Abstract

Urban catchments are increasingly vulnerable to hydrologic extremes driven by land-use change and climate variability, challenging the traditional assumption of stationarity. This study develops a computational framework to assess the nonstationary behavior of peak flow, volume, and duration in an urban catchment in the Philippines using 39 years of daily flow records (June 1984–November 2022). Missing observations (~8% of the series) were reconstructed using multiple linear regression (MLR) and artificial neural networks (ANNs) with four predictors: daily rainfall, antecedent rainfall, antecedent flow, and built-up area index. MLR with all predictors yielded the most accurate reconstructions. Nonstationarity was detected using the Mann–Kendall test, Sen slope estimator, Pettitt test, and variance change test. Flood events were extracted using block maxima (BM) and peak-over-threshold (POT) methods. BM-based results showed stationary peak flow and volume, while duration increased by 1.78 h/year. POT analyses revealed nonstationarity across all variables, without significant shifts in variance. These findings demonstrate that methodological choices strongly influence nonstationary detection. The framework underscores the importance of reliable data reconstruction and robust statistical testing for nonstationary analysis of flood events. POT-based approaches more effectively capture evolving trends in peak flow, volume, and duration. These can be used in designing resilient infrastructure and flood risk management in urbanizing catchments.

1. Introduction

Climate change is subjecting river catchments to increasingly variable hydrologic extremes. In urban areas, these effects are intensified by rapid land-use change, which alters hydrologic response and heightens flood risk [1,2]. Under such conditions, the long-standing assumption of stationarity in flow analysis, where the statistical properties of hydrologic records are considered constant over time, has become unreliable [3]. Detecting and accounting for nonstationarity in flow records is therefore essential for developing accurate and robust flood risk assessments [4].

The need for accurate and robust flood risk assessment necessitates a thorough understanding of all flood characteristics, while ensuring that conclusions are drawn from multiple sets of flow data to ensure statistical validity [5]. Conventional analyses have historically focused on a single flood characteristic, typically peak flow. This approach, however, neglects the interconnected nature of other critical flood variables, specifically flood volume and duration. Previous studies have consistently demonstrated that these variables are frequently interdependent; for instance, peak flow and flood volume exhibit significant dependence structures [6,7,8]. Overlooking these crucial, multivariate relationships can lead to a substantial underestimation of flood hazard [6], particularly in environments that experience temporal shifts in their underlying statistical properties. Therefore, the prerequisite step of detecting and characterizing temporal changes across all relevant flood variables is vital for any subsequent statistical analysis [9]. The process of isolating extreme flood events is a crucial initial step in characterizing flood behavior and serves as a fundamental requirement before nonstationary detection. Event extraction methods, which directly influence the resulting time series, are typically categorized as the block maxima (BM) and peak-over-threshold (POT) approaches. Many studies recommended the joint use of BM and POT for comparison, as they offer complementary perspectives and often yield corresponding results [10,11]. While simple and widely applied [6,7], BM may overlook other extreme observations within the block. Moreover, it may underestimate design floods at higher return periods [12], leading to a growing preference for POT, which makes fuller use of available extreme events [11,13]. A key challenge in POT is threshold selection, as the choice strongly influences the statistical properties of the extracted series [14]. Studies have shown that in the application of POT in frequency analysis, as thresholds increase, uncertainty in scale and shape parameters rises, with particularly large uncertainty observed beyond the 98th percentile [14]. Percentile-based thresholds, as recommended by the WMO, are commonly adopted to balance data sufficiency and statistical stability [15]. The 95th percentile has been widely applied with promising results, including in the Mahanadi Basin [16] and in rainfall analyses with different percentile thresholds [17], where little difference was observed in design quantiles across thresholds of 95th–99.5th percentiles. Other studies have sought to justify thresholds based on average event frequency, suggesting values ranging from 1.68 peaks per year [18] to around 3–8 events per year [16,19,20].

Nonstationarity in hydrologic time series has been increasingly documented. Studies have shown that flows in rivers and streams are influenced by multiple nonstationary drivers, including climate variability, land-use and land-cover changes, urbanization, and the construction of flood control structures [6,8,21]. As early as 2001, nonstationary detection had already been employed in 39 Polish rivers [22], while more recent studies attributed such behavior to rapid urbanization and population growth [17] and reservoir operations [9]. These findings raise an important methodological question of whether marginal distributions of each flood variable in multivariate FFA should be modeled as stationary or nonstationary. Li et al. emphasized that even if variables such as peak flow and duration are independently and identically distributed, their marginals may remain stationary [21]. Incorrectly assuming nonstationarity, where it does not exist, or conversely assuming stationarity despite temporal changes, can bias model estimates and compromise flood risk management. Obeysekera and Salas [3] similarly argued that designing flood structures under stationary assumptions, even in a changing environment, is no longer appropriate. Reviews by Barbhuiya et al. further underline that nonstationary FFA is essential for addressing the combined impacts of climate change, land-use change, and human activity [23].

More recently, studies have begun integrating nonstationarity into the different flood variables in FFA [21,24]. Moreover, recent advancements in the field of nonstationary FFA introduces various explanatory variables to better understand flow dynamics [25]. With the advancements of technology, application of machine learning in hydrologic studies have also already been initially explored [26]. Among the machine learning algorithms utilized in FFA are support vector regression, multivariate adaptive regression spline, regression trees, projection pursuit regression and forest regression [27,28].

While nonstationarity in flood records has already been documented in the literature, much of this has focused primarily on peak flow, with comparatively less attention to other variables such as volume and duration [29]. Where multiple variables are considered, analyses typically assume stationarity or do not explicitly test for temporal shifts in their distributions. In addition, while both BM and POT are established approaches for event selection, their influence on the detection of nonstationarity across different flood variables have received limited attention. This lack of integrated assessment constraints understanding how methodological choices affect the robustness of nonstationary detection, particularly in urban catchments where hydrologic extremes are shaped by both climate variability and rapid land-use change.

Motivated by this gap, this study investigates nonstationarity in multiple flood variables within an urban catchment in the Philippines. This employs both statistical and computational approaches. Against this background of increasingly complex flood drivers and methodological uncertainty, this study develops a comprehensive computational framework for the detection of nonstationarity in peak flow, volume and duration in an urbanizing catchment in the Philippines. The specific objectives of this study are:

- To evaluate and select the optimal imputation method for reconstructing the missing daily flow records using physically relevant predictors;

- To apply a set of non-parametric tests to assess the temporal trends and change points in three critical flood variables (i.e., peak flow, volume and duration);

- To compare the sensitivity of nonstationarity detection using BM and POT which are two fundamentally different event extraction methods.

By combining advanced statistical tests with data-driven models in data imputation, the study provides a comprehensive framework for analyzing nonstationary flood variables. The findings aim to enhance the accuracy and reliability of flood risk assessments in rapidly urbanizing environments, contributing to improved design standards and adaptive management strategies.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area and Data Sources

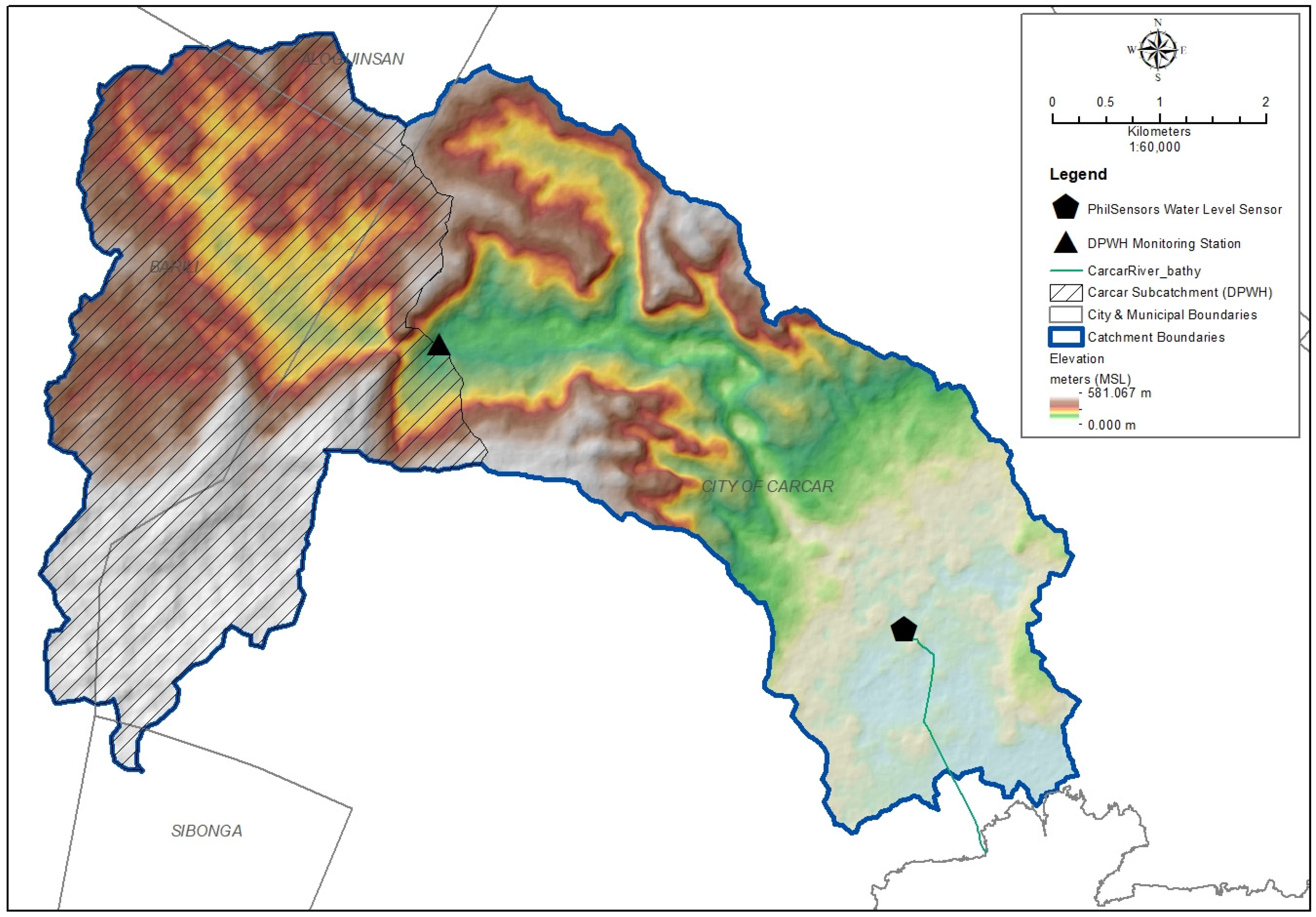

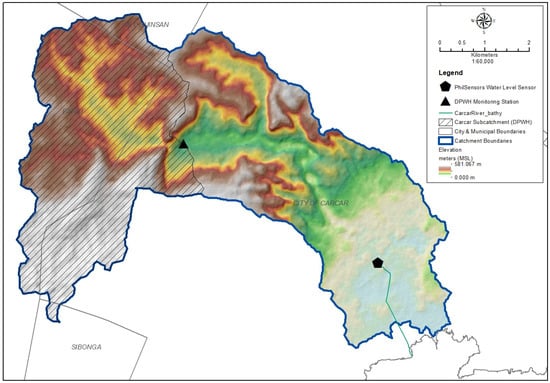

The Carcar River catchment was selected as the case study site for detecting nonstationarity in flow data. Located in Carcar City, the southernmost city of Metro Cebu, Philippines, the catchment covers a total drainage area of approximately 38.58 km2 and drains towards the Cebu Strait. Its physiography is characterized by mountainous and hilly headwaters that transition into a narrow floodplain dominated by urban land uses. In recent years, the urbanized floodplain has experienced more frequent flooding, making Carcar River a representative example of small urban catchments where hydrologic extremes are intensifying due to combined climate and land-use pressures.

In response to these conditions, national agencies have installed monitoring instruments within the catchment. The Department of Public Works and Highways (DPWH) has maintained a flow observation site at 10°7′46″ N and 123°36′10″ E, recording daily flow data from 1984 to 2022. The datasets can be accessed through the DPWH Streamflow Management System website [30]. A complementary depth monitoring instrument is also installed downstream at Carcar Bridge under the supervision of PhilSensors of the Department of Science and Technology - Advanced Science and Technology Institute, Quezon City, Philippines [31].

For this study, the DPWH dataset was utilized, given its long-term record, which spans nearly four decades. The dataset includes daily peak flow observations along with monthly flow summaries, providing the basis for reconstructing missing values, extracting flood events, and assessing nonstationarity across key flood variables. The catchment area with the location of monitoring sites is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Carcar River Catchment showing locations of monitoring stations: DWPH flow observation site and PhilSensors water level sensor at Carcar Bridge. The map also illustrates the catchment boundary and elevation gradients, highlighting the transition from mountainous headwaters to the urbanized floodplain.

2.2. Data Processing

Historical flow datasets frequently contain missing values due to sensor malfunction, gaps in observation, or interruptions in data recording. The time series flow data obtained from DPWH contained approximately 8.26% missing values due to gaps in observation. These gaps are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Data Gaps in the Flow Time Series Data of DPWH.

Traditional approaches for data imputation, such as deletion of incomplete entries or proxy substitution from nearby stations, may be suitable for short gaps (1–4 days) but become unreliable for extended periods of missing data (up to 382 days). More robust options for data imputation include mean substitution, interpolation, time series models, regression-based methods, and advanced techniques such as artificial neural networks (ANNs).

Although data imputation is often overlooked in hydrologic analysis, it plays a crucial role in ensuring the accuracy and reliability of subsequent computations. Wu et al. demonstrated that model performance improves significantly when missing values in long datasets are properly reconstructed [32]. However, it should be noted that reconstructed data introduces an additional source of error that may propagate and affect further FFA results. To minimize this methodological uncertainty, the imputation models were cross-validated against observed data using various training-test splits (TTS), and the model with the best performance was selected for the final imputation. This selection process ensures that the reconstructed series is based on the most statistically robust relationship available, thereby constraining the propagation of imputation error into the subsequent nonstationary detection step.

Given the extent of these missing records, multiple linear regression (MLR) and ANN imputation methods were evaluated. MLR remains a widely used technique because of its simplicity and interpretability. However, recent studies show that ANNs are increasingly adopted to address more complex, prolonged data gaps [33,34,35].

In this study, four predictors (daily rainfall, antecedent rainfall, antecedent flow, and built-up area index) were employed using both MLR and ANN models to impute missing flow values. The selection of the predictors used was based on established hydrological principles for modeling streamflow in urban catchments. The daily rainfall serves as the immediate driving force for the observed flow. Meanwhile, antecedent rainfall and antecedent flow represent the catchment initial saturation conditions. The built-up index is a non-meteorological variable that serves as proxy for land-use change and urbanization. Including this variable allows the imputation model to dynamically adjust the flow estimates based on monotonic changes in the catchment’s physical characteristics. Evapotranspiration and antecedent soil moisture were initially considered as additional predictors because they help represent catchment losses and antecedent wetness conditions, respectively. However, no continuous daily datasets for these variables exist for the entire study period. Due to this limitation, they were excluded from the final model. The built-up area index was therefore used to indirectly represent long-term changes affecting catchment losses, while antecedent rainfall and antecedent flow were retained to characterize short-term antecedent catchment conditions. The utilization of the four predictors in MLR and ANNs allowed the reconstruction of a more complete and consistent time series, thereby enabling more robust nonstationary analysis.

Daily rainfall data were obtained from the Philippine Atmospheric, Geophysical and Astronomical Services Administration (PAGASA). Built-up area indices were derived from Sentinel-2 satellite imagery (2016–2022) to quantify land use changes. Datasets (rainfall depth, flow, and built-up area index) from the years 2016 to 2022 have been extracted and have been subject to data imputation model generation.

Python-based algorithms were developed to train and evaluate both MLR- and ANN-based imputation models. The MLR algorithm utilizes the sklearn and pandas libraries. Consequently, the generated ANN algorithm utilizes the sklearn, pandas, and tensorflow libraries. The inclusion of ANNs, in particular, was motivated by their ability to capture nonlinear dependencies between hydrologic variables, which linear regression models may not adequately represent. A certain percentage of data has been used to train the model, and the remaining data has been used for validation.

Model performance was assessed using the Pearson correlation coefficient, root mean square error (RMSE), mean absolute error (MAE) and Nash-Sutcliffe Efficiency (NSE), providing a measure of agreement between imputed and observed values. The model with the best performance has been selected for data imputation.

2.3. Event Selection for Flow Variables

Accurate extraction of flood events from continuous flow records is essential for reliable FFA. In this study, two widely used approaches were applied, BM and POT. BM was used to construct the annual maximum flow series by selecting the largest flow event in each year of record, while POT identified all independent exceedances above a certain threshold. For the POT method, the 95th percentile was adopted as the threshold. While this choice is supported by existing literature for balancing statistical stability and event representativeness, a dedicated diagnostic assessment was also performed to evaluate threshold sensitivity.

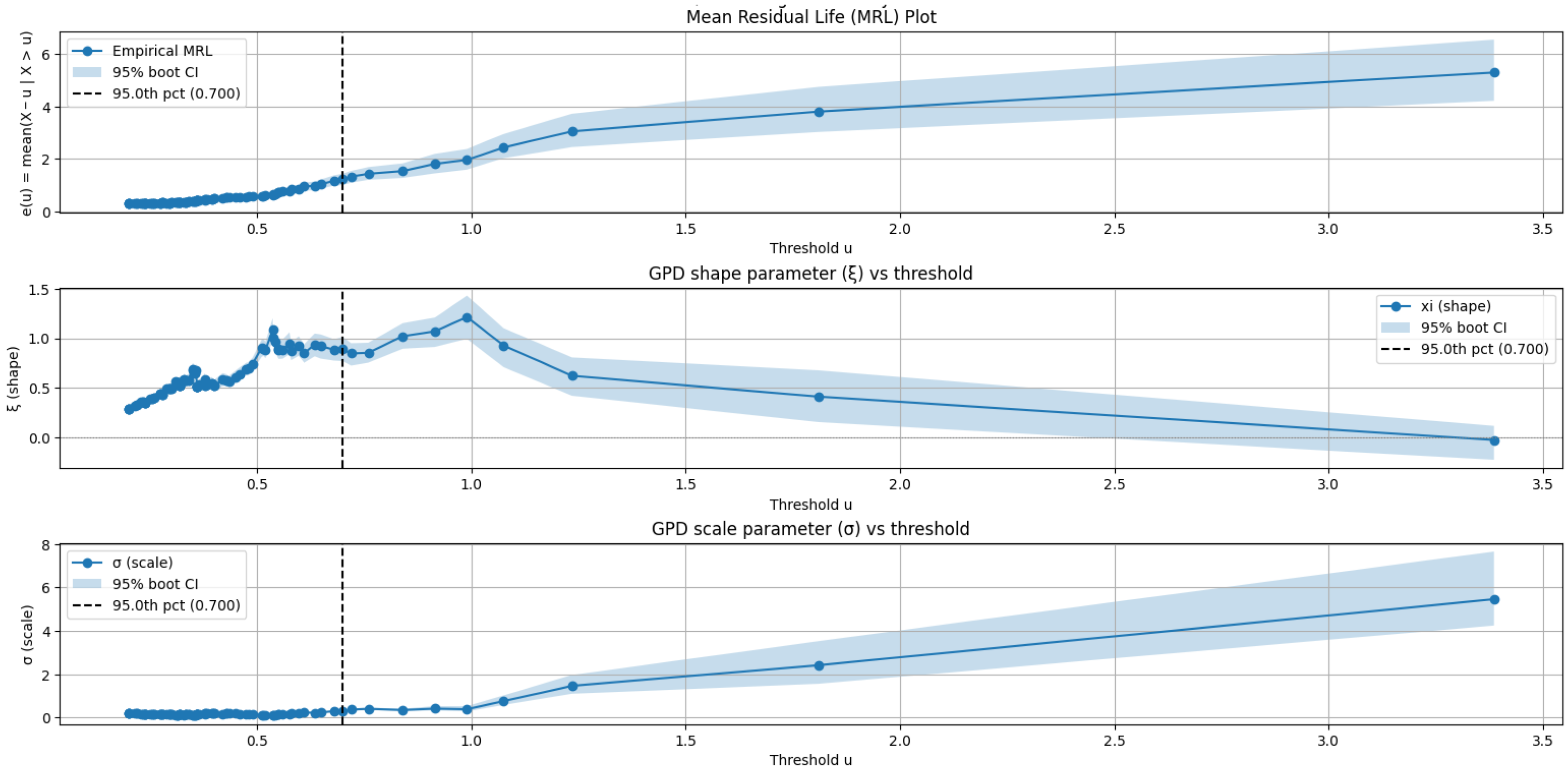

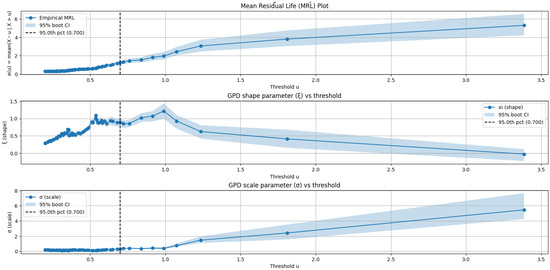

To ensure the selected threshold satisfies the assumptions of the Extreme Value Theorem and yields stable parameter estimation, a Generalized Pareto Distribution analysis was carried out. Specifically, the mean residual life (MRL) plots and parameter stability plots were examined. These diagnostics help determine the range of thresholds where the GPD model is appropriate or stable.

As shown in Figure 2, the MRL plot becomes approximately linear at threshold values between 0.60 and 0.70 , indicating suitability for GPD modeling in this region. The stability plots further reinforce this as the shape parameter stabilizes around the same range, while the scale parameter exhibits steady behavior without abrupt changes. In contrast, threshold above 1.0 lead to a steep increase in the scale parameter, suggesting insufficient exceedances and reduced statistical reliability. Based on these diagnostics, a threshold of approximately 0.70 , corresponding to the 95th percentile, represents the lowest value at which all diagnostic criteria are simultaneously satisfied.

Figure 2.

Mean Residual Life (MRL) plot and parameter stability plots for threshold selection. The MRL plot (top) illustrates the linearity region used to identify stable threshold candidates, while the shape (middle) and scale (bottom) parameter stability plots. The vertical dashed line marks the selected threshold value.

For each extracted event, three flood variables were quantified: peak flow, defined as the maximum discharge during the event; flood volume, calculated as the integral of flow values above the baseflow over the event duration; and duration, measured as the continuous period from event onset until flow recession. The baseflow for each event was determined using the straight-line method. To ensure the necessary statistical independence of the 282 exceedance events for POT, a hydrograph separation criterion was applied for declustering. An event was considered complete, and a new peak was allowed to be registered, only when the streamflow receded back to the predefined baseflow threshold. This physically based criterion provides established assessment of event independence, dynamically adapting to the varying recession characteristics of the catchment. Python-based algorithms, developed using pandas, numpy and scipy libraries, were employed to automate the event extraction and reduce subjectivity, complementing manual calculations in Microsoft Excel.

2.4. Nonstationarity Detection

Detecting nonstationarity requires assessing whether the statistical properties of flow variables change over time. This study employed a suite of statistical tests to capture both gradual and abrupt changes. The Mann–Kendall test [36,37] was used to detect monotonic trends, while the Sen’s slope estimator [38] quantified their magnitude and direction. To identify abrupt shifts in the time series, the Pettitt test [39] was applied, and changes in variability were assessed using the variance change test [40] and Levene’s test [41].

All procedures were implemented through Python-based algorithms, ensuring reproducibility and computational efficiency. The integration of these complementary methods provides a comprehensive framework for detecting both gradual trends and sudden regime shifts in the flow record.

3. Results

3.1. Performance of Data Imputation Models

Initial attempts to predict daily peak flow using daily rainfall alone proved inadequate. This is likely due to the complex relationship between rainfall and runoff, where factors such as impervious surfaces, drainage infrastructure, and antecedent conditions significantly influence peak flow response.

To improve model performance, antecedent rainfall, antecedent flow, and the built-up area index were considered. Comparison of utilizing three predictors (excluding antecedent rainfall) and all four predictors is presented in Table 2, along with the corresponding model performance metrics. To objectively assess the performance of the imputation models, R2, RMSE, MAE, and NSE were computed. In this table, MLR-3 and ANN-3 refer to models using 3 predictors, while MLR-4 and ANN-4 use 4 predictors. Moreover, various data TTS ratios were evaluated to identify the configuration yielding optimal predictive accuracy.

Table 2.

Comparison of Model Performance of MLR and ANN Models.

The results, summarized in Table 2, show that the MLR model consistently outperformed the ANN model, with very minimal differences in values of R2, RMSE and NSE. Conversely, ANN-3 with 85-15 TSS yields the lowest MAE among all models tested. For the final imputation of missing peak flow values across the dataset, the following MLR-4 with 95-5 TTS equation was used:

where is the daily peak flow, is daily rainfall, is the antecedent rainfall, is the antecedent peak flow, and is the built-up area index.

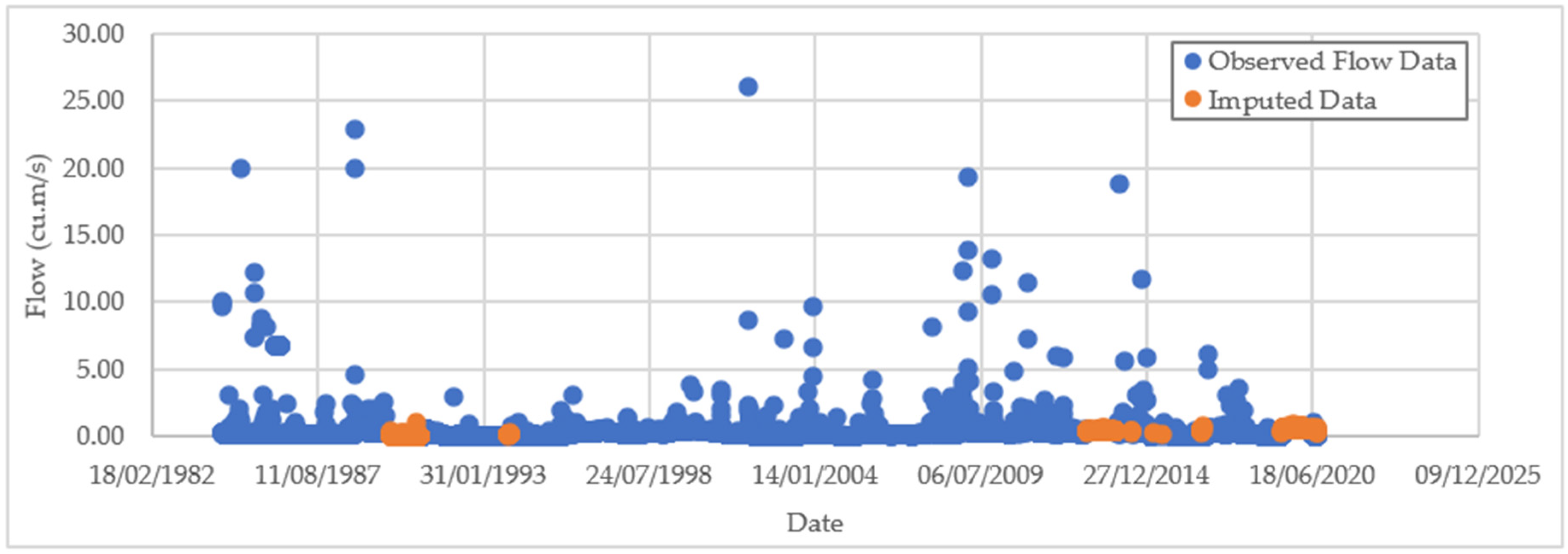

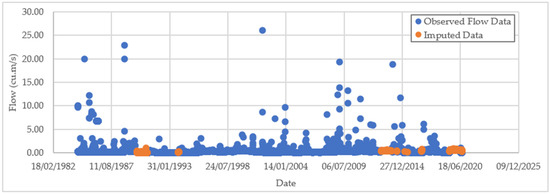

The complete daily flow time series, including imputed values, is presented in Figure 3, illustrating the effectiveness of the proposed model in reconstructing continuous hydrological records.

Figure 3.

Time series of daily peak flow showing observed values and imputed values generated using the four-predictor MLR model.

3.2. Event Extraction Using BM and POT Approaches

Flood variables were derived from the reconstructed series using both BM and POT approaches. Under the BM method, the annual maximum series was constructed by selecting the single largest peak flow event from each year, resulting in a dataset of 39 peak flow events corresponding to the length of the dataset. The associated volume and duration for each of these 39 annual maximum events were then computed.

Using POT with a 95th percentile threshold, a larger number of extreme events was captured. This approach allows multiple events per year to be included, providing more detailed information on how flow extremes beyond the annual maxima. The choice of threshold in the POT method strongly influences the number and magnitude of the events captured, highlighting the method’s sensitivity.

The BM and POT approaches generated differing event sets, which can affect the detection and characterization of nonstationarity in flood variables. A comparison of the statistical properties of the resulting peak flow, volume, and duration for both methods is presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Statistical properties of peak flow, volume, and duration using BM and POT methods.

3.3. Detection of Nonstationarity

Nonstationarity in the reconstructed flood series was evaluated using non-parametric trend and change point analyses. The results, summarized in Table 4, show the outcomes of the Mann–Kendall test, Sen’s slope, Pettitt test, and Levene test for peak flow, volume, and duration, using both BM and POT event extraction methods.

Table 4.

Non-parametric trend and change point analysis results.

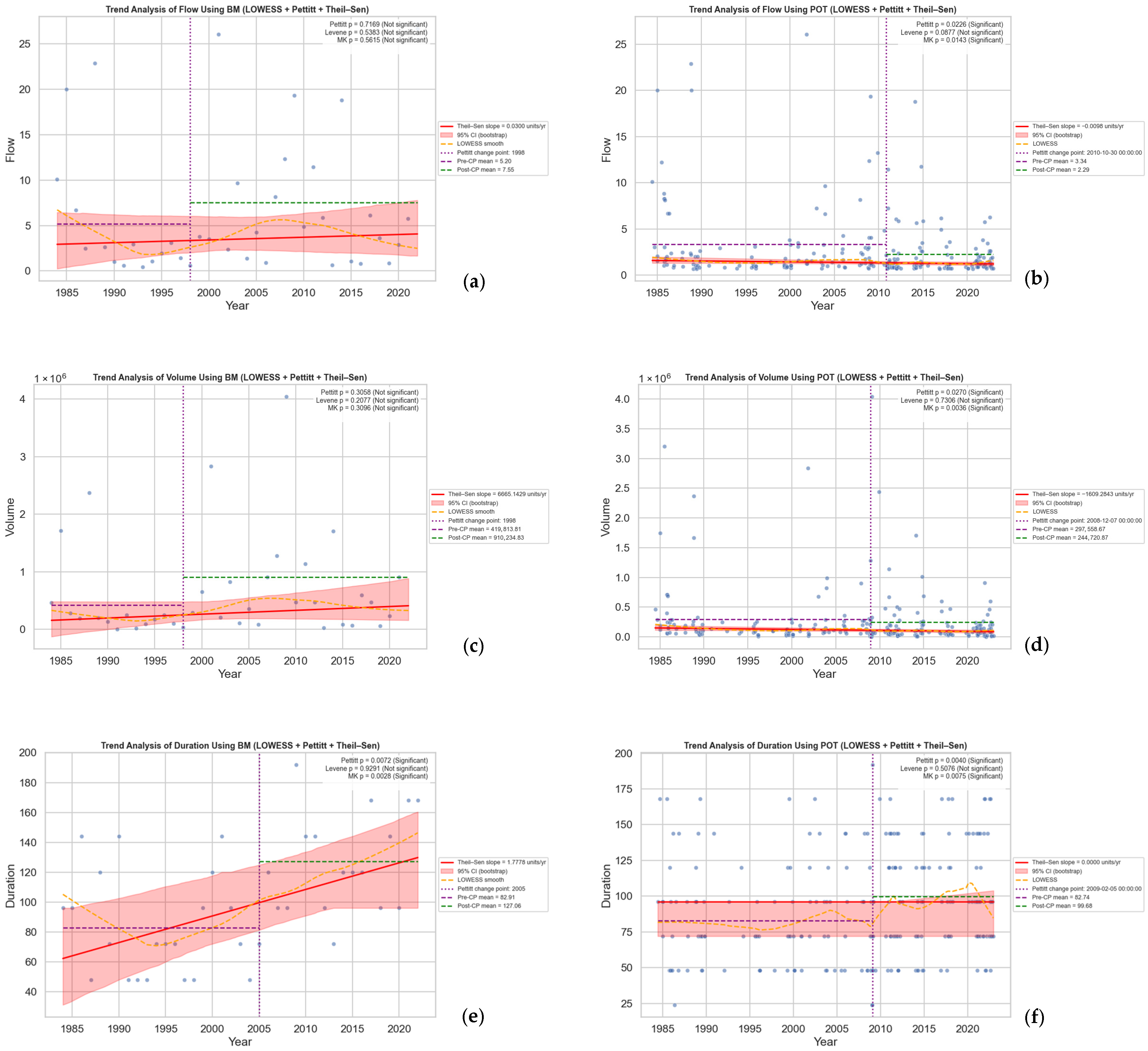

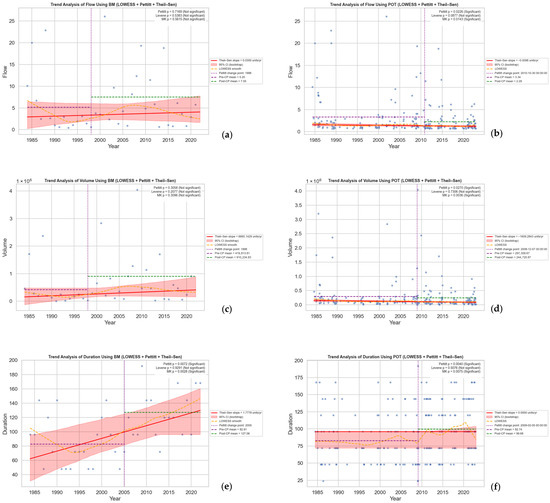

As evident in the values presented in Table 4, two event extraction methods yielded different results. Moreover, the results of trend analyses of peak flow, volume, and duration over the study period are presented in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Trend analyses of peak flow, flood volume, and event duration derived using the Block Maxima (BM; left column) and Peak-Over-Threshold (POT; right column) extraction methods. Panels (a,b) present the temporal trends of peak flow, (c,d) show the trends of flood volume, and (e,f) depict the trends of flood duration. Each panel includes the Theil–Sen slope estimate (solid line), bootstrap 95% confidence intervals (shaded band), and Mann–Kendall test results indicating the presence or absence of significant monotonic trends over the study period.

Analysis using the BM method indicated contrasting behavior among three flood variables. Peak flow and flood volume exhibited no significant monotonic trends, with Sen’s slope values close to zero and confidence intervals overlapping zero (e.g., peak flow Sen’s slope is 0.03, 95% confidence interval at −0.05 to 0.08 and p-value > 0.05). By contrast, flood duration showed a statistically significant increasing trend, averaging 1.78 h per year (95% confidence interval at 0.10 to 0.70 and p-value < 0.05). Pettitt’s test detected a change point around 1998 for both peak flow and volume and 2005 for duration, suggesting a shift in hydrologic behavior during this period. However, variance tests indicated no significant changes in variability across the BM-derived series.

The POT method provided a different perspective, capturing multiple significant events per year. Here, all three flood variables, peak flow, volume, and duration, exhibited statistically significant nonstationary behavior. For peak flow, the Mann–Kendall test detected a downward trend, with Sen’s slope of approximately 0.0016 (95% confidence interval at 0.12 to 0.40 and p-value < 0.05). Flood volume changed at a rate of (95% confidence interval at 0.05 to 0.55 and p-value < 0.05), while duration had a negligible rise (95% confidence interval at 0.15 to 0.75 and p-value < 0.05). Pettitt’s test identified change points in early 2000s across all three variables, aligning with periods of rapid urban development in Carcar City. Similarly to the BM results, the variance tests did not confirm significant shifts in variability.

4. Discussion

4.1. Event Selection and Method Sensitivity

The results of this study underscore the importance of methodological choices in detecting nonstationarity in hydrologic extremes, particularly in urban catchments exposed to land-use pressures. The analysis of imputation methods revealed that MLR with rainfall, antecedent rainfall, antecedent flow, and built-up area index as predictors provided the most reliable reconstruction of missing data. These findings highlight that even relatively simple statistical models can outperform more complex machine learning approaches, such as ANNs, when the relationships between predictors and flow are largely linear. The underperformance of the ANN model in this study is likely attributed to the linear relationship between peak flow and the key predictors, particularly the antecedent flow and daily rainfall. Since the MLR model’s of 0.5684 was superior to the ANN model performance of of 0.5675, the complex, non-linear mapping capabilities of the ANN model were not required and did not provide tangible benefit. Additionally, while the ANN algorithm utilizes libraries like tensorflow, implying the use of a neural network architecture capable of capturing non-linear dependencies, the relatively limited data volume may have been insufficient to fully train a complex network without leading to overfitting to the training data, especially in the configurations with smaller test splits. This suggests that the simplicity and robustness of the linear model are advantageous given the specific data characteristics and size. Similar observations were reported in studies wherein it was emphasized that careful selection of predictors may be more critical than model complexity in gap-filling time series [42,43]. In the context of nonstationarity detection, such methodological rigor in data imputation ensures that subsequent analyses are based on a consistent and trustworthy dataset.

Equally critical are the methodological decisions surrounding event selection. The comparison between BM and POT illustrates how different extraction approaches shape detection outcomes. BM, by focusing on the single largest event each year, provides a conservative and relatively stable representation of extremes but overlooks secondary events of hydrologic significance. POT, in contrast, captures multiple exceedances above the 95th percentile, offering richer information but also greater sensitivity to threshold choice. The adoption of the 95th percentile in this study reflects literature recommendations, balancing statistical stability and representativeness while avoiding the large uncertainties associated with thresholds exceeding the 98th percentile [10,13,14].

An additional challenge in tropical basins such as the Philippines lies in the strong seasonal influence of the El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO). During El Niño years, suppressed rainfall results in fewer or no events above the POT threshold, while La Niña years produce more frequent events. As a result, BM tends to mute these seasonal contrasts by selecting a single annual maximum, where POT amplifies them, making variance shifts and long-duration trends more apparent in La Niña-dominated years. This interplay between methodological choice and climatic forcing underscores the need for dual application: BM provides a conservative benchmark, while POT captures the broader distribution of flood extremes. Together, they offer a more comprehensive picture of nonstationary behavior in urbanized climate-sensitive catchments.

4.2. Trends and Effect Sizes in Flood Variables

Across the flow variables, Mann–Kendall results revealed significant trends in flood duration, while trends in peak flow and volume were less consistent between BM and POT. The Sen’s slope estimates quantify these effects, with duration showing the strongest changes, on the order of several hours per decade, indicating that events are persisting longer even if peak intensities remain stable. Although some trends in peak flows were small in magnitude and associated with wide confidence intervals, the consistent signal in duration aligns with broader findings on flood persistence under climate and land-use change [17,44]. Effect sizes, therefore, provide a critical distinction; even when p-values alone suggested weak or marginal trends, slope estimates revealed whether changes are practically meaningful for food risk assessment.

It is also important to note that the negative Sen’s slopes observed for POT-derived peak flow and volume do not necessarily indicate that hydrologic extremes in the catchment are diminishing. Under a fixed-threshold POT framework, an increase in the frequency of moderate threshold exceedances, particularly during the La Niña years, exerts downward influence on the central tendency of the exceedance series, even when the most severe events remain stable or are increasing. This statistical dilution effect is well documented in POT applications [10,14,17], where trend direction can be driven by changes in event frequency rather than changes in magnitude. In this study, the substantial rise in POT event counts during wetter years produces larger number of moderate floods, shifting the median downward and resulting in negative Sen’s slopes. However, the high maxima observed in recent years, the positive duration trends, and documented flooding in the catchment all suggest that flood severity is not declining. Thus, the negative slopes should be interpreted as reflecting shifts in the frequency distribution of exceedances rather than an actual reduction in extreme peak flows or volume. This interpretation aligns with recent severe flooding experienced in the catchment, particularly during the 2018 and 2022 events. It is important to note, however, that no formal archival records of flood incidences exist for the study area and only publicly accessible news reports were available.

Uncertainty analysis further contextualizes these findings. Confidence intervals for Sen’s slope were narrowest in POT-derived peak flows, suggesting robust detection of moderate upward shifts, whereas BM-derived results often included zero, reflecting the loss of information from reduced sample size. Variance change tests supported these findings, with several periods showing significant increases in variability, an indication that floods are not only changing in central tendency but also in dispersion. This elevated variability poses challenges for infrastructure designed under fixed assumptions of flood behavior.

4.3. Abrupt Shifts and Nonstationary Drivers

The Pettitt test identified several significant change points, with major shifts aligning with periods of rapid urbanization. This temporal correspondence supports earlier findings by Villarini et al., who linked nonstationary behavior to land-use intensification [17]. In Carcar, abrupt shifts in duration suggest a compounded influence of both anthropogenic alterations and climatic variability. Importantly, these structural shifts emphasize that nonstationarity cannot be treated as a gradual phenomenon alone; sudden changes in watershed conditions can redefine baseline flood regimes within short periods.

While the detected change points correspond with known periods of land-use change in the catchment, the potential influence of gauge-related factors must be acknowledged. The DPWH flow record includes several extended data gaps due to sensor malfunction (Table 1). However, it has been confirmed that the detected change points do not coincide with the major data gaps or known periods of gauge malfunction. The absence of complete documentation on gauge maintenance or recalibration means that some of the identified shifts may partially reflect changes in instrumentation or data continuity. This, while the detected change points are hydrologically plausible, they should be interpreted with caution given these data limitations.

4.4. Impact of Event Selection Method on Trend Analysis and Nonstationarity

The comparison of event extraction methods further emphasized the sensitivity of nonstationarity detection to data processing choices. Using BM, only flood duration exhibited significant nonstationary behavior, consistent with reports that flood persistence may be more susceptible to climatic and land-use drivers [6,45]. In contrast, POT-based analyses suggested nonstationarity across all three flow variables, confirming the view that POT provides richer information on extremes but is highly sensitive to threshold definition [46,47]. These results indicate that adopting multiple event extraction methods is beneficial for reducing methodological bias and ensuring robustness of hydrologic inference. Additionally, these discrepancies in the result may also be affected by the sample size, threshold selection and the effects of ENSO.

In terms of sample size and statistical power, BM method extracts only a fixed, small sample of 39 annual events, severely limiting the statistical capability of the Mann–Kendall test and resulting in wide confidence intervals for peak flow and volume trend estimates that often overlap zero. In contrast, the POT method, utilizing the justified 95th percentile threshold, extracts 282 statistically independent exceedances, increasing the sample size approximately sevenfold. This enhanced data density greatly improves the statistical power and sensitivity to trends, allowing POT to reveal significant nonstationarity across peak flow, volume and duration, where BM largely failed. These differences are compounded by the methodological characteristics and their representation of hydrologic extremes.

Furthermore, the strong influence of ENSO in this tropical catchment contributes to the asymmetry where La Niña years contribute more frequent exceedances, while BM mutes this ENSO-driven event frequency variability into a single annual maximum, POT amplifies it, thereby strengthening the apparent trend magnitude. Finally, while the threshold sensitivity in POT requires careful justification, the ability of the chosen 95th percentile to retain sufficient exceedances allows it to detect gradual nonstationary behavior that the data-spares, low-power BM method inherently misses.

To provide supporting evidence of the potential influence of ENSO on POT-derived trends, a comparison of the number of POT exceedances during the years classified by PAGASA as El Niño and La Niña was performed. It is important to note that this comparison is exploratory analysis which intends to highlight potential associations and is not a formal attribution of the observed ENSO trends. The results show a clear contrast with El Niño years recording very few exceedances (mean of 1.3 events per year across 1997, 1998, 2015 and 2016), with 1998 and 2015 each showing only 0–1 event. In contrast, La Niña years produced markedly higher frequencies, with a mean of 14.3 events per year, including high counts in 2008 (13 events), 2011 (17 events), 2021 (21 events), and 2022 (18 events). This pattern indicates that wetter La Niña conditions generate substantially more threshold exceedances, amplifying interannual variability captured by POT but muted in BM, which selects only one event per year. While this analysis is exploratory and not intended as full attribution, it provides quantitative support that ENSO-related variability influences POT sample density and contributes to the stronger trend signals observed in POT-based nonstationarity detection.

4.5. Limitations of the Study

A critical consideration in utilizing reconstructed hydrologic time series is the propagation of uncertainty from the imputation process into subsequent nonstationarity tests. While the complexity of quantifying the exact uncertainty bounds for non-parametric tests like Mann–Kendall and Pettitt on gap-filled data is substantial, our methodological framework was specifically designed to mitigate this risk. First, the selection of the MLR model over the ANN model was based on a comparative performance assessment, prioritizing the model with the highest predictive accuracy to ensure the imputed values were as reliable as possible. Second, the predictors chosen, including antecedent rainfall, antecedent flow, and the built-up area index, accounted for the complex, time-dependent, and nonstationary drivers of the flow regime. This physically informed imputation reduces the likelihood of spurious trends being introduced. Finally, the use of complementary non-parametric tests (Mann–Kendall, Pettitt and Levene) and two different event extraction methods (BM and POT) provides a cross-validation of the results. The consistent finding of nonstationarity in duration across both BM and POT methods, despite their different sample sizes, suggests that the detected trends are robust and not merely artifacts of the data imputation process.

Furthermore, the built-up area index was generated using Sentinel-2 satellite imagery. However, since satellite coverage for the study area is only available starting in 2016, the built-up index for the period 1984–2015 was extrapolated. The extrapolation utilized observed urbanization trends, particularly population growth and road network expansion, which are highly correlated with built-up area expansion (Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.97 for population and 0.94 for road length). The predictive power of these covariates was confirmed by a developed Artificial Neural Network (ANN) model, which achieved a high coefficient of determination ( and Nash-Sutcliffe Efficiency ( in relating built-up area to population and road network length. The ANN model is presented as

where is a function of the input variables defined by:

In the ANN model, is the population and is the road network length. This approximation provides a reasonable representation of long-term land-use change, although it introduces inherent uncertainty due to the assumed continuity of urban growth patterns.

4.6. Implications for Practice

This study highlights key implications for urban flood risk management and hydrologic design. The detected increase in flood duration indicates that persistence, not only peak flows, must be considered in infrastructure planning. Divergences between BM- and POT-based estimates highlight the need for design standards that consider uncertainties in frequency analysis. The role of built-up area expansion in flood flow hydrograph generation further emphasizes the importance of integrating land-use planning with hydrologic assessments. Embedding nonstationary analysis into conventional practice will support the development of infrastructure and management strategies that remain resilient under climatic variability and rapid urbanization.

5. Conclusions

This study developed a comprehensive framework for detecting nonstationarity in multiple flood variables within an urban catchment in the Philippines. By integrating statistical methods (Mann–Kendall, Sen’s slope, Pettitt test, and variance tests) with data imputation techniques (Multiple Linear Regression and Artificial Neural Networks), the analysis addressed both data completeness and methodological sensitivity in evaluating hydrologic extremes. A notable finding was that MLR, using rainfall, antecedent rainfall, antecedent flow, and built-up area index as predictors, produced more reliable imputations compared with the ANN model. This highlights that predictor selection can be more critical than model complexity when reconstructing long-term hydrologic datasets.

The comparison of event extraction methods underscored how methodological choices shape nonstationarity detection. The Block Maxima approach offered conservative estimates of annual extremes, while the Peak-Over-Threshold method, using the 95th percentile, captured greater variability and was more sensitive to seasonal and interannual shifts, particularly under El Niño and La Niña conditions. The dual application of BM and POT illustrates the value of combining approaches. BM ensures robustness in long-term estimates, while POT captures short-term variability that is vital in urban flood risk assessment.

The novelty of this study lies in its integrated treatment of data imputation, event selection and nonstationarity testing within the context of a Philippine urban catchment, an approach rarely applied in local hydrologic studies. Practically, these findings stress the need to incorporate nonstationary frameworks into Philippine flood design standards, which are commonly based on stationary assumptions. Accounting for trends and shifts in flood peak, volume, and duration jointly under the framework of nonstationary flood frequency analysis provides a more realistic and robust estimate flood design parameter of flood protection systems.

Future research should extend this framework to other Philippine basins, integrate nonstationary flood frequency results with hydraulic and inundation modeling, and explore multivariate approaches to capture the joint behavior of flood variables. This study will not only advance scientific understanding but also provide a fundamental basis for climate-resilient planning and infrastructure design in rapidly urbanizing areas.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.F.O., E.H. and G.T.III; methodology, A.F.O.; software, A.F.O.; validation, A.F.O.; formal analysis, A.F.O., E.H. and G.T.III; investigation, A.F.O., E.H. and G.T.III; resources, A.F.O., E.H. and G.T.III; data curation, A.F.O.; writing—original draft preparation, A.F.O.; writing—review and editing, A.F.O., E.H. and G.T.III; visualization, A.F.O., E.H. and G.T.III; supervision, E.H. and G.T.III; project administration, A.F.O., E.H. and G.T.III; funding acquisition, A.F.O., E.H. and G.T.III. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Department of Science and Technology—Science Education Institute and Engineering Research and Development for Technology.

Data Availability Statement

The streamflow data used in this study were obtained from the public hydrological database of the Department of Public Works and Highways (DPWH), Philippines, specifically for the Carcar River gauging station. Rainfall data were provided by the Philippine Atmospheric, Geophysical and Astronomical Services Administration (PAGASA), with rainfall records from the Mactan station utilized in the analysis. The datasets are publicly accessible from the respective agencies. Processed data supporting the findings of this study are available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The rainfall data used in this study was acquired from the Philippine Atmospheric, Geophysical and Astronomical Services Administration.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Li, J.; Bortolot, Z.J. Quantifying the impacts of land cover change on catchment-scale urban flooding by classifying aerial images. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 344, 130992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, V.; Nikam, B.R.; Thakur, P.K.; Aggarwal, S.P.; Gupta, P.K.; Srivastav, S.K. Human-induced land use land cover change and its impact on hydrology. HydroResearch 2019, 1, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obeysekera, J.; Salas, J.D. Quantifying the uncertainty of design floods under nonstationary conditions. J. Hydrol. Eng. 2014, 19, 1438–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nathan, R. Improving event-based methods for modelling flood risk in a variable and non-stationary climate. Philos. Trans. A 2025, 383, 20240292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cunnane, C. Factors affecting choice of distribution for flood series. Hydrol. Sci. J. 1985, 30, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, N.; Agilan, V.; Jayakumar, K. Bivariate flood frequency analysis of nonstationary flood characteristics. J. Hydrol. Eng. 2019, 24, 04019007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sraj, M.; Bezak, N.; Brilly, M. Bivariate flood frequency analysis using the copula function: A case study of the Litija station on the Sava River. Hydrol. Process. 2015, 29, 225–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Singh, V. Bivariate flood frequency analysis using the copula method. J. Hydrol. Eng. 2006, 11, 150–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.; Xiong, L.; Xu, C.-Y.; Guo, S. Bivariate frequency analysis of nonstationary low-flow series based on the time-varying copula. Hydrol. Process. 2015, 29, 1521–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, M.; Ouarda, T.B.; Bobée, B. Towards operational guidelines for over-threshold modeling. J. Hydrol. 1999, 225, 103–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langbein, W.B. Annual floods and the partial-duration flood series. Eos Trans. Am. Geophys. Union 1949, 30, 879–881. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, M.; Sharif, M.; Ahmed, S. Flood estimation at Hathnikund Barrage, river Yamuna, India using the peak-over-threshold method. ISH J. Hydraul. Eng. 2020, 26, 291–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezak, N.; Brilly, M.; Šraj, M. Comparison between the peaks-over-threshold method and the annual maximum method for flood frequency analysis. Hydrol. Sci. J. 2014, 59, 959–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, Z.; Xiong, L.; Zha, X.; Liu, C.; Chen, J.; Liu, D. Impact of thresholds on nonstationary frequency analyses of peak over threshold extreme rainfall series in Pearl River Basin, China. Atmos. Res. 2022, 276, 106269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Data, C. Guidelines on analysis of extremes in a changing climate in support of informed decisions for adaptation. World Meteorol. Organ. 2009, 1500, 72. [Google Scholar]

- Guru, N.; Jha, R. Flood frequency analysis for Tel sub-basin of Mahanadi River, India using weibull, Gringorten and L-moments formula. Int. J. Innov. Res. Creat. Technol. 2015, 1, 220–223. [Google Scholar]

- Villarini, G.; Smith, J.A.; Ntelekos, A.A.; Schwarz, U. Annual maximum and peaks-over-threshold analyses of daily rainfall accumulations for Austria. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2011, 116, D05103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunnane, C. A particular comparison of annual maxima and partial duration series methods of flood frequency prediction. J. Hydrol. 1973, 18, 257–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.; Rahman, A.; Haddad, K.; Ouarda, T.B.; Sharma, A. Regional flood frequency analysis based on peaks-over-threshold approach: A case study for South-Eastern Australia. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2023, 47, 101407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beguería, S. Uncertainties in partial duration series modelling of extremes related to the choice of the threshold value. J. Hydrol. 2005, 303, 215–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Xiong, L.; Zhou, Y.; Yin, J. Nonstationary Seasonal Design Flood Estimation: Exploring Mixed Copulas for the Nonmonotonic Dependence Between Peak Discharge and Timing. J. Hydrol. Eng. 2024, 29, 04023046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strupczewski, W.G.; Singh, V.P.; Mitosek, H.T. Non-stationary approach to at-site flood frequency modelling. III. Flood analysis of Polish rivers. J. Hydrol. 2001, 248, 152–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbhuiya, S.; Ramadas, M.; Biswal, S.S. Nonstationary flood frequency analysis: Review of methods and models. In River, Sediment and Hydrological Extremes: Causes, Impacts and Management; Springer: Singapore, 2023; pp. 271–288. [Google Scholar]

- Latif, S.; Mustafa, F. Bivariate joint distribution analysis of the flood characteristics under semiparametric copula distribution framework for the Kelantan River basin in Malaysia. J. Ocean Eng. Sci. 2021, 6, 128–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yılmaz, M.; Tosunoğlu, F. Non-stationary low flow frequency analysis under climate change. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2024, 155, 7479–7497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anaraki, M.V.; Farzin, S.; Mousavi, S.F.; Karami, H. Uncertainty analysis of climate change impacts on flood frequency by using hybrid machine learning methods. Water Resour. Manag. 2021, 35, 199–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allahbakhshian-Farsani, P.; Vafakhah, M.; Khosravi-Farsani, H.; Hertig, E. Regional flood frequency analysis through some machine learning models in semi-arid regions. Water Resour. Manag. 2020, 34, 2887–2909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, S.; Ouarda, T.B. Regional hydrological frequency analysis at ungauged sites with random forest regression. J. Hydrol. 2021, 594, 125861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Huang, J.; Wagner, P.D.; Fohrer, N. A method for detecting the non-stationarity during high flows under global change. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 851, 158341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Department of Public Works and Highways (DPWH), Philippines. Streams Public—Home Page. Available online: https://apps.dpwh.gov.ph/streams_public/home.aspx (accessed on 22 November 2025).

- Department of Science and Technology–Advanced Science and Technology Institute (DOST-ASTI), PhilSensors Philippines—Home Page. Available online: https://philsensors.asti.dost.gov.ph/ (accessed on 22 November 2025).

- Wu, C.L.; Chau, K.W. Rainfall–runoff modeling using artificial neural network coupled with singular spectrum analysis. J. Hydrol. 2011, 399, 394–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Müller, J.; Arora, B.; Faybishenko, B.; Pastorello, G.; Varadharajan, C.; Sahu, R.; Agarwal, D. Long-term missing value imputation for time series data using deep neural networks. Neural Comput. Appl. 2023, 35, 9071–9091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cini, A.; Marisca, I.; Alippi, C. Filling the gaps: Multivariate time series imputation by graph neural networks. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2108.00298. [Google Scholar]

- Bülte, C.; Kleinebrahm, M.; Yilmaz, H.Ü.; Gómez-Romero, J. Multivariate time series imputation for energy data using neural networks. Energy AI 2023, 13, 100239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, H.B. Nonparametric tests against trend. Econometrica 1945, 13, 245–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendall, M.G. Rank Correlation Methods, 4th ed.; Charles Griffin: London, UK, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, P.K. Estimates of the regression coefficient based on Kendall’s tau. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1968, 63, 1379–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettitt, A.N. A non-parametric approach to the change-point problem. Appl. Stat. 1979, 28, 126–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Neumann, J. Distribution of the ratio of the mean square successive difference to the variance. Ann. Math. Stat. 1941, 12, 367–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levene, H. Robust tests for equality of variances. In Contributions to Probability and Statistics: Essays in Honor of Harold Hotelling; Olkin, I., Ed.; Stanford University Press: Redwood City, CA, USA, 1960; pp. 278–292. [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro, S.M.; de Castro, C.L. Missing data in time series: A review of imputation methods and case study. Learn. Nonlinear Model. 2021, 19, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, R.; Hamshaw, S.D.; Yang, L.; Kincaid, D.W.; Etheridge, R.; Ghasemkhani, A. Data Imputation for Multivariate Time Series Sensor Data with Large Gaps of Missing Data. IEEE Sens. J. 2022, 22, 10671–10683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razmkhah, H.; Ravari, A.; Fararouie, A. Multivariate flood frequency analysis using bivariate copula functions. Water Resour. Manag. 2022, 36, 729–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.W.; Zhang, T.; Wang, Y.; Wang, B.; Tan, S.; Feng, P. Nonstationary flood frequency analysis using univariate and bivariate time-varying models based on GAMLSS. Water 2018, 10, 819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, A.; De Haan, L. On the block maxima method in extreme value theory: PWM estimators. Ann. Stat. 2015, 43, 276–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidson, R.; Richards, K. Flood frequency analysis: Assumptions and alternatives. Prog. Phys. Geogr. 2005, 29, 392–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.