levels.

The same observations can be made for the simulated baseflows and flooding frequency for the model validation process. The confidence intervals for the simulated baseflows at the two gauging stations were very narrow, indicating little variability between the different model formulations. However, the flooding frequency plots showed wider confidence intervals, indicating a difference in simulated groundwater heads from the different model formulations.

This difference in simulated heads between the different geological interpretations can be significant when evaluating the effects of groundwater flooding in an urban environment. More specifically, models are commonly used as a platform to evaluate proposed actions, policies, climate change, and other issues. Although it might appear to be calibrated, introducing uncertainty in the geological interpretation on which the model was built may introduce uncertainty in the model results. Therefore, this can have significant implications for proposed flood defense mechanisms or other policies. It should be noted that this research only examined a single case study. However, the challenges within this case study in terms of data quality and availability are not unique and can be extrapolated to various other urban areas. Therefore, there is a need for further analysis on different locations.

Another important observation is that the areas with high flooding frequency in both the calibration and validation periods overlapped with areas where efforts have been made to reduce surface water flooding. More specifically, as discussed earlier, stormwater management schemes have been constructed near Newcastle Great Park, Killingworth, and Longbenton areas [59,62]. Although evidence supports the assumption that these are not connected to the groundwater, the model consistently simulated high groundwater levels in these areas. Furthermore, these same areas are highly uncertain in terms of both geological uncertainty and simulated groundwater levels uncertainty. There is therefore a need for further investigation in these areas.

This also highlights the need for holistically evaluating flood defense and surface water management infrastructure in terms of both surface water and groundwater. Blue–Green Infrastructure is known to alter groundwater recharge, and thus impact areas of shallow groundwater [19,20]. Therefore, even for surface water-dominated catchments, it is important to evaluate any intervention against the entire hydrological and hydrogeological regime. As interest in the urban subsurface grows, and with the effects of climate change, having a robust understanding of the entire system is key. This further reinforces the need for understanding how existing, highly uncertain datasets can be used to inform future models and decisions.

It should be noted, however, that the model calibration presented within this research was performed manually, due to the lack of appropriate groundwater level observations. Effective model calibration requires measurements of both groundwater levels and groundwater fluxes to adequately constrain the inverse problem [2,100]. However, only flux measurements were available in the form of baseflow estimations. The lack of groundwater level observations means that the model cannot be calibrated to both hydraulic conductivity and recharge rate, but rather only to the ratio of the two. This effectively means that the calibration process presented within this research could only capture the relative relation between these two quantities, and not each of them individually. Therefore, although the model could not be effectively calibrated and used in a predictive capacity, it could still be used to identify patterns in groundwater flow. Future research could also examine including soft knowledge within the calibration process through parameter regularization. Moreover, model calibration was performed using a period of 10 years. This potentially introduces bias towards the duration of the calibration and potential hidden trends within the datasets. Future work could focus on expanding the calibration period as data availability improves.

Furthermore, Figure 9 and Figure 11 show that the model performed better in capturing high-flow events compared to low-flow events. This was also evident from the receding parts of the hydrographs, which had smoother slopes in the simulated timeseries. It is important to highlight, however, that the observed timeseries is the product of a baseflow separation analysis on the total observed streamflow, and not a direct measurement. As such, it is expected that there will be uncertainties in the baseflow separation approach, which have not been accounted for in this research. Moreover, in the context of a flooding investigation, it can be argued that it is more important for a model to capture the high-flow events.

Moreover, although the challenges in model calibration due to data scarcity did not allow for the KGE values to be higher, they can still offer valuable insight. More specifically, the KGE value for both the calibration and validation periods was higher for the gauge at Woolsington, compared to Crag Hall. The catchment at Crag Hall is highly influenced by urbanization (see Figure 2), highlighting how urban development can change the geology and hydrogeology and thus introduce further uncertainty into the model.

Therefore, this research provides valuable insight into how geological uncertainty can affect groundwater model performance. Traditional model development focuses on the parameterization and vertical discretization, especially in terms of heterogeneity. Although model sensitivity to the parameterization is well known and documented (see [40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55]), the influence of the geological data supporting multiple geological interpretations is not yet fully understood. This research demonstrated a link between that uncertainty and the groundwater model results.

However, there is a need to further investigate the effects of the geological uncertainty in groundwater models. Future work could examine the combined effects of model parameterization and uncertainty in the geological interpretation. Although model sensitivity to the parameterization was considered during model calibration, future work could include a more detailed sensitivity analysis on the model parameters. Furthermore, other methods for mitigating geological uncertainty could be investigated, as well as the possibility of constraining geological uncertainty through soft knowledge or geophysical measurements. Although this is an active area of research in geological modeling, it is valuable to investigate how these methods could be applied to support groundwater modeling. Finally, future work could focus on expanding the analysis presented within this research to other data-scarce areas.

6. Conclusions

This study investigated how the uncertainty in the geological interpretation, originating from highly uncertain geological datasets, affected hydrogeological model performance. To that end, it developed a case study and performed an uncertainty analysis, using a recent development in mitigating uncertainty in kriging-based geological modeling. This study used an ensemble of geological realizations and evaluated how the different geological structures affect both the calibration and validation of a hydrogeological model.

Although the data-scarcity problem did not allow for the final model to be used for a predictive analysis, it can still offer valuable insights by identifying patterns in the model results. As such, the analysis showed that there is little variation in simulated baseflows between the different model structures. However, the different geological realizations led to a significant difference in simulated flooding frequency.

This can be significant, especially in urban areas or areas prone to groundwater flooding. Urban development tends to alter the near-surface geology [24], increasing geological uncertainty. The altering of the near-surface geology is also shown to have significant effects on shallow groundwater levels [101]. When evaluating the effects of groundwater flooding in urban areas, small variations in groundwater levels can have significant social, economical, and environmental effects. It is, therefore, important to have a robust understanding of the subsurface characterization and how the geological uncertainty affects the hydrogeological simulations.

With the increased interest in the urban subsurface and the difficulties in acquiring new data, mitigating the uncertainty in the existing, uncertain datasets is of growing importance. This research can help understand how highly uncertain geological datasets can still be used to support hydrogeological investigations. Therefore, it provides valuable insights into how the uncertainty in the geological data influences the groundwater models used for urban planning, policy making, water resources, and groundwater flooding protection.

When evaluating uncertainty within a model, it is important to view that uncertainty in relation to the model’s purpose. In the context of uncertainty within a geological model, it is, therefore, important to keep in mind how that model might be used to support further scientific investigations. Although geological uncertainty might be low when examined in the context of a geological model, it might play a more significant role in the context of a hydrogeological model. Ultimately, uncertainty should be viewed not in isolation, but with regards to the modeling objective. This will guide the amount of uncertainty that is acceptable, as well as an appropriate method of mitigating it.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.N., S.B., and R.S.; Methodology, C.N.; Software, C.N.; Validation, C.N., S.B., and R.S.; Formal Analysis, C.N.; Investigation, C.N.; Resources, S.B. and R.S.; Data Curation, C.N.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, C.N.; Writing—Review and Editing, S.B. and R.S.; Supervision, S.B. and R.S.; Project Administration, R.S.; Funding Acquisition, R.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Newcastle University and the Water Infrastructure and Resilience Centre for Doctoral Training (WIRe CDT), funded by the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC) under grant EP/S023666/1.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Brian Thomas for his invaluable contributions to the initial stages of this research.

Conflicts of Interest

We declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Parameter Values

Table A1.

Parameter values used in the SWAc and MODFLOW models.

Table A1.

Parameter values used in the SWAc and MODFLOW models.

| Parameter | Value | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Kx1 | 0.7 m/day | Horizontal hydraulic conductivity of the superficial deposits |

| Kz1 | 0.1 m/day | Vertical hydraulic conductivity of the superficial deposits |

| Kx2 | 1.5 m/day | Horizontal hydraulic conductivity of the bedrock |

| Kz2 | 0.5 m/day | Vertical hydraulic conductivity of the bedrock |

| Sy | 0.012 | Specific yield |

| Ss | 10−5 m−1 | Specific storage |

| rurban | 0.1 mm/day | Effective groundwater recharge from urban areas |

| rocoef | See Table A2 | Surface runoff coefficient |

| Kc | 0.7 | Crop coefficient for adjusting the reference potential evapotranspiration |

| TAW | 149.53 mm | Total Available Water |

| p | See Table A3 | Depletion factor for estimating RAW from TAW |

| relpr | 0.3 | Proportion of the recharge store that can be released per time step |

| rellim | 2 mm/day | Upper limit of the amount of recharge that can be released from the recharge store per time step |

Table A2.

Runoff coefficients depending on Soil Moisture Deficit (SMD) and Rainfall Intensity (ri) classes used for the FAO process within the SWAc model.

Table A2.

Runoff coefficients depending on Soil Moisture Deficit (SMD) and Rainfall Intensity (ri) classes used for the FAO process within the SWAc model.

| SMD (mm) | SMD ≤ 10 | 10 < SMD ≤ 30 | SMD > 30 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ri (mm/Day) | ||||

| 0.30 | 0.20 | 0.10 | ||

| 0.65 | 0.32 | 0.20 | ||

| 0.85 | 0.54 | 0.30 | ||

Table A3.

Depletion factor (p) used for calculating the Readily Available Water (RAW) used for the FAO process within the SWAc model.

Table A3.

Depletion factor (p) used for calculating the Readily Available Water (RAW) used for the FAO process within the SWAc model.

| Month | p | Month | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| January | 0.81 | July | 0.70 |

| February | 0.81 | August | 0.72 |

| March | 0.79 | September | 0.76 |

| April | 0.76 | October | 0.79 |

| May | 0.72 | November | 0.81 |

| June | 0.70 | December | 0.82 |

References

- Borzì, I. Modeling Groundwater Resources in Data-Scarce Regions for Sustainable Management: Methodologies and Limits. Hydrology 2025, 12, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, M.P.; Woessner, W.W.; Hunt, R.J. Applied Groundwater Modeling: Simulation of Flow and Advective Transport; Elsevier Science: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; ISBN 978-0-08-091638-5. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.; Li, W. A Review of Regional Groundwater Flow Modeling. Geosci. Front. 2011, 2, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fetter, C.W. Applied Hydrogeology, 4th ed.; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2001; ISBN 978-0-13-088239-4. [Google Scholar]

- Reinecke, R.; Gnann, S.; Stein, L.; Bierkens, M.; De Graaf, I.; Gleeson, T.; Essink, G.O.; Sutanudjaja, E.H.; Ruz Vargas, C.; Verkaik, J.; et al. Uncertainty in Model Estimates of Global Groundwater Depth. Environ. Res. Lett. 2024, 19, 114066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brassington, F.C.; Younger, P.L. A Proposed Framework for Hydrogeological Conceptual Modelling. Water Environ. J. 2010, 24, 261–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attard, G.; Rossier, Y.; Eisenlohr, L. Urban Groundwater Age Modeling under Unconfined Condition—Impact of Underground Structures on Groundwater Age: Evidence of a Piston Effect. J. Hydrol. 2016, 535, 652–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, W.; Yang, L.; Deng, D.; Ye, J.; Clarke, K.; Yang, Z.; Zhuang, W.; Liu, J.; Huang, J. Assessing Quality of Urban Underground Spaces by Coupling 3D Geological Models: The Case Study of Foshan City, South China. Comput. Geosci. 2016, 89, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyle, M.R. From Hydro/Geology to the Streetscape: Evaluating Urban Underground Resource Potential. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2016, 55, 83–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F.; Li, M.; Huang, C.; Liang, H.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wang, B.; Hao, M. Lithology-Based 3D Modeling of Urban Geological Attributes and Their Engineering Application: A Case Study of Guang’an City, SW China. Front. Earth Sci. 2022, 10, 918285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, L. Large-Scale Urban 3D Geological Modeling Based on Multi-Method Coupling Under Multi-Source Heterogeneous Data Conditions. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 12059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macdonald, D.; Dixon, A.; Newell, A.; Hallaways, A. Groundwater Flooding within an Urbanised Flood Plain. J. Flood Risk Manag. 2012, 5, 68–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, S.E.; Cobby, D.; Zaidman, M.; Fisher, K. Modelling and Mapping Groundwater Flooding at the Ground Surface in Chalk Catchments. J. Flood Risk Manag. 2018, 11, S1–S553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aicha, O.; Abdessamad, G.; Hassane, J.O. Groundwater Flooding in Urban Areas: Occurrence Process, Potential Impacts and the Role of Remote Sensing and GIS Techniques in Preventing It. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference of Moroccan Geomatics (Morgeo), Casablanca, Morocco, 11–13 May 2020; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Allocca, V.; Di Napoli, M.; Coda, S.; Carotenuto, F.; Calcaterra, D.; Di Martire, D.; De Vita, P. A Novel Methodology for Groundwater Flooding Susceptibility Assessment through Machine Learning Techniques in a Mixed-Land Use Aquifer. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 790, 148067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macdonald, D.; Bloomfield, J.; Hughes, A.; MacDonald, A.; Adams, B.; McKenzie, A. Improving the Understanding of the Risk from Groundwater Flooding in the UK. In Flood Risk Management: Research and Practice; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2008; pp. 1071–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Yin, H.; Xu, Z.; Peng, J.; Yu, Z. Pin-Pointing Groundwater Infiltration into Urban Sewers Using Chemical Tracer in Conjunction with Physically Based Optimization Model. Water Res. 2020, 175, 115689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Su, X.; Prigiobbe, V. Groundwater-Sewer Interaction in Urban Coastal Areas. Water 2018, 10, 1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locatelli, L.; Mark, O.; Mikkelsen, P.S.; Arnbjerg-Nielsen, K.; Deletic, A.; Roldin, M.; Binning, P.J. Hydrologic Impact of Urbanization with Extensive Stormwater Infiltration. J. Hydrol. 2017, 544, 524–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Chui, T.F.M. A Review on Implementing Infiltration-Based Green Infrastructure in Shallow Groundwater Environments: Challenges, Approaches, and Progress. J. Hydrol. 2019, 579, 124089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, B.; Kumar, P.; Patidar, N.; Kumar, S. Ensemble Modelling Framework for Groundwater Level Prediction in Urban Areas of India. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 712, 135539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerner, D.N. Groundwater Recharge in Urban Areas. Atmos. Environ. 1990, 24, 29–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, W.; Yi, S.; Huang, T.; Zou, J.; Zhou, W.-H.; Shen, P. Geophysics-Informed Stratigraphic Modeling Using Spatial Sequential Bayesian Updating Algorithm. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 2025, 17, 4400–4412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntigkakis, C.; Birkinshaw, S.; Stirling, R. Geological Modelling of Urban Environments Under Data Uncertainty. Geosciences 2025, 15, 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, H.-J. An Application-Oriented View of Modeling Uncertainty. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2000, 122, 190–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaganis, P.; Smith, L. Evaluation of the Uncertainty of Groundwater Model Predictions Associated with Conceptual Errors: A per-Datum Approach to Model Calibration. Adv. Water Resour. 2006, 29, 503–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas, R.; Feyen, L.; Dassargues, A. Conceptual Model Uncertainty in Groundwater Modeling: Combining Generalized Likelihood Uncertainty Estimation and Bayesian Model Averaging. Water Resour. Res. 2008, 44, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bredehoeft, J. The Conceptualization Model Problem—Surprise. Hydrogeol. J. 2005, 13, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poeter, E.; Anderson, D. Multimodel Ranking and Inference in Ground Water Modeling. Ground Water 2005, 43, 597–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.; Wang, Y. Data-Driven Construction of Three-Dimensional Subsurface Geological Models from Limited Site-Specific Boreholes and Prior Geological Knowledge for Underground Digital Twin. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2022, 126, 104493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Xu, X.; Peng, P.; Wang, L.; Tian, S. A Deep Learning-Driven Three-Dimensional Geological Modeling Method Using Sparse Borehole Sampling Data. Measurement 2025, 256, 118461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hang, Z.; Xue, T.; Chen, J.; Shi, Y.; Yin, Z.; Cui, Z.; Zhou, G. A 3D Geological Modeling Method Using the Transformer Model: A Solution for Sparse Borehole Data. Minerals 2025, 15, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Xu, X.; Wang, L.; Wang, X.; Wu, L.; Jessell, M.; Ogarko, V.; Liu, Z.; Zheng, Y. GeoPDNN 1.0: A Semi-Supervised Deep Learning Neural Network Using Pseudo-Labels for Three-Dimensional Shallow Strata Modelling and Uncertainty Analysis in Urban Areas from Borehole Data. Geosci. Model Dev. 2024, 17, 957–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, B.; Wang, Y.; Shi, C. Multi-Scale Generative Adversarial Networks (GAN) for Generation of Three-Dimensional Subsurface Geological Models from Limited Boreholes and Prior Geological Knowledge. Comput. Geotech. 2024, 170, 106336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, W.; Yang, C.; Shen, P.; Zhou, W.-H. Efficient Probabilistic Tunning of Large Geological Model (LGM) for Underground Digital Twin. Eng. Geol. 2025, 350, 107996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, M.; Ren, B.; Wu, B.; Tong, D.; Ge, S.; Han, S. A Parametric 3D Geological Modeling Method Considering Stratigraphic Interface Topology Optimization and Coding Expert Knowledge. Eng. Geol. 2021, 293, 106300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Xiao, S.; Zhang, R.; Weng, Z.; Wu, X.; Wu, Y. Local Dynamic Update Methods for 3D Geological Body Structure Model and Voxel Model. Earth Sci. Inf. 2024, 17, 841–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Harten, J.; De La Varga, M.; Hillier, M.; Wellmann, F. Informed Local Smoothing in 3D Implicit Geological Modeling. Minerals 2021, 11, 1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caumon, G.; Collon-Drouaillet, P.; Le Carlier de Veslud, C.; Viseur, S.; Sausse, J. Surface-Based 3D Modeling of Geological Structures. Math. Geosci. 2009, 41, 927–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemizade, M.; Moeck, C.; Schirmer, M. The Effect of Model Complexity in Simulating Unsaturated Zone Flow Processes on Recharge Estimation at Varying Time Scales. J. Hydrol. 2015, 529, 1173–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, J.; Stengel, V.; Rendon, S.; Banta, J. The Importance of Parameterization When Simulating the Hydrologic Response of Vegetative Land-Cover Change. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2017, 21, 3975–3989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, T.; Sreekanth, J.; Pickett, T.; Rassam, D.; Gilfedder, M.; Barrett, D. Impact of Model Parameterization on Predictive Uncertainty of Regional Groundwater Models in the Context of Environmental Impact Assessment. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2021, 90, 106620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schöniger, A.; Illman, W.A.; Wöhling, T.; Nowak, W. Finding the Right Balance between Groundwater Model Complexity and Experimental Effort via Bayesian Model Selection. J. Hydrol. 2015, 531, 96–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knowling, M.J.; White, J.T.; Moore, C.R. Role of Model Parameterization in Risk-Based Decision Support: An Empirical Exploration. Adv. Water Resour. 2019, 128, 59–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, J.T.; Knowling, M.J.; Moore, C.R. Consequences of Groundwater-Model Vertical Discretization in Risk-Based Decision-Making. Groundwater 2020, 58, 695–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Tsai, F.T.-C.; Kao, S.-C. Accounting for Uncertainty in Complex Alluvial Aquifer Modeling by Bayesian Multi-Model Approach. J. Hydrol. 2021, 601, 126682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawo, N.S.; Korus, J.; Kishawi, Y.; Haacker, E.M.K.; Mittelstet, A.R. Three-Dimensional Probabilistic Hydrofacies Modeling Using Machine Learning. Water Resour. Res. 2024, 60, e2023WR035910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, T.D.; Andrieu, H.; Hamel, P. Understanding, Management and Modelling of Urban Hydrology and Its Consequences for Receiving Waters: A State of the Art. Adv. Water Resour. 2013, 51, 261–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvadore, E.; Bronders, J.; Batelaan, O. Hydrological Modelling of Urbanized Catchments: A Review and Future Directions. J. Hydrol. 2015, 529, 62–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pophillat, W.; Sage, J.; Rodriguez, F.; Braud, I. Consequences of Interactions between Stormwater Infiltration Systems, Shallow Groundwater and Underground Structures at the Neighborhood Scale. Urban Water J. 2022, 19, 812–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hibbs, B.J.; Sharp, J.M. Hydrogeological Impacts of Urbanization. Environ. Eng. Geosci. 2012, 18, 3–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attard, G.; Rossier, Y.; Eisenlohr, L. Underground Structures Increasing the Intrinsic Vulnerability of Urban Groundwater: Sensitivity Analysis and Development of an Empirical Law Based on a Groundwater Age Modelling Approach. J. Hydrol. 2017, 552, 460–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berthier, E.; Andrieu, H.; Creutin, J. The Role of Soil in the Generation of Urban Runoff: Development and Evaluation of a 2D Model. J. Hydrol. 2004, 299, 252–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boukhemacha, M.A.; Gogu, C.R.; Serpescu, I.; Gaitanaru, D.; Bica, I. A Hydrogeological Conceptual Approach to Study Urban Groundwater Flow in Bucharest City, Romania. Hydrogeol. J. 2015, 23, 437–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epting, J.; Huggenberger, P.; Rauber, M. Integrated Methods and Scenario Development for Urban Groundwater Management and Protection during Tunnel Road Construction: A Case Study of Urban Hydrogeology in the City of Basel, Switzerland. Hydrogeol. J. 2008, 16, 575–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, A.; Lagi, M. Surface Water Accounting Model, SWAc—Linking Surface Flow and Recharge Processes to Groundwater Models. In Proceedings of the 15th Meeting of the Groundwater Modellers’ Forum, Birmingham, UK, 8 November 2017; p. 5. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, J.D.; Langevin, C.D.; Banta, E.R. Documentation for the MODFLOW 6 Framework; USGS: Techniques and Methods 6-A57; U.S. Geological Survey: Reston, VA, USA, 2017; 42p.

- Environment Agency. Ouse Burn from Source to Tyne Water Body—Catchment Data Explorer; Environment Agency: Bristol, UK, 2023.

- Birkinshaw, S.J.; Kilsby, C.; O’Donnell, G.; Quinn, P.; Adams, R.; Wilkinson, M.E. Stormwater Detention Ponds in Urban Catchments—Analysis and Validation of Performance of Ponds in the Ouseburn Catchment, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK. Water 2021, 13, 2521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Environment Agency. LIDAR Composite Digital Terrain Model (DTM)—1m; Environment Agency: Bristol, UK, 2023.