Abstract

Antisolvent crystallization is a promising method for recovering rare earth elements (REEs). While it offers high theoretical yields of Y2(SO4)3·nH2O from aqueous leach solutions, the recovery is constrained by kinetic limitations. This study examined the crystallization of Y2(SO4)3·nH2O in a fluidized bed reactor (FBR) using ethanol, focusing on the effects of the organic-to-aqueous (O/A) ratio and flow rates on yield and crystal properties. O/A ratios of 0.9 and 1.1 were investigated with an initial Y3+ concentration of 0.87 g/L and a crystallization time of 3 h. The system exhibits multiple rate-limiting steps. At low O/A ratios (0.9), extended induction times indicate either nucleation rate-limitations despite high supersaturation or the possible formation of an initial metastable phase, requiring extended crystallization time for near-equilibrium yields. At high O/A (1.1), elevated supersaturation accelerates nucleation and achieves ~82% yield in 3 h; however, crystal growth exhibited a remaining rate limitation. Lower supersaturation and slower mixing at O/A = 0.9 favored growth, producing crystals with D50 > 34 µm. This work explores how operational parameters influence crystallization behavior while achieving practical yields and acceptable crystal characteristics within a reasonable timeframe. The FBR provided controlled operation, enabling consistent product formation and process flexibility.

1. Introduction

Rare earth elements (REEs) are crucial for advanced technologies, with an increase in their demand [1]. The REE series includes the lanthanides, from lanthanum (La) to Lutetium (Lu), along with scandium (Sc) and yttrium (Y). The REEs are grouped due to their similar ionic radii and generally being in the trivalent state [2]. Their excellent physicochemical properties, combined with subtle differences among them, contribute to their wide range of uses, including in alloys, magnets, batteries, catalysts, fuel cells, lighting, capacitors, and optics [3].

As the demand for these applications grows, the strain on the REE supply chain intensifies. Securing a stable supply is challenging due to the dispersed and complex nature of REE deposits, which complicates both their extraction and separation from other minerals, as well as their fractionation into individual REEs [4]. In response, increasing attention is being given to both primary and secondary sources, such as end-of-life products, for REE recovery [5]. Various processing techniques have been developed, including dry processing, pyrometallurgy, and hydrometallurgy [6]. The hydrometallurgical methods span an extensive range, including precipitation/crystallization, ion exchange, solvent extraction, adsorption, etc. They are largely interchangeable, offering various options within each method to recover REE solids in the desired form [7]. However, these methods often use hazardous or costly reagents/materials, along with either time-consuming or energy-intensive procedures [6].

Among the various techniques, antisolvent crystallization (AS) has emerged as a promising alternative for the recovery of REEs from aqueous leach solutions due to advantages such as recycling the antisolvent and operating at ambient temperatures over the conventional methods mentioned above [8]. Antisolvent crystallization can replace some of the classical methods along the extensive recovery path needed to reach the final individual metal product. It is particularly relevant at two critical stages: immediately after leaching from solid sources and during the solid recovery of the final product. The first relevant area of introduction is just after the initial leaching stage from the solid source. For the case of REEs, using alcohols such as ethanol has been shown to be beneficial at this point, as selective recovery of the full REE fraction from other elements such as Al, Co, Ni, and Mn has been achieved [8]. However, further REE fractionation is required by using separation methods such as ion exchange and solvent extraction. After stripping or elution, the metal remains in solution; therefore, antisolvent crystallization can once again be used instead of precipitation or electro-refining for the final solid recovery [9]. Despite its potential, research into AS crystallization for REE recovery is still limited [9,10,11,12,13].

Antisolvent crystallization recovers the target solute from the original solution by the addition of another substance, the antisolvent, which reduces the solubility of the intended solute. The interaction between the solvent and antisolvent shifts the equilibrium by lowering the solubility, such as by reducing the dielectric constant of the solution. Under these conditions, the system can reach a supersaturated state if the equilibrium concentration in the mixture is exceeded, which prompts crystallization of the target compound [14]. Although the initiation of crystallization and a large part of the overall system kinetics is governed by nucleation, the rate-determining step can include any of the other steps within the crystallization process, such as the initial mixing to the final growth steps.

AS crystallization is generally known for its fast kinetics with immediate crystallization. However, it also presents several challenges that need to be addressed [15,16]. One of the primary disadvantages is the difficulty in controlling crystallization, leading to issues such as fines, broad crystal size distributions (CSDs), and undesired morphologies [11,17]. The substantial reliance on precise control of the hydrodynamic conditions is another critical factor, particularly in ternary systems where the chemical components have varying physical and chemical properties. Additionally, the significant reduction in solubility can create large local supersaturation hotspots, especially when mixing is inadequate. This can lead to excessive nucleation, resulting in the formation of fine particles [18].

However, recent experimental studies using stirred-tank reactors for antisolvent crystallization with ethanol as the antisolvent have shown that yttrium sulfate (Y2(SO4)3·nH2O) exhibits unexpectedly low yields (~13%) at a concentration of ~0.4 g/L, despite thermodynamic predictions indicating high recovery potential (~85%) at an O/A ratio of 0.9 [8,19]. This discrepancy in the recovery efficiency of Y2(SO4)3·nH2O using antisolvent crystallization remains unexplored, highlighting a need for further investigation into its crystallization behavior and the process conditions required to achieve higher yields. In addition, yttrium is often present in low concentrations in process streams, making its recovery more challenging [20,21]. To overcome these limitations, more efficient crystallization techniques are needed to enhance yield and product quality. One potential approach is to effectively control the crystallization process either by directly regulating supersaturation or by optimizing the distribution of supersaturation through improved mixing [10,22].

Fluidized bed reactors (FBRs) offer a promising solution to address these challenges by enhancing supersaturation control, providing long residence times for slow-crystallizing systems, and mitigating issues such as fines losses and attrition [23,24]. FBRs are widely used for crystallization at an industrial scale and provide advantages such as improved mass transfer, controlled particle growth, minimized abrasion and attrition, and effective solid–liquid separation through settling at a critical size [25,26]. Traditionally, FBRs are operated using heterogeneous seeds such as silica or quartz as a growth surface [27]. However, this approach introduces additional washing and recrystallization steps. An alternative strategy involves generating homogeneous seeds in situ of the target compound, which could simplify processing while maintaining efficiency [28].

This study aimed to investigate antisolvent crystallization of Y2(SO4)3·nH2O in an FBR and identify operational parameters that influence recovery. Preliminary work examined the effects of seeding, crystallization time, and hydrodynamic factors such as recirculation and inlet flow rates on yield and crystal characteristics. The main objective was to understand how antisolvent crystallization behaves in an FBR under different flow and compositional conditions, with particular attention to the influence of O/A ratio and mixing on crystallization kinetics and morphology. The focus of this work was to explore and become familiar with the behavior of the system, a process that has not been previously studied. At this stage, the aim was not optimization or full mechanistic control, but rather to observe how the system responds under different operating conditions and identify key factors influencing crystallization. Bench-scale experiments are standard for such early-stage investigations because they allow for practical and cost-effective trials while providing insights that guide more controlled future studies and eventual scale-up.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Thermodynamic Modeling

OLI Studio: Stream Analyzer™ V.11.5.1.7 was used to model the chemistry and predict the solid phase composition along with the possible recoveries by implementing the Mixed-Solvent Electrolyte (MSE) framework with the recent addition of the Y2(SO4)3-H2O-ethanol system, as discussed in Sussens et al. [19]. In addition, the scaling tendency (ST) was also simulated as a measure of the supersaturation calculated using the ionic activity product (IAP) and the solubility product constant (KSP) as shown in Equation (1),

2.2. Chemicals

All the chemicals were used as received without any further purification. The yttrium sulfate octahydrate ([Y2(SO4)3·8H2O] with 99.9% purity, CAS: 7446–33-5) was purchased from Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA, and absolute ethanol (99.9% purity, CAS: 64–17-5) was purchased from Kimix Chemicals, Cape Town, South Africa. Deionized water from a Millipore Elix (>15 MΩ·cm) was used to prepare all relevant solutions.

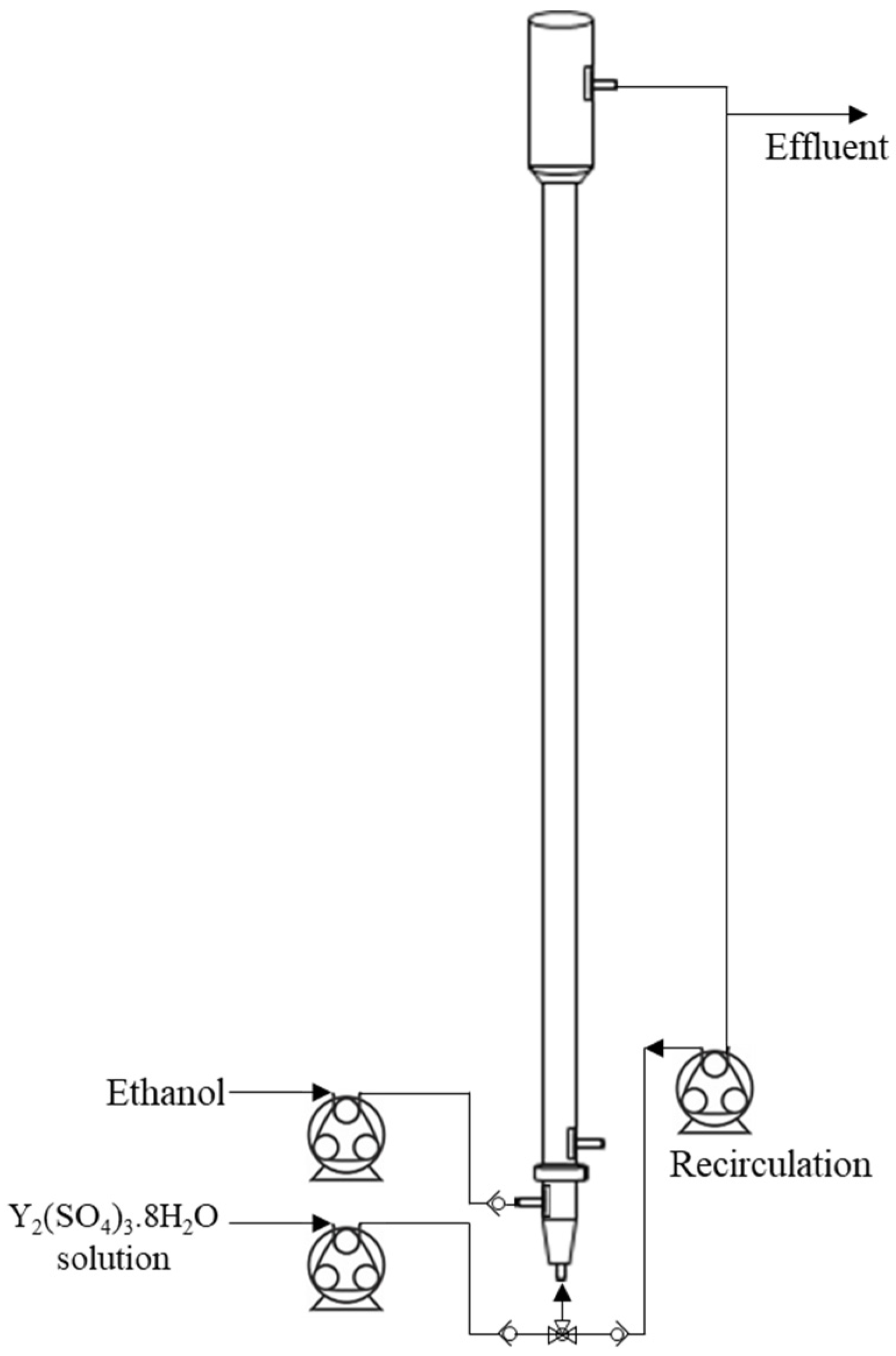

2.3. Reactor Set-Up

All experiments were conducted using an FBR fabricated from glass. The reactor had a bottom section with an internal diameter (ID) of 2 cm and a height of 75 cm. The top section was tapered with a diameter expanding to 4 cm over a height of 10 cm. This design feature allowed for a release in hydraulic loading, which helped retain a greater proportion of fines in the active region of the FBR, preventing them from being elutriated with the effluent. The total working volume of the reactor was 235 mL.

The main fluidization port at the bottom and the top recirculation port each had an ID of 0.7 cm, while the two side ports had an ID of 0.5 cm. The bottom side port served as the inlet for ethanol, while the other side port was used for sampling. The bottom conical section was packed with spherical glass beads of 0.4 cm and 0.1 cm in diameter to ensure uniform liquid flow distribution.

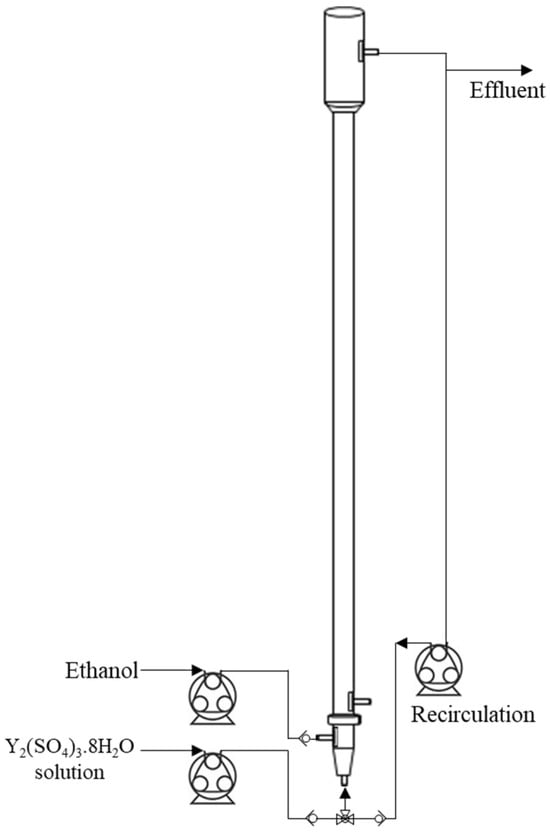

The fluidization port was used alternately: either for introducing the aqueous yttrium sulfate solution during filling or for recirculating the effluent stream. Peristaltic pumps were employed for both inlet feeding and recirculation, and non-return valves were installed to prevent liquid backflow. Figure 1 illustrates the FBR setup.

Figure 1.

Illustration of the fluidized bed reactor set-up used for the batch experiments.

2.4. Experimental Design

The starting concentration of Y3+ was set at 0.87 g/L, approximately twice the concentration observed in NiMH battery leach solutions, which is ~0.4 g/L according to the literature [8]. This higher concentration was chosen to carry out the analysis more easily. The organic-to-aqueous (O/A) ratio was selected based on the thermodynamic analysis detailed in Section 3.1.

Initial trials were conducted to evaluate the impact of reagent-grade homogeneous seeds of Y2(SO4)3·8H2O. The main investigations focused on the hydrodynamic aspects, including total equivalent flow rates (total inlet flow rate = recirculation rate), total inlet flow rate, recirculation rate, and the O/A ratio, as summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Design of experimental sets and variables.

The trial experiments were run for 30 mins to observe the initial crystallization. Due to the cost of Y2(SO4)3·8H2O, the FBR could not be packed with seeds to the usual extent of ~20% of the total FBR height [24]. Instead, seeding was based on a critical seed loading of 5% of the expected total yield [29]. The reagent seeds were sieved to a size range of 125–150 µm, with a CSD of D50 = 135 µm, as recommended by Chianese & Kramer [30].

The main sets of experiments were initially conducted for up to 5 h to observe extended crystallization behavior. Based on these results, subsequent runs were standardized to 3 h, as this duration was sufficient to capture the key kinetic trends and crystal characteristics.

Lastly, experiments at [Y3+] = 0.4 g/L, as observed in NiMH battery leach solutions, were also conducted as a comparison [8]. Additionally, the O/A ratio of 0.56 was also investigated as recommended by Korkmaz et al. [8] to allow for impurity rejection while still recovering a high amount of the other REE from the NiMH solution.

2.5. Experimental Procedure

All experiments were conducted at ambient laboratory temperature (23 °C) and done in triplicate with error bars in figures indicating standard error. The start-up process involved simultaneously starting the feeds of the aqueous yttrium sulfate solution and ethanol at their respective rates to achieve the intended O/A ratio as outlined in Table 2, followed by suspending the inlet flows once the FBR and recirculating sections were filled to initiate recirculation. For the initial investigations, the seeds were loaded onto the glass beads before initiation of the experiments.

Table 2.

Inlet flow ratios.

Given that mixing is critical in antisolvent crystallization, the focus of the main experiments was to understand how varying the different flow rates affects yield and crystal characteristics [31]. The associated Reynolds numbers at the entrance of each port are outlined in Table S1. In addition, the experiments were designed to maintain a long residence time for the crystals and liquids in the active zone of the FBR while avoiding excessive recirculation of the crystals, which can cause loosely aggregated fines to break apart. Table S2 shows the theoretical predictions regarding which crystal sizes will be elutriated and recirculated, along with the accompanying fluidization calculations used.

Each experiment was run for 3 h under the operational conditions specified in Table 1. Sampling of 2 mL aliquots was performed intermittently. The samples were filtered using a removable 0.2 μm nylon filter membrane to recover the solids (for SEM analysis), and 1 mL of the supernatant was immediately quenched to stop any further crystallization. At the end of each experimental run, the FBR was drained, and the suspension was filtered. The filtered supernatant samples were diluted to a maximum alcohol concentration of 1% for ICP-OES analysis to determine the Y3+ concentration remaining in the solution. This concentration was used to calculate the yields according to Equation (2). Solid samples were dried in a desiccator for at least 24 h before undergoing SEM, laser diffraction, and XRD analysis. Effluent samples from the O/A experiments were left undisturbed in vials for 2 months before final yield analysis using the same sample preparation techniques.

where is the initial concentration of Y3+ in solution and is the final concentration of Y3+ after crystallization in solution, expressed as g/L.

2.6. Analytical Methods

The concentration of Y3+ in solution was determined from filtered liquid samples using Inductively Coupled Plasma Optical Emission Spectroscopy (ICP-OES) (Agilent 5800 ICP-OES, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Determination of the solid phases of the yttrium salt was done by X-ray Diffraction (XRD) (Bruker D8 Advance, Billerica, MA, USA) with cobalt-source radiation, equipped with a position-sensitive detector (Bruker LYNXEYE, Billerica, MA, USA) in Bragg–Brentano geometry. The power settings were 40 mA and 35 kV. The crystal size distribution (CSD) was determined by laser diffraction measurements (Malvern Mastersizer 3000, Malvern, Worcestershire, UK). The crystal morphology and further size determination were performed using Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) (Tescan MIRA3 RISE, Brno, Czech Republic) with an annular backscattered electron detector scintillator made of yttrium aluminum garnet.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Thermodynamic Predictions and Their Role in Experimental Desing

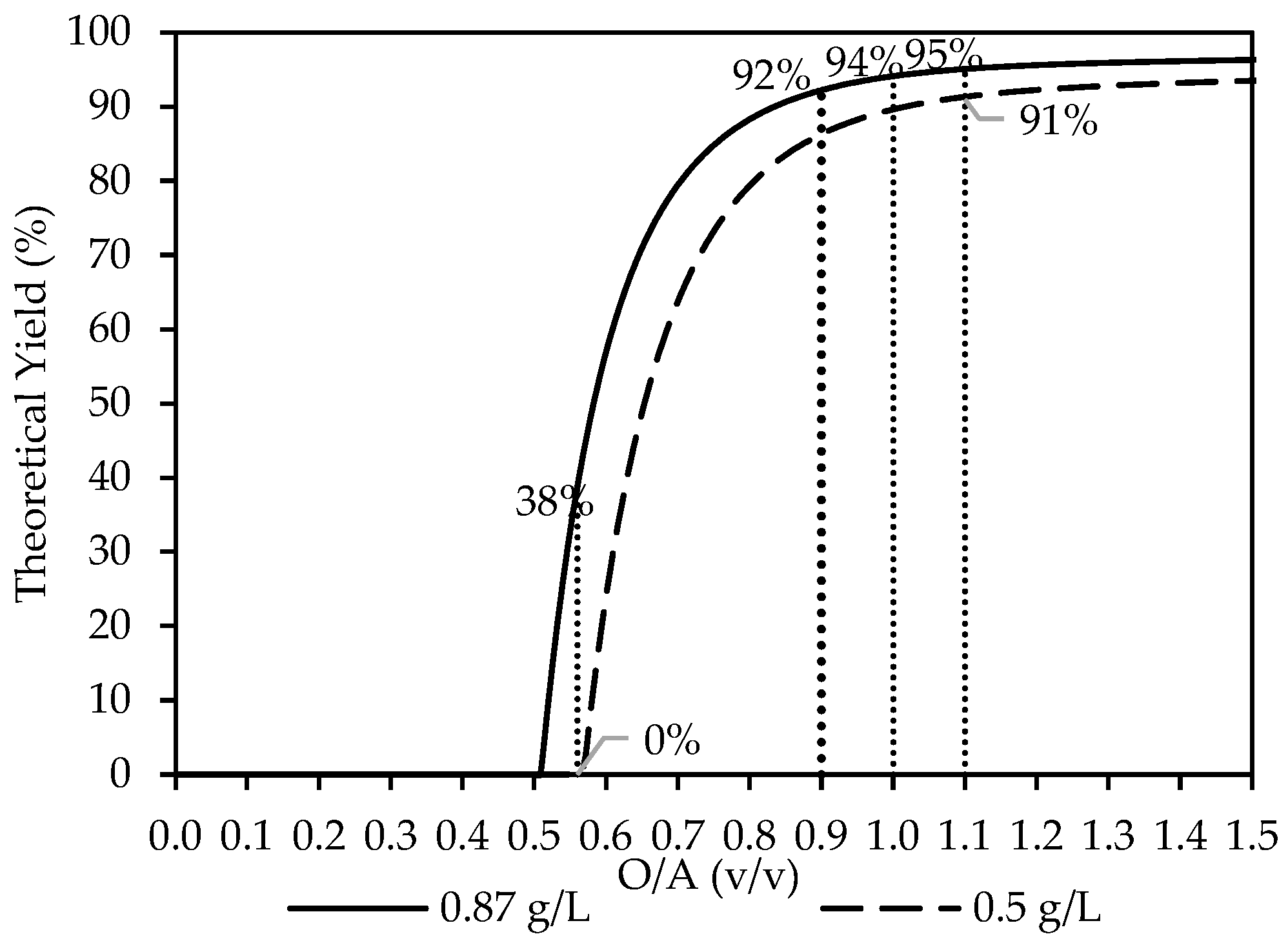

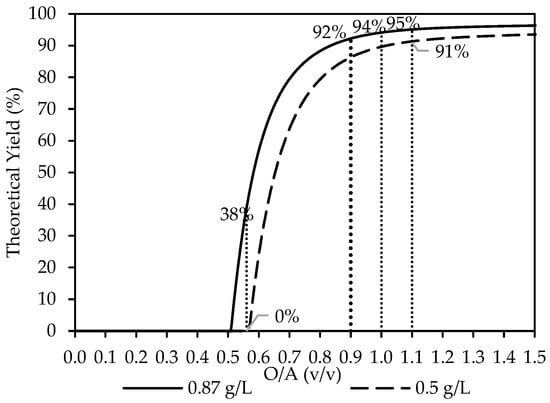

The thermodynamic simulations were carried out using OLI Studio with the updated MSE databank to evaluate the recovery of Y2(SO4)3·8H2O using ethanol, as shown in Figure 2. Most simulations were conducted at a feed concentration of 0.87 g/L Y3+. The yield rapidly increased as ethanol increased, with the onset of crystallization predicted to take place from O/A = 0.5 to a maximum plateau at around O/A = 1.1 onwards, where a yield of 95% was reached. An O/A ratio of 0.9 was selected as the focus for the experimental studies discussed in the following section. However, as discussed further below, other O/A ratios (1.0 and 1.1) were also of relevance.

Figure 2.

The theoretical yield of Y3+ as the O/A ratio increases from a starting concentration of 0.87 g/L Y3+ (―) and 0.5 g/L Y3+ (---). The dotted lines, serving as visual guides, indicate the O/A ratios investigated in this study, with Y2(SO4)3·8H2O predicted as the stable solid phase.

Additional simulations were also carried out at the same concentration as those reported by Korkmaz et al. [8] at [Y3+] = 0.5 g/L and O/A = 0.56, along with O/A = 1.1, which is relevant later on in this study. The calculated theoretical yields were 0% and 91%, respectively, as indicated in Figure 2. Whereas, at the higher concentration [Y3+] = 0.87 g/L, used for this study, with an O/A = 0.56, only 38% is predicted. Based on the thermodynamic analysis, the extent of yttrium crystallization observed by Korkmaz et al. [8] occurred near the lower limit of what is theoretically recoverable at the examined O/A ratios.

3.2. Exploring Seeding Effects During Reactor Start-Up

Operating the FBR required start-up conditions to be established first. A trial was conducted to assess whether seeding significantly affected the yields compared to no seeding. The trial was carried out for 30 min and a hydraulic residence time of 3 min while continuously operating the FBR. Visual observation of the system showed an initial increase in turbidity, which became clear after a few minutes. The brief turbidity change is a common effect when mixing water with ethanol; therefore, the increased turbidity at that point was not related to nucleation. Figure S1 highlights that, although a 92% theoretical yield was predicted, minimal crystallization took place for both the unseeded and seeded experiments within the specified duration. A degree of dissolution of the seeds was also observed, as evidenced by the concentration in the solution increasing slightly, resulting in negative yields.

The aqueous and ethanol streams were fed at slow rates to extend the residence time and limit elutriation. Both streams were in the laminar region, as indicated by the low Reynolds numbers. Combined with the slow kinetics, this increased the initial contact time between the seeds and the aqueous phase. This made partial dissolution of the Y2(SO4)3·8H2O seeds possible [32]. Although seeding was intended to accelerate crystallization, the 5% loading did not lead to noticeable improvement in yield or crystallization time under the tested conditions.

Given that seeding had no measurable influence on early-stage yield under the tested conditions, and that literature demonstrates effective FBR operation without externally added seeds by relying on in situ seed generation, further experiments were conducted without added seeds [28]. This aligns with reports showing that large induction times can still occur in the metastable zone, even in the presence of seeds [33].

Overall, these results also indicate that even longer residence times are needed in the FBR for crystallization to occur. Such residence times can be achieved either by further reducing flow rates or by introducing recirculation.

3.3. Effect of Process Parameters on the Crystallization

This section examines how variations in the process parameters, which include equivalent inlet and recirculation rates, total inlet flow rate, recirculation rate, and the effective O/A ratio, impact the yield and crystal characteristics. All the experiments in Sets A, B, and C in Table 1 were designed to take place at O/A ratio = 0.9.

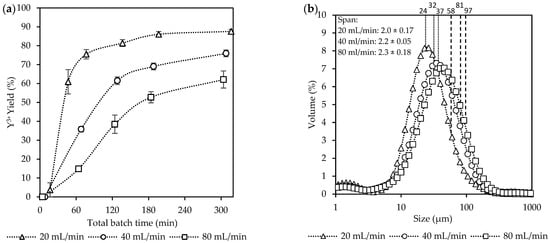

3.3.1. The Influence of Equivalent Flow Rates on Yield and Crystal Characteristics

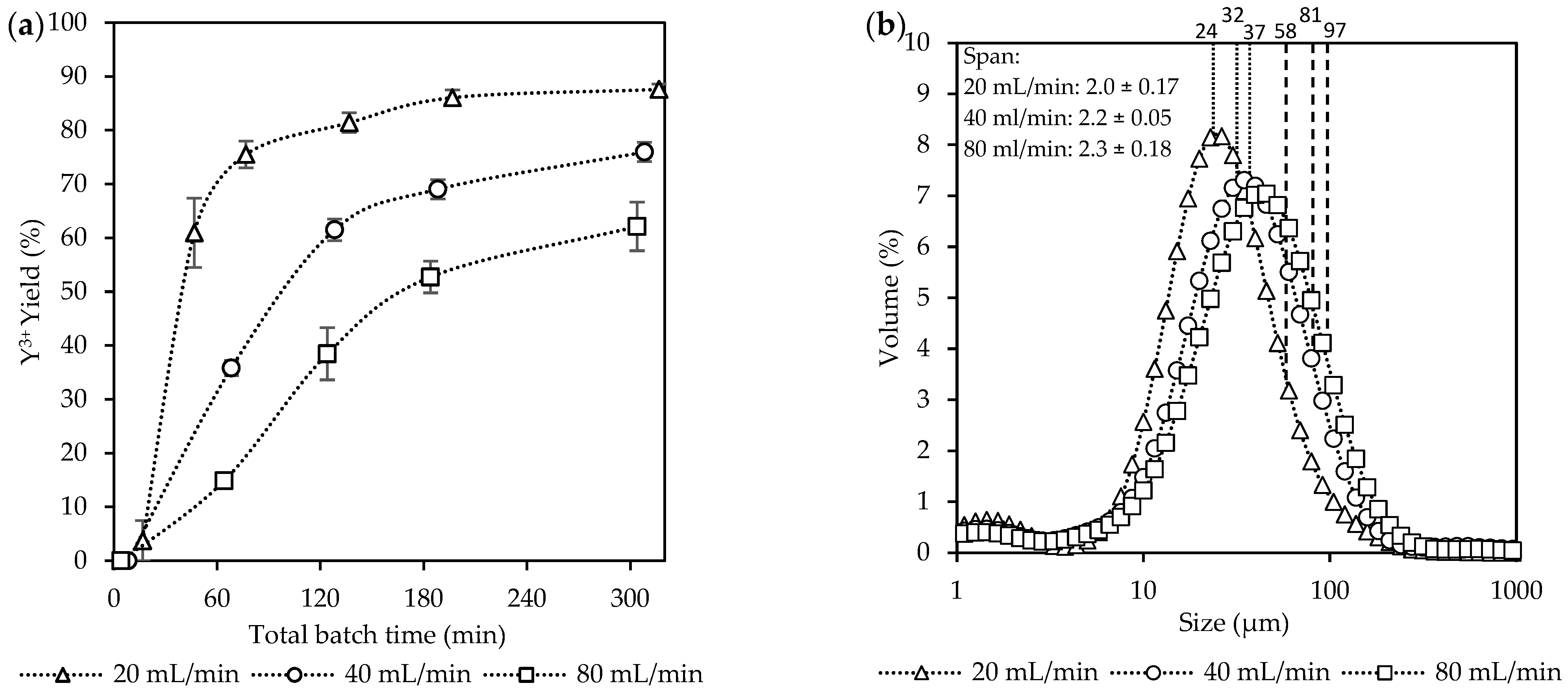

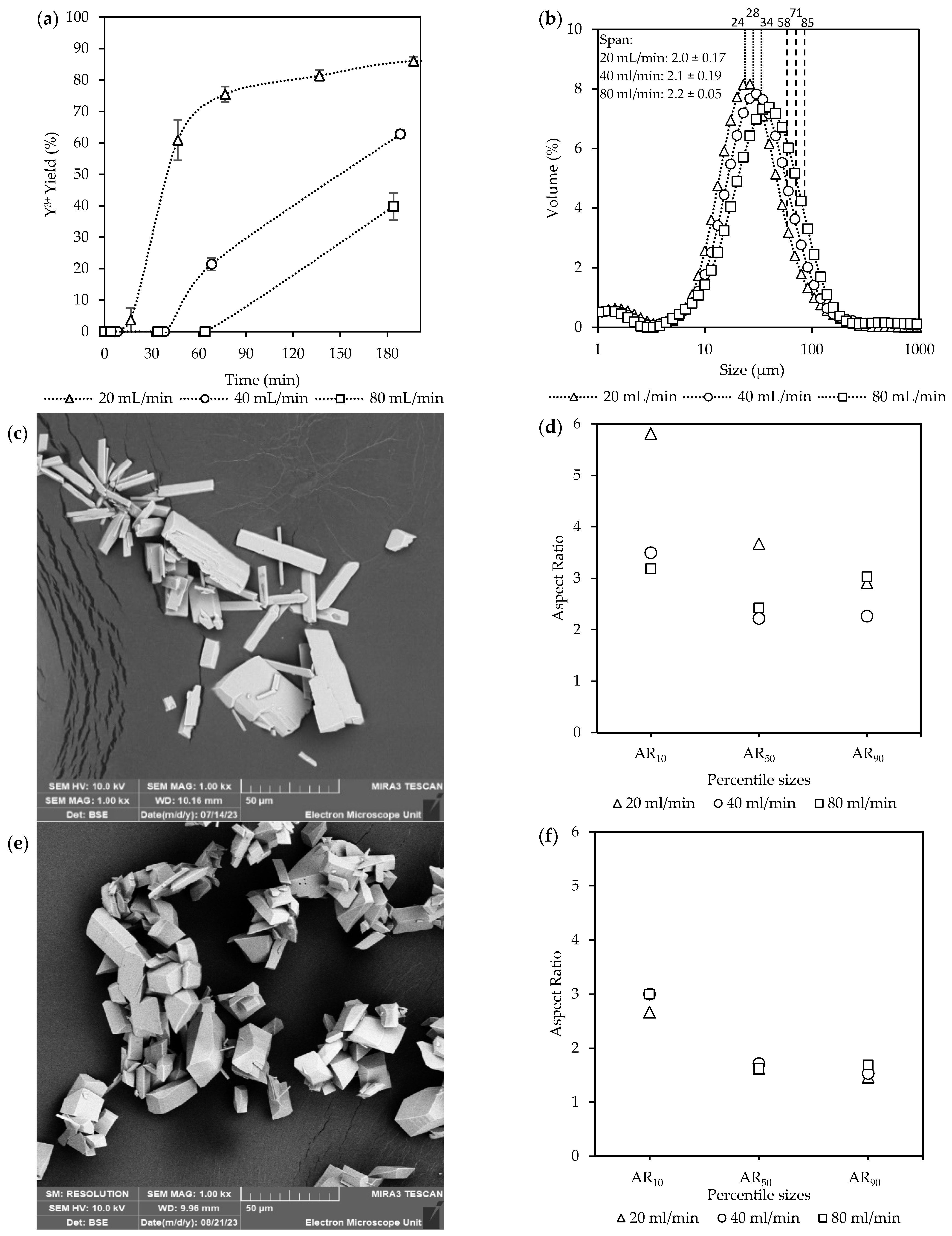

Figure 3 illustrates the effects of equivalent flow rates (total inlet flow rate = recirculation rate) on the yield of Y3+ over time, along with the accompanied CSDs and crystal characteristics for experimental set A. The impact of mixing, as controlled by the flow rates, was investigated by ensuring that the total inlet flow rate and recirculation rate were equivalent for each set, maintaining consistent flow and mixing dynamics throughout. The inlet flow rates were selectively kept low to prolong the residence times spent in the FBR for both the liquid and solids before entering the recirculation zone. The corresponding Reynolds numbers were, however, all within the laminar region.

Figure 3.

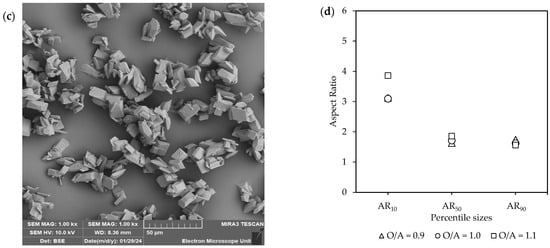

The effect of the equivalent flow rates [Exp. A] on the (a) yield; (b) CSD curves, with vertically dotted and striped lines indicating the D50 and D90 sizes, respectively; (c) a representative SEM image of the final product (see Figure S2); and (d) aspect ratios of the final product.

The yields in Figure 3a increased progressively over time for all the flow rates. The highest yield was achieved at 20 mL/min (88%), followed by 40 mL/min (76%), and lastly 80 mL/min (62%). Crystallization was mostly completed within the first 60 min after filling the FBR at a flow rate of 20 mL/min. At this point, approximately 80% of the potential theoretical yield was achieved, while at higher flow rates, the yields were significantly lower, reaching only 38% and 16% for 40 mL/min and 80 mL/min, respectively. After this period, the yield at 20 mL/min had reached a plateau after 180 min. For the other two flow rates, a steady increase was observed with no plateau region reached within the 5 h experiment duration. Although high yields were achieved quickly at 20 mL/min, the consumption of supersaturation was slow within the initial phases of crystallization, resulting in only 4% yield at 16 min.

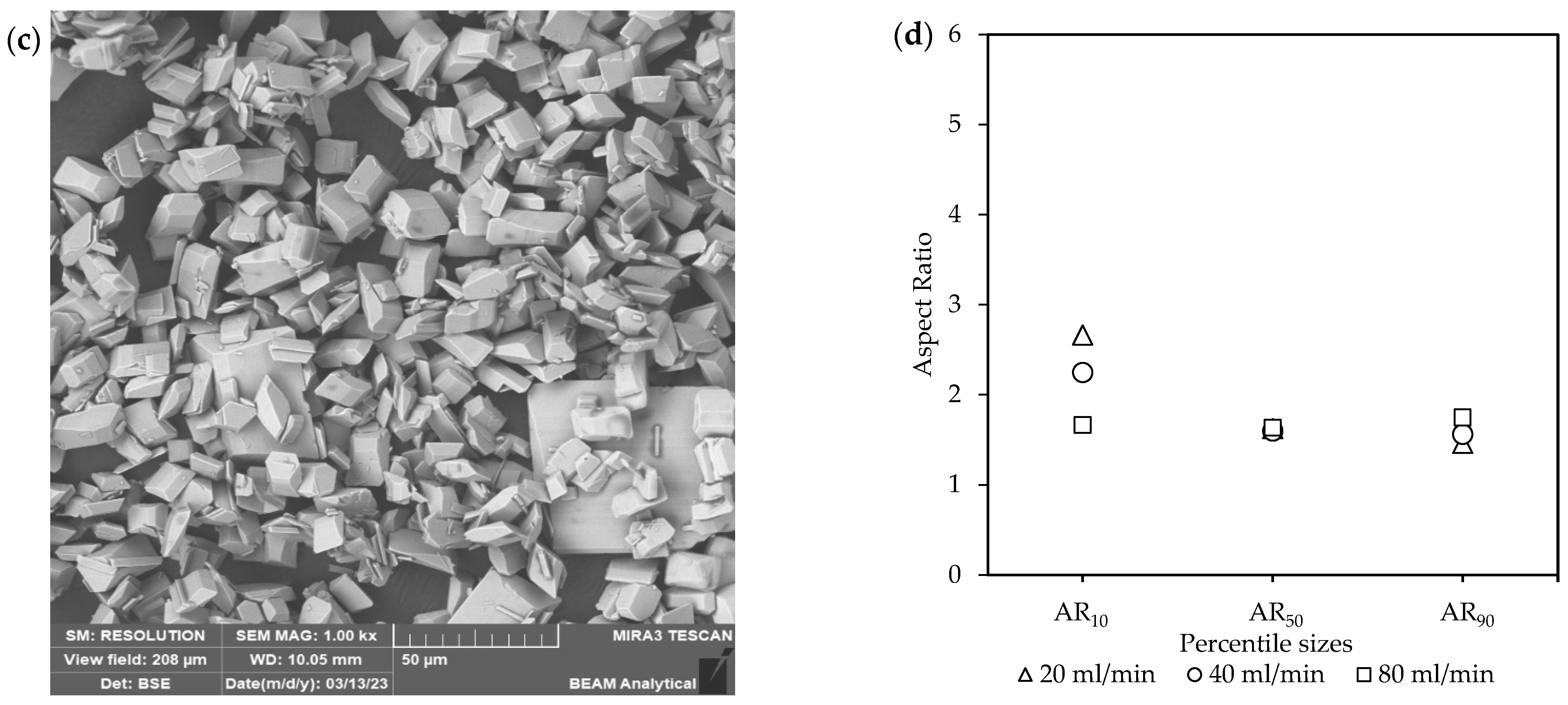

Figure 3b shows the CSD measurements, where a shift towards larger sizes was observed with an increase in the total flow rates from 20 mL/min to 80 mL/min. The shift towards larger crystals was seen for both the D50 and D90 values from 24 µm to 37 µm and 58 µm to 97 µm, respectively. However, no significant differences were observed for the span across the three flow rates, which was ~2.

These observations were further supported by visual evaluation of the crystals and their aspect ratios (ARs) seen in Figure 3c,d. The SEM images in Figure 3c and Figure S2 show the final crystal products, which were visually very similar. Although these crystals were well-defined in their 3D structure, a variety of morphologies existed, from prismatic rods to more equant polyhedra. Additionally, in some instances, fine particles, as seen in Figure S2, were also observed for all conditions. The existence of fines, even with gentle mixing in the FBR, can be caused by recirculation of crystals through the narrow passages of the non-return valve and around distribution beads. However, filtration of the total final suspension was generally done within a few minutes, indicating no major filtration issues.

The ARs of the smaller crystals with the percentile values (AR%) at AR10 decreased with an increase in the flow rates, with 20 mL/min (AR10 = 2.7), 40 mL/min (AR10 = 2.3), and 80 mL/min (AR10 = 1.7). However, a reduction in the ARs were observed for both 20 mL/min and 40 mL/min for the larger crystals at AR50 and AR90. This resulted in no major difference between the ARs at these points for the different flow rates. Generally, large ARs are a poor product characteristic due to causing filtration issues [14]. However, the crystals with large ARs are only a minority observation within the final product.

These findings suggest that higher flow rates lead to lower crystallization yields and larger crystal sizes. Several interrelated factors occurring during crystallization can explain these observations. Firstly, at lower flow rates, the low Reynolds numbers indicate that the system is firmly in the laminar region, where poor mixing at the inlet ports allows more persistent local supersaturation hotspots to form, promoting nucleation [18]. Although greater mixing could have reduced these hotspots, it could not be increased without shortening the required residence time. Secondly, a slight increase in the O/A ratio was observed at lower flow rates, as shown in Table S3, which can contribute to enhanced nucleation [33]. This effect was noticeable at inlet flow rates of 20–40 mL/min due to increased static pressure while filling the FBR. The pressure buildup led to a gradual increase in the O/A ratio for these experiments, due to the reduction in the aqueous flow rate. Despite these fluctuations, further experimental analysis accounts for the varying conditions, ensuring a valid comparison across the data sets as seen in the adjusted variable Table S4. Additionally, if the induction time is kinetically limited by mass transfer, then faster mixing of the two fluids can result in dilution, which causes the system to no longer exceed the activation barrier required for nucleation to take place [34].

These phenomena are all related to the system supersaturation, taking place on different scales. Therefore, an increase in the supersaturation due to any of the above-mentioned factors results in more nuclei being formed. The higher supersaturation both promotes the formation of smaller crystals and enables higher yields within a given time. The smaller crystals, in turn, accelerate the consumption of supersaturation because of their increased surface area. Additionally, smaller crystals formed at higher supersaturation often exhibit higher ARs, as their growth is directed along a preferred 2D plane [35]. Finally, as the flow rate increased, the residence time in the FBR became shorter, reducing the time for crystallization. The increased flow rate also causes an increase in shear forces, which break loosely aggregated units apart. Both factors limit the crystallization rate [36,37].

Based on these phenomena, it is unclear which of the three variables, the inlet flow rate, recirculation rate, residence time, or O/A ratio, had the largest impact. The initial choice of slow feeding rates was intended to maximize residence time, which is critical for promoting crystal growth in systems with sluggish kinetics. However, this approach introduced a secondary effect with slight drift in O/A ratio during filling due to static head pressure, creating partial coupling between supersaturation and hydrodynamics. These early observations were retained because they provide insight into how hydrodynamics can cause small compositional shifts. Importantly, this revealed that relying solely on slow feeding to increase residence time is not ideal. Therefore, to gain further understanding of how the individual flow rates influenced the yield, the inlet flow rate was decoupled from the recirculation rate. Based on the results in the section above, investigating the effect of total flow rate, subsequent experiments were carried out over a batch time of 180 min, as this was deemed sufficient to capture the key phenomena.

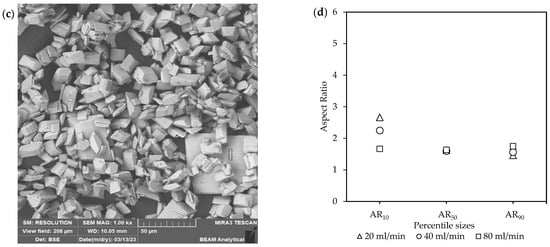

3.3.2. The Influence of Inlet Flow Rate on Yield and Crystal Characteristics

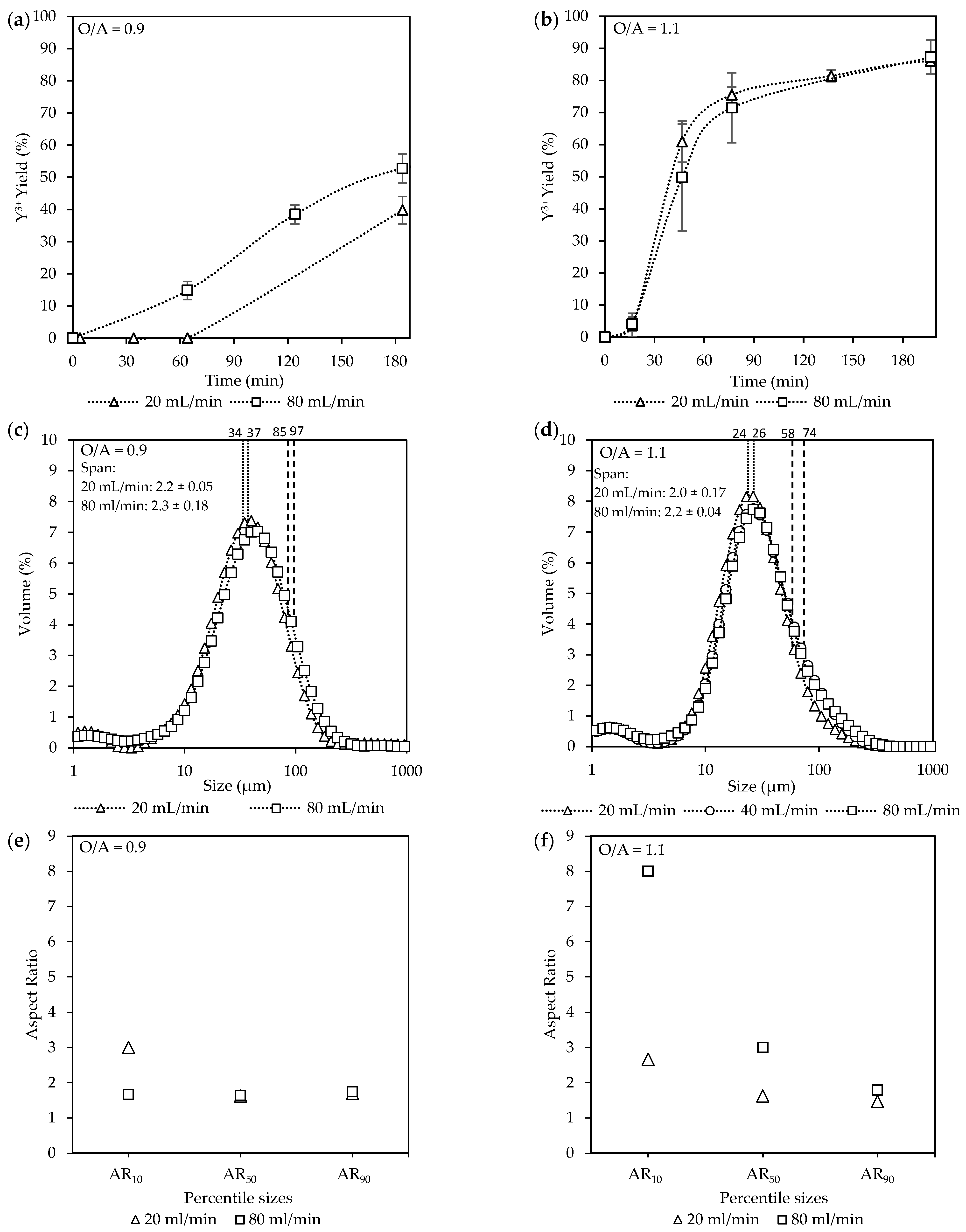

The effect of the total inlet flow rate on the crystallization of Y3+ over 180 min is shown in Figure 4, which took place at a recirculation rate of 20 mL/min. Samples were taken immediately after the reactor was filled.

Figure 4.

The effect of inlet flow rates [Exp. A1 & B] on the (a) yield; (b) CSD curves, with vertically dotted and striped lines indicating the D50 and D90 sizes, respectively; (c) a representative SEM image (see Figure S3) and (d) aspect ratios at the end of the feeding period; and lastly (e) a representative SEM image (see Figure S4) and (f) aspect ratios of the final product.

Figure 4a shows a large difference in the yield for the different flow rates. The 20 mL/min total inlet flow rate resulted in the highest yield of 86%, followed by that for 40 mL/min (63%) and 80 mL/min (40%) at the end of the 180 min batch time. Only the 20 mL/min case approached the theoretical yield of 92%. Long induction periods were observed for both 40 mL/min (>30 min) and 80 mL/min (>60 min). These observations suggest that, at higher inlet rates, a kinetic limitation increases the induction time, which implies that extending the batch time will increase the yield to the theoretical prediction.

The CSDs curves for the final product in Figure 4b shifted towards larger sizes as the inlet flow rate increased. The D50 at 20 mL/min was 24 µm, 40 mL/min with 28 µm, and 80 mL/min with 34 µm. The D90 at 20 mL/min was 58 µm, 40 mL/min with 71 µm, and 80 mL/min with 85 µm. The span remained similar for all the flow rates at ~2.

Interestingly, although no changes in the yield were seen at 40 mL/min and 80 mL/min, a small amount of crystallization did take place, as indicated by the existence of crystals via SEM analysis, shown in Figure 4c. However, the presence of these crystals was insufficient to immediately accelerate bulk crystallization due to the slow consumption of supersaturation.

In Figure 4c,d and Figure S3, the crystal characteristics at the end of the feeding times, with 20 mL/min for 16 min, 40 mL/min for 8 min, and 80 mL/min for 4 min. The existence of a few amorphous agglomerated particles among the well-defined crystals was also observed at 80 mL/min, as shown in Figure S3d,e. The crystals at the beginning of crystallization in Figure 4c are prismatic rods with matching large ARs. The slowest total inlet flow rate of 20 mL/min resulted in more elongated crystals, with AR10 = 6, compared to 40 mL/min and 80 mL/min at AR10 = ~3.3. Whereas the larger crystals at AR90 were very similar.

The crystal morphologies at the end of the batch time became more equant (shown in Figure 4e,f and Figure S4). This was reflected in the ARs, where AR10 = ~3, followed by both AR50 and AR90 at ~1.8. There was no major difference between the different inlet flow rates. Differences in the conditions at the start of the batch mainly affect the ARs of the smaller crystals early in the process. However, as crystallization continues, these effects diminish, resulting in minimal differences in the final product. The decrease in AR was attributed to the consumption of the initial high supersaturation and the improvement in the homogeneity of the mixture over time, which lowers supersaturation and slows crystallization kinetics. As a result, growth was more uniform across all crystal planes.

The reduction in the yield and slight decrease in the crystal sizes with increasing inlet flow rates mirrored the trends described in Section 3.3.1. Decoupling the total inlet flow rate and the recirculation rate resulted in a slight reduction in the yield at 180 min for 40 mL/min (69% to 63%) and 80 mL/min (53% to 40%). This indicated that, although recirculation had some effect, the largest impact on the final yield was caused by changes in the inlet flow rates. A direct comparison between the crystal sizes and characteristics with those in Section 3.3.1. could not be made, as different batch times were used. However, the sizes were very similar in both sets of experiments, indicating no major differences in the overall crystal growth behavior.

The existence of the few amorphous agglomerates at the end of the feeding period indicates that either extremely high supersaturation conditions existed or a two-step crystallization mechanism exists [38]. Both these mechanisms can include the formation of a metastable phase, which can either dissolve back into solution or transform into the stable crystalline phase [39].

The majority of the crystals exhibited preferential growth taking place along a 2D plane for the formation of the crystals within the feeding period, particularly for the smaller crystals (AR10). In antisolvent crystallization, polar antisolvents, through hydrogen bonding, can, depending on the orientation of the interacting compounds, adsorb onto the crystal surface, blocking growth sites on certain faces and directing growth along specific planes [40,41,42]. At lower inlet flow rates, the increased ethanol concentration, combined with poor mixing, can also promote the aggregation of alcohol molecules, encouraging growth along planes unaffected by the alcohol aggregate pockets [43]. The increased supersaturation further accelerates growth along these planes, leading to the formation of elongated crystals.

Based on these findings, the likely main contributor to the observed trends, including the increase in yield and the presence of longer crystals at slower inlet flow rates, appears to be either the dominance of local supersaturation at low flow rates or a small shift in the O/A ratio influencing the system.

3.3.3. The Impact of Recirculation on Yield and Crystal Characteristics

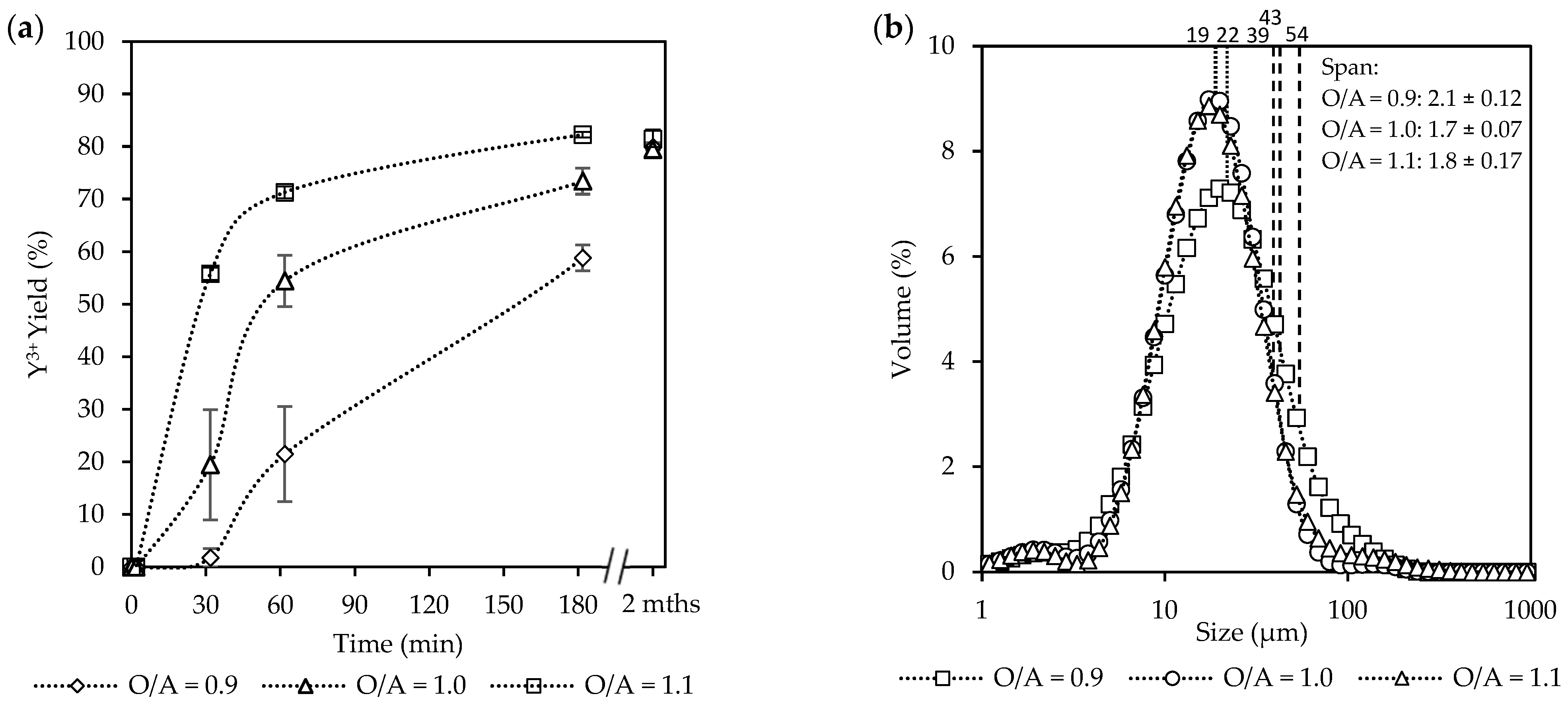

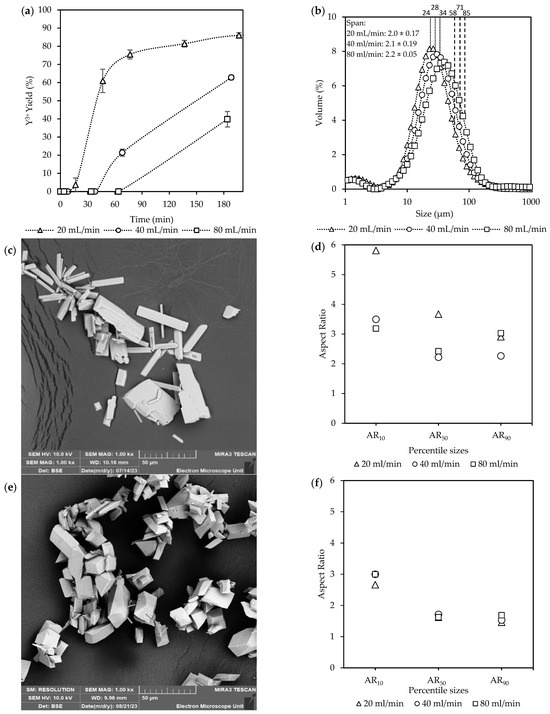

Figure 5 illustrates the effects of recirculation on the yield and crystal characteristics under these two scenarios: (i) O/A = 0.9 and a total inlet flow rate of 80 mL/min [Exp. A3 & C2], and (ii) O/A = 1.1 and a total inlet flow rate of 20 mL/min [A1 & B2].

Figure 5.

The effect of recirculation rates at O/A = 0.9 [Exp. A3 & C2] and at O/A = 1.1 [Exp. A1 & B2] on the respective (a,b) yields; (c,d) CSD curves, with vertically dotted and striped lines indicating the D50 and D90 sizes, respectively; and lastly (e,f) aspect ratios for the final product.

At O/A = 0.9, represented by Figure 5a, the yields steadily increased until the end of the batch time at 180 min, with the highest yield of 53% achieved at the recirculation rate of 80 mL/min, compared to 40% at 20 mL/min. Based on the yield measurements, the recirculation rate of 20 mL/min took over 60 min to start crystallizing, whereas by that time, the 80 mL/min case had already reached a yield of 15%. The CSD data in Figure 5c further reveal that, while the D50 values averaged around 36 µm regardless of recirculation rate, a slight broadening of the D90 values, from 85 µm to 97 µm, took place. The ARs in Figure 5e with accompanying SEM images in Figure S4, indicated subtle differences. At 20 mL/min, the AR10 values had an AR of 3, compared to 1.7 at 80 mL/min, suggesting that more intense mixing may reduce the elongation of the smallest crystals.

In contrast, at O/A = 1.1 in Figure 5b, the yields increased more rapidly, reaching a maximum of 87%, with no significant difference between recirculation rates. The onset of crystallization took place within the feeding time, as a 4% yield had already taken place by the end of filling, where 60 min later, it had rapidly increased to ±73%. The D50 values in Figure 5d averaged around 25 µm for all flow rates. A similar slight broadening of the D90 values, from 58 µm to 74 µm, was observed compared to the O/A = 0.9 conditions. Furthermore, the crystal sizes were smaller for the O/A = 1.1 experiments compared to the O/A = 0.9 experiments for both the D10 and D50 values. However, no significant difference in the span (~2) was observed for both sets of experiments.

The ARs in Figure 5f with accompanied SEM images in Figure S5 were considerably larger at 80 mL/min (AR = 8) compared to 20 mL/min (AR = 2.8). The differences between respective recirculation rates diminished for the AR50 values (AR = 3 and AR = 1.7) and were even less pronounced for the AR90 values, with both ARs = ~1.8.

At O/A = 0.9, corresponding to lower supersaturation, the increase in yield due to the higher recirculation rate is attributed to enhanced mixing. The improved mixing between ethanol and the Y3+ solution translates to an increase in the mass transfer of the ions for enhanced crystallization. Zhang et al. [44] reported that an increase in the mixing intensity increased the yield by up to 8% within 24 h and attributed it to a possible thinning of the boundary layer along with an increase in crystal attrition, which leads to more active crystallization sites. Although the overlapping CSDs suggest similar growth rates between the different recirculation rates, the faster nucleation at 80 mL/min consumed supersaturation more rapidly, resulting in comparable crystal sizes despite a higher overall yield.

Additionally, with only about 50% of the supersaturation consumed by the end of the experiment, further crystal growth would have been possible given more time. The increased mass transfer at O/A = 0.9 for 80 mL/min in Figure 5a had, however, only a marginal effect on the yield when compared to the experiments done at O/A = 1.1 in Figure 5b, where even at the slower rate of 20 mL/min, a much higher yield was observed.

At O/A = 1.1, which results in a higher supersaturation, the mass transfer limitation became less significant for the tested recirculation rates, as no significant effect on the yield was observed even at 20 mL/min. These observations were consistent with those reported by Barata & Serrano [45] and Mokone et al. [24]. However, the slight increase in the larger crystal sizes indicates that initial small variations in the number of crystals formed during nucleation can have a cumulative effect, as large variability was observed in the error bars for the yields of 80 mL/min, especially at 60 and 90 min.

In addition, the aspect ratio differences observed align with findings by Ochsenbein et al. [46], who noted that less intense mixing resulted in smaller aspect ratios. Although their study did not explain the observation, it can be reasoned that slower recirculation increases the contact time between the solvent and solute, allowing multiple crystal planes to grow at their intrinsic rates, leading to more isotropic crystals. In contrast, higher recirculation rates enhance mixing, effectively restricting growth to the preferred planes and thus producing longer crystals. As crystallization proceeds and supersaturation decreases, growth rates across various planes of a crystal become more uniform, reducing the dominance of growth in any one direction [35].

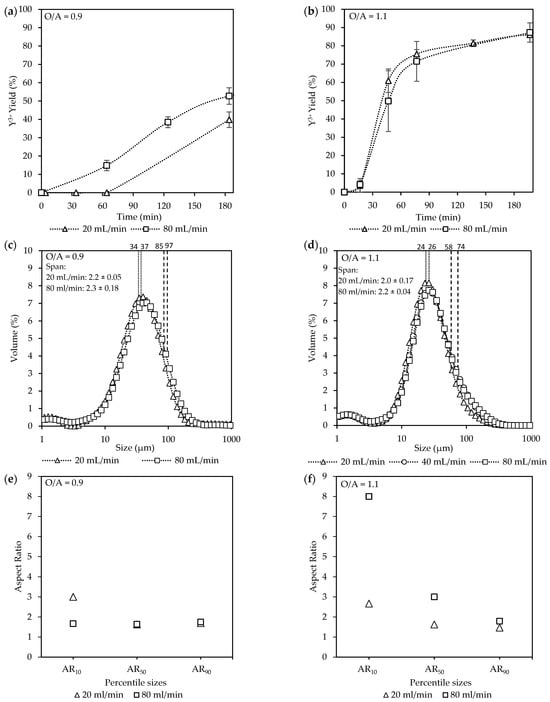

3.3.4. Influence of O/A Ratio on Crystallization Behavior in FBRs

The effect of changes in the O/A ratio on crystallization of the Y3+ product was investigated by increasing the inlet flow rates to minimize the influence of head pressure differences, thereby preventing drift in the O/A ratio. However, the Reynolds numbers only increased slightly and remained within the laminar region. Ideally, the experiments would have been conducted in the turbulent mixing region to eliminate mixing limitations. However, since the FBR design depends on the settling of larger crystals, this imposes a limit on the flow rate. Therefore, a total inlet flow rate of 200 mL/min and a recirculation rate of 170 mL/min were selected, further limited by the need to keep the distribution glass beads at the bottom of the FBR stationery.

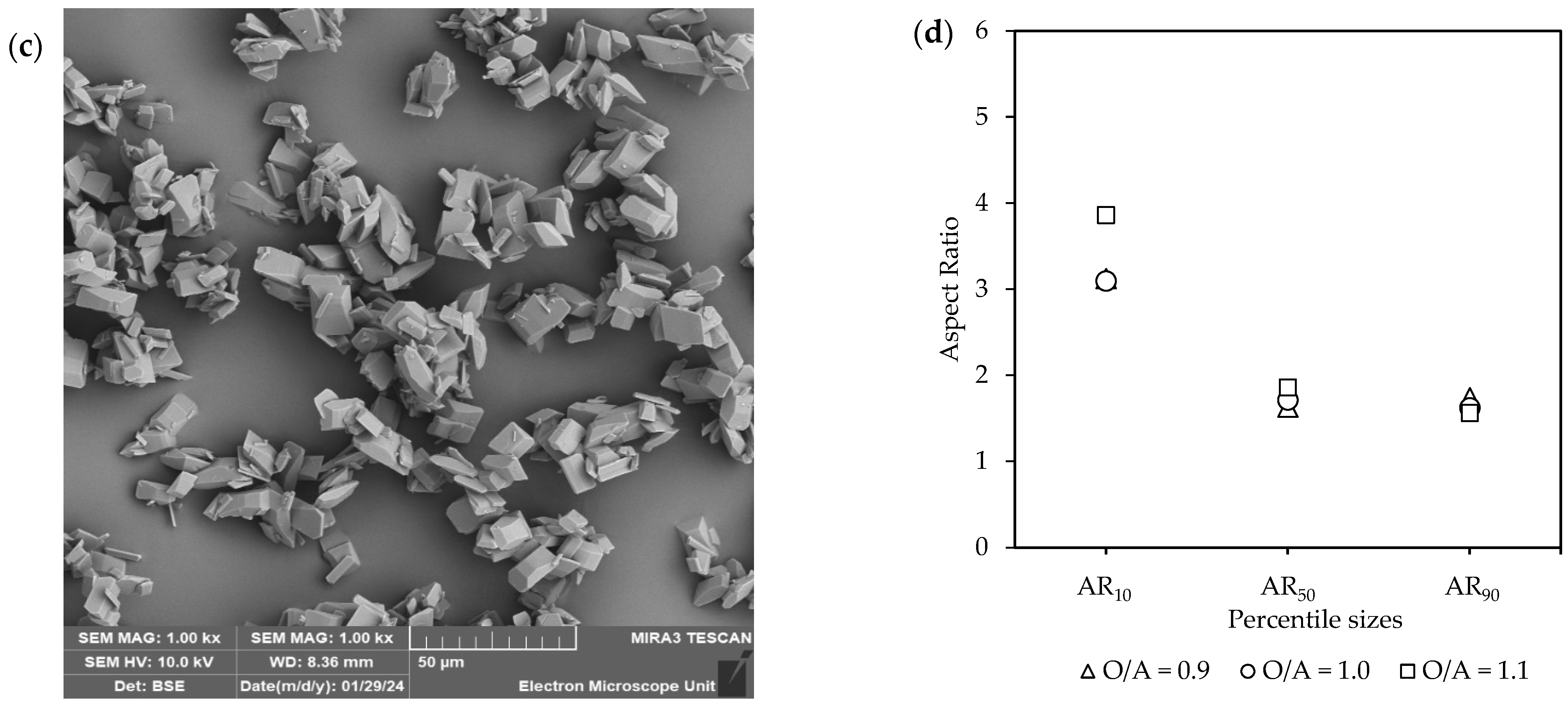

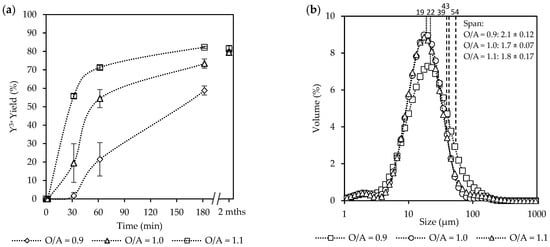

Overall, an increase in the O/A ratio (from 0.9 to 1.1) as seen in Figure 6a led to increased yields. After 30 min, the system at O/A = 1.1 had already reached 56%, whereas much lower yields were observed for O/A = 1.0 (19%) and O/A = 0.9 (2%). After 180 min, the yield was 82% at O/A = 1.1, whereas O/A = 1.0 and 0.9 resulted in yields of 73% and 59%, respectively. However, effluent samples that were stored and analyzed after two months showed that final yields had increased to 79% and 80% for O/A ratios of 1.0 and 0.9, respectively. Although Figure 2 illustrates that the theoretical yields for O/A ratios of 0.9 and 1.1 are very similar, the 2-month-old samples confirm that crystallization continued beyond the initial batch period, but the exact time required to reach these yields was not determined. Because the supernatant was filtered before storage, no solids were present initially, meaning the later increase must have resulted from new crystallization from the remaining dissolved species rather than growth of existing crystals.

Figure 6.

The effect of O/A ratio [Exp. D2–4] on the (a) yield; (b) CSD curves, with vertically dotted and striped lines indicating the D50 and D90 sizes, respectively; (c) a representative SEM image (see Figure S6); and (d) aspect ratios.

SEM images of crystals recovered after the extended standing period (Figure S7) confirm that the later yield increase was not associated with a metastable phase transformation, as the morphology remained consistent with that observed after 3 h, differing only in size. This suggests that the solution stayed supersaturated after 3 h and nucleation eventually occurred during the standing period. Combined with the slow progression observed during the experiments, this indicates that the process is initially nucleation-limited, followed by a growth limitation once nuclei are present. While O/A = 0.9 and 1.0 required extended time to approach equilibrium, O/A = 1.1 achieved yields close to the theoretical prediction within 3 h, showing the sensitivity of the system to small changes in O/A ratio, which causes substantial changes in the supersaturation.

The supersaturation (ST) carried out by using OLI Stream Analyzer shows an increase in the supersaturation as the O/A ratios increase, with ST = 1.92 × 104 (O/A = 0.9), 1.03 × 105 (O/A = 1.0), and 3.7 × 105 (O/A = 1.0). However, these values reflect supersaturations under perfect mixing conditions. Whereas in the present system, the mixing remained within the laminar region, resulting in large, persistent supersaturation gradients rather than a single uniform value. Because these gradients cannot be directly quantified, the theoretical ST values should be viewed as lower-bound estimates of the actual local driving forces.

Despite the large increase in yield at O/A = 1.1, completion of crystallization was not instantaneous, and the crystals had similar characteristics to those formed at lower supersaturations. These results are consistent with the observations of Sibanda et al. [11] for the crystallization of Nd2(SO4)3·8H2O, where high yields (~90%) were theoretically expected at a lower O/A ratio (O/A = 0.6). However, an increase in the O/A ratio (O/A > 1.2) was required to reach yields above 90% in 2.5 h. Schall [47] reported that altering the O/A ratio by just 1% can significantly affect crystallization kinetics and final yields. Since alcohol concentration is the primary driver of supersaturation, its influence on nucleation and growth rates is unsurprising, leading to faster crystallization at higher O/A ratios. Collectively, these findings emphasize that while higher O/A ratios enable practical recovery within short timeframes by reducing nucleation barriers, lower ratios remain strongly limited by both nucleation and subsequent growth, requiring extended periods for completion.

The CSDs in Figure 6b show no significant differences in the overall sizes (D50), centered around 21 µm, that were observed for all of the O/A ratios, indicating that the more intense mixing was effective in distributing the supersaturation more uniformly. This observation aligns with the findings of Brown & Ni [48], who reported that the crystal growth rate remained relatively constant up to an O/A ratio of 1.5. However, a slight broadening of the right shoulder leading to a widening of the span from 2.1 (O/A = 0.9) to 1.7 (O/A = 1.1) was observed toward larger crystal sizes (D90) as the O/A ratio decreased with O/A = 1.1 (39 µm), O/A = 1.0 (43 µm), and O/A = 0.9 (54 µm). This is likely due to growth being favored over nucleation at the lower supersaturation.

Figure 6c,d, accompanied by Figure S6, illustrates SEM images along with the corresponding aspect ratios. A variety of different shapes and sizes were observed, with intergrowth and agglomeration being common. In terms of the ARs, the most notable difference was observed at AR10, where O/A = 1.1 resulted in longer crystals (AR = 4) compared to the lower O/A ratios (AR = ~3). However, the aspect ratios of the larger crystals (AR50 and AR90) were similar. Furthermore, although much faster crystallization kinetics were observed at the higher O/A ratio, the resulting crystals did not show any reduction in product quality, such as a large decrease in crystal size or a change in morphology to needles or plates.

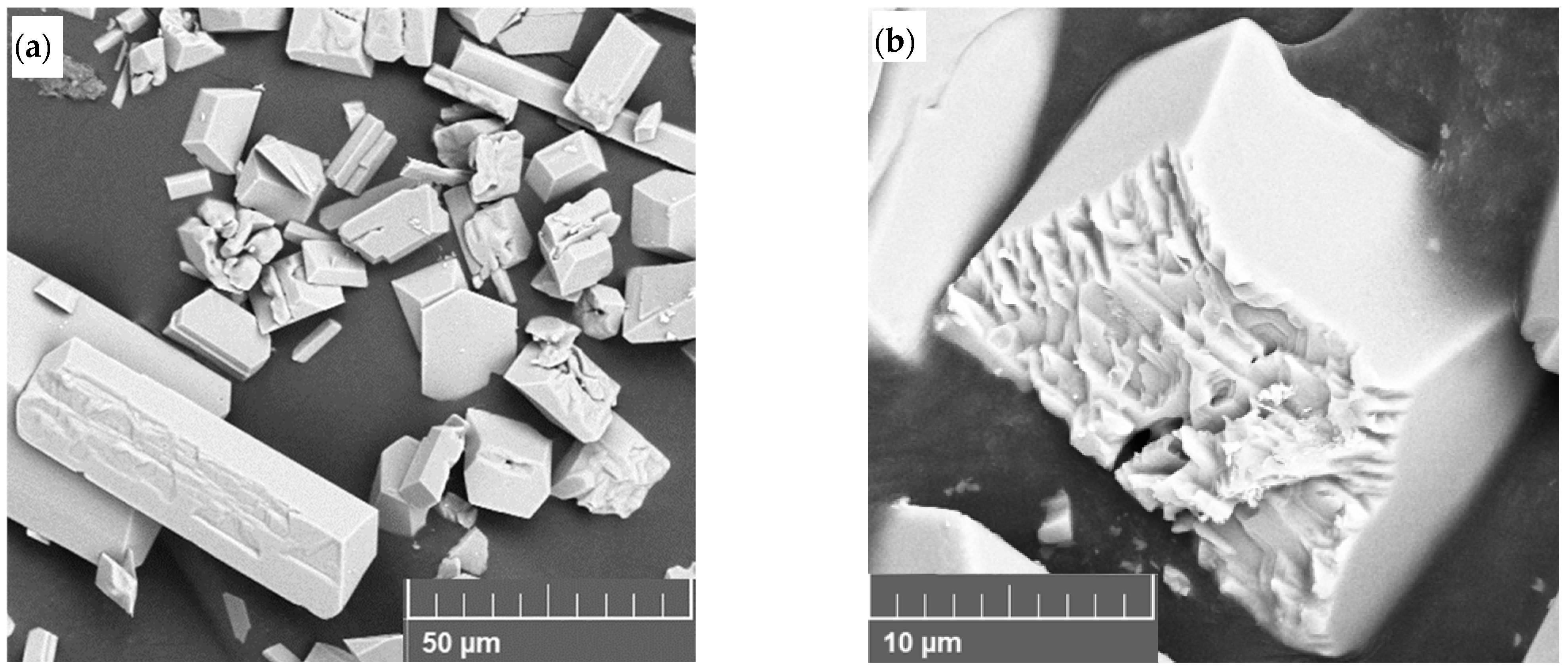

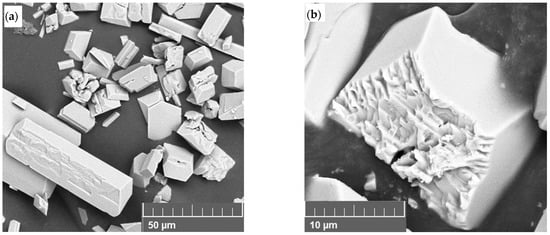

The progression of growth on the crystal faces was observed at 30 min, as shown in Figure 7. The growth predominantly seemed to follow an ordered pattern, eventually leading to the formation of smooth faces. The presence of discernible growth layers at this intermediate stage suggests a relatively low driving force, which slowed the crystallization process enough for such features to be captured. In some instances, individual crystals underwent intergrowth or twinning. This led either to the formation of larger, well-defined single crystals or to agglomerates where the distinct morphology of the primary crystallites remained visible. Such outcomes are likely driven by interfacial energies that favor the combination and agglomeration of collided crystals, which further grow as a single entity [35].

Figure 7.

SEM images showing active growth of the crystals, with (a) at a total inlet flow rate of 20 mL/min and recirculation rate at 40 mL/min after 30 min, and (b) at a total inlet flow rate of 20 mL/min and recirculation rate at 80 mL/min after 60 min.

A comparison of Figure 3a and Figure 6a reveals similarities in the yield at 180 min. The differences in yields between Figure 3a and Figure 4a are attributed to changes in the O/A ratio rather than the flow rates. Yields in Figure 4a and Figure 6a reveal that the higher flow rates for Figure 6a have a positive effect on the experiments at O/A = 0.9 and 1.0. This improvement in yield is attributed to an increase in mass transfer due to the increased flow rates, which improves the initial mixing of the solvent and antisolvent [49,50].

Alvarez & Myerson [51] found that an increase in the mixing intensity led to a higher recovery of the target solute. However, at O/A = 1.1, yields were higher at slower flow rates, as seen in Figure 4a, due to the increase in the O/A ratio, which reached 1.1 by the end of the feeding period. This resulted in a higher supersaturation, leading to crystallization under mixing conditions that were no longer rate-limiting. Shakibania et al. [52] found that in potash crystallization using acetone and 2-propanol as antisolvents, increasing the addition rate improved the yield up to a maximum of 83% (acetone at 10 mL/min) and 79% (2-propanol at 5 mL/min). However, further increases beyond this point led to a decline in yield.

In experiments with lower flow rates shown in Figure 3b, Figure 4b and Figure 5b, smaller crystals were observed as the O/A ratio increased. Poor mixing in these low flow rate experiments likely contributed to smaller crystal formation by creating localized supersaturation hotspots [53,54].

Compared to the high flow rate data in Figure 6b, the CSDs from the low flow rate experiments in Figure 3b and Figure 4b were slightly broader, with larger D50 and D90 values. This difference was attributed to more effective mixing between the aqueous solution and ethanol at high flow rates, which resulted in a more uniform distribution of supersaturation and, consequently, more consistent crystallization kinetics.

Adjusting the O/A ratio alters several physical and chemical properties, as shown in Table 3. Although each change may have a small individual impact, their combined effects significantly influence crystallization dynamics. Some changes have opposing effects on crystallization kinetics. For example, viscosity increases slightly with O/A ratio, which can slow mixing and mass transfer, while a lower dielectric constant reduces solubility, increasing supersaturation and accelerating nucleation [55]. Similarly, changes in surface tension and Gibbs free energy reduce energy barriers for crystallization [56]. These combined effects influence both nucleation and growth dynamics, highlighting the sensitivity of the system to small compositional changes. Importantly, Table 3 also shows that heat capacity decreases as O/A ratio increases, indicating that the system becomes more sensitive to thermal input [57].

Table 3.

The thermodynamic liquid properties at [Y3+] = 0.87 g/L according to OLI Studio.

Low yields at small O/A ratios suggest that the system is in the metastable zone with nucleation being rate-limiting, requiring increased supersaturation to initiate crystallization and improve yields. Crystallization of Y2(SO4)3·8H2O can remain relatively slow even at high supersaturation levels, as observed by Chivavava et al. [20], where increasing supersaturation from 555 to 6.5 × 104 only increased yields from ~35% to ~60% over a 2 h batch time. Supersaturation typically impacts nucleation rates more than growth rates due to the higher kinetic order of nucleation [58]. This slight improvement in the yield even at high supersaturations, therefore, suggests that crystallization of Y2(SO4)3·8H2O is influenced by factors beyond supersaturation alone, such as growth rate limitations.

A brief comparison with the results of Korkmaz et al. [8] provides additional context for the slow crystallization observed in the present work. Their stirred-tank experiments reported some crystallization at O/A = 0.56 and somewhat higher recoveries at O/A = 1.1. In the present FBR system, no crystallization occurred at O/A = 0.56, which aligns with the thermodynamic predictions for the tested composition (Figure 2), and crystallization at O/A = 1.1 proceeded more slowly than predicted. Direct quantitative comparison is not possible because the two studies differ substantially in reactor configuration, mixing intensity, solution composition, and analytical methods. Nevertheless, both studies observed incomplete crystallization under theoretically favorable conditions, supporting the broader conclusion that the kinetics of Y2(SO4)3·8H2O crystallization are slow and sensitive to supersaturation development and reactor hydrodynamics.

To determine whether these growth limitations stem from nucleation or crystal growth, it is necessary to examine the roles of nucleation kinetics, mass transfer, and crystal growth processes. If nucleation kinetics were the only limiting factor, existing REE sulfate crystals would likely promote secondary nucleation by lowering the energy barrier [14].

Additionally, the fines seen in Figure S2 indicate that crystal fragmentation may have occurred during recirculation through the narrow stainless steel non-return valve, further enhancing secondary nucleation. Hoffmann et al. [59] showed that the secondary nucleation rate can be 6 times higher in order of magnitude than the primary nucleation rate in various antisolvent crystallization systems, even at high supersaturations. Furthermore, the dilution associated with antisolvent addition can reduce the supersaturation driving force, leading to longer induction times and delayed nucleation [34]. Together, these observations suggest that, in the Y3+ system, crystallization may be significantly delayed until secondary nucleation takes place.

The well-defined crystal morphology in Figure 7, extended growth times, and the slow progression to the maximum yield suggests that under the higher O/A ratio conditions, the process is limited by crystal growth after the initial consumption of supersaturation by nucleation. Additionally, growth was only marginally influenced by mixing at low supersaturations.

Additionally, crystallization at lower O/A ratios would also have been delayed by the formation of a possible metastable amorphous phase, as shown in Figure S3d,e. In similar observations made in a separate exploration study done in a stirred-tank reactor outlined in the Supplementary Materials, with results shown in Figure S8, the existence of an amorphous phase was observed at much lower supersaturation conditions than those used in the present work. These results also indicated an initial amorphous phase existing before the formation of the well-defined crystals. Other systems with similar mechanisms include calcium carbonate, calcium phosphate, and calcium sulfate [60,61,62]. These findings suggest that such phases may play a role in delaying nucleation and promoting sluggish kinetics. However, no in situ characterization was performed in this work to confirm their presence.

The crystallization kinetics of the system, therefore, appear to be governed by the combined effects of supersaturation dynamics, nucleation mechanisms, mass transfer and growth rate limitations, and the formation of initial metastable phases. Nevertheless, this section highlights that higher O/A ratios promote crystallization, leading to higher yields and smaller crystals with a narrower span, within a markedly shorter time.

While the several phenomena may influence crystallization, the present interpretation remains qualitative. Experimental trends indicate that crystallization can be both nucleation-limited and growth-limited, depending on operating conditions. At lower O/A ratios, extended induction times suggest nucleation is the dominant rate-limiting step, likely due to either intrinsic nucleation barriers or the formation of a metastable amorphous phase. Whereas at higher O/A ratios, nucleation occurs rapidly but overall crystallization remains slow, implying growth limitation. This dual behavior highlights that the rate-determining step shifts with changes in supersaturation and hydrodynamics. While kinetic modeling was beyond the scope of this work, these observations strongly support the coexistence of multiple limitations under different conditions.

Although this study focused on Y2(SO4)3·8H2O, the benefits of fluidized bed reactors are also applicable to other REE sulfates. Therefore, the operational insights gained here, including the sensitivity of crystallization kinetics to O/A ratio and flow conditions, can inform strategies for other REEs sulfates. However, quantitative differences in solubility, hydration state, and lattice energy among REEs may lead to variations in induction times, metastable phase formation, and growth rates.

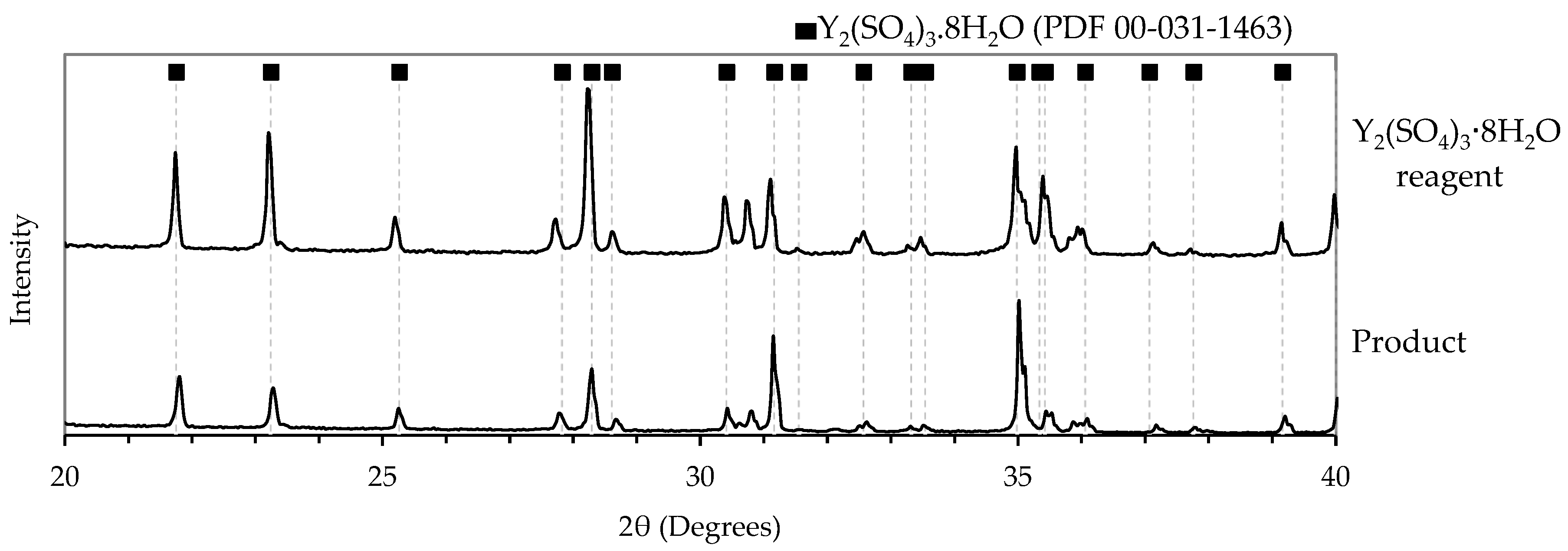

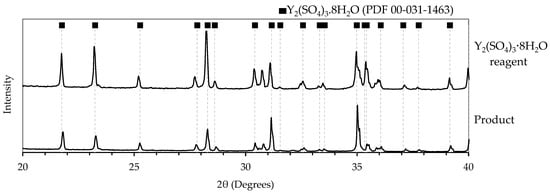

3.3.5. Product Characterization

The XRD confirmed the crystalline phase as Y2(SO4)3·8H2O, shown in Figure 8, matching both the Y2(SO4)3·8H2O reagent and its reference peaks (PDF 00-031-1463). This observation also agrees with the thermodynamic predictions, shown in Figure 2, and results from previous solubility studies; therefore, the hydration state was not re-verified experimentally [19]. Quantitative characterization of the amorphous fraction observed in SEM images (Figures S3 and S8) was not performed. No purification studies were performed, as no external impurities were introduced; however, minor inclusions such as residual mother liquor or ethanol cannot be ruled out and were not quantified in this exploratory work.

Figure 8.

XRD spectra of the solid yttrium sulfate product.

4. Conclusions

This work confirms the suitability of FBRs for antisolvent systems, as they offer operational flexibility across a range of crystallization kinetics, while also providing deeper insight into the behavior of Y2(SO4)3·8H2O and other REEs in the presence of antisolvents.

The recovery of Y2(SO4)3·8H2O from an aqueous solution using ethanol as the antisolvent in an FBR was successfully achieved. Long batch times (>3 h) were required to achieve the high yields predicted by thermodynamic simulations due to the slow crystallization kinetics. Therefore, process design must ensure sufficient capacity for extended batch times to reach the necessary high yields.

Of the process variables studied, the O/A ratio had the most significant impact on yield and crystal sizes. An increase in O/A ratio from 0.9 to 1.1 resulted in a yield increase from 59% to 88% over 3 h, along with a decrease in the crystal size (D50) from 37 µm to 19 µm. At low O/A ratios, secondary nucleation and possible formation of a metastable phase contributed to prolonged induction times, while at higher O/A ratios, solute incorporation at the crystal surface appeared to dominate, suggesting growth-related limitations.

In contrast, changes in the recirculation rate had a relatively minor effect on both crystallization time and yield. At lower supersaturation levels, increased recirculation only slightly improved the yield, due to an increase in mass transfer. At higher supersaturation levels, the effect of recirculation was negligible, as crystallization occurred fast and was no longer limited by mass transfer. No significant differences were observed in the final crystal morphologies across the range of O/A ratios and recirculation rates tested. This consistency suggests that crystal habit is governed primarily by intrinsic molecular structure and growth mechanisms.

The effect of varying inlet flow rates could not be independently assessed due to simultaneous shifts in the O/A ratio caused by changes in static head pressure. This coupling of variables masked the individual influence of inlet flow rate, making it difficult to isolate its effect on crystallization performance.

Overall, the results highlight how antisolvent crystallization of Y2(SO4)3·8H2O is influenced by process variables. Controlling the O/A ratio offers a practical means to regulate crystallization to achieve higher yields and desirable crystal sizes within reasonable timescales. However, the system exhibits multiple kinetic limitations, including slow nucleation, growth constraints, and possible metastable phase formation, indicating that crystallization behavior cannot be attributed solely to the O/A ratio and its effect on supersaturation.

Additionally, this study establishes the FBR as a suitable and effective system for antisolvent crystallization, achieving high yields, reproducible crystal properties, and scalability by ensuring uniform suspension of particles and consistent contact between the liquid and solid phases, enabling effective recovery even from relatively dilute streams. These findings confirm the suitability of an FBR for antisolvent crystallization and provide a basis for tailoring outcomes toward either yield or crystal growth depending on process objectives.

At the same time, the results reveal that antisolvent crystallization of Y2(SO4)3·8H2O is governed by kinetic barriers, with slow nucleation, growth limitations, and possible metastable phase formation acting as rate-limiting steps. Addressing these limitations through further kinetic studies, improved mixing and continuous operation will advance process understanding and optimization.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/chemengineering10020021/s1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.S., J.C. and A.E.L.; methodology, J.S., J.C. and A.E.L.; software, J.S.; validation, J.S., J.C. and A.E.L.; formal analysis, J.S.; investigation, J.S.; resources, A.E.L. and J.C.; data curation, J.S.; writing—original draft preparation, J.S.; writing—review and editing, J.S., J.C. and A.E.L.; visualization, J.S.; supervision, J.C. and A.E.L.; project administration, J.C. and A.E.L.; funding acquisition, A.E.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors wish to acknowledge financial support from the University of Cape Town through the Crystallization and Precipitation Research Unit and South Africa’s National Research Foundation (grant #120830).

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would also like to acknowledge the Chemical Engineering Analytical Laboratory (ICP-OES, laser diffraction), Electron Microscopy Unit (SEM), and The Catalysis Institute for analysis (XRD) at the University of Cape Town.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest that influenced the work reported in this paper.

References

- Behrsing, T.; Blair, V.L.; Jaroschik, F.; Deacon, G.B.; Junk, P.C. Rare Earths—The Answer to Everything. Molecules 2024, 29, 688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voncken, J.H.L. The Rare Earth Elements: An Introduction; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filho, W.L.; Kotter, R.; Özuyar, P.G.; Abubakar, I.R.; Eustachio, J.H.P.P.; Matandirotya, N.R. Understanding Rare Earth Elements as Critical Raw Materials. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.-L.; Fan, H.-R.; Liu, X.; Meng, J.; Butcher, A.R.; Yann, L.; Yang, K.-F.; Li, X.-C. Global rare earth elements projects: New developments and supply chains. Ore Geol. Rev. 2023, 157, 105428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Zheng, X.; Ji, B.; Xu, Z.; Bao, S.; Zhang, X.; Li, G.; Mei, J.; Li, Z. Green recovery of rare earth elements under sustainability and low carbon: A review of current challenges and opportunities. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2024, 330, 125501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opare, E.O.; Struhs, E.; Mirkouei, A. A comparative state-of-technology review and future directions for rare earth element separation. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 143, 110917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erust, C.; Karacahan, M.K.; Uysal, T. Hydrometallurgical Roadmaps and Future Strategies for Recovery of Rare Earth Elements. Miner. Process. Extr. Metall. Rev. 2022, 44, 436–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korkmaz, K.; Alemrajabi, M.; Rasmuson, Å.C.; Forsberg, K.M. Separation of valuable elements from NiMH battery leach liquor via antisolvent precipitation. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2020, 234, 115812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, E.M.; Kaya, Ş.; Dittrich, C.; Forsberg, K. Recovery of Scandium by Crystallization Techniques. J. Sustain. Metall. 2019, 5, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonn, J.; Fuchs, A.R.; Libuda, L.; Jupke, A. Controlling Crystal Growth of a Rare Earth Element Scandium Salt in Antisolvent Crystallization. Crystals 2024, 14, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sibanda, J.; Chivavava, J.; Lewis, A.E. Crystal Engineering in Antisolvent Crystallization of Rare Earth Elements (REEs). Minerals 2022, 12, 1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nobuaki, S.; Yuezhou, W.; Michio, N.; Masanori, T. Recovery of samarium and neodymium from rare earth magnet scraps by fractional crystallization method. Metall. Rev. MMIJ 1998, 15, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Stetson, C.; Prodius, D.; Lee, H.; Orme, C.; White, B.; Rollins, H.; Ginosar, D.; Nlebedim, I.C.; Wilson, A.D. Solvent-driven fractional crystallization for atom-efficient separation of metal salts from permanent magnet leachates. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 3789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mullin, J.W. Crystallization; Butterworth Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Kaya, Ş.; Peters, E.; Forsberg, K.; Dittrich, C.; Stopic, S.; Friedrich, B. Scandium Recovery from an Ammonium Fluoride Strip Liquor by Anti-Solvent Crystallization. Metals 2018, 8, 767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, J.; Kim, W.-S.; Park, S.-I.; Yoon, T.-S.; Chung, B.H. Synthesis and Characterization of Various-Shaped C60 Microcrystals Using Alcohols as Antisolvents. J. Phys. Chem. C 2010, 114, 12976–12981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, E.M.; Svärd, M.; Forsberg, K. Impact of process parameters on product size and morphology in hydrometallurgical antisolvent crystallization. CrystEngComm 2022, 24, 2851–2866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takiyama, H.; Otsuhata, T.; Matsuoka, M. Morphology of NaCl Crystals in Drowning-Out Precipitation Operation. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 1998, 76, 809–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sussens, J.; Chivavava, J.; Lewis, A.E. The recovery of yttrium sulfate through antisolvent crystallization using alcohols. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2024, 346, 127459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chivavava, J.; Petersen, J.; Lewis, A.E. Comparing the recovery of rare earth elements from ion-adsorption clay leach solutions using various precipitants. J. S. Afr. Inst. Min. Metall. 2024, 124, 737–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korkmaz, K.; Alemrajabi, M.; Rasmuson, Å.; Forsberg, K. Recoveries of Valuable Metals from Spent Nickel Metal Hydride Vehicle Batteries via Sulfation, Selective Roasting, and Water Leaching. J. Sustain. Metall. 2018, 4, 313–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangwal, K.; Polak, W.Z. Antisolvent crystallization kinetics of different substances in solvent–antisolvent systems. J. Cryst. Growth 2024, 628, 127562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maharaj, C.; Chivavava, J.; Lewis, A. Treatment of a highly-concentrated sulphate-rich synthetic wastewater using calcium hydroxide in a fluidised bed crystallizer. J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 207, 378–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokone, T.P.; van Hille, R.P.; Lewis, A.E. Metal sulphides from wastewater: Assessing the impact of supersaturation control strategies. Water Res. 2012, 46, 2088–2100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, C.K.; Sathiyamoorthy, D. Fluid Bed Technology in Materials Processing; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, W.-C. Handbook of Fluidization and Fluid-Particle Systems, 1st ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Seckler, M.M. Crystallization in Fluidized Bed Reactors: From Fundamental Knowledge to Full-Scale Applications. Crystals 2022, 12, 1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-S.; Shih, Y.-J.; Huang, Y.-H. Remediation of lead (Pb(II)) wastewater through recovery of lead carbonate in a fluidized-bed homogeneous crystallization (FBHC) system. Chem. Eng. J. 2015, 279, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doki, N.; Kubota, N.; Yokota, M.; Chianese, A. Determination of Critical Seed Loading Ratio for the Production of Crystals of Uni-Modal Size Distribution in Batch Cooling Crystallization of Potassium Alum. J. Chem. Eng. Jpn. 2002, 35, 670–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chianese, A.; Kramer, H.J.M. Industrial Crystallization Process Monitoring and Control; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, S.; Yang, P.; Gao, Z.; Li, Z.; Fang, C.; Gong, J. Recent progress in antisolvent crystallization. CrystEngComm 2022, 24, 3122–3135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahu, P.; Gao, B.; Bhatti, S.; Capellades, G.; Yenkie, K.M. Process Design Framework for Inorganic Salt Recovery Using Antisolvent Crystallization (ASC). ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2023, 12, 154–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Threlfall, T.L.; De’Ath, R.W.; Coles, S.J. Metastable Zone Widths, Conformational Multiplicity, and Seeding. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2013, 17, 578–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ó’Ciardhá, C.T.; Frawley, P.J.; Mitchell, N.A. Estimation of the nucleation kinetics for the anti-solvent crystallisation of paracetamol in methanol/water solutions. J. Cryst. Growth 2011, 328, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunagawa, I. Crystals: Growth, Morphology and Perfection; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Richard, D.; Speck, T. The role of shear in crystallization kinetics: From suppression to enhancement. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 14610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamankhan, P. Solid structures in a highly agitated bed of granular materials. Appl. Math. Model. 2012, 36, 414–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohagheghi, M.; Askari, M. Kinetics of the antisolvent crystallization of manganese sulfate monohydrate from a pregnant leach solution. Chem. Pap. 2023, 78, 1529–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorat, A.A.; Dalvi, S.V. Liquid antisolvent precipitation and stabilization of nanoparticles of poorly water soluble drugs in aqueous suspensions: Recent developments and future perspective. Chem. Eng. J. 2012, 181–182, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangwal, K. Nucleation and Crystal Growth: Metastability of Solutions and Melts; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Croker, D.M.; Kelly, D.M.; Horgan, D.E.; Hodnett, B.K.; Lawrence, S.E.; Moynihan, H.A.; Rasmuson, Å.C. Demonstrating the Influence of Solvent Choice and Crystallization Conditions on Phenacetin Crystal Habit and Particle Size Distribution. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2015, 19, 1826–1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Shan, J.; Chen, D.; Li, H. Tuning the Crystal Habits of Organic Explosives by Antisolvent Crystallization: The Case Study of 2,6-dimaino-3,5-dinitropyrazine-1-oxid (LLM-105). Crystals 2019, 9, 392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.; Parameswaran, S.; Choi, J.H. Understanding alcohol aggregates and the water hydrogen bond network towards miscibility in alcohol solutions: Graph theoretical analysis. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2020, 22, 17181–17195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zheng, S.; Du, H.; Xu, H.; Wang, S.; Zhang, Y. Improved precipitation of gibbsite from sodium aluminate solution by adding methanol. Hydrometallurgy 2009, 98, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barata, P.A.; Serrano, M.L. Salting-out precipitation of potassium dihydrogen phosphate (KDP): IV. Characterisation of the final product. J. Cryst. Growth 1998, 194, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochsenbein, D.R.; Vetter, T.; Morari, M.; Mazzotti, M. Agglomeration of Needle-like Crystals in Suspension. II. Modeling. Cryst. Growth Des. 2015, 15, 4296–4310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schall, J.M. Growth and Nucleation Kinetics in Continuous Antisolvent Crystallization Systems. Ph.D. Thesis, Department of Chemical Engineering, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, C.J.; Ni, X.W. Evaluation of Growth Kinetics of Antisolvent Crystallization of Paracetamol in an Oscillatory Baffled Crystallizer Utilizing Video Imaging. Cryst. Growth Des. 2011, 11, 3994–4000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, A.P. Characterisation of Turbulent Mixing and Its Influence on Antisolvent Crystallisation. Ph.D. Thesis, Department of Chemical and Process Engineering, University of Strathclyde, Glasgow, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, R.; Sefcik, J.; Lue, L. Modeling Diffusive Mixing in Antisolvent Crystallization. Cryst. Growth Des. 2022, 22, 2192–2207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvarez, A.J.; Myerson, A.S. Continuous Plug Flow Crystallization of Pharmaceutical Compounds. Cryst. Growth Des. 2010, 10, 2219–2228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakibania, S.; Sundqvist-Öqvist, L.; Rosenkranz, J.; Ghorbani, Y. Application of Anti-Solvent Crystallization for High-Purity Potash Production from K-Feldspar Leaching Solution. Processes 2024, 12, 1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hash, J.; Okorafor, O.C. Crystal size distribution (CSD) of batch salting-out crystallization process for sodium sulfate. Chem. Eng. Process. Process Intensif. 2008, 47, 622–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Wang, J.-X.; Wang, Q.-A.; Chen, J.-F.; Yun, J. Controlled Liquid Antisolvent Precipitation of Hydrophobic Pharmaceutical Nanoparticles in a Microchannel Reactor. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2007, 46, 8229–8235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amari, S.; Takahashi, R.; Hosokawa, M.; Takiyama, H. Improving the quality of crystalline particles and productivity during anti-solvent crystallization through continuous flow with high shear stress under low supersaturation condition. Adv. Powder Technol. 2024, 35, 104493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, G.; Lencka, M.M.; Eslamimanesh, A.; Wang, P.M.; Anderko, A.; Riman, R.E.; Navrotsky, A. Rare earth sulfates in aqueous systems: Thermodynamic modeling of binary and multicomponent systems over wide concentration and temperature ranges. J. Chem. Thermodyn. 2019, 131, 49–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myerson, A.S. Handbook of Industrial Crystallization; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Mina-Mankarios, G. Crystallization Kinetics of Sodium Sulphate in a Salting Out Msmpr Crystallizer System Na2SO4/H2S04/H2O/MeOH. Ph.D. Thesis, Faculty of Applied Science, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann, J.; Flannigan, J.; Cashmore, A.; Briuglia, M.L.; Steendam, R.R.E.; Gerard, C.J.J.; Haw, M.D.; Sefcik, J.; Ter Horst, J.H. The unexpected dominance of secondary over primary nucleation. Faraday Discuss. 2022, 235, 109–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.W.; Kim, Y.Y.; Christenson, H.K.; Meldrum, F.C. A new precipitation pathway for calcium sulfate dihydrate (gypsum) via amorphous and hemihydrate intermediates. Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 504–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorozhkin, S.V. Amorphous calcium (ortho)phosphates. Acta Biomater. 2010, 6, 4457–4475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarkson, J.R.; Price, T.J.; Adams, C.J. Role of metastable phases in the spontaneous precipitation of calcium carbonate. J. Chem. Soc. Faraday Trans. 1992, 88, 243–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.