Formation and Reversible Cleavage of an Unusual Trisulfide-Bridged Binuclear Pyridine Diimine Iridium Complex

Abstract

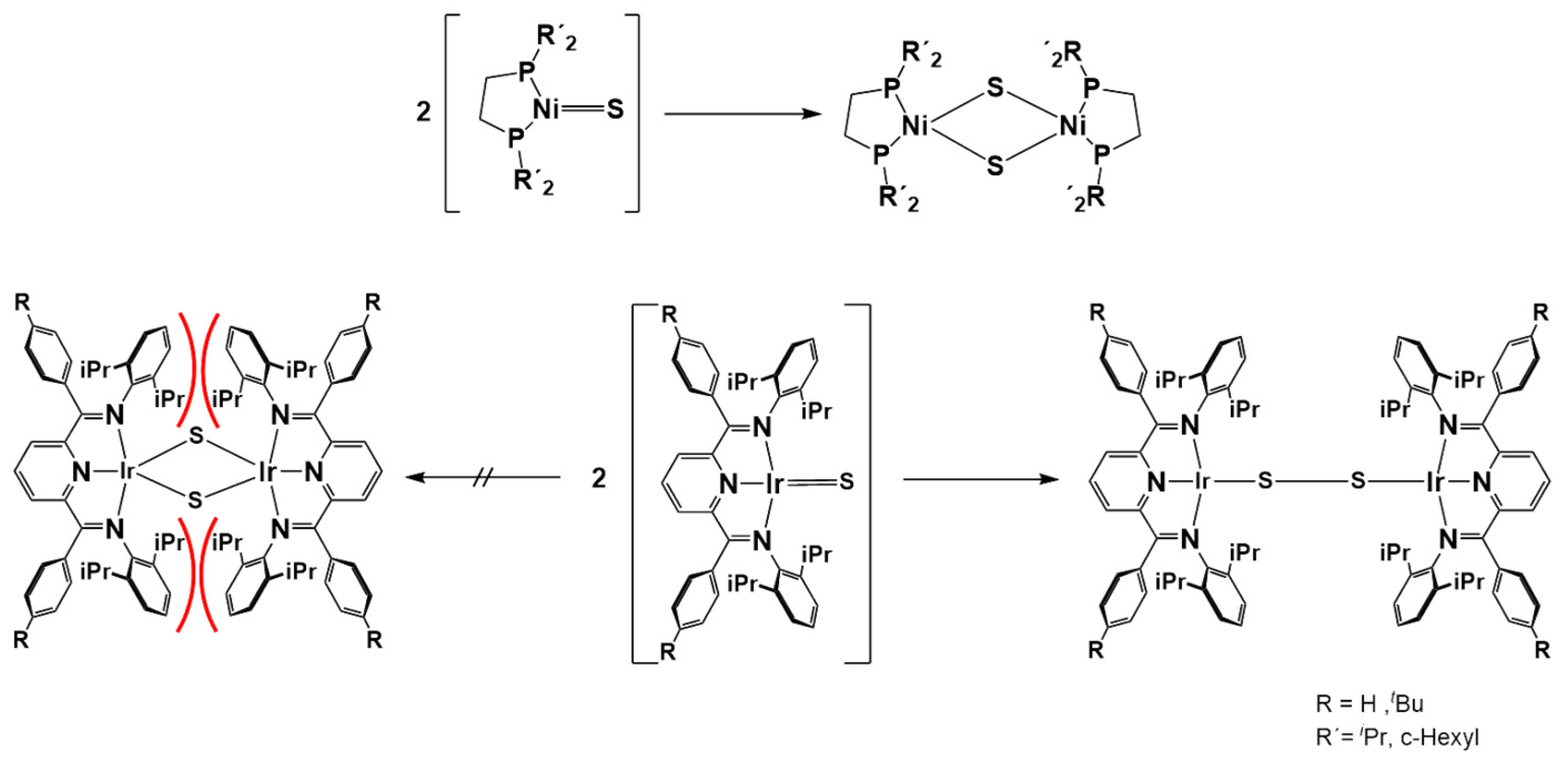

1. Introduction

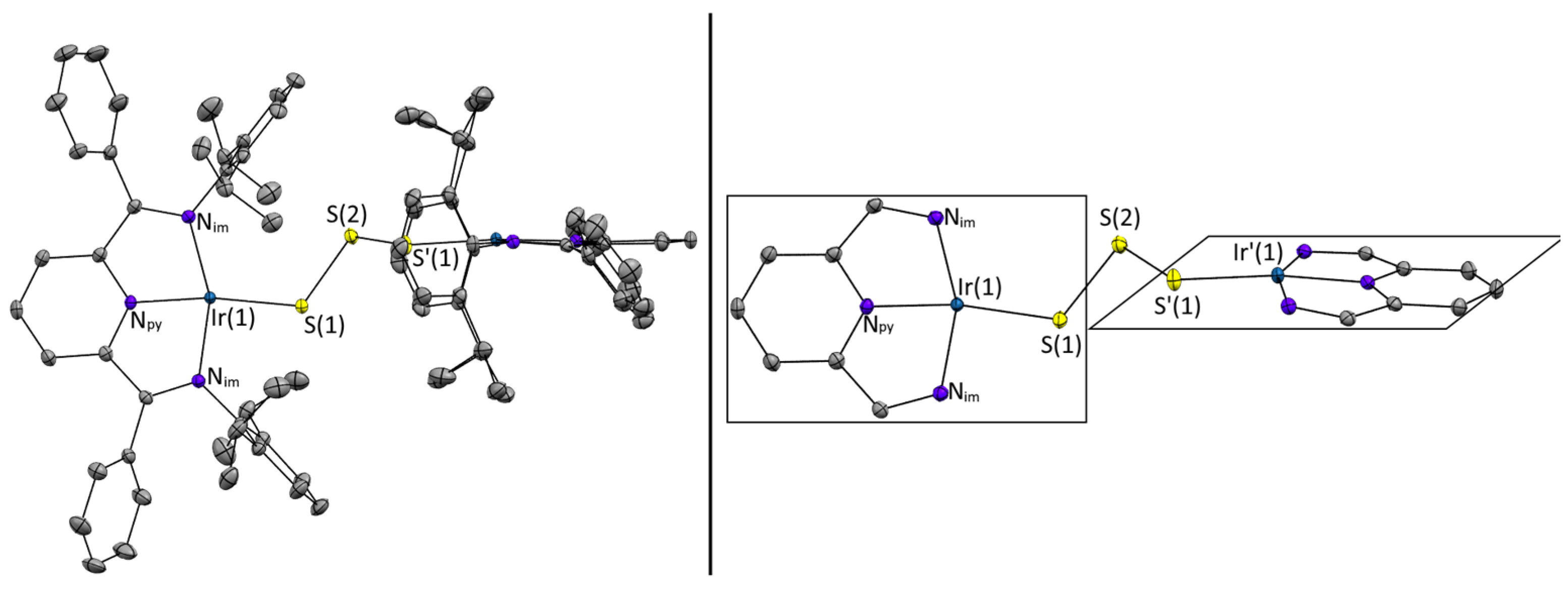

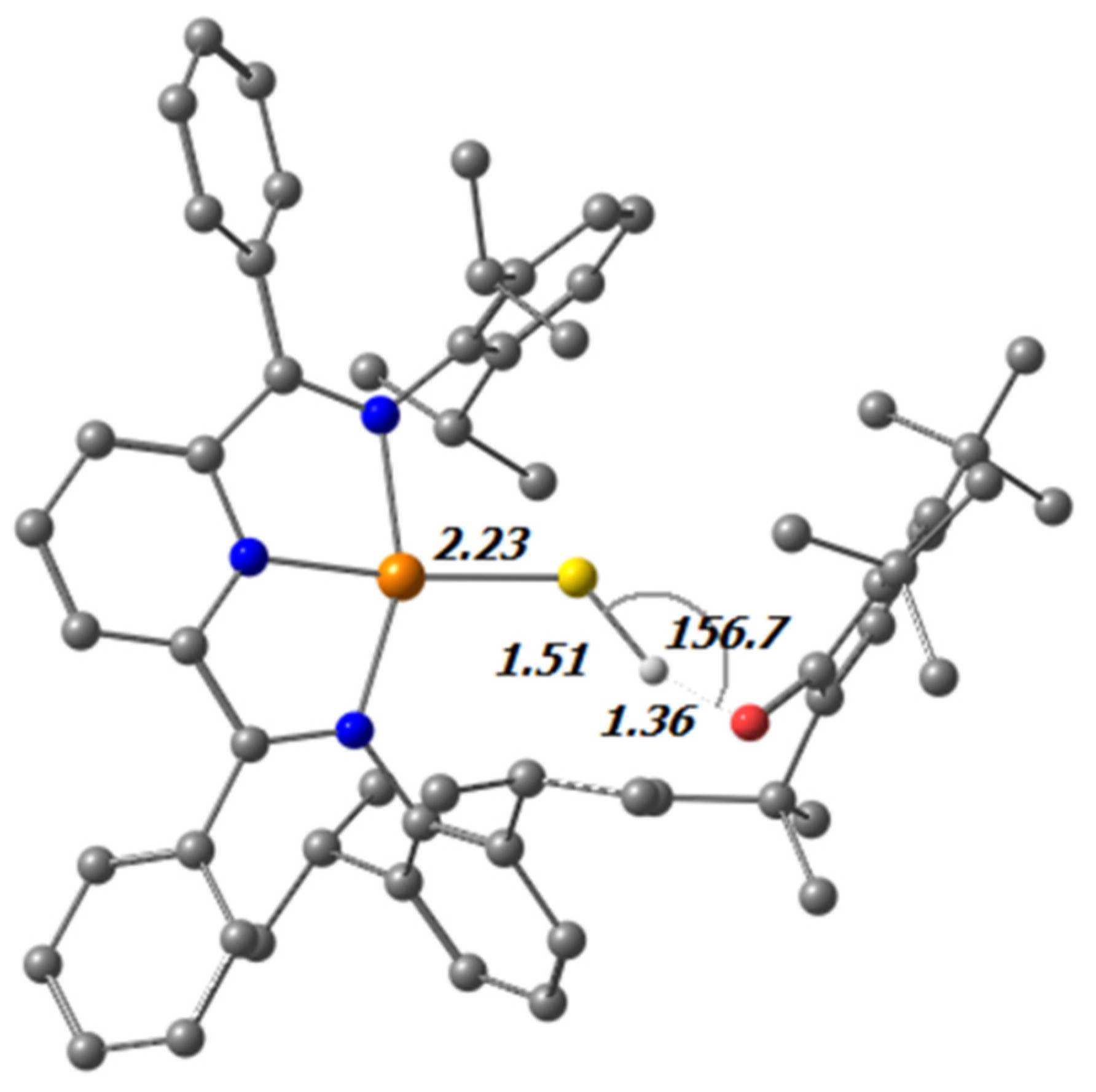

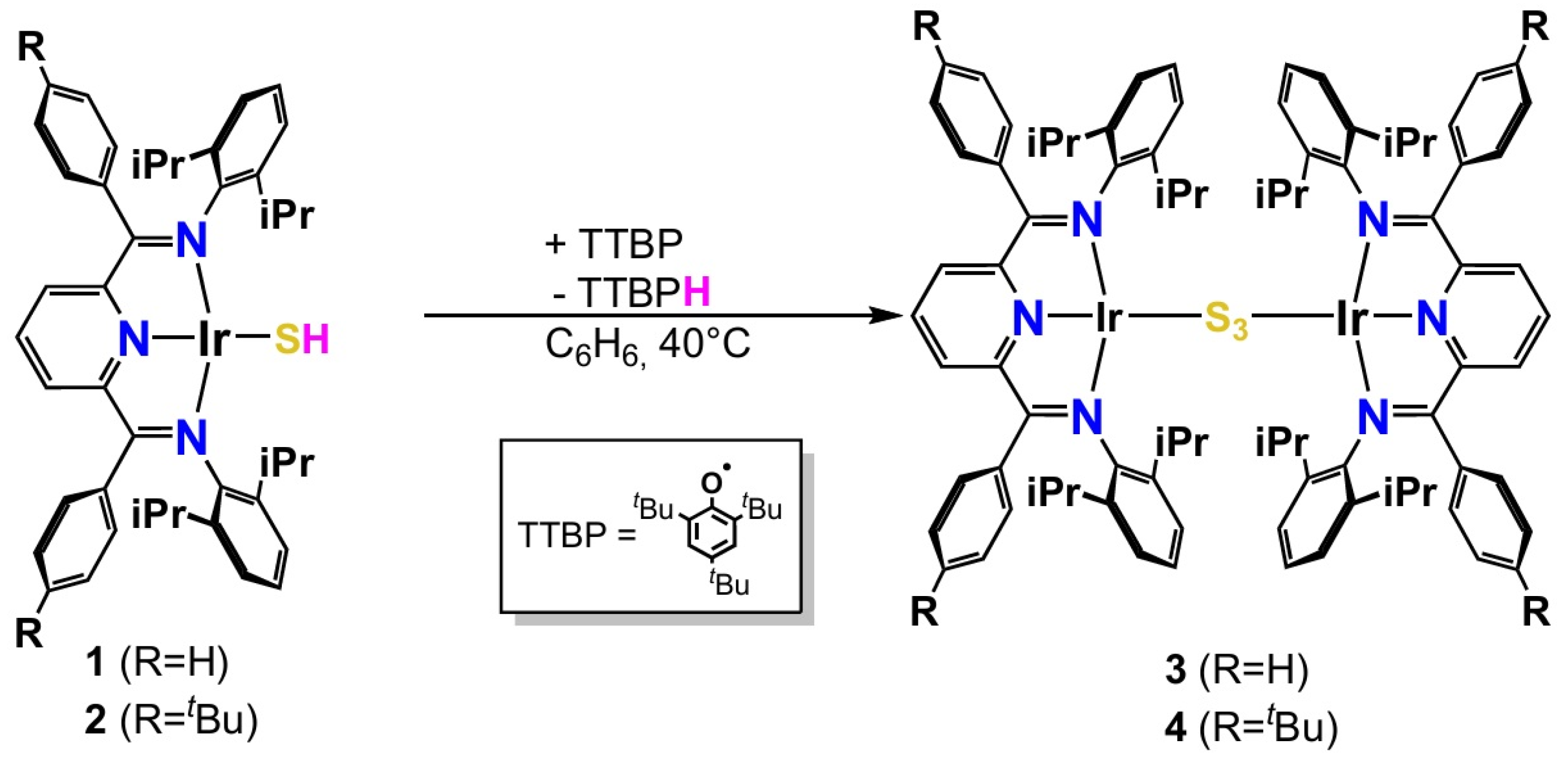

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. HAA Reaction

- (i)

- Direct addition to the disulfide Ir-S2-Ir core or

- (ii)

- Rear-side nucleophilic addition to the pyridine para-position of IrS2Ir, yielding an IrSpy-Ir-S2Ir adduct and consecutive release of IrS2•.

2.2. Dissociation Reaction

2.2.1. In the Presence of H2 Atmosphere

2.2.2. Absence of H2 Atmosphere

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Instrumentation

3.2. Synthesis and Characterization

3.2.1. Complexes 2, 5 and 6

3.2.2. Complex 3

| LIFDI-MS | (C86H94Ir2N6S3)+: | calc.: 1692.60 Da | meas.: 1692.6 Da (100%) |

| (C43H45IrN3)+: | calc.: 796.3 Da | meas.: 796.3 Da (85%) |

| CHN | |||||

| Ir-S3-Ir (C86H94Ir2N6S3) | calc. [%] | C: 61.04 | H: 5.60 | N: 4.97 | S: 5.68 |

| Ir-S2-Ir (C86H94Ir2N3S2) | calc. [%] | C: 62.21 | H: 5.71 | N: 5.06 | S: 3.86 |

| meas. [%] | C: 62.90 | H: 6.16 | N: 4.69 | S: 4.05 |

3.2.3. Complex 4

| MALDI | [Ir-S]+ | calc.: 942.437 Da | meas.: 942.584 Da (11%) |

| [Ir-S-S-Ir]-3H+ | calc.: 1881.851 Da | meas.: 1181.890 Da (2%) | |

| [Ir-S-S-S-Ir]+: | calc.: 1916.786 Da | meas.: 1916.870 Da (2%) |

3.2.4. Dimerization of Complex 1 with External Ferrocene Standard

3.2.5. Thermolysis with Internal Standard 1,4-Dimethoxybenzene

3.2.6. Thermolysis with External Standard Ferrocene

3.3. DOSY 1H NMR Spectroscopy

3.4. LIFDI-MS

Sample Synthesis/Preparation

3.5. Theoretical Methods

3.5.1. DFT Calculations

3.5.2. Local Coupled Cluster Calculations

3.5.3. Thermochemical Corrections

3.5.4. Excited-State Calculations

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sieh, D.; Burger, P. Si-H Activation in an Iridium Nitrido Complex—A Mechanistic and Theoretical Study. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 3971–3982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schiller, C.; Sieh, D.; Lindenmaier, N.; Stephan, M.; Junker, N.; Reijerse, E.; Granovsky, A.A.; Burger, P. Cleavage of an Aromatic C-C Bond in Ferrocene by Insertion of an Iridium Nitrido Nitrogen Atom. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 11392–11401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schöffel, J.; Rogachev, A.Y.; George, S.D.B.; Burger, P. Isolation and Hydrogenation of a Complex with a Terminal Iridium-Nitrido Bond. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 4734–4738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schöffel, J.; Šušnjar, N.; Nückel, S.; Sieh, D.; Burger, P. 4d vs. 5d—Reactivity and Fate of Terminal Nitrido Complexes of Rhodium and Iridium. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2010, 2010, 4911–4915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephan, M.; Völker, M.; Schreyer, M.; Burger, P. Syntheses, Crystal and Electronic Structures of Rhodium and Iridium Pyridine Di-Imine Complexes with O- and S-Donor Ligands: (Hydroxido, Methoxido and Thiolato). Chemistry 2023, 5, 1961–1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Römelt, C.; Weyhermüller, T.; Wieghardt, K. Structural Characteristics of Redox-Active Pyridine-1,6-Diimine Complexes: Electronic Structures and Ligand Oxidation Levels. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2019, 380, 287–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabo, K.J.; Wendt, O.F. Pincer-Type Complexes, 1st ed.; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- De Bruin, B.; Bill, E.; Bothe, E.; Weyhermüller, T.; Wieghardt, K. Molecular and Electronic Structures of Bis(Pyridine-2,6-Diimine)Metal Complexes [ML2](PF6)(n) (n = 0, 1, 2, 3; M = Mn, Fe, Co, Ni, Cu, Zn). Inorg. Chem. 2000, 39, 2936–2947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budzelaar, P.H.M.; De Bruin, B.; Gal, A.W.; Wieghardt, K.; Van Lenthe, J.H. Metal-to-Ligand Electron Transfer in Diiminopyridine Complexes of Mn-Zn. A Theoretical Study. Inorg. Chem. 2001, 40, 4649–4655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.; Budzelaar, P.H.M. A Measure for σ-Donor and π-Acceptor Properties of Diiminepyridine-Type Ligands. Organometallics 2008, 27, 2699–2705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sieh, D.; Schlimm, M.; Andernach, L.; Angersbach, F.; Nückel, S.; Schöffel, J.; Šušnjar, N.; Burger, P. Metal-Ligand Electron Transfer in 4d and 5d Group 9 Transition Metal Complexes with Pyridine, Diimine Ligands. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2012, 2012, 444–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Völker, M.; Schreyer, M.; Burger, P. Hydrogenation Studies of Iridium Pyridine Diimine Complexes with O- and S-Donor Ligands (Hydroxido, Methoxido and Thiolato). Chemistry 2024, 6, 1230–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šušnjar, N. Towards Rhodium and Iridium Oxo Complexes. Ph.D. Dissertation, Universität Hamburg, Hamburg, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kuwata, S.; Hidai, M. Hydrosulfido complexes of transition metals. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2001, 213, 211–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabinovich, D.; Parkin, G. Terminal Sulfido, Selenido, and Tellurido Complexes of Tungsten. Inorg. Chem. 1995, 34, 6341–6361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seino, H.; Iwata, N.; Kawarai, N.; Hidai, M.; Mizobe, Y. A Series of Dinuclear Homo- and Heterometallic Complexes with Two or Three Bridging Sulfido Ligands Derived from the Tungsten Tris(Sulfido) Complex [Et4N][(Me2Tp)WS3] (Me2Tp=Hydridotris (3,5-Dimethylpyrazol-1-yl) Borate). Inorg. Chem. 2003, 42, 7387–7395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawaguchi, H.; Yamada, K.; Lang, J.; Tatsumi, K. A New Entry into Molybdenum/ Tungsten Sulfur Chemistry: Synthesis and Reactions of Mononuclear Sulfido Complexes of Pentamethylcyclopentadienyl—Molybdenum (VI) and—Tungsten (VI). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997, 119, 10346–10358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatsumi, K.; Inoue, Y.; Kawaguchi, H.; Kohsaka, M.; Nakamura, A.; Cramer, R.E.; Vandoorne, W.; Taogoshi, G.J.; Richmann, P.N. Structural Diversity of Sulfide Complexes Containing Half-Sandwich Cp*Ta and Cp*Nb Fragments. Organometallics 1993, 12, 352–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatsumi, K.; Inoue, Y.; Nakamura, A.; Cramer, R.E.; VanDoorne, W.; Gilje, J.W. Synthesis of (C5Me5)Ta(S)3 2− and the Structure of a Hexagonal- Prismatic Ta2Li4S6 Core. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1989, 111, 782–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, N.J.; Wu, G.; Hayton, T.W. Synthesis of a “Masked” Terminal Nickel (II) Sulfide by Reductive Deprotection and its Reaction with Nitrous Oxide. Angew. Chem. 2015, 127, 15169–15172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, N.J.; Wu, G.; Hayton, T.W. Activation of CS2 by a “Masked” Terminal Nickel Sulfide. Dalton Trans. 2016, 45, 14508–14510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esmieu, C.; Orio, M.; Torelli, S.; Le Pape, L.; Pécaut, J.; Lebrun, C.; Ménage, S. N2O Reduction at a Dissymmetric {Cu2S}-Containing Mixed-Valent Center. Chem. Sci. 2014, 5, 4774–4784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagherzadeh, S.; Mankad, N.P. Oxidation of a [Cu2S] Complex by N2O and CO2: Insights into a Role of Tetranuclearity in the CuZ Site of Nitrous Oxide Reductase. Chem. Commun. 2018, 54, 1097–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanahan, J.P.; Vicic, D.A.; Brennessel, W.W.; Jones, W.D. Trapping of a Late-Metal Terminal Sulfido Intermediate with Phenyl Isothiocyanate. Organometallics 2022, 41, 3448–3453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, N.; Goetz, M.K.; Schneider, J.E.; Anderson, J.S. Testing the Limits of Imbalanced CPET Reactivity: Mechanistic Crossover in H-Atom Abstraction by Co(III)−Oxo Complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 5664–5673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, J.M. Hydrogen Atom Abstraction by Metal—Oxo Complexes: Understanding the Analogy with Organic Radical Reactions. Acc. Chem. Res. 1998, 31, 441–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.-T.; Juarez, R.A.; Scepaniak, J.J.; Munoz, S.B.; Dickie, D.A.; Wang, H.; Smith, J.M. Reaction of an Iron(IV) Nitrido Complex with Cyclohexadienes: Cycloaddition and Hydrogen-Atom Abstraction. Inorg. Chem. 2014, 53, 8425–8430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, B.J.; Barona, M.; Johnson, S.I.; Raugei, S.; Bullock, R.M. Weakening the N−H Bonds of NH3 Ligands: Triple Hydrogen-Atom Abstraction to Form a Chromium(V) Nitride. Inorg. Chem. 2022, 61, 11165–11172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tagliavini, V.; Duan, P.C.; Chatterjee, S.; Ferretti, E.; Dechert, S.; Demeshko, S.; Kang, L.; Peredkov, S.; DeBeer, S.; Meyer, F. Cooperative Sulfur Transformations at a Dinickel Site: A Metal Bridging Sulfur Radical and Its H-Atom Abstraction Thermochemistry. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2024, 146, 23158–23170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, P.L.; Gupta, R.; Powell, D.R.; Borovik, A.S. Chalcogens as Terminal Ligands to Iron: Synthesis and Structure of Complexes with Fe III—S and Fe III—Se Motifs. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 6522–6523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdez-Moreira, J.A.; Wannipurage, D.C.; Pink, M.; Carta, V.; Smith, J.M.; Valdez-moreira, J.A.; Wannipurage, D.C.; Pink, M.; Carta, V. Hydrogen Atom Abstraction by a High-Spin [FeIII = S] Complex. Chem 2023, 9, 2601–2609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicic, D.A.; Jones, W.D. Evidence for the Existence of a Late-Metal Terminal Sulfido Complex. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999, 121, 4070–4071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobbs, D.A.; Bergman, R.G. Late Transition-Metal Sulfido Complexes: Reactivity Studies and Mechanistic Analysis of Their Conversion into Metal-Sulfur Cubane Complexes. Inorg. Chem. 1994, 33, 5329–5336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selnau, H.E.; Merola, J.S. Reactions of [Ir(COD)(PMe3)3]Cl with Benzene, Pyridine, Furan, and Thiophene: C-H Cleavage vs Ring Opening. Organometallics 1993, 12, 1583–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, R.; Cowie, M. Sulfur-Hydrogen and Selenium- Hydrogen Bond Activation by Both Metal Centers in [MM’(CO)3(Ph2PCH2PPh2)2] (M, M’=Rh, Ir). Inorg. Chem. 1993, 32, 1671–1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Gruel, M.A.F.; Dobrinovitch, I.T.; Lahoz, F.J.; Oro, L.A. The Anions [Cp(Tt)2Zr(µ-S)2M(CO)2]- (M=Rh, Ir) as Versatile Precursors for the Synthesis of Sulfido-Bridged Early—Late Heterotrimetallic (ELHT) Compounds. Organometallics 2007, 26, 6437–6446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olechnowicz, F.; Hillhouse, G.L.; Jordan, R.F. Synthesis and Reactivity of NHC-Supported Ni2(μ2-η2, η2-S2)-Bridging Disulfide and Ni2(μ-S)2-Bridging Sulfide Complexes. Inorg. Chem. 2015, 54, 2705–2712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, R.; Deng, Z.; Rogerson, A.K.; Mclachlan, A.S.; Richards, J.J.; Nilsson, M.; Morris, G.A. Quantitative Interpretation of Diffusion-Ordered NMR Spectra : Can We Rationalize Small Molecule Diffusion Coefficients? Angew. Chem. 2013, 125, 3281–3284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, R.; Poggetto, G.D.; Nilsson, M.; Morris, G.A. Improving the Interpretation of Small Molecule Diffusion Coefficients. Anal. Chem. 2018, 90, 3987–3994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SEGWE Calculator: Diffusion Coefficient and Molecular Weight Estimation. Available online: https://nmr.chemistry.manchester.ac.uk/?q=node/432 (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- Teo, B.-K.; Snyder-Robinson, P.A. Metal-Tetrathiolene Chemistry: The First Disulphur Bridge in the Novel Di -Iridium Cluster (Ph3P)2(CO)2Br2Ir2(C10H4S4). X-Ray Crystal Structure. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 1979, 255–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishioka, T.; Kitayama, H.; Breedlove, B.K.; Shiomi, K.; Kinoshita, I.; Isobe, K. Novel Nucleophilic Reactivity of Disulfido Ligands Coordinated Parallel to M − M (M= Rh, Ir) Bonds. Inorg. Chem. 2004, 43, 5688–5697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolinger, C.M.; Rauchfuss, T.B.; Wilson, S.R. Synthesis and Characterization of a Cyclic Bimetallic Complex of the Trisulfide Ion. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1981, 103, 5620–5621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Hinnawi, M.A.; Aruffo, A.A.; Santarsiero, B.D.; McAlister, D.R.; Schomaker, V. Organometallic Sulfur Complexes. 1. Syntheses, Structures, and Characterizations of Organoiron Sulfane Complexes (µ -Sx)[(η5 -C5H5)Fe(CO)2]2 (x = 1-4). Inorg. Chem. 1983, 22, 1585–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strianese, M.; Mirra, S.; Bertolasi, V.; Milione, S.; Pellecchia, C. Organometallic Sulfur Complexes: Reactivity of the Hydrogen Sulfide Anion with Cobaloximes. New J. Chem. 2015, 39, 4093–4099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelties, S.; Herrmann, D.; de Bruin, B.; Hartl, F.; Wolf, R. Selective P4 Activation by an Organometallic Nickel(I) Radical: Formation of a Dinuclear Nickel(II) Tetraphosphide and Related Di- and Trichalcogenides. Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 7014–7016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emirdag-Eanes, M.; Ibers, J.A. Synthesis and Characterization of New Oxidopolysulfidovanadates. Inorg. Chem. 2001, 40, 6910–6912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atta, S.; Mandal, A.; Majumdar, A. Generation of Thiosulfate, Selenite, Dithiosulfite, Perthionitrite, Nitric Oxide, and Reactive Chalcogen Species by Binuclear Zinc(II)- Chalcogenolato/-Polychalcogenido Complexes. Inorg. Chem. 2024, 63, 15161–15176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galardon, E.; Daguet, H.; Deschamps, P.; Roussel, P.; Tomas, A.; Artaud, I. Influence of the Diamine on the Reactivity of Thiosulfonato Ruthenium Complexes with Hydrosulfide (HS-). Dalton Trans. 2013, 42, 2817–2821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wern, M.; Hoppe, T.; Becker, J.; Zahn, S.; Mollenhauer, D.; Schindler, S. Sulfur versus Dioxygen: Dinuclear (Trisulfido) Copper Complexes. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2016, 2016, 3384–3388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angersbach-Bludau, F.; Schulz, C.; Schöffel, J.; Burger, P. Syntheses and Electronic Structures of μ-Nitrido Bridged Pyridine, Diimine Iridium Complexes. Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 8735–8738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, R.M.; Cabral, B.J.C.; Simões, J.A.M. Bond-Dissociation Enthalpies in the Gas Phase and in Organic Solvents: Making Ends Meet. Pure Appl. Chem. 2007, 79, 1369–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Brennessel, W.W.; Vicic, D.A. Synthesis and Structure of a Bis-Trifluoromethylthiolate Complex of Nickel. J. Fluor. Chem. 2012, 140, 112–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, C.J.; Burgess, D.R. Kinetic Barriers of H-Atom Transfer Reactions in Alkyl, Allylic, and Oxoallylic Radicals as Calculated by Composite Ab Initio Methods. J. Phys. Chem. 2009, 113, 2473–2482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dénès, F.; Pichowicz, M.; Povie, G.; Renaud, P. Thiyl Radicals in Organic Synthesis. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 2587–2693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Lear, J.M.; Rafferty, S.M.; Fosu, S.C.; Nagib, D.A. Ketyl Radical Reactivity via Atom Transfer Catalysis. Science 2018, 362, 225–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asandei, A.D.; Adebolu, O.I.; Simpson, C.P. Mild-Temperature Mn2(CO)10-Photomediated Controlled Radical Polymerization of Vinylidene Fluoride and Synthesis of Well-Defined Poly(Vinylidene Fluoride) Block Copolymers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 6068–6083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koumura, K.; Satoh, K.; Kamigaito, M. Manganese-Based Controlled/Living Radical Polymerization of Vinyl Acetate, Methyl Acrylate, and Styrene: Highly Active, Versatile, and Photoresponsive Systems. Macromolecules 2008, 41, 7359–7367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mealli, C.; Midollini, S. An Unusual Disulfur-Bridged Nickel Dimer with a Ni2S2 Planar Framework. An Example of Binuclear Coupling Promoted by Transition Metals. Inorg. Chem. 1983, 22, 2785–2786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhuri, U.P.; Powell, D.R.; Houser, R.P. New Examples of μ-η2:η2 -Disulfido Dicopper(II,II) Complexes with Bis(Tetramethylguanidine) Ligands. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2009, 362, 2371–2378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DuBois, M.R.; Jagirdar, B.R.; Dietz, S.; Noll, B.C. Syntheses of Dinuclear Rhenium Complexes with Disulfido and Sulfido Ligands. Organometallics 1997, 16, 294–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreland, A.C.; Rauchfuss, T.B. Synthesis, Structure, and Reactivity of a Remarkable Iron Sulfide: (TACN)2Fe2S6. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998, 120, 9376–9377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minisci, F.; Bernardi, R.; Bertini, F.; Galli, R.; Perchinummo, M. Nucleophilic Character of Alkyl Radicals-VI: A New Convenient Selective Alkylation of Heteroaromatic Bases. Tetrahedron 1971, 27, 3575–3579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minisci, F.; Mondelli, R.; Gardini, G.; Porta, O. Nucleophilic Character of Alkyl Radicals-VII: Substituent Effects on the Homolytic Alkylation of Protonated Heteroaromatic Bases with Methyl, Primary, Secondary and Tertiary Alkyl Radicals. Tetrahedron 1972, 28, 2403–2413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nückel, S.; Burger, P. Transition Metal Complexes with Sterically Demanding Ligands, 3. Synthetic Access to Square-Planar Terdentate Pyridine-Diimine Rhodium(I) and Iridium(I) Methyl Complexes: Successful Detour via Reactive Triflate and Methoxide Complexes. Organometallics 2001, 20, 4345–4359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez, M.V.; Lahoz, F.J.; Lukesová, L.; Miranda, J.R.; Modrego, F.J.; Nguyen, D.H.; Oro, L.A.; Pérez-Torrente, J.J. Hydride Mobility in Trinuclear Sulfido Clusters with the Core [Rh3(µ-H)-(µ3-S)2]: Molecular Models for Hydrogen Migration on Metal Sulfide Hydrotreating Catalysts. Chem. Eur. J. 2011, 17, 8115–8128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manner, V.W.; Markle, T.F.; Freudenthal, J.H.; Roth, J.P.; Mayer, J.M. The First Crystal Structure of a Monomeric Phenoxyl Radical: 2,4,6-Tri-Tert-Butylphenoxyl Radical. Chem. Commun. 2008, 256–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheldrick, G.M. A Short History of SHELX. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. A Found. Crystallogr. 2008, 64, 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolomanov, O.V.; Bourhis, L.J.; Gildea, R.J.; Howard, J.A.K.; Puschmann, H. OLEX2: A Complete Structure Solution, Refinement and Analysis Program. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2009, 42, 339–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, W.S. NMR Studies of Translational Motion: Principles and Applications; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Grimme, S.; Hansen, A.; Ehlert, S.; Mewes, J.-M. R2SCAN-3c: A “Swiss Army Knife” Composite Electronic-Structure Method. J. Chem. Phys. 2021, 154, 064103-01–064103-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perdew, J.P.; Burke, K.; Ernzerhof, M. Generalized Gradient Approximation Made Simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1996, 77, 3865–3868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Truhlar, D.G. Design of Density Functionals That Are Broadly Accurate for Thermochemistry, Thermochemical Kinetics, and Nonbonded Interactions. J. Phys. Chem. 2005, 109, 5656–5667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldeweyher, E.; Ehlert, S.; Hansen, A.; Bannwarth, C.; Grimme, S.; Neugebauer, H.; Spicher, S. A Generally Applicable Atomic-Charge Dependent London Dispersion Correction. J. Chem. Phys. 2019, 150, 154122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kästner, J.; Carr, J.M.; Keal, T.W.; Thiel, W.; Wander, A.; Sherwood, P. DL-FIND: An Open-Source Geometry Optimizer for Atomistic Simulations. J. Phys. Chem. 2009, 113, 11856–11865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.-P.; Song, C. Geometry Optimization Made Simple with Translation and Rotation Coordinates. J. Chem. Phys. 2016, 144, 214108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- University of Minesota. Database of Freq Scale Factors. Available online: https://comp.chem.umn.edu/freqscale/210722_Database_of_Freq_Scale_Factors_v5.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- Nagy, P.R. State-of-the-Art Local Correlation Methods Enable Affordable Gold Standard Quantum Chemistry for up to Hundreds of Atoms. Chem. Sci. 2024, 15, 14556–14584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tikhonov, D.S.; Gordiy, I.; Iakovlev, D.A.; Gorislav, A.A.; Kalinin, M.A.; Nikolenko, S.A.; Malaskeevich, K.M.; Yureva, K.; Matsokin, N.A.; Schnell, M. Harmonic Scale Factors of Fundamental Transitions for Dispersion-Corrected Quantum Chemical Methods. ChemPhysChem 2024, 25, e202400547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mester, D.; Nagy, P.R.; Csóka, J.; Gyevi-Nagy, L.; Szabó, P.B.; Horváth, R.A.; Petrov, K.; Hégely, B.; Ladóczki, B.; Samu, G.; et al. Overview of Developments in the MRCC Program System. J. Phys. Chem. 2025, 129, 2086–2107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Bond | Distance [Å] | Bond | Angles [°] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ir(1)-S(1) | 2.2263(4) | Ir(1)-S(1)-S(2) | 119.87(2) |

| S(1)-S(2) | 2.0850(5) | S(1)-S(2)-S′(1) | 101.47(3) |

| Ir(1)-Npyridine | 1.9307(13) | S-Ir-Nimine | 92.66(4) 110.09(4) |

| Ir(1)-Nimine | 2.0331(13) 2.0329(13) | Nimine-Ir(1)-Nimne | 78.63(6) 78.34(6) |

| Bond | Ir-SH (1) | tBu-IrSH (2) | Ir2S3 (3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nimine-Cimine [Å] | 1.336(0) 1.336(4) | 1.332(2) 1.334(2) | 1.342(2) 1.341(2) |

| Cimine-Cpyridine [Å] | 1.438(0) 1.447(9) | 1.442(2) 1.442(3) | 1.438(2) 1.439(2) |

| Npyridine-Cimine [Å] | 1.380(1) 1.378(9) | 1.377(2) 1.373(2) | 1.378(2) 1.378(2) |

| Δgeo (a) | 0.085 | 0.088 | 0.079 |

| Ir(1)-S(1) [Å] | 2.273(0) | 2.2544(7) | 2.2263(4) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Völker, M.; Marx, T.; Burger, P. Formation and Reversible Cleavage of an Unusual Trisulfide-Bridged Binuclear Pyridine Diimine Iridium Complex. Inorganics 2026, 14, 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/inorganics14010011

Völker M, Marx T, Burger P. Formation and Reversible Cleavage of an Unusual Trisulfide-Bridged Binuclear Pyridine Diimine Iridium Complex. Inorganics. 2026; 14(1):11. https://doi.org/10.3390/inorganics14010011

Chicago/Turabian StyleVölker, Max, Thomas Marx, and Peter Burger. 2026. "Formation and Reversible Cleavage of an Unusual Trisulfide-Bridged Binuclear Pyridine Diimine Iridium Complex" Inorganics 14, no. 1: 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/inorganics14010011

APA StyleVölker, M., Marx, T., & Burger, P. (2026). Formation and Reversible Cleavage of an Unusual Trisulfide-Bridged Binuclear Pyridine Diimine Iridium Complex. Inorganics, 14(1), 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/inorganics14010011