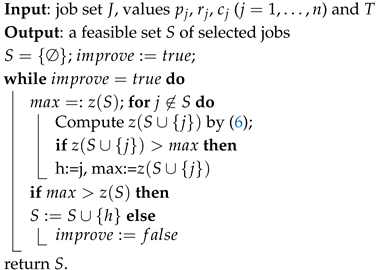

In this section, we address the complexity of various cases of UIMSP and UIMSPS when failures follow a linear risk model. Under this model, a time horizon

T is specified, and the failure probability is

uniformly distributed across

T. Hence, the probability that a machine is still working at time

, which can be called

, is given by

3.1. UIMSP(1)

Let us start from the simplest problem, i.e., there is a single machine and there are no selection costs. In what follows, we consider the case when T is nonbinding.

Given a schedule

, let

denote the job in the

i-th position. So, the first scheduled job is

, of length

and reward

. Due to (

1), the expected reward stemming from the execution of the first scheduled job is given by

The reward of

is attained if the machine does not fail within time

; hence, its contribution to the expected reward is

and so on. Given a schedule

, the expected reward

of the schedule

is therefore given by

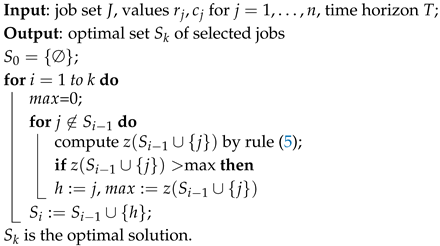

Example 1. Consider the example in Table 1, where . Figure 1a shows the probability that the machine is still working at time t. Starting from 1, linearly decreases, becoming 0 at time . Figure 1b illustrates a feasible schedule . Under this schedule, the probability of successfully carrying out job 2 is ; hence, the expected reward from scheduling job 2 is . The probability of successfully carrying out job 3 is , and therefore, job 3 contributes by . A similar computation for job 1 yields ; hence, the total expected reward of this schedule is . We next show that UIMSP(1) can be efficiently solved when

T is nonbinding. From (

2), we have

Since the first term of the above expression is a constant, the expected reward

is maximized when

is minimized. Now consider the classical scheduling problem

, consisting of minimizing the total weighted completion time of

n jobs, with each having a processing time

and a weight

. If we let

, observing that

is the completion time of the job in the

i-th position, (

4) coincides with the value of the total weighted completion time of a given schedule. As a consequence, (

4) is minimized by sequencing the jobs according to Smith’s rule [

15], i.e., by nondecreasing order of the ratios

Theorem 1. When , UIMSP under linear risk is solved in .

Note that the ordering rule is fairly intuitive, in that it gives precedence to jobs with a small processing time and a large reward.

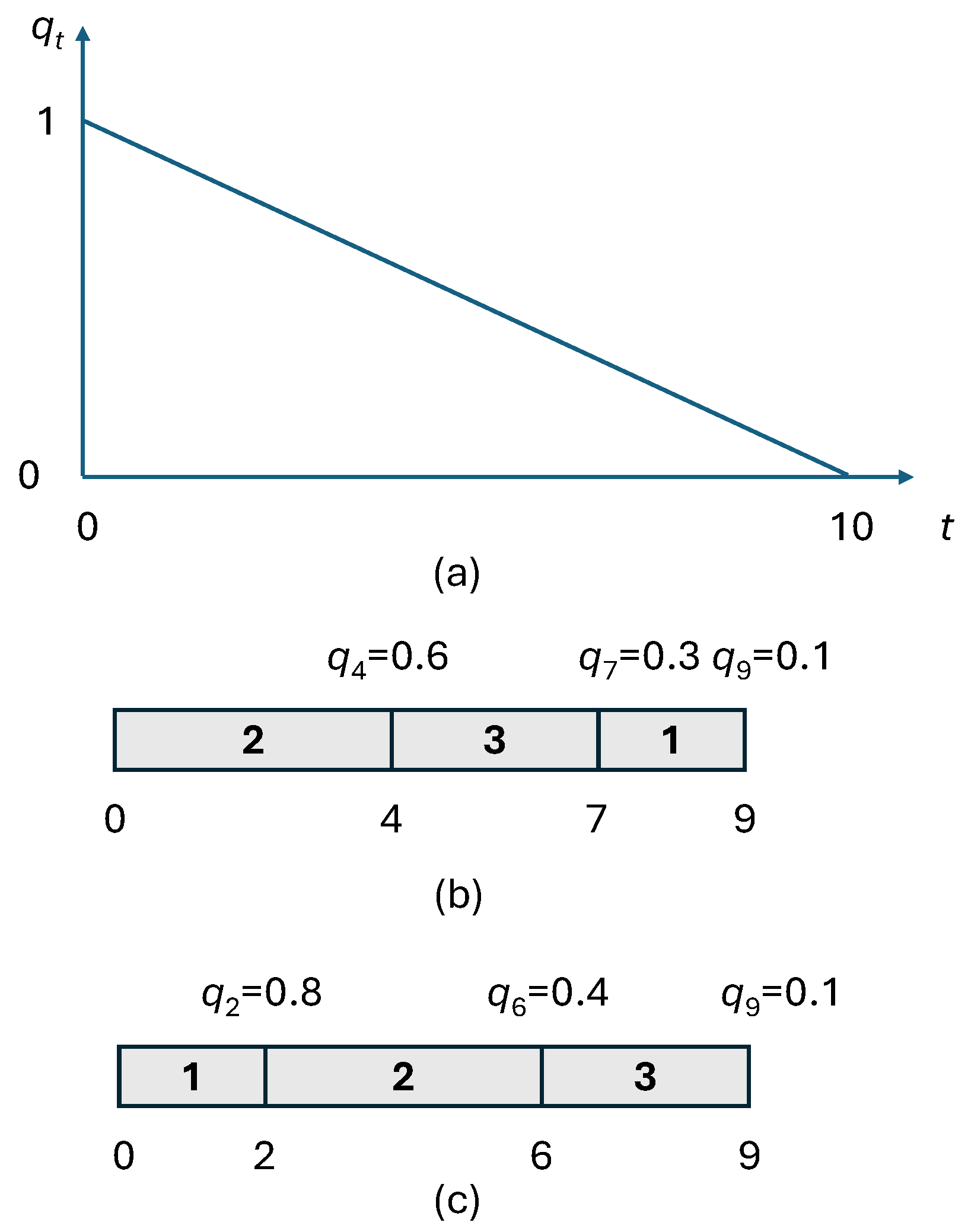

Example 2. By sequencing the jobs of Example 1 by increasing ratios , one obtains the schedule in Figure 1c, i.e., schedule . This is the optimal schedule, and its value is given by . Finally, we observe that, if T is binding (i.e., ), the nature of the problem changes significantly, since no jobs can complete after T. Thus, the problem becomes deciding which jobs should be completed before T, and UIMSP(1) becomes equivalent to UIMSPS(1) with no costs. The complexity of UIMSP(1) in this case is still open.

3.2. UIMSPS(1) and UIMSPSk(1)

In this section, we address the problem with selection costs; i.e., each job

j also has a cost

that is paid if the job is selected for processing. Notice that, once a subset

of jobs is selected to be performed within

T, the optimal sequence is obtained by ordering the jobs according to (

5). Hence, UIMSPS(1) essentially consists of finding

S. In what follows, we denote by

the value of the net expected reward when

S is selected, i.e., from (

2):

We next propose a dynamic programming algorithm for solving UIMSPS(1). In what follows, we assume that the jobs are numbered by

nondecreasing values of the ratio (

5). For a given positive integer

, let

denote the subproblem restricted to jobs

, under the condition that the last selected job completes exactly at time

B. We denote by

the value of the optimal solution of

. It is possible to express

by means of the following recursive formula:

The first term corresponds to the case in which

j is

not selected in the optimal solution of

. The second term corresponds to selecting

j, in which case job

j is appended at the end of the optimal solution of

, and the contribution of job

j is accounted for. The value of the optimal solution of UIMSPS(1) is given by

The correctness of the algorithm is derived from the following considerations. Suppose that, for some

, in the optimal solution of

, there is some idle time of length

between two consecutive jobs (which is possible, to meet the constraint that the last job precisely completes at

B). By eliminating such an idle time, we obtain a schedule that is feasible for the subproblem

and has a strictly larger net expected reward. Hence, as we consider all values of

B in (

8), the makespan

of the optimal solution to UIMSPS(1) is also included.

Formula (

7) must be suitably initialized, as follows:

In conclusion, the following result holds.

Theorem 2. UIMSPS(1) can be solved in time.

Proof. Formula (

7) has to be computed for each value of

i and

B. As each

is simply obtained by comparing two terms, it can be computed in constant time, and the thesis follows. □

In

Section 4, we report the results of some computational experiments about the viability of the above dynamic programming approach. Notice that, although the complexity of UIMSPS(1) is open, the result of Theorem 2 rules out the strong NP-hardness of UIMSPS(1).

Concerning UIMSPS(1), as its complexity is open, a relevant issue is to figure out whether it could be solved by a greedy approach. A greedy algorithm in this context simply consists of iteratively adding to the set of selected jobs a new job that maximizes the improvement of the objective function (see Algorithm 1). The algorithm stops when no other jobs can be added to the current set, either because the time horizon would be violated or because any additions would only decrease the value of the objective function. In this algorithm,

denotes the total processing time of a set

S of jobs.

| Algorithm 1: Greedy algorithm for UIMSPS(1) |

![Logistics 09 00157 i001 Logistics 09 00157 i001]() |

The following example shows that the greedy algorithm may not return the optimal solution.

Example 3. Consider an instance of UIMSPS(1) with the data in Table 2, and the time horizon is . Jobs are numbered according to (5). The greedy algorithm starts by considering singletons, as follows: , , and . Among these options, the best is , so job 2 is added to S. Next, we observe that all sets with two jobs have a total length smaller than T. Hence, the next step of the greedy algorithm compares sets and , yielding and . As , job 1 is added to S. Since , the set cannot be considered, and in conclusion, the greedy algorithm returns set . However, it is easy to check that the optimal solution is , as . We next address UIMSPSk, i.e., the case in which . To establish the complexity of the problem, we first express UIMSPSk(1) in decision form:

UIMSPS

k(1)_

dec.

A set J of jobs is given. Each job has a processing time , a reward , and a cost , . Given an integer T, and the linear risk functionis there a subset S of k jobs such that, when selected and scheduled on the machine, the net expected reward is at least R?In the proof, we use the following well-known NP-complete problem:

E

qual-size partition.

Given a set of positive integers, (n even), such that , is there an equal-size partition, i.e., a partition of N, such that andTheorem 3. UIMSPSk(1)_dec is NP-complete.

Proof. Clearly, UIMSPS

k(1)_

dec is in NP. Consider an instance of an

equal-size partition with

n integers, in which we denote as

the smallest integer in

N. We define an instance of UIMSPS(1)_

dec as follows. There are

jobs, corresponding to the integers of the

equal-size partition, and we let

. The processing times and the rewards of the jobs are defined as

Note that, since

for all jobs, the order in which the selected jobs are sequenced is immaterial. The time horizon

T is defined as

For all

, let

where

K is a suitable integer defined later on. We want to establish if there is a subset

S of

jobs yielding a net expected profit of at least

Consider a subset

S of jobs. For the sake of simplicity, let us number the selected jobs with

. The corresponding value

z of the net expected reward is, from (

2),

Since, given

integers

,

we can rewrite (

14) as

and, from (

11),

Now observe that the term

is a constant, as it does not depend on which jobs are selected. Hence, the problem is to select

jobs so that the target value

R specified in (

12) is met. Considering the function

we can rewrite the net expected reward (

18) as

We observe that

is maximized by

, and the maximum value is

. This means that, if there is a set

S of

jobs such that

then (

18) is the maximum, attaining the value

Therefore, we can conclude that a selection

S of

jobs achieving the net expected profit of

R exists if, and only if, there are

jobs such that

i.e., if, and only if,

which holds if, and only if, the instance of UIMSPS

k(1)_

dec is a yes-instance.

We are only left with showing that a suitable value of

K exists. Since the costs

must be positive, from (

11), it must hold that, for all

,

On the other hand, it must also hold that

for all

i; hence,

Since

, (

20) holds for all

. Moreover, recalling the definition of

T (

10), we can write

since, obviously,

, and from (

9),

for all

j; thus, one has

Also, (

21) is fulfilled for all

. Finally, as

, we observe that the number of bits necessary to encode

K does not exceed

, hence resulting in a polynomial in the input size of the

equal-size partition. □

3.2.1. UIMSPSk(1) with Identical Rewards

We next consider the special case of UIMSPSk in which all jobs have the same reward, i.e., for all . In this case, the selected jobs are simply sequenced by nondecreasing processing times (SPT rule). We show that this problem can be solved in polynomial time.

Given a set

S, let us denote the

k selected jobs as

, and suppose they are numbered by nondecreasing processing times. Then, the value of the objective function is

As

k is fixed, the objective of maximizing

is therefore equivalent to that of minimizing the following function

:

From this expression, if a job

j is selected and assigned to position

h, its contribution to

is given by

Suppose now that the jobs are numbered by nondecreasing processing times. UIMSPS

k is equivalent to the following assignment problem, in which

if job

j is assigned to position

h:

where

The correctness of Formulation (24) is derived from the fact that exactly

k jobs are selected, as implied by the

k assignment constraints (

24b). Given an optimal solution

of (

24a)–(

24d), the optimal set

of selected jobs is given by

Notice that the second case in (

25) is derived from the observation that we can assume that a job

j will not occupy a position

h larger than

j. Suppose, in fact, that

and

j is assigned position

. Hence, some other job

such that

is assigned a position

. By switching positions between jobs

j and

u, it is easy to check that

decreases in the amount of

, which is always nonnegative. We can therefore conclude the following:

Theorem 4. UIMSPSk(1), when , can be solved in .

If we solve UIMSPS

k(1) for all values

, we obtain

n optimal subsets,

. Clearly, the optimal solution to UIMSPS(1) (without a cardinality constraint on

S) is

so we obtain the following result.

Theorem 5. UIMSPS(1), when , can be solved in .

3.2.2. UIMSPSk(1) with Unit-Processing Times

Let us now consider another special case, namely when

for all

j, and we must select

k jobs. Since, in this case, the jobs have identical processing times, from (

5), the selected jobs will be sequenced by nonincreasing rewards. Moreover, we obviously assume that

, as otherwise, the problem would be infeasible.

As before, consider a set

S of

k selected jobs, denoted as

, and suppose they are numbered by nonincreasing rewards. The value of the objective function is

Hence, if job

i is selected and assigned to position

j, its contribution to the objective function is

Therefore, this special case of UIMSPSk can also be solved through an assignment problem. However, in this case, it is easy to see that the problem can be solved more efficiently, taking advantage of the following property.

Theorem 6. Given an instance of UIMSPS in which all jobs have the same processing time , let be the optimal set of UIMSPSk−1. There exists an optimal set for UIMSPSk that includes ().

Proof. The proof is by induction on

k. Consider

, i.e., set

. In this case, the selected job

h is such that

Now suppose that the set

does not include

h, but it includes jobs

i and

j, so that

If, in

, we replace

i with

h, we obtain set

such that

From (

27),

; hence,

is optimal and the thesis holds.

Now let us consider a generic value of k, and from the inductive hypothesis, the thesis holds for all of the following problems: UIMSPS1, UIMSPS2, …, up to UIMSPSk−1.

Let

denote the optimal schedule for

, and, in such a schedule, let

q be the

rightmost job in

such that

and

; additionally, consider the set

. If

, we are finished. Otherwise, let

u be the position occupied by

q in the optimal schedule

for

. Since

q is the rightmost “new” job, only jobs of

appear at the right of

q (possibly none). Now, we can view

as obtained by inserting

q in position

u in the schedule, which can be called

, for the set

.

R denotes the total reward of the

jobs occupying the positions

in

. When we insert

q in position

u in

, each of the last

jobs moves rightwards by one position, so their total contribution to the expected reward decreases by

. So, when inserting

q in

, the expected

marginal reward is

Now consider the optimal schedule

for

, and a new schedule

obtained from

by adding

q in position

u in

. Since we are inserting

q in position

u, its contribution to the increase in the expected reward is

, as in (

28). Now, letting

denote the total reward of the jobs occupying the last

positions in

, as each of these jobs moves rightward by one position, going from

to

, their contribution to the total reward decreases by

. The key observation is that

is certainly not greater than the total reward

R of the jobs

belonging to , which occupy the last

positions in

. This is because the jobs occupying the last

positions in

are precisely the

jobs with the smallest rewards in

. As a consequence, when inserting

q in

, the expected marginal reward is

Since

, the marginal expected reward from adding

q to

(given by (

29)) is not smaller than that attained from adding

q to

(given by (

28)). But since, from the inductive hypothesis,

is optimal for UIMSPS

k−1,

, one has from (

28) and (

29) that

Hence, adding q in position u to yields a schedule that is not worse than , so is optimal and the thesis holds. □

Theorem 6 allows a very simple greedy algorithm to be devised for UIMSPS

k when

(Algorithm 2). Starting from an empty set

S, at each step, the job that increases the net expected reward by the most is added to

S, until the size

k is reached.

| Algorithm 2: Greedy algorithm for UIMSPSk when |

![Logistics 09 00157 i002 Logistics 09 00157 i002]() |

Let us now consider the complexity. Suppose that we maintain a vector

containing the total reward of the jobs occupying positions from

u to the end of the schedule, i.e., to position

i. For each value of

i, we must select the job

q that maximizes the marginal reward. For each job

, its optimal position can be found in

and the marginal reward computed in constant time through (

29). Once the job

q is found and its position

in the schedule is determined, we must update the vector

for all positions

u preceding

, which takes

. As there are

k steps, the following result holds.

Theorem 7. When for all j, UIMPSPk can be solved in .

By solving for all values of k from 1 to n, the optimal value for UIMSPS is given by , so we obtain the following result:

Theorem 8. When for all j, UIMPSP can be solved in .

3.2.3. UIMSPSk(1) with Identical Selection Costs

Finally, let us consider the special case of UIMSPS

k(1) in which all jobs have the same cost, i.e.,

for all

j. In this case, the total cost is

independent of

S; hence, the problem is to select exactly

k jobs so that the expected reward is maximized. In view of (

4), and identifying the rewards

with job weights, the problem is equivalent to that of selecting

k jobs so that the value of their total weighted completion time is minimized. In turn, this can be shown to be equivalent to the special case of the classical job rejection problem, in which, given

n jobs,

jobs can be rejected, so that the total weighted completion time of the selected jobs is minimized. The complexity of this problem is currently open [

16,

17].

3.3. UIMSP(m)

Let us now consider UIMSP with two parallel machines (UIMSP(2)). The time horizon T is supposed to be the same for both machines and nonbinding. Consider the following NP-complete problem in decision form:

. A set J of jobs is given, with two identical machines and a value F. Each job has a processing time and a weight . Is there a schedule for the jobs on the two machines such that their total weighted completion time does not exceed F?

We next prove the NP-completeness of UIMSP(2) in decision form, as follows.

UIMSP(2)_

dec.

A set J of jobs is given with two machines, each of which has the linear risk function Each job has a processing time and a reward , . Is there a schedule of the jobs on the two machines such that the expected reward is at least R?Theorem 9. UIMSP(2)_dec is NP-complete.

Proof. Obviously, UIMSP(2)_

dec is in NP. Consider an instance of

, with

jobs and with job

i having a processing time

and a weight

, for

and a threshold value

F. We define an instance of UIMSP(2)_

dec as follows. There are

jobs, with job

i having a processing time

and a reward

. The time horizon is defined as

, which is nonbinding. Then, we let

. Consider now a schedule

for UIMSP(2)_

dec, and let

and

denote the jobs assigned to

and

, respectively, in

. Denoting with

the sum of the processing times of the jobs preceding

j (including

j) on the respective machine, the expected reward of

is given by

Hence, one can determine that there exists a schedule

with an expected reward of at least

R if, and only if,

Since

and the processing times in the two problems are identical, (

31) holds if, and only if,

□

Consider now the special case in which the jobs have the same reward, for all i. In this case, UIMSP(m) can be efficiently solved.

Theorem 10. If for all j,

UIMSP(m)

can be solved in .

Proof. Given a feasible schedule for UIMSP(

m), let

denote the subsets of jobs assigned to machines

, respectively (

), and let

denote the job in position

i on machine

. From (

3), we can rewrite the expected reward as

Now observe that maximizing (

32) is equivalent to minimizing the rightmost term, i.e., the total completion time of all jobs. Hence, the problem is equivalent to an instance of

, which is solved by ordering the jobs in SPT order and assigning them in this order to the machines, in a round-robin fashion. The complexity is therefore given by the sorting step,

. □

3.4. UIMSPS(2) and UIMSPSk(2) with Identical Rewards or Identical Processing Times

In the general case, as UIMSP(2) is NP-hard, so too is UIMSPS(2). We next focus on the special cases of UIMSPSk(2) in which either for all , or for all , when T is nonbinding. Both of these cases can be reduced to the assignment problem.

If

for all

, recalling that we want to

minimize (given in (

22)), from (

23), one has that, if a job

j is assigned position

h on machine

and a total of

jobs are assigned to

, the contribution to the objective function

of job

j is

while, if

for all

, and recalling that we want to

maximize , if

j is assigned position

h on machine

, it completes at time

, so its contribution to the objective function

is given by

Now, consider UIMSPS

k1,k2(2) in which

jobs must be assigned to

and

jobs to

. If we let

and if

j is assigned position

h on

, the problem is solved through the following assignment problem:

where

for all

j, and it is assumed that the jobs are numbered by nondecreasing processing times:

If

for all

j, assuming that the jobs are numbered by nonincreasing rewards, and recalling that we want to

maximize ,

Note that, in both cases, j cannot be assigned a position h larger than j (on any machine).

Now, denoting by

the optimal set of selected jobs for UIMSPS

k1,k2(2) and denoting by

the corresponding net expected reward, the optimal set

for UIMSPS

k(2) is given by

Since the value can be chosen in k different ways (we can rule out ), the following result holds:

Theorem 11. When for all j, or when for all j, and T is nonbinding, UIMSPSk(2) can be solved in .

Notice that the same reasoning can be extended to UIMSPSk(m), fixing in all possible ways the number of jobs to be assigned to each machine and showing that, in these two special cases, for fixed m, UIMSPSk(m) is polynomially solvable.

Theorem 12. When for all j, or when for all j, T is nonbinding, and m is fixed, UIMSPSk(m) can be solved in .

The complexity of UIMSPSk(m) when m is not fixed is open.

Complexity results are summarized in

Table 3 for UIMSP and in

Table 4 for UIMSPS and UIMSPS

k.