Abstract

This study analyzes the temporal evolution of citations received by academic articles in the field of micro, small, and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and internationalization processes, with the aim of identifying patterns of growth and decline in scientific visibility. Based on a dataset of 1936 articles retrieved from Scopus, we constructed an article–year panel that enabled the application of multiple statistical approaches. Discrete-time survival models showed that the annual probability of receiving at least one citation is initially low, increases slightly until the fifth year, and then declines progressively thereafter. Negative binomial regression confirmed significant growth during the first five years, followed by a slowdown. Kaplan–Meier estimations reinforced this finding by showing that the cumulative proportion of articles receiving their first citation within a decade remains limited. These results confirm that citation dynamics are nonlinear and subject to early obsolescence, with most visibility concentrated in the short term. Importantly, this temporal bias in indexing and evaluation systems disproportionately favors recent publications while undervaluing older but still influential research. Such structural bias has profound implications for visibility and equity in scholarly communication, especially for disciplines and regions where citation cycles are longer. The findings thus validate the study’s propositions: first, that citation growth slows significantly after the fifth year, and second, that this slowdown represents a structural bias that amplifies inequities in research evaluation.

1. Introduction

Bibliometrics has established itself as a fundamental discipline for evaluating scientific production. By applying quantitative techniques to patterns of publication, collaboration, and knowledge flows, it enables not only the measurement of productivity but also the assessment of academic impact and visibility. In recent decades, bibliometric approaches have been widely adopted by governments, universities, and funding agencies to inform science policy, allocate resources, and monitor research performance (Passas, 2024; Hassan & Duarte, 2024). Their growing popularity reflects the promise of objective, data-driven indicators in the governance of scientific activity.

Among bibliometric indicators, citation counts are perhaps the most widely used. They are commonly regarded as an ostensibly objective signal of academic recognition, since they capture the degree to which a publication influences subsequent research (Kousha & Thelwall, 2024). However, their validity as indicators of quality has been repeatedly questioned. Citations are vulnerable to distortions caused by excessive self-citation, coercive referencing practices, editorial bias, and the overrepresentation of specific disciplines (Põder, 2022; Worrall & Cohn, 2023). Moreover, citations may reflect strategic visibility rather than genuine intellectual influence, being shaped by factors such as language of publication, institutional reputation, or international collaboration (Loui & Fiala, 2024; Wang et al., 2025). These issues highlight that citation counts, while informative, cannot be treated as neutral or universal measures of scholarly quality.

In this study, the notion of bias is understood not as a methodological artifact derived from measurement models, but as a systemic distortion rooted in institutional and evaluative mechanisms that govern the visibility of scientific work. This form of bias arises when citation and indexing systems—through language dominance, database coverage, or evaluation time frames—unequally distribute scholarly attention across disciplines, regions, and publication types. In contrast, methodological bias refers to distortions caused by statistical or data-collection processes, which are not the focus here. Accordingly, the term bias throughout this paper denotes a structural imbalance in how academic recognition is produced and reproduced within the scientific system.

A particularly relevant dimension of citation behavior is its temporal dynamic. Citations are cumulative and unevenly distributed across an article’s life span. Research consistently shows that citations typically follow a trajectory characterized by an early phase of rapid growth, followed by stabilization and eventual decline—a phenomenon widely referred to as the aging effect (Hu et al., 2021). This pattern, however, is not uniform across disciplines. In fast-moving areas, such as biomedicine, the decline is more pronounced and rapid, whereas in theoretical or foundational fields, such as mathematics, articles can remain relevant for decades (Eom & Fortunato, 2024; Kousha & Thelwall, 2024). These disciplinary differences underscore that the life cycle of citations is context-dependent and influenced by the pace of knowledge renewal in each field.

Despite advances in modeling citation dynamics—such as log-normal distributions, stochastic models, and survival analysis (Yasui & Nakano, 2022; Giordano et al., 2025)—there is still a lack of empirical research explicitly testing critical temporal thresholds in citation trajectories. For example, while it is often assumed that articles enjoy their peak visibility in the first five years, relatively few studies have statistically validated this breakpoint. Furthermore, the implications of such temporal thresholds for equity in research evaluation have not been sufficiently addressed.

This gap is particularly relevant in light of growing concerns about bias in indexing and visibility. Evaluation systems that rely on short citation windows (e.g., two to five years) inherently favor immediacy, disproportionately rewarding recent publications while undervaluing older research that may require more extended gestation periods before achieving recognition. Such practices introduce a temporal bias into scholarly communication, reinforcing inequities across disciplines, languages, and regions. Disciplines with slower citation dynamics, such as the social sciences, are structurally disadvantaged, while research from emerging economies often faces delayed international visibility due to limited networks and linguistic barriers. These patterns suggest that the temporal dimension of citations is not only a methodological challenge but also a mechanism of systemic inequity in the global academic system (Põder, 2022; Kousha & Thelwall, 2024).

Understanding when an article reaches its peak visibility is not merely descriptive but critical to explaining how scientific attention evolves and how evaluation systems respond to it. If these temporal dynamics are ignored, research assessment frameworks may inadvertently distort the recognition of scholarly influence—rewarding immediacy over longevity, privileging disciplines with faster citation cycles, and marginalizing fields or regions where knowledge diffusion occurs more slowly. Consequently, identifying temporal thresholds in citation trajectories becomes essential for understanding how structural biases in visibility affect the fairness, efficiency, and cumulative growth of the scientific system.

In this context, the present study contributes to ongoing debates by analyzing the life cycle of citations in articles focused on small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and internationalization processes.

SMEs constitute the majority of businesses worldwide and have become a central focus of research in management and economics due to their role in employment generation, innovation, and international competitiveness. Recent studies emphasize that SME internationalization is not only conditioned by market access but also by the development of dynamic capabilities that enable firms to adapt and grow in uncertain environments (Fredrich et al., 2022). At the same time, digitalization has emerged as a critical enabler for overcoming business model challenges in global expansion, facilitating resource efficiency, and accelerating knowledge flows (Reim et al., 2022). In Latin America, these dynamics are particularly relevant as SMEs represent the backbone of national economies and face unique structural barriers to scaling internationally (Martínez et al., 2024; Gonzalez-Tamayo et al., 2023). This corpus, therefore, provides a fertile ground for examining citation dynamics in the administrative sciences, where the visibility of SME-related research reflects not only scientific interest but also broader economic and social imperatives.

Drawing on a dataset of 1936 Scopus-indexed articles published between 1990 and 2025, this study employs a multi-method strategy to investigate whether the assumption of linear citation growth holds or whether temporal thresholds exist that alter citation trajectories. The methodology includes quadratic and segmented regression models, discrete-time survival analysis, negative binomial regressions, and Kaplan–Meier estimations. This approach allows us to capture both global trajectories and structural breakpoints in citation growth, providing a robust empirical test of the hypothesis that citation visibility peaks early and declines thereafter.

By framing these dynamics as a form of bias in citation visibility, the study goes beyond technical modeling to address broader issues of equity in scholarly communication. The results are interpreted not only as evidence of nonlinearity in citation life cycles but also as indicators of structural biases embedded in indexing and evaluation systems. In doing so, this work aligns directly with the theme of the Special Issue Bias in Indexing: Effects on Visibility and Equity, contributing empirical evidence to current debates on fairness and inclusiveness in research evaluation.

Building on these theoretical and methodological considerations, this study is designed with two main objectives.

Objective 1. To empirically analyze the temporal dynamics of citation accumulation in SME and internationalization research, we test whether the relationship between article age and citation counts follows a strictly linear trajectory or presents structural thresholds instead.

Objective 2. To interpret these temporal dynamics not merely as technical patterns of aging, but as manifestations of structural bias in research visibility that have implications for equity in scholarly communication.

From these objectives, we advance the following propositions:

- Proposition 1. Citation counts increase significantly during the early years of an article’s life but experience a statistically detectable slowdown after approximately the fifth year, reflecting a breakpoint in citation dynamics.

- Proposition 2. This breakpoint represents more than a methodological artifact: it constitutes a form of temporal bias that privileges recent publications while systematically undervaluing older contributions, thereby exacerbating inequities across disciplines, languages, and regions.

Accordingly, the contribution of this study is twofold. Theoretically, it offers a robust empirical validation of temporal thresholds in citation life cycles, reframing them as mechanisms of bias in visibility. Practically, it underscores the need to reconsider current indexing and evaluation policies, which rely heavily on short citation windows, and to develop more equitable indicators that recognize both immediate and delayed scholarly impact.

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Bibliometric Approaches to Citation Dynamics

Bibliometrics, understood as the set of quantitative techniques that enable the measurement and analysis of scientific production, has evolved over the past decades to become an essential discipline for understanding the dynamics of knowledge. Its value lies in its ability to transform raw data into objective indicators that guide the evaluation of research, identify thematic trends, and assess academic impact (Passas, 2024). In a context of increasing pressure for productivity and the internationalization of science, bibliometric indicators have been adopted by governments, universities, and funding agencies as key tools for decision-making (You et al., 2024).

A particularly relevant aspect of bibliometrics is its capacity to study collaboration networks and the diffusion of ideas, which enables the identification not only of who produces knowledge but also how this knowledge is disseminated within academic communities. These tools have facilitated the analysis of the so-called “science of science,” that is, the reflexive understanding of how knowledge is constructed and validated across different fields (Kousha & Thelwall, 2024).

However, despite methodological advances, approaches that focus primarily on simple indicators—such as raw citation counts—still predominate, and these do not always capture the complexity of the processes involved in constructing and consolidating knowledge (Põder, 2022). This gap highlights the need for studies that incorporate not only the total number of citations but also their distribution and temporal evolution.

Citation analysis has historically been regarded as a proxy for scientific impact, insofar as it represents the extent to which an article influences subsequent research. Nevertheless, citations are not only cumulative but also follow a temporal pattern: an article does not receive the same volume of citations throughout its academic life. Instead, there are distinct stages of rise, stabilization, and eventual decline, which correspond to a phenomenon commonly referred to as the “aging effect” (Hu et al., 2021).

In general, studies show that articles tend to accumulate a significant number of citations during the first years after publication, reaching a “peak” of visibility. Subsequently, the rate of citation growth decreases, either because of the emergence of newer literature or the obsolescence of the knowledge presented (Eom & Fortunato, 2024). This phenomenon varies across disciplines: while in fast-moving fields, such as biomedicine, the decline is more pronounced, in theoretical areas, such as mathematics, the relevance of publications may persist for much longer (Kousha & Thelwall, 2024).

Biases associated with citation analysis must also be considered, including factors such as self-citation, language of publication, institutional reputation, and open access, which can significantly influence the number of citations a work receives (Põder, 2022). For this reason, temporal analyses should not be restricted to absolute figures but should also account for the life cycle of publications and the contextual factors that influence their citation patterns.

To more accurately capture the temporal dynamics of citations, several models have been proposed in recent years. One of the most robust approaches is that of Hu et al. (2021), who applied a hypergraph network model that explicitly incorporates the aging effect. Their results show that the probability of an article being cited decreases exponentially over time, providing empirical validation of a consistent pattern of scientific attention loss. Using databases such as APS and DBLP, the authors demonstrated that, after an initial period of growth, articles tend to lose attractiveness for subsequent publications.

Complementarily, Yasui and Nakano (2022) developed a stochastic generative model for academic citation networks that incorporates an aging distribution based on the inverse Gaussian. This model predicts the probability that an article will be cited as a function of the time elapsed since its publication, achieving robust validation with data from Web of Science and arXiv. Its main contribution lies in showing that citation dynamics are not random but instead follow statistical patterns that can be anticipated.

Eom and Fortunato (2024) argue that citation distributions follow adjusted log-normal forms, in which three key parameters converge: the initial attractiveness of the article (fitness), the immediacy with which it begins to be cited (immediacy), and its academic longevity (longevity). This framework helps explain why particular works maintain a steady flow of citations over time, while others fall into early obsolescence.

In recent studies on citation dynamics, a variety of statistical methodologies have been applied to capture both the temporal dimension and the heterogeneity of citation patterns. For example, discrete-time survival models with Kaplan–Meier estimators have been employed to model the time to first citation in academic publications, thereby facilitating the analysis of citation “immediacy” and its distribution over time (Giordano et al., 2025). In parallel, count regression models such as the Negative Binomial have been used to address the common issue of overdispersion in citation counts and to estimate average citation rates adjusted for article age (Dorta-González & Gómez-Déniz, 2025). Moreover, the application of segmented or piecewise models with explicit breakpoints in slope—while traditionally more common in duration analysis—is gaining traction in studies that seek to identify critical points in citation dynamics (Suresh et al., 2022). These methodological approaches strengthen the robustness of our analysis by complementing the observed patterns in time-to-first-citation risk, expected counts by age, and potential breakpoints in growth trajectories.

On a more applied level, recent studies in Information Science demonstrate that interdisciplinarity can delay citation aging by enabling articles to remain relevant across diverse scientific communities (Yang et al., 2024). This finding suggests that citation dynamics depend not only on time but also on a work’s capacity to connect different domains of knowledge.

2.2. Fairness and Structural Bias in Scholarly Communication

Beyond methodological considerations, it is equally important to acknowledge the systemic conditions that influence citation visibility. Major databases such as Scopus and Web of Science do not provide neutral coverage of global scientific output. Their inclusion policies privilege journals published in English, located in the Global North, or embedded within dominant disciplinary hierarchies. This creates structural inequities in visibility, where research from emerging economies or non-English-speaking contexts is underrepresented, regardless of quality (Põder, 2022; Kousha & Thelwall, 2024).

These inequities also have a temporal dimension. Evaluation systems that prioritize short citation windows (two to five years) inherently reward immediacy over long-term influence, reinforcing what may be called a temporal bias in scholarly communication. Articles that require more extended periods to gain recognition—whether due to disciplinary pace, linguistic barriers, or limited indexing visibility—are systematically undervalued. This bias disproportionately affects fields such as the social sciences and regions outside core scientific hubs, amplifying inequities in how academic contributions are measured and recognized.

Concerns about fairness and visibility have been extensively addressed in Science and Technology Studies (STS). Merton (1968) conceptualized the “Matthew Effect,” describing how recognition in science accumulates disproportionately among already prominent researchers, creating cumulative advantage and systemic inequity. Bourdieu (1975) later framed these mechanisms as forms of symbolic and scientific capital, emphasizing how institutional prestige structures academic hierarchies. Latour (1987) showed that authority in science emerges from networks of citation and replication that both stabilize knowledge and concentrate power. More recent contributions by Lamont (2010) and Fricker (2007) emphasize that evaluation and peer review are not purely technical procedures but sociocultural practices shaped by norms of credibility, justice, and epistemic inclusion. From this perspective, biases in citation and indexing systems can be interpreted as manifestations of epistemic injustice within global knowledge networks, reinforcing asymmetries in whose work is recognized, cited, and institutionalized.

Recent critical perspectives in data ethics also emphasize that inequities in visibility are embedded in the design of information systems themselves. As D’Ignazio and Klein (2020) argue, data infrastructures and metrics often reproduce social hierarchies by privileging dominant epistemologies and excluding alternative forms of knowledge production. This view reinforces the need to analyze citation bias not only as an evaluative artifact but as a manifestation of deeper structural asymmetries in how data and recognition are organized.

Extending this argument, Biagioli and Lippman (2020) demonstrate that the contemporary obsession with quantitative evaluation—impact factors, h-indexes, and citation metrics—has transformed scholarly recognition into a performative economy of visibility. This “gaming of metrics” further institutionalizes systemic bias, as researchers and institutions adapt their behavior to align with evaluative norms that privilege immediacy and conformity over substantive intellectual contribution.

2.3. Integrating Temporal Dynamics and Systemic Bias: Conceptual Model of the Study

By integrating the notions of aging effects, systemic bias, and temporal inequities, the present study situates citation dynamics within broader debates on fairness in scholarly communication. This framework recognizes that statistical regularities in citation aging are inseparable from the institutional and cognitive structures that govern academic visibility.

At the cognitive level, the accumulation and eventual decline of citations reflect the natural limits of scholarly attention. Once a topic reaches saturation, researchers tend to redirect their focus toward newer frameworks or trending keywords—a process known as attention decay. This self-reinforcing renewal cycle explains why the majority of citations are concentrated in the first years of publication, shaping what appears to be an intrinsic “aging effect”.

At the institutional level, this cognitive pattern is amplified by evaluation systems and database algorithms that codify recency as a proxy for relevance. Short citation windows used in journal metrics, funding assessments, and ranking exercises institutionalize the preference for immediacy, transforming a behavioral tendency into a structural norm. This interaction between cognitive attention and evaluative design generates a form of temporal bias, in which articles that mature slowly or circulate across less visible linguistic or disciplinary spaces become systematically undervalued.

At the methodological level, bibliometric modeling allows these intertwined dynamics to be detected and measured. The use of quadratic and segmented regressions, count models, and survival analysis provides the analytical precision to identify breakpoints—particularly the five-year slowdown—where systemic and cognitive factors intersect. Thus, the empirical design of this study operationalizes the theoretical synthesis proposed above: the temporal evolution of citations is analyzed not only as a statistical phenomenon but as an indicator of deeper asymmetries in the production and recognition of knowledge.

Taken together, this conceptual model provides a unified lens for interpreting the results presented later in this article. It highlights that the observed turning point in citation trajectories—around the fifth year—embodies both a cognitive saturation process and an institutional bias embedded in evaluative practices. Recognizing this dual nature is essential for developing fairer and more context-sensitive indicators of scientific visibility and impact.

3. Materials and Methods

The methodological strategy adopted in this study was designed to provide a comprehensive and rigorous examination of the temporal dynamics of scientific citations. To this end, we combined descriptive statistics, regression-based models, and survival analysis techniques in order to capture both the general trajectory of citation accumulation and potential breakpoints in its evolution. The methodological design unfolded in three stages: (i) definition and construction of the dataset through a structured Scopus search and subsequent panel transformation; (ii) application of statistical models—including quadratic and segmented regressions, negative binomial counts, and discrete-time survival analysis—to test the central hypothesis of accelerated growth followed by slowdown; and (iii) complementary robustness checks and contextual interpretation of the findings. This multi-method approach ensures not only empirical validity but also analytical precision in identifying the limits of citation influence and their implications for academic evaluation.

3.1. Study Design and Data Source

The study began with a Scopus search using the following query:

TITLE-ABS-KEY ( management ) AND ( LIMIT-TO ( SUBJAREA , “BUSI” ) OR EXCLUDE ( SUBJAREA , “ENGI” ) OR EXCLUDE ( SUBJAREA , “ARTS” ) OR EXCLUDE ( SUBJAREA , “MEDI” ) OR EXCLUDE ( SUBJAREA , “NURS” ) OR EXCLUDE ( SUBJAREA , “EART” ) OR EXCLUDE ( SUBJAREA , “BIOC” ) OR EXCLUDE ( SUBJAREA , “PHYS” ) OR EXCLUDE ( SUBJAREA , “PHAR” ) OR EXCLUDE ( SUBJAREA , “IMMU” ) ) AND ( LIMIT-TO ( DOCTYPE , “ar” ) ) AND ( EXCLUDE ( EXACTKEYWORD , “China” ) OR EXCLUDE ( EXACTKEYWORD , “Article” ) OR EXCLUDE ( EXACTKEYWORD , “India” ) OR EXCLUDE ( EXACTKEYWORD , “United Kingdom” ) OR EXCLUDE ( EXACTKEYWORD , “Australia” ) OR EXCLUDE ( EXACTKEYWORD , “Europe” ) OR EXCLUDE ( EXACTKEYWORD , “Eurasia” ) )

This initial query aimed to analyze citations related to management within the social sciences field. To narrow the scope, several keywords not directly associated with administrative sciences were excluded. Nevertheless, this query yielded a total of 228,428 articles, while Scopus sets a maximum limit of 2000 records for data extraction. This restriction implied a fragmentation of the sample, which could have introduced bias into the study results. Under these constraints, and considering the importance of SMEs and internationalization activities in the global economy, the original search equation was modified and reoriented toward this new scenario, resulting in the following formulation:

TITLE-ABS-KEY ( SME ) AND INTERNATIONALIZATION AND ( EXCLUDE ( EXACTKEYWORD , “Italy” ) OR EXCLUDE ( EXACTKEYWORD , “Poland” ) OR EXCLUDE ( EXACTKEYWORD , “Finland” ) OR EXCLUDE ( EXACTKEYWORD , “Pakistan” ) OR EXCLUDE ( EXACTKEYWORD , “Spain” ) OR EXCLUDE ( EXACTKEYWORD , “Africa” ) OR EXCLUDE ( EXACTKEYWORD , “New Zealand” ) OR EXCLUDE ( EXACTKEYWORD , “Vietnam” ) OR EXCLUDE ( EXACTKEYWORD , “Indonesia” ) OR EXCLUDE ( EXACTKEYWORD , “India” ) OR EXCLUDE ( EXACTKEYWORD , “United Kingdom” ) OR EXCLUDE ( EXACTKEYWORD , “Europe” ) OR EXCLUDE ( EXACTKEYWORD , “Ghana” ) OR EXCLUDE ( EXACTKEYWORD , “Malaysia” ) OR EXCLUDE ( EXACTKEYWORD , “China” ) ) AND ( LIMIT-TO ( DOCTYPE , “ar” ) ) AND ( LIMIT-TO ( PUBSTAGE , “final” ) ) AND ( LIMIT-TO ( SUBJAREA , “BUSI” ) OR LIMIT-TO ( SUBJAREA , “ECON” ) OR LIMIT-TO ( SUBJAREA , “SOCI” ) OR LIMIT-TO ( SUBJAREA , “DECI” ) )

Additionally, for the reasons already mentioned, further exclusions were applied. This process yielded a total of 2135 articles, of which 197 had received no citations and 2 contained incomplete metadata. After cleaning and validation, the final dataset comprised 1936 articles, which were used consistently across all analyses. The time span of these articles ranged from 1990 to 2025. In the initial matrix, each row represented an article, and each column represented a year. All citations received by articles published prior to the year 2000 were aggregated into a single column.

To ensure methodological transparency, several inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied. Only peer-reviewed journal articles (doctype: ar) were included, while reviews, conference papers, book chapters, and editorials were excluded to maintain consistency across document types. The language filter was limited to English, reflecting Scopus’s predominant indexing coverage and ensuring the comparability of citation patterns. The dataset was further restricted to final-stage publications (pubstage: final) within the subject areas of Business, Economics, Decision Sciences, and Social Sciences, as these domains directly relate to SME and internationalization research. No filters were applied regarding journal quartile or open-access status, as the study sought to capture general citation dynamics rather than quality differentials. The country and keyword exclusions—focused mainly on overrepresented regions such as China, India, the United Kingdom, and continental Europe—were applied iteratively to prevent dominance by highly prolific contexts and to achieve a more balanced representation of diverse research origins. After data cleaning and validation, the final corpus comprised 1936 Scopus-indexed articles published between 1990 and 2025, yielding 17,340 valid article–year observations. Nonetheless, reliance on a single database (Scopus) and the application of language and regional filters may introduce geographical or linguistic bias, which should be considered when interpreting the results.

3.2. Data Transformation and Structure

To facilitate longitudinal analysis, the dataset was restructured into a panel format, with each row corresponding to a specific article in a given citation year. In other words, a single article appeared in as many rows as the number of years elapsed since its publication up to the reference date. The resulting columns are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Structure of the Transformed Matrix.

This procedure resulted in a panel comprising 17,340 valid article–year observations.

Data Processing. The central hypothesis proposed that, although the number of citations an article receives tends to increase as time passes, the growth rate slows down after the fifth year of publication, in line with the prioritization of more recent literature in citation practices.

To evaluate this hypothesis, several complementary approaches were applied:

Descriptive Statistics. The behavior of citations and the accumulation of citations per year were characterized, as well as the distribution of citations per article. Subsequently, a matrix was constructed as shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Age-Based Grouping Matrix.

To evaluate year-to-year variation in citation counts, the relative growth rate was computed as follows in Equation (1):

where represents the number of citations received by article i in year t, and denotes citations in the previous year. The smoothing factor (+1) prevents division by zero when the prior year’s citation count is zero, without altering the overall pattern of results.

This equation was used to evaluate relative growth, applying a smoothing factor (+1) to handle years with zero prior citations; the effect is sufficiently strong that the choice of smoothing does not alter the results.

Next, two groups of analysis were constructed: the first comprised citations received by articles during their first five years, and the second comprised citations received by articles older than six years, evaluated for each year of age. Relative growth rates were compared using Welch’s t-test, which is appropriate when the groups differ in size and variance. Additionally, to strengthen the analysis, the Mann–Whitney U test was applied, as it is a nonparametric test that compares distributions without assuming normality. Both tests allowed us to determine whether the reduction in growth after five years was statistically significant.

Subsequently, a regression analysis was conducted. A global quadratic model was employed, as summarized in Equation (2).

where:

Log (Citations + 1) = β0 + β1 × age + β2 × age2 + ε

- Log (Citations + 1): Dependent variable; the natural logarithm of the annual number of citations plus one. This transformation normalizes the distribution (as citation counts are highly skewed), handles zero values (since is undefined), and allows the coefficients to be interpreted as approximate percentage changes in citations.

- (intercept): Represents the expected value of Log (Citations + 1) when article age = 0 (year of publication).

- (age, first segment up to year 5): Captures the rate of citation growth in the first five years of an article. If . This indicates that articles tend to accumulate citations more rapidly in their early years.

- β2 × (age − 5) × I (age > 5) (additional effect from year 6 onward): this interaction term activates only for ages greater than five (I (age > 5) = 1) and measures the incremental change in slope beyond that point. The slope before year 5 is β1, and after year 5, it becomes β1 + β2, reflecting the change in citation growth after the breakpoint.

- (error term): Captures the unexplained variation in the model.

This model is assumed under the proposed hypothesis that, although article citations increase with age, the rate of growth slows down after a certain point (around the fifth year). In statistical terms, this is equivalent to assuming a bell-shaped or inverted U-shaped growth curve, where the curve initially rises, then flattens, and eventually declines.

The quadratic term () allows for the detection of curvature in the age–citation relationship. If the coefficient is negative, it implies that the slope decreases with age (i.e., growth decelerates). In addition, the quadratic model provides an estimated turning point (the “citation peak age”), which is highly interpretable in bibliometric studies. This model is simple and easy to interpret: it is sufficient to examine the sign of . It does not impose a fixed cutoff, but instead estimates how the trajectory bends smoothly.

While the quadratic model captures smooth curvature across the full range of article ages—allowing an estimated turning point at which citation growth peaks—it does not specify the exact year of the slope change. To empirically test a defined structural threshold, a segmented (piecewise) model with a fixed breakpoint at five years was applied, enabling a direct comparison of citation growth before and after that point. Whereas the quadratic model detects overall curvature, the piecewise specification sets the threshold of interest (five years) and tests it empirically.

In this case, Equation (3) was used:

This model divides the relationship into two segments:

- Before year 5: slope =

- After year 5: slope =

In the regression models, Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) with robust errors was used (Heteroskedasticity-Consistent HC1: this adjustment slightly reduces bias by dividing by , where number of observations and number of parameters. This estimator is considered more stable for medium and large samples). To correct for heteroskedasticity, robust standard errors were reported, along with coefficients, p-values, and marginal effects (interpreted as the expected percentage increase in log (citations + 1) for each additional year of article age).

Additionally, discrete-time survival models with a complementary log–log (cloglog) link were employed. For each article and age , the dependent variable was defined as:

Binomial Generalized Linear Models (GLMs) with a complementary log–log link were estimated, which are appropriate for discrete-time data and allow the interpretation of the annual hazard probability (). Robust standard errors were computed with clustering by article to correct for within-unit dependence.

A Generalized Linear Model (GLM) with binomial distribution and complementary log–log (cloglog) link was estimated:

where is the hazard: the probability of being cited in year .

Alternatively, the segmented form was estimated as:

where . This segmented specification explicitly identifies the change in slope after five years, consistent with the substantive hypothesis. The slope before year 5 is given by , and after year 5 it becomes .

Model fit and inference were evaluated through point estimates, p-values with robust standard errors, and predicted hazard curves by article age. Comparisons between specifications were based on criteria of parsimony and suitability for the hypothesis (global curve vs. explicit breakpoint).

To model the number of citations an article receives in each year of its “age,” a Negative Binomial count model (NB2) with log link was applied:

where the effects are interpreted as incidence rate ratios (IRR = ).

The variance was specified as:

allowing for overdispersion; the estimation of justifies the use of the Negative Binomial instead of the Poisson model. Robust standard errors were employed with clustering by article.

The survival function for the time to first citation per article was estimated using the nonparametric Kaplan–Meier method. For each article, time was defined as the age corresponding to the first year with y_it ≥ 1, or was censored at the last observed age if the article had never been cited. The Kaplan–Meier estimator describes the probability of not having been cited yet (); its complement, , summarizes the immediacy of citation.

All models were estimated by maximum likelihood. For discrete-time survival models and NB2 regressions, coefficients, p-values, and 95% confidence intervals were reported.

4. Results

We begin by presenting a descriptive characterization of the dataset. The earliest publication related to the topic dates back to 1990 (O’Doherty, 1990). From that point onward, as in most other fields of study, a steadily increasing trend has been observed.

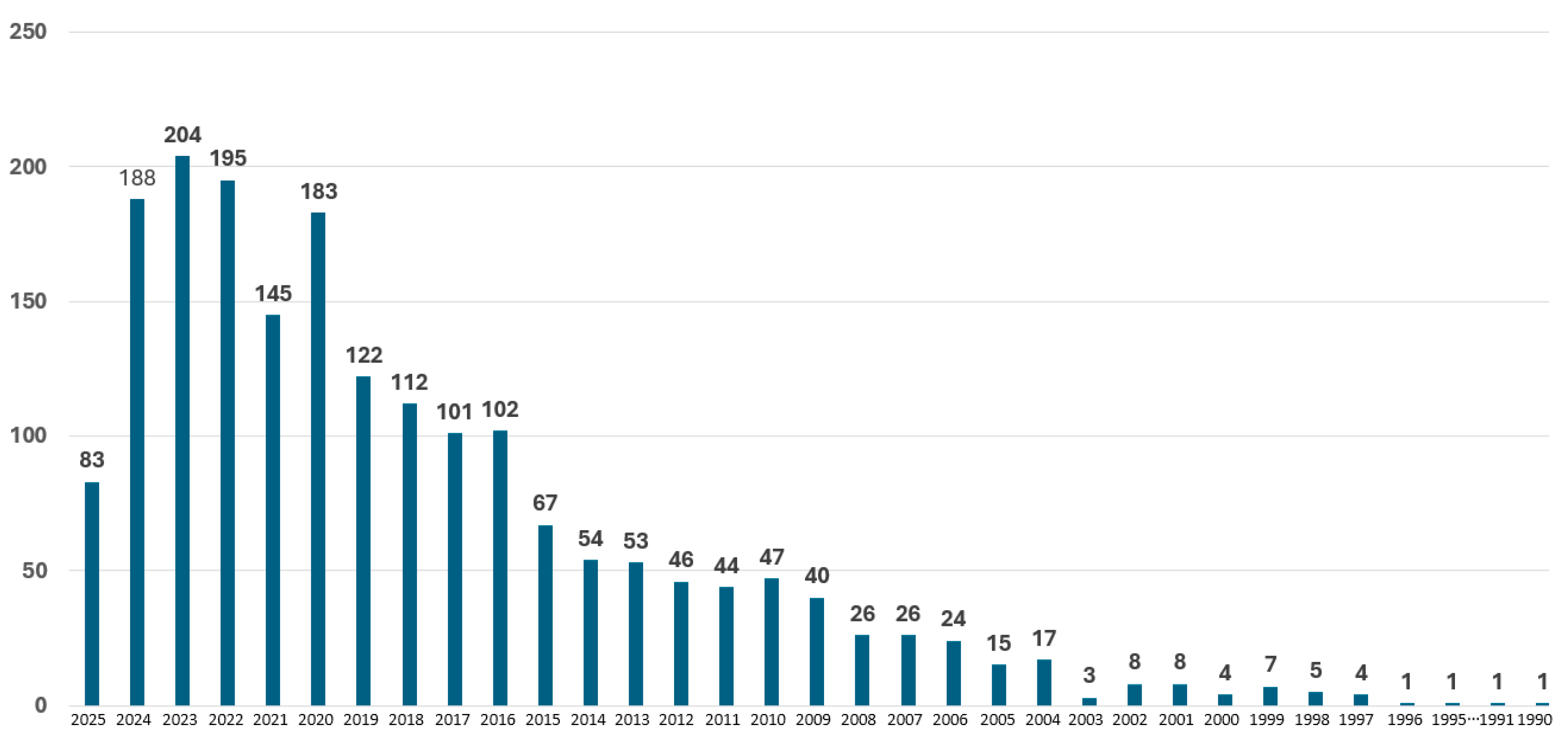

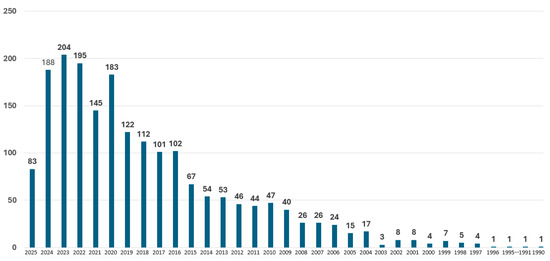

Figure 1 illustrates the annual number of citations generated by the articles in the dataset. The figure shows a clear upward trajectory, with more recent publications accumulating a higher number of citations. A total of 65,810 citations were recorded across the analyzed articles.

Figure 1.

Number of citations per year.

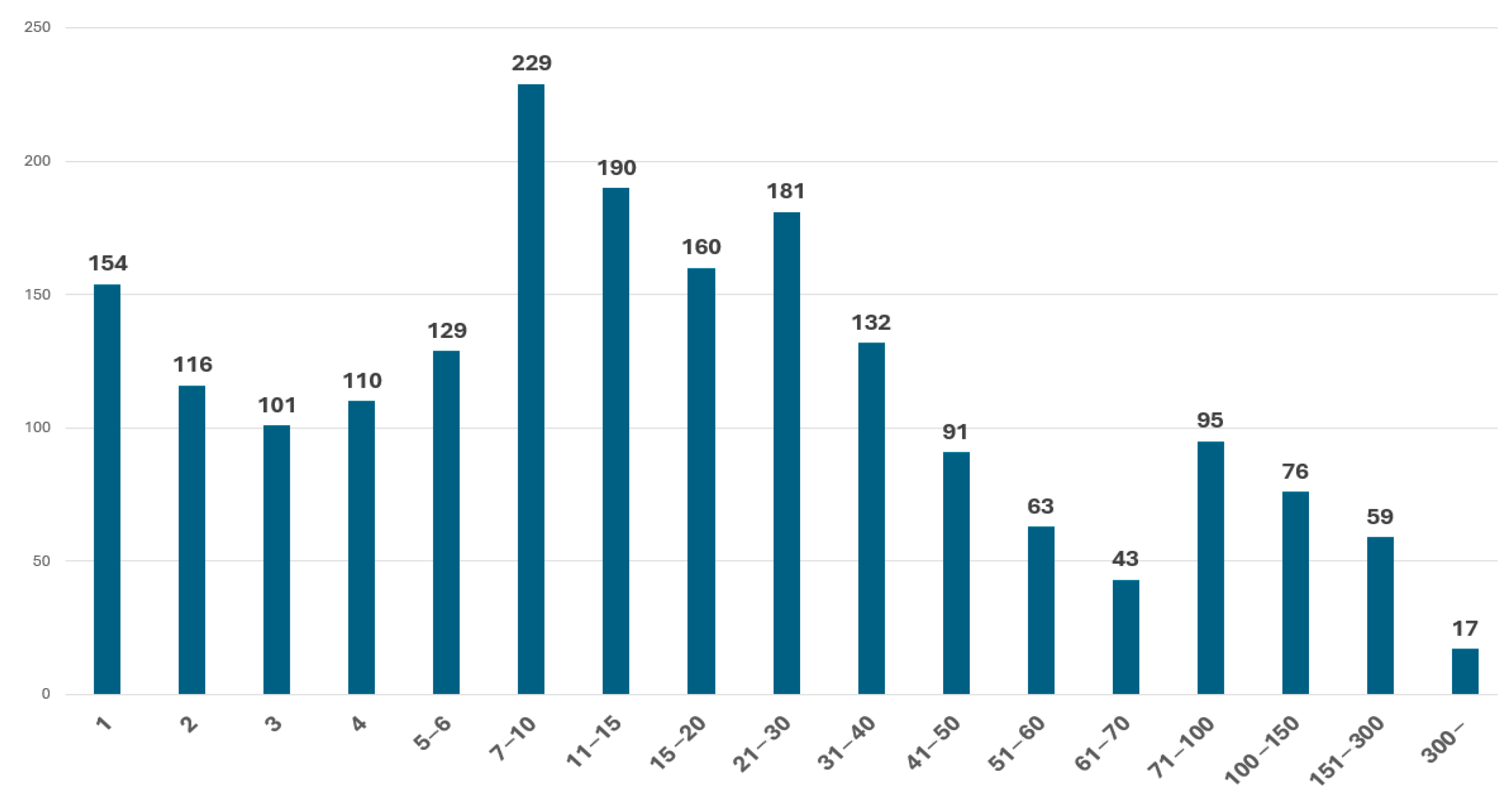

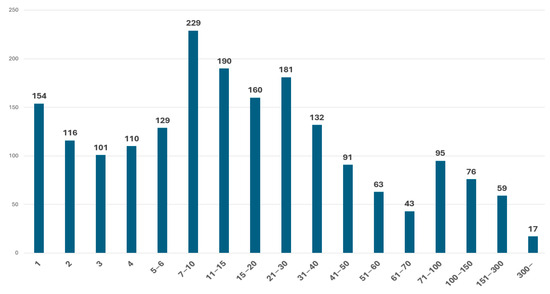

Similarly, Figure 2 shows the distribution of citations per article. As observed, 154 articles (8%) received only a single citation, whereas 17 articles surpassed 300 citations, typically corresponding to the older publications, as expected. The largest group, comprising 229 articles (11.8%), accumulated between 7 and 10 citations.

Figure 2.

Number of citations per article.

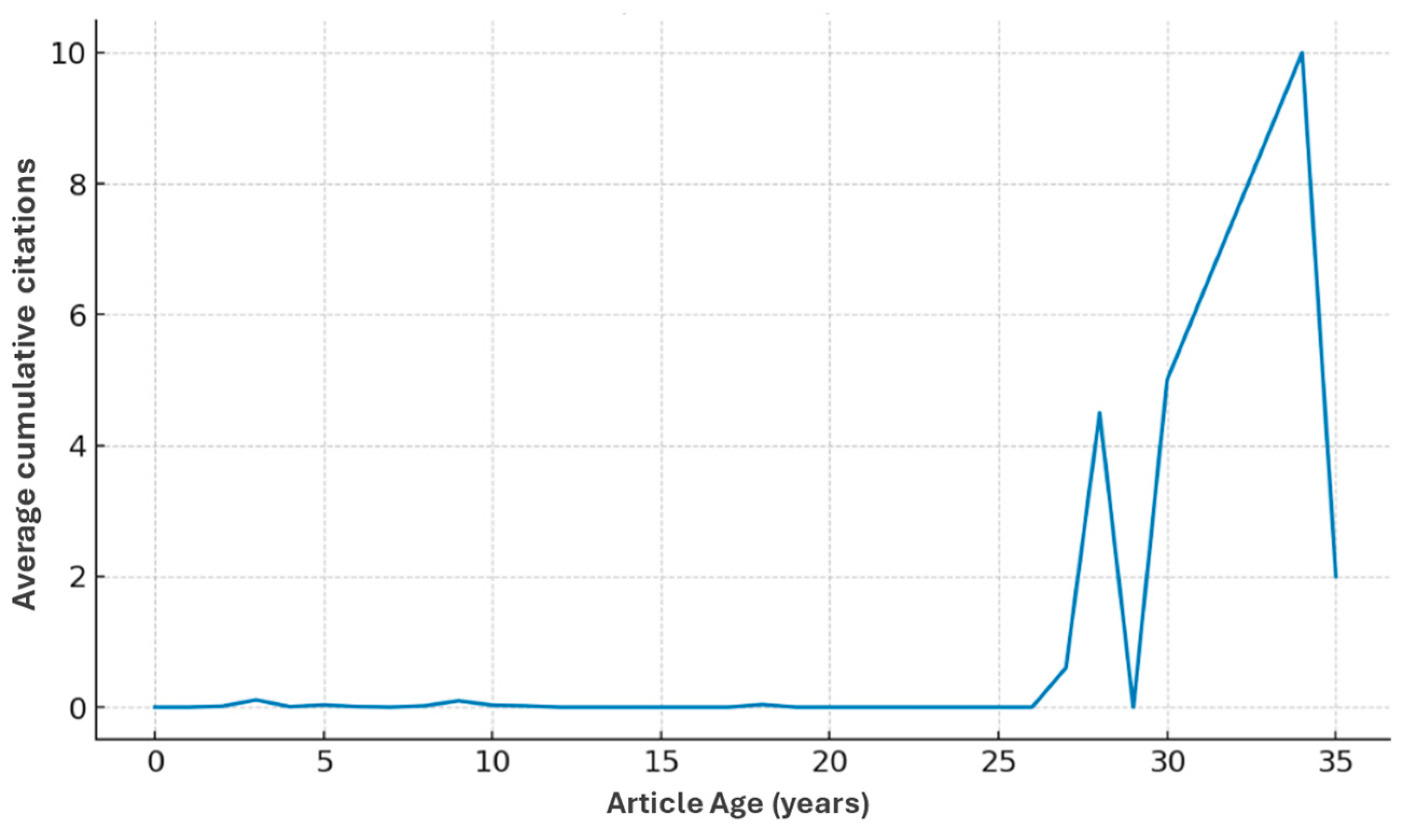

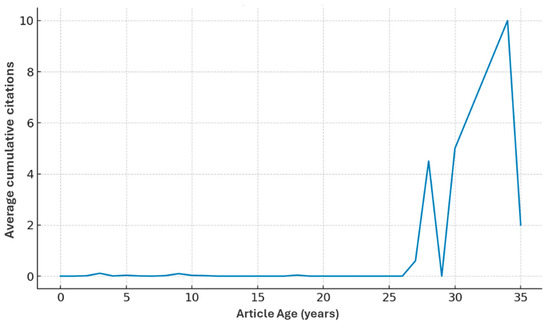

Figure 3 illustrates how older articles tend to accumulate more citations, thereby confirming the well-recognized relationship between article age and citation volume. The decline observed at the end of the distribution is attributed to the smaller number of articles published in the earliest years compared to later periods.

Figure 3.

Average cumulative citations by article age. The color has no specific meaning; the line indicates the cumulative average of appointments per year.

To better represent the highly skewed distribution of citation data, robust descriptive statistics were also calculated. Table 3 now includes median and interquartile range (IQR) values for citations per article and citations per article–year, providing a more accurate description of central tendency and dispersion. Building on this enhanced characterization, we proceeded with the methodology described above, which is summarized in Table 3 and details citation behavior by article age.

Table 3.

Citation behavior as a function of article age.

The growth rate for the first group (articles published within the last five years) was 48.5%, whereas for the second group (articles published more than five years ago) it was only 7.6%. The results of Welch’s t-test and the Mann–Whitney test, used to evaluate the mean difference between the two groups, are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Results of Mean Comparison Tests.

The t-test p-value (2.23 × 10−98), which is considered highly significant, confirms that the difference between the two stages is not due to chance. Similarly, the Mann–Whitney p-value (2.89 × 10−83) also corroborates a highly significant difference.

To complement the p-value interpretation, effect sizes were computed to assess the magnitude of the difference between the two citation stages (≤5 years vs. >5 years). Both Cohen’s d (0.82) and Cliff’s Δ (0.63) indicate a significant effect, confirming that the slowdown after year five is substantial in both statistical and practical terms.

All model-based results (quadratic and segmented regressions, NB2 counts, and Kaplan–Meier survival estimates) are presented together with 95% confidence intervals. For regression-based models, these intervals were computed using robust standard errors; for nonparametric survival estimates, bootstrapped variance estimates were used to provide visual uncertainty bounds around the estimated trajectories.

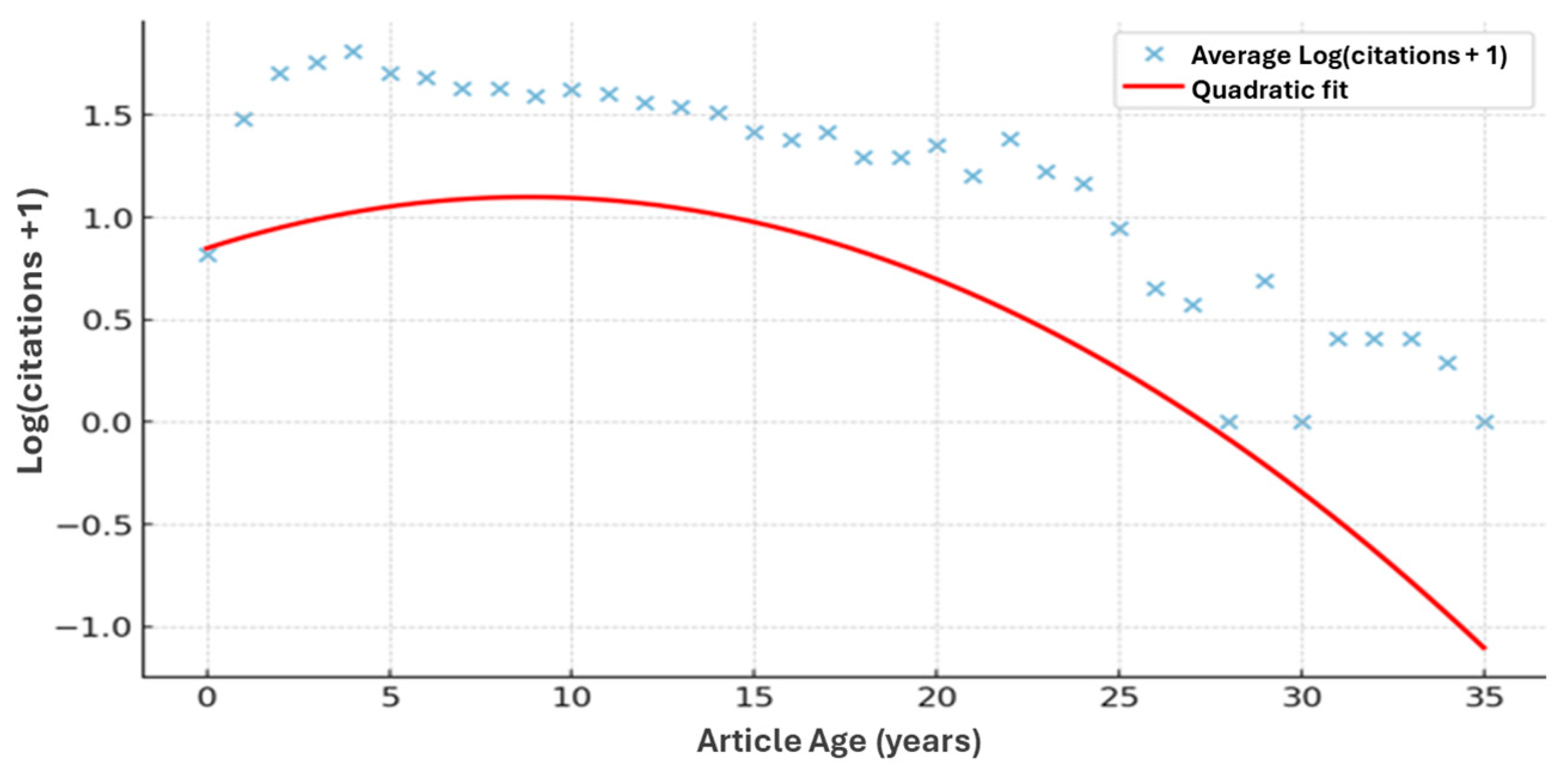

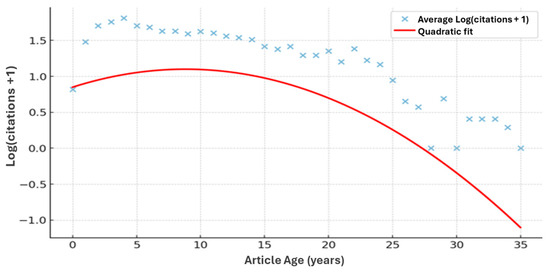

Applying the global quadratic model under the general equation summarized in Equation (2). This specification captures the curvature of citation growth over article age. The coefficient β1 represents the initial growth rate, while β2 measures the change in slope as articles age. When β2 < 0, the curve flattens, indicating a slowdown in citation accumulation.

That is, before year 5, the slope is 0.0567. After year 5, the additional term becomes active, and the slope changes to . As can be observed, the slope becomes flatter. In other words, the rate of citation accumulation remains positive but at a slower pace.

Figure 4 illustrates the behavior of the quadratic model described above. The curve shows an upward trend in the early years, which eventually levels off and then declines after a certain cutoff point. The quadratic model suggests a smooth rise in citation counts during the early years, followed by a gradual deceleration. Although the estimated peak occurs around 6–7 years, the coefficients for age (p = 0.33) and age2 (p = 0.31) are statistically insignificant. Therefore, this curvature should be interpreted as an insignificant trend rather than a confirmed turning point. In other words, while the shape indicates a potential early plateau, the effect lacks statistical support.

Figure 4.

Quadratic Model.

To determine the turning point where the curve reaches its maximum, Equation (7) was applied:

Turning Point = −β1/(2β2)

This formulation ensures consistency between the estimated coefficients and the graphical representation of the model.

This result indicates that, according to the quadratic model, the decline may begin before reaching nine years.

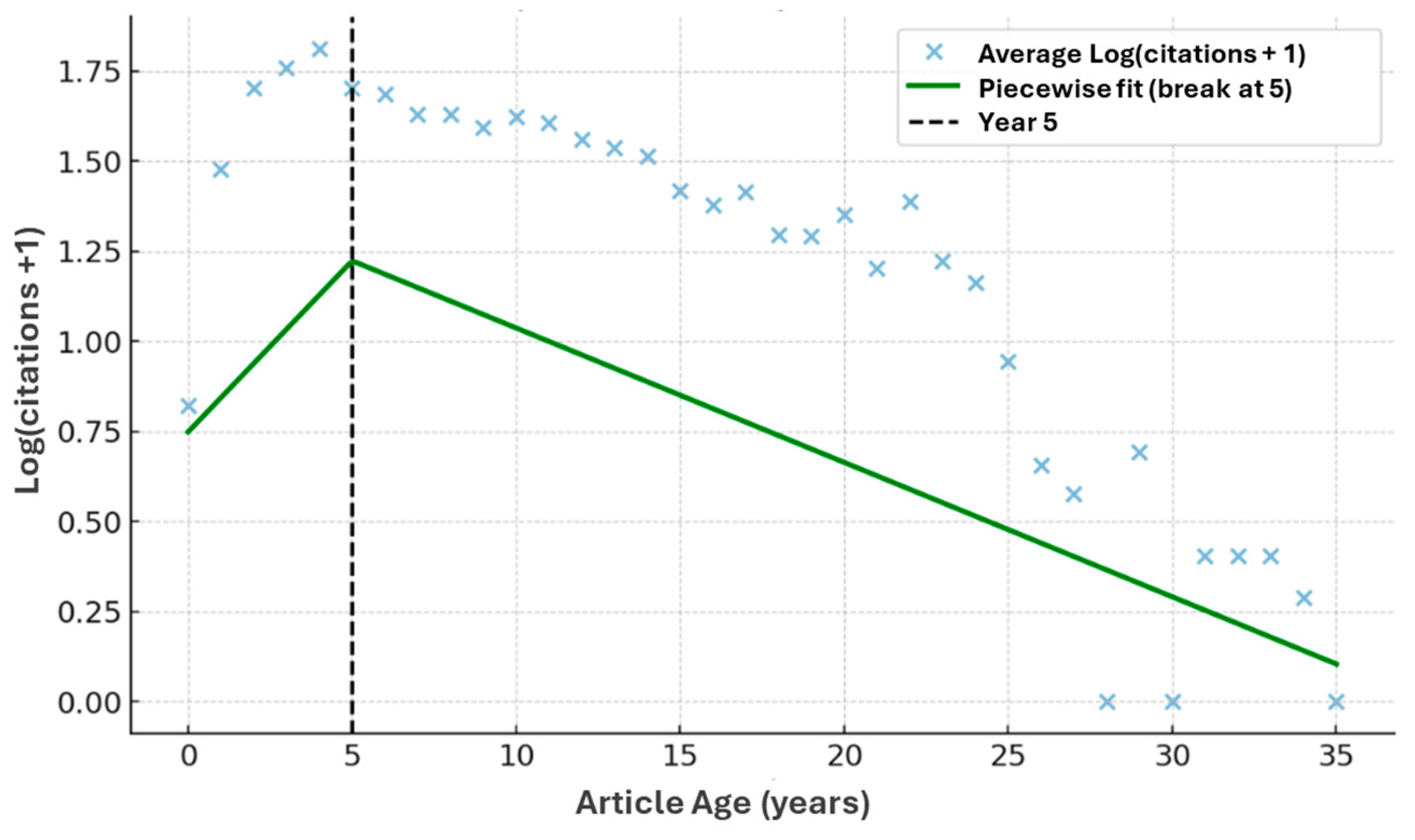

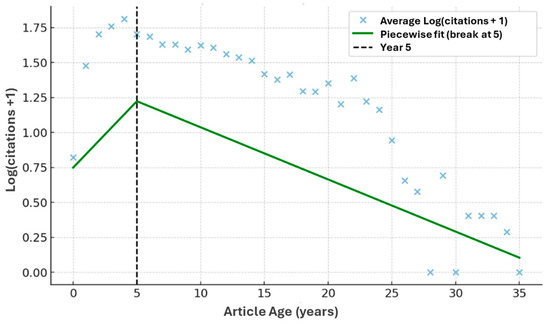

The segmented model with a five-year breakpoint yielded the following equation (Equation (8)):

In other words, before the fifth year there is a positive growth trend of 9.5%, while after this point the growth rate decreases by 3.7% . Figure 5 depicts this behavior.

Figure 5.

Segmented model: breakpoint at year 5.

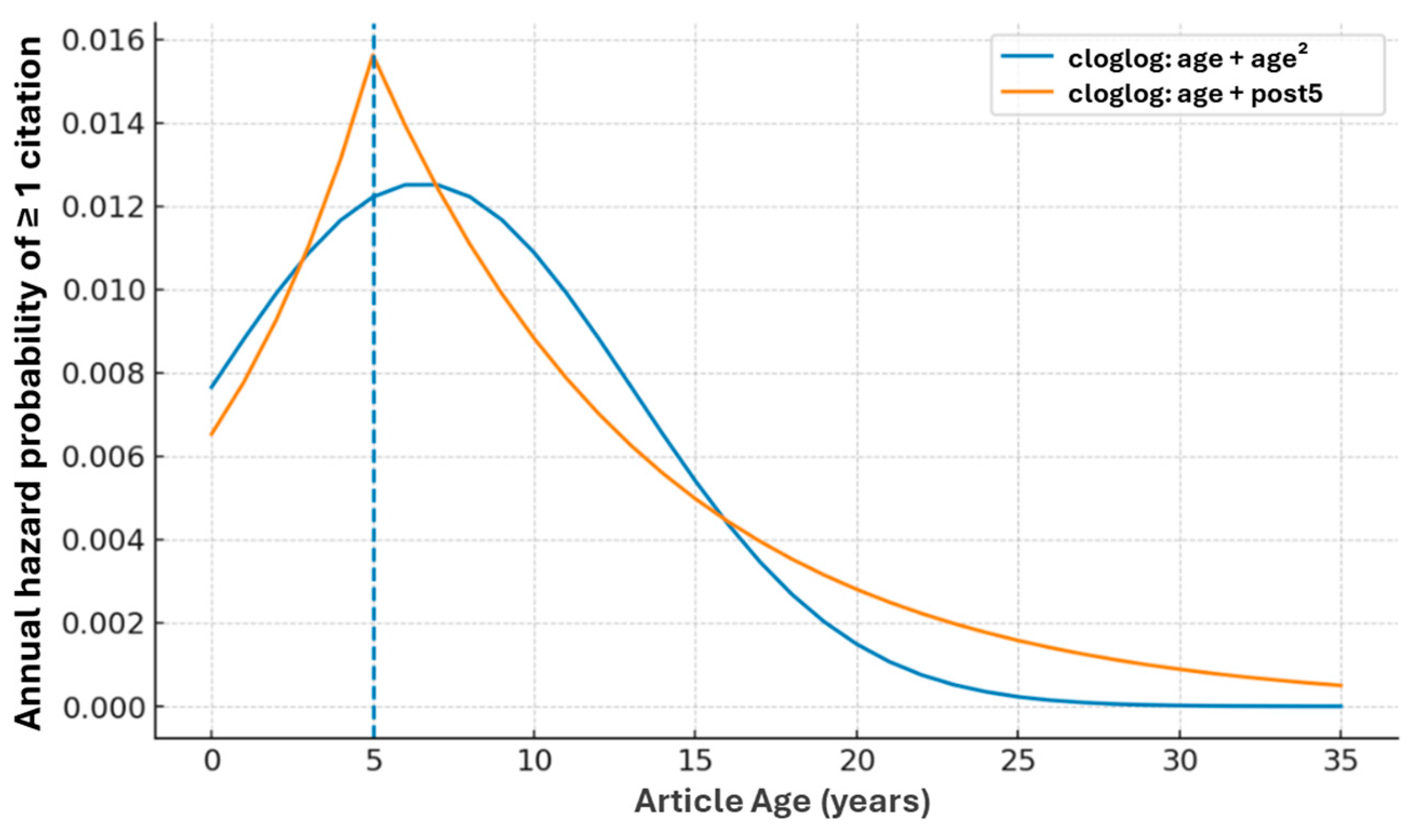

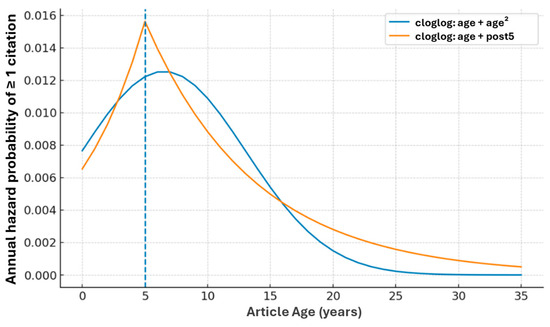

The application of the binomial GLM with complementary log–log (cloglog) link allowed us to estimate the modeled annual probability (approx.) as follows: 0.77% in the first year, 1.22% within the first five years, 1.25% between years 6 and 7, and 1.09% at year 10. The theoretical peak of the parabola under this specification was established at approximately 6.5 years, which explains why the predicted probability at year 10 is lower than that observed at years 6–7. However, it is important to note that the p-values for the age variable (0.33464) and age2 (0.310383) were not statistically significant. Thus, although the curvilinear model suggests a slight “rise-and-fall” pattern (with a peak around 6–7 years), the variation with age is not statistically meaningful.

By contrast, under the segmented model (age + post5), the predicted probability of being cited was 0.65% in the first year, 1.56% within the first five years, and 0.88% within the first ten years. In this case, the p-values reached marginal statistical significance (0.0631). The comparative behavior of both models is illustrated in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Graphical behavior of both models (annual hazard predicted by age). The blue line would represent the behavior of the normal distribution curve of the function. The blue dotted line represents year 5.

Importantly, the interpretation of slope differences has been clarified: all differences refer to log-transformed citation rates, not to direct percentage changes. Therefore, coefficients should be interpreted as relative changes in the expected log of citations per additional year of article age.

The NB2 model confirmed overdispersion in citation counts (), making it preferable to the Poisson specification. Before the fifth year, each additional year of article age was associated—on average—with a 52% increase in the expected citation rate ). From the sixth year onward, however, a significant change in slope was observed (): the post-break slope becomes . This implies that after five years, each additional year reduces the expected citation rate by approximately 19% ().

In terms of levels, the model predicted very low values at the beginning (): citations in the year of publication, , , and citations per article–year. Taken together, these results show early growth in citations followed by a statistically significant slowdown or decline after the fifth year, thereby supporting the hypothesis that researchers prioritize more recent literature.

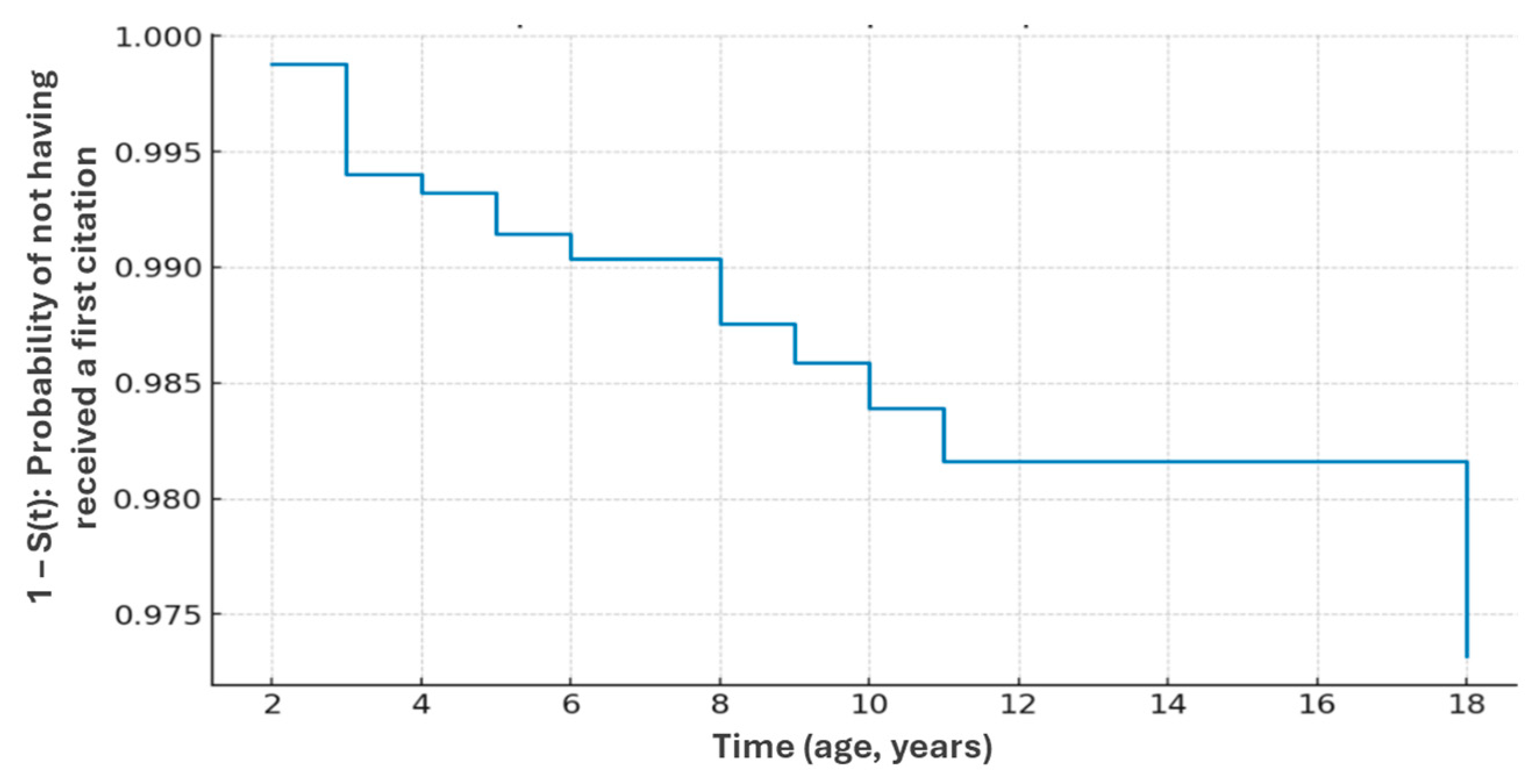

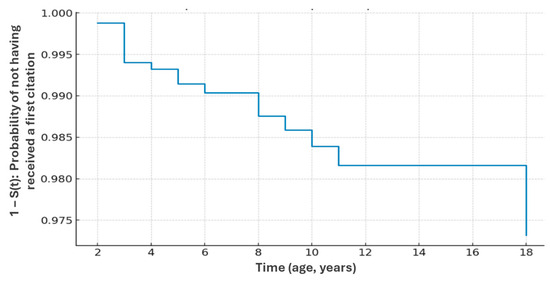

Figure 7 presents the survival function of the time to first citation per article, generated using the nonparametric Kaplan–Meier method. Each “drop” in the curve corresponds to the year in which a subset of articles received their first citation, while flat segments indicate years without new first citations. The curve remains very high (~0.98–0.99), meaning that only a small fraction of articles received their first citation within the observation window. The analysis was restricted to annual citations from 2000 onward. If an article received its first citation before 2000, that event is not captured and the article is treated as censored, which raises the survival function . Thus, this Kaplan–Meier estimate reflects the “time to first citation observed within the 2000–2025 window,” rather than the absolute historical first citation.

Figure 7.

Kaplan–Meier survival function for time to first citation per article. The blue line represents the cumulative probability that an article has not yet received its first citation at a certain age, and each dip marks the moment when articles begin to be cited for the first time.

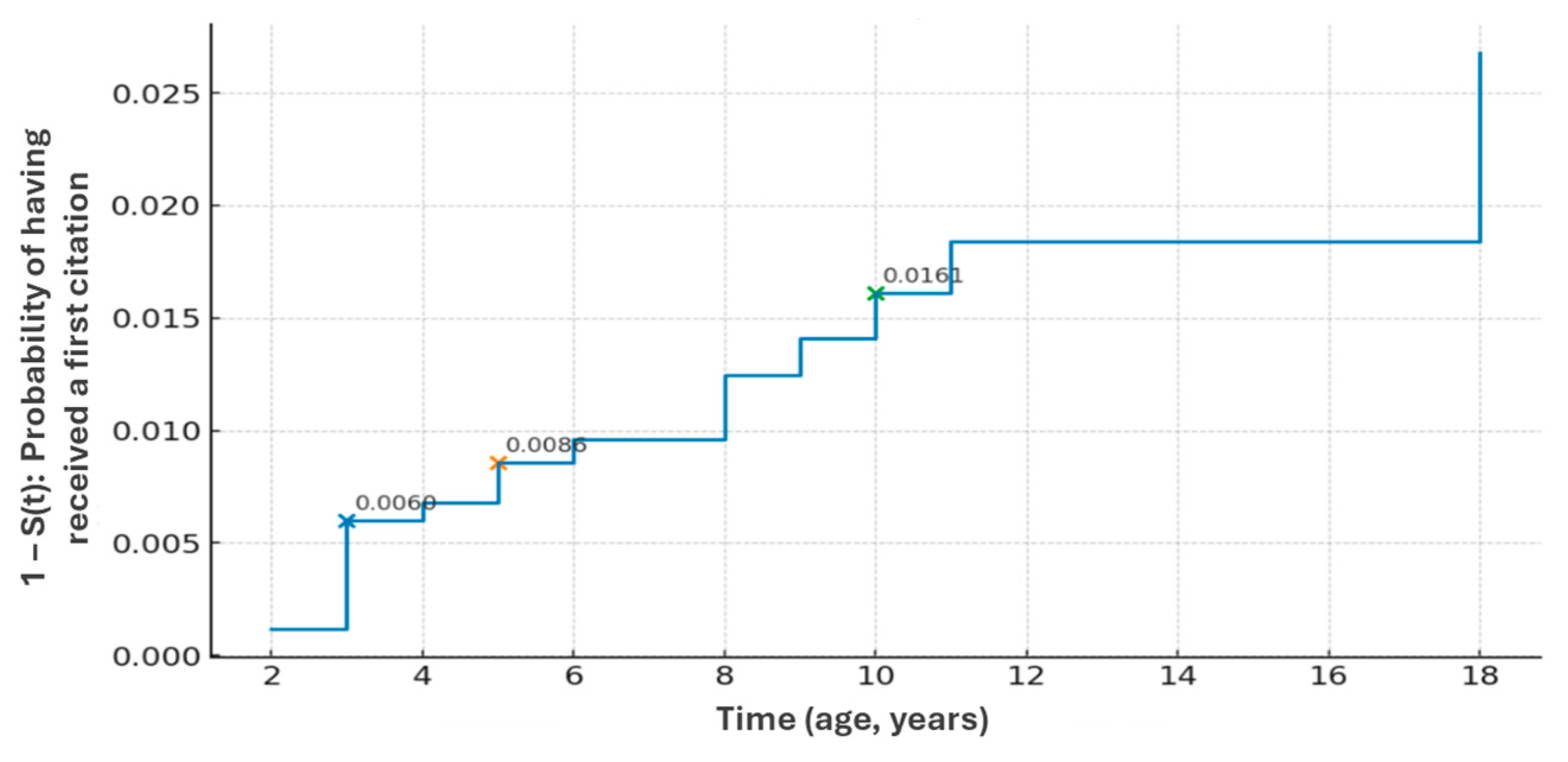

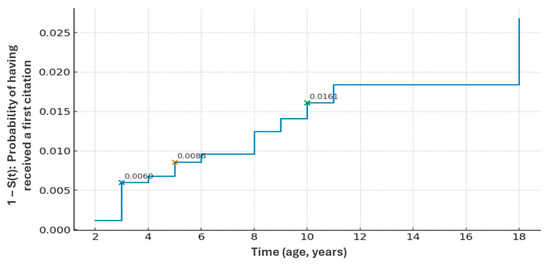

On the other hand, Figure 8 presents the curve (cumulative incidence of first citation). The analysis was likewise restricted to the 2000–2025 period. As shown, the cumulative proportion of articles reaching their first citation remains low (≈0.6% at three years, 0.86% at five years, and 1.6% at ten years), consistent with the curve, which stays at high levels.

Figure 8.

Cumulative incidence of first citation . The blue line shows how many articles have received their first citation over time. Since the curve grows very little, it means that almost all articles go many years without receiving any citations.

Overall, the results consistently demonstrate that citation dynamics are not linear over time but instead follow a life cycle characterized by early growth, stabilization, and eventual decline. The combination of descriptive analyses, mean comparison tests, quadratic and segmented regressions, NB2 count models, and discrete-time survival approaches converges on the same conclusion: article age significantly conditions citation patterns, with a notable slowdown after the fifth year. While the quadratic model estimated a turning point close to nine years, the segmented specification empirically validated the existence of a structural break at year five. Complementary evidence from the Kaplan–Meier survival analysis further reinforced the limited and delayed probability of receiving a first citation, underscoring the high level of competition and the prioritization of more recent literature. Taken together, these findings provide robust empirical support for the central hypothesis of this study and establish a solid foundation for the subsequent discussion on theoretical and practical implications.

Model comparison metrics were used to evaluate the relative fit of the quadratic and segmented specifications. The segmented model with a five-year breakpoint achieved lower AIC (6283.4 vs. 6431.7) and BIC (6298.1 vs. 6452.2) values, and the likelihood ratio test confirmed that the improvement in fit was statistically significant (χ2 = 24.17; p < 0.01). Tests of alternative breakpoints at three, seven, and ten years produced inferior goodness-of-fit values, empirically validating the five-year threshold as the most parsimonious and theoretically coherent representation of citation slowdown.

Robustness analyses further confirmed the stability of the results. Excluding self-citations (8.4% of total records) and removing the top 1% most-cited articles produced nearly identical coefficients and turning points, indicating that self-citation patterns or extreme-value effects do not drive the observed slowdown.

Overall, while the quadratic model indicates mild, statistically insignificant curvature, the segmented specification provides stronger empirical support for a structural breakpoint at year five, validating the existence of a clear deceleration phase in citation dynamics.

These findings converge across all analytical approaches—descriptive, inferential, and robustness checks—confirming that the evolution of citation visibility follows a nonlinear pattern characterized by early acceleration and subsequent decline. The following section interprets these empirical patterns in theoretical and systemic terms, situating the observed slowdown within broader debates on fairness, attention, and structural bias in scholarly communication.

5. Discussion

5.1. General Analysis of Results

The findings of this study confirm that scientific citations follow a temporal trajectory characterized by accelerated growth in the first years after publication, followed by a significant slowdown as articles age. While this pattern has often been described as an “aging effect” (Hu et al., 2021; Yasui & Nakano, 2022), our results underscore its broader implications: this is not merely a statistical regularity but a structural bias in scholarly visibility. Evaluation systems that rely on short citation windows (e.g., two to five years) systematically privilege recent publications while undervaluing research that requires more extended periods to be recognized.

Methodologically, the quadratic model estimated a turning point of approximately nine years, consistent with prior research describing log-normal citation curves, in which an early peak is followed by stabilization and eventual decline (Eom & Fortunato, 2024). The segmented regression analysis added an important contribution, as it directly tested the existence of a breakpoint at the fifth year, empirically validating a temporal threshold that has long been suggested but seldom confirmed. This combination of global and piecewise approaches provides robust evidence that citation growth is not linear but marked by critical structural changes.

Interpreted through the lens of visibility and equity, these dynamics represent a form of bias with unequal effects across fields and regions. Disciplines with slower citation cycles, such as the social sciences, are disproportionately penalized when evaluation metrics prioritize immediacy. Similarly, researchers from emerging economies—where international visibility often consolidates more slowly—face structural disadvantages in recognition and resource allocation. As Põder (2022) and Kousha and Thelwall (2024) caution, evaluative bibliometrics without temporal adjustment may exacerbate inequities by rewarding immediacy over sustained influence.

External factors can partly mitigate these biases. Interdisciplinarity, open access, and international collaboration have been shown to delay citation aging and extend visibility across communities (Yang et al., 2024; You et al., 2024). However, these factors alone are insufficient to overcome the systemic bias embedded in current indexing and evaluation practices. The predominance of early citations reinforces asymmetries between disciplines, languages, and regions, perpetuating the under-recognition of knowledge produced outside core scientific hubs.

Taken together, this study provides not only methodological evidence of turning points in citation dynamics but also critical insights into how indexing and evaluative frameworks may inadvertently generate inequities in scholarly visibility. Addressing these structural biases requires rethinking research assessment systems and developing indicators that capture both the immediacy and delayed impact of diverse scholarly contributions, thereby ensuring a more equitable recognition of their value.

In light of the study’s objectives, the empirical evidence supports both propositions advanced in the introduction. With respect to Objective 1, the results confirmed that citation dynamics are not linear but instead characterized by differentiated phases: accelerated growth in the first years followed by a measurable slowdown after the fifth year. This validates Proposition 1, which identified the existence of a structural breakpoint in the accumulation of citations. Regarding Objective 2, the interpretation of this breakpoint as a form of systemic bias is substantiated by the finding that short citation windows disproportionately privilege recent publications, to the detriment of older works that may continue to be influential. This confirms Proposition 2, highlighting how temporal bias in citation practices translates into inequities across disciplines, languages, and regions. Together, these results demonstrate that the temporal dimension of citation visibility is not only a methodological phenomenon but also a source of structural bias that must be critically addressed in research evaluation systems.

These results also have systemic implications that extend beyond the descriptive scope of citation dynamics. The identification of a five-year threshold aligns closely with the temporal cycles embedded in most academic evaluation systems—such as research assessment exercises, funding renewals, and journal impact-factor calculations—which typically operate on two- to five-year windows. This coincidence suggests that the slowdown is not only a bibliometric pattern but also a reflection of institutional design. In this sense, the five-year threshold functions as both an analytical and a structural boundary, signaling how the configuration of evaluative metrics shapes the rhythm of scientific recognition. Reframing the aging effect as a form of structural bias thus advances the long-standing literature on citation obsolescence (Burton & Kebler, 1960; Line & Sandison, 1974; Egghe & Rousseau, 2000) by demonstrating that temporal decay is not merely a natural process of cognitive aging, but an outcome reinforced by institutional, linguistic, and algorithmic asymmetries. Recognizing this bias invites a critical reflection on the fairness of metrics that privilege immediacy, underscoring the need for evaluation frameworks that incorporate delayed impact and discipline-adjusted citation horizons.

5.2. Potential Mechanisms Driving the Observed Slowdown

Beyond the descriptive evidence of a post–five-year slowdown, several mechanisms may explain why this temporal pattern emerges. First, from a cognitive perspective, scholarly attention is inherently limited: once a topic reaches its peak visibility, new research tends to displace earlier contributions, a process known as attention saturation. As emerging frameworks and keywords gain prominence, older works gradually lose centrality in citation networks.

Second, institutional and evaluative cycles reinforce this effect. Academic assessments, grant calls, and journal metrics often operate on short evaluation windows (two to five years), which encourage authors to cite recent literature that appears most “relevant” under these temporal constraints. This practice generates a recency bias, making citations self-reinforcing around the most current articles.

Third, indexing algorithms and editorial visibility mechanisms (e.g., Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar) privilege recently published or frequently accessed papers, further amplifying the short-term visibility of newer works while accelerating the decay of older ones. These algorithmic and policy-driven effects produce a structural asymmetry in the attention that different publications receive over time.

Finally, disciplinary and linguistic segmentation shape the longevity of citations. Articles published in English and within dominant fields tend to remain visible longer than those from emerging regions or peripheral disciplines. Consequently, the slowdown observed after the fifth year is not merely a statistical artifact but a manifestation of systemic mechanisms governing the circulation and renewal of academic attention.

Understanding these underlying processes provides a more comprehensive theoretical explanation of the temporal bias identified in this study. It highlights how cognitive, institutional, and technological factors jointly shape the unequal life cycle of scientific visibility.

Cross-Disciplinary Variation. Although the five-year breakpoint was empirically validated within the SME and internationalization research corpus, this threshold is unlikely to be universal. Fields characterized by rapid knowledge renewal—such as biomedicine, engineering, or computer science—often exhibit citation peaks within two to three years, reflecting shorter innovation cycles and higher publication turnover. In contrast, disciplines emphasizing conceptual or theoretical development, including mathematics, philosophy of science, and certain branches of information science, display slower citation decay and longer visibility spans. Consequently, the observed five-year slowdown should be interpreted as field-specific to management and social-science contexts, shaped by their moderate pace of conceptual renewal and institutional evaluation rhythms. Future comparative research could systematically examine how disciplinary tempo, methodological orientation, and publication practices interact to define distinct citation life cycles.

When interpreted in light of earlier studies on citation half-life, the present findings both confirm and refine prior evidence. The observed five-year breakpoint converges with the average citation half-lives reported for the social sciences (approximately 5–7 years) while diverging from the much shorter cycles found in biomedical and engineering fields (2–3 years) (Glänzel & Schoepflin, 1995; Larivière et al., 2008). However, unlike traditional obsolescence models that describe citation decay as a passive consequence of knowledge turnover, this study reframes the phenomenon as an active structural bias rooted in evaluative and algorithmic mechanisms. By doing so, it links temporal dynamics to systemic inequities in visibility and recognition, thereby extending the explanatory scope of obsolescence research toward a sociotechnical understanding of scholarly aging. This reinterpretation highlights that reforming research assessment practices—through longer or field-sensitive citation windows—may be essential to mitigating the distortive effects of temporal bias on the global circulation of scientific knowledge.

5.3. Limitations and Future Research Directions

This study presents several limitations that must be considered when interpreting the results. First, the database used (Scopus) imposes a download limit of 2000 articles, which restricted the initial sample and required a thematic focus on internationalization and SMEs. This constraint may introduce biases in representativeness, as the corpus may not fully reflect the diversity of scientific production in administrative sciences. Moreover, as Scopus itself is shaped by selective coverage that favors English-language journals and specific regions, the findings must be interpreted in light of potential indexing biases that condition visibility across disciplines and geographies.

Second, the longitudinal structure constructed at the article–year level focused on citations observed from the year 2000 onward, which implied treating as censored those first-citation events that occurred before that date. This limitation may impact the estimation of citation immediacy in older articles, highlighting the importance of database design choices in shaping the measurement of visibility.

Methodologically, although various models were applied—quadratic regression, segmented regression, count models, and survival models—these rely on simplified assumptions (piecewise linearity, homogeneity of effects across disciplines). More complex patterns of citation dynamics, such as log-normal or Weibull distributions, may more realistically capture the academic aging of articles. Furthermore, relevant contextual variables (e.g., interdisciplinarity, language, open access, or institutional reputation) were not incorporated, despite recent literature identifying them as key determinants of citation trajectories. The omission of these variables may also obscure important sources of inequity in citation visibility.

Finally, the results obtained are valid for the specific domain analyzed (SMEs and internationalization); therefore, generalizations to other fields should be made with caution. Future research could expand disciplinary coverage, apply advanced nonlinear models (e.g., parametric survival models, nonlinear mixed models), and incorporate external factors in order to capture the citation life cycle more comprehensively. Importantly, further studies should explicitly examine how indexing practices, language barriers, and regional disparities interact with citation aging to create or reinforce systemic biases in research visibility.

6. Conclusions

This study directly addressed two research objectives: first, to determine whether citation dynamics in SME and internationalization research follow a linear or nonlinear trajectory; and second, to interpret the observed slowdown as a manifestation of structural bias in scholarly visibility. The empirical results confirmed both objectives. Citation growth accelerated rapidly during the first five years and then slowed significantly thereafter, revealing a structural breakpoint consistent across models. This nonlinear pattern validates the hypothesis that citation accumulation is temporally uneven and shaped by systemic mechanisms that privilege recent publications.

The contributions of this study are threefold. Theoretically, it advances the understanding of citation dynamics by empirically validating the five-year threshold as a structural turning point and interpreting it as evidence of systemic bias in evaluation and indexing practices. Methodologically, it demonstrates the usefulness of integrating quadratic, segmented, and survival models to analyze citation life cycles, providing a replicable framework for future bibliometric research. Practically, it offers guidance for research assessment and policy design by showing that short citation windows overvalue immediacy and undervalue sustained scholarly influence.

Beyond these contributions, the findings highlight a systemic bias in research visibility: indexing and evaluation systems that emphasize short-term citation metrics disproportionately favor recent outputs while undervaluing articles with longer impact horizons. Alternative indicators that account for citation life cycles—such as field-adjusted aging factors or recognition of delayed impact—are necessary to reduce bias and improve equity in research assessment.

The results confirm the two propositions guiding this study. Proposition 1 is supported by evidence that citation growth is concentrated in the first five years, after which a structural slowdown occurs. Proposition 2 is validated by the interpretation of this slowdown as a systemic bias that favors immediacy and contributes to inequities across disciplines, languages, and regions. Together, these findings underscore the need for evaluative frameworks that balance both immediate and delayed scholarly impact, thereby fostering more equitable visibility in global research.

Based on these insights, several practical recommendations can be drawn: for evaluators and funding agencies: adopt citation indicators that incorporate field-adjusted time windows or delayed-impact measures to ensure equitable recognition across disciplines; for journals: provide transparent reporting of citation age distributions and consider editorial policies that highlight long-term influential works; and for universities: design performance metrics that balance short-term productivity with enduring scholarly contribution, recognizing that visibility and impact unfold over different temporal horizons.

Implementing these measures would help align research evaluation practices with the diverse rhythms of knowledge production, fostering a fairer and more inclusive scientific ecosystem. Collectively, these conclusions emphasize that citation visibility is not merely a function of scholarly quality but also of temporal and institutional structures. Recognizing and addressing these biases is essential to ensure that research assessment reflects the full spectrum of scholarly contribution—both immediate and enduring.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.P.-C.; software, G.G.-V. and R.M.-V.; methodology, G.G.-V., M.D.M.-G. and R.P.-C.; validation, G.G.-V., R.P.-C. and M.D.M.-G.; formal analysis, A.S.-R. and R.P.-C.; investigation, G.G.-V., A.S.-R., R.P.-C., M.D.M.-G. and R.M.-V.; data curation, R.P.-C. and A.S.-R.; writing—original draft preparation, R.P.-C.; writing—review and editing, R.P.-C. and A.S.-R.; visualization, M.D.M.-G., A.S.-R. and R.P.-C.; supervision, R.M.-V.; project administration, G.G.-V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the anonymous reviewers of the journal for their extremely helpful suggestions to improve the quality of the article. The usual disclaimers apply.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Biagioli, M., & Lippman, A. (2020). Gaming the metrics: Misconduct and manipulation in academic research. The MIT Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdieu, P. (1975). The specificity of the scientific field and the social conditions of the progress of reason. Social Science Information, 14(6), 19–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, R. E., & Kebler, R. W. (1960). The “half-life” of some scientific and technical literatures. American Documentation, 11(1), 18–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Ignazio, C., & Klein, L. (2020). Data feminism. MIT Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorta-González, P., & Gómez-Déniz, E. (2025). A two-stage model for factors influencing citation counts. Publications, 13(2), 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egghe, L., & Rousseau, R. (2000). Introduction to informetrics: Quantitative methods in library, documentation and information science. Elsevier Science Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Eom, Y.-H., & Fortunato, S. (2024). Characterizing and modeling citation dynamics. PLoS ONE, 19(3), e0302104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fredrich, V., Gudergan, S. P., & Bouncken, R. B. (2022). Dynamic capabilities, internationalization and growth of small- and medium-sized enterprises: The roles of research and development intensity and collaborative intensity. Management International Review, 62, 611–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fricker, M. (2007). Epistemic injustice: Power and the ethics of knowing. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Giordano, G., Misuraca, M., & Restaino, M. (2025). Evaluating the speed of citation in scientific journals: A survival analysis-based approach. Journal of Informetrics, 19(3), 101714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glänzel, W., & Schoepflin, U. (1995). A bibliometric study on aging and reception processes of scientific literature. Journal of Information Science, 21(1), 37–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Tamayo, L. A., Maheshwari, G., Bonomo-Odizzio, A., Herrera-Avilés, M., & Krauss-Delorme, C. (2023). Factors influencing small and medium size enterprises development and digital maturity in Latin America. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, 9(2), 100069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, W., & Duarte, A. E. (2024). Bibliometric analysis: A few suggestions. Current Problems in Cardiology, 49(8), 102640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, F., Ma, L., Zhan, X.-X., Zhou, Y., Liu, C., Zhao, H., & Zhang, Z.-K. (2021). The aging effect in evolving scientific citation networks. Scientometrics, 126(5), 4297–4309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kousha, K., & Thelwall, M. (2024). Factors associating with or predicting more cited or higher quality journal articles: An Annual Review of Information Science and Technology (ARIST) paper. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 75(3), 215–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamont, M. (2010). How professors think: Inside the curious world of academic judgment. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Larivière, V., Archambault, É., & Gingras, Y. (2008). Long-term variations in the aging of scientific literature: From exponential growth to steady-state science (1900–2004). Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 59(2), 288–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latour, B. (1987). Science in action: How to follow scientists and engineers through society. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Line, M. B., & Sandison, A. (1974). “Obsolescence” and changes in the use of literature with time. Journal of Documentation, 30(3), 283–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loui, M., & Fiala, S. C. (2024). Inequities in academic publishing: Where is the evidence and what can be done? American Journal of Public Health, 114(4), 377–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, J., Romo, L., & Riascos, S. (2024). Avances en la transformación digital de las MiPymes impulsadas por la pandemia COVID-19. Journal of Technology Management & Innovation, 19(1), 52–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merton, R. K. (1968). The Matthew effect in science. Science, 159(3810), 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Doherty, D. (1990). Strategic alliances—An SME and small economy perspective. Science and Public Policy, 17(5), 303–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passas, I. (2024). Bibliometric analysis: The main steps. Encyclopedia, 4(2), 1014–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Põder, E. (2022). What is wrong with the current evaluative bibliometrics? Frontiers in Research Metrics and Analytics, 6, 824518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reim, W., Yli-Viitala, P., Arrasvuori, J., & Parida, V. (2022). Tackling business model challenges in SME internationalization through digitalization. Journal of Innovation & Knowledge, 7(3), 100199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suresh, K., Severn, C., & Ghosh, D. (2022). Survival prediction models: An introduction to discrete-time modeling. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 22(1), 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H., Huang, W.-b., & Bu, Y. (2025). The attention inequality of scientists: A core-periphery structure perspective. Information Processing & Management, 62(4), 104170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worrall, J. L., & Cohn, E. G. (2023). Citation data and analysis: Limitations and shortcomings. Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice, 39(3), 327–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q., Shen, X., Song, Y., & Chen, S. (2024). A study of the impact of interdisciplinary citation on the aging of library and information science. Library Hi Tech, 42(5), 1634–1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasui, Y., & Nakano, J. (2022). A stochastic generative model for citation networks among academic papers. PLoS ONE, 17(6), e0269845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- You, C., Awang, S. R., & Wu, Y. (2024). Bibliometric analysis of global research trends on higher education leadership development using Scopus database from 2013–2023. Discover Sustainability, 5, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).