Abstract

A reflective all-fiber optical current transformer based on a spatial non-reciprocal phase modulation technique is investigated by theoretical analysis and experimental measurement. The modulation unit, composed of a phase delay wave plate (LiNbO3) and two Faraday rotators, achieves flexible frequency adjustment by converting modulation from the time domain to the spatial domain. Therefore, the avoidance of the impact caused by delay coils is achieved in principle. The absence of intrinsic frequency limitations eliminates the demand for precise timing control in demodulation, thereby simplifying the demodulation circuit and reducing the cost and size of the transformer. In previous studies, redundancies were identified in the optical path coupling devices. The half-wave voltage of the modulator is excessively high, and its size is considerable due to constraints inherent in the manufacturing process. The measurement range is within 1800 A. The scheme simplifies some optical path components. By optimizing the phase delay wave plate, the half-wave voltage of the modulator is significantly reduced by a factor of 150. Experimental results demonstrate that the current transformer exhibits excellent detection consistency within the rated current range of 30–3600 A (1–120%), the response time is within 3 ms, and the measurement error and peak error reach 0.052% and 0.127%. This configuration provides a novel option for the design and practical application of all-fiber optical current transformers.

1. Introduction

The establishment of power grids operating at elevated voltage and current levels has led to a growing demand for upgrades within the power metering industry [1]. Currently, substation systems predominantly utilize electromagnetic current transformers [2]. In contrast, all-fiber optical current transformers (AFOCT) are witnessing a growing adoption owing to their remarkable capability to accurately measure both direct current (DC) and alternating current (AC) signals. This capability encompasses superior insulation properties, robust immunity to electromagnetic interference, large dynamic range, wide frequency bandwidth, compact size, and enhanced security [3,4,5,6]. Consequently, AFOCT meets the evolving demands of power systems with respect to digitalization, intelligence, and networking. It has emerged as the preferred choice for contemporary signal acquisition devices within digitally transformed substations.

AFOCT employs polarization-maintaining fiber, such as Lo-Bi fiber or spun fiber, as the fiber sensing head and operates based on the Faraday magneto-optic effect [7,8,9]. These devices measure the angle of Faraday rotation induced by the magnetic field to ascertain the magnitude of the current [10]. In recent years, researchers around the globe have undertaken extensive investigations into AFOCT. Their efforts are primarily directed towards minimizing environmental sensitivity, broadening dynamic range and bandwidth, enhancing measurement precision, and improving long-term operational stability [11,12,13]. Researchers investigate the various factors contributing to the temperature dependence of the interferometric fiber-optic current sensors [14,15,16,17,18]. In particular, the research focuses on the contributions from the fiber retarder at the entrance of the fiber coil, the birefringence of the spun fiber, and the Faraday effect. The fiber retarder at the fiber coil entrance represents a critical constraint that profoundly affects environmental sensitivity. When the delay coil is positioned prior to the interference point, it inevitably introduces linear birefringence due to stress fields, which can compromise system stability and incur additional volume and cost [19]. Furthermore, discrepancies between the length of the fiber retarder coil and the modulation signal frequency may adversely affect the output phase shift of the traditional modulator, leading to a reduction in system accuracy. Therefore, the frequencies of both the modulated signal and the demodulated signal are critical factors in the process of signal detection [20].

This article proposes a novel phase modulation scheme for optic current transformers. The phase modulation technique based on transition time is inherently constrained by the intrinsic frequency and necessitates additional delay coils to achieve the required time delay for modulation. Polarization-maintaining fibers exceeding 200 m are generally employed in conjunction with high-frequency modulation signals. The innovative phase modulation scheme fundamentally overcomes the limitations imposed by intrinsic frequency on the system and does not require delay coils, thereby offering enhanced flexibility in sensitivity and dynamic range. There is no necessity to employ an excessively high frequency for the modulation signal. Even if the modulation signal is a sawtooth wave with a frequency of only 200 Hz, it is possible to achieve a satisfactory and stable demodulation effect. It simplifies the signal demodulation technique, enhances reliability and accuracy, and reduces costs. Utilizing the spatial phase modulation technique, the AFOCT can achieve compliance with the special-purpose current transformer standard at the 0.2S level as specified in the Chinese national standards within the required operational range. The response time is around 2–3 ms. When the current is adjusted to 20%, 100%, and 120% of the rated primary current, the average measurement error of the transformer is approximately 0.106%. The linear regression R2 of the AFOCT output Fit curve is 1, with a linear slope of 0.999 and a zero-point deviation of 0.552, indicating that the prototype has good measurement consistency. When the rated primary current reaches 120%, the peak error is only about 0.127%. This approach provides valuable insights and practical applications for the design and implementation of AFOCT systems.

2. Principle and Analysis

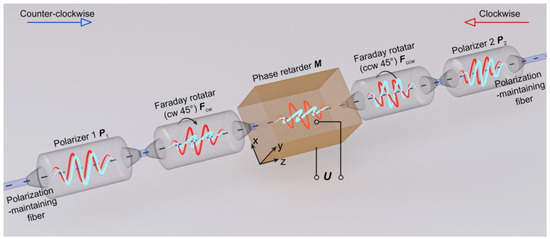

2.1. Spatial Non-Reciprocal Phase Modulator

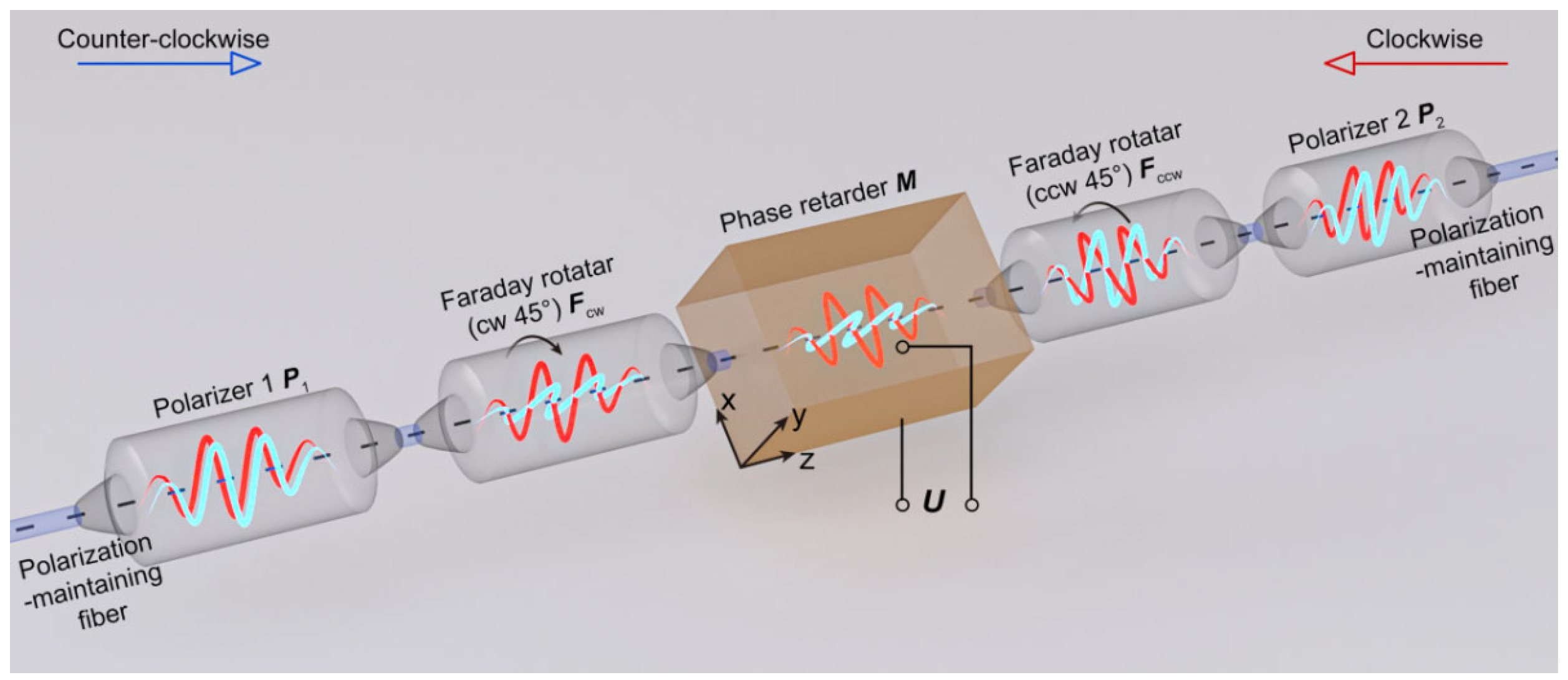

The primary structure of the spatial non-reciprocal phase modulator is to place a phase delay wave plate between the Faraday rotator with clockwise rotation of 45° and counterclockwise rotation of 45°. The optical axis direction of the simultaneous phase delay wave plate is perpendicular to the transmission direction of the incident linearly polarized light. Phase delay wave plates can be made of LiNbO3 crystal or a Y-waveguide phase modulator fabricated from LiNbO3 crystal, etc. [21,22,23]. As shown in Figure 1, without changing the polarization state of the linearly polarized light transmitted in opposite directions, the two light waves pass through the fast and slow axes (or the electro-induced optical axes) with different refractive indices, respectively. The π/2 phase delay is introduced in the form of a refractive index difference, thereby making the Sagnac interference light intensity distribution a sine function. Traditional modulators limit the selection of modulation frequency. Because the intrinsic frequency and transit time of AFOCT are the core parameters for its signal processing and accuracy control. The modulation frequency of the modulator is usually set to be equal to the intrinsic frequency or its half value. At this frequency point, the efficiency of signal processing is highest, which is beneficial for improving signal-to-noise ratio and detection accuracy. The change in transit time (such as caused by temperature fluctuations) can directly lead to intrinsic frequency drift. If the modulation frequency cannot synchronously track this change, it will introduce output noise, zero bias error, and scale factor degradation, seriously damaging the instantaneous and long-term accuracy of AFOCT. But the spatial non-reciprocal phase modulator completely avoids the setting of the intrinsic frequency and does not involve the following of the modulation frequency.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of a spatial non-reciprocal phase modulator.

In contradistinction to the phase modulation technique with time delay, this scheme attains phase modulation by leveraging the inherent characteristics of the device. Consequently, there is no requirement to consider the transit time τ in the demodulation technique, and the transformer is not constrained by the Sagnac intrinsic frequency. Thus, it is easier to achieve a balance between the dynamic range and accuracy requirements. In Figure 1, the phase modulator is composed of a polarizer P1, a Faraday rotator Fcw (rotating 45°clockwise), a phase delay wave plate M, a Faraday rotator Fccw (rotating 45°counterclockwise), and a polarizer P2.

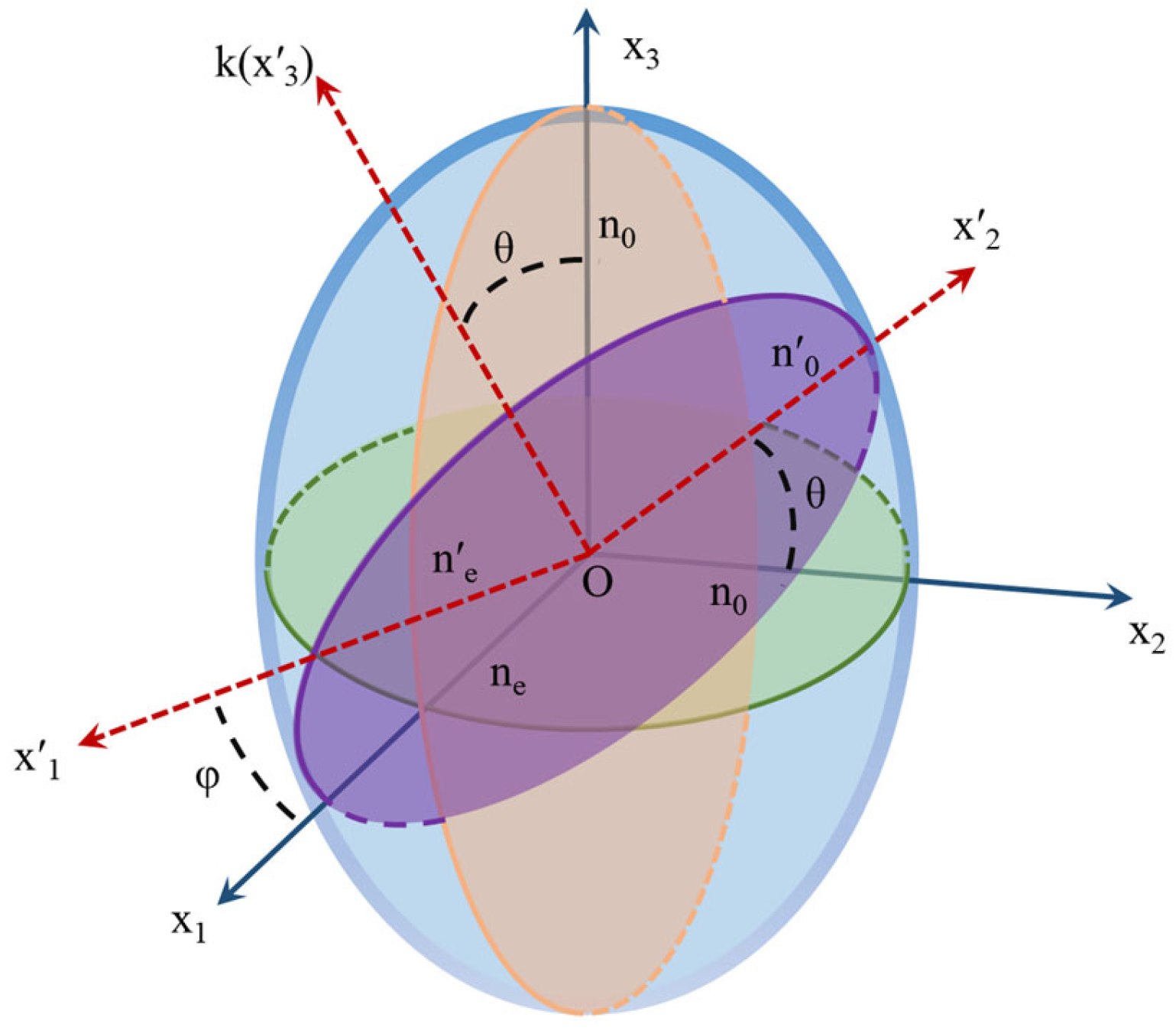

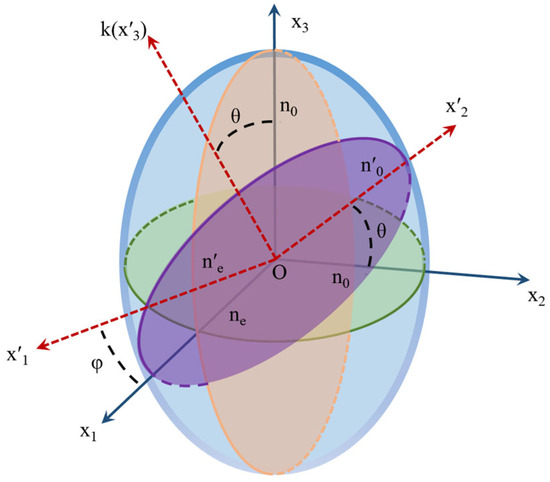

The spatial non-reciprocal phase modulation technique can be analyzed based on the concept of the refractive index ellipsoid [24]. The LiNbO3 crystal belongs to a negative uniaxial crystal, with its principal refractive indices n2 = n3 = no and n1 = ne < no. Suppose the angle between a plane light wave k passing through the crystal and the x1 axis is φ, and the angle between k and the x3 axis is θ. Therefore, the intersection line of the plane perpendicular to the light wave k and passing through the center of the ellipsoid must be an ellipse. Taking the (k, x3) plane as the x2Ox3 plane, a new coordinate system O-x′1x′2x′3 is established, as shown in Figure 2. The cross-section x′1Ox′2 can be written as

Figure 2.

The refractive index ellipsoid of a negative uniaxial crystal.

After sorting, the intercept equation can be obtained as

In the new coordinate system, the refractive index of ordinary light and the refractive index of extraordinary light are expressed as

For a negative uniaxial crystal, the optical axis is parallel to the crystal surface. The direction of the light vector that propagates faster is the fast axis, and the direction of the light vector that propagates slower is the slow axis. When no > ne, the e light leads, and the fast axis is in the direction of the e vector.

When the incident light wave k is perpendicularly incident along the crystal surface, the vibration direction of one of the two linearly polarized lights in the normal direction will coincide with the x3 axis. At this time, the refractive index will be the same as that of the ordinary light, that is, n′o (θ) = no. However, the refractive index n′e (φ) of the other linearly polarized light of the incident light wave k will be affected by the angle φ between x1 and x′1. The additional phase delay φ1 of the linearly polarized light that rotates clockwise through the optical rotator and enters the slow axis of the crystal is expressed as

The counterclockwise transmitted linearly polarized light, after being rotated by the optical rotator, enters the fast axis of the crystal, that is, n′e (φ)= ne. The additional phase delay φ2 is expressed as

Therefore, after the linearly polarized light transmitted in the opposite direction passes through the fast and slow axes of the crystal, respectively, a non-reciprocal phase shift is generated between the two coherent light beams, and the additional phase change is calculated as

LiNbO3 crystal exhibits the generation of electrically induced optical axes in the presence of an electric field environment. Accordingly, the application of an appropriate voltage to the LiNbO3 crystal or Y-waveguide phase modulator fabricated from LiNbO3 crystal enables precise control over the phase difference, achieving a value of π/2.

2.2. Optimization of Phase Delay Wave Plate

LiNbO3, functioning as a phase-delayed wave plate, is classified as an electro-optic crystal. When subjected to a strong external electric field, its birefringent properties undergo alterations, leading to the formation of an induced optical axis. The change in refractive index associated with this induced optical axis is directly proportional to the first power of the applied electric field (the Pockels effect). Consequently, by modulating the intensity of the electric field, one can manipulate the refractive index difference between two induced optical axes, thereby resulting in a non-reciprocal phase shift. In previous studies on modulation structures utilizing spatial non-reciprocal phase modulation, LiNbO3 crystals are employed with light transmission along the z-direction and electric field transmission along the y-direction [25]. In this paper, we present a dual-polarized waveguide featuring light transmission in the y-direction and electric field transmission in the z-direction.

The varying directions of light transmission and the electric field in LiNbO3 crystals can influence the induced variations in the optical axis as well as the intrinsic birefringence. All potential interactions can be comprehensively analyzed through the linear electro-optic properties of LiNbO3, alongside the concept of the refractive index ellipsoid.

When no electric field is applied, the refractive index ellipsoid of the LiNbO3 crystal is expressed as a rotating ellipsoid

The refractive index Bij is actually the inverse tensor of the relative dielectric constant εij of the crystal, = 1/no2 = , = ne2. When an external electric field is applied, the refractive index ellipsoid changes due to the Pockels effect, expressed in the form of a general refractive index ellipsoid:

B1 = ΔB1 + , B2 = ΔB2 + , B3 = ΔB3 + , B4 = ΔB4, B5 = ΔB5, and B6 = ΔB6. According to the linear electro-optic coefficient matrix of LiNbO3 (3 m crystal type) crystals:

where γij represents the crystal electro-optic coefficient, and Ei represents the electric field intensity. The general expression for the induced refractive index ellipsoid equation of the LiNbO3 crystal under an external electric field can be derived using Equations (8) and (9).

When the external electric field is parallel to the z-axis, Ex = Ey = 0, Equation (10) is expressed as

The absence of a cross term in this equation indicates that when an electric field is applied along the z-direction, the orientation of the induced optical axis of the crystal remains unchanged. Consequently, the refractive index corresponding to the induced optical axis can be expressed as

Therefore, when an electric field is applied in the z-direction, the phase difference induced by the electric field remains consistent regardless of whether light propagates along the x-axis or y-axis. This phase difference is denoted as

where l represents crystal length in the direction of light propagation, d represents crystal thickness in the direction of the electric field, and Uz represents voltage amplitude. Therefore, the half-wave voltage of LiNbO3 with the z-direction applied voltage is

When the external electric field is parallel to the y-axis, Ex = Ez = 0, and Equation (10) can be derived as

The refractive index corresponding to the induced optical axis can be expressed as

The phase difference controlled by the electric field is expressed as

The half-wave voltage of the LiNbO3 crystal with z-direction light transmission and y-direction electric field is expressed as

In practice, γ13, γ22, and γ33 are, respectively, 10 × 10−12 m/V, 6.8 × 10−12 m/V, and 32 × 10−12 m/V. no, ne, and λ are, respectively, 2.21, 2.17, and 1310 nm. lz and ly are, respectively, 4.0 cm and 19.3 cm. dz and dy are, respectively, 26.75 μm and 1.3 cm. By substituting them into Equations (15) and (21), we can calculate that Uπz and Uπy are, respectively, 3.999 V and 601.093 V.

The most significant advantage of the dual-polarized waveguide developed using titanium diffusion technology is that its half-wave voltage is approximately 4 V. In contrast, the half-wave voltage of the LiNbO3 crystal employed in previous studies for z-direction light transmission and y-direction electric field transmission is around 600 V. This represents a reduction in the amplitude requirement for half-wave voltage by a factor of 150. The excessively high half-wave voltage presents safety hazards to the system, which contradicts the core advantages of AFOCT. Additionally, a half-wave voltage in the range of several hundred volts can adversely affect temperature regulation during equipment heating and cooling processes, thereby increasing temperature noise interference on system detection. Furthermore, LiNbO3 crystals previously utilized for z-direction light transmission and y-direction electric field transmission exhibit drawbacks such as large volume and challenges associated with optical axis alignment. The dual-polarized waveguide, featuring light transmission in the y-direction and electric field transmission in the z-direction, as a phase delay wave plate, offers advantages including compactness and lightweight installation, aligning more closely with the developmental needs of AFOCT.

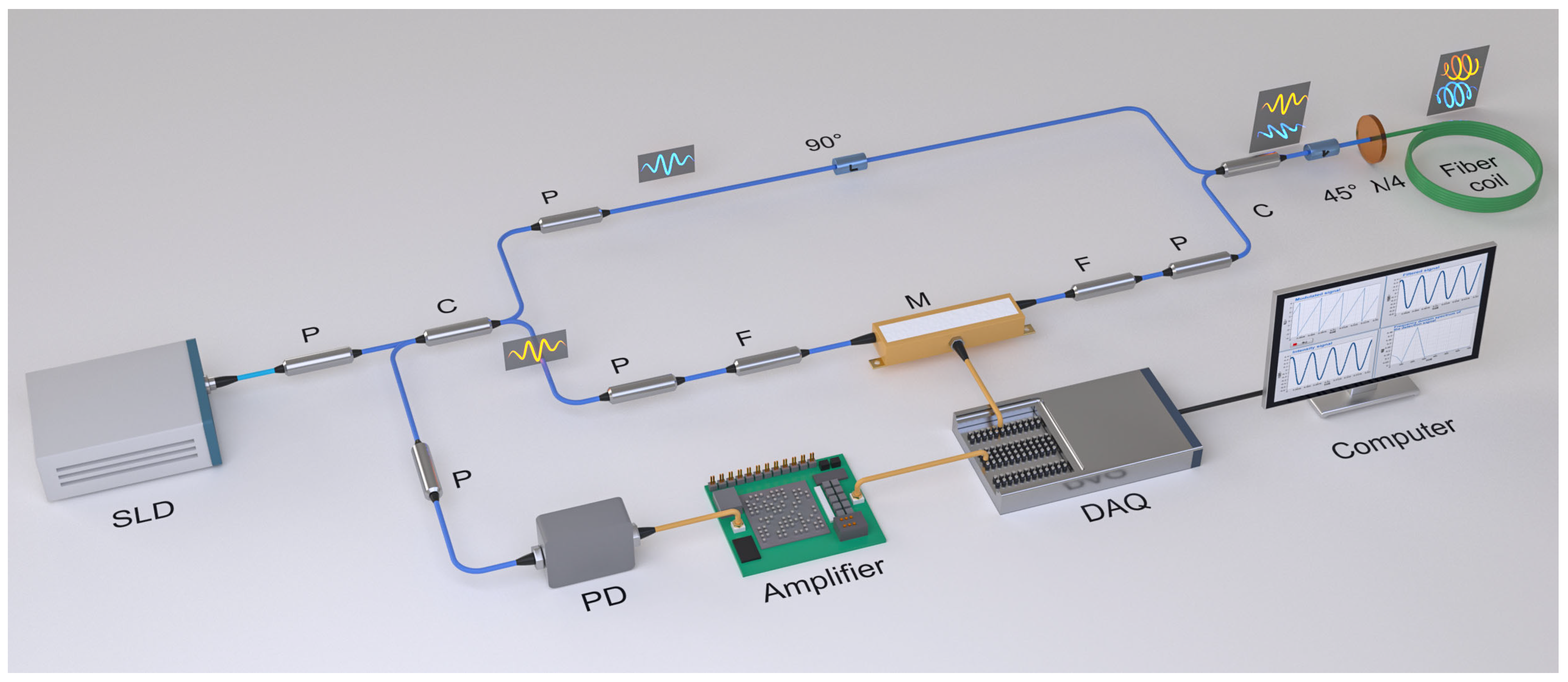

2.3. Structure of AFOCT

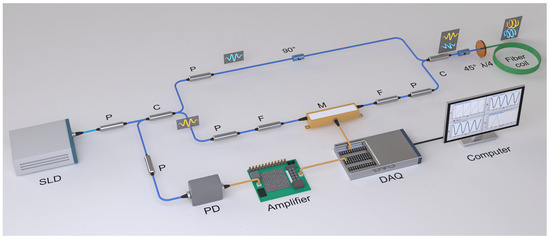

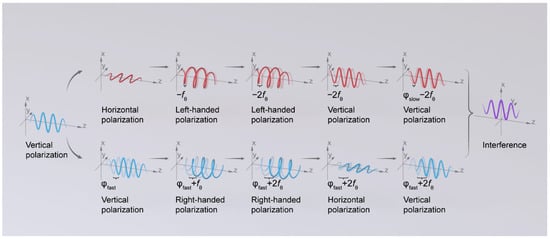

Figure 3 illustrates the comprehensive system architecture of a reflective all-fiber optical current transformer that integrates the spatial non-reciprocal phase modulation technique. The light wave emitted by the SLD light source is subjected to polarization through a polarizer. At this stage, it can be regarded that the polarization state of the light wave is vertically polarized light. The vertically polarized light wave is divided into two equal paths through a 2 × 2 polarization-maintaining fiber coupler. A light wave traversing a 90° fusion point results in a 90° axis alignment, thereby producing horizontally polarized light. The other light wave is introduced into the modulation phase (fast axis) through the spatial non-reciprocal phase modulator, which is vertically polarized light. Afterwards, the two beams of light are coupled into two linearly polarized light beams with perpendicular polarization directions in the polarization maintaining coupler, one is horizontally polarized light, and the other is vertically polarized light. Upon incidence at a 45° fusion point on the λ/4 waveplate, the two orthogonal linearly polarized beams are converted into circularly polarized light components with opposite rotation directions before propagating into the sensing section—one left-handed and the other right-handed.

Figure 3.

Schematic diagram of the structure of the proposed AFOCT.

The Faraday magneto-optical effect refers to the rotation of the polarization plane of linearly polarized light passing through a magneto-optical medium in the horizontal direction of the magnetic field [26]. The rotation angle fθ is proportional to the magnetic field strength, and the relationship between the rotation angle and the magnetic field strength is expressed as

where V represents the Verdet constant. H represents the magnetic field strength. L represents the optical path length. Comparing circularly polarized light and linearly polarized light, their characteristics are slightly different when subjected to a magnetic field. The essence of the Faraday effect lies in the fact that, under the influence of a magnetic field, a magneto-optical medium exhibits distinct refractive indices for circularly polarized light depending on the direction of rotation. Specifically, the phase of circularly polarized light experiences either a leading or lagging change. Wrap N turns of optical fiber around a long wire, where i represents the current flowing through the wire, the magnetic field generated around the wire is given by

By substituting Equation (22), fθ is calculated as

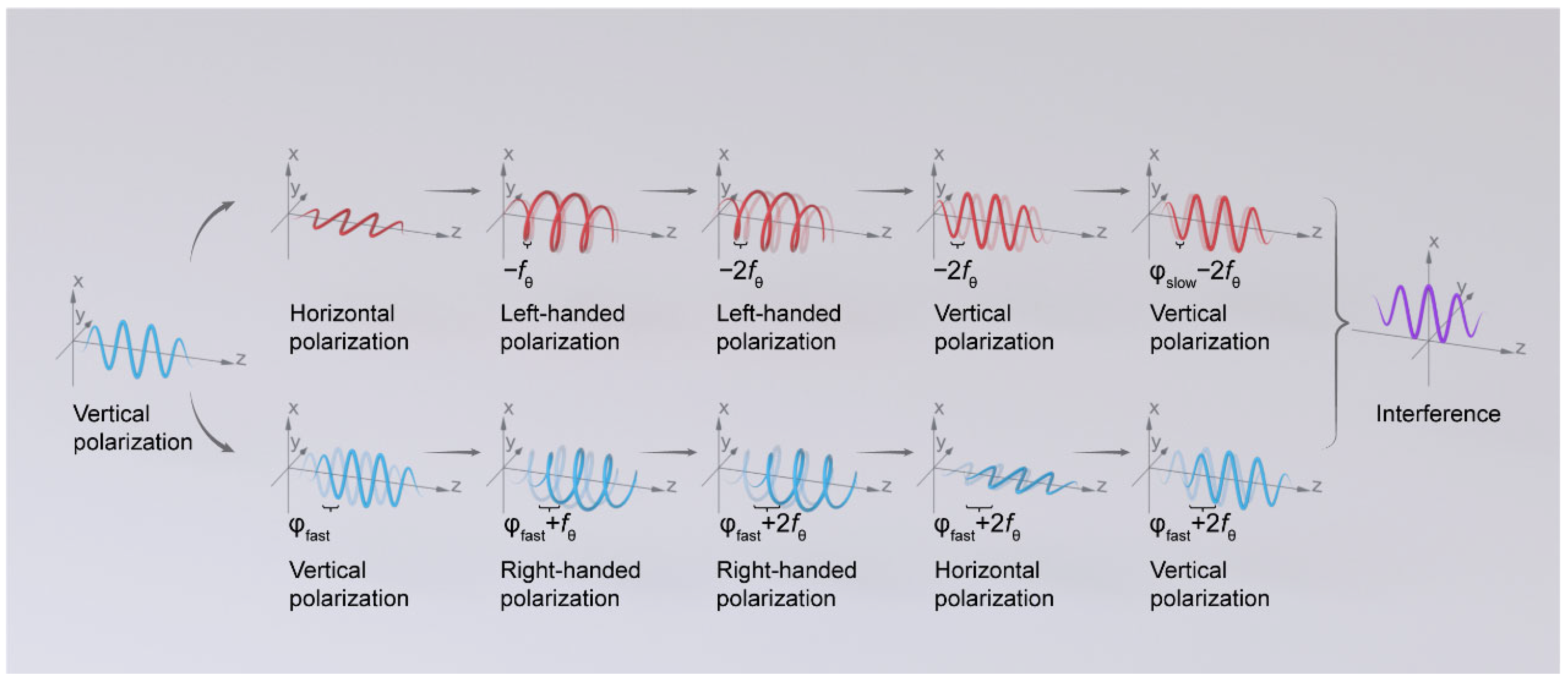

Therefore, the two circularly polarized light waves with opposite rotations entering the sensing part produce a non-reciprocal phase shift, increasing and decreasing by 2fθ. When two beams of circularly polarized light reach the reflection mirror at the end of the fiber ring, the originally left-handed circularly polarized light is converted to right-handed polarization, while the right-handed circularly polarized light is transformed into left-handed polarization. These altered beams then return to the sensing coil, resulting in a total phase shift of 4fθ. Subsequently, the light wave carrying sensing information is converted back into linearly polarized light through a λ/4 waveplate, with one being vertically polarized light and the other being horizontally polarized light with fast axis modulation phase, and the two beams of light have a difference of 4fθ. Vertically polarized light is introduced into the modulation phase (slow axis) via a phase modulator. After the polarizer in each of the two arms eliminates the repeated modulation of linearly polarized light, interference occurs at the coupler. The Faraday phase shift between vertically polarized light modulated by the fast axis and that modulated by the slow axis, which differs by a factor of four, leads to this interference, as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Polarization state diagram of optical path.

2.4. Derivation of Jones Matrix

When discussing the Jones matrix of phase modulators in AFOCT, the reference plane for phase delay is established as the standard reference plane commonly accepted in most literature and textbooks [27,28,29]. The Jones matrix representing the phase delay wave plate is as follows:

where θr denotes the angle between the fast axis of the delay wave plate and the x-axis. The Jones matrix for two polarizers, as well as Faraday rotators with opposite rotation directions, is expressed as

In the formulas, θf represents the rotation angle of the polarization state. When θr = −π/4 and θf = π/4, the matrix of the spatial phase modulator can be represented as a clockwise matrix Mcw and a counterclockwise matrix Mccw in AFOCT:

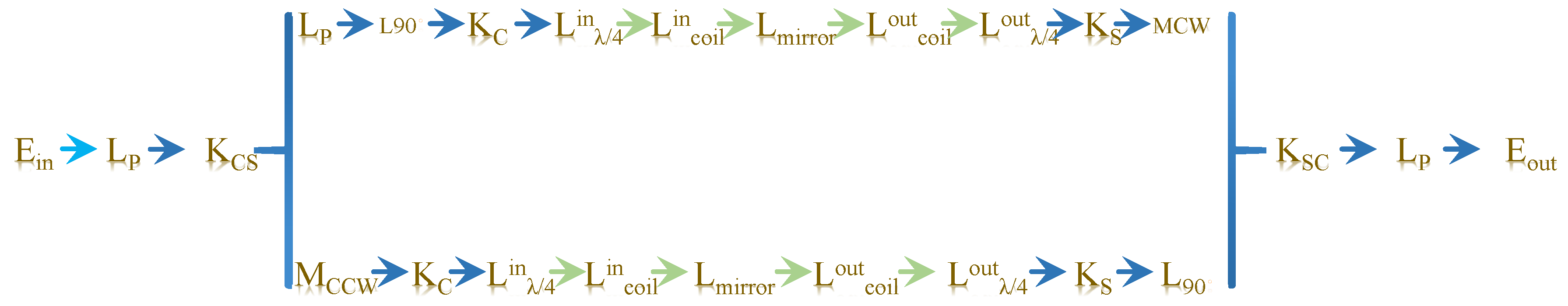

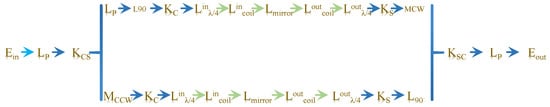

The matrix model of the AFOCT is shown in Figure 5, where Ein is the Jones matrix form of the incident light, Ks/c is the splitting ratio of the 1 × 2 coupler (without considering losses), Ksc/cs is the splitting ratio of the 2 × 2 coupler, LP is the Jones matrix of the polarizer, Lλ/4 is the Jones matrix of the λ/4 waveplate, Lmirror is the Jones matrix of the reflecting mirror, Lcoil is the sensing ring Jones matrix, and L90° is the Jones matrix of the 90° fusion point.

Figure 5.

AFOCT Jones matrix structure diagram.

The Jones matrix expressions for each parameter in the figure are expressed as

Among these components, Ex represents the polarization component along the x-axis, while Ey denotes the polarization component along the y-axis. When the two beams traverse clockwise and counterclockwise through the fiber ring and reach the photodetector, their corresponding light vectors are represented by the clockwise matrix Ecw and the counterclockwise matrix Eccw:

The expression for the final output light intensity, denoted as Iout, is calculated as

Consequently, by demodulating the light intensity signal through an appropriate signal processing technique, the fθ can be extracted, and the corresponding current value can be derived from Equation (24).

3. Experiment and Result

3.1. Current Sensing Experiments

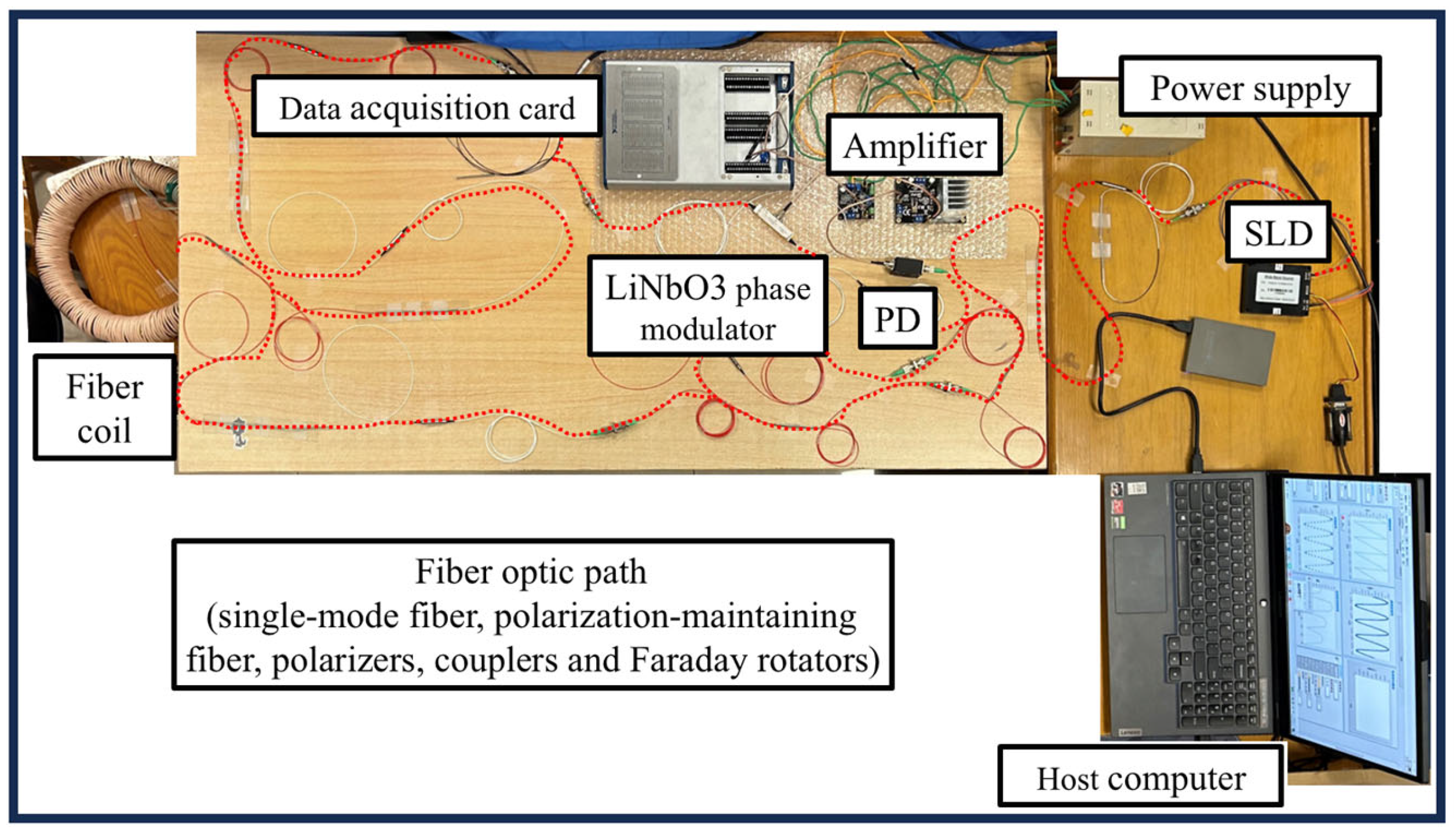

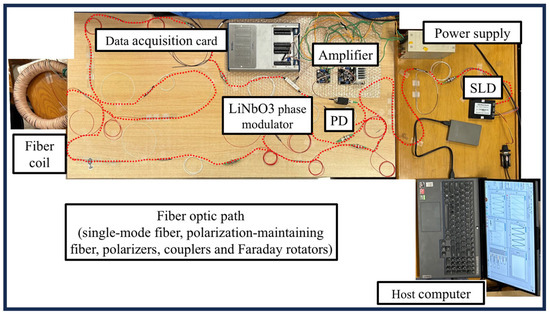

The experiment finalizes the construction of the optical path between the spatially non-reciprocal phase modulator and the reflective fiber current transformer discussed previously. The experiment set-up is equipped with the SLD (Yixun Photon Technology, YXSLD-1310SM-0-FA, Mianyang, China), PD (Thorlabs, DET01CFC, Shanghai, China), and LiNbO3 phase modulator (TJLiniom, PMT1300-P-P-FA-FA, Tianjin, China) and data acquisition card (National Instruments, USB-6353, Shanghai, China). Moreover, polarizers, couplers, and Faraday rotators are purchased from MC Fiber Optics in China Shenzhen. A commercially available amplifier is used to amplify the photoelectric signal collected by PD. The SLD source operates at 1310 nm with an output power of 10 mW. The half-wave voltage of the LiNbO3 dual-polarized waveguide is 4 V. The experimental set-up is shown in Figure 6. When combined with host computer software LabVIEW for signal modulation and demodulation, it forms a complete closed-loop detection device for fiber-optic current transformers. Due to the advantages of the spatial non-reciprocal phase modulation technique, high-frequency signals are not required for the modulated signal. At the same time, the selection of modulation waveforms is also very flexible. Sinusoidal signals, square wave signals, sawtooth wave signals, and triangular wave signals can all be used. The experiment used a 200 Hz sawtooth wave signal as the modulation signal. The functionality of the principal prototype is verified under DC current input through experimental procedures, followed by the completion of performance testing for the principal prototype.

Figure 6.

Experimental set-up of the proposed system.

Although AC current measurement dominates in practical scenarios, the experiment mainly focuses on testing DC current. The reason is that the essential difference between measuring DC and AC lies in the frequency of the signal to be measured. According to the Nyquist–Shannon sampling theorem, the sampling frequency must not be less than twice the highest frequency of the original signal. The phase difference generated by interference light waves due to changes in current is an instantaneous response. The intrinsic frequency and transit time in traditional AFOCT-modulated signals can affect whether they operate at the optimal operating point, thereby affecting accuracy and sensitivity. Therefore, the constraint of measuring high-frequency signals with AFOCT lies in the digital processing part, rather than the limitation of the optical path. The performance of the data acquisition card is the main reason affecting the AC signal in this experiment. The maximum single-channel sampling rate of USB-6353 is 1.25 MS/s, and the maximum value is 1.00 MS/s in multiplexing mode. In addition, the proposed AFOCT avoids the frequency limitation of modulation signals, making its accuracy and other parameters independent of modulation frequency. Therefore, AFOCT achieves flexible frequency adjustment. Although the dual-polarized waveguide can provide a modulation signal with a bandwidth of 100 MHz, the focus is still on the accuracy and other aspects of measuring signals rather than frequency. The final choice is to focus on DC for testing. So as to verify the effect of avoiding the influence of intrinsic frequency on accuracy.

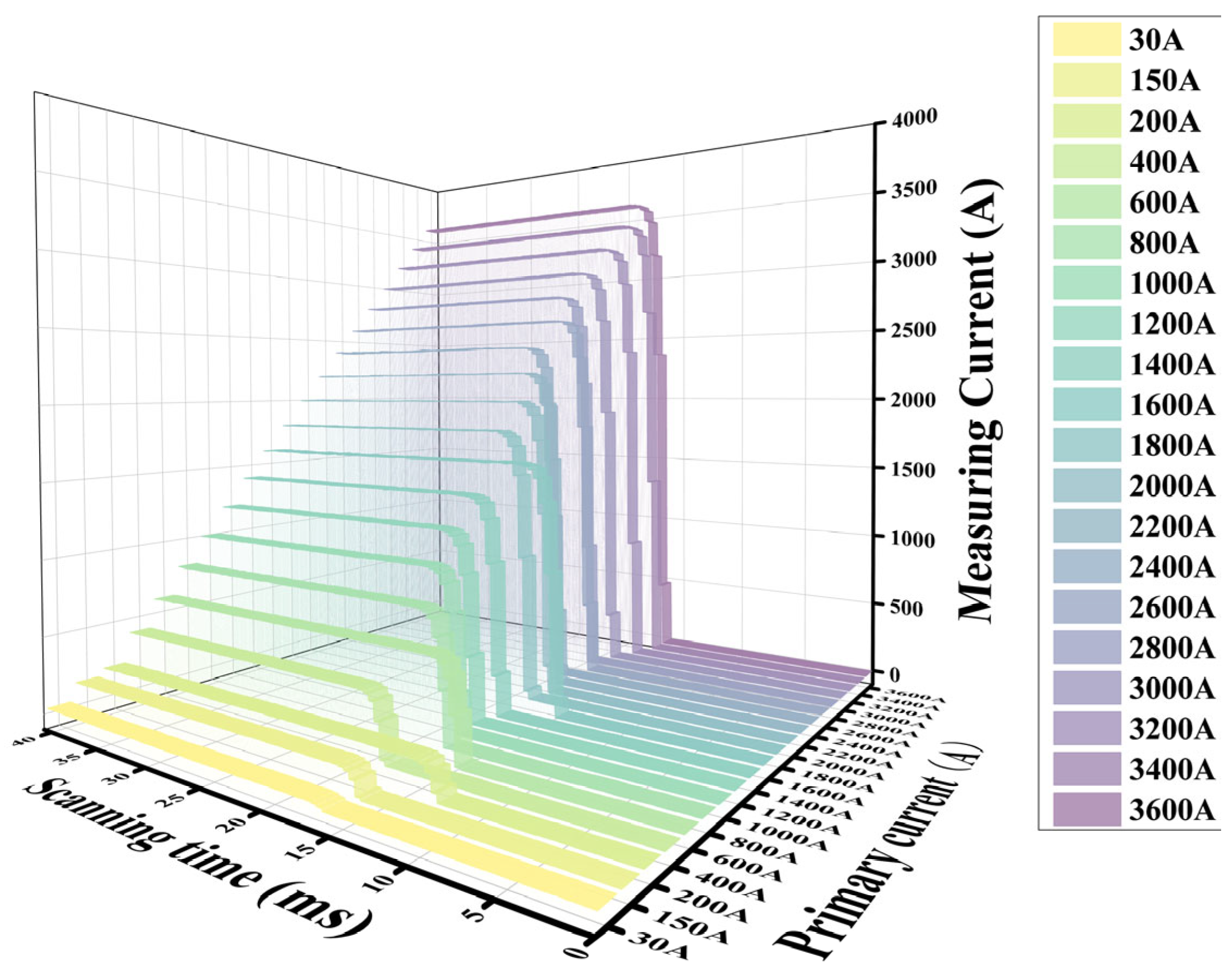

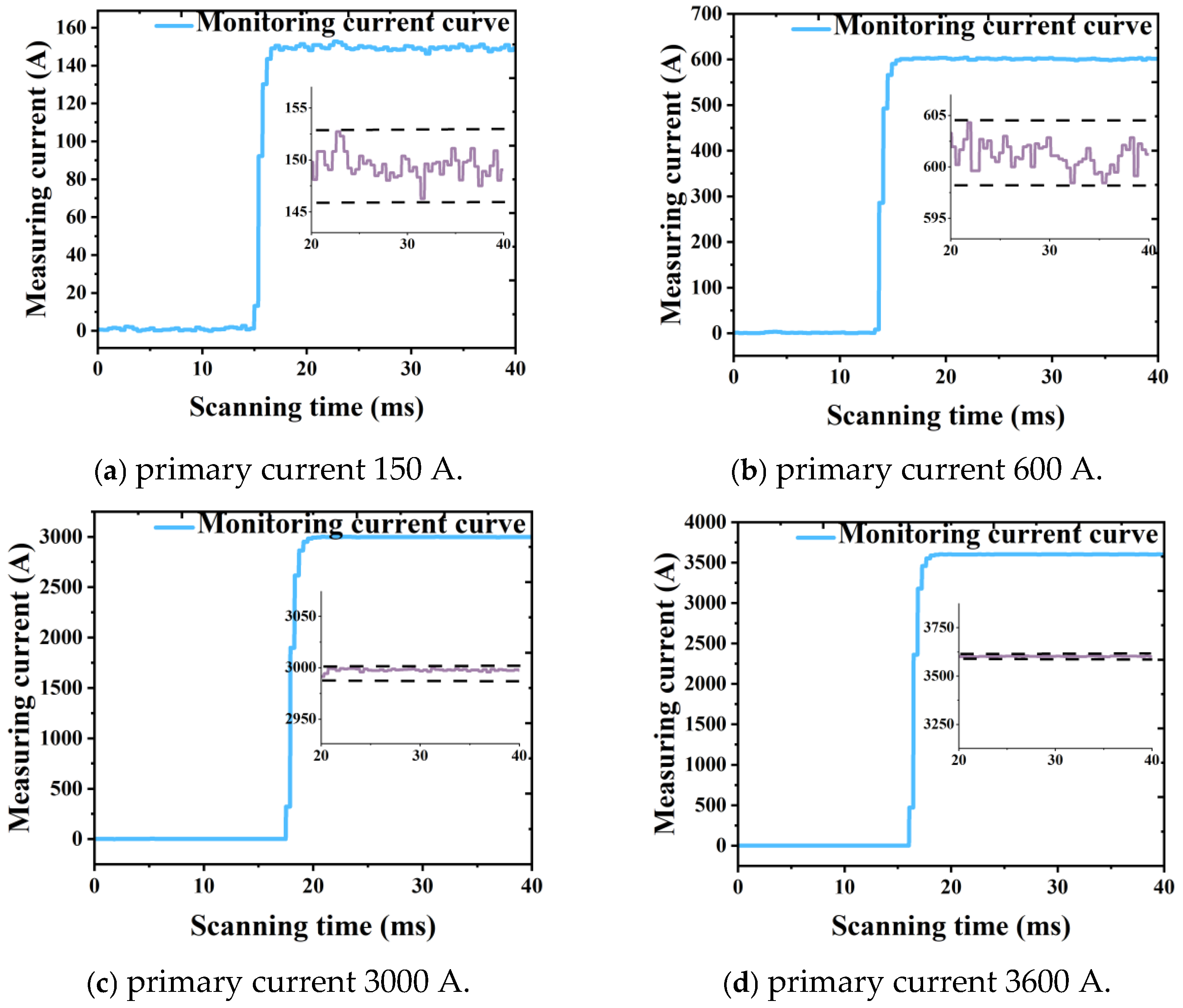

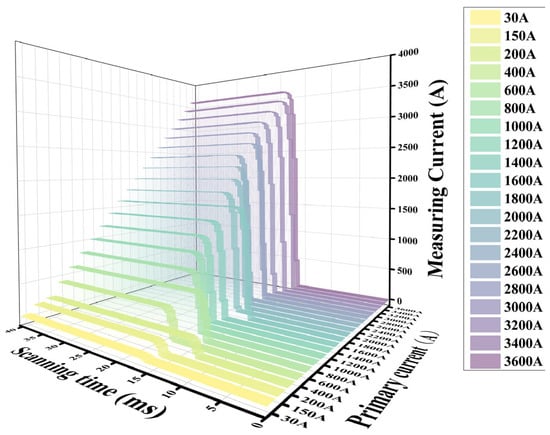

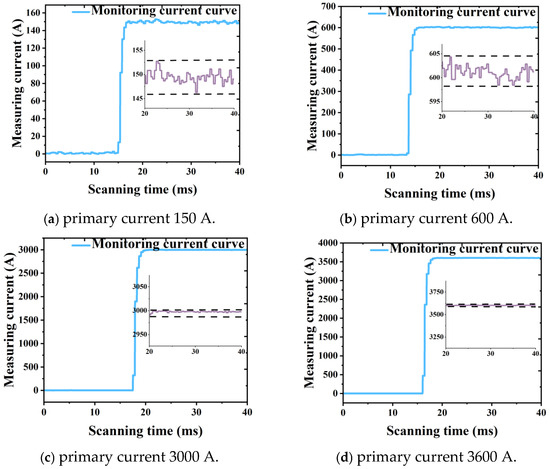

According to the testing conditions mentioned in the relevant standards, a total of 20 groups are conducted in the experimental environment. Except for small currents of 30 A and 150 A, the remaining step sizes are 200 A, covering rated currents (1–120%) to measure DC currents of 30–3600 A. The recorded current magnitude data of the experiment is the current variation graph saved by the LabVIEW host computer program, as shown in Figure 7. The transformer measurement maps for primary currents of 150 A (5%), 600 A (20%), 3000 A (100%), and 3600 A (120%) are given in Figure 8.

Figure 7.

Current monitoring waveform of 30–3600 A.

Figure 8.

Current monitoring waveform of 150 A, 600 A, 3000 A, and 3600 A.

The four sets of detection waveforms presented in Figure 8 exhibit varying degrees of noise, which arises from both circuit noise and measurement noise associated with the sensing fiber ring within the optical path. As the current increases, the amplitude of noise in the detection waveform decreases, resulting in a reduction of the peak-to-peak ratio of the noise relative to the measured current. This results in enhanced accuracy. Throughout the entire AFOCT system, it is observed that circuit-related noise is unrelated to primary current value. Therefore, the result is that the optical noise detected is inversely proportional to the magnitude of the current. This observation aligns with the characteristics of AFOCT designed for high-current sensing applications. In addition, in the 20 sets of detection waveforms shown in Figure 7, the response time is around 2–3 ms, which meets the requirements of relay protection.

The 20 sets of detection waveforms are conducted at a single laboratory temperature. The temperature dependence and long-term stability of AFOCT are key challenges it faces in practical applications, especially when operating over a wide temperature range. Temperature changes can significantly affect the performance of key components in AFOCT, including the phase shift of lithium niobate (LiNbO3) waveguides, leading to an increase in overall ratio error. When the temperature changes, the refractive index of the LiNbO3 waveguide will also change, resulting in additional phase delay or advance when light propagates in the waveguide, that is, thermally induced phase shift. According to the Sellmeier equation of LiNbO3 crystal, the temperature-dependent changes are analyzed as

Therefore, we can quantitatively estimate the influence trend of half-wave voltage on temperature. Due to the influence of half-wave voltage on the setting of the optimal operating point, it will not significantly affect the measurement accuracy within a certain range. As a result, this experiment temporarily does not focus on the stability and reliability of temperature.

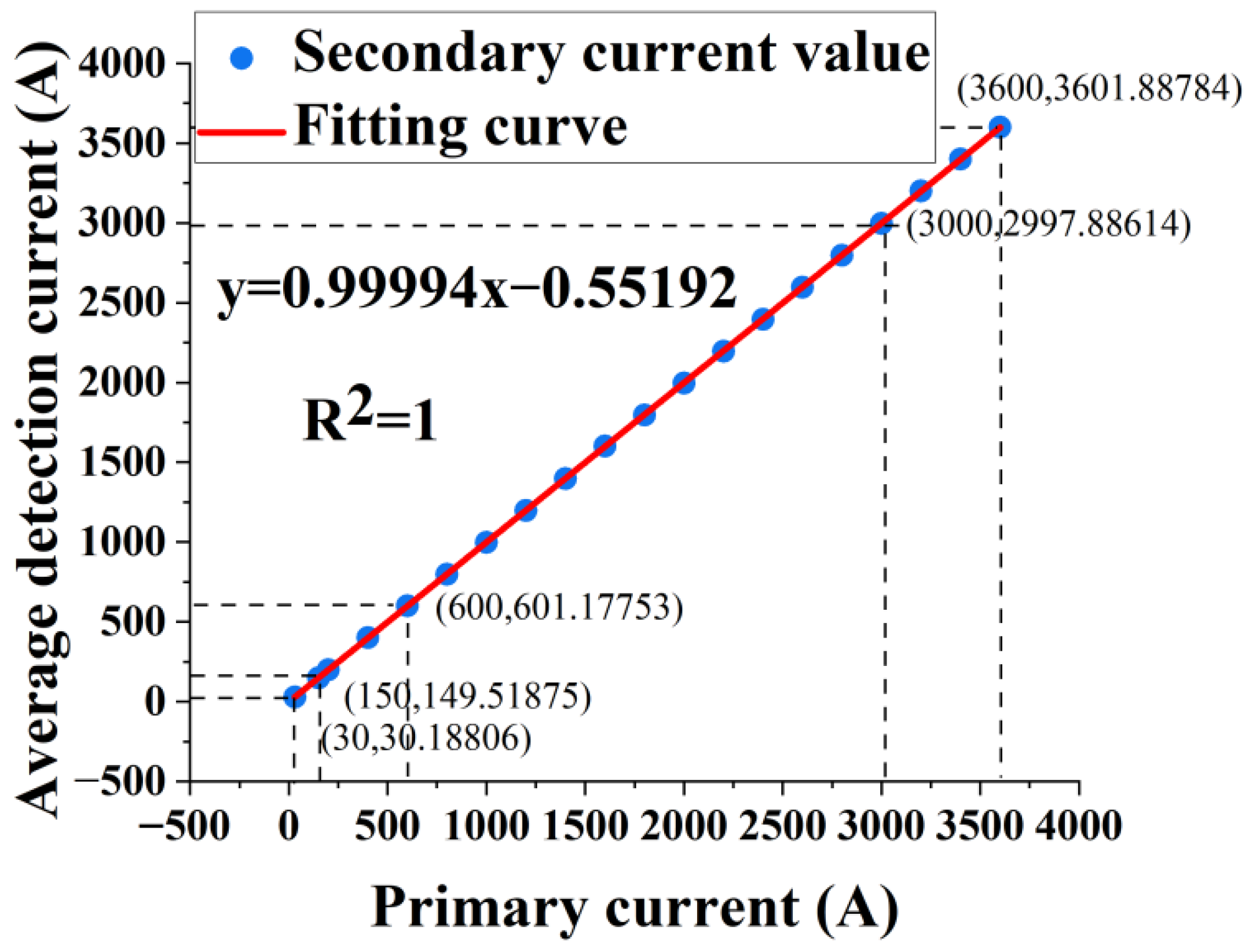

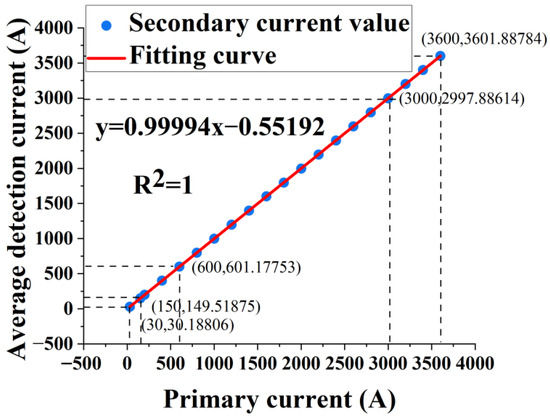

3.2. Linearity

Linearity, δL, commonly referred to as “nonlinear error”, denotes the extent to which the effective input–output characteristic curve of a transformer diverges from the ideal linear input–output characteristic. This deviation is quantified as a percentage of the maximum divergence between the effective input–output characteristic curve and the theoretical input–output characteristic curve relative to the full scale. δL is given as

where YFS represents the range, and ΔLmax represents the maximum error. As illustrated in Figure 9, each discrete point within the figure represents the average magnitude of the detection results corresponding to a specific current. The linear regression R2 of the transformer output fitting curve in the figure is 1, with a linear slope of 0.999 and a zero-point deviation of 0.552, indicating that the prototype has good measurement consistency. Consequently, δL is approximately 0%.

Figure 9.

Output linearity of the AFOCT.

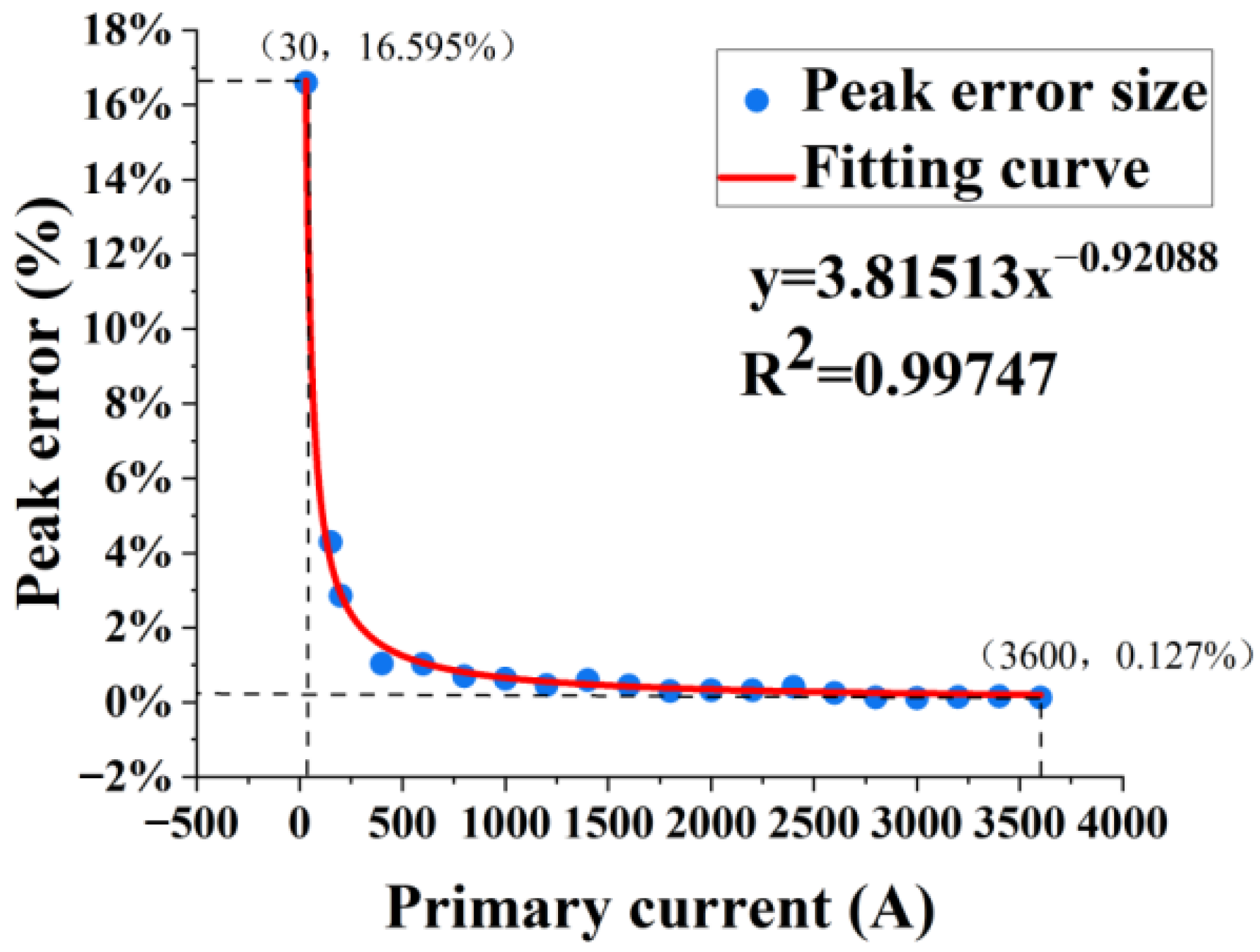

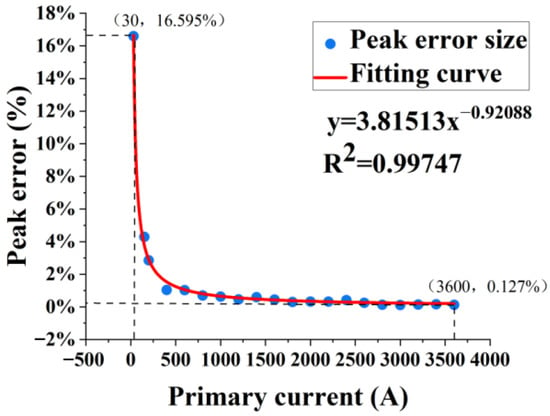

3.3. Peak Error

The peak error is used to represent the maximum error of the instantaneous value of the transformer relative to the rated primary current, which can be expressed as

where Imax represents the maximum detection output at the rated operating point, Imin represents minimum detection output at rated operating point, and IR represents rated primary current size. The peak error diagram of the AFOCT is shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

The peak error diagram of the AFOCT.

Shot noise originates from the quantum randomness of photons arriving during the process of light detection. It is the physical basis that determines the theoretical limit of sensitivity and is an unavoidable noise in any classical optical system. And thermal noise mainly depends on the parameters of the amplifier itself, usually independent of the primary current of the measured signal. For a given amplifier, its equivalent input noise current or voltage is constant within a fixed bandwidth. Other optical interference noise sources include stray light from external light sources, instability of the laser source itself, scattering of optical components, or changes in the optical path caused by environmental vibrations.

When the rated primary current is set at 1%, the maximum peak error observed is approximately 16.595%. Conversely, when the rated primary current reaches 120%, the peak error diminishes to about 0.127%. As the rated primary current increases, there is an exponential decrease in the output error of the transformer. This phenomenon can be attributed to a gradual reduction in the ratio of noise’s peak-to-peak value relative to the measured current. Due to the independence of thermal noise from primary current, it indicates that thermal noise dominates at this time. Consequently, stronger detection currents correspond with enhanced accuracy in transformer measurements.

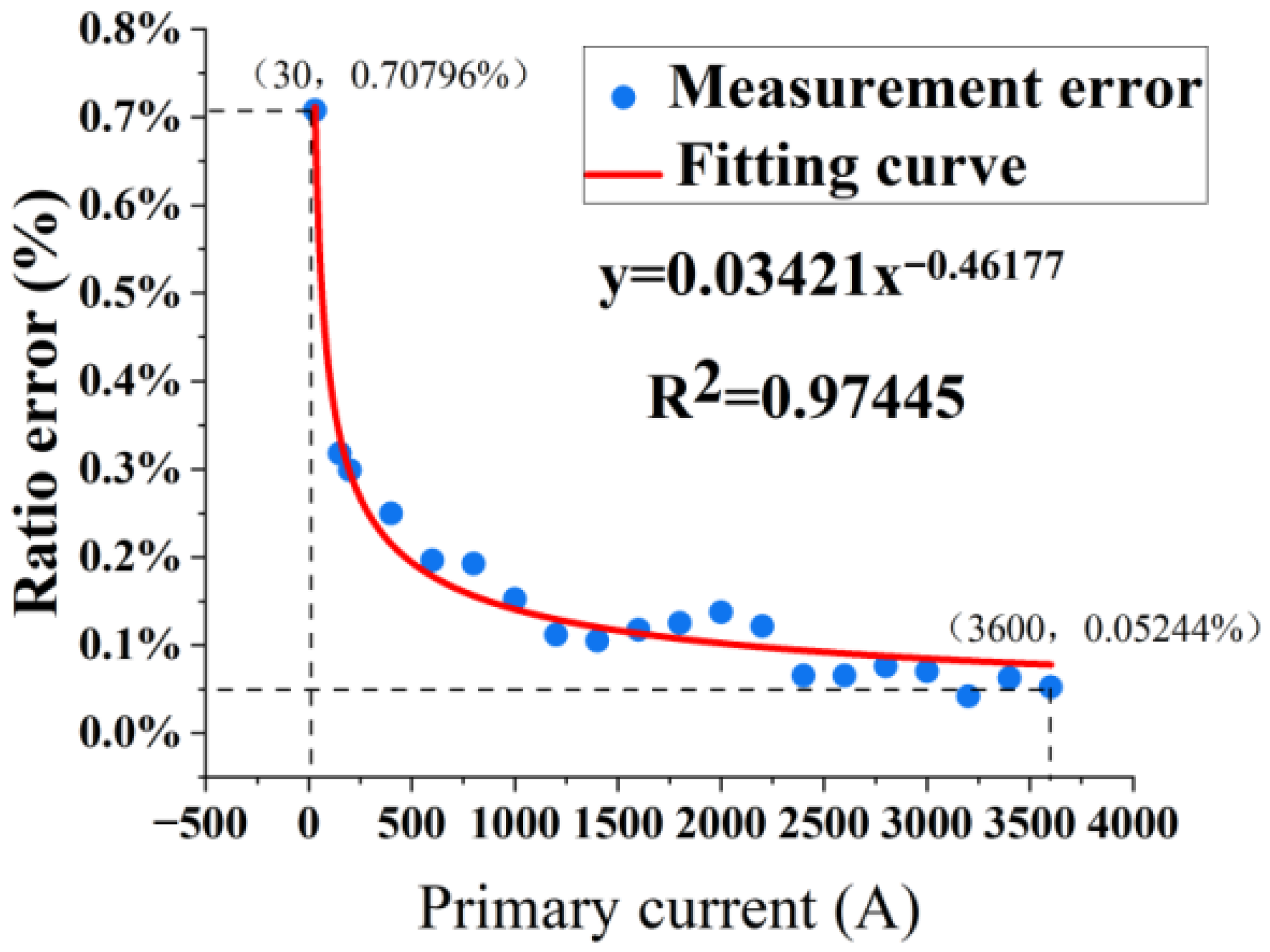

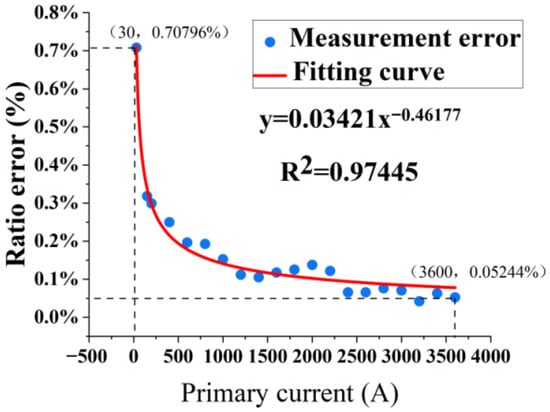

3.4. Measurement Error

Measurement error serves as a critical evaluation criterion for the performance indicators of current transformers. The permissible error limits for specialized current transformers are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Error limits for special-purpose current transformers.

For analog output, the current error can be represented as

where Kra represents the rated transformation ratio, Us represents root mean square of secondary current, and Ip represents the root mean square current value. Among them, the primary current is the output of the reference current transformer, and the secondary current is the output of AFOCT. According to this, 20 sets of data are calculated, and the maximum error value of each detection point is taken to obtain the fiber-optic current transformer ratio error diagram, as shown in Figure 11.

Figure 11.

Ratio error diagram of the AFOCT.

When the rated primary current is at 1%, 5%, 20%, 100%, and 120%, the instantaneous maximum ratio differences of the transformer are recorded as 0.708%, 0.318%, 0.197%, 0.070%, and 0.052%, respectively. When measuring low current, the measurements meet the requirements of 1% rated current, 0.75% differential and 5% rated current, and 0.35% differential current. The average measurement error of the transformer is approximately 0.106%. This value meets the requirement of less than or equal to 0.2% when the rated current is greater than or equal to 20%. Overall, fiber-optic current transformers utilizing spatial non-reciprocal phase modulation technique can satisfy the special-purpose current transformer standard at level 0.2S within the Chinese national standards across the specified range. And according to its performance parameters, it is very suitable for monitoring high current applications and plays a role in relay protection. It can maintain a certain degree of linearity even when the current is high (fault current), and it has good transient characteristics, which can quickly and accurately transmit current at the moment of fault. However, as this device remains in its prototype stage, there are numerous areas that require enhancement through ongoing testing efforts.

4. Conclusions

In summary, we have proposed an AFOCT based on a spatial non-reciprocal phase modulation technique. The approach overcomes the constraints imposed by intrinsic frequency, and the half-wave voltage of the modulator has been significantly reduced by a factor of 150. Accordingly, the scheme provides significant advantages for the optical and circuit design of current transformers. Based on this scheme, the structure of the spatial non-reciprocal phase modulator and the polarization state changes of the current transformer optical path are theoretically analyzed in detail. In addition, experimental verification was performed on the AFOCT. Its feasibility and accuracy were analyzed through a series of experiments. The experimental results of 30–3600 A (1–120%) DC current measurement show that the amplitude of noise in the waveform of transformer detection and primary current is inversely proportional. As the ratio of the peak-to-peak value of the system noise to the measured current decreases, the higher the detection accuracy can be achieved. When the rated primary current reaches 120%, the peak error is only about 0.127%. The output characteristic fitting curve has a linear regression R2 = 1, a linear slope of 0.999, and a zero-point deviation of 0.552, which has good detection consistency. In addition, within the rated measurement range, the transformer ratio deviations of 0.708%, 0.318%, 0.197%, 0.070%, and 0.052% meet the error limit of special-purpose current transformers in the Chinese national standard, and the measurement accuracy reaches 0.2 S level. In order to indicate the characteristics of different schemes more clearly, the advantages and disadvantages of current transformers are compared in Table 2, and the differences between AFOCT schemes are shown in Table 3.

Table 2.

Characteristics of current transformers with different schemes.

Table 3.

Characteristics of AFOCT based on spatial non-reciprocal phase modulation.

Author Contributions

Writing—original draft preparation, T.Z.; methodology, T.Z. and Y.Q.; investigation, T.Z.; software, T.Z. and H.Y.; data curation, T.Z.; writing—review and editing, W.F.; supervision, W.F. and Y.Q.; validation, Y.L.; resources, Y.Q.; funding acquisition, Y.Q. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (62575253).

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Shair, J.; Li, H.; Hu, J.; Xie, X. Power system stability issues, classifications and research prospects in the context of high-penetration of renewables and power electronics. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 145, 111111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saitoh, M.; Kimura, T.; Minami, Y.; Yamanaka, N.; Maruyama, S.; Nakajima, T.; Kosakada, M. Electronic instrument transformers for integrated substation systems. In Proceedings of the IEEE/PES Transmission and Distribution Conference and Exhibition, Yokohama, Japan, 6–10 October 2002; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2002; pp. 459–464. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, R.; Xu, S.; Li, W.; Wang, X. Optical fiber current sensor research: Review and outlook. Opt. Quant. Electron. 2016, 48, 442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Cui, J.; Chen, H.; Lu, H.; Zhou, F.; Rocha, P.R.F.; Yang, C. Research progress of all-fiber optic current transformers in novel power systems: A review. Microw. Opt. Technol. Lett. 2025, 67, e70061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurosawa, K. Development of fiber-optic current sensing technique and its applications in electric power systems. Photonic Sens. 2014, 4, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucuksari, S.; Karady, G.G. Experimental comparison of conventional and optical current transformers. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2010, 25, 2455–2463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, N.; Huang, Y.; Wang, S.; Wen, T.; Liu, W.; Zuo, Q.; Wang, L. Fiber optic current sensor based on special spun highly birefringent fiber. IEEE Photon. Technol. Lett. 2013, 25, 1668–1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.-H.; Kang, J.U. Sagnac loop interferometer based on polarization maintaining photonic crystal fiber with reduced temperature sensitivity. Opt. Express 2004, 12, 4490–4495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Huang, Y.; Deng, C.; Hu, C.; Huang, C.; Dong, Y.; Shang, Y.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, X.; Wang, T. Magneto-refractive properties and measurement of an erbium-doped fiber. Opt. Express 2021, 29, 34577–34589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, W.; Xing, J.; Yang, Z.; Yao, R. Mechanism analysis of faraday effect based on magneto-optic coupling. Laser Optoelectron. Prog. 2017, 54, 062601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, G.M.; Gu, X.; Yang, L.; Frank, A.; Bohnert, K. Inherent temperature compensation of fiber-optic current sensors employing spun highly birefringent Fiber. Opt. Express 2016, 24, 11164–11173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, P.; Yao, X.S.; Chen, X.; Xiao, H.; Li, J. Relative error’s quadratic dependence on the electric current and the techniques for its compensation in fiber optic current sensor systems. Opt. Express 2022, 30, 471–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenner, M.; Frank, A.; Yang, L.; Roininen, T.M.; Bohnert, K. Long-term reliability of fiber-optic current sensors. IEEE Sens. J. 2020, 20, 823–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Zhang, X.; Chen, L.; Wu, B.; Peng, C. Research on all-fiber dual-modulation optic current sensor based on real-time temperature compensation. IEEE Photonics J. 2022, 14, 6822609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sima, W.; Zeng, L.; Yang, M.; Yuan, T.; Sun, P. Improving the temperature and vibration robustness of fiber optic current transformer using fiber polarization rotator. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2022, 71, 9000612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Shi, L.; Sun, X. Design and performance study of a temperature compensated ±1100-kV UHVdc all fiber current transformer. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2021, 70, 7001206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Xia, L.; Pang, F.; Yuan, Y.; Ji, J. Self-compensative fiber optic current sensor. J. Light. Technol. 2021, 39, 2187–2193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muller, G.M.; Frank, A.; Yang, L.; Gu, X.; Bohnert, K. Temperature compensation of interferometric and polarimetric fiber-optic current sensors with spun highly birefringent fiber. J. Light. Technol. 2019, 37, 4507–4513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenner, M.; Hsu, C.-P.; Yang, L.; Frank, A.; Bohnert, K. Performance and long-term reliability of polarization-maintaining fiber connectors for fiber-optic current sensors. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE SENSORS, New Delhi, India, 28–31 October 2018; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, A.; Pang, F.; Yuan, Y.; Huang, Y.; Li, S.; Yu, S.; Zhou, M.; Xia, L. Simultaneous current and vibration measurement based on interferometric fiber optic sensor. Opt. Laser Technol. 2023, 161, 109223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, S.; Wan, L.; Zhou, Y.; Sun, J.; Liu, L. Transversal electro-optic effect of light propagating in arbitrary direction in LiNbO3. Acta Opt. Sin. 2010, 30, 2972–2977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tudi, A.; Han, S.; Yang, Z.; Pan, S. Potential optical functional crystals with large birefringence: Recent advances and future prospects. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2022, 459, 214380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wooten, E.L.; Kissa, K.M.; Yi-Yan, A.; Murphy, E.J.; Lafaw, D.A.; Hallemeier, P.F.; Maack, D.; Attanasio, D.V.; Fritz, D.J.; McBrien, G.J.; et al. A review of lithium niobate modulators for fiber-optic communications systems. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Quant. Electron. 2000, 6, 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.; Zhang, S.; Tian, Z. Refractive indices of biaxial crystals evaluated from the refractive indices ellipsoid equation. Opt. Laser Technol. 2007, 39, 510–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Y.; Wang, M.; Jiang, F.; Zhang, X.; Cong, B.; Liu, Y. Novel fiber optic current transformer with new phase modulation technique. Photonic Sens. 2020, 10, 275–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, A.; Gupta, P.B.D.; Mandal, A.K. Development of a fiber-optic current sensor with range-changing facility using shunt configuration. IEEE Sens. J. 2013, 13, 1347–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Song, H. Theoretical analysis on polarization characteristics of spun birefringent optical fiber based on an analytical Jones matrix model. Optik 2021, 228, 166179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, H.; Jin, S.; An, Y.; Zeng, Z.; Qu, Z. Phase distortion analysis and passive demodulation for pipeline safety system based on Jones matrix modeling. Measurement 2011, 44, 1531–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Chen, M.; Chen, H.; Lu, Y.; Wang, J. Online measurement of birefringence of sensing fibers in the AFOCT system. Microw. Opt. Technol. Lett. 2024, 66, e34029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.