Abstract

Exceptional points (EPs) are the most intriguing features of non-Hermitian systems associated with symmetry- and topology-driven applications. In this paper, we study the influence of tunable anisotropy on the topological properties of EPs in -symmetric layered structures. In particular, the eigenvalues exchange and eigenmodes exchange are predicted at the points of equal light transmission of different polarizations. We also unveil that the EPs tailored by the anisotropy parameters are associated with the phase jump of reflection coefficients. Indirect evidence for the topological nature of EPs shown here is important for deeper insights into behaviors of anisotropic non-Hermitian systems and can be further used for the development of tunable non-Hermitian sensors and other applications.

1. Introduction

In recent decades, the effects of non-Hermiticity have entered the spotlight of the optics and photonics community [1,2,3]. In a broad sense, non-Hermiticity implies that a system in question is open and can exchange energy with the environment. Hence, most real optical systems are non-Hermitian. In a narrower sense, non-Hermitian systems are defined as those described with a non-Hermitian operator (either Hamiltonian or scattering matrix). Such a description entails the appearance of special singularities—exceptional points (EPs), where both eigenvalues and eigenvectors of the corresponding non-Hermitian operator degenerate [4,5]. EPs are the most prominent features of non-Hermitian photonic systems attracting attention due to their outstanding properties indispensable in sensing enhancement [6,7], laser design [8], lasing-antilasing devices [9,10], modification of spontaneous-emission decay [11], etc.

The great prospects of EP applications are connected to their nontrivial topological properties [12,13]. The latter are due to the nonzero (half-integer) winding number manifesting itself as a topological phase accumulated when encircling an EP in the parameter space [14]. The half-integer winding number of an EP implies that a single circle around it results in mode switching [15]. The dynamic encirclement with the continuous change of parameters in space or time was reported to realize non-adiabatic transitions [16,17], chiral mode switching [18,19,20,21], logical operations [22], entanglement switching [23], and so on. Simultaneous encircling multiple EPs is characterized by its own features, as discussed in Refs. [24,25,26]. A number of phenomena have a topological origin as localized states in non-Hermitian systems (non-Hermitian skin effect) [27,28,29] and radiation transport in general [30,31,32].

In this paper, we show that anisotropy provides a new means for manipulating the response of non-Hermitian layered photonic structures and identifying implicit signs of their nontrivial topology. In earlier works [33,34], we showed how anisotropy can be employed to control positions and numbers of EPs in -symmetric layered structures. Multilayer systems are advantageous in studying anisotropy effects, since EPs as the points of -symmetry breaking can be readily determined in this case. Here, eigenvalue exchange and eigenmode exchange are reported for -symmetric structures at the intersection point of transmission coefficients, which can be tuned with the non-Hermiticity parameter as well as with the optical axis orientation of an anisotropic medium. We further demonstrate that the reflection coefficients in this system undergo the phase jump at the EPs that can also be controlled with anisotropy parameters. The results indirectly imply the topological nature of the considered EPs and can be used in sensing.

2. Structure Description

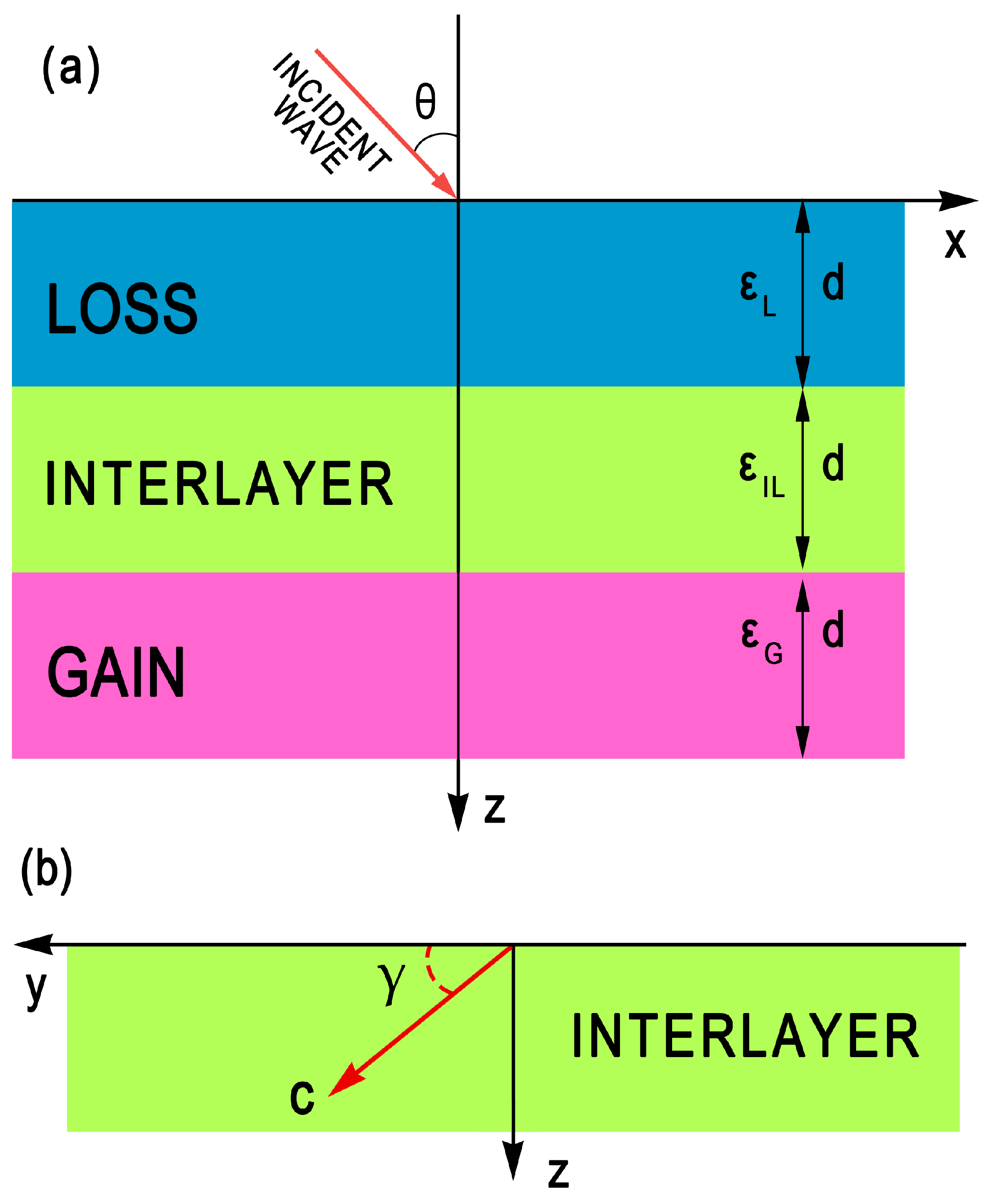

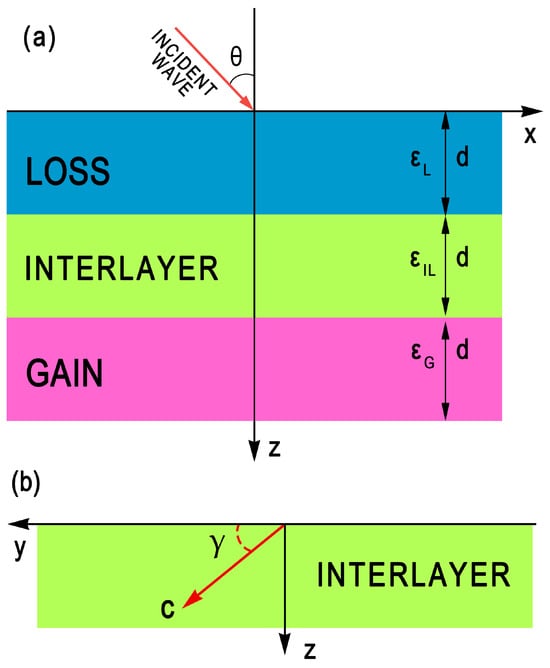

We investigate the propagation of monochromatic plane waves in -symmetric trilayer systems, as performed in Ref. [33]. The structure depicted in Figure 1a features a central anisotropic interlayer sandwiched between two isotropic outer layers. The thicknesses of all layers are the same, namely, d = 2 μm. The outer layers are characterized by the conjugate complex dielectric permittivities to provide the balance of optical gain and loss, the symmetry being parameterized by the non-Hermiticity parameter . In our calculations, we assume that the refractive index is equal to , whereas corresponds to the realistic gain coefficients of cm−1 at μm. We use the E7 liquid-crystal mixture [35] as a material of the anisotropic interlayer with the dielectric permittivity tensor

where ⊗ denotes the tensor product, is the three-dimensional unit tensor, and and are the ordinary-wave and extraordinary-wave refractive indices, respectively. is the unit vector of the optical axis direction, where T denotes the transposition and stands for the out-of-plane angle between the optical axis and the plane of the layer, as shown in Figure 1b. Here, we consider only the effects stemming from the out-of-plane orientation of the optical axis in concordance with Ref. [34]. The case of the in-plane (azimuthal) orientation of the optical axis was studied in Ref. [33].

Figure 1.

(a) -symmetric trilayer structure consisting of loss and gain layers separated by an anisotropic interlayer. (b) Optical axis orientation of the anisotropic interlayer. Light propagates along the z axis.

The anisotropic interlayer realizes the dependence of the transmission and reflection coefficients on the polarization of the incident light. The transmission and reflection characteristics enter the scattering matrix of the form

which accounts for the incident light polarization and the propagation direction. The subscripts and denote the co-polarized amplitude transmission and reflection coefficients, whereas and stand for the cross-polarized ones. The superscripts R (right) and L (left) mark the directions of light propagation. It should be noticed that the reflection coefficients from the non-Hermitian structures depend on the propagation direction. To calculate the amplitude transmission and reflection coefficients appearing in Equation (2), we engage the operator method briefly described in Appendix A.

3. Results

3.1. Eigenvalues and Eigenmodes Exchange

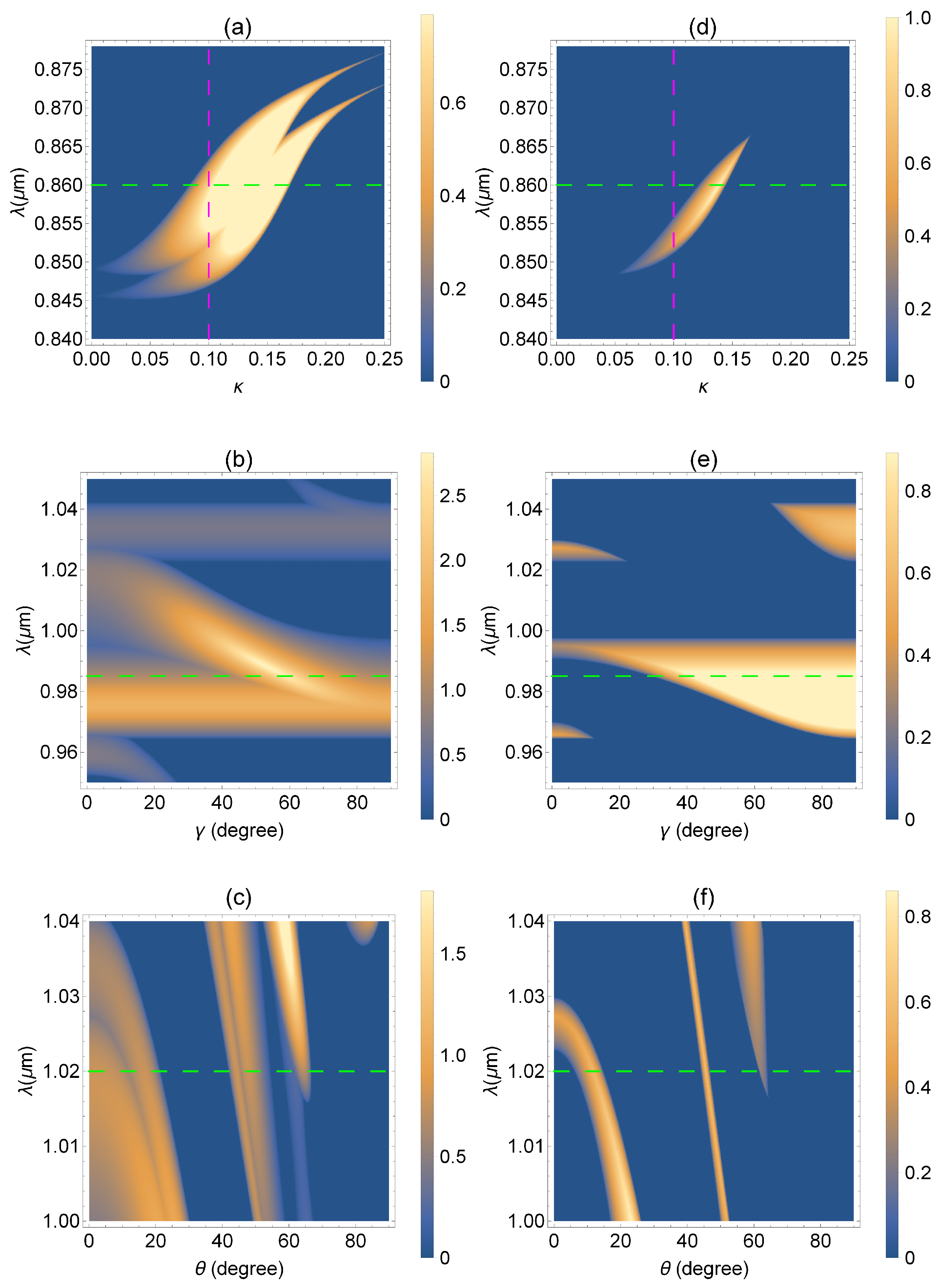

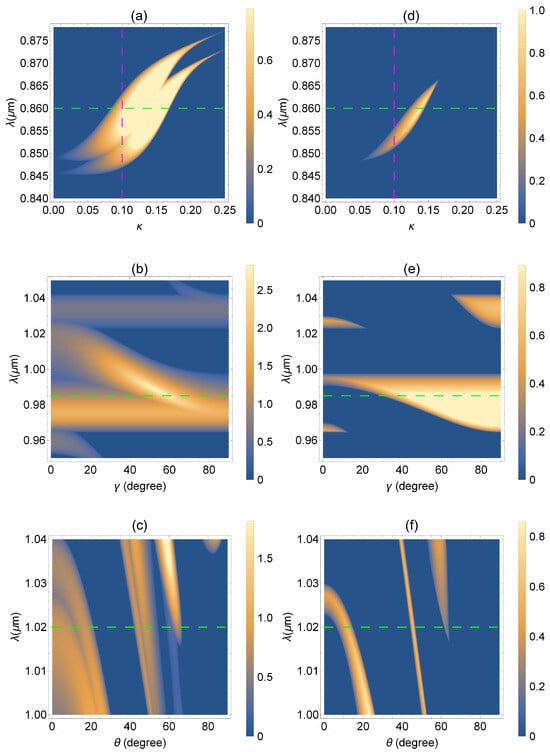

It is well accepted that the EPs emerging in isotropic -symmetric multilayers delimit the parameter space into two parts: the -symmetric phase, where the scattering-matrix eigenvalues are unimodular (), and the -symmetry-broken phase, where the absolute values of eigenvalues are inverse () [36]. In the presence of an anisotropic medium, the situation is more involved, since the cross-polarization effects come to play and we cannot decouple the problem into two independent problems with orthogonal polarizations. Now the scattering matrix has to have the size with the doubled number of eigenvalues. As a result, -symmetry breaking occurs for two pairs of eigenvalues. The full map of regions of the -symmetry-broken phase can be seen in Figure 2 as a set of bright spots. We plot the modulus of the logarithm of the eigenvalue taking into account both eigenvalues in the pair at once: . Dependencies on different parameters are illustrated in Figure 2 for two pairs of eigenvalues: the plane [panels (a) and (d)], the plane [panels (b) and (e)], and the plane [panels (c) and (f)]. Different diagrams demonstrate EP formation and -symmetry breaking under variation in system parameters: the non-Hermiticity (loss and gain) value , out-of-plane angle , and the incidence angle .

Figure 2.

Density plot of the absolute values of the eigenvalue magnitude logarithm as a function of (a,d) and with and ; (b,e) and with , ; (c,f) and with , . Calculations are performed for (a–c) the first and (d–f) second pair of eigenvalues.

Comparing Figure 2a,d, one can see that there is an intersection of the -symmetry-broken regions obtained for both pairs of EPs. We considered such intersections in our previous work [33] and related them to the splittings of the -symmetry-broken regions due to anisotropy. We provided a classification of these regions based on the types of reflection zeros, limiting the regions from both sides. Here, we are interested in the specific properties of the points where the -symmetry-broken regions touch.

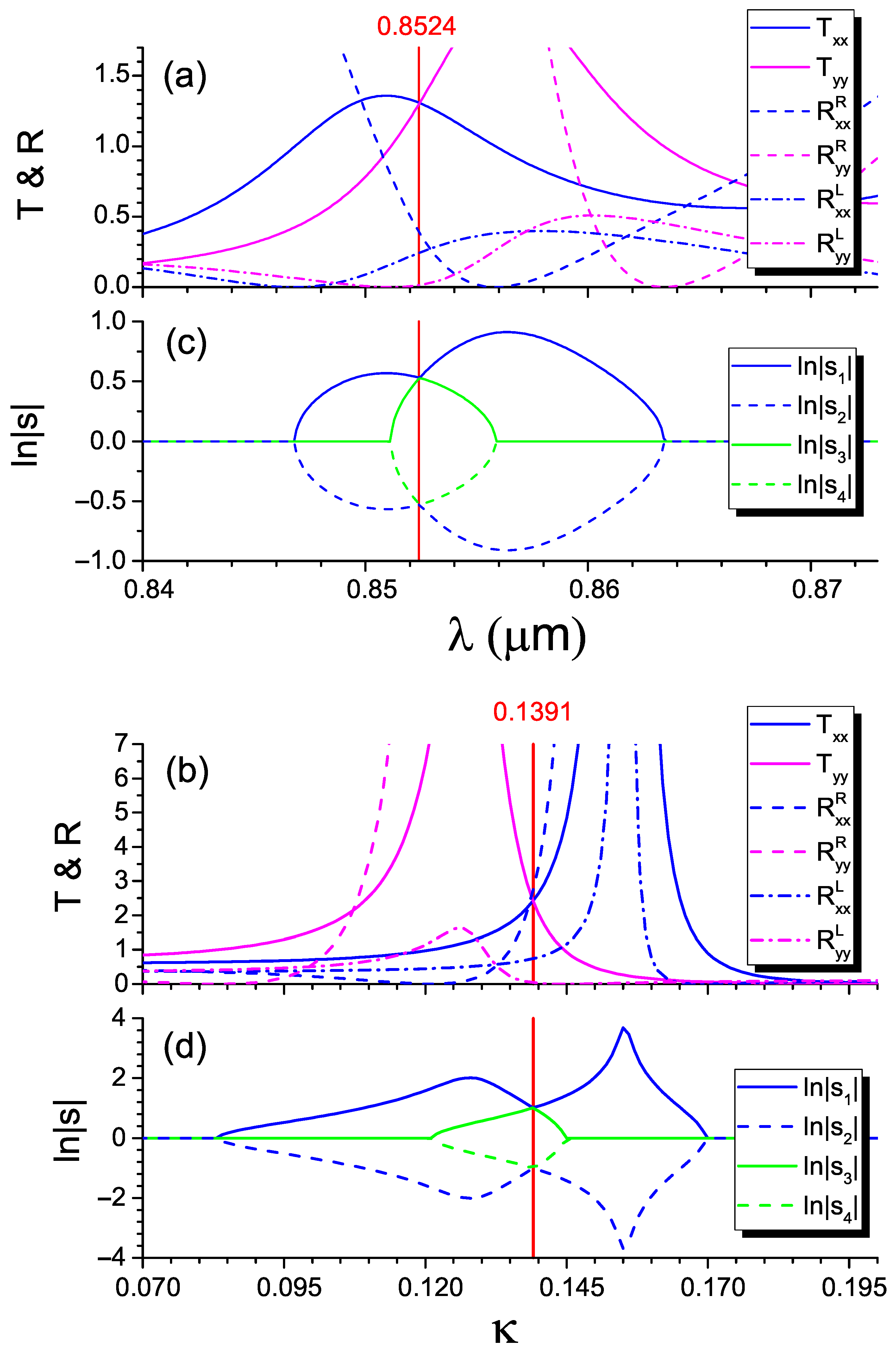

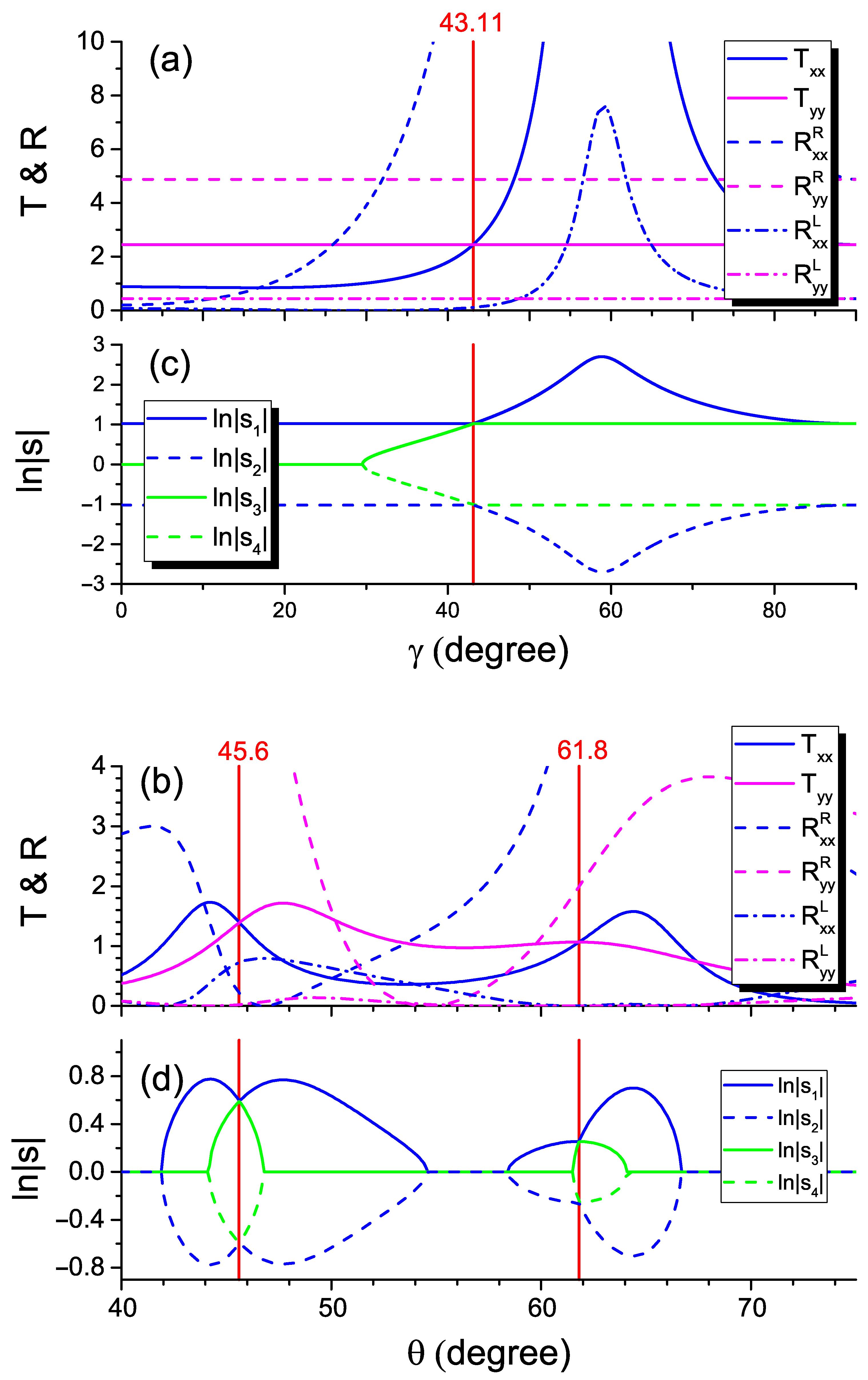

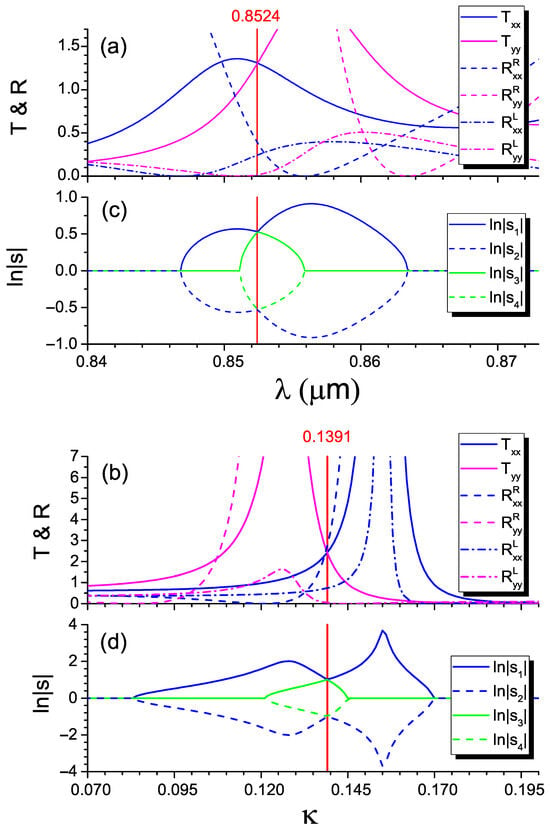

To make clear what points we have in mind, in Figure 3c,d, we plot the cross-sections of the two-dimensional diagram in Figure 2a along the dashed lines. In Figure 3d, we fix the wavelength μm and sweep the non-Hermiticity values starting with . We see that all the scattering-matrix eigenvalues are unimodular at first, so that the logarithms of their magnitudes are equal to zero. At , the first EP appears as the coalescence of the first and second eigenvalues. The symmetry is broken above this EP, where . The third and fourth eigenvalues merge at . Above the latter value, there is the intersection of -symmetry-broken regions. The regions touch at , marked with the vertical red line. This point is the very feature we are interested in here. At this point, the trajectories for the first and second eigenvalues exchange, which is manifested in the line color exchange. This is in contrast to our expectations that the logarithm of the first eigenvalue magnitude (solid blue line) continues decreasing and the logarithm of the third eigenvalue magnitude (solid green line) continues increasing above . The exchange is also observed in Figure 3c at the wavelength μm for the non-Hermiticity parameter .

To clarify what happens at the exchange point, we plot the spectra of transmission and reflection respectively in Figure 3a,b. We observe that the transmission coefficients for both polarizations become equal as at the exchange points (see the vertical red lines). It is important to note that these coefficients are larger than unity, since they correspond to the -symmetry-broken regions. The relation between the eigenvalue exchange and the equality of the transmission coefficients can be grasped using the properties of the scattering matrix (2). Indeed, both the transmission coefficients and eigenvalues of the scattering matrix take the diagonal of . Therefore, the simultaneous exchange of eigenvalues and transmission coefficients seems to be quite natural.

Further, we checked whether the eigenvalues are equal at the exchange point, which is a contender for an EP. To this end, in Figure 4, we separately plot the real and imaginary parts of the scattering-matrix eigenvalues as a function of the non-Hermiticity value. One can see that at the exchange point , the eigenvalues do not coalesce. The real and imaginary parts change abruptly in such a way as to guarantee the same modules of the eigenvalues. Our calculations reveal that the eigenmodes exchange at this point as well, showing a behavior similar to the eigenvalues dependencies in Figure 4. Thus, the exchange point is not an EP, but the point lying between the EPs. The exchange resembles the mode switching effect observed in non-Hermitian structures under encircling EPs in the parameter space [15]. The exchange of eigenvalues and eigenmodes is clearly connected to the presence of polarization-associated EPs in the anisotropic structure. This observation can be considered as indirect evidence of the nontrivial topological properties of these EPs.

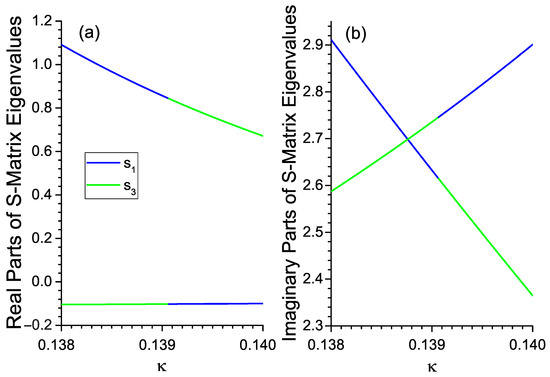

Figure 4.

(a) Real and (b) imaginary parts of the scattering matrix eigenvalues as a function of the non-Hermiticity parameter for μm.

We have discussed above the eigenvalues and eigenmodes arising under variation of the wavelength and non-Hermiticity value. However, from a practical point of view, we may look for the other set of parameters, which can be varied in an easier and more convenient fashion. As shown in Figure 2b,e, the shift of EPs is achieved using the out-of-plane angle that can be realized with the electric-field-induced optical axis orientation (Frederiks effect). In this case, the positions of the EPs stay almost intact with the angle (horizontal bright spots) in the -symmetry-broken regions. For the cross-section of these diagrams along the dashed green lines, the eigenvalue trajectories are demonstrated in Figure 5c. The exchange point appearing at corresponds to the equality of the transmission coefficients [see the vertical red line in Figure 5a].

Figure 5.

(a,b) Transmission and reflection spectra and (c,d) the logarithm of the scattering-matrix eigenvalues magnitude. Calculations were performed for at (a,c) μm and (b,d) μm, corresponding to the dashed lines in Figure 2b,c,e,f. Verical red line marks the position of EP.

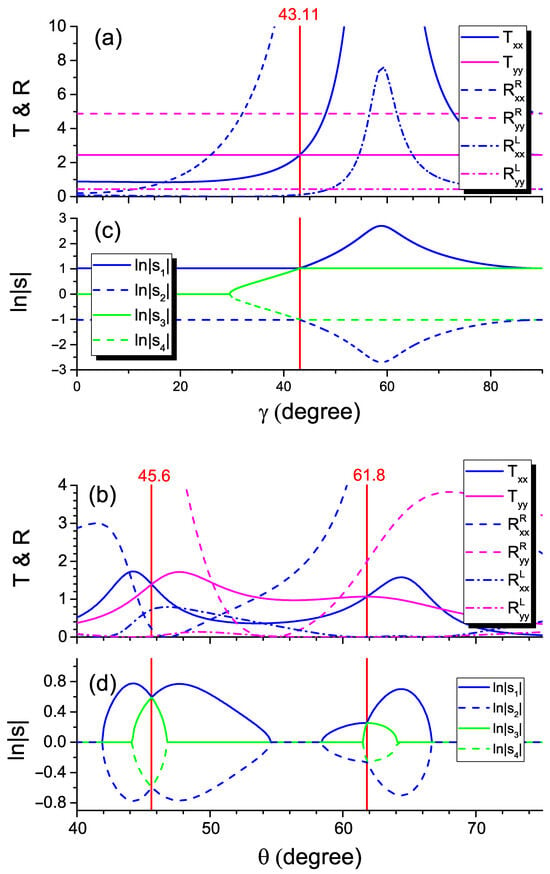

3.2. Phase Jumps at the Exceptional Points

A direct way to prove topological properties of EPs consists of calculating the phase accumulated upon encircling such a point in the parameter space and, thus, finding a corresponding winding number. In the multilayer system considered in this paper, the encirclement could be realized by simultaneously changing two parameters (for example, the out-of-plane angle and incident angle ) in time. When we change a single parameter, the EPs may only form the lines separating the -symmetry-broken regions, as shown in Figure 2. When the two parameters vary together, the exceptional lines merge, producing exceptional surfaces. As a result, it is impossible to draw a closed loop around any EP without crossing an exceptional surface, that is, without transit through other EPs, but it violates the necessary condition for encirclement operation.

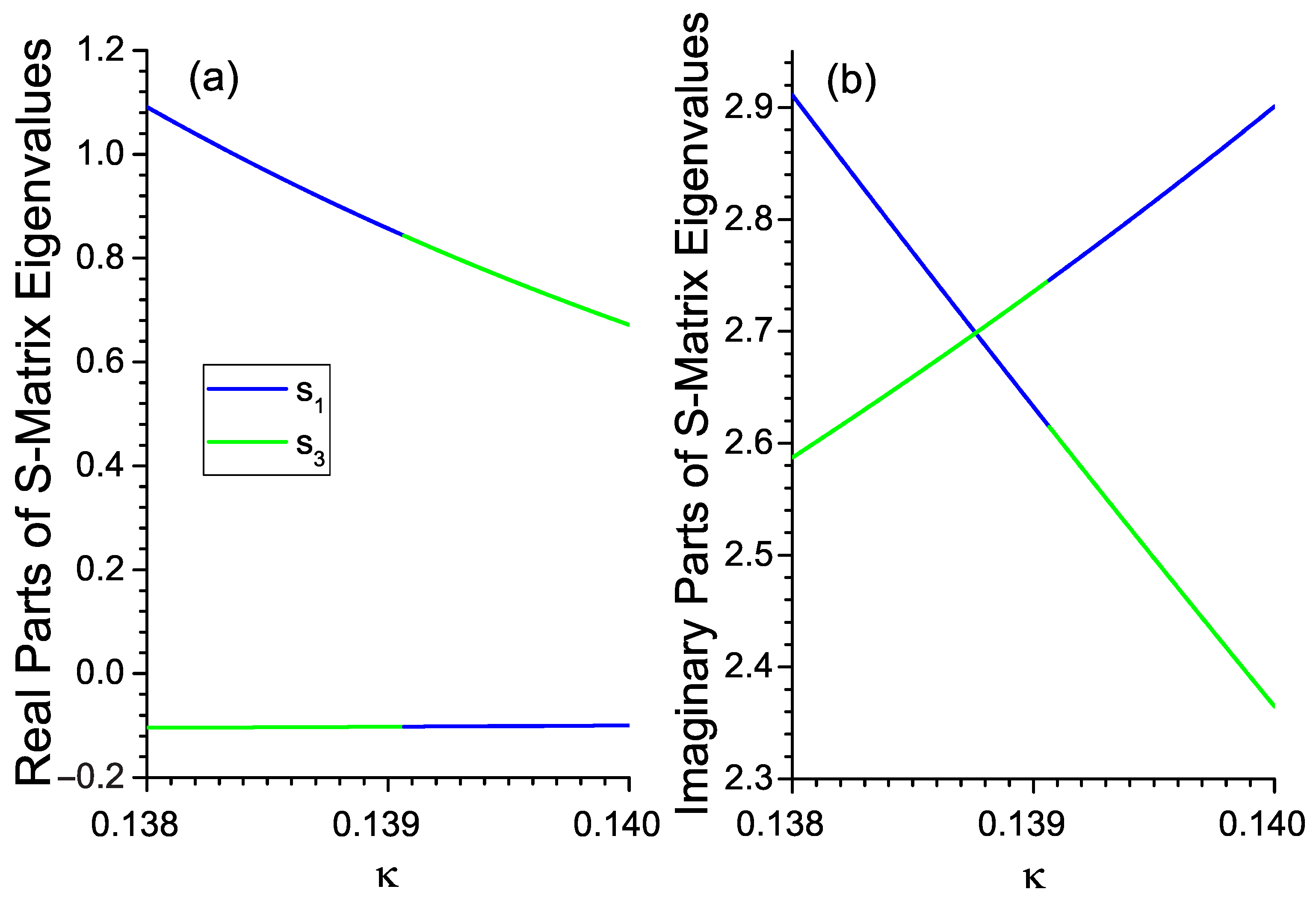

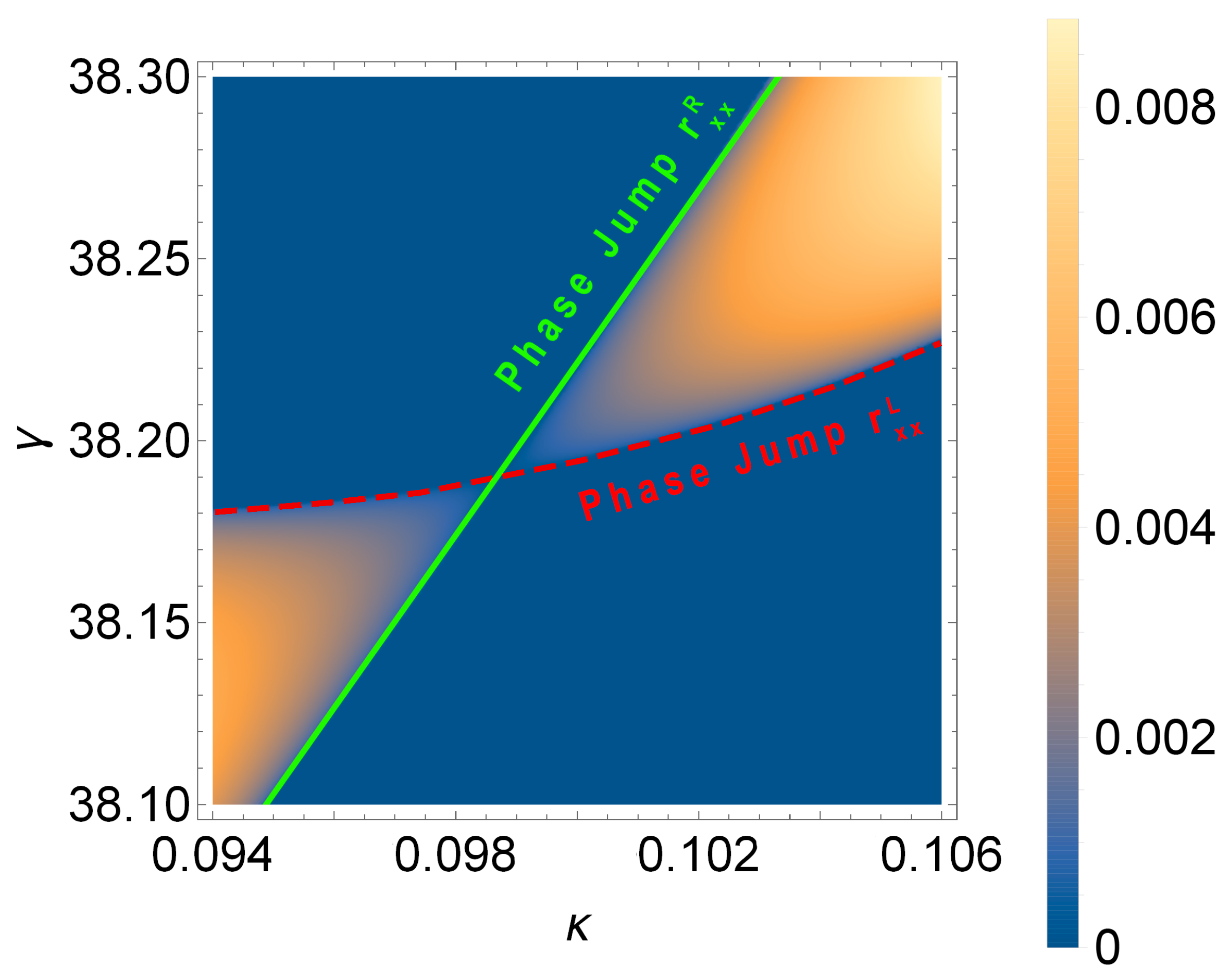

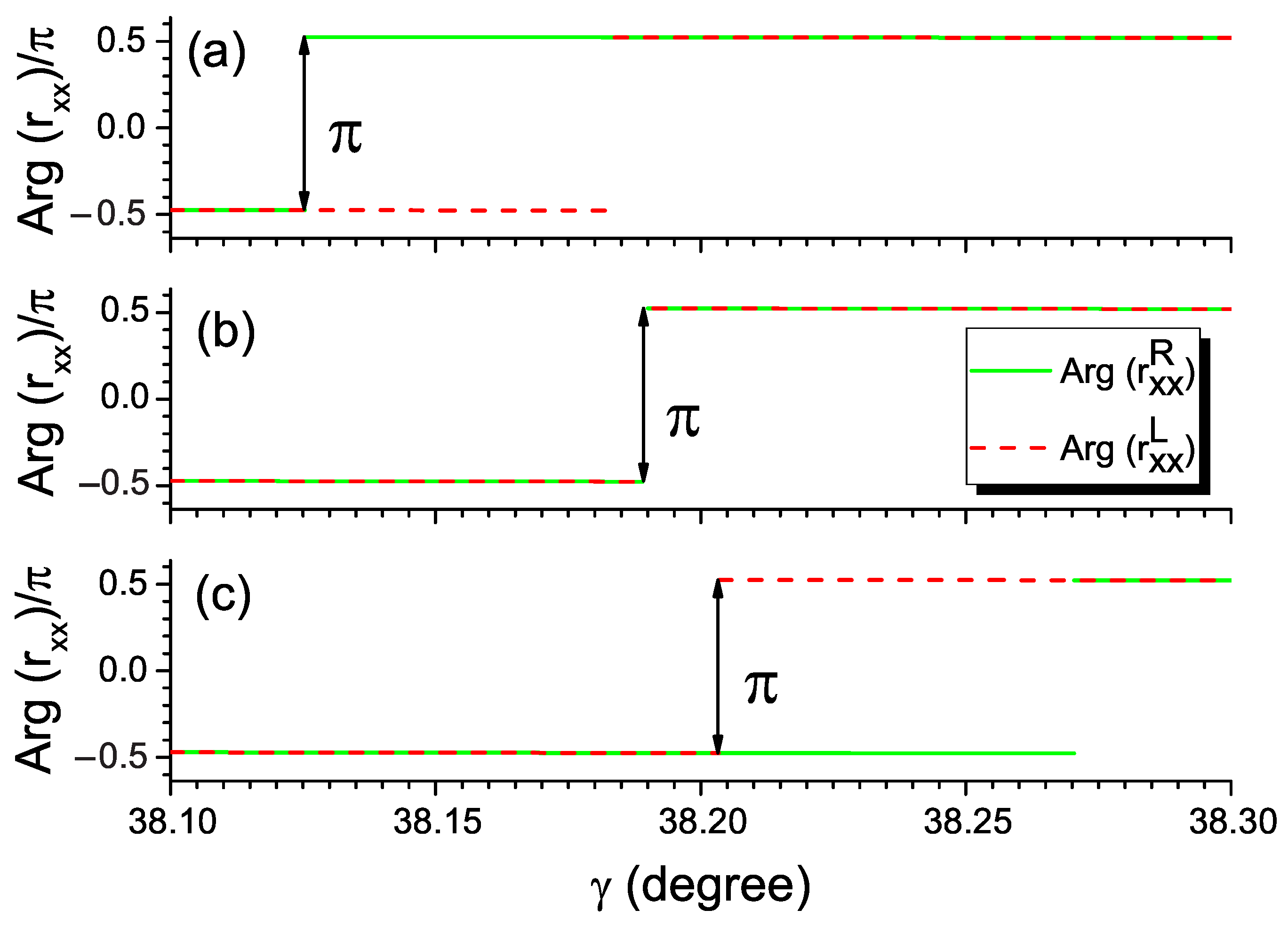

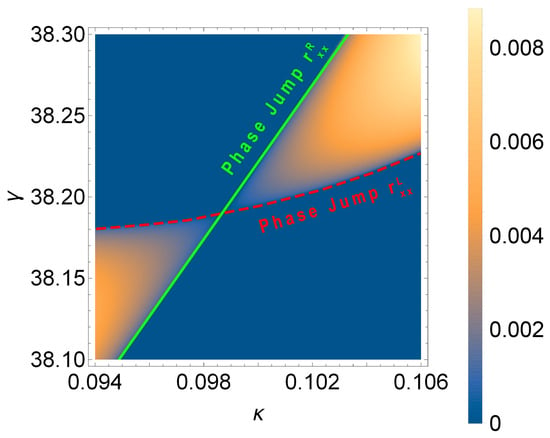

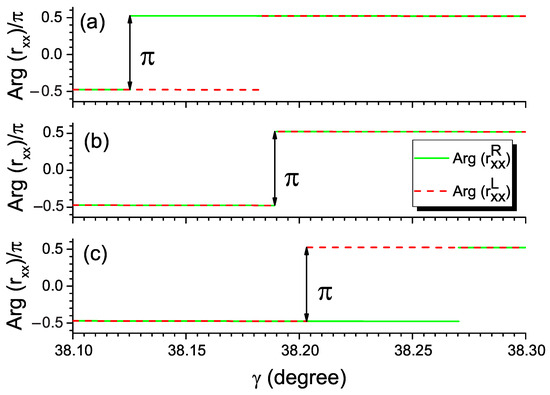

Nevertheless, we can obtain indirect evidence of the topological nature of EPs in our structure by considering exactly these crossings of exceptional lines. For example, in Figure 6, the exceptional lines (solid green and dashed red lines) separate the regions of the -symmetric and -symmetry-broken phases on the plane (, ). As we discussed in Ref. [33] and have shown in Figure 3, the EPs correspond to unity transmission and unidirectional zero reflection. In particular, the exceptional lines in Figure 6 are associated with zeros of the reflection coefficients for light incident from the right () and from the left (), respectively. These reflection zeros can be treated as singular points related to the phase indeterminacy or phase jump. To study the behavior of the reflection phase when crossing the exceptional line, we change the angle for the fixed non-Hermiticity values (vertical lines in Figure 6). The reflection phases for both reflection coefficients and at and are demonstrated in Figure 7a and Figure 7c, respectively. The phases of both reflection coefficients experience a jump on the corresponding exceptional lines that depend on the non-Hermiticity value. The value of this phase jump equals exactly , which is the value of the topological phase accumulated as a result of encirclement around EPs.

Figure 6.

Density plot of the absolute value of the eigenvalue magnitude logarithm as a function of and at μm.

Figure 7.

Phase of the amplitude reflection coefficient as a function of at (a) , (b) , and (c) .

The exceptional lines in Figure 6 intersect at the so-called double EP, representing the degenerate point of a vanishing -symmetry-broken region (see the details in Ref. [34]). The double EP is the point of unit transmission and zero reflection for both directions. The double EP point corresponds to for the system in question. The phase jumps of for both amplitude reflection coefficients occur at the same angle in the double EP, as seen in Figure 7b.

So, the phase jump observed at the EPs is indirect evidence of their nontrivial topology. The same phase jump also emerges when crossing the caustics (focal lines) [37]. This brings EPs and caustics together, which is all the more justified, since the latter is classified within the catastrophe theory used for interpreting the EPs [38]. For instance, one of the frequently encountered caustic forms is cusps—the features similar to the exceptional nexus observed when two exceptional lines converge at an EP of the third order [39,40].

Finally, we propose exploiting the phase jumps at the EPs for sensing applications. In fact, the system transferring across the EP may exhibit a large phase variation under small perturbations. The considered multilayer structure is especially convenient for such sensing owing to its relative ease of tuning the EP position through variation of the angle of optical axis orientation or incident angle. As a result, small perturbations in the refractive index or layer thickness, for example, due to temperature or pressure variations, can result in crossing the EP and, hence, registration of the phase jump.

4. Conclusions

To sum up, we have analyzed indirect evidence for topologically nontrivial singularities in layered structures containing anisotropic slabs. We have shown that the EPs in the anisotropic trilayer system are associated with the points of eigenvalues and eigenmodes exchange and simultaneous equal transmission coefficients for two orthogonal polarizations of the incident light. Moreover, the phase jump for the reflection coefficients is reported at the EPs, providing a caustic-like features perspective for sensing applications. We would like to stress that the considered system allows one to reach the EP by manipulating the optical axis orientation of the anisotropic medium, which is quite feasible with electrically tunable liquid crystals.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.V.N.; methodology, D.V.N.; software, M.R.; validation, A.N.; investigation, M.R. and D.V.N.; writing—original draft preparation, M.R. and D.V.N.; writing—review and editing, D.V.N. and A.N.; visualization, M.R.; supervision, D.V.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Basics of the Operator Method

In this section, we give a brief description of the evolution operator formalism used in our paper. A more detailed and general description of this approach can be found in Ref. [41] and our previous paper [33]. For a monochromatic plane wave propagating through an anisotropic slab, we can write

where , , , and are the strengths of electric and magnetic fields, electric displacement, and magnetic induction vectors, respectively; is the wave frequency; is the dielectric permittivity tensor; and is the magnetic permeability tensor.

The wave vector of the obliquely incident wave can be decomposed into the tangential () and longitudinal () components, where is the wave number in vacuum, is the vector in the plane of incidence, and is the unit vector normal to the slab interfaces. Due to the translation invariance in the plane , we can only deal with the tangential field components, written in the form of the four-component vector as , where and , is the projector onto the plane orthogonal to , is the three-dimensional unit tensor, T stands for the transpose operation, and ⊗ stands for the tensor product, so that , . Then, the Maxwell equations can be represented as a single equation for the vector ,

where is a block matrix,

For anisotropic media described by the material Equation (A1), the blocks , , , and are

where is the antisymmetric tensor dual to , , , , and † stands for Hermitian conjugate.

For a homogeneous anisotropic medium, the general solution to Equation (A2) can be described in terms of the evolution operator , so that

where is the field at the initial position . The same logic applies to the multilayer structures. The field transmitted by the stack of N layers reads as

The spatial evolution operator can be used further to represent the Fresnel transmission and reflection operators (matrices) as

Here, is the surface impedance tensor of the input isotropic medium, defined as

Similar expression is valid for the surface impedance tensor of the output medium . In the diagonal reflection (transmission) operator, the first diagonal element is a reflection (transmission) coefficient for the TE-polarized wave, whereas the second diagonal element is that for the TM-polarized wave. Nondiagonal terms in and correspond to the cross-polarized reflection and transmission. This approach allows us to take into account polarization transformations in anisotropic media.

References

- Ashida, Y.; Gong, Z.; Ueda, M. Non-Hermitian physics. Adv. Phys. 2020, 69, 249–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.; El-Ganainy, R.; Ge, L. Non-Hermitian photonics based on parity-time symmetry. Nat. Photonics 2017, 11, 752–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Ganainy, R.; Makris, K.G.; Khajavikhan, M.; Musslimani, Z.H.; Rotter, S.; Christodoulides, D.N. Non-Hermitian physics and symmetry. Nat. Phys. 2018, 14, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novitsky, D.V.; Novitsky, A.V. Exceptional points. In All-Dielectric Nanophotonics; Shalin, A.S., Canós Valero, A., Miroshnichenko, A., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024; pp. 213–242. [Google Scholar]

- Miri, M.-A.; Alu, A. Exceptional points in optics and photonics. Science 2019, 363, eaar7709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiersig, J. Review of exceptional point-based sensors. Photonics Res. 2020, 8, 1457–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Liang, Z.; Hu, J.; Zhou, P.; Liu, L.; Hu, G.; Wang, W.; Ye, M. Sensing Applications of -Symmetry in Non-Hermitian Photonic Systems. Adv. Quant. Technol. 2025, 8, 2400349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, B.; Chen, H.-Z.; Ge, L.; Berini, P.; Ma, R.-M. Parity–Time Symmetry Synthetic Lasers: Physics and Devices. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2019, 7, 1900694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longhi, S. -symmetric laser absorber. Phys. Rev. A 2010, 82, 031801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novitsky, D.V. CPA-laser effect and exceptional points in -symmetric multilayer structures. J. Opt. 2019, 21, 085101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longhi, S. Phase transitions and virtual exceptional points in quantum emitters coupled to dissipative baths. J. Appl. Phys. 2025, 138, 184401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parto, M.; Liu, Y.G.N.; Bahari, B.; Khajavikhan, M.; Christodoulides, D.N. Non-Hermitian and topological photonics: Optics at an exceptional point. Nanophotonics 2021, 10, 403–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, X.; Hua, J.; Lei, D.; Lu, M.; Chen, Y. Topological physics of non-Hermitian optics and photonics: A review. J. Opt. 2021, 23, 123001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mailybaev, A.A.; Kirillov, O.N.; Seyranian, A.P. Geometric phase around exceptional points. Phys. Rev. A 2005, 72, 014104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dembowski, C.; Gräf, H.-D.; Harney, H.L.; Heine, A.; Heiss, W.D.; Rehfeld, H.; Richter, A. Experimental Observation of the Topological Structure of Exceptional Points. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2001, 86, 787–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzdin, R.; Mailybaev, A.; Moiseyev, N. On the observability and asymmetry of adiabatic state flips generated by exceptional points. J. Phys. A 2011, 44, 435302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milburn, T.J.; Doppler, J.; Holmes, C.A.; Portolan, S.; Rotter, S.; Rabl, P. General description of quasiadiabatic dynamical phenomena near exceptional points. Phys. Rev. A 2015, 92, 052124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doppler, J.; Mailybaev, A.A.; Böhm, J.; Kuhl, U.; Girschik, A.; Libisch, F.; Milburn, T.J.; Rabl, P.; Moiseyev, N.; Rotter, S. Dynamically encircling an exceptional point for asymmetric mode switching. Nature 2016, 537, 76–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, J.W.; Choi, Y.; Hahn, C.; Kim, G.; Song, S.H.; Yang, K.-Y.; Lee, J.Y.; Kim, Y.; Lee, C.S.; Shin, J.K.; et al. Time-asymmetric loop around an exceptional point over the full optical communications band. Nature 2018, 562, 86–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, X.; Qi, H.; Wang, Z.; Hu, X.; Lu, C. Topological Photonic Chiral Mode Converters. Laser Photonics Rev. 2024, 18, 2301315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, A.; Wang, J.; Alù, A.; Chen, L. Multi-State Chiral Switching Through Adiabaticity Control in Encircling Exceptional Points. Laser Photonics Rev. 2025, 19, e00135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Li, M.; Wang, R.; Chen, Y.; Ren, X.; Yan, L.; Li, Q.; Gong, Q.; Li, Y. Dynamically encircling exceptional points for robust eigenstate generation and all-optical logic operations in a three-dimensional photonic chip. Phys. Rev. Res. 2024, 6, 013203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.; Chen, T.; Tang, X.; Zhang, X. Topologically protected entanglement switching around exceptional points. Light Sci. Appl. 2024, 13, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guria, C.; Zhong, Q.; Ozdemir, S.K.; Patil, Y.S.S.; El-Ganainy, R.; Harris, J.G.E. Resolving the topology of encircling multiple exceptional points. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryu, J.-W.; Han, J.-H.; Yi, C.-H. Realization of geometric-phase topology induced by multiple exceptional points. Phys. Rev. A 2024, 110, 052221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Liu, N.; Wu, C.; Chen, G. Dynamical encircling of multiple exceptional points in anti- symmetry system. Opt. Express 2024, 32, 21616–21628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, S.; Wang, Z. Edge States and Topological Invariants of Non-Hermitian Systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2018, 121, 086803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.H.; Thomale, R. Anatomy of skin modes and topology in non-Hermitian systems. Phys. Rev. B 2019, 99, 201103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wei, Z. Non-Hermitian Skin Effect in Non-Hermitian Optical Systems. Laser Photonics Rev. 2025, 19, 2400099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashemi, A.; Pereira, E.L.; Li, H.; Lado, J.L.; Blanco-Redondo, A. Observation of non-Hermitian topology from optical loss modulation. Nat. Mater. 2025, 24, 1393–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, Z.; Wong, B.T.T.; Hu, J.; Yang, Y. Synthetic Non-Abelian Gauge Fields for Non-Hermitian Systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2024, 132, 043804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Mao, Y.-L.; Chen, H.; Yang, K.-X.; Li, L.; Yang, B.; Li, Z.-D.; Fan, J. Observation of Non-Hermitian Edge Burst Effect in One-Dimensional Photonic Quantum Walk. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2024, 132, 203801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramanovich, M.; Novitsky, A.; Bobrovs, V.; Shalin, A.S.; Novitsky, D.V. Exceptional points in -symmetric layered structures with an anisotropic defect. Phys. Rev. B 2024, 110, 195423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramanovich, M.; Novitsky, D.V. Double exceptional points in -symmetric structures with an anisotropic layer. Phys. Rev. B 2025, 112, 045401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tkachenko, V.; Abbate, G.; Marino, A.; Vita, F.; Giocondo, M.; Mazzulla, A.; Ciuchi, F.; De Stefano, L. Nematic liquid crystal optical dispersion in the visible-near infrared range. Mol. Cryst. Liq. Cryst. 2006, 454, 263/[665]–271/[673]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, L.; Chong, Y.D.; Stone, A.D. Conservation relations and anisotropic transmission resonances in one-dimensional -symmetric photonic heterostructures. Phys. Rev. A 2012, 85, 023802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbero, S. Between light and shadows—A brief history of caustics: Retrospective. J. Opt. Soc. Am. A 2025, 42, 1055–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longhi, S. Exceptional points and photonic catastrophe. Opt. Lett. 2018, 43, 2929–2932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, W.; Jiang, X.; Ding, K.; Xiao, Y.-X.; Zhang, Z.-Q.; Chan, C.T.; Ma, G. Exceptional nexus with a hybrid topological invariant. Science 2020, 370, 1077–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hlushchenko, A.V.; Novitsky, D.V.; Shcherbinin, V.I.; Tuz, V.R. Multimode -symmetry thresholds and third-order exceptional points in coupled dielectric waveguides with loss and gain. J. Opt. 2021, 23, 125002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkovsky, L.M.; Furs, A.N. Operator Methods to Describe Optical Fields in Complex Media; Belaruskaya Navuka: Minsk, Belarus, 2003. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.