Abstract

Maintaining stable pressure in the oxidation–compressor section of purified terephthalic acid (PTA) plants is essential for ensuring efficient and reliable operation. Conventional single-loop proportional integral derivative (PID) controllers frequently perform inadequately because of the large pressure drop between the compressor discharge and reactor inlet, which should ideally remain at approximately 1.2 kg/cm2 above the reactor pressure setpoint but can reach up to 2.8 kg/cm2 due to downstream vapor-phase disturbances. Through this study, we aimed to address this issue by developing a robust cascade pressure control strategy to improve pressure stability and reduce energy losses. Dynamic process models were constructed using system identification techniques to represent real plant behavior, and the best-performing models—identified based on minimum root mean square error (RMSE)—were determined using the Wade method for pressure indicating controller PIC-101, the Lilja method for PIC-102, and the Smith method for pressure differential indicating controller PDIC-101. The proposed cascade configuration was tuned using the Lopez ISE method and evaluated under representative disturbance scenarios. The results showed that the cascade controller significantly improved pressure control, enhanced disturbance rejection, and lowered the risk of reactor shutdowns compared with the conventional proportional-integral PI-based approach. Overall, this study demonstrated that model-driven cascade control can enhance robustness, operational reliability, and energy efficiency in large-scale PTA oxidation processes.

1. Introduction

Stable dynamic performance under variable operating conditions is essential in modern process industries, where control strategies play a critical role in product quality, energy efficiency, and operational reliability [1]. Cascade control is widely recognized as one of the most robust strategies due to its enhanced disturbance rejection capability. Numerous studies have demonstrated its effectiveness across a range of chemical engineering applications. Kaya et al. developed an improved cascade structure for temperature and flow control in industrial furnaces [2]. Ahmed et al. applied cascade control to maintain temperature stability in continuous stirred tank reactors (CSTRs) [3], while Karimi and Jahanmiri integrated nonlinear modeling into cascade control for multi-effect falling film evaporators [4]. Later, Kristanto and Hermawan demonstrated superior cascade performance over PI control in plug flow reactor (PFR) heater systems [5]. More recently, Singha introduced a dual Smith-predictor-based cascade scheme for delay-dominant chemical processes [6], and Torrico proposed an ideal cascade structure for FOPDT systems in series [7].

Recent advances in advanced control research have extended beyond conventional unit operations such as thermal networks and compression systems. Wang et al. developed a reinforcement-learning fuzzy control strategy for differential pressure control in district cooling systems [8], while Li et al. combined PI and model predictive control (MPC) for pressure optimization in multi-source backplane cooling networks [9]. Kadirov applied cascade control for simultaneous pressure and temperature stabilization in polyvinyl chloride (PVC) reactor units [10]. Similarly, Kurz and Brun highlighted the vital role of pressure control in industrial compression systems [11].

Despite these advancements, most existing research focuses on regulating the temperature, concentration, or flow rate. To date, no study has comprehensively addressed tight differential pressure control between a compressor and an oxidation reactor in PTA production, where vapor-phase disturbances may cause the required 1.2 kg/cm2 pressure differential to rise as high as 2.8 kg/cm2. Such deviations lead to increased energy consumption, operational costs, and heightened shutdown risks, threatening process safety and stability [12,13,14]. This underscores a critical research gap in pressure differential control under highly dynamic PTA operating conditions.

While cascade control has been reported in related high-pressure systems, such as PVC reactors and general compression networks [10,11], these studies primarily focus on stabilizing local pressures within individual units. They do not explicitly address cross-unit differential-pressure enforcement, where two physically separated units (a compressor and a reactor) must be coordinated through multiple final control elements to satisfy a safety-critical pressure margin. Consequently, the control objective, disturbance characteristics, and architectural requirements in PTA oxidation differ fundamentally from those of conventional cascade applications.

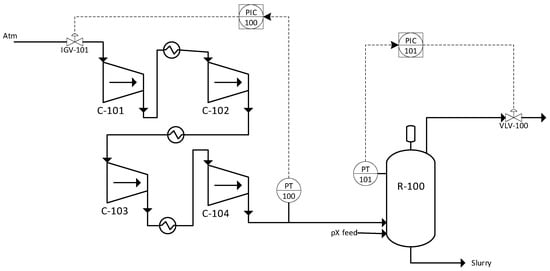

To address this gap, the present study addresses this need by proposing a process-specific cascade control architecture tailored for differential-pressure control in industrial PTA oxidation systems. Rather than introducing a new control theory, this work focuses on the practical design, modeling, and evaluation of a multi-loop cascade configuration that coordinates compressor inlet guide vanes and reactor outlet flow control to enforce a predefined pressure margin under dynamic operating conditions. Three interacting control loops, compressor pressure, reactor pressure, and compressor–reactor differential pressure are systematically modeled using different system identification approaches [15,16] and integrated to enhance disturbance rejection and operational reliability.

2. Methods

This study was conducted using several computational tools and software packages, including Aspen Plus (V12.1) and Aspen Plus Dynamics (V12.1), which are widely used in steady-state and dynamic simulations of chemical processes [1,15]. Microsoft Excel was used for data processing and calculation. The primary process data were obtained directly from a PTA plant in Indonesia. This study focuses on the air compression process in the compressor unit and the paraxylene oxidation reaction in the oxidation reactor unit, with a particular emphasis on evaluating and synchronizing the pressure differential between the two units, which is a key factor in the stability of PTA oxidation [12,13,14]. Table 1, Table 2 and Table 3 summarize the key operational data used to develop the simulation model.

Table 1.

Parameters of the four-stage compressor.

Table 2.

Parameters of the heat exchange (HE) operation.

Table 3.

Sizing and operational conditions of CSTR-101.

A steady-state simulation model was developed and validated to accurately represent the actual field operating conditions, following the standard model validation practices in process control [1]. Using Aspen Plus Dynamics, this validated steady-state model was then extended into a dynamic simulation capable of capturing the time-dependent responses of the process to setpoint (SP) changes, disturbances, and other external factors [15,16]. Two types of dynamic control models were constructed, one employing a conventional proportional–integral (PI) controller and the other implementing a cascade control configuration, consistent with previous comparative studies between PI and cascade schemes [2,3,4,5,6,7,10]. Table 4 summarizes the key process variables and control elements used in both models.

Table 4.

Control process variables between the compressor and reactor units.

After the dynamic model was developed and validated, system identification was performed. Four different identification methods were applied—Smith, Wade, Lilja, and the built-in identification tool in Aspen Plus Dynamics—to generate process reaction curves (PRCs) and corresponding first-order plus dead time (FOPDT) models [15]. The resulting parameters were then used to calculate the root mean square error (RMSE), which served as the basis for comparison. The selection of the representative FOPDT model for each loop was based on a combination of minimum RMSE and physical plausibility of the identified parameters, including the sign of the process gain and non-negative dead time to preserve causality, in line with the identification strategies reported in recent cascade control work [6,7]. Subsequently, controller tuning was conducted using several techniques, including the Lopez, Ziegler–Nichols, and Cohen–Coon methods, all executed within the Aspen Plus Dynamics environment, following established tuning practices [1,2,3,5,6,7].

Following the tuning stage, the performance of the control system was evaluated. The evaluation included SP tracking tests, in which SP changes were introduced to observe the dynamic response, a standard criterion in controller benchmarking [2,5,6,7]. In addition, the disturbance rejection capability was examined under variations in flow rate and compressor rotational speed, reflecting operating disturbances that are realistic for PTA production [11,12]. The resulting control performance was analyzed using the Integral of Absolute Error (IAE), Integral of Squared Error (ISE), and Integral of Time-Weighted Absolute Error (ITAE) criteria to assess the robustness and overall effectiveness of each control strategy [1,6,7,11].

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Model Validation

Table 5 presents a comparison of the steady-state model and the actual operating data from the plant, based on key process parameters. The simulation results show a satisfactory level of agreement with field conditions, consistent with standard engineering practice, in which process models are generally considered acceptable with deviations of up to 5% [1]. The largest observed discrepancy was 4.35% for the pressure in stream 103, whereas the deviations in several other streams were much smaller.

Table 5.

Percentage difference between the steady-state model and actual data.

The simulated p-xylene conversion in the oxidation reactor was 66%, which closely aligns with the range reported by Tomás et al., who stated that Co/Mn/Br-catalyzed oxidation achieves p-xylene conversions between 32% and 72% depending on the temperature, pressure, and aldehyde concentration [13]. These results confirm that the oxidation reactor model is chemically reasonable and consistent with the literature data on PTA precursors [12,13,14].

The dynamic model was based directly on the established steady-state process design, resulting in a fully consistent representation of the selected key parameters with no observable deviation. The cascade control system was configured following the PI controller structure currently applied in industrial operations. Its implementation is intended to enhance and optimize overall control performance within the PTA production process, aligning with improvement strategies commonly reported across various process industries [2,3,4,5,6,7,10,11].

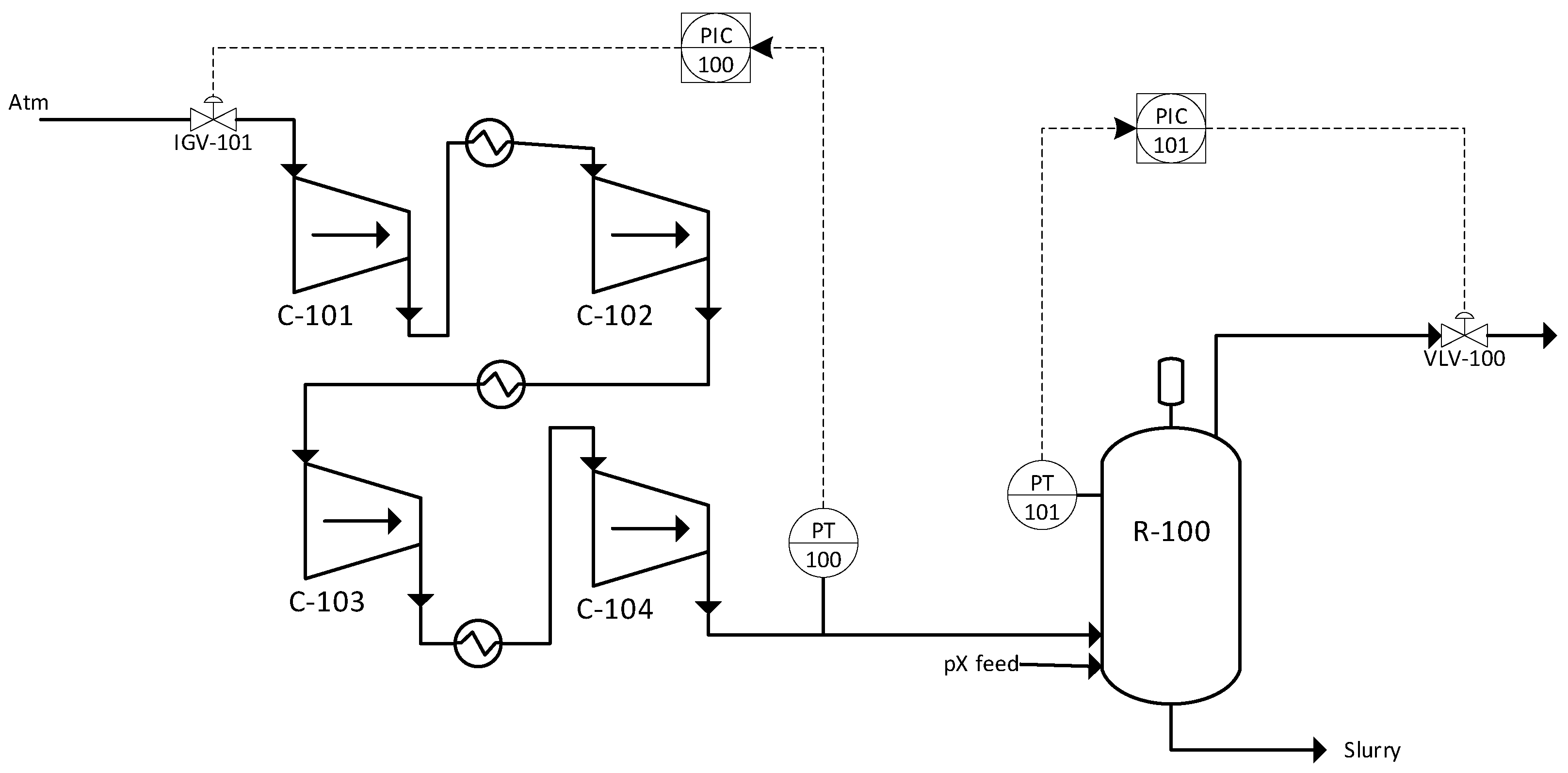

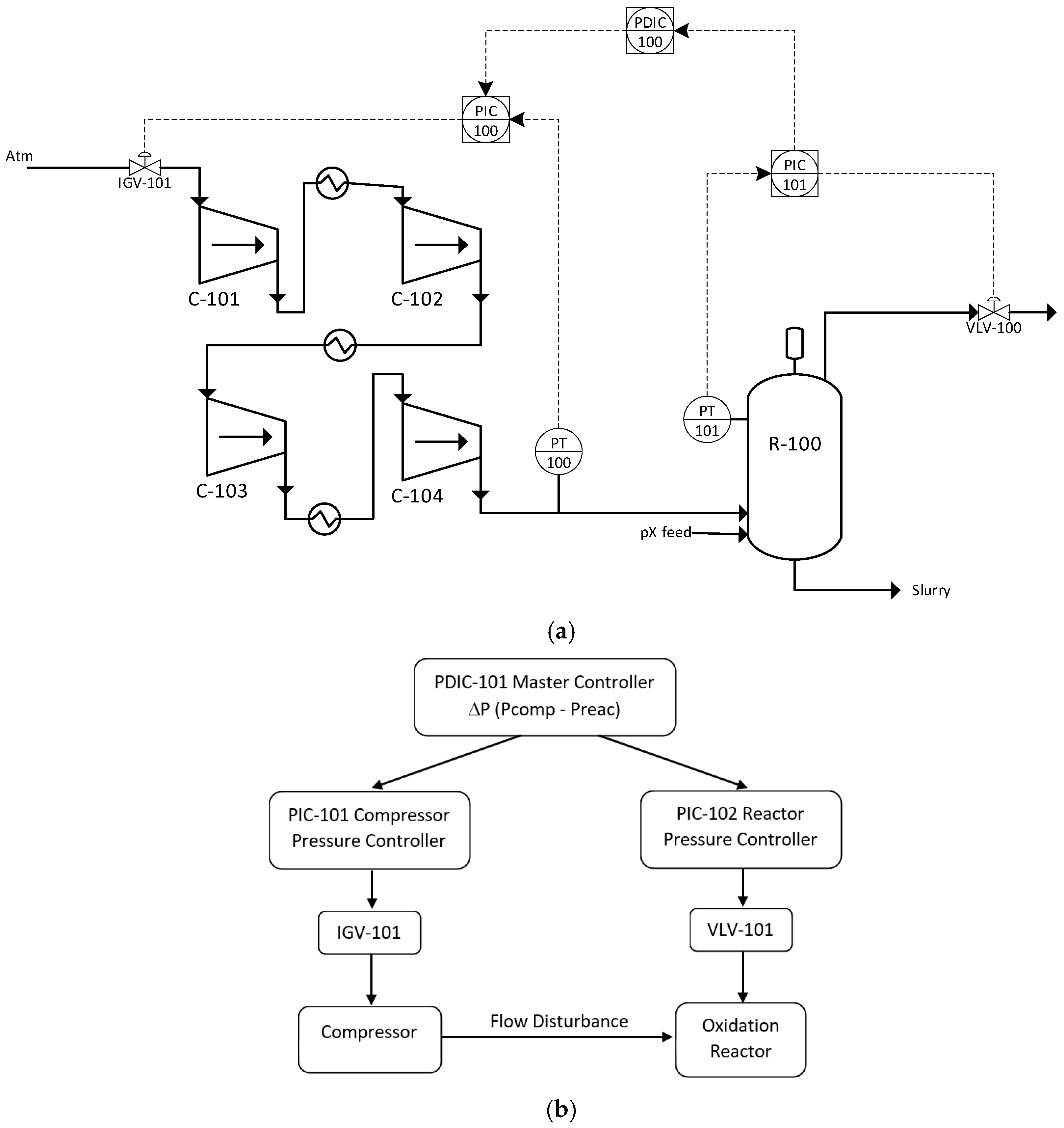

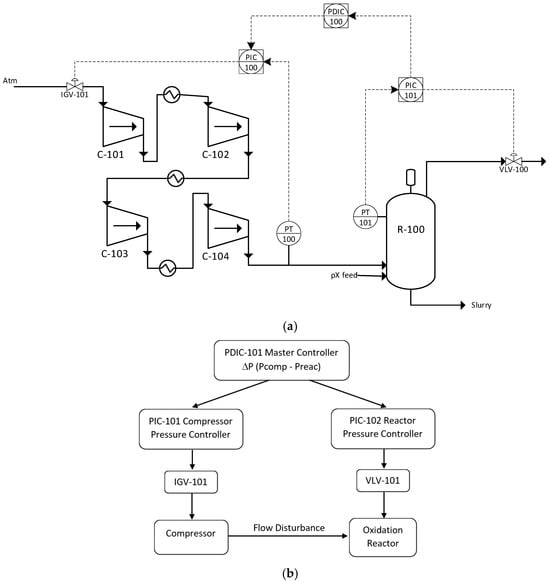

In this configuration, IGV-101 is installed at the inlet of the first compressor (C-101), while VLV-101 is positioned at the steam outlet of the oxidation reactor (R-101). These two final control elements serve to maintain differential pressure stability under various disturbances, analogous to pressure management roles in the compression systems and reactor units described in [10,11]. Figure 1 shows the dynamic models for both the PI controller and the cascade control system. Figure 2 illustrates the control structure using the cascade configuration.

Figure 1.

Dynamic simulation using PI controller.

Figure 2.

Dynamic simulation using cascade controller. (a) Cascade Control Architecture; (b) Cascade Control Disturbance Propagation.

3.2. System Identification

System identification was conducted using the PRC method to characterize the dynamic response of the system to a step change [15]. This identification process was designed to obtain the most accurate FOPDT model based on the lowest RMSE value. For this study, we employed four identification methods, Smith, Lilja, Wade, and the Aspen Plus built-in identification tool, which had previously been applied in similar contexts for delay-dominant and cascaded systems [6,7].

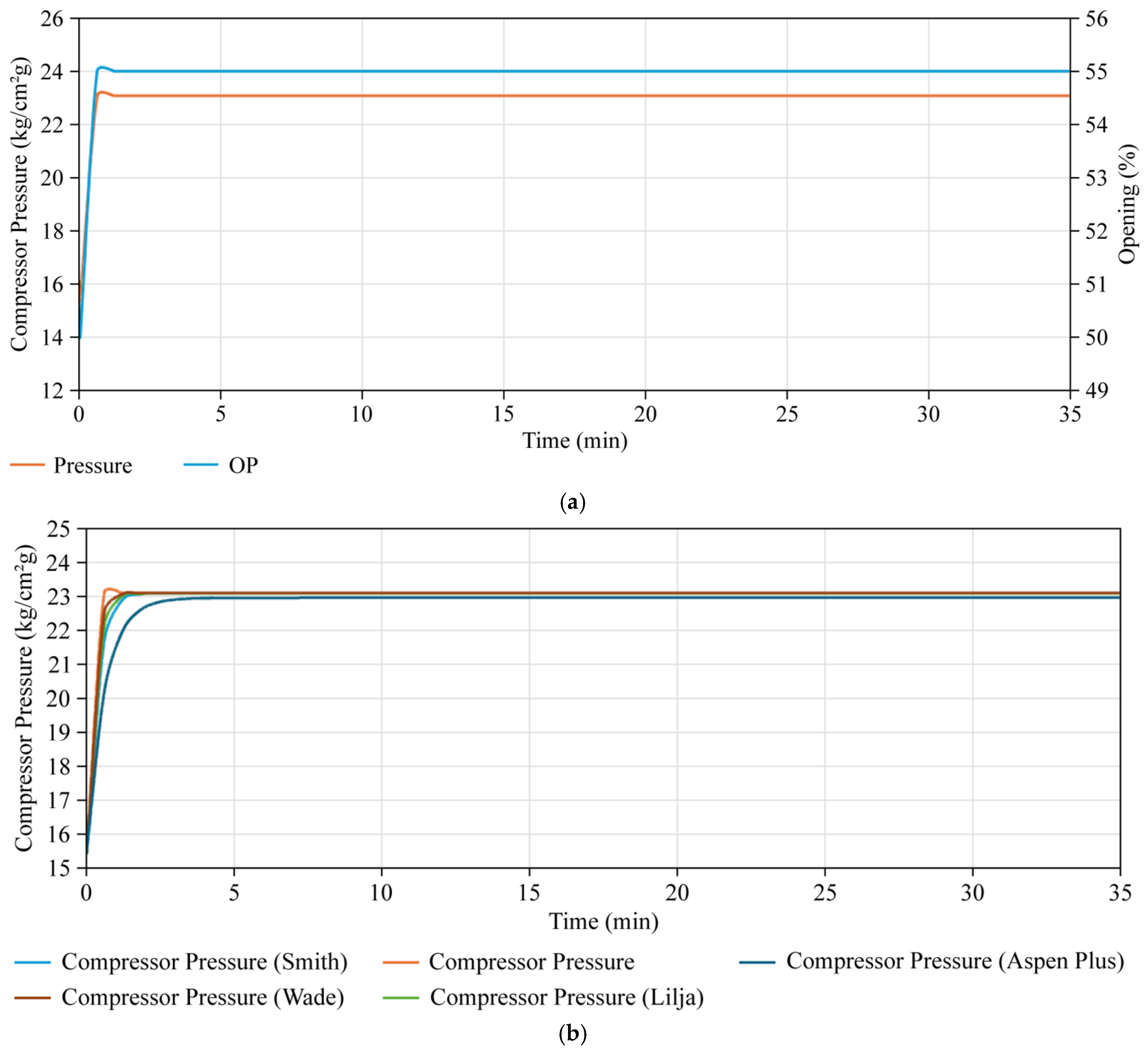

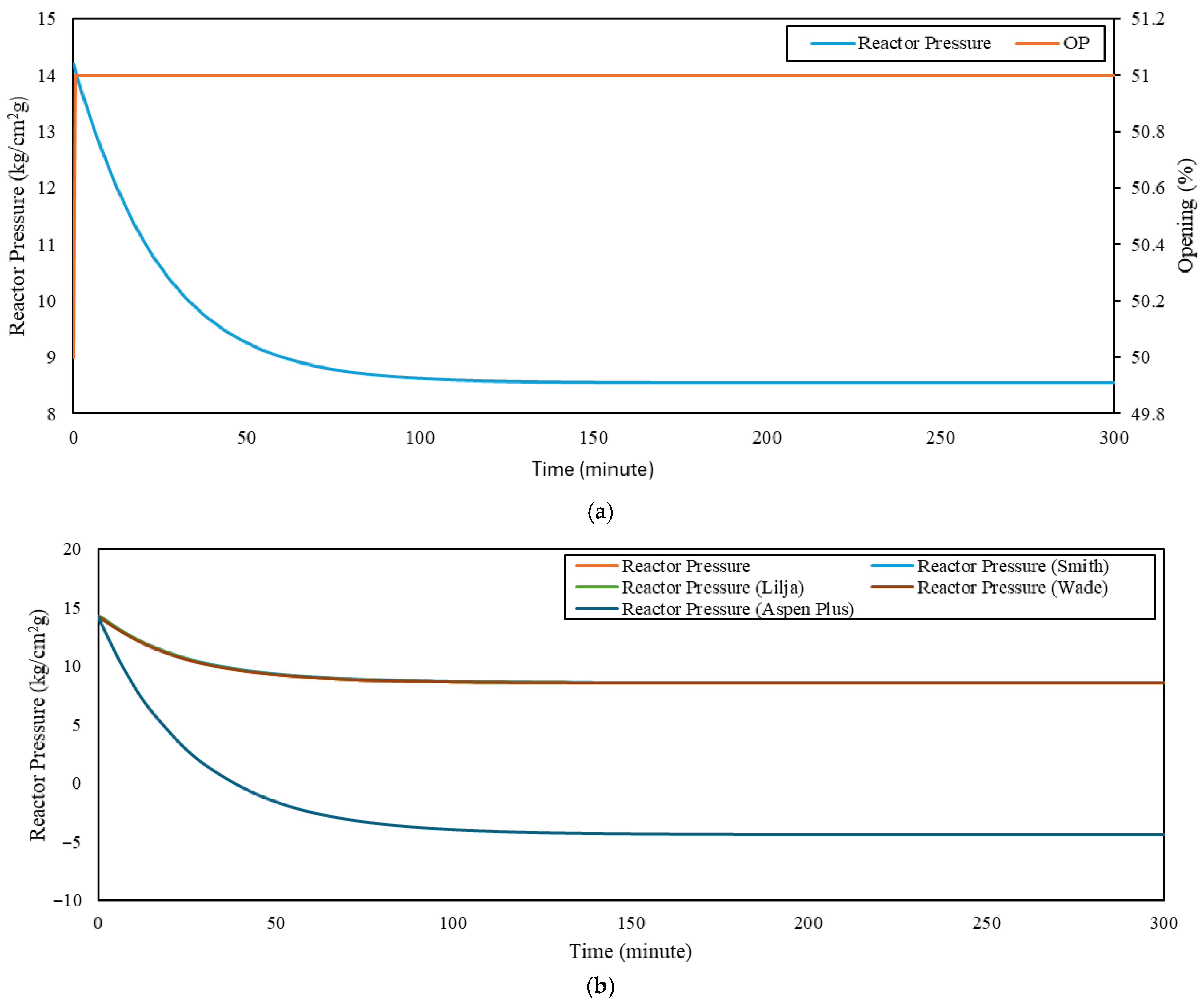

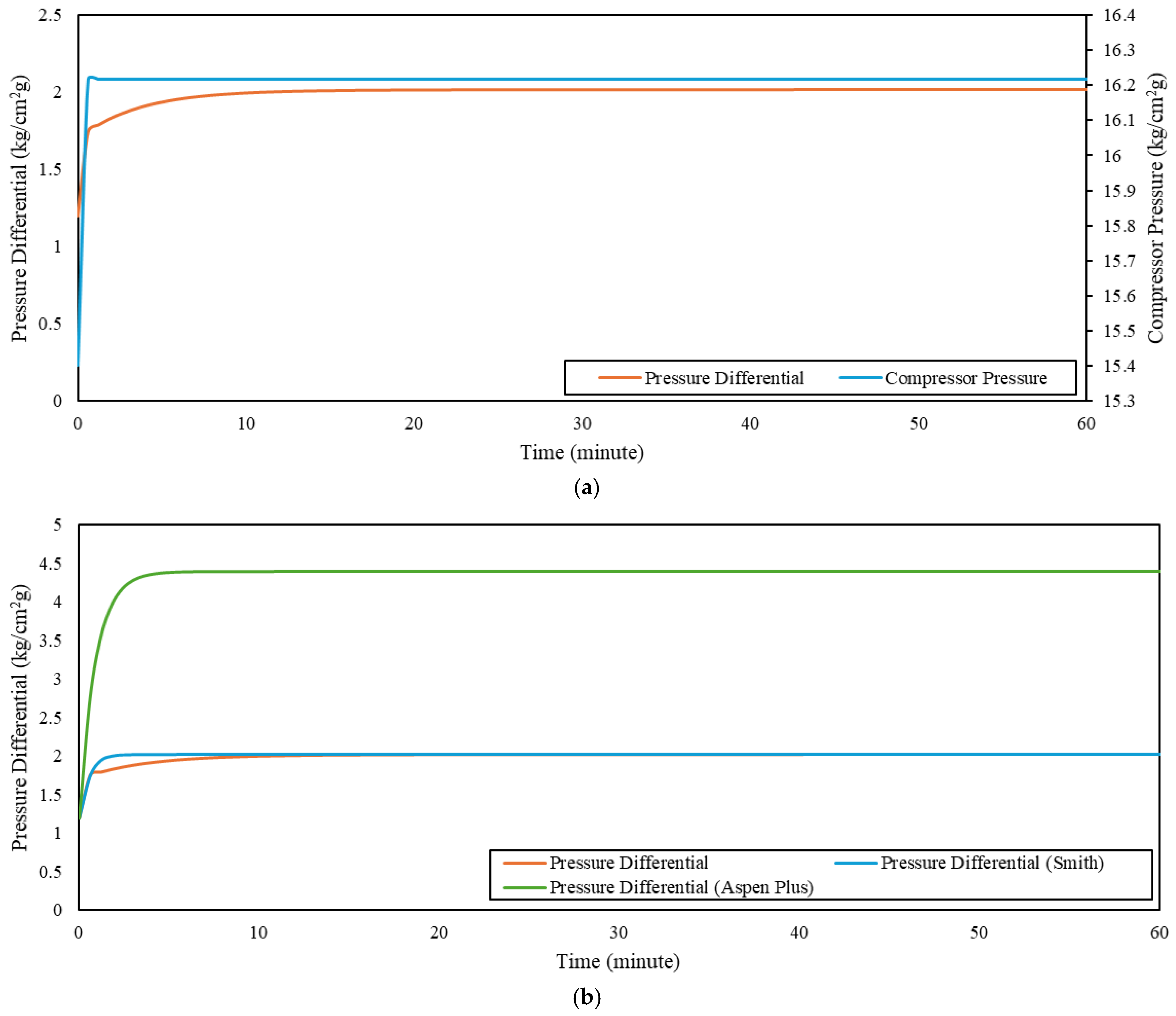

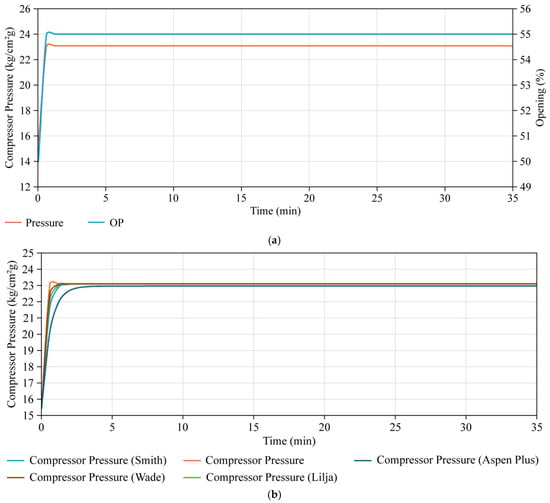

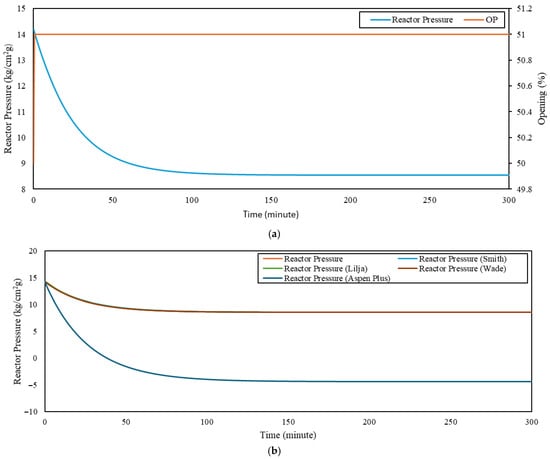

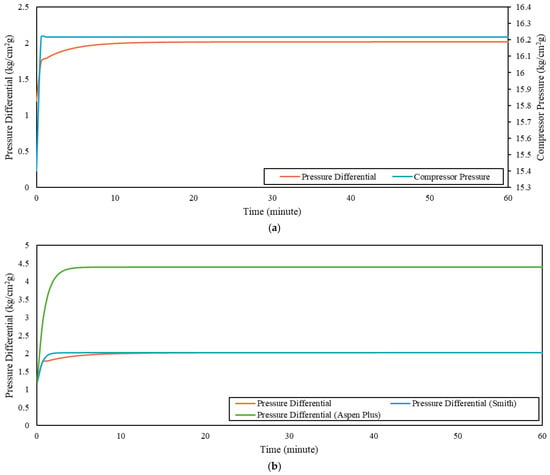

Figure 3 and Table 6 present the PRC profiles and corresponding FOPDT model results for the compressor. Similarly, Figure 4 and Table 7 show the PRC profiles and FOPDT results for the oxidation reactor. The PRC profiles and the resulting FOPDT models for the cascade system are presented in Figure 5 and Table 8. The initial operating point corresponding to nominal plant conditions, step amplitude (±3–5% of the nominal manipulated variable), sampling time (1 s), data window length covering at least 5τ of the dominant dynamics, and identification under open-loop conditions.

Figure 3.

(a) Compressor PRC; (b) RMSE of the compressor graph.

Table 6.

Compressor FOPDT results.

Figure 4.

(a) Reactor PRC; (b) RMSE of the reactor graph.

Table 7.

Reactor FOPDT results.

Figure 5.

(a) Cascade PRC; (b) RMSE of the cascade graph.

Table 8.

Cascade FOPDT results.

To ensure reproducibility, the PRC/FOPDT models were identified on a per-loop basis using explicit nominal operating points representative of normal plant operation. For the compressor pressure control loop, identification was conducted at a nominal compressor discharge pressure of 15.4 kg/cm2 g, with the step input injected at the manipulated variable associated with compressor pressure regulation using a ±5% change. For the oxidation reactor pressure control loop, the nominal operating point corresponded to a reactor pressure of 14.2 kg/cm2 g, and step changes of ±3% were applied to the reactor pressure control valve opening. For the differential pressure control loop, the nominal operating point was defined by a steady-state pressure difference of 1.2 kg/cm2 g, with the step input applied to the corresponding manipulated variable using a ±3% change.

The negative process gain identified for the reactor pressure loop is physically consistent with the control mechanism employed. An increase in the reactor outlet vapor flow rate reduces the reactor internal pressure, resulting in an inverse input–output relationship. Such behavior is characteristic of pressure regulation via outlet throttling and does not indicate a modeling anomaly. It should be noted that the identified FOPDT models are intended for control-oriented analysis and comparative performance evaluation between PI and cascade configurations. Full-scale dynamic validation using plant step-test data was not feasible due to operational constraints and is considered as future work.

The system identification results presented in the graphs and tables show the lowest RMSE values for each unit. The smallest RMSE for the FOPDT model was obtained using the Wade method, whereas the most accurate FOPDT model for the oxidation reactor was achieved using the Lilja method. Although the Lilja and Wade methods produced comparable process gains for the cascade loop, both resulted in negative dead-time estimates, which are physically non-causal and therefore inadmissible for control design. These models were explicitly rejected on physical grounds. Among the remaining physically admissible models, the Smith method yielded the lowest RMSE and was selected as the representative cascade model. This selection strategy, which combines statistical accuracy with physical interpretability, is consistent with established control-oriented modeling practices for industrial process control applications [6,7,15].

Equation (1) (IAE) quantifies the cumulative deviation of pressure from its setpoint and reflects overall control accuracy. Equation (2) (ISE) penalizes large pressure deviations and is particularly relevant for evaluating safety-critical pressure excursions. Equation (3) (ITAE) assigns higher weight to long-lasting deviations, making it suitable for assessing how quickly the system recovers after disturbances in the oxidation reactor.

The pressure control strategy implemented in this study consists of both single-loop PI control and cascade control architectures. The PI controller is described Equation (4).

where u(t) is the manipulated variable, e(t) is the control error, is the controller gain, and is the integral time.

In the cascade configuration, the outer (master) controller regulates the pressure differential between the compressor outlet and reactor inlet, while the inner (slave) controllers regulate compressor discharge pressure and reactor pressure, respectively. The master controller generates the setpoint for the slave controller, enabling early disturbance detection and improved rejection.

The dynamic behavior of the pressure system is approximated using a first-order plus dead-time (FOPDT) model Equation (5).

where is the process gain, τ is the time constant, and θ represents the dead time. These parameters were identified using Smith, Wade, and Lilja methods, and selected based on minimum RMSE.

The PI and cascade controller tuning parameters were calculated using five tuning methods. Each method yielded values for the controller gain (), integral time (), and dead time (). Table 9, Table 10 and Table 11 summarize the tuning results for each controller. The use of multiple tuning methods is consistent with previous studies comparing Ziegler–Nichols, Cohen–Coon, and Lopez-based tuning in PI and cascade controllers [2,5,6,7].

Table 9.

Tuning PIC-101.

Table 10.

Tuning PIC-102.

Table 11.

Tuning PDIC-101.

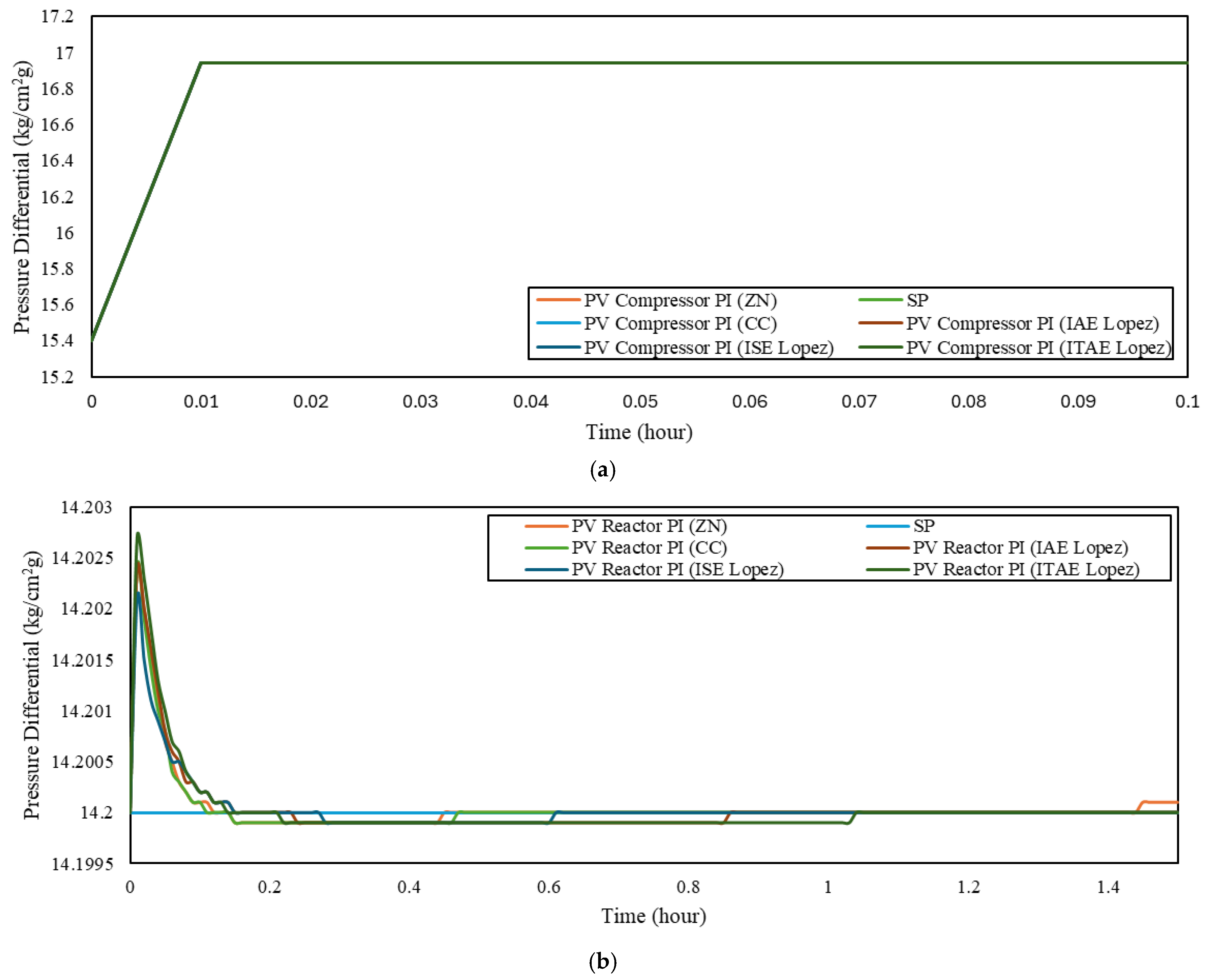

3.3. SP Tracking Testing

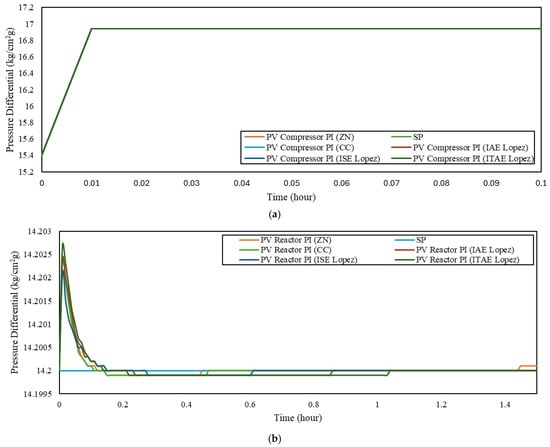

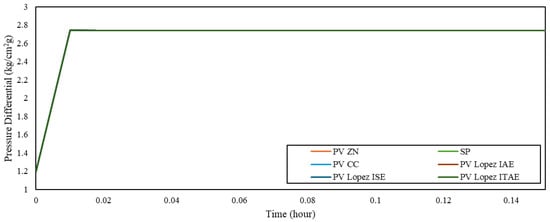

Figure 6 and Table 12 show the SP tracking results for the PI controller, and Figure 7 and Table 13 present those for the cascade control system. SP tracking was performed as a controller performance evaluation method that involves changing the initial setpoint (SP1) to a new desired setpoint (SP2), which is a common criterion in controller assessment [2,6,7]. For the PI controller at the compressor inlet, the SP was adjusted to 16.94 kg/cm2 g, while for the cascade control system, the SP change was applied to the differential pressure at 2.64 kg/cm2 g.

Figure 6.

SP tracking response of the PI controller: (a) compressor; (b) reactor.

Table 12.

Total SP tracking error of the PI controller.

Figure 7.

SP tracking response of cascade control system.

Table 13.

Total SP tracking error of cascade control system.

By comparing performances between the PI and cascade configurations, we can infer that the cascade control system achieved the best SP tracking performance using the Ziegler–Nichols tuning method. This result is consistent with previous comparative studies showing the superior response of cascade control to SP changes in various unit operations [2,5,6,7,10].

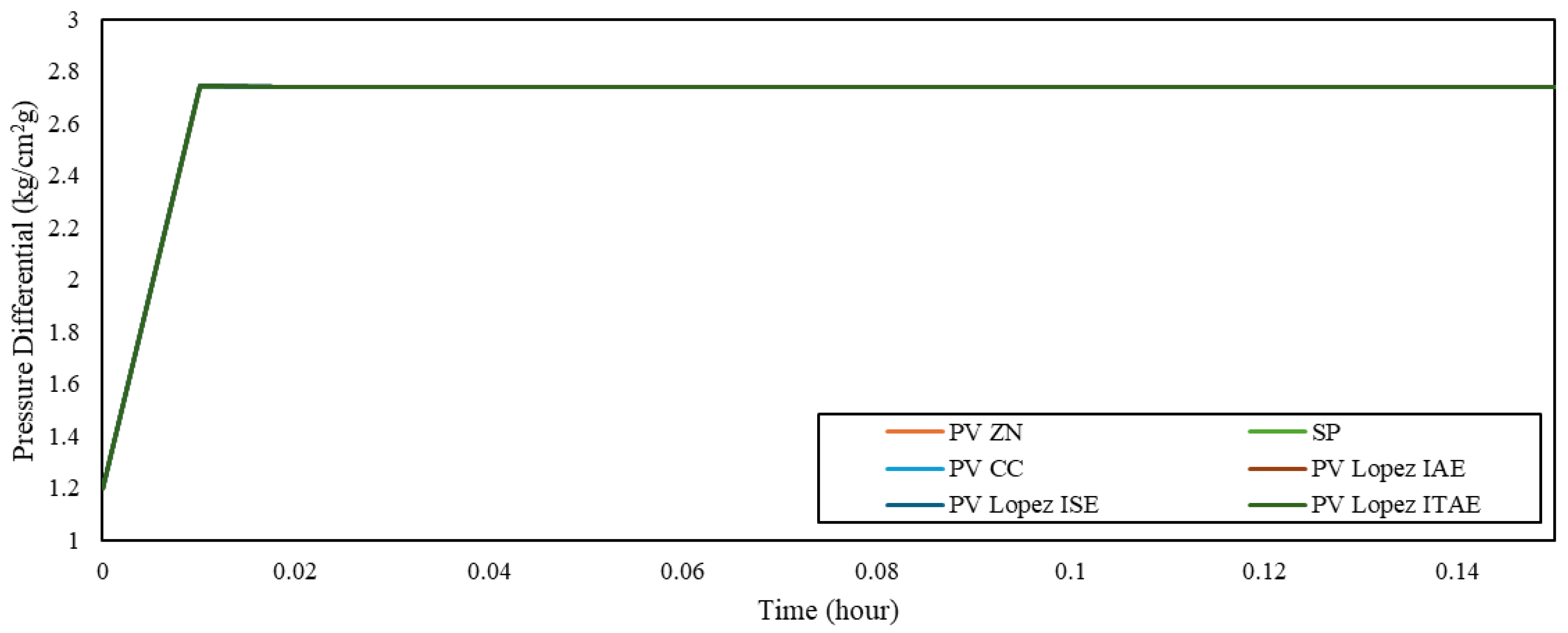

3.4. Disturbance Rejection Testing

Disturbance rejection tests were conducted to evaluate the ability of each controller to maintain the predetermined SP in the presence of external disturbances. In this study, disturbances were introduced by reducing the flow rate by 16% and decreasing the compressor rotational speed by 0.003% (RPM I) and 0.01% (RPM II). These disturbance scenarios represent realistic operating fluctuations in compressor–reactor systems [11,12].

The small compressor speed disturbances (0.003% and 0.01% RPM) were intentionally introduced to represent normal operational fluctuations rather than major process upsets. Under such conditions, the cascade controller maintained the differential-pressure setpoint within the numerical resolution of the simulation, resulting in near-zero integral error values. These results should be interpreted as effective attenuation of small disturbances rather than perfect physical rejection.

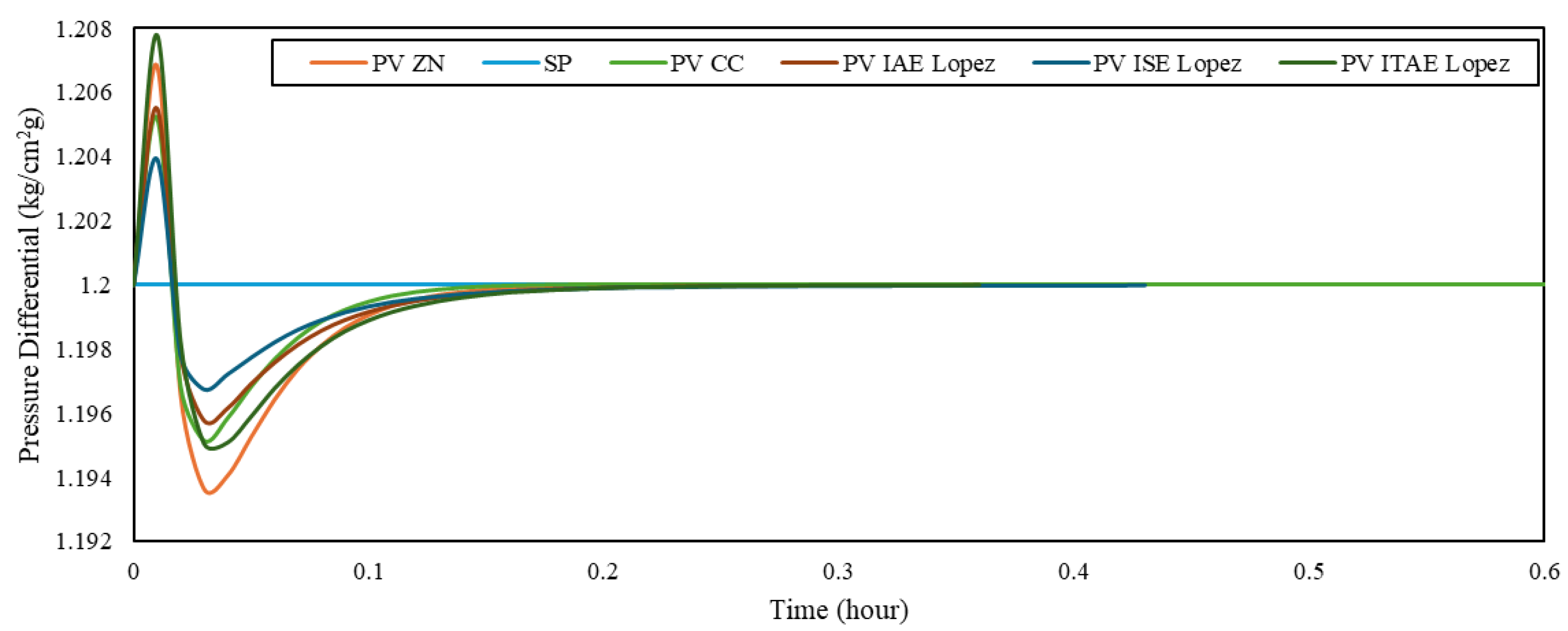

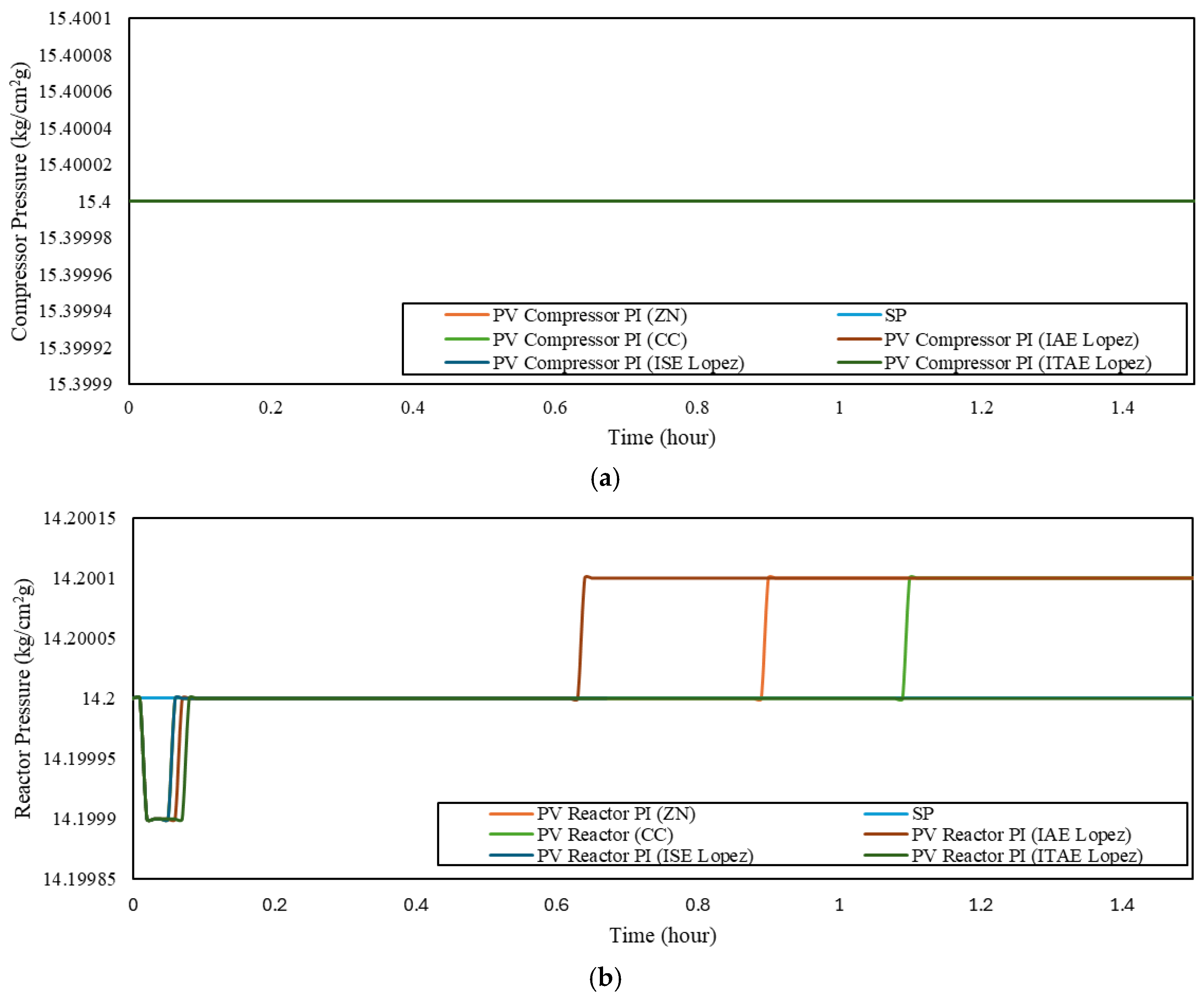

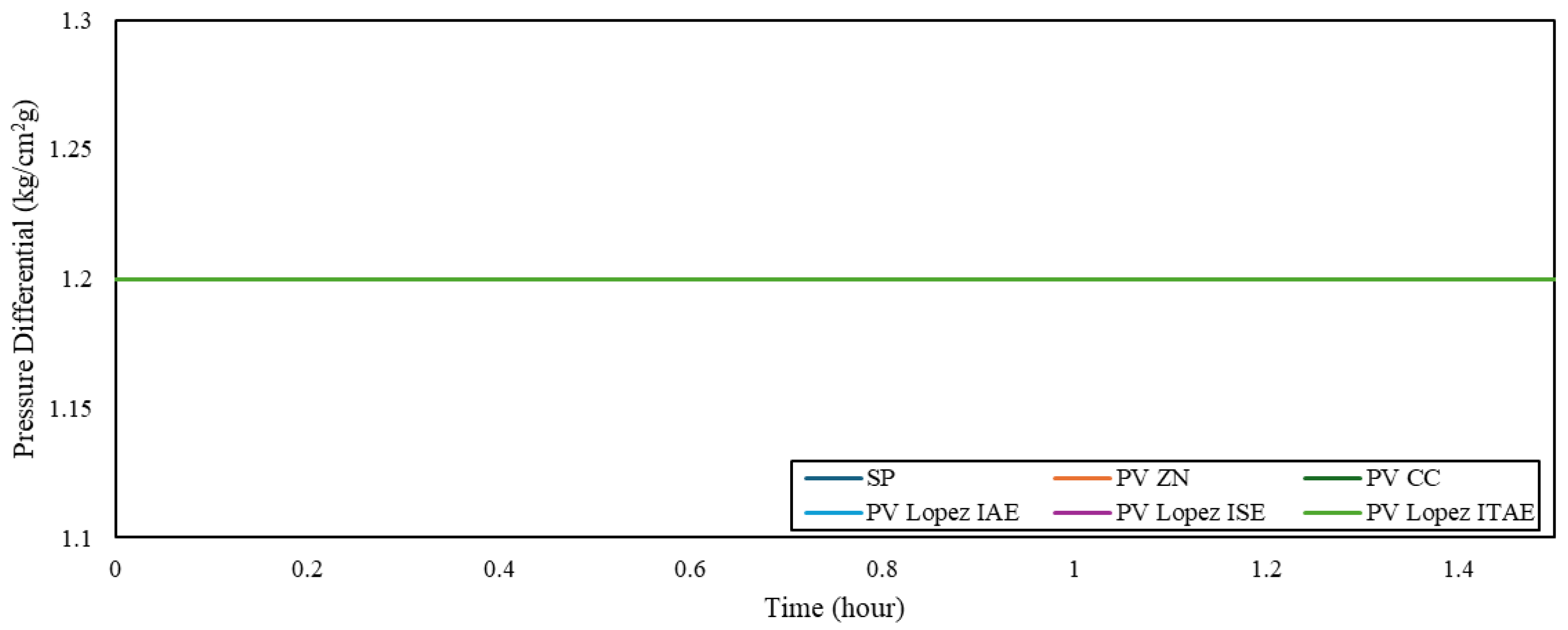

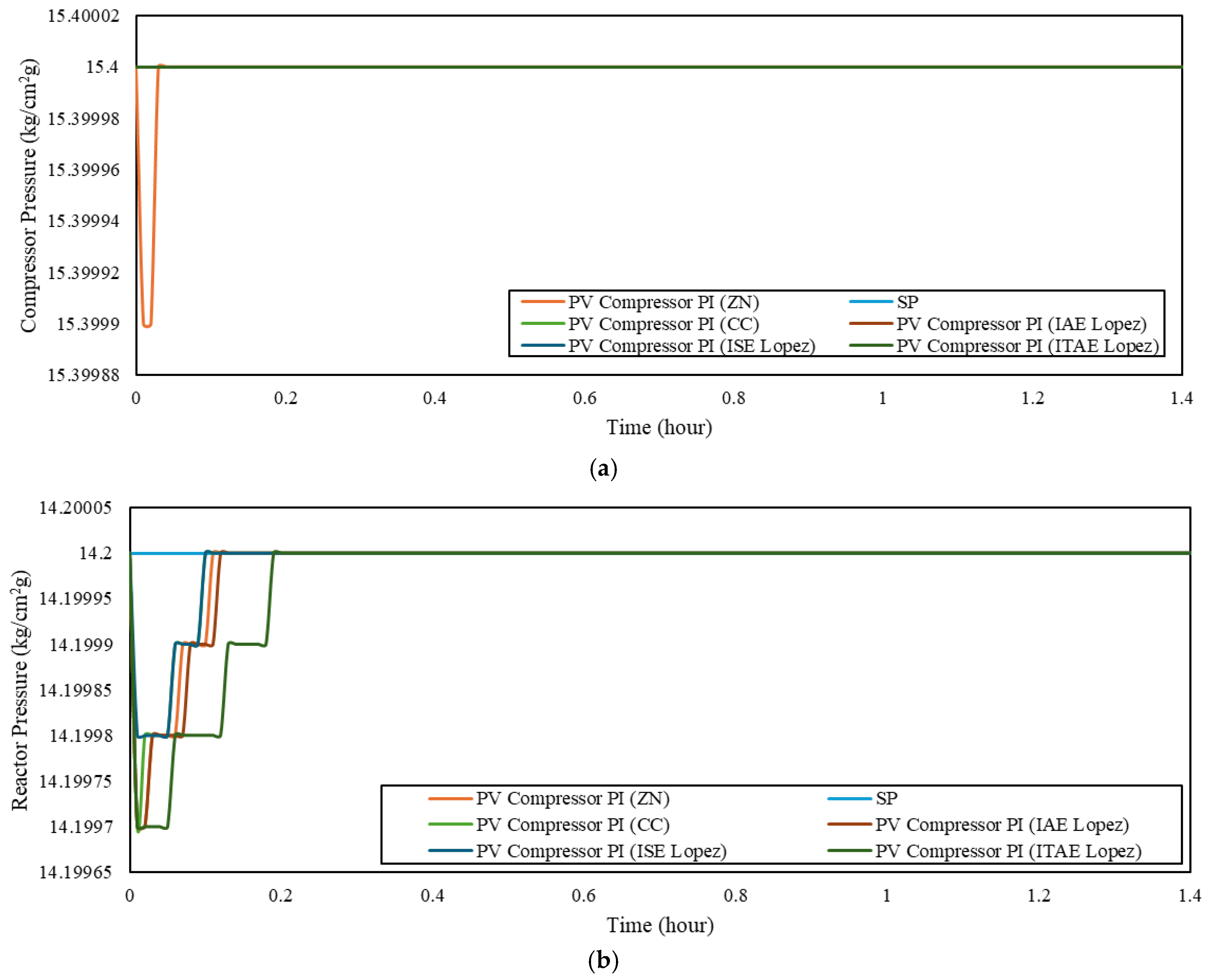

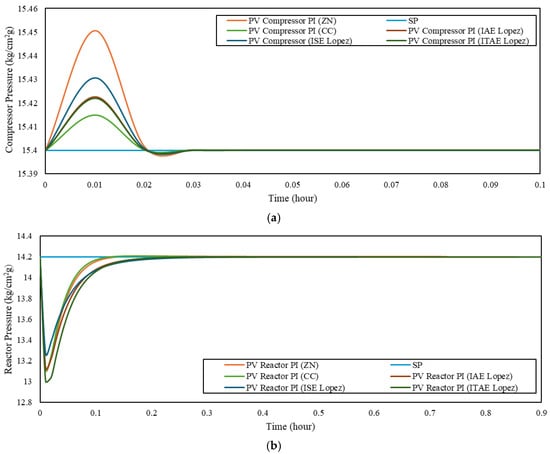

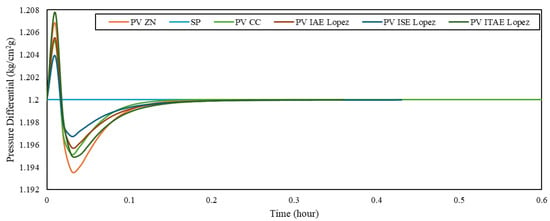

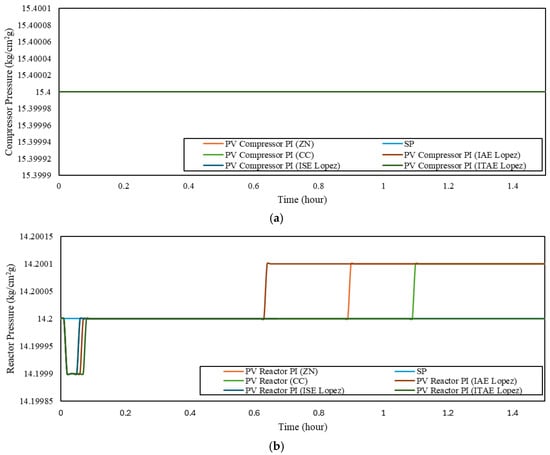

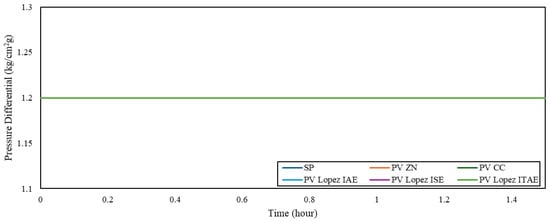

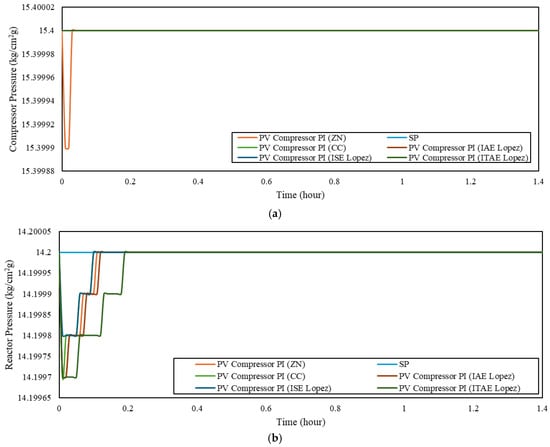

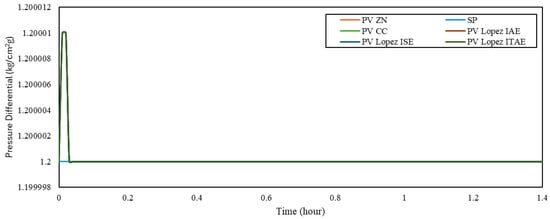

Figure 8 and Table 14 show the disturbance rejection performance of the PI controller under flow rate variation, while the cascade controller’s response to the same disturbance is presented in Figure 9 and Table 15. Figure 10 and Table 16 show the PI controller’s response to RPM I variation, and Figure 11 and Table 17 present the corresponding cascade control performance. The PI controller results for RPM II variation are shown in Figure 12 and Table 18, while the cascade control results are presented in Figure 13 and Table 19.

Figure 8.

PI controller disturbance rejection for (a) compressor flow rate change; (b) reactor flow rate change.

Table 14.

Total error of disturbance rejection with PI controller for flow rate changes.

Figure 9.

Cascade control disturbance rejection for flow rate changes.

Table 15.

Total error of disturbance rejection with cascade control for flow rate changes.

Figure 10.

PI controller disturbance rejection for RPM I variations: (a) compressor; (b) reactor.

Table 16.

Total error of disturbance rejection with PI controller for RPM I variations.

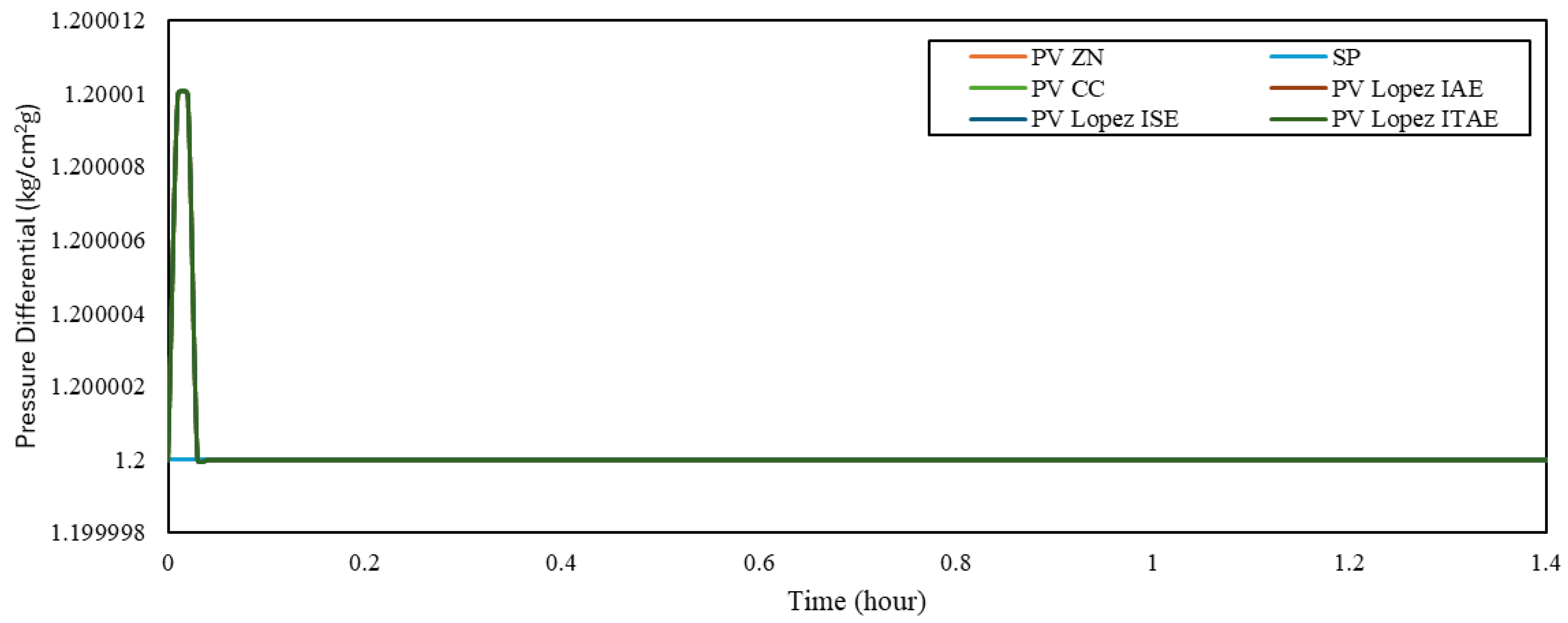

Figure 11.

Cascade control disturbance rejection for RPM I variations.

Table 17.

Total error of disturbance rejection with cascade control for RPM I variations.

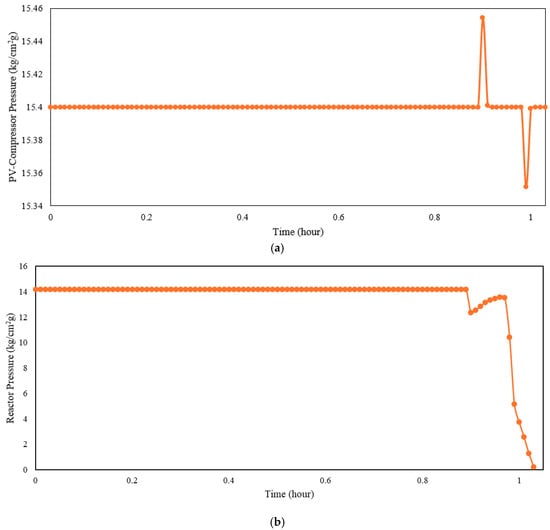

Figure 12.

PI controller disturbance rejection for RPM II variations: (a) compressor; (b) reactor.

Table 18.

Total error of disturbance rejection with PI controller for RPM II variations.

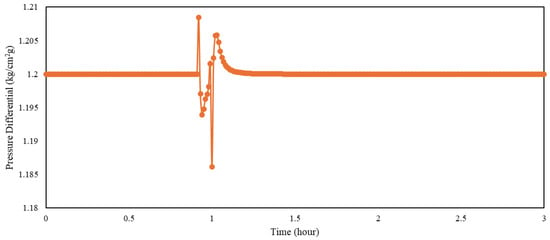

Figure 13.

Cascade control disturbance rejection for RPM II variations.

Table 19.

Total error of disturbance rejection with cascade control for RPM II variations.

Overall, the disturbance rejection tests indicate that the cascade control system consistently yields lower error values than the conventional PI controller. The Lopez ISE tuning method delivers the best performance among all cascade configurations, producing the smallest errors in response to all applied disturbances. This finding agrees with the recent literature highlighting the effectiveness of Lopez-based tuning in enhancing integral error performance in cascade systems [6,7].

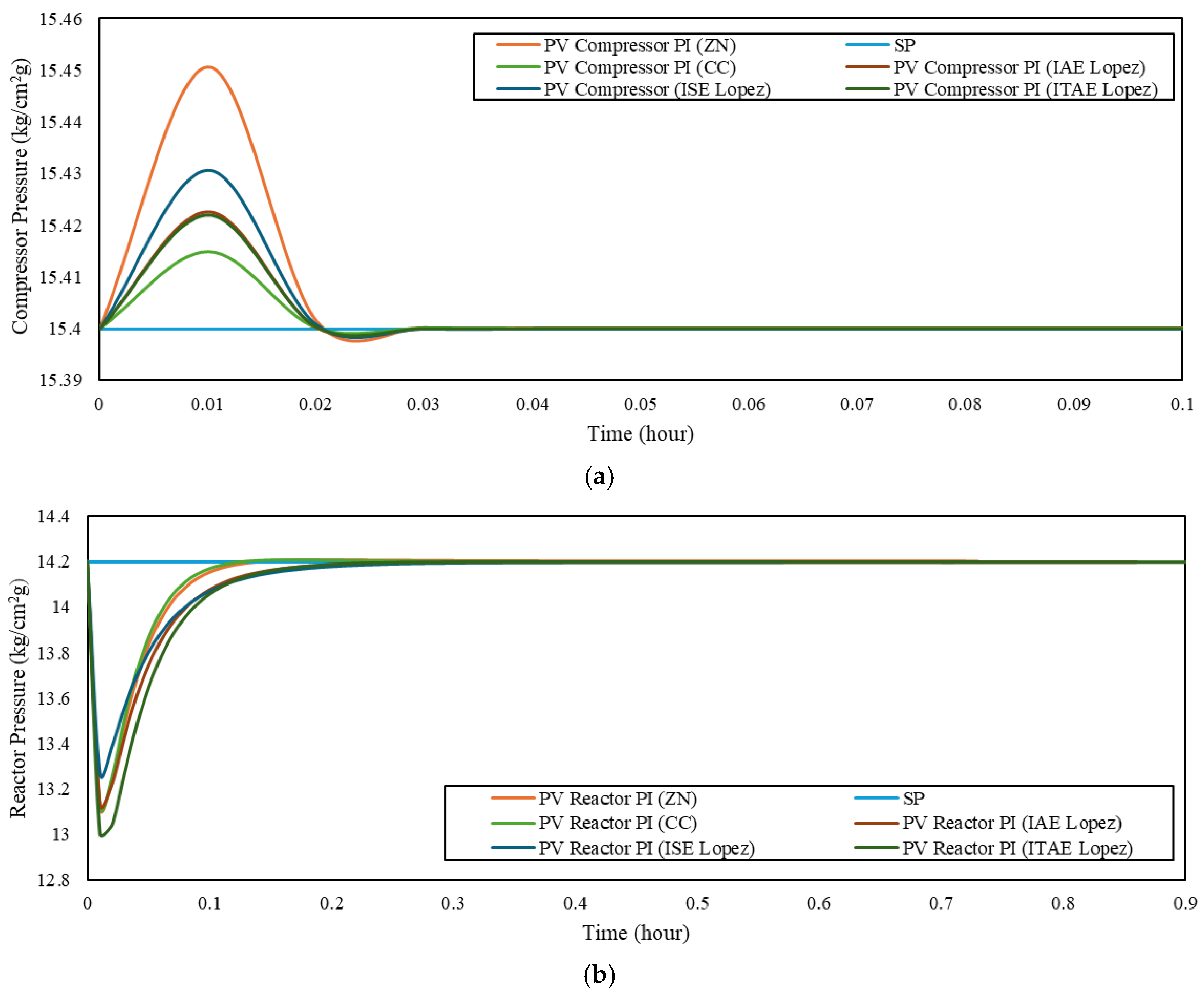

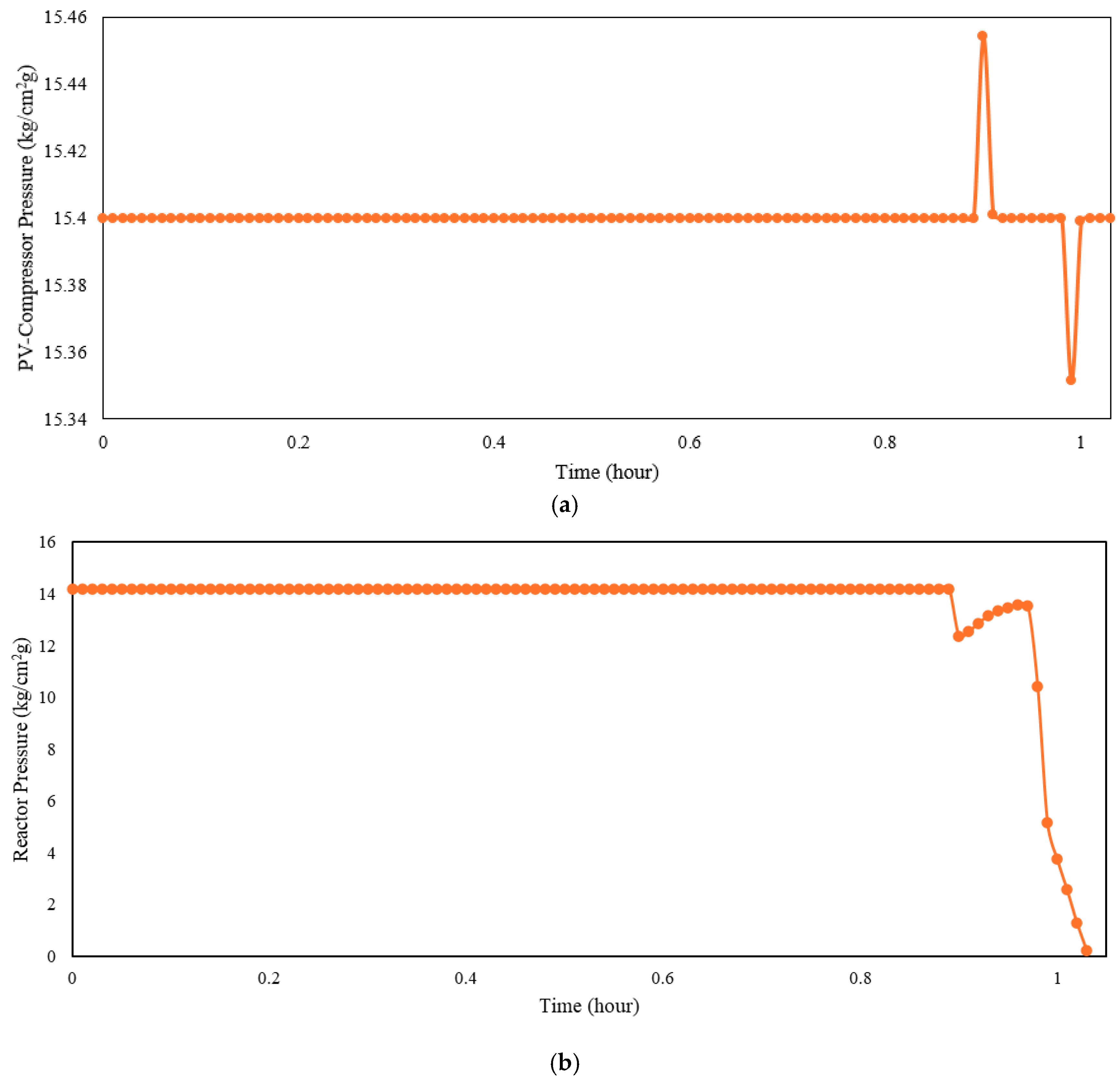

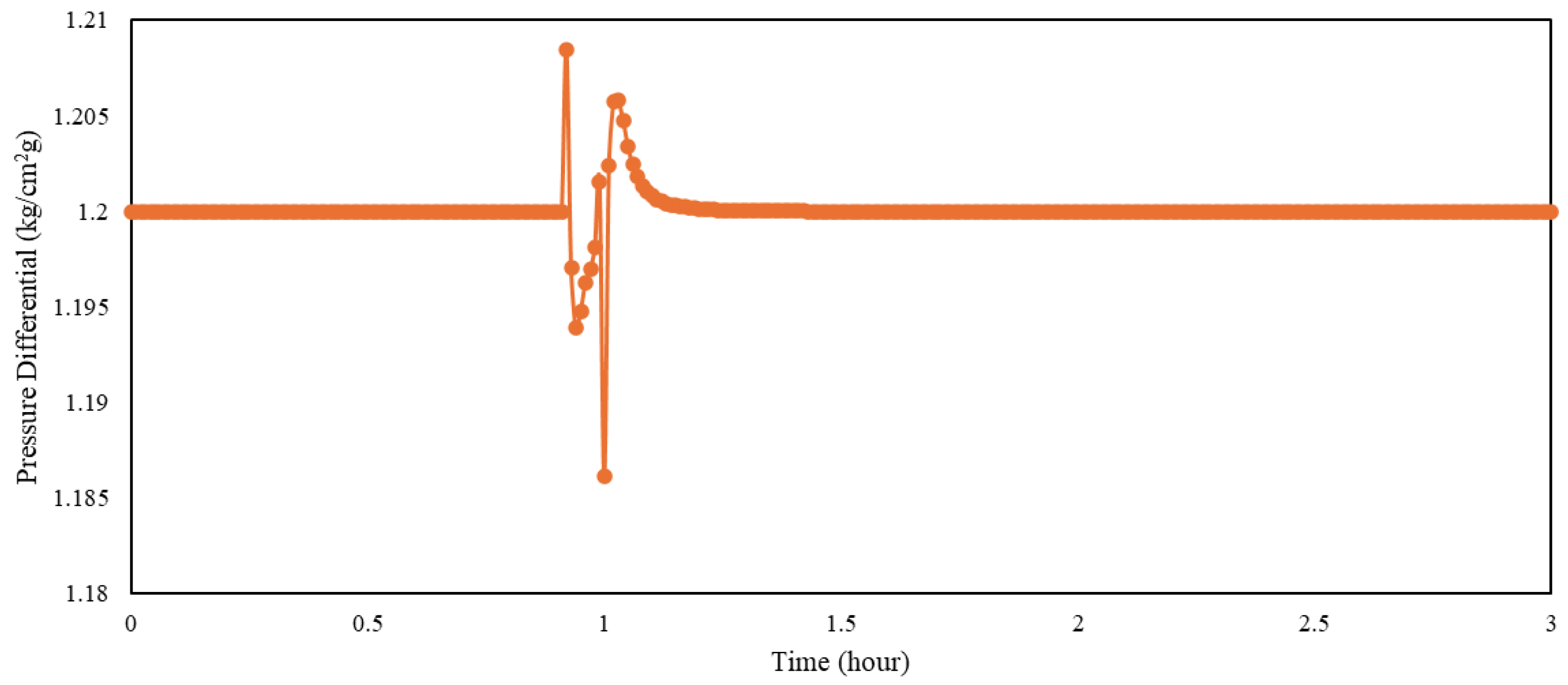

3.5. Extreme Disturbance Rejection Testing

An additional test was performed using an extreme flow rate disturbance to further evaluate the robustness of both the PI controller and the cascade control system. The initial flow rate of 166,000 kg/h was reduced by 30%, and both controllers were assessed based on their ability to maintain process stability and prevent system shutdown. These extreme test conditions are similar to stress scenarios used in high-risk reactor and PVC process control studies [10,12,14]. More importantly, under the extreme 30% flowrate reduction scenario, the cascade control system maintained operational continuity, whereas the PI-controlled system experienced instability leading to shut-down. In the PI-controlled case, the extreme 30% inlet flowrate reduction is introduced as a single-step disturbance at t = 0.97 h. Following this event, the reactor pressure decreases from 13.5293 kg/cm2 g, drops to 10.3996 kg/cm2 g shortly after the disturbance, and continues to decline until reaching 0 kg/cm2 g at t = 1.03 h, which marks the shutdown condition. This result provides a physically meaningful and practically relevant validation of the cascade architecture under severe operating conditions.

Figure 14 and Figure 15 show the performance of the PI controller and cascade control under this severe disturbance, respectively. These figures illustrate the disturbance handling capabilities of the controllers. The results indicate that the cascade control system successfully maintained process continuity, whereas the process failed to remain operational with the PI controller. This behavior confirms the superior robustness of the cascade architectures in managing severe process upsets, as reported in compressor and thermal-network control studies [7,8,9,10,11].

Figure 14.

PI controller disturbance rejection for extreme flow rate changes: (a) compressor; (b) reactor.

Figure 15.

Cascade control disturbance rejection for extreme flow rate changes.

3.6. Discussion

The steady-state model was developed using Aspen Plus (V12.1) due to its extensive chemical component database and superior capability in simulating chemical processes compared with other software [1,15]. The model was constructed based on available design data, and its simulation results were compared with actual plant data to ensure accuracy. The comparison showed excellent agreement, with all discrepancies falling within the acceptable threshold of 5%. The simulated p-xylene conversion in the oxidation reactor was 66%, which is in line with the range reported by Tomás et al. for Co/Mn/Br-catalyzed oxidation [13]. The largest deviation in the simulation occurred in stream 103, with a pressure difference of 4.35%, whereas the smallest deviation was found in stream 114, at only 0.06%.

In the context of industrial PTA oxidation units, model validation against plant data is typically evaluated using moderate tolerance bands ≤5%, which account for instrument uncertainty, process noise, and unmeasured disturbances inherent in field data. The most critical variables for safe operation and product quality in this study are the compressor discharge pressure, oxidation reactor pressure, and compressor–reactor differential pressure, as these directly relate to mechanical integrity, process stability, and reactor performance. While a ≤5% deviation is adopted as a general validation criterion for dynamic modeling accuracy, stricter internal operating limits are applied in practice for safety-critical pressure constraints, ensuring that the validated model remains conservative with respect to plant safety and operational reliability. This approach aligns with standard industrial modeling and validation practices for complex, disturbance-driven processes.

Following the successful development of the steady-state model, a dynamic model was constructed in Aspen Plus Dynamics, enabling a seamless transition from steady-state to dynamic simulation [15,16]. The dynamic model was validated by comparing it with the steady-state model, and the results confirmed full consistency, with no observed deviation (0%) in the selected parameters. This demonstrates the capability of the dynamic model to accurately capture the process behavior under time-dependent conditions.

Both PI and cascade control systems were evaluated using their respective FOPDT models, with the smallest RMSE value pointing to the optimal model for each controller [6,7,15]. Controller performance was assessed using standard criteria, including IAE, ISE, and ITAE [1,6,7,11]. The SP tracking tests demonstrated that the cascade control system outperformed the conventional PI controller. Disturbance rejection tests further confirmed the superiority of the cascade configuration, with an order-of-magnitude reduction in integral error indices compared with the conventional PI controller, consistent with advantages reported for multi-loop cascade strategies in other chemical systems [2,3,4,5,6,7,10,11].

In addition to disturbance rejection, an extreme flow rate test was conducted using an eight-step reduction pattern. The cascade control system successfully maintained process stability under this severe condition, whereas the PI controller was unable to prevent system shutdown. This performance difference arises from the single-loop nature of the PI controller, which responds only to local pressure deviations, whereas the cascade control system handles disturbances through a coordinated multi-variable approach. The master controller in the cascade structure detects the disturbance early and promptly communicates corrective action to the slave controller, enabling rapid stabilization. In contrast, the PI controller operates independently, without the integration of feedback from other process variables, resulting in delayed and insufficient corrective action. This behavior is consistent with observations on the control of compression systems, PVC reactors, and district cooling networks [8,9,10,11].

Severe reductions in air flow can destabilize the oxidation reaction by disrupting optimal operating conditions and accelerating thermodynamic imbalances within the reactor [12,13,14]. When the air flow significantly decreases and the control system cannot maintain operational stability, shutdown becomes unavoidable. This behavior was observed under PI control, which responded to the pressure imbalance sluggishly. In contrast, the cascade control system reacted more rapidly to pressure deviations between the compressor and reactor, enabling the system to remain stable despite some fluctuations and thereby enhancing operational reliability.

Recent studies have demonstrated the potential of advanced control approaches, such as filtered disturbance rejection control and neuroadaptive reinforcement learning, in addressing nonlinear and highly disturbed systems. While these methods offer superior adaptability, they often require extensive training data, high computational effort, and significant modifications to existing control infrastructure. In contrast, the proposed cascade strategy offers a transparent, low-complexity, and distributed control system (DCS)-compatible solution that can be readily implemented in existing PTA plants, making it particularly attractive for industrial retrofit applications. These results demonstrate that a properly designed, process-specific cascade architecture can substantially enhance disturbance rejection and operational robustness compared with conventional single-loop PI control in PTA oxidation systems.

4. Conclusions

In this study, steady-state and dynamic models for the PTA oxidation–compressor system were developed and validated, achieving deviations below 5% against plant data and 0% mismatch between steady-state and dynamic simulations. Based on the minimum RMSE, system identification using four methods identified the most representative FOPDT models for each control loop—Wade for PIC-101, Lilja for PIC-102, and Smith for PDIC-101—to ensure accurate dynamic characterization of the process [2,4,6,7,15]. Performance assessments demonstrated that the cascade controller tuned with the Lopez ISE method enabled markedly superior control of the critical compressor–reactor pressure differential compared with the existing PI controller. The cascade configuration reduced control errors by more than 98%, provided substantially better disturbance rejection, and maintained stability even under extreme flow rate disruptions that caused shutdown under PI control. These improvements directly translate into enhanced operational reliability, increased robustness to vapor-phase disturbances, and improved energy efficiency across the PTA oxidation process, in agreement with recent findings on advanced cascade strategies [6,7,8,9,10,11].

Overall, the results establish that a tailored cascade control strategy represents a significantly more effective and resilient solution for managing safety-critical pressure differentials in PTA production. These findings demonstrate that a tailored cascade control strategy provides a significantly more reliable and resilient solution for controlling the pressure differential between the compressor and oxidation reactor in PTA production. The proposed approach enhances operational reliability, improves disturbance tolerance, and reduces the risk of shutdowns, thereby contributing to safer and more energy-efficient plant operation. The methodology and results presented in this work offer a practical and transferable framework for upgrading legacy single-loop pressure control systems in large-scale industrial chemical processes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.K.K., R.A. and A.W.; methodology, A.K.K., T.A., R.A. and A.W.; validation, R.A. and A.W.; formal analysis, A.K.K. and T.A.; resources, A.W.; data curation, A.K.K.; writing—original draft preparation, A.K.K. and T.A.; writing—review and editing, R.A. and A.W.; visualization, A.K.K. and T.A.; supervision, R.A. and A.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Marlin, T.E. Process Control: Designing Processes and Control Systems for Dynamic Performance, 2nd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Kaya, I.; Tan, N.; Atherton, D.P. Improved cascade control structure for enhanced performance. J. Process Control 2007, 17, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.O.; Gasmelseed, G.A.; Karama, A.B.; Musa, A.E. Cascade control of a continuous stirred tank reactor (CSTR). J. Appl. Ind. Sci. 2013, 1, 16–23. [Google Scholar]

- Karimi, M.; Jahanmiri, A. Nonlinear modeling and cascade control design for multi-effect falling film evaporators. Iran. J. Chem. Eng. 2006, 3, 52–63. [Google Scholar]

- Kristanto, D.; Hermawan, Y.D. Comparative analysis between PI and cascade control in heater–PFR system. Reaktor 2020, 20, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singha, P. Robust PIDF–PID cascade control scheme for delay-dominant chemical processes. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2025, 173, 106165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrico, B.C. Control of cascaded series dead-time processes with ideal cascade structure. J. Process Control 2024, 133, 103047. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D.; Gao, C.; Sun, Y.; Wang, W.; Zhu, S. Reinforcement learning control strategy for differential-pressure setpoint in large-scale district cooling systems. Energy Build. 2023, 282, 112778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Li, X.; Zhang, Y.; Dong, J.; Han, Z.; Zhou, B. Variable pressure-differential fuzzy control method for multi-split backplane cooling system. Int. J. Refrig. 2024, 161, 176–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadirov, Y. Reactor temperature and pressure cascade control in PVC production. E3S Web Conf. 2023, 431, 05003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurz, R.; Brun, K. Process control for compression systems. ASME Turbo Expo Proc. 2017, 140, GT2017-63005. [Google Scholar]

- Fadzil, N.A.M.; Rahim, M.H.A.; Manium, G.P. A review of para-xylene oxidation to terephthalic acid. Chin. J. Catal. 2014, 35, 1641–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomás, R.A.F.; Bordado, J.C.M.; Gomes, J.F.P. p-Xylene oxidation to terephthalic acid: Process optimization review. Chem. Rev. 2013, 113, 7421–7469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kleerebezem, R.; Mortier, J.; Pol, L.W.H.; Lettinga, G. Anaerobic pre-treatment of petrochemical terephthalic acid effluents. Water Sci. Technol. 1997, 36, 237–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tangirala, A.K. Principles of System Identification; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Wahid, A.; Susanto, B.H.; Andika, R.; Utami, T.S. Pengendalian Proses: Batch dan Kontinyu; Universitas Indonesia: Depok, Indonesia, 2024. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.