Abstract

This study reviews advanced extreme value theory techniques and applies them to extreme rainfall events recorded at two meteorological stations, Port Edward and Virginia, in the KwaZulu-Natal province of South Africa. The study aims to provide a comparative analysis of the performance of three extreme value theory models—the generalised extreme value distribution (GEVD), the generalised extreme value distribution for r-largest order statistics (GEVDr), and the blended generalised extreme value distribution (bGEVD)—in modelling extreme rainfall events. The monthly maximum rainfall data used in the study was obtained from the South African Weather Service. The Shapiro–Wilk test demonstrated the non-normality of the rainfall datasets. Parameter estimation was performed using maximum likelihood estimation and Bayesian estimation methods, both yielding positive shape parameters consistent with the Fréchet class of distributions. The goodness-of-fit tests confirmed the suitability of the GEVD model for the data. The results of both the standard GEVD and GEVDr models provided consistent return level estimates, suggesting strong model performance. The bGEVD model produced lower return level estimates compared to the GEVD and GEVDr models. Overall, the findings of the study offer valuable insights into the behaviour of extreme rainfall in KwaZulu-Natal province, with significant implications for risk management, infrastructure planning, and disaster preparedness. This study will add value to the literature and knowledge of statistics.

1. Introduction

Natural disasters are well-established in the literature as important contributors to disastrous events all over the world [1]. Flooding is one of the natural disasters that poses damage to property, infrastructure, and human lives [2,3]. Homes, businesses, and infrastructure, such as power lines, bridges, and highways, can all be destroyed by floods [2,4,5]. This might cause major financial losses and interfere with daily lives in the affected communities [1,6,7]. Floods can cause loss of life, particularly in areas with poor infrastructure, lack of proper drainage systems, and low-lying regions [6]. If people are caught off guard, it can be difficult for them to flee from strong currents and deep waters. Flooding has the potential to pose a threat to food security since it may result in the loss of livestock and top fertile soil due to washing away [8,9]. Flooding has become a prevailing natural disaster in the region of Southern Africa. According to Boudrissa et al. [10], a fundamental difficulty in climatology is determining the possible threats posed by severe rainfall in order to protect people and property.

This entails determining the frequency and severity of disasters and unforeseen events, such as floods. The goal now is to anticipate and minimise the consequences of these events to the greatest extent possible. Southern Africa experiences frequent occurrences of floods, which have become a prevalent form of natural calamity. As a result of its geographic location, South Africa is among nations that have encountered difficulties associated with flooding [11]. The focus of this study is specifically directed towards the KwaZulu-Natal province in South Africa, where a significant event of severe flooding occurred on 11 April 2022. According to Naidoo et al. [12], during this specific period, the floods caused extensive destruction to infrastructure and property, tragically resulting in the loss of human lives as well as livestock. This province is vulnerable to flooding because it is located along the Indian Ocean on the east coast of South Africa, which receives high rainfall, especially in summer, due to warm ocean currents and tropical air masses [2].

This eastern coast is known for extreme flooding due to its landscape and geographical position. According to Du Plessis and Burger [13], as the global climate continues to change, the frequency and intensity of extreme weather phenomena like heavy rainfall and flooding is anticipated to increase. Concerns about rising greenhouse gas emissions from industrialised nations, which raise global temperatures and alter other climate factors like precipitation and evaporation, are spreading across the globe [14,15]. This could make floods in KwaZulu-Natal province and other regions more frequent and severe in the future. Coles [16] defines extreme value theory (EVT) as the study of very rare events.

The current study employs modern techniques of EVT to model the floods in KwaZulu-Natal province. These models include the blended generalised extreme value distribution (bGEVD) and the generalised extreme value distribution for the r-largest order statistics (GEVDr). These models are extensions of the generalised extreme value distribution (GEVD) [17,18]. The statistical approach known as EVT is frequently used to analyse extreme events such as floods [16]. The literature is scarce on the use of new advanced EVT techniques such as the bGEVD in analysing flood events [17,18]. This study explores the use of this advanced EVT method in analysing extreme flood events in selected stations of the KwaZulu-Natal province.

The rest of the paper is structured as follows: Section 2 presents a review of the relevant and related literature, while Section 3 summarises the key findings of this study. Section 4 outlines the methods and techniques employed in this study. Section 5 discusses the results and findings corresponding to each method used. Finally, Section 6 provides the conclusions, recommendations, and directions for future research.

2. Related Literature Review

Finance, insurance, engineering, hydrology, and climatology are just a few of the many fields where EVT is frequently used to analyse extremes and associated return levels [14]. The literature reveals that EVT has been a fundamental statistical approach in applied sciences for over five decades [16,17,19]. According to Maposa et al. [19], many statistical applications frequently ignore extreme values as outliers in favour of the mean and other measures of central tendency. Nonetheless, the focus in rare or extreme events is on the tails of the underlying data distribution. These rare or extreme events, which are often referred to as outliers, are uncommon and severe events that are usually dropped during data cleaning and analysis [19]. According to Ferreira and De Haan [16,20], the distribution of maxima over blocks is usually approximated using the GEVD. However, Castro-Camilo et al. [17] noted that its features might not always be applicable to some given data. These authors used the bGEVD, which combines the right tail of an unbounded-support Fréchet distribution with the left tail of a Gumbel distribution. They also employed a method known as property-preserving penalised complexity priors to establish the first and second moments of the GEVD beforehand.

Castro-Camilo et al. [17] provided a new parameterisation of the GEVD that offers a more realistic interpretation of the characteristics of the model that provides useful priors. They demonstrated the effectiveness of their strategy using simulations and applying it to nitrogen dioxide pollution levels in California. Overall, their new approaches provided improvements over the traditional GEVD models in several instances. A brand-new technique for creating geographic maps of return level estimates for the annual maxima of sub-daily precipitation was put forth by [18]. In order to simulate annual precipitation maxima, the study employed a Bayesian hierarchical model with a latent Gaussian field and the bGEVD. To improve the efficacy of inference, the authors utilised a unique two-step approach to model the scale parameter of the bGEVD by analysing peaks-over-threshold (POT) data.

The stochastic partial differential equation technique and integrated nested Laplace approximations (INLA), both employed in R-INLA, were used in inference in [18]. By utilising numerical approximations instead of sampling-based inference methods such as Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC), the INLA framework offers a substantial acceleration in computation speed. Additionally, heuristics for enhancing numerical stability with the GEVD and bGEVD were provided in a study by [18]. In their study, the model more rapidly produced high-resolution return level maps with uncertainty by being fitted to the yearly maxima of sub-daily precipitation from the South of Norway. Modelling the yearly maxima of sub-daily precipitation with the bGEVD resulted in a better model fit overall than with the usual inference techniques.

Tibari [21] concentrated on the assessment of hydrological extremes, which have substantial socio-economic implications and are essential for the planning and design of hydraulic structures. The researcher conducted a comparison between two statistical modelling approaches for extreme hydrological events: block maxima (BM) and peak-over-threshold (POT). Tibari [21] investigated how future projected changes in extreme hydrological events are impacted by the chosen method, particularly when simplifications are applied for large-scale studies. The outcomes suggest that both the BM and POT methods align in indicating the direction of changes in flood and extreme precipitation intensities, but they diverge in terms of magnitude. The disparity between the two methods becomes more pronounced for more extreme events. Additionally, the variation in results is dependent on the season.

Miniussi et al. [22] used the daily mean streamflow records from 5311 stream gauges in the continental United States, obtained from the U.S. Geological Survey, to analyse and develop a tailored Metastatistical Extreme Value Distribution (MEVD) for flood frequency analysis. The performance of the MEVD was compared with two commonly used distributions, namely the GEVD and Log-Pearson Type III (LP3), and the role of the El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO) in flood generation was investigated. The study found that the MEVD outperforms the GEVD and LP3 distributions in approximately 76 and 86 percent of the stations, respectively. The MEVD showed a significant improvement in the accuracy of quantiles corresponding to return periods that are much larger than the standard sample size.

Vasiliades et al. [23] employed the GEVD to analyse nonstationarity in the annual maximum daily rainfall time series in Greece and Cyprus. The parameters of the GEVD were modelled as functions of time-varying covariates, and the conditional density network (CDN), which is an extension of the multilayer perceptron neural network, was employed to estimate these parameters. The model parameters were estimated using the generalised maximum likelihood (GML) approach with the quasi-Newton BFGS optimisation algorithm. The appropriate GEV-CDN model architecture for each meteorological station was selected based on the Akaike information criterion or the Bayesian information criterion. The findings of the study demonstrated the application of the GEV-CDN model for assessing nonstationarity in extreme rainfall events. The results highlighted the importance of considering temporal variability in hydrometeorological processes when conducting extreme value analyses. Maposa et al. [24] employed the GEVD to model annual flood heights in the lower Limpopo River basin of Mozambique. The study focused on four different time series models: annual daily maxima (AM1), annual maxima 2 days (AM2), annual maxima 5 days (AM5), and annual maxima 10 days (AM10). The results indicated that the AM5 model was suitable for analysing flood heights at the Chokwe station, while the AM10 model was appropriate for the Sicacate station. In another study by [25], a comparative analysis of parameter estimation methods for the GEVD was conducted in the lower Limpopo River basin of Mozambique. The MLE and Bayesian estimation methods were compared. The authors used MCMC Bayesian method to estimate the parameters of the GEVD, aiming to predict extreme flood heights and their return periods. The findings suggested that the Bayesian approach outperformed the MLE approach in terms of parameter estimation.

The analysis of rainfall extremes in East Africa in the context of climate change was conducted by [26]. The research examined the impact of convection-permitting climate models compared to parameterised convection models in representing rare rainfall extremes. EVT and regional frequency analysis were employed to quantify these rare rainfall events using the CP4A convection-permitting model and its parameterised counterpart (P25), as well as the CORDEX-Africa ensemble and observational data for comparison. The findings revealed that the convection-permitting model (CP4A) aligns better with observations compared to the parameterised models. It was observed that the parameterised convection models exhibit unrealistic changes in the shape parameter of the extreme value distribution, resulting in significant increases in return levels for events with longer return periods (greater than 20 years). The findings suggest that parameterised convection models may not be suitable for analysing relative changes in rare rainfall events under climate change.

Chikobvu and Chifurira [27] utilised GEVD to model the extreme minimum annual rainfall in Zimbabwe. They applied the GEVD to annual rainfall data spanning from 1901 to 2009. The results obtained from model diagnostics revealed that the minimum annual rainfall in Zimbabwe follows a distribution from the Weibull class. On the other hand, Boudrissa et al. [10] conducted an analysis using GEVD to examine the annual maximum daily rainfall at selected stations in the northern region of Algeria. The empirical findings demonstrated that the Gumbel distribution provided a good fit for the Algiers and Miliana stations, while the Fréchet distribution was found to be more suitable for the Oran station. A study conducted by [28] focuses on the modelling of monthly extreme rainfall in Somalia over a 116-year period using various statistical distributions. The models employed in the study include the GEVD, GPD, r largest order statistics, and point process (PP) characterisation. The optimal model was determined based on criteria such as negative log-likelihood, Akaike information criteria (AIC), and Bayesian information criteria (BIC). The findings of the study reveal that the GEVD, with specific parameter values, provides the best fit for modelling extreme rainfall in Somalia.

Sikhwari et al. [29] utilised EVT to model maximum rainfall data in Limpopo Province, South Africa, covering the period from 1960 to 2020. The study employed the r-largest order statistics modelling approach and analysed yearly blocks of data spanning 61 years. The parameters of the selected model, namely the GEVD with r = 8, were estimated using the maximum likelihood method. The findings reveal that the estimated 50-year return level in the Thabazimbi area is 368 mm, indicating a 0.02 probability of rainfall exceeding this threshold within a fifty-year time frame. Another study conducted by [30] employed spatial and spatio-temporal dependence modelling techniques to analyse extreme daily maximum rainfall data from selected weather stations in South Africa. The study utilised a combination of the GPD and the flexible Bayesian Latent Gaussian Model (LGM). The results highlighted the effectiveness of the spatio temporal GPD model in capturing systematic variation within a spatial and spatio-temporal modelling framework. The temporal component was modelled separately for weeks and months. To estimate the marginal posterior means of the parameters and hyperparameters for the Bayesian spatio-temporal models, the study utilised the INLA algorithm. The INLA technique facilitated Bayesian inferences and allowed for the prediction of return levels at each station, incorporating uncertainty arising from model estimation and the inherent randomness of the processes.

In their research, Singo et al. [31] conducted a study in the Luvuvhu River Catchment in Limpopo Province, South Africa, focusing on the evaluation of flood risks using flood frequency models. The main objective of the study was to estimate flood risks by analysing the distribution of rainfall. For the flood frequency analysis, the researchers selected the Gumbel and LP3 distributions. The findings of the study indicated a notable rise in the occurrence of extreme events, leading to floods of greater magnitude. The study conducted by [32] focused on a regional frequency analysis of the annual maximum series (AMS) of flood flows in the KwaZulu-Natal province of South Africa. The objective was to identify homogeneous regions and determine suitable regional frequency distributions for these regions. The study divided the area into two regions based on monthly rainfall concentrations. Region 1 encompassed the coastal and midlands area, while Region 2 covered the west north-western parts of the study area. The researchers found that the General Normal, Pearson Type 3, and General Pareto distributions were suitable for modelling the AMS of flood flows in Region 2. However, in Region 1, due to the occurrence of only a few flood events of extreme magnitude, no suitable regional frequency distribution could be identified.

Researchers have explored the application of EVT to predict extreme weather events in the field of climatology, specifically related to extreme occurrences. Their focus was mainly on the generalised Pareto distribution (GPD) and GEVD and less on modern techniques. The insufficient application of modern techniques highlights a methodological and literature gap that this study seeks to address. To enhance the applicability, dependability, and precision of EVT in modelling rainfall in KwaZulu-Natal province, this study will employ modern and advanced EVT models like bGEVD and GEVDr using Bayesian MCMC parameter estimation approach.

3. Research Highlights

This section presents the key research highlights derived from the empirical findings discussed in Section 5. The study provides the following insights aimed at enhancing rainfall modelling in the KwaZulu-Natal province and contributing to the body of knowledge on EVT modelling techniques.

- (a)

- The MLE and Bayesian methods were used to estimate the three parameters of the GEVD; the estimated parameters obtained from both methods were found to be relatively similar.

- (b)

- Both the MLE and Bayesian approaches yielded positive values for the shape parameter, indicating that the Fréchet distribution is the most appropriate among the three GEVD classes.

- (c)

- The was fitted to the five largest blocks of maxima, and the optimal block sizes were determined to be and for the Port Edward and Virginia stations, respectively.

- (d)

- The return levels obtained from the standard GEVD model and the models were found to be closely comparable and relatively consistent.

- (e)

- The results from the bGEVD model suggested a negative time trend in the explanatory variables, indicating a decline in rainfall maxima over time.

- (f)

- The bGEVD model produced lower return levels and its results are inconsistent with those obtained from the standard GEVD and GEVD for r-largest order statistics.

- (g)

- The GEVD and proved to be the suitable distributions for fitting the data and estimating return levels over the bGEVD model.

- (h)

- This study acknowledges the limited literature on the newly introduced bGEVD model and seeks to address this research gap by contributing to the existing body of knowledge.

- (i)

- The study acknowledges the limitations that data incompleteness and missing values may impose on the reliability of the estimates. However, missing observations were addressed by applying rolling annual averages to replace the missing values.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Data Source and Study Area

The monthly rainfall data for the KwaZulu-Natal province was obtained from the South African Weather Service (SAWS). This valuable rainfall dataset comprises time series data measured in millimetres (mm). The data is meticulously categorised into various stations located within the province, ensuring a comprehensive representation of the region. Figure 1 presents the map of South Africa, with the highlighted portion indicating the geographical location of KwaZulu-Natal province within the country’s borders.

Figure 1.

Geographical location of KwaZulu-Natal province in South African [Source: https://w.wiki/B2us, accessed on 30 July 2025].

4.2. Extreme Value Analytical Techniques

The following section presents the extreme value distributions employed in this study. There are two fundamental approaches to extreme value theory (EVT): the block maxima and the peaks-over threshold methods [11,20,33]. In this study, the block maxima approach and its extensions are used to model monthly rainfall data from meteorological stations in KwaZulu-Natal Province. The model, which represent the cornerstone of extreme value theory, is now demonstrated. The model focuses on the statistical behaviour of

where is a sequence of independent random variable having a common distribution function F [16]. In this application, represents the monthly rainfall recorded in the KwaZulu-Natal province, such that represents the maximum of the process over n time units of observations. If n is the number of observations in a year, then corresponds to the annual maximum. Then, the distribution of can be derived as

if there exists a sequence of constants and such that

where G is a non-degenerate distribution function, then G belongs to one of the following families:

for parameters , b, and, in the case of families and , [16,33,34].

4.2.1. Modelling Generalised Extreme Value Distribution (GEVD)

According to Coles [16], the rescaled sample maxima converges in distribution to a variable having a distribution within one of the families labelled I, II, and III above. Collectively, these three classes of distributions are termed the extreme value distributions, with types I, II, and III widely known as the Gumbel, Fréchet, and Weibull families, respectively [16,35,36]. Each of these families has a location and a scale parameter, b and a, respectively; additionally, the Fréchet and Weibull families have a shape parameter . According to Coles [16], these three families of distributions (Gumbel, Fréchet, and Weibull) can be combined into a single family of models having a distribution function of the form

where the parameters satisfy , , and . This is the generalised extreme value (GEVD) family of distributions. This model has three parameters: a location parameter, ; a scale parameter, ; and a shape parameter, [16,35].

GEVD converges to one of the three families of extreme value distributions, depending on the rate of decay of the tail indexed by the shape parameter [36]. When , G(z) reduces to type I or a short-tailed unbounded Gumbel family of distributions [35,36]. When , G(z) is thin-tailed and we get a type II family that is the Weibull class of distributions with an upper bound given by [35,36]. If , then G(z) belongs to a type III family that is a heavy-tailed Fréchet class of distributions that is bounded below by [35,36].

4.2.2. GEVD for the r Largest Order Statistics (GEVDr)

Employing r largest order statistics serves as an alternative approach for modelling data, distinct from the utilisation of block maxima. Criticism is sometimes directed at the application of the GEVD derived from the block maxima approach, as it is argued to potentially waste data when additional data on extremes is available [36,37,38]. The GEVD for r largest order statistics was developed to overcome this problem [37].

Consider , a sequence of independent and identically distributed random variables. Define

If there exists sequences of constraints and such that

4.2.3. Blended GEVD

The bGEVD combines the left tail of a Gumbel distribution (GEV with 0) with the right tail of a Fréchet distribution (GEV with 0), resulting in a heavy-tailed distribution with a parameter-free support [17]. Therefore, bGEVD was employed in this study to fit the monthly rainfall data in the KwaZulu-Natal province of South Africa. The bGEVD is given by

where F is a GEVD with and G is a Gumbel distribution [17,18]. The weight function is equal to

where is the distribution function of a beta distribution with parameters , which amounts to a symmetric and computationally efficient weight function. The weight is zero for and equals one for , meaning that the left tail of the bGEVD equals the left tail in G, whereas the right tail equals the right tail in F [18,39]. The parameters and are injective functions of , such that the bGEVD function is continuous and for [18]. According to Metwane and Maposa [39] and Castro-Camilo et al. [17], H is fully defined by the parameters and the hyperparameters .

4.2.4. bGEVD Models

Let denote the maximum precipitation at location during month , where S is the study area and T is the time period in focus. According to Vandeskog et al. [18], the bGEVD for the monthly precipitation maxima can be assumed by

where all observations are assumed to be conditionally independent given the parameters , and . The two competing models, namely the joint model and the two-step model, will be fitted to describe the structures of and under the INLA framework [18,39].

4.2.5. The Integrated Nested Laplace Approximation (INLA)

The performance of the bGEVD is tested and modelled using a package called R-INLA version 24.05.10 for R 4.4 Vandeskog et al. [18] stated that R-INLA is a new addition to the extreme value framework that enables INLA inference using latent Gaussian models, and both the joint and two-step models fall into the class of latent Gaussian models. This is an advantage as R-INLA allows for their inference.

4.3. Parameter Estimation Methods

The statistical literature provides various techniques for estimating the parameters of a probability distribution. Therefore, this study employs the maximum likelihood estimator (MLE) and the Bayesian parameter estimation methods.

4.3.1. Maximum Likelihood Estimation for GEVD

The adaptability of the MLE to changes in model structure, compared to other parameter estimation techniques, makes it a profitable approach [16]. Consider a series of observed sample block maxima that are assumed to be independent and identically distributed (iid) random variables each having a GEVD with the probability density function [11,16]; the likelihood function is given by

and the log likelihood function given by

The MLEs , and are the parameter values that will maximise the log likelihood function [11]. Therefore, the log function for the GEV parameters when is given by [11,14,16,40]

provided that , for . The MLEs , and are determined by maximising Equation (15) with respect to the parameter vector [14]. However, there is no existing analytical solution to Equation (15) [11,14,16]. Therefore, to obtain the MLEs we use numerical optimisation algorithms such as Newton–Raphson or Quasi-Newton [11,14,16].

4.3.2. Bayesian Estimation

Let the prior distribution be denoted by where [11]. Let , then the prior distribution on is defined as [41]

where is the mean vector and is the covariance matrix [41]. The likelihood function is [42]

The joint posterior density is given as

which reduces to

4.4. Inference for Return Levels

In extreme value analysis, it is often more suitable to present the return level on an annual scale. The p-year return level represents the level expected to be exceeded once every p-years with a probability of [14,43].

Estimates of extreme quantiles are obtained by [14,16]

where . is the return level associated with the return period , since to a reasonable degree of accuracy the level is expected to be exceeded on average once every years [16].

By substituting the MLEs of the GEVD parameters into Equation (20), the MLEs of for , the return level is obtained as [16,34]

4.5. Deviance Statistics

Maximum likelihood estimation for nested models provides a straightforward procedure for testing one model against another [34]. Considering models , where and m represents the number of models, the deviance statistic is defined as follows [44]:

where and denote the log-likelihood of the respective models [11]. Large values of D indicate that the model accounts for significantly more variation in the data compared to . Conversely, small values of D imply that increasing the complexity of the model does not result in meaningful improvements in its ability to explain the data [34]. The model is rejected at the level of significance if , where represents the critical value corresponding to . The distribution of D follows a chi-square distribution () with k degrees of freedom, where k is the difference in dimesionality between and [16].

4.6. Goodness-of-Fit

In this study, we utilise probability plots, quantile plots, return level plots, and density plots for model checking. Graphical diagnostic techniques are subjective in nature and should, therefore, be used in conjunction with more effective statistical tests for support [14]. A statistical model’s goodness-of-fit (GoF) indicates how well it fits a given set of data. A measure of the model’s GoF usually provides an overview of the differences between the observed and expected values. Two GoF tests, Anderson–Darling (A-D) and Kolomogorov–Smirnov (K-S), were employed and tested at a 5% level of significance. Let be a sample of n monthly maximum floods heights observed and suppose the cumulative distribution function (CDF) of the random variable X is , then the K-S and A-D tests are as presented in the next subsections.

4.6.1. Anderson–Darling Test

The A-D test was developed as an alternative for other statistical tests to identify variations from normality in sample distributions [45]. Comparing the fit of an observed CDF to a theoretical (anticipated) CDF serves as the foundation for this test [45,46]. The test statistic is one-directional, denoted , and defined by

where the data x is the ordered (from smallest to largest) sample of size n, and is the underlying theoretical CDF to which the sample is compared. is the empirical CDF.

The hypotheses to be tested for GoF under A-D test are

H0.

The data follows a specified distribution.

H1.

The data does not follow the specified distribution.

The mathematical formulation of the hypothesis is given as follows:

The null hypothesis () for this A-D test is rejected at the 5% significance level if is different from the hypothesised distribution , that is if the calculated is greater than the tabulated or critical value [45]. This test gives more weight to the tail of the distribution than the K-S test [46].

4.6.2. Kolomogorov–Smirnov Test

This K-S test is based on a comparison between the largest vertical distance, , between the observed CDF, , and the theoretical CDF, [33,45]. The test statistic is given by

The hypotheses for the GoF under the K-S test is given by

The for this test is rejected at the 5% level of significance if the calculated is greater than the tabulated value [14,46]. The main advantage of the K-S test is its sensitivity to the shape of a distribution, because it can detect differences everywhere along the scale [45]. Also, it is more sensitivity to the centre of the distribution than the A-D test [33].

4.7. Normality Test

According to de Souza et al. [47], an often-made error that can lead to inconsistent analysis of variance data is ignoring the violation of the error normality assumption. When this normality assumption is violated, interpretations and inferences may not be reliable or valid [48]. To avoid this error, normality tests such as the Shapiro–Wilk test can be used to verify whether this assumption is met or violated [47]. The Shapiro–Wilk test can be used in support of other common procedures to assess whether a sample of independent observations (of size n) comes from a population with a normal distribution. Such procedures include graphical methods (box plots, Q-Q plots, histogram, stem-and-leaf plot), descriptive statistics (skewness and kurtosis), and other formal normality tests [47].

Shapiro–Wilk Test

Shapiro-Wilk test is able to detect departures from normality due to either skewness, kurtosis, or both [47]. The test statistic is of the form

where is the order statistics, is the sample mean, and the constants are given by

where are the expected values of the order statistics of independent and identically distributed random variables sampled from the standard normal distribution and V is the covariance matrix of those order statistics [47,49].

The Shapiro–Wilk test is estimated under the following hypotheses:

H0.

The monthly rainfall data is normally distributed.

H1.

The monthly rainfall data is not normally distributed.

5. Results and Analysis

Table 1 presents the summary statistics for the two selected meteorological stations in the KwaZulu-Natal province. The table provides important insights into the variability of the data and helps in understanding its distribution. It includes key statistical measures such as the minimum, maximum, median, mean, standard deviation, skewness, and kurtosis. Notably, the Port Edward station recorded a minimum daily rainfall of 0.2 mm and a maximum of 549.20 mm over a 29-year period (1993–2022), while the Virginia station recorded a minimum daily rainfall of 0.2 mm and a maximum of 334.60 mm over a 28-year period (1994–2022).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of the rainfall data (in mm) from the two stations in the KwaZulu-Natal province.

In both stations, the mean is noted to be greater than the median, indicating that the rainfall data is positively skewed (right-skewed). This is evidenced by the positive skewness values in Table 1. The positive skewness means that a few higher values are pulling the mean to the right of the median, due to some exceptionally high values that increase the mean. Both the stations exceed the kurtosis threshold of three, indicating more values in the distribution tails and a sharply peaked distribution with heavy tails. EVT is a statistical approach that focuses on distributions with heavy tails.

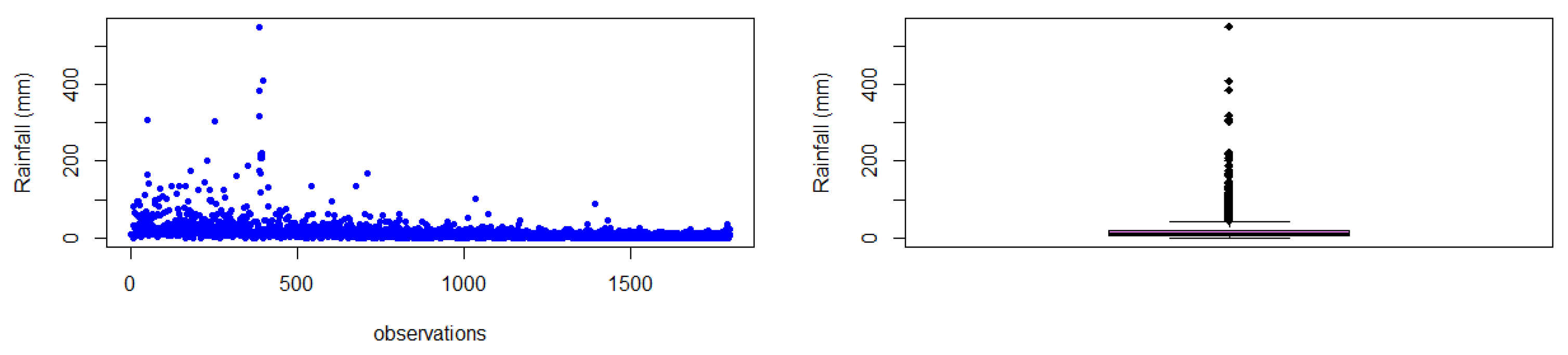

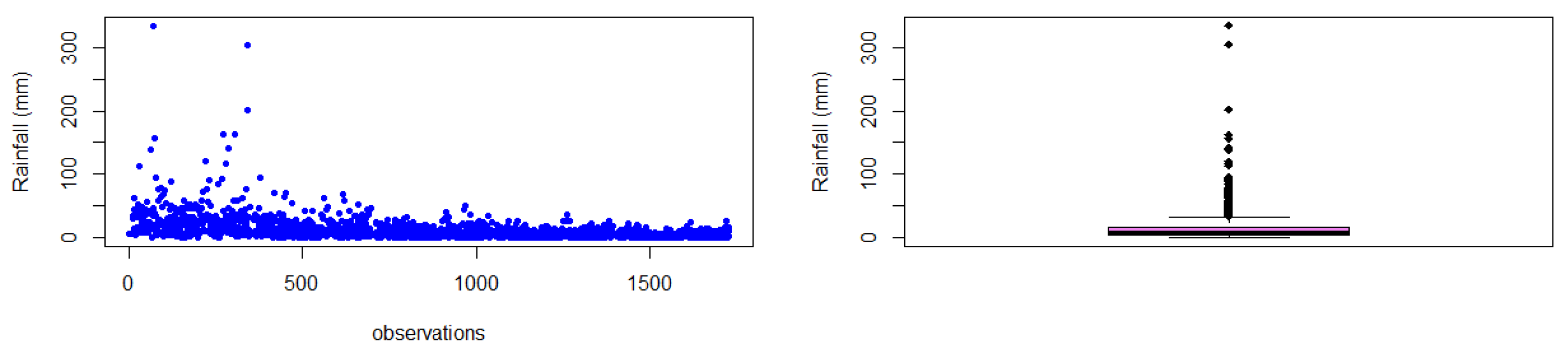

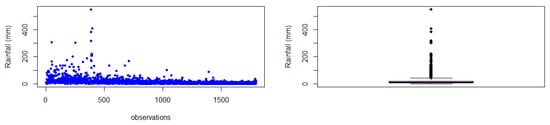

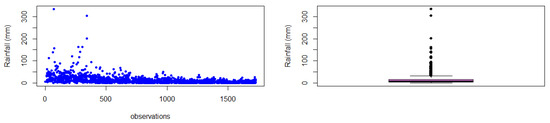

5.1. Scatter Plots and Box Plots

Figure 2 and Figure 3 present the scatter plots and box plots for the two selected stations in the KwaZulu-Natal province. The plots illustrate the data distribution and highlight the presence of extreme values within the datasets. The two figure plots clearly indicate the existence of outliers, with the box plots specifically showing data points that lie outside the tails of the distribution. Most of these outliers are located above the upper limit of the datasets, suggesting the occurrence of extreme rainfall values during the respective time frames.

Figure 2.

Scatter and box plots for Port Edward station depicting data distribution.

Figure 3.

Scatter and box plots for Virginia station depicting data distribution.

5.2. Test for Stationarity

Table 2 presents the stationarity results of the rainfall data from three tests (ADF, PP, and KPSS) conducted at the two selected stations in the KwaZulu-Natal province.

Table 2.

Results for stationarity tests (ADF, PP, and KPSS).

At a 5% level of significance , the ADF and PP tests suggest that the data for the two stations in Table 2 are stationary, as the p-values are less than . The null hypothesis of non-stationarity is therefore rejected. On the other hand, the KPSS test suggests that the data for the two stations are non-stationary, as the p-values are less than . It should be noted that the hypotheses of the KPSS test are the opposite of those of the ADF and PP tests. Since both the ADF and PP tests suggest that the data is stationary, there is significant evidence to conclude that the data is stationary in the two selected stations. As discussed earlier, these tests have weaknesses and strengths in different cases. Two of the three tests are significant to conclude in favour of stationarity.

5.3. GEVD Modelling

The MLE and Bayesian methods were used to estimate the three parameters (location (), scale (), and shape ()) of the GEVD. From Table 3, it is noted that the estimated parameters from the two methods are relatively close to each other. Both MLE and Bayesian estimation have produced similar estimates, and it is worth noting that the shape () parameter is positive for both stations. Positive estimates of the shape parameter () suggest that the Fréchet class of distribution is the most appropriate among the three classes of the GEVD, and the confidence interval confirms this conclusion. Therefore, the results in Table 3 suggest that both stations follow the Fréchet class of distribution for the fitted data. However, this still needs further investigation for model validation by employing goodness-of-fit tests and diagnostic plots.

Table 3.

Parameter estimates using MLE and Bayesian estimation, along with standard errors obtained by MLE (in parentheses), for the GEVD at the two stations.

5.3.1. Assessment of Goodness-of-Fit

This section presents the assessment of goodness-of-fit. The assessment is conducted using goodness-of-fit tests and diagnostic plots. The goodness-of-fit results are obtained based on parameters estimated through MLE and Bayesian methods. This critical analysis is performed at each selected station. The Anderson–Darling (A-D) and Kolmogorov–Smirnov (K-S) tests are employed to evaluate whether the monthly maximum rainfall data follows the GEVD model.

The A-D and K-S test results in Table 4 pertain to the maximum monthly rainfall data from the Port Edward and Virginia stations. The table provides clear evidence, as the p-values exceed the significance level (), indicating that the data do not provide significant results to reject the null hypothesis that the series follows the GEVD model.

Table 4.

Results of the goodness-of-fit tests for the data from Port Edward and Virginia stations to the GEVD model, using parameters estimated by both MLE and Bayesian estimation.

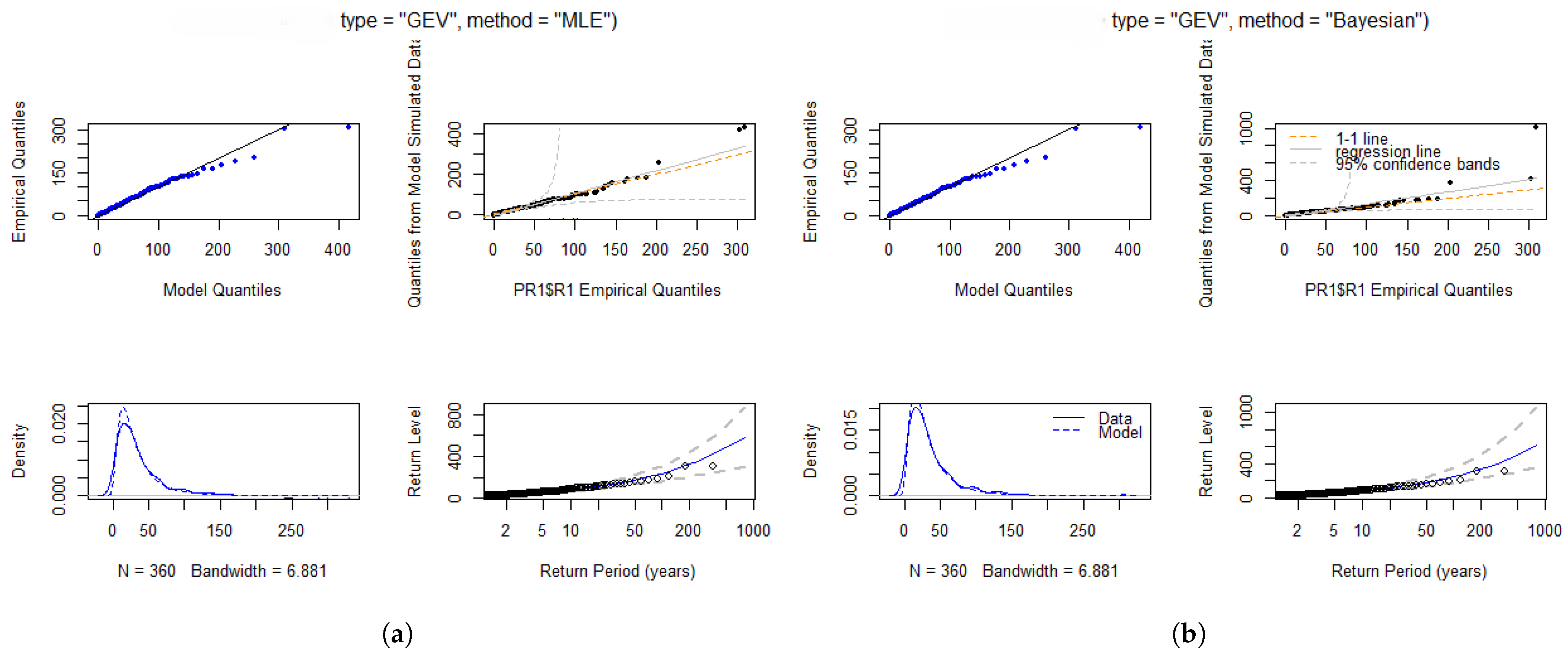

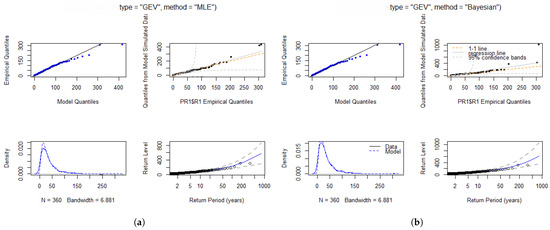

5.3.2. GEVD Diagnostic Plots for Port Edward Station

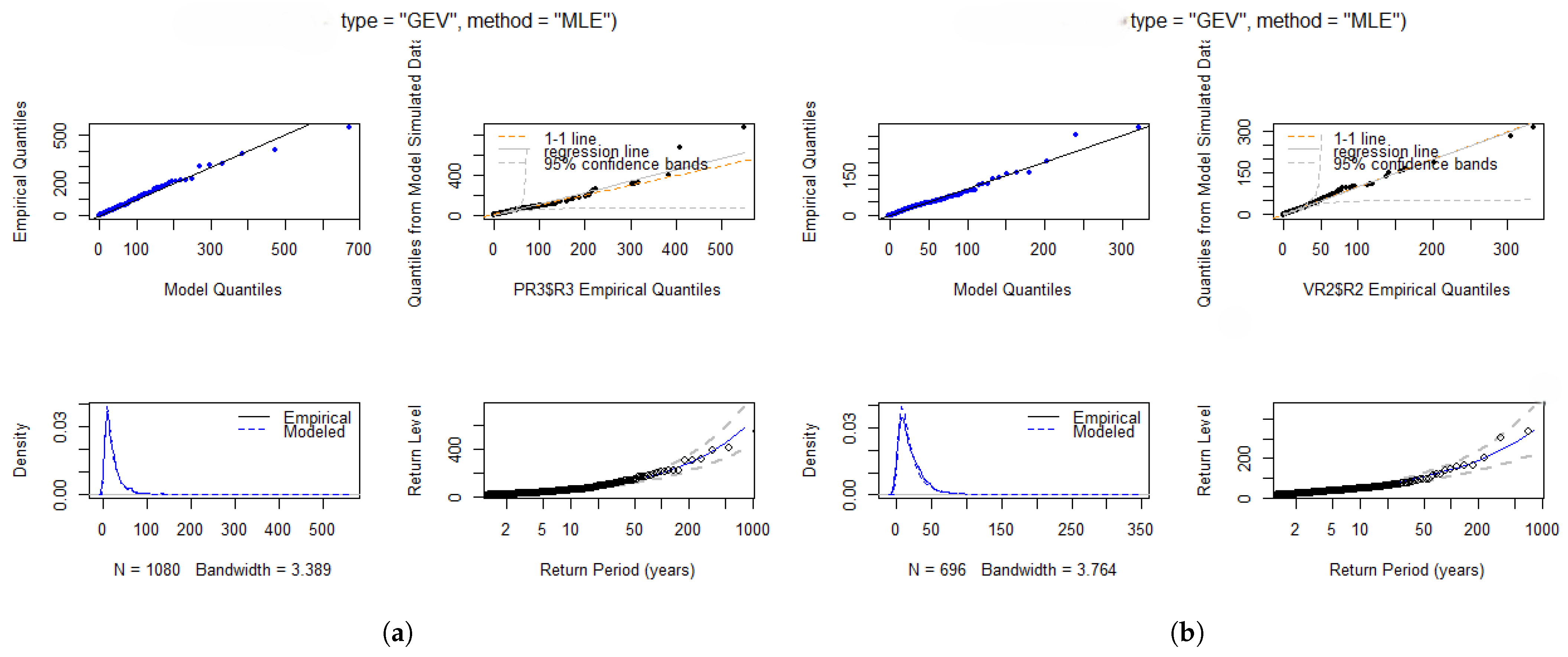

Figure 4 provides strong evidence of the goodness-of-fit, as there is a clear alignment in the P-P and Q-Q plots. The density plots show a compelling match between the fitted and empirical density curves, further reinforcing the model’s reliability. Additionally, the return level plots demonstrate a linear alignment, providing further evidence of the goodness-of-fit. Therefore, the GEVD model is appropriate for estimating the intensity and frequency of maximum rainfall at the Port Edward station, as supported by both the diagnostic plots and statistical tests.

Figure 4.

Diagnostic plots for Port Edward: (a) Diagnostic plots illustrating the fit of the data to the GEVD model for Port Edward station using MLE. (b) Diagnostic plots illustrating the fit of the data to the GEVD model for Port Edward station using Bayesian estimation.

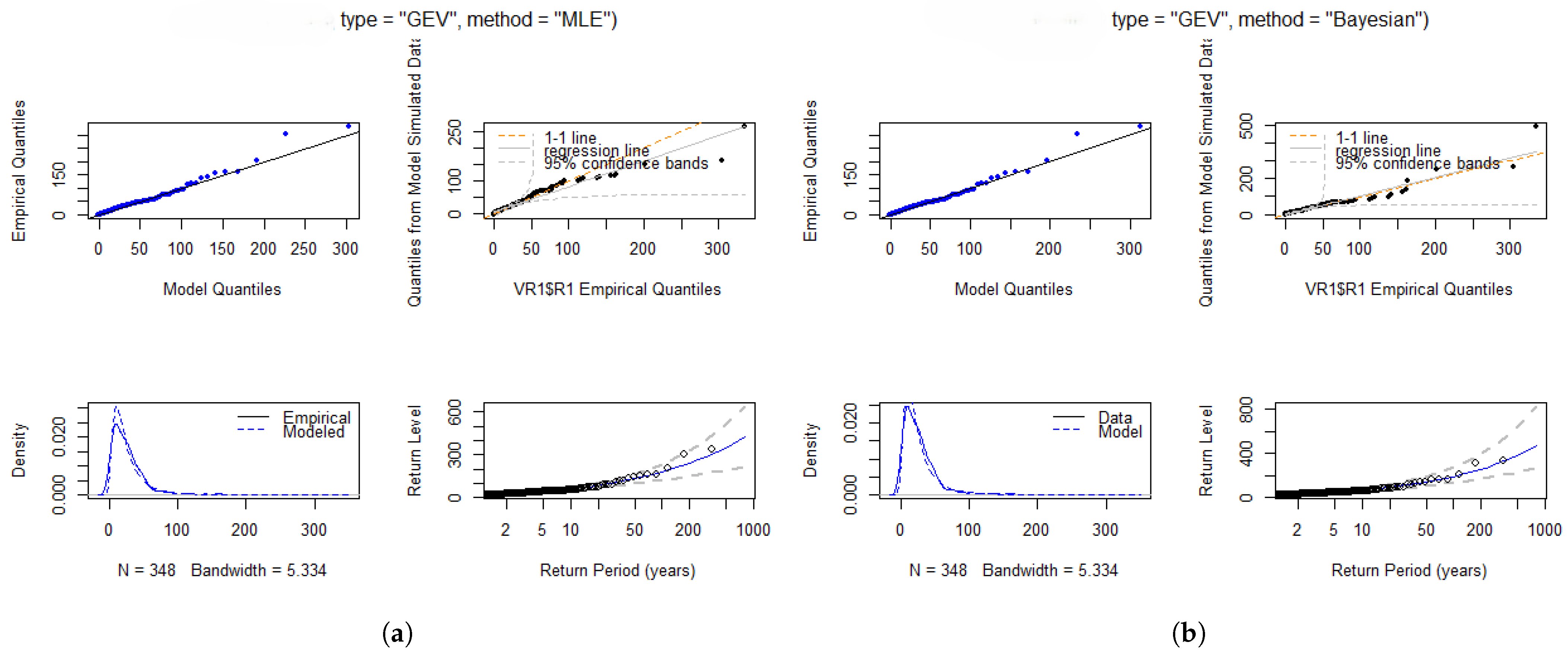

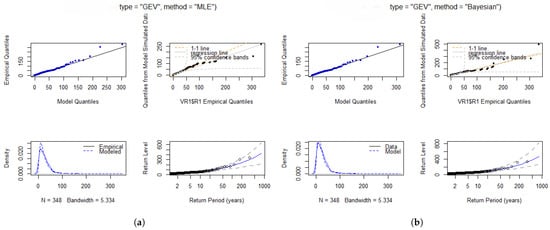

5.3.3. GEVD Diagnostic Plots for Virginia Station

Figure 5 presents diagnostic plots that further demonstrate the stability of the model in fitting the Virginia data. These diagnostic plots provide strong evidence that the data follow the GEVD, as indicated by the close alignment between the empirical data and the estimated model in the P-P and Q-Q plots. This alignment follows a straight line, with only a few minor deviations that are likely due to sample variability. The return level plot shows a clear increasing trend, with data points closely aligning with model estimates. Additionally, both figures show a strong match between the fitted model and empirical data in the density plot, further confirming the good fit. The density plots also reveal that the data exhibit a heavy tail, as indicated by the skewness in the distribution.

Figure 5.

Diagnostic plots for Virginia: (a) Diagnostic plots illustrating the fit of the data to the GEVD model for Virginia station using MLE. (b) Diagnostic plots illustrating the fit of the data to the GEVD model for Virginia station using Bayesian estimation.

5.3.4. Normality Test Results

Table 5 presents the results of the Shapiro–Wilk normality test, conducted to assess whether the data series from the two selected stations follow a normal distribution. However, as the GEVD focuses on modelling the behaviour of the maximum or minimum values in a dataset, particularly for capturing rare or extreme events in the tails, the data does not need to be normally distributed to fit the GEVD effectively.

Table 5.

Results for the Shapiro–Wilk normality test.

The data is statistically significant, as the p-values are below the established significance level (). These results provide sufficient evidence to conclude that the data of monthly rainfall from the two stations in Table 5 does not follow a normal distribution, supporting the alternative hypothesis. Unlike conventional statistical analyses that typically focus on central tendency (mean or median), the GEVD emphasises tail extremes [19].

5.3.5. Return Levels and Return Periods for GEVD

Table 6 presents the results for the return periods and their corresponding return levels for the maximum monthly rainfall data from two selected stations in the KwaZulu-Natal province. These tables provide estimates computed using both the MLE and Bayesian estimation methods. Additionally, the 95% confidence intervals for the return levels are included to assess whether the estimates obtained from both methods fall within the interval. According to the results of the GEVD presented in Table 6, the maximum rainfall records are expected to be exceeded at least once in a minimum of 100 years.

Table 6.

Return levels for the Port Edward and Virginia stations.

Notably, the results in Table 6 reveal that the return levels for each station increase with increasing return periods. The maximum rainfall values recorded at the two stations, Port Edward and Virginia, were 549.20 mm and 334.60 mm, respectively, as indicated in the descriptive statistics in Table 1. According to the GEVD model results (Table 6), these values are not expected to be exceeded within a return period of at least 250 years. However, it is observed that the return levels of maximum monthly rainfall continue to increase with longer return periods, suggesting the potential for more extreme rainfall events in the future.

5.4. R-Largest Order GEVD Modelling

This section presents the fitted model of the GEVD for the r-largest order statistics () across all selected candidate stations. Provided in this section are the parameter estimates in tables, diagnostic plots for assessing goodness-of-fit, and deviance statistics for model selection. The tables include estimates for the parameter of the GEVD (location (), scale (), and shape ()) along with their standard errors, 95% confidence intervals for the shape parameter, and negative log-likelihood (). The parameters were estimated using the maximum likelihood method.

Table 7 and Table 8 present estimates for the GEVD based on the r-largest order statistics. The estimates for the location parameters () and their standard errors (SE ()) decrease as the size of the r blocks of order statistics increases in both stations. A similar decreasing trend is observed for the scale parameter estimates (). A decreasing indicates that the central tendency of the extremes becomes lower as larger blocks are considered. The scale parameter (), which reflects the variability or spread of the extreme values being modelled, also shows a reduction in its estimates as r increases, indicating a decreasing spread of extreme values with larger block sizes.

Table 7.

Parameter estimates, standard errors, and negative log-likelihood of r-largest order statistics models fitted to monthly rainfall data in Port Edward station.

Table 8.

Parameter estimates, standard errors, and negative log-likelihood of r-largest order statistics models fitted to monthly rainfall data in Virginia station.

The shape parameter estimates () are positive and exhibit decreasing standard errors as r increases. The 95% confidence interval limits are non-negative, suggesting that the monthly maximum rainfall data at the two stations follow the Fréchet family of distribution, which characterises data with heavy tails. The reduction in standard errors for the shape parameter estimates (SE ()) with increasing block size suggests improved statistical stability and precision in estimating the shape parameter. The objective is to identify the optimal block size from the five blocks presented in Table 7 and Table 8. Diagnostic plots and deviance statistics are employed to further investigate and determine the most appropriate r.

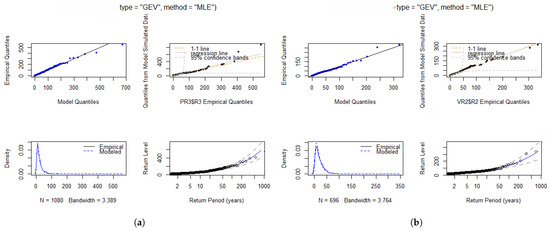

5.4.1. R-Largest Order GEVD Diagnostic Plots

Figure 6 presents the diagnostic plots for r = 3 and r = 2 for Port Edward and Virginia stations, respectively. The diagnostic plots demonstrate a reasonably good fit compared to the other figures for the respective stations. This conclusion is based on the alignment observed in the P-P plots, Q-Q plots, and the density plot, all of which exhibit better alignment relative to the other figures. The validity of these block sizes is further assessed using deviance statistics, which confirms that all these block sizes are valid. Therefore, based on the diagnostic plots, r = 3 and r = 2 can be considered as the appropriate block sizes for the respective stations. Refer to the deviance statistics results in Table 9 and Table 10.

Figure 6.

Diagnostic plots for both stations: (a) Diagnostic plots illustrating the fit of the data (monthly maximum rainfall data at Port Edward station) to the model with r = 3. (b) Diagnostic plots illustrating the fit of the data (monthly maximum rainfall data at Virginia station) to the model with r = 2.

Table 9.

The deviance statistics for Port Edward station.

Table 10.

The deviance statistics for Virginia station.

The critical value of the distribution is at the 5% significance level. The deviance statistics in Table 9 and Table 10 are compared against this critical value and are all greater than . This indicates that, at the 5% significance level, the test is significant, leading to the rejection of the for r = 1 through r = 5. These results confirm the log-likelihood estimates for the order statistics presented in Table 9 and Table 10 as valid. Based on both the deviance statistics test and the diagnostic plots, r = 3 and r = 2 are selected as the optimal order statistics for the two sampled stations, Port Edward and Virginia, respectively. The return levels for the optimal block sizes are presented in Table 11.

Table 11.

Return levels for both stations.

5.4.2. Return Levels and Return Periods Estimates for r-Largest Order GEVD

The return levels and return periods, along with their respective 95% confidence intervals, are presented in Table 11. Port Edward station exhibits relatively higher return levels from the 15-year return period onwards in comparison with Virginia station.

5.5. bGEVD Modelling

Research on the application of the bGEVD model is scarce. Vandeskog et al. [18] noted that the bGEVD is appropriate for modelling heavy-tailed extremes only when the shape parameter is greater than zero (). Similarly, [39] acknowledges the limited application of this model and its associated constraints. Therefore, the lack of comprehensive knowledge on bGEVD represents a significant research gap that the current study attempts to address.

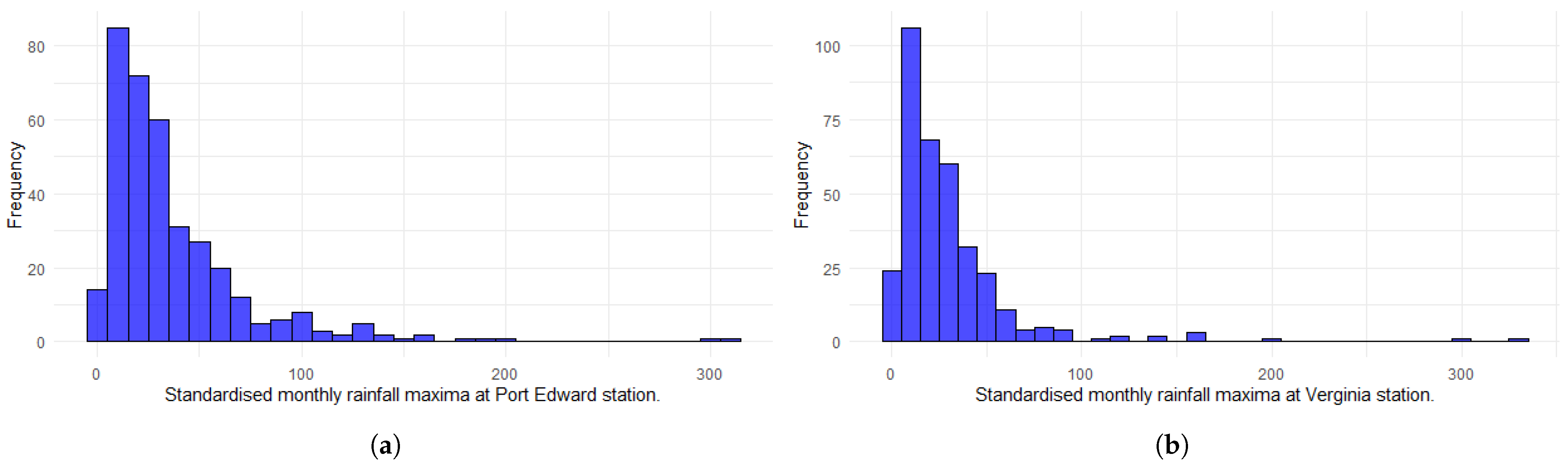

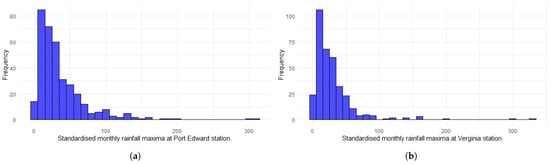

In this study, the monthly rainfall maxima from two selected stations were used to model the bGEVD. Ref. [18] emphasised that before applying the bGEVD model it is essential to standardise explanatory variables to have a mean of zero and standard deviation of one. Figure 7 illustrates the standardised monthly maxima of the selected stations used in the modelling process. According to [17], the parametrisation of the blended GEVD allows for the interpretation of the location () and spread () parameters, even when the mean and variance are unknown. The R-INLA package is used to implement the bGEVD model.

Figure 7.

The standardised monthly rainfall maxima for both stations: (a) Histogram for Port Edward station in millimetres (mm). (b) Histogram for Virginia station in millimetres (mm).

Table 12 presents the results for the selected stations, including the bGEVD intercept, hyperparameters ( and ), explanatory variables (such as the monthly rainfall maxima), and the corresponding regression coefficients ( and ). According to [17,39], the explanatory variables have a greater effect on the location parameter. There is a negative linear trend, indicating a decrease in rainfall maxima over time. As a result, a decline in rainfall maxima estimates is expected, accompanied by increased variance in the distribution of extreme values.

Table 12.

bGEVD parameter estimates for Port Edward and Virginia stations.

bGEVD Return Level Estimates

Table 13 presents the return levels and their corresponding return periods for the selected stations. Notably, the return levels estimated by the bGEVD model are significantly lower compared to those of the GEVD and GEVD for r-largest statistics. In Table 1, which presents descriptive statistics, the maximum recorded rainfall values for the sampled stations are as follows: Port Edward (549.20 mm) and Virginia (334.60 mm). These observed maximum values exceed the estimated return levels for a 250-year return period using the bGEVD model for both the stations. This indicates that, under the bGEVD model, none of the stations are expected to surpass their historically recorded maximum rainfall values, suggesting that the model produces significantly lower return level estimates.

Table 13.

bGEVD return level estimates for Port Edward and Virginia stations.

For instance, the 250-year return level for the Port Edward station is estimated at 283.4005 mm, implying that this amount of rainfall is expected to be exceeded at least once in 250 years. This interpretation applies to the other selected station, given that the highest return period in Table 13 is 250 years. A key insight from these results is that the bGEVD model appears to underfit the data, as its return level estimates are not comparable to the observed maximum values. This underestimation may be attributed to the hyperparameters derived from the blended distributions that form the bGEVD model or to data quality issues, particularly the presence of missing values in the dataset. However, this discrepancy presents an opportunity for future research to further investigate the underlying factors driving these differences in estimations.

6. Discussion and Conclusions

This study presented a comparative analysis of advanced extreme value theory models, specifically the GEVD for r-largest order statistics and the bGEVD, applied to two meteorological stations in the KwaZulu-Natal province. The stations used in the study are Port Edward and Virginia. Data for these stations was provided by the South African Weather Service (SAWS). Prior to analysis, the data was cleaned and blocked into five blocks of maxima to facilitate the application of the r-largest GEVD method for order statistics.

The GEVD was fitted to each of the two stations. The MLE and Bayesian estimation methods were used to estimate the three parameters of the GEVD. The estimated parameters obtained from both methods were found to be relatively similar. Both approaches yielded positive values for the shape parameter, indicating that the Fréchet distribution is the most appropriate among the three GEVD classes. These findings were further validated by the confidence intervals of the shape parameter across all stations.

The GEVD for r-largest order statistics was fitted to the five largest blocks of maxima, consisting of rainfall values for each station. The MLE was used for parameter estimation, diagnostic plots were employed to assess the goodness of fit, and deviance statistics were utilised for model selection. The 95% confidence interval for the shape parameter suggests that a distribution within the Fréchet domain of attraction can effectively model the data from both stations.

The optimal block size for Port Edward was determined to be , and was determined to be the optimal block size for the Virginia station. The selection of the optimal block size is supported by the alignment of diagnostic plots with deviance test results, both of which confirm this conclusion. The return levels and their corresponding return periods were computed. The return levels obtained from the standard GEVD model and the GEVD for the r-largest order statistics model were found to be closely comparable and relatively consistent.

The bGEVD model was fitted to the time series data from the two stations of interest in the study area, KwaZulu-Natal province. The results suggest a negative time trend in the explanatory variables, indicating a decline in rainfall maxima over time. This decrease in rainfall maxima influences the parameter estimates, resulting in significantly lower return levels for the bGEVD model compared to the two previously fitted models: the standard GEVD and the GEVD for r-largest order statistics.

The assessment of the return levels for the modelling techniques employed in the current study is crucial for comparative analysis. Return levels provide invaluable insights into the statistical characteristics of extreme events. The findings regarding the return levels and their corresponding return periods are vital for performing accurate extreme value analysis and for determining the appropriate model for prediction and disaster assessment. Based on the findings of the study, the two comparable models, the standard GEVD and the GEVD for r-largest order statistics, produce consistent results and therefore adequately model extreme rainfall in the KwaZulu-Natal province. Similar findings were obtained in by [36], which focused on modelling the maximum average daily temperature in South Africa. In contrast, bGEVD yields lower return levels and its results are inconsistent with those obtained from the GEVD and GEVD for r-largest order statistics.

Future Research

The findings of this study suggest that higher rainfall events with increased intensity and frequency may occur in the future within the KwaZulu-Natal province. Based on these results, the study proposes several future research directions that could help improve the accuracy and reliability of extreme rainfall models.

The current research focused exclusively on the KwaZulu-Natal province using EVT models such as the GEVD, the GEVD for r-largest order statistics, and the bGEVD. Future researchers are encouraged to apply advanced EVT models, such as the Kappa four-parameter distribution for r-largest (K4Dr), which may offer improved accuracy in extreme event modelling. Although the bGEVD model was employed in this study to analyse extreme floods, it was acknowledged that there are still limitations and a lack of extensive literature on the model. Therefore, future researchers are encouraged to further explore and refine the application of the bGEVD to contribute to the growing body of knowledge in the EVT field.

Additionally, this study found that Bayesian estimation methods slightly outperformed MLE in forecasting accuracy. Thus, it is recommended that future research should prioritise Bayesian methods, incorporating expert knowledge into estimation and forecasting processes for more robust results. Finally, while this study was confined to the KwaZulu-Natal province, future research should consider expanding the scope to cover all nine provinces of South Africa, using the suggested models. Such broader studies would offer better assessments of severe weather events and contribute valuable insights for policymakers to facilitate effective disaster mitigation strategies.

We acknowledge that the impacts of extremes can be mitigated through early warning systems and appropriate infrastructure, such as effective drainage networks; however, the complete elimination of natural hazards is beyond human capacity. Accordingly, the primary objective of this study is to address a methodological gap rather than to provide mitigation or preparedness guidance. Specifically, the study aims to conduct a comparative evaluation of model performance using applied data, namely rainfall observations. While some of the literature cited discusses mitigation strategies, this is not the primary focus of the present work.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, H.L., D.M. and S.S.N.; methodology, D.M.; software, H.L.; validation, H.L., D.M. and S.S.N.; formal analysis, H.L. and D.M.; investigation, H.L., D.M. and S.S.N.; resources, H.L., D.M. and S.S.N.; data curation, H.L.; writing—original draft preparation, H.L., D.M. and S.S.N.; writing—review and editing, H.L., D.M. and S.S.N.; visualisation, H.L., D.M. and S.S.N.; supervision, D.M. and S.S.N.; project administration, H.L., D.M. and S.S.N.; funding acquisition, D.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The monthly rainfall data for the KwaZulu-Natal province was obtained from the South African Weather Service (SAWS). This valuable rainfall dataset comprises time series data, measured in millimetres (mm). The data is meticulously categorised into various stations located within the province, ensuring a comprehensive representation of the region. The data requested covers a period of 72 years, from 1950 to 2022.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the South African Weather Services (SAWS) for providing this study with data, the University of Limpopo for funding the article processing charges, and the reviewers for their valuable feedback and comments. During the preparation of this manuscript/study, the author(s) used LaTeX Editor Overleaf for the purpose of document coding and R programming language for the purpose of data analysis. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Chen, H.; Xu, Z.; Chen, J.; Liu, Y.; Li, P. Joint Risk Analysis of Extreme Rainfall and High Tide Level Based on Extreme Value Theory in Coastal Area. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 3605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bopape, M.-J.M.; Sebego, E.; Ndarana, T.; Maseko, B.; Netshilema, M.; Gijben, M.; Landman, S.; Phaduli, E.; Rambuwani, G.; Van Hemert, L.; et al. Evaluating South African weather service information on idai tropical cyclone and KwaZulu-natal flood events. S. Afr. J. Sci. 2021, 117, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyrrdal, A.V.; Lenkoski, A.; Thorarinsdottir, T.L.; Stordal, F. Bayesian hierarchical modeling of extreme hourly precipitation in Norway. Environmetrics 2015, 26, 89–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Y.; Park, J.-S. Modeling climate extremes using the four-parameter Kappa distribution for r-largest order statistics. Weather Clim. Extrem. 2023, 39, 100533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, D.; Athulya, R.; Chakraborty, T.; Ray, A.; Hens, C.; Dana, S.K.; Ghosh, D.; Murukesh, N. Pattern change of precipitation extremes in Svalbard. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 8754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Njogu, H.W. Effects of floods on infrastructure users in Kenya. J. Flood Risk Manag. 2021, 14, e12746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayantan, N.C.; Arnob, R.; Syamal, K.D.; Dibakar, G. Extreme events in dynamical systems and random walkers: A review. Phys. Rep. 2022, 966, 1–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonathan, A.; Owolabi, M.T.; Olatunji, I.B.; Duntoye, B.T.; Henshaw, E.E. Economic analysis of the effect of flood disaster on food security of arable farming households in Southern Guinea Savanna Zone, Nigeria. J. Agric. Food Sci. 2020, 18, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramakrishna, G.; Gaddam, S.R.; Daisy, I. Impact of Floods on Food Security and Livelihoods of IDP tribal households: The case of Khammam region of India. Int. J. Dev. Econ. Sustain. 2014, 2, 11–24. [Google Scholar]

- Boudrissa, N.; Cheraitia, H.; Halimi, L. Modelling maximum daily yearly rainfall in northern Algeria using generalized extreme value distributions from 1936 to 2009. Meteorol. Appl. 2007, 24, 114–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kajambeu, R. Modelling Floods Heights of the Limpopo River at Beitbridge Border Post Using Extreme Value Distribution. Master’s Thesis, University of Venda, Thohoyandou, South Africa, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Naidoo, K.; Manyangadze, T.; Lokotola, C.L. Primary care disaster management for extreme weather events, South Africa. Afr. J. Prim. Health Care Fam. Med. 2022, 14, 3778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- du Plessis, J.A.; Burger, G.J. Investigation into increasing short-duration rainfall intensities in South Africa. Water SA 2015, 41, 416–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mothupi, T.; Thupeng, W.M.; Mashabe, B.; Mokoto, B. Estimating extreme quantiles of the maximum surface air temperatures for the Sir Seretse Khama International Airport using the Generalized Extreme Value Distribution. Am. J. Theor. Appl. Stat. 2016, 5, 365–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNicol, G.; Silver, W.L. Separate effects of flooding and anaerobiosis on soil greenhouse gas emissions and redox sensitive biogeochemistry. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 2014, 119, 557–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coles, S. An Introduction to Statistical Modelling of Extreme Values; Springer: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Castro-Camilo, D.; Huser, R.; Rue, H. Practical strategies for generalized extreme value-based regression models for extremes. Environmetrics 2022, 33, e2742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandeskog, S.M.; Martino, S.; Castro-Camilo, D.; Rue, H. Modelling sub-daily precipitation extremes with the blended generalised extreme value distribution. J. Agric. Biol. Environ. Stat. 2022, 27, 598–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maposa, D.; Seimela, A.M.; Sigauke, C.; Cochran, J.J. Modelling temperature extremes in the Limpopo province: Bivariate time-varying threshold excess approach. Nat. Hazards 2021, 107, 2227–2246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, A.; de Haan, L. On the block maxima method in extreme value theory: PWM estimators. Ann. Stat. 2015, 43, 276–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabari, H. Extreme value analysis dilemma for climate change impact assessment on global flood and extreme precipitation. J. Hydrol. 2021, 593, 125932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miniussi, A.; Marani, M.; Villarini, G. Metastatistical Extreme Value Distribution applied to floods across the continental United States. Adv. Water Resour. 2020, 136, 103498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasiliades, L.; Galiatsatou, P.; Loukas, A.J.W.R.M. Nonstationary frequency analysis of annual maximum rainfall using climate covariates. Water Resour. Manag. 2015, 29, 339–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maposa, D.; Lesaoana, M.; Cochran, J.J. Modelling non-stationary annual maximum flood heights in the lower Limpopo River basin of Mozambique. Jàmbá J. Disaster Risk Stud. 2016, 8, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maposa, D.; Cochran, J.J.; Lesaoana, M.; Sigauke, C. Estimating high quantiles of extreme flood heights in the lower Limpopo River basin of Mozambique using model based Bayesian approach. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. Discuss. 2014, 2, 5401–5425. [Google Scholar]

- Champman, S.; Bacon, J.; Birch, C.E.; Pope, E.; Marsham, J.H.; Msemo, H.; Nkonde, E.; Sinachikupo, K.; Vanya, C. Climate Change Impacts on Extreme Rainfall in Eastern Africa in a Convection-Permitting Climate Model. J. Clim. 2023, 36, 93–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chikobvu, D.; Chifurira, R. Modelling of extreme minimum rainfall using generalised extreme value distribution for Zimbabwe. S. Afr. J. Sci. 2015, 111, 01–08. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, J.; Adam, M.B. Modeling of magnitude and frequency of extreme rainfall in Somalia. Model. Earth Syst. Environ. 2022, 8, 4277–4294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikhwari, T.; Nethengwe, N.; Sigauke, C.; Chikoore, H. Modelling of extremely high rainfall in Limpopo Province of South Africa. Climate 2022, 10, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diriba, T.A.; Debusho, L.K. Spatio-temporal dependence modelling of extreme rainfall in South Africa: A Bayesian integrated nested Laplace approximation technique. Commun. Stat. Case Stud. Data Anal. Appl. 2023, 9, 152–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singo, L.R.; Kundu, P.M.; Mathivha, F.I.; Odiyo, J.O. Evaluation of flood risks using flood frequency models: A case study of Luvuvhu River catchment in Limpopo Province, South Africa. WIT Trans. Built Environ. 2016, 165, 215–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjeldsen, T.R.; Smithers, J.C.; Schulze, R.E. Regional flood frequency analysis in the KwaZulu-Natal province, South Africa, using the index-flood method. WIT Trans. Built Environ. 2002, 255, 194–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maposa, D. Statistics of Extreme with Applications to Extreme Flood Heights in the Lower Limpopo River Basin of Mozambique. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Limpopo, Polokwane, South Africa, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Seimela, A.M. Modelling Temperature Extremes in the Limpopo Province of South Africa Using Extreme Value Theory. Master’s Thesis, University of Limpopo, Polokwane, South Africa, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Beirlant, J.; Goegebeur, Y.; Segers, J.; Teugels, J.L. Statistics of Extremes: Theory and Applications; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Nemukula, M.M.; Sigauke, C. Modelling average maximum daily temperature using r largest order statistics: An application to South African data. Jàmbá J. Disaster Risk Stud. 2018, 10, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mashishi, D. Modeling Average Monthly Rainfall for South Africa Using Extreme Value Theory. Master’s Thesis, University of Limpopo, Polokwane, South Africa, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, E. Bayesian Modelling of Extreme Rainfall Data. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Newcastle upon Tyne, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Metwane, M.K.; Maposa, D. Extreme Value Theory Modelling of the Behaviour of Johannesburg Stock Exchange Financial Market Data. Int. J. Financ. Stud. 2023, 11, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L. Extreme Event Modelling. 2014. Available online: http://personal.cityu.edu.hk/xizhou/liwei-wus-slides.pdf (accessed on 20 May 2025).

- Ahmad, I.; Ahmad, T.; Almanjahie, I.M. Modelling of extreme rainfall in Punjab: Pakistan using Bayesian and frequentist approach. Appl. Ecol. Environ. Res. 2019, 17, 13729–13748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephenson, A.G.; Ribatet, M.A. A Users Guide to the Evdbayes Package (V 1.1). 2006. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/evdbayes/evdbayes.pdf (accessed on 21 May 2025).

- Iyamuremye, E.; Mung’atu, J.; Mwita, P. Extreme value modelling of rainfall using Poisson-generalized Pareto distribution: A case study Tanzania. Int. J. Stat. Distrib. Appl. 2019, 5, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Nelder, J.A.; Wedderburn, R.W.M. Generalized linear models. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. A Stat. Soc. 1972, 135, 370–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engmann, S.; Cousineau, D. Comparing distributions: The two-sample Anderson-Darling test as an alternative to the Kolmogorov-Smirnoff test. J. Appl. Quant. Methods 2011, 6, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Sukla, M.K.; Mangaraj, A.K.; Sahoo, L.N. An investigation on the stochastic modeling of daily rainfall amount in the Mahandi Delta region, India. Res. J. Math. Stat. Sci. 2014, 2, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- de Souza, R.R.; Toebe, M.; Mello, A.C.; Bittencourt, K.C. Sample size and Shapiro-Wilk test: An analysis for soybean grain yield. Eur. J. Agron. 2023, 142, 126666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razali, N.M.; Wah, Y.B. Power comparisons of Shapiro-Wilk, Kolmogorov-Smirnov, Lilliefors and Anderson-Darling tests. J. Stat. Model. Anal. 2011, 2, 21–33. [Google Scholar]

- Chifurira, R. Modelling Mean Annual Rainfall for Zimbabwe. Ph.D. Thesis, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein, South Africa, 2018. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.