Abstract

In this study, a novel Bi2O3/BiOBr0.9I0.1 (BO0.9−BBI0.1) composite photocatalyst was successfully synthesized via a single-pot solvothermal method for the efficient degradation of 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4-D) under visible light. The structure, morphology, and optical properties of the photocatalyst were characterized through X-ray diffraction (XRD), Scanning electron microscopy (SEM), X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), UV–vis diffuse reflectance spectra (DRS), Steady-state photoluminescence (PL), and Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS). The composite exhibits a 3D hierarchical morphology with increased specific surface area and optimized pore structure, enhancing pollutant adsorption and providing more active sites. Under visible light irradiation, BO0.9−BBI0.1 achieved a 92.4% removal rate of 2,4-D within 2 h, with a reaction rate constant 5.3 and 4.6 times higher than that of pure BiOBr and BiOI, respectively. Mechanism studies confirm that photogenerated holes (h+) and superoxide radicals (·O2−) are the primary active species, and the Z-scheme charge transfer pathway significantly promotes the separation of electron-hole pairs while maintaining strong redox capacity. The catalyst also demonstrated good stability over multiple cycles. This work provides a feasible dual-modification strategy for designing efficient bismuth-based photocatalysts for pesticide wastewater treatment.

1. Introduction

In modern agriculture, the extensive consumption of herbicides, urban landscaping practices, and improper storage or disposal lead to their ingress into environmental water bodies via surface runoff or soil infiltration. This results in the contamination of soil, groundwater, rivers, lakes, stormwater, and air, severely polluting the ecological environment. 2,4-Dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4-D) is one of the earliest synthetic auxin herbicides widely applied for controlling both annual and perennial weeds [1,2]. It exhibits a systemic mode of action: penetrating leaves, reaching their vascular tissues, and spreading throughout the plant, thereby promoting excessive and disordered growth. At low concentrations, it stimulates cell division and elongation, yet ultimately leads to developmental retardation of leaves and stems, while prolonging the shelf life of fruits. However, it possesses a high potential for environmental pollution [3,4]. Owing to its mode of action, efficiency, selectivity, and low cost, 2,4-D remains one of the most extensively used herbicides globally in agricultural, aquatic, and horticultural sectors to this day. Furthermore, its commercial formulations are readily soluble in water and other solvents, facilitating rapid penetration into leaves and roots, which enhances its herbicidal efficacy [5].

In order to deal with the threat posed by 2,4-D to the aquatic environment, researchers have developed a variety of biological, physical, and chemical treatment methods. Semiconductor photocatalytic degradation, a type of Advanced Oxidation Process (AOP), is regarded as one of the most promising methods for removing 2,4-D residues or antibiotics from aqueous solutions due to its effectiveness and ease of application. It offers a potential approach for the thorough eradication of toxic chemicals in the environment, namely toxic gases and aqueous pollutants. Photocatalytic technology represents a greener, lower-cost, and safer water treatment strategy because it actively utilizes renewable solar energy to convert harmful pollutants into harmless products without requiring other oxidizing chemicals. This technology functions based on redox reactions initiated by light-excited semiconductors, which generate electrons (e−) and holes (h+) [6]. These charge carriers subsequently degrade larger organic pollutants into non-toxic organic species or small molecules such as CO2 and H2O.

In previous studies, modification strategies such as constructing solid solutions and heterojunctions have been demonstrated to be among the most effective methods for enhancing photocatalytic performance [7]. Solid solutions can modulate the band structure of semiconductors, promote the separation of photogenerated electron-hole pairs (e−-h+), and improve the photocatalytic performance of materials [7,8]. Yu et al. [5] synthesized BiOBrxI1−x solid solutions via a solvothermal method, which exhibited significantly enhanced performance in the photocatalytic degradation of 2,4-D compared to pristine BiOBr and BiOI. This confirms that constructing a BiOBrxI1−x solid solution structure can effectively regulate the band structure of BiOX-based semiconductor photocatalytic materials. Meanwhile, heterojunction photocatalysts possess superior photocatalytic performance compared to single-phase photocatalysts. In summary, the dual-modification strategy of combining the construction of a BiOBrxI1−x solid solution with a Bi2O3/BiOX heterojunction is expected to enhance the photocatalytic activity of BiOBr and achieve highly efficient removal of 2,4-D.

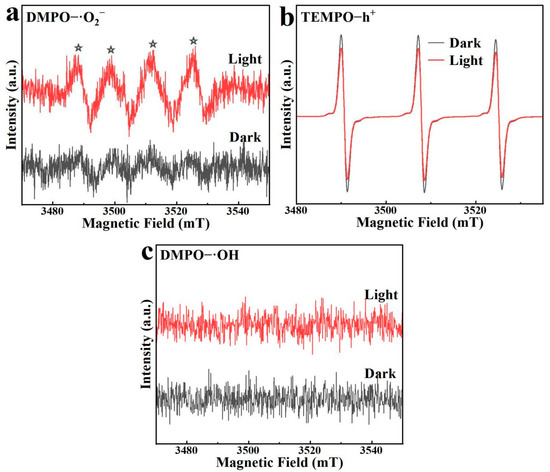

In this study, a Bi2O3/BiOBrxIγ adsorption-photocatalyst was successfully prepared via a single-pot solvothermal method and applied for the degradation of 2,4-D. The photocatalytic reaction phase was kinetically analyzed using a pseudo-first-order model. The crystal structures and phase compositions of various BiOI and S-BiOI materials were analyzed through characterization techniques including XRD and FT-IR. The micromorphology, elemental distribution, and valence states of the photocatalysts were investigated using SEM, TEM, and XPS. The specific surface area, pore volume, and pore size distribution of the materials were characterized by BET analysis. The light absorption properties, electrochemical performance, and separation efficiency of photogenerated electron-hole pairs were evaluated via UV-Vis DRS, EIS, and PL measurements. Furthermore, the primary active free radicals responsible for the photocatalytic degradation of 2,4-D were identified by ESR analysis. Based on these results combined with the band structure analysis, the mechanism for the photocatalytic degradation of 2,4-D by S-BiOI was proposed. The use of 2,4-D for the degradation of pollutants has important practical significance for the efficient catalytic degradation of pesticides, promoting the development and practical application of this safe and sustainable process.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Bi(NO3)3·5H2O, KI, KBr, Bi2O3, NaOH, iso-Propyl alcohol (IPA), absolute ethanol, sodium oxalate (SO), and ethylene glycol (EG) were purchased from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China. Ascorbic acid (AA) was purchased from Xilong Chemical Industry Incorporated Co., Ltd., Shantou, China. 2,4-D (97%) was purchased from Shanghai Macklin Biochemical Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China. Concentrated HCl and concentrated HNO3 were purchased from Chengdu Kelong Chemical Co., Ltd., Chengdu, China. All reagents and chemicals were of analytical grade and were used without further purification.

2.2. Preparation

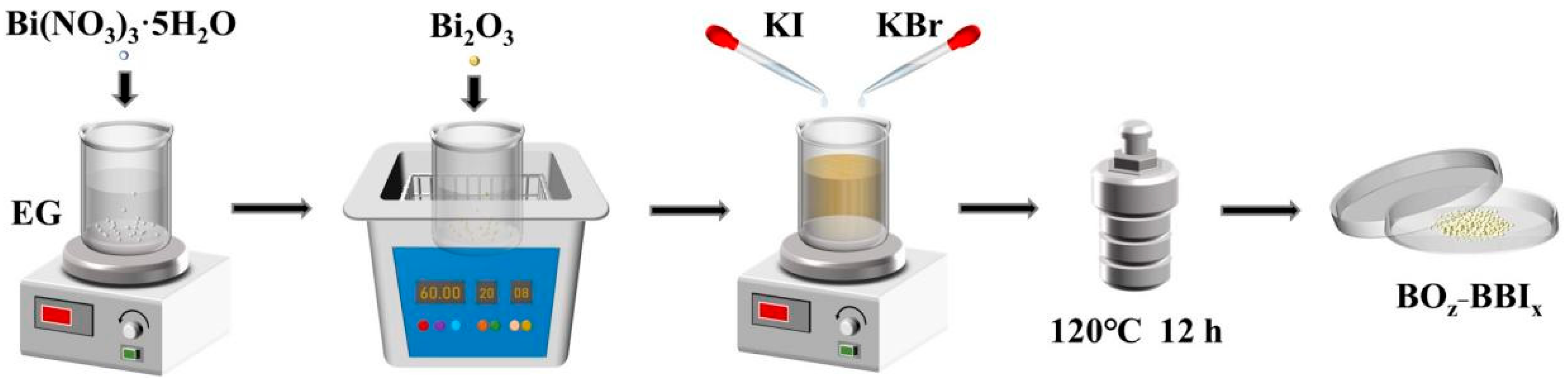

Preparation of Bi2O3/BiOBrγIx

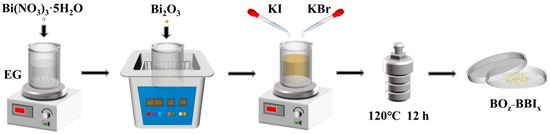

1.458 g of Bi(NO3)3·5H2O (3 mmol) was weighed and added to 60 mL of ethylene glycol (EG). The mixture was stirred for 1 h to obtain a colorless transparent Bi(NO3)3 solution. (1.398z) g of Bi2O3 (3z mmol) was added to the Bi(NO3)3 solution (z = 0.7, 0.8, 0.9, 1.0), followed by ultrasonication for 1 h. To the ultrasonicated solution, (1.5x) mL of a 0.2 mol/L KI solution and (1.5y) mL of a 0.2 mol/L KBr solution were added dropwise (x + y = 1, and x = 0, 0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.4, and 1.0). The mixture was then stirred for 0.5 h. The mixed solution was transferred into a 100 mL Teflon-lined autoclave and maintained at 120 °C for 12 h, followed by natural cooling to room temperature. The resulting suspension was filtered, and the filter residue was collected. It was washed several times with deionized water and ethanol, then dried at 60 °C for 8 h to obtain light-yellow (100z)% Bi2O3/BiOBrγIx powder. BiOBrγIx is denoted as BBIx, and (100z)% Bi2O3/BiOBrγIx is denoted as BOz−BBIx. The entire synthesis is conducted in a single reaction vessel without any intermediate isolation or purification steps. The formation of both the BiOBrγIx solid solution and the Bi2O3/BiOBrγIx heterojunction occurs in situ during the one-step solvothermal process. Therefore, this method is accurately described as a single-pot solvothermal synthesis method. The preparation of BOz−BBIx is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the synthesis of BOz−BBIx catalyst.

2.3. Characterization

X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns (Cu target, Kα rays; 2θ = 10–80°) were obtained using a X-ray diffractometer (SmartLab SE, Rigaku Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) maps and element distribution diagrams were obtained using a field emission scanning electron microscope (Sigma 300, Carl Zeiss AG, Oberkochen, Germany). The element composition and valence distribution information (Al Kα ray) of materials were obtained using an X-ray photoelectron spectrometer (ESCALAB Xi+, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). UV–vis diffuse reflectance spectra (BaSO4 substrate, scan range: 200–800 nm) were obtained using a UV–vis spectrophotometer (UV-3600 Plus, Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan). Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) parameters were obtained using a 4-station automatic specific surface area analyzer (Micromeritics ASAP 2460, Micromeritics Instrument Corporation, Norcross, GA, USA). Steady-state photoluminescence (PL) spectra (excitation wavelength 355 nm) were obtained using a photoluminescence spectrometer (FLS1000, Edinburgh Instruments Ltd., Livingston, UK). Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) spectra of samples were obtained by using an electrochemical workstation (CHI-660E, Shanghai Chenhua Instrument Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China). The free radicals within each sample system were captured by DMPO and TEMPO using a paramagnetic resonance spectrometer (EMXplus-6/1, Bruker Corporation, Karlsruhe, Germany). DMPO is commonly used to trap superoxide (·O2−) and hydroxyl (·OH) radicals, while TEMPO is employed to capture photogenerated holes (h+) through a distinct electron transfer quenching mechanism.

2.4. Measurements

2.4.1. Photocatalytic Activity

To evaluate the removal efficiency of the as-prepared adsorption-photocatalyst for 2,4-D under visible light irradiation, photocatalytic experiments were conducted using a 300 W xenon lamp (PLS-SXE300D, Beijing Perfectlight Technology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China) equipped with a filter (UVCUT420, Beijing Perfectlight Technology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China) as the visible light source. The light source was positioned approximately 13 cm above the solution surface. A 100 mL volume of 10 mg/L 2,4-D solution, serving as the target pesticide-contaminated water body, was placed in a 150 mL jacketed beaker and positioned on a magnetic stirrer operating at 600 rpm. The ambient temperature of the reaction system was controlled using a water-circulating thermostatic bath connected to the jacketed beaker via rubber tubing, maintaining the temperature at 25 °C throughout the reaction process.

The entire experimental procedure consisted of a 45 min reaction phase in dark conditions followed by a 2 h reaction phase under light exposure. Firstly, 50 mg of the adsorption-photocatalyst was accurately weighed and added to the 2,4-D solution. The jacketed beaker was placed in a light-proof dark box to allow the mixed solution to reach adsorption–desorption equilibrium. After the predetermined dark adsorption duration, the setup was transferred under the xenon lamp to initiate the illumination experiment.

Solution samples were collected at 15 min intervals during the dark adsorption stage and at 30 min intervals during the illumination stage. For each sampling, 3 mL of the suspension was aspirated using a rubber-bulb pipette and then filtered through a syringe equipped with a 0.45 μm filter. The resulting filtrate was collected for subsequent analysis. The absorbance of the filtrate was measured at 282 nm using a UV-vis spectrophotometer (UV-2600, Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan) to determine the residual concentration of 2,4-D in the solution. The overall adsorption-photocatalytic removal efficiency of 2,4-D by the samples was then calculated based on these measurements.

2.4.2. Photocatalyst Sample Stability

The photocatalyst samples were recycled and reused to determine their long-term stability. The specific procedure used to separate the catalyst samples from solution involved high-speed centrifugation after the experiment, as described in Section 2.4.1. The collected catalyst samples were dried at 60 °C and then applied to another cycle of photocatalysis under the experimental conditions described in Section 2.4.1, with this process repeated for 4 cycles of reuse.

2.4.3. Evaluation of the Effect of Different Factors

The degradation performance of the photocatalyst samples was tested by varying the 2,4-D concentration, photocatalyst dosage, pH, and coexisting anions in the reaction system as single-factor variables. The corresponding procedure is described in Section 2.4.1.

2.4.4. Free Radicals

It is generally accepted that photogenerated holes (h+), superoxide radicals (·O2−), and hydroxyl radicals (·OH) are the main active radicals in the photocatalytic process. SO, AA, and IPA were used as free radical trapping agents. In the experiment, 1 mmol of free radical trapping agent was first weighed and placed in 100 mL of 10 mg/L 2,4-D solution, with 50 mg of photocatalyst sample then added to initiate photocatalytic activity. The operational procedure was as described in Section 2.4.1.

2.5. Sampling and Analysis

2.5.1. 2,4-D Analysis Method

In order to determine the concentration of 2,4-D solution every 30 min within the reaction period, the absorbance of 2,4-D solution was measured at the maximum absorption wavelength of 282 nm by UV–vis spectrophotometry. The 2,4-D removal efficiency in the reaction system was determined using Equation (1):

where Ct is the concentration of 2,4-D after t minutes of reaction and C0 is the concentration of 2,4-D at the start of the reaction.

η = (1 − Ct/C0) × 100%

2.5.2. Dynamic Analysis of the Degradation Process

It is commonly accepted that a quasi-first-order kinetic model can be used to analyze degradation data when the pollutant concentration is low, as shown in Equation (2). The model was used for photocatalytic degradation data fitting and kinetic analysis.

where k is the rate constant (min−1) and t is the reaction time (min).

ln(Ct/C0) = −kaKC0 = −kt

2.5.3. Kinetic Modeling Considerations

In photocatalysis, the degradation kinetics of organic pollutants can be described by empirical or mechanistic models. Under low initial pollutant concentrations (e.g., ≤20 mg L−1), the pseudo-first-order model (Equation (2)) is frequently employed as a practical tool to compare the apparent rate constants among different catalysts, since the adsorption of pollutants on the catalyst surface is not the rate-limiting step under such conditions [6,9]. However, to better understand the role of catalyst surface and adsorption in the photocatalytic process, the Langmuir–Hinshelwood (L-H) model was also applied to our experimental data (Equation (3)) [10]:

where is the reaction rate, is the intrinsic rate constant, and is the adsorption equilibrium constant. The results confirm that the enhanced performance of BO0.9−BBI0.1 is attributed not only to improved charge separation but also to its higher specific surface area and adsorption capacity, consistent with BET and adsorption experiments (Section 3.2).

3. Results and Discussion

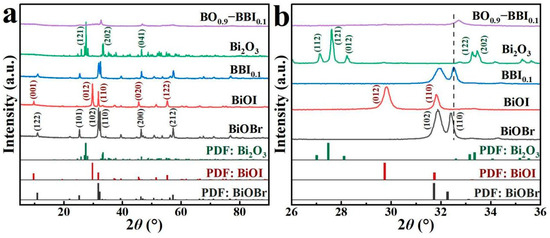

3.1. Crystal Structure and Phase Composition

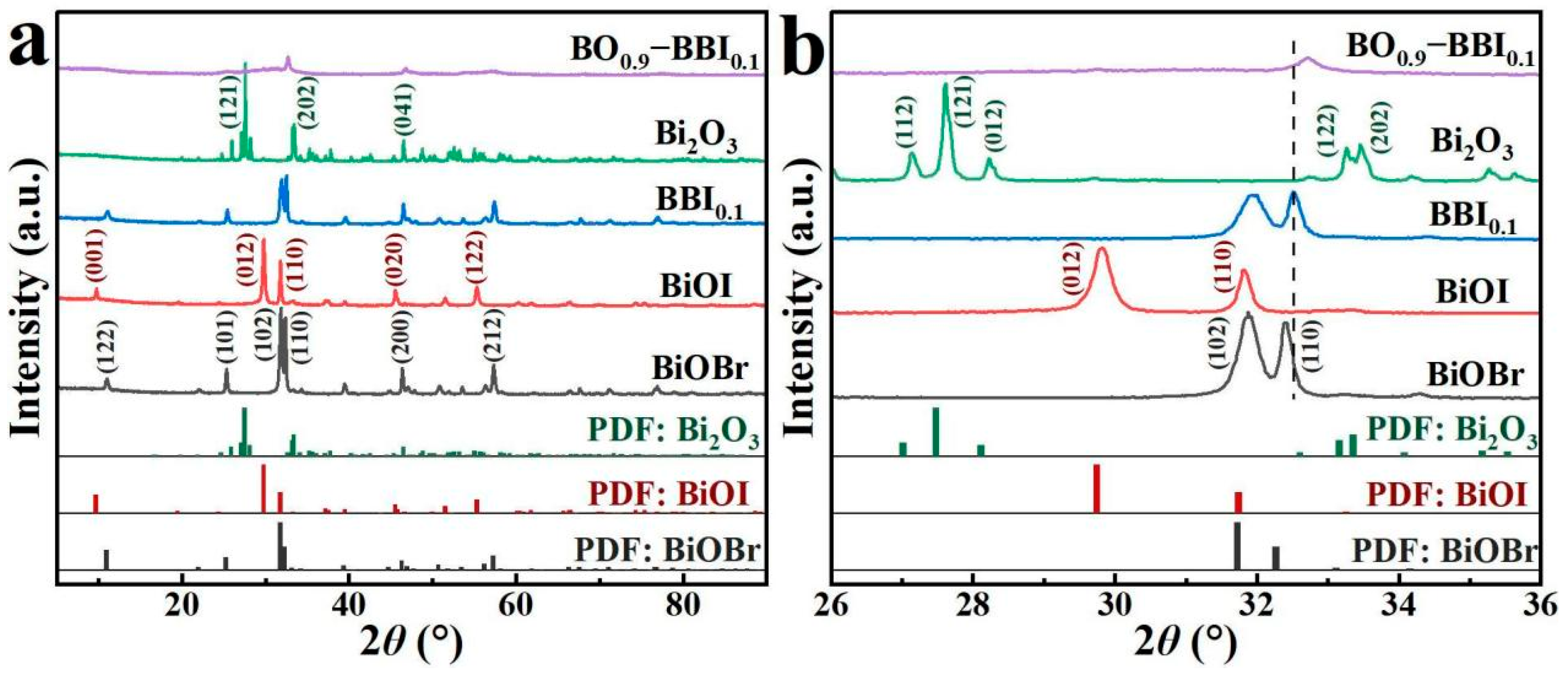

XRD analysis was used to characterize the crystal structure and phase composition of the photocatalyst samples, allowing the evolution of the crystal structure of the composite photocatalyst to be determined compared with the monomer. The interfacial interaction among semiconductor is important for charge transfer [11]. As shown in Figure 2, the peak of each catalyst sample was sharp, indicating a high crystallinity in each catalyst sample. The diffraction peaks of the as-prepared BiOBr at 2θ = 11.0°, 25.3°, 31.9°, 32.4°, 46.4°, and 57.3° correspond to the (122), (101), (102), (110), (200), and (212) crystal planes of the standard BiOBr card (PDF#85−0862), respectively. The peaks of the as-prepared BiOI at 2θ = 9.8°, 29.8°, 31.8°, 45.6°, and 55.3° correspond to the (001), (012), (110), (020), and (122) crystal planes of the standard BiOI card (PDF#73−2062), respectively.

Figure 2.

XRD patterns of photocatalyst samples: (a) 10–80°; (b) 26–36°.

As shown in Figure 2b, after BiOBr and BiOI were combined to form the BBI0.1 solid solution, slight shifts in the crystal planes were observed. The original dominant (102) plane of BiOBr and the (012) plane of BiOI were replaced by the (110) plane as the predominant crystal facet. According to previous studies, the (110) dominant crystal plane exhibits higher photoactivity than the (102) plane of BiOBr and the (012) plane of BiOI, making it more conducive to the photocatalytic removal of pollutants by the material [12,13]. Meanwhile, the detected peaks for Bi2O3 at 2θ = 27.6°, 33.5°, and 46.5° correspond to the (121), (202), and (041) crystal planes of the standard Bi2O3 card (PDF#76−1730), respectively. After constructing the heterojunction between BBI0.1 and Bi2O3, the XRD peaks of BO0.9−BBI0.1 became relatively broadened, with the dominant crystal plane located at 2θ = 32.7°. No other peaks appeared in the XRD pattern of BO0.9−BBI0.1, indicating that the prepared composite photocatalyst was free of impurities [14,15].

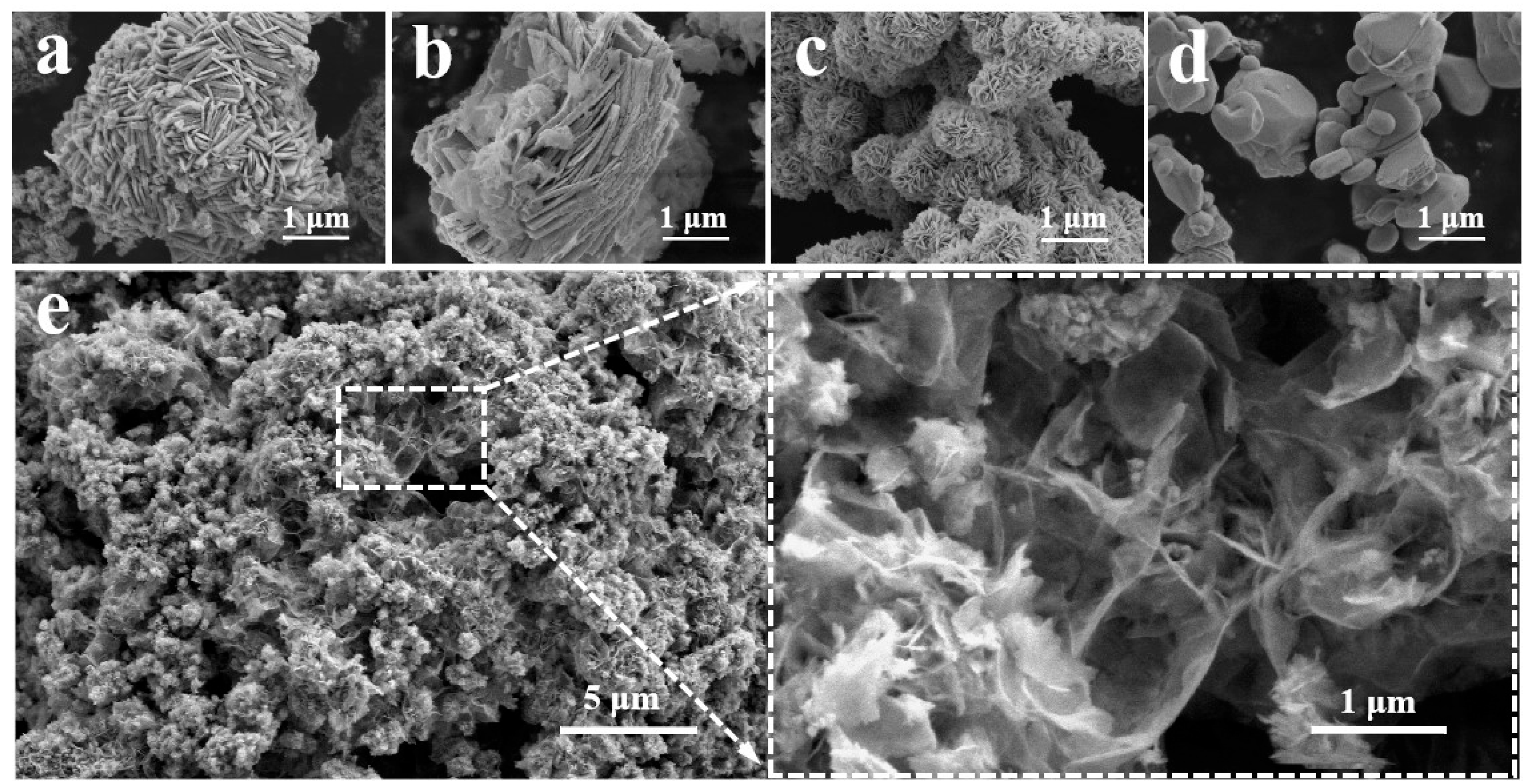

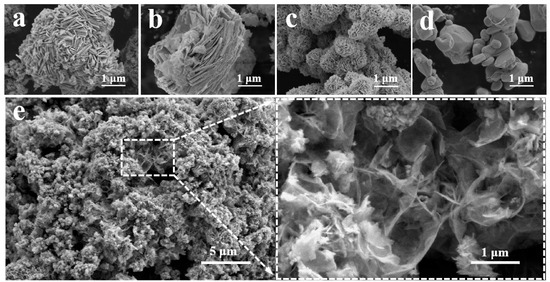

3.2. Photocatalyst Micromorphology and Structure

SEM was used to analyze the surface morphology, grain size, elemental composition distribution, and other structural characteristics of BiOBr, BiOI, BBI0.1, Bi2O3, and BO0.9−BBI0.1. As shown in Figure 3a, the BiOBr sample, successfully synthesized via the single-pot solvothermal method, exhibits an irregular 3D structure composed of densely stacked and convoluted BiOBr nanosheets, with a maximum diameter ranging from approximately 5.0 to 6.0 μm [16]. Figure 3b reveals that the synthesized BiOI possesses a structure resembling a rectangular cuboid, formed by the stacking and convolution of dense BiOI nanosheets. This structure features a concave front surface and side lengths of about 5.0 μm. In contrast, the BBI0.1 solid solution, also synthesized via the single-pot solvothermal method and shown in Figure 3c, demonstrates a distinct 3D flower-like spherical architecture composed of stacked and convoluted nanosheets. These spheres have diameters of approximately 0.8–1.0 μm and further aggregate into irregular shapes. This open and porous configuration creates more internal pores and channels, which significantly increases the specific surface area of the adsorbent-photocatalyst. The enhanced surface area promotes the adsorption of pollutant molecules and provides more active sites for photocatalytic reactions, thereby improving the overall degradation performance. The SEM image of the pure Bi2O3 material (Figure 3d) displays relatively smooth, non-angular 3D structures with irregular sizes and shapes, having diameters ranging from about 0.3 to 1.8 μm. As shown in Figure 3e, a significant morphological change occurred after constructing the heterojunction between BBI0.1 and Bi2O3 to form BO0.9−BBI0.1. The composite forms a 3D structure where Bi2O3 acts as a core, and its surface is densely covered with stacked and convoluted BBI0.1 nanosheets. This core–shell architecture creates an intimate interfacial contact between Bi2O3 and BBI0.1, facilitating efficient charge transfer across the heterojunction. Furthermore, the rough surface and increased porosity of the composite significantly expand the specific surface area and expose more active edges and facets. This structural optimization enhances light harvesting, improves pollutant adsorption capacity, and accelerates the surface redox reactions, collectively leading to the superior photocatalytic performance observed for BO0.9−BBI0.1 [17].

Figure 3.

SEM images of: (a) BiOBr; (b) BiOI; (c) BBI0.1; (d) Bi2O3 and (e) BO0.9−BBI0.1.

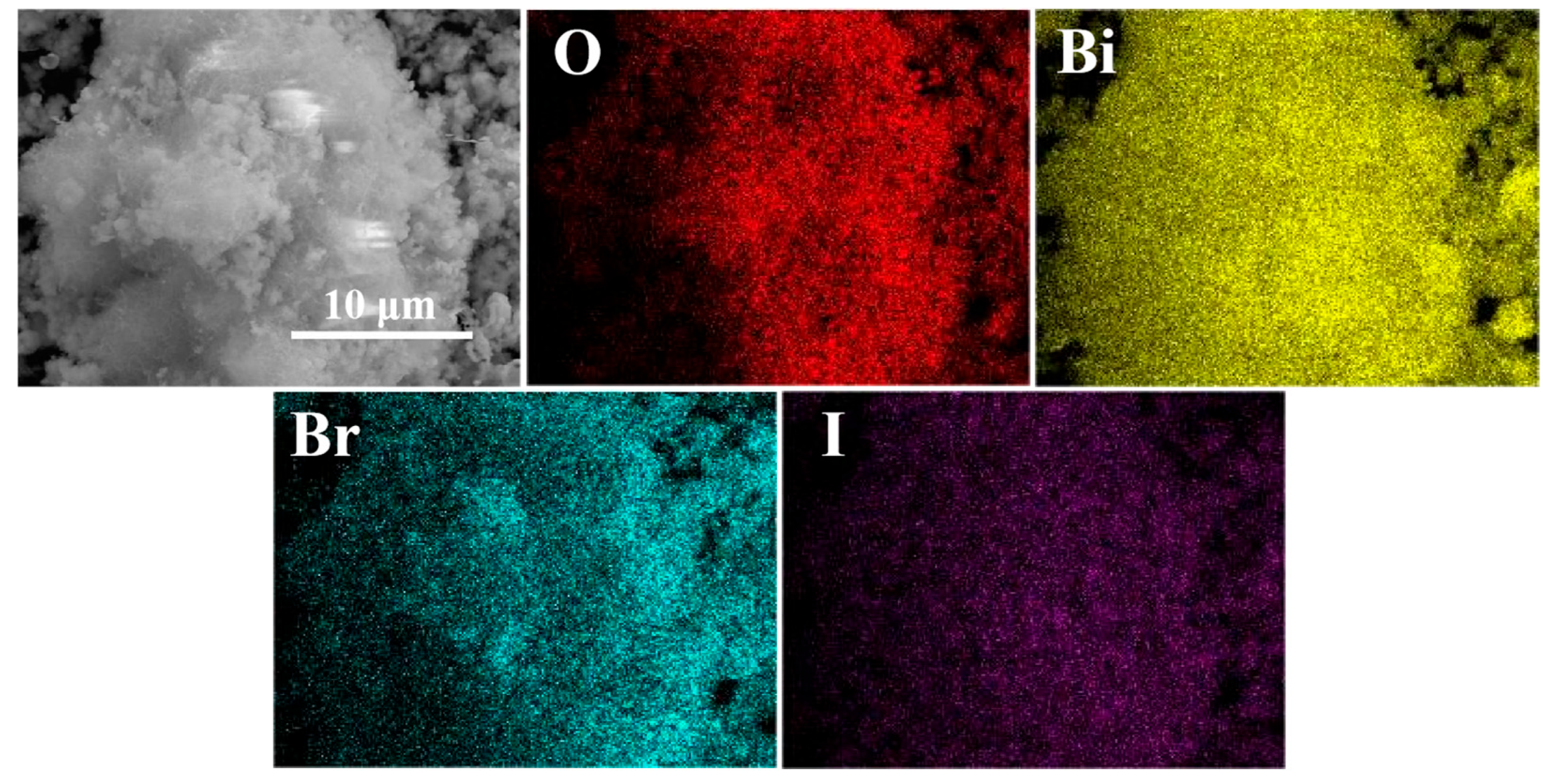

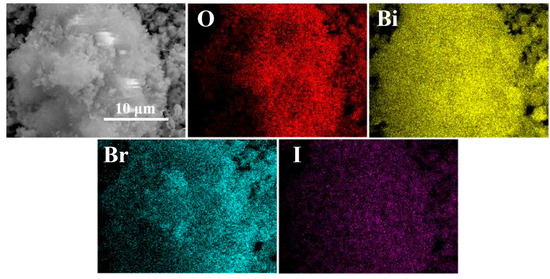

The spatial distribution and composition of elements in the BO0.9−BBI0.1 photocatalyst were determined by energy dispersive spectrometry (EDS). As shown in Figure 4, the elemental mapping results indicate that the BO0.9−BBI0.1 sample exhibits a 3D spherical morphology and is composed solely of O, Bi, Br, and I elements. All these elements are uniformly distributed throughout the spherical structure, providing strong evidence for the successful construction of the BO0.9−BBI0.1 material.

Figure 4.

EDS images of BO0.9−BBI0.1.

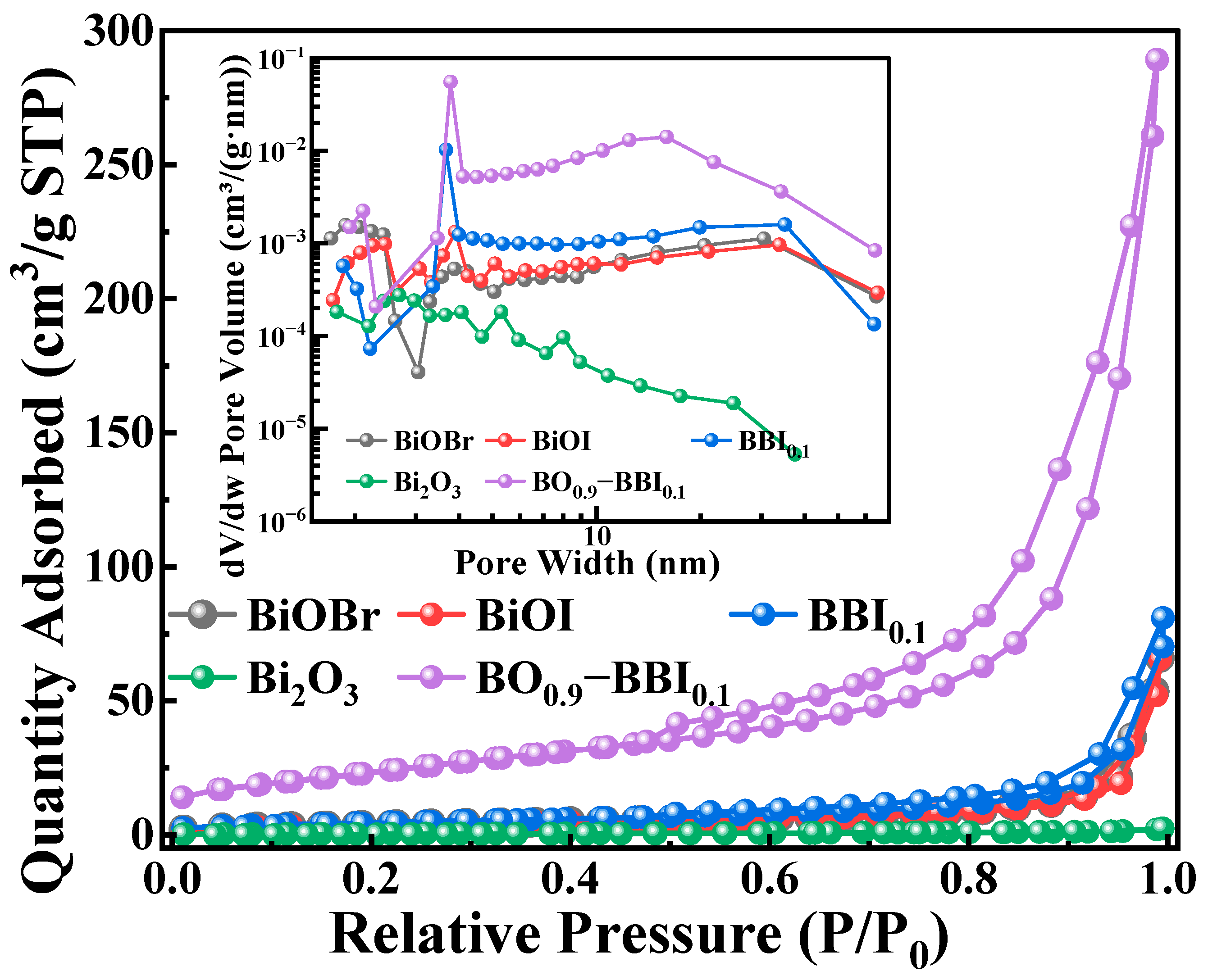

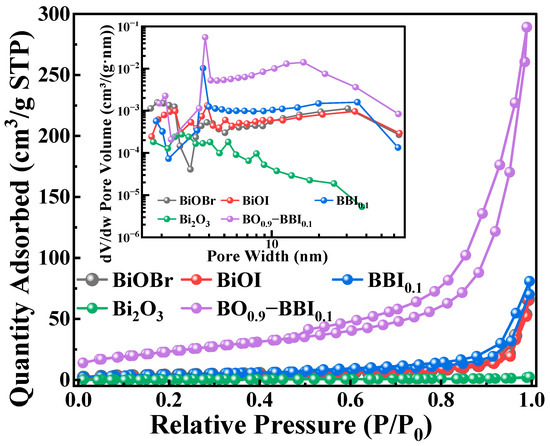

Specific surface area is important for materials. As shown in Table 1 and Figure 5, the pore size, pore volume, specific surface area, and adsorption performance of the synthesized BiOBr, BiOI, BBI0.1, Bi2O3, and BO0.9−BBI0.1 adsorbent-photocatalysts were thoroughly investigated using BET technique [18]. The closeness of the adsorption and desorption branches confirms the uniformity of the pore sizes.

Table 1.

BET data of BiOBr, BiOI, BBI0.1, Bi2O3, and BO0.9−BBI0.1.

Figure 5.

BET spectra of photocatalyst samples.

The results indicate that the Bi2O3 monomer exhibits weak adsorption performance, while BiOBr and BiOI show relatively similar adsorption capabilities. After constructing the solid solution structure from BiOBr and BiOI, the adsorption performance of BBI0.1 is enhanced compared to its individual counterparts. This suggests that forming the solid solution structure alters the morphology of the BiOX material, increases the specific surface area, and thereby enhances its adsorption capacity [19]. Furthermore, after constructing the heterojunction between BBI0.1 and Bi2O3, the adsorption performance of BO0.9−BBI0.1 is significantly improved compared to both BBI0.1 and Bi2O3. The average pore size of BO0.9−BBI0.1 is smaller than that of BiOBr, BiOI, and BBI0.1, which may be attributed to the tighter arrangement of nanosheets within the BO0.9−BBI0.1 material, consistent with the SEM analysis.

In summary, after the dual modification involving the construction of both the solid solution and heterojunction structures, the BO0.9−BBI0.1 material possesses a smaller average pore size, along with a larger specific surface area and pore volume, compared to BiOBr, BiOI, BBI0.1, and Bi2O3. This structural optimization increases the contact area between the material and the contaminated water body, provides more adsorption sites for pollutants, and consequently promotes the adsorption and degradation reactions of the pollutants [20].

3.3. Elemental Composition and Valence State Analysis

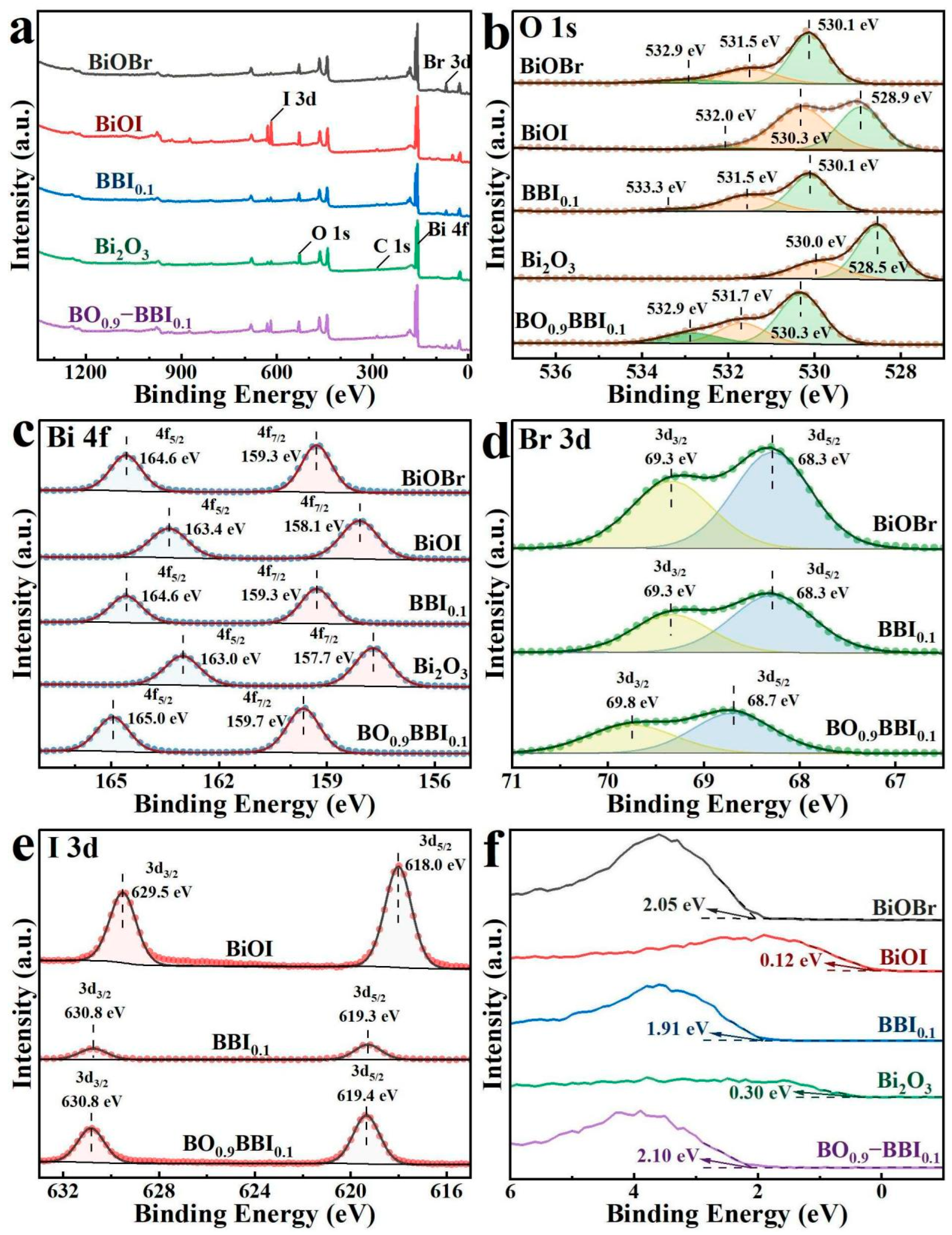

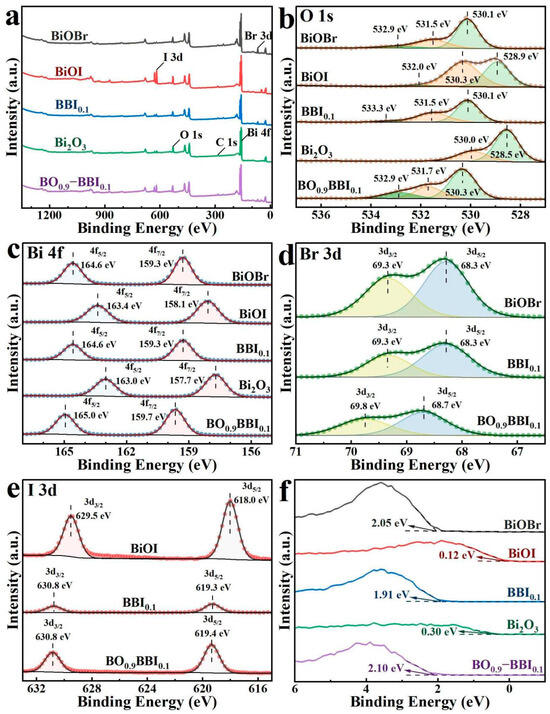

XPS was employed to detect the elemental composition, chemical environment, and surface electron interactions of the BiOBr, BiOI, BBI0.1, Bi2O3, and BO0.9−BBI0.1 samples, with the results shown in Figure 6. All XPS spectra were calibrated using the C 1s peak (284.80 eV) as a reference [5]. As shown in Figure 6a, the elements detected in the BiOBr, BiOI, BBI0.1, Bi2O3, and BO0.9−BBI0.1 samples correspond to their respective chemical compositions [21]. The observed C 1s signal originates from the XPS instrument itself [9,22].

Figure 6.

XPS spectra of BiOBr, BiOI, BBI0.1, Bi2O3, and BO0.9−BBI0.1: (a) Full spectrum; (b) O 1s; (c) Bi 4f; (d) Br 3d; (e) I 3d; (f) VB−XPS.

As shown in Figure 6b, the O 1s spectrum of Bi2O3 exhibits only two peaks at 530.0 eV and 528.5 eV, corresponding to Oads and Bi–O bonds [23], respectively. In contrast, the BiOBr, BiOI, BBI0.1, and BO0.9−BBI0.1 samples all display three fitted O 1s peaks. Specifically, for BO0.9−BBI0.1, the peaks located at 532.9 eV, 531.7 eV, and 530.3 eV are attributed to Oads, Bi–O bonds, and Br–O/I–O bonds, respectively [24].

The high-resolution Bi 4f spectra of BiOBr, BiOI, BBI0.1, Bi2O3, and BO0.9−BBI0.1 are presented in Figure 6c. All samples exhibit two characteristic binding energy peaks corresponding to Bi 4f7/2 and Bi 4f5/2, indicating that bismuth exists predominantly in the Bi3+ oxidation state across all materials. The binding energy of the Bi 4f peaks in BBI0.1 lies between those of BiOBr and BiOI. Meanwhile, the Bi 4f peaks of BO0.9−BBI0.1 show a slight shift toward higher binding energy compared to those of BBI0.1 and Bi2O3 [25].

Figure 6d displays the high-resolution Br 3d spectra. The results show that BiOBr, BBI0.1, and BO0.9−BBI0.1 all exhibit two binding energy peaks, assigned to Br 3d3/2 and Br 3d5/2, confirming that bromine is present in the −1 oxidation state in these samples. For BO0.9−BBI0.1, the Br 3d peaks are located at 69.8 eV and 68.7 eV, respectively, which are shifted to higher binding energies compared to those in BiOBr and BBI0.1 [26].

The high-resolution I 3d spectra are shown in Figure 6e. The results indicate that BiOI, BBI0.1, and BO0.9−BBI0.1 all exhibit two binding energy peaks corresponding to I 3d3/2 and I 3d5/2, suggesting that iodine exists as I− in these samples. For BO0.9−BBI0.1, the I 3d peaks are observed at 630.8 eV and 619.4 eV, respectively, which are shifted to higher binding energies compared to those in BiOI and BBI0.1 [27].

The maximum valence band (VB) potentials of the samples were measured using VB-XPS spectroscopy, with the results displayed in Figure 6f. The measured VB maximum potentials for BiOBr, BiOI, BBI0.1, Bi2O3, and BO0.9−BBI0.1 are 2.05 eV, 0.12 eV, 1.91 eV, 0.30 eV, and 2.10 eV, respectively. Compared to the oxidation potential of OH−/·OH (2.38 eV), the VB maximum potentials of all these samples are insufficiently positive, indicating that the photogenerated holes (h+) in these materials cannot directly oxidize H2O to generate ·OH radicals [5].

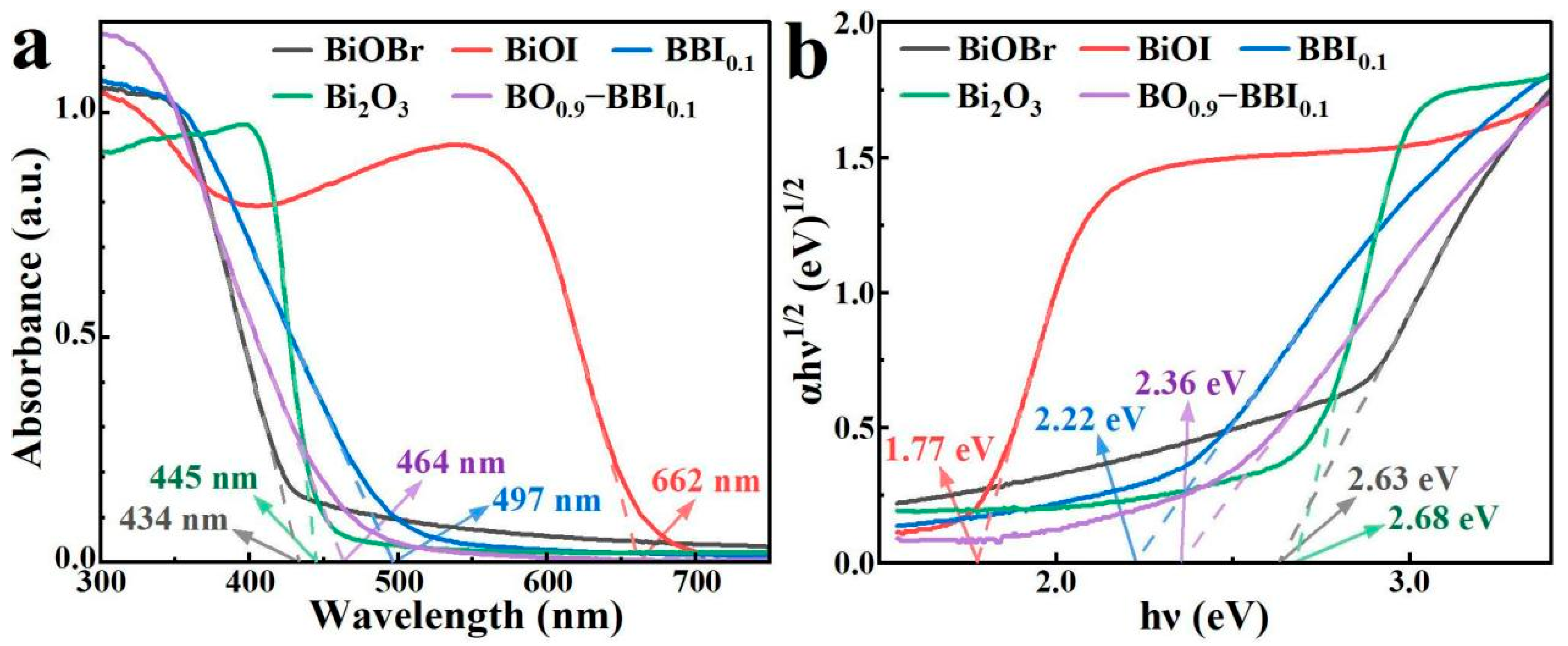

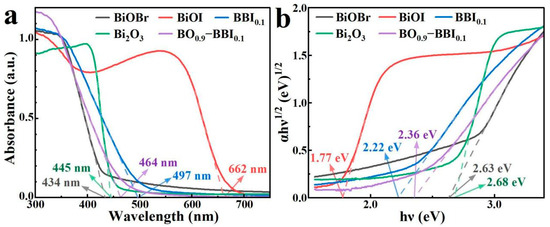

3.4. Photocatalytic Absorption Characteristics and Band Structure Analysis

As shown in Figure 7a, the light absorption properties and band gaps (Eg) of the BiOBr, BiOI, BBI0.1, Bi2O3, and BO0.9−BBI0.1 samples were investigated by UV-Vis DRS. The BiOI sample exhibits strong absorption across the visible light region, with high absorption intensity in the range of 200–600 nm and an absorption edge at approximately 662 nm. In contrast, the BiOBr sample shows a narrow light absorption range with an absorption edge around 434 nm. After constructing the solid solution structure, the BBI0.1 sample demonstrates light absorption performance intermediate between BiOBr and BiOI, possessing an absorption edge at about 497 nm.

Figure 7.

UV-Vis DRS (a) and Eg (b) spectra of BiOBr, BiOI, BBI0.1, Bi2O3, and BO0.9−BBI0.1.

The Bi2O3 sample also displays a relatively narrow light absorption range, with an absorption edge near 445 nm. Meanwhile, the BO0.9−BBI0.1 sample exhibits light absorption characteristics between those of BBI0.1 and Bi2O3, showing an absorption edge at approximately 464 nm. Therefore, constructing both solid solution and heterojunction structures can effectively modulate the light absorption range of the photocatalysts.

The (αhν)1/2–hν curves of the BiOBr, BiOI, BBI0.1, Bi2O3, and BO0.9−BBI0.1 samples, plotted according to the Kubelka-Munk function equation (indirect bandgap transitions, n = 2), are shown in Figure 7b. The bandgap energies (Eg) of BiOBr and BiOI are determined to be 2.63 eV and 1.77 eV, respectively. After constructing the solid solution structure, the Eg of the BBI0.1 sample is 2.22 eV, which lies between the values of BiOBr and BiOI. The Eg of the Bi2O3 sample is 2.68 eV. After forming the heterojunction between BBI0.1 and Bi2O3, the Eg of the BO0.9−BBI0.1 composite is 2.36 eV, intermediate between that of BBI0.1 and Bi2O3. These results demonstrate that constructing both solid solution and heterojunction structures can effectively modulate the bandgap energy of the photocatalysts, thereby altering their light absorption characteristics [28].

Additionally, the refractive index () of each sample was estimated using the empirical equation . The calculated values are: BiOBr (2.63 eV, ), BiOI (1.77 eV, ), BBI~0.1~(2.22 eV, ), Bi2O3 (2.68 eV, ), and BO~0.9~−BBI~0.1~(2.36 eV, ) [29]. The refractive index influences light penetration and scattering within the photocatalyst; a lower generally promotes deeper photon penetration and reduces surface reflection, thereby enhancing light utilization efficiency. The moderate refractive index of BO~0.9~−BBI~0.1~() suggests favorable light penetration characteristics compared to BiOI (), contributing to its superior photocatalytic performance. Similar correlations between refractive index and photocatalytic activity have been reported in recent studies on bismuth-based semiconductors.

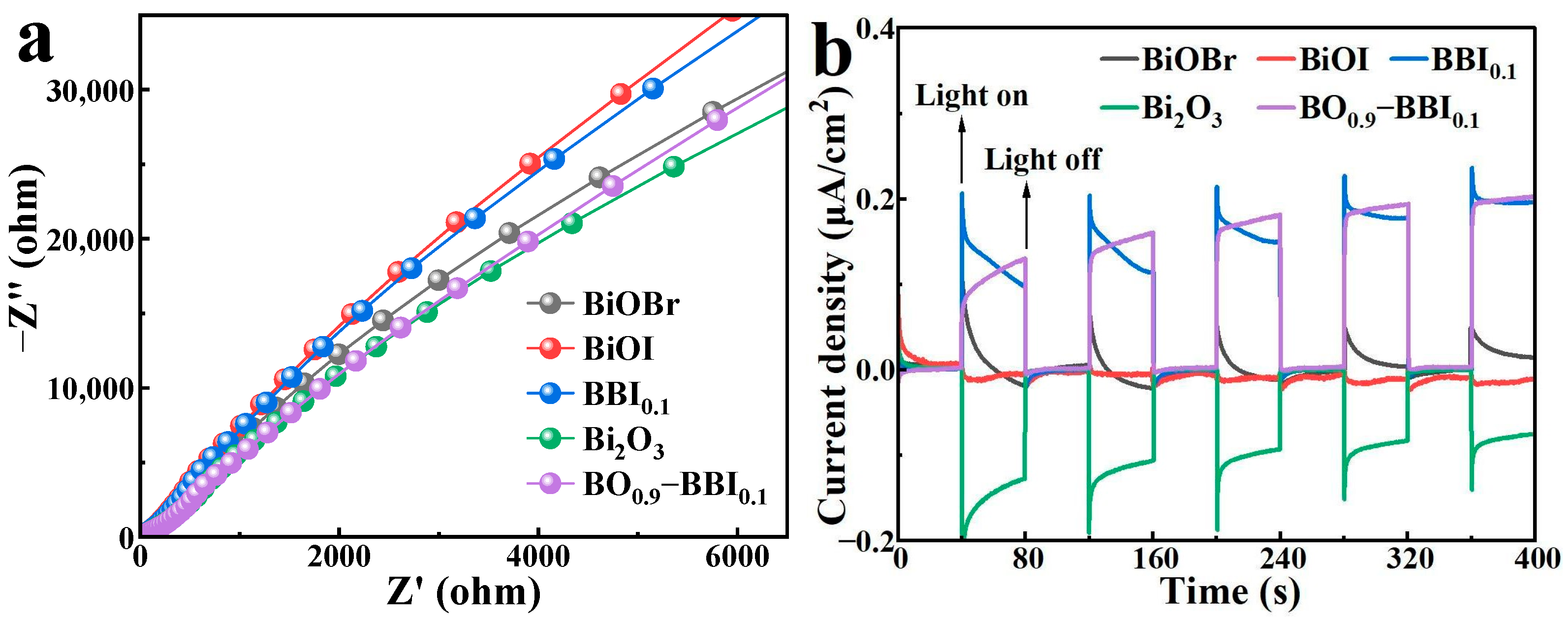

3.5. Photochemical Analysis

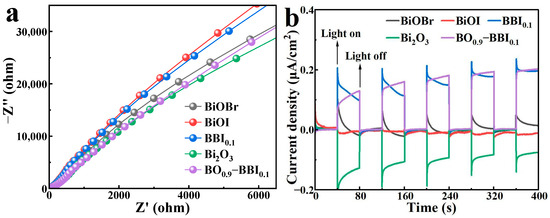

The EIS results for BiOBr, BiOI, BBI0.1, Bi2O3, and BO0.9−BBI0.1 are shown in Figure 8a. After constructing the solid solution structure from BiOBr and BiOI, the arc radius in the EIS Nyquist plot of BBI0.1 lies between those of BiOBr and BiOI. Furthermore, after forming the heterojunction between BBI0.1 and Bi2O3, the EIS arc radius of BO0.9−BBI0.1 is intermediate between those of BBI0.1 and Bi2O3, and is notably smaller than the radii of both BiOBr and BiOI. This indicates that constructing both solid solution and heterojunction structures can modulate the electrochemical impedance of the semiconductor structure, reduce the charge transfer resistance of photogenerated carriers, and thereby improve the light energy utilization efficiency of the photocatalyst [30].

Figure 8.

EIS (a) and photocurrent (b) spectra of BiOBr, BiOI, BBI0.1, Bi2O3, and BO0.9−BBI0.1.

The transient photocurrent responses of BiOBr, BiOI, BBI0.1, Bi2O3, and BO0.9−BBI0.1 are presented in Figure 8b. The transient photocurrent is generated when photogenerated electrons (e−) are excited from the valence band to the conduction band, creating electron-hole pairs (e−-h+), and the electrons migrate through the external circuit toward the counter electrode [31]. The BBI0.1 sample exhibits a higher transient photocurrent than both BiOBr and BiOI, indicating that constructing the solid solution structure increases the number of effective e−-h+ pairs and enhances the photocatalytic capability of the semiconductor material. After forming the heterojunction between BBI0.1 and Bi2O3, the transient photocurrent of BO0.9−BBI0.1 is comparable to that of BBI0.1, suggesting that BO0.9−BBI0.1 retains the photocatalytic capability inherent to BBI0.1. These results collectively demonstrate that constructing both solid solution and heterojunction structures can increase the quantity of effectively separated e−-h+ pairs, improve the light energy utilization efficiency of the photocatalyst, and consequently promote the photocatalytic degradation of pollutants.

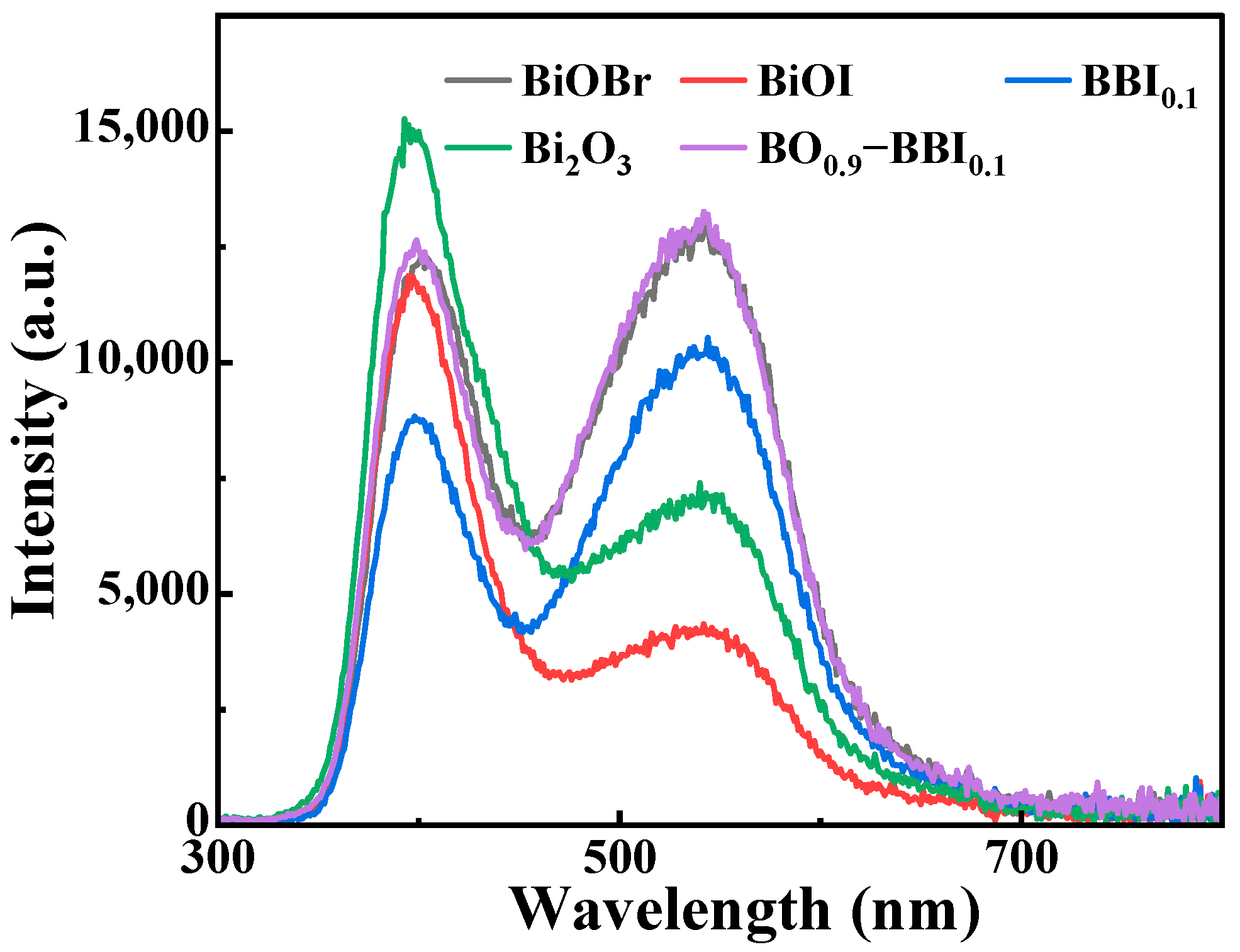

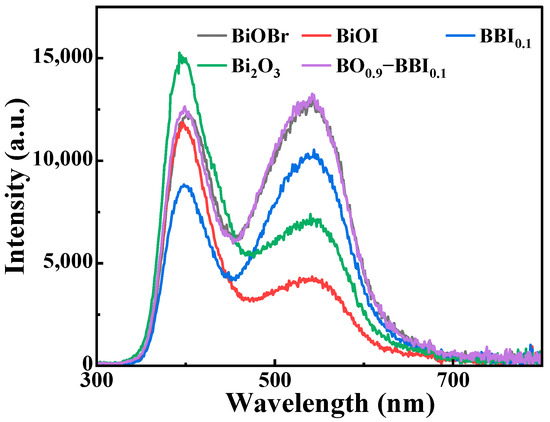

PL analysis was employed to investigate the separation and transfer efficiency of photogenerated electrons (e−) and holes (h+) in the semiconductor materials BiOBr, BiOI, BBI0.1, Bi2O3, and BO0.9−BBI0.1. As shown in Figure 9, the PL emission spectra of these samples within the range of 300–800 nm were recorded under an excitation wavelength of 255 nm. The PL peaks correspond to the energy released in the form of light during the recombination of e− and h+ pairs. By monitoring the light intensity at different wavelengths, the recombination rate of the e−-h+ pairs can be evaluated.

Figure 9.

PL spectra of BiOBr, BiOI, BBI0.1, Bi2O3, and BO0.9−BBI0.1.

Figure 9 compares the steady-state PL spectra of the samples, where the emission intensity is directly related to the recombination rate of photogenerated electron-hole pairs [6,31]. The significantly quenched PL intensity of BO0.9−BBI0.1 indicates a much lower charge carrier recombination rate compared to BiOBr, BiOI, and even the BBI0.1 solid solution. This provides direct spectroscopic evidence that the construction of the Z-scheme heterojunction between BBI0.1 and Bi2O3 effectively suppresses charge recombination, thereby increasing the population of long-lived charge carriers available for photocatalytic reactions [32].

3.6. Degradation Performance of Photocatalyst Samples

In order to evaluate the effect of solid solution and heterojunction construction on the performance of photocatalyst, photocatalytic degradation of 2,4-D was carried out using the prepared catalyst samples.

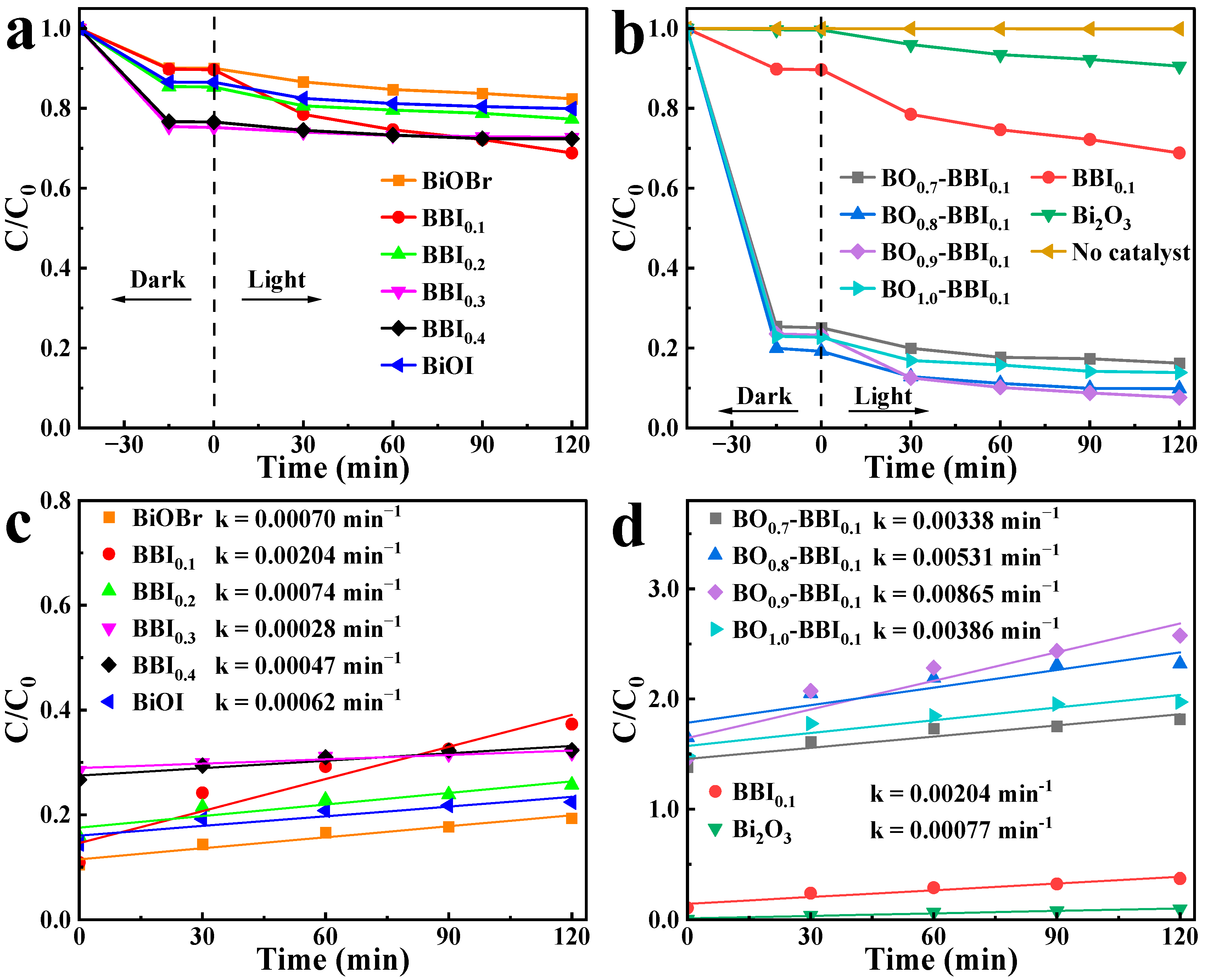

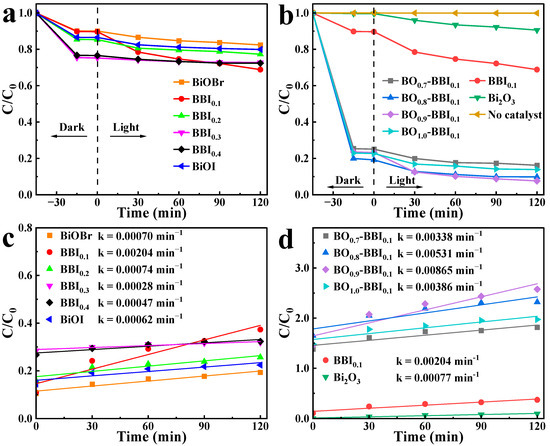

To evaluate the effect of solid solution composition (x in BBIx) and heterojunction content (z in BOz−BBI0.1) on photocatalytic performance, the degradation of 2,4-D was carried out under visible light. As shown in Figure 10a, the photocatalytic activity of the BBIx solid solutions exhibited a clear dependence on the Br/I ratio. The activity first increased with the introduction of I into BiOBr, reaching an optimum at BBI0.1, and then gradually decreased as the I content further increased toward pure BiOI. This “volcano-type” trend indicates an optimal halogen ratio for balancing light absorption and charge separation.

Figure 10.

2,4-D degradation curves under visible light (a,b) and quasi-first-order kinetic fitting (c,d) of BBIx, Bi2O3, and BOz−BBIx.

Subsequently, using the optimal BBI0.1 as the base, the influence of Bi2O3 content (z) was investigated. Figure 10b shows that the activity of the BOz−BBI0.1 composites displayed a similar trend. The degradation efficiency increased sharply with the initial incorporation of Bi2O3, peaked at the composition BO0.9−BBI0.1, and then declined for the sample with excessive Bi2O3 (z = 1.0, i.e., pure Bi2O3, which showed negligible activity). This demonstrates the existence of an optimal heterojunction ratio for maximizing interfacial charge transfer.

To analyze the photocatalytic degradation process more clearly, the pseudo-first-order kinetic model was applied to the 2,4-D removal data under light conditions. The calculated photocatalytic degradation rate constants (k) for BiOBr, BiOI, BBIx, Bi2O3, and BOz−BBI0.1 are shown in Figure 10c,d. The rate constants k for BiOBr and BiOI are 0.00070 min−1 and 0.00062 min−1, respectively. After constructing the solid solution structure, BBI0.1 exhibits the highest photocatalytic degradation efficiency among the BBIx samples, with a rate constant k of 0.00204 min−1. Following the construction of the heterojunction between BBI0.1 and Bi2O3, the BOz−BBI0.1 samples show further enhanced photocatalytic degradation rates for 2,4-D. Among them, BO0.9−BBI0.1 demonstrates the best photocatalytic performance within the BOz−BBI0.1 series, with a rate constant k of 0.00865 min−1. This value is approximately 4.2 times and 11.2 times higher than that of BBI0.1 and Bi2O3, respectively.

In summary, the construction of both solid solution and heterojunction structures enhances the adsorption and photocatalytic degradation efficiency of BiOBr and BiOI toward 2,4-D. BO0.9−BBI0.1 exhibits the best overall 2,4-D removal performance, with total removal efficiencies approximately 5.3 times and 4.6 times greater than those of BiOBr and BiOI, respectively.

The exceptional performance of BO0.9−BBI0.1 can be attributed to a synergistic combination of factors. First, its unique 3D hierarchical core–shell morphology (Figure 3e) provides a high specific surface area and porous structure, enhancing pollutant adsorption and providing abundant active sites, consistent with reports linking such morphologies to improved performance in bismuth-based composites. Second, the BiOBr0.9I0.1 solid solution effectively tunes the band gap (2.22 eV) and extends visible-light absorption (Figure 7a) [5]. Third, the Z-scheme heterojunction between BBI0.1 and Bi2O3 facilitates efficient separation of photogenerated charge carriers while preserving strong redox potentials, as evidenced by reduced electrochemical impedance (Figure 8a) and suppressed charge recombination (Figure 9), a mechanism widely reported to enhance photocatalytic efficiency. These combined structural and electronic optimizations explain the superior activity of BO0.9−BBI0.1 in degrading 2,4-D.

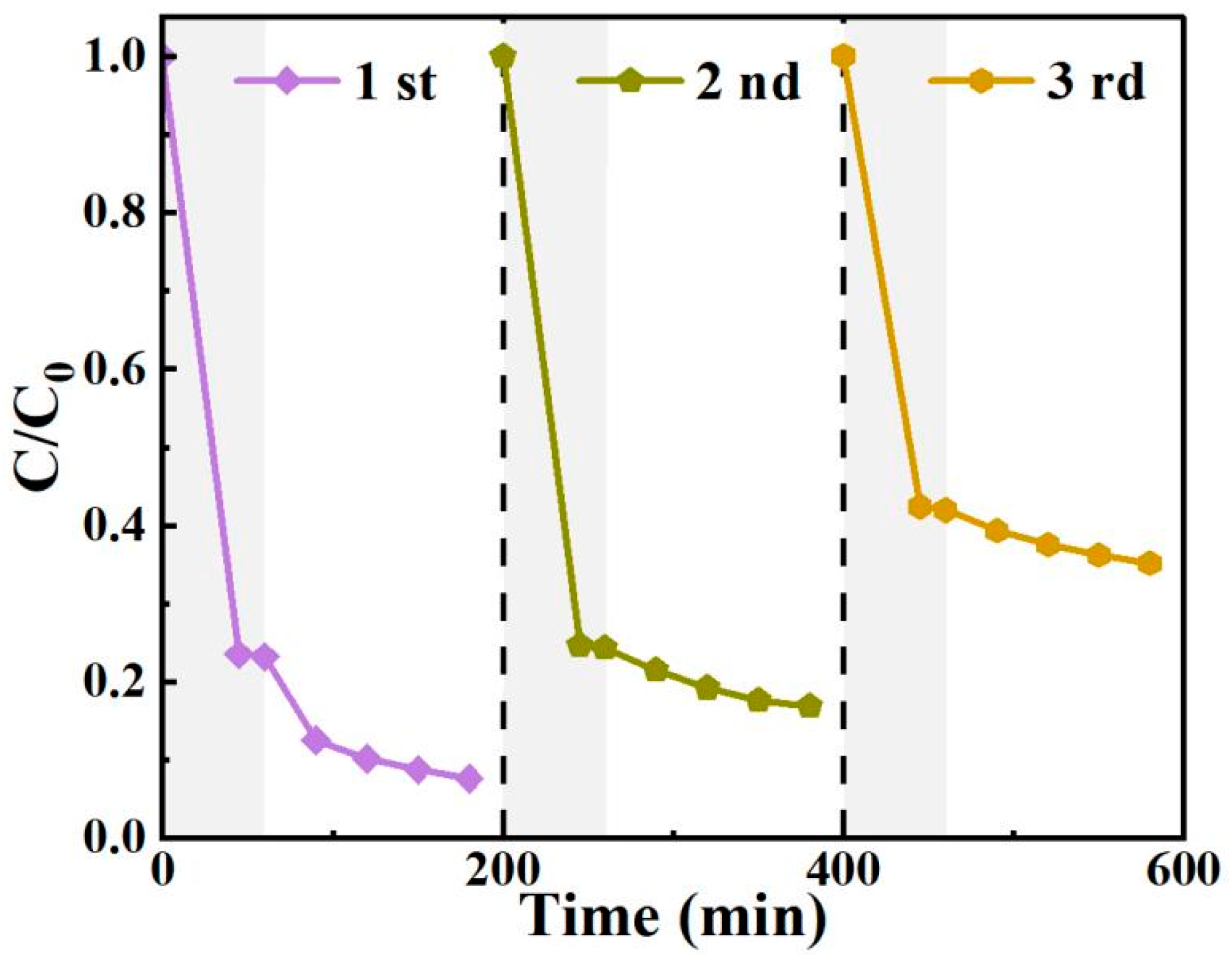

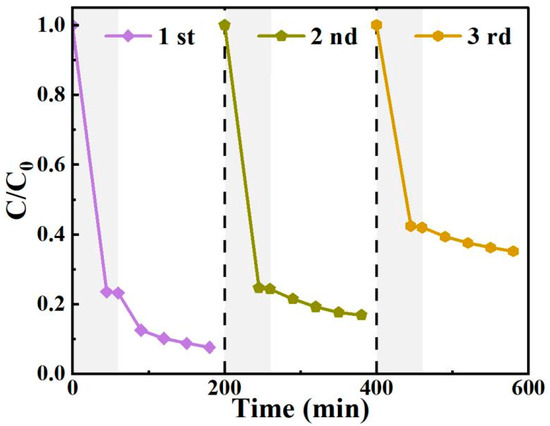

3.7. Photocatalyst Stability Analysis

High stability over multiple cycles of use is important for the practical application of a photocatalyst. As shown in Figure 11, three consecutive photocatalytic cycles were conducted to investigate the long-term reusability of BO0.9−BBI0.1. In the first cycle, the degradation rate of 2,4-D reached 92.4%. However, it decreased to 83.1% and 64.8% in the subsequent two cycles, respectively. During the third cycle, the recyclable removal efficiency for 2,4-D was unsatisfactory, with reductions observed in both adsorption and photocatalytic degradation performance. To analyze the reasons for this decline, the BO0.9−BBI0.1 sample after the third adsorption-photocatalytic test was collected, washed, dried, and subjected to further characterization.

Figure 11.

The cyclic degradation of 2,4-D by BO0.9−BBI0.1 under visible light.

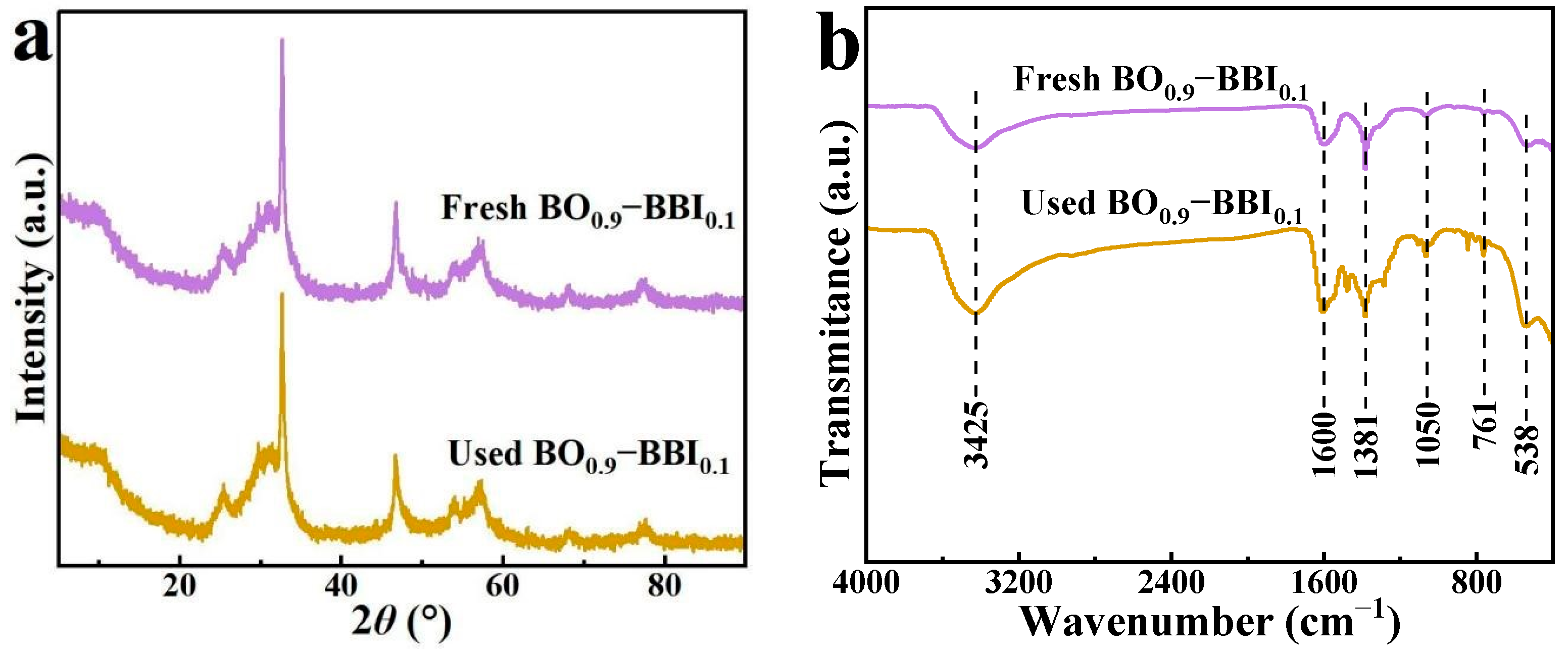

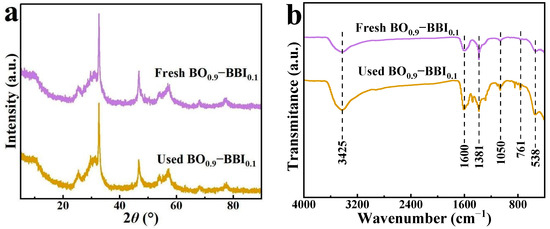

To evaluate the stability of the as-prepared BO0.9−BBI0.1 adsorbent-photocatalyst, the crystal structure and phase composition of the sample after three cycles of 2,4-D removal were analyzed. The crystal phase structure of BO0.9−BBI0.1 before and after cyclic use was examined by XRD, and the results are shown in Figure 12a. The XRD pattern of the as-prepared BO0.9−BBI0.1 exhibits relatively broad peaks, with the dominant crystal plane located at 2θ = 32.7°. No significant changes in the positions or intensities of the XRD peaks were observed for the sample after cyclic use compared to the fresh one.

Figure 12.

XRD patterns (a) and FT-IR spectra (b) of BO0.9−BBI0.1 before and after cycling.

The crystal phase and chemical structure of BO0.9−BBI0.1 before and after three cycles of use were analyzed by XRD and FT-IR, respectively. The XRD patterns (Figure 12a) show no shift or disappearance of characteristic peaks, confirming the robust crystallographic stability of the composite.

The FT-IR spectra (Figure 12b) provide further insight. For both fresh and used catalysts, the broad band around 3430 cm−1 and the peak at ~1600 cm−1 are ascribed to O–H stretching and bending vibrations of adsorbed water molecules. The absorption bands in the range of 400–760 cm−1, attributable to Bi–O and Bi–O–(Br/I) stretching vibrations, remain unchanged, reaffirming the integrity of the inorganic framework.

However, new bands emerge in the spectrum of the used catalyst at approximately 1381 cm−1 and 1050 cm−1. These features are not present in the fresh catalyst and are therefore unlikely to originate from the catalyst itself. Instead, they strongly suggest the adsorption of organic residues from the photocatalytic degradation of 2,4-D onto the catalyst surface [8,11].

The key conclusion from this combined XRD/FT-IR analysis is that the core crystal structure of BO0.9−BBI0.1 is chemically stable under the reaction conditions. The presence of adsorbed organic residues is a plausible explanation for the gradual decline in photocatalytic activity over multiple cycles (Figure 11), as these residues could partially block active sites or hinder light absorption. This is a common challenge in photocatalysis and underscores the need for regeneration protocols in practical applications.

The XRD and FT-IR results collectively indicate that the crystal structure and phase composition of the BO0.9−BBI0.1 sample remain unchanged after cyclic use.

3.8. Effects of Operational Parameters on Photocatalytic Performance

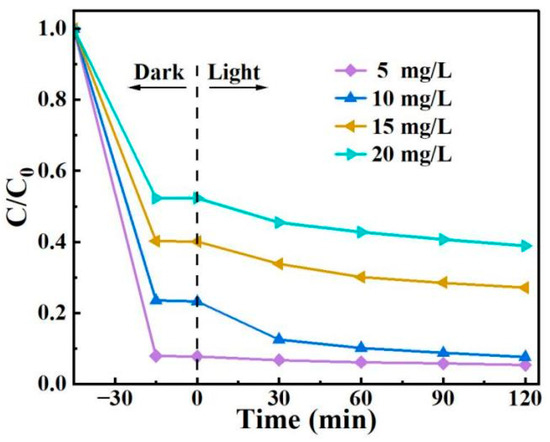

3.8.1. Effect of Initial 2,4-D Concentration

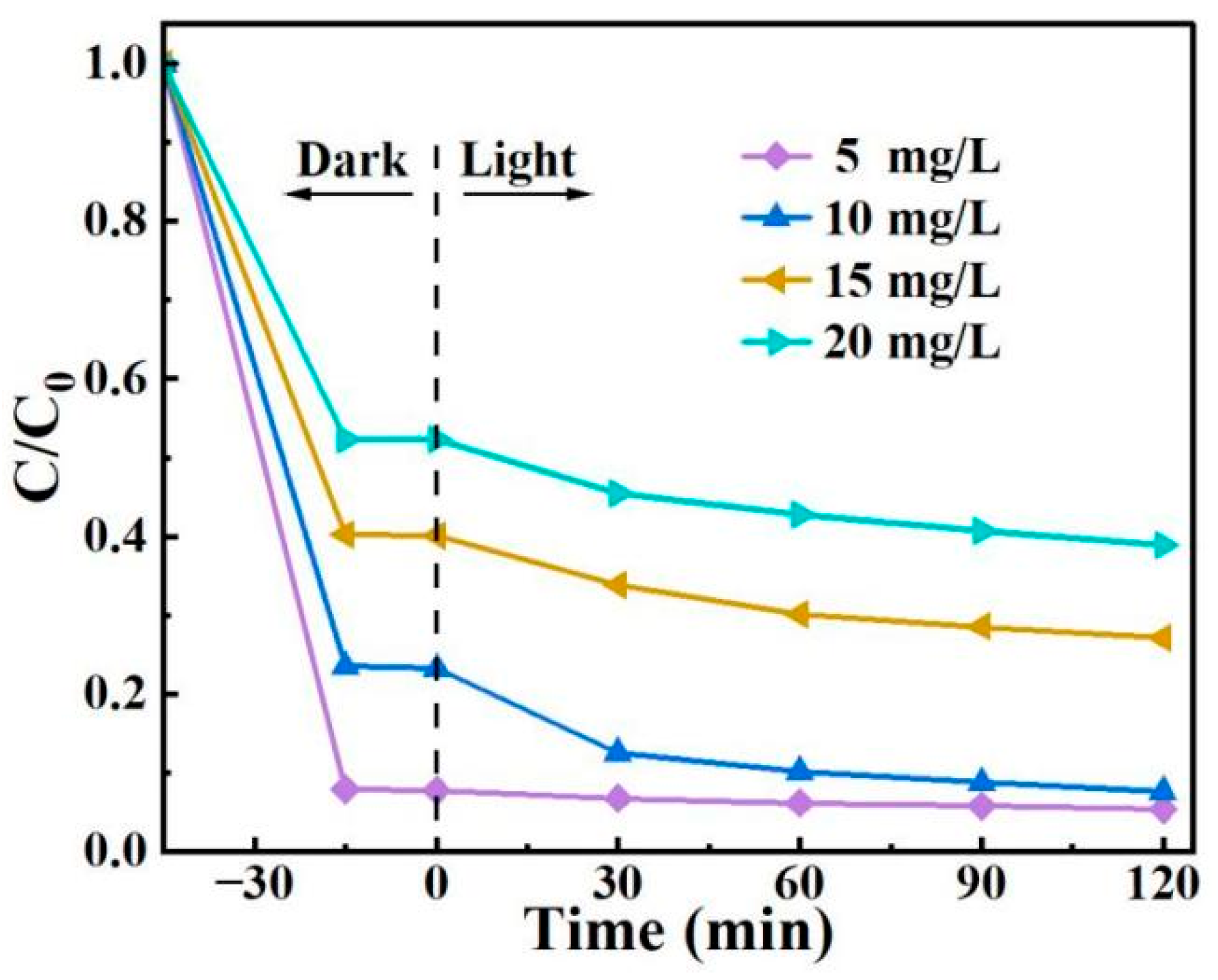

A series of 2,4-D solutions with concentrations of 5.0, 10, 15, and 20 mg/L (100 mL each) were prepared. With the addition of 15 mg of BO0.9−BBI0.1, the removal performance of the as-prepared material toward 2,4-D under different initial concentrations was tested. The results are shown in Figure 13. As the initial concentration of 2,4-D increased, the adsorption-photocatalytic removal efficiency of BO0.9−BBI0.1 decreased. When the initial concentration exceeded 10.0 mg/L, the removal rate declined significantly with increasing concentration. Considering both removal efficiency and economic cost, the system with an initial 2,4-D concentration of 10 mg/L and 15 mg of BO0.9−BBI0.1 showed the highest cost-effectiveness, achieving a total removal rate of 92.4%. Therefore, the optimal initial concentration of 2,4-D for the removal of 100 mL solution using 15 mg of BO0.9−BBI0.1 is around 10 mg/L.

Figure 13.

Effect of initial 2,4-D concentration on the adsorption-photocatalytic performance of BO0.9−BBI0.1.

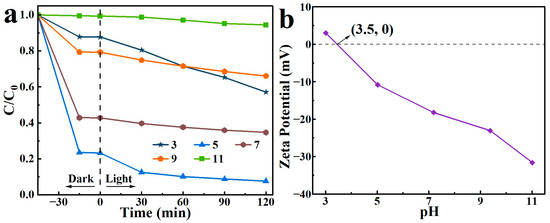

3.8.2. Effect of pH

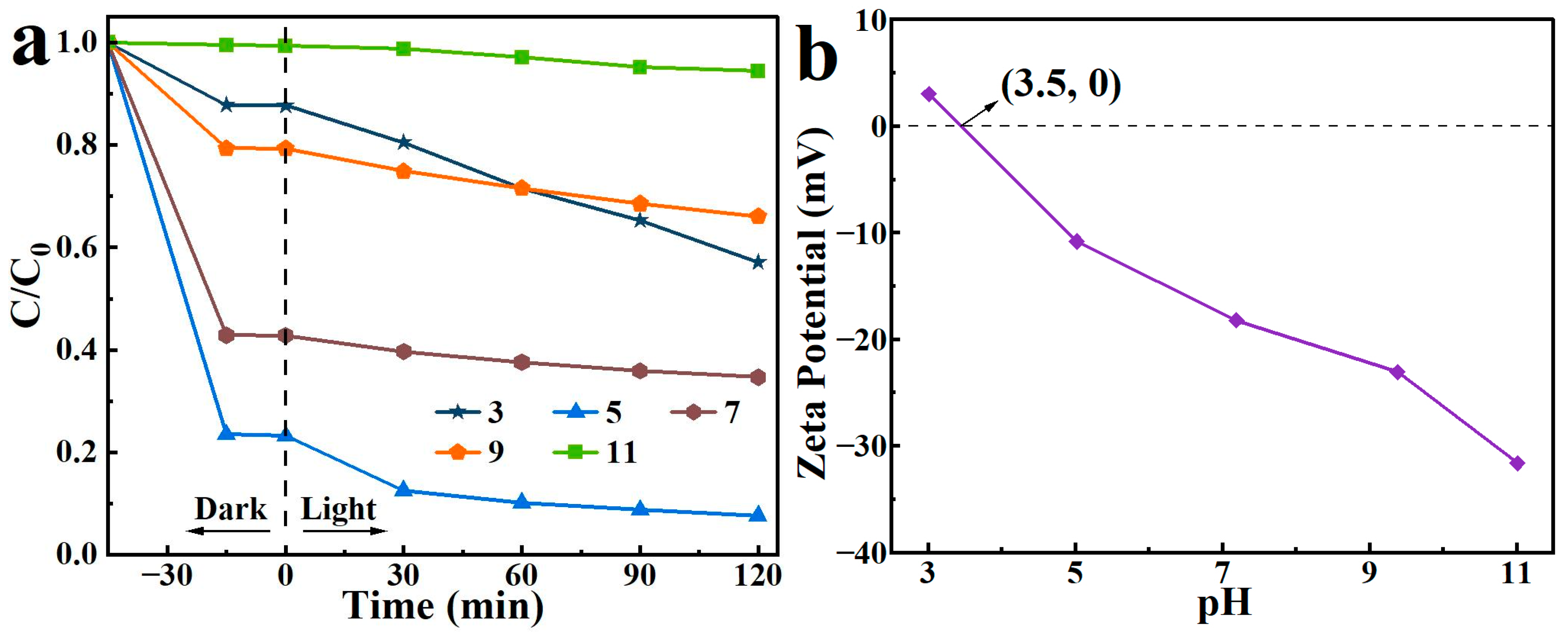

2,4-D solutions with pH values of 3, 5, 7, 9, and 11 were prepared. With the addition of 15 mg of the adsorbent-photocatalyst, the removal performance of the as-prepared BO0.9−BBI0.1 toward 2,4-D under different pH conditions was tested. The results are shown in Figure 14a. When the pH of the 2,4-D solution was 5, the adsorption-photocatalytic removal performance of BO0.9−BBI0.1 reached its highest level, with a total removal rate of 92.4%. When the pH exceeded 5, the removal efficiency gradually decreased with increasing pH. Therefore, the optimal pH condition for the adsorption-photocatalytic removal of 2,4-D by BO0.9−BBI0.1 is around pH 5.

Figure 14.

Effect of initial pH on the removal of 2,4-D by BO0.9−BBI0.1 (a) removal performance under different initial pH conditions; (b) zeta potential measurements as a function of pH.

Generally, the effect of pH on photocatalytic degradation depends on the type of pollutant and the zero-point charge (zpc) of the photocatalyst. In this study, the zeta potential results of BO0.9−BBI0.1, as shown in Figure 14b, indicate that the point of zero charge (pHzpc) of the material is 3.5. When pH < 3.5, the surface of BO0.9−BBI0.1 is predominantly positively charged, resulting in strong electrostatic repulsion with 2,4-D and consequently poor degradation efficiency. When pH > 3.5, the surface becomes predominantly negatively charged. As pH increases, the electrostatic repulsion with 2,4-D strengthens, leading to decreased degradation efficiency under alkaline conditions. In summary, at both higher and lower pH values, electrostatic repulsion between 2,4-D and the material reduces the adsorption-photocatalytic degradation efficiency.

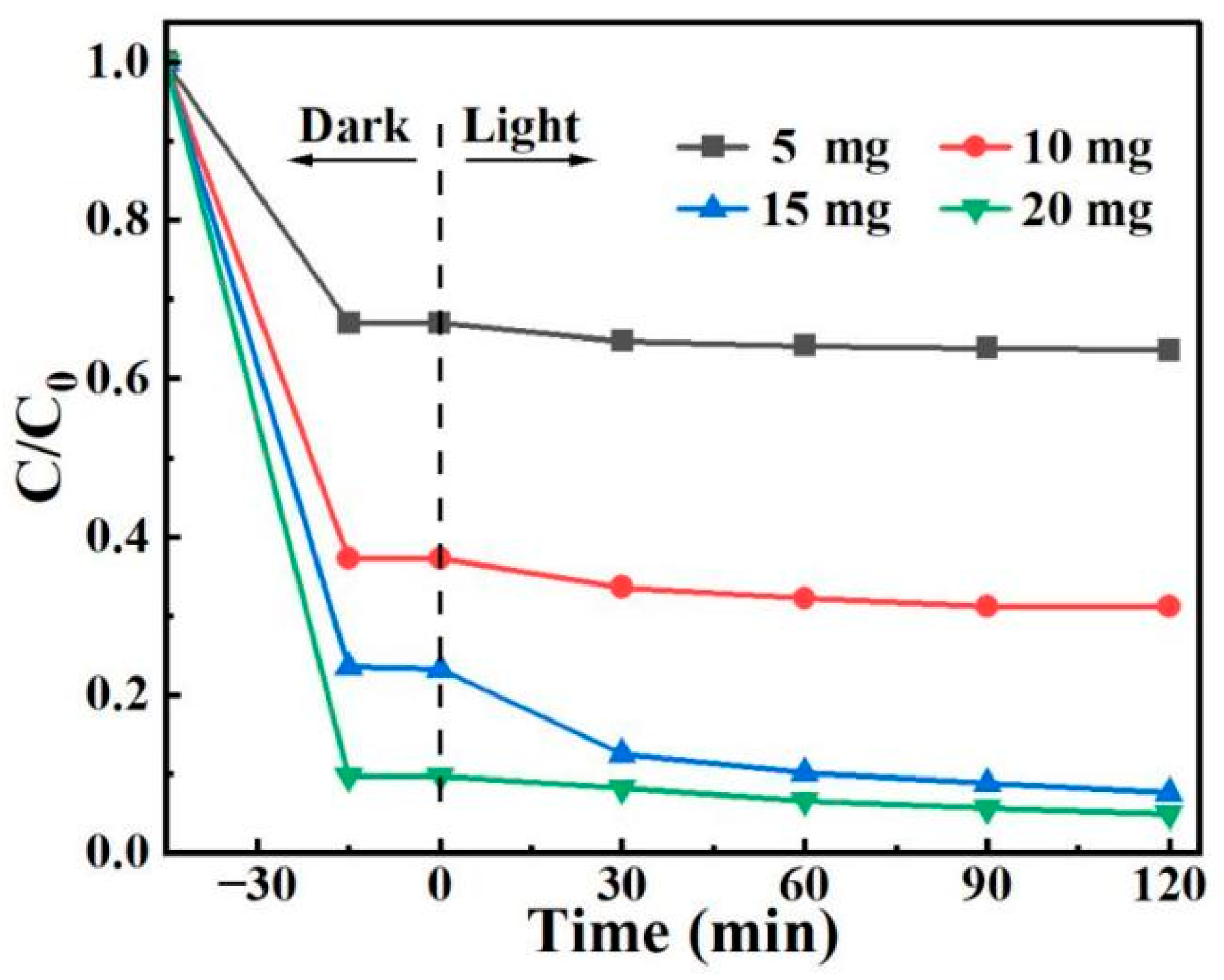

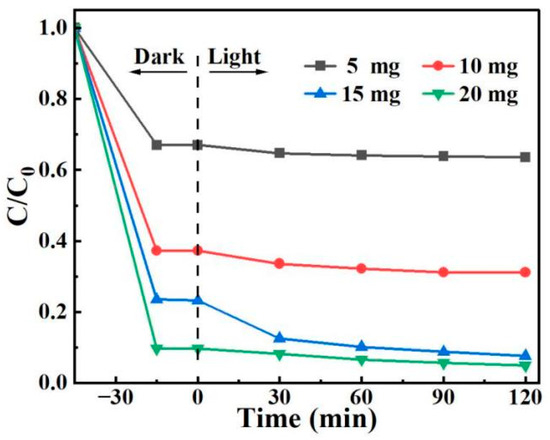

3.8.3. Effect of Adsorbent-Photocatalyst Dosage

A 100 mL solution of 10 mg/L 2,4-D was prepared, and varying amounts of BO0.9−BBI0.1 material (5, 10, 15, and 20 mg) were added separately to test the removal performance of the prepared BO0.9−BBI0.1 under different adsorbent-photocatalyst dosages. The results are shown in Figure 15. As the dosage of BO0.9−BBI0.1 increased, the adsorption-photocatalytic removal efficiency of 2,4-D improved. When the dosage exceeded 15 mg, the removal rate increased only slightly with further addition. Considering both economic cost and 2,4-D removal efficiency, a dosage of 15 mg of BO0.9−BBI0.1 achieved the highest cost-effectiveness, with a total removal rate of 92.4%. Therefore, the optimal dosage of BO0.9−BBI0.1 for the adsorption-photocatalytic removal of 100 mL of 10 mg/L 2,4-D is approximately 15 mg.

Figure 15.

Effect of BO0.9−BBI0.1 dosage on the removal of 2,4-D.

3.9. Reaction Mechanism Analysis

3.9.1. Main Active Substances

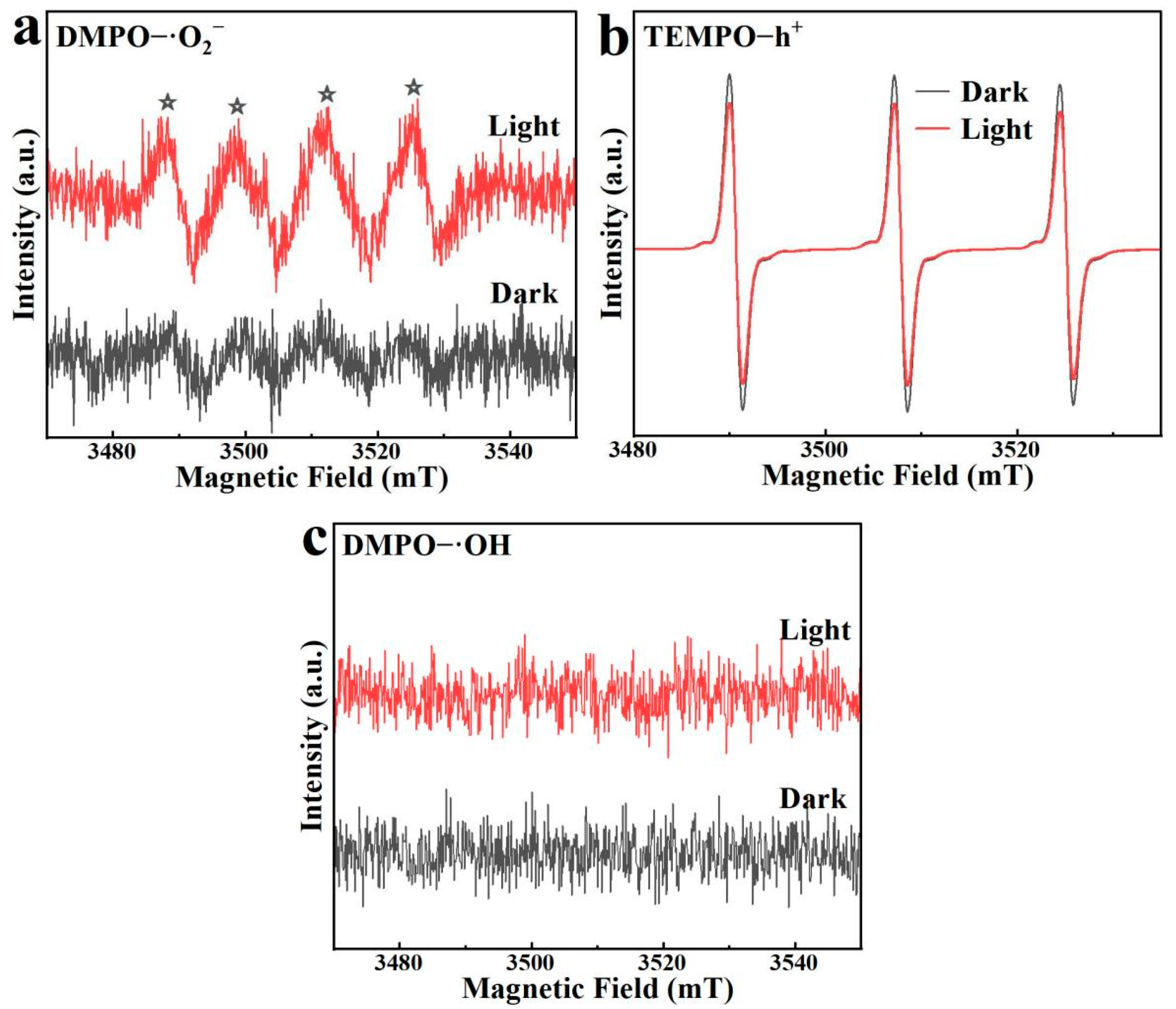

Using TEMPO and DMPO as radical trapping agents, the active species involved in the photodegradation process by BO0.9−BBI0.1 were determined via ESR, with the results shown in Figure 16. DMPO acts as a trapping agent for ·O2− and ·OH, while TEMPO is a trapping agent for h+. The ESR signals for DMPO−·O2− are shown in Figure 16a Under visible light irradiation, a characteristic quartet signal is observed, whereas no significant signals are detected in the dark, confirming the generation of ·O2− radicals [32].

Figure 16.

ESR spectra of BO0.9−BBI0.1: (a) DMPO−·O2− signals under light/dark; (b) TEMPO−h⁺ signals under light/dark; (c) DMPO−·OH signals under light/dark. The asterisks (*) indicate the characteristic peaks of DMPO–·O2− adducts.

The ESR signals for TEMPO−h+ are presented in Figure 16b. The trapping mechanism for h+ differs from that for hydroxyl or superoxide radicals; it is characterized by a reverse signal pattern. The three peaks correspond to the TEMPO trapping agent itself. Under light irradiation, the generated h+ in the material reacts with and consumes the TEMPO radicals, leading to a decrease in the signal intensity of the trapping agent. Thus, the weakened peak intensity after illumination indicates the production of photogenerated h+, and the difference between the two time points reflects the amount of h+ generated in the system. For BO0.9−BBI0.1, the TEMPO−h+ signal under visible light irradiation shows a significant reduction compared to that in the dark, indicating that illumination effectively produces a considerable amount of h+ for degrading 2,4-D.

The DMPO−·OH signals for BO0.9−BBI0.1 are shown in Figure 16c. No noticeable change in the DMPO−·OH signals is observed between light and dark conditions, indicating that no hydroxyl radicals are produced during the photocatalytic reaction of BO0.9−BBI0.1. Therefore, the primary active species in the photocatalytic degradation of 2,4-D by BO0.9−BBI0.1 are h+, with O2− serving as a secondary active species.

3.9.2. Reaction Mechanism

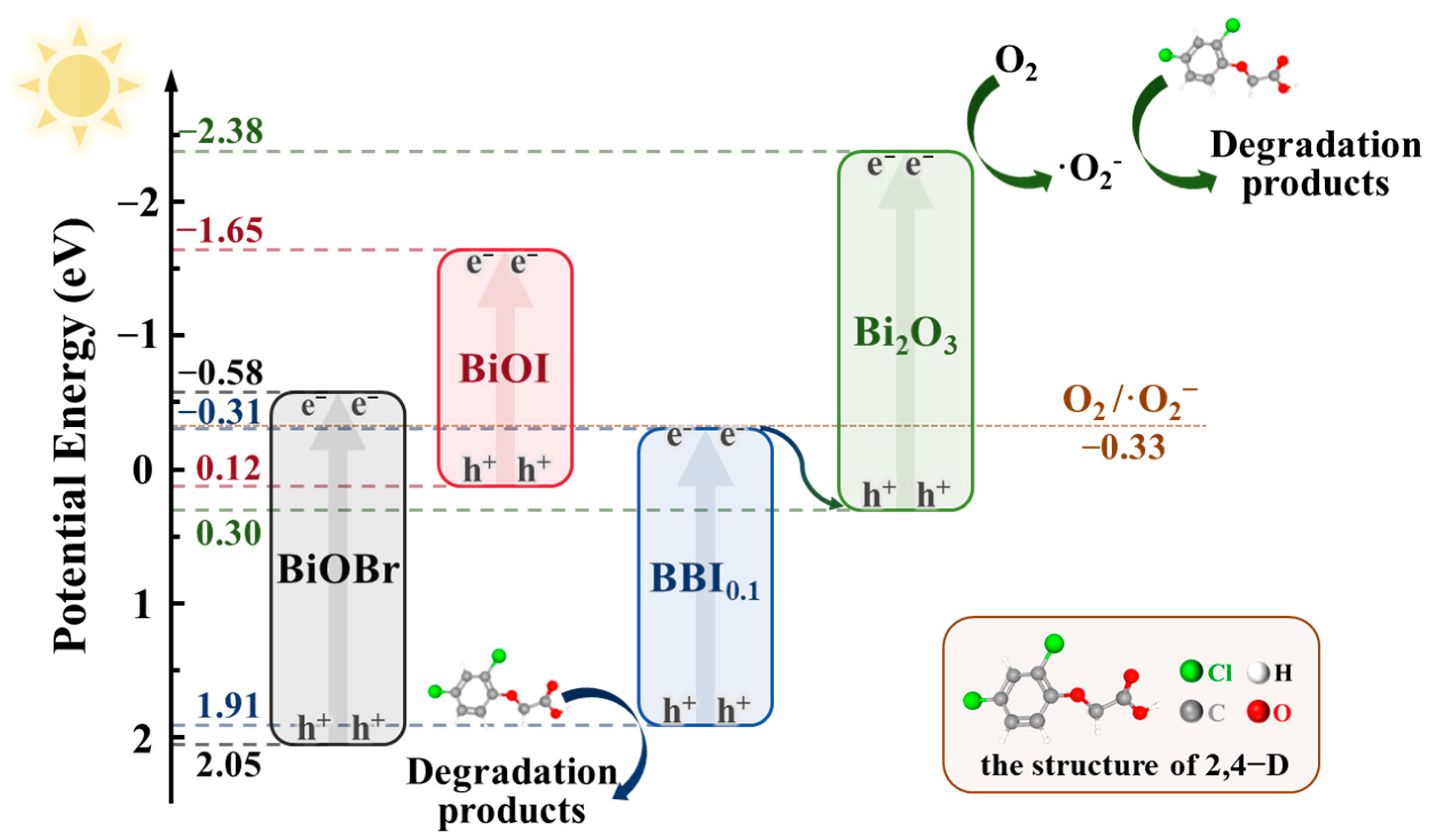

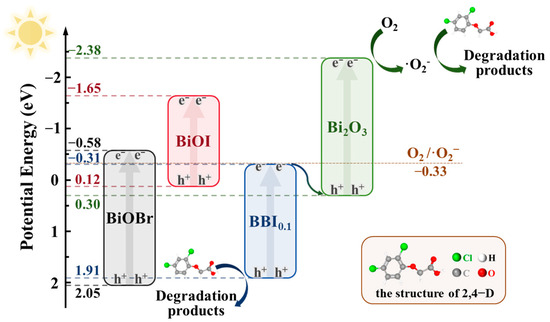

As shown in Figure 17, according to the analysis of active substances in the system, the preparation of a solid solution through mixing various halogens effectively regulated the Eg and broadened the range of light response while also improving the separation capability of photogenerated carriers, significantly extending the lifetime of photogenerated electron-hole pairs.

Figure 17.

Schematic diagram of the proposed photocatalytic mechanism of BO0.9−BBI0.1.

If a Type-II heterojunction were formed between BBI0.1 and Bi2O3 in the BO0.9−BBI0.1 material, the minimum potential would be that of BBI0.1 (–0.31 eV). Compared to the redox potential of O2/·O2− (–0.33 eV), this value is not sufficiently negative, indicating that the BO0.9−BBI0.1 material could not generate ·O2−. This contradiction with experimental results confirms that the junction between BBI0.1 and Bi2O3 is not a Type-II heterojunction.

If instead a Z-scheme heterojunction is formed between BBI0.1 and Bi2O3, the minimum potential would correspond to the conduction band of Bi2O3 (–2.38 eV), which satisfies the thermodynamic requirement for reducing O2 to ·O2−. Meanwhile, the maximum potential would be that of BBI0.1 (1.91 eV). Compared to the oxidation potential of OH−/·OH (2.38 eV), the valence band potential of BBI0.1 is not sufficiently positive, indicating that the photogenerated holes (h+) cannot directly oxidize H2O to produce ·OH. This band alignment is consistent with all the experimental characterization results.

4. Conclusions

The BO0.9−BBI0.1 composite, synthesized via a single-pot solvothermal method, possesses a well-developed porous structure. Compared to BiOBr and BiOI, BO0.9−BBI0.1 demonstrates a larger specific surface area, indicating that the construction of both solid solution and heterojunction structures influences the self-assembly process during the synthesis of BiOBr and BiOI, thereby enhancing the adsorption capacity of the material. BO0.9−BBI0.1 exhibits excellent performance in removing 2,4-D from aqueous solution, achieving a removal rate of 92.4% under conditions of 45 min of dark adsorption followed by 2 h of visible light irradiation. The degradation rate constant of BO0.9−BBI0.1 is approximately 5.3 and 4.6 times higher than that of BiOBr and BiOI, respectively. The primary active species responsible for the photocatalytic degradation of 2,4-D by BO0.9−BBI0.1 under visible light are h+ and ·O2−. The construction of solid solution and heterojunction structures effectively modulates the bandgap structure of BiOBr, altering the positions of the conduction and valence bands. This modulation allows electron excitation to occur under lower-energy light irradiation and efficiently suppresses the recombination of photogenerated e−-h+ pairs, thereby significantly enhancing the photocatalytic performance of the material.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.M. and G.Y.; methodology, R.M. and Y.Y.; software, B.L.; validation, Y.L., Y.Y. and Y.Z.; formal analysis, Y.Y. and R.M.; investigation, investigation, Y.L., Y.Z. and H.S.; resources, Y.C.; data curation, B.L.; writing—original draft preparation, R.M.; writing—review and editing, Y.Y. and G.Y.; visualization, Y.Y.; supervision, G.Y.; project administration, Y.C.; funding acquisition, G.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Guangxi Major Science and Technology Projects grant number AA23062054.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Rixiong Mo, Yuanzhen Li, Bo Liu, and Yaoyao Zhou were employed by the company CCCC Guangzhou Dredging Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Does Exposure to Environmental 2,4-Dichlorophenoxyacetic Acid Concentrations Increase Mortality Rate in Animals? A Meta-Analytic Review. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 303, 119179. [CrossRef]

- Developmental Toxicity of 2,4-Dichlorophenoxyacetic Acid in Zebrafish Embryos. Chemosphere 2017, 171, 40–48. [CrossRef]

- Vacca, A.; Mais, L.; Mascia, M.; Usai, E.M.; Rodriguez, J.; Palmas, S. Mechanistic Insights into 2,4-D Photoelectrocatalytic Removal from Water with TiO2 Nanotubes under Dark and Solar Light Irradiation. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 412, 125202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, F.; Wang, J.; Farooq, M.A.; Khan, M.S.S.; Xu, L.; Zhu, J.; Zhao, M.; Muños, S.; Li, Q.X.; Zhou, W. Potential Impact of the Herbicide 2,4-Dichlorophenoxyacetic Acid on Human and Ecosystems. Environ. Int. 2018, 111, 332–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, G.; Yang, Y.; Wang, S.; Yu, Z.; Sun, Q.; Li, Y.; Sun, J.; Ling, T.; Shu, Z. Preparation of Bi2O2CO3/BiOBr0.9I0.1 Photocatalyst and Its Degradation Performance for 2,4-Dichlorophenoxyacetic Acid. J. Alloys Compd. 2023, 952, 169835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.-Y.; Zhang, X.; Yu, H.-Q. Bismuth Oxyhalide Photocatalysts for Water Purification: Progress and Challenges. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2023, 493, 215339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Chen, K.; Niu, B.; Li, Y.; Wang, L.; Huang, J.; She, H.; Wang, Q. Preparation of BiOCl0.9I0.1/β-Bi2O3 Composite for Degradation of Tetracycline Hydrochloride under Simulated Sunlight. Chin. J. Catal. 2020, 41, 1535–1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, H.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Cheng, M.; Wang, W.; Song, B.; Luo, H.; Qin, D.; Huang, C.; Qin, F.; et al. Insight into FeOOH-Mediated Advanced Oxidation Processes for the Treatment of Organic Polluted Wastewater. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 453, 139812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, G.; Sun, Q.; Yang, Y.; Chen, S.; Long, Y.; Li, Y.; Ge, S.; Zheng, D. BiOCl-Based Composites for Photocatalytic Degradation of Antibiotics: A Review of Synthesis Method, Modification, Factors Affecting Photodegradation and Toxicity Assessment. J. Alloys Compd. 2024, 981, 173733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murti, R.H.A.; Jawwad, M.A.S.; Ayuningtiyas, K.K.; Hidayah, E.N. High Efficiency on Resin Photocatalysis: Study on Application and Kinetic Mechanism Using Langmuir Hinshelwood Model. S. Afr. J. Chem. Eng. 2025, 53, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ighalo, J.O.; Ojukwu, V.E.; Umeh, C.T.; Aniagor, C.O.; Chinyelu, C.E.; Ajala, O.J.; Dulta, K.; Adeola, A.O.; Rangabhashiyam, S. Recent Advances in the Adsorptive Removal of 2,4-Dichlorophenoxyacetic Acid from Water. J. Water Process Eng. 2023, 56, 104514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, J.; Xiao, Y.; Ren, M. Direct Hydrolysis Synthesis of BiOI Flowerlike Hierarchical Structures and It’s Photocatalytic Activity under Simulated Sunlight Irradiation. Catal. Commun. 2014, 45, 30–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Wu, J.; Jia, T.; Li, T.; Wang, Z.; Qi, Y.; Liu, Q.; Qi, X.; He, P. Fabrication of BiOI Nanosheets with Exposed (001) and (110) Facets with Different Methods for Photocatalytic Oxidation Elemental Mercury. Colloid Interface Sci. Commun. 2021, 40, 100357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.-Y.; Zeng, Q.; Zhu, G. Novel S-Doped BiOBr Nanosheets for the Enhanced Photocatalytic Degradation of Bisphenol A under Visible Light Irradiation. Chemosphere 2021, 268, 128854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, J.; Zhang, T.; Jiang, T.; Wu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Tahir, M.; Hussain, A.; Luo, M.; Zou, J.; Wang, X. Fast Preparation of Oxygen Vacancy-Rich 2D/2D Bismuth Oxyhalides-Reduced Graphene Oxide Composite with Improved Visible-Light Photocatalytic Properties by Solvent-Free Grinding. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 328, 129651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BiOBr Nanoflakes with Engineered Thickness for Boosted Photodegradation of RhB Under Visible Light Irradiation—ScienceDirect. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0925838823009167 (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Shu, S.; Wang, H.; Li, Y.; Liu, J.; Liu, J.; Yao, J.; Liu, S.; Zhu, M.; Huang, L. Fabrication of N-p β-Bi2O3@BiOI Core/Shell Photocatalytic Heterostructure for the Removal of Bacteria and Bisphenol A under LED Light. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2023, 221, 112957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousefi, A.; Nezamzadeh-Ejhieh, A. Characterization of BiOCl/BiOI Binary Catalyst and Its Photocatalytic Activity towards Rifampin. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2022, 433, 114135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, D.; Liang, F.; Xue, Q.; Liu, Y.; Zhuang, C.; Li, S. Interfacial Engineering of Cd0.5Zn0.5S/BiOBr S-Scheme Heterojunction with Oxygen Vacancies for Effective Photocatalytic Antibiotic Removal. Acta Phys. -Chim. Sin. 2025, 41, 100190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, J.; Yang, W.; Liu, J.; Sun, K.; Liu, L.; Fu, F. Enhancing an Internal Electric Field by a Solid Solution Strategy for Steering Bulk-Charge Flow and Boosting Photocatalytic Activity of Bi24O31ClxBr10–x. Chin. J. Catal. 2022, 43, 485–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Mao, J.; Yin, D.; Zhang, T.; Liu, C.; Hao, W.; Wang, Y.; Hao, J. Synergy of S-Vacancy and Heterostructure in BiOCl/Bi2S3−x Boosting Room-Temperature NO2 Sensing. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 455, 131591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, A.; Peng, D.; Sun, Z.; Tan, Z.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Q. Dual-S-Scheme 3D Ag2CO3/BiOI/BiOCl Microsphere Heterojunction for Improving Photocatalytic Mercury Removal. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 2023, 164, 107599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Gao, Y.; Sui, Z.; Dong, Z.; Wang, S.; Zou, D. Hydrothermal Synthesis of BiOBr/FeWO4 Composite Photocatalysts and Their Photocatalytic Degradation of Doxycycline. J. Alloys Compd. 2018, 732, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Yang, C.; He, Y.; Zhong, J.; Li, J.; Zhu, Y. Oxygen Vacancies Facilitated Photocatalytic Detoxification of Three Typical Contaminants over Graphene Oxide Surface Embellished BiOCl Photocatalysts. Adv. Powder Technol. 2023, 34, 103971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, C.; Cheng, H.; Fan, R.; Sun, J.; Liu, X.; Ji, Y. Fabrication of rGO/BiOI Photocathode and Its Catalytic Performance in the Degradation of 4-Fluoroaniline. Heliyon 2024, 10, e37024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Wang, D.; Liu, J.; Wang, L.; Wang, H.; Wang, S.; Wu, B.; Liu, M. γ-PGA-Dependent Growth of BiOBr Nanosheets with Exposed {010} Facets for Enhanced Photocatalytic RhB Degradation. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2025, 688, 162446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Nie, H.; Kong, B.; Xu, X.; He, F.; Wang, W. Enhanced Visible-Light Photocatalytic Activity of BiOBr/BiOCl Heterojunctions: A Hybrid Density Functional Investigation on the Key Roles of Crystal Facet and I-Doping. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 51, 733–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalauni, D.P.; Jaiswal, K.N.; Lawaju, S.; Rai, K.B.; Yadav, R.J.; Mishra, A.D.; Ghimire, M.P. Electronic and Optical Properties of Halogen-Substituted LaBi2Cl1-yXyO4: A Promising Candidate for Energy-Efficient Devices. RSC Adv. 2025, 15, 35930–35940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balarabe, B.Y.; Kanafin, Y.N.; Rustembekkyzy, K.; Serkul, I.; Nauryzbaeva, M.A.; Atabaev, T.S. Assessing the Photocatalytic Activity of Visible Light Active Bi2S3-Based Nanocomposites for Methylene Blue and Rhodamine B Degradation. Mater. Today Catal. 2025, 9, 100099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.-Y.; Zhang, X.; Qiu, H.-B.; Wang, W.-K.; Huang, G.-X.; Jiang, J.; Yu, H.-Q. Photocatalytic Degradation of Bisphenol a by Oxygen-Rich and Highly Visible-Light Responsive Bi12O17Cl2 Nanobelts. Appl. Catal. B 2017, 200, 659–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Bao, T.; Li, S.; Li, X.; Rao, H.; Cheong, W.-C.; She, P.; Qin, J.-S. Facilitated Charge Separation Induced by Ni-Doping in Hollow Z-Scheme Heterojunction for Photocatalytic Coupling Benzylamine Oxidation with Hydrogen Evolution. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2025, 266, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, H.-T.; Huynh, N.-D.-T.; Luan, V.-H.; Chang, Y.-H.; Le, M.-V. Facile One-Pot Synthesis of 3D Hollow Microspheres BiOBr/Bi2S3 with Oxygen Vacancies for Enhanced Photocatalytic Removal of Tetracycline and Rhodamine B. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2025, 690, 162587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.