Abstract

This study investigated the effects of three cooking methods—fragmenting process (FP), boiling treatment (BT), and high-pressure steam (HPS) treatment—on the structure and volatile compounds (VOCs) of fresh Lyophyllum decastes. The surface morphology and functional groups of L. decastes were analyzed by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), respectively. The VOCs in L. decastes were analyzed by comprehensive two-dimensional gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC×GC-MS) and gas chromatography–ion mobility spectrometry (GC-IMS). SEM results showed that HPS resulted in the most pronounced structural disruption, forming a honeycomb-like porous surface, whereas FP yielded smaller fragments with smoother surfaces. FTIR spectra indicated that none of the treatments significantly altered the characteristic functional groups. A total of 73 VOCs were identified by GC×GC-MS, including 23 hydrocarbons, 14 alcohols, 10 ketones, seven aldehydes, six ethers, three esters, two terpenes, and eight other compounds. Additionally, 22 VOCs were identified by GC-IMS, including seven alcohols, six aldehydes, five esters, three ketones, and one other compound. The four compounds benzaldehyde, benzeneacetaldehyde, (E)-2-hexen-1-ol, and 1-hexanal were detected by both methods. Among the three methods, FP induced the least structural damage and better preserved the VOCs. These results offer theoretical insights and technical support for the flavor-oriented deep processing of L. decastes.

1. Introduction

Lyophyllum decastes, a species within the Basidiomycetes class, Agaricales order, and Tricholomaceae family, is a rare edible mushroom prized for its high nutritional value and distinctive flavor. In its dried form, it contains 18.2% to 23.5% protein, including all eight essential amino acids. Notably, umami amino acids such as glutamic acid and aspartic acid constitute over 40% of the total amino acid content []. The polysaccharide content ranges from 6.8% to 10.3%, and these compounds exhibit multiple biological activities, including antioxidant, hypoglycemic, anti-inflammatory, and anti-cancer properties [], thus exhibiting broad application prospects in functional foods and flavor-enhanced products.

In recent years, research on L. decastes has mainly focused on genome sequencing [], polysaccharide extraction [,], and nutrient composition determination []. However, there is a paucity of research on the deep processing of L. decastes-derived products. Fresh L. decastes is highly perishable owing to its high moisture content (approximately 89% wet basis) [], which readily induces quality deterioration. This necessitates the application of deep processing technologies to extend its shelf life while retaining its characteristic flavor, which is crucial for the development of the L. decastes product industry.

Numerous studies have confirmed that processing can regulate the composition and content of volatile compounds in edible mushrooms while also extending their shelf life and facilitating transportation and storage. For example, Yang et al. found that 57 volatile compounds (VOCs) could be identified in L. decastes treated with different drying methods, and the composition of flavor compounds changed significantly after drying []. Meanwhile, drying effectively resolves the perishability of L. decastes caused by high water content, facilitating its transportation. Additionally, this regulatory effect of processing on volatile compounds has been extensively verified in various other common edible mushrooms, such as Agaricus bisporus [], Lentinula edodes [], and Lanmaoa asiatica [], further supporting the universality of processing-induced flavor modulation in edible mushrooms. However, research on fresh L. decastes processing has rarely been reported.

In the food processing industry, high-pressure steam (HPS), fragmenting process (FP), and boiling treatment (BT) are three widely used technologies. Their regulatory mechanisms on food quality are distinct: High-pressure steam loosens the cell-wall polysaccharide network through the synergistic effect of high temperature and pressure. For instance, a study on the stipe of Flammulina velutipes demonstrated that the steam explosion effect induced by high pressure can disrupt the dense cell structure, significantly increasing internal porosity and surface roughness, thereby promoting polysaccharide dissolution []. Additionally, it can alter component transformation pathways by regulating enzyme activity—high-pressure cooking can significantly enhance the antioxidant capacity of edible mushrooms [], while in pork, lipoxygenase (LOX) can be completely inactivated at 50 °C and 600 MPa [], a result that highlights the inhibitory effect of high pressure on biological enzymes. Fragmenting process (FP), on the other hand, destroys cell integrity, bringing intracellular enzymes, which were originally spatially separated, into full contact with their substrates. Grosshauser confirmed in a study on Agaricus bisporus that the enzyme systems within the tissue can efficiently promote the synthesis of characteristic flavor compounds such as 3-methylbutanal and phenylacetaldehyde after fresh-cut processing []. Boiling treatment (BT), however, tends to cause the evaporation of low-boiling-point VOCs; for example, the contents of alcohols in Agaricus bisporus and terpenoids in Pleurotus ostreatus both showed a significant downward trend after boiling []. If these three methods are adopted for the cooking of fresh L. decastes, it will not only simplify the processing procedure but also maximize the retention of its texture characteristics, which is of great practical significance for the industrial development of L. decastes deep-processed products.

The accurate characterization of VOCs in L. decastes products relies on efficient analytical techniques. Among these, comprehensive two-dimensional gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC×GC-MS) and gas chromatography–ion mobility spectrometry (GC-IMS) have emerged as important technical tools in the field of flavor research, leveraging their complementary advantages. GC×GC offers a significantly greater peak capacity than conventional GC, thereby enabling effective differentiation of structural isomers []. For instance, Tian et al. successfully identified 79 VOCs in the fermented grains of Qingxiangxing Baijiu using this technique []. Zhou et al. combined GC-IMS and GC×GC-TOF-MS to identify 183 and 245 VOCs, respectively, in Morchella esculenta, fully validating the complementarity of these two techniques in flavor analysis [].

Until now, these techniques have not been jointly applied to the study of VOCs in processed products of L. decastes, nor has any research systematically elucidated the effects of the aforementioned cooking methods on its characteristic VOCs. Therefore, this study aims to integrate GC×GC-MS and GC-IMS to investigate the effects of three processing methods—fragmenting process (FP), boiling treatment (BT), and high-pressure steam (HPS) treatment—on VOCs in fresh L. decastes. Meanwhile, scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) were used to characterize the potential effects of these cooking methods on the structure of L. decastes. Through this systematic research, this study intends to fill the existing research gap in the deep processing field of fresh L. decastes and provide theoretical support for the development of subsequent L. decastes deep-processed products (e.g., L. decastes biscuits, L. decastes steamed breads, L. decastes canned products, etc.).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Raw Material and Processing

All the fresh L. decastes used in this study were purchased from Jiangsu Gubentang Biotechnology Co., Ltd (Jiangsu Province, China). The fresh L. decastes were chilled at 4 °C after harvesting and transported under a temperature-controlled cold chain. Subsequently, 100 g of fresh L. decastes fruiting bodies was cut into 1 cm segments. The segments were then mixed with 500 g of ultrapure water and processed according to the procedure outlined in Table 1. Upon completion of the treatment, the samples were naturally cooled to room temperature.

Table 1.

Specific parameters for the processing of fresh L. decastes fruiting bodies.

2.2. Observation of Surface Morphology in L. decastes by SEM

The SEM procedure was conducted in accordance with the methods described by Nie [] and Zhao et al. []. L. decastes samples treated with three different cooking methods were stored in a −80 °C freezer for 12 h, followed by freeze-drying using an LGJ-2A freeze-dryer (Beijing SihuanQihang Technology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China) under a cold-trap temperature of −40 °C and a vacuum pressure < 50 Pa. The dried samples were then cut into uniform slices measuring 5 mm × 5 mm × 10 mm and mounted onto the sample stage using conductive adhesive, with the outer surfaces of both the cap and stalk oriented upward. Subsequently, the samples were coated with a thin layer of gold for 30 s. Morphological observations were performed using an SU8600 scanning electron microscope (Hitachi High-Tech, Tokyo Metropolis, Japan) at an accelerating voltage of 5 kV under high-vacuum conditions.

2.3. Analysis of Functional Group Structure in L. decastes by FTIR

Freeze-dried samples of L. decastes—prepared using three different distinct cooking methods—were ground into a fine powder. The freeze-drying procedure adhered to the protocol outlined in Section 2.2. FTIR analysis was conducted in accordance with the methodology established by Ma et al. []. The freeze-dried samples were finely ground using a mortar and pestle. A suitable quantity of the resultant powder was then mixed with KBr, further ground, and compressed into pellets. The prepared pellets were analyzed with a Spotlight 200i Fourier transform infrared spectrometer (PerkinElmer, MA, USA) over a wavelength range of 4000–400 cm−1.

2.4. Analysis of Volatile Compounds in L. decastes by GC×GC-MS

Take 2.0 g of the sample and put it into a 20 mL headspace vial, then seal it with a lid. All samples were analyzed by GCMS-QP2020NX gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (Hitachi High-Tech, Japan), and the analysis method referred to that of Cheng et al. []. Maintain a constant temperature at 60 °C for 30 min. Insert the pretreated 2.2 cm extraction head (65 µm PDMS-DVB, Hitachi High-Tech, Tokyo, Japan) into the headspace vial for extraction for 20 min. Insert the optical fiber into the GC injection port at 250 °C through the splitless mode for desorption for 5 min. Determination conditions of GC×GC-MS: First-dimension chromatographic column is SH-Rtx-5sil MS (30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 µm, Hitachi High-Tech, Japan). Two-dimensional chromatographic column is BPX-50 (3.5 m × 0.10 mm × 0.10 µm, SGE, Victoria, Australia). The carrier gas is He (purity 99.999%), with a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min. The temperature program for the first one-dimensional column: The initial temperature is 40 °C, maintained for 5 min, then increased to 230 °C at a rate of 3 °C/min, and maintained for 5 min. Mass spectrometry conditions: electronic ionization (EI) source, ion source temperature 230 °C, mass spectrometry electron energy 70 eV, collection mass spectrometry scanning range 35–400 m/z. The identification of VOCs is determined by comparing mass spectrometry with standard compounds using the NIST mass spectrometry library (NIST 17).

2.5. Analysis of Volatile Compounds in L. decastes by GC-IMS

We took 2.0 g of the sample and placed it in a 20 mL headspace vial, then sealed it with a magnetic cap before analysis. We used HS-GC-IMS (flavor Spec®, Gesellschaft für Analytische Sensorsysteme mbH, Dortmund, Germany) based on 490 Micro Gas Chromatograph (Agilent, CA, USA), equipped with an automatic sampler (Solid Phase Micro Extraction, 57,330 U, Supelco, PA, USA) and headspace sampling device. Subsequently, the samples were incubated at 80 °C for 15 min at a rotational speed of 500 rpm/min. After incubation, 500 µL of headspace gas was automatically injected into the syringe at 65 °C through the injection needle (in non-fractionation mode). The sample was moved into the MXT-5 (15 m × 0.53 mm × 1 µm) metal capillary gas chromatography column by high-purity nitrogen (99.999%) as shown below: the initial flow rate was 2 mL/min, maintained for 2 min, and the flow rate was uniformly increased to 100 mL/min within 18 min and maintained for 30 min. Under a drift gas of 150 mL/min (nitrogen, 99.99% purity), the ions of analytes ionised were directed to the drift tube at 45 ◦C. The VOCs were identified by using Vocal software (version 0.4.03, G.A.S. Dortmund, Germany). The database of NIST14 DB-5/HP-5 in Germany was used to identify VOCs. The unknown is characterized by the RI value and drift time. C4–C9 ketone (Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) is an external standard used for calculating the RI value of VOCs [].

2.6. Statistical Analysis

All experiments were performed in triplicate, and data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 27.0.1 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Differences among the groups were considered significant at p < 0.05. The Venn diagram was created at https://www.omicstudio.cn/tool (accessed on 6 November 2025). The other results were visualized and analyzed using origin 2024 (Origin Lab, Northampton, MA, USA).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. The Surface Morphology of Fresh L. decastes Cooked by Three Different Methods

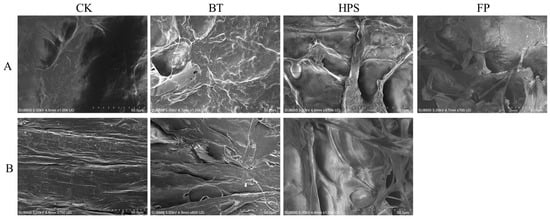

In this study, we observed the microstructures of the caps and stalk of L. decastes cooked by three different methods (Figure 1). The results showed that different cooking methods had a significant impact on the microstructure of L. decastes. The surface of the CK cap is smooth with few wrinkles, the stalk tissue structure is dense, and the fibers are evenly distributed. FP completely destroyed the cap and stalk structure, forming a large number of irregular fragments with diameters ranging from 50 to 200 µm. This treatment exposed numerous fresh fracture surfaces, significantly increasing the specific surface area, and some pore structures could be observed on the fragments. BT caused wrinkles on the surface of the cap, blurred pore edges, and caused a reduction in diameter to 3–5 µm. The fibrous structure on the stalk surface contracted due to thermal denaturation, and the spacing decreased. HPS caused the cap surface to present a unique honeycomb-like porous structure with pore diameters ranging from 20 to 50 µm. The edges were irregular and interconnected, forming a network similar to a “sponge-like” structure, and caused cracks about 100 to 200 µm deep to appear on the stem surface.

Figure 1.

The effects of three different cooking methods on the surface morphology of fresh L. decastes. Cap of fruiting bodies (A). Stalk of fruiting bodies (B). The FP group was a mixture of cap and stalk fragmentation.

These dramatic changes in the HPS group are likely attributable to the rapid expansion of steam under high temperature and pressure, generating substantial shear forces that irreversibly damage cell membrane integrity, break fibers, and create pores, thereby completely disrupting the dense native structure [,]. The observed structural alterations align with findings from studies on other vegetables, such as carrots, where steaming and boiling also led to cell dehydration and tissue separation, potentially due to capillary shrinkage stress caused by water evaporation during cooking [].

3.2. FTIR Analysis of Fresh L. decastes Cooked by Three Different Methods

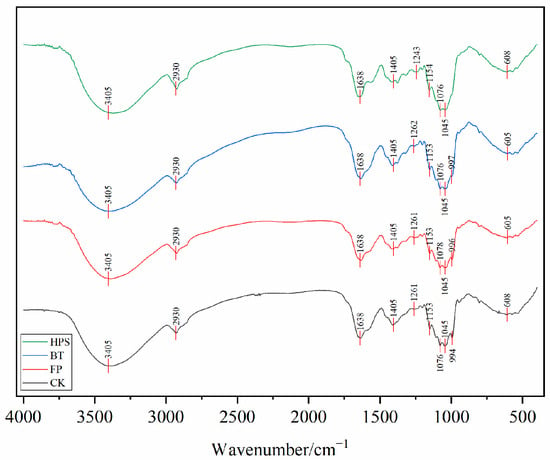

FTIR analysis (400–4000 cm−1) confirmed that the infrared spectra of fresh L. decastes treated by FP, BT, and HPS were consistent with CK (Figure 2). This indicates that none of the three treatments altered the characteristic functional groups of L. decastes. A broad and intense peak appeared at 3405 cm−1, corresponding to the stretching vibration of O-H bonds. This suggests strong intermolecular and intramolecular interactions between polysaccharide chains and phenolic compounds []. A narrow and weak peak near 2930 cm−1 was attributed to the stretching vibration of C-H bonds [], mainly derived from lipids and polysaccharides. The sharp absorption peaks in the range of 1760–1600 cm−1 belonged to the stretching vibration of C=O in carbonyl compounds, which may be associated with the high content of ketone compounds [] or proteins in the samples—consistent with the high protein content of L. decastes []. The peak around 1260 cm−1 was attributed to C–O stretching in acetyl groups or other related compounds. The significant absorption at 1150–1030 cm−1 corresponded to the stretching of C-O and C-C bonds or the bending of C-OH groups [,], mainly originating from cell-wall chitin and polysaccharides. The peaks in the range of 350–600 cm−1 corresponded to the skeletal ring vibration of pyranose []. These results indicate that L. decastes is mainly composed of polysaccharides, proteins, lipids, and chitin.

Figure 2.

FTIR spectra of fresh L. decastes cooked three different ways.

Further analysis of the peak intensity of the infrared spectral curves revealed that different treatment methods exerted varying degrees of influence on the chemical structure of L. decastes. The CK exhibited a distinct broad peak at 3400 cm−1, indicating a high content of hydroxyl groups and an intact structure. The characteristic peaks of polysaccharides in the 1150–1030 cm−1 region were clear, demonstrating that the polysaccharide structure remained undamaged. The obvious absorption peak of β-glycosidic bonds at 608 cm−1 suggested the integrity of the chitin structure. FP caused a significant reduction in the intensity of the infrared absorption peak at 605 cm−1. This might be attributed to the mechanical shear force breaking the β-glycosidic bonds, leading to the collapse of the pyranose ring skeleton structure. For the BT, the absorption intensity at 3400 cm−1 slightly decreased, which could be related to the dissolution of some soluble polysaccharides or proteins. In the HPS, the peak intensity at 3405 cm−1 significantly increased with a narrowed peak shape, and the content of free hydroxyl groups rose. This indicated that high temperature and high pressure might have caused the breakage of some hydroxyl groups or the loss of moisture. The decreased absorption peak intensity in the 1150–1030 cm−1 region might result from changes in the content and structural morphology of chitin under high temperature and high pressure []. The weakened peak at 608 cm−1 suggested the possible partial degradation of β-glycosidic bonds.

These changes in peak intensity indicated that FP had a minor impact on the structure, mainly causing physical damage. BT exerted a slight effect on the protein structure, while the polysaccharide structure remained relatively stable. HPS treatment significantly affected both protein and polysaccharide structures, potentially leading to the partial degradation of cell-wall chitin.

3.3. GC×GC-MS Analysis of Fresh L. decastes Cooked by Three Different Methods

In this study, GC×GC-MS was employed for the qualitative analysis of VOCs in L. decastes treated by three different cooking methods. As shown in Table 2, a total of 73 VOCs were identified, including 23 hydrocarbons, 14 alcohols, 10 ketones, seven aldehydes, six ethers, three esters, two terpenes, and eight other substances. Among them, the VOCs in CK were the most complex, with 57 compounds detected. A total of 45 and 37 VOCs were detected in FP and HPS, respectively. BT contained the fewest VOCs, with only 22 compounds detected.

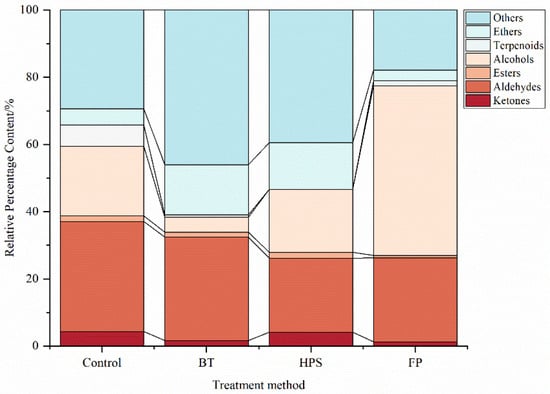

The proportions of VOCs in L. decastes samples treated with different methods are shown in Figure 3. Among these four samples, aldehydes and alcohols had relatively high contents and are the major VOCs in L. decastes. These results are consistent with those of Yang et al. []. Aldehydes accounted for 32.78%, 24.94%, 30.77%, and 22.10% of the total VOCs in CK, FP, BT, and HPS, respectively. Alcohols accounted for 20.8%, 50.51%, 4.43%, and 18.74% of the total VOCs in CK, FP, BT, and HPS, respectively. The proportion of alcohols was relatively low in BT and slightly decreased in HPS as well. The possible reasons for these phenomena can be summarized as follows: (1) This may be because low-boiling-point alcohols volatilize significantly with water vapor during heating, resulting in a reduction in their residual amounts in the food []. (2) Alcohols degrade during boiling and are oxidized to aldehydes or ketones upon contact with oxygen. In contrast, HPS improves the heat transfer efficiency of steam through high pressure, enabling the interior of L. decastes to quickly reach the treatment temperature (121 °C) and avoiding the continuous oxidation of alcohols caused by long-term low-temperature preheating []. (3) The honeycomb structure formed in L. decastes by HPS can create “local retention spaces”, slowing down the volatilization rate of alcohols with steam, whereas the BT group exhibits dense tissue due to fiber shrinkage, making alcohols more likely to directly volatilize.

Figure 3.

Percentage content of each substance in fresh L. decastes cooked by three different methods.

In FP, 1-octanol (4.32%), (E)-2-hexen-1-ol (34.99%), and nonane (7.22%) were detected at significantly higher levels compared with other groups, while no terpinolene was detected. These differences may be attributed to the promotion of biosynthetic pathways of alcohol-type VOCs in mushrooms by mechanical damage []. Terpinolene was also not detected in BT and HPS, which may be due to the thermal degradation of heat-sensitive aromatic compounds (such as terpenes) through oxidation and C-C bond cleavage during heat treatment []. The specific increases in pentadecane (6.95%), heptadecane (4.41%), and tetradecane (2.82%) in BT indicate that heating selectively promotes the formation of long-chain alkanes. The contents of heptadecane and tetradecane in HPS were also relatively high, but their overall concentrations were lower than those in BT, suggesting that HPS is less effective than BT in promoting the formation of these compounds. These findings indicate that fatty acids undergo thermal decomposition to produce alkanes under humid conditions [].

In HPS, isophorone (2.42%), and 2-octenone (1.01%) were detected, implying that high pressure may alter the structure of key enzymes involved in aromatic compound synthesis, thereby increasing ketone production and affecting aroma formation []. Moreover, the increased levels of 3,4-hexanediol (14.16%), and benzaldehyde (8.23%) in HPS suggested that high temperature and pressure might disrupt cell-wall structures, activate enzyme systems, and promote the oxidative cleavage of unsaturated fatty acids [], leading to increased aldehyde production. Notably, benzaldehyde was not detected in BT, indicating that it may be volatile or prone to decomposition under humid and hot conditions.

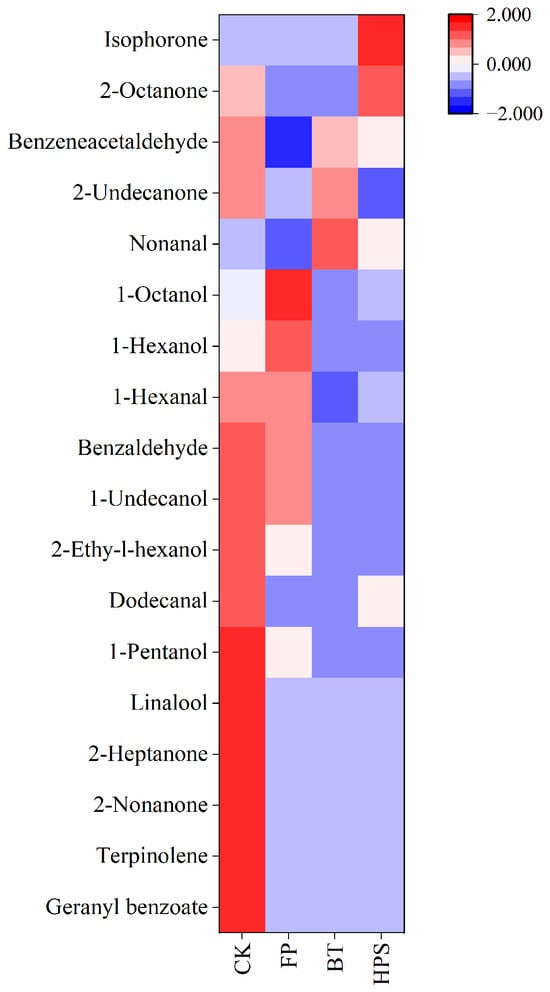

As can be seen from Table 2, among the 73 identified compounds, 18 have corresponding odor descriptions retrievable in the FEMA database. We plotted these 18 odor substances into a heatmap (Figure 4). Further analysis revealed that the contents of benzeneacetaldehyde, benzaldehyde, 1-undecanol, 2-ethyl-1-hexanol, dodecanal, 1-pentanol, linalool, 2-heptanone, 2-nonanone, terpinolene, and geranyl benzoate were relatively high in CK. These compounds mainly have bitter almond, pine, citrus, berry, and floral notes, which constitute the complex odor profile of the CK group. In FP, relatively high contents of 1-hexanol and 1-octanol were detected. These compounds mainly have banana, floral, bitter almond, and burnt matches aromas. In BT, nonanal had high contents, which endow boiled L. decastes with fat, floral, green, and lemon aromas. In HPS, the content of isophorone and 2-octanone were significantly high, which endows high-pressure steam-treated L. decastes with fat, fragrant, cedarwood, and spice aromas.

Figure 4.

Heatmap analysis of volatile aroma compounds in fresh L. decastes cooked by three different methods.

In summary, aldehydes and alcohols are the main VOCs in L. decastes. Among the three aforementioned treatment methods, the alcohol content in FP was significantly higher than that in BT and HPS. This may be because mechanical damage to L. decastes activates the enzyme system in cells, thereby promoting the significant synthesis of alcohols such as (E)-2-hexen-1-ol (34.99%). Benzeneacetaldehyde, benzaldehyde, 1-undecanol, 2-ethyl-1-hexanol, dodecanal, 1-pentanol, linalool, 2-heptanone, 2-nonanone, terpinolene, geranyl benzoate, 1-hexanol, and 1-octanol constitute the main flavor components of L. decastes. Different treatment methods have varying effects on its flavor substances: FP can increase the concentration of main flavor substances by promoting alcohol synthesis through mechanical damage; BT and HPS promote the thermal decomposition of fatty acids to generate hydrocarbons. This agreed with the FTIR results.

Table 2.

Qualitative results of GC×GC-MS data from fresh L. decastes cooked by three different methods.

Table 2.

Qualitative results of GC×GC-MS data from fresh L. decastes cooked by three different methods.

| Count | Type | Compound | Formula | CAS | Odor Description | Relative Percentage Content/% | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CK | FP | BT | HPS | ||||||

| 1 | Hydrocarbons | 3-Methyl-pentane | C6H14 | 96-14-0 | ND | ND | 0.14 ± 0.04 b | ND | 0.63 ± 0.11 a |

| 2 | Butane | C4H10 | 106-97-8 | ND | ND | ND | 2.41 ± 1.60 | ND | |

| 3 | Propane | C3H8 | 74-98-6 | ND | 1.15 ± 0.13 | ND | ND | ND | |

| 4 | 2-Bromo-2-methyl-butane | C5H11Br | 507-36-8 | ND | 0.48 ± 0.16 a | 0.21 ± 0.03 b | ND | ND | |

| 5 | 1-Octene | C8H16 | 111-66-0 | ND | 0.23 ± 0.07 | ND | ND | ND | |

| 6 | 1,3,5,7-Cyclooctatetraene | C8H8 | 629-20-9 | ND | 0.39 ± 0.06 | ND | ND | ND | |

| 7 | 1-Undecene | C11H22 | 821-95-4 | ND | 0.60 ± 0.56 a | ND | ND | 0.31 ± 0.17 a | |

| 8 | Nonane | C9H20 | 111-84-2 | ND | ND | 7.22 ± 0.82 | ND | ND | |

| 9 | Decane | C10H22 | 124-18-5 | ND | ND | ND | ND | 0.31 ± 0.05 | |

| 10 | Terpinolene | C10H16 | 586-62-9 | Pine | 0.51 ± 0.17 | ND | ND | ND | |

| 11 | 1-Dodecene | C12H24 | 112-41-4 | ND | 1.04 ± 1.15 a | 0.24 ± 0.05 a | ND | ND | |

| 12 | Undecane | C11H24 | 1120-21-4 | ND | 1.24 ± 1.04 a | ND | ND | 1.33 ± 0.63 a | |

| 13 | 1-Tetradecene | C14H28 | 1120-36-1 | ND | 0.36 ± 0.12 a | 0.18 ± 0.12 a | ND | ND | |

| 14 | 1-Tridecene | C13H26 | 2437-56-1 | ND | ND | 0.15 ± 0.08 | ND | ND | |

| 15 | β-Methylstyrene | C9H10 | 637-50-3 | ND | 0.53 ± 0.15 b | 0.35 ± 0.08 b | 1.13 ± 0.16 a | 0.71 ± 0.28 b | |

| 16 | 1,4-Diethyl-benzene | C10H14 | 105-05-5 | ND | ND | 0.19 ± 0.05 b | ND | 0.50 ± 0.05 a | |

| 17 | Azulene | C10H8 | 275-51-4 | ND | 0.42 ± 0.07 a | 0.22 ± 0.05 b | ND | ND | |

| 18 | Dodecane | C12H26 | 112-40-3 | ND | 0.28 ± 0.03 b | ND | 0.79 ± 0.31 a | 0.74 ± 0.21 a | |

| 19 | Tetradecane | C14H30 | 629-59-4 | ND | ND | 0.29 ± 0.12 b | 2.82 ± 1.10 a | 2.01 ± 1.00 ab | |

| 20 | Pentadecane | C15H32 | 629-62-9 | ND | 2.13 ± 0.18 c | 1.55 ± 0.34 c | 6.95 ± 0.57 a | 4.36 ± 1.34 b | |

| 21 | Heptadecane | C17H36 | 629-78-7 | ND | ND | 0.76 ± 0.32 a | 4.41 ± 2.80 a | 2.61 ± 1.67 a | |

| 22 | Hexadecane | C16H34 | 544-76-3 | ND | ND | ND | ND | 2.67 ± 1.28 | |

| 23 | Heneicosane | C21H44 | 629-94-7 | ND | ND | ND | 0.62 ± 0.15 | ND | |

| 24 | Alcohols | Tert-butanol | C4H10O | 75-65-0 | ND | 0.79 ± 0.15 c | 0.69 ± 0.26 c | 2.49 ± 0.41 a | 1.45 ± 0.19 b |

| 25 | 2-Methyl-3-pentanol | C6H14O | 565-67-3 | ND | 0.36 ± 0.05 | ND | ND | ND | |

| 26 | Cyclopentanol | C5H10O | 96-41-3 | ND | 0.55 ± 0.06 a | 0.46 ± 0.06 a | ND | ND | |

| 27 | 1-Pentanol | C5H12O | 71-41-0 | Balsamic, Fruit, Green, Pungent, Yeast | 0.55 ± 0.08 a | 0.20 ± 0.01 b | ND | ND | |

| 28 | 1-Hexanol | C6H14O | 111-27-3 | Banana, Flower, Grass, Herb | 2.93 ± 0.33 b | 5.67 ± 0.60 a | ND | ND | |

| 29 | 3,4-Bis(4-hydroxyphenyl)-3,4-hexanediol | C18H22O4 | 7507-01-09 | ND | 4.54 ± 2.91 b | 2.00 ± 0.41 b | ND | 14.16 ± 0.55 a | |

| 30 | 1-Octanol | C8H18O | 111-87-5 | Bitter Almond, Burnt Matches, Fat, Floral | 1.29 ± 0.81 b | 4.32 ± 0.28 a | ND | 0.63 ± 0.19 b | |

| 31 | (Z)-2-Penten-1-ol | C5H10O | 1576-95-0 | ND | ND | ND | ND | 0.75 ± 0.20 | |

| 32 | (E)-2-Hexen-1-ol | C6H12O | 928-95-0 | ND | 4.53 ± 0.93 b | 34.99 ± 1.83 a | ND | ND | |

| 33 | 9,10-Tetradecenol | C14H28O | 52957-16-1 | ND | 2.50 ± 0.22 | ND | ND | ND | |

| 34 | 1-(2-Butoxyethoxy)-2-Propanol | C9H20O3 | 124-16-3 | ND | 0.47 ± 0.10 bc | 0.32 ± 0.11 c | 1.17 ± 0.14 a | 0.84 ± 0.28 ab | |

| 35 | 2-Ethyl-1-hexanol | C8H18O | 104-76-7 | Green, Rose | 0.36 ± 0.04 a | 0.19 ± 0.01 b | ND | ND | |

| 36 | 2-(Hydroxymethyl)-2-Nitro-1,3-propanediol | C4H9NO5 | 126-11-4 | ND | 0.22 ± 0.07 a | 0.12 ± 0.02 b | ND | ND | |

| 37 | 1-Undecanol | C11H24O | 112-42-5 | Mandarin | 1.72 ± 0.15 a | 1.55 ± 0.35 ab | 0.76 ± 0.09 c | 0.90 ± 0.47 bc | |

| 38 | Ketones | 4-Methyl-2-hexanone | C7H14O | 105-42-0 | ND | 0.55 ± 0.13 | ND | ND | ND |

| 39 | Methyl isobutyl ketone | C6H12O | 108-10-1 | ND | 0.38 ± 0.08 | ND | ND | ND | |

| 40 | 2-Methyl-cyclopentanone | C6H10O | 1120-72-5 | ND | ND | 0.34 ± 0.03 | ND | ND | |

| 41 | 2-Heptanone | C7H14O | 110-43-0 | Blue Cheese, Fruit, Green, Nut, Spice | 0.20 ± 0.03 | ND | ND | ND | |

| 42 | 2-Dodecanone | C12H24O | 6175-49-1 | ND | 0.22 ± 0.03 | ND | ND | ND | |

| 43 | 2-Octanone | C8H16O | 111-13-7 | Fat, Fragrant, Mold | 0.77 ± 0.14 a | ND | ND | 1.01 ± 0.21 a | |

| 44 | Isophorone | C9H14O | 78-59-1 | Cedarwood, Spice | ND | ND | ND | 2.42 ± 1.55 | |

| 45 | 4,4-Dimethyl-2-cyclohexen-1-one | C8H12O | 1073-13-8 | ND | 0.42 ± 0.04 | ND | ND | ND | |

| 46 | 2-Nonanone | C9H18O | 821-55-6 | Fragrant, Fruit, Green, Hot Milk | 0.27 ± 0.03 | ND | ND | ND | |

| 47 | 2-Undecanone | C11H22O | 112-12-9 | Fresh, Green, Orange, Rose | 1.53 ± 0.10 a | 0.92 ± 0.17 b | 1.61 ± 0.30 a | 0.63 ± 0.16 b | |

| 48 | Aldehydes | 1-hexanal | C6H12O | 66-25-1 | Apple, Fat, Fresh, Green, Oil | 8.97 ± 0.48 a | 8.46 ± 0.58 a | ND | 1.92 ± 0.52 b |

| 49 | 2,3,6-Trichlorobenzaldehyde | C7H3Cl3O | 4659-47-6 | ND | 5.46 ± 0.73 c | 2.43 ± 0.33 c | 18.67 ± 2.51 a | 9.49 ± 0.84 b | |

| 50 | Nonanal | C9H18O | 124-19-6 | Fat, Floral, Green, Lemon | 3.09 ± 1.36 b | 1.68 ± 0.56 b | 7.91 ± 1.38 a | 5.15 ± 3.39 ab | |

| 51 | Benzaldehyde | C7H6O | 100-52-7 | Bitter Almond, Burnt Sugar, Cherry, Malt, Roasted Pepper | 9.81 ± 3.42 a | 8.23 ± 3.41 a | ND | 1.12 ± 0.29 b | |

| 52 | Undecanal | C11H22O | 112-44-7 | ND | 1.32 ± 0.69 b | 3.82 ± 0.62 a | 2.46 ± 0.37 ab | 1.96 ± 0.69 b | |

| 53 | Benzeneacetaldehyde | C8H8O | 122-78-1 | Berry, Geranium, Honey, Nut, Pungent | 1.78 ± 0.21 a | 0.33 ± 0.02 b | 1.73 ± 0.41 a | 1.34 ± 0.16 a | |

| 54 | Dodecanal | C12H24O | 112-54-9 | Citrus, Fat, Lily | 2.34 ± 3.07 a | ND | ND | 1.12 ± 0.24 a | |

| 55 | Ethers | Methoxy-ethen | C3H6O | 107-25-5 | ND | ND | 1.91 ± 1.16 c | 10.89 ± 1.42 a | 6.70 ± 1.81 b |

| 56 | Allyl ethyl ether | C5H10O | 557-31-3 | ND | 0.55 ± 0.32 | ND | ND | ND | |

| 57 | Dibutyl ether | C8H18O | 142-96-1 | ND | 0.51 ± 0.06 ab | 0.34 ± 0.13 b | ND | 0.83 ± 0.25 a | |

| 58 | 2-Heptyl-1,3-dioxolane | C10H20O2 | 4359-57-3 | ND | 1.34 ± 0.34 | ND | ND | ND | |

| 59 | N-Acetylcolchinol methyl ether | C21H25NO5 | 65967-01-3 | ND | 2.44 ± 1.40 bc | 0.71 ± 0.10 c | 4.06 ± 0.36 ab | 6.35 ± 1.86 a | |

| 60 | 2-(2-Butoxyethoxy)-Ethanol | C8H18O3 | 112-34-5 | ND | ND | 0.21 ± 0.04 | ND | ND | |

| 61 | Esters | Sec-butyl nitrite | C4H9NO2 | 924-43-6 | ND | 0.78 ± 0.17 ab | 0.54 ± 0.24 b | 1.48 ± 0.32 a | 1.28 ± 0.56 ab |

| 62 | Geranyl benzoate | C17H22O2 | 94-48-4 | Floral | 0.43 ± 0.19 | ND | ND | ND | |

| 63 | Propylene carbonate | C4H6O3 | 108-32-7 | ND | 0.39 ± 0.10 ab | 0.24 ± 0.06 b | ND | 0.44 ± 0.10 a | |

| 64 | Terpenoids | Retinol | C20H28O | 116-31-4 | ND | 4.70 ± 0.92 a | 1.25 ± 0.08 b | 0.76 ± 0.17 b | ND |

| 65 | Linalool | C10H18O | 78-70-6 | Coriander, Floral, Lavender, Lemon, Rose | 1.60 ± 0.97 a | 0.17 ± 0.03 b | ND | ND | |

| 66 | Others | 3-Pyrroline | C4H7N | 109-96-6 | ND | 1.15 ± 0.06 a | 0.74 ± 0.18 b | ND | ND |

| 67 | 12,13-Dihydro-7H-dibenzo(a,g)carbazole | C20H15N | 63077-00-9 | ND | 2.43 ± 0.75 a | 2.27 ± 0.84 a | 10.71 ± 7.57 a | 4.23 ± 0.74 a | |

| 68 | 9,10-Dihydro-9,9-dimethyl- Acridine | C15H14N | 53884-62-1 | ND | 0.57 ± 0.11 b | 0.32 ± 0.04 c | ND | 0.96 ± 0.13 a | |

| 69 | Dibenzyl ketoxime | C14H13NO | 1788-31-4 | ND | ND | 0.23 ± 0.02 | ND | ND | |

| 70 | Vincamine | C21H26N2O3 | 1617-90-9 | ND | 6.63 ± 1.29 b | ND | ND | 8.98 ± 1.05 a | |

| 71 | Prednisolone acetate | C23H30O6 | 52-21-1 | ND | 1.89 ± 1.55 | ND | ND | ND | |

| 72 | Colchicine | C22H25NO6 | 64-86-8 | ND | 6.37 ± 1.41 b | 2.51 ± 0.48 b | 14.02 ± 4.25 a | 7.16 ± 1.11 b | |

| 73 | Beclomethasone | C22H29ClO5 | 4419-39-0 | ND | 0.96 ± 0.34 ab | 0.32 ± 0.03 b | 2.13 ± 0.81 a | 2.02 ± 1.00 a | |

ND, not detected. The description of the compound’s odor is based on the relevant literature and research [,,], as well as the FEMA database. Relative percentage content is expressed as mean and ±standard deviation of three determinations. Different superscript letters in the same row imply significant differences (p < 0.05).

3.4. GC-IMS Analysis of Fresh L. decastes Cooked by Three Different Methods

To thoroughly investigate the variation of VOCs under different processing methods, a qualitative analysis was conducted by comparing retention times and drift times with reference standards. Peak intensities are relative values from GC-IMS detection, reflecting the abundance of each compound; higher values indicate higher relative concentration. A total of 22 known VOCs were identified and categorized into five major classes: seven alcohols, six aldehydes, five esters, three ketones, and one other compound (Table 3). No specific compounds were identified for areas 1 to 17 in the database. Among the VOCs detected in L. decastes, alcohols accounted for the highest proportion (55.5%), followed by aldehydes (30.2%), which is consistent with the findings obtained via GC×GC-MS analysis.

Table 3.

Volatile compounds identified by GC-IMS of fresh L. decastes cooked by three different ways.

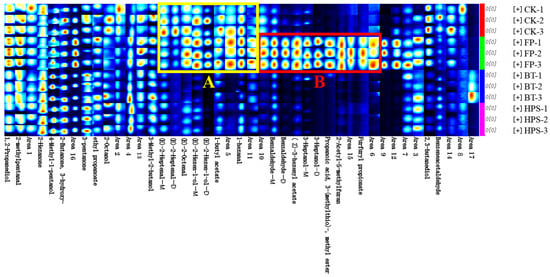

To illustrate the differences in volatile profiles among the samples, characteristic fingerprints were established (Figure 5). Each row in the figure represents a sample or all signal peaks selected during processing. As shown in Figure 5, there were significant differences in the VOCs of the four different flavor samples. The peak signal intensity of VOCs in region A was significantly reduced after BT or HPS treatment. In contrast, the peak signal intensity in region B was significantly increased after FP treatment but remarkably decreased following BT or HPS treatment. Five compounds, namely, (E)-2-hexen-1-ol, (E)-2-heptenal, (E)-2-octenal, 1-butyl acetate, and 1-hexanal, were identified in region A. Among these, (E)-2-heptenal, (E)-2-octenal, 1-butyl acetate, and 1-hexanal contribute almond, fat, dandelion, and fruit odors to the CK and FP groups, respectively. In region B, six compounds—benzaldehyde, (Z)-3-hexenyl acetate, 3-heptanol, 2-acetyl-5-methylfuran, propanoic acid, 3-(methylthio)-, methyl ester, and furfuryl propionate—were identified, endowing the FP group with a complex and layered flavor profile featuring notes of bitter almond, herb, vegetable, nut, tropical fruit, floral, and spicy aromas. In addition, CK, FP, BT, and HPS samples also contained relatively high contents of 2-octanol, benzeneacetaldehyde, 2-methylpentanal, ethyl propanoate, and 3-hydroxy-2-butanone. These compounds impart fat, berry, apple, and butter aromas to the four types of samples.

Figure 5.

Fingerprint profiles of volatile compounds in fresh L. decastes cooked by three different methods.

Notably, the levels of (E)-2-hexen-1-ol and (Z)-3-hexenyl acetate in CK and FP were significantly higher than those in BT and HPS. This may be attributed to the activation of enzyme activity in cells and the initiation of cellular defense mechanisms when fresh L. decastes was damaged and exposed to oxygen, leading to a substantial increase in the synthesis of these two substances [,]. In FP, the peak signal intensity of benzaldehyde in L. decastes was significantly higher than BT and HPS, which is consistent with the previous results of FTIR and GC×GC-MS. Additionally, the signal intensity of 2-pentanone in the BT group was 1.4–24 times higher than in other groups, suggesting its potential as a characteristic marker compound for BT. This fruity aroma may originate from the synthesis of ketones under prolonged heating conditions []. The signal intensities of 2-butanone, 3-hydroxy-, and 2-hexanone in HPS significantly increased, indicating enhanced release under high-pressure conditions.

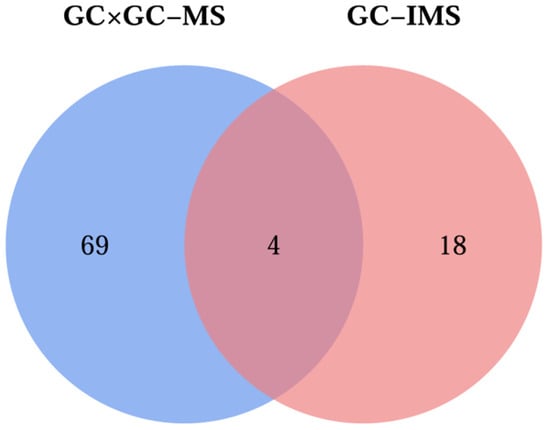

3.5. Comparative Analysis of Volatile Compounds by GC×GC-MS and GC-IMS

A comparative analysis was performed using GC×GC-MS and GC-IMS techniques, which identified 73 and 22 VOCs in the four groups of L. decastes samples, respectively. Among them, four VOCs (Figure 6), including benzaldehyde, benzeneacetaldehyde, (E)-2-hexen-1-ol, and 1-hexanal, were jointly identified by both detection methods. Additionally, both methods confirmed that alcohols and aldehydes are the main VOCs of L. decastes, and this result is consistent with the research findings of Yang et al. [].

Figure 6.

Venn diagram for GC×GC-MS and GC-IMS results of volatile compounds in fresh L. decastes cooked by three different methods.

Both GC×GC-MS and GC-IMS have their own advantages in detecting VOCs. GC×GC-MS separates VOCs through two-dimensional column (SH-Rtx-5sil MS and BPX-50) chromatography and programmed temperature ramping (40–230 °C). Qualitative analysis is then performed by matching mass spectra to standard libraries (e.g., NIST) and interpreting fragment ions. In contrast, GC-IMS uses a single column, and the drift tube temperature of the ion mobility spectrometer (IMS) is fixed (45 °C). Qualitative analysis relies on detecting the ion drift time and retention time in an electric field, then matching to a custom-built IMS library.

Based on these characteristics, GC×GC-MS can detect more types of VOCs, especially exhibiting advantages in the identification of hydrocarbons, ethers, and terpenoids, and can more comprehensively reflect the overall composition of VOCs in L. decastes. It detects a wider variety of substances, many of which are different from those detected by GC-IMS. While GC-IMS has the advantages of fast detection speed (completion within 30 min per sample) and simple sample pretreatment, it complements the results of GC×GC-MS in the identification of ester compounds.

4. Conclusions

The three cooking methods (FP, BT, and HPS) did not alter the functional groups of L. decastes. FP broke the mushrooms into small fragments with smooth surfaces, BT caused surface shrinkage, and HPS promoted the formation of a unique honeycomb-like porous structure on the surface. GC×GC-MS identified 73 VOCs, while GC-IMS detected 22, among which 4 (benzaldehyde, benzeneacetaldehyde, (E)-2-hexen-1-ol, 1-hexanal) were identified by both methods. The results from these two analytical techniques indicated that alcohols and aldehydes are the main VOCs of L. decastes. Notably, the significant increase in (E)-2-hexen-1-ol and (Z)-3-hexenyl acetate in FP may be related to the defense mechanism after cell damage.

This study explored the flavor changes during the processing of L. decastes, providing practical technical parameters for the flavor design of deep-processed products of L. decastes and also offering theoretical and methodological references for optimizing the flavor characteristics of other edible mushrooms during processing.

Author Contributions

X.W.: Writing—original draft; methodology; formal analysis; data curation. Y.W.: Software; supervision. W.L.: Data curation. C.L.: Writing—review and editing; supervision; funding acquisition. J.C.: Writing—review and editing; supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 31860436, no. 32460569) and the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangxi Province (grant nos. 20181BAB204001, 20212BAB205002).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to Haixin Ding, Rendan Zhou, Sanmei Liu, and Hu Su from Jiangxi Science & Technology Normal University for providing guidance and granting access to the necessary instruments.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

Fragmenting process (FP); boiling treatment (BT); high-pressure steam (HPS); volatile compounds (VOCs); scanning electron microscopy (SEM); Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR); comprehensive two-dimensional gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC×GC-MS); gas chromatography–ion mobility spectrometry (GC-IMS).

References

- Li, X.; Yang, H.; Li, H.; Li, W.; Wu, D.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, P.; Liu, Y.; Chen, W.; Yang, Y. Multidimensional quality assessment of Lyophyllum decastes mushroom varieties: Nutritional components, protein characteristics and umami profiling. LWT 2025, 226, 117974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Liang, B.; Wang, J.; Dai, Y. Ultrasound-assisted extraction of polysaccharides from Lyophyllum decastes: Structural analysis and bioactivity assessment. Molecules 2025, 30, 961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, L.; Yang, W.; Qiu, T.; Gao, X.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, S.; Cui, H.; Guo, L.; Yu, H.; Yu, H. Complete genome sequences and comparative secretomic analysis for the industrially cultivated edible mushroom Lyophyllum decastes reveals insights on evolution and lignocellulose degradation potential. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1137162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Qin, Y.; Kong, Y.; Karunarathna, S.C.; Liang, Y.; Xu, J. Optimization of protoplast preparation conditions in Lyophyllum decastes and transcriptomic analysis throughout the process. J. Fungi 2024, 10, 886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Huang, J.; Jin, W.; Sun, S.; Hu, K.; Li, J. Effects of drying methods on the physicochemical aspects and volatile compounds of Lyophyllum decastes. Foods 2022, 11, 3249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Zhang, H.H.; Claver, I.P.; Zhu, K.X.; Peng, W.; Zhou, H.M. Effect of different cooking methods on the flavour constituents of mushroom (Agaricus bisporus (Lange) Sing) soup. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2011, 46, 1100–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, J.; Li, H.; Liu, Y.; Li, C.; Fang, Z.; Hu, B.; Li, X.; Zeng, Z.; Liu, Y. Changes in flavor and biological activities of Lentinula edodes hydrolysates after Maillard reaction. Food Chem. 2024, 431, 137138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, N.; Zhang, S.; Zhou, P.; Zhang, W.; Luo, X.; Cao, J.; Sun, D. Analysis of volatile flavor substances in the enzymatic hydrolysate of Lanmaoa asiatica mushroom and its Maillard reaction products based on E-Nose and GC-IMS. Foods 2022, 11, 4056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, W.; Niu, J.; Han, F.; Zhong, K.; Li, R.; Sui, W.; Ma, C.; Wu, M. Steam explosion-assisted extraction of ergosterol and polysaccharides from Flammulina velutipes (golden needle mushroom) root waste. Foods 2024, 13, 1860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, Z.X.; Tan, W.C. Impact of optimised cooking on the antioxidant activity in edible mushrooms. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 54, 4100–4111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Gan, Y.; Li, F.; Yan, C.; Li, H.; Feng, Q. Effects of high pressure in combination with thermal treatment on lipid hydrolysis and oxidation in pork. LWT 2015, 63, 136–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosshauser, S.; Schieberle, P. Characterization of the key odorants in pan-fried white mushrooms (Agaricus bisporus L.) by means of molecular sensory science: Comparison with the raw mushroom tissue. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2013, 61, 3804–3813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selli, S.; Guclu, G.; Sevindik, O.; Kelebek, H. Variations in the key aroma and phenolic compounds of champignon (Agaricus bisporus) and oyster (Pleurotus ostreatus) mushrooms after two cooking treatments as elucidated by GC–MS-O and LC-DAD-ESI-MS/MS. Food Chem. 2021, 354, 129576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ieda, T.; Horii, Y.; Petrick, G.; Yamashita, N.; Ochiai, N.; Kannan, K. Analysis of nonylphenol isomers ina technical mixture and in waterby comprehensive two-dimensionalgas chromatography-mass spectrometry. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2005, 39, 7202–7207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, L.; Xu, P.; Chen, J.; Chen, H.; Qin, J.; Wu, X.; Liu, C.; He, Z.; Liu, Y.; Guan, T. Comprehensive analysis of spatial heterogeneity reveals the important role of the upper-layer fermented grains in the fermentation and flavor formation of Qingxiangxing baijiu. Food Chem. X 2024, 22, 101508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Li, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, C.; Ren, J.; Zhao, X. Effects of origin on the volatile flavor components of morels based on GC-IMS and GC×GC-ToF-MS. Sci. Agric. Sin. 2024, 57, 4553–4567. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, M.; Xu, S.; Xing, S.; Tang, C.; Liu, J.; Kan, J.; Dai, Q.; Qian, C. Effect of different thermal methods on the flavor characteristics of Pleurotus geesteranus: The key odor-active compounds and taste components. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2025, 146, 107948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, Y.; Yu, M.; Zhou, H.; Zhang, P.; Yang, W.; Li, B. Effect of boiling time on nutritional characteristics and antioxidant activities of Lentinus edodesand its broth. CyTA-J. Food 2020, 18, 543–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, X.; Yao, L.; Qu, Y.; Zhao, F.; Yun, J. Structure, physicochemical properties, and hypolipidemic activity of soluble dietary fiber obtained from button mushroom (Agaricus bisporus). Food Chem. X 2025, 29, 102657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Ni, L.; Sun, M.; Hu, F.; Guo, Z.; Zeng, H.; Sun, W.; Zhang, M.; Wu, M.; Zheng, B. Enhancing the hypolipidemic and functional properties of Flammulina velutipes root dietary fiber via tteam explosion. Foods 2024, 13, 3621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, W.; Chen, X.; Chen, X.; Pan, T.; Xue, X.; Zhou, D.; Fu, H. Comparison of volatile aroma compounds in two different flavor types Baijiu based on GC×GC-TOF-MS. China Brew. 2022, 41, 215–221. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, M.; Zhou, C.; Su, W.; Tan, R.; Ma, L.; Pan, W.; Li, W. Dynamic effects of ultrasonic treatment on flavor and metabolic pathway of pumpkin juice during storage based on GC–MS and GC-IMS. Food Chem. 2025, 469, 142599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, L.; Wang, C.; Shi, H.; Zhou, W.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, X. Combination of steam explosion pretreatment and anaerobic alkalization treatment to improve enzymatic hydrolysis of Hippophae rhamnoides. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 289, 121693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Bau, T.; Jin, R.; Cui, X.; Zhang, Y.; Kong, W. Comparison of different drying techniques for shiitake mushroom (Lentinus edodes): Changes in volatile compounds, taste properties, and texture qualities. LWT 2022, 164, 113651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paciulli, M.; Ganino, T.; Carini, E.; Pellegrini, N.; Pugliese, A.; Chiavaro, E. Effect of different cooking methods on structure and quality of industrially frozen carrots. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 53, 2443–2451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Ye, J.; Xue, C.; Wang, Y.; Liao, W.; Mao, L.; Yuan, M.; Lian, S. Structural characteristics and bioactive properties of a novel polysaccharide from Flammulina velutipes. Carbohydr. Polym. 2018, 197, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kannan, R.R.R.; Anantharaman, R.A.; Anantharaman, P. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy analysis of seagrass polyphenols. Curr. Bio. Act. Compd. 2011, 7, 118–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.F.; Xu, F.; Sun, R.C.; Geng, Z.C.; Fowler, P.; Baird, M.S. Characteristics of degraded hemicellulosic polymers obtained from steam exploded wheat straw. Carbohydr. Res. 2005, 340, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Lv, G.; He, W.; Shi, L.; Pan, H.; Fan, L. Effects of extraction methods on the antioxidant activities of polysaccharides obtained from Flammulina velutipes. Carbohydr. Polym. 2013, 98, 1524–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auxenfans, T.; Crônier, D.; Chabbert, B.; Paës, G. Understanding the structural and chemical changes of plant biomass following steam explosion pretreatment. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2017, 10, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahanta, B.P.; Bora, P.K.; Kemprai, P.; Borah, G.; Lal, M.; Haldar, S. Thermolabile essential oils, aromas and flavours: Degradation pathways, effect of thermal processing and alteration of sensory quality. Food Res. Int. 2021, 145, 110404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grebenteuch, S.; Kanzler, C.; Klaußnitzer, S.; Kroh, L.W.; Rohn, S. The formation of methyl ketones during lipid oxidation at elevated temperatures. Molecules 2021, 26, 1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Combet, E.; Henderson, J.; Eastwood, D.C.; Burton, K.S. Influence of sporophore development, damage, storage, and tissue specificity on the enzymic formation of volatiles in mushrooms (Agaricus bisporus). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009, 57, 3709–3717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maher, K.D.; Kirkwood, K.M.; Gray, M.R.; Bressler, D.C. Pyrolytic decarboxylation and cracking of stearic acid. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2008, 47, 5328–5336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lomelí-Martín, A.; Martínez, L.M.; Welti-Chanes, J.; Escobedo-Avellaneda, Z. Induced changes in aroma compounds of foods treated with high hydrostatic pressure: A review. Foods 2021, 10, 878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wu, Z.; Li, F. Combined effects of high-pressure and thermal treatments on lipid oxidation and enzymes in pork. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2016, 25, 261–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Xu, R.; Jia, Q.; Feng, T.; Huang, Q.; Ho, C.-T.; Song, S. Identification of dihydro-β-ionone as a key aroma compound in addition to C8 ketones and alcohols in Volvariella volvacea mushroom. Food Chem. 2019, 293, 333–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.-X.; Rana, M.M.; Liu, G.-F.; Ling, T.-J.; Gruber, M.Y.; Wei, S. Differential contribution of jasmine floral volatiles to the aroma of scented green tea. J. Food Qual. 2017, 2017, 5849501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y.-Q.; He, F.; Zhu, B.-Q.; Lan, Y.-B.; Pan, Q.-H.; Li, C.-Y.; Reeves, M.J.; Wang, J. Free and glycosidically bound aroma compounds in cherry (Prunus avium L.). Food Chem. 2014, 152, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, D.; Bai, L.; Feng, X.; Chen, Y.P.; Zhang, D.; Yao, W.; Zhang, H.; Chen, G.; Liu, Y. Characterization of Jinhua ham aroma profiles in specific to aging time by gas chromatography-ion mobility spectrometry (GC-IMS). Meat Sci. 2020, 168, 108178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levent, O. A detailed comparative study on some physicochemical properties, volatile composition, fatty acid, and mineral profile of different almond (Prunus dulcis L.) varieties. Horticulturae 2022, 8, 488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Leong, S.M.; Zhao, F.; Zhao, F.; Yang, T.; Liu, S. Viscozyme L pretreatment on palm kernels improved the aroma of palm kernel oil after kernel roasting. Food Res. Int. 2018, 107, 172–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.; Wang, L.; Li, Y.; Chen, Y.; Chen, G.; Jia, L.; Ge, Y. Comparative analysis of key flavor compounds in various baijiu types using E-nose, HS-SPME-GC–MS/MS, and HS-GC-IMS technologies. Food Chem. X 2025, 29, 102689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frontini, A.; De Bellis, L.; Luvisi, A.; Blando, F.; Allah, S.M.; Dimita, R.; Mininni, C.; Accogli, R.; Negro, C. The green leaf volatile (Z)-3-hexenyl acetate is differently emitted by two varieties of Tulbaghia violacea plants routinely and after wounding. Plants 2022, 11, 3305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).