Abstract

Decontamination of wastewater, industrial effluents, stormwater, and graywater can be carried out through the use of natural or constructed wetlands. In either case, the natural functions of soil, vegetation, and organisms are widely applied for the treatment of contaminated water. In particular, in the physical design of a constructed wetland, several operational factors must be adjusted with the aim of reducing pollution levels. Although various fully customized design methodologies have been developed and reported in the literature, they often fail to meet the required decontamination objectives. In this context, the application of the NSGA-II evolutionary algorithm is adequate to optimize the physical design of a horizontal subsurface flow wetland for graywater treatment, focusing specifically on the removal of biodegradable organic matter (BOD5). Four competing objectives are considered: minimizing physical volume and total design cost, while maximizing contaminant removal efficiency and graywater flow rate. Five constraint functions are also incorporated: removal efficiency greater than 95%, physical volume below 1000 m3, flow rate above 10 m3/d, a limit on total construction cost of MXN 1,000,000, and maintaining a length-to-width ratio greater than or equal to 2 but less than or equal to 4. The proposed methodology generates a wide set of non-dominated solutions, visualized through Pareto surfaces, which highlight the trade-offs among different objectives. This approach offers the possibility of selecting optimal designs under specific conditions, which underscores the limitations of conventional single-solution models. The results show that the methodology consistently achieved removal efficiencies above 95%, with construction costs within budget and physical volumes below the established limit, offering a more versatile and cost-effective alternative. This work demonstrates that the integration of NSGA-II into wetland design is an effective and adaptable strategy, capable of providing sustainable alternatives for graywater treatment and constituting a valuable decision-making tool.

1. Introduction

Pollution is a very important issue in the world because it aggravates various environmental problems, such as soil erosion, air quality degradation, and water scarcity. Regarding this last issue, the treatment of water resources is very important and it is necessary that wastewater treatment processes are efficient and effective. In response to this need, constructed wetland technology is an environmentally friendly option for water management. This technology has not only been proven around the world to have multiple environmental and economic advantages, but can also function as habitat creation sites, water treatment plants, recreational or educational facilities, urban wildlife refuges, landscape engineering, and ecological art areas, among others. However, although constructed wetlands achieve a significant reduction in the pollutants present in graywater, such as biodegradable organic matter, nutrients, and pathogens, the concentrations of these compounds vary depending on the source of generation, which generally includes showers, baths, sinks, laundry, floor cleaning, and similar uses [1,2].

Research focused on optimization-based design has incorporated multiple mathematical and decision-support tools. Among the most representative approaches are empirical models, such as the one proposed by Reed and reported by Andreo et al. [3]; non-stationary reinforcement learning methods integrated into decision-support systems, such as WRESTORE, described by Hoblitzell et al. [4]; hydrodynamic modeling using the MIKE 21 software, employed by Liao et al. [5]; and neural networks optimized through the ADAM algorithm, implemented by Pengyu et al. [6]. Within this framework, multi-objective optimization algorithms, particularly NSGA-II, have gained increasing importance due to their ability to simultaneously manage conflicting design criteria. More recently Mendez et al. [7] carried out the evolutionary optimization of an HFSW for graywater treatment using the NSGA-II evolutionary algorithm. Two objectives were established: minimize the physical volume of the HFSW and maximize the contaminant removal efficiency. These objectives are defined based on six performance variables: hydraulic retention time, length, width, water depth, media depth, and slope. The set of solutions is obtained to generate the Pareto front. However, they do not consider either the flow rate or the construction costs of the HFSW as optimization objectives. This fact translates into high costs and a minimum flow of water to be treated. Likewise, the search space for its solutions is restricted to a small volume, limiting the exploration of new search spaces.

According to [3,4,5,6,7], all artificial wetlands designed and some already constructed use different design methodologies, but none address the problem from a multi-objective optimization approach, unlike [4,7]. This represents a serious drawback, since the structure of said artificial wetlands differs substantially from reality. Therefore, some artificial wetlands not only consume a lot of economic resources during their construction and maintenance, but also do not guarantee that wastewater treatment is the most effective. In fact, several constructed wetlands cease to function once their capacity is exceeded due to inadequate design planning. This situation often makes rehabilitation more expensive than building a new system, in part because these designs are often based on trial-and-error methodologies. For instance in [3], although an optimization approach is applied and achieves high removal efficiency, this approach obtains a single solution. Similarly, ref. [8] generates a simple design that does not guarantee maximum efficiency, nor does it offer more economical alternatives.

Furthermore, the numeric value of each design variable was obtained from the literature, which limits the exploration of new approaches. Large-scale wetland systems were proposed in [9,10]. This drawback is due to the fact that multi-objective optimization methodologies were not used, limiting the possibility of identifying more compact and cost-effective alternatives without compromising efficiency. These works illustrate how the absence of multi-objective optimization can lead to inefficient, costly, and underperforming designs, highlighting the need to use methodologies that simultaneously balance multiple criteria to achieve more robust and sustainable solutions. Therefore, as an improved continuation of the work reported in [7], this study optimizes an HFSW using the evolutionary algorithm NSGA-II with four objective functions and five constraints. The new objectives include the maximization of the flow rate and the minimization of the total cost. This expansion of the optimization framework enhances the realism of the design process, allows a broader exploration of the solution space, and improves the identification of more balanced configurations in terms of hydraulic, economic, and treatment efficiency performance. Additionally, the results are presented as Pareto surfaces, which improve the visualization of the interactions among the objectives. Overall, this study provides a more comprehensive and applicable optimization framework capable of overcoming the limitations identified in previous research and contributing to the sustainable design of wastewater treatment systems.

The multi-objective optimization concept is mathematically defined in Section 2, and a brief description of the multi-objective optimizer that will be used is also introduced. The first-order behavioral equations, the objective and constraint functions, and the design variables to be used in the optimization process are described in Section 3. The Pareto fronts generated by the combination of the four objective functions defined above are obtained numerically in Section 4. On these fronts, not only is the fulfillment of each constraint function verified, but also any point can be selected and the numerical value associated with each design variable is automatically obtained. As a consequence, the HFSW can be built a posteriori, saving design time. A brief discussion about the multi-objective optimization of the HFSW along with its advantages and disadvantages are presented in Section 5. Conclusions are finally given in Section 6.

2. Formulating the Multi-Objective Optimization Dilemma

A multi-objective optimization problem is formulated as

where f(x) is the vector of p objective functions, c(x) is the vector of k constraint functions, and x is the vector of q design variables on the decision space X. Here, each design variable is bounded by the lower limit and the upper limit . Several multi-objective optimization methodologies have been reported in the literature to solve Equation (1) based on generating or preference methods [11,12].

In the former case, this is subdivided in mathematical programming techniques or metaheuristics. In particular, global search population-based metaheuristics include ant colony optimization, particle swarm optimization, the genetic algorithm, the bacterial foraging algorithm, the artificial bee colony algorithm, differential evolution, and the non-dominated sorting genetic algorithm (NSGA-II) [13], among others. In this work, the NSGA-II algorithm is used as the multi-objective optimizer, which is a powerful decision space exploration engine based on genetic algorithms [14]. Four fundamental principles are used in this evolutionary optimizer: non-dominated sorting, an elite-preserving operator, crowding distance, and a selection operator [13]. In this sense, NSGA-II performs a non-dominated classification of the combination of parent and child populations and classifies them by fronts; that is, they are classified according to an ascending level of non-domination. According to this generated front ranking, a new population vector is filled. For each front, a crowding-sort that uses crowding distance related to the density of solutions around each solution is performed. The less dense are preferred. Subsequently, an offspring population is created from this new population using crowded tournament selection, which compares by front ranking and then, if equal, by crowding distance, crossover, and mutation operators.

Thus, the NSGA-II algorithm searches for the best solutions of the HFSW design according to the design variables and taking a population of parents. Once all the solutions for each generation have been found, they will be stored in a file according to the number of generations until an optimal set is formed and the solutions to the problem are satisfied. Because the NSGA-II algorithm is coded to minimize objective functions, any of them can easily be converted into a maximization problem by multiplying the objective function by −1. Figure 1 shows a flowchart for the execution of the algorithm. In this diagram, the design variables are used to generate the initial population and their descendants in the second and third steps, respectively; in the fourth step, the objective and constraint functions are evaluated.

Figure 1.

NSGA-II algorithm flowchart [7].

3. HFSW Behavioral Model

To design an artificial HFSW [7,15], a first-order model associated with the kinetic design is used as

where [mg/L] and [mg/L] are the input–output concentrations of the pollutant, is the kinetic constant [d−1], and t is the hydraulic retention time [d]. Regarding the hydraulic design, the superface area () [m2] is taken into account as [16,17,18]

where Q is the flow rate [m3/d], is the substrate depth [m], and n = 0.35 is the porosity [16,17,18]. The width (W) [m] of the artificial HFSW is approximated as [7,8]

where is the water depth [m], s is the slope [%], and = 5000 is the hydraulic conductivity [m/d] [17,18]. Moreover, the length (L) [m] of the artificial HFSW is approximated as [7,8,17]

It is important to highlight that HFSW design is limited to its physical structure, without considering hydrological operations such as flooding, filtration, or evapotranspiration; environmental phenomena such as seasonal rainfall, hydraulic overloads, or temporal variability; and solute transport processes such as dispersion, clogging, or anisotropy. These processes influence actual performance and efficiency, even in optimized designs, since in a real HFSWs there is substrate obstruction, vegetation growth, and seasonal changes that affect the flow rate and substrate. According to [7,15,16,18], Equations (2)–(5) are valid behavioral models under quasi-steady flow assumptions in homogeneous media with constant porosity and hydraulic conductivity. As a consequence, the generated designs should be interpreted as theoretical optimal starting points, which still require validation under real operating conditions. Their main purpose is to compare design alternatives and estimate key design parameters, rather than to provide a detailed characterization of hydrodynamic and biochemical processes.

Objective Functions

From Equation (4), the flow rate is derived as

According to Equations (2)–(6) and unlike [7], the physical volume () [m3] is expressed as a function of the flow rate, substrate properties, and hydraulic retention time, defined as

The contaminant removal efficiency () [%] is defined as

Furthermore, the total cost of the HFSW design () [USD] is defined as

with

where is the cleaning cost [USD], is the area leveling cost [USD], and is the masonry cost [USD]. Also, is the pipe cost [USD], which takes into account as the cost of the tube [USD] and as the cost of the valve [USD]; is the filter media cost [USD], which includes for geomembrane costs [USD], for sand costs [USD], for gravel costs [USD], and for plant costs [USD]. The two objective functions given by Equations (7) and (9) must be minimized, and the two objective functions given by Equations (6) and (8) must be maximized. All these equations form the vector f(x), with p = 4 objective functions in Equation (1). It is important to mention that an objective function cannot be infinitely minimized or maximized, since the existence of constraints limit its performance. With this in mind, five constraint functions are defined as

From Equation (12), the aim is to obtain 95% (equivalent to 0.95) pollution removal, thus guaranteeing output concentrations lower than those established in the Official Mexican Standards [16]. Further, Equation (13) ensures a flow rate that exceeds 10 [m3/d] and then guarantees an adequate volume of treated waste water. The third constraint refers to the physical volume and its target is to ensure that said volume does not exceed 1000 m3. The following constraint guarantees that a specific relationship is established between L and W of the HFSW, setting the lower limit to 2 and the upper limit to 4 [7,15,16,18]. This is a difference compared with [7], where only a lower limit was used. Finally, the last constraint limits the total construction cost of the HFSW to be less than MNX 1,000,000.00. This upper limit was selected after carrying out several simulations considering two objectives, efficiency and physical volume [7], and subsequently three objectives: flow rate, efficiency, and physical volume. The objective of these simulations was to verify the behavior of the cost before considering it as the objective to optimize. In these tests, it is verified that, in certain cases, the cost exceeds NX 2,000,000.00 MXN, while in most cases it remains at MNX 1,500,000.00. Therefore, a cost that does not exceed MNX 1,000,000.00 was chosen as the upper limit.

The lower limit was selected in such a way that the operation of the HFSW is not compromised. If the cost is less than MNX 500,000.00, design parameters are obtained in which the dimensions are compromised, since a construction cost lower than this value could affect the efficiency and capacity of the system to treat a significant amount of water, as can be seen in [8]. Thus, Equations (12)–(16) form the vector c(x) with k = 5 constraint functions in Equation (1). After careful analysis, it can be seen that the objective functions and constraints depend on six design variables already defined above. Table 1 provides a detailed summary of the design variables to be used during the optimization process. Therefore, it is clear that the vector x = () in Equation (1). According to the literature and for comparison purposes, not only is the range of values for each design variable included in Table 1, but it is also ensured that the decisions made are based on verified and recognized information. However, to facilitate and enrich the process of searching for acceptable solutions, the decision space is expanded. This task is accomplished by expanding the range of values for each design variable. The limits and for each design variable were deduced by experimentation. At this point we highlight our contribution, since the multi-objective optimization problem for designing an HFSW is more complete than the one reported in [7].

Table 1.

Range of values for each design variable.

4. Numerical Results

The execution process of the NSGA-II algorithm and the evolution of the objectives were carried out by using a CPU with a 1.6 GHz Intel Core i5 and a memory size of 4 GB. The results obtained through the application of the NSGA-II algorithm for the multi-objective optimization of the physical design of the HFSW are detailed below.

4.1. Non-Dominated Solutions of the HFSW

The NSGA-II algorithm generates a set of solutions based on the population size (P) and number of generations (G). All solutions are subject to the constraints and design variables reported in Table 1 and are known as non-dominated solutions [12,13]. In this sense, Table 2 presents a summary of the solutions of the last generation for different values of P and G.

Table 2.

Objectives, constraints, and design variables found for different P and G values.

Since the NSGA-II algorithm uses a structured approach to generate a set of solutions, this ensures that the algorithm exhaustively explores the solution space, continually adapting and improving solutions over successive generations. In the detailed analysis of the data presented in the third column of Table 2, ≥ 0.95 stands out (or as a percentage ≥ 95%). This level of efficiency ensures that BOD5 concentrations are less than 20 mg/L, thus complying with the maximum permissible limits established by NOM-003-SEMARNAT-1997 in Mexico [16]. From the fourth column it is observed that Q ≥ 10 m3/d in all cases. Regarding , the data indicate that it remains below 1000 m3 in all cases, as shown in the fifth column of Table 2. In relation to , all the results are in the range defined above, as reflected in the sixth column of Table 2. This cost range demonstrates effective budget management in the optimization process, thus facilitating economic viability in the physical construction of the HFSW. Finally, the rest of the columns of Table 2 show all the values found by NGSA-II associated with the constraints and design variables established for the problem.

4.2. Pareto Surface

The Pareto surface is obtained by processing the solutions identified by NSGA-II using Matlab online and illustrates the interactions and trade-offs between the design objectives through their confrontation [22]. With this in mind, the Pareto surfaces are generated by confronting the objectives for different values of P and G. In Figure 2 and Figure 3, the Pareto surfaces are presented, in which it is observed that for greater values of P and G, the population density increases, improving the visualization of non-dominated solutions. Whereas Figure 2 shows the Pareto surface of the confrontation of vs. vs. Q, Figure 3 depicts the Pareto surface of the confrontation of vs. vs. . In this case, the axis is normalized to millions. For each surface, each blue point represents an acceptable solution that meets the constraints of the optimization problem. Therefore, all solutions are valid.

Figure 2.

Pareto surface of vs. vs. Q for (a) P = 80 and G = 100, (b) P = 200 and G = 400, (c) P = 500 and G = 700, and (d) P = 700 and G = 1000.

Figure 3.

Pareto surface of vs. vs. (axis normalized to millons) for (a) P = 80 and G = 100, (b) P = 200 and G = 400, (c) P = 500 and G = 700, and (d) P = 700 and G = 1000.

Figure 2 shows a decreasing trend between and ; meanwhile Q increases. This indicates that maintaining high removal efficiency requires either a larger volume or a lower flow rate. Furthermore, the solutions generate a continuous surface, demonstrating a balance between the objectives to be maximized, Q and , and minimized, . The solutions are concentrated in the region where is between 400 and 700 m3 and is between 0.96 and 0.99%, representing a viable compromise between efficiency and HFSW dimensions. Unlike those in Figure 2, the Pareto surfaces in Figure 3 exhibit greater irregularity, reflecting the complexity of the trade-off between and . In general, it is evident that increases with , while tends to stabilize around 0.98–0.99%. This suggests that an increase in the size of the HFSW results in higher without significant improvements in treatment. Therefore, Figure 2 and Figure 3 provide valuable insights for identifying optimal design configurations under multi-objective conditions, supporting the decision-making process in the HFSW physical design.

On the other hand, when selecting any blue point on the Pareto surface, all the information regarding the design of the HFSW will be displayed. For instance, Figure 4 shows a particular design and the numerical value associated with each design variable; the objective and constraint are given in row thirteen of Table 2. This is a big advantage, since all Pareto surfaces can be stored in a database and can be used later at any time, saving CPU resources. These results indicate that the NSGA-II algorithm is a robust optimizer that, adapted to the specific design characteristics of HFSW, allows design configurations to be obtained that optimize efficiency in wastewater treatment. This supports feasibility and reuse in wastewater management.

Figure 4.

Particular design of an HFSW.

Moreover, the results of the proposed design methodology are compared with various HFSW design configurations found in the literature [3,7,8,9,10,23,24,25,26]. To achieve this, an individual is selected from the Pareto surface and the performance parameters along with the design variables are compared with the HFSW designs reported in the literature, as described in Table 3. It can be seen that the reported designs are completely personalized. For instance, for achieving high contaminant removal a large surface area is required in [9,10]. Likewise, it is also observed in the cited references that only or is commonly considered for sizing and that the value of s used is generally 1 or 2. Furthermore, only four references inform about the construction costs; two of them are simple prototypes, and for the other two, the construction cost is high in relation to the physical design. Regarding the maximum flow that the designs reported in Table 3 can support, it can be seen that its is very high or very low. It is interesting to note that the cited references only report a single completely personalized design, whereas with the developed methodology a large repertoire of acceptable designs can be found, as seen in Figure 2 and Figure 3. For instance, in Figure 2d, P = 700, which corresponds to 700 acceptable designs.

Table 3.

Comparison with other works.

5. Discussion

The optimization methodology using NSGA-II is very useful in the physical design of the HFSW, finding configurations that adequately fit the constraints of the problem. The results obtained differ from previous studies due to the use of design variables and constraints within a multi-objective framework. By minimizing and and maximizing and Q simultaneously, a broader design space is explored in comparison with a single-objective approach. This wider search enables the identification of intermediate solutions between and , explaining the differences with the results reported in [3,7,8,9,10,23,24,25,26]. In particular, the smaller physical and intermediate obtained indicate a more compact and economically viable design strategy, adapted to the specific constraints of this work. It is evident that the 95% removal of contaminants is exceeded, ensuring that the volume does not exceed 1000 m3 and maximizing the flow of wastewater in the HFSW.

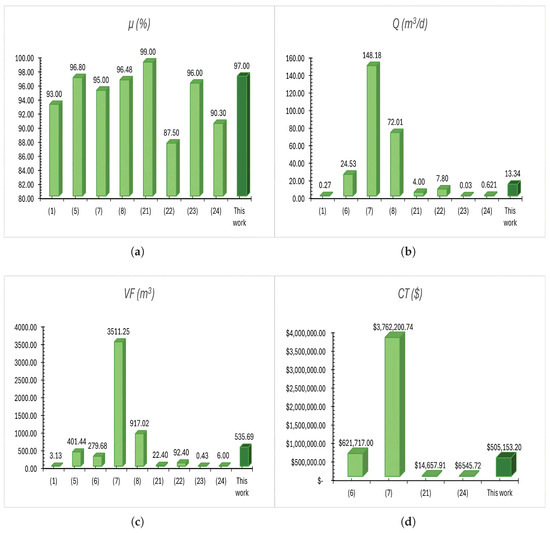

Minimizing the physical volume of the HFSW means less investment in materials and land for its execution and, as a consequence, a saving in economic resources in the total construction cost. These trade-offs can be checked on the Pareto surfaces shown in Figure 2 and Figure 3, which provide a view of all non-dominated solutions. By gradually increasing the values of P and G in each optimization process, not only is a better visualization of the behavior of the objective functions achieved, but also the Pareto surfaces are better formed, since a greater population density provides a valuable tool for decision making, allowing various design configurations to be evaluated based on the design variables and constraints of the problem. These findings demonstrate the effectiveness and robustness of the proposed methodology for optimizing the physical design of the HFSW. Comparing a solution obtained from the Pareto surface with previous studies, the advantages of applying a multi-objective optimization methodology become evident. For instance, the removal efficiency reached 97%, exceeding the values reported by [3,26], which reported 93% and 90.3%, respectively. Although [23] reported a removal efficiency of 99% and [25] 96%, these values were reached in wetlands with low treatment capacity, as shown in Figure 5a.

Figure 5.

Comparison of this work with previous studies: (a) removal efficiency (), (b) treated flow rate (Q), (c) physical volume () and (d) total cost ().

In Figure 5b, the flow rate of 13.34 m3/d obtained in this work clearly exceeds the values below 10 m3/d reported in [3,24,26]. Although [10] designed a system with a flow rate of 148.18 m3/d, this result was achieved at the expense of an excessive physical volume and total cost, which limits its practical implementation. However, it is advisable to keep the flow rate slightly below each computed value in each solution, which indicates an adaptation of the physical design to the specific and real needs of the HFSW. The latter is because in real situations, it is possible to generate an overflow of the flow due to the amount of water from seasonal rains, a situation that is not easy to control automatically. A possible solution to this drawback is to experimentally monitor the total capacity of the HFSW during seasonal rains and manually control the amount of polluted water at the wetland inlet or use a relief valve. The physical volume of 535.69 m3 achieved in this study is within the established limit (<1000 m3) and is considerably smaller than the designs of [10], with 3511.25 m3, and [9], with 917.02 m3. On the other hand, although [23,26] reported much smaller volumes, these correspond to systems with reduced flow capacity, which compromises their applicability, as illustrated in Figure 5c. Finally, regarding cost, the estimated value of MXN 505,153 represents an intermediate level compared to the analyzed studies, as shown in Figure 5d. Whereas [10] reported a cost exceeding MXN 3.7 million and [8] reached MXN 621,717, the designs generated maintain a much more affordable investment level. In contrast, although the costs reported by [23,26] were considerably lower, they correspond to wetlands with low treatment capacity, which reduces their feasibility in real-world applications.

However, the real design of an HFSW considers several objective functions related to the biological, chemical, and physical area, which complicates the multi-objective optimization process. This is because the design space must be expanded to find the best combination of all design variables that satisfy the target functions and constraints. This extension represents a disadvantage, since not only will more CPU resources be required, but also more execution time, since the values P and G will have to be increased to obtain greater diversity. Furthermore, hydraulic, transport, and biochemical processes, along with seasonal variations and factors such as clogging, vegetation growth, and decomposition, may significantly affect the long-term efficiency of the optimized configurations. These effects could lead to deviations from the predicted results, implying the need for experimental calibration and long-term monitoring. Therefore, these limitations have two main implications: first, they highlight the importance of integrating physical, biological, and chemical submodels into future optimization schemes, and second, they indicate that the current results should be considered as theoretical optimal configurations that must be validated under real field conditions.

Likewise, the limitations of the optimizer must be taken into account, since the number of objective functions that it can maximize or minimize is small. In this context, the methodology focuses on the physical design of the HFSW. The results provide a solid foundation for future interdisciplinary models capable of coupling hydrodynamics with the biological and chemical processes occurring within the HFSW. Expanding the scope of optimization to these domains could generate more comprehensive and representative designs, thereby improving sustainability and reliability. However, these considerations will remain for future work.

6. Conclusions

A novel multi-objective optimization methodology for the physical design of an HFSW based on the NSGA-II optimizer is presented. Unlike previously published works, such as [7], which considered only two objective functions, this research simultaneously optimizes four objective functions, minimization of physical volume and total cost and maximization of contaminant removal efficiency and flow rate, subject to five constraints. This integrated framework represents a significant advancement, as it enables a comprehensive exploration of the design space and reveals multiple trade-offs among the four objective functions. Compared with previous studies that focused on single-objective or semi-empirical approaches, the proposed methodology achieves superior performance, attaining removal efficiencies above 95%, with physical volumes below 1000 m3 and construction costs under MXN one million. This demonstrates that it is possible to design compact and economically viable wetlands without compromising treatment efficiency. Moreover, the generation of Pareto surfaces, as shown in Figure 2 and Figure 3, facilitates decision-making by allowing the selection of designs according to specific operational or budgetary requirements, providing a tool not available in previous studies that reported only single, fully customized configurations. Finally, this work establishes a foundation for the integration of physical, biological, and chemical models into future multi-domain optimization schemes. Such an expansion will enable more comprehensive and field-representative designs capable of capturing long-term dynamic effects such as clogging, vegetation growth, and seasonal variations. Consequently, the proposed methodology not only advances the theoretical understanding of HFSW optimization but also provides a practical decision-support tool for the sustainable design and implementation of nature-based wastewater treatment systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.M.-V., R.O.-M., and E.R.-P.; methodology, C.S.-L., E.R.-P., and J.A.-H.; software, J.M.-V., F.M.-G., and C.S.-L.; validation, J.M.-V., E.R.-P., and C.S.-L.; formal analysis, J.M.-V., M.A.C.-A., J.A.-H., and E.R.-P.; investigation, J.M.-V. and E.R.-P.; writing—original draft preparation, J.M.-V., L.M.-P., and E.R.-P.; writing—review and editing, C.S.-L., J.A.-M., and J.A.S.-M.; visualization, J.M.-V.; supervision, E.R.-P. and C.S.-L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

The first author thanks the SECIHTI 1240559 Doctoral Grant.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Hoffmann, H.; Platzer, C.; Winker, M.; Von Muench, E. Technology Review of Constructed Wetlands Subsurface Flow Constructed Wetlands for Greywater and Domestic Wastewater Treatment; Agencia de Cooperación Internacional de Alemania, GIZ Programa de Saneamiento Sostenible ECOSAN: Eschborn, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Murcia-Sarmiento, M.L.; Calderón-Montoya, O.G.; Díaz-Ortiz, J.E. Grey water impact on soil physical properties. Tecnológicas 2014, 17, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreo-Martínez, P.; García-Martínez, N.; Almela, L. Domestic wastewater depuration using a horizontal subsurface flow constructed wetland and theoretical surface optimization: A case study under dry Mediterranean climate. Water 2016, 8, 434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoblitzell, A.; Babbar-Sebens, M.; Mukhopadhyay, S. Non-Stationary Reinforcement-Learning Based Dimensionality Reduction for Multi-objective Optimization of Wetland Design. In Proceedings of the ICRAI ’19, 5th International Conference on Robotics and Artificial Intelligence, Singapore, 22–24 November 2019; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 82–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, R.; Jin, Z.; Chen, M.; Li, S. An integrated approach for enhancing the overall performance of constructed wetlands in urban areas. Water Res. 2020, 187, 116443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, P.; Zheng, T.; Li, L.; Lv, X.; Wu, W.; Shi, Z.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, G.; Ma, Y.; Liu, J. Simulating and predicting the performance of a horizontal subsurface flow constructed wetland using a fully connected neural network. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 380, 134959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendez-Valencia, J.; Sánchez-López, C.; Reyes-Pérez, E. Multi-objective design of a horizontal flow subsurface wetland. Water 2024, 16, 1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, C. Diseño de Humedal Construido para Tratar los Lixiviados del Proyecto de Relleno Sanitario de Pococí; Instituto Tecnológico de Costa Rica: Cartago, Costa Rica, 2010; Available online: https://repositoriotec.tec.ac.cr/handle/2238/6158 (accessed on 17 February 2024).

- Aguilar Paredes, K.A. Diseño de un Sistema de Tratamiento de Aguas Residuales con Humedales Artificiales para la Comunidad de Charcay, Provincia del Cañar (Ecuador). Master’s Thesis, Universitat Politècnica de València, València, Spain, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Basantes Cascante, C.E. Diseño de un Sistema de Humedales Artificiales para el Tratamiento de las Aguas Residuales de la Comunidad de Alacao, Provincia de Chimborazo (Ecuador). Master’s Thesis, Universitat Politècnica de València, València, Spain, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Abraham, A.; Goldberg, R. Evolutionary Multiobjective Optimization: Theoretical Advances and Applications; Advanced Information and Knowledge Processing; Springer: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Coello, C.; Lamont, G.; van Veldhuizen, D. Evolutionary Algorithms for Solving Multi-Objective Problems; Genetic and Evolutionary Computation; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Deb, K. Multi-Objective Optimization Using Evolutionary Algorithms; Wiley Interscience Series in Systems and Optimization; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Deb, K.; Pratap, A.; Agarwal, S.; Meyarivan, T. A fast and elitist multiobjective genetic algorithm: NSGA-II. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2002, 6, 182–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dotro, G.; Langergraber, G.; Molle, P.; Nivala, J.; Puigagut, J.; Stein, O.; Von Sperling, M. Humedales para Tratamiento; Biological Wastewater Treatment Series; IWA Publishing: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Conagua. Manual de Agua Potable, Alcantarillado y Saneamiento Diseño de Plantas de Tratamiento de Aguas Residuales Municipales: Zonas Rurales, Periurbanas y Desarrollos Ecoturísticos; Comisión Nacional del Agua: Mexico City, México, 2024.

- Delgadillo, O.; Camacho, A.; Pérez, L.F.; Andrade, M. Depuración de Aguas Residuales por Medio de Humedales Artificiales; Centro Andino para la Gestión y Uso del Agua (Centro AGUA): Cochabamba, Bolivia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Diaz, A.; Rodriguez, N.; García-Núñez, J.A.; Ruiz Álvarez, E.; Jaime Humberto, A.H.; William Andrés, R.Á. Humedales Artificiales como Alternativa para el Tratamiento Terciario de Efluentes de Planta de Beneficio de Palma de Aceite; CID Palmero: Bogota, Colombia, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal, G.; Hormazábal, S. Humedales Construidos: Diseño y Operación; Universidad de Concepción: Concepción, Chile, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Halverson, N. Review of Constructed Subsurface Flow vs. Surface Flow Wetlands; Technical Report; Savannah River Site (SRS): Aiken, SC, USA, 2004.

- Rincón Santamaría, A. Humedales Construidos para Tratamiento de Aguas Residuales Domésticas y Aguas Ricas en Metales; Centro Editorial Universidad Católica de Manizales: Manizales, Columbia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- MathWorks®. Matlab Online. 2024. Available online: https://la.mathworks.com/products/matlab-online.html (accessed on 17 February 2024).

- Cespedes Pillaca, R.V. Análisis del Uso de Humedales Artificiales Empleando Plantas Macrofitas para el Tratamiento de Aguas Residuales en el Ámbito Rural, Apurímac 2021. Master’s Thesis, Universidad César Vallejo, Trujillo, Peru, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez Velásquez, M. Alternativa de Tratamiento Terciario de Aguas Residuales Mediante Humedal de Flujo Subsuperficial para Reúso Agrícola, Lucanas, Ayacucho, 2021. Master’s Thesis, Universidad Nacional San Luis Gonzaga, Ica, Peru, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Núñez Burga, R.M.F. Tratamiento de Aguas Residuales Domésticas a Nivel Familiar, con Humedales Artificiales de Flujo Subsuperficial Horizontal, Mediante la Especie Macrófita Emergente Cyperus Papyrus (Papiro). Master’s Thesis, Universidad Peruana Unión, Chosica, Peru, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- López-Linares, E.; Rodríguez-Álvarez, M. Evaluación de un Humedal Artificial de Flujo Subsuperficial como Tratamiento de Agua Residual Doméstica en la Vereda Bajos de Yerbabuena en el Municipio de Chía, Cundinamarca. Master’s Thesis, Instituto Tecnológico de Costa Rica Escuela de Ingeniería en Construcción, Cartago, Costa Rica, Universidad de la Salle Facultad de Ingeniería Ambiental y Sanitaria, Bogotá, Colombia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).