Abstract

Blood is a key biological specimen in forensic analysis for both living and deceased individuals, playing a crucial role in drug testing, blood typing, DNA analysis, and bloodstain pattern examination. In forensics, the decomposition of blood holds particular importance because it is a major biological fluid in the human body and undergoes early chemical changes that attract insects and microorganisms to cadaveric sources. The odor signatures produced during the putrefactive process have recently gained forensic relevance, prompting studies to investigate volatile organic compounds (VOCs) from blood, tissues, animal proxies, and human cadavers to enhance human remains detection and recovery via technological or biological means. This study focuses on cadaveric blood odor profiling, evaluating VOC signatures from human cadavers in an anatomy laboratory using solid-phase micro-extraction (SPME) and gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC/MS) upon body receipt. A second phase entailed a degradation analysis using 7 human cadavers and a total of 28 postmortem samples repeatedly sampled over a 4-week period. The findings revealed an increasingly complex odor profile as decomposition progresses, with a notable rise in both the variety and concentration of VOCs. Room temperature samples exhibited a more diverse and rapid VOC release, while refrigerated samples showed slower degradation. These insights contribute to a deeper understanding of decomposition patterns and ultimately refine human remains detection methodologies.

1. Introduction

Unsolved homicides remain a significant issue in forensic investigations, with nearly 346,000 cases of homicide and meticulous murders remaining unresolved between 1965 and 2023, as per the FBI’s Uniform Crime Report data analyzed by the Murder Accountability Project. Despite progress in forensic science, the capability to locate and identify human remains is an ongoing challenge in criminal investigations [1]. Blood is as an important biological specimen in forensic analysis as it aids in drug testing [2,3,4], blood typing, DNA profiling [5], and bloodstain pattern analysis [6], etc. [7]. Although blood contains a small fraction of the total human volatilome, there is a growing importance for its application in disease detection, and forensics [8]. Researchers have recently characterized and categorized volatile organic compounds (VOCs) from peripheral blood-derived plasma obtained from a large cohort of healthy individuals [9]. GC × GC–TOFMS identified 401 distinct compounds, of which 34 were assigned as core molecules as they were abundantly present across all samples. The core VOCs were aliphatic hydrocarbons (∼53%), followed by aromatic compounds (∼21%) and carbonyl compounds (∼18%) [9].

With respect to VOC profiling, decomposition research has explored various biological and environmental factors, including soil [10,11], tissue [12], human remains [12,13,14,15,16,17], and several seasonal conditions. Both human cadavers and animal proxies have expanded our understanding of decomposition processes [18]. Patel et al. found that human cadavers release a complex mixture of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) within the first 72 h postmortem, with 104 compounds consistently detected across multiple donors. These early VOC profiles, dominated by aliphatic compounds, esters, and aromatics, varied between individuals but showed dynamic changes over time, highlighting their potential as early forensic decomposition markers [19]. The VOC profile of decomposing human remains is extraordinarily complex, consisting of up to 832 volatile organic compounds, including alcohols, ketones, hydrocarbons, and sulfur-containing compounds [20]. The odor profiling of cadaveric blood has gained forensic significance, as postmortem biochemical changes result in the release of distinctive VOCs. These compounds offer a chemical fingerprint that can be analyzed to improve the detection and recovery of human remains, whether by instrumental or biological means.

Research on volatile organic compounds (VOCs) released from cadaveric blood provides wide-ranging forensic benefits by improving detection strategies and increasing investigative accuracy. This work also advances forensic canine training, as identifying blood-specific VOCs enables the development of more consistent and effective odor-based training aids for human remains detection dogs. Moreover, the study of blood odor signatures has important implications for disaster victim identification and clandestine grave detection, where fluctuating environmental conditions influence decomposition rates and VOC release. Beyond canine applications, characterizing distinct VOC markers from decomposing blood also supports the creation of portable gas-sensing technologies, such as electronic noses (e-noses), which could offer non-invasive, real-time analytical capability in forensic investigations [21].

Blood VOCs & Detection Dogs

Detection dogs play a crucial role in human remains investigations due to their exceptional olfactory capabilities, which allow them to locate trace biological evidence that may be overlooked by conventional forensic techniques. Given the constantly evolving intensity and chemical composition of the odor throughout decomposition, Human Remains Detector Dogs (HRDD) must be trained to detect and recognize a wide spectrum of VOCs emitted during various stages [22].

Their ability to detect blood, often present in minute, degraded, or concealed forms, makes them especially valuable in complex crime scenes and outdoor environments where physical evidence may be dispersed or compromised [23]. Well-trained blood detection dogs can identify both fresh and aged blood deposits across a variety of substrates, providing investigators with rapid, reliable leads that can significantly narrow search areas and support the reconstruction of events. As a result, these dogs serve as indispensable assets in forensic investigations, enhancing the detection of human remains and contributing to more efficient and accurate case resolution [23,24,25,26,27].

Blood is a valuable training aid for blood detection dogs (BDDs) and human remains detection dogs (HRDDs) as fresh blood is readily available for handlers due to fewer legal or ethical concerns than obtaining other human tissue samples and decomposition by-products. Blood releases volatile organic compounds (VOCs) generated through the degradation of its proteins [12]. Recent studies have focused on characterizing VOC composition and understanding VOC evolution in aging blood, showing differences in specific compounds from fresh to degraded blood samples [12,22,25,28,29,30].

For example, Chilcote et al. studied the weathering of blood on surfaces like concrete and varnished wood over a three-month period using headspace SPME and GC × GC–TOFMS [28]. They found that surface type significantly influenced the VOC profile, with porous and nonporous surfaces exhibiting distinct compounds. Rust et al. emphasized how fresh blood’s VOC profile differs from degraded blood over time, notably based on surface material (i.e., porous (cotton) and non-porous (aluminum)). Fresh blood showed a distinct VOC profile compared to aged blood, while blood aged over a week exhibited a stable VOC pattern. In non-porous samples, aldehydes and aromatics were predominant, while higher levels of aromatics, alcohols, and hydrocarbons characterized porous samples [29]. A subsequent study explored the detection limits of blood by both canine and analytical methods on washed cotton clothing, finding that repeated washing eliminated detectable blood VOCs, replacing them with detergent-related compounds. However, canines could still detect blood in samples washed up to five times, underscoring the differing sensitivities of analytical and biological detection methods [30]. A study using headspace solid-phase micro-extraction/gas chromatography–mass spectrometry and chemometrics experimented with the training of canines on blood VOCs. The results showed distinct odor profiles between 1 h and 2-week time windows, including fresh, intermediate, and aged stages of decomposition. HRD canine trials confirmed these changes, with dogs having difficulty detecting fresh blood (1–2 h old) and the highest detection rate for aged blood (34–36 h (about 3 days) old). Understanding these odor variations ensures that SAR, HRD, and BBD training addresses every stage of blood decomposition [31]. Furthermore, studies by Forbes et al. have shown that blood VOCs change over time and are strongly influenced by storage conditions, with fresh and aged blood exhibiting distinct chemical signatures, and different preservation methods—such as refrigeration, freezing, or room temperature storage—further altering the VOC composition [22]. These findings underscore the importance of considering both temporal and environmental factors when studying blood odors in forensic contexts.

While prior research has shed light on blood odor profiles—examining substrate effects, storage, and temporal changes—these controlled studies fail to capture the full complexity of postmortem conditions, as they have utilized living donors for blood acquisition. Direct collection of blood from deceased individuals has been explored in only a limited number of studies, leaving a notable gap in our understanding of blood odor profiles under authentic postmortem conditions.

Rendine and colleagues demonstrated that decomposing human cadaver blood emits distinct volatile organic compound (VOC) odor signatures over time and that professionally trained dogs can reliably detect these VOCs from cadaveric blood samples even at advanced stages of decomposition [25]. Hoffman et al. demonstrated that decomposing human tissues, including blood, muscle, skin, bone, and others, produce distinct volatile organic compound (VOC) odor profiles and showed that no single VOC is universally present across all tissue types. These findings are particularly relevant to the present study, as blood is a commonly used HRD training aid; understanding how blood-derived VOCs compare to other tissue sources is essential for evaluating canine generalization and training efficacy [12].

Given the limited research on volatile organic compounds (VOCs) derived from blood collected directly from human cadavers, this study sought to expand the available data by providing a larger sampling set of cadaveric blood analyses. The aims of the study were twofold: first, to characterize the VOC signatures of cadaveric blood immediately upon body receipt in an anatomy laboratory using solid-phase micro-extraction (SPME) coupled with gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC/MS); and second, to investigate the temporal changes in these VOC profiles through an aging analysis of collected blood from seven human cadavers, sampled repeatedly over a four-week period, while also examining the effects of donor biological sex and the timing of blood withdrawal postmortem.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Donor Information

The study involved pre-treatment of collection and storage materials, including syringes, glass vials, and septa, to minimize contamination. 7 mL Glass screw top vials PTFE/silicone septa (SUPELCO, Sigma Aldrich, (Burlington, MA, USA)) were sterilized at 100 °C for 2 h, while screw-top PTFE/silicone septa were sterilized for 15 min. Sterilized items were stored in a fume hood to ensure any detected VOCs originated from cadaveric blood. Un-embalmed human cadavers were appropriately acquired through the Institute of Anatomical Sciences, Willed Body Program at Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center, (Lubbock, TX, USA), and approved for use by the Institutional Anatomical Review Committee. Cadaver specimens were handled in accordance with university policy and State of Texas regulations as determined by State Law and the Texas Funeral Services Commission. Blood samples were collected directly from the jugular vein (baseline study, feasibility assessment) and heart (longevity) using sterile 60 mL syringes by trained personnel in a controlled anatomy laboratory environment, ensuring safe handling and reducing contamination risk.

2.2. Baseline Study

The first phase of the study evaluated headspace odor volatiles from cadaveric jugular vein blood samples to obtain a chemical odor profile of recently deceased individuals. Blood was collected from the jugular vein using a small 5 cc Monoject Syringe. A total of 9 cadavers (5 females and 4 males) were sampled within 82 h postmortem, with 6 sampled within 24 h of death. A total of 4 blood samples were collected per individual plus a blank vial to monitor background interferences. Table 1 provides a detailed description of individual cadaveric characteristics, including time of death, sampling time, and available body conditions.

Table 1.

Summary of Cadaver Data Utilized in Baseline Development.

2.3. Longevity Study

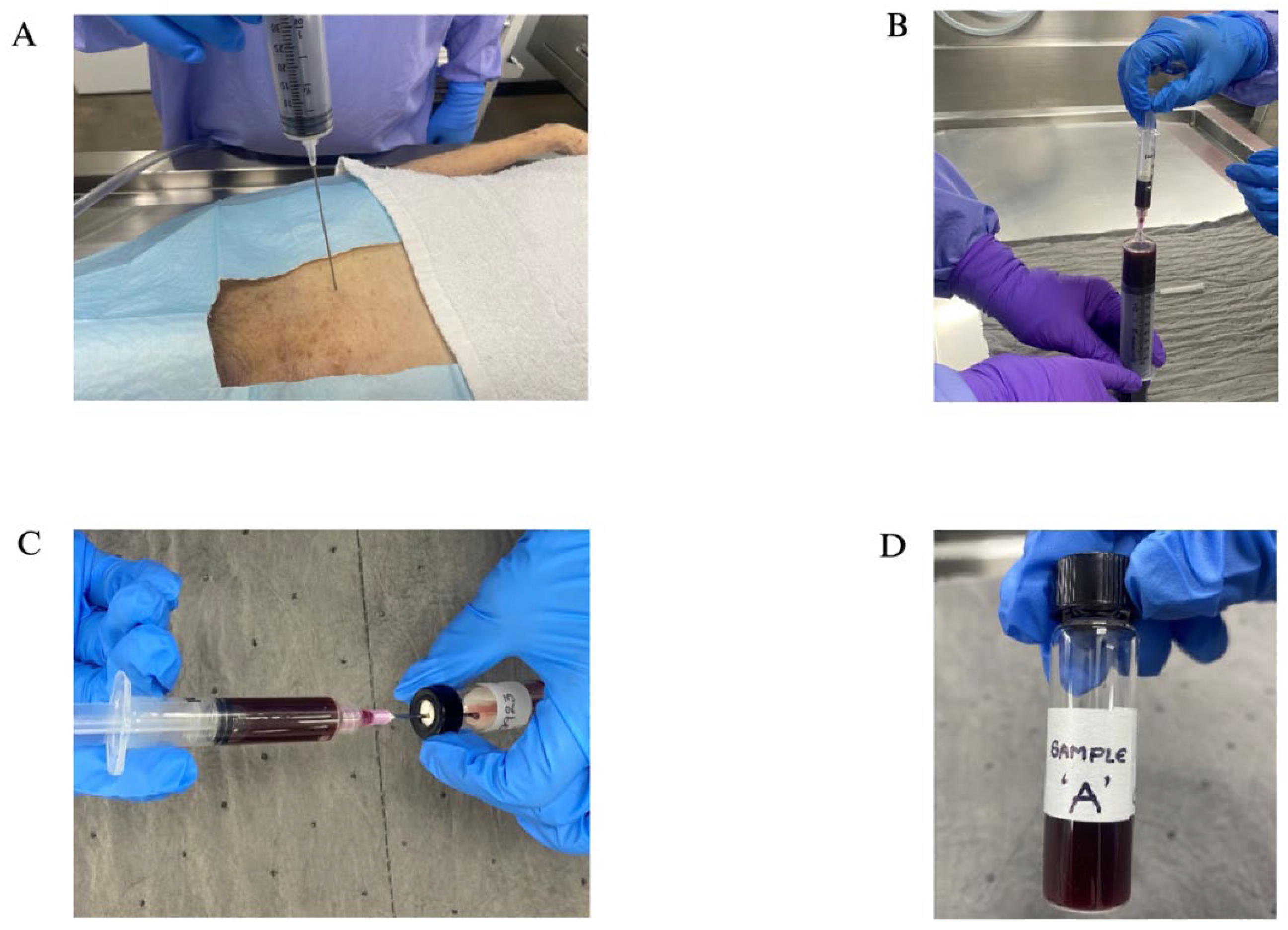

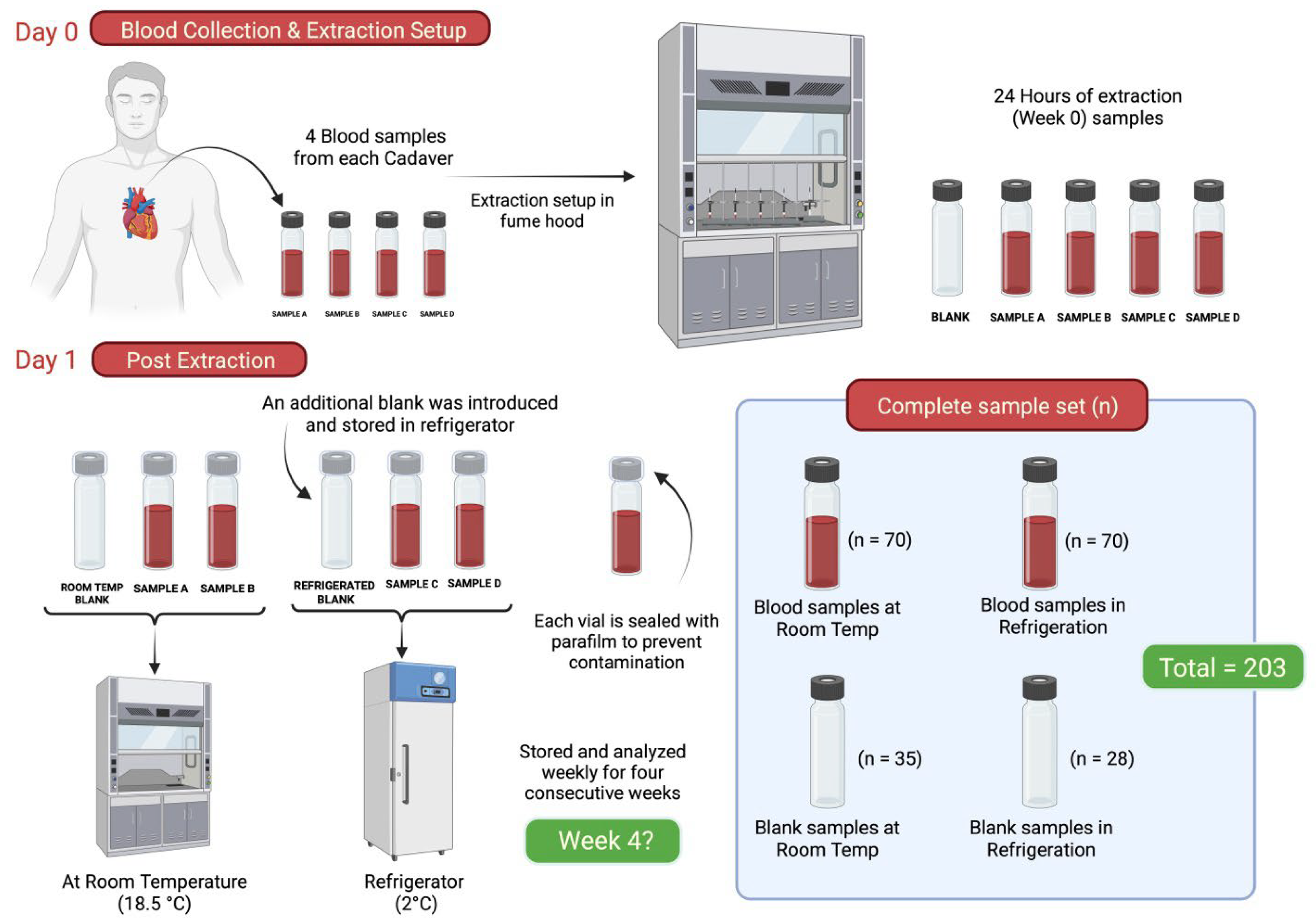

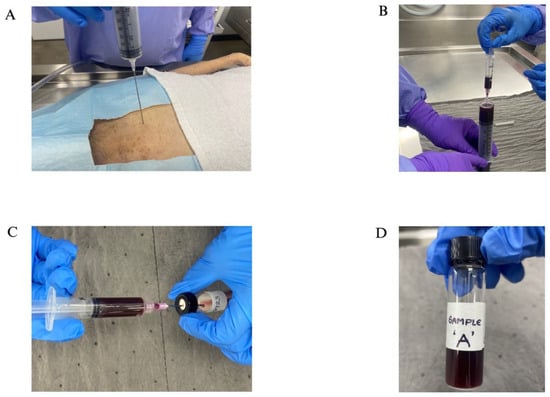

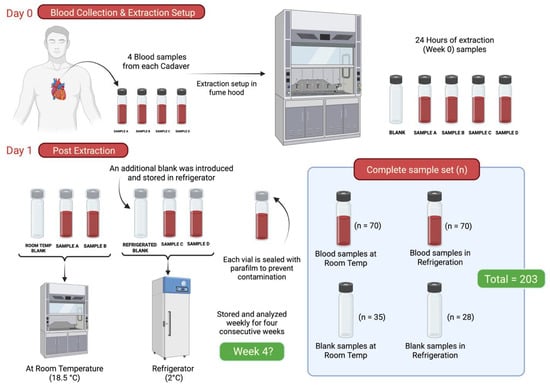

The second objective of this study aimed to assess the impact of various environmental conditions on the persistence of cadaveric odor profiles. Seven cadavers were used in this phase as can be seen in Table 2, and heart blood samples (for temporal stability) were collected and later transferred into glass vials as shown in Figure 1. Twenty-eight blood samples were obtained from seven donors and evenly divided into two groups (n = 14). Blood samples were divided into two group treatment groups with a corresponding blank. One group was stored at 2 °C under refrigerated conditions, while the other was maintained at ambient temperature (18.5 °C) within a laboratory fume hood. To monitor potential contamination and assess background levels, two blank vials—one for each environmental condition—were incorporated into the storage evaluation. Importantly, the same set of tubes sampled at Week 0 was re-sampled at each subsequent weekly time point for the duration of the four-week study. Thus, there were five total sampling events (Week 0 through Week 4), and at each time point, both blood tubes per treatment group were sampled concurrently, along with their corresponding blank. The vials were fitted with PTFE/silicone septa, sealed, and covered with parafilm. Figure 2 provides a schematic of the experimental sampling scheme for the storage period phase.

Table 2.

List of the Cadavers information used for this study for storage.

Figure 1.

(A) A 60 mL needle puncturing the heart for blood collection; (B) Collecting the blood into a smaller 5 cc syringe to transfer; (C) Transferring blood into a sample vial with the help of a smaller 5 cc syringe; (D) A labeled vial with sample.

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of the methodology for the analysis of longevity samples.

2.4. Instrumental Analysis

The study used Solid-Phase Micro-extraction (SPME) to extract volatile organic compounds (VOCs) from cadaveric blood samples. A DVB/CAR/PDMS SPME fiber (Supelco, Sigma-Aldrich, Burlington, MA, USA) was utilized and exposed to the postmortem blood samples for 24 h. This fiber was selected due to previous decomposition odor work utilizing SPME extraction procedures in sample matrices such as blood, human remains tissue, and live human scent [9,10,17,18,19]. The fiber was desorbed into the GC injector port for a period 8 min. The extracted VOCs were analyzed using gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC–MS). An Agilent 7890A gas chromatograph (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) and a 5975C mass selective detector (MSD) (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) were used for the separation and identification of extracted VOCs. The analysis was carried out with helium as the carrier gas at a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min. Samples were injected in split less mode at 250 °C and separated on a J&W Scientific capillary column (30 m × 250 µm, 0.25 µm film) (Restek Corporation, Bellefonte, PA, USA). The inlet had an initial temperature of 250 °C with a pressure of 7.1 psi. The oven temperature program began with an initial hold at 35 °C for 1 min, followed by a ramp of 80 °C per minute up to 120 °C, then increased at 10 °C per minute to 260 °C, with a final ramp of 40 °C per minute. Spectra were acquired in full scan mode with a mass range of 45–550 mu with a total run time of 23.5 min, and compound identification was confirmed with the NIST2017 mass spectral library and concurrent external standards, where possible. Analytical standards of 2-undecanone (Acros Organics, Fair Lawn, NJ, USA), anisole (Acros Organics, Fair Lawn, NJ, USA), butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), dimethyl trisulfide (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Ward Hill, MA, USA), dimethyl disulfide (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Ward Hill, MA, USA), dodecane (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), and undecane (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) were used as external standards for compound identification.

2.5. VOC Analysis

Chromatographic data were processed using ChemStation software (Version 10.1.49, Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Compound identification was based on comparison with the NIST 2017 mass spectral library, with a match threshold of ≥ 90% and verification with chemical standards where possible. Principal component analysis (PCA) was used to assess volatile profiles across storage conditions, cadavers, and collection weeks. Multifactorial analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to evaluate differences in VOC detection and concentration. All statistical analyses were conducted in JMP (v18.0.0, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Study

A total of nine cadavers were sampled, with postmortem intervals (PMIs) ranging up to 82 h. Of these, six were sampled within the first 24 h after death, providing VOC profiles representative of the earliest stages of decomposition. The restricted sampling window reduced environmental interference and strengthened the reliability of VOCs detected as indicators of initial postmortem biochemical and microbial activity.

The analysis revealed distinct patterns in VOC presence and frequency, with several compounds emerging as consistent markers of early postmortem change. Compounds meeting a ≥90% spectral match threshold (Table 3) were further categorized by functional group to enable clearer structural and chemical interpretation.

Table 3.

Frequency chart of the Primary VOCs identified during the Baseline Study. The numbers in the table represents the frequency of occurrence of each compound in 4 blood samples. (B1–9 = represents the subject identification code).

Among the VOCs identified, several compounds exhibited high detection frequency, appearing in ≥50% of the blood samples analyzed (total jugular vein cadaveric blood n = 36 samples). Percentages reported in parentheses indicate the frequency of occurrence of the analyte across all 36 samples. Notably, 1,3-bis(1,1-dimethylethyl)-benzene, was found in 86.11% of the samples, followed by D-limonene (66.67%) and 3,3,5-trimethyl- cyclohexanone (52.78%). D-Limonene, a common terpenoid, is frequently detected in biological fluids and environmental matrices, and its presence could reflect both endogenous biosynthesis and external exposure [20]. Cyclohexanone derivatives are often linked to the oxidative breakdown of lipids and suggest ongoing tissue decomposition.

Moderately frequent VOCs, detected in 20% to 50% of samples, included compounds such as 2,5-cyclohexadiene-1,4-dione, 2,6-bis(1,1-dimethylethyl)-(44.44%), tetradecane (44.44%), indole (38.89%), diphenyl ether (33.33%), and isobornyl acetate (30.56%). These compounds are indicative of both microbial activity and biochemical degradation of proteins and fatty acids. Indole, a metabolite of tryptophan, is a known biomarker of bacterial decomposition, particularly associated with anaerobic bacterial metabolism in putrefaction processes [9]. Tetradecane and isobornyl acetate are commonly associated with the degradation of lipids and may serve as markers for mid-stage decomposition.

Compounds detected in less than 20% of cases were classified as low-frequency VOCs. This group included nonanal (19.44%), o-xylene (19.44%), caryophyllene (19.44%), and p-cresol (16.67%). Nonanal is a known aldehyde resulting from the peroxidation of unsaturated fatty acids and is typically observed in later stages of decomposition [21]. Similarly, p-cresol, a phenolic compound produced during the microbial breakdown of tyrosine, is frequently associated with advanced putrefaction [22]. However, in the present study, these assignments are not directly validated, as the baseline study represents the earliest postmortem stage and PMI-stratified validation was not performed. Therefore, stage-specific associations should be interpreted cautiously. The variability in detection of these low-frequency VOCs may also reflect differences in environmental conditions or individual-specific factors such as disease status, medications, or cause of death.

The presence and distribution of these VOCs reflect the dynamics of postmortem blood signatures and the complexity of individual variation during the early postmortem period, up to 82 h. Indole, p-cresol, and nonanal strongly suggest microbial colonization and activity, primarily by anaerobic bacteria, which dominate in the cadaveric environment during putrefaction. VOCs such as tetradecane and cyclohexanone are products of lipid degradation, providing further evidence of tissue breakdown. These findings contribute to the growing body of evidence on VOC analysis in forensic science and provide candidate features and hypotheses for subsequent studies aimed at estimating time since death or exploring potential indicators of cause of death.

Additionally, the presence of certain environmental or exogenous compounds, such as benzene derivatives and D-limonene, may indicate postmortem exposure to ambient pollutants or contamination during body storage or handling. Such compounds must be interpreted with caution in forensic investigations to differentiate between endogenous production and external introduction.

3.2. Storage Study

Postmortem blood samples were collected from seven cadavers, resulting in 28 sample replicates (four per cadaver). These samples were analyzed once per week over a four-week period. Additionally, two environmental control blanks were introduced for each subject sample set at Week 0. For each subject, one control sample was stored at room temperature (≈18.5 °C) and another under refrigeration (2 °C), alongside the corresponding blood samples. In total, 203 replicates were processed as part of the longevity study.

Over the four-week observation period, 85 volatile organic compounds (VOCs) were detected above cadaveric blood, with 65 observed under room temperature storage. Table 4 depicts the results across the 4-week period, organized by subject, week, room temperature storage condition, and functional group. The presence of a compound is indicated by an “X,” signifying that the compound was detected consistently across both replicates of the sample. In total, 14 functional groups were represented. Among terpenes, caryophyllene was the most common, while copaene and longifolene appeared infrequently. Within the carboxylic acids group, only valproic acid was consistently observed, detected in a single cadaver across four sampling points. Notably, no methylthio compounds were recorded under room temperature conditions.

Table 4.

Primary volatile organic compounds (VOCs) identified during the longevity study at Room Temperature, conducted over a four-week period for each subject. The presence of a specific compound is denoted by “X” in the corresponding cell. (W0–4 are weeks).

The amines category was represented solely by 2,6-xylidine, suggesting limited nitrogen-containing volatiles. Five aromatic compounds were identified, with indole and pyridine detected most frequently. Phenols were widely present across all cadavers, while ketones were also prominent, with cyclohexanone emerging as the most recurrent. Sulfur volatiles, including dimethyl trisulfide, 2,4-dithiapentane, and dimethyl disulfide, were repeatedly detected and characterized by strong odor signatures.

Alcohols were consistently released during the temporal evaluation, with phenyl ethyl alcohol frequently identified. Several aldehydes appeared across time points, consistent with oxidative degradation processes. Hydrocarbons displayed considerable diversity, while anisole was the most frequent ether. Overall, phenols, ketones, sulfur compounds, and alcohols dominated the VOC profile, underscoring their potential as chemical indicators of blood decomposition under room temperature conditions.

At the refrigeration conditions (2 °C), 72 volatile organic compounds (VOCs) were identified as shown in Table 5, though in lower overall abundance compared to room temperature. Within terpenes, longifolene was absent under refrigeration. Valproic acid persisted in the carboxylic acid group, appearing twice across multiple stages. Amines showed greater representation than at ambient temperature, suggesting enhanced stability at lower temperatures. Indole and pyridine were the most frequently observed aromatics, consistent with trends at room temperature.

Table 5.

Primary volatile organic compounds (VOCs) identified during the longevity study at Refrigeration condition, conducted over a four-week period for each subject. The presence of a specific compound is denoted by “X” in the corresponding cell. (W0–4 are weeks).

Hydroxyl aromatics remained prominent, with seven distinct compounds identified; p-cresol was most common, while eugenol and 3-methylphenol were less frequent. Ketones were represented by 10 compounds, with 2,5-cyclohexadiene-1,4-dione, 2,6-bis(1,1-dimethylethyl)-, and 3,3,5-trimethylcyclohexanone dominating the group. Three sulfur volatiles were detected, with dimethyl trisulfide recurring most often, underscoring its relevance as a potential cold storage marker.

Alcohols were detected in lower abundance than at room temperature, though phenylethyl alcohol remained consistently present. Aldehyde emissions were markedly reduced, with only five compounds observed and decanal being the most frequent. Hydrocarbons appeared across the decomposition period, predominantly alkanes, while anisole was the most recurrent ether among three detected. In the arenes category, benzene, 1,3-bis(1,1-dimethylethyl) was most prominent, appearing 17 times across samples.

3.3. Frequency Analysis of Volatile Emissions

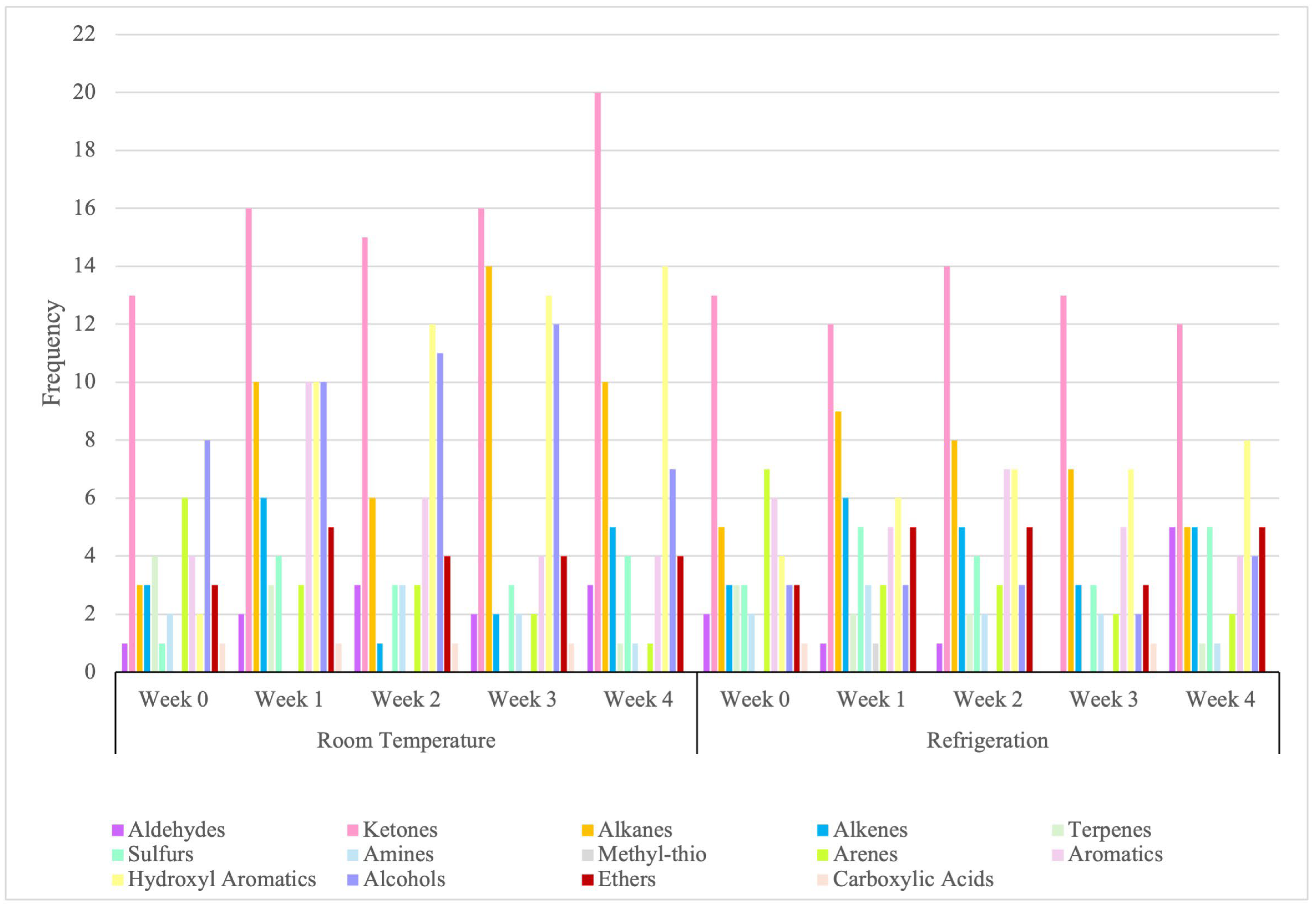

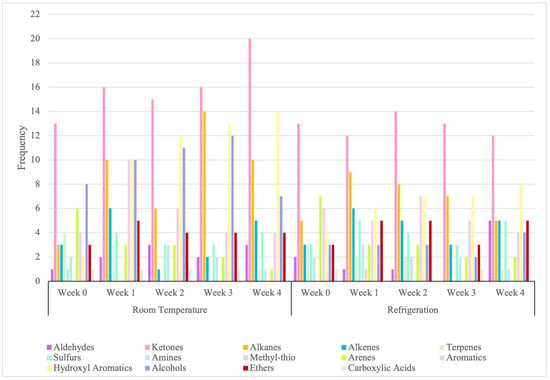

To evaluate temporal shifts in VOCs during cadaveric blood aging, volatiles were divided into the 14 functional group categories for interpretive analysis. The classification provided insight into degradation pathways and functional group persistence.

In Figure 3 across both storage conditions, ketones were the most frequently occurring, with detections increasing from early to late stages, especially under room temperature (RT). Aldehydes were less frequent but showed late-stage increases, especially under refrigeration (RF). Hydrocarbons dominated early to mid-stages, with alkanes peaking in Week 3 under RT. Sulfur volatiles and amines accumulated, reflecting protein degradation, with sulfides showing higher counts under RF. Hydroxyl aromatic increased frequency under RT, while other aromatics diminished over time. Alcohols and ethers were more active under RT, with alcohols peaking in Week 3. Carboxylic acids appeared sporadically. These trends highlight that the VOC profile remains highly dynamic and unstable under both room temperature and refrigeration, with functional groups shifting markedly throughout storage. Even refrigeration does not stabilize these patterns but instead produces its own distinctive trajectory, underscoring that storage conditions fundamentally shape VOC evolution. This reinforces the need for strict, well-defined storage protocols to ensure consistent and interpretable chemical signatures.

Figure 3.

Frequency of functional group occurrence across longevity period.

3.4. Total VOC Accumulation

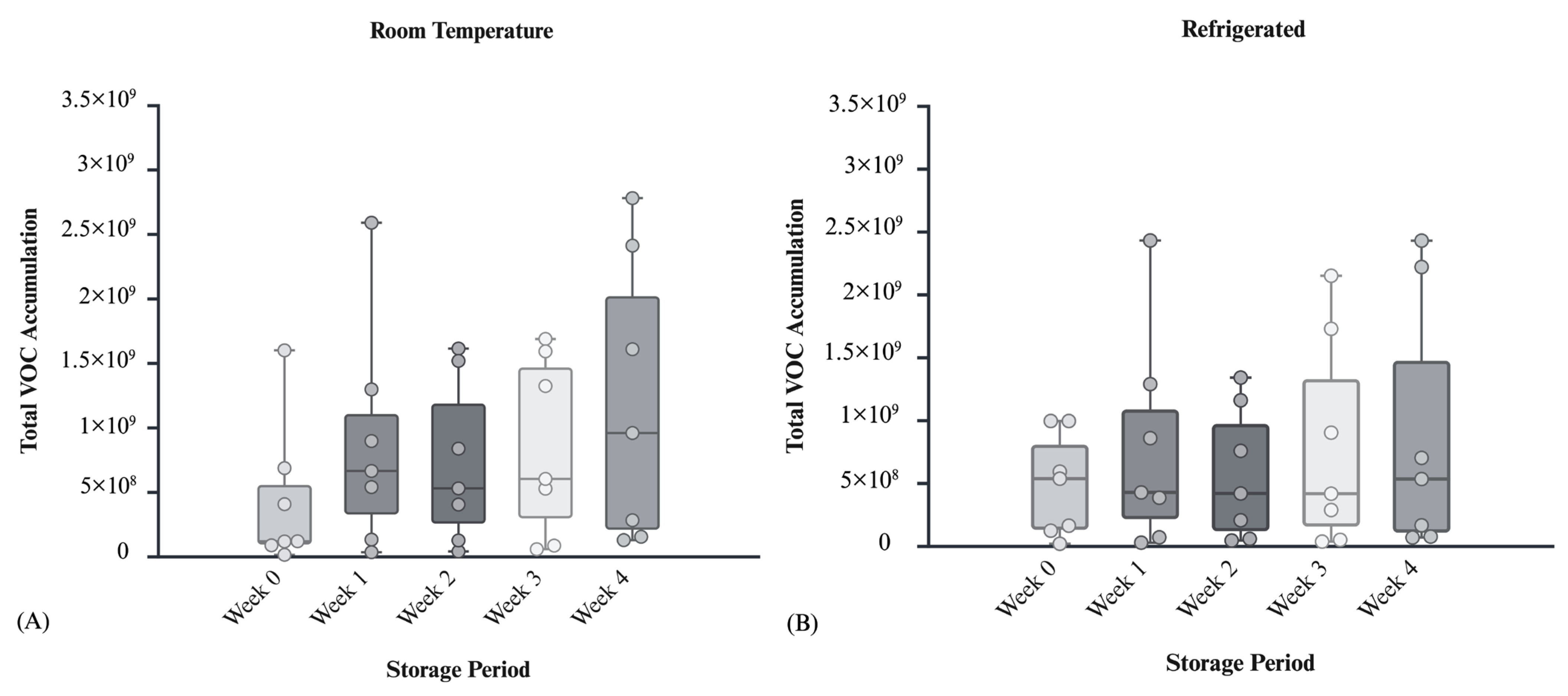

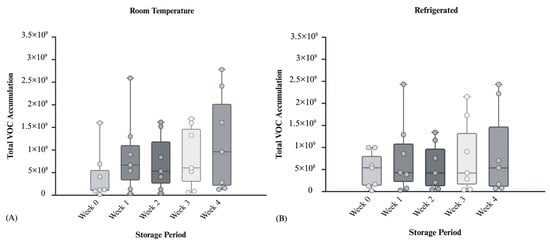

To evaluate the storage progression of the collected postmortem blood samples, total VOC accumulation was analyzed across a four-week period under the two environmental conditions tested. For Figure 4, “total VOC accumulation” was calculated as the sum of GC–MS peak area responses for all odor compounds detected consistently across duplicate analyses of each blood sample set. This summed signal provides a relative, semi-quantitative comparison of overall VOC response across sampling intervals. Box-and-whisker plots were used to visualize the distribution of VOCs across multiple cadaveric samples, identifying potential outliers and central tendency. These plots provide insight into temperature’s influence on volatile abundance as a function of storage time, as well as depicting the VOC accumulation across individual subjects. Each overlaid point represents SPME extractions corresponding to the total VOC accumulation from an individual donor. Data were obtained from seven distinct donors, with each donor contributing two SPME extractions per condition, ensuring that all points represent independent biological replicates.

Figure 4.

(A) VOC accumulation for room temperature condition across all seven bodies over a 4-week period. (B) VOC accumulation for refrigerated condition across all seven bodies over a 4-week period.

Figure 4A exhibits the progression of total VOCs in cadaveric blood samples stored at room temperature. Median VOC levels increased steadily over four weeks, with the highest values observed in Week 4. Variability increased over time, reflecting differences in blood composition and microbial activity. Early weeks showed low emissions, while later weeks showed complex volatile signatures. Figure 4B shows the refrigeration (2 °C), emissions were minimal but gradually increased, reaching levels comparable to room temperature storage by Week 4. Cold storage slows but does not halt VOC release showing only a 1.3-fold decrease in average of primary VOC accumulation compared to room temperature in week 4, highlighting the importance of storage conditions in interpreting VOC profiles for postmortem interval estimation.

3.5. Analysis of Variance (ANOVA)

In this study, ANOVA was employed to test significant effects of time and storage conditions on overall VOC accumulation, thereby supporting a deeper understanding of aging dynamics. Total VOC accumulation was calculated as the sum of GC–MS peak area responses for all volatile compounds consistently detected across duplicate analyses of each blood sample set, with technical replicates averaged at the donor level. This value represents a relative, semi-quantitative measure of overall VOC abundance across storage temperatures and time points. A mixed model test was formed on the average VOC accumulation as a function of week and storage temperature condition. The results show that the environmental storage condition had no statistical significance (p = 0.06). Although total summed VOC signal did not differ significantly across storage temperatures (p = 0.06), the composition of detected VOCs varied among conditions, indicating that storage still influences chemical profiles. However, temporal progression exerted a statistically significant influence on VOC accumulation (p = 0.03). Accordingly, a post hoc Tukey HSD test was applied to resolve week differences among sampling intervals. The analysis revealed significant contrasts between Week 0 and Week 1 (p = 0.04) and between Week 0 and Week 4 (p = 0.03), with the pronounced divergence at Week 4 likely attributable to cumulative biochemical transformations associated with prolonged storage duration.

3.6. Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

Multivariate statistical methods were performed on compounds detected from the various cadaveric blood samples tested within the storage study. It was conducted using primary VOCs, defined as compounds detected across duplicate samples, with input variables consisting of peak area values averaged across duplicate blood sample analyses within each donor set. Overall, two different types of PCA plots were created to evaluate chemical odor profile as a function of biological sex differentiation and postmortem blood collection time (PBCT).

To evaluate the effect of biological sex on VOC profiles from early postmortem blood, PCA was applied to cadaveric samples grouped by biological sex, aiming to identify any sex-related differences in chemical diversity or storage patterns.

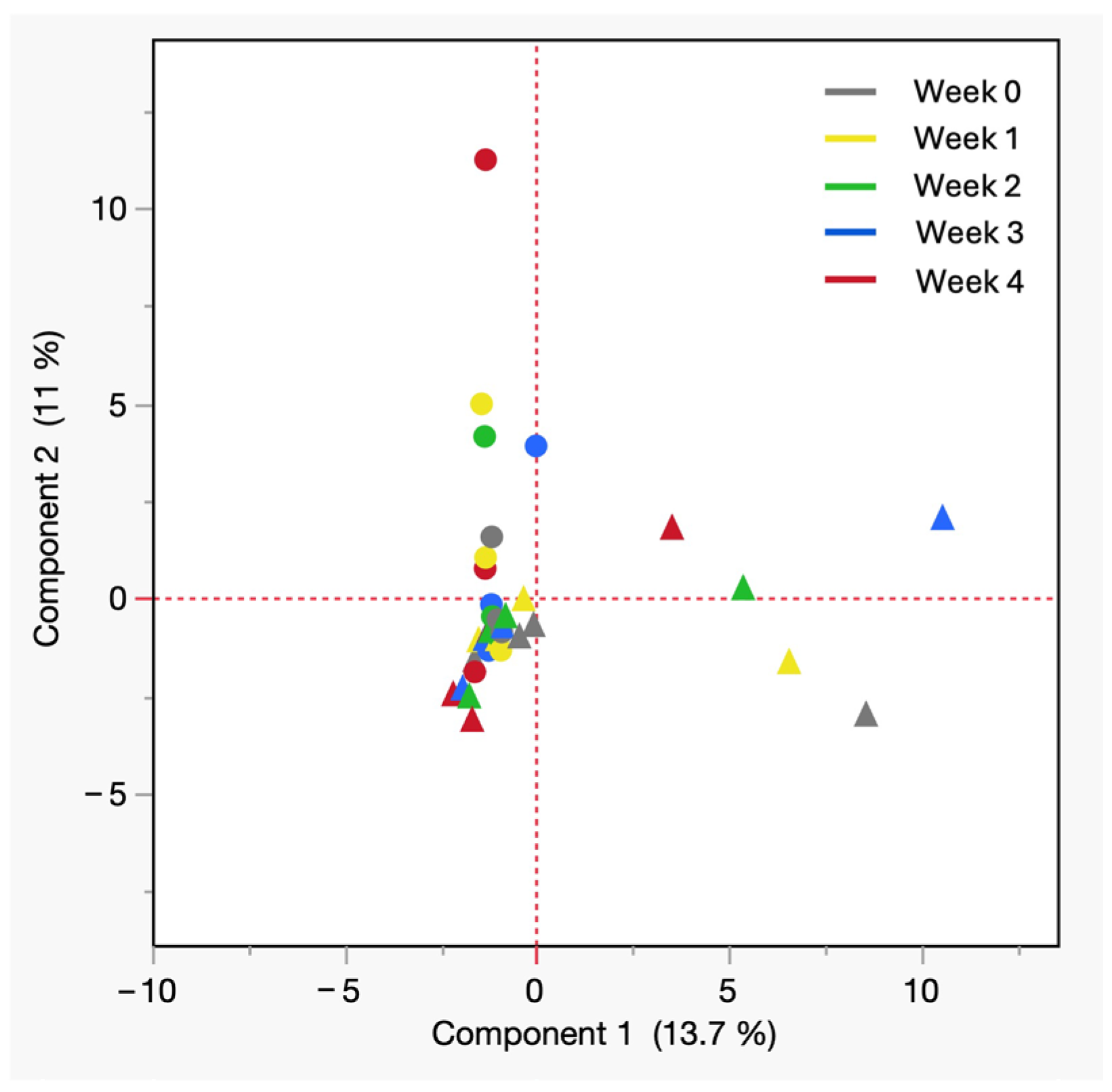

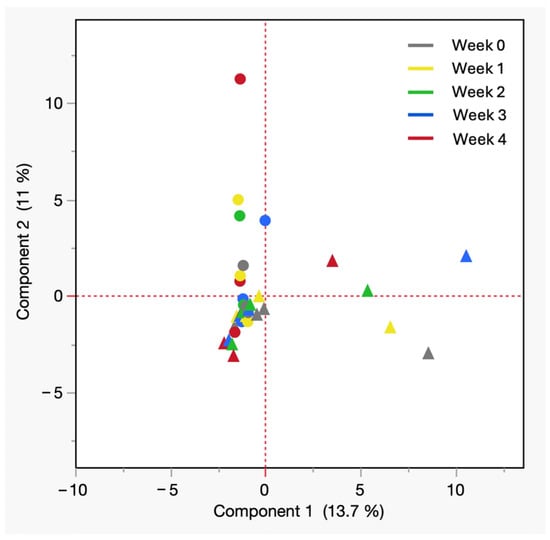

Figure 5 depicts the 2-dimensional PCA plot of cadaveric blood samples stored at room temperature, where the first two principal components explain 24.7% of the total variance (PC1: 13.7%, PC2: 11%). In the PCA plot all postmortem blood collected from males is depicted by different shades of blue circles and that each shade of circle represents a particular week of storage with the darkest being the week 4 (black). It revealed a separation based on sex, with male samples clustered near the second quadrant and female samples dispersed along first and third quadrants, suggesting greater variability in chemical evolution. The horizontal spread of female samples suggests the emergence of sex-specific VOCs or differing rates of compound accumulation. In the PCA model, most of the variables showed positive loadings along the first principal component PC1, indicating that they tend to vary in the same direction and contribute collectively to the main trend in the data. In contrast, a smaller group of compounds displayed negative loadings on the second principal component PC2. These included 3,3,5-trimethylcyclohexanone, acetophenone, methyl isobutyl ketone, phenyl ethyl alcohol, and tetrachloroethylene with most of them belonging to the ketone family. Their negative association with PC2 suggests that these compounds follow a different pattern of variation from the rest of the dataset, which may reflect distinct chemical behavior or source characteristics relevant to the separation and profiling of these analytes. Although PC1 and PC2 capture only ~25% of total variance, the observed trends highlight potential influences of sex and decomposition stage on VOC profiles. These exploratory patterns provide a basis for generating targeted hypotheses for future studies. These findings may reflect biological or biochemical differences, including hormonal, metabolic, or microbial factors. The observed pattern not only supports the hypothesis that sex can influence the volatilome profile of aged postmortem blood, but also aligns with previous findings of distinctive human scent differences based on biological sex from living subjects [32,33]. These results suggest that such sex-based trends may persist into the fresh postmortem phase and therefore warrant broader population testing to confirm their significance.

Figure 5.

PCA of VOCs from cadaveric blood at room temperature by sex. All shades of solid circles = male, All shades of solid triangles = female.

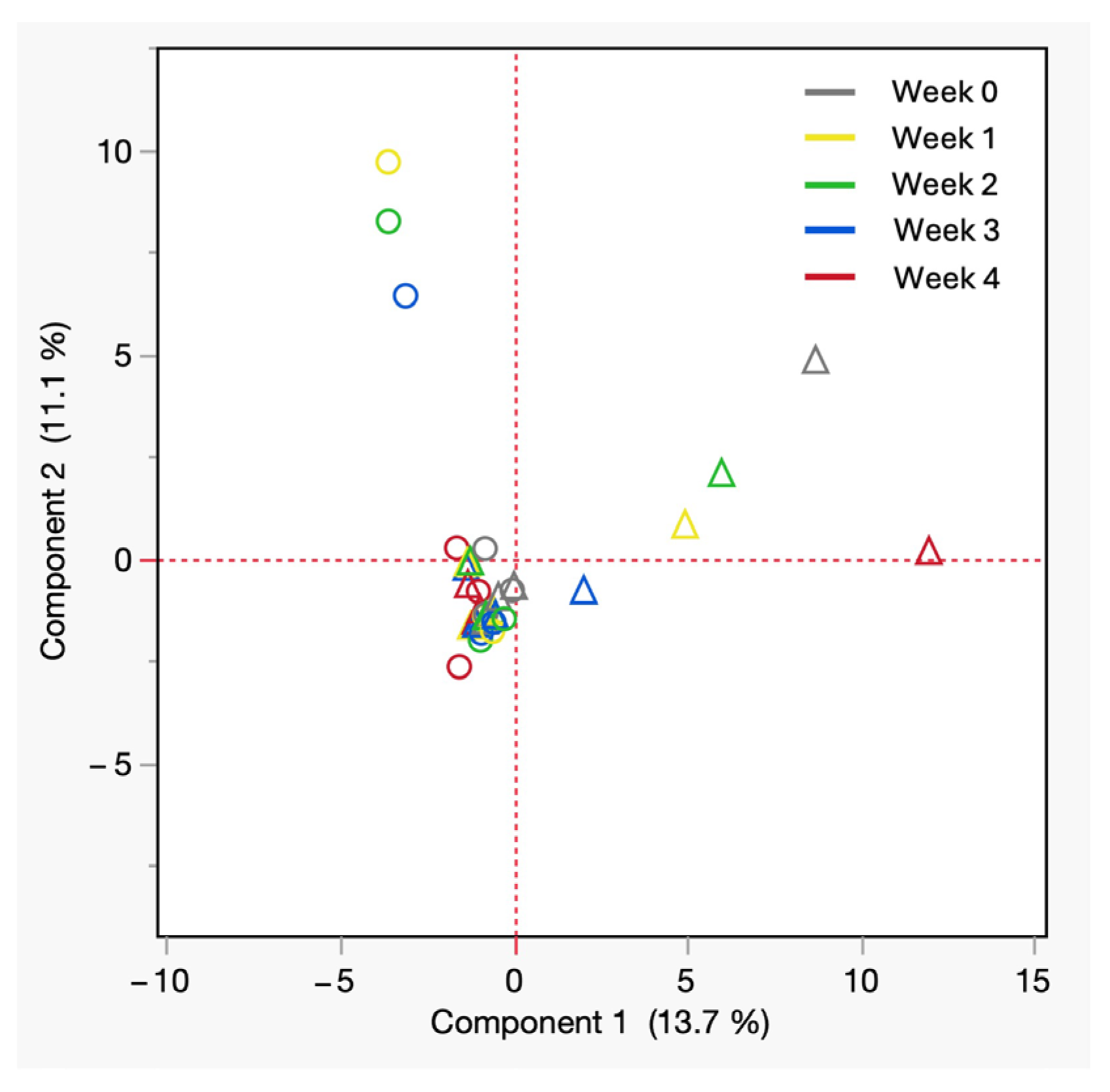

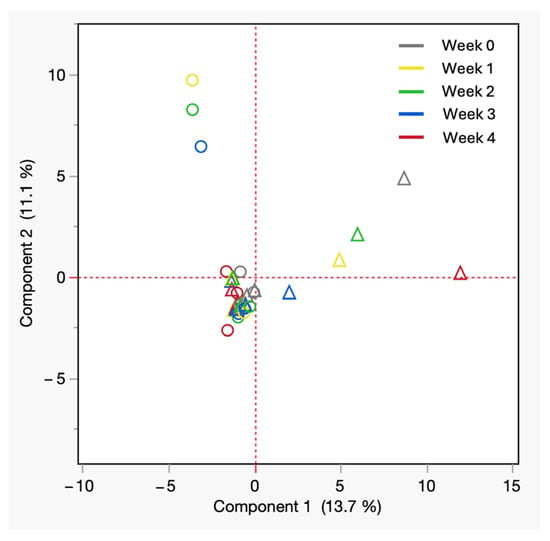

Figure 6 depicts the PCA plot of all postmortem blood samples under refrigerated conditions. The PCA plot highlights that principal component 1 had a variation of 13.7%, while principal component 2 had a variation of 11.1%, emphasizing the chemical odor profile patterns. Male samples were tightly clustered near the origin, suggesting a more uniform VOC composition regardless of storage week. In contrast, female samples displayed a broader spread along PC1, indicating greater chemical diversity in VOC profiles. It may indicate that female cadavers exhibit more variable and diverse blood VOC signatures. The clustering behavior supports the influence of sex on the biochemical trajectory of decomposition and highlights the need to consider sex as a biological variable in forensic odor profiling studies in the early postmortem stages.

Figure 6.

PCA of VOCs from refrigerated cadaveric blood samples by sex. All shades of hollow circles = male, All shades of hollow triangles = female.

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) Based on Postmortem Blood Collection Time (PBCT)

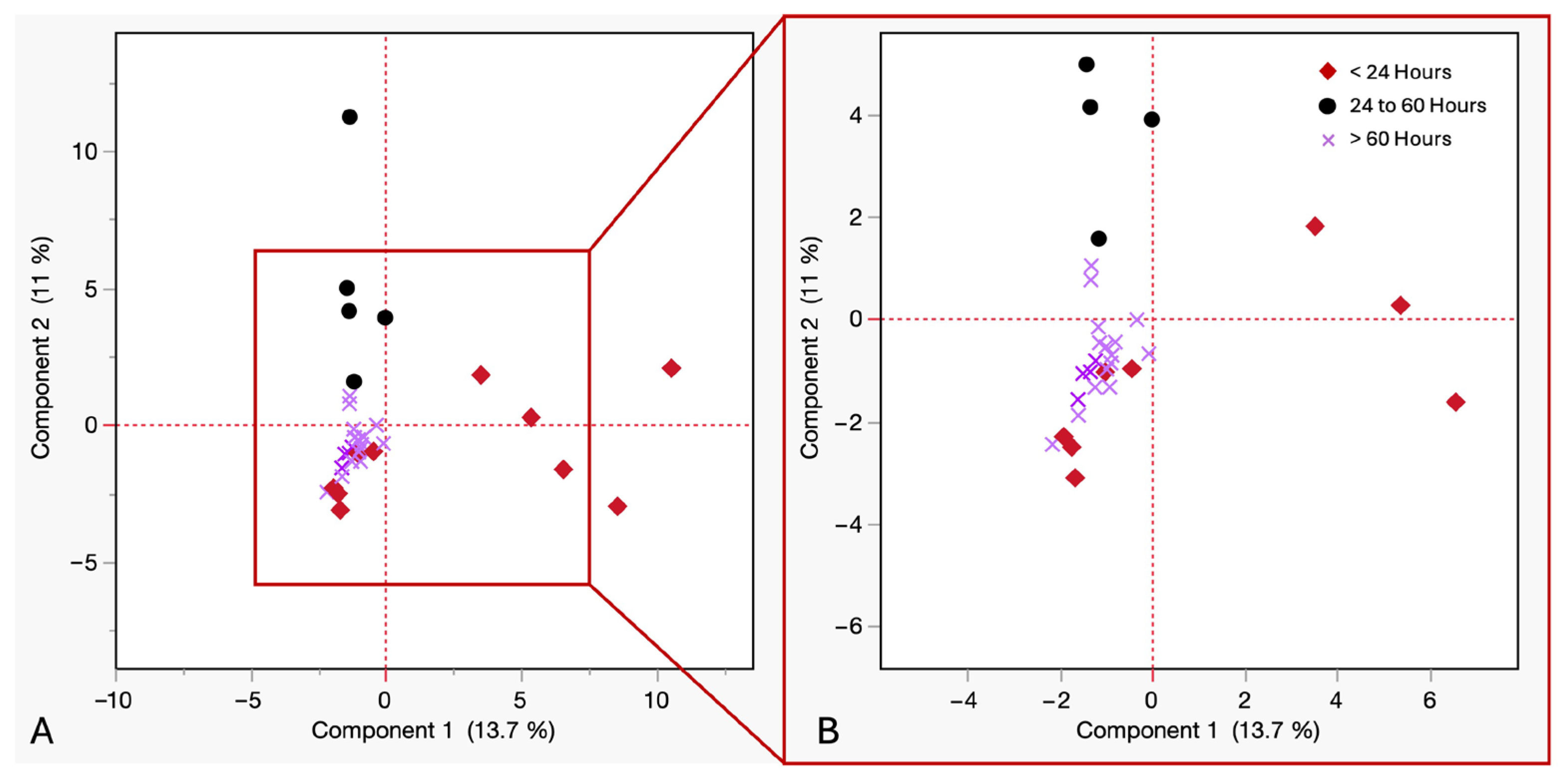

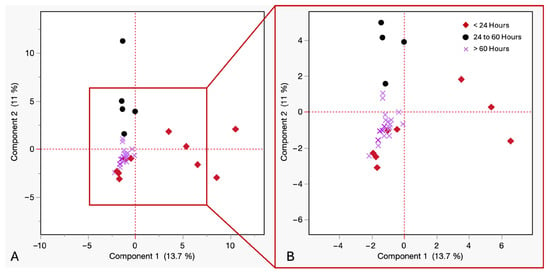

To assess the influence of postmortem blood collection time on the VOC profiles in cadaveric blood, a PCA was performed. Grouping samples by blood collection time since death helped identify temporal patterns and potential chemical markers associated with early postmortem phases. The samples were categorized into under 24 h, between 24 and 60 h, and over 60 h postmortem. As shown in Figure 7, The first two principal components explained 24.7% of the total variance (PC1 = 13.7%, PC2 = 11%). The samples collected within 24 h showed wide dispersion along PC1, indicating high VOC diversity and inter-individual variability. Samples collected between 24 and 60 h formed a dense cluster, indicating high chemical homogeneity and possible stabilization of metabolic by-products. Samples withdrawn after 60 h showed vertical but tighter dispersion along PC2, suggesting reduced variability in VOC odor profile. These clustering patterns suggest distinct intra-group and inter-group variance trends across PBCT categories. PCA scores plots revealed greater dispersion among blood samples at earlier postmortem time points, whereas later time points demonstrated tighter clustering, suggesting the emergence of a more consistent and common VOC pattern as postmortem timelines progressed.

Figure 7.

(A) PCA of VOCs in cadaveric blood samples by time of withdrawal postmortem at room temperature. Red diamonds ≤ 24 h, purple crosses = 24 to 60 h, black circles ≥ 60 h. (B) Close up view of squared in region.

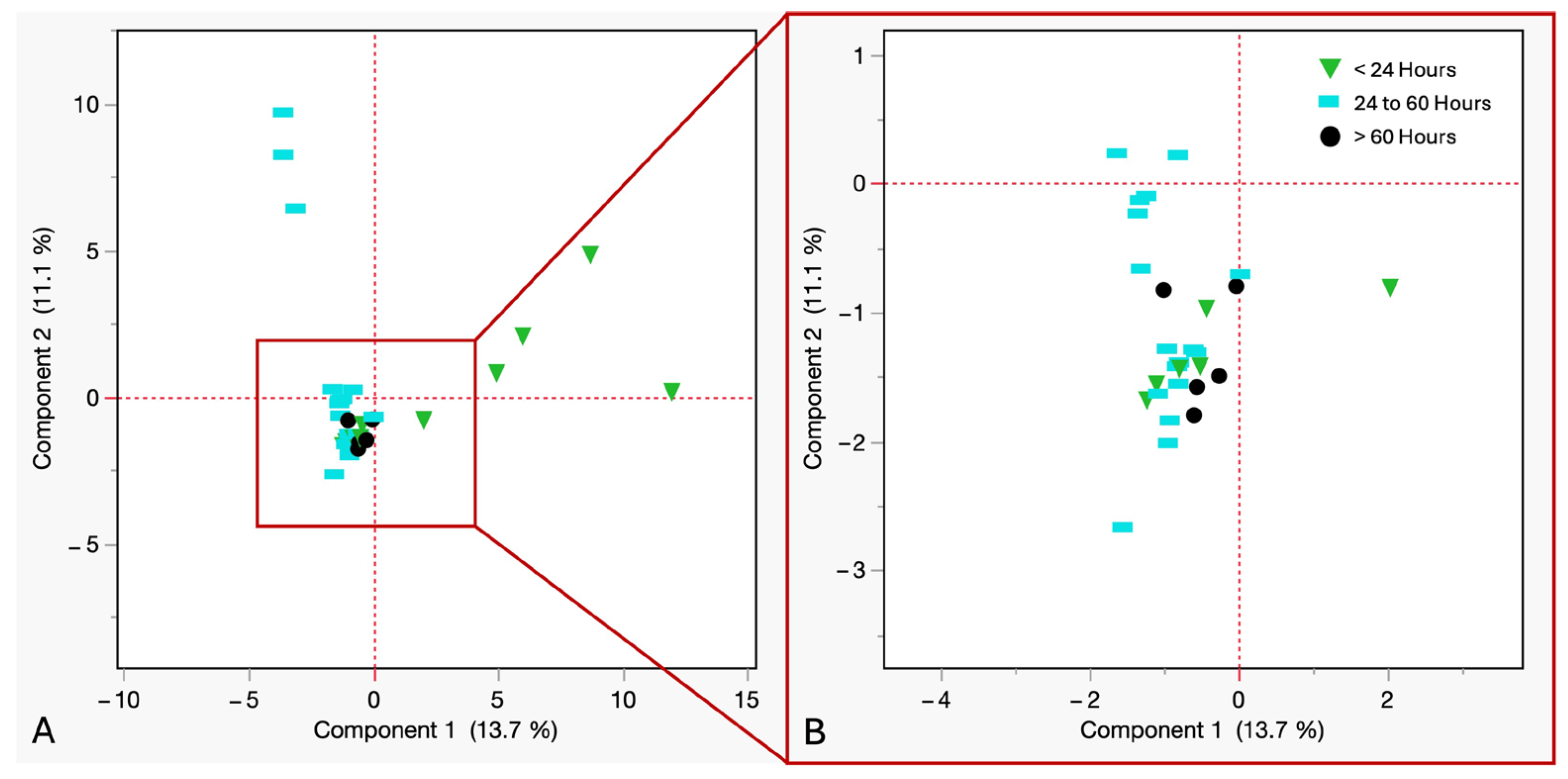

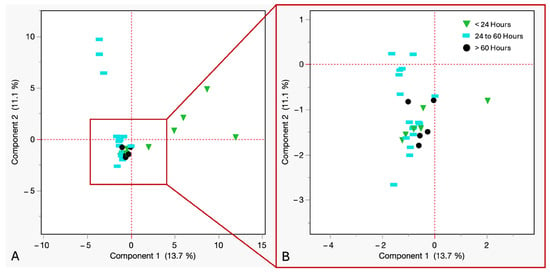

In Figure 8, PCA was performed to assess the impact of PBCT on VOCs in refrigerated cadaveric blood samples. The analysis revealed that the first two principal components explained 24.8% of the variance (PC1 = 13.7%, PC2 = 11.1%). The data showed a clear temporal structure, with samples withdrawn within 24 h showing the widest dispersion, indicating early-onset chemical activity and variation in VOC diversity. Samples withdrawn between 24 and 60 h postmortem showed variation in compound intensity, possibly due to microbial or enzymatic adaptation under refrigerated conditions. Samples withdrawn after 60 h showed homogeneity in VOC profiles and minimal compound evolution during late-stage cold storage.

Figure 8.

(A) PCA of VOCs from refrigerated cadaveric blood samples grouped by time of withdrawal. Downward green triangles ≤ 24 h, sky blue rectangles = 24 to 60 h, black circles ≥ 60 h. (B) Close up view of the coordinates.

Statistically, these results mirror patterns seen under room temperature but with notable shifts in variance and dispersion. The <24 h group maintains early chemical complexity even under refrigeration. The >60 h group shows VOC suppression and compositional uniformity, which confirms that refrigeration delays but does not eliminate temporal VOC evolution, with the blood draw time remaining a key differentiator in the volatilome profile.

Overall, the PCA findings demonstrate that time and temperature jointly modulate VOC complexity, with early-stage samples expressing the highest variability and late-stage samples exhibiting compositional convergence. These results support the hypothesis that blood odor signatures evolve in a temperature-dependent manner.

4. Discussion

This study provides novel insights into the volatile organic compound (VOC) signatures of cadaveric blood. Solid-phase micro-extraction (SPME) combined with gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC–MS) was used to characterize the volatile organic compounds (VOCs) released from postmortem blood of fresh cadavers. A four-week longitudinal analysis was then performed to evaluate blood odor signatures stored at room temperature and under refrigeration. The results demonstrate that blood VOC profiles change over time and that storage conditions significantly influence both the complexity and abundance of these compounds.

The baseline analysis of fresh cadaveric blood revealed a relatively simple VOC profile, dominated by alcohols, ketones, and low-molecular-weight hydrocarbons. This aligns with the literature by Hoffman et al. and Forbes et al. indicating the predominance of endogenous metabolic by-products in the early postmortem period [7,9]. Forbes et al. characterized VOCs released from living donor blood and found that fresh samples were dominated by 1-octen-3-ol, with ketones such as 2-heptanone, 3-octanone, and 2-nonanone emerging as the blood aged. Notably, they observed that aromatic hydrocarbons (toluene, ethylbenzene, xylene, styrene) arose only from samples stored in refrigerated or frozen conditions for 1–5 weeks [22].

Several VOCs were common to both the living donor blood profiled by Forbes et al. and the cadaveric blood analyzed in the present study, including 1-octen-3-ol, 2-ethyl-1-hexanol, 2-heptanone, 3-heptanone, 4-heptanone, 2-nonanone, 2-undecanone, hexanal, decanal, and mid-chain alkanes such as decane, dodecane, and tridecane [22]. These compounds represent conserved blood-derived VOCs that persist beyond death and therefore are not specific to postmortem change. In contrast, the cadaveric blood analyzed in the present study exhibited a substantially broader VOC signature, with the additional presence of sulfur compounds (dimethyl disulfide, dimethyl trisulfide), phenolic compounds (p-cresol, indole), unsaturated aldehydes (2-nonenal, 2,4-nonadienal, 2,4-decadienal), and high-molecular-weight hydrocarbons, none of which were reported in living donor blood. These compounds are consistent with microbial putrefaction [34], protein fermentation, lipid peroxidation, and cell membrane breakdown [35], and therefore represent chemically significant markers of postmortem blood [36].

As decomposition progressed, we observed a temporal increase in VOC diversity and intensity, particularly under room temperature storage. These profiles were enriched with aldehydes, nitrogenous compounds, and sulfur-containing VOCs—biomarkers of microbial degradation and protein catabolism [9,16]. Another recent study found a shift in blood VOC profiles from living donors, with fresh blood showing higher hydrocarbon levels and aged blood marked by increased aldehydes. Untrained dogs struggled to detect fresh samples but showed strong responses to aged blood [12]. This trend corroborates the theory that increased microbial activity under warmer conditions accelerates biochemical decomposition, enhancing odor complexity. In contrast, refrigerated samples exhibited suppressed VOC evolution, consistent with slower microbial and enzymatic activity at temperatures. These samples retained simpler profiles throughout the study, dominated by persistent ketones and fewer aldehydes. Such differences suggest that storage temperature significantly modulates the degradation kinetics of cadaveric blood.

The chemical changes observed also hold relevance for cadaver detection canine training. Several identified VOCs—including indole, aldehydes, and short-chain fatty acids—are known to influence canine olfactory responses [5,11]. Importantly, our findings suggest that dogs trained exclusively on fresh or refrigerated blood samples may lack sensitivity to decomposition-specific volatile organic compounds (VOCs) that are commonly encountered in real-world forensic scenarios. Crime scenes rarely involve freshly deposited blood; instead, blood evidence is often aged, environmentally exposed, or subjected to attempts at cleanup. As decomposition progresses, the VOC profile of blood becomes increasingly complex due to microbial activity and protein degradation, resulting in the emission of aldehydes, sulfur compounds, and other distinctive biomarkers. Therefore, incorporating VOC profiles from aged and decomposed blood into canine training aids is essential to better simulate operational conditions. This approach can enhance the dog’s ability to generalize across various postmortem intervals and environmental exposures, ultimately improving the accuracy and reliability of blood detection in forensic investigations.

This study enhances existing knowledge of blood decomposition by expanding the scale and depth of VOC analysis. Although the sample size is still modest and profiles are heterogeneous due to differences in health history and cause of death, inclusion of 16 cadavers represents a substantial advancement over prior studies with smaller sample sets. These data provide a broader exploratory basis for observing VOC trends, though inter-individual heterogeneity may affect the stability and interpretation of specific compound patterns. For example, Chilcote et al. examined how blood decomposes on different materials such as concrete and varnished wood, finding that the type of surface affected which compounds were released. Rust similarly looked at blood on porous and non-porous surfaces, showing that fresh blood gave off a different chemical profile than aged samples, and that the presence of certain compounds—like aldehydes or aromatics—varied depending on the material [8,10].

This research advances foundational knowledge by analyzing blood collected directly from human cadavers, rather than relying on samples taken from living individuals and subsequently left to decompose. While the latter model has been valuable in advancing research when cadaveric samples are unavailable, the direct use of postmortem blood provides a critical step toward understanding how the cessation of life influences the development of odor profiles. The results showed that ketones were among the most frequently observed compounds, increasing from 13 to 20 detections over four weeks under room temperature, and remaining stable under refrigeration. Hydroxyl aromatics also increased markedly in warmer conditions, from 2 to 14 detections, highlighting microbial activity. Sulfur-containing compounds, including methylthio derivatives, appeared more prominently in refrigerated samples during later weeks, suggesting slower but ongoing protein breakdown. Unlike earlier studies which emphasized surface-dependent changes, this study shows how environmental factors influence the VOC profile. Additionally, the use of replicate samples, temporal sampling, and cross-matrix comparison (e.g., comparing odor profiles from specimens and matched environmental controls) can help discriminate true biological indicators from exogenous contributions. By systematically applying these controls, the reliability of hydroxyl aromatics, ketones, and sulfur-based compounds as forensic indicators can be strengthened, supporting their targeted application in investigative contexts.

Because this study included postmortem blood samples from both biological sexes, statistical analysis was able to reveal sex-based differences in the resulting odor profiles—a novel insight from a postmortem perspective. Statistical analysis revealed sex-based differences, with females showing greater variability. While the underlying mechanisms may involve biological or hormonal factors, these observations are exploratory due to the small sample size and potential confounding; further studies with stricter controls are needed to confirm these effects.

Temporal PCA plots showed a clear trajectory of VOC evolution, with early-stage samples clustering near the origin and later-stage samples dispersing more widely—particularly under room temperature conditions. Refrigeration delayed this divergence, reflecting slower decomposition processes.

PBCT PCA further demonstrated that VOC diversity was highest in samples withdrawn within 24 h postmortem, because of quick early postmortem changes. Samples collected between 24 and 60 h clustered tightly, showing temporary chemical stabilization, while samples over 60 h showed increased variability driven mainly by differences in compound intensity. The same pattern was observed under refrigeration with reduced overall dispersion, confirming that lower temperature delays but does not halt time-dependent VOC evolution.

While the study provided novel perspectives on postmortem blood odor analysis, there are intrinsic challenges with this type of analytical work. Factors like age, health, medical history, and cause of death created heterogeneous profiles. External contaminants and substrate effects also contributed to variability. A key limitation of this storage study is that, unlike operational training aids, the blood samples were not opened to the environment during weekly analyses. This condition differs substantially from canine deployments, where repeated handling, freeze–thaw cycles, and environmental exposure can alter odor availability. Despite this constraint, the study offers important implications by identifying compound types and abundances relevant to canine perception when blood is used as a target odor. Moreover, the observed sex-based differences in postmortem blood profiles suggest a novel forensic application, with potential utility in the interpretation of blood traces.

Demographic factors such as age and sex warrant consideration, as they may influence VOC patterns and degradation rates. Greater diversity in cadaver sources would strengthen the reliability of such comparisons.

Environmental variables—including temperature, humidity, and microbial activity—also merit systematic investigation, given their strong influence on decomposition dynamics. The first 24 h provides candidate chemical features and time window clues that may inform future postmortem interval modeling. Additionally, sex-based differences in VOC release patterns should be explored, as these may provide further refinement in determining time since death. Collectively, these directions emphasize the need for broader sampling, controlled environmental studies, and early-stage analyses to enhance the forensic applicability of VOC profiling.

5. Conclusions

The objectives of this study were to (1) evaluate the headspace odor signature from cadaveric blood from freshly deceased individuals and (2) monitor the stability of the chemical odor profile from cadaveric blood over a 4-week period under two environmental storage conditions, room temperature and refrigeration, while also examining the effects of donor biological sex and the timing of blood withdrawal postmortem.

The results showed that volatile organic compounds (VOCs) from cadaveric blood provide valuable insights into decomposition dynamics and postmortem blood collection time (PBCT). Ketones, hydroxyl aromatics, and sulfur compounds were consistently identified as reliable markers, with room temperature accelerating VOC release and refrigeration delaying but not preventing their evolution. PCA revealed that VOC patterns are influenced by sex, PMI, and storage conditions, with postmortem collection time having a stronger effect than storage environment. These findings highlight the need to incorporate diverse VOC profiles into forensic applications. For example, canine training should include odor profiles spanning multiple PMIs rather than relying solely on training aids generated under controlled conditions, thereby improving generalization and real-world performance. Future research should compare blood VOCs from a wider range of human cadaver demographics, expand demographic representation, and focus on early postmortem phases to refine PMI estimation and deepen understanding of blood degradation pathways. Collectively, this work advances forensic science by clarifying the temporal and environmental influences on cadaveric VOCs and by underscoring their potential in improving investigative and field detection methodologies.

Author Contributions

Methodology, formal analysis, investigation, data curation, writing—original draft preparation, L.R.; resources, supervision, R.J.; resources, supervision, K.K.G.; conceptualization, resources, methodology, supervision, project administration, writing—review and editing, P.A.P.-T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the TTUHSC Institutional Anatomical Review Committee (IARC) with approved protocol IARC# 23-0721R on 21 July 2023.

Informed Consent Statement

Blood specimens were obtained from willed body donors who provided prior informed consent to the Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center (TTUHSC) Willed Body Program (WBP), which is certified by the Texas Funeral Service Commission for education, training, and research purposes, under the State of Texas Health and Safety Code, Chapters 691 and 692A. Only first-person or next-of-kin authorized donations are accepted. The TTUHSC Institutional Anatomical Review Committee (IARC) reviewed and approved this research involving blood samples from cadaveric donors, ensuring ethical and regulatory compliance with State Law and University Operating Policy, 73.20.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors extend their deepest gratitude to the unselfish men, women, and family members who donate their bodies to the Institute of Anatomical Sciences, Willed Body Program at Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center for educational and research purposes. Without their contribution, studies like this one would not be possible. The authors thank the Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center and the School of Health Professions’ Center for Rehabilitation Research and Institute of Anatomical Sciences for the use of the Clinical Anatomy Research Laboratory. The authors also thank Deanna Wise, Kelsey Patschke, and Jason C. Jones, Willed Body Program Director, for their assistance during this project.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Murder Accountability Project©. Murder Accountability Project. Available online: https://www.murderdata.org/ (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Zailani, N.N.B.; Ho, P.C.-L. Dried Blood Spots—A Platform for Therapeutic Drug Monitoring (TDM) and Drug/Disease Response Monitoring (DRM). Eur. J. Drug Metab. Pharmacokinet. 2023, 48, 467–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meikopoulos, T.; Gika, H.; Theodoridis, G.; Begou, O. Detection of 26 Drugs of Abuse and Metabolites in Quantitative Dried Blood Spots by Liquid Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry. Molecules 2024, 29, 975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hegde, C.; Shekhar, R.; Paul, P.M.; Pathak, C. A review on forensic analysis of bio fluids (blood, semen, vaginal fluid, menstrual blood, urine, saliva): Spectroscopic and non-spectroscopic technique. Forensic Sci. Int. 2025, 367, 112343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bukyya, J.L.; Tejasvi, M.L.A.; Avinash, A.; Chanchala, H.P.; Talwade, P.; Afroz, M.M.; Pokala, A.; Neela, P.K.; Shyamilee, T.K.; Srisha, V. DNA Profiling in Forensic Science: A Review. Glob. Med. Genet. 2021, 8, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacco, M.A.; Gualtieri, S.; Princi, A.; Raffaele, R.; Aquila, I. Application of bloodstain pattern analysis (BPA) to reconstruct a staged crime scene in a complex forensic case. Forensic Sci. Int. Synerg. 2025, 11, 100624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pokupcic, K. Blood as an Important Tool in Criminal Investigation. J. Forensic Sci. Crim. Investig. 2017, 3, 555615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drabińska, N.; Flynn, C.; Ratcliffe, N.; Belluomo, I.; Myridakis, A.; Gould, O.; Fois, M.; Smart, A.; Devine, T.; Costello, B.P.J.d.L. A literature survey of all volatiles from healthy human breath and bodily fluids: The human volatilome. J. Breath. Res. 2021, 15, 034001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, N.; Krishnan, P.; Rees, C.A.; Zhang, M.; Stevenson, K.A.J.M.; Hill, J.E. Profiling volatile organic compounds from human plasma using GC × GC-ToFMS. J. Breath Res. 2023, 17, 037104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vass, A.A. Odor mortis. Forensic Sci. Int. 2012, 222, 234–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubois, L.M.; Stefanuto, P.-H.; Heudt, L.; Focant, J.-F.; Perrault, K.A. Characterizing decomposition odor from soil and adipocere samples at a death scene using HS-SPME-GC×GC-HRTOFMS. Forensic Chem. 2018, 8, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, E.M.; Curran, A.M.; Dulgerian, N.; Stockham, R.A.; Eckenrode, B.A. Characterization of the volatile organic compounds present in the headspace of decomposing human remains. Forensic Sci. Int. 2009, 186, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosier, E.; Loix, S.; Develter, W.; Van De Voorde, W.; Tytgat, J.; Cuypers, E. The Search for a Volatile Human Specific Marker in the Decomposition Process. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0137341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosier, E.; Loix, S.; Develter, W.; Van De Voorde, W.; Tytgat, J.; Cuypers, E. Time-dependent VOC-profile of decomposed human and animal remains in laboratory environment. Forensic Sci. Int. 2016, 266, 164–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buis, R.; Rust, L.; Nizio, K.; Rai, T.; Stuart, B.; Forbes, S. Investigating the Sensitivity of Cadaver-Detection Dogs to Decomposition Fluid. J. Forensic Identif. 2015, 65, 985–997. [Google Scholar]

- Verheggen, F.; Perrault, K.A.; Megido, R.C.; Dubois, L.M.; Francis, F.; Haubruge, E.; Forbes, S.L.; Focant, J.-F.; Stefanuto, P.-H. The Odor of Death: An Overview of Current Knowledge on Characterization and Applications. BioScience 2017, 67, 600–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deo, A.; Forbes, S.L.; Stuart, B.H.; Ueland, M. Profiling the seasonal variability of decomposition odour from human remains in a temperate Australian environment. Aust. J. Forensic Sci. 2020, 52, 654–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeBruyn, J.M.; Hoeland, K.M.; Taylor, L.S.; Stevens, J.D.; Moats, M.A.; Bandopadhyay, S.; Dearth, S.P.; Castro, H.F.; Hewitt, K.K.; Campagna, S.R.; et al. Comparative Decomposition of Humans and Pigs: Soil Biogeochemistry, Microbial Activity and Metabolomic Profiles. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 608856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, D.; Dargan, R.; Burr, W.S.; Daoust, B.; Forbes, S. Identifying the Early Post-Mortem VOC Profile from Cadavers in a Morgue Environment Using Comprehensive Two-Dimensional Gas Chromatography. Separations 2023, 10, 566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dargan, R.; Forbes, S.L. Cadaver-detection dogs: A review of their capabilities and the volatile organic compound profile of their associated training aids. WIREs Forensic Sci. 2021, 3, e1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, A.; Lamb, E.; Deo, A.; Pasin, D.; Liu, T.; Zhang, W.; Su, S.; Ueland, M. The use of novel electronic nose technology to locate missing persons for criminal investigations. iScience 2023, 26, 106353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forbes, S.L.; Rust, L.; Trebilcock, K.; Perrault, K.A.; McGrath, L.T. Effect of age and storage conditions on the volatile organic compound profile of blood. Forensic Sci. Med. Pathol. 2014, 10, 570–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeGreeff, L.E.; Schultz, C.A. (Eds.) Canines: The Original Biosensors; Jenny Stanford Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Passe, D.H.; Walker, J.C. Odor psychophysics in vertebrates. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 1985, 9, 431–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riezzo, I.; Neri, M.; Rendine, M.; Bellifemina, A.; Cantatore, S.; Fiore, C.; Turillazzi, E. Cadaver dogs: Unscientific myth or reliable biological devices? Forensic Sci. Int. 2014, 244, 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rendine, M.; Fiore, C.; Bertozzi, G.; De Carlo, D.; Filetti, V.; Fortarezza, P.; Riezzo, I. Decomposing Human Blood: Canine Detection Odor Signature and Volatile Organic Compounds. J. Forensic Sci. 2019, 64, 587–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sloane, C.F. Dogs in War, Police Work and on Patrol. J. Crim. Law Criminol. Police Sci. 1955, 46, 385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chilcote, B.; Rust, L.; Nizio, K.D.; Forbes, S.L. Profiling the scent of weathered training aids for blood-detection dogs. Sci. Justice 2018, 58, 98–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rust, L.; Nizio, K.D.; Forbes, S.L. The influence of ageing and surface type on the odour profile of blood-detection dog training aids. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2016, 408, 6349–6360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rust, L.; Nizio, K.D.; Wand, M.P.; Forbes, S.L. Investigating the detection limits of scent-detection dogs to residual blood odour on clothing. Forensic Chem. 2018, 9, 62–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whaley, F.; Albizu, V.; Cruz, J.; Dargan, R.; DeGreeff, L. Investigation of Distinct Odor Profiles of Blood over Time Using Chemometrics and Detection Canine Response. Chemosensors 2025, 13, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pojmanová, P.; Ladislavová, N.; Škeříková, V.; Kukal, J.; Urban, Š. Sex Differentiation from Human Scent Chemical Analysis. Separations 2023, 10, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frazier, C.J.G.; Gokool, V.A.; Holness, H.K.; Mills, D.K.; Furton, K.G. Multivariate regression modelling for gender prediction using volatile organic compounds from hand odor profiles via HS-SPME-GC-MS. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0286452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paczkowski, S.; Schütz, S. Post-mortem volatiles of vertebrate tissue. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2011, 91, 917–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Statheropoulos, M.; Spiliopoulou, C.; Agapiou, A. A study of volatile organic compounds evolved from the decaying human body. Forensic Sci. Int. 2005, 153, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schieweck, A.; Schulz, N.; Amendt, J.; Birngruber, C.; Holz, F. Catch me if you can—Emission patterns of human bodies in relation to postmortem changes. Int. J. Leg. Med. 2024, 138, 1603–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.