Abstract

A hybrid graphene-VO2 reconfigurable terahertz metamaterial absorber is proposed for broadband radar cross-section (RCS) reduction and high-performance sensing. The designed structure leverages the phase transition property of VO2 and the electrostatic tunability of graphene to achieve dynamic switching between ultra-broadband and narrowband absorption states. When VO2 is in the metallic state and graphene is unbiased, the absorber exhibits over 90% absorption across 0.82~3.50 THz, corresponding to a relative bandwidth of 124%. In the narrowband mode, with VO2 in the insulating state and graphene biased (Ef = 1 eV), a sharp absorption peak exceeding 60% is achieved at 1.48 THz. The symmetrical design ensures polarization insensitivity and wide-angle stability. Applications in broadband RCS reduction higher than 10 dB and refractive index sensing with a sensitivity of 24.86 GHz/RIU are demonstrated, surpassing conventional terahertz sensors. This work provides a promising platform for adaptive terahertz stealth and sensing systems.

1. Introduction

Terahertz technology, operating within the 0.1–10 THz frequency range [1,2], has emerged as a critical frontier in modern applied physics and engineering due to its unique potential in advanced communication systems [3], high-resolution imaging [4], and nondestructive testing [5]. The efficient manipulation of terahertz waves, however, relies heavily on high-performance functional devices, among which metamaterial absorbers have attracted significant attention for their ability to achieve near-perfect absorption through subwavelength structural design [6,7,8]. Traditional metamaterial absorbers exhibit fixed functionalities once fabricated, which significantly limits their application scenarios [9,10]. This inherent constraint arises from the passive nature of conventional designs, where the electromagnetic response remains unalterable post-production. Such rigidity hinders adaptability in dynamic environments, particularly in emerging fields like terahertz communications and radar stealth systems that demand real-time reconfigurability [11,12]. This inherent limitation has spurred growing interest in developing tunable absorbers by incorporating active materials like vanadium dioxide (VO2) and graphene.

Recent research has demonstrated the feasibility of using the phase transition properties of VO2 to switch the operating state of absorbers [13,14]. For example, VO2 can reversibly transition from an insulating to a metallic state around 341 K, enabling the device functionality to shift between broadband and narrowband absorption [9]. Simultaneously, graphene offers an additional degree of freedom for dynamic tuning through electrostatic modulation of its Fermi energy level [15]. Zhang et al. employed the VO2 to propose a functionally switchable metamaterial absorber. When VO2 is in the metallic state, the device achieves perfect single-frequency absorption with an absorptivity of 1 at 2.5 THz [16]. Chen et al. propose a VO2–graphene metamaterial absorber that achieves switchable broadband (>95%, 2.85–10 THz) and narrowband (>99.5%, 2.3 THz) absorption via phase transition and Fermi energy tuning [17]. Despite these advances, most reported designs focused on switching between different absorption states or integrating additional functions like polarization conversion, while systematic research dedicated to achieving effective RCS reduction through deliberate bandwidth reconfiguration remains relatively scarce [18,19]. There is a clear need for device architectures that can seamlessly combine large tunable bandwidth, high absorption rate, and polarization insensitivity to meet the demanding requirements of terahertz stealth applications. However, current research predominantly concentrates on high-frequency bands, with low-frequency studies posing significant challenges and remaining scarcely reported.

To address this challenge, a bandwidth-reconfigurable THz metamaterial absorber based on a hybrid graphene–VO2 structure is proposed, specifically designed for Radar Cross-Section (RCS) reduction. This design leverages the complementary advantages of both materials: the phase transition property of VO2 provides a robust mechanism for coarse bandwidth switching, while the tunable conductivity of graphene enables fine, continuous adjustment of the absorption performance. The architecture ensures excellent impedance matching over a wide frequency range, achieving absorption rates exceeding 95% across a tunable bandwidth. Furthermore, the symmetrical design confers insensitivity to the polarization angle of incident waves and maintains high performance under a wide range of incident angles, which are critical for practical deployment. This work presents a viable path toward high-performance THz stealth materials and advances the design paradigm for dynamically reconfigurable metamaterial devices.

2. Structure Design and Material

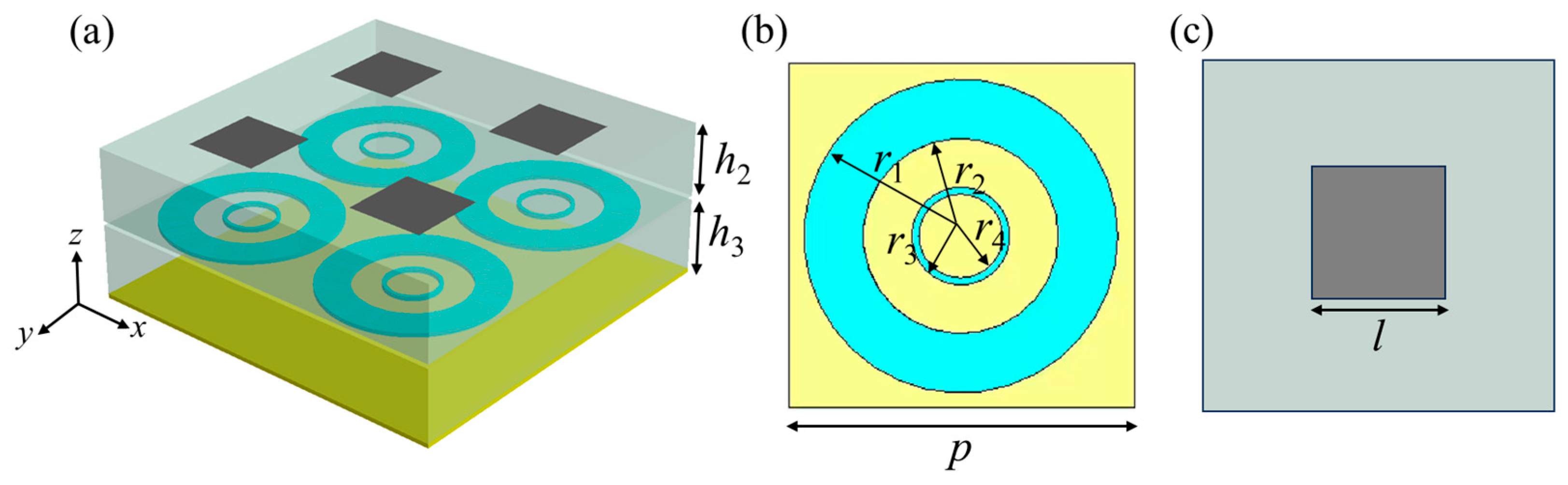

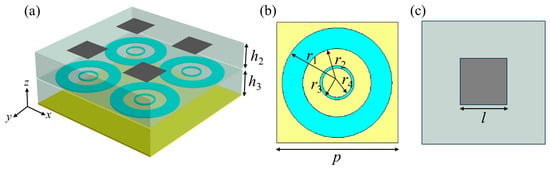

The designed metamaterial absorber features a multilayer configuration, as depicted in Figure 1. Each unit cell is composed of a patterned graphene square sheet, a polyimide dielectric spacer, a double-ring VO2 layer, and a gold reflective substrate. The structure is arranged periodically in the x-y plane with a lattice constant of p = 50 μm. The gold backplane, with a thickness of h1 = 1 μm, serves as a perfect reflector for preventing transmission of THz waves. The dielectric spacers have thicknesses of h2 = 17.4 μm (between VO2 and graphene) and h3 = 17.4 μm (above gold) due to its negligible losses in the THz range with a relative permittivity of ε = 3.5 [20]. The VO2 layer has a thickness of h4 = 1 μm. It is patterned into a double-ring structure with an outer ring defined by radii of r1 = 22.5 μm and r2 = 14 μm, and an inner ring defined by r3 = 11 μm and r4 = 7.5 μm. The top graphene element is a graphene square sheet with a length of l = 20 μm and a thickness of h5 = 1 nm.

Figure 1.

(a) The schematic of the proposed metamaterial absorber. (b) x-y plane of VO2 layer. (c) x-y plane of graphene layer. (The thickness of gold backplane, VO2 layer, and graphene square are h1 = 1 μm, h4 = 1 μm, and h5 = 1 nm).

The surface conductivity of graphene in the THz regime is dominated by intra-band contributions, which can be described by a Kubo formalism. The frequency-dependent conductivity σg(ω) is expressed as follows [21,22]:

where T = 300 K is the ambient temperature, kB is the Boltzmann constant, e is the electron charge, τ = 0.2 ps denotes the electron–phonon relaxation time, ω is the angular frequency of incident THz waves, ħ is the reduced Planck constant, and Ef represents the Fermi level, which can be tuned via electrostatic gating. In the THz regime, the intra-band contribution dominates, allowing the inter-band term to be neglected. Thus, the Kubo formula can be simplified into a Drude-like model [23]:

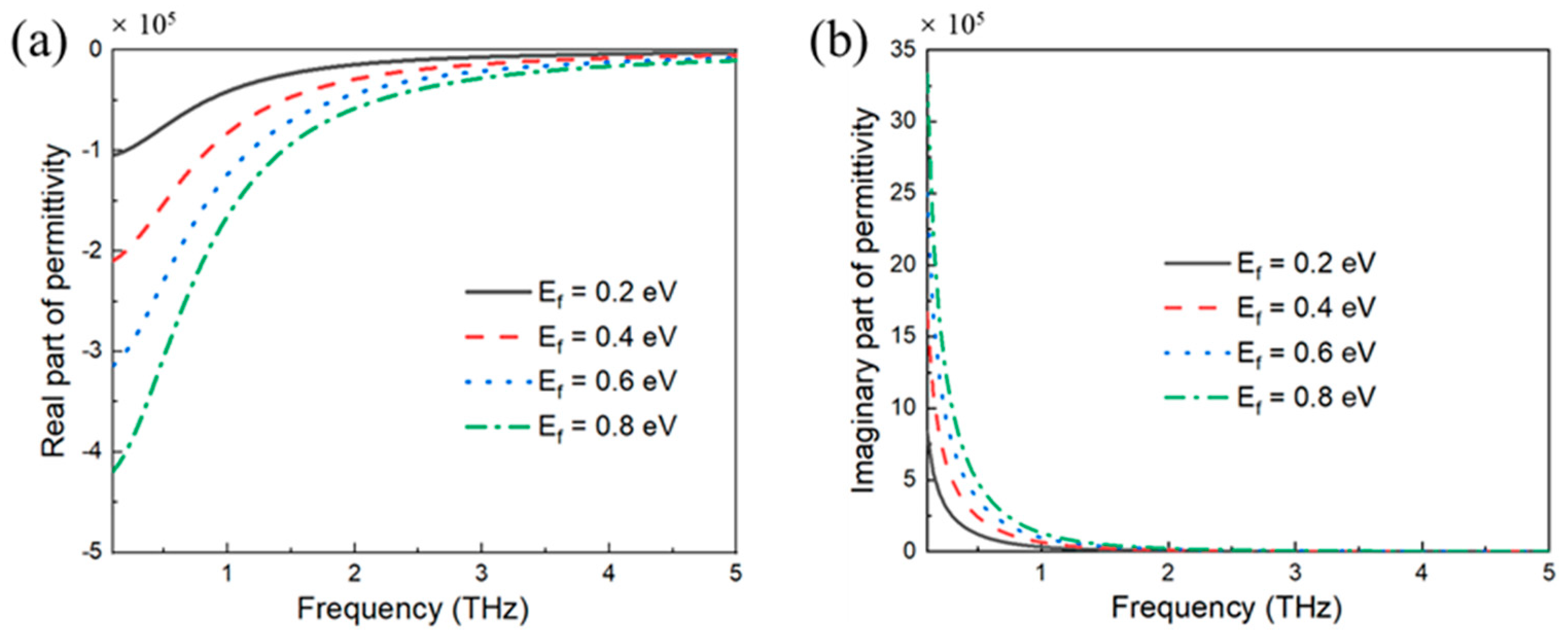

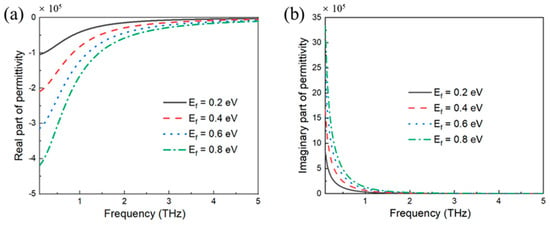

The simplified Drude-like model from Equation (1) captures the electrostatic tunability of graphene, allowing real-time adjustment of absorption properties by varying the chemical potential Ef. Therefore, the corresponding relative permittivity can be derived from the conductivity. The real and imaginary parts of graphene’s conductivity in the THz range, as shown in Figure 2, are effectively modulated by the Ef. An increase in Ef substantially enhances the conductivity, especially in the real part, underscoring its crucial role in controlling THz wave interaction and loss.

Figure 2.

The relative permittivity of graphene in the THz range. (a) Real part; (b) imaginary part.

As for the VO2, another tunable material, it exhibits a reversible insulator-to-metal transition (IMT) near 341 K, which dramatically alters its dielectric properties. The Drude model accurately describes its frequency-dependent permittivity in the THz range [24,25]:

The plasma frequency ωp is a conductivity-dependent item:

where ε∞ indicates the high-frequency dielectric constant (ε∞ = 12 in THz range), σ is the conductivity of VO2 transitioning from 200 S/m (insulator) to 2 × 105 S/m (metallic), σ0 is the reference conductivity of 3 × 105 S/m, ωp0 reparents the reference plasma frequency of 1.4 × 1015 rad/s, and γ is the collision frequency of 5.57 × 1013 rad/s.

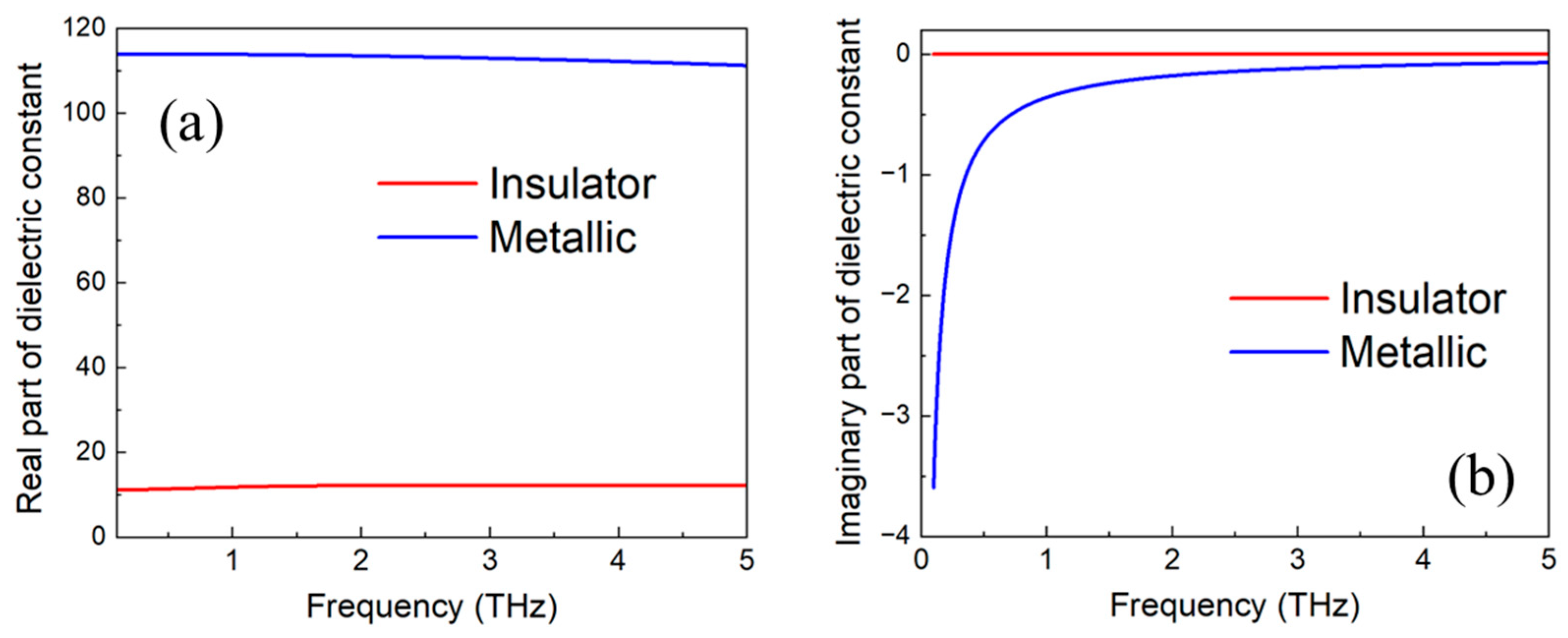

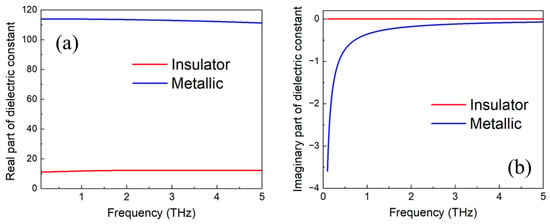

According to Equations (3) and (4), the temperature-dependent dielectric constant enables coarse thermal switching between absorption states, as evidenced by the phase transition behavior shown in Figure 3. It can be observed that the insulating phase of VO2 has a high real part and negligible imaginary part, while the metallic phase of VO2 exhibits a lower real part and significant imaginary part, indicating higher loss.

Figure 3.

The dielectric constant of VO2 in the THz range. (a) Real part and (b) imaginary part at 1.0 THz.

It should be noted that the phase transition of VO2 is thermally induced, typically achieved via localized micro-heaters or global substrate heating, with a transition temperature of 341 K that is experimentally feasible using integrated Pt microheaters or Peltier elements. In contrast, the Fermi level of graphene is electrically modulated via electrostatic gating, where a gate voltage is applied between the graphene and the substrate. This section references these typical tuning methods and discusses their compatibility with THz device integration.

In this work, the numerical simulations were performed based on the Finite Integration method (FIM). Periodic boundary conditions were applied along the x- and y- directions, while a Floquet-port was implemented in the z direction. Specifically, the structure was optimized via parameter sweeps of geometric dimensions (e.g., ring radii, spacer thickness) and material properties (VO2 conductivity, graphene Ef) to maximize bandwidth and absorption. Through this approach, the narrowband and broad-band absorption spectra and the corresponding RCS reduction in the proposed THz metamaterial absorber could be obtained. The absorptivity in the simulation was calculated using the following expression:

where the reflectance R and transmittance T are quantified by the S-parameters, specifically R = |S11|2 and T = |S21|2, where |S11| and |S21| are the reflection and transmission coefficients. Owing to the inclusion of a perfectly reflecting ground plane, transmittance can be regarded as T = 0. Under this condition, the absorptivity A is given simply by A = 1 − R [26].

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. Reconfigurable Absorption of THz Waves

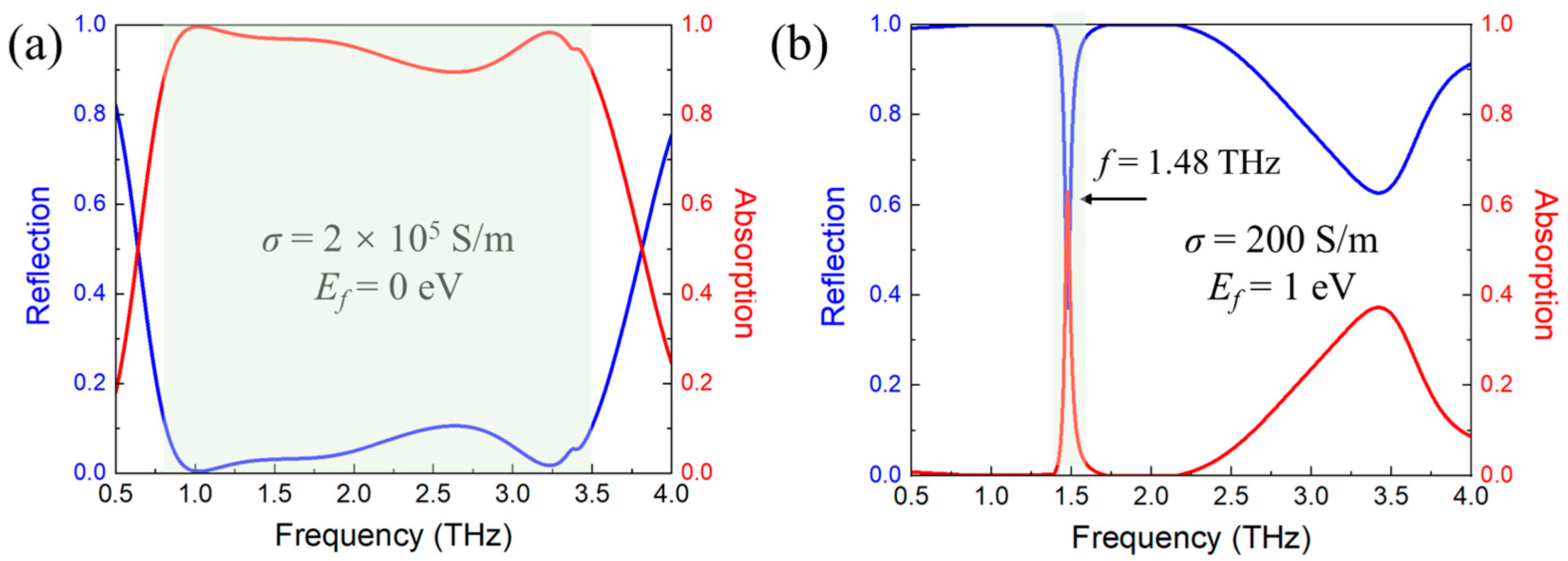

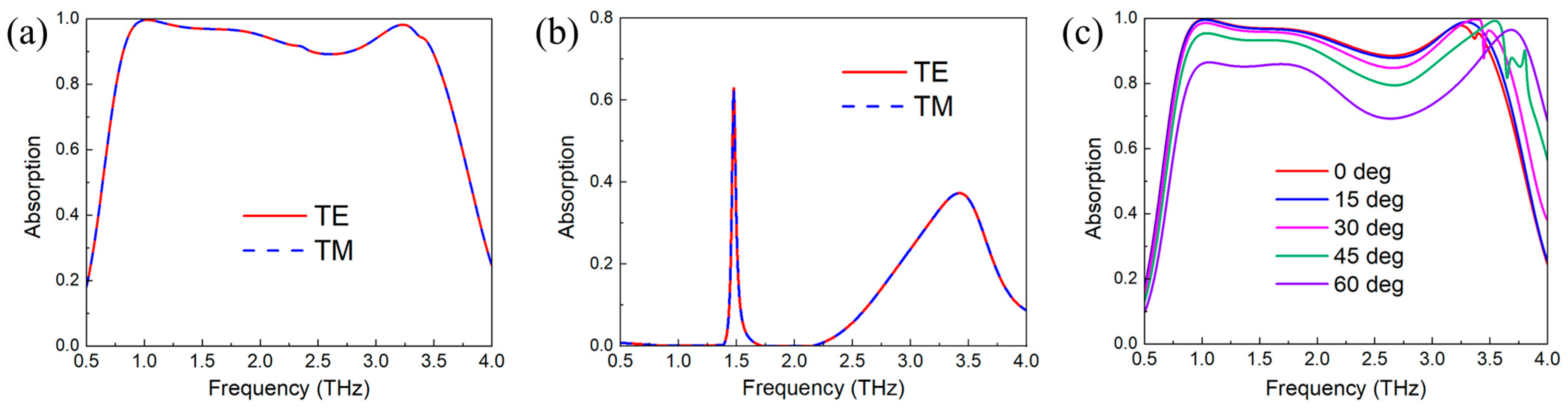

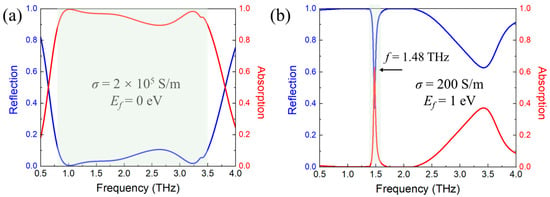

The simulated performance of the multifunctional absorber is presented in Figure 4. This designed THz metamaterial absorber demonstrates reconfigurability between ultra-broadband and narrowband absorption, achieved by modulating the conductivity σ of VO2 (via temperature) and the Fermi energy Ef of graphene (via bias voltage). An ultra-broadband response with over 90% absorptance across 0.82~3.50 THz, corresponding to a relative bandwidth up to 124%, was accomplished when the Fermi energy of graphene was Ef = 0 eV and VO2 was in its metallic state with a conductivity of σ = 2 × 105 S/m. Conversely, two narrowband absorption peaks could be attained with the Fermi energy of graphene at Ef = 1 eV and VO2 in the insulating state with a conductivity of σ = 200 S/m. Specifically, a sharp absorption peak exceeding 60% appeared at 1.48 THz. Accordingly, the presented THz metamaterial absorber achieves flexible switching between ultra-broadband and narrowband absorption modes through the synergistic modulation of VO2 and graphene via external stimuli. This dynamic reconfigurability, coupled with its outstanding absorption performance (high absorptance, wide bandwidth), makes it a highly promising candidate for applications in THz communication, RCS reduction, sensing, and imaging systems.

Figure 4.

The reflection and absorption of designed metamaterial under different material parameters. (a) broadband absorption, (b) narrowband absorption.

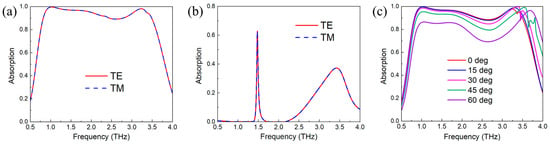

The identical absorption characteristics for TE and TM polarizations, demonstrated in Figure 5a,b, confirm that the proposed metamaterial absorber is polarization-insensitive. This key attribute is intrinsically linked to the four-fold rotational symmetry of the unit cell design. Since the structure presents an identical electromagnetic response when rotated by 90 degrees, its interaction with incident radiation is independent of the polarization angle of incident THz waves, ensuring consistently high absorption without polarization-dependent performance degradation. Moreover, the wide-angle performances of the proposed metamaterial under broadband mode are depicted in Figure 5c. It is clear that the metamaterial absorber maintains stable and high absorption efficiency (>70%) across incidence angles ranging from 0° to 60°, with minimal variation in absorption rate. This indicates that the absorber is highly effective even at oblique angles, showcasing robust wide-angle performance in broadband applications.

Figure 5.

The absorption of designed metamaterial. (a) Broadband absorption for TE and TM polarizations, (b) narrowband absorption for TE and TM polarizations, and (c) wide-angle performances.

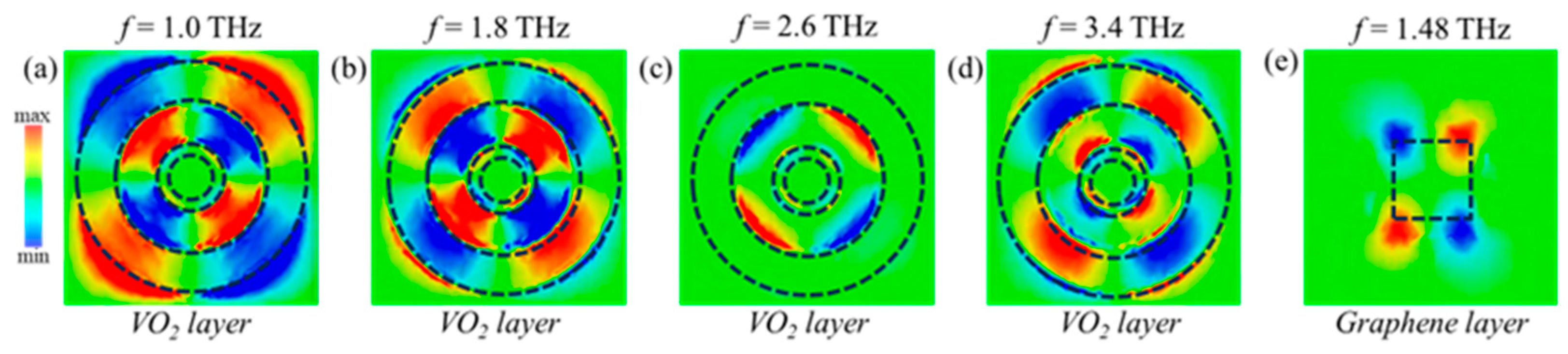

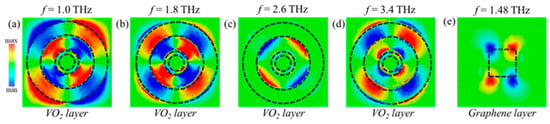

To elucidate the underlying physical mechanisms of THz wave absorption, the electric field distributions under TE-polarized illumination are also investigated. From Figure 5, the electric field evolution for broadband absorption (σ = 2 × 105 S/m, Ef = 0 eV) reveals a distinct modal transition across the absorption. Specifically, at lower frequencies (e.g., f = 1.0 THz), the strong capacitive couplings between the adjacent inner and outer ring of VO2 patches and the electric octupole are in a dominant position, as depicted in Figure 6a. As shown in Figure 6b, although the electric octupole still dominates at the frequency of f = 1.8 THz, the electric field intensity on the outer ring has weakened, with the field now primarily concentrated on the inner ring. From Figure 6c, as the operating frequency increases to f = 2.6 THz, the electric field is almost completely transferred from the outer ring to the inner one, forming an electric quadrupole resonance. However, at the higher frequency of f = 3.4 THz, electric field distribution is observed on both the outer and inner rings, which is associated with the excitation of an electric octupole resonance, as shown in Figure 6d.

Figure 6.

The electric field distributions under TE-polarized illumination (broadband absorption, σ = 2 × 105 S/m, Ef = 0 eV): (a) 1.0 THz, (b) 1.8 THz, (c) 2.6 THz, and (d) 3.4 THz. (e) Narrowband absorption at 1.48 THz, σ = 200 S/m, Ef = 1 eV. Dashed outlines of the VO2 rings and graphene square in each field distribution are plotted for clear reference.

Consequently, the high performance of proposed metamaterial absorber is attributed to the synergistic effects of these complementary resonance mechanisms. The incident wave is efficiently captured and dissipated within the structure through the concerted actions of magnetic resonance at lower frequencies and electric resonance at the higher frequency, thereby achieving the observed enhanced broadband and narrowband absorption [27]. Moreover, it is also worth pointing out that the graphene layer barely has electromagnetic responses due to its Ef = 0 eV.

As for the narrowband absorption of the proposed metamaterial absorber with σ = 200 S/m and Ef = 1 eV, the electric field distributions under TE-polarized illumination are depicted in Figure 6e. It can be observed that the sharp resonance at f = 1.48 THz is attributed to the electric quadrupole. Similarly, the VO2 layer barely has electromagnetic responses due to its weak conductivity of σ = 200 S/m.

To investigate the underlying physical mechanism enabling broadband absorption, the analysis is framed within the context of impedance matching theory. Within this framework, the absorption rate of the metamaterial absorber is fundamentally determined by its ability to minimize reflection, which can be quantitatively described by the following expression [28]:

where S11 and S21 represent the reflection and transmission coefficients (S-parameters), while Z and Z0 denote the effective impedance of the absorber and the characteristic impedance of free space, respectively. The relative impedance is defined as Zr = Z/Z0.

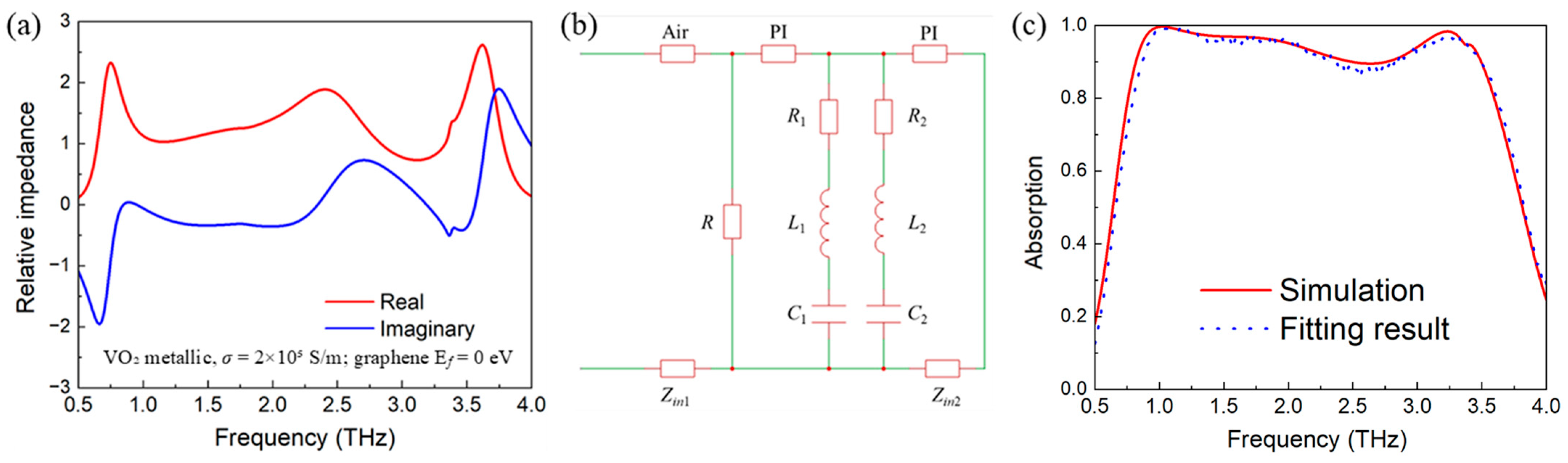

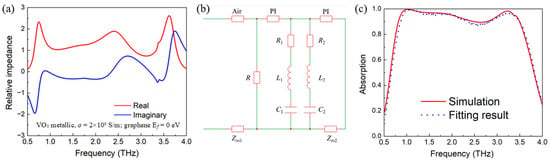

The real and imaginary parts of this calculated relative impedance are plotted in Figure 7. Analysis of the data for the metallic state of VO2 reveals that across the broad frequency range from 0.82 to 3.50 THz, the imaginary part of Zr remains near zero, while the real part approximates unity. This specific condition indicates that the absorber impedance is effectively matched to that of free space, thereby minimizing reflection and fulfilling the fundamental criterion for high-efficiency broadband absorption [29,30].

Figure 7.

(a) Real (red) and imaginary (blue) parts of the relative impedance (VO2 metallic, σ = 2 × 105 S/m; graphene Ef = 0 eV). (b) Equivalent circuit model. (c) Fitting results.

Based on the mapping between its multilayer structure and electromagnetic mechanisms, an equivalent circuit, as shown in Figure 7b, is constructed for the broadband-mode hybrid graphene–VO2 reconfigurable terahertz absorber. The circuit comprises a surface parallel resistor Rc (104–105 Ω) for unbiased graphene; cascaded transmission lines(Zin) for the dielectric spacers; and a core parallel resonant network modeling the VO2 double-ring. This network contains two series of RLC branches: Branch 1 (L1, C1, R1) for the 0.82–2.0 THz electric octupole resonance, and Branch 2 (L2, C2, R2) for the 2.0–3.50 THz electric quadrupole resonance. Their superposition covers 0.82–3.50 THz. The circuit ends with a short circuit for the gold backplane. The combined network impedance matches free space (real part ≈ 377 Ω) across the band. The loss resistors R1 and R2 enable over 90% absorption. The circuit’s symmetry and angular stability reflect the absorber’s polarization-insensitive and wide-angle performance, consistent with reported results. And the fitting results can be obtained by the equivalent circuit model and the above-mentioned parameters, which depicts excellent agreement with the simulation results, as shown in Figure 7c.

It is also worth pointing out that the passive element values of an equivalent circuit model (ECM) are typically obtained through the following steps: First, a preliminary circuit topology is established based on the structure and material properties of the metamaterial unit. Then, electromagnetic simulation based on FIM is employed to obtain the S-parameters (reflection and transmission coefficients) of the structure. Finally, optimization algorithms such as curve fitting and parameter sweeping are applied to adjust the circuit element values so that the frequency response of the ECM (absorption spectrum) matches the simulation results, thereby determining the optimal parameters.

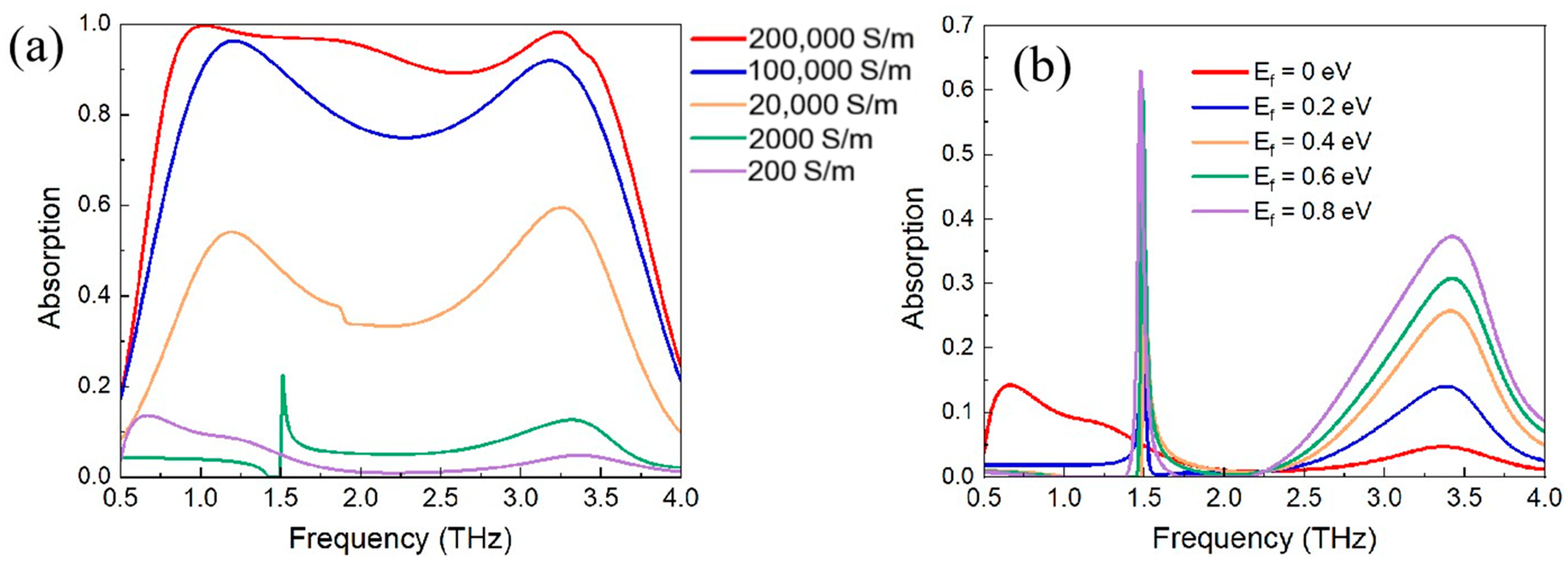

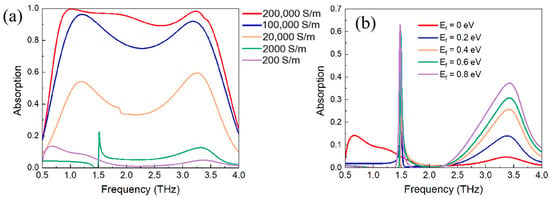

The reconfigurable performance of the proposed metamaterial absorber is quantified in Figure 8. As shown in Figure 8a, the broadband absorption can be effectively switched on or off via the thermally induced phase transition of VO2. Heating (40~80 °C) increases its conductivity over five orders of magnitude (200 S/m to 2 × 105 S/m), changing VO2 from an insulator state to a metallic state (the graphene Ef is fixed as 0 eV). This converts the structure into that of a broadband absorber, switching its state from total reflection (σ = 200 S/m) to near-perfect absorption (σ = 2 × 105 S/m).

Figure 8.

(a) The performances of broadband absorption under different VO2 conductivities with a fixed graphene Fermi level of Ef = 0 eV. (b) The performances of the narrowband absorption curve under varied Fermi energies and a fixed VO2 conductivity of 200 S/m.

For precise narrowband control, Figure 8b demonstrates the active tuning of the narrowband absorption peak by electrically modulating the graphene Ef. When the VO2 is in the insulator state, the integration of graphene enables a distinct, sharp absorption peak within the broadband background. This Fano-type resonant peak arises from the interference between the narrowband resonance of graphene and the broadband mode of the metallic VO2 pattern. As Ef increases from 0 to 0.8 eV, the charge carrier density in graphene rises, which not only leads to a significant red-shift in the resonant peak frequencies but also results in notable changes in the spectral line shape. This effect allows for the continuous and reversible electrical tuning of the resonant frequency without altering the structural geometry, showcasing the potential for dynamic spectral control in terahertz applications such as filtering and sensing.

3.2. Applications of the Bandwidth-Tunable Absorber

3.2.1. Broadband RCS Reduction

The demonstrated ultra-broadband absorption capability, as shown in Figure 3a, can be directly translated into a potent application for broadband RCS reduction. The fundamental principle is that a significant reduction in the electromagnetic wave reflected from a target leads to a lower RCS, thereby diminishing its detectability by radar systems. Since the proposed absorber achieves an absorption rate exceeding 90% across a wide frequency band (0.82~3.50 THz), it effectively suppresses the back-scattered energy over this entire range. To quantitatively evaluate this stealth performance, the monostatic RCS reduction is calculated relative to that of a perfect electric conductor of an identical size, which serves as a standard reference.

The monostatic RCS, denoted as σRCS, is a critical parameter for evaluating the scattering characteristics of a target. Its fundamental definition is derived from the ratio of backscattered power to incident power density, given by the following [31]:

where R is the distance from the target to the radar, Ei is the incident electric field, and Es is the backscattered electric field measured at the radar.

When electromagnetic waves are normally incident on a reflective metasurface composed of two types of units, the backscattering RCS reduction value of the metasurface can be described as follows [32]:

where and represent the numbers of units in the entire metasurface, respectively, while α and 1 − α denote the proportions of units in the entire metasurface. A1 and A2 are their respective reflection amplitudes; φA and φB are their respective reflection phases.

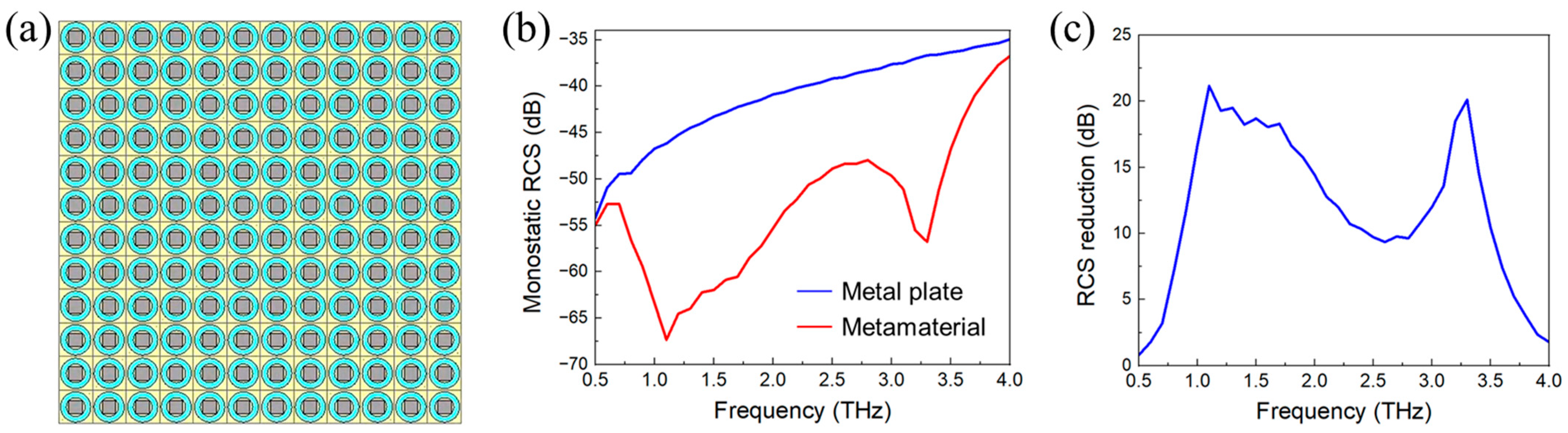

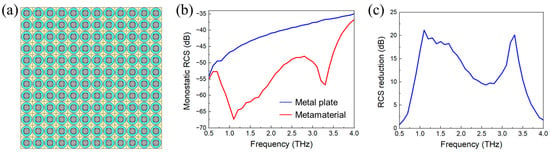

Moreover, all electromagnetic simulations were performed by the finite integration technique (FIT). To evaluate the monostatic RCS reduction (Figure 9), a finite array consisting of 12 × 12 units was modeled (total size 600 μm × 600 μm). Open (add space) boundary conditions were used to simulate free-space scattering. A plane wave was normally incident on the array, and the backscattered electric field was monitored to compute the monostatic RCS. For reference, an identical-sized PEC plate was simulated under the same conditions. The RCS reduction shown in Figure 9c was then obtained as .

Figure 9.

(a) Illustration 12 × 12 metasurface array. (b) Monostatic RCS. (c) RCS reduction.

Figure 9a presents an illustration of the 12 × 12 metasurface array for comparative analysis of the terahertz radar cross-section (RCS) between a metamaterial and a metal plate, which can ensure that the metasurface is large enough to approximate an infinite periodic structure while minimizing edge diffraction effects in the simulation. As shown in Figure 9b, the metamaterial (red curve) exhibits a significantly lower monostatic RCS than the metal plate (blue curve) across a broad frequency range. Figure 9c quantifies this performance advantage by plotting the RCS reduction, demonstrating that the metamaterial achieves an RCS reduction in greater than 10 dB compared to the metal plate over the frequency band from approximately 0.9 to 3.5 THz. This confirms that the specified criterion of an RCS reduction > 10 dB within the 0.82 to 3.50 THz range is successfully met, highlighting the metamaterial’s superior stealth characteristics. A substantial RCS reduction across the operating band confirms that the structure can efficiently minimize its radar signature, making it a highly promising candidate for advanced terahertz stealth platforms.

3.2.2. High-Performance THz Sensing

Beyond the broadband RCS reduction enabled by its strong absorption, the proposed metamaterial absorber also exhibits significant potential for high-performance terahertz sensing, leveraging its sharp, tunable narrowband absorption peaks. The high-Q Fano resonances, achieved when the structure operates in the narrowband mode, as shown in Figure 3b, are exceptionally sensitive to minute changes in the surrounding dielectric environment. This sensitivity arises because the resonant frequency and amplitude are strongly dependent on the effective refractive index near the metamaterial surface, where the electromagnetic field is intensely localized.

The key parameters used to describe the performance of a sensor include sensitivity (S), quality factor (Q), and figure of merit (FOM). These parameters are used to quantify the sensor’s response strength to changes in the refractive index, the sharpness of the resonance peak, and the simultaneous characterization of response strength and frequency resolution, respectively, which determine the detection limit of the sensor. They are defined as follows [33]:

where Δn represents the variation in the refractive index of the measured substance, Δf denotes the shift in resonant frequency caused by this refractive index variation, and FWHM refers to the full width at half maximum of the resonance peak. Therefore, the quality factors of the two resonances are Q = 35.6, which demonstrates that the designed metamaterial absorber exhibits promising sensing capabilities when operating in the narrowband mode.

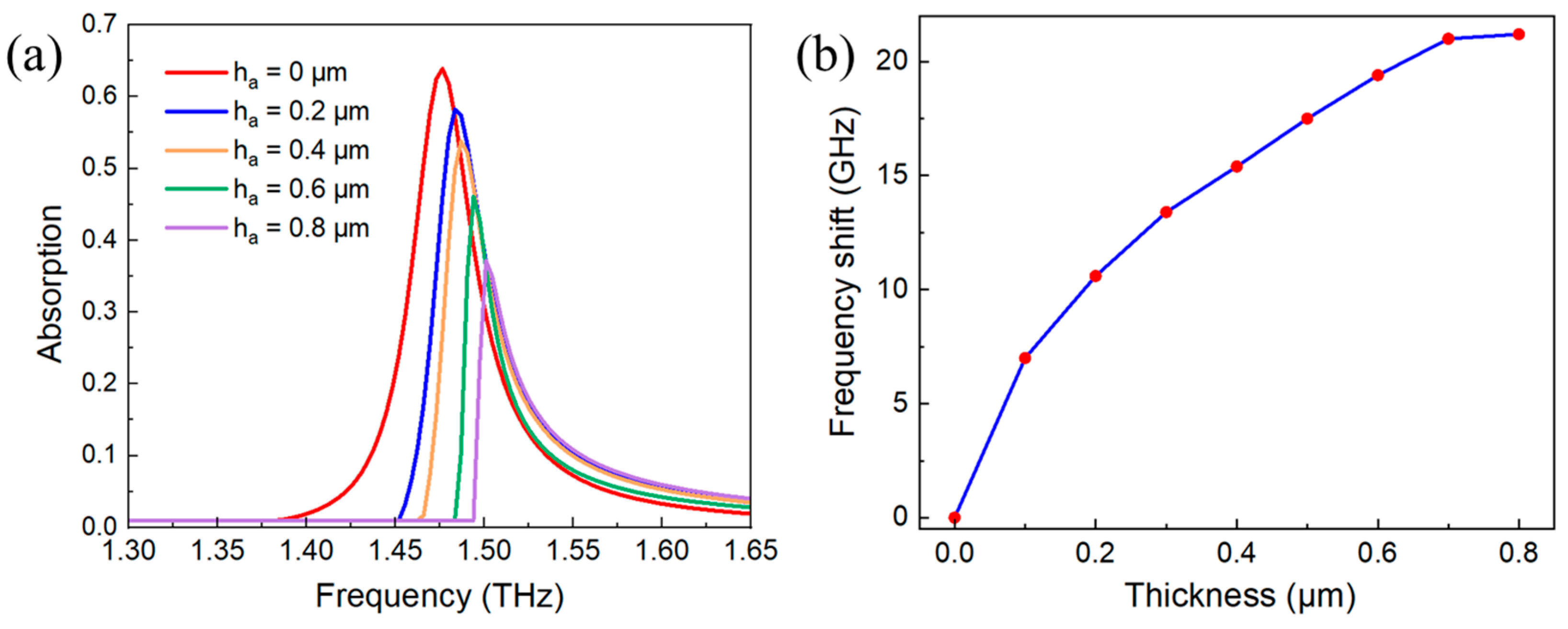

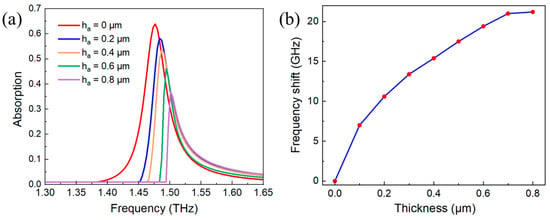

To initiate the analysis, the ambient medium refractive index was fixed at n = 1.4 to systematically evaluate the influence of analyte thickness on the metamaterial sensing performances. The computational results, depicted in Figure 10, demonstrate that under this condition, as the analyte thickness increases from ha = 0 μm to 0.8 μm, the resonance peak intensity in the spectrum progressively attenuates while the resonance frequency shifts systematically toward higher frequencies. The frequency shift exhibits a characteristic nonlinear saturation behavior with increasing thickness: when the thickness remains below 0.2 μm, the frequency shift rises sharply, indicating continuous molecular deposition within high field-strength sensitivity regions. Within the transitional thickness range of 0.2~0.6 μm, the contribution of peripheral molecules to the frequency shift diminishes due to the exponential decay of the localized field intensity with distance, resulting in a pronounced reduction in the rate of frequency shift increase. Beyond 0.8 μm, additional analyte layers reside outside the effective detection range of the localized field, and the frequency shift approaches a saturation limit of 21.2 GHz. Further increases in analyte thickness beyond this point yield no substantial enhancement in the structural sensing sensitivity.

Figure 10.

(a) Frequency spectra and (b) frequency shifts under different analyte thickness conditions (with ambient medium refractive index fixed at n = 1.4).

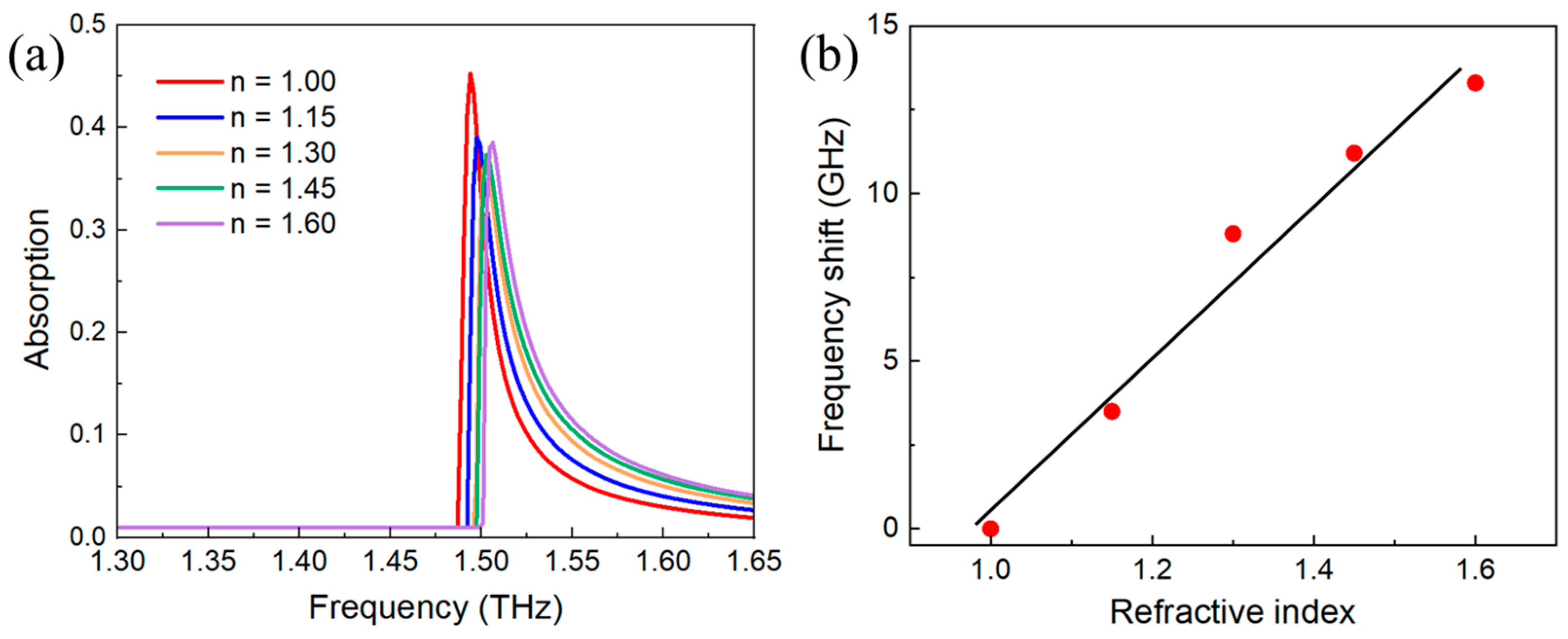

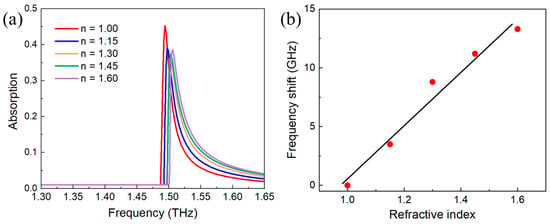

Therefore, the sensor’s ability to distinguish substances with different refractive indices constitutes a key metric for evaluating its applicability and detection performance. The computational results with thickness fixed as ha = 0.8 μm, shown in Figure 11a, reveal systematic trends in the sensor’s response to changes in the ambient refractive index. The spectra in Figure 11a demonstrate that as the refractive index increases from 1.0 to 1.6, all resonance peaks maintain sharp line shapes while exhibiting significant blue shifts, with a total frequency shift range of 13 GHz.

Figure 11.

(a) Frequency spectra and (b) frequency shifts under different ambient refractive index conditions (with thickness fixed as ha = 0.8 μm).

Figure 11b further elucidates the intrinsic relationship between refractive index and sensing response through quantitative analysis. Experimentally measured frequency shifts for six discrete refractive index samples (n = 1.0~1.6, step size 0.15) exhibit a strictly linear trend. A least squares fitting yields the relationship y = 24.86x − 22.37 (unit: GHz), where the slope of 24.86 GHz/RIU represents the sensor’s refractive index sensitivity. This value significantly surpasses that of conventional terahertz sensors (typically < 10 GHz/RIU). Notably, unlike the nonlinear saturation behavior observed with thickness variations, refractive index changes induce stable linear frequency shifts across the entire detection range. This characteristic enables the sensor to determine the refractive index of unknown substances through single-frequency calibration, establishing a crucial technical foundation for the label-free identification of complex mixture components.

The fabrication of the proposed hybrid graphene–VO2 metamaterial absorber begins with the deposition of a gold substrate (thickness h1 = 1 μm) as a perfect reflector, followed by spin-coating a polyimide dielectric spacer (thickness h2 = 17.4 μm) to provide insulation and structural support, after which the VO2 layer (thickness h4 = 1 μm) is patterned into a double-ring structure via lithography and etching (with outer radii r1 = 22.5 μm and r2 = 14 μm), and finally, a graphene square sheet (length l = 20 μm) is transferred and patterned atop the stack to complete the symmetrical unit cell design. This is critical for switching between insulating and metallic states, and controlling graphene doping stability to maintain Fermi level tuning without fluctuations that could degrade absorption performance. Experimental deviations, including surface roughness-induced scattering, interfacial defects between layers, and alignment tolerances during patterning, may lead to reduced absorption efficiency (e.g., dips below 90% in the 0.82–3.50 THz band) or resonance shifts, impacting applications like RCS reduction and sensing. To mitigate these, strategies involve using atomic layer deposition for uniform dielectrics to minimize losses, post-annealing VO2 to enhance crystallinity and phase transition consistency, and implementing electrostatic screening for graphene to stabilize electrostatic gating, thereby improving reproducibility and aligning with the simulated achievements of a 124% relative bandwidth and 24.86 GHz/RIU sensitivity. This integrated approach underscores the design’s practicality for terahertz systems, despite being simulation-based.

A performance comparison between the proposed absorber and several recently reported tunable THz metamaterial absorbers is summarized in Table 1. The proposed graphene–VO2 hybrid design achieves a notable 124% relative bandwidth while integrating both broadband RCS reduction and high-sensitivity sensing, highlighting its advantages in operational bandwidth and multifunctionality.

Table 1.

Performance comparison between the proposed absorber and previously reported ones.

4. Conclusions

In this work, a hybrid graphene–VO2 metamaterial absorber with dynamically reconfigurable absorption characteristics has been designed and numerically validated. The synergistic integration of VO2 thermally induced phase transition and graphene’s electrically tunable Fermi level enables flexible switching between ultra-broadband and narrowband absorption modes. The absorber achieves over 90% absorption across 0.82~3.50 THz in the broadband state and a sharp resonant peak in the narrowband state, both with excellent polarization insensitivity and angular stability. The structure also demonstrates significant potential for practical applications, including broadband RCS reduction exceeding 10 dB and high-performance refractive index sensing with a sensitivity of 24.86 GHz/RIU. These findings highlight the versatility and performance of the proposed metamaterial, paving the way for advanced terahertz devices in communication, stealth, and sensing.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.S.; methodology, K.S.; software, K.S. and W.Y.; validation, K.S., Y.L. and W.Y.; formal analysis, K.S.; investigation, K.S. and W.Y.; resources, K.S.; data curation, K.S.; writing—original draft preparation, K.S.; writing—review and editing, K.S.; visualization, K.S.; supervision, Y.L. and W.Y.; project administration, Y.L.; funding acquisition, Y.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Tonouchi, M. Cutting-edge terahertz technology. Nat. Photonics 2007, 1, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akyildiz, I.F.; Han, C.; Nie, S. Combating the Distance Problem in the Millimeter Wave and Terahertz Frequency Bands. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2018, 56, 102–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zheng, C.; Xu, H.; Li, J.; Song, C.; Li, J.; Wu, L.; Yang, F.; Zhang, Y.; Shi, W.; et al. Diatomic terahertz metasurfaces for arbitrary-to-circular polarization conversion. Nanoscale 2022, 14, 12856–12865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stantchev, R.I.; Li, K.D.; MacPherson, E.P. Real-time terahertz imaging with a single-pixel detector. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 2535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, S.J.; Kim, S.H.; Ji, Y.B.; Jeong, K.; Park, Y.; Yang, J.; Park, D.W.; Noh, S.K.; Kang, S.G.; Huh, Y.M.; et al. Study of freshly excised brain tissues using terahertz imaging. Biomed. Opt. Express 2014, 5, 2837–2842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, S.H.; Wang, C.H.; Ke, P.X.; Yang, C.F. Using Planar Metamaterials to Design a Bidirectional Switching Functionality Absorber—An Ultra-Wideband Optical Absorber and Multi-Wavelength Resonant Absorber. Photonics 2024, 11, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y.F.; Li, T.T.; Zhu, P.; Ma, F.P.; Wu, H.J.; Lei, C.; Liu, M.H.; Liang, T.; Yao, J.Q. Optimal Design of a Lightweight Terahertz Absorber Featuring Ultra-Wideband Polarization-Insensitive Characteristics. Photonics 2025, 12, 787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, M.F.; Ji, S.J.; Zhao, J.; Li, J.J. Gallium nitride ultra-wideband terahertz absorber based on periodic pyramidal array. J. Phys. D-Appl. Phys. 2025, 58, 105104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.S.; Xin, F.K.; Fu, Q.H.; Xia, D.Y. A Thermally Controlled Ultra-Wideband Wide Incident Angle Metamaterial Absorber with Switchable Transmission at the THz Band. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, X.Q.; Fan, W.H.; Chen, X.; Zhao, L.R.; Qin, C.; Yan, H.; Wu, Q.; Ju, P. High accuracy inverse design of reconfigurable metasurfaces with transmission-reflection-integrated achromatic functionalities. Nanophotonics 2025, 14, 921–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.J.; Liao, K.; Ma, W.K.; Wen, R.Q.; Li, Z.; Liu, K.; Li, F. Reconfigurable three-channel terahertz reflective metasurface. Appl. Opt. 2025, 64, 6006–6013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.J.; Feng, Q.; Lei, G.M.; Li, Q.F.; Liu, H.X.; Xu, P.; Han, J.Q.; Shi, Y.; Li, L. Reconfigurable EIT Metasurface with Low Excited Conductivity of VO2. Photonics 2024, 11, 1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.L.; Wang, Z.N.; Guan, M.Z.; Cheng, S.B.; Ma, H.Y.; Yi, Z.; Li, B.X. Tunable Ultra-Wideband VO2–Graphene Hybrid Metasurface Terahertz Absorption Devices Based on Dual Regulation. Photonics 2025, 12, 987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Gao, F.; Teng, S.H.; Guo, T.T.; Luo, C.G.; Zeng, Y. Terahertz VO2-Based Dynamic Coding Metasurface for Dual-Polarized, Dual-Band, and Wide-Angle RCS Reduction. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.Z.; Wu, X.D.; Xiong, C.J.; Zhang, J.; Hu, B. Polarization spatial diversity and multiplexing MIMO surface enabled by graphene for terahertz communications. Nanophotonics 2025, 14, 2909–2922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Zhang, J.H.; Chen, A.P.; Song, Z.Y. Vanadium Dioxide-Based Bifunctional Metamaterial for Terahertz Waves. IEEE Photonics J. 2019, 12, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.Y.; Li, C.; Wang, D.; An, W.; Gao, S.; Zhang, C.W.; Guo, S.J. Tunable wideband-narrowband switchable absorber based on vanadium dioxide and graphene. Opt. Express 2022, 30, 41328–41339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.S.; Sun, X.H.; Liu, L.P.; Qin, G.C.; Li, T. Ultra-wideband switchable multifunctional terahertz hypersurfaces based on graphene and VO2. Phys. Scr. 2025, 100, 085513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Q.; Xu, C.L.; Jiang, J.M.; Li, Y.F.; Cheng, Y.; Wang, H.; Yan, M.B.; Wang, J.F.; Ma, H.; Qu, S.B. General strategy for ultrabroadband and wideangle absorbers via multidimensional design of functional motifs. Photonics Res. 2022, 10, 2202–2214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Fan, W.H.; Chen, X.; Song, C.; Jiang, X.Q. Graphene based polarization independent Fano resonance at terahertz for tunable sensing at nanoscale. Opt. Commun. 2019, 439, 61–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, S.-X.; Zhang, D.; Zhai, X.; Wang, L.-L.; Wen, S.-C. Phase-controlled topological plasmons in 1D graphene nanoribbon array. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2023, 123, 101102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Qing, G.; Zhang, D.; Zhai, X.; Peng, J.; Xia, S.-X. Dynamically tunable and ultrastable plasmonic bound states in the continuum in bilayer graphene metagratings. Phys. Rev. B 2025, 112, 205421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Xia, S.; Xu, W.; Zhai, X.; Wang, L. Topological plasmonically induced transparency in a graphene waveguide system. Phys. Rev. B 2024, 109, 245420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Cai, B.; Yang, L.L.; Wu, L.; Cheng, Y.Z.; Chen, F.; Luo, H.; Li, X.C. Transmission/reflection mode switchable ultra-broadband terahertz vanadium dioxide (VO2) metasurface filter for electromagnetic shielding application. Surf. Interfaces 2024, 49, 104403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Ma, S.J.; Fu, W.T.; Huang, S.; Zhu, Y.F.; Luo, X.F. Vanadium dioxide-based terahertz metasurface device with switchable broadband absorption and beam steering functions. Opt. Commun. 2024, 560, 130486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, N.M.; Li, Y.J.; Chen, F.T.; Han, Z.Y. In situ fabrication of a direct Z-scheme photocatalyst by immobilizing CdS quantum dots in the channels of graphene-hybridized and supported mesoporous titanium nanocrystals for high photocatalytic performance under visible light. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 42233–42245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mou, N.L.; Sun, S.L.; Dong, H.X.; Dong, S.H.; He, Q.; Zhou, L.; Zhang, L. Hybridization-induced broadband terahertz wave absorption with graphene metasurfaces. Opt. Express 2018, 26, 11728–11736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Z.Q.; Liang, J.G.; Cai, T.; Wang, G.M.; Deng, T.W.; Wu, B.R. Designing an ultra-thin and wideband low-frequency absorber based on lumped resistance. Opt. Express 2022, 30, 914–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Xia, F.; Li, S.X.; Liu, Y.; Kong, W.J. Actively tunable multi-band terahertz perfect absorber due to the hybrid strong coupling in the multilayer structure. Opt. Express 2021, 29, 28619–28630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bossard, J.A.; Lin, L.; Yun, S.; Liu, L.; Werner, D.H.; Mayer, T.S. Near-ideal optical metamaterial absorbers with super-octave bandwidth. ACS Nano 2014, 8, 1517–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Zhang, N.J.; Dong, P.; Yang, L.; Wang, B.Z.; Wu, R.H.; Hou, W.M. All-Metal Coding Metasurfaces for Broadband Terahertz RCS Reduction and Infrared Invisibility. Photonics 2023, 10, 962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Mao, R.Q.; Gao, M.; Zheng, Y.J.; Chen, Q.; Fu, Y.Q. Absorption and cancellation radar cross-section reduction metasurface design based on phase- and amplitude-control. Acta Phys. Sin. 2022, 71, 084102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.Q.; Fan, W.H.; Chen, X.; Yan, H. Ultrahigh-Q terahertz sensor based on simple all-dielectric metasurface with toroidal dipole resonance. Appl. Phys. Express 2021, 14, 102008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, T.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Tang, Y.; He, X. Dual-function switchable terahertz metamaterial device with dynamic tuning characteristics. Results Phys. 2023, 45, 106246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhou, X.; Li, Y. A terahertz broadband and narrowband switchable absorber based on joint modulation of vanadium dioxide and graphene surfaces. Phys. Scr. 2024, 99, 095542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Wu, T.; Jiang, J.; Jia, Y.; Gao, Y.; Gao, Y. Switchable terahertz absorber from single broadband to triple-narrowband. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2022, 130, 109460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liu, Y.; Jia, Y.; Su, N.; Wu, Q. Ultra-wideband and narrowband switchable, bi-functional metamaterial absorber based on vanadium dioxide. Micromachines 2023, 14, 1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.