Directive vs. Reductive Front-of-Pack Labels: Differences in Italian Consumers’ Responses to the Nutri-Score and the NutrInform Battery

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework and Research Hypotheses

2.1. FoP Labelling Systems

2.2. Sociodemographic Characteristics and Purchasing Behavior

2.3. Orthorexia Nervosa

2.4. Cognitive Abilities

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Design

3.2. Front-of-Pack Labels

3.3. Products and Nutritional Levels

3.4. Survey Sections

3.5. Participants

3.6. Statistical Analysis

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Participants’ Profile

4.1.1. Sociodemographic Characteristics and Purchasing Behaviors

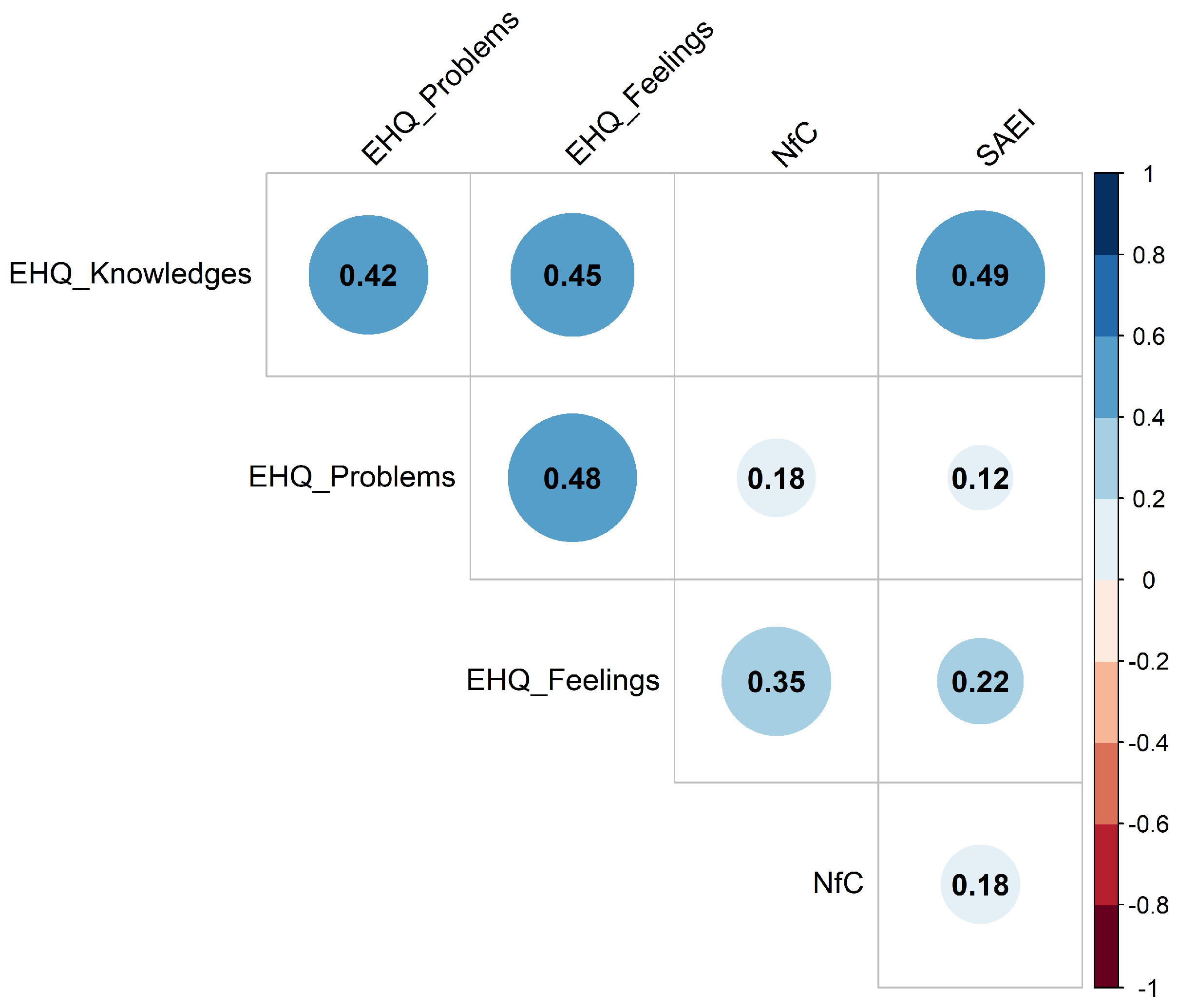

4.1.2. Orthorexia Nervosa and Cognitive Abilities

4.2. Impact of FoP Labels on Healthiness Perception and Willingness to Buy

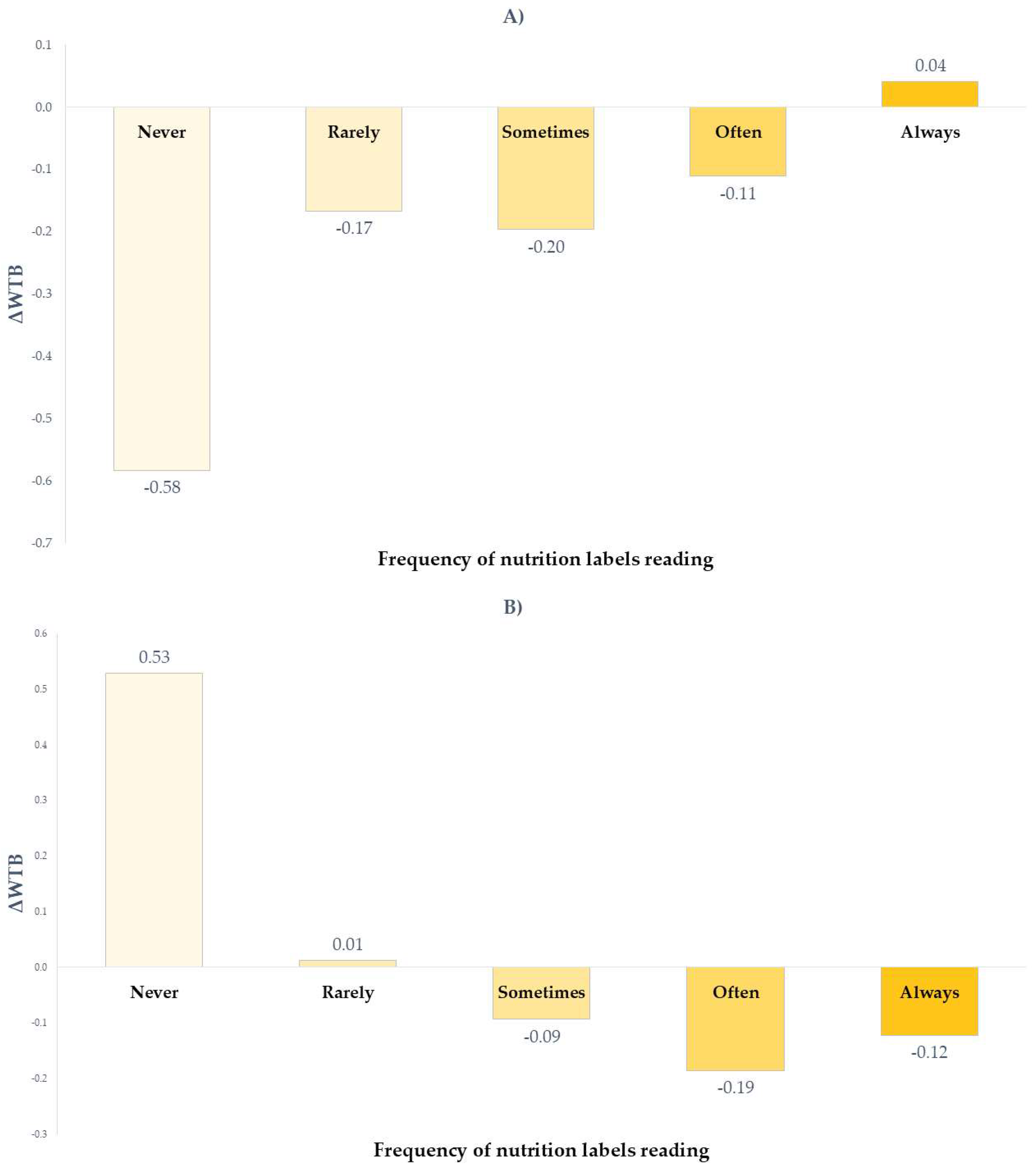

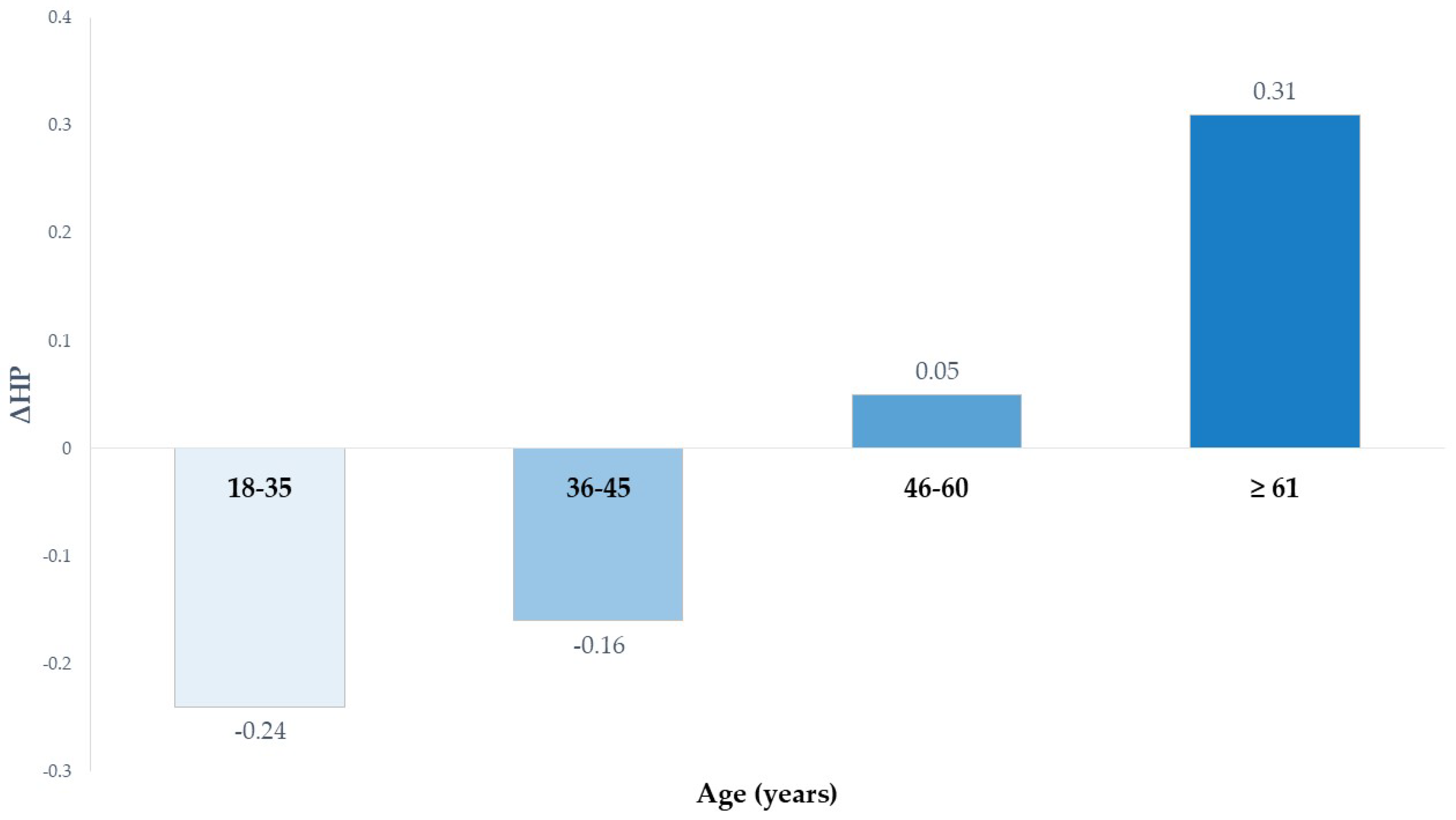

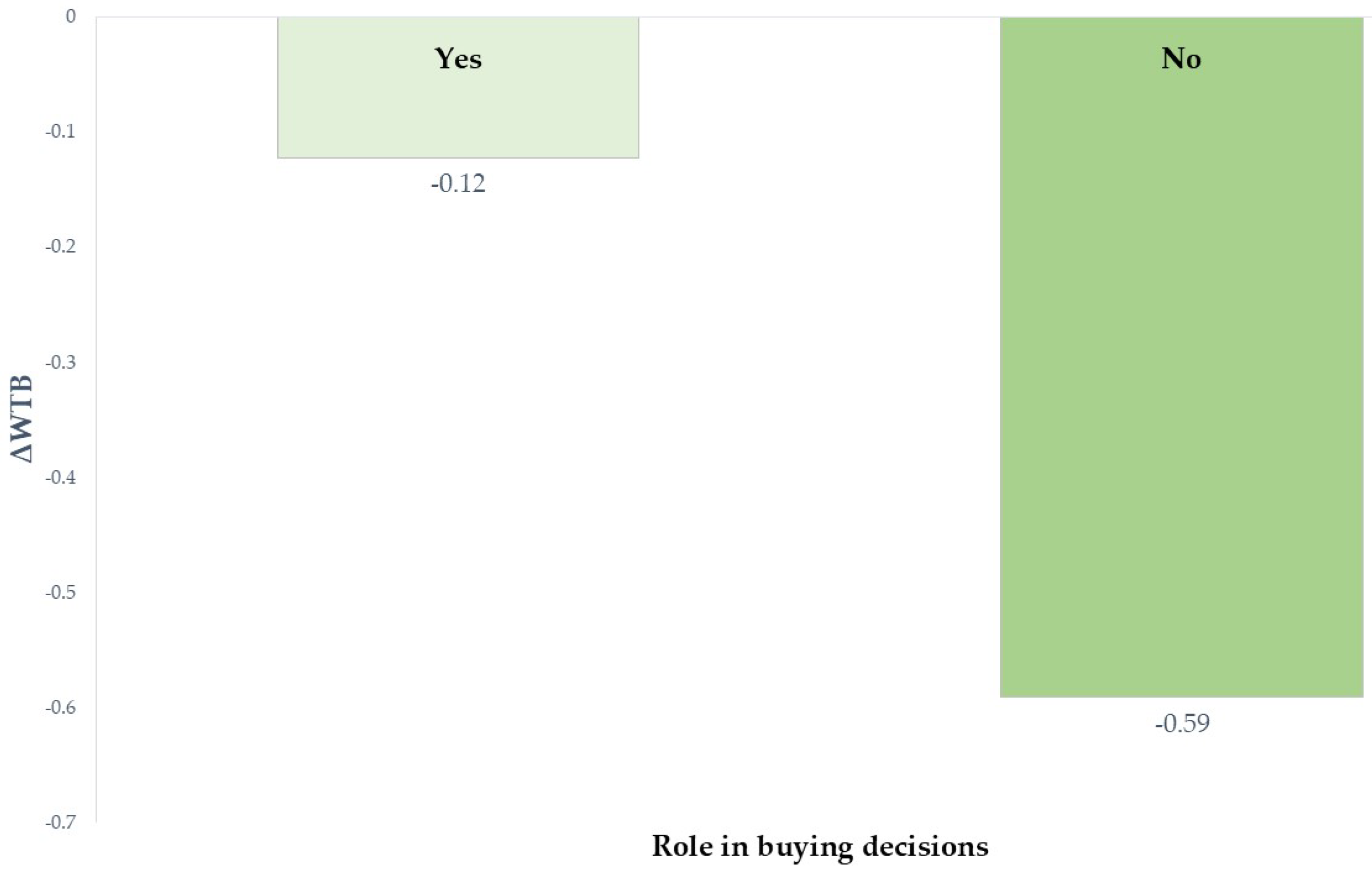

4.3. Predictors of Differences Among FoP Labels in Healthiness Perception and Willingness to Buy

4.4. Limitations and Future Outlook

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Haroon Sarwar, M.; Farhan Sarwar, M.; Khalid, M.T.; Sarwar, M. Effects of Eating the Balance Food and Diet to Protect Human Health and Prevent Diseases. Am. J. Circuits Syst. Signal Process. 2015, 1, 99–104. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Jawaldeh, A.; Rayner, M.; Julia, C.; Elmadfa, I.; Hammerich, A.; McColl, K. Improving Nutrition Information in the Eastern Mediterranean Region: Implementation of Front-of-Pack Nutrition Labelling. Nutrients 2020, 12, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braesco, V.; Drewnowski, A. Are Front-of-Pack Nutrition Labels Influencing Food Choices and Purchases, Diet Quality, and Modeled Health Outcomes? A Narrative Review of Four Systems. Nutrients 2023, 15, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Croker, H.; Packer, J.; Russell, S.J.; Stansfield, C.; Viner, R.M. Front of Pack Nutritional Labelling Schemes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Recent Evidence Relating to Objectively Measured Consumption and Purchasing. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2020, 33, 518–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, B.; Ng, S.H.; Carrad, A.; Pettigrew, S. The Potential Effectiveness of Nutrient Declarations and Nutrition and Health Claims for Improving Population Diets. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2024, 44, 441–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penzavecchia, C.; Todisco, P.; Muzzioli, L.; Poli, A.; Marangoni, F.; Poggiogalle, E.; Giusti, A.M.; Lenzi, A.; Pinto, A.; Donini, L.M. The Influence of Front-of-Pack Nutritional Labels on Eating and Purchasing Behaviors: A Narrative Review of the Literature. Eat. Weight Disord. 2022, 27, 3037–3051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberto, C.A.; Ng, S.W.; Ganderats-Fuentes, M.; Hammond, D.; Barquera, S.; Jauregui, A.; Taillie, L.S. The Influence of Front-of-Package Nutrition Labeling on Consumer Behavior and Product Reformulation. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2021, 41, 529–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Guiding Principles and Framework Manual for Front-of-Pack Labelling for Promoting Healthy Diet. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/guidingprinciples-labelling-promoting-healthydiet (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- Storcksdieck, G.B.S.; Marandola, G.; Ciriolo, E.; Van, B.R.; Wollgast, J. Front-of-Pack Nutrition Labelling Schemes: A Comprehensive Review; European Commission: Luxembourg, 2020; ISBN 9789276089711.

- Devaux, M.; Aldea, A.; Lerouge, A.; Vuik, S.; Cecchini, M. Establishing an EU-Wide Front-of-Pack Nutrition Label: Review of Options and Model-Based Evaluation. Obes. Rev. 2024, 25, e13719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Singh, A.; Bhattacharya, S. Front-of-Package Food Labeling and Noncommunicable Disease Prevention: A Comprehensive Bibliometric Analysis of Three Decades. Med. J. Armed Forces India 2024, 81, 126–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Report from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council Regarding the Use of Additional Forms of Expression and Presentation of the Nutrition Declaration; European Commission: Luxembourg, 2020.

- Afroza, U.; Abrar, A.K.; Nowar, A.; Sobhan, S.M.M.; Ide, N.; Choudhury, S.R. Global Overview of Government-Endorsed Nutrition Labeling Policies of Packaged Foods: A Document Review. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1426639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muzzioli, L.; Penzavecchia, C.; Donini, L.M.; Pinto, A. Are Front-of-Pack Labels a Health Policy Tool? Nutrients 2022, 14, 771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hafner, E.; Pravst, I. A Systematic Assessment of the Revised Nutri-Score Algorithm: Potentials for the Implementation of Front-of-Package Nutrition Labeling across Europe. Food Front. 2024, 5, 947–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feunekes, G.I.J.; Gortemaker, I.A.; Willems, A.A.; Lion, R.; van den Kommer, M. Front-of-Pack Nutrition Labelling: Testing Effectiveness of Different Nutrition Labelling Formats Front-of-Pack in Four European Countries. Appetite 2008, 50, 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acton, R.B.; Vanderlee, L.; Hammond, D. Influence of Front-of-Package Nutrition Labels on Beverage Healthiness Perceptions: Results from a Randomized Experiment. Prev. Med. 2018, 115, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundeberg, P.J.; Graham, D.J.; Mohr, G.S. Comparison of Two Front-of-Package Nutrition Labeling Schemes, and Their Explanation, on Consumers’ Perception of Product Healthfulness and Food Choice. Appetite 2018, 125, 548–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machín, L.; Cabrera, M.; Curutchet, M.R.; Martínez, J.; Giménez, A.; Ares, G. Consumer Perception of the Healthfulness of Ultra-Processed Products Featuring Different Front-of-Pack Nutrition Labeling Schemes. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2017, 49, 330–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muzzioli, L.; Scenna, D.; Frigerio, F.; Manuela, S.; Poggiogalle, E.; Giusti, A.M.; Pinto, A.; Migliaccio, S.; Lenzi, A.; Donini, L.M. Nutri-Score Effectiveness in Improving Consumers’ Nutrition Literacy, Food Choices, Health, and Healthy Eating Pattern Adherence: A Systematic Review. Nutrition 2025, 140, 112880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Włodarek, D.; Dobrowolski, H. Fantastic Foods and Where to Find Them—Advantages and Disadvantages of Nutri-Score in the Search for Healthier Food. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carruba, M.O.; Caretto, A.; De Lorenzo, A.; Fatati, G.; Ghiselli, A.; Lucchin, L.; Maffeis, C.; Malavazos, A.; Malfi, G.; Riva, E.; et al. Front-of-Pack (FOP) Labelling Systems to Improve the Quality of Nutrition Information to Prevent Obesity: NutrInform Battery vs Nutri-Score. Eat. Weight Disord. 2022, 27, 1575–1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donini, L.M.; Berry, E.M.; Folkvord, F.; Jansen, L.; Leroy, F.; Şimşek, Ö.; Fava, F.; Gobbetti, M.; Lenzi, A. Front-of-Pack Labels: “Directive” versus “Informative” Approaches. Nutrition 2023, 105, 111861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzù, M.F.; Romani, S.; Gambicorti, A. Effects on Consumers’ Subjective Understanding of a New Front-of-Pack Nutritional Label: A Study on Italian Consumers. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 72, 357–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baccelloni, A.; Giambarresi, A.; Mazzù, M.F. Effects on Consumers’ Subjective Understanding and Liking of Front-of-Pack Nutrition Labels: A Study on Slovenian and Dutch Consumers. Foods 2021, 10, 2958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castellini, G.; Bertorelli, S.; Carruba, M.; Donini, L.M.; Martini, D.; Graffigna, G. The Role of Nutri-Score and NutrInform Battery in Guiding the Food Choices of Consumers with Specific Nutritional Needs: A Controlled Study. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2024, 34, 2789–2798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fialon, M.; Serafini, M.; Galan, P.; Kesse-Guyot, E.; Touvier, M.; Deschasaux-Tanguy, M.; Sarda, B.; Hercberg, S.; Nabec, L.; Julia, C. Nutri-Score and NutrInform Battery: Effects on Performance and Preference in Italian Consumers. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, J.; Mazzù, M.F.; Baccelloni, A. A 20-Country Comparative Assessment of the Effectiveness of Nutri-Score vs. NutrInform Battery Front-of-Pack Nutritional Labels on Consumer Subjective Understanding and Liking. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martini, D.; Angelino, D.; Tucci, M.; La Bruna, E.; Pellegrini, N.; Del Bo’, C.; Riso, P. Can Front-of-Pack Labeling Encourage Food Reformulation? A Cross-Sectional Study on Packaged Bread. Foods 2024, 13, 3535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzù, M.F.; Romani, S.; Baccelloni, A.; Gambicorti, A. A Cross-Country Experimental Study on Consumers’ Subjective Understanding and Liking on Front-of-Pack Nutrition Labels. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 72, 833–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzù, M.F.; He, J.; Baccelloni, A. Unveiling the Impact of Front-of-Pack Nutritional Labels in Conflicting Nutrition Information—A Congruity Perspective on Olive Oil. Food Qual. Prefer. 2024, 118, 105202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fialon, M.; Nabec, L.; Julia, C. Legitimacy of Front-of-Pack Nutrition Labels: Controversy Over the Deployment of the Nutri-Score in Italy. Int. J. Health Policy Manag. 2022, 11, 2574–2587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricco, M.; Ranzieri, S.; Balzarini, F.; Vezzosi, L.; Marchesi, F.; Valente, M.; Peruzzi, S. Understanding of the Nutri-Score Front-of-Pack Label by Italian Medical Professionals and Its Effect on Food Choices: A Web-Based Study on Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices. Acta Biomed. 2022, 93, e2022042. [Google Scholar]

- Ministero delle Imprese e del Made in Italy NutrInform Battery. Available online: https://www.mimit.gov.it/it/impresa/competitivita-e-nuove-imprese/industria-alimentare/nutrinform-battery (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Egnell, M.; Talati, Z.; Galan, P.; Andreeva, V.A.; Vandevijvere, S.; Gombaud, M.; Dréano-Trécant, L.; Hercberg, S.; Pettigrew, S.; Julia, C. Correction to: Objective Understanding of the Nutri-Score Front-of-Pack Label by European Consumers and Its Effect on Food Choices: An Online Experimental Study. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2020, 17, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Julia, C.; Péneau, S.; Buscail, C.; Gonzalez, R.; Touvier, M.; Hercberg, S.; Kesse-Guyot, E. Perception of Different Formats of Front-of-Pack Nutrition Labels According to Sociodemographic, Lifestyle and Dietary Factors in a French Population: Cross-Sectional Study among the NutriNet-Santé Cohort Participants. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e016108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Méjean, C.; MacOuillard, P.; Péneau, S.; Hercberg, S.; Castetbon, K. Perception of Front-of-Pack Labels According to Social Characteristics, Nutritional Knowledge and Food Purchasing Habits. Public Health Nutr. 2013, 16, 392–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ducrot, P.; Méjean, C.; Julia, C.; Kesse-Guyot, E.; Touvier, M.; Fezeu, L.K.; Hercberg, S.; Péneau, S. Objective Understanding of Front-of-Package Nutrition Labels among Nutritionally at-Risk Individuals. Nutrients 2015, 7, 7106–7125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atchison, A.E.; Zickgraf, H.F. Orthorexia Nervosa and Eating Disorder Behaviors: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Appetite 2022, 177, 106134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cena, H.; Barthels, F.; Cuzzolaro, M.; Bratman, S.; Brytek-Matera, A.; Dunn, T.; Varga, M.; Missbach, B.; Donini, L.M. Definition and Diagnostic Criteria for Orthorexia Nervosa: A Narrative Review of the Literature; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; Volume 24, ISBN 0123456789. [Google Scholar]

- Pontillo, M.; Zanna, V.; Demaria, F.; Averna, R.; Di Vincenzo, C.; De Biase, M.; Di Luzio, M.; Foti, B.; Tata, M.C.; Vicari, S. Orthorexia Nervosa, Eating Disorders, and Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: A Selective Review of the Last Seven Years. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 6134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Fernandez, A.; Kuster-Boluda, I.; Vila-Lopez, N. Nutritional Information Labels and Health Claims to Promote Healthy Consumption. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2022, 37, 1650–1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, L.M.S.; Cassady, D.L. The Effects of Nutrition Knowledge on Food Label Use. A Review of the Literature. Appetite 2015, 92, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vainio, A. How Consumers of Meat-Based and Plant-Based Diets Attend to Scientific and Commercial Information Sources: Eating Motives, the Need for Cognition and Ability to Evaluate Information. Appetite 2019, 138, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onozaka, Y.; Melbye, E.L.; Skuland, A.V.; Hansen, H. Consumer Intentions to Buy Front-of-Pack Nutrition Labeled Food Products: The Moderating Effects of Personality Differences. J. Food Prod. Mark. 2014, 20, 390–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proi, M.; Cubero-Dudinskaya, E.; Gambelli, D.; Naspetti, S.; Zanoli, R. Bottom-up and Top-down Factors Influencing Consumer Responses to Food Labels: A Scoping Review of Eye-Tracking Studies. Agric. Food Econ. 2025, 13, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Giuseppe, R.; Di Castelnuovo, A.; Melegari, C.; De Lucia, F.; Santimone, I.; Sciarretta, A.; Barisciano, P.; Persichillo, M.; De Curtis, A.; Zito, F.; et al. Typical Breakfast Food Consumption and Risk Factors for Cardiovascular Disease in a Large Sample of Italian Adults. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2012, 22, 347–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, D.J.; Laska, M.N. Nutrition Label Use Partially Mediates the Relationship between Attitude toward Healthy Eating and Overall Dietary Quality among College Students. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2012, 112, 414–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miraballes, M.; Gámbaro, A. Influence of Images on the Evaluation of Jams Using Conjoint Analysis Combined with Check-All-That-Apply (CATA) Questions. J. Food Sci. 2018, 83, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Novara, C.; Pardini, S.; Pastore, M.; Mulatti, C. Ortoressia Nervosa: Un’indagine Del Costrutto e Delle Caratteristiche Psicometriche Della Versione Italiana Dell’Eating Habits Questionnaire-21 (EHQ-21). Psicoter. Cogn. E Comport. 2017, 23, 291–316. [Google Scholar]

- Gleaves, D.H.; Graham, E.C.; Ambwani, S. Measuring “Orthorexia”: Development of the Eating Habits Questionnaire. Int. J. Educ. Psychol. Assess. 2013, 12, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Asioli, D.; Jaeger, S.R. Online Consumer Research: More Attention Needs to Be given to Data Quality. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2025, 63, 101307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaeger, S.R.; Cardello, A.V. Factors Affecting Data Quality of Online Questionnaires: Issues and Metrics for Sensory and Consumer Research. Food Qual. Prefer. 2022, 102, 104676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gravesande, J.; Richardson, J.; Griffith, L.; Scott, F. Test-Retest Reliability, Internal Consistency, Construct Validity and Factor Structure of a Falls Risk Perception Questionnaire in Older Adults with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Prospective Cohort Study. Arch. Physiother. 2019, 9, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohajan, H.K. Two Criteria for Good Measurements in Research: Validity and Reliability. Ann. Spiru Haret Univ. Econ. Ser. 2017, 17, 59–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratman, S. Health Food Junkie. Yoga. Available online: https://www.beyondveg.com/bratman-s/hfj/hf-junkie-1a.shtml (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Harrison, A.; Tchanturia, K.; Naumann, U.; Treasure, J. Social Emotional Functioning and Cognitive Styles in Eating Disorders. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 2012, 51, 261–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheshire, A.; Berry, M.; Fixsen, A. What Are the Key Features of Orthorexia Nervosa and Influences on Its Development? A Qualitative Investigation. Appetite 2020, 155, 104798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCarthy, M.B.; Collins, A.M.; Flaherty, S.J.; McCarthy, S.N. Healthy Eating Habit: A Role for Goals, Identity, and Self-Control? Psychol. Mark. 2017, 34, 772–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, L.M.S. Quantitative Information Processing of Nutrition Facts Panels. Br. Food J. 2014, 116, 1205–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fialon, M.; Egnell, M.; Talati, Z.; Galan, P.; Dréano-Trécant, L.; Touvier, M.; Pettigrew, S.; Hercberg, S.; Julia, C. Effectiveness of Different Front-of-Pack Nutrition Labels among Italian Consumers: Results from an Online Randomized Controlled Trial. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crosetto, P.; Lacroix, A.; Muller, L.; Ruffieux, B. Nutritional and Economic Impact of Five Alternative Front-of-Pack Nutritional Labels: Experimental Evidence. Eur. Rev. Agric. Econ. 2020, 47, 785–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Temmerman, J.; Heeremans, E.; Slabbinck, H.; Vermeir, I. The Impact of the Nutri-Score Nutrition Label on Perceived Healthiness and Purchase Intentions. Appetite 2021, 157, 104995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinton, C.; Cremonese, V.; Pavy, A.; Guillamet, K. The Nutri-Score’s Impact on the Consumer Experience. In Proceedings of the 15TH PANGBORN SENSORY SCIENCE SYMPOSIUM—MEETING NEW CHALLENGES IN A CHANGING WORLD (PSSS 2023): U02, Nantes, France, 20–24 August 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Tiboldo, G.; Castellari, E.; Moro, D. The Distributional Implications of Health Taxes: A Case Study on the Italian Sugar Tax. Food Policy 2024, 126, 102671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco-Arellano, B.; Vanderlee, L.; Ahmed, M.; Oh, A.; L’Abbé, M. Influence of Front-of-Pack Labelling and Regulated Nutrition Claims on Consumers’ Perceptions of Product Healthfulness and Purchase Intentions: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Appetite 2020, 149, 104629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarborough, P.; Matthews, A.; Eyles, H.; Kaur, A.; Hodgkins, C.; Raats, M.M.; Rayner, M. Reds Are More Important than Greens: How UK Supermarket Shoppers Use the Different Information on a Traffic Light Nutrition Label in a Choice Experiment. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2015, 12, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jáuregui, A.; White, C.M.; Vanderlee, L.; Hall, M.G.; Contreras-Manzano, A.; Nieto, C.; Sacks, G.; Thrasher, J.F.; Hammond, D.; Barquera, S. Impact of Front-of-Pack Labels on the Perceived Healthfulness of a Sweetened Fruit Drink: A Randomised Experiment in Five Countries. Public Health Nutr. 2022, 25, 1094–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silayoi, P.; Speece, M. Packaging and Purchase Decisions: An Exploratory Study on the Impact of Involvement Level and Time Pressure. Br. Food J. 2004, 106, 607–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gianfredi, V.; Nucci, D.; Pennisi, F.; Maggi, S.; Veronese, N.; Soysal, P. Aging, Longevity, and Healthy Aging: The Public Health Approach. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2025, 37, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettigrew, S.; Pescud, M.; Donovan, R.J. Older People’s Diet-Related Beliefs and Behaviours: Intervention Implications. Nutr. Diet. 2012, 69, 260–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrúa, A.; MacHín, L.; Curutchet, M.R.; Martínez, J.; Antúnez, L.; Alcaire, F.; Giménez, A.; Ares, G. Warnings as a Directive Front-of-Pack Nutrition Labelling Scheme: Comparison with the Guideline Daily Amount and Traffic-Light Systems. Public Health Nutr. 2017, 20, 2308–2317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramprabha, K. Consumer Shopping Behaviour and the Role of Women in Shopping—A Literature Review. J. Soc. Sci. Manag. 2017, 7, 50–63. [Google Scholar]

| Product Category | Front-of-Pack Label | Nutritional Quality | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High | Medium | Low | ||

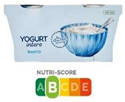

| Yoghurt | Nutri-Score |  |  |  |

| NutrInform Battery |  |  |  | |

| Fruit jam | Nutri-Score |  |  |  |

| NutrInform Battery |  |  |  | |

| Variable | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Female | 309 | 70.87 |

| Male | 124 | 28.44 |

| Other | 1 | 0.23 |

| I prefer not to declare it | 2 | 0.46 |

| Age | ||

| 18–35 | 217 | 49.77 |

| 36–45 | 76 | 17.43 |

| 46–60 | 97 | 22.25 |

| ≥61 | 46 | 10.55 |

| Education level | ||

| Elementary school diploma | 1 | 0.23 |

| Middle school diploma | 7 | 1.61 |

| High school diploma (or equivalent) | 96 | 22.02 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 90 | 20.64 |

| Postgraduate degree (master’s, doctorate) | 242 | 55.50 |

| Area of residence * | ||

| Northwest | 278 | 64.80 |

| Northeast | 48 | 11.19 |

| Center | 24 | 5.59 |

| South | 70 | 16.32 |

| Island | 9 | 2.10 |

| Diet | ||

| Omnivorous | 338 | 77.52 |

| Flexitarian | 70 | 16.06 |

| Vegetarian | 25 | 5.73 |

| Vegan | 3 | 0.69 |

| Role in buying decisions | ||

| I am primarily responsible for these purchases | 194 | 44.50 |

| I am not involved in the decision at all | 6 | 1.38 |

| I make suggestions but decisions are made by other family members | 50 | 11.47 |

| I share the responsibility for making these purchases | 186 | 42.66 |

| Reading of nutritional labels | ||

| Never | 42 | 9.63 |

| Rarely | 92 | 21.10 |

| Sometimes | 113 | 25.92 |

| Often | 140 | 32.11 |

| Always | 49 | 11.24 |

| Product Category | Nutritional Quality | HP | WTB | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NS | NIB | p-Value * | NS | NIB | p-Value * | ||

| Yoghurt | High | 5.6 ± 1.5 a | 5.3 ± 1.6 a | 0.004 | 5.1 ± 1.8 a | 4.9 ± 1.9 a | ns |

| Medium | 5.2 ± 1.4 b | 4.8 ± 1.6 b | 0.001 | 5.0 ± 1.7 a | 4.7 ± 1.8 a | 0.019 | |

| Low | 3.7 ± 1.4 c | 3.6 ± 1.6 c | ns | 3.8 ± 1.8 b | 3.7 ± 2.0 b | ns | |

| p-value ** | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||

| Product Category | Nutritional Quality | HP | WTB | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NS | NIB | p-Value * | NS | NIB | p-Value * | ||

| Fruit jam | High | 5.0 ± 1.6 a | 4.9 ± 1.5 a | ns | 4.9 ± 1.8 a | 4.7 ± 1.8 a | ns |

| Medium | 4.1 ± 1.3 b | 4.4 ± 1.5 b | 0.004 | 4.3 ± 1.7 b | 4.5 ± 1.8 a | 0.033 | |

| Low | 3.5 ± 1.5 c | 4.1 ± 1.5 c | <0.0001 | 3.6 ± 1.8 c | 4.1 ± 1.8 b | <0.0001 | |

| p-value ** | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cela, N.; Quintiero, F.; Ferraris, C.; Torri, L. Directive vs. Reductive Front-of-Pack Labels: Differences in Italian Consumers’ Responses to the Nutri-Score and the NutrInform Battery. Foods 2025, 14, 4033. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234033

Cela N, Quintiero F, Ferraris C, Torri L. Directive vs. Reductive Front-of-Pack Labels: Differences in Italian Consumers’ Responses to the Nutri-Score and the NutrInform Battery. Foods. 2025; 14(23):4033. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234033

Chicago/Turabian StyleCela, Nazarena, Federica Quintiero, Cinzia Ferraris, and Luisa Torri. 2025. "Directive vs. Reductive Front-of-Pack Labels: Differences in Italian Consumers’ Responses to the Nutri-Score and the NutrInform Battery" Foods 14, no. 23: 4033. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234033

APA StyleCela, N., Quintiero, F., Ferraris, C., & Torri, L. (2025). Directive vs. Reductive Front-of-Pack Labels: Differences in Italian Consumers’ Responses to the Nutri-Score and the NutrInform Battery. Foods, 14(23), 4033. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234033