Abstract

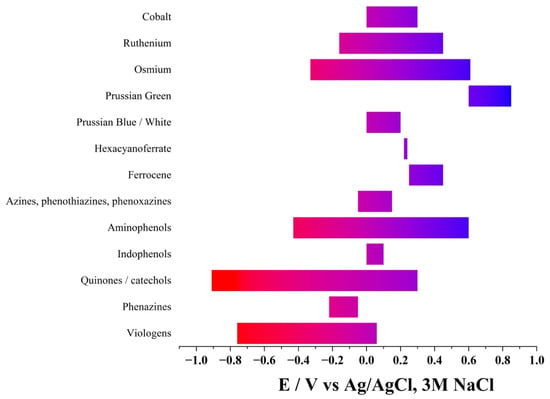

Redox mediators are central to electrochemical biosensors, enabling electron transfer between deeply buried enzymatic cofactors and electrode surfaces when direct electron transfer is kinetically inaccessible. Among all design parameters, the reversibility of mediator redox cycling remains the most decisive yet under-examined factor governing biosensor stability, drift and long-term reproducibility. This review establishes reversibility as a unifying framework grounded in inorganic and organometallic redox chemistry, with particular emphasis on coordination environments, ligand-field effects and outer-sphere electron-transfer pathways. Recent advances (2010–2025) in ruthenium and osmium polypyridyl complexes, cobalt macrocycles, hexacyanoferrates and Prussian Blue analogues are examined alongside ferrocene derivatives and other organometallic mediators, which together define the upper limits of reversible behaviour. Organic mediator families, including quinones, phenazines, indophenols, aminophenols and viologens, are discussed as mechanistic contrasts that highlight the structural and thermodynamic constraints that limit long-term cycling in aqueous media. Mechanistic indicators of reversibility, including peak separation, current ratios and heterogeneous electron-transfer rate constants, are linked to mediator architecture, coordination chemistry and immobilisation environment. By integrating molecular electrochemistry with applied sensor engineering, this review provides a mechanistically grounded basis for selecting or designing redox mediators that sustain efficient electron transfer, minimal fouling and calibration stability across diverse sensing platforms.

1. Introduction

Electrochemical biosensors convert biochemical recognition events into electrical signals, with electron transfer (ET) between a redox-active biocatalyst and an electrode forming the key transduction step [1]. For many oxidoreductases, the catalytic cofactors (e.g., flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD), heme or copper centres) are embedded within the protein matrix, hindering direct ET [2]. To overcome this kinetic barrier, redox mediators, such as small organic molecules, organometallic species, coordination complexes, polymers or nanostructured hybrids, are employed to shuttle electrons between the enzyme and the electrode surface [3,4].

A defining characteristic of an efficient mediator is its reversible redox behaviour [5]. In this review, ‘reversibility’ refers to the mediator’s ability to undergo repeated oxidation and reduction while maintaining both chemical integrity and electrochemical performance. Chemical recoverability of the redox states is therefore the central criterion, supported by electrochemical indicators such as peak separation (ΔEp), current ratios (ipa/ipc) and the heterogeneous electron-transfer rate constant (k°). High reversibility supports stable current output, reduced electrode fouling, predictable ET kinetics and reproducible analytical performance [4,6]. In contrast, irreversible or quasi-reversible mediators often induce potential drift and decreased activity, and require frequent recalibration [1].

Historically, mediator development has shaped biosensor evolution. First-generation sensors relied on molecular oxygen as the terminal electron acceptor but were constrained by poor solubility and the irreversibility of oxygen reduction [4]. Second-generation systems introduced synthetic mediators such as ferrocene (Fc), quinones and phenazines, enabling controlled outer- or inner-sphere ET and tuneable redox potentials [7,8,9]. While third-generation devices aim for mediator-free direct ET, practical biosensing continues to depend heavily on mediated approaches due to their engineered stability, potential control and reproducibility [3,6].

At the molecular level, reversibility is strongly influenced by the coordination environment, ligand field, spin state and electron-transfer mechanism, particularly for metal-based mediators such as Fc derivatives, ruthenium and osmium polypyridyl complexes, cobalt macrocycles and Prussian Blue (PB) analogues [7,8,9,10,11]. These systems often support robust, outer-sphere ET pathways that maintain chemical recoverability of both redox states and define the upper limits of reversible cycling in aqueous media. Their behaviour contrasts with that of many organic mediators, such as quinones and phenazines, in which proton-coupled ET (PCET), hydration, semiquinone formation and polymerisation frequently lead to loss of reversibility under operational conditions [7,8,9,12].

The scope of this review is to examine inorganic, organometallic and organic mediators through the lens of reversibility as a mechanistic design principle, with emphasis on literature published since 2010, when stability and mechanistic understanding became central criteria. Foundational earlier studies are included where they provide essential mechanistic context. Organic mediators considered here include quinones and catechols, phenazines, viologens, indophenols, aminophenols, azines, phenothiazines and phenoxazines. The inorganic and organometallic families surveyed encompass Fc derivatives, ruthenium and osmium polypyridyl complexes, iron and cobalt coordination compounds and PB analogues. Hybrid systems, including mediator-enzyme co-immobilised assemblies, are also discussed, as they inform the mechanistic analysis. Cyclic voltammetry (CV) is used throughout as the primary probe of electron-transfer kinetics and reversibility.

By centring the analysis on reversibility, this review establishes a unifying framework for comparing mediator classes and guiding the design of next-generation systems. The discussion links molecular structure, coordination chemistry and electron-transfer behaviour to measurable electrochemical performance, identifying how reversible mediators contribute to stability and reproducibility in biosensors.

Although numerous reviews have summarised the synthesis and use of specific mediator classes, such as quinones and Fc derivatives [9,12,13,14,15,16,17], these typically emphasise material development or analytical performance rather than the mechanistic determinants of electrochemical reversibility. In contrast, this review bridges inorganic, organic and physical electrochemistry with applied biosensor engineering. By correlating CV parameters with long-term stability, fouling tolerance and calibration drift, it provides a mechanistically grounded framework for selecting or engineering mediators suited to complex sample matrices.

Throughout this review, electrochemical potentials are reported versus Ag/AgCl, 3 M NaCl, wherever possible. When the original literature did not specify the chloride concentration of the Ag/AgCl reference electrode, or when pseudo-reference electrodes were employed, the potentials are reported as originally stated and clearly indicated in the corresponding table footnotes. No further conversion was applied in these cases to avoid introducing uncertainty or artificial offsets.

Accordingly, this review is not intended as a comprehensive catalogue of individual ligand families or coordination motifs, but rather as a cross-class analysis of reversibility as a functional design constraint in biosensing applications.

Defining Reversibility in Redox Mediators

In electrochemical terms, reversibility denotes a redox process in which the forward and reverse electron-transfer reactions are sufficiently fast that equilibrium between oxidised and reduced forms is maintained during potential cycling [18]. Operationally, this is assessed by CV, which examines the ΔEp and the ipa/ipc ratio. A mediator exhibiting ΔEp~59 mV × n−1 at 25 °C and ipa/ipc~1 is considered electrochemically reversible under diffusion control [18].

The Matsuda–Ayabe criteria provide a quantitative framework for distinguishing between electrochemically reversible, quasi-reversible, and irreversible systems. This dimensionless kinetic parameter Λ is defined in Equation (1),

where D is the diffusion coefficient (assuming Dox ≈ Dred), v the scan rate, n the number of electrons, R the gas constant, and T the temperature in Kelvin [19,20]. Systems with Λ > 15 are electrochemically reversible, with 15 > Λ > 10−3 are quasi-reversible, and with Λ < 10−3 are irreversible [21].

From the perspective of biosensor operation, reversibility must also encompass chemical sustainability, since mediators experience repeated cycling under non-ideal conditions. Practical reversibility, therefore, integrates two complementary aspects [18]:

- Electrochemical reversibility: rapid interfacial ET yielding near-Nernstian voltammetry, defined by small ΔEp and high k°.

- Chemical reversibility: structural and chemical integrity of the mediator during continuous redox cycling without decomposition, dimerisation, ligand loss, or adsorption.

Additionally, mediator performance is governed by [18,22] the following:

- (a)

- Physical retention: mediator leaching from the electrode or matrix should be minimal to maintain a consistent signal amplitude.

- (b)

- Biocompatibility: reversible mediators should not inactivate the enzyme or generate reactive intermediates that compromise electrode integrity.

- (c)

- Environmental robustness: redox reversibility should persist across realistic variations in pH, ionic strength, temperature and potential cycling frequency.

Quantitatively, Laviron and Marcus–Hush models are frequently applied to extract k° and transfer coefficients (α), which together provide a kinetic measure of reversibility [18,19,21]. Using Λ, fully reversible behaviour (Λ > 15) typically requires k°~0.05–0.17 cm s−1 for v = 0.01–0.10 V s−1 when D~10−5 cm2 s−1. Values around k°~1.0 × 10−2 cm s−1 correspond to quasi-reversible regimes at these scan rates (v). Complementary methods, such as electrochemical impedance spectroscopy and chronoamperometry, assess mediator stability and ET efficiency during extended operation [5]. Whereas organic mediators commonly rely on PCET, substituent-controlled frontier orbitals, and significant structural reorganisation, organometallic and coordination-based mediators derive their behaviour from rigid ligand fields and metal-centred redox manifolds that yield low reorganisation energies and highly predictable ET responses.

In this review, reversibility therefore denotes the combined electrochemical and chemical sustainability of the mediator. Framing the discussion around this dual definition enables mechanistic comparison between organic, inorganic and hybrid systems, clarifying how redox reversibility underpins the long-term reliability of an electrochemical biosensor. While both organic and inorganic mediators are widely employed, the uniquely tuneable and structurally rigid redox centres found in organometallic and coordination compounds underpin many of the most advanced biosensing architectures, motivating renewed interest in their systematic design.

2. Organometallic and Inorganic Mediators

Organometallic and inorganic mediators occupy a central position within the redox-mediator landscape because their electrochemical behaviour is governed by metal-ligand orbital interactions, ligand-field architecture, and predictable d-orbital manifolds, rather than by the proton-coupled or π-framework dynamics that dominate most organic dyes. Whereas reversibility in viologens, quinones, phenazines and phenoxazines is determined by substituent-driven modulation of frontier orbitals, proton-coupled equilibria and large reorganisation energies, metal-centred systems achieve near-ideal outer-sphere ET by imposing rigid coordination geometries that minimise structural distortion during redox cycling [18,23]. These features give rise to modular and tuneable redox couples across a broad mid-to-positive potential region, complementing the deeper negative potentials typically accessible to quinones and viologens and thereby expanding the electrochemical window available for biosensor design.

Their relevance becomes especially clear in applications where (i) precise potential matching to enzyme cofactors is required; (ii) reversible ET must be preserved under polymer or matrix confinement; (iii) operation must occur at potentials incompatible with the chemical stability of quinones or dyes; or (iv) oxygen interference must be circumvented.

Ferrocene derivatives, osmium polypyridyl complexes, ruthenium bipyridyl systems, cobalt macrocycles and related metal-ligand frameworks collectively address these demands. Their formal potentials, E°’, can be tuned over more than 1 V by modifying metal identity, ligand donor strength, axial coordination, or the surrounding microenvironment, enabling mediator design for FAD-, NAD-(nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide), PQQ-(pyrroloquinoline quinone), haem- and copper-dependent enzymes [23].

Mechanistically, most organometallic and inorganic mediators operate through outer-sphere ET, avoiding changes in coordination geometry, ligand protonation states or metal-ligand bond order during redox cycling. This sharply contrasts with organic proton-coupled electron-transfer systems, where protonation, tautomerisation or semiquinone formation frequently modulate voltammetric signatures. As a result, polypyridyl complexes and metallocenes typically exhibit low reorganisation energies, fast heterogeneous electron-transfer kinetics and stable Nernstian cycling even under repeated operation or challenging electrochemical conditions [18,23]. When incorporated into redox polymers or covalently tethered architectures, these complexes retain their electrochemical identity while supporting efficient electron hopping or through-bond transport, which is difficult to achieve with most small organic mediators.

Nevertheless, they are not universally superior. Their design space is constrained by aqueous stability, ligand-exchange susceptibility, toxicity considerations and synthetic cost, attributes that must be weighed carefully against their tunability and reversibility. Osmium redox polymers provide unmatched oxygen-independent wiring of oxidoreductases; Fc offers exceptional modularity; and cobalt complexes contribute ligand-controlled inner-sphere pathways and catalytic versatility within a mid-potential region where many organic mediators suffer from chemical instability. Consequently, organometallic and inorganic mediators play a structurally and mechanistically dominant role in expanding the accessible electrochemical design space, offering tunability and stability profiles that complement, and often exceed, those of purely organic mediator classes [23,24,25].

This conceptual framework motivates the following subsections, which examine Fc and osmium-, iron-, ruthenium-, and cobalt-based mediators, emphasising their mechanistic behaviour, potential tunability, immobilisation chemistry, and demonstrated biosensing performance.

2.1. Ferrocene

Ferrocene occupies a central position in organometallic mediator design because its Fe2+/Fe3+ oxidation is a prototypical outer-sphere electron-transfer process with exceptionally low reorganisation energy. The metal centre undergoes a clean, reversible one-electron transformation without bond-breaking, ligand rearrangement, or proton transfer, and its framework remains essentially invariant between redox states [26]. This absence of coupled chemical steps distinguishes Fc/ferrocenium (Fc+) from organic mediators that engage in PCET, tautomerisation or radical-radical processes (see below). In aqueous systems, water-compatible ferrocenyl derivatives (Figure 1) typically exhibit E°’ between 0.25 and 0.45 V vs. Ag/AgCl, 3 M NaCl, with the exact value governed by substituent electronics and the local microenvironment [27,28]. The rigidity of the η5-cyclopentadienyl coordination sphere and minimal geometric change upon oxidation account for Fc’s highly Nernstian behaviour and its long-standing role as a benchmark reversible mediator in both solution-phase and immobilised biosensing platforms [27,28].

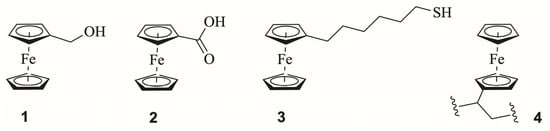

Figure 1.

Representative ferrocene mediators spanning solution-phase derivatives, including ferrocenemethanol (1) and ferrocenecarboxylic acid (2); the SAM-forming unit 6-ferrocenylhexanethiol (3) as a model surface-bound architecture; and poly(vinylferrocene) (4) as a prototypical polymer-confined redox system.

Across aqueous, buffered and polymer-confined environments relevant to biosensors, the Fc/Fc+ couple retains the hallmarks of a fully reversible outer-sphere redox process. In solution, Fc derivatives consistently exhibit Nernstian peak separations of ca. 59–60 mV for a reversible 1e− process [18], with k° typically in the 10−2–10−1 cm s−1 range at metal and carbon electrodes [29], placing Fc firmly in the reversible regime under diffusion-controlled conditions, while deviations observed in confined or viscous systems reflect transport and architectural limitations rather than intrinsic ET kinetics. Surface-confined Fc monolayers follow the Chidsey exponential distance-decay relationship, giving k°~102–103 s−1 for short alkyl chains [30], while Fc-based redox polymers display broadened yet symmetric voltammetry where the apparent ET rate is governed by polymer segmental mobility rather than intrinsic Fc kinetics [31,32,33]. Collectively, these quantitative metrics confirm that Fc exhibits intrinsically reversible outer-sphere ET across solution, SAM, and polymer environments, and that any quasi-reversible behaviour observed in biosensors reflects immobilisation geometry, polymer dynamics, or local microenvironmental constraints rather than limitations of the Fc/Fc+ couple itself.

Because neutral Fc is essentially insoluble in water, biosensor development has relied on derivatised Fc species bearing polar or ionisable groups (e.g., 1, 2, sulfonated or quaternary-ammonium Fc) or on Fc-functionalised polymers (Figure 1), in which pendant ferrocene units remain electrochemically addressable despite being immobilised within a hydrated polymer matrix. Substituent modification at the cyclopentadienyl rings allows redox potential, solubility, hydrophilicity and adsorption behaviour to be tuned, although the accessible range depends strongly on the medium. In aqueous electrolytes, water-compatible ferrocenyl derivatives typically vary within a comparatively narrow ca. 0.2 V window. In contrast, in mixed or non-aqueous solvents, the Fc/Fc+ couple can be shifted by several hundred millivolts without compromising reversibility [34]. These functionalisation sites enable Fc to serve as both a mediator and a local reporter, particularly in affinity sensors, where it is anchored to crown ethers, calixarenes or supramolecular hosts. Binding-induced dielectric, steric or π-interaction changes then modulate its voltammetric behaviour [34].

In immobilised architectures, Fc exhibits behaviours distinct from those of small organic mediators because ET becomes sensitive not only to the intrinsic ET rate constant but also to mediator accessibility, polymer dynamics and hydration state. Ferrocene-terminated SAMs on a gold support exhibit fast, reversible ET when the alkyl tether is short, as in 3, and when packing is dilute. In contrast, densely packed monolayers or deeply buried ferrocenyl units show markedly slower electron-transfer kinetics [34,35]. Similar constraints arise in chitosan, sol-gel and siloxane matrices: ET rates and apparent reversibility depend strongly on polymer segmental motion, water content and the spatial dispersion of ferrocenyl moieties [14,28]. These observations emphasise that Fc’s ideal outer-sphere behaviour is preserved only when the immobilisation geometry avoids insulating the metal centre and ensures efficient mediator-electrode communication.

Fc-based redox polymers, poly(vinylferrocene) (4), Fc-grafted polysiloxanes, ferrocenyl poly(ethyleneimine) and other Fc-functional networks extend these principles by enabling multistep electron-hopping pathways along polymer chains. Such architectures support mediator densities and apparent ET rates far exceeding those attainable with small molecules, effectively wiring oxidoreductases that are otherwise electronically insulated [27,28]. Polymer rigidity, hydration and the dielectric profile of the microenvironment govern hopping distance and stability, with well-optimised films displaying prolonged cycling, low drift and compatibility with physiological ionic strengths. These Fc-based redox polymers therefore bridge the gap between classical small-molecule mediators and the more strongly ligand-tuned osmium redox polymers, offering a complementary design space at intermediate potentials.

Ferrocene’s limitations arise from the same features that make it attractive. Classical Fc is hydrophobic and poorly soluble in water, necessitating derivatisation or incorporation into polymeric or hybrid matrices. Although Fc+ is generally stable under physiological conditions, it becomes vulnerable to nucleophilic attack in strongly alkaline media. For wiring high-potential oxidases, challenges typically stem not from the intrinsic Fc/Fc+ potential, which can be shifted through electron-withdrawing or electron-donating substituents and which spans positive, neutral and negative water-soluble derivatives, but from electrostatic and geometric factors: cationic Fc forms may be repelled by positively charged enzyme channels, and the purely outer-sphere nature of Fc can limit ET at buried or sterically gated active sites. Hydrophobic Fc units may also interact weakly with carbon surfaces, sharpening or distorting voltammetric profiles depending on surface preparation. These limitations are mitigated through Fc-modified chitosan, polysiloxanes, carbon nanotube (CNT)-polymer composites and water-soluble Fc redox polymers, which improve hydrophilicity, mediator dispersion and chemical robustness [14]. Despite these considerations, the combination of reversible outer-sphere ET, modular derivatisation, predictable potential tuning and compatibility with both solution-phase and immobilised architectures establishes Fc as a cornerstone organometallic mediator and a natural reference point for the more strongly ligand-tuned osmium, ruthenium and cobalt complexes discussed below.

2.2. Iron-Based Mediators: Ferricyanide, Ferrocyanide and Prussian Blue

The ferrocyanide/ferricyanide, [Fe(CN)6]4−/[Fe(CN)6]3−, couple (Equation (2)) remains one of the most widely used inorganic mediators in aqueous electrochemistry due to its textbook outer-sphere Fe2+/Fe3+ ET and well-defined redox thermodynamics. In a neutral buffer, the formal potential typically lies between 0.22 and 0.24 V vs. Ag/AgCl, and on polished glassy carbon electrodes, the couple exhibits the characteristic diffusion-controlled currents and well-defined peak shapes that underpin its historical role as a benchmarking redox probe [36,37]. In practical biosensor substrates, however, the behaviour becomes highly substrate-dependent. Screen-printed and composite carbon electrodes, which incorporate binders, surface oxides and microstructured domains, often display broadened voltammograms and altered kinetics due to restricted ion mobility, local adsorption and heterogeneous microenvironments [38,39]. On gold, the mechanistic picture changes fundamentally: [Fe(CN)6]3− rapidly chemisorbs, forming surface-bound Au-CN intermediates (commonly described as Au-CN-Fe linkages) that restructure the double layer and inhibit classical outer-sphere ET. At the same time, [Fe(CN)6]4− participates in further adlayer growth once the surface is modified [40,41]. These strong substrate effects create significant challenges when either [Fe(CN)6]4− or [Fe(CN)6]3− is used as a mediator, or when the couple is stored directly on metal electrodes in biosensing formats, where electrode pretreatment, microstructure and storage conditions strongly dictate electrochemical performance.

Across these substrates, the intrinsic reversibility of the [Fe(CN)6]4−/[Fe(CN)6]3− couple varies dramatically. On polished glassy carbon and other low-defect carbons, ΔEp values of 60–70 mV at low scan rates and ipa/ipc~1 and v1/2-dependent peak currents, together with diffusion coefficients near 10−6 cm2 s−1 and k° values in the 10−2–10−1 cm s−1 range, are all consistent with rapid, outer-sphere electron transfer [36,37]. Under these conditions, Matsuda–Ayabe analysis (Equation (1)) places the [Fe(CN)6]4−/[Fe(CN)6]3− couple in the reversible regime across typical biosensor scan rates, with only the lower end of the k° range approaching quasi-reversible behaviour at elevated scan rates where uncompensated resistance becomes significant. In contrast, screen-printed carbons typically exhibit ΔEp values broadened to 150–300 mV at 0.05–0.1 V s−1, diminished peak symmetry, and breakdown of v1/2 scaling, indicating quasi-reversible kinetics governed by surface chemistry and microstructured electrolyte domains [38]. On gold, chemisorption-driven inner-sphere behaviour progressively develops, ultimately suppressing classical reversibility and yielding slow, surface-confined electron-transfer signatures [40,41]. Although short exposures may transiently display near-Nernstian behaviour, the [Fe(CN)6]4−/[Fe(CN)6]3− couple rapidly loses outer-sphere character as adsorption proceeds. Thus, while intrinsically reversible at well-prepared carbon electrodes, its operational reversibility in biosensors is often severely compromised by substrate interactions, microstructure and adsorptive processes.

In solution-phase assays, [Fe(CN)6]3− can behave as a competent mediator for oxidases whose reduced cofactors lie well above 0.2 V, including glucose and lactate oxidases. Nevertheless, it is highly susceptible to parasitic chemistry: [Fe(CN)6]3− oxidises NADH non-selectively, competes with O2 for reduced flavins, and undergoes slow photodecomposition that releases free cyanide under illumination [36,37]. The [Fe(CN)6]4− product is also prone to reoxidation by dissolved oxygen, distorting calibrations in low-current biosensors. In alkaline media, hydroxide competes with cyanide for coordination, destabilising Fe-CN linkages and generating Fe(OH)x or soluble hexacyanoferrate fragments, a pathway well documented for the chemical degradation of Prussian Blue films [24,42]. These features sharply constrain its use in modern mediator-based biosensing, where stability, reversibility and compatibility with polymer matrices are essential. The behaviour contrasts strongly with Fc derivatives, whose outer-sphere ET and chemical inertness make them more predictable mediators over long operational times.

Where [Fe(CN)6]4−/[Fe(CN)6]3− represents a molecular outer-sphere probe, PB introduces a solid-state mixed-valence framework with fundamentally different constraints on reversibility.

Prussian Blue consists of an extended Fe3+-NC-Fe2+ mixed-valence lattice capable of reversible solid-state transitions between PB, Prussian White (PW) and Prussian Green (PG). Its electrodeposition proceeds through redox-driven assembly of intact hexacyanoferrate units rather than cyanide loss. Under anodic polarisation, ferrocyanide is first oxidised to ferricyanide at the electrode surface (Equation (2)), which establishes the oxidising conditions required for PB nucleation [24,43]. The ferricyanide produced in situ then coordinates Fe2+, generated chemically or electrochemically from Fe3+, to yield the canonical PB structural unit (Equation (3)),

where the cyanide ligands remain bound to Fe2+ and adopt μ-CN bridging geometry, binding Fe3+ through the nitrogen terminus to generate the extended PB lattice [24,43]. Charge-balancing cations are incorporated to form the hydrated solid (Equation (4)),

and when these elementary steps are combined, the overall electrodeposition from an Fe3+/Fe(CN)64− bath can be summarised by Equation (5) (formal net reaction):

provided the growth medium remains sufficiently acidic to prevent Fe3+ hydrolysis and cyanide displacement [43]. During operation, PB undergoes reversible reduction to PW (Equation (6)) and oxidation to PG (Equation (7)):

The E°’ for the PB/PW couple typically lies around 0.10 to 0.20 V vs. Ag/AgCl, enabling low-potential reduction of hydrogen peroxide through an EC′ process (electrochemical reduction of PB followed by catalytic chemical regeneration by H2O2) that gives PB its role as an “artificial peroxidase.” Operating at such low potentials suppresses electrochemical interferents, making PB valuable in oxidase-based sensors where H2O2 is the terminal reporter [42].

Prussian Blue films can exhibit near-ideal PB/PW reversibility only under tightly controlled structural and electrolyte conditions. Thin, well-crystallised PB films electrodeposited in acidic KCl display sharp PB/PW transitions with ΔEp as low as 15–30 mV at 0.01–0.02 V s−1 and symmetric peak currents whose scan-rate dependence lies between surface-confined (i ∝ v) and diffusion-controlled (i ∝ v1/2) behaviour, reflecting rapid mixed-valence conduction and efficient lattice utilisation [24,44]. Under such optimised conditions, apparent rate constants for PB/PW conversion and for the associated EC′ reduction of H2O2 can exceed 10−2 cm s−1, consistent with PB’s behaviour as an artificial peroxidase [43]. As PB films become thicker, less hydrated, or K+-deficient, ΔEp broadens to 80–150 mV, scan-rate dependence increases, and accessible charge decays due to finite ion mobility and formation of inactive domains, a pattern frequently reported for PB-nanotube and PB-oxide composites [38,45]. Prussian Blue is intrinsically pH-sensitive: above pH~7, the Fe2+/Fe3+-CN framework undergoes hydroxide-driven lattice dissolution, forming soluble ferricyanide species, while prolonged cycling promotes K+/H+ redistribution, Fe-vacancy accumulation and partial oxidation to PG [42,46]. Long-term storage, particularly in the dry state, often yields PB analogues with altered stoichiometry, shifted potentials, and diminished reversibility [24,44]. Prussian Blue films further exhibit variable adhesion to gold, carbon and metal-oxide substrates, and their mechanistic performance is strongly dependent on hydration state, thickness and K+ availability [41,43].

Taken together, ferricyanide, ferrocyanide and Prussian Blue represent the oldest and most widely used inorganic mediator systems. Yet, they lack the structural and electrochemical robustness of modern metallopolymer mediators such as Fc, Ru- and Os-polypyridyl complexes. Their behaviour deviates significantly from the ideal of chemically reversible, outer-sphere ET: [Fe(CN)6]4− suffers from adsorptive and ligand-exchange complications, pronounced interaction with gold surfaces and photolability, while Prussian Blue exhibits pH-limited stability, lattice dissolution and slow degradation under repeated cycling. Although both systems retain value in specific low-cost or legacy assay formats, their limitations place strict constraints on their deployment in contemporary biosensing architectures, and they are unsuitable for mediator-enzyme coupling strategies that rely on long-term redox cycling, immobilisation or polymer-based ET enhancement.

2.3. Osmium Complexes and Polymers

Osmium polypyridyl complexes (examples in Figure 2) constitute one of the most tuneable and electrochemically robust mediator families for aqueous biosensing. The Os2+/Os3+ couple is a clean outer-sphere process with negligible structural reorganisation. The resulting one-electron redox transition is fully reversible, showing no ligand exchange or proton-coupled rearrangement and retaining Nernstian behaviour in aqueous and polymeric environments [23,37]. The formal potential can be modulated over nearly 0.6 V by simple ligand-field variation, and the experimental values reported in aqueous buffer span from cathodic mixed-ligand complexes such as [OsCl(im)(dmbpy)2]2+ at −0.01 V vs. Ag/AgCl to strongly anodic tris-bipyridine species such as [Os(bpy)3]2+ at 0.61 V [47]. Parallel studies on substituted tris(4,4′-substituted bipyridine) complexes confirm that electron-donating 4-alkoxy and 4-dialkylamino substituents depress the redox potential of the complex, with potentials reaching −0.33 V for [Os(dmabpy)3]2+ [48]. In contrast, unsubstituted or π-accepting ligands push E°’ towards the positive potential limit [47,48]. These ligand-governed shifts directly correspond to the values summarised in Table 1, which consolidates aqueous potentials for both discrete complexes and polymer-bound Os species.

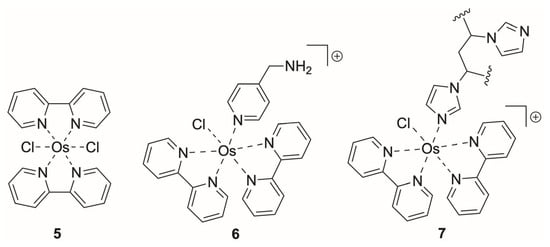

Figure 2.

Representative osmium redox mediators used in enzymatic biosensing: (5) parent bis(bipyridyl)Os(II) complex, forming the basis of most osmium polypyridyl mediator families, (6) tetherable Os(II) complex coordinated through the pyridine nitrogen, with a pendant amine for covalent attachment, (7) polymer repeat unit showing Os(II) coordination to the imidazole nitrogen of poly(Vim).

Table 1.

Formal potentials of representative osmium complexes and redox polymers in aqueous media.

Across both discrete complexes and polymer-bound hydrogels, the Os2+/Os3+ couple exhibits one of the most reliably reversible electrochemical behaviours among inorganic mediators. Tris-bipyridyl and mixed-ligand complexes typically display ΔEp values of 55–70 mV at 0.01–0.02 V s−1 with ipa/ipc~1, confirming fast outer-sphere ET and negligible structural reorganisation upon oxidation [47,53]. Analyses of [Os(bpy)2Cl(im)]+ and related species report heterogeneous rate constants k° in the 10−2–10−1 cm s−1 range, comparable to Fc but with superior ligand stability under cycling [48]. When incorporated into Poly(1-vinylimidazole), poly(Vim) or poly(vinylpyridine), poly(Vpy), hydrogels, the Os centres remain chemically reversible, but the voltammetry broadens due to finite electron-hopping transport: classic poly(Vim)-Os films show ΔEp~90–120 mV at 0.1 V s−1 and apparent diffusion coefficients D~10−8–10−6 cm2 s−1, the upper limit reached in highly hydrated, lightly crosslinked formulations [23,53]. More modern pendant-imidazole and amine-rich architectures further enhance mobility, yielding D values approaching 10−6 cm2 s−1 and narrower ΔEp profiles under matched hydration [54,55]. Importantly, Os3+ centres generated during cycling remain ligand-retentive and resist aquation or oxo formation under operational potentials, preserving chemical reversibility even during hours-long amperometry [37,56]. Deviations from ideal Nernstian behaviour therefore arise primarily from polymer microstructure, such as hydration, crosslinking density, counter-ion transport and local dielectric environment, rather than from instability of the Os2+/Os3+ redox couple itself.

Kinetic analyses demonstrate that these thermodynamic adjustments do not compromise the efficiency of mediation. Mixed-ligand complexes operating near 0.0 V, including [OsCl(im)(dmbpy)2]2+, sustain mediation rate constants on the order of 105 M−1 s−1, exceeding the performance of Fc carboxylates under comparable conditions [47]. Conversely, bipyridines bearing ionisable substituents (e.g., carboxylates or phenolates under alkaline conditions) can exhibit diminished electron-transfer rates due to increased ligand charge and altered interfacial interactions, despite favourable driving force [48], illustrating that long-range electrostatics can govern mediator-enzyme coupling as strongly as formal potential. Spectroelectrochemical studies across both discrete complexes and hydrogels further confirm that Os3+ centres do not undergo ligand loss or rearrangement during prolonged cycling, maintaining intact coordination spheres under operational bias [57,58].

For practical biosensing, osmium complexes are almost exclusively used as redox polymers, in which covalent tethering and electron hopping enable long-range wiring of buried redox cofactors. Poly(Vim) and poly(Vpy) architectures dominate this space due to strong N-donor anchoring and favourable hydration properties [25,59]. Early Type-II poly(Vim)-[Os(bpy)2Cl] hydrogels exhibit E°’ of ca. −0.25 V [2], whereas later pendant-imidazole formulations shift E°’ into the 0.20 to 0.33 V range, better matching oxidase operating windows [2]. Analogous trends extend across substituted bipyridine ligands: poly(Vim)-[Os(dmbpy)2Cl] and poly(Vim)-[Os(dmObpy)2Cl] shift the potential to −0.10 V and −0.07 V, respectively, while electron-rich diamino-bipyridine analogues reach −0.15 to −0.11 V, permitting ultra-low-bias operation of FAD-, PQQ- and haem-based oxidases [2]. At the positive limit, phenanthroline complexes such as poly(Vim)-[Os(im)2(phen)2]2+ reach 0.49 V and are suited for laccase cathodes and other high-potential systems [2].

In their crosslinked polymer form, these poly(Vim) and poly(Vpy)-bound osmium complexes behave as hydrated redox hydrogels, in which electron transport proceeds by site-to-site hopping with apparent diffusion coefficients in the 10−7–10−6 cm2 s−1 range, enabling efficient wiring of cofactors positioned tens of nanometres from the electrode surface [50,53]. Film mobility is strongly dependent on hydration and crosslinking; excessive rigidity electronically isolates osmium centres and diminishes current density despite favourable redox thermodynamics [25,59]. The polymer microenvironment also influences selectivity: oxidase electrodes employing Os-poly(Vim) exhibit suppressed oxygen interference because the mediator potentials are below the O2/OH− couple [60].

Stability considerations further distinguish osmium from other transition-metal mediators. Octahedral [Os(bpy)2Cl(L)]+ complexes, where the sixth ligand L is typically water, chloride or an imidazole donor in polymer-bound systems, exhibit exceptional resistance to ligand exchange. Chloride-containing species are notably resistant to photoaquation, in contrast to the chloride-labile Ru analogues that undergo photochemical drift in their redox potential [23]. Nevertheless, care is required during synthesis and storage, as inadvertent oxo formation can generate species such as poly(Vim)-[Os(bpy)2O2], which shifts the redox potential to 0.50 V and disrupts mediator-enzyme matching [50]. Advances in polymer design, particularly pendant amine and imidazole-rich frameworks, have improved immobilisation strength and reduced leaching [56,61], though crosslink over-densification remains a limiting factor for high-rate electron transport [59].

Collectively, these mechanistic, structural and electrochemical characteristics establish osmium polypyridyl complexes as among the most effective inorganic mediator classes for coupling enzymes to electrodes. Their broad, synthetically adjustable potential window, robust outer-sphere behaviour, resistance to ligand loss and compatibility with hopping-based redox polymers make Os2+/Os3+ systems the benchmark for low-overpotential enzymatic sensing across glucose, lactate, alcohol, choline and PQQ-dependent platforms [2,50,60]. However, these advantages come with substantial practical constraints. Osmium is considerably more expensive than iron-, cobalt- or ruthenium-based alternatives, and the high cost of Os precursors, combined with the need for covalent immobilisation and polymer crosslinking to prevent leaching, limits its suitability for high-volume disposable devices. Even modest Os loadings significantly affect total reagent cost, making widespread deployment in commercial strips or point-of-care cartridges economically challenging despite excellent analytical performance.

2.4. Ruthenium Complex Mediators

Ruthenium polypyridyl and amine complexes constitute an important mediator class whose geometry and outer-sphere kinetics resemble osmium systems, yet their Ru2+/Ru3+ couples more frequently fall at mid- to high-positive potentials in biologically relevant media. In aqueous buffer, the formal potential spans approximately from −0.16 to 0.45 V vs. Ag/AgCl, 3 M NaCl, governed by ligand-field strength, coordination environment and ionic medium [45,62,63,64,65,66]. Amine-rich complexes such as [Ru(NH3)6]3+ and several polymer-bound Ru centres lie at the lower end of this range (Table 2), whereas tris-bipyridine, phenanthroline and cyclometalated species, including [Ru(phpy)(bpy)2]+ and [Ru(topy)(bpy)2]+, appear near or above 0.20 V [62,63,65,67]. Electron-donating substituents depress the potential, as in [Ru(phpy)(dmbpy)2]+, while electron-withdrawing or strongly coordinating ligands such as carboxylates or sulfonates stabilise Ru3+ and shift E°’ positively [62,65,67]. These tuneable trends yield a potential window that overlaps extensively with osmium systems, though Ru mediators used in enzyme wiring typically occupy a somewhat narrower mid-positive region within this range.

Table 2.

Representative ruthenium mediator complexes assessed in aqueous or buffered media.

Across both discrete complexes and polymer-bound architectures, ruthenium mediators display a wider spectrum of reversibility than their osmium analogues. Classical outer-sphere complexes such as [Ru(NH3)6]3+ exhibit near-Nernstian behaviour on carbon, gold and oxide electrodes, with ΔEp = 55–70 mV at 0.01–0.02 V s−1, ipa/ipc~1, and heterogeneous rate constants k° in the 10−2–10−1 cm s−1 range, confirming rapid ET with minimal structural reorganisation [63,70,71]. In contrast, most Ru polypyridyl complexes show quasi-reversible Ru2+/Ru3+ electrochemistry, with ΔEp typically 80–120 mV and k° = 10−3–10−2 cm s−1, reflecting slower self-exchange kinetics relative to osmium analogues [64,72,73]. Upon immobilisation in redox polymers, including poly(Vpy), poly(Vim), sol–gel matrices and mixed-functional hydrogels, Ru centres remain chemically reversible. Yet, voltammetric profiles broaden due to finite electron hopping and ion-transport limitations, where the ΔEp values commonly reach 90–150 mV at 0.1 V s−1, with apparent diffusion coefficients D in the 10−8–10−6 cm2 s−1 range in hydrated films [62,66,69,71]. These deviations arise primarily from polymer microstructure, hydration and crosslink density rather than from instability of the Ru2+/Ru3+ centre, which generally retains its coordination sphere over operational potential windows.

The archetypal mediator [Ru(NH3)6]3+ avoids the surface sensitivity of the [Fe(CN)6]4−/[Fe(CN)6]3− couple and displays ideal diffusion-controlled behaviour, supporting a clean outer-sphere mechanism [62,64]. Its high charge drives strong localisation within polyanionic films such as DNA, heparin and carboxylated polymers, making it a widely used charge-reporting probe in nucleic acid sensors where total reductive charge reflects phosphate loading [62,64,66]. The same rapid Ru2+/Ru3+ cycling underpins electrografting and metallisation schemes in which Ru3+ oxidises surface-bound phenols or anilines, enabling the formation of conductive films under mild aqueous conditions [74,75].

Polypyridyl ruthenium complexes broaden mediator functionality through structural tunability and intrinsic photophysics. [Ru(bpy)3]2+, [Ru(dmbpy)3]2+ and [RuCl2(phen)2] typically show formal potentials of 0.35 to 0.45 V versus Ag/AgCl and undergo reversible Ru2+/Ru3+ oxidation with modest structural rearrangement [63,65,67,69]. Their stability enables incorporation into redox polymers and hydrogels that support electron-hopping pathways, though lower self-exchange rates reduce hopping efficiency relative to osmium systems [45,69]. Carboxylated bipyridines and iminodiacetate ligands enable covalent polymer attachment, improving immobilisation robustness and expanding compatibility with oxidoreductases such as glucose dehydrogenase (GDH), alcohol dehydrogenase and PQQ-dependent dehydrogenases [65,67]. However, because most ruthenium mediators occupy a narrower and slightly more anodic portion of the potential window than osmium analogues, they cannot access the lowest-bias regimes achievable with Os systems. This restricts their suitability for wiring low-potential cofactors such as FADH2 or reduced haem and increases susceptibility to oxygen reduction and oxidation of endogenous interferents [66,69,73].

Ruthenium complexes also form the basis of major photoelectrochemical and electrochemiluminescent platforms. Tris(bipyridyl) and tris(phenanthroline) derivatives show strong metal-to-ligand charge transfer absorption and long-lived excited states, enabling excitation-driven redox cycling and light emission central to immunoassays, DNA assays and multiplexed biosensing [62,63,76]. Their photodynamics are highly sensitive to polymer hydration, ionic strength and ligand substitution, which jointly tune both excited-state behaviour and the Ru2+/Ru3+ potential [63,73,76].

Despite their strengths, ruthenium mediators present several constraints relative to osmium and organic systems. Their positive operating potentials increase oxygen-reduction currents and amplify susceptibility to parasitic oxidation in complex samples [66,69,73]. Many Ru2+ polypyridyl complexes undergo photoaquation or ligand loss under illumination or extended bias, leading to drift in formal potential and diminished mediator loading [45,63,69]. Additionally, ruthenium compounds are costly, and access to polypyridyl derivatives often requires multistep ligand exchange and chromatographic purification, limiting suitability for high-volume disposable sensors [62,63,67]. Although less toxic than osmium analogues, ruthenium species still require strict confinement and minimal leaching in biomedical contexts [45,63]. Collectively, these factors position ruthenium complexes as potent yet specialised mediators, best deployed when their unique outer-sphere kinetics or photochemical properties deliver advantages not achievable with lower-cost mediator classes.

2.5. Cobalt Complex Mediators

Cobalt complexes occupy an intermediate position between classical outer-sphere mediators such as osmium and ruthenium polypyridyls and purely catalytic nanomaterials. Their Co2+/Co3+ couples are predominantly inner-sphere in character, often involving axial ligand coordination or substrate binding, and the degree of reversibility depends strongly on ligand structure, pH and immobilisation strategy. In aqueous media, cobalt phthalocyanine (8) and porphyrin (9) centres (Figure 3) typically display Co2+/Co3+ formal potentials between approximately 0.0 and 0.30 V vs. Ag/AgCl, with electron-donating ring substituents shifting the potential in the negative direction and electron-withdrawing or carboxylated groups shifting the potential positively [77,78,79,80,81]. This situates cobalt complexes within the mid- to high-potential region characteristic of aminophenols and indophenols, but at substantially more positive potentials than those of viologens, phenazines or low-potential quinones.

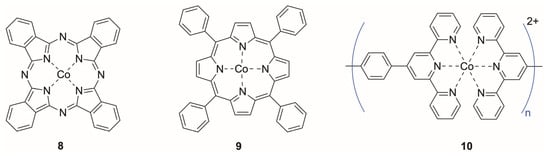

Figure 3.

Representative cobalt-based redox mediators used in electrochemical biosensing. (8) Cobalt(II) phthalocyanine, (9) cobalt(II) tetraphenylporphyrin and (10) a generic repeat unit of a cobalt coordination polymer, where the brackets indicate the polymer repeat unit and n denotes the degree of polymerisation.

Across both cobalt macrocycles and coordination-polymer systems, the Co2+/Co3+ couple rarely approaches the near-Nernstian behaviour observed for classical outer-sphere mediators [77,78,79,80,82,83]. Surface-confined cobalt phthalocyanines and porphyrins generally display broad, scan-rate-dependent waves with ΔEp values well above 100 mV at 0.02–0.1 V s−1 and ipa/ipc ratios that deviate from unity as catalytic H2O2 turnover overlaps the redox response [77,78,79,80,82,83]. Covalent pentamers, cobalt–porphyrin monolayers on gold, and carbon-supported phthalocyanines all exhibit a quasi-reversible Co2+/Co3+ wave overlaid by EC′ catalysis, with peak separation dictated as much by inner-sphere substrate binding and film structure as by the underlying electron-transfer rate [77,78,79,80,82,83,84]. Reported k° for the isolated Co2+/Co3+ step falls within 10−3–10−2 cm s−1 and often decreases upon repeated cycling due to partial demetalation, axial-ligand exchange or macrocycle oxidation [80,82,83,84]. In supramolecular cobalt coordination polymers, the formal Co2+/Co3+ couple remains visible but is superimposed on pronounced catalytic currents, and apparent diffusion coefficients extracted from hopping models are one to two orders of magnitude lower than those of classical outer-sphere mediators [15,81,85,86,87]. Overall, cobalt centres in biosensing films operate as quasi-reversible systems whose voltammetric profiles are dominated by inner-sphere chemistry, film microstructure and catalytic EC′ pathways; the Co2+/Co3+ couple can therefore support efficient peroxide-based signalling but is poorly suited as a benchmark reversible mediator [15,81,85,86,87].

Cobalt phthalocyanines and tetraphenylporphyrins remain the most widely studied cobalt mediators and function as surface-bound inner-sphere redox centres that mediate H2O2 or substrate oxidation via an EC′ mechanism [78,79]. A covalently linked pentamer, 8–(9)4, immobilised on glassy carbon, exhibits a well-defined Co2+/Co3+ couple in neutral and alkaline media and catalyses H2O2 reduction with low micromolar detection limits and fast chronoamperometric responses without dissolved mediator [79]. The same pentamer mediates glucose oxidation efficiently by accepting electrons from glucose oxidase (GOx)-generated H2O2 at substantially lower potentials than bare carbon [78]. Self-assembled tetracarboxylic cobalt phthalocyanine monolayers also display a stable quasi-reversible Co2+/Co3+ wave and robust H2O2 electrocatalysis. However, performance depends strongly on monolayer order, the axial-ligand environment, and the accessibility of the Co centre [77]. Fluorinated or polymeric cobalt phthalocyanines on carbon supports exhibit similar behaviour, with enhanced dispersion and tuned potentials, but remain dominated by inner-sphere peroxide reduction rather than pure outer-sphere mediation [80,81].

Beyond discrete macrocycles, cobalt-based supramolecular coordination polymers serve as both immobilisation scaffolds and redox-active mediator networks. The Co2+ coordination polymer 10 is a representative example: it co-immobilises GOx on glassy carbon in a single casting step, displays a quasi-reversible Co2+/Co3+ couple under neutral aqueous conditions and participates directly in an EC′ catalytic cycle where GOx-generated H2O2 oxidises Co2+ to Co3+, and the electrode subsequently reduces the film [82]. Although CV and spectroscopy show that structural changes during cycling are modest and the response remains stable, the mechanism remains non-Nernstian and dominated by catalytic peroxide turnover [82]. Mixed-ligand cobalt complexes embedded in conducting polymers or CNT composites have similarly been used to mediate ET in glucose and H2O2-based sensors, but in nearly all cases, the mechanism reflects a combination of inner-sphere mediation and electrocatalysis rather than clean outer-sphere shuttling [83,85].

Cobalt-based mediators present several constraints relative to osmium, ruthenium and low-potential organic systems. Their Co2+/Co3+ potentials (0.0 to 0.30 V vs. Ag/AgCl) do not promote oxygen reduction but overlap the anodic onset of endogenous interferents such as ascorbate, urate and phenolic metabolites, with catalytic EC′ turnover further shifting operating bias positive and increasing susceptibility to non-specific oxidation [78,82]. Cobalt macrocycles may undergo gradual demetalation, ligand oxidation or axial substitution during repeated cycling, leading to drift in peak position and diminished mediator capacity [80,86]. Polymer-supported cobalt systems improve retention but still experience partial loss of electroactivity due to film rearrangement or ion-transport limitations in hydrated matrices [82]. Finally, multistep synthesis and purification requirements for cobalt macrocycles render high-loading disposable sensors less economical than Fc- or quinone-based platforms [15,77]. These factors position cobalt mediators as valuable but specialised redox systems, best employed when their coordination chemistry or surface-binding properties confer functional advantages that lower-potential or more reversible mediator classes cannot.

3. Organic Mediators: Limits and Mechanistic Contrast

Organic mediators occupy a chemically diverse and electrochemically expansive domain, ranging from the deeply reducing viologens to the more oxidising aminophenol and indophenol derivatives. Although these systems offer tuneable potentials and, in some cases, fast electron-transfer kinetics, their apparent reversibility is governed as much by chemical stability as by intrinsic redox behaviour. Unlike organometallic and inorganic mediators, whose cycling is stabilised by rigid ligand fields and predictable outer-sphere mechanisms, most organic redox couples are embedded within proton-coupled electron-transfer manifolds, hydration equilibria, tautomerisation pathways and structural rearrangements that compete directly with electrode-driven cycling [2,88].

As a result, even when CVs appear Nernstian over limited timescales, the oxidised or reduced forms of many organic mediators undergo side reactions, such as hydration, semiquinone formation, Michael-type addition, radical dimerisation or polymerisation, that progressively erode true reversibility in aqueous media. These chemical constraints define the limits within which organic mediators can operate reliably and highlight the mechanistic contrasts that motivate the transition to metal-centred systems in long-term biosensing applications [18,89,90].

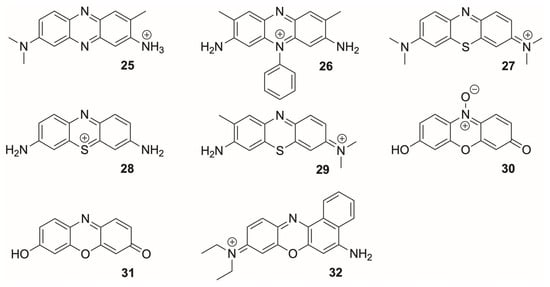

The following subsections examine prominent organic mediator families, including viologens, phenazines, quinones, catechols, indophenols, aminophenols, azines, phenothiazines and phenoxazines, emphasising the structural, proton-coupled and microenvironmental factors that govern their stability and effective reversibility under operational conditions.

3.1. Viologens

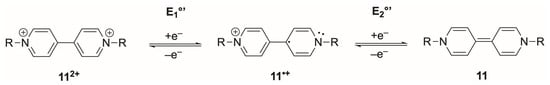

Viologens, the 4,4′-bipyridinium family of redox-active molecules, represent one of the most extensively characterised classes of organic mediators in electrochemistry. Their widespread use in early and contemporary biosensors stems from the intrinsic reversibility of the 112+/11•+ couple (Scheme 1), the ease with which their formal potentials can be tuned, and the compatibility of the bipyridinium scaffold with numerous immobilisation strategies [91]. The parent dication 112+ undergoes two sequential one-electron reductions, first to the persistent blue radical cation 11•+ and then to the neutral species 11, a stepwise two-ET pattern described in classical electroanalytical treatments [18,92]. These well-defined redox transitions have made viologens benchmark systems for validating electrode surfaces and for constructing controlled electron-transfer pathways in biosensors and redox polymers.

Scheme 1.

General mechanism for the two-step reduction of viologens, where R denotes the N-substituent, and E1°’ and E2°’ are the formal potentials for the first (112+/11•+) and second (11•+/11) one-electron couples.

Although viologens can store two electrons, the two redox steps are not concerted and typically differ by several hundred millivolts. For example, in acetonitrile containing 0.1 M [Bu4N][PF6] as the supporting electrolyte, methyl viologen displays E1°’ = −0.76 V and E2°’ = −1.18 V vs. Ag/Ag+, giving a separation of ca. 0.42 V [93,94]. In aqueous media, substituted viologens likewise show well-separated couples. In 1 M Na2SO4, the E1°’ typically appears around −0.61 V vs. Ag/AgCl, 3 M NaCl and E2°’ near 0.3 V more negative than E1°’, which varies only modestly with N-substitution [95]. In biosensing, only the first, well-behaved 112+/11•+ transition is exploited: it lies within the potential range of biological cofactors and avoids generating the neutral species 11, which is strongly adsorbing and chemically unstable under aerobic conditions [95]. Thus, viologens operate functionally as one-electron mediators despite their formal two-electron capacity.

Under inert conditions and at moderate scan rates, the 112+/11•+ couple of soluble viologens typically exhibits ΔEp values very close to the Nernstian 59 mV limit for a one-electron process, with ipa/ipc~1, reflecting fast heterogeneous ET and classical electrochemical reversibility on glassy carbon, gold, and carbon-based surfaces [96,97]. These features are consistently observed in both aqueous and non-aqueous media, and the behaviour remains near-Nernstian across 0.01–0.10 V s−1.

Quantitative analysis using Nicholson, Matsuda–Ayabe or Laviron formalisms typically yields k° in the range 10−3–10−1 cm s−1, depending on substitution, counter-ion and electrode surface [98,99]. For k° ≥ (3–5) × 10−2 cm s−1, the first 112+/11•+ reduction behaves electrochemically reversible (Λ ≥ 15 at v of ca. 0.05–0.10 V s−1), whereas systems with k° closer to 10−3–10−2 cm s−1 fall into the quasi-reversible regime. This spread is consistent with canonical descriptions of viologen electrochemistry, where many derivatives exhibit near-Nernstian behaviour under typical biosensor conditions.

Departures from ideal reversibility arise from well-documented chemical side processes, particularly radical–radical dimerisation, surface adsorption, and oxygen-mediated redox cycling. Radical dimerisation has measurable kinetics and leads to broadened or distorted waves with increased ΔEp and progressive cycling drift [96,97]. Adsorption of the reduced species at carbon surfaces likewise generates asymmetric peak shapes and quasi-reversible character over repeated scans [98]. In aerated solutions, rapid mediated oxygen reduction through the 112+/11•+ cycle perturbs voltammetry, increases apparent currents and accelerates chemical degradation of the mediator [100,101].

When viologens are immobilised in redox polymers or tethered films, the electrochemical response transitions to surface-confined waves with ΔEp remaining close to ~60 mV even at scan rates up to several hundred mV s−1, indicative of fast intrafilm electron hopping and efficient charge transport [102,103]. The shift from diffusion-limited to ion-transport-limited behaviour at higher scan rates highlights the role of ionic mobility within the matrix, which becomes the rate-determining step rather than ET itself.

In practice, therefore, viologen-based mediators are electrochemically reversible on the timescales and potential windows relevant to biosensing. Their practical long-term reversibility is governed not by intrinsic electron-transfer kinetics but by radical stability, oxygen sensitivity, adsorption phenomena and the physicochemical architecture of the host film (hydration, thickness, ion-mobility constraints) [99,103].

N-alkyl substitution produces only modest (tens of millivolts) shifts in E1°’, whereas aromatic ring substitution allows much larger and systematic tuning of viologen redox thermodynamics [104]. Electron-withdrawing cyano groups shift E1°’ to more positive values and stabilise 11•+, as demonstrated for mono- and dicyanoviologens [105]. In aqueous 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) with Ag/AgC, 3 M KCl reference, introduction of a single cyano group moves the first redox wave from ca. −0.65 to −0.34 V, and the dicyano derivative undergoes a further positive shift to E1°’ = 0.06 V [32]. These shifts provide a direct means of placing the 112+/11•+ couple well above typical flavin potentials.

In contrast, and as mentioned before, variation in the N-substituent around the viologen core enables fine-tuning within negative-potential regimes. An aqueous library encompassing non-polar, anionic and cationic substituents showed E1°’ = −0.54 to −0.67 V vs. Ag/AgCl, with benzyl viologen centred near −0.54 V [106]. Extended aromatic and long-chain alkyl groups promote π-π stacking and amphiphilic behaviour, favouring ordered packing and aggregate formation in solution and at interfaces, whereas strongly polar or sulfonated substituents enhance water solubility of both redox states and suppress radical-radical dimerisation [91,107,108,109]. These substituent effects collectively provide a molecular basis for tuning viologen potentials to match enzymatic cofactors while retaining reversible electrochemical behaviour.

Polymer-tethered viologens extend these design principles by fixing the mediator within a redox-active matrix. Pendant dicyanoviologen units embedded in a hydrophilic methacrylate-type backbone undergo rapid electron hopping, enabling efficient communication between FAD-GDH active sites and the electrode [105]. In neutral phosphate buffer, the free dicyanoviologen monomer displays E1°’ = 0.06 V, whereas the drop-cast polymer film shows a slightly less positive potential at ca. 0.05 V, with minimal pH dependence [20]. The polymer retains well-defined peaks during extended cycling and supports stable catalytic glucose oxidation, illustrating how cyano substitution combined with polymer confinement tunes E1°’, stabilises the radical cation and suppresses mediator loss.

Complementary work on amphiphilic and surface-anchored viologens shows how nanoscale organisation governs electron-transfer behaviour. Langmuir–Blodgett multilayers and self-assembled films formed from long-chain or sulfonated viologens impose structural order, with packing density, tilt angle and film thickness exerting strong control over reversibility and accessible electron-transfer distances [91,107,108,109]. In such supramolecular architectures, the 112+/11•+ couple typically resides within −0.4 to −0.6 V vs. Ag/AgCl, but kinetic parameters vary markedly with film organisation.

The redox potential of the 112+/11•+ couple is well-suited to ET from reduced flavins, enabling efficient coupling with FAD-dependent oxidases and dehydrogenases. Methyl viologen readily accepts electrons from FADH2 in GOx systems, underpinning its historical use in first-generation glucose sensors [91,107]. Dicyanoviologen polymers couple efficiently with FAD-GDH, allowing the oxidation of FADH2 at potentials substantially lower than those for oxygen reduction [105]. Benzyl viologen’s potential near −0.54 V matches the unusually low redox potential of F420, enabling reversible cofactor cycling with minimal overpotential [105]. These examples underscore that viologen functionality is determined by the mediator’s tuneable potential landscape rather than by the enzyme itself.

Despite their excellent electrochemical reversibility, viologens exhibit several chemical limitations relevant to biosensor design. The radical cation 11•+ can undergo disproportionation or dimerisation at high surface coverage or in poorly hydrated films, perturbing voltammetry at slow scan rates [18]. The fully reduced species 11 strongly adsorbs onto carbon electrodes, leading to quasi-reversible behaviour and hysteresis. The 11•+ intermediate reacts rapidly with dissolved O2 to form superoxide, regenerating 112+, as evidenced in methyl viologen/Nafion films where O2 reduction dominates the background current [107]. Light exposure can induce photoreduction, particularly in viologen films containing chromophoric groups or photoactive co-components [108]. These pathways illustrate that viologens are electrochemically reversible but chemically fragile under certain conditions, underscoring the importance of immobilisation, film hydration, and control of O2 or light exposure.

Toxicity represents an additional constraint. Methyl viologen is the herbicide paraquat, whose well-documented toxicity stems from efficient redox cycling with molecular oxygen to generate reactive oxygen species [110]. Although viologens in general share the capacity to form persistent radical cations, the extent of biologically relevant redox cycling varies with substitution pattern, hydrophobicity and membrane permeability. Free viologens can therefore exhibit reactive oxygen species-associated cytotoxicity when sufficiently bioavailable, whereas immobilisation within polymers, hydrogels or Nafion restricts diffusion and cellular uptake, substantially mitigating these risks. Consequently, toxicity considerations remain essential for in vivo or environmental applications, motivating the use of immobilised mediators over freely diffusing ones.

Together, these insights establish clear design principles for constructing viologen-based mediators with high practical reversibility. Substituent chemistry should be selected to stabilise the 11•+ state, minimise pathways that compromise chemical reversibility (dimerisation, disproportionation, O2 reactivity) and position the 112+/11•+ couple within a useful biological potential window. Polymer-tethered architectures and immobilised matrices should be prioritised, as confinement suppresses mediator loss, moderates radical side reactions, and preserves near-Nernstian behaviour over repeated cycling. Control of film hydration, counter-ion mobility and nanoscale organisation is essential, since these parameters dictate whether the system remains in the reversible regime or drifts towards quasi-reversible behaviour. Collectively, these strategies translate the intrinsic electrochemical reversibility of viologens into robust, long-lived mediator performance suitable for biosensing applications.

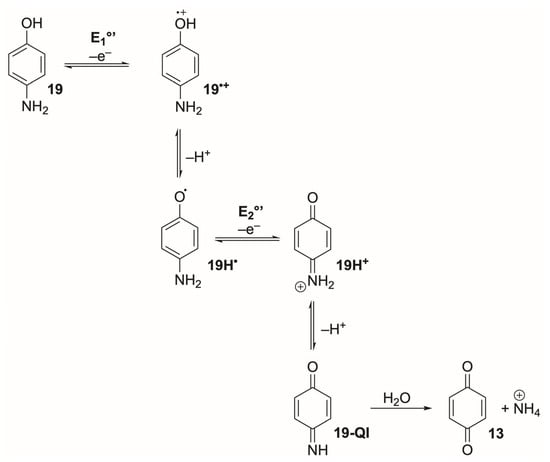

3.2. Phenazines

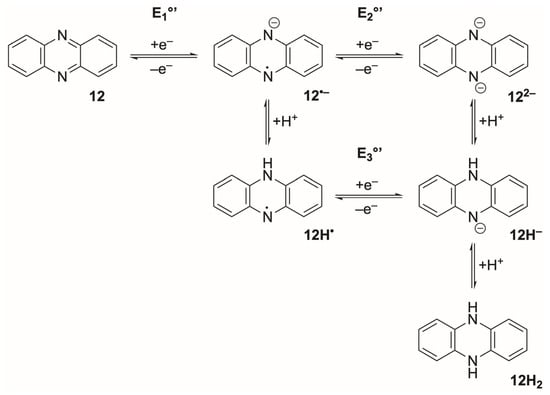

Phenazines form a second major family of low-potential organic mediators whose electrochemical behaviour depends strongly on substitution at the ring nitrogens. The parent phenazine (12) undergoes a proton-coupled ECEC mechanism (a four-step redox process consisting of alternating electrochemical (E) and chemical (C) steps) in aqueous media (Scheme 2) [111,112]: the first ET produces a radical anion (12•−) that is rapidly protonated, followed by a second ET and protonation to yield the dihydrophenazine (12H2). This pathway generates two pH-dependent, often broadened one-electron waves and commonly exhibits adsorption and non-Nernstian behaviour, particularly on carbon electrodes [113,114]. In contrast, N,N′-substituted phenazines such as phenazine methosulfate (PMS) and phenazine ethosulfate (PES) cannot undergo protonation at the ring nitrogens and instead display a clean, pH-insensitive two-electron reduction. Although these derivatives appear to undergo a single 2e− process, the underlying mechanism is not a concerted EE step. Rather, blocking protonation collapses the usual ECEC sequence of the parent phenazine into two sequential electron-transfer steps (E1°’ and E2°’) whose formal potentials differ by only a few millivolts; as a result, the two 1e− waves merge into a single voltammetric feature that behaves as a reversible 2e− couple. In aqueous buffer, these derivatives typically show a single, well-defined 2e− wave centred at −0.05 to −0.10 V vs. Ag/AgCl, with fast heterogeneous ET and minimal peak separation [115,116]. Substitution at the N-positions also suppresses formation of protonated semiquinone-type intermediates and improves chemical stability relative to the free phenazine scaffold, whose reduced forms readily undergo follow-up chemistry and surface adsorption [117,118]. These mechanistic distinctions align with general treatments of proton-coupled ET and mediator-based electrochemical catalysis, in which blocking protonation pathways collapses multi-step ECEC sequences into reversible electron-transfer waves [90,119].

Scheme 2.

Stepwise reduction of phenazine (12). Electron-transfer steps proceed horizontally, while protonation steps occur vertically.

Under conditions relevant to biosensing, N-substituted phenazines such PMS and PES typically display high quasi-reversible to reversible behaviour on voltammetric timescales. Cyclic voltammograms of PMS and PES in buffered aqueous media show single, well-defined redox waves with small peak separations and formal potentials near −0.22 V and −0.19 V vs. Ag/AgCl, 3 M NaCl, respectively, at pH 8–8.5 [120]. The analysis of the 12/12H2 couple indicates that ET at the electrode can be intrinsically fast, with apparent surface rate constants of 106–107 s−1 for adsorbed species [89]. Solution-phase studies in aprotic media similarly report k° in the 10−2–10−1 cm s−1 range [121], placing the first reduction step in the Matsuda–Ayabe high quasi-reversible to reversible regime under typical CV scan rate (0.05–0.10 V s−1). Deviations from ideal Nernstian behaviour in aqueous solution arise mainly from proton-coupled follow-up chemistry, modest adsorption of reduced species and the chemical reactivity of the 12H2 form, which increases ΔEp and introduces minor scan-rate dependence [89,122,123]. Phenazine methosulfate additionally undergoes oxygen-driven autoxidation and light-induced decomposition, forming secondary phenazine products that contribute to current drift, whereas PES is comparatively more photochemically stable [120,124,125]. In immobilised formats, such as PES-based redox hydrogels, covalently tethered phenazine derivatives or phenazine-bearing redox polymers, the redox response becomes surface-confined, with narrow peak separations even at elevated scan rates, reflecting fast segmental electron hopping and the suppression of mediator-loss pathways [113,126,127]. Overall, phenazines exhibit electron-transfer reversibility that is primarily limited by chemical instability rather than by slow electrode kinetics, making them effective short-timescale mediators when photodegradation and oxygen exposure are controlled.

Substitution both at the phenazine core and on the sulfonate/sulfate side chains allows further tuning of solubility, aggregation and the formal potential. Phenazine methosulfate and PES, which are the most widely used mediators in biosensing, are cationic salts with high aqueous solubility. In contrast, more hydrophobic or extended-aromatic phenazine derivatives can be incorporated into polymer matrices or sol-gel films. Electropolymerised PMS films and phenazine-containing redox polymers demonstrate that phenazine units can be immobilised while retaining quasi-reversible ET; the polymer environments facilitate rapid electron hopping and minimise mediator loss during cycling [114,117]. In inorganic composite electrodes such as TiO2-based systems, thin PMS layers act as surface-confined mediators that efficiently relay electrons between the electrode and dissolved H2O2 or enzymatically generated intermediates, yielding well-defined surface waves and stable amperometric signals [115,118]. Recent PMS- and PES-modified carbon electrodes and polymer composites show that immobilisation stabilises the two-electron wave, reduces photodegradation and improves long-term operational stability under continuous turnover [113].

Functionally, phenazines have been applied most broadly to dehydrogenase- and oxidase-based biosensors operating at low potentials. Phenazine methosulfate and PES are established mediators for NAD+-dependent dehydrogenases, shuttling electrons from enzymatically produced NADH to the electrode. This strategy has been used in sensors for lactate, glutamate, ethanol, malate and glucose, where the relatively positive potential of PMS enables efficient NADH oxidation without requiring large overpotentials that would increase interference from endogenous reductants [114,116]. Phenazine-modified electrodes have also been used to wire FAD-dependent and PQQ-dependent enzymes, as well as to couple peroxidase-type reactions to H2O2 detection at low potentials, improving selectivity in oxidase-based biosensors [113,115]. More recent computationally guided work has produced substituted phenazine analogues designed to stabilise the radical intermediate and shift the 2e− wave into a more biologically compatible potential window, enabling extended linear ranges and improved interference tolerance in whole-blood glucose sensing [8]. These developments reflect broader principles of mediator design in electroenzymatic systems, where matching mediator potential to cofactor thermodynamics and ensuring rapid interfacial exchange are essential for achieving efficient catalytic currents [119].

Phenazines also present several limitations relevant to biosensor design. Reduced PMS and PES autoxidise readily in the presence of dissolved oxygen, forming superoxide and regenerating the oxidised mediator; while this redox cycling can enhance apparent catalytic efficiency, it also elevates background currents and produces reactive oxygen species that may degrade enzymes or biological analytes during prolonged operation [114,118]. Under strongly reducing conditions, reduced phenazines may dimerise or irreversibly adsorb onto carbon electrodes, gradually diminishing reversibility and contributing to electrode fouling [117]. Photosensitivity is another concern: several substituted phenazines bleach or degrade under illumination, particularly in transparent-electrode or optical-sensor formats [113]. Finally, like viologens, phenazines exhibit intrinsic toxicity through redox cycling and reactive oxygen species generation; this necessitates immobilised, polymer-confined or membrane-separated architectures for biological or environmental applications that involve sustained exposure.

Taken together, phenazines complement viologens as tuneable low-potential mediators. Their proton-coupled redox chemistry, the clean two-electron behaviour of N-substituted derivatives, and their strong compatibility with NAD-dependent dehydrogenases make them particularly valuable for low-potential bioelectrocatalytic systems. Polymer-tethered, immobilised, and composite-film implementations mitigate issues of autoxidation, fouling and toxicity, enabling phenazines to operate effectively in continuous-monitoring sensors and biofuel cells.

3.3. Quinones and Catechols

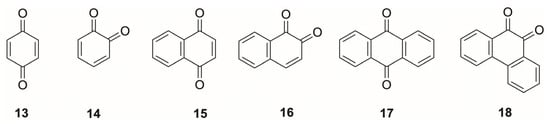

Quinones (13 and 14, Figure 4) and their reduced catechol/hydroquinone counterparts span a broad low-to-mid-potential window, reflecting strong substituent-dependent modulation of redox thermodynamics. In neutral buffered aqueous media, typical 2e−/2H+ formal potentials for the benzoquinone/hydroquinone couple fall roughly between −0.30 and 0.3 V vs. Ag/AgCl, 3 M NaCl, depending on ring size, substitution, and pH [128,129]. Simple 1,4-benzoquinone and 2,3,5,6-tetramethyl-1,4-benzoquinone cluster near −0.21 to −0.16 V vs. Ag/AgCl, 3 M NaCl at pH 7 [76,128], while mono- and dihydroxynaphthoquinones (Figure 4) lie slightly more positive, between −0.08 and −0.06 V vs. Ag/AgCl, 3 M NaCl [128]. More extended π-systems such as anthraquinone-1,5-disulfonate exhibit considerably lower potentials of ca. −0.91 V vs. Ag/AgCl, 3 M NaCl [128], and anthraquinone-2-sulfonate sits near −0.44 V vs. Ag/AgCl, 3 M NaCl in neutral media [130]. Thus, by progressing from benzo- to naphtho- to anthraquinones (Figure 4), one can systematically shift the working potential from slightly positive to moderately negative values while retaining the same basic quinone/hydroquinone redox motif.

Figure 4.

Representative parent structures of quinones showing progressive ring extension: (13) 1,4-benzoquinone, (14) 1,2-benzoquinone, (15) 1,4-naphthoquinone, (16) 1,2-naphthoquinone, (17) 9,10-anthraquinone, and (18) 9,10-phenanthraquinone.

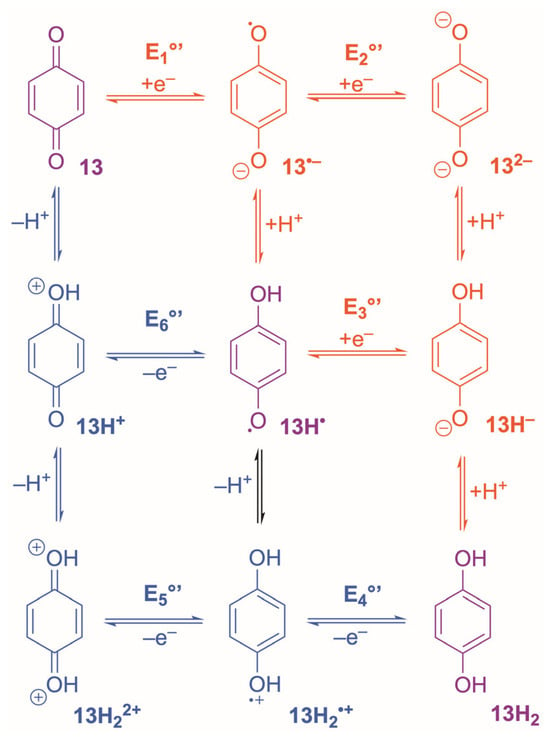

Electrochemically, quinones behave as classic PCET systems. In protic media, reduction of quinone to hydroquinone (Scheme 3) usually proceeds through two sequential 1e−/1H+ steps, often appearing as an apparently concerted 2e−/2H+ wave when the formal potentials (E1°’ and E3°’) collapse [5,90]. At moderate scan rates, benzo- and naphthoquinones frequently display near-Nernstian ΔEp values of 60–70 mV [129]. Yet, the oxidised quinone (13) is chemically fragile: hydration, Michael addition, and polymerisation occur readily under neutral or basic conditions [5,90,131,132,133,134], compromising long-term reversibility even when CV appears ideal over short timescales. In contrast, the reduced hydroquinone, 13H2, is typically more resistant to decomposition because the aromatic ring is deactivated toward nucleophiles and stabilised by hydrogen bonding or solvation [5,90,131,132,133,134]. Consequently, many quinone systems are best viewed as fast-kinetic, quasi-reversible couples that appear reversible over short timescales but are chemically limited.

Scheme 3.

Bidirectional proton-coupled electron-transfer mechanism for the benzoquinone/hydroquinone couple. Red arrows show the reduction sequence (E1°’–E3°’); blue arrows show the reverse oxidation pathway (E4°–E6°). Horizontal steps denote ET, and vertical steps denote proton transfer. Purple structures are common to both directions.

Across the quinone family, electron-transfer kinetics are generally fast, but the degree of electrochemical reversibility depends strongly on PCET and the stability of the semiquinone (13H•) intermediate. In aqueous media, 13/13H2 couples typically display near-Nernstian behaviour with ΔEp values approaching 59 mV at moderate scan rates when proton transfer is rapid and well coupled to ET, consistent with stepwise ECEC-type PCET mechanisms [135]. Catechols and substituted hydroquinones frequently show ΔEp between 60–80 mV on glassy carbon at 25 °C, with ipa/ipc~1 and minimal scan-rate dependence, reflecting k° in the 10−3–10−2 cm s−1 range [136,137]. These values place typical quinone couples firmly in the quasi-reversible regime under usual aqueous CV conditions, with apparent reversibility improving only when proton transfer is fast and chemical steps remain in pre-equilibrium [138,139].

Departures from ideal behaviour arise primarily from chemical rather than electron-transfer limitations. Semiquinones can undergo disproportionation, proton-loss equilibria, or oxygen-driven radical chemistry, leading to broadened peaks, elevated ΔEp, or loss of cyclic stability, particularly on carbon electrodes [135,140]. Adsorption also plays a significant role: many catechols and polyaromatic quinones interact strongly with graphitic surfaces, giving rise to surface-confined signatures, increased peak currents, and Laviron-type scan-rate scaling rather than pure diffusion control [136,137]. Under such conditions, ET remains rapid, but the apparent electrochemical reversibility becomes modified by interfacial ordering and ion-transport limitations.