Abstract

The recently introduced solid-state modulator (SSM) is a compact and relatively simple all-in-one solution to thermal modulation for use in comprehensive two-dimensional gas chromatography (GC×GC). In this work, we assess the performance of this modulator through a detailed assessment of its temperature stability and temperature programming capabilities, and corresponding retention time reproducibility. Through replicate analysis, 2D retention time standard deviation was determined to be 0.014 s (ranging from 0.000–0.023 s), corresponding to less than a single acquisition datapoint. Additionally, 1D retention time repeatability in GC×GC was assessed using a ‘super-resolution method’ designed to predict 1D retention based on the modulated peak distribution, and was determined to be comparable to that of conventional GC-MS analysis. A benchmarking framework was developed, which can be applied to future performance evaluations of thermal and other modulators, allowing for a more systematic comparison of modulation strategies.

1. Introduction

Since its invention in 1991 [1], comprehensive two-dimensional gas chromatography (GC×GC), which allows for separation using serially-connected columns having two different separation mechanisms that should normally exhibit some measure of ‘orthogonality’, has become a highly informative tool in the analysis of complex samples of volatile organic compounds (VOC). GC×GC delivers unmatched overall sample selectivity, sensitivity and peak capacity for volatile compounds [2]. Wong et al. [3] profiled a number of eucalyptus species and reported a much greater identified metabolite coverage percentage, by virtue of the improved compound resolution and resulting better mass spectrometry quality matching. This in turn leads to overall improved sample characterisation by virtue of separation multidimensionality [3]. In addition to data analysis of complex multi-component samples [4], an often-cited barrier to entry into the world of GC×GC is the cost and complexity of the modulator, necessary in adapting a GC instrument to GC×GC capability [5], especially if one wishes to reap the sensitivity gains afforded by a thermal modulator [6]. The thermal independent modulator (TiM), also referred to as the solid-state modulator (SSM), was reported by Luong et al. in 2016 [7] and commercialised by J&X Technologies (Nanjing, China). The SSM is a compact, all-in-one module which sits atop the GC oven, therefore not increasing the footprint of the GC system, allowing thermally independent operation. The operation is similar to one of the modes of the longitudinally modulated cryogenic system (LMCS), which operates via mechanically moving a cooled trap in order to trap analytes [8]; another mode of the LMCS, employed by the SSM, operates via mechanically moving a modulator column, which here is located between a cold trapping zone and heated entry and exit zones located on either side of the cold region [9]. Cooling is performed using a solid-state Peltier cooling element, removing the need for chemical cryogens or an external chiller unit, with trapping operation at as low as −50 °C possible.

Since its development, the SSM has been used for targeted and non-targeted analysis of diverse compounds and sample types, including food, environmental and petrochemical [3,10,11,12,13,14]. Performance comparable to cryogenic and cryogen-free thermal modulators has been demonstrated, with trapping and modulation down to C5 possible using a stock modulation column [15], or C2 using a three-piece, but commercially available solution [14].

In this work, the performance of this modulator operation will be critically assessed in the context of thermal modulator operation. Its trapping, temperature control and corresponding impact on 1D and 2D retention time will be investigated in detail, using a benchmarking framework developed for this study and applicable to thermal and other modulators. In addition, the reproducibility of the prediction of the 1D retention time based on the pattern of modulated peaks is presented as a robust measure of accurate 1tR data.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Chemicals

A standard solution of 15 essential oil compounds was prepared in hexane as detailed in Table S1 in the Supplementary Materials. Eucalyptus oil was sourced from FGB Natural Products (Oakleigh South, Australia) and used according to the reasons expressed by Wong et al. [3].

2.2. Instrumentation

Analyses were carried out using an Agilent 7890A gas chromatograph coupled to a 5975C mass spectrometer (Agilent Technologies Australia Pty. Ltd., Mulgrave, Australia). The instrument was adapted for comprehensive two-dimensional separation using a J&X SSM1820 solid-state modulator (J&X Technologies, Nanjing, China). Separation was carried out using a DB-5ms column in the first dimension (1D, Agilent Technologies) (30 m, 0.25 mm i.d., 0.25 μm film thickness), and a DB-WAX column (1.0 m, 0.10 mm i.d., 0.1 μm film thickness) in the second dimension (2D, Agilent Technologies). Columns were coupled using PressFit connectors (RESTEK, Bellefonte, PA, USA).

Prepared samples and standards of 0.5 μL were injected neat using a 50:1 split ratio at an inlet temperature of 250 °C. Helium (99.999 purity) was used as the carrier gas with a constant flow rate of 1.0 mL/min. For isothermal analysis, the oven temperature, SSM entry and exit temperatures were 120 °C for 50 min, with the trap temperature set to −50 °C. For temperature programmed analysis, the oven temperature followed the program: initially 50 °C for 3 min, ramped to 200 °C at a rate of 3 °C/min, then to 240 °C at a rate of 10 °C/min, with a final hold of eight min, giving a total analysis time of 65 min. The SSM entry and exit temperatures were operated using the same temperature program as the GC oven, while the trap temperature was set to −50 °C for 8 min initially, increased to −20 °C at a rate of 2 °C/min and held for the remaining 37 min. The modulation period was set to 6000 ms, with a desorption time of 1000 ms. The MS was operated in SCAN mode, scanning between 35 and 350 m/z, yielding an acquisition rate of ~23 Hz. For 1D analysis, the 2D column and modulator were bypassed, with the column (the same as that used as the 1D column in GC×GC analysis) directly connected to the MS.

2.3. Data Analysis

1D chromatograms were analysed by using Agilent MassHunter Qualitative Analysis (Agilent Technologies, version 10.0), and GC×GC chromatograms in GC-Image (GC Image LLC., Lincoln, NE, USA. LLC., version: 2.9R1.1). Gaussian distributions were fitted to 1D retention profiles and their apex determined using fit and gaussmaxima functions in Matlab (Version R2023B, Mathworks, Natick, MA, USA).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Benchmarking Framework

To assess the performance of the thermal modulator, first, replicate analyses were performed in 1DGC-MS to assess instrument-related retention time variability. Following this GC×GC analysis was performed with isothermal heated and cooled zones, to determine temperature stability of the zones and corresponding 1D and 2D retention time reproducibility. Following this, the temperature programming performance of the heated zones was assessed through trialing multiple ramp rates, again assessing temperature stability of the zones and corresponding retention time reproducibility.

3.2. 1D Retention Time Reproducibility

Instrument-related retention time reproducibility was first assessed using isothermal 1DGC-MS using multiple injections (n = 13) of the standard mix, which yielded minimum, maximum and average retention time standard deviations of 0.04, 0.62 and 0.17 s, respectively; these data are summarised in Table S2 of the Supplementary Materials.

Switching to isothermal GC×GC analysis, 1D retention time standard deviation for 13 of the 15 target analytes as measured for the largest modulated peak was observed to be 0.00 s (see below), and for two of the later eluting analytes, geranyl acetate and caryophyllene, the phase of modulation was such that the 1D maxima varied between two of the largest 1D data points (i.e., tallest modulated peaks), yielding a standard deviation of 3.16 s. 1D retention times of analytes in GC×GC are most often annotated as being assigned to the tallest modulated peak of each analyte. However, this has been demonstrated to be erroneous and is exacerbated for 1D peaks that happen to exhibit close to out-of-phase modulation (i.e., where two major modulated peaks are found) as this may either mask or exaggerate minor retention time shifts in 1D, depending on the phase of modulation [16]. One solution, reported by Adcock et al. in 2009, is to fit a Gaussian distribution to the 1D elution profile (i.e., the set of modulated peaks for a given analyte—sometimes referred to as peaklets) and assign the apex of this distribution as the 1D retention time, taking into account the peak hold-up in the modulator [17]. Combined with the specificity of MS for compound identification, this was the basis for referring to GC×GC as a ‘super-resolution’ experiment, acknowledging the very high resolution that GC×GC brings to VOC analysis supported by MS selectivity [16]. This approach was first validated in this experiment by varying both the modulator start time, in order to shift the phase of modulation, and the modulation period. This ensured the prediction of 1D retention time was repeatable, as summarised in Table S3 of the Supplementary Materials.

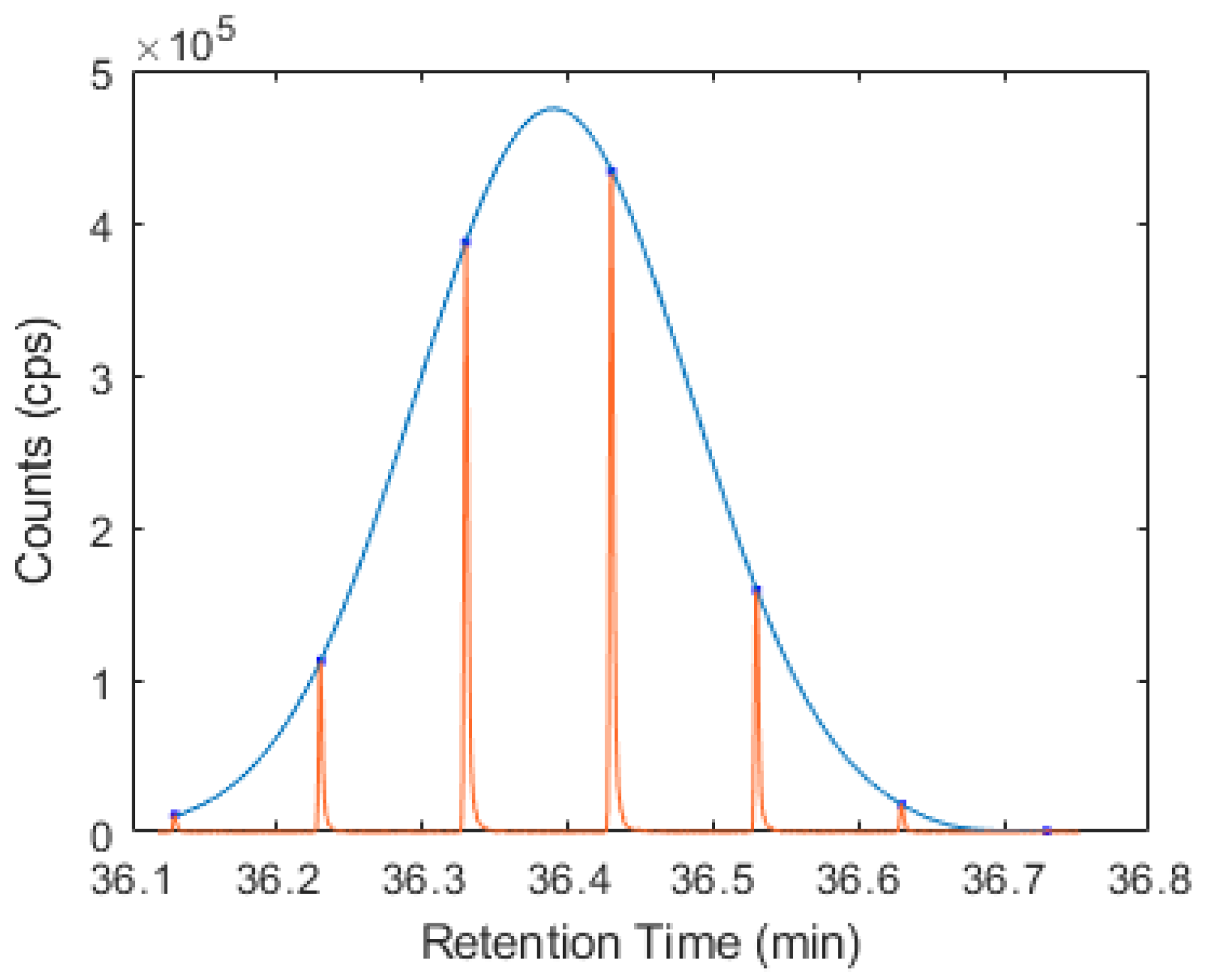

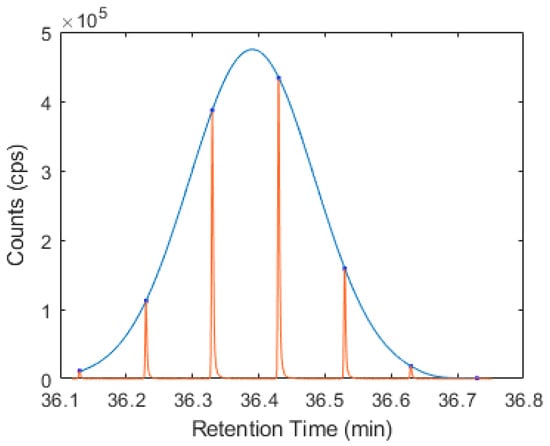

Following validation, this approach was used to model the 1D retention time of geranyl acetate and caryophyllene, yielding retention time standard deviations more comparable to that observed in a 1DGC-MS experiment, of 0.80 and 0.63 s, respectively. An example of a fitted Gaussian distribution to a 1D elution profile of caryophyllene is shown in Figure 1 below, created using Matlab. This is close to 180° out-of-phase modulation, which would have two equal response ‘peaklets’. Small shifts in 1D retention (1tR) could result in either of these two large peaks being attributed as the 1tR value, clearly an incorrect case. A summary of the 1D retention time data is provided in Table S4 of the Supplementary Materials, in addition to the Matlab script used to generate the distribution and corresponding plot.

Figure 1.

1D elution profile of caryophyllene (red line) with overlay of the fitted Gaussian distribution (blue line).

3.3. 2D Retention Time Reproducibility

Minimum, maximum and average 2D retention time standard deviations for the target analytes were 0.000, 0.023 and 0.014 s, respectively, corresponding to less than a single scan point from the detector (~0.044 s). Corresponding to a minimum, maximum and mean relative standard deviation of 0.000, 0.068 and 0.015%, the variation observed here is slightly greater than the maximum deviation of 0.008% observed by Luong et al. 2016 [7]. The deviation observed by Luong et al. (2016) [7] may be more accurately defined by the greater acquisition rate of 200 Hz. Data are summarised in Table S5 of the Supplementary Materials.

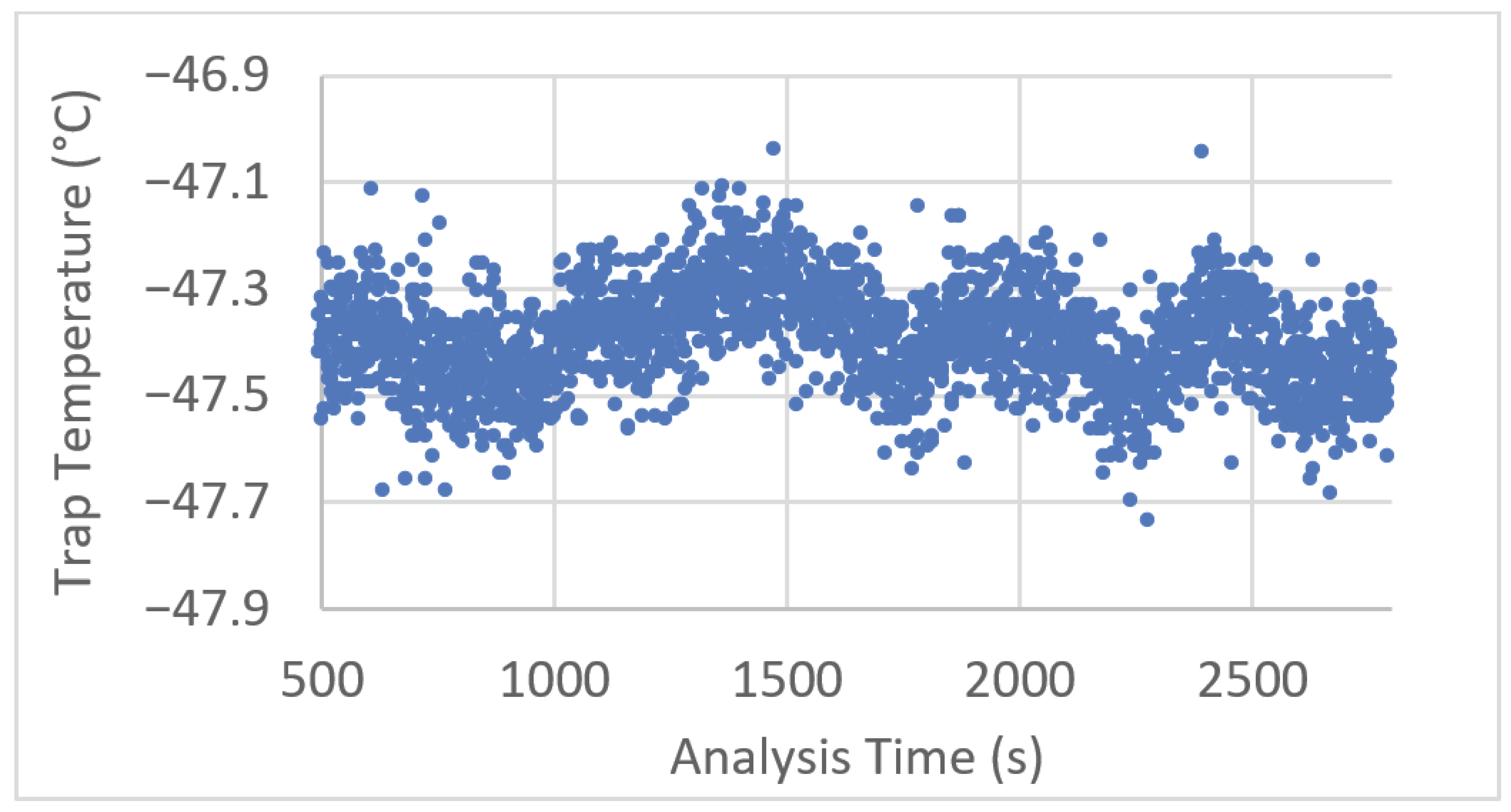

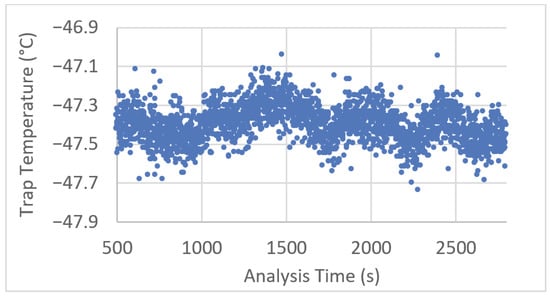

3.4. Thermal Independence and Temperature Control of Entry, Exit and Trap Zones

Temperature logs for entrance, trap and exit temperatures were recorded at one s intervals for each analysis to assess temperature control and stability. During isothermal analysis, entry and exit zone temperature error (=(measured − setpoint) temperature) was observed to be randomly distributed around the mean throughout the analysis and within ±0.5 °C of the setpoint. The trap temperature was observed to be marginally higher than the setpoint of −50 °C at approximately −47.5 °C with some variation observed throughout the analysis, as plotted in Figure 2 below.

Figure 2.

Example trap zone temperature plot corresponding to a representative 45 min period of an experiment.

To isolate the cause of this oscillation, the laboratory temperature was monitored for one day at one s intervals, a temperature oscillation period of approximately 1 h with a deviation corresponding to ~2.5 °C was observed; however, this did not match the trap zone oscillation. A Fourier transform of the data above showed a peak corresponding to the modulation period (0.1667 Hz/6 s), implying that some variation can be attributed to the modulation process and the movement of the modulation columns between the zones.

To test entry and exit zone temperature control during temperature programmed analysis, temperature programmes with ramp rates of 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 and 10 °C/min were tested in triplicate. Maximum entry and exit zone temperature error was observed using the above 10 °C/min ramp rate, with minimum, maximum and average errors of −2.13, 1.42 and −0.08 °C for the entry zone and −1.18, 1.25 and 0.03 °C for the exit zone during the temperature ramp. However, these errors apparently did not have any impact on the 2D retention time repeatability of the target experimental data of analytes, which were comparable between the different temperature programmes. Additionally, no correlation between analyte boiling point or retention time and retention time variability was observed. Average 2D retention time standard deviations ranged from 0.003 to 0.015 s, comparable to that observed in Section 3.3. These retention time data are summarised in Table S6 in the Supplementary Materials.

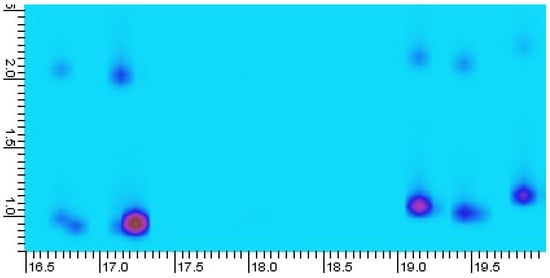

3.5. Analyte Breakthrough

As previously reported by Zoccali et al. in 2019, peak splitting due to inadequate trapping can be observed using this modulator type [18]. This may be attributed to the relatively high trapping temperature of this thermal modulator, −50 °C, when compared to liquid nitrogen-based cryogenic and cryogen-free systems, typically trapping at −190 and −90 °C, respectively [19,20]. During temperature-programmed analysis of the eucalyptus oil sample, similar peak splitting was observed for some early eluting compounds, as shown in Figure 3. A pragmatic solution proposed by Zoccali et al. is to reduce the carrier gas average linear velocity, which should decrease the transport velocity of analytes in the gas phase, in order to improve the analyte trapping process. Another solution is to use an alternative, more retentive modulator column, such as the HV modulator column supplied by the manufacturer, reported to be effective in trapping C5–C30 (n-alkanes). Guan et al. 2019 [14], demonstrated trapping down to C2 using a special modulation column, comprised of a RT-Q-Bond column (0.22 m, 0.25 mm i.d., 8 µm film thickness, Restek, Bellefonte, PA, USA) with a deactivated capillary spliced to either end (0.5 m, 0.25 mm i.d., Agilent Technologies) [14].

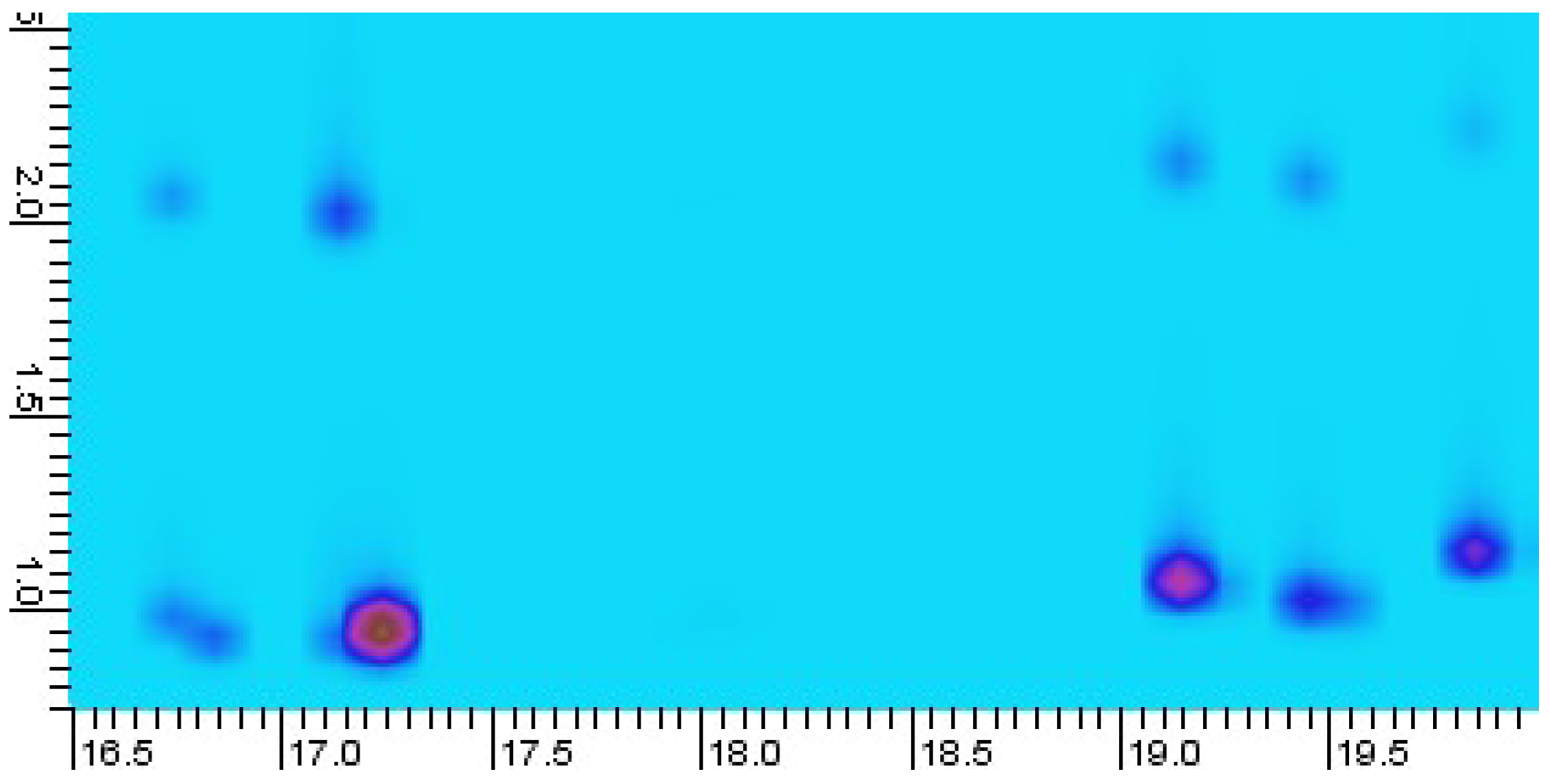

Figure 3.

Portion of eucalyptus oil GC×GC-MS chromatogram, with peak splitting occurring for C10 compounds (α-pinene elutes at 17.2 min and β-myrcene at 19.2 min). y-axis 2D retention unit is in s. The darker blue spots at about 2D retention = 1.0 s are analytes, with the upper lighter blue being ‘mirror’ or breakthrough peaks.

3.6. Summary

Compared to traditional cryogenic modulators, the solid-state modulator offers substantial practical advantages, including compact design, cryogen-free operation, and, as demonstrated, adequate thermal stability with reproducible 1D and 2D retention times. While well suited to routine GC×GC analyses and temperature-programmed operation, its higher minimum trapping temperature may limit performance for very volatile analytes or high carrier-gas velocities, requiring careful optimisation of analytical conditions.

4. Conclusions

The performance of a solid-state modulator was evaluated, based on a benchmarking framework outlined in this study, which can be further used in the evaluation of thermal and other modulators. This can allow for a systematic comparison of modulation strategies and ultimately facilitate a more informed and effective adoption of GC×GC.

The stability of entrance, trap and exit zones was monitored in both isothermal and temperature programmed modes and demonstrated excellent stability and therefore excellent 1D and 2D retention time repeatability. The average 2D retention time standard deviation (ranging from 0.000–0.023 s) was determined to be 0.014 s, corresponding to less than a single acquisition datapoint. Some limitations in analyte trapping were observed, though workarounds are suggested.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting material can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/separations13020065/s1, Table S1: Standard preparation table, showing compound, standard source and corresponding nominal concentration (µg/L); Table S2: 1D Retention times for target analytes in replicate 1D isothermal analysis; Table S3: 1D retention time reproducibility varying both modulator start time and modulation period. Where gaussmaxima refers to the 1D retention time of the fitted gaussian distribution, and modmaxima refers to the 1D retention time of the tallest modulated peak; Table S4: 1D Retention times for target analytes in replicate GC×GC isothermal analyses, based on retention time of the largest modulated peak; Table S5: 2D retention times for target analytes in replicate GC×GC isothermal analysis; Table S6: 2D retention time standard deviation (σ) in s corresponding to 10 features (i.e., selected compounds) identified in eucalyptus oil chromatogram, corresponding to temperature ramp rates shown in first row of the Table. Matlab Script for fitting Gaussian distribution to 1D elution profile. Supporting Material, including retention time repeatability data and Matlab script for fitting Gaussian distribution to 1D peak elution profiles (.docx).

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, methodology, investigation J.D. and P.J.M.; formal analysis, software, writing—original draft preparation J.D.; writing—review and editing J.D. and P.J.M.; supervision P.J.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This publication was prepared in the context of research carried out for the VANDALF project under grant agreement no 9067-00032B and supported by the Innovation Fund Denmark, in addition to the D4RunOff project, funded by the European Commission under the Horizon Europe programme with Grant Agreement number 101060638.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Liu, Z.; Phillips, J.B. Comprehensive Two-Dimensional Gas Chromatography Using an on-Column Thermal Modulator Interface. J. Chromatogr. Sci. 1991, 29, 227–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muscalu, A.M.; Górecki, T. Comprehensive Two-Dimensional Gas Chromatography in Environmental Analysis. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2018, 106, 225–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, Y.F.; Perlmutter, P.; Marriott, P.J. Untargeted Metabolic Profiling of Eucalyptus Spp. Leaf Oils Using Comprehensive Two-Dimensional Gas Chromatography with High Resolution Mass Spectrometry: Expanding the Metabolic Coverage. Metabolomics 2017, 13, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stilo, F.; Liberto, E.; Reichenbach, S.E.; Tao, Q.; Bicchi, C.; Cordero, C. Untargeted and Targeted Fingerprinting of Extra Virgin Olive Oil Volatiles by Comprehensive Two-Dimensional Gas Chromatography with Mass Spectrometry: Challenges in Long-Term Studies. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2019, 67, 5289–5302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muscalu, A.M.; Edwards, M.; Górecki, T.; Reiner, E.J. Evaluation of a Single-Stage Consumable-Free Modulator for Comprehensive Two-Dimensional Gas Chromatography: Analysis of Polychlorinated Biphenyls, Organochlorine Pesticides and Chlorobenzenes. J. Chromatogr. A 2015, 1391, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amaral, M.S.S.; Nolvachai, Y.; Marriott, P.J. Comprehensive Two-Dimensional Gas Chromatography Advances in Technology and Applications: Biennial Update. Anal. Chem. 2020, 92, 85–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luong, J.; Guan, X.; Xu, S.; Gras, R.; Shellie, R.A. Thermal Independent Modulator for Comprehensive Two-Dimensional Gas Chromatography. Anal. Chem. 2016, 88, 8428–8432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marriott, P.J.; Kinghorn, R.M. Longitudinally Modulated Cryogenic System. A Generally Applicable Approach to Solute Trapping and Mobilization in Gas Chromatography. Anal. Chem. 1997, 69, 2582–2588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boswell, H.; Carrillo, K.T.; Górecki, T. Evaluation of the Performance of Cryogen-Free Thermal Modulation-Based Comprehensive Two-Dimensional Gas Chromatography-Time-of-Flight Mass Spectrometry (GC×GC-TOFMS) for the Qualitative Analysis of a Complex Bitumen Sample. Separations 2020, 7, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siri, D.N.B.C.; Zhao, Z.; Guan, X.; Goh, S.Y.; Chong, N.S.; Marriott, P.J.; Wong, Y.F. Rapid Determination of Methamphetamine, Methylenedioxymethamphetamine, Methadone, Ketamine, Cocaine, and New Psychoactive Substances in Urine Samples Using Comprehensive Two-Dimensional Gas Chromatography. Metabolites 2024, 14, 643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, C.; Xie, W.; Su, Z.; Wen, X.; Ma, T. Quantitative Analysis and Characterization of Fl Oral Volatiles, and the Role of Active Compounds on the Behavior of Heortia vitessoides. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1439087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhusangkha, G.D.M.P.; Siow, L.F.; Amaral, M.S.S.; Marriott, P.J.; Thoo, Y.Y. Impact of Thermal Processing and Emulsification Methods on Spice Oleoresin Blending: Insights for Flavor Release and Emulsion Stability. Food Chem. 2024, 460, 140751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouyang, J.; Jiang, R.; Chen, H.; Liu, Q.; Yi, X.; Wen, S.; Huang, F.; Zhang, X.; Li, J.; Wen, H.; et al. Characterization of Key Odorants in ‘Baimaocha’ Black Teas from Different Regions. Food Chem. X 2024, 22, 101303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, X.; Zhao, Z.; Cai, S.; Wang, S.; Lu, H. Analysis of Volatile Organic Compounds Using Cryogen-Free Thermal Modulation Based Comprehensive Two-Dimensional Gas Chromatography Coupled with Quadrupole Mass Spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. A 2019, 1587, 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.Y.; Lu, Y.; Du, Y.; Wang, W.L.; Yang, L.L.; Wu, Q.Y. Comprehensive GC×GC-QMS with a Mass-to-Charge Ratio Difference Extraction Method to Identify New Brominated Byproducts during Ozonation and Their Toxicity Assessment. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 403, 124103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nolvachai, Y.; McGregor, L.; Spadafora, N.D.; Bukowski, N.P.; Marriott, P.J. Comprehensive Two-Dimensional Gas Chromatography with Mass Spectrometry: Toward a Super-Resolved Separation Technique. Anal. Chem. 2020, 92, 12572–12578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adcock, J.L.; Adams, M.; Mitrevski, B.S.; Marriott, P.J. Peak Modeling Approach to Accurate Assignment of First-Dimension Retention Times in Comprehensive Two-Dimensional Chromatography. Anal. Chem. 2009, 81, 6797–6804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zoccali, M.; Giocastro, B.; Tranchida, P.Q.; Mondello, L. Use of a Recently Developed Thermal Modulator within the Context of Comprehensive Two-Dimensional Gas Chromatography Combined with Time-of-Flight Mass Spectrometry: Gas Flow Optimization Aspects. J. Sep. Sci. 2019, 42, 691–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ZOEX Corporation ZX1 Thermal Modulator, Technical Specifications. 2024, pp. 1–2. Available online: https://zoex.com/zx1-thermal-modulator/ (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- ZOEX Corporation ZX2 Thermal Modulator, Technical Specifications. 2024, pp. 1–2. Available online: https://zoex.com/zx2-thermal-modulator/ (accessed on 10 February 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.