Abstract

Background: nowadays, traditional delivery options are challenging to the urban last-mile logistics and sustainability goals. The purpose of this study is to investigate the practical factors that drive frequent e-shoppers to actively switch their intention from conventional delivery options to utilizing smart lockers. Methods: the hypothetical framework tested integrating constructs from the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) and the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), and supplementary constructs such as privacy and convenience. Data were collected via a structured online questionnaire from 513 respondents in major Egyptian cities, including Alexandria and Cairo. The framework was tested using Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) via SmartPLS 4.0 software to assess the relationship between constructs and switching intention. Results: the analysis confirms that switching intention to use smart lockers is positively driven by Perceived Usefulness, Perceived Ease of Use, Convenience, Privacy, and Perceived Behavioral Control. Notably, a positive attitude towards smart lockers was found to have a non-significant effect on the intention to switch in the Egyptian context. Conclusions: this research contributes to addressing the gap in the extant literature by focusing on analyzing the unique contextual determinants in the emerging last-mile logistics within a developing market context.

1. Introduction

From time to time, the world has endured different global pandemics, which have had other influences on all industries, and the most recent pandemic is Coronavirus (COVID-19), which occurred from 2019 to 2021 [1]. The preventive actions taken to contain the crisis have impacted the political, sociocultural, economic, and business landscapes due to the evolving consumers’ shopping behavior from brick-and-mortar stores to e-commerce platforms [2,3]. On the other hand, the development of technologies and the fast-evolving digital societies have enabled switching between different purchasing channels, performing required post-purchase activities, and easily searching and comparing products from various offline and online sources before buying [4]. The boom of the e-commerce market has significantly increased the complexity of last-mile logistics, as consumers demand faster and more flexible delivery methods [5]. This ended up switching the last-mile logistics activity from a supporting capability to the most critical component in all business models [6]. Therefore, the delivery method must be at a satisfactory level to retain their existing consumer for more orders [6,7]. The growth of in-home delivery methods and the rise in last-mile logistics services for small parcel distributions have increased the delivery attempts and the circulation of cargo vehicles, mainly in urban cities [7,8].

As e-commerce is now moving towards frequent deliveries, small parcel sizes, and enhanced returns [9]. Therefore, finding new alternatives to mitigate the impacts of last-mile logistics activities on cities, such as smart lockers [10,11]. Smart lockers are considered as a “scalable, customizable, electronic, and often cloud-based systems that give remote and onsite users and workers an accessible space for the retrieval of parcels and letters”, which is considered a low investment cost for delivering promising items that could support the last-mile logistics profitability practices [12].

Smart lockers are considered an opportunity to increase the efficiency of last-mile logistics activity and as an attraction for many consumers to use a green service for home delivery [13]. Through increasing customer sentiment, decreasing the number of in-transit stoppages, increasing the flexibility of receiving any parcel as the customer will choose the required location and time of receiving, reducing the failure rate of delivery, effectively integrating reverse logistics services, and contributing to pressure on the traffic system reduction [14]. Applying these lockers will decrease the total shipping cost by up to 53% which can be an incentive for customers to try these new concepts [15]. Nevertheless, there is a notable gap in studying the comprehensive view on the main behavioral factors that affect consumers’ switching intention from home delivery to using these smart lockers [16].

Most of the existing behavioral research on the last-mile logistics focuses mainly on the factors that influence the acceptance of new technologies, rather than the behavioral processes of displacing a satisfactory conventional service, such as home delivery. Therefore, this study seeks to bridge this gap by determining the switching behavior necessary to achieve a meaningful market penetration for adopting new unconventional last-mile logistics methods such as smart lockers.

Moreover, most studies focusing on the adoption of smart lockers are concentrated in developed markets, such as Europe, where technological infrastructure and consumer familiarity with automated services are well established. The emerging e-commerce market in the context of Egypt has unique behavioral considerations that are under-researched; these may include a lower level of digital trust and varying degrees of access to technology. Hence, the factors driving switching intention in developed contexts, such as European cities, may differ from those in emerging markets, such as Egypt; therefore, behavioral models must be validated within this specific culture to provide actionable managerial insights. The following are the formulated questions for this study:

RQ1. What are the primary limitations that currently hinder the large-scale deployment of unconventional last-mile logistics methods in major Egyptian urban areas?

RQ2. What are the relationships between key variables of an integrated behavioral framework, such as the Theory of Planned Behavior and the Technology of Acceptance Model, and a customer’s intention to adopt smart lockers?

RQ3. How will each variable identified from the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) and the Theory of Acceptance Model (TAM) impact the Egyptian consumers’ switching intention towards using smart lockers?

This research aims to empirically examine the factors affecting customer intention to adopt and switch to the use of smart lockers as a sustainable last-mile delivery option for any forward or reverse fulfillment processes, with a particular focus on the context of Egypt. Additionally, this research examines a suggested framework related to key theories underpinning customer switching intentions, such as the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) and the Technology Acceptance Model Theory (TAM), to investigate the customer switching intention.

The structure of this research is organized as follows: first, the theoretical background is reviewed, establishing the constructs and the necessary theories to develop the research conceptual model and its hypotheses in the Egyptian context. This is followed by the methodology used to test the proposed framework. Then the paper concludes with a discussion of the analysis and findings, followed by a conclusion and recommendations for further research.

2. Theoretical Background

Due to the global environment brought about by COVID-19, the shift towards non-traditional e-commerce channels and the demand for home delivery as an unprecedented channel for fulfilling orders have been significantly accelerated [9]. E-commerce, which involves different business activities performed using internet technologies, has seen its growth rapidly, especially in the B2C e-commerce sector, which is considered one of the significant applications of Information and Communication Technology (ICT) that first started in the United States [17]. The B2C e-commerce is considered a rapidly growing phenomenon, and its importance has been increasing in many countries in both emerging and mature markets across different industries, which opens new challenges for many companies to handle some issues, one of which is the complexity of managing their logistics activities, such as last-mile logistics [16].

The last-mile logistics, which is the final stage of the order fulfillment process that aims to deliver the required products that were ordered through online websites or applications to the final consumers, became critical during the pandemic and represents as a crucial part of the entire value chain, even though this part is considered the most complicated and inefficient stage in any supply chain and have a significant impact on the bottom line profitability, transaction cost, and the customer service level, as this is the stage where the sale is often realized tangibly after anticipating the way of receiving them [18]. Additionally, the last mile logistics activity is the most expensive and least efficient part of any delivery process due to challenges faced in meeting target service levels, the high level of dispersal of destinations, and the small dimensions of orders [19]. Therefore, the process of the last-mile logistics is initiated by final consumers and aims to deliver specific products to specific destinations, while involving the use of different storage facilities, modes of transport, and handover options [16].

As the last-mile logistics is the only direct link and the final stage in any supply chain that directly deals with the customers, the efficiency of the delivery and its performance directly impacts the customer’s satisfaction, which in turn is an indicator for any logistics company to be competitive in the market [20]. On the other hand, the delivery service is considered a critical indicator that directly impacts customer loyalty, which can be impacted negatively in case of any delivery delays and has a direct influence on their satisfaction and repurchase intentions [21]. Despite being the most complicated, polluting, inefficient, and costliest activity of any supply chain, the unprecedented demand for home deliveries has amplified existing logistical issues, such as an increasing number of vehicles or motorcycles, increased traffic congestion, and an increased percentage of CO2 emitted [22,23]. In addition to the environmental sustainability aspect, the last mile logistics has numerous operational issues in different aspects, including the costs, the time pressure, and increasing volumes [22,24]. Whereas the cost considerations are particularly relevant to balance cost-effectiveness with sustainability measures to achieve a highly competitive market, and these costs include the commercial vehicle insurance, fuel cost, and road infractions because of waiting and parking in congested areas [24]. Despite focusing on optimizing each vehicle’s route, much of the time is spent in the last mile logistics during the last meters of the delivery, when searching for the exact apartment locations while avoiding reaching the wrong place, going to the doors to deliver the parcels, and returning [25].

In the Egyptian market context, as a developing market, home delivery option is usually utilized by consumers as the main last-mile logistics method due to the characteristics of the local environment and the underlying cultural preferences [8]. Therefore, the increase in e-commerce will imply a higher number of deliveries in different areas that might increase the traveling distance between customers located in different geographical areas, which poses challenges to logistics providers. At the same time, the urbanization trend that refers to the increasing tendency of people to move to urban areas will affect and influence route planning [22]. And this population density growth in urban areas will reduce the number of parking spaces, which will increase the traveling distance and time loss as this will increase difficult of fulfilling customers’ expectations in terms of both punctuality and speed, this is besides the existence of traffic congestion that will lead to uncertain traveling time, which will increase level of missed deliveries [26].

On the other hand, the cost of missed and multiple deliveries is considered the main challenge to last mile logistics as it adds to the system’s inefficiency, as it cost the time spent to delivery attempt twice one while being unable to reach the final destination and the other one the time spent to re-attempt this delivery on a different day, or the packages that are not consolidated in one shipment and delivering in more than two attempts to complete the delivery [27]. The failure rate can vary depending on each country, from 2% to 30%, and these failed deliveries affect customer satisfaction as well, since the customer in that case will pick up their parcel by themselves from the depot of the logistics providers [28].

One of the most trending and sustainable delivery channels is called “smart lockers”, which is considered as one of the unconventional last-mile logistics channel which can be described as a self-collection delivery that involves the existence of a network of service points where the operators can deliver their customers’ parcels, and the customer is responsible for paying, collecting, and re-turning their parcels [29]. Smart lockers have been established in many locations for several years and are popular as an alternative to home deliveries, which can be the most cost-effective and environmentally friendly alternative that reduces the number of failed delivery attempts [30].

Most of the customers are avoiding using any innovative delivery options other than the conventional delivery method [31]. Therefore, logistics service providers must encourage them to switch by illustrating the advantages of using smart lockers or by offering additional incentives, since most online shoppers are price-conscious, and any price reduction offered for using smart lockers will be a motivation to make the switch [32].

2.1. Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB)

The Theory of Planned Behavior expands upon the Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA), which focuses on social psychology to explain how both motivational and informational influences drive behavior, suggesting that customers make behavioral decisions after considering available information carefully which includes three determinants that influence customers’ intention such as attitude, Perceived Behavioral Control (PBC), and subjective norms (SN) [33]. Firstly, the Attitude factor, which is the tendency to interact with a situation or object favorably or unfavorably, is considered an important factor to determine consumer behavior [34]. Recently, most of the companies have been focusing on implementing strategies to change individuals’ attitudes towards any new product, service, or delivery methods [35]. Secondly, the Perceived Behavioral Control (PBC) describes the perception of how easy or difficult it is to perform any behavior [36]. The PBC combines the beliefs about any factor that inhibits or enables the performance of any behavior or the perception of how much these factors will constrain or improve the execution of any behavior [37]. Lastly, the subjective norms, which are considered the way of determining the influence of individuals who are important to the decision makers on the perception towards any specific behavior, such as family and friends [34]. A meta-analysis was previously conducted and found that subjective norms are generally considered the weakest predictor of any intention [38]. It has been suggested that the attitudinal components are more effective than normative components in determining any behavioral intentions as generally the personal consideration over-shadowing the influence of perceived social pressure, and any behavior could be influenced by other types of norms, such as personal norms, which refer to the individual’s feeling of personal obligations or their commitment to conduct a specific behavior [33].

The Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) is considered a prevalent framework for understanding the customer switching intentions within the last-mile logistics context. Specifically, the TPB theory has been utilized to investigate Thai consumers’ intention to utilize smart lockers [39]. It has also been used to study consumers’ switching intentions to adopt an unconventional last-mile logistics service during the COVID-19 pandemic [40] and to examine socio-behavioral factors towards adopting a green last-mile delivery [41]. Additionally, the perceived value has been employed to analyze customers’ switching intention towards adopting smart lockers, where factors such as Privacy and Convenience were found to be mediated by perceived value [42].

2.2. Technology of Acceptance Model Theory (TAM)

This Theory explains the adoption of any new technology by determining the customer’s behavioral intention to use that technology, mainly through Perceived Ease of Use and Perceived Usefulness [43]. The Perceived Usefulness (PU) concept is expanded beyond customer convenience to include more social values, such as the positive sustainability contribution, as well as referring to the customer’s belief that any technology can improve their experience and performance to achieve a desired outcome, such as avoiding the risk of package theft, any inconvenience, or missing deliveries [44]. The Perceived Ease of Use (PEOU) is considered the degree to which the customer believes that using any system will require minimal effort, for smart lockers, the PEOU is influenced by the clarity of instructions of retrieval packages, the simplicity of the application’s interface, and the user-friendly design for the seamlessness of the physical interactions with the smart lockers to make it easy to learn how to use these smart lockers [45]. Therefore, the adoption of any new technology not only depends on its usefulness but also on customers’ feeling confident in their ability to interact with these lockers; any complex interface will lead to frustration or potential rejection of using that technology [41].

Most of the research related to testing the customers’ switching intention towards using any new last mile logistics method, the “TAM” Theory was proposed to better understand how Perceived Ease of Use and Perceived Usefulness affects the switching intention towards any new technology, many studies have extended this model by adding more theories or dimensions to be analyzed to use new last mile logistics method [46]. In addition to TAM, the “TPB” Theory is proposed to predict the behavior of humans in social situations and their intentions through determining the effect of an individual’s attitude, Perceived Behavioral Control, and subjective norms on their switching intentions [47].

In the context of determining the factors affecting customer switching intention and the adoption of the smart lockers, the theory of the acceptance model and the attitude factor of the Theory of Planned Behavior were used to examine customer switching intention, and it was found that the perceived sustainability has a significant influence on the acceptance of the delivery methods [48]. The primary factors of the theory of the acceptance model and the attitude factor of the Theory of Planned Behavior influencing customers’ switching intention to use smart lockers were analyzed, and the results highlighted the necessities for urban logistics regulations to be adjusted to new delivery methods such as smart lockers through matching smart lockers’ service offerings to different means of transport while taking into consideration these lockers placement [49]. The attitude factor of the Theory of Planned Behavior was used to test behavioral intention through the Integration of habit into the unified TAM theory and the use of technology, and it was found that the results suggest that the rational and the irrational factors determine the consumers’ usage of main logistics technologies [50]. The TAM theory and the attitude factor of the TPB theory were used to examine the consumers’ decisions to use smart lockers, which is used to understand the consumers’ decision-making processes through adopting smart lockers by considering Privacy protection and technology assessment [51]. A study on consumers’ adoption of self-collection service via Automated Parcel Station was conducted by examining how the perceived characteristics of these lockers are present to indirectly influence the consumers’ adoption intention through attitude, and it was suggested through the application of TPB that the people’s adoption intention is influenced by two factors, Convenience and risk on attitude [52]. The factors affecting customer usage and acceptance of smart lockers for last-mile logistics in rural areas were examined based on the theory of the acceptance model, and it was suggested that these smart lockers are a valuable solution, especially in rural areas with poor infrastructure, to provide a secure and convenient alternative for customers to improve their delivery efficiency [53].

3. Conceptual Framework and Hypotheses Development

The decision to switch from a well-established and conventional last-mile service to a new alternative, such as smart lockers, will require a theoretical lens seeking a synergistic model for maximum predictive power that each theory cannot provide independently. The TAM constructs are essential to capture the main cognitive evaluation of smart lockers as a technological innovation, which are considered as pull factors based on the technology’s features, resulting in a positive attitude towards the service, which is considered as the main construct of TPB theory.

On the other hand, studying the TAM constructs only for this specific behavior is insufficient, as it requires managing the external complexities of the last-mile logistics; in particular, it is vital to address consumers’ perception of having the control and opportunity to switch to use any new system and change their reliable delivery habit. To predict and study switching intention accurately, an integrated framework combining constructs of TAM and TPB will maximize the explanatory power required to determine the behavioral change needed for the successful adoption of smart lockers in Egypt. Accordingly, it is necessary to focus on the consumer’s perceptions of usefulness, Ease of Use, Control, Privacy, Convenience, and their attitude toward it. Therefore, in this section, and based on the theoretical background highlighted, the conceptual model will be derived to study the relevance between the TPB theory and the TAM theory in relation to customers’ switching intention.

3.1. The Mediating Role of Attitude Factor of the Theory of Planned Behavior in the Relationship Between Technology of Acceptance Model and Customer Switching Intention

As outlined in the review, the attitudinal factors, such as personal consideration, are more effective in determining any behavioral intention. Therefore, this research’s conceptual framework draws on the well-established TAM theory that studies the acceptance of technological innovations and considers the Perceived Ease of Use (PEU) and Perceived Usefulness (PU) as the main determinants, and is measured by the consumer’s attitude towards the customer’s usage intention, which has been established in the field of consumer behavior in e-commerce [54,55]. The factors that affect the adoption of smart lockers were explored, particularly examining the relationship between attitude and Perceived Ease of Use towards these smart lockers, as Perceived Ease of Use refers to the customer’s beliefs that these lockers will require minimal effort to learn and operate, and a user-friendly option, in a simple terms, the customers are willing to adopt the more straightforward and convenient option they find [39]. Therefore, there is a positive relationship hypothesized between these two factors, and it is suggested that if the customers perceive these smart lockers as easy to use, navigate, and locate, they will develop a more positive impression of using them, and accordingly, will translate into a higher likelihood of adopting smart lockers for their future purchases [49]. On the other hand, the connection between the Perceived Usefulness and attitude factors towards smart lockers has been previously tested, which emphasizes determining the importance of understanding customers’ perception of adopting smart lockers in the last-mile delivery, resulting in finding a positive relationship hypothesized between Perceived Usefulness and attitude, particularly when the customers perceived that the smart locker offering a valuable benefits and fulfills their need such as reducing missing deliveries, providing a secure alternative of home deliveries, and streamlining the receipt of packages [41,45]. These studies confirmed the suitability of using the determinants of Perceived Ease of Use and Perceived Usefulness to investigate an individual’s attitude and provide substantiation, as well as the attitude on customer switching intention to use smart lockers [56]. The attitude towards a specific behavior refers to the degree to which that consumer views a particular behavior as favorable or unfavorable. Therefore, any positive attitude towards switching will be positively related to switching intention in several studies related to service switching [57]. Additionally, the attitude towards switching intention is considered an important factor in any exploratory study of predictive factors in switching behaviors. Accordingly, a positive attitude towards smart lockers might increase the likelihood of switching intention of the sustainable last-mile delivery options using smart lockers as a tool. On the other hand, consumers who have negative attitudes toward smart lockers might be more hesitant to switch to them [58]. Therefore, this research hypothesizes that the impact of the Technology Acceptance Model constructs of Perceived Ease of Use and Perceived Usefulness on customers’ final intention to switch is not direct, but rather it is mediated by a positive attitude. Accordingly, this research investigates the following direct and mediating hypotheses:

H1:

Perceived Ease of Use of smart lockers significantly and positively influences customers’ attitude towards utilizing smart lockers as a sustainable last-mile delivery option.

H2:

Perceived Ease of Use of smart lockers significantly and positively influences customers’ intention to switch to sustainable last-mile delivery options that utilize them.

H3:

Perceived Usefulness of smart lockers significantly and positively influences customers’ attitude towards utilizing smart lockers as a sustainable last-mile delivery option.

H4:

Perceived Usefulness of smart lockers significantly and positively influences customers’ intention to switch to sustainable last-mile delivery options that utilize them.

H5:

A positive attitude toward smart lockers significantly and positively influences customers’ intention to switch to sustainable last-mile delivery options utilizing smart lockers.

H6:

A positive attitude toward smart lockers significantly mediates the relationship between Perceived Ease of Use and customer switching intention toward sustainable last-mile delivery options that utilize smart lockers.

H7:

A positive attitude toward smart lockers significantly mediates the relationship between Perceived Usefulness and customer switching intention toward sustainable last-mile delivery options that utilize smart lockers.

3.2. The Mediating Role of Perceived Behavioral Control Factor of the Theory of Planned Behavior on the Influence of Convenience and Privacy on Customer Switching Intention

Convenience is the main attractive factor that brings two main values related to time and geographical area [59]. The pick-up points for collection play a major role in any e-commerce business, as they affect the operational costs and the customers’ needs [60]. In the Egyptian market context, the value of the Convenience dimensions is amplified by local structural inefficiencies, as a developing market and still heavily reliant on conventional methods will increase e-commerce demand, straining the existing last-mile logistics systems [8]. As well as the urbanization trends and high population density in cities such as Alexandria and Cairo can lead to significant logistical challenges, including a reduction in the available parking spaces, congestion, resulting in uncertain parcel travel time, and difficulty in meeting punctuality expectations [26]. For instance, based on geographical convenience, these smart lockers will be located near to customers’ residences, workplaces, and public areas to accommodate all customers who have a mobile lifestyle, based on the time value, it will operate 24/7, which will reduce the opportunity cost or unnecessary waiting time till delivering at home through and they can proactively receive their parcels at any time which will focus on both access convenience and time convenience as critical antecedents to behavioral control and directly mitigate these geographical and structural barriers [41]. In this era, and mainly post-COVID-19 lockdown, all customers are more excited about and receptive to all new mobile technologies, and implementing these smart lockers will be connected to their smartphones for any transactions of receiving and returning their parcels [61]. Therefore, the convenience represents an important factor of a consumer’s Perceived Behavioral Control, which will reduce effort and unproductive use of time and increase in enjoyment and excitement emotions. As previously suggested, the location of these smart lockers plays a major role in the e-commerce business, and their locations affect customers’ needs and the companies’ operational costs [60]. It was also identified before that most of the customers prefer the location of these smart lockers to be on their way home from their office buildings [62]. The Privacy is the most influential factors that reflect the customer’s perceived value as most customers now are more concerned about Privacy matters indeed, in light of increasing digitalization, it is becoming one of the most important concerns of customers, therefore the Privacy feature of the smart locker can reduce any human interactions and let them manage their private information and payment by themselves and prevent themselves from being revealed to transport operators during the delivery process [63]. The usage of security protocols such as face recognition, OTP codes, and scanning QR codes will encourage the perceived trust value from customers and reduce perceived security risk associated with the usage of the smart locker [64]. On the other hand, the perception of security issues may be reflected in unnecessary precautions such as effort spent researching the security system, adopting any preventive measures against any potential violation, and assessing the risks of handing over personal information to the websites [32]. The third antecedent of the TPB is Perceived Behavioral Control, which is defined as a consumer’s perception of the difficulty or ease of adopting any services in any context [65]. According to the TPB, it indicates that the higher the Perceived Behavioral Control over any specific behavior, the more likely its occurrence [33]. There are a lot of studies suggesting a positive relationship between the Perceived Behavioral Control and the switching intention towards any new system or innovation [66]. So, when the customer noted that they have the necessary skills, resources, and knowledge to decide on which sustainable last-mile delivery to switch to, they might be confident that they could overcome any obstacles that may occur while switching to a new delivery method. On the other hand, if they anticipate high obstacles and complexity during this switching, they may be less likely to switch when they believe that this switching will cost them risk, extra time, extra money, and they may lack confidence in their ability to complete it. The customers will switch to use smart lockers if they provide them control compared to other last-mile delivery options, and it posits that the perceived control is considered as a superordinate goal when the customers’ switching intention is a subordinate goal [67]. Therefore, this research argues that both constructs of convenience and privacy are external factors that can boost consumers’ control and confidence in any process, which, in turn, drives switching intention. Accordingly, this research will investigate the following hypotheses, including the mediation effects:

H8:

The Convenience of smart lockers significantly and positively influences customers’ Perceived Behavioral Control towards utilizing smart lockers as a sustainable last-mile delivery option.

H9:

The Convenience of smart lockers significantly and positively influences customers’ intention to switch to sustainable last-mile delivery options that utilize them.

H10:

The Privacy concerns about smart lockers significantly and positively influence customers’ Perceived Behavioral Control towards utilizing smart lockers as a sustainable last-mile delivery option.

H11:

Privacy of smart lockers significantly and positively influences customers’ intention to switch to sustainable last-mile delivery options that utilize them.

H12:

Perceived Behavioral Control regarding smart lockers significantly and positively influences customers’ intention to switch to sustainable last-mile delivery options that utilize them.

H13:

Perceived Behavioral Control regarding smart lockers significantly mediates the relationship between Privacy concerns and customer switching intention toward sustainable last-mile delivery options that utilize smart lockers.

H14:

Perceived Behavioral Control regarding smart lockers significantly mediates the relationship between convenience and customer switching intention toward sustainable last-mile delivery options that utilize smart lockers.

3.3. The Developed Conceptual Framework

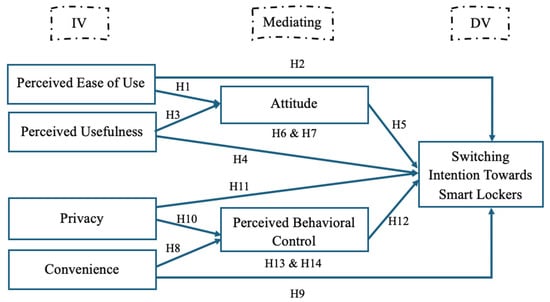

As highlighted in the literature, the attitudinal factors are considered as the central to predict the customer’s behavioral intentions, which led this research to build a conceptual framework based on the Technology of Acceptance Model (TAM) and Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB). Additionally, the review has highlighted the crucial role of the operational and psychological factors, such as Perceived Usefulness and Perceived Ease of Use, as primary drivers that influence customers’ attitude towards any new last-mile logistics options [39,41,55]. Furthermore, factors such as Privacy, which is secured by some features such as the reduction in human interactions, and convenience, which is linked to flexible 24/7 operation and optimal geographical location, strongly influence consumers’ Perceived Behavioral Control regarding service adoption [60,63,65]. Hence, Figure 1 illustrates the hypothesized framework for the research by integrating the main constructs from established behavioral theories, such as TPB and TAM theories, to provide a comprehensive view of the variables affecting customer switching intentions and the relationship between various behavioral and attitudinal factors.

Figure 1.

The Proposed Framework.

Therefore, the hypothesized framework will be examined empirically to investigate how customers’ perception towards smart lockers will affect their Perceived Behavioral Control and attitude, and, ultimately, their intention to switch to using smart lockers as a sustainable last-mile delivery method. According to what was mentioned above regarding the importance of testing the subjective norms factor of the Theory of Planned Behavior, in this research, the subjective norms will not be considered, as these are determined by social pressure, and due to the lack of the studies examining the usage of smart lockers in Egypt is not common, the effect of this social pressure will not exist. Accordingly, attitude and Perceived Behavioral Control are considered the most important predictors of intention, while subjective norms are not significant [68].

4. Sample and Data Collection

In this section, the research methodology used to investigate customer switching intention towards sustainable last-mile delivery options using smart lockers as an example. The following methodology will be selected to generalize outputs that contribute to the understanding of consumer switching intention and behavior in sustainable logistics. Firstly, this chapter will describe the research design followed and the data collection method used, and its analysis technique will be followed.

This research follows the “Positivism Approach” and is called the “Positivist Paradigm” as well, which asserts that there is an objective, single reality that can be measured systematically [69]. This research approach seeks to establish a causal relationship and to generalize its findings between specific, measurable variables and customer behavior [70]. It is confirmed that the continued relevance of this approach, particularly when the quantitative nature is mainly used to verify and test existing theories [71]. This positivist approach will be employed through a descriptive nature to describe the population’s characteristics and quantitative methodology through a systematic approach to collect and analyze numerical data for objective measurements and analyzing social phenomena [72]. In this case, it is testing the consumer behavior regarding the sustainable last-mile delivery options. Therefore, the hypothetico-deductive approach will be followed, which is the main component of the Positivism Approach [73]. This research will begin with developing a theoretical framework, then formulating a testable hypothesis, which will be derived from the existing theory, this is considered an application of a deductive reasoning, where the researcher generate from a general theory such as Technology of Acceptance Model (TAM) and Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) a specific empirical observations and conclusions and then the hypotheses will be tested using collected data from large sample [74]. This research follows a conclusive design to provide specific decisions after testing research variables and research questions, whether to confirm or to reject any relationship between two variables, rather than exploring new ideas [75]. Which is in this case as follows: Independent Variables are Perceived Ease of Use (PEU), Perceived Usefulness (PU), Privacy (PRI), and Convenience (CON). The Mediating Variables are Attitude (ATT) and Perceived Behavioral Control (PBC). The Dependent Variable is the switching intention (SI) towards the sustainable last-mile delivery option using smart lockers. Following the conclusive design, all findings from these tested variables will be generalized to all population, to produce an objective that can be applied beyond a specific studied sample but applies to the broader consumer base, which is the main objective of adopting the positivist approach [69,76]. This generalizability is achieved through using a representative sample and statistical analysis tools to extend the conclusions of the relationship between tested variables to a large population of customers [77].

As mentioned, online shopping is booming in Egypt, as most of the online shoppers in Egypt spend their time on social media; therefore, the population includes a wide range of different ages, starting from 18 years old to more than 50 years old. On the other hand, it was suggested that an adequate sample size ranging between 30 and 500 can be suitable for a wide range of research [78]. Therefore, a total of 513 responses were received and used for the analysis. This study employed a non-probability convenience sampling technique, specifically utilizing the river sampling method to collect data. This approach involved intercepting potential participation online through an English language e-questionnaire distributed via social media platforms using a five-point Likert scale. The river sampling method was followed by two factors: firstly, the defined population of online shoppers is inherently digital and dispersed across geographical areas such as Alexandria and Cairo, secondly, the methodology was chosen as a practical and safe data collection tool in response to the operational constraints imposed by the global environment brought about by COVID-19, which accelerated the shift towards non-traditional data collection channels [79]. Additionally, to ensure data quality and respondent integrity in the online survey was managed through strict technical and design controls were used. To enforce the one-vote-only rule, a key technical restriction was implemented as the survey form required participants to sign in and was configured to allow only one submission per email account [80]. The measurement model was strictly designed using reflective constructs, which are theoretically and empirically differentiated from formative ones by assuming that the latent construct causes the variance in its measured indicators, making the items interchangeable manifestations of the construct [81]. Consequently, no constructs in this study were represented as formative.

Additionally, to analyze the proposed model and to test the hypotheses, this study will use the structured Equation Modeling to test the significance of the relationship between each pair of variables in the conceptual framework using the SmartPLS 4.0 software.

4.1. Sample Characteristics

The hypothetical framework was tested through a structured online survey, where data were collected in September 2025. A total of 150 respondents were used for a pilot trial, and 513 respondents for the main study, without any invalid responses (the response rate is 100%), the following Table 1 illustrates the characteristics of the research sample for the main study in terms of their age group, gender, occupation status, city, the frequency of online shopping per month, the number of failed attempts from March to August, 2025, their previous experience of online purchase, in-store pickup, their preferred products for smart locker pickup, the e-commerce delivery choice, and their preferred location for smart lockers

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Respondents.

4.2. Research Scales

The online survey instrument consisted of the following seven constructs: Perceived Usefulness (PU), Perceived Ease of Use (PEU), Attitude (ATT), Convenience (CON), Privacy (PRI), Perceived Behavioral Control (PBC), and switching intention (SI). The online survey was in English, and all items were assessed through a five-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = neutral, 4 = agree, 5 = strongly agree). Appendix A illustrates the details of each construct.

4.3. Pilot Study Testing

Researchers usually conduct a pilot study of a small sample before analyzing the large sample to check whether the tools, sampling, and methodology applied are appropriate [82]. Therefore, after collecting data through a structured survey as a secondary data tool to support primary data, a pilot study of 150 responses was conducted using SPSS Version 25 to assess the reliability and validity of the measurement variables and determine if any adjustments were required. Consequently, testing the Cronbach’s Alpha value to test the reliability coefficient and to indicate whether the items in each variable are positively correlated to each other or not [83]. The accepted value of the Cronbach’s Alpha value is within the range of 0.70 to 0.92, as it is considered to have a good internal consistency [84].

Firstly, Table 2 illustrates the suitability of these data for each factor analysis was confirmed using the Sampling Adequacy measure of Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) and the Sphericity using Bartlett’s Test. All seven variables’ KMO values are consistently meritorious as they range from 0.726 as a lowest limit for (switching intention) to 0.895 as an upper limit for (Perceived Usefulness). Additionally, Bartlett’s Test p-value of each variable is (p = 0.000), considered statistically significant. These results confirm that the data exhibit a sufficient inter-variable correlation, and the sample size is adequate to proceed with the analysis [85]. Secondly, the validity of the scales was established by examining the factor loadings, and to check the internal consistency through Cronbach’s Alpha measure. The factor loading analysis for each variable must be above 0.4 to be significant; otherwise, the cross–loading will result, and one or more factors should be eliminated from the analysis [86]. Lastly, and in terms of reliability, the stated results indicate the excellent internal consistency of all variables, whereas each variable value ranging between 0.801 for the (Convenience) and 0.920 for the (Perceived Usefulness) is passing the reliability benchmark level of alpha “0.70”. The strong alpha values for the switching intention (0.913), Privacy (0.916), and Perceived Usefulness (0.920) confirm that the items of each variable are measuring their respective concepts and ideas accurately and consistently.

Table 2.

Validity and reliability test for the pilot study.

In summary, the pilot study analysis indicates that the tool used for the data collected is applicable, as the validity and reliability tests had reasonable results within the accepted range, confirming the robustness of the data to test the hypothesized relationships using SEM analysis in SmartPLS 4.0.

5. Results

5.1. Descriptive Analysis

The main respondents’ demographic data concentrated on the adult consumers who are living in a major urban center and who value control and convenience over their time. As most of the respondents are female, with 59.5% of all respondents, which is considered a significant value, as women are considered the main household shoppers, providing their preferences for an efficient and convenient delivery method will be impactful for any business. The highest age group of the respondents is between 35 and 44, with 33.5% of the total respondents, which typically relates to the adults who are often managing their career and their family and household responsibilities, followed by 24% of the respondents who are between 18 and 24, and 21.4% of the respondents are between 45 and 54, for the 25–34 age group, it is only 17.3%, and the rest are only small group of people who are aged between 55 and 64 years old with almost 3.7% from all respondents. Most of the occupation status of the respondents are employed with 64.3% and students with 21.6% which means that they have busy schedules and need a convenient delivery option to fit their lifestyle. The rest, 8.4% are housewives, and 5.3% are unemployed. The data is concentrated in the densely populated urban area, with most of them in Alexandria, with 77% of the respondents and 19.4% in Cairo, and 3.6% in Giza and in the other cities.

The following section, which relates to the behavioral data, shows a strong respondent’s preference for choosing an alternative method that will give them more control over their pickup processes. Fifty-eight point nine percent of the respondents have already tried the in-store pickup before; this high rate demonstrates that the e-shoppers are willing to use other delivery methods from a traditional home delivery model, the rest are 38.2% who have not tried the service of in-store pickup before, and 2.9% of the respondents are not online shoppers. Additionally, the high percentage rate of the respondents who prefer using the smart lockers 61.4% over traditional home delivery 4.1% will be considered the most powerful finding that will be analyzed through the lens of convenience and Perceived Behavioral Control from the usage of smart lockers, the 32.7% of the respondents have no preferences of choosing each method, and 1.8% are not sure about their preference. With the mention of the preferences of the respondents’ convenience and control, the majority of the respondents, 64.9% choose the preferred location of the smart location to be near to their homes, which consider a clear indication of their requirement of flexible and secure option for their pick up process, 14.6% choose to be inside shopping malls, 9.9% need it to be close to their workplace or university, 6% choose it to be at supermarkets and grocery stores, and 4.5% at gas stations.

Most of the respondents were considered e-shoppers with frequent orders per month, 33.5% who are placing from three to five online orders, 27.1% are placing from six to ten online orders, 25.3% are placing from one to two times online orders, 11.8% are placing more than 10 orders, and 2.3% of the respondents are considered not e-shoppers. Therefore, the data of the failed delivery attempts provides evidence of the previously secondary data illustrated regarding the challenges of the home delivery, even though the majority of the respondents with 59.84% had no failed delivery attempts, there are 29% experienced from one to two failed delivery attempts, and 6.23% experienced from three to four failed attempts, and 2.92% had more than five failed delivery attempts, which highlights that the failed attempts are a common enough occurrence to be a significant stress point for the consumer to be eliminated using smart lockers as it guarantees that the delivery process will not be failed with a cause of the recipient not being available at home and waiting for his package.

Most of the preferred products are to be picked up from the smart locker, 40.4% are for clothing and fashion items, 23.2% are for health and beauty products, 22.2% for electronics, 7% are for Books, media, and stationery, 6.8% are for groceries or packaged food, and 0.38% for others. Detailed information on the respondents’ characteristics and control variables is mentioned in (Table 1).

5.2. Validity and Reliability Assessments

The sampling adequacy for the analysis was confirmed by the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy and Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity [81]. The KMO value is 0.948, which is above the commonly acceptable threshold of 0.6 and the preferred threshold of 0.90. This indicates that the common variance among the items is extremely high and that the data is highly suitable for identifying underlying factors. Additionally, Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity was statistically significant (0.000). These results allow the rejection of the null hypothesis that the correlation matrix is an identity matrix, confirming that sufficient relationships exist among the variables to proceed meaningfully with the analysis [87].

Reliability is used to indicate the consistency of the results of the analysis from the original measurements when the researcher examines the same content repeatedly [86]. Therefore, it will be investigated by computing the Cronbach’s alpha value and the composite reliability for each variable. The Cronbach’s alpha for indicating how closely related a set of questions of a variable as a group and the applicability of each variable must be 0.70 or higher, while composite reliability (CR), which is used for measuring the internal consistency as it accounts for the actual loading factor for each variable and it must be 0.70 or higher to be a good indicator of reliability [88].

Table 3 relates to the reliability analysis of 513 respondents for the main study; all variables’ Cronbach’s Alpha are above 0.70, as it ranges from a high value of 0.923 for Privacy to a low value of 0.812 for Convenience, which indicates the external consistency of each single variable and suggests that the survey’s questions are designed to measure each concept consistently. Additionally, the Composite Reliability for each variable is also high, as it ranges between the high value of 0.945 for Privacy and the low value of 0.889 for Convenience, suggesting that the survey questions are highly correlated to each variable.

Table 3.

Reliability test for the Study Responses Using Cronbach’s Alpha and Composite Reliability.

To check each item quality using item-level assessment through testing the Corrected Item-Total Correlation (CITC) and the Cronbach’s Alpha if an Item is deleted, as mentioned in Table 4, all items exhibited strong CITC values, with the lowest being 0.515 for CON4 and the highest being 0.831 for PBC3. Since all CITC values are significantly greater than the typical acceptable threshold of 0.30, every item is shown to contribute strongly to the measurement of the underlying construct pool [89]. Furthermore, examining Cronbach’s Alpha if an Item is deleted column reveals that the removal of any single item would not meaningfully improve the scale’s reliability, as most of the items’ values are 0.976, which is identical to the overall Cronbach’s Alpha value = 0.977 of 32 items. In addition, for the few items where alpha deleted increases, such as CON3, CON4, and PRI1, the increase is only 0.001 to 0.977, which is statistically negligible. Consequently, there is no need to delete any of the 32 items as they all contribute positively and cohesively to the scale’s outstanding internal consistency.

Table 4.

Corrected Item-Total Correlation (CITC) and Cronbach’s Alpha if an item is deleted.

On the other hand, the validity test is used to describe the extent to which statements and questions for each variable in the survey can measure this variable in a proper way [90]. Validity analysis for the constructs could be divided into two tests, discriminant validity and convergent validity [91]. In this study, both approaches were adopted to confirm that the results of all constructs measure what they are intended to measure. Table 5 shows the validity test using factor loadings and the average variance extracted (AVE). AVE value must be more than 0.5, and the factor loading must be above 0.4 to be accepted [92].

Table 5.

Validity test for the Study Responses Using Factor Loadings Analysis and AVE.

Therefore, after eliminating the item CON4 from the Convenience variable, as its factor loading was 0.377, which means that it is less than the accepted range, the rest of the items have a good loading, and every single question is a valid indicator of each variable. On the other hand, the ranges of the AVE are between 0.667 as a lowest value for Perceived Usefulness and 0.812 as a highest value for Privacy, which indicates that the measurement model has a strong convergent validity.

For the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) value for each variable, which indicates the average amount of variance extracted for each variable, the PEU variable accounts for 68.7% of the total variance in the survey questions PEU1, PEU2, PEU3, and PEU4 which are used to measure it, which means that a single factor for PEU will be highly effective to summarize all information from these four questions. The PU variable can explain 66.7% of all information collected from the seven corresponding survey questions, and it indicates that every single factor can provide a strong measure of the main concept. The ATT variable has a value of 76.4% which explains 76.4% of the variance in its four questions, ATT1, ATT2, ATT3, and ATT4, showing a high degree of shared consistency among the questions. The CON variable captures 72.8% of the total information from its three survey questions, CON1, CON2, and CON3. which indicates that the questions are highly effective in measuring the single concept of Convenience. The PRI has the highest value of AVE, which is 81.2% which means that over 80% of the information for all related questions, PRI1, PRI2, PRI3, and PRI4, can be explained using a single underlying factor. The PBC has a value of 74.5% which explained the majority of the following five questions: PBC1, PBC2, PBC3, PBC4, and PBC5, to provide strong evidence that these questions are good indicators for the underlying concept. The SI variable has a value of 75.7% of the total variance for four items: SI1, SI2, SI3, and SI4, which confirms that the questions used to measure the SI variable are highly consistent with the intended concept.

Confirmatory factor analysis was conducted to assess the overall fit of the measurement model Table 6 Firstly, the Chi-square test () yielded a large value of 1632.063, accompanied by a highly significant p-value (0.000), which rejects the null hypothesis of perfect model fit. However, with a large sample size (n = 513), the test always results in rejection, even for excellent models [89]. Therefore, the researchers relied more on practical fit indices. Which is the () to degree of freedom () ratio, which is, in that case, 3.952, that offers a more practical measure. This value falls within the acceptable range of ≤5.0 [86]. The Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) is 0.076 with a 90% confidence interval of (0.072, 0.080). RMSEA value of ≤0.08 is considered an acceptable fit, while ≤0.06 is considered a good fit [88]. The result of 0.076 sits at the threshold of acceptable fit. Additionally, the Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) value of 0.043 is excellent, as values ≤0.08 are typically deemed acceptable, and values closer to ≤0.05 suggest a very good fit [88].The incremental or comparative fit indices assess how much this model fits the data compared to the null model, the Comparative Fit Index (CFI) and the Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI) are the most widely reported in this category, the CFI value is 0.917 and the TLI value is 0.907, and the values of ≥0.90 are generally accepted and considered as a good fit [88]. The Normed Fit Index (NFI) is 0.892, which is below but close to the conventional 0.90 accepted range and is often considered less reliable than CFI and TLI. The Goodness of Fit Index (GFI) and the Adjusted GFI (AGFI) at 0.797 and 0.756, respectively, fall below the traditional desired value of 0.90. However, these indices are known to be sensitive to model complexity and sample size, making them less reliable than CFI, TLI, and RMSEA; therefore, these values confirm that the estimated model is a highly acceptable representation of the underlying factor structure in the observed data.

Table 6.

Fit indices for measurement model.

Then the Discriminant Validity and multicollinearity were tested using variance inflation factors (VIF) in Table 7, the items in each construct range between 1.462 and 3.804, which is lower than the accepted range, which is less than 5 [91].

Table 7.

Variance Inflation Factors (VIF) for each item.

A review of the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) for the structural model paths identified a significant collinearity problem, particularly for the predictors of switching intention (SI) in Table 8. With VIFs reaching 6.828 (for PU to SI). While the structural VIFs exceeded the conventional value of 5.0 threshold [91]. Due to switching to a non-existent last-mile option is an integrated, high-uncertainty decision. Participants are not independently weighing PU, PBC, and ATT before deciding on SI; rather, they form a holistic judgment where all favorable perceptions (usefulness, ease, control) merge when evaluating the final intention. The high VIF reflects this integrated cognitive process inherent to high-risk, pre-adoption decisions [93]. Given the centrality of these paths to the model’s objective, we retain the variables, acknowledging that the high VIFs temper the interpretability of the individual path coefficients’ magnitude, but not the overall. Since the measurement model VIFs are acceptable, the constructs are retained to preserve the model’s content validity and theoretical structure [91]. While multicollinearity among indicators is expected and necessary for internal consistency in reflective models, multicollinearity among the latent predictor constructs in the structural model was rigorously checked by assessing the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF). This procedure confirmed the model’s robustness, as all VIF values for the latent predictor constructs were found to be below the critical threshold of 5.0 [94].

Table 8.

Variance Inflation Factors (VIF) for each path.

For the Discriminant Validity, the analysis revealed several Heterotrait–Monotrait Ratios of Correlations (HTMT) in Table 9 and its values exceeding the stringent threshold of 0.85, notably between ATT, PU, PEU, and PBC (up to 0.960). While this suggests a lack of statistical discriminant validity, the high correlation is theoretically justified as the model integrates the TAM and the TPB. In these frameworks, Perceived Usefulness (PU) and Perceived Ease of Use (PEU) are established direct antecedents of Attitude (ATT), making a high degree of shared variance necessary for the theoretical consistency [95]. Second, the study evaluates a hypothetical, non-existent service (smart lockers in Egypt). In pre-adoption contexts, respondents lack empirical experience, leading to the conflation of cognitive belief; they may find it difficult to distinguish between what is useful, easy, and controllable without actual usage history [96].

Table 9.

Discriminant Validity for the constructs.

Therefore, the assessment of Construct Validity followed a two-step process. Convergent Validity was first established, with all constructs exhibiting high loading, AVEs above the 0.5 threshold, and strong Composite Reliability, confirming the internal consistency and reliability of the measurement model. For Discriminant Validity, the HTMT values exceeded the strict 0.85 threshold; this result is theoretically defended as an inevitable empirical consequence of the strong conceptual proximity between the integrated TAM and TPB constructs in a hypothetical, pre-adoption setting [96]. Given the robust evidence for Convergent Validity and the structural stability confirmed by the VIF analysis after model re-specification, the constructs are deemed sufficiently distinct for theoretical testing in this specific context.

The potential for Common Method Variance (CMV) was tested due to the use of self-reported questionnaires. Firstly, Harman’s Single-Factor Test indicated that the first unrotated factor accounted for 59.012% of the total variance, exceeding the 50% threshold commonly used to rule out CMV. However, this test is often criticized for being insensitive [97]. Therefore, a more robust check was performed using the full collinearity VIF assessment in the PLS-SEM framework [98]. All indicators of VIFs were found to be below the 5.0 threshold, confirming that the shared variance did not critically inflate the standard errors or compromise the reliability of the measurement model. Furthermore, this high variance is more accurately interpreted as a general adoption favorability factor, which is an expected theoretical consequence of the intertwined nature of the TAM and TPB beliefs rather than a spurious methodological bias [97].

5.3. Hypotheses Testing

The following Table 10 illustrates the estimated path coefficient and significance level along with the SEM, where the results show the following:

Table 10.

Summary of the Hypotheses Testing.

- H1: Perceived Ease of Use of smart lockers has a positive effect on customers’ attitude. Since the p-value is (0.000), which is less than the sig level of 0.05, and the coefficient value is (0.248), a positive value, the hypothesis path PEU -> ATT will be accepted (Supported).

- H2: Perceived Ease of Use of smart lockers has a positive effect on switching intention. Since the p-value is (0.016), which is less than the sig level of 0.05, and the coefficient value is (0.130), a positive value, the hypothesis path PEU -> SI will be accepted (Supported).

- H3: Perceived Usefulness of using smart lockers has a positive effect on customers’ attitude. Since the p-value is (0.000), which is less than the sig level of 0.05, and the coefficient value is (0.651), a positive value, the hypothesis path PU -> ATT will be accepted (Supported).

- H4: Perceived Usefulness of smart lockers has a positive effect on switching intention. Since the p-value is (0.000), which is less than the sig level of 0.05, and the coefficient value is (0.262), a positive value, the hypothesis path PU -> SI will be accepted (Supported).

- H5: A positive attitude toward smart lockers significantly and positively influences customers’ intention to switch to sustainable last-mile delivery options utilizing smart lockers. Since the p-value is (0.471), which is greater than the sig level of 0.05, and the coefficient value is (0.048), a low positive value, the hypothesis path ATT -> SI will be rejected (Not Supported), and this effect will be statistically negligible.

- H6: The effect of Perceived Ease of Use on switching intention is positively mediated by customers’ attitude. Since the p-value is (0.496), which is greater than the sig level of 0.05, and the coefficient value is (0.012), a low positive value, the hypothesis path PEU -> ATT -> SI will be rejected (Not supported), and this effect will be statistically negligible.

- H7: The effect of Perceived Usefulness on switching intention is positively mediated by customers’ attitude. Since p-value is (0.474), which is greater than the sig level of 0.05, and the coefficient value is (0.032), a low positive value, the hypothesis path PU -> ATT -> SI will be rejected (Not supported), and this effect will be statistically negligible.

- H8: The convenience of smart lockers has a positive effect on customers’ Perceived Behavioral Control. Since the p-value is (0.000), which is less than the sig level of 0.05, and the coefficient value is (0.816), a positive value, the hypothesis path CON -> PBC will be accepted (Supported).

- H9: The convenience of smart lockers has a positive effect on switching intention. Since the p-value is (0.001), which is less than the sig level of 0.05, and (0.198), a positive value, the hypothesis path CON -> SI will be accepted (Supported).

- H10: Privacy positively affects customers’ Perceived Behavioral Control. Since the p-value is (0.015), which is less than the sig level of 0.05, and the coefficient value is (0.086), a positive value, the hypothesis path PRI -> PBC will be accepted (Supported).

- H11: Privacy of smart lockers has a positive effect on switching intention. Since the p-value is (0.001), which is less than the sig level of 0.05, and (0.076), a positive value, the hypothesis path PRI -> SI will be accepted (Supported).

- H12: Perceived Behavioral Control regarding smart lockers significantly and positively influences customers’ intention to switch to sustainable last-mile delivery options that utilize them. Since the p-value is (0.000), which is less than the sig level of 0.05, and the coefficient value is (0.274), a positive value, the hypothesis path PBC -> SI will be accepted (Supported).

- H13: The effect of Convenience on switching intention is positively mediated by customers’ Perceived Behavioral Control. Since p-value is (0.000), which is lower than the sig level of 0.05, and the coefficient value is (0.223), a positive value, the hypothesis path CON -> PBC -> SI will be accepted (supported).

- H14: The effect of Privacy on switching intention is positively mediated by customers’ Perceived Behavioral Control. Since the p-value is (0.058), which is greater than the sig level of 0.05, and the coefficient value is (0.023), a low positive value, the hypothesis path PRI -> PBC -> SI will be rejected (Not supported), and this effect will be statistically negligible.

The evolution of path significance in the structural model was conducted using a two-part approach. Firstly, the significance of all direct path coefficients was primarily assessed using standardized p-values, where a coefficient was deemed significant if p-value is less than 0.05; however, for the more complex task of evaluating indirect effects such as the mediation paths, the study employed the bootstrapping method, which is essential as it does not assume the normal distribution of the indirect effect [99]. The analysis utilized 5000 resamples to generate a stable empirical distribution of the indirect effect, and the significance was confirmed by examining the 95% bias-corrected confidence intervals (CIs), and the mediation was considered statistically significant only if the generated CI did not contain zero, adhering to the robust standards for testing indirect effects [100].

The study addressed the potential influence of confounding variables, specifically demographic factors, to enhance the internal validity of the findings by utilizing statistical controls within the Structural Equation Model (SEM) as mentioned in Table 11 variables such as age (p-value 0.609) and gender (p-value 0.488) were included as covariates predicting the dependent variable, switching intention (SI) [93]. Although the statistical analysis confirmed that the direct effects of both age and gender on switching intention were non-significant, their inclusion was a crucial methodological step. By controlling for these variables, we demonstrated that the predictive power of the core theoretical constructs remained stable and significant, ensuring that the observed structural relationships were not artifacts of uncontrolled demographic variance [81]. This confirmed that the hypothesized relationships are robust and independent of the minor demographic differences within the sample.

Table 11.

Summary of the Hypotheses Testing after adding the controllable variables.

6. Discussion and Analysis

This research hypothesized a framework that was tested through a structured online survey, with the main study of 513 successful responses, and it was found that the results were concentrated on the adult consumers residing in the densely populated urban areas in Egypt, mainly 77% from Alexandria, and 19.4% from Cairo. Additionally, it was concentrated in the most economically active age groups, as 33.5% of the respondents are from 35 to 44 years old, and 24% from 18 to 24 years old. Most of the respondents are employed, with 64.3%, followed by students with 21.6%, and the sample leaned towards females with 59.5%. Confirming that a profile of consumers with busy schedules and a high need for convenient delivery options exists. Additionally, it was highlighted that the sample confirmed the strong e-commerce engagement, as a high proportion of respondents are frequent e-shoppers, with 33.5% placing 3–5 online orders and 27.1% placing 6–10 orders per month. This activity confirms that consumers may routinely encounter the current last-mile logistics challenges. While 59.84% have no failed deliveries, around 40% of the respondents experienced one or more failed attempts from March to August 2025, which illustrates the importance of seeking a more reliable and convenient method, such as smart lockers. Furthermore, the data collected shows a pre-existing openness to unconventional last-mile logistics options, as 58.9% have already tried the in-store pickup option. This confirms its suitability for studying switching intention behavior, specifically, when the preferred e-commerce choices were presented, 61.4% expressed a preference for using smart lockers over traditional home delivery options (4.1%). The descriptive analysis validates that the respondents’ profiles are active and have an experience of urban e-commerce, facing sufficient delivery challenges to motivate a switch. The high concentration of Alexandria’s respondents by 77% suggests that the model’s predictive power accurately reflects consumers within a specific environment whose distinct infrastructural challenges may moderate the strength of certain key paths, such as the relationship between Convenience and Perceived Behavioral Control.

This research was focused on the impact of seven constructs on the customer switching intention towards a sustainable last-mile delivery option, such as smart lockers. The findings of this research will aid companies that are trying to use sustainable technological capabilities in their last-mile logistics activities to mitigate their complex challenges as they can possible.

Therefore, the PLS-SEM analysis of the main paths provides a strongly significant statistical support for most of the proposed relationships and clearly stating the following, that the model’s strength is mainly from the high path coefficient is 0.816 for the path of Convenience to Perceived Behavioral Control (CON → PBC), a strong positive relationship indicating that the “Convenience” variable is the main driver of consumers’ ability to perform a specific behavior, which is, in this model, the (switching intention). Additionally, the key drivers of the Technology Acceptance Model of “Perceived Usefulness” and “Perceived Ease of Use” are the second-highest significant positive effects on “Attitude” with coefficients 0.651 and 0.248, respectively, confirming the crucial role of TAM theory in changing customers’ attitudes. Furthermore, the results determined the significant pathways that directly influence the “switching intention” variable. The strongest effect was from the Perceived Behavioral Control (PBC → SI) with a coefficient value of 0.274, followed by Perceived Usefulness (PU → SI) with a value of 0.262, then the Convenience (CON → SI) with 0.198. This suggests that the customer’s switching intention is primarily derived from the sense of control over the process, the ease of switching, and the benefits of the alternatives. On the other hand, the path from Attitude to switching intention (ATT → SI) resulted in not being statistically significant (with a coefficient value = 0.048 and p-value = 0.471). This finding suggests that while attitude is shaped by its antecedents of Perceived Usefulness and Perceived Ease of Use, its final direct influence on the switching intention is minimal. Therefore, the direct effect of the Convenience, Perceived Behavioral Control, and Perceived Usefulness bypasses the role of the general attitude in driving the switching intention. This finding is considered an indication of the high practical and cognitive hurdles involved in the specific act of switching from conventional to unconventional delivery service in the Egyptian market. Firstly, this finding supports the conceptual distinction between rational and preference behavioral commitment. While the significant paths from Perceived Ease of Use to Attitude and Perceived Usefulness to Attitude confirm that the Egyptian consumers develop a positive affective disposition towards the features of the smart lockers, this emotional preference is insufficient to motivate higher friction behavior of switching their intentions. Therefore, in this context, the consumer’s decision-making to switch bypasses the affective domain and makes the intention driven instead by necessary usefulness and control.

Secondly, the non-availability of the smart lockers in the Egyptian market means that the respondent’s intention remains aspirational, and they are assuming the intention based on a hypothetical future state. Therefore, the non-significant path suggests a high-level gap in the “intention behavior gap” where a positive attitude is not strong enough to overcome the effort and perceived cost required to switch from the established habit.

The direct effect of Perceived Usefulness on switching intention is strongly supported by the realities of the Egyptian last-mile logistics environment. In this context, Perceived Usefulness is assessed based on pain-point elimination and functional risk reduction. As the main challenge in the Egyptian urban context is the severe traffic congestion, the difficulties in locating addresses, and the high rate of failed and missed deliveries make conventional delivery methods more stressful and unreliable. Therefore, the consumer calculates usefulness based on avoiding high-cost negative outcomes such as wasted time, depot pickup, and rescheduled delivery. This strong rational imperative allows the construct of Perceived Usefulness to bypass the weaker affective construct, which is the Attitude.

The significant positive effect of Perceived Behavioral Control on switching intention is the most profound finding that validates the control override hypothesis in this switching intention context [101]. The Perceived Behavioral Control is highly relevant in Egypt as it directly addresses the Egyptian consumer’s lack of control over the existing last-mile logistics processes. The conventional home delivery is inherently low control, as the consumer must wait for the courier. The strong path of Perceived Behavioral Control indicates that the consumer prioritizes perceived capabilities and resources to manage the new behavior, including geographical control in the ability to access the lockers at convenient locations and the assurance of anytime access to mitigate the risk of missed deliveries. This validates that the consumers will be able to switch when they are highly confident that the new conventional methods will provide them with superior control and will eliminate the uncertainty associated with the current delivery methods.