Abstract

The YbBO3–ScBO3 system was studied across the selected compositional range by means of solid-state synthesis, powder X-ray diffraction (XRD), differential scanning calorimetry (DSC), and photoluminescence spectroscopy. XRD of annealed samples at 1300–1400 °C revealed that the system reaches equilibrium and consists of two phases, YbBO3 and ScBO3, separated by a two-phase region. The lattice parameters show a limited solubility between Yb3+ and Sc3+ ions. DSC measurements display a broad endothermic feature at approximately 1480 °C, corresponding to the eutectic point. Near-infrared emission excited at 975–980 nm originates from Yb3+ ions and shows the highest intensity for pure YbBO3 and for the Sc-rich composition, while intermediate samples exhibit weaker luminescence.

1. Introduction

The growing demands of photonics and energy applications require inorganic host materials that combine strong optical performance with chemical and thermal robustness [1,2,3]. Rare-earth-based materials meet these requirements by providing stable luminescence and reliable electronic behavior, enabling their use in lasers, phosphors, and sensors. Among NIR emitters, Yb3+ is particularly attractive: its simple two-multiplet 4f configuration produces efficient ~0.92–1.10 µm emission with low sensitivity to non-radiative processes and concentration quenching [4,5,6,7]. In suitable host compounds, Yb3+ exhibits broad emission bands and millisecond-scale lifetimes—features highly desirable for ~1 µm lasers and NIR phosphors. Emission near 1 µm is highly relevant since it falls within the first biological transparency window (700–1200 nm), enabling deep-tissue imaging and biomedical diagnostics. At the same time, this range remains compatible with silicon photodetectors (up to ~1100 nm) and is widely utilized in high-power Yb3+-based lasers for industrial and medical applications [8,9,10].

Orthoborates with the general formula RBO3, where R denotes a trivalent rare-earth cation (Ln3+), are considered promising host lattices due to their high thermal and chemical stability [11,12]. Their rigid BO3 framework and moderate phonon energies help suppress multiphonon relaxation and support efficient Ln3+ luminescence. These favorable characteristics are well documented for a variety of RBO3 hosts, such as YBO3: Eu3+ and (Y,Gd)BO3: Eu3+, as well as Tb3+/Eu3+-activated LuBO3 compositions, all of which demonstrate efficient rare-earth incorporation and strong luminescent response [13,14,15,16,17].

In addition to Eu3+ and Tb3+, many borate hosts have been co-doped with Yb3+ to exploit energy transfer mechanisms. For example, YBO3 co-doped with Yb3+ and Er3+ exhibits red, green, and blue upconversion bands under 980 nm excitation, where Yb3+ acts as a sensitizer transferring energy to Er3+, enabling cooperative Yb3+–Yb3+ luminescence [18]. In Li6Y(BO3)3: Yb3+, UV excitation into the Yb3+ charge-transfer band yields NIR emission (~972 nm), while IR excitation at high Yb3+ content generates blue–green emission via cooperative processes, potentially involving trace Er3+ [19]. Similar behavior is observed in YAl3(BO3)4: Yb3+, Tm3+, where 980 nm excitation produces intense upconversion due to sequential photon absorption by Tm3+ sensitized by Yb3+ [20]. LaBO3: Ce3+, Yb3+ enables UV-to-NIR downconversion via inter-ion charge transfer, achieving over 60% efficiency [21]. GdBO3: Tb3+, Yb3+ is also known for efficient quantum cutting with up to ~182% quantum yield [22].

Within the RBO3 family, ScBO3 crystallizes in a trigonal calcite-type structure (R-3c) and serves as a robust end-member. It can be grown as single crystals and can form limited solid solutions with other rare-earth borates, depending on ionic size mismatch and structure compatibility [23,24,25]. In pseudobinary RBO3–ScBO3 series, three distinct behaviors can be identified depending on the ionic radius of R and the structural polymorphism of the RBO3 end member. For larger lanthanides (Sm, Eu), the system stabilizes mixed borate compounds such as RSc(BO3)2 and RSc3(BO3)4 [26,27]. For intermediate-sized ions such as Tb3+, broad mutual solubility and composition-dependent optical properties have been reported [28]. For the smallest rare-earth ions, the phase behavior depends strongly on polymorphism: Lu-Sc forms continuous calcite-type solid solutions [29,30], whereas Yb-Sc shows only limited Yb3+ substitution into ScBO3 [23]. These contrasting results indicate that not only ionic radius but also structural polymorphism of the RBO3 end-members plays a decisive role in phase behavior across the RBO3–ScBO3 series. A comparison with other RBO3-ScBO3 systems further highlights the unique character of YbBO3–ScBO3.

The YbBO3–ScBO3 system remains poorly studied. Yb3+ (VI, 0.868 Å) differs from the ScBO3 end member based on both ionic radius (Sc3+ VI, 0.745 Å) and the polymorphism of YbBO3, raising the question of whether mixing YbBO3 with ScBO3 yields continuous solid solutions, only limited mutual solubility, or new intermediate phases—as was shown for Eu/Sm systems [31]. This question is directly relevant for photonics, since the distribution of Yb3+ between phases, possible self-absorption, and defect states strongly affect NIR emission efficiency.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Crystal Structure

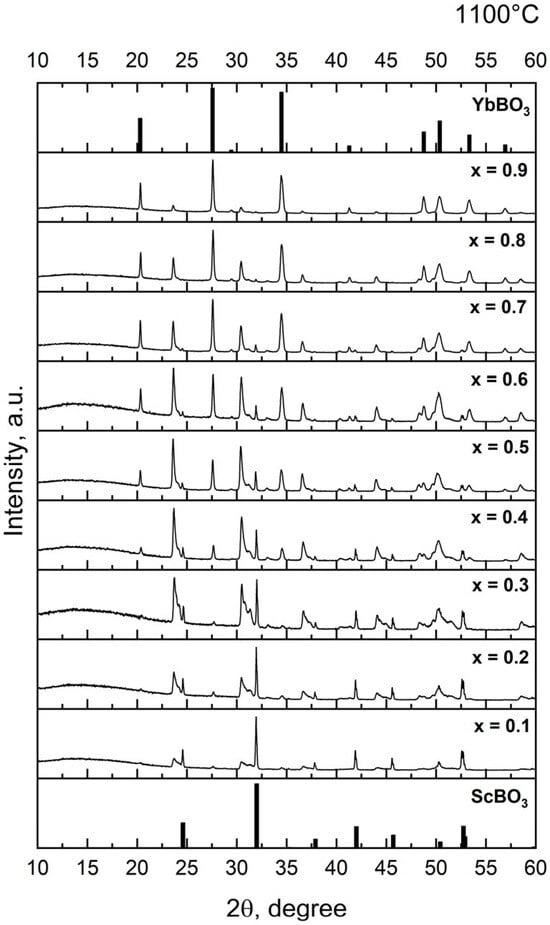

Powder X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns were collected for the xYbBO3–(1 − x)ScBO3 series (x = 0.1–0.9) after annealing at 1100 °C, 1300 °C and 1400 °C (Figure 1). Reference data for the end members were taken from standard structures: P63/mmc for YbBO3 (a = 3.735 Å, c = 8.747 Å) [32] and R-3c for ScBO3 (a = 4.748 Å, c = 15.262 Å) [33]. After annealing at 1100 °C, the reaction of the starting oxides is incomplete and the reflections of the target borates are only weakly developed. In contrast, annealing at 1300–1400 °C yields sharp, well-resolved patterns containing only reflections of YbBO3 and ScBO3. These datasets were used to evaluate lattice parameters and composition-dependent peak shifts.

Figure 1.

XRD patterns of xYbBO3–(1 − x)ScBO3 samples. annealed at 1100 °C, 1300 °C and 1400 °C.

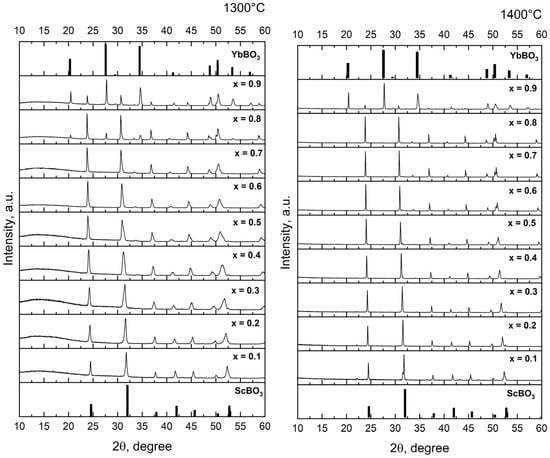

The evolution of a and c for the xYbBO3–(1 − x)ScBO3 series at 1300 °C and 1400 °C is shown in Figure 2. For ScBO3, both parameters increase smoothly with YbBO3 content up to x ≈ 0.8. At higher Yb fractions, the further increase of the ScBO3-related parameters becomes very slight, while values corresponding to the YbBO3 lattice appear, indicating the onset of a YbBO3 + ScBO3 two-phase region rather than a continuous solid solution. Incorporation of Yb3+ into ScBO3 produces a small lattice expansion, whereas partial substitution of Yb3+ by the smaller Sc3+ (0.745 Å, CN = 6) in YbBO3 leads to a minor contraction. Across a narrow interval of intermediate compositions, reflections of both structure types coexist, matching the two-phase field in the phase diagram. Peak positions shift slightly with composition, evidencing only limited mutual solubility between the end members; complete miscibility is not achieved even at 1400 °C.

Figure 2.

Unit cell parameters for samples xYbBO3–(1 − x)ScBO3 annealed at 1300 °C and 1400 °C.

The limited solubility between Yb3+ and Sc3+ can be attributed to their significant ionic radius mismatch: 0.868 Å for Yb3+ and 0.745 Å for Sc3+ [31]. This difference is close to the ~15% threshold outlined by the Goldschmidt rule [34], above which the formation of continuous solid solutions becomes increasingly unfavorable. Experimental observations support this interpretation: homogeneous single-phase samples with higher Yb3+ content were only obtained at elevated synthesis temperatures, indicating that increased thermal energy is required to overcome lattice strain arising from ionic size disparity. No phase separation occurred upon cooling, which enabled preservation of high-temperature single-phase states.

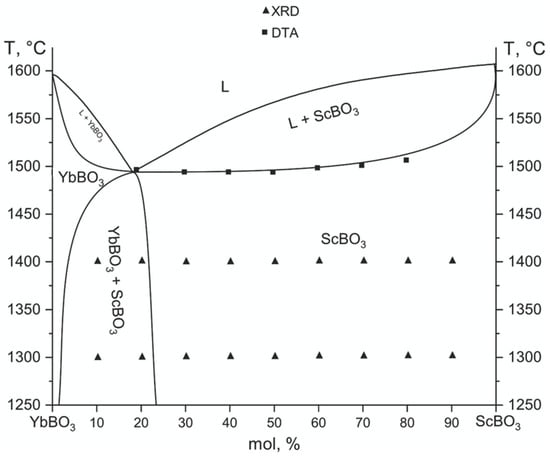

2.2. Thermal Properties

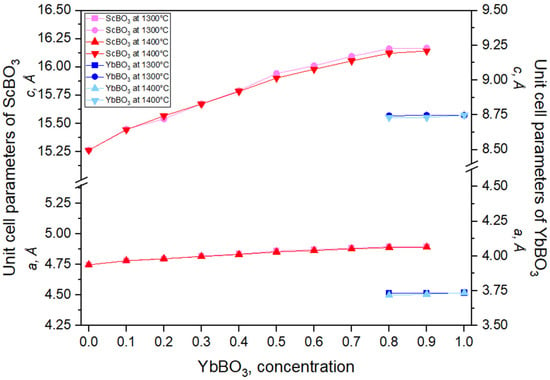

Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) curves for the xYbBO3–(1 − x)ScBO3 series are shown in Figure 3. In general, all samples display a smooth endothermic background up to ~1400 °C with no sharp anomalies, indicating the absence of intermediate compound formation and confirming the phase stability observed by XRD. However, for pure YbBO3 and the composition x = 0.8, an additional endothermic peak appears near 1000 °C, corresponding to a polymorphic transition between the low-temperature and high-temperature modifications of YbBO3. According to [35], this transition occurs at approximately 1040 °C and represents a phase transformation. No such features are detected for Sc-rich samples, confirming that scandium borate remains structurally stable in this range. At higher temperatures, a broad endothermic effect extending to ~1480 °C is observed for all compositions. This temperature corresponds to the eutectic point on the YbBO3–ScBO3 phase diagram, marking the onset of partial melting. Thus, the DSC data confirm that, within the studied temperature range, the system exhibits a simple binary behavior with a eutectic reaction at ~1480 °C and only one polymorphic transformation characteristic of YbBO3.

Figure 3.

DSC curves of the samples in xYbBO3–(1 − x)ScBO3 system.

The phase diagram of the YbBO3–ScBO3 system, shown in Figure 4, was derived from XRD and DSC data. To construct the full high-temperature section of the phase diagram shown in Figure 4, in addition to XRD and DSC results, literature data were used on the melting behavior and thermal stability of the end members—YbBO3 and ScBO3. Specifically, the melting points of the mentioned compounds, as well as their thermal decomposition behavior, were taken from published sources [35,36]. XRD results revealed that at 1300–1400 °C the system reached equilibrium and contained only two stable phases, YbBO3 and ScBO3, separated by a narrow two-phase region (YbBO3 + ScBO3).

Figure 4.

High temperature part of the YbBO3–ScBO3 section phase diagram.

2.3. Luminescence

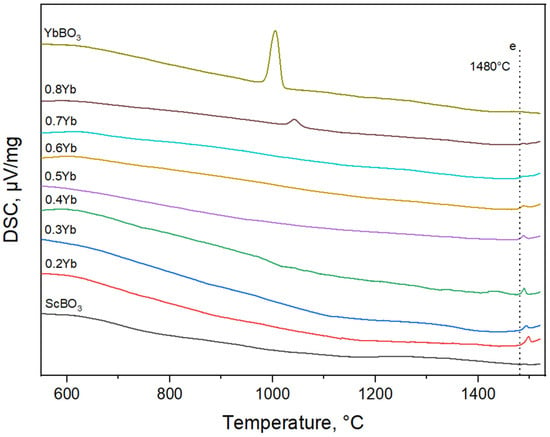

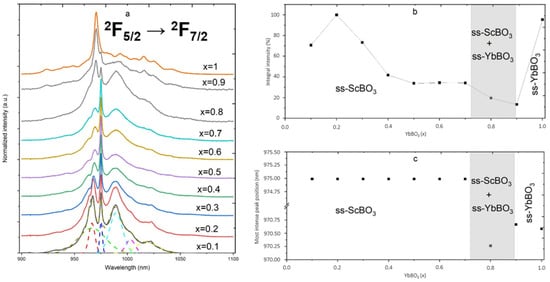

The luminescence spectra of YbBO3–ScBO3 solid solutions were studied at room temperature in the wavelength range of 900–1100 nm (Figure 5a). The main emission peak, corresponding to the 2F5/2 → 2F7/2 transition of Yb3+, lies around 975–980 nm and is marked in Figure 5a. Classical spectra of Yb3+ typically exhibit a series of narrow bands in the near-infrared region, arising from transitions between the spin-orbit components of the 2F7/2 and 2F5/2 multiplet [37]. The studied solid solutions exhibit characteristic features associated with the electronic transitions of Yb3+ ions. A detailed analysis of the spectra revealed several discrete peaks, indicating splitting of the Yb3+ energy levels under the influence of the crystal field of the surrounding lattice [38]. At low YbBO3 concentrations (x = 0.1–0.6), when Yb3+ acts as a dopant in the ScBO3 matrix, narrow peaks are observed, corresponding to transitions within the Yb3+ ion in the specific environment of ScBO3. These peaks are clearly defined and indicate well-defined energy levels.

Figure 5.

(a) Room-temperature photoluminescence spectra of xYbBO3–(1 − x)ScBO3 samples excited at 785 nm; (b) integrated PL intensity; (c) most intensive peak position.

As the YbBO3 content increases (x = 0.7–1), the luminescence spectra undergo significant changes, the peaks broaden, and the spectral structure becomes less distinct. This is possibly due to the formation of solid solutions, in which the environment of the Yb3+ ions becomes more inhomogeneous [39]. Furthermore, at high Yb3+ concentrations, concentration quenching of luminescence is observed, caused by energy exchange between Yb3+ ions, leading to non-radiative transitions and, consequently, a decrease in luminescence intensity [40].

Figure 5b shows the dependence of the integrated luminescence intensity on the solid solution composition. The maximum integrated intensity is observed at low YbBO3 concentrations (x = 0.2), when Yb3+ ions effectively luminesce in the ScBO3 matrix. Interestingly, at low YbBO3 concentrations (x = 0.1–0.6), the position of the main peak remains virtually constant, while the intensity of the side peaks decreases. Although the ScBO3 (calcite-type) structure contains one site for Sc3+ ions, the incorporation of Yb3+ ions can lead to local distortions of the crystal lattice and the formation of defects that affect the crystal field around Yb3+ [41]. A decrease in the intensity of the side peaks may indicate that, as the Yb3+ concentration increases, defects or distortions of a certain type accumulate. This, in turn, can lead to the formation of a spectrum increasingly resembling the spectrum of pure YbBO3, where a certain type of Yb3+ environment dominates. In the gray zone (x = 0.7–0.9), the coexistence of ss–ScBO3 and ss–YbBO3 solid solutions is observed, which may also influence the luminescence pattern.

The position of the maximum luminescence intensity peak also exhibits a compositional dependence (Figure 5c). For ScBO3-rich compositions, the peak position remains virtually unchanged, indicating that the ground state of the Yb3+ ions remains similar. However, for YbBO3-rich compositions, a shift to shorter wavelengths is observed. This shift may be due to a change in the crystal field around the Yb3+ ions upon transition from the ScBO3 to the YbBO3 structure, which affects the energy levels of the Yb3+ ions and, consequently, the position of the luminescence peak. In the gray zone (x = 0.7–0.9), corresponding to the phase coexistence region, a transitional behavior of the peak position is observed.

3. Experimental Procedures

3.1. Synthesis

Polycrystalline samples of the (xYbBO3–(1 − x)ScBO3, x = 0–1) series were synthesized by a two-stage solid-state method in Pt crucibles. In the first stage, YbBO3 and ScBO3 were prepared from stoichiometric mixtures of Yb2O3 (99.9%), Sc2O3 (99.0%), and H3BO3 (99.8%), with a 2 mol% excess of H3BO3 added to compensate for its partial volatility during heating. The reagents were manually ground in an agate mortar using a hand pestle and then heated at 650 °C for 5 h to decompose H3BO3. In the second stage, the obtained YbBO3 and ScBO3 powders were reground in the same manner and annealed at 1100 °C, 1300 °C and 1400 °C for 12 h. After annealing, the samples were rapidly cooled to room temperature by removing the crucibles from the furnace and exposing them to ambient air.

3.2. Powder X-Ray Diffraction

Powder samples of the xYbBO3–(1 − x)ScBO3 series were examined in the Bragg-Brentano geometry using Cu Kα radiation at room temperature. Diffraction patterns were collected on a TD3700 diffractometer (Dandong Tongda Science & Technology Co., Ltd., Dandong, China) over the 2θ range of 10–60°. The unit cell parameters of the samples were refined by the Le Bail method using the The GSAS-II software package (version 5793) [42], with single-crystal data employed as starting models for the refinements. X-ray diffraction patterns were obtained for samples annealed at 1100 °C, 1300 °C and 1400 °C. At 1100 °C, the reflections of the target borate phases were only weakly developed, indicating incomplete reaction of the starting oxides. The data for samples annealed at 1300 °C and 1400 °C were used for further analysis of phase composition and lattice parameters. To assess the phase composition, a comparison with the reference profiles of individual phases was used.

3.3. Thermal Properties Analysis

The thermal properties of powdered samples of the xYbBO3–(1 − x)ScBO3 system with compositions x = 0, 0.2, 0.3, 0.4, 0.5, 0.6, 0.7, 0.8 and 1.0 Yb were investigated by differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) using a STA 449 F5 Jupiter thermal analyzer (Netzsch Pumpen & Systeme GmbH, Waldkraiburg, Germany). Approximately 50 mg of powdered samples were placed in platinum crucibles and heated under flowing argon from room temperature to 1500 °C at a rate of 20 K·min−1. An empty platinum crucible was used as a reference.

3.4. Luminescence Properties

The emission spectra of the compounds were recorded using an The InVia Raman microscope (Renishaw plc, Wotton-under-Edge, UK) under the excitation of a 785 nm CW diode laser in the range of 900–1100 nm. While the main absorption of Yb3+ (2F7/2 → 2F5/2 transition) typically peaks near 975–980 nm, this transition forms a broad absorption band spanning ~800–1080 nm in crystalline and glassy hosts, allowing for appreciable absorption even near 785 nm [43,44,45]. Additionally, in some co-doped systems (e.g., Ho/Tm/Yb-doped zirconates), absorption features at 785 nm have been directly observed [46].

4. Conclusions

The YbBO3–ScBO3 system, in the subsolidus temperature range of 1300–1400 °C, shows two single-phase regions of YbBO3 and ScBO3 separated by a narrow two-phase field (YbBO3 + ScBO3). X-ray diffraction confirmed that equilibrium is achieved at 1300–1400 °C without the formation of intermediate compounds. Thermal analysis shows a single eutectic reaction at ~1480 °C, marking the onset of partial melting. Photoluminescence measurements show near-infrared emission typical of Yb3+, with the strongest intensity observed for pure YbBO3 and for the Sc-rich composition containing about 20 mol.% YbBO3 (x ≈ 0.2), while intermediate samples exhibit noticeably weaker luminescence. These findings outline a consistent subsolidus section of the YbBO3–ScBO3 phase relations rather than a full equilibrium diagram and highlight its relevance as a model system for structure–property correlations in rare-earth borates. ScBO3 emerges as a robust, transition-free host that accommodates appreciable Yb3+ and is promising for multi-element rare-earth doping and NIR-emitting applications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.Z., A.K. and K.K.; methodology, A.K., K.K. and V.S.; validation, Y.Z. and A.K.; investigation, Y.Z., A.K. and A.J.; data curation, Y.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.Z., A.K. and K.K.; writing—review and editing, Y.Z., A.K., K.K. and V.S.; visualization, Y.Z., A.K. and A.J.; supervision, A.B. and K.K.; funding acquisition, A.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The work was supported by the Grant Financing of the Science Committee of the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Republic of Kazakhstan “Crystal chemistry and optical properties of functional ytterbium orthoborates” [Grant No. IRN AP19575956] and state assignment of IGM SB RAS (FWZN-2026-0005).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Lee, J.; Min, K.; Park, Y.; Cho, K.-S.; Jeon, H. Photonic Crystal Phosphors Integrated on a Blue LED Chip for Efficient White Light Generation. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, 1703506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- der Heggen, D.; Joos, J.J.; Smet, P.F. Importance of Evaluating the Intensity Dependency of the Quantum Efficiency: Impact on LEDs and Persistent Phosphors. ACS Photonics 2018, 5, 4529–4537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baba, T. Slow Light in Photonic Crystals. Nat. Photonics 2008, 2, 465–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, C.T.; Jeong, S.; Dorlhiac, G.F.; Landry, M.P. Advances in Engineering Near-Infrared Luminescent Materials. iScience 2021, 24, 102156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Guzman, G.N.A.; Fang, M.-H.; Liang, C.-H.; Bao, Z.; Hu, S.-F.; Liu, R.-S. Near-Infrared Phosphors and Their Full Potential: A Review on Practical Applications and Future Perspectives. J. Lumin. 2020, 219, 116944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Li, Y.; Peng, M. Near-Infrared Persistent Phosphors: Synthesis, Design, and Applications. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 399, 125688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, X.; Wang, J.; Yuan, Q. Synthesis and Biomedical Applications of Lanthanides-Doped Persistent Luminescence Phosphors with NIR Emissions. Front. Chem. 2020, 8, 608578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, A.; Dhar, A.; Das, S.; Chen, S.Y.; Sun, T.; Sen, R.; Grattan, K.T. V Ytterbium-Sensitized Thulium-Doped Fiber Laser in the near-IR with 980 Nm Pumping. Opt. Express 2010, 18, 5068–5074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukushima, S.; Furukawa, T.; Niioka, H.; Ichimiya, M.; Sannomiya, T.; Tanaka, N.; Onoshima, D.; Yukawa, H.; Baba, Y.; Ashida, M.; et al. Correlative Near-Infrared Light and Cathodoluminescence Microscopy Using Y2O3:Ln, Yb (Ln = Tm, Er) Nanophosphors for Multiscale, Multicolour Bioimaging. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 25950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Aléo, A.; Bourdolle, A.; Brustlein, S.; Fauquier, T.; Grichine, A.; Duperray, A.; Baldeck, P.L.; Andraud, C.; Brasselet, S.; Maury, O. Ytterbium-Based Bioprobes for near-Infrared Two-Photon Scanning Laser Microscopy Imaging. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 6622–6625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Z.; Wen, Y.-L.; Sun, N.; Wang, Y.-F.; Huang, Y.; Gao, Z.-H.; Tao, Y. Morphologies of GdBO3:Eu3+ One-Dimensional Nanomaterials. J. Alloys Compd. 2010, 489, L9–L12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Zhang, C.; Wang, L.; Hou, Z.; Huang, S.; Lian, H.; Lin, J. Hydrothermal Synthesis and Luminescent Properties of LuBO3:Tb3+ Microflowers. J. Solid State Chem. 2008, 181, 2672–2680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eliseeva, S.V.; Bünzli, J.C.G. Lanthanide Luminescence for Functional Materials and Bio-Sciences. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010, 39, 189–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Li, C.; Zhang, X.; Quan, Z.; Zhang, C.; Li, H.; Lin, J. Self-Assembled 3D Architectures of LuBO3:Eu3+: Phase-Selective Synthesis, Growth Mechanism, and Tunable Luminescent Properties. Chem. A Eur. J. 2008, 14, 4336–4345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.N.; Jung, H.-K.; Park, H.D.; Kim, D. Synthesis and Characterization of Red Phosphor (Y, Gd)BO3:Eu by the Coprecipitation Method. J. Mater. Res. 2002, 17, 907–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosokawa, S.; Tanaka, Y.; Iwamoto, S.; Inoue, M. Morphology and Structure of Rare Earth Borate (REBO3) Synthesized by Glycothermal Reaction. J. Mater. Sci. 2008, 43, 2276–2285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tukia, M.; Hölsä, J.; Lastusaari, M.; Niittykoski, J. Eu3+ Doped Rare Earth Orthoborates, RBO3 (R = Y, La and Gd), Obtained by Combustion Synthesis. Opt. Mater. 2005, 27, 1516–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera-López, F.; Torres, M.E.; Gil de Cos, G. Upconversion and Cooperative Luminescence in YBO3:Yb3+-Er3+. Mater. Today Commun. 2021, 27, 102434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sablayrolles, J.; Jubera, V.; Guillen, F.; Decourt, R.; Couzi, M.; Chaminade, J.P.; Garcia, A. Infrared and Visible Spectroscopic Studies of the Ytterbium Doped Borate Li6Y(BO3)3. Opt. Commun. 2007, 280, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleksandrovsky, A.S.; Gudim, I.A.; Krylov, A.S.; Malakhovskii, A.V.; Temerov, V.L. Upconversion Luminescence of YAl3(BO3)4:(Yb3+,Tm3+) Crystals. J. Alloys Compd. 2010, 496, L18–L21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, H.-W.; Shao, L.-M.; Jiao, H.; Jing, X.-P. Ultraviolet and Near-Infrared Luminescence of LaBO3:Ce3+, Yb3+. Opt. Mater. 2018, 75, 442–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.Y.; Yang, C.H.; Jiang, Z.H.; Ji, X.H. Concentration-Dependent near-Infrared Quantum Cutting in GdBO3:Tb3+, Yb3+ Nanophosphors. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2007, 90, 061914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, D.; Pan, Z.; Yu, H.; Zhang, H.; Wang, J. Exploration of Yb3+:ScBO3-A Novel Laser Crystal in the Rare-Earth Ion Doped Orthoborate System. Opt. Mater. Express 2015, 5, 1822–1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Ma, H.; Zhang, X.; Chen, L.; Chen, S.; Li, H. First-Principles Prediction of Mechanical, Electrical, and Optical Properties in Borates MBO3 (M = Sc, Al, Ga, Ti). Phys. Scr. 2025, 100, 095907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Lu, D.; Yu, H.; Zhang, H. Compact Acousto-Optical Q-Switched Yb:ScBO3 Laser with Giant Pulse Energy. Opt. Lett. 2022, 47, 5877–5880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuznetsov, A.B.; Kokh, K.A.; Kononova, N.G.; Shevchenko, V.S.; Rashchenko, S.V.; Lapin, I.N.; Svetlichnyi, V.A.; Uralbekov, B.; Bolatov, A.; Simonova, E.A.; et al. Study of an SmBO3–ScBO3 System and New SmSc(BO3)2 Orthoborate. CrystEngComm 2021, 23, 1482–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuznetsov, A.B.; Kokh, K.A.; Kaneva, E.V.; Svetlichnyi, V.A.; Kononova, N.G.; Shevchenko, V.S.; Rashchenko, S.V.; Kokh, A.E. Study of an EuBO3-ScBO3 System and EuSc3(BO3)4, EuSc(BO3)2 Orthoborates. Dalt. Trans. 2021, 50, 13894–13901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokh, A.E.; Kuznetsov, A.B.; Svetlichnyi, V.A.; Rakhmanova, M.I.; Klimov, A.O.; Kokh, K.A. Green Photoluminescence in TbxSc1−xBO3 Solid Solution. J. Lumin. 2024, 275, 120768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Ding, D.; Pan, S.; Yang, F.; Ren, G. Luminescence Characteristics of Ce3+-Doped Lu1−xScxBO3 Solid Solution Single Crystals Grown by Czochralski Method. Opt. Mater. 2011, 33, 655–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.T.; Ding, D.Z.; Pan, S.K.; Yang, F.; Ren, G.H. Czochralski Growth of Lu1−xScxBO3:Ce Solid Solution Crystals. Cryst. Res. Technol. 2011, 46, 48–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, R.D. Revised Effective Ionic Radii and Systematic Studies of Interatomic Distances in Halides and Chalcogenides. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. A 1976, A32, 751–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newnham, R.E.; Redman, M.J.; Santoro, R.P. Crystal Structure of Yttrium and Other Rare-Earth Borates. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 1963, 46, 253–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keszler, D.A.; Sun, H.X. Structure of SCBO3. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. C Cryst. Struct. Commun. 1988, 44, 1505–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldschmidt, V.M. Die Gesetze Der Krystallochemie. Naturwissenschaften 1926, 14, 477–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedorov, P.P. Morphotropism of Rare-Earth Orthoborates RBO3. J. Struct. Chem. 2019, 60, 679–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadov, M.M.; Akhmedova, N.A.; Mamedova, S.R.; Tagiev, D.B. Phase Equilibria Thermodynamic Analysis, and Electrical Properties of Samples in the System Li2O–B2O3–Yb2O3. Russ. J. Inorg. Chem. 2020, 65, 1061–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.; Zhu, H.; Li, R.; Tu, D.; Liu, Y.; Luo, W.; Chen, X. Visible-to-Infrared Quantum Cutting by Phonon-Assisted Energy Transfer in YPO4: Tm3+, Yb3+ Phosphors. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2012, 14, 6974–6980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, R.; Huang, D.; Lu, D.; Liang, F.; Zhang, Q.; Yu, H.; Zhang, H. Investigation of Crystal Field Effects for the Spectral Broadening of Yb3+-Doped LuxY2−xO3 Sesquioxide Crystals. RSC Adv. 2022, 12, 22555–22563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beil, K.; Saraceno, C.J.; Schriber, C.; Emaury, F.; Heckl, O.H.; Baer, C.R.E.; Golling, M.; Südmeyer, T.; Keller, U.; Kränkel, C.; et al. Yb-Doped Mixed Sesquioxides for Ultrashort Pulse Generation in the Thin Disk Laser Setup. Appl. Phys. B Lasers Opt. 2013, 113, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, P.; Deng, P.; Yin, Z. Concentration Quenching in Yb:YAG. J. Lumin. 2002, 97, 51–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishii, A.; Miyasaka, T. Quantum Cutting-Induced near-Infrared Luminescence of Yb3+ and Er3+ in a Layer Structured Perovskite Film. J. Chem. Phys. 2020, 153, 194704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toby, B.H.; Von Dreele, R.B. GSAS-II: The Genesis of a Modern Open-Source All Purpose Crystallography Software Package. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2013, 46, 544–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiesholler, L.M.; Frenzel, F.; Grauel, B.; Würth, C.; Resch-Genger, U.; Hirsch, T. Yb, Nd, Er-Doped Upconversion Nanoparticles: 980 Nm versus 808 Nm Excitation. Nanoscale 2019, 11, 13440–13449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martín, I.R.; Méndez-Ramos, J.; Rodríguez, V.D.; Romero, J.J.; García-Solé, J. Increase of the 800 Nm Excited Tm3+ Blue Upconversion Emission in Fluoroindate Glasses by Codoping with Yb3+ Ions. Opt. Mater. 2003, 22, 327–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, S.; Nukui, A.; Soga, K.; Makishima, A. Effect of Yb3+-Codoping on the Upconversion Emission Intensity in Er3+-Doped ZBLAN Fluoride Glasses under 800-nm Excitation. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 1994, 77, 2433–2436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, K.; Zhang, Q.; Kong, J.; Hao, Y.; Wu, W.; Wang, Y.; Lin, H.; Xu, S.; Deng, W. Highly Efficient Ultraviolet and Visible Light Emissions from Upconversion Transitions in Ho/Tm/Yb Co-Doped Lutecia-Stabilized Zirconia Single Crystals Excited by a 980 Nm Laser. CrystEngComm 2024, 26, 5907–5915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.