Abstract

Solid base catalysts hold significant promise for replacing traditional homogeneous bases with green chemical processes. However, the construction of their strong basic sites typically relies on high-temperature calcination, which often leads to the collapse of the carrier structure and high energy consumption. This study proposes a novel “carrier reducibility tuning” strategy, which involves endowing the carrier with intrinsic reducibility to induce the low-temperature decomposition of alkali precursors via a redox pathway, thereby enabling the mild construction of strong basic sites. Low-valence Cr3+ was doped into a mesoporous zirconia framework, successfully fabricating an MCZ carrier with a mesostructure and reducible characteristics. Characterization results indicate that a significant redox interaction between the Cr3+ in the carrier and the supported KNO3 occurs at 500 °C. This interaction facilitates the complete conversion of KNO3 into highly dispersed, strongly basic K2O species, while Cr3+ is predominantly oxidized to Cr6+. This activation temperature is approximately 300 °C lower than that required for the conventional thermal decomposition pathway and effectively preserves the structural integrity of the material. In the transesterification reaction for synthesizing dimethyl carbonate, the prepared catalyst exhibits superior catalytic activity, significantly outperforming classic solid bases like MgO and other reference catalysts.

1. Introduction

Catalysts are indispensable in the chemical industry, with over 90% of chemical processes relying on their use. Among them, solid base catalysts represent a crucial class of heterogeneous catalytic materials, attracting significant attention for replacing traditional homogeneous bases [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8]. They offer distinct advantages such as facile product separation, reduced equipment corrosion, and lower waste generation [9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16]. These merits make them highly promising for important reactions including transesterification, Knoevenagel condensation, and Michael addition. Substantial progress has been made in the development of solid base catalysts over the past decades [17,18,19,20,21,22,23]. For instance, novel catalysts have been prepared through strategies like nitrogen-doping or grafting organic basic groups onto supports [24]. However, these methods often suffer from complex procedures, high costs, and most critically, the resulting materials typically exhibit only moderate basicity. To achieve stronger basicity, alternative approaches focus on introducing strong basic species (e.g., K2O) into porous carriers. A common method involves loading alkali precursors like KNO3 onto supports such as Al2O3 or mesoporous silica SBA-15, followed by high-temperature thermal treatment. For example, complete conversion of KNO3 to active sites requires calcination at approximately 700 °C on Al2O3 and around 750 °C on SBA-15 [11,25,26,27].

Unfortunately, such harsh activation conditions lead to inevitable drawbacks: (1) collapse or sintering of the mesoporous support structure, causing a drastic decrease in surface area and mass transfer limitations; and (2) high energy consumption, which increases costs and hinders industrial scalability. Therefore, developing a novel strategy to construct strong basic sites under relatively mild conditions while preserving the structural integrity of the support remains a critical and unresolved challenge.

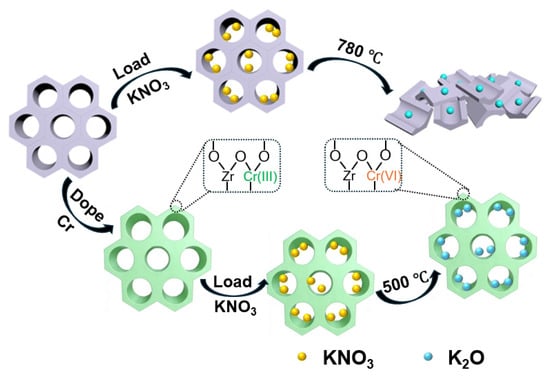

In this study, we propose an innovative “reducibility tuning” strategy. The core concept is to endow the carrier with inherent reducibility, creating a redox environment between the host (carrier) and guest (precursor). This environment is designed to promote the decomposition of the alkali precursor via a redox reaction pathway at a significantly lower temperature. The ongoing development of advanced inorganic materials for energy and chemical conversion applications underscores the importance of tailored material design in modern catalysis [28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37]. Zirconia (ZrO2), known for its high melting point, low thermal conductivity, and excellent corrosion resistance, serves as an attractive catalyst support [38]. We successfully constructed a reductible carrier by incorporating low-valence Cr3+ ions into a mesoporous zirconia framework (Scheme 1). Characterization results reveal that the introduced Cr3+ not only stabilizes the structure but also strongly interacts with the loaded KNO3. This redox interaction enables the complete decomposition of KNO3 at 500 °C, which is approximately 300 °C lower than the temperature required by conventional thermal decomposition routes on undoped supports (e.g., >780 °C). Multiple characterization techniques confirm that during this low-temperature activation, Cr3+ is predominantly oxidized to Cr6+, while KNO3 is reduced and transformed into highly dispersed, strongly basic K2O species. This mechanism fundamentally differs from the traditional thermal cracking process widely reported in the literature. The resulting solid strong base catalyst possesses a series of porous structures and abundant strong basic sites. It demonstrates superior catalytic performance in the model transesterification reaction for dimethyl carbonate synthesis, outperforming classic solid bases like MgO and other reported benchmark catalysts.

Scheme 1.

Schematic Illustration of the Contrasting KNO3 Conversion Pathways on ZrO2 versus Cr-Doped MCZ Supports.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Mechanism of Low-Temperature KNO3 Decomposition

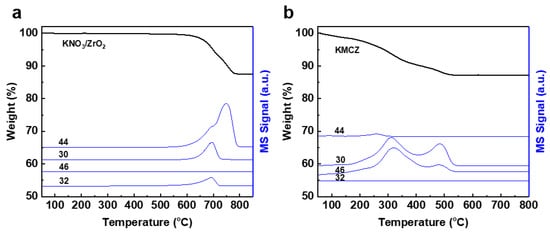

Understanding the activation pathway of the KNO3 precursor is crucial, as it directly determines the formation temperature of strong basic sites (K2O) and the structural integrity of the support. We employed thermogravimetric analysis coupled with mass spectrometry (TG-MS) to probe the thermal decomposition process in situ, simultaneously monitoring weight loss and the evolution of gaseous products. The MS signals for characteristic fragments of NO (m/z = 30), O2 (m/z = 32), N2O (m/z = 44), and NO2 (m/z = 46) were tracked to elucidate the decomposition mechanism [39,40].

Figure 1a presents the TG-MS profiles for KNO3 supported on undoped mesoporous zirconia (K/ZrO2). A single weight-loss step is observed, centered at approximately 780 °C. This high-temperature event corresponds to the conventional thermal cracking of KNO3. The concomitant MS signals show the primary release of NO, N2O, and O2, confirming a decomposition pathway dominated by simple thermal energy input, which inevitably risks sintering the ZrO2 framework. In striking contrast, the KNO3-loaded, Cr-doped zirconia sample (KMCZ) exhibits a profoundly different profile (Figure 1b). The decomposition occurs in two distinct, sequential steps at significantly lower temperatures (350 °C and 500 °C). The drastic reduction in the onset temperature by over 300 °C unambiguously demonstrates that the presence of Cr3+ ions in the zirconia lattice catalyzes the decomposition process. More importantly, the composition of the evolved gases shifts notably. While NO and N2O are still detected, the signal for O2 has substantially disappeared, and a pronounced release of NO2 is observed. This shift in product distribution from O2 to NO2 is a critical indicator of a changed chemical pathway, which is consistent with a change from a mere thermal dissociation to a redox process involving Cr3+. The distinct product profiles point to two different overall reaction stochiometries. On the inert ZrO2 support, decomposition likely follows a classic thermal dissociation path approximated by:

6KNO3 → 3K2O + 4NO + N2O + 5O2

Figure 1.

TG-MS analysis of (a) K/ZrO2, (b) KMCZ samples. The m/z value of 44, 30, 46, and 32 in MS signal corresponds to N2O, NO, NO2, and O2, respectively.

Conversely, on the reducible MCZ support, Cr3+ acts as a reducing agent. We propose that KNO3 (where N is in the +5-oxidation state) is reduced, leading to the formation of NO2 (where N is in the +4-oxidation state), while Cr3+ is simultaneously oxidized to Cr6+ (likely in the form of CrO3). Based on the observed gaseous products and the oxidation state change of Cr, a plausible redoxmediated conversion can be represented by the following balanced stoichiometry:

8 KNO3 + 3Cr2O3 → 4 K2O + 6 CrO3 + 2NO + N2O + 4 NO2

This stoichiometry is mass- and charge-balanced. The specific mixture of gaseous nitrogen oxides (NO, N2O, NO2) is consistent with the non-catalytic reductive decomposition pathways of nitrate and, crucially, is directly evidenced by the TG-MS profiles in Figure 1b. The significant production of NO2 alongside the suppression of O2 evolution is a key feature distinguishing the proposed redox pathway from the simple thermal decomposition described by Equation (1). The two-stage weight loss in KMCZ may correspond to the sequential decomposition of KNO3 interacting with Cr sites of different accessibility or the stepwise formation of different intermediate species. This low-temperature, redox-driven mechanism is the cornerstone of our strategy, as it enables the generation of active K2O species while preserving the mesoporous host structure from high-temperature damage.

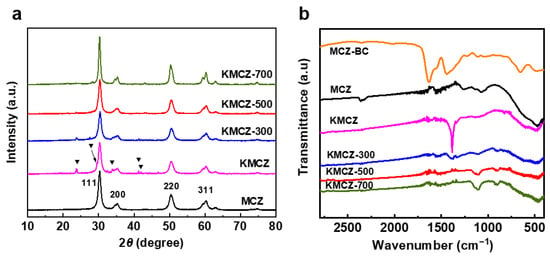

To monitor the crystalline phase evolution during the synthesis and activation process, XRD was performed on a series of samples, and the results are presented in Figure 2a. For the support MCZ, distinct diffraction peaks are observed at 2θ = 30.3°, 35.3°, 50.4°, and 60.2°. These peaks can be indexed to the (111), (200), (220), and (311) crystal planes of tetragonal zirconia (t-ZrO2, JCPDS No. 17-0923), respectively, confirming the successful formation of a crystalline framework after calcination at 600 °C [41]. Upon loading the KNO3 precursor onto the Cr-doped support (sample KMCZ), new diffraction peaks emerge at 23.9°, 29.4°, 33.9°, 41.1°, and 42.0°. These peaks are characteristic of crystalline, orthorhombic-phase KNO3 (JCPDS No. 15-0607) [42,43], indicating that the impregnation process deposited KNO3 in a well-crystallized form on the MCZ surface. After activation at 300 °C under N2 (sample KMCZ-300), the characteristic peaks of KNO3 remain clearly visible, albeit with reduced intensity. This suggests that only a minor fraction of KNO3 has decomposed at this temperature, consistent with the initial weight-loss step observed in the TG-MS analysis. For samples activated at 500 °C and 700 °C (KMCZ-500 and KMCZ-700), all diffraction peaks corresponding to crystalline KNO3 completely disappear. This provides direct evidence that KNO3 is fully converted on the MCZ support by 500 °C. Together, these data conclusively demonstrate that the incorporation of Cr3+ drastically promotes the conversion of KNO3, lowering the required temperature by nearly 300 °C compared to its decomposition on undoped zirconia. It is interesting to note that no diffraction peaks assignable to Cr2O3 were observed in all the samples. This suggests that the Cr3+ ions are not aggregated into separate nanoparticles or bulk oxide crystallites on the surface. Instead, they are successfully incorporated into the zirconia lattice, likely substituting for Zr4+ ions, forming a solid solution. This high dispersion and integration of Cr species within the support framework are crucial for creating the uniform redox-active sites necessary for the low-temperature, interactive decomposition of KNO3.

Figure 2.

(a) Wide-angle XRD, (b) FT-IR spectra of series samples.

FT-IR spectroscopy was employed to monitor the removal of organic templates and the evolution of the nitrate precursor. As shown in Figure 2b, the spectrum of the as-synthesized material before calcination shows characteristic bands at 1640 and 1540 cm−1, attributable to amide groups from the CAPB template, and a band at 1120 cm−1 from the C-O-C stretching vibration of the P123 template. After calcination at 600 °C to obtain the MCZ support, these bands completely disappear, confirming the thorough removal of the organic structure-directing agents. Concurrently, two new bands emerge at approximately 600 and 510 cm−1, which are characteristic of the tetragonal phase of zirconia [44,45]. Upon loading KNO3 (sample KMCZ), a strong, sharp band appears at 1383 cm−1, which is assigned to the N−O stretching vibration of the nitrate ion (NO3−) [46]. After activation at 300 °C (KMCZ-300), the intensity of this nitrate band diminishes but remains clearly detectable, indicating the partial decomposition of KNO3 at this temperature. Crucially, upon activation at 500 °C and 700 °C (KMCZ-500 and KMCZ-700), this characteristic nitrate band vanishes entirely. This FT-IR evidence directly confirms the complete decomposition of KNO3 on the MCZ support by 500 °C, consistent with the XRD and TG-MS findings, and further reinforces the promoting role of Cr in enabling low-temperature conversion.

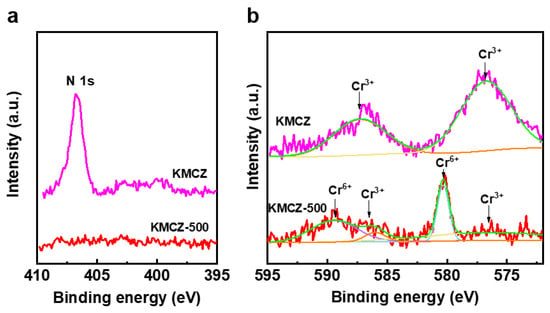

XPS analysis provided direct chemical-state evidence for the proposed redox mechanism. The N 1s spectra are displayed in Figure 3a. For the KMCZ precursor, a distinct peak is observed at a binding energy of 406.7 eV, which is characteristic of nitrogen in the nitrate species [47]. After activation at 500 °C (KMCZ-500), this N 1s peak completely disappears, providing definitive proof that the KNO3 precursor has been fully converted, with no residual nitrate detectable on the surface. The corresponding changes in the chemical state of chromium were tracked using the Cr 2p spectra (Figure 3b). For the KMCZ precursor, the Cr 2p3/2 and Cr 2p1/2 peaks are located at BEs of 576.7 eV and 587.1 eV, respectively, consistent with the presence of Cr3+ species [4,48]. After activation at 500 °C, the Cr 2p spectrum is dominated by new peaks at binding energies of 580.2 eV and 589.4 eV, characteristic of Cr6+ [49]. This significant shift of approximately 3.5 eV relative to the precursor positions, along with the drastic reduction in the original Cr3+ signals, provides definitive evidence for the predominant oxidation of Cr3+ to Cr6+. This major chemical state change of chromium, concurrent with the complete disappearance of nitrate nitrogen, offers direct spectroscopic confirmation of the redox reaction pathway expressed in Equation (2).

Figure 3.

XPS spectra of different samples. (a) N 1s and (b) Cr 2p before and after calcination.

The oxidation state change of chromium is accompanied by a distinct visual color transition, as shown in the photographic images of the samples (Figure 4). The K/MCZ precursor exhibits a dark yellowish-brown color, typical of Cr3+-containing compounds. As the activation temperature increases, the color of the catalysts progressively lightens. Samples activated at 500 °C and above turn into a light-yellow hue, which is characteristic of Cr6+ species. This macroscopic color change provides intuitive, supporting evidence for the oxidation of Cr3+ to Cr6+ during the activation process.

Figure 4.

Digital photos of (a) KMCZ, (b) KMCZ-300, (c) KMCZ-500 and (d) KMCZ-700.

2.2. Structural Characteristics of the Resultant Materials

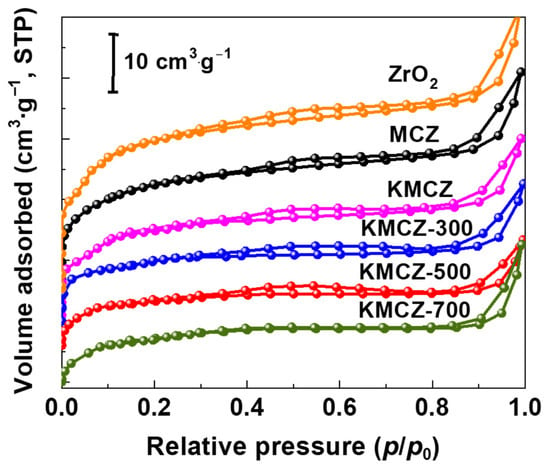

N2 adsorption–desorption analysis was performed on a series of samples. The corresponding isotherm curves are presented in Figure 5, and key parameters are summarized in Table 1. The N2 adsorption–desorption isotherm of the mesoporous Cr-doped zirconia support (MCZ) exhibits a combination of a Type I isotherm with a distinct H1-type hysteresis loop. The sharp uptake at low relative pressure (P/P0 < 0.1) indicates the presence of some microporosity. The pronounced hysteresis loop in the P/P0 range of 0.4–0.7 confirms the existence of mesopores. The specific surface area of the MCZ support was 129 m2·g−1. The undoped ZrO2 support exhibited a comparable BET surface area (131 m2·g−1) and similar mesoporous characteristics to the MCZ support, confirming that the incorporation of Cr3+ did not significantly alter the baseline textural properties of the host matrix. After the impregnation of KNO3 and subsequent activation at different temperatures, the resulting KMCZ catalysts retained isotherms similar in shape to that of the MCZ support. This observation provides that the proposed low-temperature redox activation strategy successfully preserved the mesoporous framework of support, avoiding the pore collapse typically induced by conventional high-temperature calcination. As listed in Table 1, the specific surface area decreased to 118 m2·g−1, which can be attributed to the deposition of KNO3 crystals within the pores, increasing pore wall roughness and potentially causing partial pore blocking. When activated at 500 °C, the specific surface area of sample KMCZ-500 reached 98 m2·g−1, even slightly exceeding that of the ample KMCZ-300. We attribute this to the complete decomposition of KNO3, which generated highly dispersed K2O active species, thereby clearing the pores of previously space-occupying bulk KNO3 crystals and restoring pore accessibility. However, upon further increasing the activation temperature to 700 °C, the specific surface area of KMCZ-700 decreased to 23 m2·g−1. This indicates that the onset of partial sintering and coarsening of the pore walls at this elevated temperature underscores the importance of maintaining the activation temperature below 500 °C for optimal properties.

Figure 5.

N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms of the samples.

Table 1.

Performance parameters of different samples.

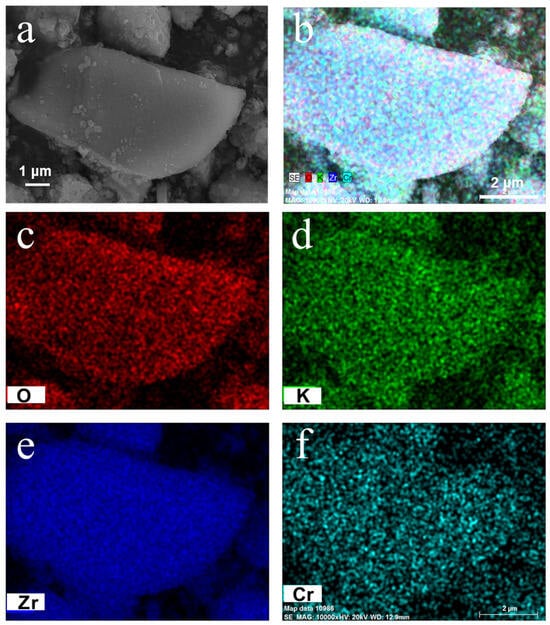

The KMCZ-500 catalyst was further visualized by SEM and corresponding EDX mapping. The SEM images (Figure 6a) reveal that the material exhibits a loose and porous morphology. More critically, the EDX elemental mapping results (Figure 6b–f) clearly demonstrate a highly homogeneous distribution of zirconium (Zr), oxygen (O), potassium (K), and chromium (Cr) throughout the observed area, with no noticeable regions of elemental aggregation or segregation. This provides that the Cr species were successfully and uniformly incorporated into the zirconia matrix, rather than existing as separate chromium oxide phases, which is fully consistent with the absence of impurity peaks in the XRD patterns. The homogeneous distribution of K also confirms the excellent dispersion of the active K2O component on the support surface, which is crucial for exposing abundant basic sites. It is noteworthy that long-range, highly ordered two-dimensional hexagonal mesopores were not observed via TEM. We attribute this to two probable factors. First, the doping of Cr3+ ions may have subtly altered the co-assembly driving force between the zirconia precursor and the template, affecting the final regularity of the mesostructure. Second, the relatively thin walls of the mesoporous zirconia might be susceptible to partial structural damage during the ultrasonic dispersion required for TEM sample preparation and under irradiation by the high-energy electron beam, making it difficult to resolve perfect periodic features. Nevertheless, by combining the long-range crystalline phase confirmed by XRD, the mesoporous texture determined by N2 physisorption, and the atomic-level homogeneity of elements demonstrated by EDX mapping, we can confidently conclude that the synthesized KMCZ catalysts successfully achieved uniform loading of active components and effective preservation of the mesoporous framework, providing a solid structural foundation for their exceptional catalytic performance.

Figure 6.

(a) SEM and (b–f) EDX-mapping of the sample KMCZ-500.

2.3. Basic Properties and Catalytic Performance

The concentration and strength of basic sites are fundamental properties determining the efficacy of a solid base catalyst. The total number of basic sites was first quantified via acid-base titration (Table 1). The bare MCZ support exhibited negligible basicity, confirming its chemical inertness as a host matrix. The KNO3-loaded but unactivated precursor (KMCZ) showed a similarly minimal value of 0.11 mmol·g−1, demonstrating that simple impregnation does not generate active sites. Activation at 300 °C (KMCZ-300) increased the basicity to 0.82 mmol·g−1, corresponding to the partial decomposition of KNO3 observed by TG-MS and XRD. A decisive increase occurred at 500 °C: KMCZ-500 reached a basicity of 1.95 mmol·g−1, which is in excellent agreement with the theoretical value of 1.98 mmol·g−1 calculated for the complete conversion of all loaded KNO3 to K2O. The quantitative agreement between the measured basicity and the theoretical value for K2O formation, combined with the high-temperature CO2desorption profile and the absence of crystalline carbonate/hydroxide phases in XRD strongly supports that the generated active phase is highly dispersed K2O. This quantitative match provides compelling evidence that the redox interaction on the Cr-doped support facilitates full precursor conversion at this atypically low temperature. Notably, activation at 700 °C (KMCZ-700) yielded a comparable basicity (1.92 mmol·g−1), proving that conversion remains complete even under conditions that induce textural sintering. This decoupling of chemical conversion from structural stability underscores that while the redox mechanism ensures low-temperature KNO3 decomposition, excessive heat remains detrimental to the porous architecture.

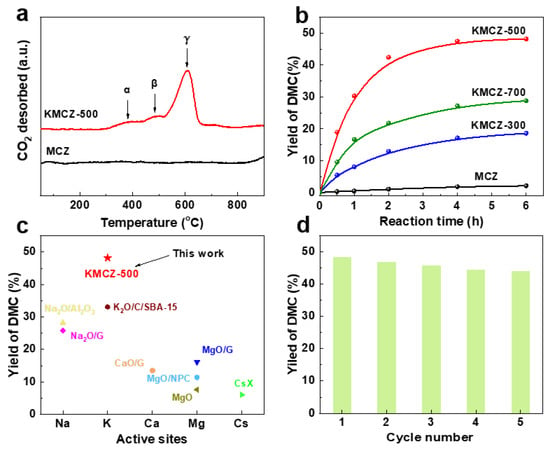

The strength distribution of the basic sites was probed by CO2 temperature-programmed desorption (CO2-TPD), as shown in Figure 7a. The profile for the MCZ support showed no significant CO2 desorption, confirming its lack of basicity. In contrast, the CO2-TPD profile of the optimally activated KMCZ-500 catalyst revealed three distinct desorption peaks at 385 °C, 485 °C, and 610 °C. These peaks are designated as α, β, and γ sites, corresponding to medium-strength, strong, and very strong basic sites, respectively [25]. The presence of the high-temperature γ peak confirms the generation of very strong basic sites, which are highly desirable for demanding base-catalyzed reactions and underscore the effectiveness of our activation strategy.

Figure 7.

(a) CO2-TPD profiles of the samples MCZ and KMCZ-500; (b) The yields of DMC under the catalysis of different samples; (c) comparison of catalytic activity with typical reported solid bases; (d) Reusability of the KMCZ-500 as the catalyst for the synthesis of DMC.

The catalytic prowess of the synthesized materials was evaluated in the transesterification of ethylene carbonate with methanol to produce DMC—a pivotal green chemical and fuel additive [50,51]. This reaction serves as a benchmark for solid base catalysts [52,53]. It should be noted that the present study focuses on demonstrating catalytic performance based on DMC yield; a detailed carbon balance analysis quantifying all reaction by-products falls beyond its scope but represents a valuable objective for future mechanistic investigations. The performance trends (Figure 7b) directly mirror the physicochemical characterization data, revealing clear structure-activity relationships. The inert MCZ support yielded only 2.1% DMC after 6 h. The partially activated KMCZ-300 showed moderate activity (18.6% yield), which correlates linearly with its lower basic site density (0.82 mmol·g−1). The optimally activated KMCZ-500 delivered the highest DMC yield of 48.2%, a direct consequence of its combined advantages: the highest density of strong basic sites (1.95 mmol·g−1) and a well-preserved, accessible mesoporous network. The case of KMCZ-700 is particularly instructive. Despite possessing a near-identical total basicity (1.92 mmol·g−1) to KMCZ-500, its catalytic yield plummeted to 28.8%. This significant drop in activity, despite comparable site numbers, is attributed to the severe textural degradation observed via N2 physisorption (SBET = 23 m2·g−1). The collapsed porosity likely impedes mass transport, burying a fraction of the active sites and making them inaccessible to reactant molecules. This result highlights a critical principle: for porous solid catalysts, accessibility is as crucial as intrinsic activity.

The superiority of KMCZ-500 was cemented through benchmarking against a range of representative solid base catalysts reported for the same reaction (Figure 7c). Its performance far surpassed that of classic metal oxides like MgO (7.6% yield) and modified systems such as MgO/NPC (11.4%), CaO/γ-Al2O3 (13.5%), and Na2O/Al2O3 (28.2%). It also outperformed various advanced carbon-based catalysts and even a strongly basic CsX zeolite (6.0% yield) [21,25,26,54,55,56,57]. This comprehensive comparison underscores that our catalyst is not merely an incremental improvement but represents a significant advance in solid base design.

Finally, practical applications demand stability. The reusability of KMCZ-500 was tested over five consecutive reaction cycles (Figure 7d). After a minor initial decrease, the DMC yield stabilized at approximately 42% from the second cycle onward, retaining about 87% of its initial activity. This demonstrates excellent operational stability. The slight deactivation may be attributed to minor leaching of active species or subtle surface reconstruction during the first cycle. The sustained high activity thereafter confirms the robustness of the catalyst’s framework and the strong anchoring of the active sites, validating their potential for sustainable catalytic processes.

The formation of Cr (VI) during the activation process necessitates a discussion on environmental and safety aspects for practical application. While this redox state is integral to the proposed low-temperature activation mechanism, its potential leaching and stability under operating conditions are important. It should be noted that the subsequent transesterification reaction is conducted in a strongly reductive medium (methanol) over a strongly basic catalyst. Chromium (VI) is known to be unstable under such reductive conditions and is readily reduced to Cr (III), which has significantly lower solubility and toxicity. Although a dedicated leaching analysis was not performed in this foundational study, the inherent reaction environment suggests a low propensity for Cr (VI) persistence or leakage. The demonstrated good structural and catalytic stability indirectly supports this assessment. For future practical applications, detailed leaching tests (e.g., ICP-MS analysis of post-reaction mixtures) and the design of catalyst encapsulation or stabilization strategies would be essential next steps to ensure full environmental compatibility.

3. Experimental Section

3.1. Chemicals

Ultrapure water was used to prepare all solutions. The main reagents, used as supplied, included zirconyl chloride octahydrate (ZrOCl2·8H2O, 98%); Pluronic P123; Cocamidopropyl betaine (CAPB); Chromium (III) nitrate nonahydrate (Cr(NO3)3·9H2O, 99%); and potassium nitrate (KNO3, 99%).

3.2. Synthesis of Cr-Doped Mesoporous Zirconia

Mesoporous Cr-doped zirconia was synthesized via an evaporation-induced co-assembly method. The zirconium precursor solution (0.25 mol·L−1) was prepared by dissolving 2.73 g of ZrOCl2·8H2O in 30 mL of deionized water; separately, 1.0 g of Pluronic P123 and 0.29 g of CAPB (nZr/nCAPB = 1) were dissolved in 10 g of deionized water under stirring to obtain the templating solution. The molar ratio of Zr to P123 was fixed at 100. The templating solution was then added dropwise into the ZrOCl2 solution at 40 °C under magnetic stirring. After stirring for 30 min to allow preliminary interaction between Zr4+ ions and the template micelles, an aqueous solution of Cr(NO3)3 (nZr/nCr = 5) was introduced dropwise. The resulting mixture was stirred vigorously for 4 h. Subsequently, the pH of the mixture was adjusted to 5, followed by continued stirring for another 3 h. The homogeneous gel was transferred into a 50 mL Teflon-lined autoclave and subjected to hydrothermal treatment at 80 °C for 56 h. The resulting solid product was collected by filtration, washed thoroughly with deionized water until the filtration was neutral, and dried at 80 °C for 12 h. Finally, the sample was calcined at 600 °C for 4 h in air to remove the organic templates and crystallize the framework. The material obtained was denoted as MCZ. For comparison, an undoped mesoporous zirconia support (denoted as ZrO2) was synthesized using the identical procedure detailed above, but without the addition of the Cr(NO3)3 solution.

3.3. Preparation of Solid Base Catalysts

The MCZ-supported catalysts were prepared by wet impregnation. Typically, 0.8 g of the MCZ support was introduced into an aqueous solution containing 0.2 g of dissolved KNO3 (corresponding to 20 wt.% of the final catalyst in 10 g of deionized water). The mixture was subjected to continuous magnetic stirring for 12 h at ambient temperature. Subsequently, water was removed by evaporation in a water bath maintained at ~75 °C, and the resulting solid was dried overnight at 80 °C to obtain the precursor, denoted as K/MCZ. Activation was carried out by calcining the KMCZ precursor under a N2 atmosphere at 300, 500, or 700 °C for 4 h, yielding the final catalysts designated as KMCZ-300, KMCZ-500, and KMCZ-700, respectively.

3.4. Materials Characterization

Powder X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis was conducted using a Bruker D8 Advance diffractometer (Bruker, Billerica, MA, USA) equipped with a Cu Kα radiation source (λ = 1.5418 Å). The diffraction patterns were systematically recorded in the 2θ range of 10–80°under operational parameters of 40 kV and 40 mA. Textural properties were quantitatively evaluated through N2 physisorption measurements at 77 K using a BSD-660 (BSD Instrument, Beijing, China). Prior to analysis, the samples were degassed under high vacuum condition at 150 °C for 2 h. Fourier transform infrared (FT-IR) spectroscopic measurements were performed on a Nicolet AVATAR-360 spectrometer (Thermofisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Catalyst and KBr were prepared by pressing a mixture of 1.5 mg of catalyst and 225 mg of dried KBr into a transparent pellet. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) was performed on a Thermo Fisher Scientific Talos F200X instrument (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was conducted using Hitachi Regulus8100 microscope (Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan). X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) measurements were carried out on a Thermo Scientific K-Alpha+ spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, East Grinstead, UK) using a monochromatic Al Kα X-ray source. The binding energy scale was referenced to the adventitious carbon C 1s peak at 284.8 eV [58]. Given the strong basicity, surface reaction with atmospheric CO2/H2O during transfer for ex situ analysis is possible. Thermogravimetric analysis coupled with mass spectrometry (TG-MS) was performed using a NETZSCH STA 449 F5 Jupiter thermal analyzer (NETZSCH-Gerätebau GmbH, Selb, Germany) connected to a QMS 403 D Aëolos quadrupole mass spectrometer (NETZSCH-Gerätebau GmbH). CO2 temperature-programmed desorption (CO2-TPD) was performed using a BELCAT-A analyzer (Micromeritics Instrument Corporation, Norcross, GA, USA) coupled with a Hiden HAL 201 mass spectrometer (Hiden Analytical Ltd., Warrington, UK) for gas analysis. Typically, 50 mg of the catalyst was loaded into a quartz tube and pretreated under a 20 mL·min−1 argon flow by heating to 500 °C (10 °C·min−1) and holding for 3 h, then cooled to 50 °C. The sample was subsequently exposed to a 10 vol% CO2/Ar mixture (total flow: 20 mL·min−1) at 50 °C for 1 h for adsorption. After adsorption, physically bound CO2 was removed by purging with argon at 50 °C for 1 h. The TPD profile was recorded by heating the sample from 50 °C to 900 °C at a ramp rate of 10 °C·min−1 under argon flow (20 mL·min−1). The MS signal for m/z = 44 (CO2) was monitored continuously. The total number of basic sites was measured by acid-based back-titration and is reported in mmol per gram of catalyst. The solid catalyst (50 mg) was first treated with 10 mL of 0.05 M HCl solution and agitated for 24 h to allow complete reaction of the basic sites. The remaining HCl in the filtrate was then titrated against a standardized 0.01 M NaOH solution using phenolphthalein as an indicator. The total basicity was derived from the consumption of HCl.

3.5. Catalytic Tests

The transesterification of ethylene carbonate (EC) and methanol to synthesize dimethyl carbonate (DMC) served as a model reaction to assess the catalytic performance. A standard experiment was performed by combining 0.5 mol of methanol, 0.1 mol of EC, and the activated catalyst (0.5 wt.% relative to methanol) in a 100 mL three-neck flask fitted with a condenser and a magnetic stirrer. The reactions were conducted with magnetic stirring at a constant rate of 500 rpm. A preliminary test confirmed that the initial reaction rate became independent of stirring speed above 500 rpm, indicating the absence of external liquid-solid mass transfer limitations under the employed conditions. The mixture was reacted at 65 °C under atmospheric pressure. At predetermined intervals (0.5, 1, 2, 4, and 6 h), approximately 0.2 mL aliquots were extracted from the reaction mixture. These samples were promptly centrifuged for catalyst separation. The resulting clear liquid was analyzed by gas chromatography (Agilent 7890A, Agilent Technologies Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA) using an HP-5 capillary column and a flame ionization detector (FID). The conversion of EC and the yield of DMC were determined via GC analysis using external calibration. The selectivity to DMC is defined relative to the converted EC. The DMC yield, calculated as the product of EC conversion and DMC selectivity, is reported as the key metric for catalytic performance in the target synthesis. Prior to each catalytic test, the catalyst was activated in situ under a nitrogen flow in a tubular furnace at the target temperature (e.g., 500 °C for KMCZ-500) for 4 h. After cooling under nitrogen to near ambient temperature, the freshly activated catalyst was promptly transferred and charged into the reaction vessel. Although this transfer involved brief exposure to ambient atmosphere, it represents a pragmatic handling condition relevant to potential application.

4. Conclusions

This study successfully demonstrates a “carrier reducibility tuning” strategy for the low-temperature construction of efficient solid strong base catalysts. By doping Cr3+ into a mesoporous zirconia framework, a reductible MCZ carrier was synthesized. A strong redox interaction between this carrier and the supported KNO3 precursor enabled the complete conversion of KNO3 at 500 °C. Systematic characterization confirmed that during this low-temperature activation, Cr3+ was predominantly oxidized to Cr6+, while KNO3 was reductively decomposed, generating highly dispersed strong basic sites. The resulting catalyst exhibited superior activity and stability in the transesterification synthesis of dimethyl carbonate (DMC), outperforming several conventional solid base catalysts. Beyond presenting a high-performance catalyst, this work provides a novel methodology for low-temperature catalyst preparation and offers a fresh perspective on regulating active site formation through the rational design of carrier–precursor interfacial chemistry. Future work should include in situ spectroscopic studies to directly probe the evolution of potassium species during activation, which would provide further mechanistic insight.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.L., H.Z. and D.X.; methodology, T.L., X.L. (Xiaowen Li), H.W., Q.C. and H.Z.; software, H.W., Q.C. and X.L. (Xiaochen Lin); validation, X.L. (Xiaowen Li), Q.C. and H.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, T.L., X.L. (Xiaowen Li) and H.W.; writing—review and editing, T.L., X.L. (Xiaochen Lin) and D.X.; funding acquisition, T.L. and H.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Unveiled Project of Xuzhou College of Industrial Technology (XGY2025ZXJB02) and the grants from the Engineering Laboratory of High Efficiency and Comprehensive Utilization of Biochemical Resources in Xuzhou (XZGCSYS008).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Tao, Y.; Guan, J.; Zhang, J.; Hu, S.; Ma, R.; Zheng, H.; Gong, J.; Zhuang, Z.; Liu, S.; Ou, H. Ruthenium single atomic sitessurrounding the support pit with exceptional photocatalytic activity. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2024, 63, e202400625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.; Zhu, X.; Pei, X.; Liu, W.; Leng, Y.; Yu, X.; Wang, C.; Hu, L.; Su, Q.; Wu, C. Room-temperature laser planting of high loading single-atom catalysts for high-efffciency electrocatalytic hydrogen evolution. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 13788–13795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Wang, P.; Song, C.; Zhang, T.; Zhan, S.; Li, Y. Enhanced interfacial electron transfer by asymmetric Cu-Ov-In Sites on In2O3 for efffcient peroxymonosulfate activation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202216403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Zhu, L.; Jiang, Y.; Liu, X.Q.; Sun, L.B. Direct fabrication of strong basic sites on ordered nanoporous materials: Exploringthe possibility of metal–organic frameworks. Chem. Mater. 2018, 30, 1686–1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, D.-M.; Zhu, G.-L.; Yan, X.-F.; Liu, M.-Q.; Krishna, R.; Zhang, H.-H.; Cai, R.-S. Amine-functionalized pillar-layered metal-organic frameworks for multicomponent natural gas purification with high-methane productivity and n-C4H10 Productivity. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2026, 14, 428–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, T.; Liu, R.; Cai, J.; Cheng, X.; He, Z.; Zhao, Z. Breaking structural symmetry of atomically dispersed Co sites for boosting oxygen reduction. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, e22046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Du, S.; Huang, Z.; Liu, N.; Shao, Z.; Qin, N.; Wang, Y.; Wang, H.; Ni, Z.; Yang, L. Enhanced reduction of nitrate to ammonia at the Co-N heteroatomic interface in MOF-derived porous carbon. Materials 2025, 18, 2976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, C.; Xu, Y.; Deng, N.; Huang, X. Efficient degradation of organophosphorus pesticides and in situ phosphate recovery via NiFe-LDH activated peroxymonosulfate. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 524, 169107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.; Zhao, J.; Li, X.; Shao, J.; Pan, B.; Salam, A.; Boutin, E.; Groizard, T.; Wang, S.; Ding, J. In-situ spectroscopic probe of the intrinsic structure feature of single-atom center in electrochemical CO/CO2 reduction to methanol. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 3401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Liu, X.Q.; Jiang, H.L.; Sun, L.B. Metal-organic frameworks for heterogeneous basic catalysis. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 8129–8176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, L.B.; Liu, X.Q.; Zhou, H.C. Design and fabrication of mesoporous heterogeneous basic catalysts. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44, 5092–5147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, D.; Yan, X.; Liu, F.; Liu, M.; Zhang, H. Anthrathiophene-based covalent organic frameworks with powerful π-conjugation toward high-efficiency CO2 photoconversion. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2025, 17, 63467–63477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di, Z.; Wang, Y.; Chang, C.; Song, H.; Lu, X.; Cheng, F. Synergistic gas-slag scheme to mitigate CO2 emissions from the steel industry. Nat. Sustain. 2025, 8, 763–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Du, Q.; Mei, H.; Yu, J.; Kong, W.; Hu, J.; Ni, C.; Deng, N.; Huang, X. Controlled Fe2+ release and cycling in a dual-cathode induced electro-Fenton system for efficient organophosphorus degradation and phosphate recovery. Chem. Eng. J. 2026, 529, 172812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, C.L.; Cao, Y.D.; Feng, Y.; Fan, L.L.; Zhang, J.Y.; Song, Y.H.; Liu, H.; Gao, G.G. Crosslinked vinyl-capped polyoxometalates to construct a three-dimensional porous inorganic-organic catalyst to effectively suppress polysulfide shuttle in Li-S batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 2025, e05978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.; Wang, R.; Xie, Y.; Gao, F.; Tan, S.; Zhao, Z.; Yin, Q.; Hu, E.J. Interpretable machine learning analysis on CO2 adsorption and separation capacity of biochar under multi-scenario conditions. Green Energy Environ. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.T.; Li, X.W.; Shi, G.X.; Gao, Y.J.; Guan, Q.; Kang, G.D.; Zeng, Y.Z.; Xue, D.M. Generating Strongly Basic Sites on C/Fe3O4 Core–Shell Structure: Preparation of Magnetically Responsive Mesoporous Solid Strong Bases Catalysts. Catalysts 2025, 15, 743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, S.S.; Liu, S.; Shao, X.B.; Zhang, K.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Tan, P.; Yan, J.T.; Sun, L.B. Calcium single atoms stabilized by nitrogencoordination in metal–organic frameworks as efffcient solid base catalysts. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2025, 678, 88–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, G.; Wang, R.; Pang, J.; Wang, A.; Li, N.; Zhang, T. Production of renewable hydrocarbon biofuels with lignocellulose and its derivatives over heterogeneous catalysts. Chem. Rev. 2024, 124, 2889–2954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shao, X.B.; Song, X.R.; Peng, S.S.; Zheng, X.Q.; Qi, S.C.; Tan, P.; Liu, X.Q.; Sun, L.B. Low-temperature fabrication of potassium single-atom solid base catalysts with high activity in transesteriffcation. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 481, 148398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, X.B.; Liu, S.; Xing, Z.W.; Tang, J.X.; Li, P.; Liu, C.; Chi, R.Z.; Tan, P.; Sun, L.B. Atomically dispersed magnesium with unusual catalytic activity for transesteriffcation reaction. AIChE J. 2024, 70, e18567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Liu, B.; Wang, D. Microenvironment engineering of single/dual-atom catalysts for electrocatalytic application. Adv. Mater. 2023, 35, 2209654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiao, L.; Wan, G.; Zhang, R.; Zhou, H.; Yu, S.; Jiang, H. From metal–organic frameworks to single-atom Fe implanted N-dopedporous carbons: Efffcient oxygen reduction in both alkaline and acidic media. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018, 130, 8661–8665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Lin, K.S.K.; Chan, J.C.C.; Cheng, S. Preparation of ordered large pore SBA-15 silica functionalized with aminopropyl groups through one-pot synthesis. Chem. Commun. 2004, 23, 2762–2763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, X.B.; Nian, Y.; Peng, S.S.; Zhang, G.S.; Gu, M.X.; Han, Y.; Liu, X.Q.; Sun, L.B. Magnesium single-atom catalysts with superbasicity. Sci. China Chem. 2023, 66, 1737–1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, S.S.; Shao, X.B.; Gu, M.X.; Zhang, G.S.; Gu, C.; Nian, Y.; Jia, Y.; Han, Y.; Liu, X.Q.; Sun, L.B. Catalytically stable potassium single-atom solid superbases. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202215157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhao, Z.; Xu, C.; Liu, J. Structure, synthesis, and catalytic properties of nanosize cerium-zirconium-based solid solutions in environmental catalysis. Chin. J. Catal. 2019, 40, 1438–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suchikova, Y.; Nazarovets, S.; Konuhova, M.; Popov, A.I. Binary Oxide Ceramics (TiO2, ZnO, Al2O3, SiO2, CeO2, Fe2O3, and WO3) for Solar Cell Applications: A Comparative and Bibliometric Analysis. Ceramics 2025, 8, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, I.M.D.L.; Courel, M.; Moreno-Oliva, V.I.; Dueñas-Reyes, E.; Díaz-Cruz, E.B.; Ojeda-Martínez, M.; Pérez, L.M.; Laroze, D. The study of inorganic absorber layers in perovskite solar cells: The inffuence of CdTe and CIGS incorporation. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 10353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halfadji, A.; Bennabi, L.; Giannakis, S.; Marrani, A.G.; Bellucci, S. Sono-synthesis and characterization of next-generation antimicrobial ZnO/TiO2 and Fe3O4/TiO2 bi-nanocomposites, for antibacterial and antifungal applications. Ceram. Int. 2024, 50, 39097–39108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakhman, K.A.; Budhyantoro, A.; Aprilita, N.H.; Kartini, I. One-pot synthesis of hollow sphere TiO2/Ag nanoparticles cosensitized with peonidin: Pelargonidin for dye-sensitized solar cells applications. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2024, 35, 1926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsmadi, A.K.M.; Salameh, B.; Alshammari, O.; Bumajdad, A.; Madkour, M. Synthesis, photocatalytic, and photoelectric performance of mesoporous Au/TiO2 and Au/TiO2/MWCNT nanocomposites. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 2025, 207, 112874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina-Lozano, A.E.; Lanza, M.R.V.; Ortiz, P.; Cortés, M.T. Photoelectrochemical and Structural Insights of Electrodeposited CeO2 Photoanodes. Surfaces 2024, 7, 898–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldirham, S.H.; Helal, A.; Shkir, M.; Sayed, M.A.; Ali, A.M. Enhancement Study of the Photoactivity of TiO2 Photocatalysts during the Increase of the WO3 Ratio in the Presence of Ag Metal. Catalysts 2024, 14, 633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Q.; Ni, C.; Deng, N.; Huang, X. Efficient Adsorptive Removal of Phosphonate Antiscalant HEDP by Mg-Al LDH. Separations 2025, 12, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, C.; Zhang, Q.; Xu, B.; Deng, N.; Huang, X. The role of solid electrolytes in suppressing Joule heating effect for scalable H2O2 electrosynthesis. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 17958–17968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.; Wang, R.; Wang, X.; Tan, S.; Zhao, Z.; Yin, Q.; Lu, X. Preparation of lignin-based porous carbon through thermochemical activation and nitrogen doping for CO2 selective adsorption. Carbon 2024, 229, 119530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.M.; Asiri, A.M.; Uddin, M.T.; Islam, M.A.; Rahman, M.M. Wet-chemically prepared low-dimensional ZnO/Al2O3/Cr2O3 nanoparticles for xanthine sensor development using an electrochemical method. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 12562–12572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, T.T.; Shao, M.Q.; Gu, C.; Peng, S.S.; Liu, X.Q.; Sun, L.B. Low-temperature conversion of base precursor KNO3 on core–shell structured Fe3O4@C: Fabrication of magnetically responsive solid strong bases. Catal. Today 2021, 374, 200–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, S.S.; Wu, J.K.; Peng, A.Z.; Li, Y.X.; Gu, C.; Yue, M.B.; Liu, X.Q.; Sun, L.B. Fabrication of solid strong bases at decreased temperature by doping low-valence Cr3+ into supports. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2019, 584, 117153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, L.; Sun, L.B.; Sun, Y.H.; Li, T.T.; Liu, X.Q. Exploring in Situ Functionalization Strategy in a Hard TemplateProcess: Preparation of Sodium-Modified Mesoporous Tetragonal Zirconia with Superbasicity. J. Phys. Chem. C 2011, 115, 11633–11640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, S.S.; Lu, J.; Li, T.T.; Tan, P.; Gu, C.; Wu, Z.Y.; Liu, X.Q.; Sun, L.B. Significant decrease in activation temperature for the generation of strong basicity: A strategy of endowing supports with reducibility. Inorg. Chem. 2019, 58, 8003–8011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.Y.; Sun, L.B.; Lu, F. Low-temperature generation of strong basicity via an unprecedented guest–host redox interaction. Chem. Commun. 2013, 49, 8087–8089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, M.S.; Huang, H.C.; Ying, J.Y. Supramolecular-Templated Synthesis of Nanoporous Zirconia-Silica Catalysts. Chem. Mater. 2002, 14, 1961–1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kongwudthiti, S.; Praserthdam, P.; Tanakulrungsank, W.; Inoue, M. The influence of Si–O–Zr bonds on the crystal-growth inhibition of zirconia prepared by the glycothermal method. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2003, 136, 186–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carriazo, D.; Gutierrez, M.C.; Luisa, F.M. Resorcinol-based deep eutectic solvents as both carbonaceous precursors and templating agents in the synthesis of hierarchical porous carbon monoliths. Chem. Mater. 2010, 22, 6146–6152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Derchi, M.; Hensen, E.J.M. Promotional effect of transition metal doping on the basicity and activity of calcined hydrotalcite catalysts for glycerol carbonate synthesis. Appl. Catal. B 2014, 144, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, A.; Shen, W.; Eda, T.; Watanabe, R.; Ito, T.; Naito, S. NOx storage/reduction over alkali-metal-nitrate impregnated titanate nanobelt catalysts and investigation of alkali metal cation migration using xps. Catal. Today 2012, 184, 78–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, M.; Liu, Q.; Zhao, P.; Han, J.; Li, X.; Ha, Y.; Fu, Z.; Song, C.; Ji, N.; Liu, C.; et al. Promotional effect of SO2 on Cr2O3 catalysts for the marine NH3-SCR reaction. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 361, 830–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iida, H.; Kawaguchi, R.; Okumura, K. Production of Diethyl Carbonate from Ethylene Carbonate and Ethanol over Supported Fluoro-perovskite Catalysts. Catal. Commun. 2018, 108, 7–11. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, X.; Xu, W.; Liu, W.; Yue, M.B.; Zhu, Y.; Yang, M. Facile preparation of cuprous oxide decorated mesoporous carbon by onestep reductive decomposition for deep desulfurization. Fuel 2019, 241, 777–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Y.; Lei, Y.; Lan, G.; Liu, D.; Li, G.; Bai, R. Synthesis of glycerol carbonate from glycerol and dimethyl carbonate over DABCO embedded porous organic polymer as a bifunctional and robust catalyst. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2018, 562, 267–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Hao, P.F.; Li, S.X.; Zhang, A.L.; Guan, Y.Y.; Zhang, L.N. Synthesis of Glycerol Carbonate from Glycerol and Dimethyl Carbonate Catalyzed by Calcined Silicates. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2017, 542, 174–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Chen, F.; Yang, W.; Guo, J.; Xu, G.; Jia, F.; Shi, L. Excess soluble alkalis to prepare highly efffcient MgO with relative low surface oxygen content applied in DMC synthesis. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 20931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, X.B.; Xing, Z.W.; Liu, S.Y.; Miao, K.X.; Qi, S.C.; Peng, S.S.; Liu, X.Q.; Sun, L.B. Atomically Dispersed Calcium as Solid Strong Base Catalyst with High Activity and Stability. Green Energy Environ. 2024, 9, 1619–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, S.S.; Shao, X.B.; Gu, C.; Xing, Z.W.; Qi, S.C.; Han, Y.; Liu, X.Q.; Sun, L.B. Graphene-anchored sodium single atoms: A highly active and stable catalyst for transesteriffcation reaction. Nano Res. 2024, 17, 4979–4985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, S.S.; Zhang, G.S.; Shao, X.B.; Gu, C.; Liu, X.Q.; Sun, L.B. Generation of Strong Basicity in Metal–Organic Frameworks: How Do Coordination Solvents Matter? ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 8058–8065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakandritsos, A.; Kadam, R.G.; Kumar, P.; Zoppellaro, G.; Medved, M.; Tucek, J.; Montini, T.; Tomanec, O.; Andryskova, P.; Drahos, B.; et al. Mixed-Valence Single-Atom Catalyst Derived from Functionalized Graphene. Adv. Mater. 2019, 31, e1900323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.