Abstract

To address the low energy conversion efficiency and weak mechanical strength of In2O3 thermoelectric materials for Aiye Processing Equipment, this study systematically investigated the regulatory effects and mechanisms of Ce doping on In2O3’s thermoelectric and mechanical properties via experiments. In2O3 samples with varying Ce contents were prepared, and property-microstructure correlations were analyzed through electrical/thermal transport tests, Vickers hardness measurements, and crystal structure characterization. Results show Ce doping synergistically optimizes In2O3 properties through multiple mechanisms. For thermoelectric performance, Ce4+ regulates carrier concentration and mobility, enhancing electrical conductivity and power factor. Meanwhile, lattice distortion from Ce-In atomic size differences strengthens phonon scattering, reducing lattice and total thermal conductivity. These effects boost the maximum ZT from 0.055 (pure In2O3) to 0.328 at 973 K obtained by x = 0.0065, improving energy conversion efficiency significantly. For mechanical properties, Ce doping enhances Vickers hardness and plastic deformation resistance via solid solution strengthening (lattice distortion hinders dislocations), microstructure densification (reducing vacancies/pores), Ce-O bond strengthening, and defect pinning. This study confirms Ce doping as an effective strategy for simultaneous optimization of In2O3’s thermoelectric and mechanical properties, providing experimental/theoretical support for oxide thermoelectric material development and valuable references for their medium-low temperature energy recovery applications.

1. Introduction

In the process of promoting thermoelectric technology toward industrial large-scale applications for Aiye Processing Equipment, oxide thermoelectric materials have become a key direction to break through the application bottlenecks of traditional thermoelectric materials, supported by both technical characteristics and cost advantages [1,2,3]. The target application scenario of oxide thermoelectric materials—specifically, the waste heat recovery needs in the deep processing of Aiye processing equipment. This research is conducted in collaboration with Aiye processing equipment enterprises. As a traditional medicinal plant, Aiye processing equipment generates waste heat during drying, extraction, and other processing steps. Oxide materials exhibit optimized ZT values and stability, which perfectly match the waste heat characteristics of Aiye processing equipment. Technically, their excellent high-temperature oxidation resistance (capable of stable operation at 500–1000 °C) and chemical stability make them suitable for high-temperature waste heat recovery scenarios such as industrial kilns and gas turbines, solving the problems of easy volatilization and performance degradation of traditional bismuth telluride and lead telluride materials at high temperatures [4,5,6,7,8,9,10]. Moreover, their composition contains no heavy metals, and there is no environmental risk during preparation and disposal, which meets environmental protection requirements. In terms of cost, the core components of oxide materials (such as metal oxides of indium, tin, zinc, etc.) are mostly common industrial raw materials with wide sources and stable prices, avoiding the dependence of traditional thermoelectric materials on scarce tellurium elements and significantly reducing raw material costs [11,12,13,14]. At the same time, they can be prepared through mature industrial processes such as sintering and thin-film deposition, without complex purification procedures, resulting in high production efficiency and low equipment investment, which further controls the industrialization cost. Based on this, oxide thermoelectric materials show broad prospects in fields such as medium-to-high temperature waste heat power generation, aerospace special power supplies, and high-temperature precision temperature control, providing a material solution with performance, environmental protection, and economy for thermoelectric technology to move from the laboratory to practical applications.

Indium oxide (In2O3) is a potential thermoelectric material, and its research status has attracted much attention, especially in terms of electrical conductivity and power factor, where there are some problems to be solved. Indium oxide is an intrinsic n-type semiconductor material with good high-temperature stability and chemical stability, and it is environmentally friendly [15,16]. It has a relatively high carrier mobility and theoretically has the potential to become a thermoelectric material with a high ZT factor. Through means such as doping, such as V doping, Ge doping, etc., the electrical conductivity and power factor can be improved to a certain extent [17,18,19]. For example, V doping can synergistically optimize the thermal and electrical properties of In2O3, and Ge doping can greatly increase the power factor. Despite the above-mentioned advantages, the electrical conductivity and power factor of indium oxide still need to be further improved. The electrical conductivity of pure indium oxide is relatively low, which is one of the key factors limiting its thermoelectric performance. Although doping can introduce additional electrons and increase the carrier concentration, thereby improving the electrical conductivity, it still faces challenges to achieve a significant improvement. For example, when molybdenum (Mo) is doped into In2O3, Mo is soluble in In2O3, but a secondary phase is formed at a higher doping fraction, and Mo is not suitable for improving the thermoelectric performance of the oxide to the required level [20]. In addition, the power factor of indium oxide is not high. The power factor is jointly determined by the Seebeck coefficient and the electrical conductivity. Due to the inverse correlation between the Seebeck coefficient and the electrical conductivity, increasing the electrical conductivity often leads to a decrease in the Seebeck coefficient, making it difficult to effectively improve the power factor. At present, even though there were some improvements in doping and preparation processes, the power factor of indium oxide still cannot meet the requirements of practical applications, and there is still a large gap between its ZT value and that of traditional high-performance thermoelectric materials.

Doping indium oxide (In2O3) thermoelectric materials with cerium (Ce) elements demonstrates multiple innovative advantages in enhancing thermoelectric performance, primarily through electronic structure modulation, microstructural optimization, and functional synergy enhancement. Ce4+ doping introduces new energy levels or defect states, significantly altering the electron distribution in In2O3. The interaction between Ce’s 4f orbitals and In2O3’s conduction band regulates carrier concentration and mobility, forming optimized carrier transport channels. This electronic structure refinement reduces thermal conductivity (κ) while maintaining high electrical conductivity (σ), thereby improving the thermoelectric figure of merit (ZT). For instance, Ce doping suppresses phonon scattering to lower lattice thermal conductivity, while electronic adjustments prevent significant conductivity drops, achieving synergistic thermoelectric optimization. Ce doping induces lattice distortion in In2O3, forming nanoscale defects. These microstructural changes could enhance phonon scattering and further reduce thermal conductivity. Ce doping not only improves thermoelectric properties but also imparts multifunctional characteristics to In2O3. For instance, Ce’s redox activity enhances the material’s adsorption capacity for specific gases, enabling simultaneous thermoelectric power generation and gas sensing. Furthermore, Ce doping improves the chemical stability of In2O3, reducing performance degradation under high-temperature oxidation or reduction conditions, thereby expanding its application scope. This functional synergy provides new insights for developing intelligent devices integrating thermoelectric power generation and sensing.

2. Results and Discussion

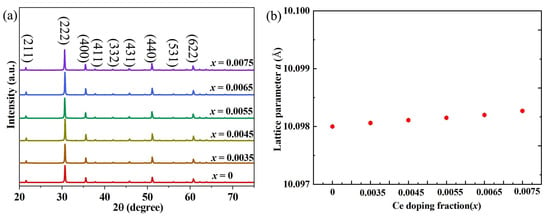

The absence of impurity diffraction peaks in the XRD pattern for In2−xO3Cex (x = 0, 0.0035, 0.0045, 0.0055, 0.0065, 0.0075) as shown in Figure 1 and Table 1 indicates that Ce is dissolved in the In2O3 matrix in a solid solution form, mainly due to the synergy between crystal structure compatibility and the charge balance mechanism. Structurally, In2O3 has a cubic bixbyite structure, while CeO2 (cerium dioxide) normally adopts a cubic fluorite structure. Although their original structures differ, the ionic radius difference between Ce4+ (97.0 pm at coordination number 6) and In3+ (80.0 pm at coordination number 6) is small (~21.2%), and Ce can adapt to the lattice sites of In2O3 through valence adjustment. Ce4+ can substitute In3+ at the 24d or 8b sites in In2O3, avoiding the formation of independent impurity phases caused by lattice site mismatch. The In2O3 lattice inherently contains oxygen vacancies to maintain electrical neutrality. When Ce4+ (+4 valence) substitutes In3+ (+3 valence), each Ce4+ introduces one excess positive charge. The oxygen vacancies (negatively charged) in In2O3 can eliminate charge imbalance through “vacancy compensation” (e.g., 2 Ce4+ substituting 2 In3+, with the excess 2 positive charges compensated by 1 O2− vacancy), without forming new phases for charge balance. The increase in the lattice constant is essentially a lattice contraction effect induced by substitution of Ce-based ions, conforming to Vegard’s Law (the lattice constant of a solid solution increases as the radius of solute ions increases) [21,22]. In2O3 is dominated by In3+ cations; after Ce doping, Ce substitutes In3+. The increase in lattice constant of indium oxide (In2O3) after Ce doping can be elaborated based on three core factors: ionic radius difference, crystal structure compatibility, and lattice distortion effect. In2O3 adopts a body-centered cubic structure (space group Ia-3) with In3+ having an ionic radius of 0.080 nm (coordination number 6). In contrast, the ionic radii of Ce4+ is 97.0 pm, larger than that of In3+. During the doping process, Ce ions form a solid solution by substituting In3+ in the lattice. The larger Ce ions exert a “stretching effect” on the surrounding lattice, directly leading to the expansion of unit cell volume and a subsequent increase in lattice constant. Additionally, the valence state difference between Ce4+ and In3+ induces the formation of oxygen vacancies in the lattice (to maintain charge balance, 1 oxygen vacancy is generated for every 2 Ce4+ ions introduced). The presence of oxygen vacancies weakens the Coulombic attraction between adjacent ions, further promoting lattice relaxation and expansion. This result provides structural support for regulating the thermoelectric properties of the material—lattice contraction can alter carrier transport channels and phonon scattering efficiency, and further verification of their performance correlation requires combination with thermoelectric tests.

Figure 1.

(a) XRD diffraction patterns of indium oxide thermoelectric materials with In2−xO3Cex (x = 0, 0.0035, 0.0045, 0.0055, 0.0065, 0.0075); (b) Effect of Ce doping on the lattice constants of indium oxide.

Table 1.

The refined results of Celref (when the sigma is refined to below 0.0005, the lattice parameters are supposed to be reliable).

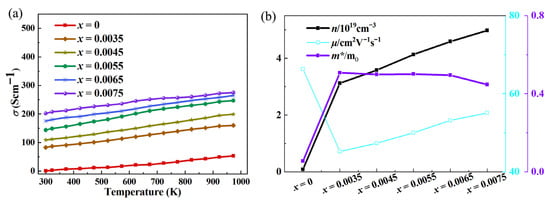

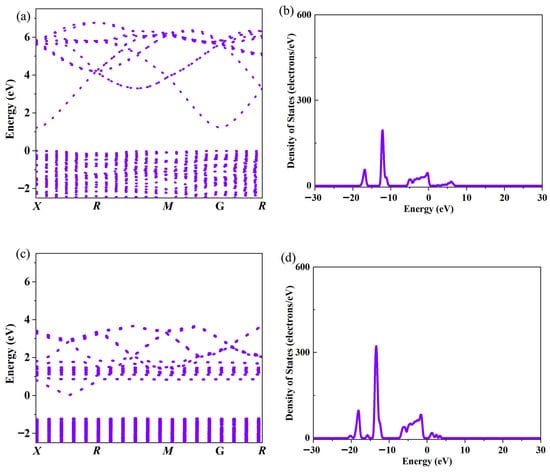

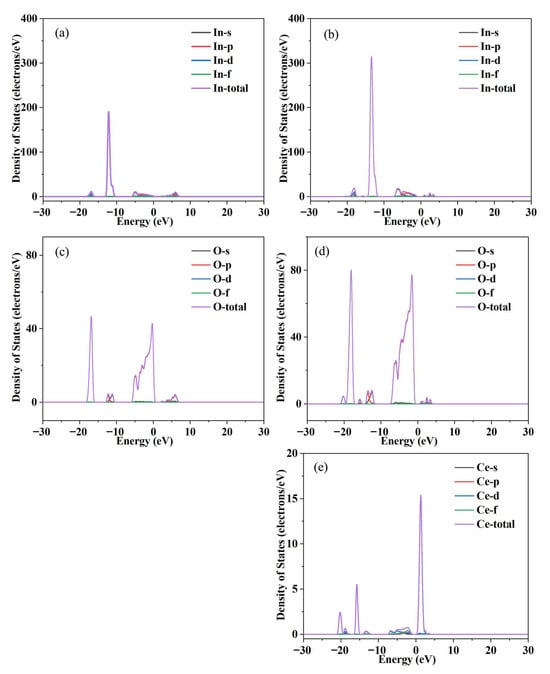

Figure 2 shows the electrical conductivity of Ce-doped In2O3 series with In2−xO3Cex (x = 0, 0.0035, 0.0045, 0.0055, 0.0065, 0.0075) and the electronic transport characteristic parameters (carrier concentration, mobility). In the Ce-doped indium oxide (In2O3) thermoelectric material system, the introduction of Ce breaks the original electrical transport balance of pure In2O3. Although it causes a certain degree of decrease in carrier mobility, the significant increase in carrier concentration eventually becomes the dominant factor, promoting the overall growth of electrical conductivity and providing core support for the optimization of the material’s thermoelectric properties. From the perspective of the mechanism of carrier concentration change, Ce doping achieves the increase in carrier concentration through a dual path of “direct contribution” and “indirect regulation”. Pure In2O3 is a wide-bandgap semiconductor, and its intrinsic carriers mainly rely on oxygen vacancy defects in the lattice. As donor defects, oxygen vacancies introduce energy levels into the bandgap, exciting a small number of free electrons to participate in conduction. Therefore, the carrier supply of pure-phase materials is relatively limited. When Ce is introduced into the In2O3 lattice as a dopant, it first increases the number of carriers through direct action: Ce atoms tend to exist in the form of Ce4+ in the lattice, and there are unpaired electrons in their outer electron configuration. These electrons are weakly bound by the atom and easily break away from the restraint of Ce4+, enter the conduction band of In2O3, transform into freely moving carriers, and directly supplement the conductive carriers for the material. Secondly, Ce doping further increases the carrier concentration through indirect regulation: due to the difference in ionic radius between Ce4+ and In3+ in the In2O3 lattice, the introduction of Ce4+ disrupts the balance of atomic arrangement in the original lattice, causing local lattice stress. To relieve this stress, the lattice spontaneously adjusts the atomic configuration, among which the generation of oxygen vacancies is one of the important adjustment methods. The newly generated oxygen vacancies also have donor characteristics and can provide free electrons to the conduction band again, forming a superposition effect with the carriers directly contributed by Ce4+, and jointly promoting a significant increase in carrier concentration. Ce doping provides carriers for In2O3 through a dual effect, fundamentally solving the problem of insufficient carriers in pure-phase materials and laying the foundation for improved electrical conductivity. Contrary to the increasing trend of carrier concentration, Ce doping causes a decrease in carrier mobility, mainly due to enhanced lattice scattering and intensified impurity interference. Carrier mobility is closely related to lattice integrity: the more regular the lattice and the fewer defects, the higher the mobility; otherwise, it is lower. In the Ce-doped system, the ionic radius difference between Ce4+ and In3+ disrupts the periodic arrangement of the In2O3 lattice, causing local distortion, altering lattice vibration laws, increasing the collision probability between carriers and acoustic phonons, and raising migration resistance. Meanwhile, Ce atoms, as impurities, deflect carrier movement directions via Coulomb force, and oxygen vacancies induced by doping become new scattering centers. The combined effect of multiple scatterings ultimately leads to reduced mobility. However, the final change in electrical conductivity depends on the comprehensive effect of carrier concentration and mobility. Ce doping enables a leapfrog increase in carrier concentration, whose growth rate far exceeds the mild decrease in mobility. According to the electrical conductivity formula σ = neμ, the positive contribution of increased carrier concentration completely offsets the negative impact of reduced mobility, ultimately promoting a significant rise in electrical conductivity. Analyses of band structure, total density of states (DOS), and partial density of states (PDOS) in Figure 3 and Figure 4 show that Ce doping significantly regulates the electronic structure of In2O3. Pure In2O3 exhibits typical semiconductor characteristics, with a distinct band gap between the conduction band and valence band and low DOS near the Fermi level. The valence band is mainly composed of electrons from O’s 2p orbitals, while the conduction band is dominated by electrons from In’s 5s orbitals. The separation of orbital contributions limits electron transition and carrier transport. After Ce doping, the bands near the bottom of the conduction band become dense and converge, helping to increase the effective mass of carriers; the total DOS near the Fermi level rises significantly, providing sufficient energy level channels for carrier excitation and transport. Partial DOS analysis reveals that this change mainly stems from impurity levels introduced by Ce: the 4f orbitals of Ce hybridize with In’s 5s orbitals and O’s 2p orbitals, forming new impurity levels in the band gap of In2O3, which greatly increases the electron DOS in the Fermi level region. Additionally, Ce doping triggers the reconstruction of original orbital contributions, slightly adjusting the DOS distribution of In and O orbitals, further promoting electronic state concentration and improving carrier transport efficiency.

Figure 2.

(a) Effect of Ce doping on electrical conductivity of In2O3 at different temperatures with In2−xO3Cex (x = 0, 0.0035, 0.0045, 0.0055, 0.0065, 0.0075); (b) Characterization results of carrier concentration and mobility.

Figure 3.

(a,c) Band structure and total density of states of In2O3 thermoelectric materials; (b,d) Band structure and total DOS of Ce-doped In2O3 thermoelectric materials.

Figure 4.

(a,c) Calculated partial density of states (PDOS) of In2O3 thermoelectric materials; (b,d,e) Calculated PDOS of Ce-doped In2O3 thermoelectric materials.

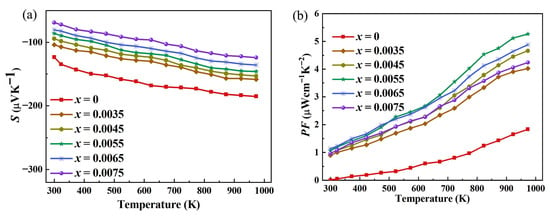

The decrease in absolute value of the Seebeck coefficient after Ce-doped indium oxide thermoelectric materials with In2−xO3Cex (x = 0, 0.0035, 0.0045, 0.0055, 0.0065, 0.0075) is shown in Figure 5a. The Seebeck coefficient (S) is inversely proportional to carrier concentration (n). In Ce-doped indium oxide (In2O3), cerium ions act as electron donors, introducing excess electrons into the conduction band. This increases the carrier concentration significantly. According to the Pisarenko relation, as n rises, the logarithmic term dominates, causing S to decrease. For example, in non-doped semiconductors, low n results in high S due to limited carrier availability for thermal transport. In contrast, Ce doping floods the system with carriers, reducing the “transport entropy” per carrier, which is the physical basis of the Seebeck effect. While Ce doping enhances conductivity (σ) by increasing n, it simultaneously reduces carrier mobility (μ). This occurs because excess carriers interact more frequently with lattice defects and ionized impurities, leading to stronger scattering. The Seebeck coefficient is also influenced by mobility. When μ decreases, the efficiency of energy-selective carrier transport diminishes, further lowering S. For instance, in doped organic thermoelectrics, reduced mobility due to structural disorder similarly suppresses S. Ce doping may alter the band structure of In2O3, introducing additional energy states near the conduction band edge. These states act as scattering centers, reducing the mean free path of carriers and thus μ. Additionally, the increased carrier concentration shifts the Fermi level deeper into the conduction band, narrowing the energy window for thermally activated carriers. This reduces the asymmetry in carrier distribution between hot and cold ends, weakening the Seebeck effect.

Figure 5.

(a) Characterization results of the Seebeck coefficient of Ce-doped In2O3 thermoelectric materials with In2−xO3Cex (x = 0, 0.0035, 0.0045, 0.0055, 0.0065, 0.0075); (b) Characterization results of the power factor.

The power factor (PF = S2σ, where S is the Seebeck coefficient and σ is the electrical conductivity) increased significantly, as shown in Figure 5b. In the Ce-doped indium oxide (In2O3) thermoelectric material system with In2−xO3Cex (x = 0, 0.0035, 0.0045, 0.0055, 0.0065, 0.0075). The core reason for the decrease in the Seebeck coefficient (S) with Ce doping is carrier concentration regulation. Pure In2O3 has few intrinsic defects, low carrier concentration, and large differences in carrier energy distribution, so S remains high. The introduction of Ce3+ provides additional free carriers, significantly increasing the carrier concentration. According to the inherent correlation between S and carrier concentration, the narrowed energy difference of carriers leads to a mild decrease in S (no sharp drop), laying the foundation for power factor (PF) improvement. The substantial enhancement of electrical conductivity (σ) is key to PF growth: Ce3+ increases the number of carriers. Moreover, the atomic radius difference between Ce and In does not exceed the critical threshold, and the optimized doping amount results in mild lattice distortion, causing only slight fluctuations in carrier mobility. The leap in σ far outweighs the decrease in S. Based on PF = S2σ, the positive effect of σ enhancement dominates, ultimately leading to a significant rise in PF. From the specific values, the maximum power factor of pure In2O3 is only 1.83 μWcm−1K−2 (973 K), while after optimized Ce doping, the maximum power factor of the material increases to 5.27 μWcm−1K−2 (973 K), which is nearly 3 times higher than that of the pure sample. This result fully proves the effectiveness of Ce doping in optimizing the electrical transport properties of In2O3 and improving the power factor, and also provides key support for the subsequent improvement of the thermoelectric figure of merit ZT.

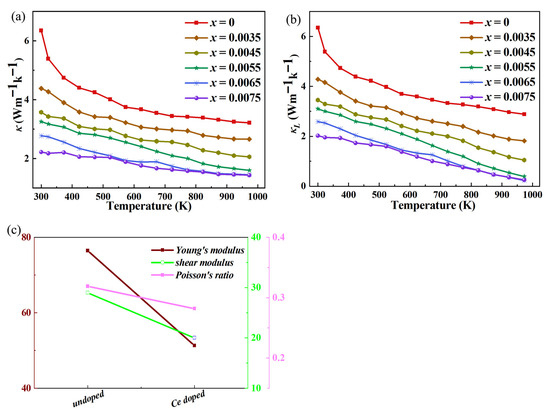

The thermal conductivity analysis of Ce-doped indium oxide thermoelectric materials with In2−xO3Cex (x = 0, 0.0035, 0.0045, 0.0055, 0.0065, 0.0075) is shown in Figure 6. Thermal conductivity (κ) in thermoelectric materials comprises electronic thermal conductivity (κe) and lattice thermal conductivity (κL). For In2O3-based materials, κL dominates due to low carrier concentration. Ce doping introduces structural modifications that disrupt phonon transport, reducing κL while maintaining κe at a manageable level. The drastic decrease in thermal conductivity of In2O3 with <1% Ce doping (without secondary phases) stems from the intensified point-defect phonon scattering mechanism, analogous to the doping strategy in TiCoSb alloys reported in the references [23,24,25]. In2O3 adopts a body-centered cubic structure, where low-concentration Ce4+ substitute In3+ via substitutional solid solution. Significant differences in atomic mass and ionic radius between Ce and In induce intense mass fluctuations and strain-field variations in the lattice. These point defects efficiently scatter phonons across different frequencies: high-frequency phonons are directly scattered by atomic mass discrepancies, while low-frequency phonons are hindered by strain-field distortion, drastically reducing phonon relaxation time. Additionally, valence state differences between Ce and In trigger the formation of a small number of oxygen vacancies, further enhancing lattice disorder and synergistically strengthening phonon scattering. The absence of secondary phases indicates uniform solid solution formation of Ce, avoiding defect agglomeration-induced scattering saturation. Thus, even low-concentration doping significantly suppresses lattice thermal conductivity, consistent with the Debye-Callaway model, where point-defect scattering dominates heat transport inhibition. Ce4+ substitutes In3+ in the In2O3 lattice, synergistically reducing κ through multiple mechanisms. On one hand, the mass contrast between Ce4+ and In3+ triggers Rayleigh scattering, efficiently scattering high-frequency phonons and shortening their mean free path (MFP). Ionic radius mismatch (Ce4+ 0.087 nm vs. In3+ 0.080 nm) induces local lattice strain and dislocations, acting as scattering centers for low-frequency phonons. On the other hand, valence state difference induces oxygen vacancies (Vo••), Ce-In antisite defects, forming a full-frequency phonon scattering network: low-frequency phonons are scattered by defect clusters and grain boundary anomalies, while high-frequency phonons are hindered by point defects, significantly impairing lattice thermal conductivity (κL)—which accounts for over 70% of the total κ in undoped In2O3 and dominates the κ reduction. Carrier transport exerts a weak regulatory effect on electronic thermal conductivity (κe): the increase in carrier concentration (n) theoretically enhances κe, but this is offset by reduced mobility (μ) caused by lattice distortion, with the κe increase far smaller than the κL decrease. Additionally, Ce doping reduces the Young’s modulus of In2O3, weakening interatomic bonding, lowering phonon group velocity, and increasing scattering probability, further suppressing κL. This synergy breaks the traditional trade-off between electrical and thermal transport, improving electrical conductivity while reducing κ, laying the foundation for optimizing the ZT value.

Figure 6.

(a) Thermal conductivity test results of Ce-doped modified In2O3; (b) Calculated results of lattice thermal conductivity; (c) Characterization results of elastic constants before and after doping.

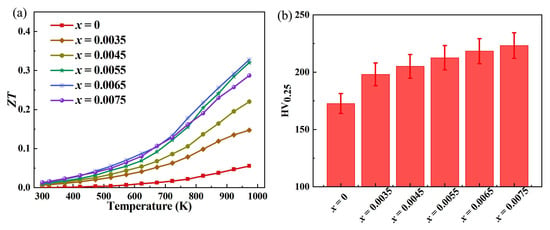

The significant improvement of the ZT value of Ce-doped indium oxide (In2O3) thermoelectric materials with In2−xO3Cex (x = 0, 0.0035, 0.0045, 0.0055, 0.0065, 0.0075) as shown in Figure 7a stems from the synergistic effect between the optimization of electrical transport properties and the suppression of thermal transport properties. In terms of electrical transport properties, Ce doping effectively regulates the carrier concentration and mobility of indium oxide. After the introduction of Ce3+ ions into the In2O3 lattice, doped energy levels are formed with In3+, which significantly increases the carrier supply. Meanwhile, the degree of lattice distortion is controlled within a reasonable range, without causing severe scattering of carrier migration, ultimately achieving a significant improvement in electrical conductivity. The synergistic effect between the optimization of electrical conductivity and the Seebeck coefficient further promotes the enhancement of the power factor—a key parameter reflecting the material’s ability to transmit electrical energy. Its enhancement directly lays the core foundation for the improvement of the ZT value. In terms of thermal transport properties, Ce doping achieves the simultaneous reduction of total thermal conductivity and lattice thermal conductivity through multiple mechanisms. On one hand, the differences in atomic weight and ionic radius between Ce atoms and In atoms form effective scattering centers in the lattice, which significantly enhance the scattering effect on phonons and inhibit the transmission of lattice thermal conductivity. On the other hand, the trace defects and lattice distortions introduced by doping further hinder the long-range transport of phonons, leading to a substantial reduction in lattice thermal conductivity. The total thermal conductivity consists of lattice thermal conductivity and electronic thermal conductivity. Under the premise that the electronic thermal conductivity does not increase significantly, the reduction in lattice thermal conductivity directly results in the decrease in total thermal conductivity. Under the synergistic effect of the increase in electrical conductivity and power factor, as well as the decrease in total thermal conductivity and lattice thermal conductivity, the ZT value of Ce-doped indium oxide thermoelectric materials has achieved a leapfrog improvement. The ZT value of undoped pure indium oxide thermoelectric materials is only 0.055, while after optimized Ce doping, the maximum ZT value of the material increases to 0.328, which is nearly 5 times higher than that of the undoped sample. This demonstrates an excellent thermoelectric performance optimization effect, providing important performance support for the practical application of indium oxide-based thermoelectric materials.

Figure 7.

(a) Dimensionless thermoelectric figure of merit of In2O3 with In2−xO3Cex (x = 0, 0.0035, 0.0045, 0.0055, 0.0065, 0.0075); (b) Corresponding variation in Vickers hardness.

The significant improvement in Vickers hardness of Ce-doped indium oxide (In2O3) thermoelectric materials with In2−xO3Cex (x = 0, 0.0035, 0.0045, 0.0055, 0.0065, 0.0075) as shown in Figure 7b is essentially a comprehensive result of multiple structural and performance optimizations caused by the interaction between the dopant element and the matrix lattice. The specific analysis can be carried out from the following aspects. The solid solution strengthening effect induced by lattice distortion is one of the core mechanisms for hardness improvement. Indium oxide has a cubic bixbyite structure, where In3+ ions occupy specific interstitial sites in the lattice, forming a relatively stable crystal structure [26,27]. When Ce is introduced as a dopant, the ionic radius of Ce4+ differs significantly from that of In3+. This size mismatch disrupts the periodic arrangement of the original lattice, leading to local lattice distortion. Lattice distortion generates an internal stress field, which can effectively hinder the movement of dislocations inside the material. Dislocation movement is the main cause of plastic deformation in materials; hindered dislocation movement means that the material requires greater external force to deform, directly manifesting as an increase in Vickers hardness. Meanwhile, the difference in electron configuration between Ce4+ and In3+ also changes the electron cloud distribution in the lattice, further enhancing the interatomic bonding force, providing additional structural stability to the lattice, and assisting in improving the material’s deformation resistance. In addition, the chemical interaction between the dopant element and the matrix enhances the overall stability of the lattice. Ce has high chemical activity, and during the formation of a solid solution with indium oxide, in addition to causing lattice distortion, it may also form stronger chemical bonds with oxygen in the matrix. The stability of the indium oxide crystal structure depends on the bonding strength of In-O bonds, and the bond energy of Ce-O bonds is higher than that of In-O bonds. The introduction of Ce will partially replace In to combine with O, forming a stronger chemical bond network. This increase in chemical bond strength enhances the damage resistance of the entire lattice. When the material is subjected to the indenter load in the Vickers hardness test, a larger external force is required to break this strengthened chemical bond network, which in turn manifests as a significant increase in hardness.

3. Experimental Section

High-purity indium oxide (In2O3) and cerium dioxide (CeO2) powders were used as precursor materials for the fabrication of Ce-doped In2O3. Prior to mixing, both powders underwent pre-treatment to ensure uniform particle distribution and remove surface contaminants. The desired molar ratios of CeO2 to In2O3, corresponding to specific Ce doping levels with In2−xO3Cex (x = 0, 0.0035, 0.0045, 0.0055, 0.0065, 0.0075), were accurately weighed and combined. The powder mixture, along with hardened steel grinding media, was sealed in a steel milling jar (QM-2SP12, Nanjing University Instrument Factory, Nanjing, China) under an argon atmosphere to prevent moisture absorption and oxidation during processing. Put it into a muffle furnace and calcine at the high temperature of 1473 K for 8 h. Crush the obtained sample and then perform discharge plasma sintering at the temperature of 1273 K with 30 min of insulation and a pressure of 60 MPa. A diffractometer is used to characterize the phase structure of the material, and the equipment is Bruker AXS D8 diffractometer (Bruker AXS GmbH, Karlsruhe, Germany). The diffraction analysis adopts Cu and rays with a wavelength of 1.5406 Å. Nickel plates were used as the substrate on the XRD sample stage with a diffraction angle range of 10–80°, a step size of 0.02°, a tube current of 20 mA, and a tube voltage of 40 kV. The electrical conductivity and Seebeck coefficient were tested using an electrical performance tester (ZEM-3, ULVAC KIKO, Tokyo, Japan). The carrier concentration and mobility at room temperature were measured by the van der Pauw method using the Hall-effect measurement system (HMS-5500, Ekopia, Seoul, Republic of Korea). The volume density was measured by the Archimedes method. The flash thermal conductivity tester used was LFA457 (Netzsch, Berlin, Germany), for thermal conductivity testing. And the specific heat capacity (Cp) was determined by differential scanning calorimetry (DSC 404C, Netzsch, Berlin, Germany) under an inert atmosphere. The relative densities were 97.13%, 97.19%, 97.28%, 97.22%, 97.29%, and 97.21% for x = 0, 0.0035, 0.0045, 0.0055, 0.0065, and 0.0075, respectively. All the specimens were polished with two parallel planes, and the plane close to the central part was utilized for Vickers hardness (HV) measurement, which was conducted on HV-10008 with a load of 25 g and a loading time of 15 s. Every sample was tested with 5 data points, and the average HV was used for characterizing mechanical properties. The uncertainty of the Vickers hardness is estimated to be within 5%. The uncertainty of the Seebeck coefficient and electrical conductivity measurements was 5%. The uncertainty of the thermal conductivity is estimated to be within 8%, considering the uncertainties regarding the thermal diffusion coefficient, specific heat, and density. The combined uncertainty for all measurements involved in the calculation of ZT is less than 15%. The density functional calculation used here is the CASTEP software package in the materials studio software 8.0, and the constructed 2 × 2 × 1 unit cell is calculated. The cut-off energy in plane wave expansion is 550 eV; the total energy is converged to less than 2.0 × 10−5 eV/atom. The maximum stress and maximum force were converged to less than 0.05 GPa and 0.3 eV/nm. The tolerance in the self-consistent field (SCF) calculation was set to 10−6 eV/atom. The specific experimental parameters, including temperature, pressure, and holding time, can be found in previous research [28].

4. Conclusions

This study systematically investigated the regulatory effect of Ce doping on the thermoelectric and mechanical properties of indium oxide (In2O3) thermoelectric materials. Through the analysis of the material’s electrical transport, thermal transport, and Vickers hardness, the following core conclusions are drawn. Firstly, Ce doping can significantly optimize the thermoelectric performance of indium oxide and achieve a leapfrog improvement in the thermoelectric figure of merit ZT. After the introduction of Ce4+ ions, the electrical conductivity of the material is improved by regulating the carrier concentration and mobility, thereby enhancing the power factor. At the same time, the size difference between Ce and In atoms and the lattice distortion effect can strengthen the scattering of phonons, effectively reducing the lattice thermal conductivity and total thermal conductivity. Under the synergistic effect of the optimization of electrical transport properties and the suppression of thermal transport properties, the maximum ZT value of indium oxide is significantly increased from 0.055 of the pure phase material to 0.328, proving that Ce doping is an effective strategy to improve the thermoelectric energy conversion efficiency of indium oxide. Secondly, Ce doping simultaneously improves the mechanical properties of indium oxide, especially as reflected in the significant enhancement of Vickers hardness. This improvement stems from the synergistic effect of multiple mechanisms: the ionic size mismatch between Ce4+ and In3+ causes lattice distortion, which hinders dislocation movement through the solid solution strengthening effect; the “lattice filling” effect of Ce reduces vacancy and pore defects, promoting the densification of the microstructure; at the same time, the high bond energy of Ce-O bonds enhances the lattice chemical stability, and the crystal defects by Ce atoms further optimize the resistance to plastic deformation. The combined effect of multiple mechanisms greatly improves the material’s ability to resist local deformation, providing a guarantee for its structural stability in practical applications. Ce doping can simultaneously achieve the synergistic optimization of “thermoelectric performance-mechanical performance” of indium oxide thermoelectric materials. It not only solves the problems of low ZT value and insufficient energy conversion efficiency of pure indium oxide but also makes up for the defect of weak mechanical strength. This study provides a theoretical basis and technical support for the performance regulation of indium oxide-based thermoelectric materials and also provides a reference direction for the doping modification research of other oxide thermoelectric materials, which is of great significance for promoting the practical application of oxide thermoelectric materials in medium-low temperature energy recovery and other fields.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.Z. (Jie Zhang), B.F., Z.Y. (Zhengxiang Yang), S.Z., J.Z. (Junjie Zhang), J.L. and T.T.; Methodology, Z.Y. (Zhengxiang Yang) and T.T.; Software, B.F., Y.Z., Z.Y. (Zhiwen Yang), W.L., T.T. and S.Y.; Validation, S.Z., Y.Z., Z.Y. (Zhiwen Yang), W.L., T.T. and S.Y.; Formal analysis, S.Z., J.Z. (Junjie Zhang), Z.Y. (Zhiwen Yang) and S.Y.; Investigation, J.Z. (Jie Zhang), B.F., Z.Y. (Zhengxiang Yang), J.L., Y.Z. and W.L.; Resources, J.Z. (Jie Zhang) and B.F.; Data curation, R.R.; Writing—original draft, J.Z. (Jie Zhang) and J.L.; Writing—review and editing, J.Z. (Jie Zhang) and J.L.; Visualization, J.Z. (Junjie Zhang), J.L., X.Z., T.X. and R.R.; Supervision, J.L., X.Z., T.X. and R.R.; Project administration, J.Z. (Jie Zhang), J.L., X.Z., T.X. and R.R.; Funding acquisition, J.L., X.Z., T.X. and R.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The work is supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Hubei Province (2021CFB009), Wuhan Donghu college Youth Fund Project(2025dhzk001), the guiding project of Hubei Province in 2022 (B2022313), the Double Hundred Project of Hubei University of Science and Technology in 2023, the Project of Hubei Engineering University of Teaching Research (Grant No. JY2024032), Ministry of Education University-Industry Cooperation Collaborative Education Project (2409025501), College Students, Innovation and Entrepreneurship Training Program (DC2024031, DC2024032).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Bo Feng was employed by the companies Hubei Xiangcheng Intelligent Electromechanical Research Institute Co., Ltd., Hubei MAGNIFICENT New Material Technology Co., Ltd. and Jiangsu MAGNIFICENT New Material Technology Co., Ltd. Authors Tongqiang Xiong and Zhiwen Yang were employed by the companies Hubei Xiangcheng Intelligent Electromechanical Research Institute Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Jan, R.; Fayaz, M.; Ayoub, N.; Islam, I.; Ghosh, S.; Rubab, S.; Khandy, S.A. Oxide thermoelectric materials: A review of emerging strategies for efficient waste heat recovery. J. Power Sources 2025, 654, 237806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baskaran, P.; Rajasekar, M. Recent trends and future perspectives of thermoelectric materials and their ap-plications. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 21706–21744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Z.; Zheng, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, S.; Liu, S.; Zhan, S.; Wang, L.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, L.-D. Realizing BiCuSeO-based thermoelectric device for ultrahigh carrier mobility through texturation. Nano Energy 2024, 126, 109649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witting, I.T.; Chasapis, T.C.; Ricci, F.; Peters, M.; Heinz, N.A.; Hautier, G.; Snyder, G.J. The thermoelectric properties of bismuth telluride. Adv. Electron. Mater. 2019, 5, 1800904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Li, Z.; Liu, W.; Zhang, Q.; Uher, C. A comprehensive review on Bi2Te3-based thin films: Thermoelectrics and beyond. Interdiscip. Mater. 2022, 1, 88–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, J.; Cai, B.; Zhuang, H.L.; Li, J.-F. Bi2Te3-based applied thermoelectric materials: Research advances and new challenges. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2020, 7, 1856–1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauerschnig, P.; Jood, P.; Ohta, M. Challenges and Progress in Contact Development for PbTe-based Thermoelectrics. ChemNanoMat 2023, 9, e202200560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.Z.; Cai, S.; Hao, S.; Bailey, T.P.; Luo, Y.; Luo, W.; Yu, Y.; Uher, C.; Wolverton, C.; Dravid, V.P.; et al. Extraordinary role of Zn in enhancing thermoelectric performance of Ga-doped n-type PbTe. Energy Environ. Sci. 2022, 15, 368–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.D.; He, J.; Berardan, D.; Lin, Y.; Li, J.-F.; Nanc, C.-W.; Dragoe, N. BiCuSeO oxyselenides: New promising thermoelectric materials. Energy Environ. Sci. 2014, 7, 2900–2924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Feng, B.; Yang, S.; Ruan, R.; Zhang, R.; Xiong, T.; Xu, B.; Zheng, Z.; Zhou, G.; Zhang, Y.; et al. An Updated Review of BiCuSeO-Based Thermoelectric Materials. Micromachines 2025, 16, 703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulaiman, S.; Izman, S.; Uday, M.B.; Omar, M.F. Review on grain size effects on thermal conductivity in ZnO thermoelectric materials. RSC Adv. 2022, 12, 5428–5438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sulaiman, S.; Sudin, I.; Al-Naib, U.M.B.; Omar, M.F. Review of the nanostructuring and doping strategies for high-performance ZnO thermoelectric materials. Crystals 2022, 12, 1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohtaki, M.; Ogura, D.; Eguchi, K.; Arai, H. High-temperature thermoelectric properties of In2O3-based mixed oxides and their applicability to thermoelectric power generation. J. Mater. Chem. 1994, 4, 653–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korotcenkov, G.; Brinzari, V.; Ham, M.H. In2O3-based thermoelectric materials: The state of the art and the role of surface state in the improvement of the efficiency of thermoelectric conversion. Crystals 2018, 8, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bérardan, D.; Guilmeau, E.; Maignan, A.; Raveau, B. In2O3:Ge, a promising n-type thermoelectric oxide composite. Solid State Commun. 2008, 146, 97–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, J.L.; Liu, Y.; Lin, Y.H.; Nan, C.-W.; Cai, Q.; Yang, X. Enhanced thermoelectric performance of In2O3-based ceramics via nanostructuring and point defect engineering. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 7783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.; Hussain, M.; Zhou, Z.; Liu, R.; Lin, Y.-H.; Nan, C.-W. Thermoelectric performance enhancement of vanadium doped n-type In2O3 ceramics via carrier engineering and phonon suppression. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2019, 3, 1552–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Combe, E.; Guilmeau, E.; Savary, E.; Marinel, S.; Cloots, R.; Funahashi, R.; Boschini, F. Microwave sintering of Ge-doped In2O3 thermoelectric ceramics prepared by slip casting process. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2015, 35, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Chen, L.; Ning, S.; Zhao, X.; Deng, S.; Qi, N.; Ren, F.; Chen, Z.; Tang, J. Extremely low thermal conductivity and enhanced thermoelectric performance of porous Gallium-doped In2O3. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2021, 4, 12943–12953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klich, W.; Ohtaki, M. Thermoelectric properties of Mo-doped bulk In2O3 and prediction of its maximum ZT. Ceram. Int. 2021, 47, 18116–18121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magomedov, M.N. On deviations from Vegard’s law at increasing pressure in alloys. Inorg. Mater. 2020, 56, 903–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Xu, J.; Liu, G.Q.; Shao, H.; Tan, X.; Liu, Z.; Xu, J.; Jiang, H.; Jiang, J. Enhanced thermopower in rock-salt SnTe–CdTe from band convergence. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 32189–32192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, A.K.; Jain, S.; Johari, K.K.; Candolfi, C.; Lenoir, B.; Walia, S.; Dhakate, S.R.; Gahtori, B. Approaching the minimum lattice thermal conductivity in TiCoSb half-Heusler alloys by intensified point-defect phonon scattering. Mater. Adv. 2023, 4, 6655–6664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, A.K.; Johari, K.K.; Dubey, P.; Candolfi, C.; Lenoir, B.; Walia, S.; Dhakate, S.; Gahtori, B. Coupling of electronic transport and defect engineering substantially enhances the thermoelectric performance of p-type TiCoSb HH alloy. J. Alloy. Compd. 2023, 947, 169416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, A.K.; Johari, K.K.; Dubey, P.; Sharma, D.K.; Kumar, S.; Dhakate, S.R.; Candolfi, C.; Lenoir, B.; Gahtori, B. Realization of band convergence in p-Type TiCoSb half-heusler alloys significantly enhances the thermoelectric performance. ACS Appl. Mater. Inter. 2022, 15, 942–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, J.; Linda, A.; Sadhasivam, M.; Pradeep, K.; Gurao, N.P.; Biswas, K. The effect of Al addition on solid solution strengthening in CoCrFeMnNi: Experiment and modelling. Acta Mater. 2022, 238, 118208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walbrühl, M.; Linder, D.; Ågren, J.; Borgenstam, A. Modelling of solid solution strengthening in multicomponent alloys. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2017, 700, 301–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Luo, X.; She, X.; An, Q.; Peng, Y.; Cai, G.; Liu, Y.; Tang, Y.; Feng, B. Study on the physical mechanism of thermoelectric transport on the properties of ZnO ceramics. Res. Phys. 2023, 54, 107072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).