Abstract

The variability of rainfall, mainly convective, in the southern Amazon remains poorly understood due to the limited number of studies examining the relationships between the intensities and durations of rainfall events in this region. This study aimed to characterize the intensity patterns—hyetograms (advanced, intermediate, delayed, and constant, as well as observations of new patterns)—in the northern state of Mato Grosso (southern Amazon). Generally, most research in Brazil on this topic has focused on other regions of the country or used simulations or data disaggregation processes, limiting the representation of the regional reality. Historical data series from five conventional stations (with pluviograms) and ten automatic stations with data obtained by tipping rain gauges were analyzed. The analysis involved classifying 6187 events into four main patterns: Advanced (53.52%), Intermediate (31.74%), Delayed (14.58%), and Constant (less than 1%), with 93 events unclassified. The hourly distribution of rainfall revealed greater occurrence in the afternoon and evening periods, suggesting a predominance of thermal convection in regional dynamics. The results offer valuable insights for water planning, agricultural security, and adaptive infrastructure, in addition to promoting integration between science, engineering, and public policies aimed at environmental management and risk prevention.

1. Introduction

The Amazon Rainforest is recognized as one of the main centers of biodiversity on the planet and is essential for ecosystem services [1], such as climate regulation, carbon sequestration [2], conservation of water resources and biodiversity, in addition to maintaining the hydrological cycle on a regional and global scale [3,4].

Although most of the Amazon is located in Brazil, the biome also extends into Bolivia, Colombia, Peru, Venezuela, Ecuador, and Guyana [5,6]. This ecosystem is strongly influenced by the availability of solar radiation and water [7,8] and supports one of the most important hydrological systems on the planet [9,10], making it central to studies on climate change and natural resources. In the state of Mato Grosso, the Amazon interfaces with two other biomes (Cerrado and Pantanal), and, in general, its climatic transition zones reveal patterns similar to those observed in the southern Amazon.

The advancement of climate change has caused significant changes in air temperature, wind, and precipitation patterns, directly affecting societies and ecosystems [11,12,13,14]. Although some of these changes are due to natural phenomena, there is increasing agreement on the role of human activity in amplifying these processes [15,16,17,18]. Precipitation, along with vegetation, is essential for characterizing a region’s climate [19,20,21]. Its formation depends on interactions between air masses and convective, frontal, and orographic processes [22]. Changes in global rainfall patterns directly influence the intensity and duration of events, leading to increased randomness in their spatiotemporal distribution and a rise in the occurrence of floods [23]. Additionally, these changes tend to cause more predictive failures [24].

In the Amazon region, the main differences in seasonal climatic characteristics between summer and winter (rainy and dry, respectively) are associated with the positioning and intensity of upper-level subtropical pressure jets, the meridional displacement of the Hadley cell (in the tropical zone), regional and local convective processes, and the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ). According to Limberger and Silva [25], local tropical convection is the main process of precipitation formation in the Amazon basin, modulated by large-scale circulations such as the Hadley cell, the ITCZ, and the Walker zonal circulation. In addition to these atmospheric dynamics factors, Reboita et al. [26] showed that a portion of the moisture from the Amazon region is transported to the subtropics by the low-level jet (LLJ) east of the Andes, and that significant seasonal effects associated with the surface temperature (SST) of the Equatorial Atlantic and macro-scale (El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO) and mesoscale (high-level anticycle known as the Bolivian High—SA) also occur. Feedback between the local surface and the atmosphere is an important factor contributing to the precipitation anomalies observed in the Amazon, mainly in the Southern or Meridional regions, which correspond to the north and northeast of Mato Grosso. Together, all these factors and phenomena can influence the seasonality and characteristics of rainfall, altering its frequencies, intensities, and distributions [27,28,29,30,31,32,33].

Operationally, conventional rainfall monitoring stations have human observers [34], while automatic stations use digital sensors. When monitored using rain gauge systems (pluviographs) or data acquisition systems (dataloggers), rainfall intensity can be determined based on the ratio of precipitation depth to event duration. These records enable the generation of hyetographs, which are graphs that describe rainfall intensity variations over time [35].

Rainfall hyetographs have proven to be essential tools for analyzing processes such as water erosion, infiltration, runoff, and flood risk. Research in regions such as southern Taiwan [36], China [37,38,39], northeastern Brazil [40], south Malaysia [41], and southwestern Italy [42] shows their effectiveness in understanding rainfall variability and in water management planning, especially in tropical settings subject to climate extremes. In particular, Duan et al. [43] classified natural precipitation events in the humid subtropical monsoon region into four main patterns, showing that these temporal distributions of intensity exert a strong influence on runoff and soil erosion.

Advances in rainfall data collection methods, such as remote sensing methods (weather radar and satellites) and surface radar, which allow for modeling and forecasting (numerical, time series, among other methodologies), still require point measurements (on the ground) for calibration and validation. Consequently, various methods of rainfall data collection provide only total information or rates over time intervals that do not allow for understanding the dynamics of intense rainfall. Although studies on intensity patterns exist in different regions of Brazil, there is still a significant lack of analyses that characterize hyetographs from real rainfall data, especially those focused on the southern portion of the Amazon and, in particular, the Northwest and North regions of Mato Grosso, considered one of the main Brazilian agricultural frontiers. This area stands out for its economic importance, intensive land use for agriculture, and its potential to represent the impacts of climate change and land use in other parts of the Amazon.

Detailed studies on rainfall intensity and its effects on soil and water are still limited, which hampers the ability to identify environmental risks linked to extreme events. Therefore, this study aims to characterize rainfall intensity patterns (hyetograms), durations, and times of occurrence in the Southern Amazon, using measurements from both conventional equipment (pluviograms) and automatic stations with different temporal resolutions of data collection.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

The state of Mato Grosso, located in Brazil’s Central-West region, lies between 6°00′ S and 19°45′ S latitude, and 50°06′ W and 62°45′ W longitude. It covers approximately 903,208 km2, making up 56.2% of the Central-West region and 10.61% of the country’s total land area. It is the third-largest state by land size [44]. Mato Grosso includes three main biomes—Pantanal, Cerrado, and Amazon—and their transition zones, with the Amazon region being the largest. This ecological and climate diversity is closely linked to the strong presence of agribusiness, which fuels the state’s economy [45,46].

According to the Köppen climate classification, Mato Grosso has mainly a humid and subhumid tropical climate (Aw), with average air temperatures exceeding 18 °C throughout the year [47]. In the Center-South, North, Middle-North regions, and parts of the Pantanal, there is a dry season in autumn-winter and a rainy season in spring-summer. Some areas also feature a tropical highland climate (Cwa), with dry winters and temperatures below 18 °C, especially in regions above 800 m in altitude [47]. The climate of Mato Grosso is marked by two clearly defined seasons: the rainy season from October to April and the dry season from May to September. Average annual rainfall ranges from 1200 mm to 2200 mm [48], with higher totals recorded in the northern part of the state [49] and a gradual decrease toward the Central, East, West, and South regions [50,51].

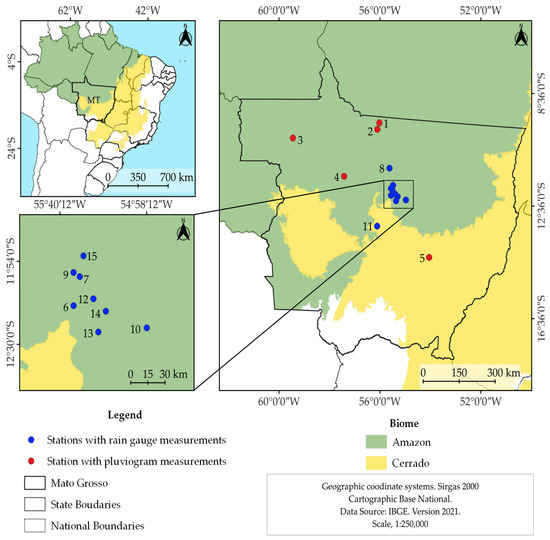

The data used in the study were obtained from two sources: (i) five conventional meteorological stations with rainfall gauges, belonging to the National Hydrometeorological Network (CPRM/ANA), whose pluviograms were provided by the Superintendence of the Geological Survey of Brazil in Manaus-AM; and (ii) ten automatic meteorological stations (Table 1), belonging to the Water Resources Technology in the Central-West research group, of the Federal University of Mato Grosso (UFMT)—Sinop Campus. The stations are located in municipalities in the North (Amazon biome) and Southeast (Amazon-Cerrado transition zone) mesoregions of the state of Mato Grosso, namely: Peixoto de Azevedo, Alta Floresta, Aripuanã, Porto dos Gaúchos, Paranatinga, Sinop, Feliz Natal, Lucas do Rio Verde, Juara, and Vera (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Rainfall gauge and pluviographic stations used to assess rainfall intensities in the State of Mato Grosso, Brazil.

Figure 1.

Location map of the fifteen stations located in the Amazon Basin, Mato Grosso state, Brazil. (Data source: IBGE [44]). Numerical identification according to Table 1.

The rainfall records used in this study cover varying periods, depending on the type and operating period of each meteorological station. For conventional stations, data are available from 2000 to 2012, while automatic stations provide records from 2010 to 2024. This variation reflects the differences in the installation periods and operational continuity of each station. Conventional stations total five units, four of which are located in urban areas. On the other hand, automatic stations total ten units, with three positioned in urban areas and the rest distributed in rural zones, allowing for the capture of broader spatial variations and contrasts between anthropized and natural environments. The exact observation period for each point in the study area is presented in Table 1.

2.2. Data Collection and Processing

The rain gauges from the five conventional stations were digitized, and rainfall intensities were obtained using HidroGraph 1.02 software (Federal University of Viçosa, Viçosa, MG, Brazil) as part of the work of Sabino et al. [16]. This system, developed by the Water Resources Research Group at the Federal University of Viçosa (UFV) for the National Electric Energy Agency (ANEEL), allows for the vectorization of records using digitizing tablets, with a graphical interface similar to that of Windows software. Digitization enabled the extraction of all rainfall events recorded at the Alta Floresta, Porto dos Gaúchos, Peixoto de Azevedo, Paranatinga, and Humboldt stations, without prior limitations on duration or rainfall depth.

After analyzing the consistency and organization of the data, any record separated by at least 60 consecutive minutes without precipitation was considered a new rainfall event, according to the criteria proposed by Sabino et al. [16]. Furthermore, only events lasting at least 30 min or with a precipitation depth greater than 3 mm in 30 min were included in the rain gauge analyses [52].

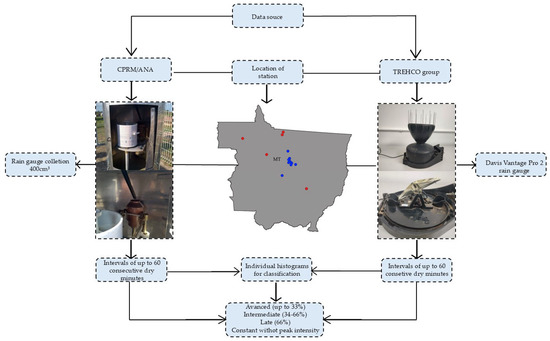

At automatic weather stations operating with recording intervals of five and ten minutes, events lasting less than 15 min were not classified according to intensity patterns. However, they were counted in the total number of natural rainfall events. The criterion for defining a new event was also a 60 min interval without recorded precipitation. All automatic rain gauges used the Davis Vantage Pro 2 model (Davis Company, Hayward, CA, USA) with a resolution of 0.2 mm. Figure 2 represents all the methodological steps developed in the study.

Figure 2.

Flowchart of the methodology used to collect, organize, and measure data and classify natural rainfall intensity patterns. The blue dots indicate the stations with rain gauge measurements from the Water Resources Technology in the Midwest research group at UFMT, while the red dots indicate the stations with pluviogram measurements from the National Hydrometeorological Network (CPRM/ANA).

For each rainfall event, individual histograms were generated, allowing the classification of intensity patterns based on the temporal position of the intensity peak [53,54]: (i) Advanced (AV)—peak rainfall intensity in the first 33% of the total duration of the event; (ii) Intermediate (IN)—peak intensity between 34% and 66% of the total duration of the event; (iii) Delayed (DE)—peak after 66% of the total rainfall time; (iv) Constant (CT)—constant intensity throughout the duration of the event.

Events were also classified according to their duration: <30 min, 30–60 min, 60–120 min, 120–180 min, 180–240 min, and >240 min. Due to the limited resolution of the pluviogram at conventional stations, events lasting less than 30 min were not considered at the five conventional stations. In addition to the traditional typology, the study also evaluated the occurrence of M, W, and inverted U patterns, which have distinct intensity configurations over time. These patterns have previously been investigated in controlled rainfall simulations, such as with the InfiAsper equipment, aiming to reproduce natural rainfall and its effects on erosion processes [55]. Segmenting the data by day and station facilitated the visual and statistical analysis of natural rainfall patterns. It is worth noting that the maintenance and observation of conventional stations require the presence of a human operator and involve high labor costs [56], which can compromise the continuity of the series and the quality of the data.

The analysis of the hourly precipitation distribution was conducted by dividing the occurrence times into 30 min intervals throughout the 24 h day, with time periods grouped as follows: 0–6.0 h (dawn), 6.5–12.0 h (morning), 12.5–18.0 h (afternoon), and 18.5–23.5 h (early evening).

3. Results

3.1. Characterization of Natural Rainfall Patterns

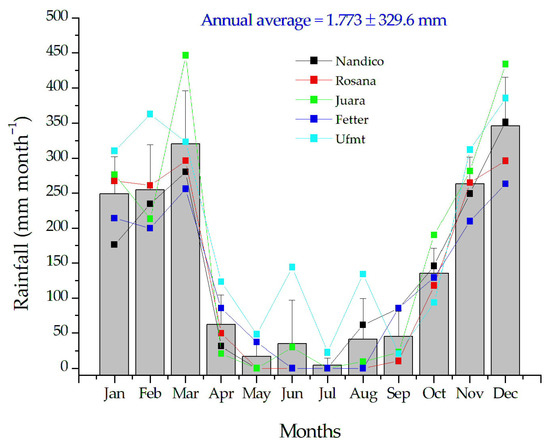

The 15 meteorological stations studied, located in the northern mesoregion of Mato Grosso, showed similar patterns in annual rainfall, despite differences in data collection intervals. The regional climate exhibited a dry season from May to September and a rainy season from December to March (Figure 3), with the highest average monthly rainfall in March (320.4 mm month−1) and December (360.4 mm month−1). The recorded average annual rainfall was 1786.9 mm, confirming the high rainfall characteristic of the northern part of Mato Grosso.

Figure 3.

Monthly averages and standard deviations of rainfall in the southern Amazon region (northern Mato Grosso), considering as reference stations with data measured every 5 min.

The months of November (263.5 mm month−1), January (248.9 mm month−1), and February (254.3 mm month−1) also showed significant rainfall volumes and high standard deviation. In contrast, from May to September, cumulative totals were less than 50 mm month−1. This seasonal variation is typical of tropical regions, where rainfall is intense during periods of peak solar radiation, followed by dry months. Furthermore, analysis of the standard deviation indicates that rainfall events vary between seasons, meaning that even during the rainy season, there is high spatial variability in rainfall, mostly convective.

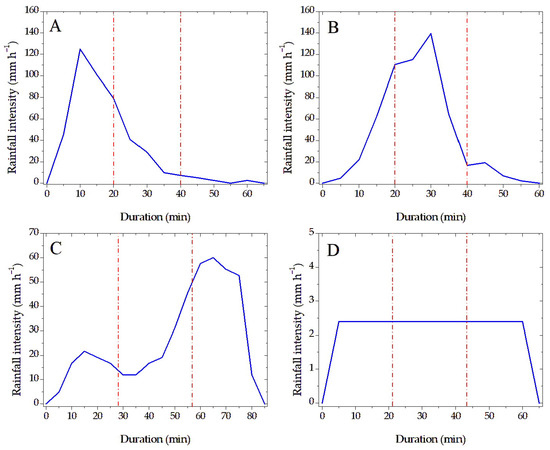

The classification of natural rainfall intensity patterns was based on the distribution of peak rainfall throughout the duration of the events (Figure 4). The analyzed hyetograms showed that events with similar intensities and depths can exhibit different temporal distribution patterns, even when they have the same durations. In Figure 4A, the advanced pattern was depicted by an event with a peak of 120 mm h−1 in the first 10 min. The intermediate pattern (Figure 4B) and the delayed pattern (Figure 4C) displayed maximum peaks of 130 mm h−1 and 60 mm h−1, occurring after 33% and 66% of the duration, at 30 and 55 min, respectively. The Constant pattern (Figure 4D) illustrates a nearly uniform intensity throughout the event.

Figure 4.

Representation of rainfall intensity patterns over the course of the event. (A) Dynamics of the Advanced pattern (Nandico River station 15 March 2022); (B) Dynamics of the Intermediate pattern (Santa Sofia farm station 25 October 2022); (C) Dynamics of the Delayed pattern (Santa Sofia farm station 23 January 2023); (D) Dynamics of the Constant pattern (Nandico River station 28 October 2022). The blue lines represent the precipitation hyetographs, while the red dashed lines indicate the percentage divisions of the total event duration (0–33%, 34–66%, and after 66%).

Rainfall events were characterized based on the minimum duration needed for graphical pattern recognition, which varied depending on the measurement method. Rainfall records from conventional stations had no minimum time limit after digitization; for automatic stations, rainfall events were defined as lasting at least 30 and 20 min for data recorded at 10- and 5 min intervals, respectively, to ensure at least four valid records per event.

A total of 4009 events were analyzed at the five conventional stations, none of which exhibited a Constant pattern (Table 2). At the automatic stations with data collection every 10 min, located in Vera and Lucas do Rio Verde, 1185 events were recorded, with only six classified as Constant (Table 3). At the automatic stations that collect data every 5 min, 993 events were identified, with only four categorized as Constant (Table 4). Rainfall data collected at higher temporal resolutions (shorter intervals) enable greater accuracy in identifying hydrographs (intensity patterns), especially in cases with a Constant distribution.

Table 2.

Number of events (N°) in different patterns of natural rainfall intensity at five conventional stations (measured by pluviograms), in the southern region of the Amazon, Mato Grosso.

Table 3.

Number of events (N°) in different patterns of natural rainfall intensity at automatic meteorological stations (measurements at 10 min intervals), in the municipalities of Vera and Lucas do Rio Verde, Mato Grosso, Brazil.

Table 4.

Number of events (N°) in different natural rainfall intensity patterns at automatic weather stations (measurements at 5 min intervals), in different municipalities in the northern region of Mato Grosso (southern Amazon).

Among the 4009 events collected from the pluviograms, 52.2%, 28.9%, and 18.8% of rainfall events exhibited Advanced, Intermediate, and Delayed patterns, respectively. At stations recording data every 10 min (1185 events), these percentages were 53.1% (AV), 41.8% (IN), and 4.4% (DE). At stations with 5 min recording intervals (993 events), the predominance of the AV pattern (59%) was also observed, followed by the IN (31%) and DLY (9.5%) patterns. When considering the 6187 events analyzed, the AV pattern was the most frequent, accounting for 53.52%, followed by the IN (31.74%), DE (14.58%), and CT (0.16%). It is important to note that the number of rainy days in each meteorological station’s database was not specifically quantified, as days with more than one event were recorded based on the separation interval of rain events. Additionally, only events with rainfall exceeding 6 mm were evaluated.

3.2. Characterization of the Duration of Natural Rainfall

An analysis of rainfall event durations recorded at 15 stations reveals a prevalence of short-duration rainfall in the southern Amazon and northern Mato Grosso (Table 5). About 37.86% of the events (2343 occurrences) lasted longer than 120 min, while 35.72% (2210 occurrences) lasted between 60 and 120 min, indicating that over 73% of the observed rainfall events persisted longer than an hour. For short-duration events, primarily recorded by automatic stations every 5 min, roughly 60.5% of those lasting less than 30 min displayed an IN pattern. This behavior suggests a normal distribution of intensity concentrated in the middle third of the rainfall. A detailed table of event durations by weather station is presented in Appendix A (Table A1).

Table 5.

Number of natural rainfall events (N°) at different duration intervals (in minutes) and rainfall intensity patterns, at the 15 stations evaluated, in Mato Grosso, Brazil. (N = 6187).

Three precipitation events exceeding 1000 min were observed at the São José Farm station, with total depths of 58.31 mm, 62.55 mm, and 88.28 mm, all classified as Advanced. Additionally, 68 events lasting longer than 400 min were recorded at the Fetter Farm (14 events), São José Farm (20 events), Vô Maria Farm (12 events), UFMT (10 events), Empaer (1 event), Santa Sofia Farm (2 events), Nandico River (4 events), Rosana Stream (2 events), and Bragança Farm (3 events) stations. This prolonged rainfall behavior sets the studied region apart from other parts of Mato Grosso, where events lasting longer than 360 min are uncommon [57,58].

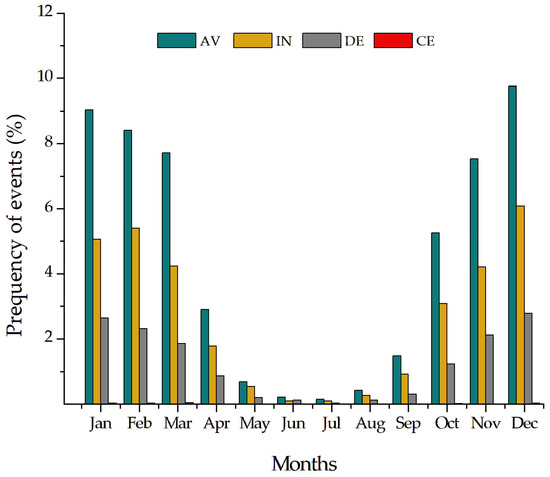

Regardless of the month, more AV rainfall events occurred throughout the year, with 466 (7.53%), 604 (9.76%), 559 (9.03%), 520 (8.40%), and 477 (7.71%) events observed from November to March, respectively (Figure 5). Furthermore, during the evaluated period, there is no linear relationship between the number of events in each pattern and the average monthly rainfall volumes (Figure 5), as January shows a high number of events (when analyzing the same intensity pattern). However, the average total rainfall volume in January is lower than that in February and March (Figure 3 and Figure 5). In addition, a relative increase in IN pattern events is observed in December and February, periods characterized by high soil saturation (Figure 5). Souza et al. [47] observed that, in this region (data period from 1972 to 2012), December and February are the rainiest months, making this behavior consistent with the literature, which links the increased frequency of IN events to convective processes intensified by soil water saturation [59]. These processes, in turn, exhibit environmental effects that differ from those observed in December, due to the water content already stored in the soil from previous months.

Figure 5.

Monthly frequency distribution of natural rainfall intensity patterns. (N = 6187).

Analysis of the relationship between rainfall patterns shows that, on average, there are 1.7 to 3.8 AV events for each IN and DE event, respectively. This trend reinforces the role of AV events in runoff dynamics [53,59] and soil erosion potential [60,61].

The highest rainfall intensities observed are mainly associated with events classified as AV (Table 6), indicating more concentrated rainfall during the first 33% of the total event duration. Additionally, 66.66% of these high-intensity events lasted longer than 120 min, suggesting that, despite the initial peak, these rainfall events continue even as the intensity diminishes afterward. The elevated intensities in some events can be attributed to moisture buildup in the atmosphere, characteristic of convective ascent of moist air masses, which can produce clouds with significant vertical development (cumulonimbus type—Cb), depending on adiabatic gradients and condensation levels. Notably, three of these events had average intensities of 1.8, 1.64 and 2.5 mm min−1, exceeding the critical intensities for hydro-agricultural and urban projects in this region, which for a 10-year return period is set at 1.25 mm min−1 [16].

Table 6.

Maximum (Imax) and average (Iavg) rainfall intensity recorded at each of the 15 stations evaluated in the Southern Amazon (event date, time, duration, precipitation depth, and pattern).

Furthermore, the peak intensities observed at certain times during these events raise concerns about water and soil conservation in the region, as they are directly related to water infiltration capacity. According to Moratelli et al. [62], surface soils in watersheds within this region, when covered by crops or pastures, have saturated hydraulic conductivity (K0) below 94.7 mm h−1; for comparison, under native vegetation conditions (forests), K0 values can range from 500 to 950 mm h−1, depending on the level of human activity or forestry exploitation.

Because of the difference in measurement intervals (data storage) at the automatic stations of 5 and 10 min, it was possible to verify that in 93 short-duration rainfall events, it was not possible to determine intensity patterns (Table 7), even with precipitation levels greater than 3.0 mm.

Table 7.

Rainfall events without intensity patterns are characterized by the limited measurement time interval.

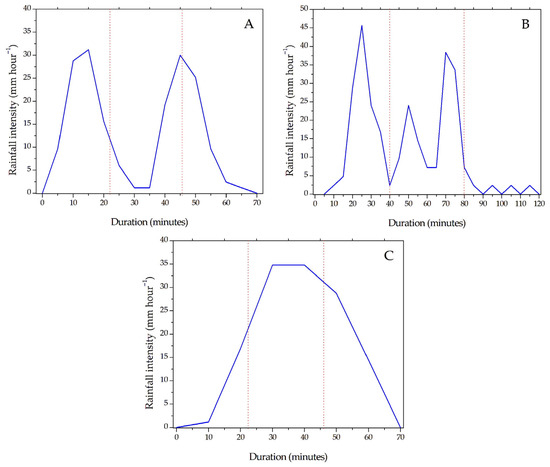

Apart from the cases already mentioned, 137 rainfall events were recorded that exhibited variations in precipitation intensity different from the four patterns usually described in the literature (Figure 6 and Table 8). These patterns appeared regardless of whether measurements were taken with traditional pluviograms (conventional stations) or tipping rainfall gauges equipped with dataloggers (automatic stations). They were labeled as “M,” “W,” and “inverted U” patterns. It is important to highlight that the “M” and “inverted U” patterns occur more frequently than those with the CT pattern.

Figure 6.

Illustration of the dynamics of new rainfall intensity patterns observed in the southern Amazon region: M pattern (A) (Empaer station 30 October 2024); W pattern (B) (Nandico River station 29 January 2022); and inverted U pattern (C) (Fetter Farm station 08 December 2018). The blue lines represent the precipitation hyetographs, while the red dashed lines indicate the percentage divisions of the total event duration (0–33%, 34–66%, and after 66%).

Table 8.

Frequency and overall distribution of M, W, and inverted U rainfall patterns at meteorological stations in the southern Amazon region.

The “M” pattern shows two similar intensity peaks with a decrease in intensity at the mean rainfall time (Figure 6A). In the case of the “W” pattern (Figure 6B), the data indicate three intensity peaks at 25, 50, and 70 min, with values of 45, 25 and 35 mm h−1, respectively. These events differ from more traditional intensity distribution patterns, as the moments of greatest precipitation are not focused in a single point of the event [63,64,65], reflecting a more complex and fragmented rainfall distribution over time and with different impacts on the infiltration and runoff components of the soil, especially on erosion processes.

The dynamics seen in the inverted-U pattern (Figure 6C) display a symmetrical intensity curve, with the peak positioned around the middle of the event. Unlike the IN pattern, this type of rainfall does not show a single, isolated peak in the average rainfall duration but instead features a prolonged period between 40 and 60% of the rainfall duration, with stable intensity levels, before it starts to decline. A clear central maximum peak defines the IN pattern examined in this study (Figure 4B).

The frequency and spatial distribution of these rainfall patterns (Table 8) show that the UFMT station (in Sinop, Mato Grosso) had the highest occurrence of the M pattern, with 18 records, representing 18.55% of the events of this type. In contrast, the W and inverted U patterns occurred less frequently. The analysis of these patterns reinforces the complexity of the rainfall regime in the southern Amazon. It highlights the importance of considering its spatiotemporal variations in forecast models and hydrological studies aimed at managing extreme events.

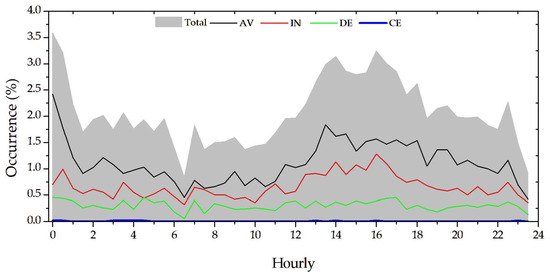

3.3. Hourly Distribution of Precipitation

Based on this, the results show that the highest number of rainfall events occurs in the afternoon and nighttime, accounting for 54.16% (3351 events) (Table 9), with a focus on the period from 12.5 to 18.0 h, which accounts for 33.65% of the events. The interval from 18.5 to 23.5 h recorded 20.51% (Table 9).

Table 9.

Relative frequency (FR; %) of precipitation by periods: dawn (0–6 h), morning (6.5–12 h), afternoon (12.5–18 h), night (18.5–23.5 h) at the stations analyzed.

Furthermore, the hourly distribution of rainfall events across the four patterns analyzed was examined (Figure 7). The AV pattern showed more events between 12.5 and 18.0 h (33.59%) and from 0.0 to 6.0 h (28.18%), indicating afternoon and nighttime activity, with higher percentages occurring between 13.0 and 13.5 h (114 events, representing 1.8426% of all evaluated events). For the IN pattern, events mainly clustered between 12.5 and 17.5 h (616 events or 9.96%), with the highest percentage at 1.2769% (79 rains). The DE pattern displayed a more evenly distributed frequency of occurrences throughout the day.

Figure 7.

Percentage of natural rainfall occurrence with different intensity patterns throughout the day in the southern Amazon region. (Total number = 6187).

The diurnal evolution of total occurrences and AV and IN patterns reinforces the effects of convective and mesoscale systems on rainfall in the region [66]. These systems are associated with increased water vapor concentration (air humidity) during the morning and afternoon periods due to evapotranspiration, combined with reduced air temperature and water vapor saturation pressure in the afternoon and early evening, which generate conditions closer to saturation/condensation in the humid air mass. Therefore, this behavior demonstrates a lagged and non-symmetrical cyclical relationship, which is associated with the convergence of atmospheric moisture induced by low-altitude winds.

4. Discussion

Some rainfall events were extremely brief, making it impossible to identify intensity patterns. However, they are significant because they contribute to the water supply for agroecosystems; these rainfall events totaled 93 instances recorded at four different automatic weather stations, with measurement intervals of 5 and 10 min.

A significant predominance of rainfall events with the AV pattern was observed (Figure 6 and Figure 7), accounting for 53.52% of the evaluated events (3311 occurrences). This pattern is most common in December, January, and February, which together make up 50.83% of the annual rainfall. In addition to the risks associated with rainfall, this period coincides with the development and harvest of soybeans or the early growth stages of crops such as corn and cotton [67], which are the main crops grown in the region during this time. In this context, low soil cover rates (due to low leaf area indices), combined with rainfall, increase erosion in agricultural areas [61]. The connection between heavy rainfall and moisture-saturated soils, accumulated throughout the year, also heightens the risk of degradation in agricultural lands [68]. Rainfall in October and November tends to boost soil moisture, recharging water storage levels close to the available water capacity (AWC). As a result, initial soil water infiltration rates are lower, which would not reduce the impacts of peak rainfall intensity associated with an AV pattern.

Rainfall with IN and DE pattern characteristics typically causes greater soil and water losses because peak intensity occurs when the soil is already saturated or has stable infiltration rates [69]. In contrast, rainfall with the CT pattern results in lower water and soil losses [55], depending on the precipitation depth. Studies using rainfall simulators with constant patterns are most common in Brazil, highlighted by recent work from Almeida et al. [70], Marques et al. [71], Fan et al. [72], Alves et al. [73], Luz et al. [74], and Oliveira et al. [75]. These pattern studies remain important for defining infiltration equations, erodibility, and the impact of soil cover and management on erosion. However, this work shows that natural rainfall with CT intensity occurs less than 1%, making experiments with only this pattern less representative and less applicable for hydro-agricultural simulations and modeling [53,65].

The IN pattern, accounting for 31.74% of total events, shows a more even distribution throughout the year. This pattern also promotes increased soil moisture, creating favorable conditions for erosion [53], especially at the end of the rainy season. Although less common than the AV pattern, IN rainfall still has significant effects on agricultural management, particularly in areas where the soil is already moist [54,74,76]. Conversely, the DE pattern occurred in 14.58% of the evaluated events; this rainfall pattern influences the water balance and should not be overlooked. The DE pattern, though less frequent, is potentially more erosive compared to other patterns, mainly because it occurs more often from December to February, when the soil already has high moisture levels from previous rains [69,77,78].

Rainfall patterns with the AV pattern pose a lower potential risk in agriculture compared to the IN and DE patterns [69,78]. Risks increase with higher recurrence frequency, especially after a period of high soil moisture. The first quarter of the year follows a saturation period, as rainfall in the region intensifies from the third ten days of October onward. By this point, the soil is already saturated with moisture, and the increased frequency and intensity of rainfall later amplify risks in land used for agriculture. Different rainfall patterns can cause variations in peak soil and water loss during events, depending on rainfall intensity. While a temporary reduction in intensity might briefly lower erosion rates, soils that are already saturated become more vulnerable when rainfall intensifies again [69,72]. These fluctuations impact infiltration capacity and, thus, runoff volume [79]. During high-intensity events, runoff is more likely to increase, especially when rainfall exceeds the soil’s infiltration capacity, leading to surface water accumulation and runoff along the topographic gradient, influenced by LS factors—slope length and slope [60]. Additionally, intense rainfall often results in soil surface sealing, which reduces infiltration rates and causes greater water losses [79].

On the other hand, in the urban dynamics of cities, the Advanced pattern has implications for infrastructure [55] and the daily lives of population, since this rainfall pattern, which intensifies rapidly at the start of the event, overloads urban drainage systems that are often inadequate to handle sudden water volumes, leading to flooding, inundations, and landslides [72].

Local climatic conditions, such as the interaction between atmospheric currents and land use characteristics [80], can contribute to the formation of microclimates that potentially influence the frequency and intensity of rainfall. In heated urban surfaces, can modular convective processes intensify, leading to more intense rainfall. In contrast, areas with abundant vegetation maintain high humidity levels through evapotranspiration, which favors more frequent rainfall. In deforested regions, however, these events tend to decrease due to reduced moisture availability. The predominance of the AV pattern in December, January, and February reflects the region’s seasonality, marked by the transition between dry and rainy seasons. However, regional factors, such as deforestation and land conversion for agriculture [81], can alter this seasonality [82], amplifying rainfall during critical periods for agriculture or natural resource extraction. This dynamic demonstrates a feedback loop between land use changes and precipitation patterns [83,84], creating risks for both agriculture and environmental conservation. These vulnerabilities are likely to worsen, as climate projections indicate an increased frequency of extreme events in Brazil, including heavy rainfall, heat waves, and droughts, in interaction with demographic and land use factors [85,86].

Rising global temperatures alter the hydrological cycle [87] and tend to increase local pressure gradients (variations in atmospheric pressure), intensifying air movement and the dynamics of convective processes, resulting in more intense and irregular rainfall, which may explain the prevalence of the Advanced pattern. Atmospheric warming also tends to intensify evapotranspiration [88] and, consequently, increase the concentration of water vapor in the atmosphere [89,90,91], leading to more concentrated and intense rainfall in short periods. In the Amazon, the synergy between climate change and forest degradation can amplify the effects of extreme rainfall events, especially regarding the M and W patterns, which present multiple peaks of intensity throughout the event. The significant number of M-pattern records suggests a local predominance of rainfall with multiple peaks, possibly due to the fact that this station is located within the municipality’s urban perimeter. This may reflect greater atmospheric variability at low altitudes due to differences in absorption and reflection of solar radiation, and consequently, greater pressure gradients for the movement and ascent of humid air. The heterogeneity in the distribution of the M-pattern compared to the less frequent W and inverted U-patterns suggests that rainfall formation processes in the region are influenced by local factors such as topography and land cover.

The concentration of rainfall in the afternoon and evening may be caused by thermodynamic and atmospheric factors typical of the region. High temperatures throughout the day promote the evaporation of moisture in the soil and vegetation, increasing local humidity. This process encourages the rise of warm, humid air masses, leading to convective phenomena and the formation of cumulonimbus clouds [92,93]. Additionally, during episodes of the South Atlantic Convergence Zone (SACZ) in the southern Amazon region, rainfall amounts increase as moist winds from the Amazon meet winds from the South Atlantic Ocean, potentially leading to high-intensity rainfall [94,95]. The SACZ is created when moist winds from the Amazon collide with winds from the South Atlantic Ocean.

In agriculture, the concentration of rainfall at night can be beneficial by reducing daytime evapotranspiration and decreasing heat stress on plant water absorption due to the absence of solar radiation. These conditions promote soil moisture retention and benefit crops such as soybeans and corn. However, in urban areas, concentrated rainfall in the late afternoon negatively impacts urban mobility and, in turn, can cause flooding in areas with poor infrastructure.

The temporal resolution between measurement intervals at meteorological stations is a crucial factor in characterizing rainfall intensity patterns. It has been observed that the measurement resolution influences how precipitation events are classified, with 5 min intervals capturing intensity variations more accurately than 10 min intervals. For example, events initially classified as AV at stations with 5 min measurements, when analyzed at 10 min intervals, can be reclassified as IN. The lack of standardization in measurement intervals at meteorological stations, which range between 5 and 10 min, is significant for analyzing short-duration intense rainfall events. It was observed that, in the region, events lasting less than 30 min occur; therefore, only 10 min intervals would be insufficient to identify rainfall patterns accurately. This change occurs because increasing the measurement interval tends to smooth out intensity fluctuations, leading to uncertainty in detecting peaks. For comparison, changing the measurement interval to 10 min at automatic stations that record data every 5 min results in changes in rainfall patterns across all stations (Table 10).

Table 10.

Variation in rainfall intensity patterns caused by shifting the data recording interval from 5 to 10 min at meteorological stations.

These changes in precipitation patterns would account for 3.62% (224 events) of the recorded rainfall totals. The patterns changed from Advanced to Intermediate and from Intermediate to Delayed, indicating that this shorter timeframe results in a higher percentage of potentially more damaging rainfall patterns.

5. Conclusions

In the northern region of Mato Grosso, belonging to the southern portion of the Amazon, rainfall with an Advanced Intensity Pattern (AV) predominates, accounting for 53.52% of the analyzed events (3311 records). The Intermediate Pattern (IN) and the Delayed Pattern (DE) represented, respectively, 31.74% (1964 events) and 14.58% (902 events) of the total. Events with a Constant Intensity Pattern (CT), commonly used in simulated rainfall experiments, were observed in only 0.16% of cases (10 events), highlighting their limited relevance for the region’s natural precipitation analysis. Additionally, it was observed that 62.13% of the rainfall lasted up to 120 min. Other types of temporal patterns, such as the M, W, and inverted U shapes, were also identified, with the M pattern being more frequent in urban areas—likely influenced by the specific period of data collection. The hourly distribution of rainfall showed higher occurrences in the afternoon and early evening, indicating a dominance of rainfall caused by local convection, triggered by surface heating during the day.

Stations recording rainfall every 5 min showed better accuracy in detecting variations than stations with a 10 min interval. This led to 3.62% of the events (224 out of 6187) being reclassified from the AV pattern to the IN pattern.

The predominance of advanced rainfall patterns and the significant presence of IN and DE patterns (accounting for 46.32% of the total) pose significant challenges for urban planning and water and soil conservation engineering.

These results offer a detailed view of how rainfall intensity evolves throughout the events in the study area. The predominance of the advanced pattern identified in northern Mato Grosso, in the southern Amazon, enhances the current understanding of the natural behavior of precipitation. This evidence can provide practical parameters for future hydrological modeling and soil conservation studies, contributing to more realistic representations of rainfall processes in the region. Furthermore, the results reinforce the need to develop infrastructure adapted to regional climatic conditions, in order to reduce socio-environmental vulnerability and contribute to sustainable development.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: A.P.d.S.; Data collection, D.R.B., A.P.d.S. and F.T.d.A.; Methodology, B.B. and A.P.d.S.; Software, B.B., D.R.B. and A.P.d.S.; Validation, B.B., D.R.B., A.P.d.S. and F.T.d.A.; Formal Analysis, B.B., D.R.B. and A.P.d.S.; Resources, F.T.d.A. and A.P.d.S.; Data curation, A.P.d.S.; Writing (oringal draft preparation), B.B. and D.R.B.; Writing (revision and editing), D.R.B. and A.P.d.S.; Visualization, F.T.d.A.; Supervision, D.R.B. and A.P.d.S.; Project administration, A.P.d.S.; Funding aquisiton, F.T.d.A. and A.P.d.S.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was financed by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior—Brazil (Capes—Process: 88887.946681/2024-00 by the POSDOC grant for the author D.R.B.) and 3 Comarca do Ministério Público do Estado de Mato Grosso (Bapre/MPMT/Sinop). The Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq) by the productivity grant for the corresponding author (Process 303522/2022-4).

Data Availability Statement

Study data can be obtained upon request to the corresponding author via e-mail. The data are unavailable on the website as the research project is still being developed.

Acknowledgments

The authors also thank all the students of the Tecnologia em Recursos Hídricos no Centro-Oeste” research group (http://dgp.cnpq.br/dgp/espelhogrupo/2399343537529589, accessed on 29 September 2025). The authors would also like to thank the owners of the farms that allowed and supported the collection of samples, the MPMT (Comarca of the Sinop), Agência Nacional de Águas e Saneamento Básico (ANA/Brazil) and Serviço Geológico Brasileiro (CPRM/SGB/Brazil).

Conflicts of Interest

The funders had no role in the study’s design, data collection, analysis, or interpretation, manuscript writing, or decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

| ENSO | El Niño-Southern Oscillation |

| IBGE | Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics |

| CPRM | Geological Survey of Brazil |

| ANA | National Water and Basic Sanitation Agency |

| TREHCO | Water Resources Technology in the Midwest |

| UFV | Federal University of Viçosa |

| ANEEL | National Electric Energy Agency |

| UFMT | Federal University of Mato Grosso |

| AV | Advanced |

| IN | Intermediate |

| DE | Delayed |

| CTE | Constant |

| SACZ | South Atlantic Convergence Zone |

| AWC | Available Water Capacity |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Occurrence of rainfall intensity patterns as a function of rainfall duration, at 15 stations, Mato Grosso, Brazil. (number = 6187).

Table A1.

Occurrence of rainfall intensity patterns as a function of rainfall duration, at 15 stations, Mato Grosso, Brazil. (number = 6187).

| Station Name | Patterns | <30 min | 30–60 min | 60–120 min | 120–180 min | 180–240 min | >240 min | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Porto dos Gaúchos | AV | - | 99 | 184 | 101 | 54 | 53 | 491 |

| IN | - | 34 | 54 | 31 | 17 | 16 | 152 | |

| DE | - | 78 | 76 | 30 | 21 | 21 | 226 | |

| CT | - | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Alta Floresta | AV | - | 77 | 184 | 108 | 66 | 51 | 486 |

| IN | 92 | 120 | 39 | 27 | 18 | 296 | ||

| DE | - | 44 | 73 | 35 | 8 | 7 | 167 | |

| CT | - | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Humboldt | AV | - | 93 | 154 | 79 | 45 | 25 | 396 |

| IN | - | 85 | 86 | 29 | 22 | 11 | 233 | |

| DE | - | 51 | 74 | 28 | 10 | 7 | 170 | |

| CT | - | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Jusante Foz Peixoto de Azevedo | AV | - | 53 | 103 | 72 | 38 | 48 | 314 |

| IN | - | 45 | 86 | 39 | 13 | 17 | 200 | |

| DE | - | 29 | 58 | 28 | 10 | 17 | 142 | |

| CT | - | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Paranatinga | AV | - | 88 | 164 | 71 | 45 | 40 | 408 |

| IN | - | 60 | 73 | 33 | 14 | 25 | 205 | |

| DE | - | 39 | 41 | 25 | 12 | 6 | 123 | |

| CT | - | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Nandico River | AV | - | 28 | 34 | 9 | 9 | 10 | 90 |

| IN | - | 17 | 9 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 30 | |

| DE | - | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 10 | |

| CT | - | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Rosana Stream | AV | - | 26 | 17 | 13 | 8 | 13 | 77 |

| IN | - | 15 | 13 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 35 | |

| DE | - | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | |

| CT | - | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Santa Sofia Farm | AV | - | 27 | 27 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 87 |

| IN | - | 23 | 7 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 36 | |

| DE | - | 3 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 7 | |

| CT | - | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | |

| Empaer | AV | - | 15 | 28 | 16 | 9 | 12 | 80 |

| IN | - | 18 | 17 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 41 | |

| DE | - | 3 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | |

| CT | - | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Faz. Bragança | AV | - | 7 | 10 | 7 | 4 | 8 | 36 |

| IN | - | 11 | 11 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 30 | |

| DE | - | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | |

| CT | - | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Feliz Natal | AV | - | 18 | 16 | 8 | 4 | 9 | 55 |

| IN | - | 7 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 15 | |

| DE | - | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| CT | - | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Fetter | AV | - | 23 | 65 | 41 | 27 | 34 | 190 |

| IN | - | 71 | 40 | 24 | 9 | 14 | 158 | |

| DE | - | 7 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 15 | |

| CT | - | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| UFMT | AV | 11 | 52 | 62 | 27 | 16 | 29 | 197 |

| IN | 23 | 53 | 44 | 14 | 4 | 13 | 151 | |

| DE | 4 | 27 | 18 | 7 | 5 | 7 | 68 | |

| CT | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Vô Maria Farm | AV | - | 31 | 69 | 43 | 25 | 40 | 208 |

| IN | - | 75 | 52 | 20 | 17 | 15 | 179 | |

| DE | - | 8 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 21 | |

| CT | - | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| São José Farm | AV | - | 14 | 58 | 36 | 33 | 55 | 196 |

| IN | - | 43 | 48 | 22 | 6 | 10 | 129 | |

| DE | - | 4 | 7 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 15 | |

| CT | - | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 5 |

References

- Nerfa, L.; Rhemtulla, J.M.; Zerriffi, H. Forest dependence is more than forest income: Development of a new index of forest product collection and livelihood resources. World Dev. 2020, 125, 104689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Londres, M.; Schmink, M.; Böner, J.; Duchelle, A.E.; Frey, G.P. Multidimensional forests: Complexity of forest-based values and livelihoods across Amazonian socio-cultural and geopolitical contexts. World Dev. 2023, 165, 106200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza, C.A.; Junior Oliveira, E.S.; de Hacon, S.S. Ecosystem services in the Brazilian Amazon. Rev. Bras. Geogr. Física 2024, 17, 178–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal Filho, W.; Dinis, M.A.P.; Canova, M.A.; Cataldi, M.; da Costa, G.A.S.; Enrich-Prast, A.; Symeonakis, E.; Brearley, F.Q. Managing ecosystem services in the Brazilian Amazon: The influence of deforestation and forest degradation in the world’s largest rain forest. Geosci. Lett. 2025, 12, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisch, G.; Marengo, J.A.; Nobre, C.A. The climate of Amazonia—A review. Acta Amaz. 1998, 28, 101–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Portella, D.A.P.C.; de Blanco, L.S.; de Mello Filho, M.E.T.; dos Santos, J.L.A. The importance of the Amazon in the climate dynamics of central-southern Brazil: Influence on environmental and socioeconomic dynamics. Ens. Geogr. 2022, 9, 66–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, L.D.S.; de Cruz, M.S.; Coelho, R. Analysis of the daily and annual average of solar radiation incidence and measurements related to air humidity in the year 2021 in Novo Repartimento–Pará. Rev. Bras. Geogr. Física 2024, 17, 117–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martim, C.C.; de Souza, A.P. Estimates of global radiation based on insolation in the Brazilian Amazon. Rev. Ibero Am. Ciênc. Ambient. 2021, 12, 233–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artaxo, P.; Rizzo, L.V.; Brito, J.F.; Barbosa, H.M.J.; Arana, A.; Sena, E.T.; Cirino, G.G.; Bastos, W.; Martine, S.T.; Andreae, M.O. Atmospheric aerosols in Amazonia and land use change: From natural biogenic to biomass burning conditions. Faraday Discuss. 2013, 165, 203–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artaxo, P.; da Silva Dias, M.A.F.; Nagy, L.; Luizão, F.J.; da Cunha, H.B.; Quesada, C.A.N.; Krusche, A. Research perspectives on the relationship between climate and the functioning of the Amazon rainforest. Ciênc. Cult. 2014, 66, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hoegh-Guldberg, O.; Jacob, D.; Taylor, M.; Bolaños, T.G.; Bindi, M.; Brown, S.; Camilloni, I.A.; Diedhiou, A.; Djalante, R.; Ebi, K.; et al. The human imperative of stabilizing global climate change at 1.5 °C. Science 2019, 365, eaaw6974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Myhre, G.; Alterskjær, K.; Stjern, C.W.; Hodnebrog, Ø.; Marelle, L.; Samset, B.H.; Sillmann, J.; Schaller, N.; Fischer, E.; Schulz, M.; et al. Frequency of extreme precipitation increases extensively with event rareness under global warming. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 16063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papalexiou, S.M.; Montanari, A. Global and Regional Increase of Precipitation Extremes Under Global Warming. Water Resour. Res. 2019, 55, 4901–4914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabari, H. Climate change impact on flood and extreme precipitation increases with water availability. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 13768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, W.; de Souza, A.P.; Sabino, M. Indexes of extreme air temperature in the Brazilian Amazon. Confins 2021, 52, 41520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabino, M.; de Souza, A.P.; Uliana, E.M.; Lisboa, L.; de Almeida, F.T.; Zolin, C.A. Intensity-duration-frequency of maximum rainfall in Mato Grosso State. Ambiente Água Interdiscip. J. Appl. Sci. 2020, 15, e2373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, W.; Kumar, S.V.; Zhao, L. Anthropogenic influences on the water cycle amplify uncertainty in drought assessments. One Earth 2025, 8, 101196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusunok, S.; Mizuta, R.; Hosaka, M. Emergence of anthropogenic precipitation changes in a future warmer climate. Clim. Atmos. Sci. 2025, 8, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bresciani, C.; Boiaski, N.T.; Ferraz, S.E.T.; Rosso, F.V.; Portalanza, D.; de Souza, D.C.; Kubota, P.Y.; Herdies, D.L. Brazilian Annual Precipitation Analysis Simulated by the Brazilian Atmospheric Global Model. Water 2023, 15, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Rocha, F.P.; Silva, W.L.; Ribeiro, B.Z. Synoptic Analysis of a Period with Above-normal Precipitation during the Dry Season in Southeastern Brazil. Adv. Res. 2019, 19, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, A.M.; Rocha, E.J.P.; Vitorino, M.I.; Souza, P.J.O.P.; Botelho, M.N. Spatio-temporal Variability of Precipitation in the Amazon during ENOS Events. Rev. Bras. Geogr. Física 2015, 8, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, J.T.; Orville, H.A. Radar Climatology of Summertime Convective Clouds in the Black Hills. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 1973, 12, 359–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wdowinski, S.; Bray, R.; Kirtman, B.P.; Wu, Z. Increasing flooding hazard in coastal communities due to rising sea level: Case study of Miami Beach, Florida. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2016, 126, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabari, H.; Hosseinzadehtalaei, P.; Aghakouchak, A.; Willems, P. Latitudinal heterogeneity and hotspots of uncertainty in projected extreme precipitation. Environ. Res. Lett. 2019, 14, 124032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limberger, L.; Silva, M.E.S. Precipitation in the Amazon Basin and its connection to surface temperature variability of Pacific and Atlantic oceans: A review. Geousp Espaço Tempo 2016, 20, 657–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reboita, M.S.; Gan, M.A.; Rocha, R.P.; Ambrizzi, T. Precipitation regimes in South America: A bibliography review. Rev. Bras. Meteorol. 2010, 25, 185–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AghaKouchak, A.; Chiang, F.; Huning, L.S.; Love, C.A.; Mallakpour, I.; Mazdiyasni, O.; Moftakhari, H.; Papalexiou, S.M.; Ragno, E.; Sadegh, M. Climate Extremes and Compound Hazards in a Warming World. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 2020, 48, 519–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, D.F.F.; Pessoa, F.C.L. Homogeneous regions of precipitation trends across the Amazon River Basin, determined from the Global Precipitation Climatology Centre—GPCC. Rev. Bras. Geogr. Física 2024, 17, 1283–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lira, B.R.P.; Fernandes, L.L.; Ishihara, J.H. Pluviometric behavior and trends in the Legal Amazon from 1986 to 2015. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2022, 150, 1353–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moura, M.M.; dos Santos, A.R.; Pezzopane, J.E.M.; Alexandre, R.S.; da Silva, S.F.; Pimentel, S.M.; de Andrade, M.S.S.; Silva, F.G.R.; Branco, E.R.F.; Moreira, T.R.; et al. Relation of El Niño and La Niña phenomena to precipitation, evapotranspiration and temperature in the Amazon basin. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 651, 1639–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paredes-Trejo, F.; Barbosa, H.A.; Giovannettone, J.; Lakshmi Kumar, T.V.; Thakur, M.K.; de Buriti, C.O. Long-Term Spatiotemporal Variation of Droughts in the Amazon River Basin. Water 2021, 13, 351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, C.A.G.; dos Santos, D.C.; Neto, R.M.B.; de Oliveira, G.; dos Santos, C.A.C.; da Silva, R.M. Analyzing the impact of ocean-atmosphere teleconnections on rainfall variability in the Brazilian Legal Amazon via the Rainfall Anomaly Index (RAI). Atmos. Res. 2024, 307, 107483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Shi, P.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, J.; Wu, J.; Chen, D. Evolution of future precipitation extremes: Viewpoint of climate change classification. Int. J. Climatol. 2022, 42, 1220–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valík, A.; Brázdil, R.; Zahradníček, P.; Tolasz, R.; Fiala, R. Precipitation measurements by manual and automatic rain gauges and their influence on homogeneity of long-term precipitation series. Int. J. Climatol. 2021, 41, E2537–E2552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Abreu, F.G.; Angelini Sobrinha, L.; Brandão, J.L.B. The analysis of the time distribution of rainfall in heavy storms. Eng. Sanitária Ambient. 2017, 22, 239–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, N.; Tai, A.; Chiang, S.; Wei, H.P.; Su, Y.F.; Cheng, C.T.; Kitoh, A. Hydrological Flood Simulation Using a Design Hyetograph Created from Extreme Weather Data of a High-Resolution Atmospheric General Circulation Model. Water 2014, 6, 345–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Tian, Y.; Zhang, S.; Li, Y.; Guo, Z. Study of Urban Flooding Response under Superstandard Conditions. Water 2023, 15, 1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Jiang, P.; Zhang, R.; Zhao, J.; Si, W.; Fang, Y.; Zhang, N. The changing precipitation storm properties under future climate change. Hydrol. Res. 2023, 54, 580–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Guangyao, G.; Liu, J.; Dunkerley, D.; Fu, B. Runoof and soil loss responses of restoration vegetation under natural rainfall patterns in the Loess Plateau of China: The role of rainfall intensity fluctuation. Catena 2023, 225, 107013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chimene, C.A.; Campos, J.N.B. The design flood under two approaches: Synthetic storm hyetograph and observed storm hyetograph. J. Appl. Water Eng. Res. 2020, 8, 171–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusof, F.; Nojumuddin, N.S.; Yusop, Z. Identification of rainfall temporal patterns. In Proceedings of the International Postgraduate Conference (ISPC), Rostov-na-Donu, Russia, 22–24 May 2014; pp. 859–887. [Google Scholar]

- Candela, A.; Brigandì, G.; Aronica, G.T. Estimation of synthetic flood design hydrographs using a distributed rainfall–runoff model coupled with a copula-based single storm rainfall generator. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2014, 14, 1819–1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, J.; Zheng, H.; Wang, L.; Liu, Y.; Mo, M.; Yang, J. Rainfall intensity profile induce changes in surface-subsurface flow and soil loss as influenced by surface cover type: A long-term in situ field study. Int. Soil Water Conserv. Res. 2025, 13, 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBGE (Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics). State of Mato Grosso: Database by State. 2024; p. 1. Available online: https://www.ibge.gov.br/cidades-e-estados/mt.html (accessed on 14 May 2024).

- Gusso, A.; Ducati, J.R.; Bortolotto, V.C. Analysis of soybean cropland expansion in the southern Brazilian Amazon and its relation to economic drivers. Acta Amaz. 2017, 47, 281–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, N.G. Sustainable development index of municipalities in Mato Grosso. Rev. Bras. Gestão Desenvolv. Reg. 2020, 16, 222–234. [Google Scholar]

- Souza, A.P.; Mota, L.L.; Zamadei, T.; Martim, C.C.; Almeida, F.T.; Paulino, J. Climate classification and climatic water balance in Mato Grosso state, Brazil. Nativa 2013, 1, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvares, C.A.; Stape, J.L.; Sentelhas, P.C.; De Moraes Gonçalves, J.L.; Sparovek, G. Köppen’s climate classification map for Brazil. Meteorol. Z. 2013, 22, 711–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcuzzo, F.N.; Rocha, M.; Melo, C.R.d. Rainfall mapping of Cerrado biome in the state of Mato Grosso. Bol. Goiano Geogr. 2012, 31, 83–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, N.G.; Biudes, M.S.; Querino, C.A.S. Seasonal and interannual pattern of meteorological variables in Cuiabá, Mato Grosso state, Brazil. Rev. Bras. Geofísica 2015, 33, 477–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, D.B.; De Sousa, R.R.; Nascimento, L.A.; Toledo, L.G.; Topanotti, D.Q. The spatial distribution of rainfall in the central western portion of the state of Mato Grosso, Brazil. Rev. Eletrônica Assoc. Geógrafos Bras. 2007, 1, 127–152. [Google Scholar]

- da Barbosa, A.J.S.S.; Blanco, C.J.C.; Melo, A.M.Q.; Souza, C.C.E.A.; Silva, H.P. Model of transferability for the rainfall erosivity factor. Sustain. Water Resour. Manag. 2023, 9, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehl, H.U.; Eltz, F.L.F.; Reichert, J.M.; Didoné, I.A. Rainfall pattern characterization in Santa Maria (RS), Brazil. Rev. Bras. Ciênc. Solo 2001, 25, 475–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, J.R.; Pinto, M.F.; de Souza, W.J.; Guerra, J.G.M.; de Carvalho, D.F. Water erosion in a Yellow-Red Ultisol under different patterns of simulated rain. Rev. Bras. Eng. Agríc. Ambient. 2010, 14, 140–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Carvalho, D.F.; Macedo, P.M.S.; Pinto, M.F.; de Almeida, W.S.; Schultz, N. Soil loss and runoff obtained with customized precipitation patterns simulated by InfiAsper. Int. Soil Water Conserv. Res. 2022, 10, 407–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Paca, V.H.M.; de Lima, A.M.M.; de Azambuja, A.M.S.; Fortes, J.; Domingos, N.; de Souza, J.E.F. Operating conditions and implementation of stations in the hydrometric network of the eastern Amazon—State of Pará. Repositório Inst. Geociênc. 2020, 11, 169–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, A.V.; da Silva, S.G.B.; de Martins, M.F.F.C.; Sanches, L. Analysis of estimation methods for the parameters of the Gumbel and GEV distributions in maximum precipitation events in the city of Cuiabá-MT. Rev. Eletrônica Eng. Civ. 2013, 6, 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabino, M.; de Souza, A.P.; de Almeida, F.T.; Zolin, C.A.; Lisboa, L. Disaggregation of Daily Rainfall in the State of Mato Grosso. Rev. Bras. Meteorol. 2022, 37, 427–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Back, Á.J.; Poleto, C. Analysis of temporal distribution patterns and characteristics of erosive rains in Florianópolis-Sc. Rev. Bras. Climatol. 2017, 21, 488–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- de Carvalho, D.F.; de Souza, W.J.; Pinto, M.F.; de Oliveira, J.R.; Guerra, J.G.M. Water and soil losses under different patterns of simulated rainfall and soil cover conditions. Eng. Agríc. 2012, 32, 708–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Carvalho, D.F.; Eliete, E.N.; de Almeida, W.S.; Santos, L.A.F.; Alves Sobrinho, T. Water erosion and soil water infiltration in different stages of corn development and tillage systems. Rev. Bras. Eng. Agríc. Ambient. 2015, 19, 1072–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moratelli, F.A.; Alves, M.A.B.; Borella, D.R.; Kraeski, A.; de Almeida, F.T.; de Souza, A.P. Effects of Land Use on Soil Physical-Hydric Attributes in Two Watersheds in the Southern Amazon, Brazil. Soil Syst. 2023, 7, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunkerley, D. Effects of rainfall intensity fluctuations on infiltration and runoff: Rainfall simulation on dryland soils, Fowlers Gap, Australia. Hydrol. Process. 2011, 26, 2211–2224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Steiner, J.; Zheng, F.; Gowda, P. Impact of rainfall pattern on interrill erosion process. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 2017, 42, 1833–1846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alavinia, M.; Saleh, F.N.; Asadi, H. Effects of rainfall patterns on runoff and rainfall-induced erosion. Int. J. Sediment Res. 2019, 34, 270–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, D.K.; Souza, E.P.D.; Costa, A.A. Moist convection in Amazonia: Implications for numerical modelling. Rev. Bras. Meteorol. 2009, 24, 168–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fietz, C.R.; Comunello, É.; Cremon, C.; Dallacort, R. Estimate of Probable Precipitation for the State of Mato Grosso, 3rd ed.; Embrapa Agropecuária Oeste: Dourados, Brazil, 2008; 31p. [Google Scholar]

- Pes, L.Z.; Giacomini, D.A. Soil Conservation; Colégio Politécnico, Rede e-Tec Brasil; Universidade Federal de Santa Maria: Santa Maria, Brazil, 2017; 69p. [Google Scholar]

- da Luz, C.C.S.; de Souza, A.P.; de Almeida, F.T.; Martim, C.C.; da Silva, W.C.; Pereira, R.R.; de Carvalho, D.F. Water erosion in soybean farming areas under different soil covers and simulated rainfall patterns in the Southern Amazon, Brazil. Catena 2025, 254, 108959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, W.S.; Panachuki, E.; Oliveira, P.T.S.; Silva, M.R.; Alves Sobrinho, T.; de Carvalho, D.F. Effect of soil tillage and vegetal cover on soil water infiltration. Soil Tillage Res. 2018, 175, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, V.S.; Ceddia, M.B.; Antunes, M.A.H.; de Carvalho, D.F.; Anache, J.A.A.; Rodrigues, D.B.B.; Oliveira, P.T.S. USLE K-Factor Method Selection for a Tropical Catchment. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, L.; Lehmann, P.; Zheng, C.; Or, D. Rainfall Intensity Temporal Patterns Affect Shallow Landslide Triggering and Hazard Evolution. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2020, 47, e2019GL085994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, M.A.B.; de Souza, A.P.; de Almeida, F.T.; Hoshide, A.K.; Araújo, H.B.; da Silva, A.F.; de Carvalho, D.F. Effects of Land Use and Cropping on Soil Erosion in Agricultural Frontier Areas in the Cerrado-Amazon Ecotone, Brazil, Using a Rainfall Simulator Experiment. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Luz, C.C.S.; de Almeida, W.S.; de Souza, A.P.; Schultz, N.; Anache, J.A.A.; de Carvalho, D.F. Simulated rainfall in Brazil: An alternative for assessment of soil surface processes and an opportunity for technological development. Int. Soil Water Conserv. Res. 2024, 12, 29–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, J.A.X.; de Almeida, F.T.; de Souza, A.P.; Paulista, R.S.D.; Zolin, C.A.; Hoshide, A.K. Determination of Soil Erodibility by Different Methodologies in the Renato and Caiabi River Sub-Basins in Brazil. Land 2024, 13, 1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eltz, F.L.F.; Mehl, H.U.; Reichert, J.M. Interrill soil and water losses in an ultisol under four rainfall patterns. Rev. Bras. Ciênc. Solo 2001, 25, 485–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Carvalho, D.F.; Cruz, E.S.; Pinto, M.F.; Silva, L.D.B.; Guerra, J.G.M. Rainfall characteristics and erosion losses for different soil management practices. Rev. Bras. Eng. Agríc. Ambient. 2009, 13, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazzano, M.G.P.; Eltz, F.L.F.; Cassol, E.A. Erosivity, rainfall coefficient and patterns and return period in Quarai, RS, Brazil. Rev. Bras. Ciênc. Solo 2007, 31, 1205–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Pang, L.; E Xie, B. Typhoon disaster in China: Prediction, prevention, and mitigation. Nat. Hazards 2009, 49, 421–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- do Brandão, V.S.; da Silva, D.D.; Ruiz, H.A.; Pruski, F.F.; Schaefer, C.E.G.R.; Martinez, M.A.; Silva, E.O. Soil losses and physical and micromorphological characterization of formed crusts in soils under simulated rainfall. Eng. Agríc. 2007, 27, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.P.; Hong, N.M.; Wu, P.J.; Wu, C.F.; Verbung, P.H. Impacts of land use change scenarios on hydrology and land use patterns in the Wu-Tu watershed in Northern Taiwan. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2007, 80, 111–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pielke, R.A.; Avissar, R. Influence of landscape structure on local and regional climate. Landsc. Ecol. 1990, 4, 133–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bununu, Y.A.; Bello, A.; Ahmed, A. Land cover, land use, climate change and food security. Sustain. Earth Rev. 2023, 6, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huong, H.T.L.; Pathirana, A. Urbanization and climate change impacts on future urban flooding in Can Tho city, Vietnam. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2013, 17, 379–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randhir, T.O.; Tsvetkova, O. Spatiotemporal dynamics of landscape pattern and hydrologic process in watershed systems. J. Hydrol. 2011, 404, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dantas, L.G.; Ferreira, A.J.F.; Pinto Junior, J.A.; Cortes, T.R.; Neves, D.J.D.; de Oliveira, B.F.A.; Silveira, I.H. Projections of extreme weather events according to climate change scenarios and populations at-risk in Brazil. Clim. Change 2025, 178, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavers, D.A.; Villarini, G.; Cloke, H.L.; Simmons, A.; Roberts, N.; Lombardi, A.; Burgess, S.N.; Pappenberger, F. How bad is the rain? Applying the extreme rain multiplier globally and for climate monitoring activities. Meteorol. Appl. 2025, 32, e70031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyer, C.; Chaumont, D.; Chartier, I.; Roy, A.G. Impact of climate change on the hydrology of St. Lawrence tributaries. J. Hydrol. 2010, 384, 65–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiprotich, P.; Wei, X.; Zhang, Z.; Ngigi, T.; Qiu, F.; Wang, L. Assessing the impact of land use and climate change on surface runoff response using gridded observations and Swat+. Hidrology 2021, 8, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steele-Dunne, S.; Lynch, P.; McGrath, R.; Semmler, T.; Wang, S.; Hanafin, J.; Nolan, P. The Impacts of Climate Change on Hydrology in Ireland. J. Hydrol. 2008, 356, 28–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Τοta, J.; Fisch, G.; Fuentes, J.; De Oliveira, P.J.; Garstang, M.; Heitz, R.; Sigler, J. The analysis of the daily rainfall in a pasture site during the Wet Season of 1999—TRMM/LBA project. Acta Amaz. 2000, 30, 629–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, P.A.D.S.; Querino, C.A.S.; Moura, M.A.L.; Querino, J.K.A.D.S.; Moura, A.R.D.M. Spatial-temporal variability of the climate variable at the southern mesoregion of Amazonas. Rev. Ibero Am. Ciênc. Ambient. 2019, 10, 169–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos Neto, L.A.; Maniesi, V.; Silva, M.J.G.; Querino, C.A.S.; Lucas, E.W.M.; Braga, A.P.; Ataíde, K.R.P. Hourly precipitation distribution in Porto Velho-RO-1998-2013. Rev. Bras. Climatol. 2014, 14, 213–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Pedreira Junior, A.L.; Querino, C.A.S.; Querino, J.K.A.D.S.; Santos, L.O.F.; Moura, A.R.D.M.; Machado, N.G.; Biudes, M.S. Hourly variability and seasonal intensity of the rainfall in the municipality of Humaitá-AM. Rev. Bras. Climatol. 2018, 22, 463–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Carvalho, L.M.V.; Silva, A.E.; Jones, C.; Liebmann, B.; Silva Dias, P.L.; Rocha, H.R. Moisture transport and intraseasonal variability in the South America monsoon system. Clim. Dyn. 2011, 36, 1865–1880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).