Abstract

The highly efficient performance of photoelectrochemical (PEC) water splitting is largely governed by the construction of active interfaces, especially for the star semiconductor/electrocatalyst system. However, traditional strategies struggle to optimize this critical process. To overcome this challenge, we report a fluorine (F) engineering strategy that enables the synchronous modulation of charge transfer and surface catalytic reaction dynamics in a BiVO4/FeCoOOH-integrated photoanode. Various characterization methods confirm that F engineering can activate the BiVO4/FeCoOOH/electrolyte interfaces. Benefiting from these positive effects, the optimized BiVO4/FeCoOOH-F photoanode achieves a relatively high photocurrent density of 5.46 mA/cm2 at 1.23 V vs. RHE, along with outstanding photostability and a small Tafel slope of 96.5 mV dec−1. This study provides new insights into F-based interface manipulation, offering a promising route to developing high-performance semiconductor/electrocatalyst systems for efficient and stable PEC water splitting applications.

1. Introduction

Photoelectrochemical (PEC) water splitting has emerged as a compelling carbon-free technology for the sustainable conversion of solar energy into clean hydrogen fuel. To date, several promising semiconductor materials, such as WO3 [1,2], Fe2O3 [3,4,5,6], Ta3N5 [7,8], and BiVO4 [9,10,11,12,13,14], have attracted significant attention as photoanode candidates for solar-driven water splitting. Among these diverse candidates, BiVO4 stands out as a promising photoanode for PEC water splitting, benefiting from its narrow band gap (ca. 2.4 eV), well-aligned valence band position, and cost-effective raw materials [15,16,17,18]. Nevertheless, the PEC water splitting efficiency of pristine BiVO4 photoanodes is severely affected by the recombination of photogenerated electron–hole pairs and sluggish oxygen evolution reaction (OER) kinetics [19].

To overcome this obstacle, numerous strategies have been proposed to enhance the performance of BiVO4 (BV) photoelectrodes, including cocatalyst loading [20,21], elemental doping [22], and constructing heterojunctions [23]. Among these approaches, coating oxygen evolution catalysts (OECs) on semiconductors (SCs) is a preferred strategy, given its ability to lower the overpotential associated with water oxidation [24,25,26,27,28]. Herein, electrocatalysts based on transition-metal oxyhydroxides (TMOOHs) have re-emerged as a research hotspot in recent years, driven by their superior catalytic performance and prominent cost advantages. For example, Choi et al. [29] confirmed that the loading of FeOOH/NiOOH onto BiVO4 photoelectrodes can achieve a remarkable photocurrent density of 4.5 mA/cm2 at 1.23 V vs. RHE. As reported by Zhang et al., [28] a simple solution impregnation method was employed to prepare BV/FeOOH photoelectrodes, which finally delivered a respectable photocurrent density of 4.3 mA/cm2 at 1.23 V vs. RHE. Recently, Ning’s group found that loading FeNiOOH onto the BV surface enabled a significantly enhanced photocurrent density of up to 4.37 mA/cm2 at the same potential [22]. Nevertheless, the PEC performance of the reported OEC-decorated photoanodes remains unsatisfactory, particularly with regard to their photocurrent densities, which typically fall within the range of 4.5–6.0 mA/cm2 [30].

Therefore, a key obstacle that cannot be overlooked is the inevitable emergence of interfacial charge recombination centers at the newly formed SC/TMOOH interface. To address these shortcomings, more researchers have focused their attention on interfacial engineering strategies. As a representative case, Zhang et al. [31] demonstrated that inserting an exfoliated phosphorene layer at the interface between BiVO4 and NiOOH could drastically promote the extraction of photogenerated holes, thereby achieving an improved photocurrent density of 4.48 mA/cm2. In addition, our research group previously incorporated porphyrin molecules into the BiVO4/OEC system to facilitate the rapid transfer of photogenerated holes, thus realizing efficient interfacial charge separation [32]. Regrettably, the desired photocurrent density has yet to be achieved, which can be mainly attributed to two key limitations: (i) these interlayers exhibit sluggish hole transfer kinetics and cannot rapidly transport photogenerated charge carriers away from the interface; (ii) mismatched energy bands and interfacial defects at the newly formed interface can still induce the formation of new charge recombination centers. Therefore, selecting a suitable SC/TMOOH integrated system, constructing as few interfaces as possible, and rationally optimizing the SC/TMOOH/electrolyte interface are urgent priorities for further enhancing the performance of such photoanodes.

Previous reports indicate that the incorporation of a heteroatoms (i.e., Fe and Ni) can separately influence charge separation and surface OER activity [33,34]. Motivated by this, doping the electrocatalyst layer with highly electronegative F [34,35], which modulates the local microenvironment of TMOOH, could address the aforementioned bottlenecks (activation of SC/TMOOH/electrolyte interface) and achieve the desired water splitting performance. However, the design of a generalized strategy for the concurrent optimization of these two interfaces remains a highly challenging endeavor.

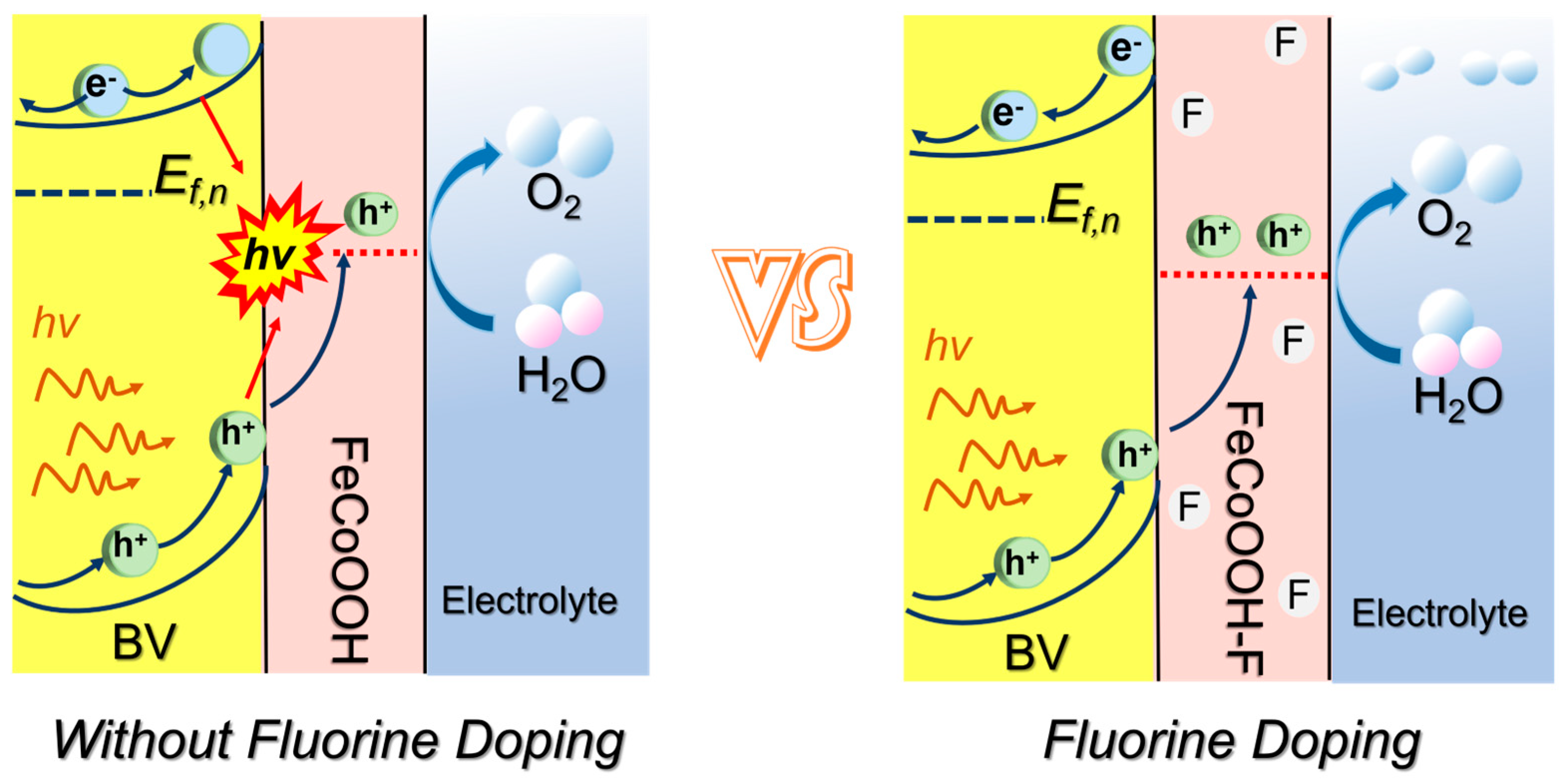

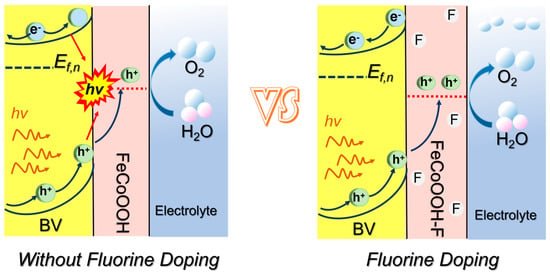

Herein, a smart strategy is proposed to construct the excepted BV/FeCoOOH-F photoanode via F engineering. Notably, the incorporation of the F element led to a remarkable improvement in charge transfer dynamics and surface catalytic kinetics (Scheme 1). Through extensive electrochemical characterization, we concluded that the introduction of F can exhibit a positive effect on enhancing surface catalytic activity and suppressing interfacial charge recombination. Ultimately, the photocurrent density was significantly enhanced, reaching approximately 5.46 mA/cm2, accompanied by excellent photostability.

Scheme 1.

Diagram of designed photoanode and charge transfer process.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemical Reagents and Instruments

Bi(NO3)3·5H2O (98.0%), VO(acac)2 (98%), p-benzoquinone (98.0%), acetone (AR), isopropyl alcohol (AR), ethanol (AR) and HNO3 (AR) were purchased from Energy Chemical (Shanghai, China). KI (AR), Co(NO3)2·6H2O (AR) and FeSO4·7H2O (AR) were obtained from Shanghai Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co. Ltd (Shanghai, China). Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, 99.5%) was purchased from GL Biochem (Shanghai, China). All experiments were conducted using ultrapure water (18.25 MΩ·cm at 25 °C) from a Milli-Q system (Shanghai, China). F-doped tin oxide (FTO) conductive glass was ultrasonically cleaned sequentially with acetone, ethanol, isopropyl alcohol and deionized water.

2.2. Materials Preparation

2.2.1. Preparation of BV Films

First, 3.32 g of KI was dissolved in 50 mL of H2O under stirring. Then, 0.97 g of Bi(NO3)3·5H2O was slowly added to the solution. Subsequently, concentrated HNO3 was added to the above solution to adjust the pH to 1.7. This solution was then slowly dripped into a p-benzoquinone-absolute ethanol solution and stirred for 4~5 min to obtain the precursor solution for BiOI deposition.

Second, a three-electrode system was assembled for electrodeposition, with FTO as the working electrode, an Ag/AgCl electrode as the reference electrode, and a platinum sheet as the counter electrode. The deposition of BiOI films was performed at a voltage of −0.10 V vs. Ag/AgCl for 300 s.

After deposition, a VO(acac)2 solution in DMSO was dripped onto the BiOI films, which were then calcined in a muffle furnace (450 °C for 2 h). Finally, the calcined electrodes were immersed in an alkaline solution for 30 min to remove excess V2O5, yielding BV. The electrodes were rinsed with distilled water and dried.

2.2.2. Preparation of BV/FeCoOOH

The FeCoOOH electrocatalyst was loaded onto BV sample via a photoelectrodeposition approach. Typically, a precursor solution containing 50 mM FeSO4·7H2O and 50 mM Co(NO3)2·6H2O was prepared. A three-electrode system was used for constant-potential deposition at 0.20 V vs. Ag/AgCl for 1200 s, with BV serving as the working electrode under illumination. Finally, the obtained samples were rinsed with distilled water and dried in air at room temperature to obtain the targeted photoanode.

2.2.3. Preparation of BV/FeCoOOH-F

Subsequently, the obtained BV/FeCoOOH-F electrode was immersed in an NH4F solution (0.5 M) for 7 min to obtain the BV/FeCoOOH-F photoanode.

2.3. Structural Characterization

The morphology of the photoanode was characterized using field emission scanning electron microscopy (SEM, SU8020, Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan). The crystal structure of different samples was measured by powder X-ray diffraction (XRD, SmartLab 9 KW, Rigaku, Tokyo, Japan). Raman spectra were investigated using a microscopic confocal laser Raman spectrometer (Renishaw plc, Wotton-under-Edge, UK). Fluorescence spectra were acquired with an FL 8500 fluorescence spectrophotometer (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA). The optical properties of different photoanodes were characterized via ultraviolet–visible (UV–vis) absorption spectroscopy (Shimadzu UV-3600, Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan). The chemical states and compositions were determined via X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS, Escalab Xi+, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

2.4. Electrochemical and Photoelectrochemical (PEC) Measurements

The electrochemical and PEC properties of different samples were tested using an electrochemical workstation (CHI760E, Chenhua Instrument Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China). Simulated AM 1.5 G solar illumination at a light intensity of 100 mW/cm2 was achieved by equipping a 300 W xenon arc lamp (PLS-SXE300D, Beijing Perfectlight Technology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China) with a dedicated AM 1.5 G filter. The conversion between the potential of the Ag/AgCl reference electrode the potential relative to the reversible hydrogen electrode (vs. RHE) can be achieved using the following equation:

E(RHE) = E(Ag/AgCl) + 0.197 + 0.0591 pH.

The applied bias photon-to-current efficiency (ABPE) was calculated by using the following equation:

where and are the photocurrent density (mA/cm2) in the light and dark, respectively. Vapp is the applied potential (vs. RHE), and Plight is the power intensity of AM 1.5 G (100 mW/cm2). Additionally, electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) measurements were conducted using the Autolab M204 electrochemical workstation (10 KHz to 0.1 Hz) (Metrohm Autolab B.V., Utrecht, The Netherlands).

The intensity-modulated photocurrent spectroscopy (IMPS) and transient photocurrent response (i-t) were also performed using a photoechem system (LED, 470 nm, Metrohm Autolab B.V., Utrecht, The Netherlands), Autolab M204. Typically, the frequency at which the maximum imaginary part occurs equals the sum of the Kct and the Krc, following the relationship Krc + Kct = 2πf. The ratio Kct/(Krc + Kct) can be determined by comparing the steady-state photocurrent with the instantaneous photocurrent. As a result, the key parameters Kct and Krc are easily obtainable.

The charge separation efficiency () and injection efficiency () of BV/FeCoOOH-F and BV were obtained using the following equation:

and are the photocurrent density obtained in a K3BO3 electrolyte (pH 9.5) without or with Na2SO3, respectively. represents theoretical current density.

An online gas chromatograph (GC, Fuli, 9790II, Taizhou, China) is employed to quantify hydrogen and oxygen gases from PEC water splitting.

3. Results and Discussion

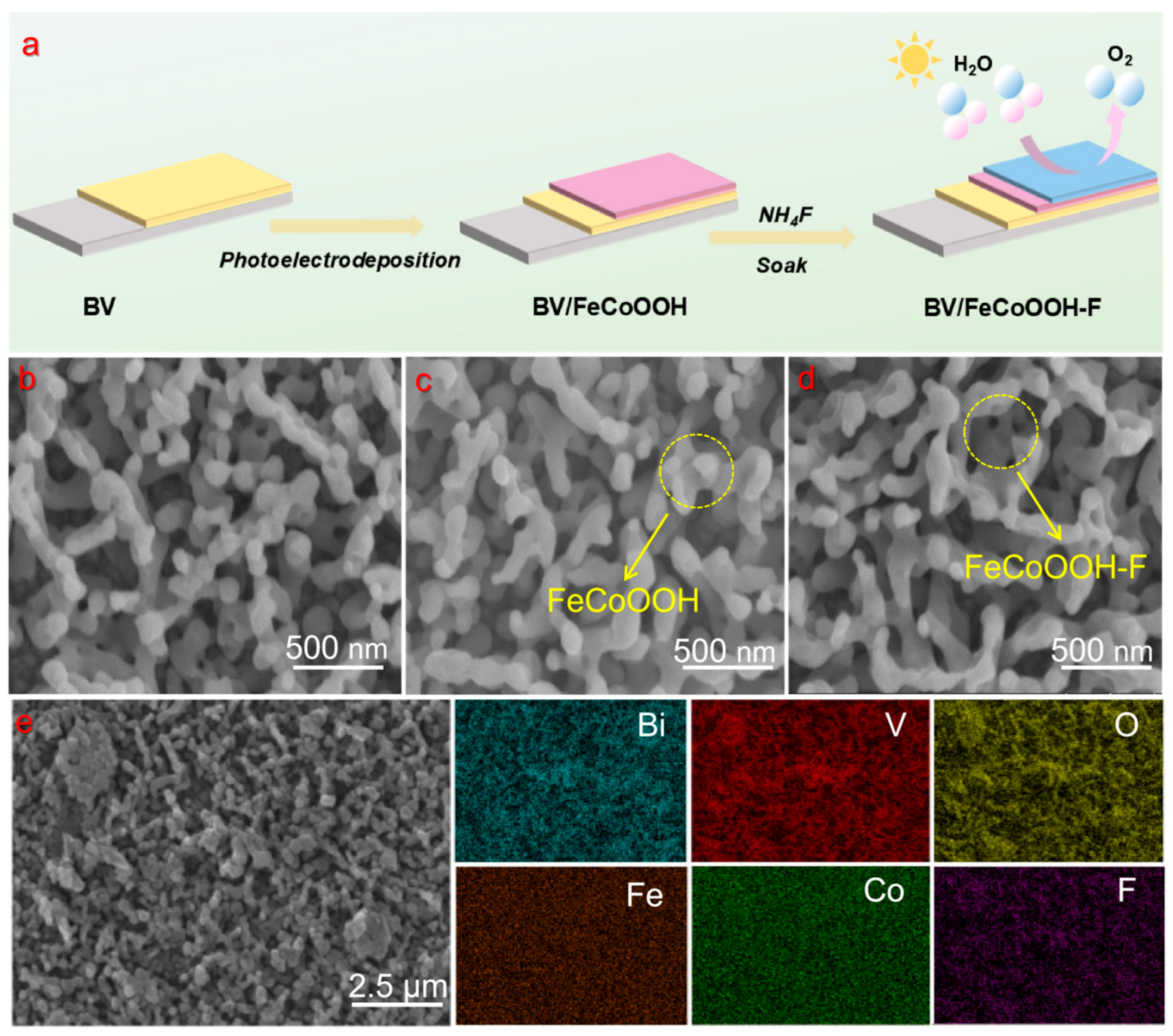

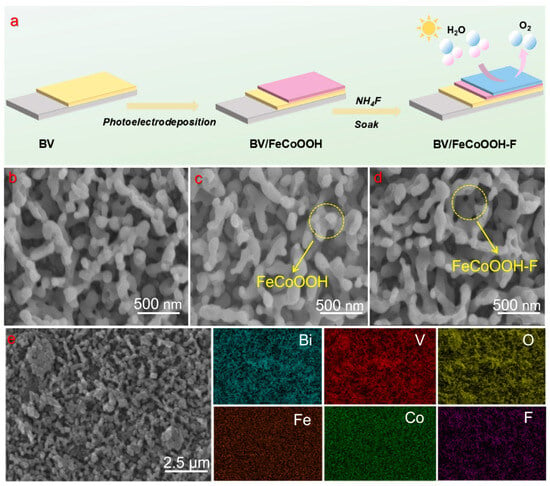

Figure 1a shows the preparation process of the integrated photoanode. First, SEM was employed to investigate the morphology and microstructure of the BV-based photoanodes. As shown in Figure 1b, the BV is uniformly loaded on the FTO surface, clearly exhibiting a worm-like porous structure with a diameter of 100–300 nm. The crystal structures of different samples were characterized by XRD. In Figure S1, the BV film exhibits a monoclinic structure (JCPDS No. 14-0688), and its characteristic diffraction peaks are consistent with the reported literature [23,32]. Combined with the Raman spectroscopy results (Figure S2), which show characteristic peaks at 210.0, 314.0, 366.0, 640.0, 710.0, and 826.0 cm−1, it can be confirmed that BV was successfully prepared.

Figure 1.

(a) Schematic illustration of the preparation procedure for BV/FeCoOOH-F; (b–d) SEM image of BV, BV/FeCoOOH and BV/FeCoOOH-F, respectively; (e) energy-dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) elemental mapping.

We loaded the electrocatalyst FeCoOOH and FeCoOOH-F onto BV by means of photoelectrodeposition and the immersion method, respectively. SEM characterization revealed that a layer of fluffy substance clearly adhered to the BV surface (Figure 1c,d), and the similar structure further indicated that the FeCoOOH layer and the F doping have a slight influence on the BV arrays. Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) tests (Figure 1e) were conducted on the samples, and the characteristic signals of elements, including Bi, V, O, Fe, Co and F, could be clearly observed. Moreover, we performed x-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) measurements and found that a distinct F 1s peak could be observed at 683.8 eV (Figure S3), verifying the successful synthesis of F-doped FeCoOOH, which is consistent with the EDS results. These findings proved that the BV/FeCoOOH-F photoanode had been fabricated. Meanwhile, the test results from XRD (Figure S1) and Raman (Figure S2) show that, compared with BV, BV/FeCoOOH and BV/FeCoOOH-F do not exhibit obvious characteristic absorption peaks, which suggests its low loading amount, extremely thin thickness, and uniform distribution of the FeCoOOH-F layer.

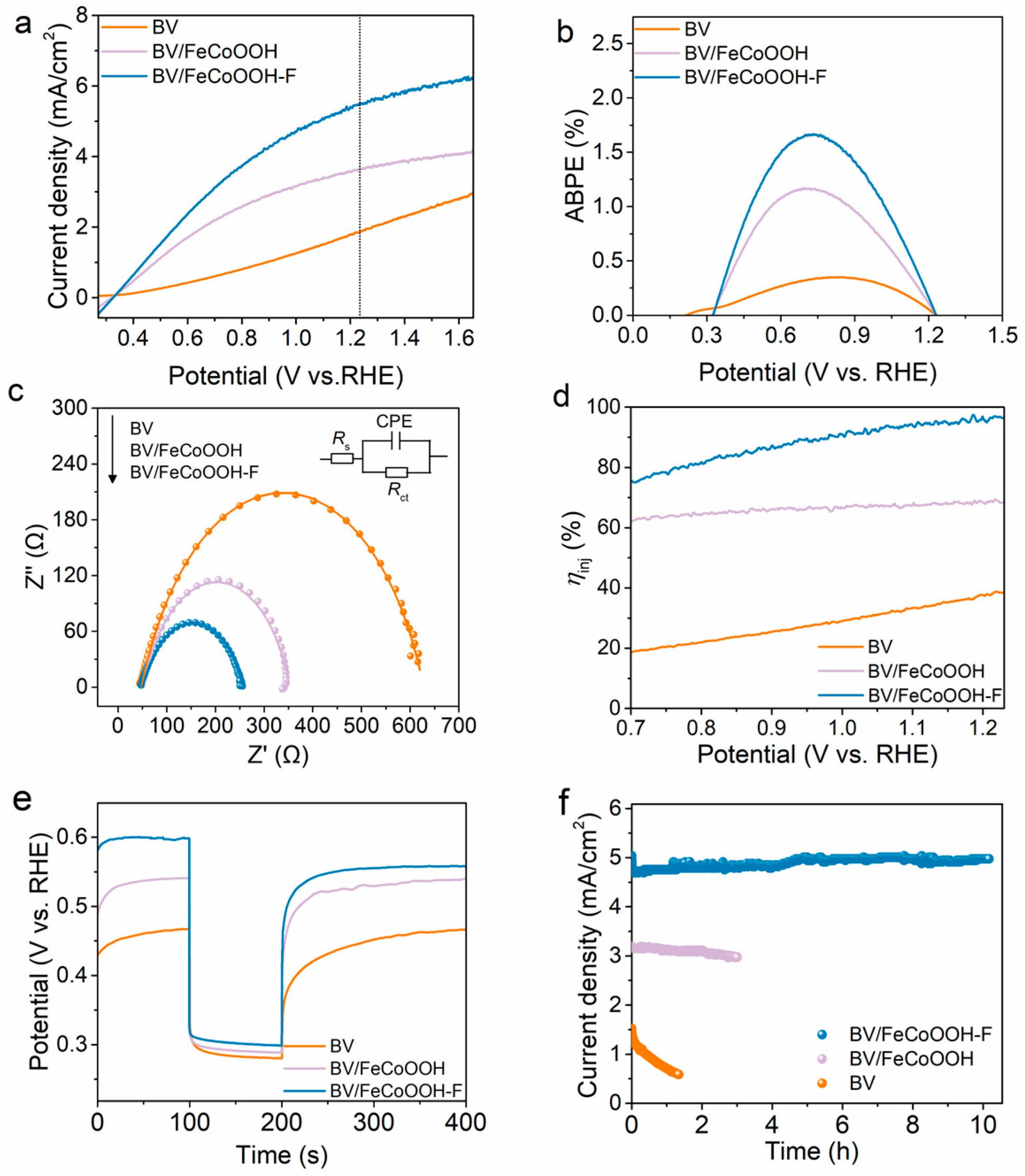

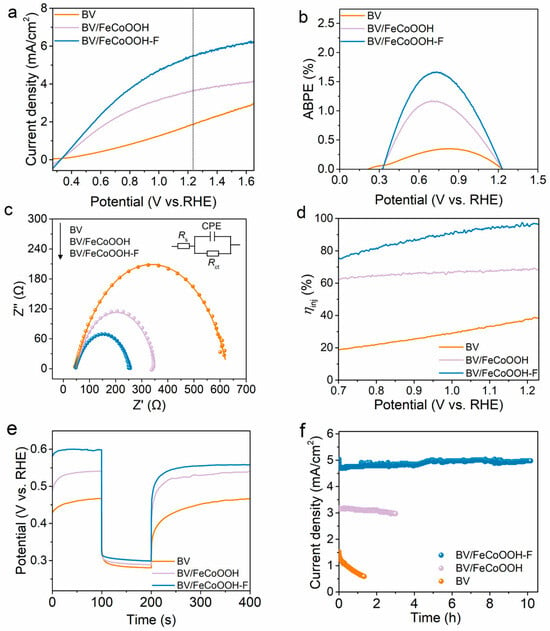

Under AM 1.5 G illumination conditions, the PEC performance of different photoanodes was evaluated using a three-electrode system. As shown in Figure 2a, the BV photoanode shows a low photocurrent density, reaching only 1.85 mA/cm2 at 1.23 VRHE, which is mainly attributed to its poor surface catalytic reaction and severe charge recombination. When FeCoOOH was loaded onto the BV photoanode, the photocurrent density of BV/FeCoOOH increased to 3.63 mA/cm2 at 1.23 VRHE. This improvement mainly originated from the boosted oxygen evolution reaction (OER) kinetics. Even so, the actual photocurrent density still had a large gap from the theoretical expectation. Surprisingly, after the introduction of F element, the optimized BV/FeCoOOH-F integrated system had a photocurrent density as high as 5.46 mA/cm2 at 1.23 VRHE, which is 2.95 times that of the BV photoanode (Figures S4 and S5). The applied bias photoelectric conversion efficiency (ABPE) of BV/FeCoOOH-F reached 1.66% at 0.73 VRHE, which was the highest among all photoanodes (Figure 2b), including BV and BV/FeCoOOH. In addition, electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) was used to explore the interfacial charge transfer behavior of different photoanodes. As shown in Figure 2c, according to the Nyquist diagram and fitting results, the Rct values show the following trend: BV (587 Ω) > BV/FeCoOOH (304 Ω) > BV/FeCoOOH-F (209 Ω). This finding indicates that the doping of F efficiently enhanced interface charge transfer kinetics. Furthermore, the injection efficiency (ƞinj) was evaluated under AM 1.5 G illumination (Figure 2d). As shown in Figure 2d, the BV/FeCoOOH-F photoanode exhibits a higher ƞinj in comparison with BV/FeCoOOH and pristine BV photoanodes at 1.23 V vs. RHE, indicating less carrier recombination. In addition, in order to further explore the origin of the increase in PEC performance, the charge separation efficiency (ηsep) was calculated. In Figure S6, the ηsep of BV/FeCoOOH-F is remarkably larger than that of BV/FeCoOOH-and BV, which can be attributed to the positive role of F engineering in the BV/FeCoOOH-F photoanode.

Figure 2.

(a) LSV curves of different photoanodes under light conditions; (b) ABPE; (c) EIS under light conditions; (d) charge separation efficiencies; (e) open circuit potential (OCP) versus time curves; (f) I-t stability tests of different photoanodes.

To reveal the key positive factors governing charge transfer in different photoanodes, open circuit potential (OCP) decay measurements were conducted. In Figure 2e and Figure S7, the difference in OCP decay (ΔOCP) between dark and light conditions follows the order BV/FeCoOOH-F (0.30 V) > BV/FeCoOOH (0.25 V) > BV (0.19 V), further indicating that F engineering promotes charge separation, which aligns well with the low Rct values (Table S1). Apart from the excellent PEC performance, remarkable photostability also stands out as a crucial factor in industrial application that cannot be overlooked. As depicted in Figure 2f, the photocurrent of BV declines sharply within 1.3 h, which is due to photocorrosion. In contrast, BV/FeCoOOH-F preserved its PEC activity throughout the 10 h continuous test in comparison with BV/FeCoOOH, validating its favorable photostability. Meanwhile, the BV/FeCoOOH-F exhibited a stable stoichiometric H2/O2 molar ratio of approximately 2:1 (Figure S8) and an impressive faradaic efficiency of ≈93% as characterized by online gas chromatography, indicating the efficient utilization of photogenerated charge carriers for water splitting.

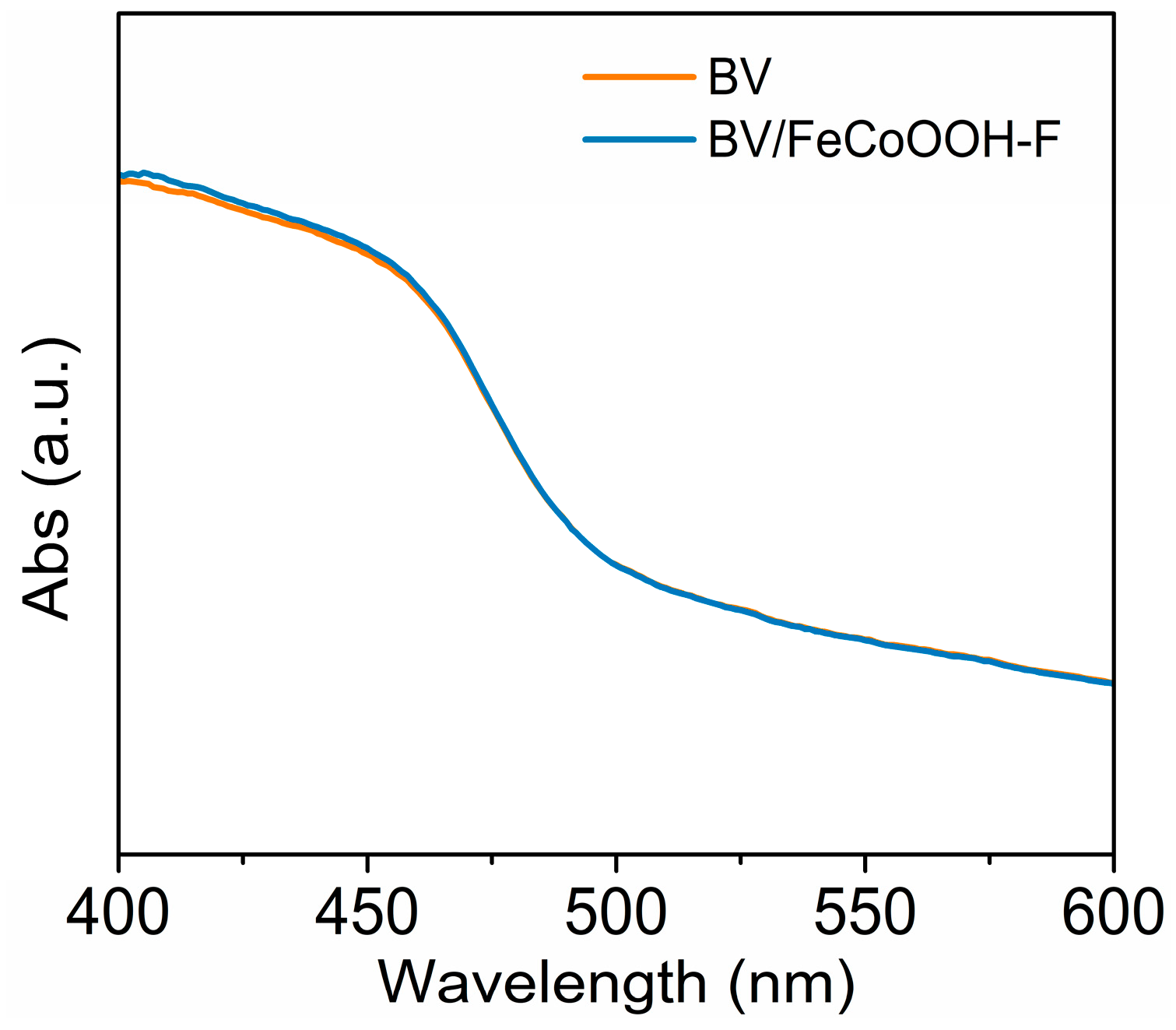

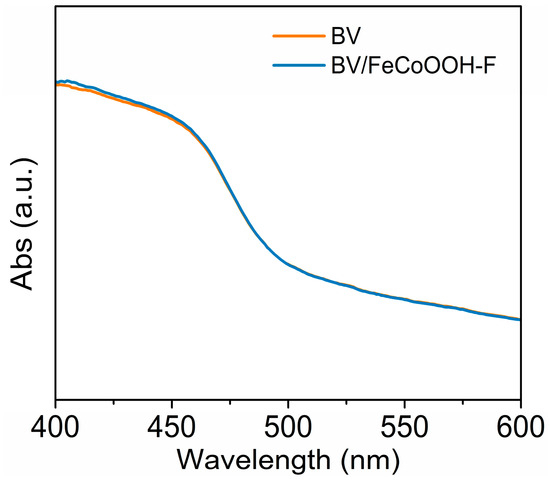

Charge transfer kinetics analysis: In general, the PEC water splitting efficiency is limited by three primary factors, which are light absorption, charge separation, and charge injection efficiencies (ηabs, ηsep and ηinj). To investigate the origin of the improved performance, ultraviolet/visible diffuse reflectance (DRS) spectroscopy was carried out. As shown in Figure 3, compared with BV, the absorption edge of the BV/FeCoOOH-F photoanode shows no significant change, indicating that the introduction of FeCoOOH-F has a negligible effect on the ηabs.

Figure 3.

DRS curves of different photoanodes.

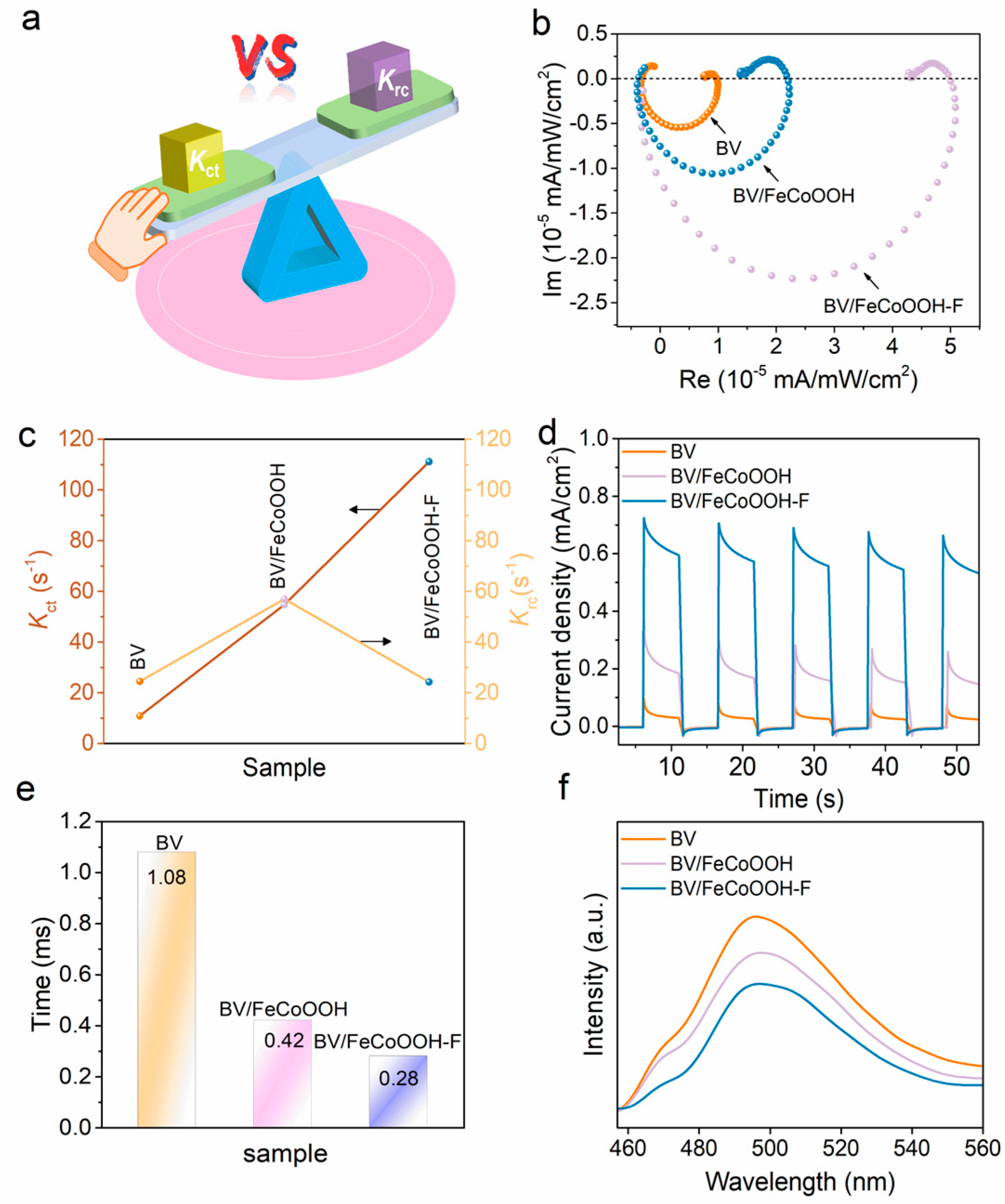

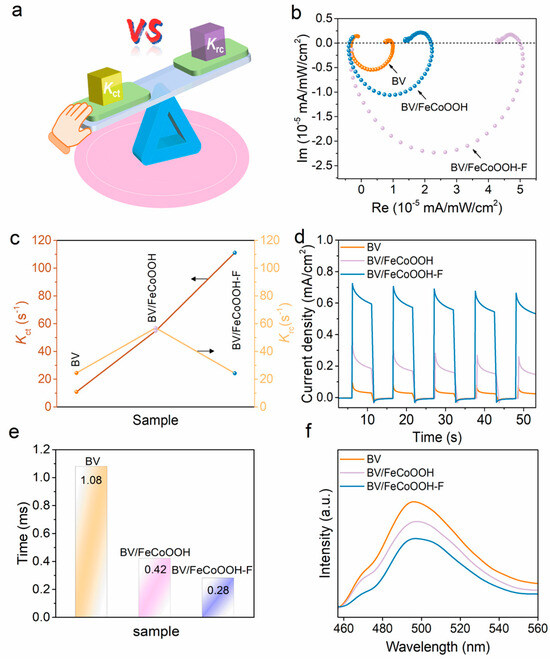

In light of the aforementioned analyses, it can be confirmed that the elevated PEC efficiency is predominantly ascribed to ηsep and ηinj. As such, intensity-modulated photocurrent spectroscopy (IMPS) was employed to further investigate the charge separation of different photoanodes, where Kct and Krc represent the charge transfer rate constant and charge recombination rate constant, respectively (Figure 4a). The IMPS response curves and I-t curves were used to determine the values of Kct and Krc (Figure 4b,c,e). When Krc > Kct, charge recombination dominates, whereas when Kct > Krc, charge transfer becomes the dominant factor. As presented in Figure 4c, for the pure BV photoanode, the Krc > Kct, which is mainly due to the severe charge recombination in the BV photoanode. However, when FeCoOOH was loaded onto the BV surface, Kct increased slightly, proving that it helps reduce charge recombination. Regrettably, a rapid photocurrent decay trend is still observed in Figure 4e, indicating that the charge recombination still dominates in presented integrated systems (as discussed in the Introduction). Surprisingly, after the incorporation of the FeCoOOH-F layer, the BV/FeCoOOH-F photoanode exhibited a remarkable increase in Kct, significantly higher than Krc. This phenomenon arises from the more negative conduction band position of FeCoOOH-F relative to BiVO4, enabling favorable band alignment that thermodynamically accelerates the migration of photogenerated charge carriers and therefore elevates charge separation efficiency, as supported by previous reports [34]. Meanwhile, the I-t curve demonstrated a substantially slower decay in photocurrent for BV/FeCoOOH-F (Figure 4d), indicating that the F engineering effectively suppressed interfacial charge recombination. The transient time (τd) further reflects the fast charge transfer behavior, as shown in Figure 4e and Table S2, with the following trend: BV/FeCoOOH-F (0.28 ms) < BV/FeCoOOH (0.42 ms) < BV (1.08 ms). This result reveals that the introduction of F enhances the charge separation efficiency, consistent with the PL spectroscopy results (Figure 4f). Typically, after F doping, compared to BV and BV/FeCoOOH, the BV/FeCoOOH-F photoanode exhibits lower PL intensity.

Figure 4.

(a) Principle of the IMPS setup; (b) IMPS responses for BV, BV/FeCoOOH and BV/FeCoOOH-F; (c) charge transfer rate and recombination rate constant; (d) I-t curves; (e) transient time of different samples; (f) fluorescence spectra of different samples.

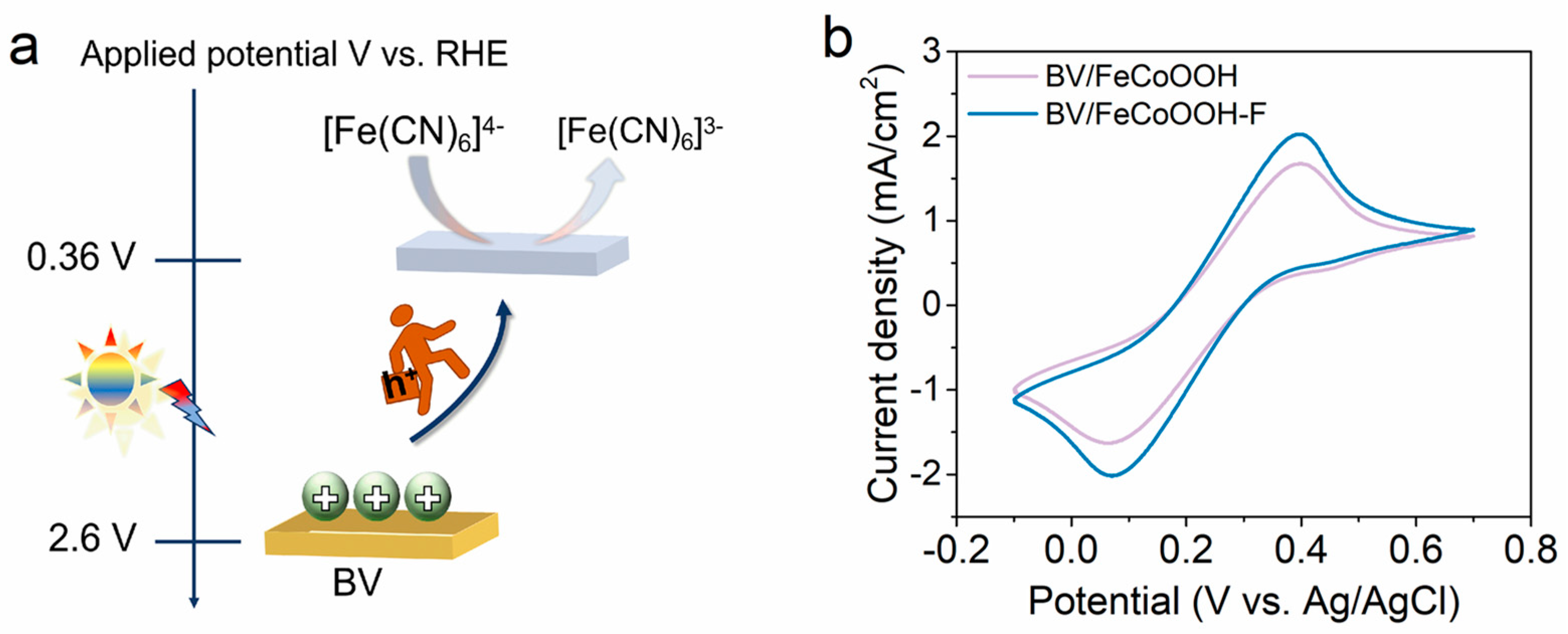

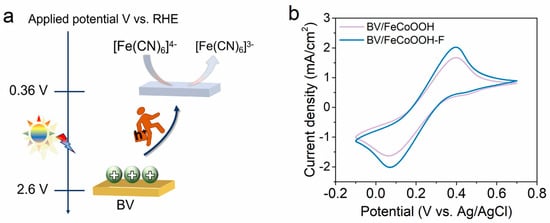

Although F engineering can efficiently suppress interfacial charge recombination, whether it can transfer photogenerated holes to the electrode surface remains unknown. Therefore, we employed a simple and smart cyclic voltammetry (CV) method, combined with [Fe(CN)6]3−/[Fe(CN)6]4− probe molecules with redox properties, to investigate the charge transfer behavior (Figure 5a). As shown in Figure 5b, distinct characteristic redox peaks were obviously observed. Under light conditions, the anodic and cathodic current densities of BV/FeCoOOH-F were dramatically higher than those of BV/FeCoOOH. This enhancement is mainly attributed to the optimization of the SC/TMOOH interface via F engineering, because a greater number of photogenerated holes can be more readily transferred to the photoelectrode surface to participate in the water splitting process.

Figure 5.

(a) The soft probe molecules are oxidized by the holes accumulated on the surface of the BV photoanode; (b) cyclic voltammetry (CV) curves of different samples.

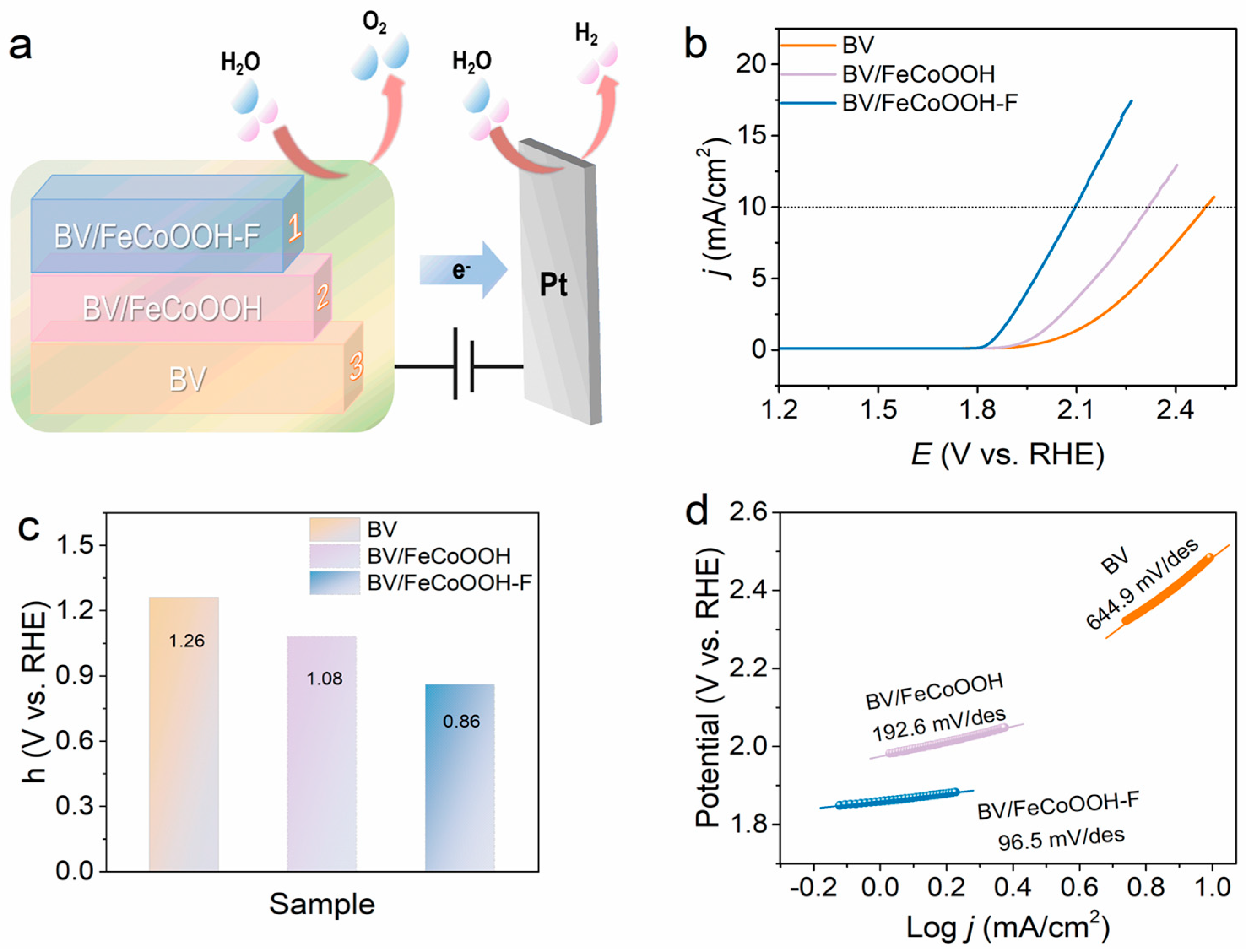

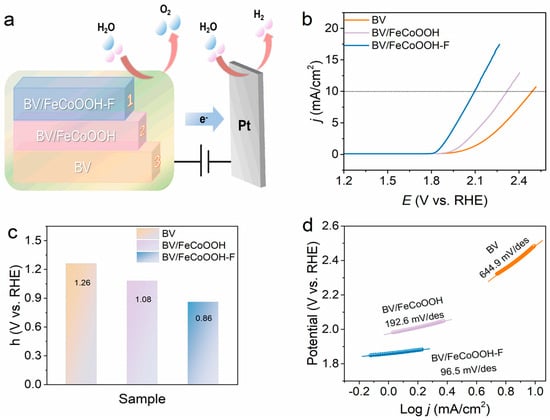

Surface catalytic analysis: F engineering not only promotes efficient interfacial charges’ separation but also raises the question of whether it activates the BV/FeCoOOH-F/electrolyte interface, i.e., facilitates the surface catalytic process, which still requires further investigation. Therefore, the surface catalytic performance of different photoanodes was investigated using a standard three-electrode system. The results showed that the BV/FeCoOOH-F photoanode exhibits a higher current density and a lower overpotential compared to BV and BV/FeCoOOH (Figure 6b,c). Specifically, at a current density (j) of 10 mA/cm2, the overpotential (η) of BV/FeCoOOH-F was 210 mV, significantly lower than those of BV (249 mV) and BV/FeCoOOH (232 mV). This improvement arises from the enhanced OER activity induced by F, which accelerates surface catalytic reactions. In Figure 6d, compared to BV/FeCoOOH (192.6 mV/dec) and BV (644.9 mV/dec), BV/FeCoOOH-F exhibits a lower Tafel slope (96.5 mV/dec). These results indicate that the remarkable surface catalytic performance can be rationalized by the high electronegativity of fluorine, which gives rise to an enhanced positive charge density at the Fe sites within the FeCoOOH cocatalyst, thus yielding more favorable OER catalytic activity than undoped FeCoOOH. This mechanism is further supported by previous reports [34]. Collectively, we confirm that F engineering strengthens charge separation and improves the catalytic activity, which can be confirmed by EIS results (Figure S9 and Table S3).

Figure 6.

(a) The process of water oxidation; (b) iR-corrected LSV curves of different samples; (c) overpotential (η) values at a current density of 10 mA/cm2; (d) Tafel plots of different samples.

4. Conclusions

Herein, we demonstrate a smart F engineering strategy to enhance photocurrent density by activating semiconductor/electrocatalyst/electrolyte interfaces. As expected, the optimized BiVO4/FeCoOOH-F photoanode exhibits a remarkable photocurrent of up to 5.46 mA/cm2, along with excellent photostability. IMPS, EIS and OER measurements collectively verify that the improved PEC performance is attributable to the accelerated kinetics at the BiVO4/FeCoOOH-F/electrolyte interfaces. Specifically, the BiVO4/FeCoOOH-F photoanode displays the highest hole transfer rate constant of 111.13 s−1 among all samples, which is 10 times higher than that of pristine BV (10.85 s−1). In addition, the Tafel slope of BiVO4/FeCoOOH-F decreases substantially from 644.9 to 96.5 mV/dec, indicating faster surface catalytic reaction kinetics. These findings not only provide a facile and efficient design strategy for PEC water splitting but also provide insightful guidance for the rational construction of high-performance energy conversion systems.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/separations13020063/s1, Figure S1: X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of different samples; Figure S2: Raman spectra of different samples; Figure S3: (a) X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) spectra of BV/FeCoOOH-F; (b) XPS of F 1s of BV/FeCoOOH-F; Figure S4: Linear sweep voltammetry (LSV) curves of different samples; Figure S5: Linear sweep voltammetry (LSV) curves obtained under different immersion times; Figure S6: Charge separation efficiency; Figure S7: OCP values under both dark and light conditions; Figure S8: The actual and theoretical H2 and O2 evolution and the faradaic efficiency of BV/FeCoOOH-F; Figure S9: EIS under dark conditions; Table S1: EIS of different samples under light conditions; Table S2: EIS of different samples under dark conditions; Table S3: Transient time of different samples.

Author Contributions

J.Q. conceived and designed experiments. J.Q., L.L. and X.N. directed the experiments and revised the paper. L.Y. performed the measurements. Y.Z. accomplished XPS, XRD, and PEC measurement and consulted the literature. J.Q. and X.N. wrote the paper. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (GK202403002) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (22202126).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ma, Z.; Song, K.; Wang, L.; Gao, F.; Tang, B.; Hou, H.; Yang, W. WO3/BiVO4 type-II heterojunction arrays decorated with oxygen-deficient ZnO passivation layer: A highly efficient and stable photoanode. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 11, 889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, C.; Heggen, M.; Zabka, W.D.; Cui, W.; Osterwalder, J.; Probst, B.; Alberto, R. Atomically dispersed hybrid nickel-iridium sites for photoelectrocatalysis. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Zhang, N.; Li, Y.; Fan, R.; Wang, W.; Feng, J.; Liu, C.; Wang, J.; Hao, W.; Li, Z.; et al. Long-term durability of metastable β-Fe2O3 photoanodes in highly corrosive seawater. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 4266. [Google Scholar]

- Xing, X.; Gao, Q.; Feng, C.; Zhou, Z.; Liu, X.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, J.; Du, J.; Zhang, H. Interfacial engineering induced charge accumulation for enhanced solar water splitting. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, e19825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, X.; Wang, Y.; Sun, X.; Yu, F.; Zhong, J.; Xiao, J. Enhanced water-splitting performance of hematite photoanodes via fluorine-induced carrier dynamics and lattice oxygen activation. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, 35, 2505716. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, R.; Zhang, J.; Nakajima, T.; He, J.; Liu, X.; Zhang, X.; Wang, L.; Wu, L. Single-atomic-site platinum steers photogenerated charge carrier lifetime of hematite nanoflakes for photoelectrochemical water splitting. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 2640. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Xiao, Y.; Fu, J.; Pihosh, Y.; Karmakar, K.; Zhang, B.; Domen, K.; Li, Y. Interface engineering for photoelectrochemical oxygen evolution reaction. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2025, 54, 1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, J.; Fan, Z.; Nakabayashi, M.; Ju, H.; Pastukhova, N.; Xiao, Y.; Feng, C.; Shibata, N.; Domen, K.; Li, Y. Interface engineering of Ta3N5 thin film photoanode for highly efficient photoelectrochemical water splitting. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, X.; Zhang, S.; Yin, D.; Du, P.; Lu, X. In operando visualization of charge transfer dynamics in transition metal compounds on water splitting photoanodes. Adv. Energy Mater. 2025, 15, 2405137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, Y.; Tian, J.; Xiong, X.; Wu, C.; Carabineiro, S.A.; Yang, X.; Chen, Z.; Xia, Y.; Jin, Y. Enhanced photocatalytic efficiency through oxygen vacancy-driven molecular epitaxial growth of metal–organic frameworks on BiVO4. Adv. Mater. 2025, 37, 2417589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, N.; Zhang, S.; Xiao, Y.; Qi, Y.; Bao, Y.; Xu, P.; Jin, S.; Zhang, F. Insight into the key restriction of BiVO4 photoanodes prepared by pyrolysis method for scalable preparation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202308729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Muhammad, N.; Chuai, Z.; Xu, W.; Tan, X.; Zhou, Q.; Yu, Y.; Guo, J.; Li, T.; Xu, B. Photothermal CuS as a hole transfer layer on BiVO4 photoanode for efficient solar water oxidation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2025, 64, e202507259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegde, C.; Rosental, T.; Tan, J.; Magdassi, S.; Wong, L. Angle-independent solar radiation capture by 3D printed lattice structures for efficient photoelectrochemical water splitting. Mater. Horiz. 2023, 10, 1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Sun, W.; Li, B.; Dong, Y.; Huang, X.; Hu, C.; Chen, M.; Li, Y.; Ding, Y. P-doped Mn0.5Cd0.5S coupled with cobalt porphyrin as co-catalyst for the photocatalytic water splitting without using sacrificial agents. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2024, 655, 779. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yin, H.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, N.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Jiang, R. Boosting photoelectrochemical water oxidation by sandwiching gold nanoparticles between BiVO4 and NiFeOOH. J. Mater. Chem. A 2023, 11, 24239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, J.; Li, Y.; Shi, Y.; Huang, J.; Mei, Q.; Wang, L.; Ding, F.; Bai, B.; Wang, Q. Heterostructured CoFe1.5Cr0.5S3O/COFs/BiVO4 photoanode boosts charge extraction for efficient photoelectrochemical water splitting. Appl. Catal. B 2023, 336, 122921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhen, C.; Li, N.; Jia, N.; Xu, X.; Wang, L.; Liu, G. Photochemically etching BiVO4 to construct asymmetric heterojunction of BiVO4/BiOx showing efficient photoelectrochemical water splitting. Small Methods 2023, 7, 2201611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Z.; Meng, L.; Cao, F.; Li, L. Wrapping BiVO4 with chlorophyll for greatly improved photoelectrochemical performance and stability. Sci. China Mater. 2022, 65, 1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, R.; Liu, S.; Guo, X.; Zhang, R.; He, J.; Liu, X.; Nakajima, T.; Zhang, X.; Wang, L. Pt-Induced defects curing on BiVO4 photoanodes for near-threshold charge separation. Adv. Energy Mater. 2021, 11, 2102384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, J.; Wei, Z.; Guo, W.; Fang, W.; Yan, J.; Huang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Luo, H.; Wang, J.; Liu, J.; et al. Enhanced photoelectrochemical water splitting on BiVO4 photoanode via efficient hole transport layers of NiFe-LDH. ACS Catal. 2025, 15, 11293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhai, P.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Wang, C.; Ran, L.; Gao, J.; Li, Z.; Zhang, B.; Fan, Z.; et al. Engineering single-atomic Ni-N4-O sites on semiconductor photoanodes for high-performance photoelectrochemical water splitting. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 20657. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.; Mujtaba, S.; Quan, J.; Xu, L.; Ning, X.; Chen, P.; An, Z.; Chen, X. Activation of Semiconductor/Electrocatalyst/Electrolyte interfaces through ligand engineering for boosting photoelectrochemical water splitting. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, 35, 2501262. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, L.; Ning, X.; Quan, J.; Li, C.; Yao, L.; Weng, Q.; Chen, P.; An, Z.; Chen, X. Unlocking the potential of photoelectrochemical water splitting via heterointerface charge polarization. Adv. Sci. 2025, 12, e2502384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.; Choi, K. Nanoporous BiVO4 photoanodes with dual-Layer oxygen evolution catalysts for solar water splitting. Science 2014, 343, 990. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Z.; Liu, X.; Li, H.; Sun, Z.; Cao, M.; Li, Z.; Fang, C.; Zhou, J.; Cao, C.; Dong, J.; et al. A semiconductor-electrocatalyst nano interface constructed for successive photoelectrochemical water oxidation. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 2574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Liu, H.; Dang, L.; Zhang, H.; Wu, X.; Yang, B.; Li, Z.; Zhang, X.; Lei, L.; Jin, S. Amorphous Cobalt–Iron hydroxide nanosheet electrocatalyst for efficient electrochemical and photo-electrochemical oxygen evolution. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2017, 27, 1603904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, X.; Du, P.; Han, Z.; Chen, J.; Lu, X. Insight into the transition-metal hydroxide cover layer for enhancing photoelectrochemical water oxidation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 3504. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, B.; Huang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, G.; Chou, L.; Bi, Y. Unveiling the activity and stability origin of BiVO4 photoanodes with FeNi oxyhydroxides for oxygen evolution. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 18990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sambur, J.; Chen, T.; Choudhary, E.; Chen, G.; Nissen, E.J.; Thomas, E.M.; Zou, N.; Chen, P. Sub-particle reaction and photocurrent mapping to optimize catalyst-modified photoanodes. Nature 2016, 530, 77. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.; Deng, C.; Lei, Y.; Duan, M.; Yang, Y.; Chen, X.; Yang, S.; Li, J.; Sheng, H.; Shi, W.; et al. Fe−N Co-Doped BiVO4 Photoanode with record photocurrent for water oxidation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2025, 137, e202416340. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, K.; Jin, B.; Park, C.; Cho, Y.; Song, X.; Shi, X.; Zhang, S.; Kim, W.; Zeng, H.; Park, J.H. Black phosphorene as a hole extraction layer boosting solar water splitting of oxygen evolution catalysts. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, X.; Lu, B.; Zhang, Z.; Du, P.; Ren, H.; Shan, D.; Chen, J.; Gao, Y.; Lu, X. An efficient strategy for boosting photogenerated charge separation by using porphyrins as interfacial charge mediators. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 16800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, D.; Remmani, R.; Bavasso, I.; Bracciale, M.P.; Di Palma, L. Biochar supported Fe-TiO2 composite for wastewater treatment: Solid-state synthesis and mechanistic insights. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2025, 317, 122076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Mei, Q.; Liu, Z.; Hu, X.; Zhou, Z.; Huang, J.; Bai, B.; Liu, H.; Ding, F.; Wang, Q. Fluorine-doped iron oxyhydroxide cocatalyst: Promotion on the WO3 photoanode conducted photoelectrochemical water splitting. Appl. Catal. B 2022, 304, 120995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Ye, B.; Ouyang, B.; Zhang, T.; Tang, T.; Qiu, Z.; Li, S.; Li, Y.; Chen, R.; Wen, W.; et al. Dual doping of N and F on Co3O4 to activate the lattice oxygen for efficient and robust oxygen evolution reaction. Adv. Mater. 2025, 37, 2501381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.