Eigenstructure-Oriented Optimization Design of Active Suspension Controllers

Abstract

1. Introduction

- An eigenstructure-oriented optimization framework is developed for active suspension systems. This framework provides a physically interpretable means of regulating structural dynamics and enables targeted modal control to enhance vibration isolation performance.

- A performance-constrained optimization strategy is established to enhance suspension performance while limiting control effort, ensuring that ride comfort enhancement is achieved in parallel with reduced gain magnitude and energy consumption.

2. System Modeling

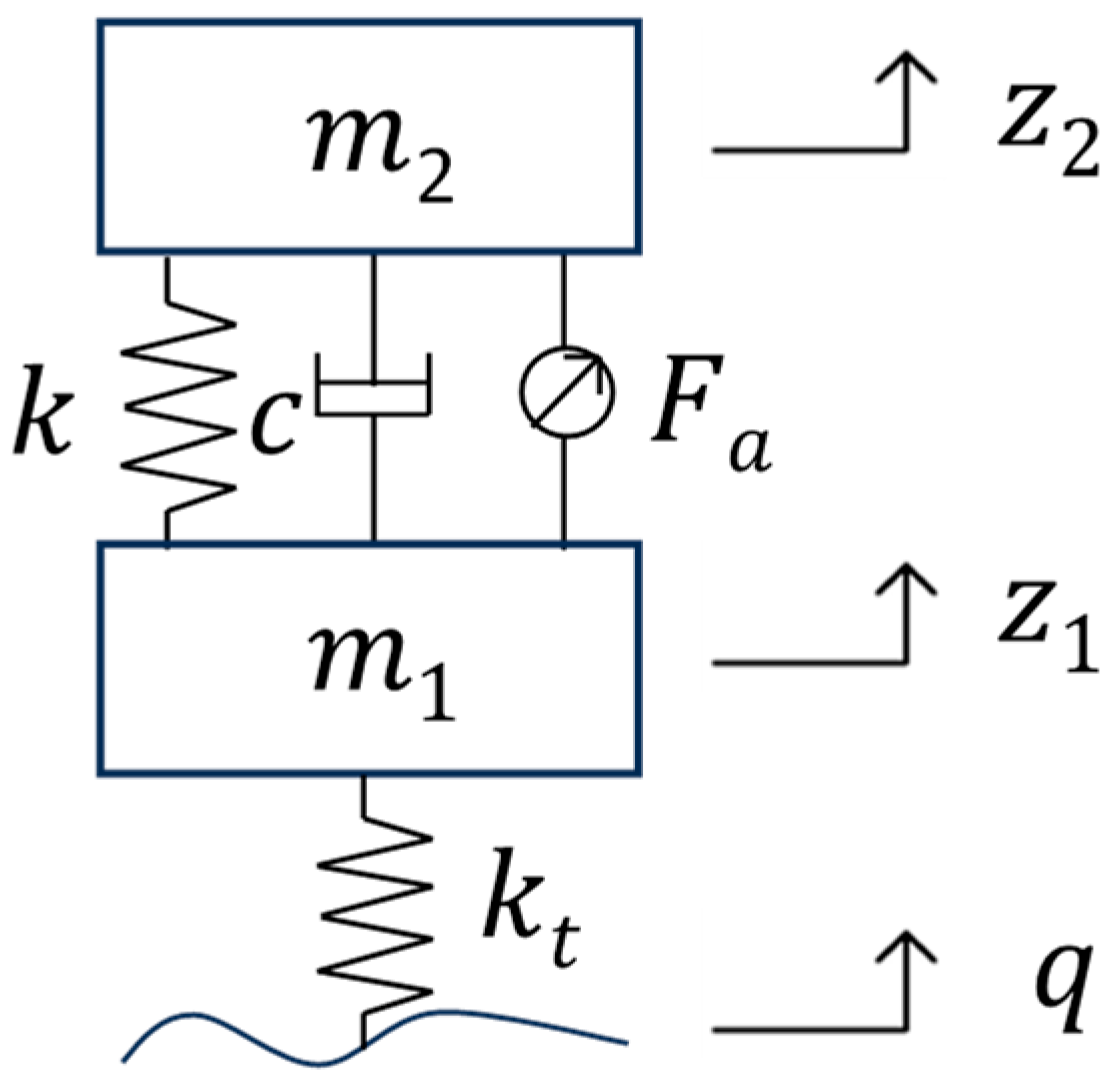

2.1. Mathematical Modeling of Active Suspension

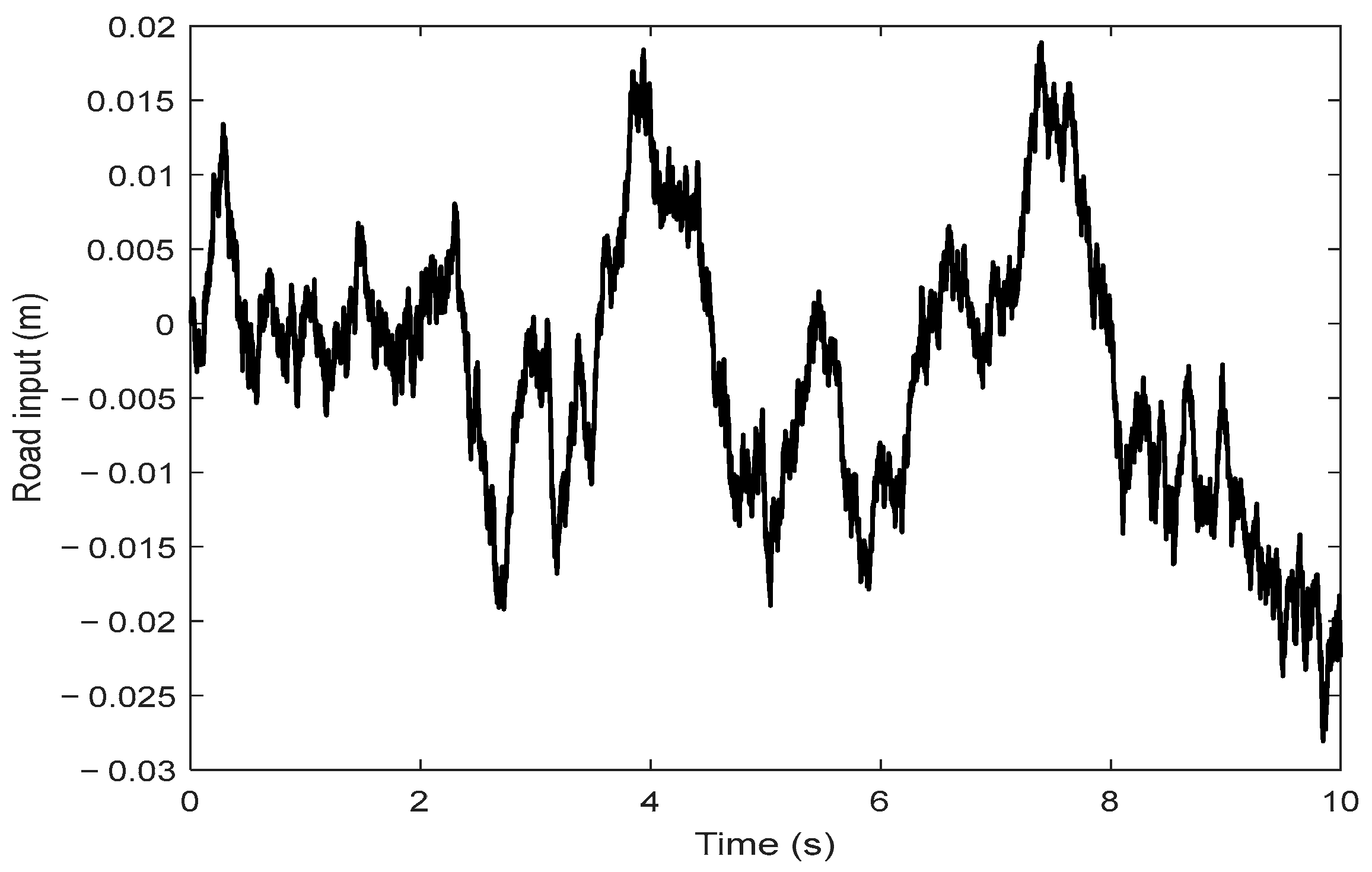

2.2. Road Excitation Modeling

3. Theory and Methodology

3.1. Theory of Eigenstructure Assignment

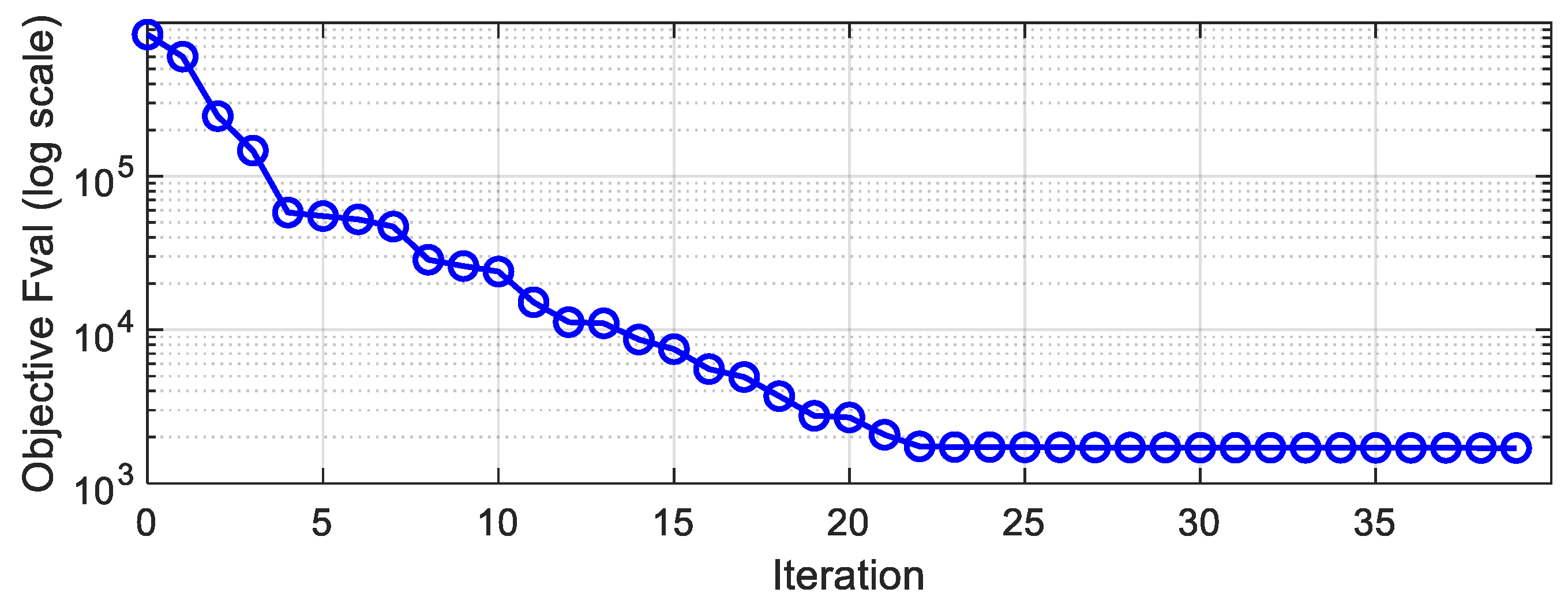

3.2. Dynamic Response Optimization Approach

- (1)

- Define the eigenvalues to be reassigned and those to be retained;

- (2)

- Select the design variables (the predefined vectors and the system eigenvalues ) together with the performance indices, and establish the corresponding mathematical optimization model;

- (3)

- Assign initial values to the design variables and compute the initial controller gain matrices using the partial eigenstructure assignment method;

- (4)

- Substitute the gain matrices into the system dynamic equations and perform a time-domain response analysis using the fourth-order Runge–Kutta method;

- (5)

- Iteratively update the design variables using the SQP algorithm until convergence to the optimal solution.

4. Numerical Example

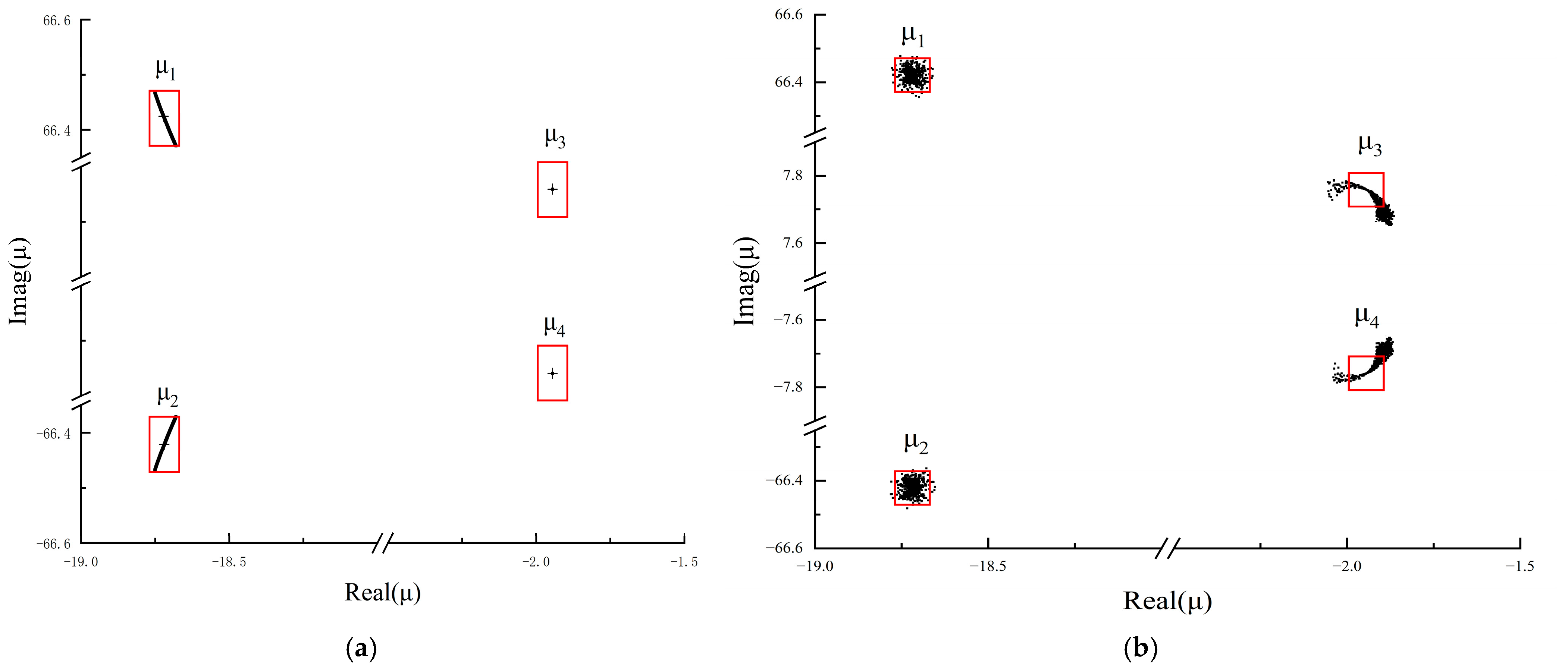

5. Robustness Analysis

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dandavate, K.D. A Review on Controlling Methods for Active Suspension Systems. Int. J. Res. Appl. Sci. Eng. Technol. 2023, 11, 1675–1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goga, V.; Kľúčik, M. Optimization of Vehicle Suspension Parameters with Use of Evolutionary Computation. Procedia Eng. 2012, 48, 174–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, F.; Wang, B.; Liu, M. Research on LQR Control of Vehicle Active Suspension. Mach. Des. Res. 2020, 36, 52–55. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Z.; Wang, C.; Zhao, J.; Du, W. LQR Force Command Planning Based Sliding Mode Control for Active Suspension System. J. Syst. Control Eng. 2024, 238, 373–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abut, T.; Salkim, E. Control of Quarter-Car Active Suspension System Based on Optimized Fuzzy Linear Quadratic Regulator Control Method. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 8802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Başak, H. Hybrid Coati–Grey Wolf Optimization with Application to Tuning Linear Quadratic Regulator Controller of Active Suspension Systems. Eng. Sci. Technol. Int. J. 2024, 56, 101765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parvez, Y.; Chauhan, N.R.; Srivastava, M. Vibration Control and Comparative Analysis of Passive and Active Suspension Systems Using PID Controller with Particle Swarm Optimization. J. Inst. Eng. India Ser. C 2025, 106, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abut, T.; Salkim, E.; Demosthenous, A. Performance Improvement in a Vehicle Suspension System with FLQG and LQG Control Methods. Actuators 2025, 14, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Jia, C.; Cheng, L.; Zhao, Q. Constrained State Feedback H∞ Control of Active Suspension System for In-Wheel Motor Electric Vehicles. J. Jilin Univ. Eng. Technol. 2021, 53, 1521–1529. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, X.; Zhou, L.; Zhang, M.; Jiang, H.; Liu, W.; Hu, J. Sliding Mode Adaptive Control of Active Suspension System Combined with Particle Filter State Observation. J. Hunan Univ. Nat. Sci. 2024, 51, 19–27. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Y.; Peng, J. Adaptive Fault-Tolerant Control of Active Suspension Systems Considering Input and Output Constraints. Control Decis. 2025, 40, 693–698. [Google Scholar]

- Lyu, B.; Zhang, R. Semi-Active Air Suspension System Based on Fuzzy PID Control. Mach. Des. Manuf. 2025, 5, 79–84. [Google Scholar]

- Chantranuwathana, S.; Peng, H. Adaptive Robust Force Control for Vehicle Active Suspensions. Int. J. Adapt. Control Signal Process. 2004, 18, 83–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, X.; Liu, W.; Yang, Y.; Lu, J. Adaptive Finite-Time Fuzzy Control for Nonlinear Systems with Input Quantization and Unknown Time Delays. J. Frankl. Inst. 2020, 357, 7718–7742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Gao, H.; Yao, B. Adaptive Robust Vibration Control of Full-Car Active Suspensions with Electrohydraulic Actuators. IEEE Trans. Control Syst. Technol. 2013, 21, 2417–2422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, X.; Li, Y.; Tong, S. Adaptive Fuzzy Output Feedback Inverse Optimal Control for Vehicle Active Suspension Systems. Neurocomputing 2020, 403, 257–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Zhao, D.; Yang, B.; Han, C. Fractional-Order Control of Active Suspension Actuator Based on Parallel Adaptive Clonal Selection Algorithm. J. Mech. Sci. Technol. 2016, 30, 2769–2781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piao, C.; Liu, X.; Lu, C. Lateral Control Using Parameter Self-Tuning LQR on Autonomous Vehicle. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Intelligent Computing, Automation and Systems (ICICAS), Chongqing, China, 6–8 December 2019; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 913–917. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q.; Chen, Z.; Song, H.; Dong, Y. Model Predictive Control for Speed-Dependent Active Suspension System with Road Preview Information. Sensors 2024, 24, 2255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.H.; Ahmad, N.S. Enhanced Fuzzy Logic Control for Active Suspension Systems via Hybrid Water Wave and Particle Swarm Optimization. Int. J. Control Autom. Syst. 2025, 23, 560–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Zhang, H.; Sui, S. Observer-Based Adaptive Neural Network Event-Triggered Quantized Control for Active Suspensions with Actuator Saturation. Neurocomputing 2025, 614, 128770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, T.; Liu, W.; Tong, S. Neural Network Adaptive Output-Feedback Optimal Control for Active Suspension Systems. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 2021, 51, 4021–4032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Cui, X.; Zhao, S.; Zhou, X.; Song, Y.; Wang, Y.; Guo, K. A Deep Reinforcement Learning-Based Active Suspension Control Algorithm Considering Deterministic Experience Tracing for Autonomous Vehicle. Appl. Soft Comput. 2024, 153, 111259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Du, Y.; Han, S.; Zhao, W.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, T.; Chen, C.L.P. Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning for Vibration Control of Regenerative Active Suspension. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2025, 153, 110809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abut, T.; Salkim, E.; Tugal, H. Active Suspension Control for Improved Ride Comfort and Vehicle Performance Using HHO-Based Type-I and Type-II Fuzzy Logic. Biomimetics 2025, 10, 673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mottershead, J.E.; Friswell, M.I. Model Updating in Structural Dynamics: A Survey. J. Sound Vib. 1993, 167, 347–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belotti, R.; Richiedei, D. Dynamic Structural Modification of Vibrating Systems Oriented to Eigenstructure Assignment through Active Control: A Concurrent Approach. J. Sound Vib. 2018, 422, 358–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ram, Y.M.; Mottershead, J.E. Multiple-Input Active Vibration Control by Partial Pole Placement Using the Method of Receptances. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2013, 40, 727–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richiedei, D.; Tamellin, I.; Trevisani, A. Pole–Zero Assignment by the Receptance Method: Multi-Input Active Vibration Control. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2022, 172, 109108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamson, L.J.; Fichera, S.; Mottershead, J.E. Receptance-Based Robust Eigenstructure Assignment. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2020, 140, 106666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariyatanapol, R.; Xiong, Y.P.; Ouyang, H. Partial Pole Assignment with Time Delays for Asymmetric Systems. Acta Mech. 2018, 229, 2619–2629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Ouyang, H. Receptance-Based Partial Eigenstructure Assignment by State Feedback Control. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2022, 168, 108682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richiedei, D.; Tamellin, I.; Trevisani, A. Unit-Rank Output Feedback Control for Antiresonance Assignment in Lightweight Systems. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2022, 164, 108286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 8608:2016; Mechanical Vibration. Road Surface Profiles. Reporting of Measured Data. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016. Available online: https://cdn.standards.iteh.ai/samples/71202/05b2151f255b44928f80acb897fc0c2c/ISO-8608-2016.pdf (accessed on 5 November 2025).

| Road Surface Class | (×10−6 m3) |

|---|---|

| A | 16 |

| B | 64 |

| C | 256 |

| D | 1024 |

| E | 4096 |

| F | 16,384 |

| Parameter | Symbol | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sprung mass | 317 | kg | |

| Unsprung mass | 45 | kg | |

| Suspension stiffness | 22,000 | N/m | |

| Suspension damping coefficient | 1500 | Ns/m | |

| Tire stiffness | 192,000 | N/m |

| Category | Variable | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Eigenvalues (Y) | −1.9450 ± 7.7588i | |

| −18.7191 ± 66.4209i | ||

| Predefined Vectors (X) | −0.0104/0.7042 | |

| 0.8754/0.0933 |

| Performance Metric | Passive Suspension | PID Active Suspension | Proposed Active Suspension |

|---|---|---|---|

| Peak body acceleration (m/s2) | 3.4771 | 1.0589 | 1.6990 |

| RMS of body acceleration | 0.7358 | 0.4459 | 0.4003 |

| Peak body displacement (m) | 0.02568 | 0.02415 | 0.02359 |

| RMS of body displacement | 0.01240 | 0.01246 | 0.01143 |

| RMS of suspension deflection | 0.00591 | 0.00939 | 0.00605 |

| Weighted RMS Acceleration | Perceived Comfort Level |

|---|---|

| <0.315 | Not uncomfortable |

| 0.315~0.63 | Slightly uncomfortable |

| 0.5~1.0 | Fairly uncomfortable |

| 0.8~1.6 | Uncomfortable |

| 1.25~2.5 | Very uncomfortable |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Du, Y.; Mao, H. Eigenstructure-Oriented Optimization Design of Active Suspension Controllers. Math. Comput. Appl. 2026, 31, 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/mca31010005

Du Y, Mao H. Eigenstructure-Oriented Optimization Design of Active Suspension Controllers. Mathematical and Computational Applications. 2026; 31(1):5. https://doi.org/10.3390/mca31010005

Chicago/Turabian StyleDu, Yulong, and Huping Mao. 2026. "Eigenstructure-Oriented Optimization Design of Active Suspension Controllers" Mathematical and Computational Applications 31, no. 1: 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/mca31010005

APA StyleDu, Y., & Mao, H. (2026). Eigenstructure-Oriented Optimization Design of Active Suspension Controllers. Mathematical and Computational Applications, 31(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/mca31010005