Abstract

This paper addresses the problem of high fine particle content in the overflow and insufficient separation efficiency of traditional cyclone clarifiers. A cyclone clarifier with a spiral guide groove is proposed. A comparative numerical simulation analyzes the flow field characteristics and separation performance inside traditional and spiral guide groove cyclone clarifiers. Comparing the flow fields shows that the spiral guide groove increases tangential velocity at the inlet, centrifugal force increases, axial velocity decreases, separation time increases, and separation efficiency improves. The spiral guide groove forces the fluid to follow an optimized path. It reduces circulating flows and vortices. The flow field becomes more uniform and stable. In the cone-plate region, streamlines are dense and axial velocity is low. This favors particle settling. In the underflow region, turbulent kinetic energy and the interaction between inner and outer vortices decrease. This reduces the number of particles entering the overflow pipe with the inner vortex. Compared to the traditional cyclone clarifier, the spiral guide groove cyclone clarifier effectively improves particle removal efficiency. The removal efficiency increases by 6.8%. The improvement effect varies for different particle sizes. The removal efficiency improvement is greatest for 15–20 μm particles. It effectively improves the water quality of the overflow outlet.

1. Introduction

Coal mining produces significant amounts of mine water, which commonly contains suspended solids such as rock powder and sediment [1]. Direct discharge of such water without prior treatment leads to contamination of adjacent soil and water systems. Utilizing mine water through recycling offers a twofold benefit: it mitigates environmental pollution while also supplying an alternative water resource, which contributes to relieving regional water scarcity and promoting sustainable economic development [2,3,4]. To comply with effluent or reuse criteria, conventional treatment techniques such as sedimentation, filtration, neutralization, and disinfection are widely implemented [5,6,7,8,9]. However, these approaches often require substantial land area and involve high infrastructure costs. More importantly, their efficiency remains limited, and performance tends to be inadequate when dealing with large volumes of mine water that contain high levels of solids [10,11,12,13].

A hydrocyclone is an efficient device that uses centrifugal force for mixture separation. It is widely used in mining, chemical and environmental protection, and petroleum fields. It has a simple structure, small size, and high separation efficiency. Cui Baoyu et al. [14,15] used numerical simulation and extensive experiments. They found that as the hydrocyclone cone angle increases, the buoyancy force on solid particles inside the flow field increases accordingly. Liu Peikun [16] used a parabolic hydrocyclone for more efficient particle separation. Experiments proved that the internal flow field of the parabolic hydrocyclone is more stable. Flow field disorder reduces, decreasing coarse and fine particle mixing. Zhang Ting et al. [17] addressed the unstable flow field in hydrocyclones. They added a central cone inside the hydrocyclone. This proved that the flow field in a hydrocyclone with a central cone is more stable. The central cone structure enhances the overall performance of the hydrocyclone. Addressing the problem of coarse particles in the overflow due to short-circuit flow, Ghodrat et al. [18] studied a variable-diameter overflow pipe structure. Yang Xinghua et al. [19] proposed a honeycomb cone hydrocyclone. Experimental verification showed that both effectively suppress short-circuit flow. They improve the classification accuracy of the overflow. But the overflow still contains many particles.

An inclined tube settler is a solid–liquid separation device. It uses the shallow depth sedimentation principle. It adds parallel inclined plates or honeycomb inclined tubes to the sedimentation tank to improve particle settling efficiency [20,21]. For inclined tube settlers, Wang Keyuan et al. [22,23] set multi-layer tube arrangements. They studied the effect of arrangement on sediment settling. Research shows inclined tubes mainly settle with low-concentration, fine sediment. The double-layer tube arrangement has the best uniformity of water and particle distribution. The outlet sediment content is the lowest. Hirom et al. [24] investigated inlet-offset, outlet-offset, and center-offset configurations of inclined plates. They found that the outlet-offset position was most effective for improving the settlement efficiency of the sedimentation tank. It was also observed that within a certain range, the settlement efficiency increased with the number of inclined plates, beyond which the efficiency decreased rapidly.

Hydrocyclones are suitable for high-speed, high centrifugal force conditions. They are generally used for the primary treatment stage of mine water. After cyclone treatment, the particle content in mine water remains high. Inclined tube settlers have good treatment effects on mine water. But their treatment efficiency is low. They occupy a large area. They are difficult to build in underground coal mines. The integration of hydrocyclones with inclined settling structures to form composite separators has been validated in early studies. Castilho & Medronho [25] proposed a geometrically similar hydrocyclone design framework, which laid the theoretical foundation for integrating settling–enhancing components (e.g., cone-plates) into hydrocyclones. Building on this framework, Yang et al. [26] developed a traditional cone-plate cyclone clarifier prototype and verified its fine particle separation performance in mine water through experiments—this prototype is the direct existing design basis for the traditional structure in this study. Zhang et al. [27] further optimized the cone-plate radius parameter of this prototype, confirming that the equal-proportional, gradually shrinking cone-plate structure can improve particle removal efficiency by 10.32%, which provides a key reference for the cone-plate parameter design. Dianyu et al. [28] demonstrated via numerical simulation that a spiral inlet with a 4° inclination angle reduces particle misplacement by 12% and improves separation efficiency for 10–30 μm particles, directly supporting the parameter selection of the spiral guide groove; Zhao et al. [29] proposed an integrated compact-bend cyclone, proving that curved inlet structures similar to spiral guides can enhance particle separation efficiency by up to 22.7%, confirming the effectiveness of such guide structures in cyclone inlet modification; Liu Peikun et al. [30] proposed the adoption of a helical-blade hydrocyclone to tackle the issue of fine particle entrainment in the underflow. Their research findings revealed that helical blades help enhance the separation precision of fine particles and reduce the cut size—providing a supplementary reference for the structural parameter optimization of the spiral guide components.

In recent years, numerical simulation has played a significant role in cyclone separator research. The Reynolds-Averaged Navier-Stokes equations (RANS) approach is widely adopted due to its good balance between accuracy and computational efficiency. Corrêa et al. [31] recently applied a hybrid URANS-LES model to cyclone separators. Their study showed that RANS alone can satisfactorily reproduce mean flow behavior. Alves de Moro Martins et al. [32] used LES to study interparticle collisions. Their work confirmed the importance of coupling turbulence and particle dynamics. Wasilewski et al. [33] compared multiple turbulence models. They demonstrated that RANS effectively captures flow anisotropy in industrial cyclones. Zhang et al. [34] demonstrated improvements in predicting particle collection efficiency using RANS-based flow redistribution techniques. Shukla et al. [35] highlighted the influence of velocity fluctuation modeling on collection efficiency, supporting the robustness of RANS formulations. Furthermore, numerical simulation through computational fluid dynamics (CFD) can simulate cyclone behavior under various operating conditions. CFD predicts key performance metrics such as separation efficiency, pressure drop, and particle distribution. These simulations help improve separation efficiency and reduce energy consumption [36,37]. Rhodes et al. [38] applied CFD to study the flow motion inside cyclone separators. This marked the first application of computational fluid dynamics in cyclone research. Schuetz et al. [39] made advances in comprehensive numerical studies of 3D hydrocyclones using CFD. They indicated that future work would extend to higher particle concentrations and different hydrocyclone configurations.

This paper proposes a new design for a spiral guide groove cyclone clarifier. The traditional cyclone clarifier improves separation efficiency through cyclone separation and cone-plate settling. Adding the spiral guide groove at the inlet makes the fluid flow along the groove upon entry. The fluid rotates multiple times along the spiral guide groove before entering the cone-plate area. This increases particle separation time. The small pitch of the spiral guide groove can increase the velocity at the inlet. This paper establishes 3D models for both cyclone clarifiers. It compares separation performance through numerical simulation. This can analyze particle separation mechanisms. It effectively provides technical guidance for optimizing mine water treatment processes. It has corresponding theoretical and practical significance.

2. Numerical Modeling and Feasibility Verification

2.1. Geometric Structure

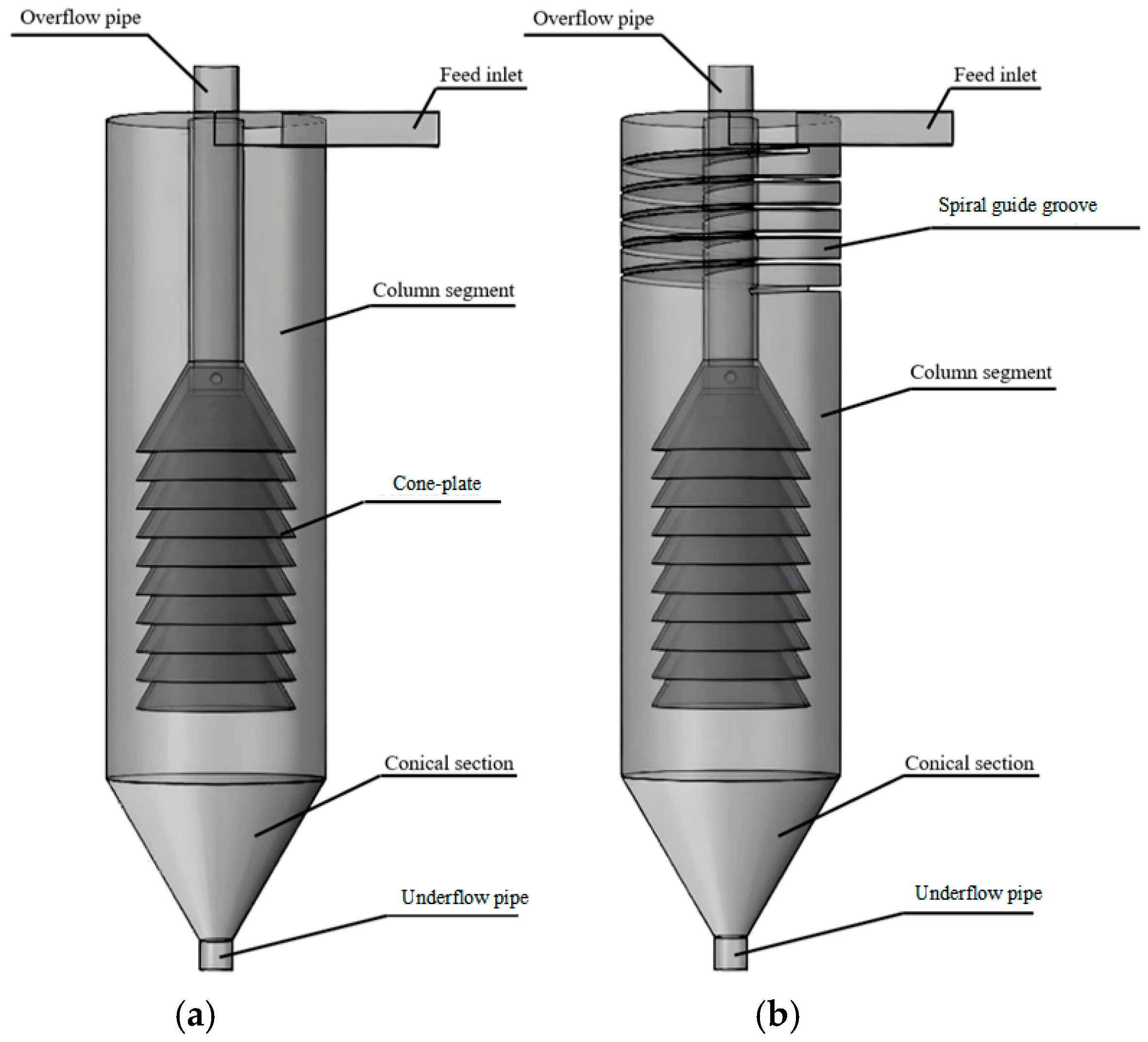

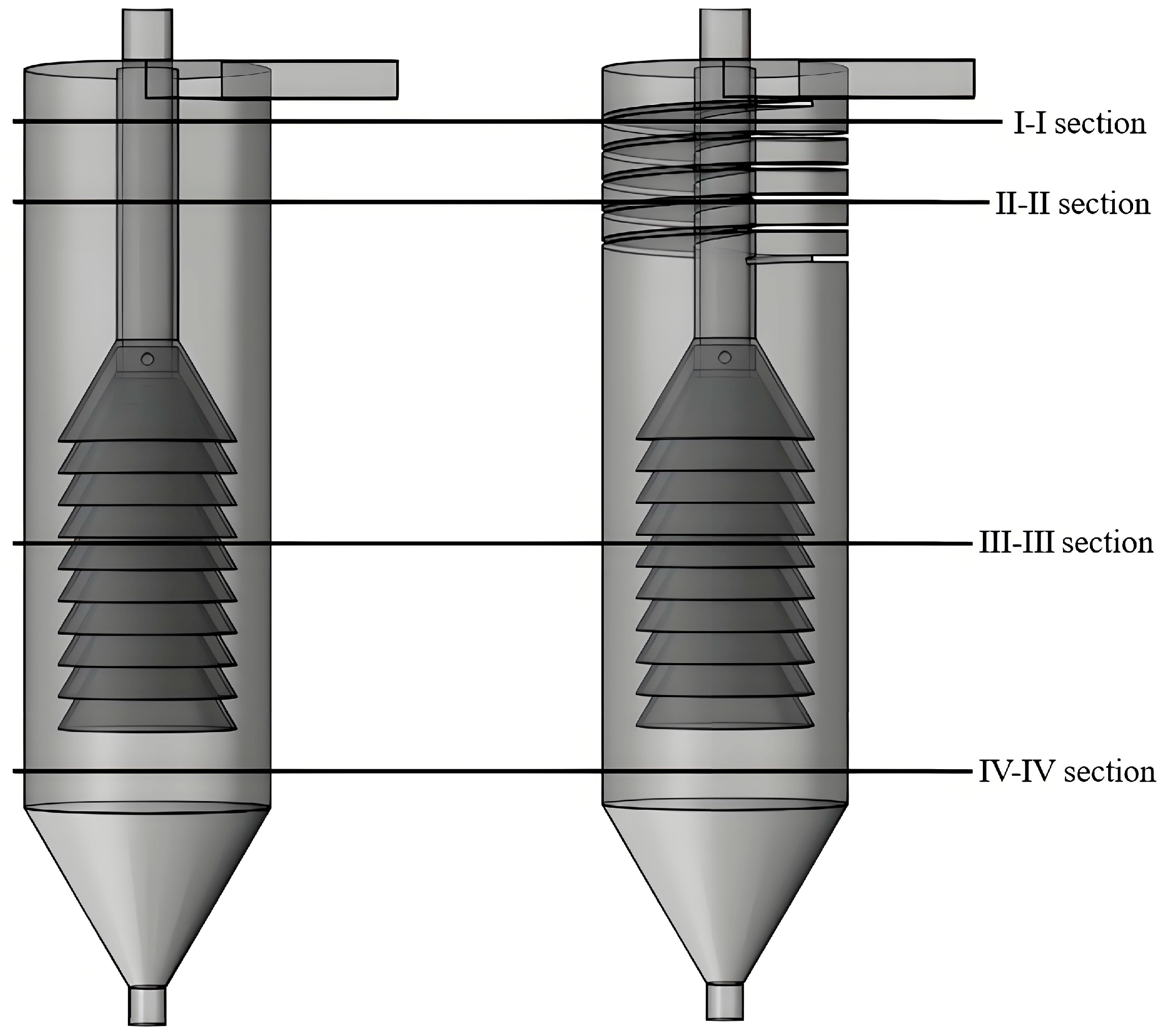

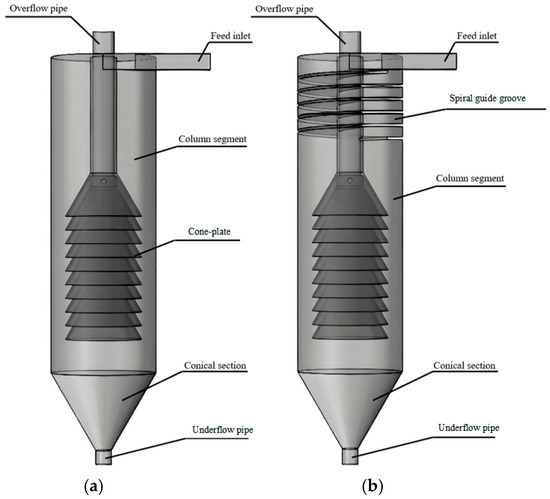

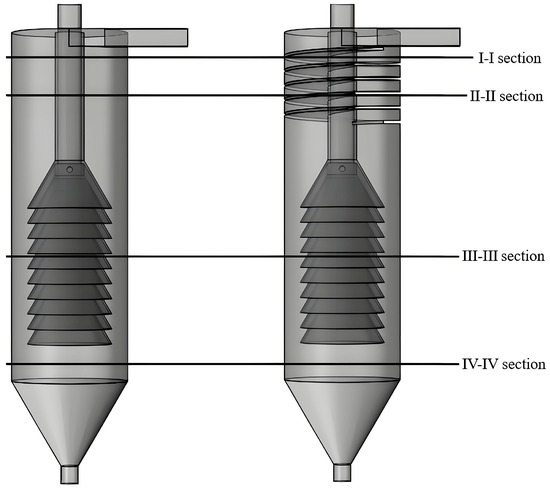

Three-dimensional models of the traditional and spiral guide groove cyclone clarifiers were created using SolidWorks v.2024 modeling software. Figure 1 illustrates the key components of the cyclone clarifiers, including the feed inlet, overflow pipe, underflow pipe, cone-plate, column segment, conical section, and spiral guide groove. Type a is the traditional cyclone clarifier. Type b is the spiral guide groove cyclone clarifier. The center of the clarifier’s underflow outlet is the coordinate origin. The feed inlet direction is the x-axis. The overflow outlet direction is the z-axis.

Figure 1.

3D schematic diagram of two different cyclone clarifiers. (a) Traditional cyclone clarifier; (b) Spiral guide groove cyclone clarifier.

The traditional cyclone clarifier is an improved design based on the hydrocyclone, featuring multiple cone-plates installed inside. These cone-plates are uniformly arranged along the overflow pipe from top to bottom. This configuration effectively increases the available area for particle settling. As the fluid carrying particles flow upward, the cone-plate obstructs their movement path. Fine particles accumulate and settle on the surfaces of the cone-plate. Simultaneously, secondary separation occurs under centrifugal force. This synergistic effect significantly improves particle removal efficiency.

The spiral guide groove cyclone clarifier adds a spiral guide groove structure at the inlet of the traditional cyclone clarifier. Treated mine water enters the spiral guide groove structure tangentially through the feed inlet with a certain initial velocity. It undergoes multiple rotations inside the spiral guide groove before entering the cone-plate region. Larger particles, under centrifugal force and gravity, quickly move downward with the outer vortex through this region to the underflow settling zone. Smaller particles enter the interior of the cone-plates with the flow field for secondary separation and settling. Some particles still pass through the cone-plate structure into the overflow pipe and are discharged from the overflow. Particles reaching the underflow settling zone mostly leave with the outer vortex from the underflow. A small portion of particles enters the overflow pipe with the inner vortex and are discharged from the overflow.

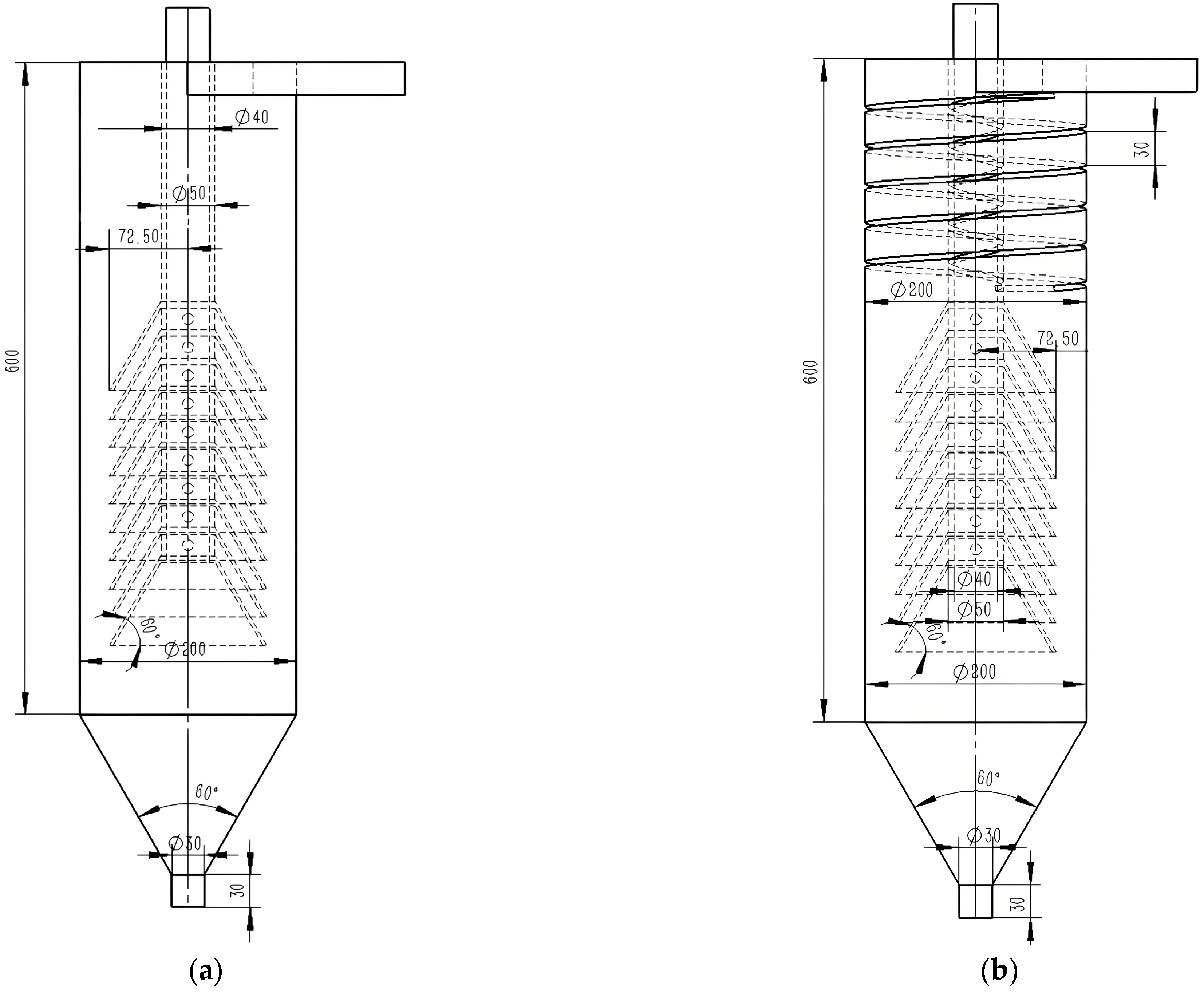

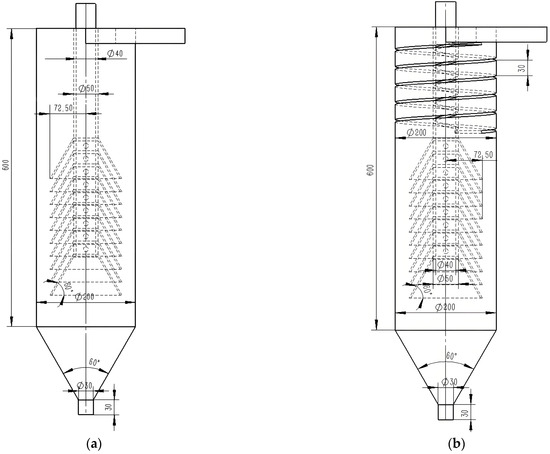

The guide groove mainly guides the flow. Its thickness has little effect on the flow field. The outer diameter of the guide groove is the same as the cylinder’s inner wall diameter. The inner diameter is the same as the overflow pipe’s outer wall diameter. Parameters for each coil are the same as the first coil. Parameters for the two structures are shown in Figure 2. Dimension parameters are shown in Table 1.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of structural parameters of cyclone clarifier. (a) Traditional cyclone clarifier; (b) Spiral guide groove cyclone clarifier.

Table 1.

The structural parameter Table of the spiral guide groove clarifier.

2.2. Boundary Conditions

Numerical simulation can better analyze the internal flow field environment. It helps study fluid motion laws and particle separation and settling processes. The RANS method is a time-averaged statistical method. It describes turbulent flow by solving the averaged flow equations. The k-ε model is a classic two-equation turbulence model. Gronald and Derksen et al. compared multiple turbulence models. Their study confirmed that this model effectively captures key vortex dynamics and particle behavior in cyclones. It is suitable for various flow conditions. It has a relatively low computational cost, a simple structure, and fast convergence. It is a preferred model in practical engineering applications.

In the k-ε model [40,41], the calculation formula of turbulent viscosity (1) is as follows:

where μt denotes the turbulent viscosity, ρ is the fluid density, Cμ is an empirical constant, k is the turbulent kinetic energy and ε is the dissipation rate.

The transport equation of turbulent kinetic energy k (2) is as follows:

where u is the mean velocity vector, μ is the molecular viscosity, σk is the turbulent Prandtl number, and Pk is the production rate of turbulent kinetic energy.

The formula for the generation rate of turbulent kinetic energy (3) is as follows:

where S denotes the magnitude of the mean strain-rate tensor.

The transport equation of the turbulent kinetic energy dissipation rate (4) is as follows:

where σε, Cε1, and Cε2 are empirical constants. These equations form a closed turbulence modeling framework, where the turbulent viscosity is computed from k and ε to relate the mean flow to the turbulent stresses. The k equation governs the transport, production, and dissipation of turbulent kinetic energy, while the ε equation models the evolution of its dissipation rate, thereby predicting the influence of turbulence on the fluid motion.

This study utilizes an Euler–Lagrange particle-tracking approach to simulate the multi-phase flow dynamics in a cyclone clarifier. In this framework, the fluid phase (water) is modeled as a continuous medium, and the solid particles are treated as a discrete phase.

In current hydrocyclone numerical simulation, the Reynolds-Averaged Navier–Stokes equations (RANS) are often chosen for economy and convenience. The governing equations for the fluid flow are the incompressible Navier–Stokes equations [42,43,44]:

where u represents the velocity vector, p denotes pressure, ρ and μ are the fluid density and dynamic viscosity, respectively, and F accounts for body forces.

The motion of individual particles is described by Newton’s second law [25,45,46]:

Here, vp is the particle velocity, Fc denotes the centrifugal force, Fg represents the gravitational force, and Fd is the drag force exerted by the fluid. The drag force exerted by the fluid on the particles is expressed as follows:

where CD is the drag coefficient, Rer denotes the particle Reynolds number, ρp is the particle density, and dp represents the particle diameter.

The fluid flow was governed by the k-ε turbulence model based on the finite element method. The built-in fully coupled algorithm was used for pressure–velocity coupling. A second-order element order was applied for the discretization of convection terms. This balanced accuracy and computational cost. The convergence criterion required relative tolerances below 1 × 10−4 for all physical quantities. The computational domain was discretized using a free tetrahedral mesh. Near-wall regions were handled with the standard wall function. Mesh refinement was applied near the walls. This ensured the first grid node was within the logarithmic layer. The dimensionless wall distance y+ was maintained between 30 and 200. This approach ensured accuracy while avoiding the high cost of resolving the viscous sublayer. It is a widely adopted practice in cyclone simulations.

The physical properties of the fluid and particle phases are summarized in Table 2. The fluid was water. The particle type was solid. The particle density was 1500 kg/m3. Particles were released at time zero. The time step was 0.01 s. The inlet velocity at the feed was 2 m/s with normal inflow. The Reynolds number is 47,770. This value clearly indicates that the flow is in a fully developed turbulent state. For the studied particles (diameter range: 10–30 μm), the Stokes number ranges from 8.31 × 10−5 to 7.47 × 10−4. All Stokes number values are significantly less than 1, indicating weak particle inertia effects, and that the separation primarily relies on centrifugal forces within the swirling flow rather than inertial impaction.

Table 2.

Physical properties of the fluid and particle phases.

The inlet boundary was configured as a velocity inlet, with the flow direction normal to the inlet surface. The turbulence parameters were specified based on the k–ε model, with the turbulent kinetic energy k = 0.015 m2/s2 and the turbulent dissipation rate ε = 0.179 m2/s3. The outlet was set as a pressure outlet with gauge pressure equal to 0 Pa. All fluid walls were treated as no-slip boundaries, and the standard wall function was applied to resolve near-wall flow, assuming a wall roughness of zero (i.e., hydraulically smooth walls). The interaction between particles and walls was defined as a rebound condition. In addition, a one-way coupling approach was adopted, meaning that only the effect of the fluid phase on the particles was considered, while the feedback from particles to the flow field was neglected.

To resolve the fluid phase, a steady-state Reynolds-Averaged Navier–Stokes (RANS) approach was employed. Once the flow field had achieved convergence, particle motion was modeled via a transient Lagrangian tracking technique. A sequential one-way coupling strategy was utilized here: the converged steady flow field acted as a static background domain, within which particles were injected and their paths tracked with no reciprocal effects on the pre-calculated fluid solution. Notably, the 0.01 s time step was only applied during the particle-tracking stage of the simulation. This decoupled computational framework offers favorable efficiency in terms of computing resources; moreover, it remains theoretically and practically valid for the low-inertia, low-particle-concentration conditions of this study, which is consistent with justifications presented in prior work.

In this study, the one-way coupling approach was employed, whereby the fluid phase drives particle motion while any feedback from the particles to the continuous flow field is disregarded. This simplification is well-founded under the present research conditions. First, the investigated particle size range (10–30 μm) yields Stokes numbers between 8.31 × 10−5 and 7.47 × 10−4, all markedly below unity. Such low values confirm that particle motion is tightly coupled to the carrier fluid, with negligible inertial feedback on the flow field. Second, the core aim of this work is to assess how the spiral guide groove alters the macroscopic flow pattern and separation behavior. For this purpose, the combination of the RANS-based k-ε turbulence model with one-way coupling has been shown in prior cyclone studies to deliver dependable predictions of mean flow and separation efficiency, striking a practical compromise between accuracy and computational effort [31,32,33]. Third, the simulated system features a low particle concentration, and particles are treated as discrete, non-interacting rigid spheres. Although phenomena such as particle–particle collisions, breakage, and agglomeration can play decisive roles in dense or complex multi-phase flows [34,35], their influence is anticipated to be minor here, given the focus on elucidating the primary mechanism through which the spiral guide groove enhances performance. The present modeling strategy successfully captures the dominant flow features and separation trends while retaining computational efficiency, thereby laying a sound foundation for subsequent work that might implement more advanced two-way coupling or discrete element methods (DEM) for higher-fidelity simulations.

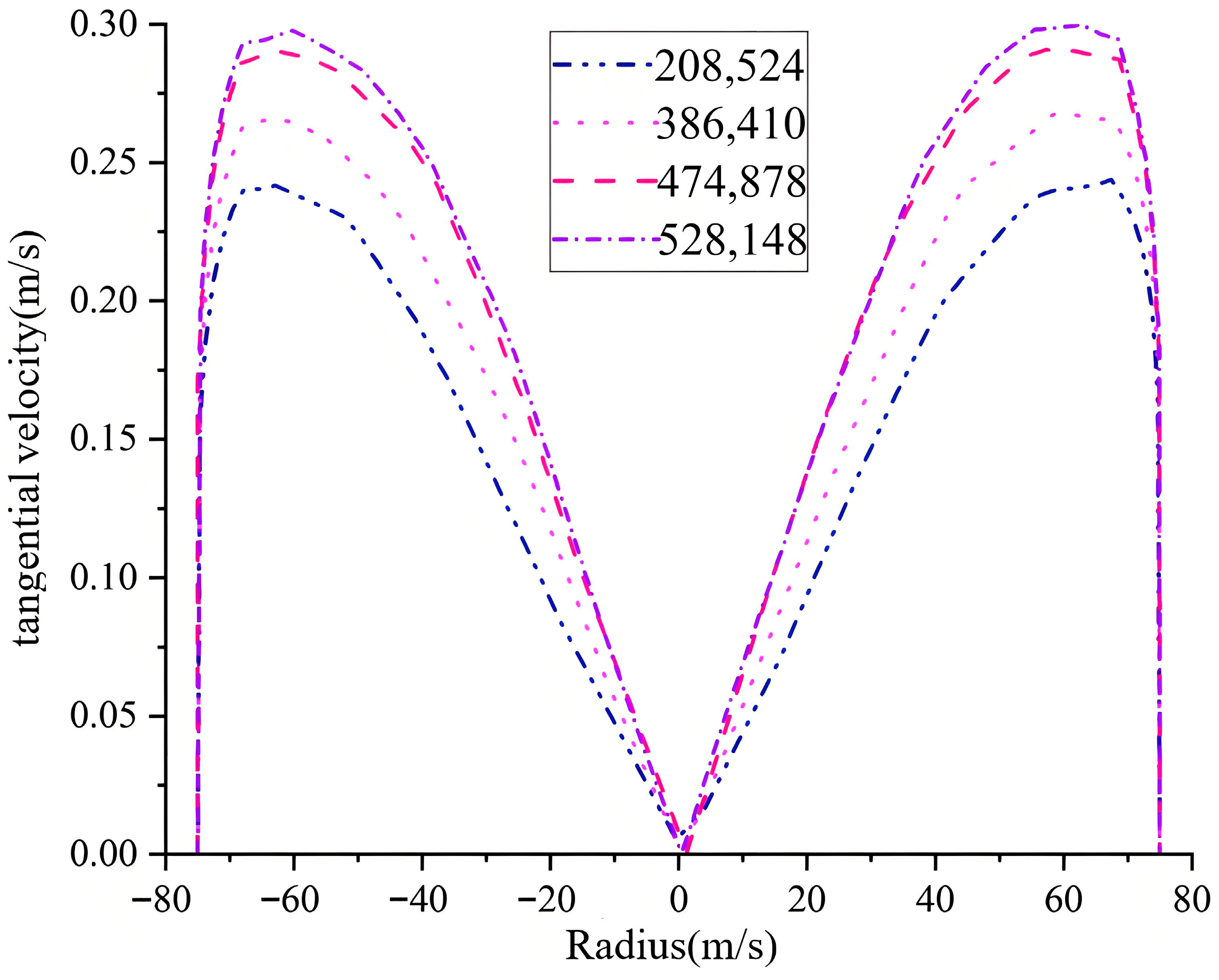

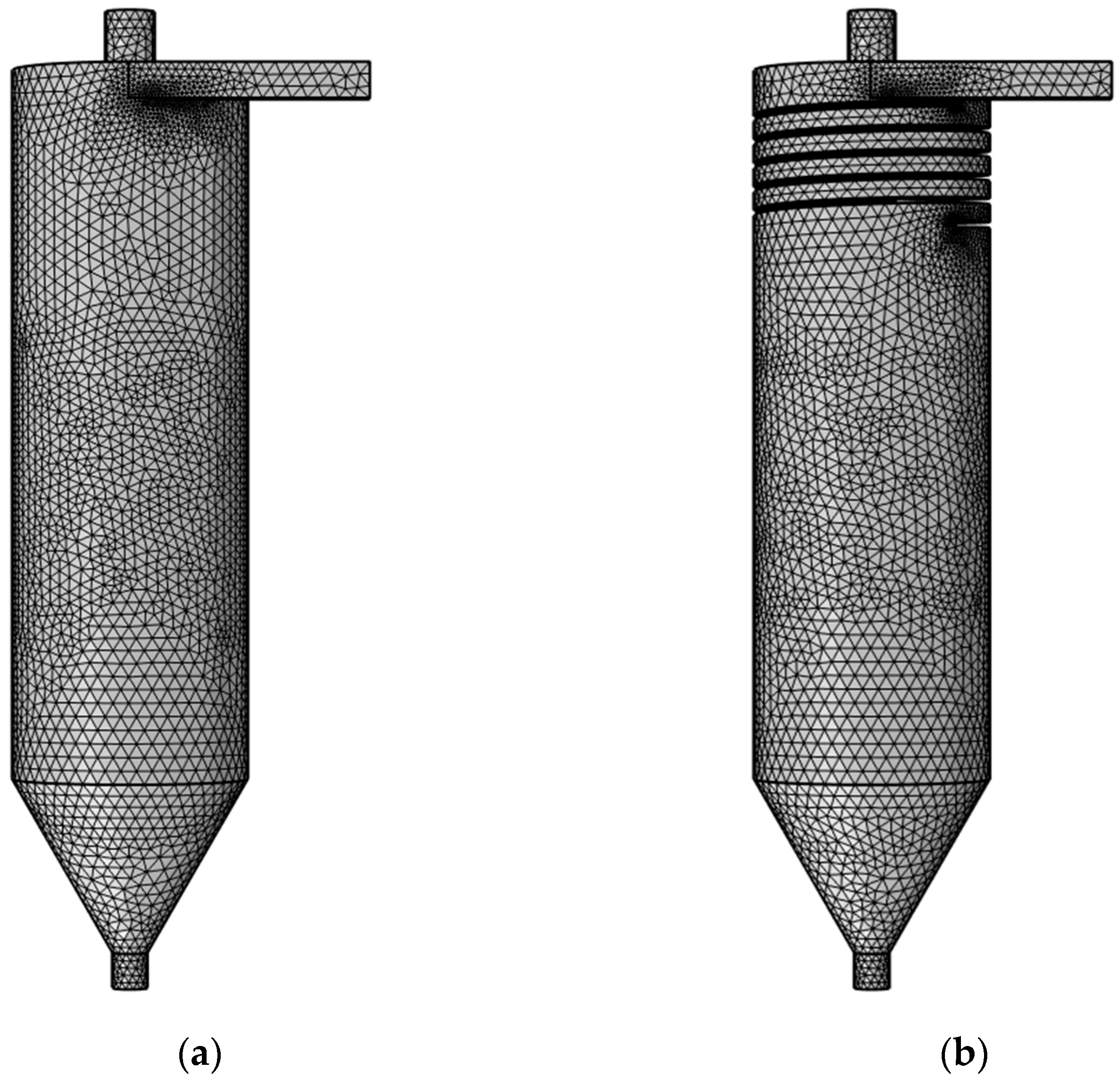

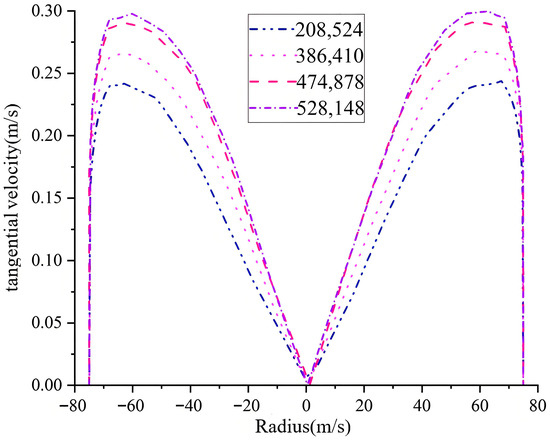

2.3. Grid Independence Analysis

Grid division is also called discretization. It is a basic step in numerical analysis. It discretizes a continuous domain into finite elements. It transforms complex physical problems into mathematical models for solutions. Improving element quality can increase accuracy to some extent. But it significantly reduces solving efficiency. It increases computation time and resource consumption. Therefore, numerical simulation needs to balance accuracy and efficiency. It ensures accuracy while avoiding an unnecessary waste of computing resources.

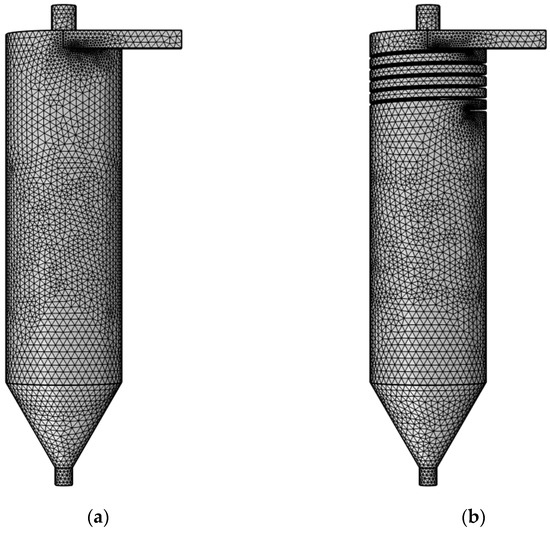

A quantitative analysis based on the Grid Convergence Index (GCI) was conducted to evaluate the influence of mesh density on numerical results. Four systematic meshes were generated. The mesh with 208,524 elements was excluded from the quantitative analysis due to its low cell count, potentially failing to meet asymptotic convergence requirements. Subsequently, the meshes with 386,410, 474,878, and 528,148 elements were used as the coarse, medium, and fine sets for GCI calculation. The Grid Convergence Index analysis demonstrated that the GCI value from the medium to the fine mesh was 2.08%, which met the convergence criteria, while the GCI from the coarse to the medium mesh was 6.46%, indicating insufficient accuracy. Based on these findings, the medium mesh configuration was selected for all subsequent simulations, achieving an optimal balance between computational accuracy and efficiency. The mesh quality was assessed using tangential velocity. The relationship between tangential velocity and mesh density is shown in Figure 3. Fluid tangential velocity relates to the elements’ number within a certain range. Tangential velocity increases with the elements’ number. When the elements’ number reaches 474,878, tangential velocity shows no obvious fluctuation with further increase. This indicates that more elements have no significant impact on numerical simulation but increase computation time. Therefore, this numerical analysis uses 474,878 elements. The elements’ division results are shown in Figure 4.

Figure 3.

Elements’ independence verification diagram.

Figure 4.

Elements’ division diagram of the cyclone clarifier. (a) Traditional cyclone clarifier; (b) spiral guide groove cyclone clarifier.

2.4. Numerical Simulation Feasibility Verification

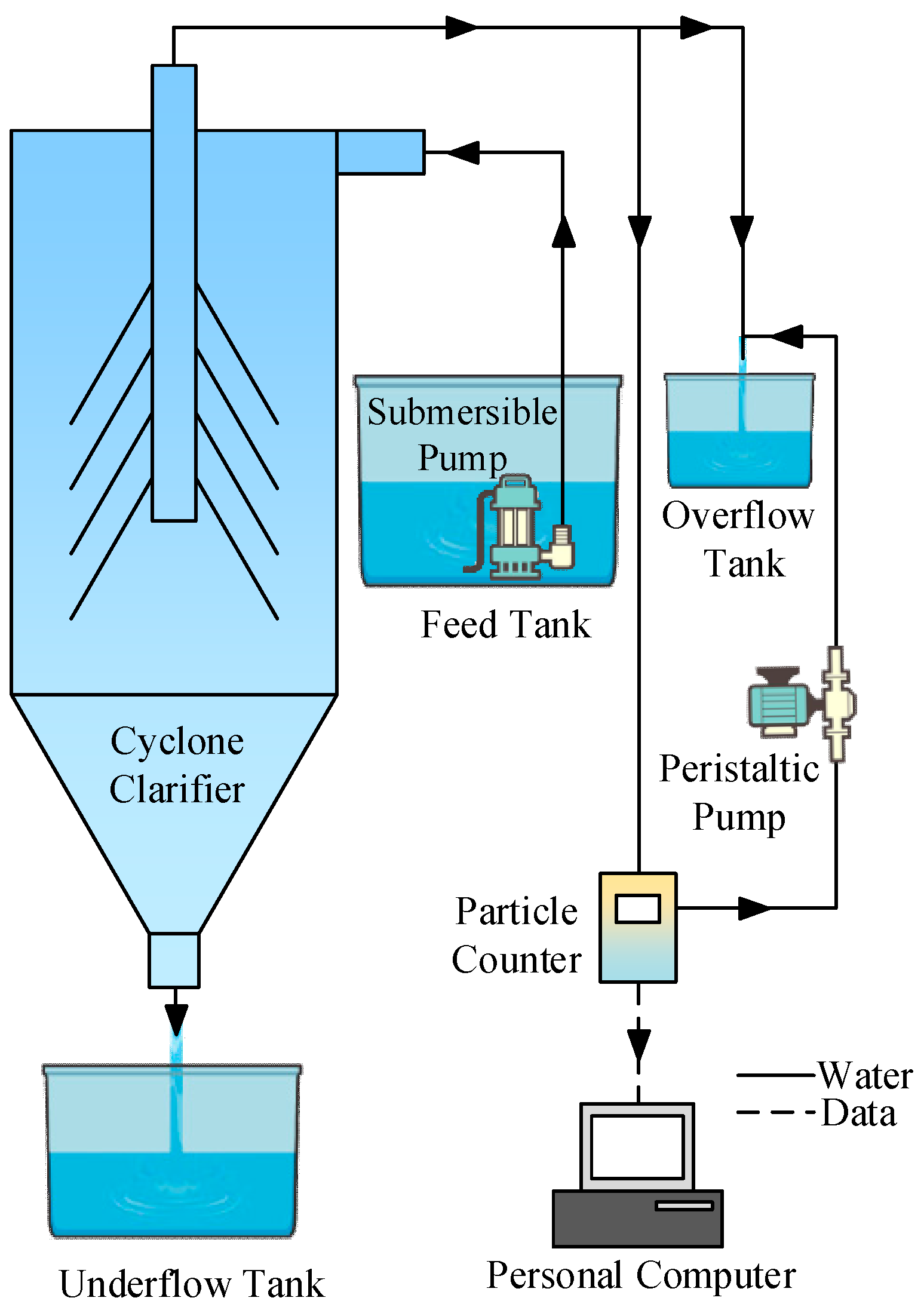

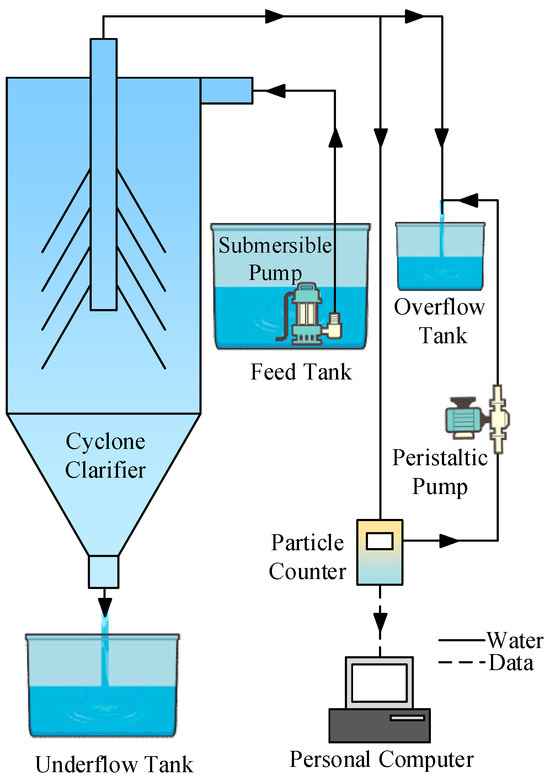

An experimental test rig was constructed to investigate the sedimentation performance of a traditional cyclone clarifier. The schematic diagram of the cyclone clarifier experimental system is outlined in Figure 5. Mine water was fed into the cyclone clarifier by a submersible pump. Efficient particle separation was achieved through a combination of centrifugal sedimentation and cone-plate settling. Following separation, the concentrated particles were discharged from the underflow outlet of the clarifier into an underflow tank. The clarified water exited through the overflow outlet and was directed to an overflow tank. To evaluate separation efficiency, a peristaltic pump was used to draw a continuous sample stream from the overflow. An online particle counter monitored the particle concentration in the overflow in real-time, with the data being logged and analyzed by a computer.

Figure 5.

Schematic diagram of the cyclone clarifier experimental system.

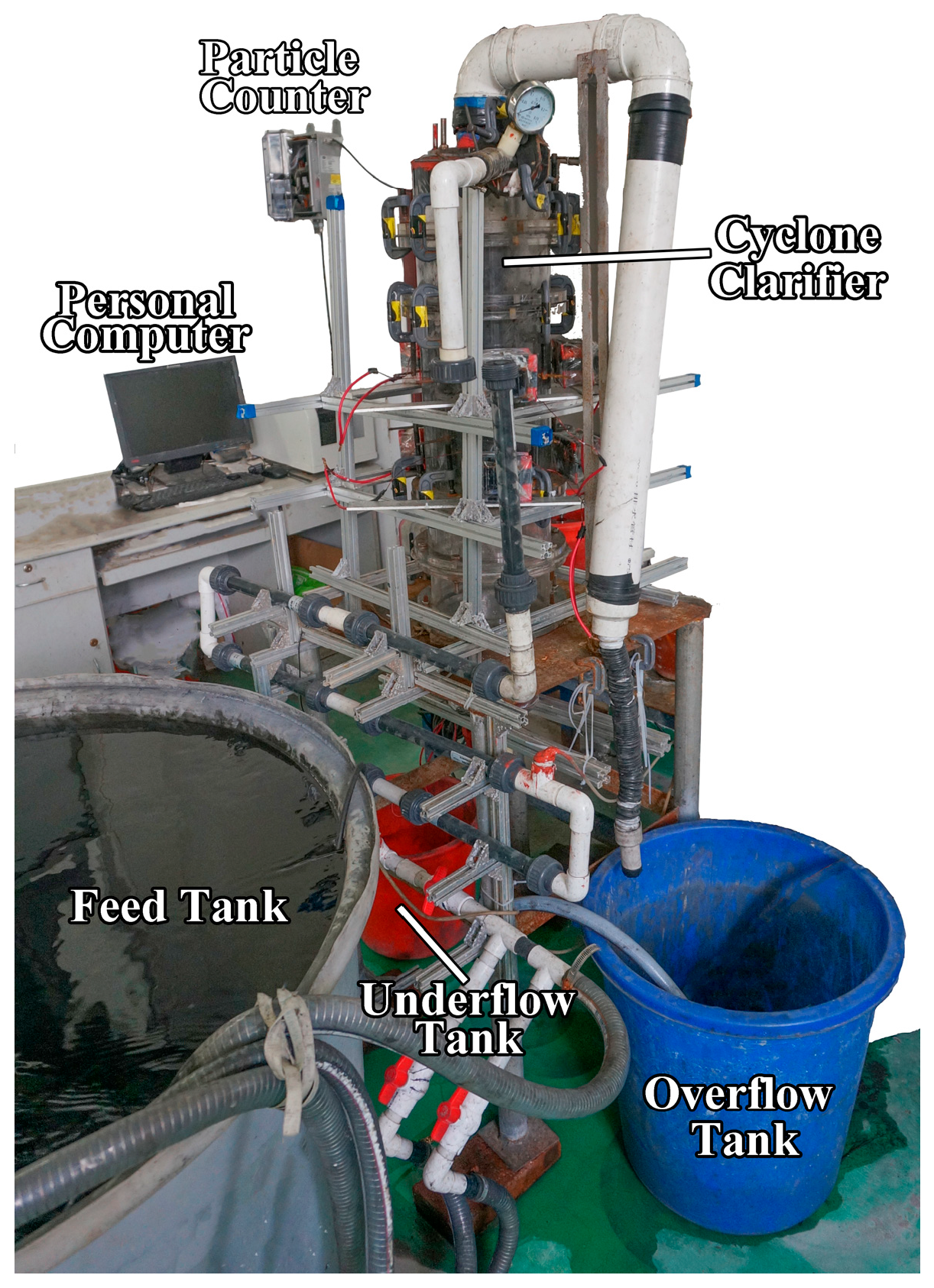

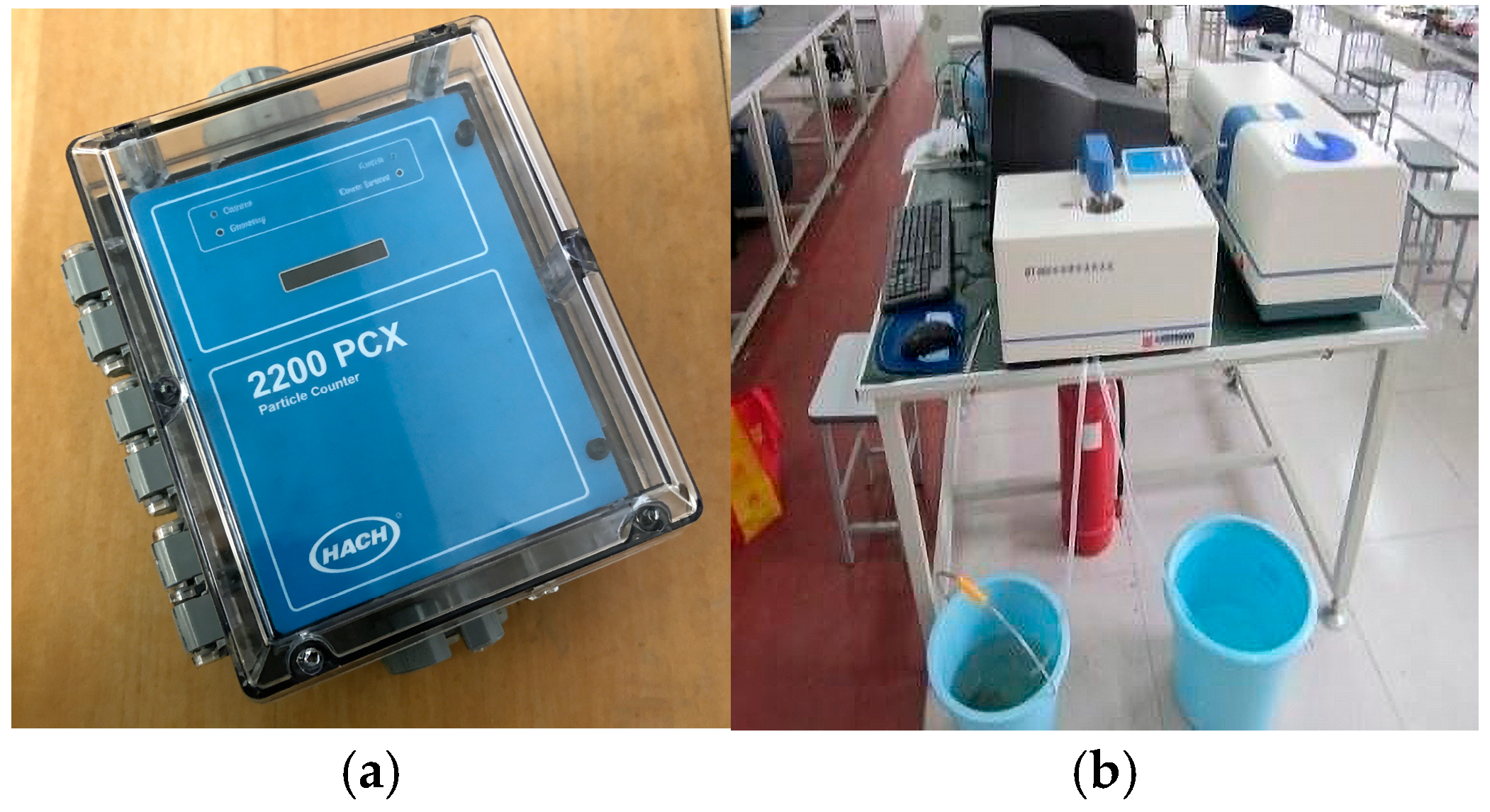

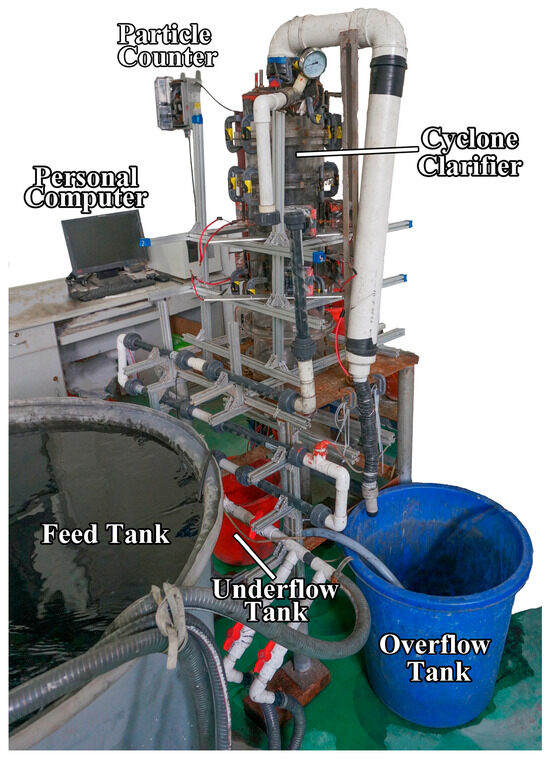

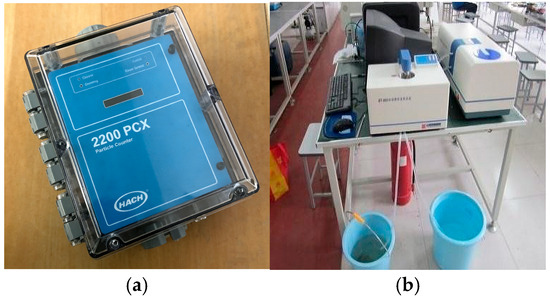

A physical diagram is shown in Figure 6. The test setup is shown in Figure 7. The particle size distribution in the mine water was determined by laser particle size analysis. The measured volume fractions for particles with diameters of 10 μm, 15 μm, 20 μm, 25 μm, and 30 μm were 33.33%, 26.66%, 20%, 12.33%, and 6.66%, respectively. The particle density was 1500 kg/m3. The system operated at a flow rate of 1 m3/h. This flow rate was measured using a flow meter. The meter was calibrated by collecting the total fluid volume over a predetermined time interval. The effluent particle concentration and size distribution were monitored in real-time using an online particle counter (Hach, Model 2200 PCX, Loveland, CO, USA). This instrument can detect and size particles in multiple channels within the range of 2 to 750 μm, providing the data necessary for calculating removal efficiency. The main sources of measurement uncertainty included instrument precision, human reading error, and water temperature fluctuations.

Figure 6.

Physical diagram of experimental system.

Figure 7.

Physical photo of the test equipment. (a) Online particle counter; (b) Laser particle size analyzer.

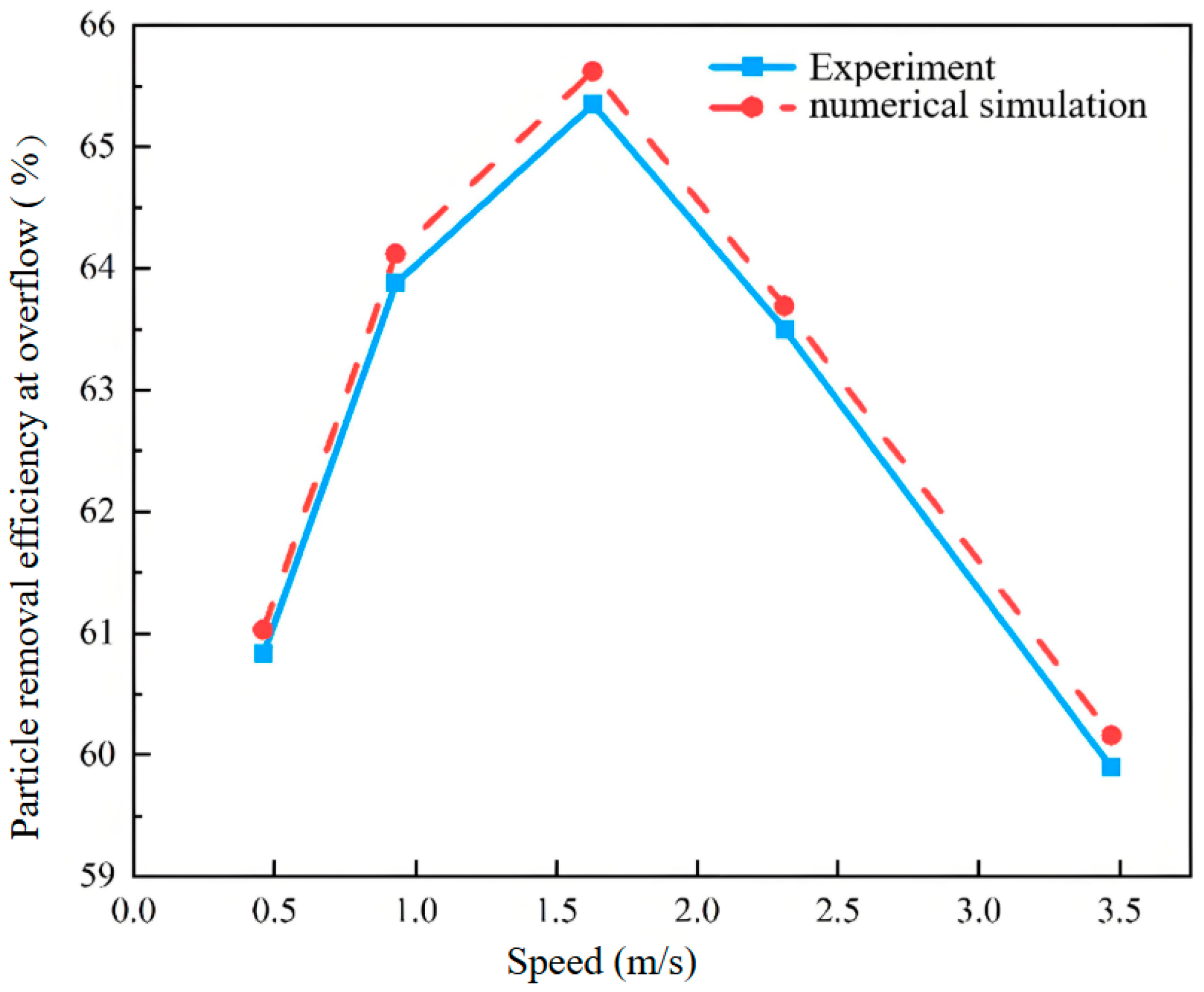

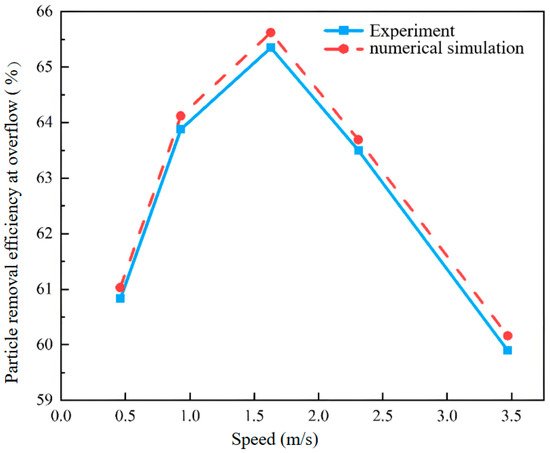

Figure 8 compares the simulated and experimental particle removal efficiencies at the overflow under different inlet velocities (0.46, 0.93, 1.63, 2.31, and 3.47 m/s). The results demonstrate excellent agreement between the two, with marginal deviations of only 0.20, 0.24, 0.27, 0.14, and 0.26 percentage points, respectively. This close alignment confirms that the numerical simulation accurately captures the real physical process, thereby validating its feasibility for this study.

Figure 8.

Comparison of particle removal efficiency at overflow.

3. Results and Discussion

The 3D model in this paper adds a spiral guide groove to the traditional cyclone clarifier. This change inevitably alters flow field behavior. It affects particle cyclone separation. A comparative analysis was conducted via numerical simulation. The numerical simulation spanned a physical time of 30 s to ensure that the flow field was fully developed and that the particle separation process had reached a steady state. All simulations were conducted on a workstation featuring an Intel Xeon Gold 6248R processor (Intel Corporation, Santa Clara, CA, USA) and 128 GB of RAM. The total computational time required for each complete simulation case—encompassing both the steady-state fluid flow solution and the subsequent transient particle tracking—ranged from approximately 12 to 14 h.

To analyze the impact of the internal structure on the flow field, different 2D cross-sections were selected. This facilitates analyzing local distributions of physical quantities like velocity. Section locations are shown in Figure 9. Section I-I is in the upper spiral guide groove region, where height Z = 750 mm. It shows the flow state before fluid enters the guide structure. Section II-II is in the lower guide groove region, where height Z = 680 mm. It is the region where fluid is continuously constrained by the guide structure. Sections I-I and II-II reflect the influence of the groove on fluid motion near the inlet. Section III-III is in the middle cone-plate region, where height Z = 400 mm. Section IV-IV is between the lower cone-plate and the cone section, where height Z = 220 mm. Selecting III-III and IV-IV can effectively reveal the actual control effect of the groove on the internal flow field distribution. This is necessary for structural optimization and performance evaluation.

Figure 9.

Sectional location diagram.

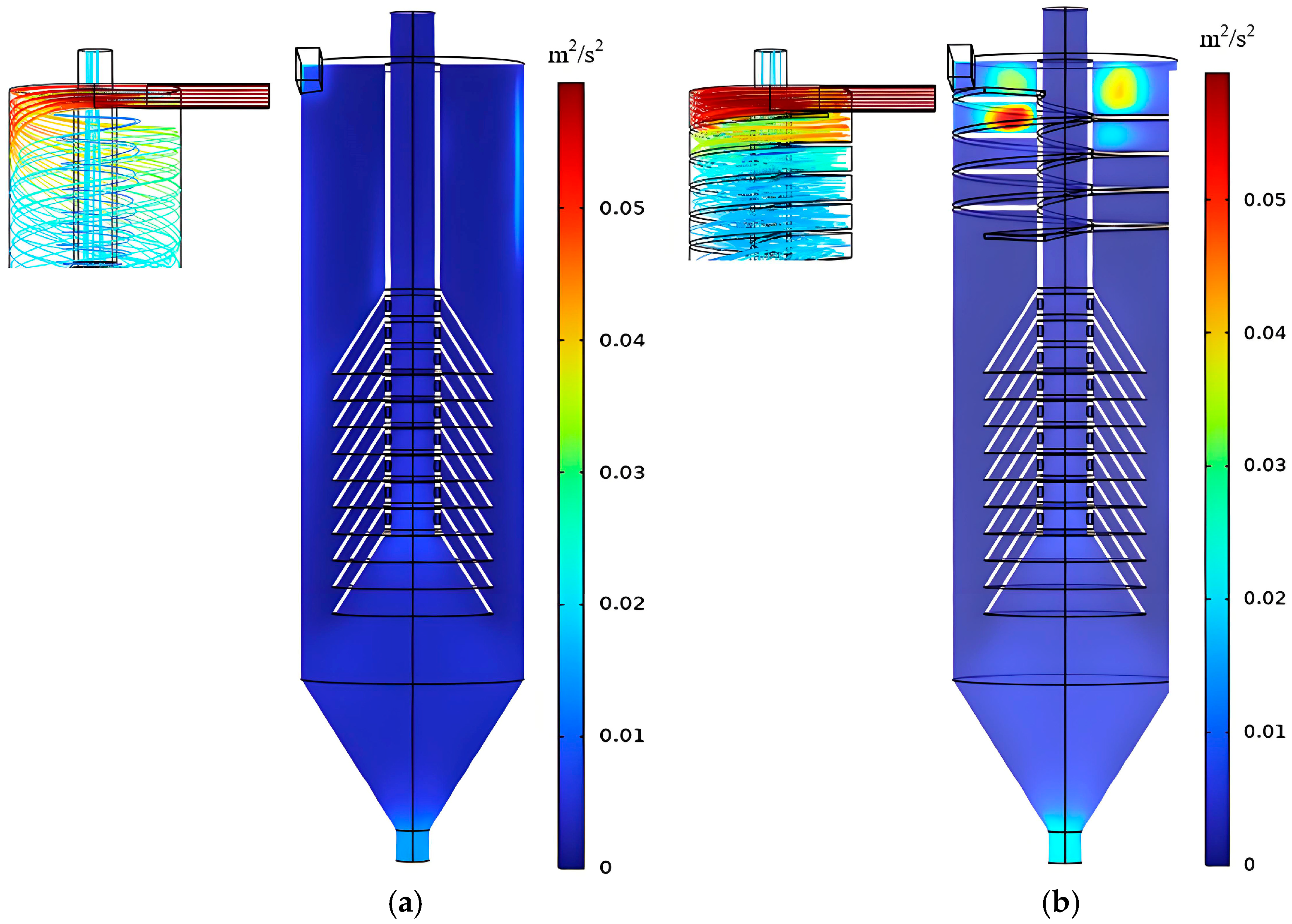

3.1. Streamline Analysis

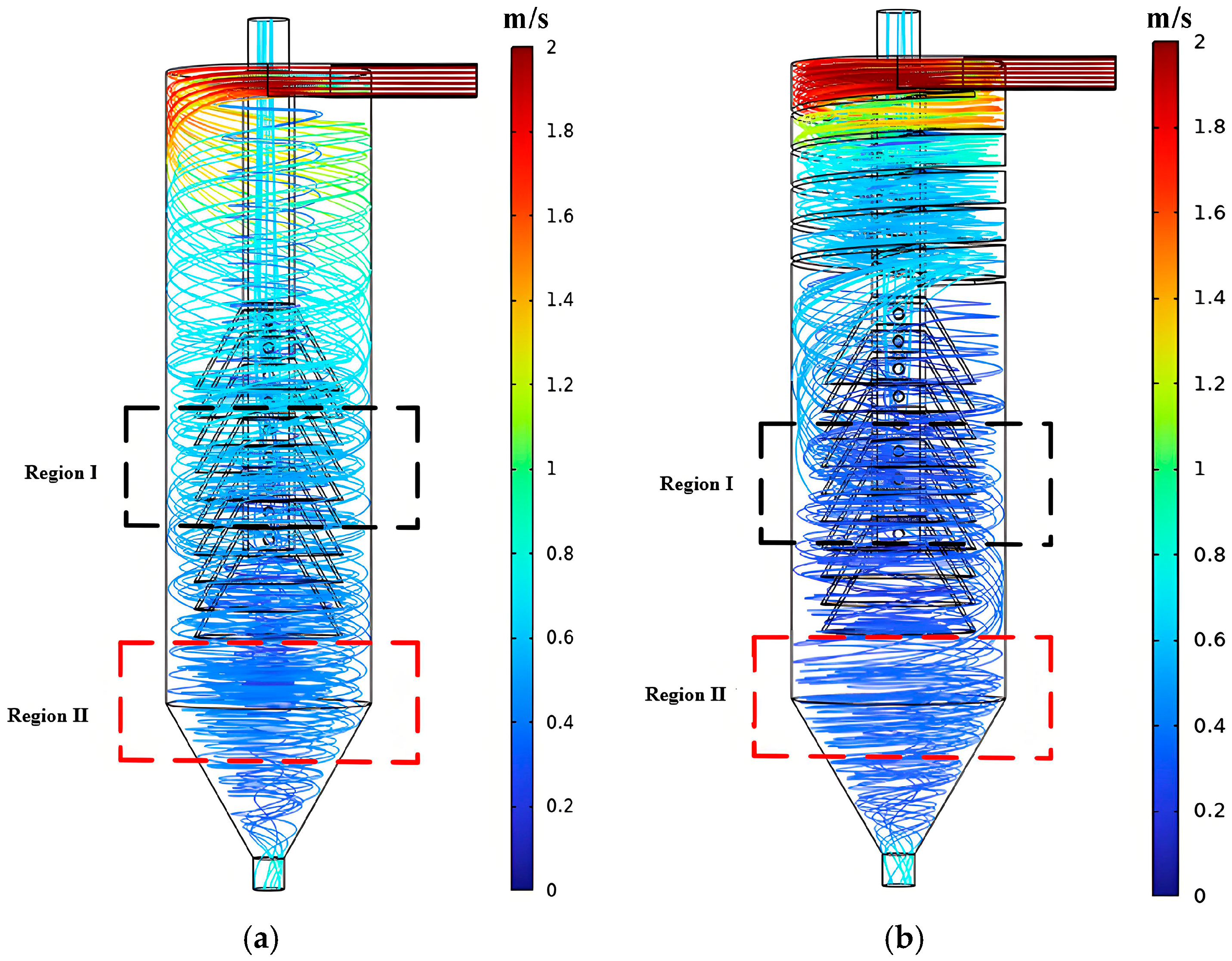

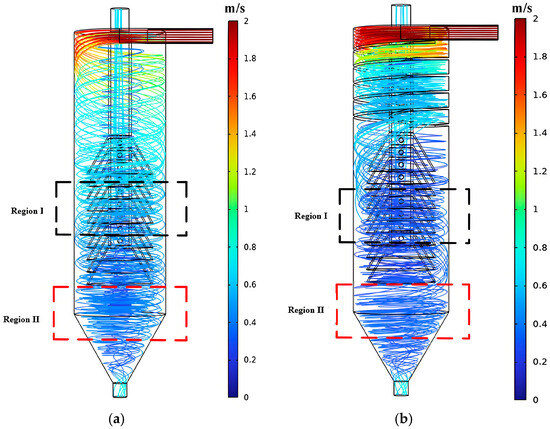

Streamlines are a visualization tool for fluid motion. They are generated by calculating the direction and distribution of the velocity vector field. The tangent direction at any point on a streamline is consistent with the flow velocity direction at that point. Streamlines visually show the instantaneous velocity direction and trajectory of fluid particles inside the clarifier. Streamline diagrams for both clarifiers are shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Streamline diagram of the fluid. (a) Traditional cyclone clarifier; (b) Spiral guide groove cyclone clarifier.

Mine water enters tangentially and begins rotating downward. The outer vortex moves down along the wall of the cylindrical section. In the conical underflow settling zone, the cross-section gradually narrows. Part of the outer vortex fluid is forced to change direction inward due to greater centrifugal force and flow resistance. This forms the upward-moving inner vortex. Region I is the cone-plate area. Particles in the fluid passing the cone-plates can settle on them. This improves the particle-settling effect. Region II is the inner vortex generation area. Excessive inner vortex carries some coarse particles to the overflow. This reduces overflow water quality.

As shown in Figure 10a, in the traditional cyclone clarifier, fluid enters with high initial kinetic energy. High-speed flow directly impacts the cylindrical wall. Streamlines descend rapidly vertically. Particles quickly enter and pass down through the cone-plate area without sufficient separation. This makes streamlines sparse in Region I. The cyclone separation at the inlet and cone-plate settling are not fully utilized. Streamlines are dense in Region II. This is mainly because less fluid enters the overflow pipe through the cone-plates. The downward outer vortex increases, leading to an increased inner vortex. More particles enter the overflow pipe from the underflow.

As shown in Figure 10b, after adding the spiral guide groove, streamlines are dense at the inlet. The number of rotations increases. Separation time lengthens. Particles of different sizes can fully separate here. Streamlines in Region I are denser. This indicates that more particles enter the cone-plates for settling. Streamlines below the cone-plates in Region II are sparse. This indicates fewer outer and inner vortices in the cone section. Less flow enters the overflow pipe from the underflow. This is more favorable for particle settling and separation.

Comparing the streamline diagrams shows that the spiral guide groove facilitates full particle separation. It improves cone-plate utilization. It reduces the probability of the inner vortex directly carrying particles to the overflow. It helps improve overflow water quality.

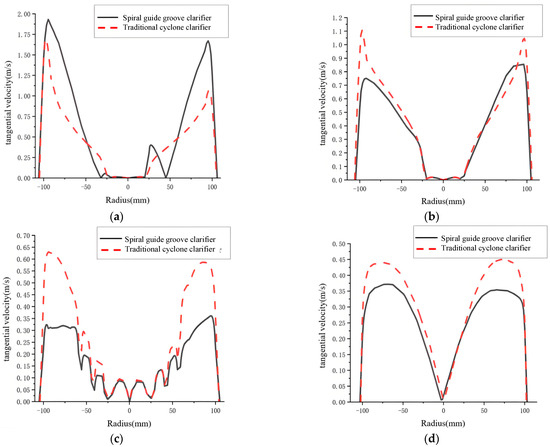

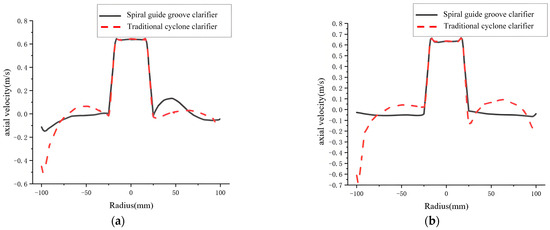

3.2. Tangential Velocity Analysis

Mine water enters the clarifier tangentially. It rotates along the spiral guide groove structure. In the 3D flow, tangential velocity is the largest velocity component. Larger tangential velocity enhances centrifugal action. Denser particles migrate more easily to the outer wall. The separation effect improves. Centrifugal force on particles is the main driver for radial migration. Centrifugal force (5) can be expressed as follows:

In the formula, is the centrifugal force on the particles; is the tangential velocity of the particles; is any position in the clarifier flow field; is the particle size; and is the particle density. The centrifugal force is proportional to the square of the tangential velocity. Larger particle size and tangential velocity make particles migrate more easily to the outer wall.

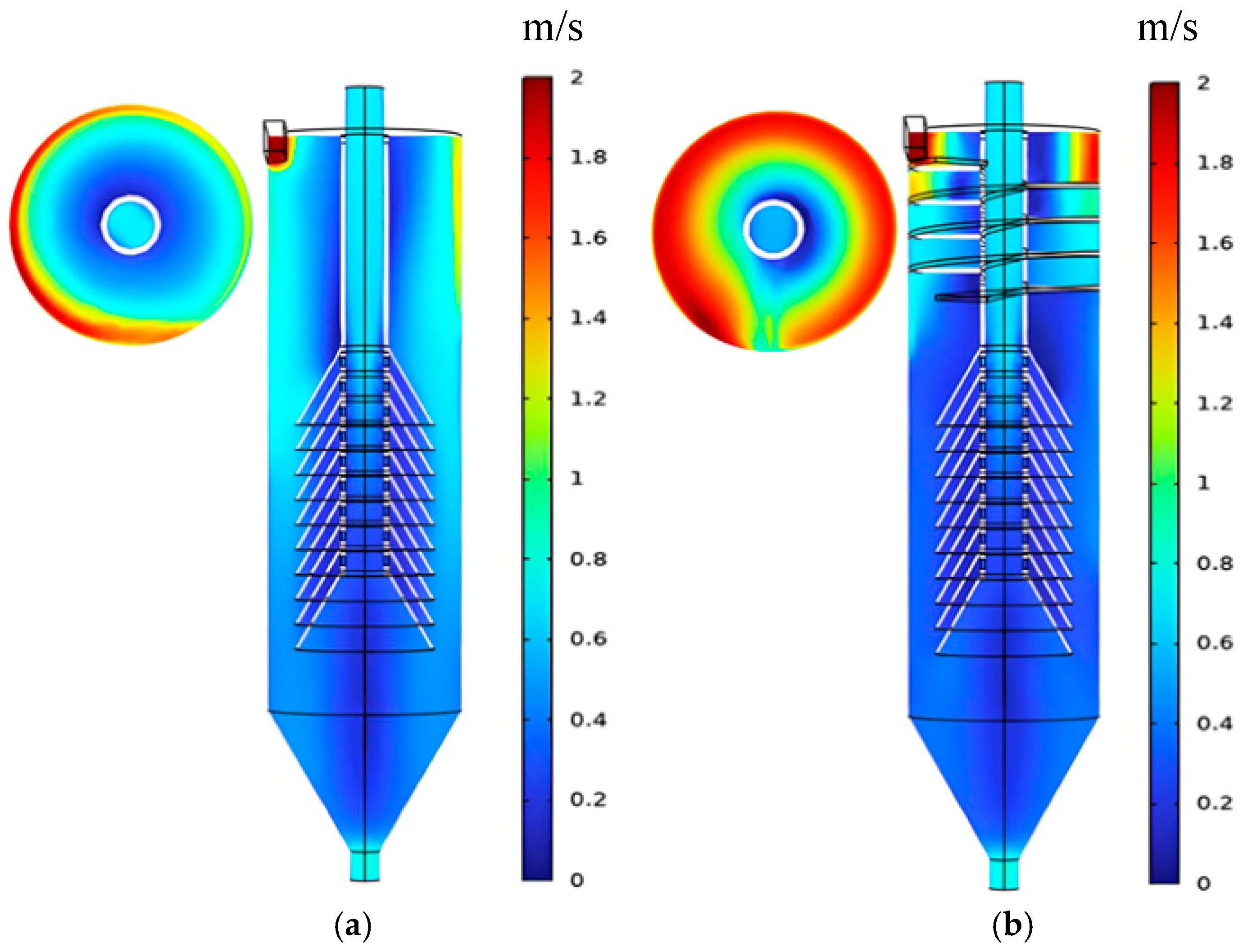

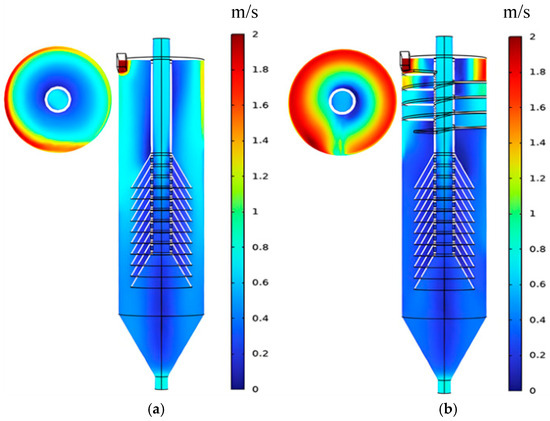

Contours of tangential velocity distribution are shown in Figure 11. The velocity contours for both clarifiers are basically symmetrical about the central axis. In Figure 11a, the traditional cyclone clarifier’s tangential velocity peaks near the feed inlet. It then decreases rapidly during rotation. Afterwards, it enters a relatively uniform deceleration stage. Figure 11b shows that the spiral guide groove cyclone clarifier also has high tangential velocity at the inlet. But due to the groove, the fluid rotation state is guided. The velocity decay trend is gentler. Its overall tangential velocity is higher than the traditional cyclone clarifier. In the guide groove, streamlines have more rotations and higher tangential velocity. This allows full separation under centrifugal force. At the groove end, tangential velocity drops rapidly. Then, it enters a uniform deceleration stage.

Figure 11.

Tangential velocity distribution contour diagram. (a) Traditional cyclone clarifier; (b) Spiral guide groove cyclone clarifier.

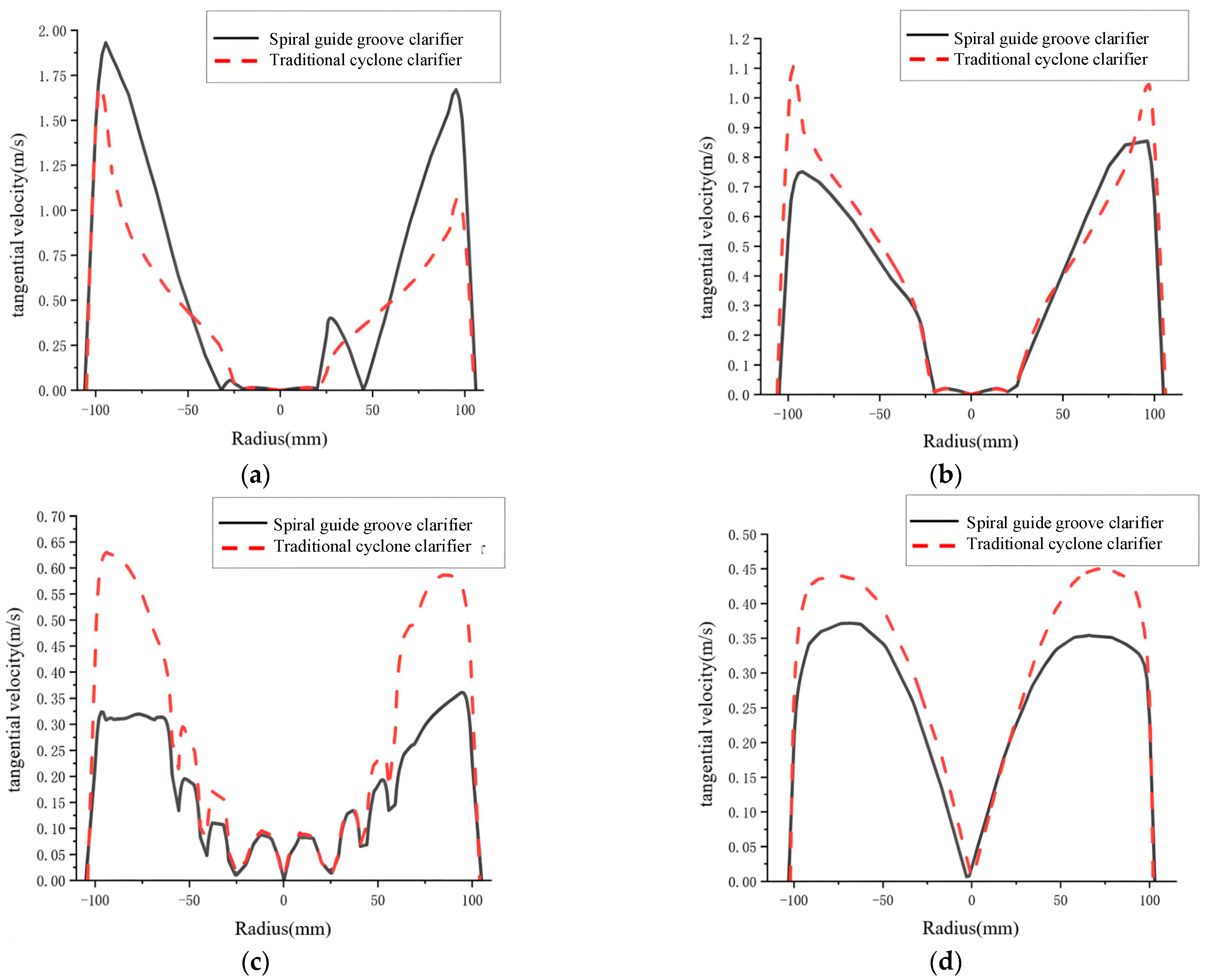

Figure 12 shows tangential velocity comparisons in different sections. At all four sections, tangential velocity increases from the outer wall and then decreases to 0 m/s as the radius decreases. The traditional cyclone clarifier has no guide groove constraint. The cylinder diameter is large compared to the inlet. So, velocity decreases significantly when fluid enters the cylinder. The spiral guide groove cyclone clarifier has a small descent height per rotation. The cross-sectional area between grooves is small. So, the velocity decrease is smaller when fluid enters the cylinder. Combined with streamlined analysis, Section I-I has a higher tangential velocity in the spiral guide groove cyclone clarifier. Centrifugal force is larger. This favors particle separation.

Figure 12.

Tangential velocity comparison diagram. (a) I-I section; (b) II-II section; (c) III-III section; (d) IV-IV section.

The spiral guide groove cyclone clarifier has dense streamlines in the groove. It has many rotations at the inlet and a high tangential velocity. So, fluid experiences greater friction and resistance along the groove. Tangential velocity decreases at Sections II-II, III-III, and IV-IV. Lower tangential velocity in the cone-plate and underflow regions favors reduced disturbance and particle settling.

3.3. Axial Velocity Analysis

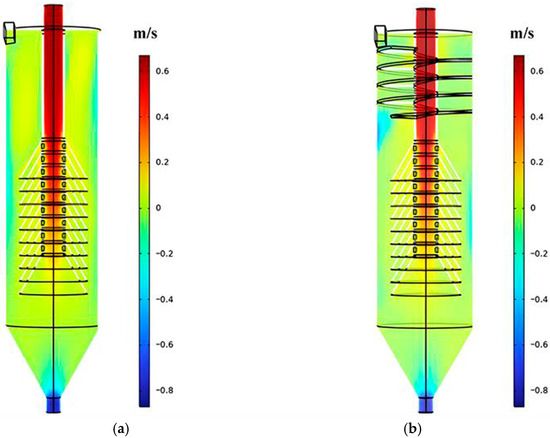

Axial velocity is the velocity component along the axis direction. It is also called vertical velocity. It affects the residence time of fluid and particles in the clarifier. Longer separation time leads to more sufficient separation. Axial velocity greatly influences particle settling and separation.

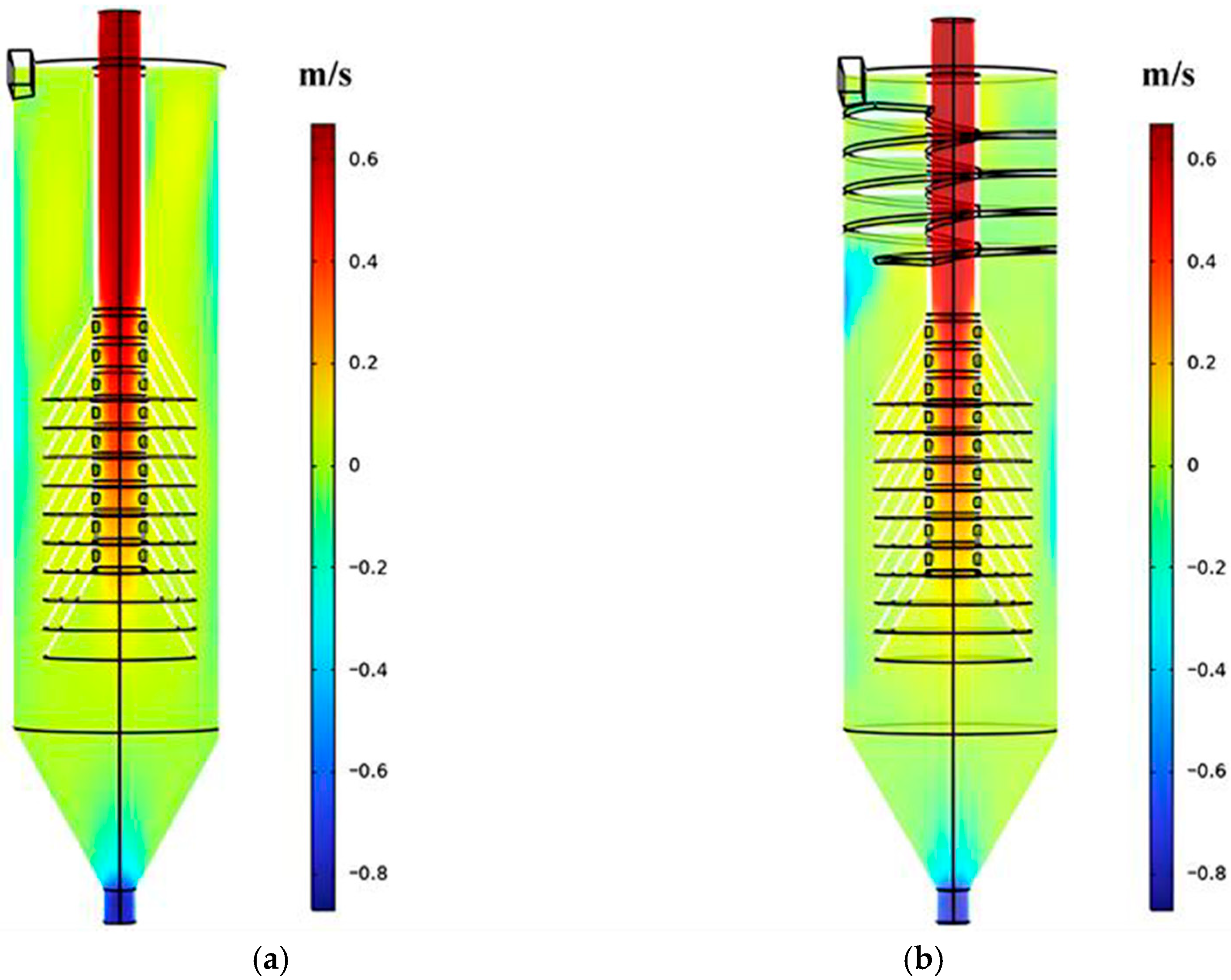

Axial velocity distribution contours for both clarifiers are shown in Figure 13. The overall distributions are similar. Axial velocity is highest at the overflow and underflow outlets. The spiral guide groove restricts axial motion. So, axial velocity is small here. The separation time is long. Combined with previous analysis, the tangential velocity is high here. Centrifugal force is large. This favors full particle separation. Losing the guide effect at the groove end causes a local increase in axial velocity. Except for near the groove end, as axial velocity near the outer wall is higher in the traditional cyclone clarifier. The separation time is short.

Figure 13.

Axial velocity distribution contour plot of fluid. (a) Traditional cyclone clarifier; (b) Spiral guide groove cyclone clarifier.

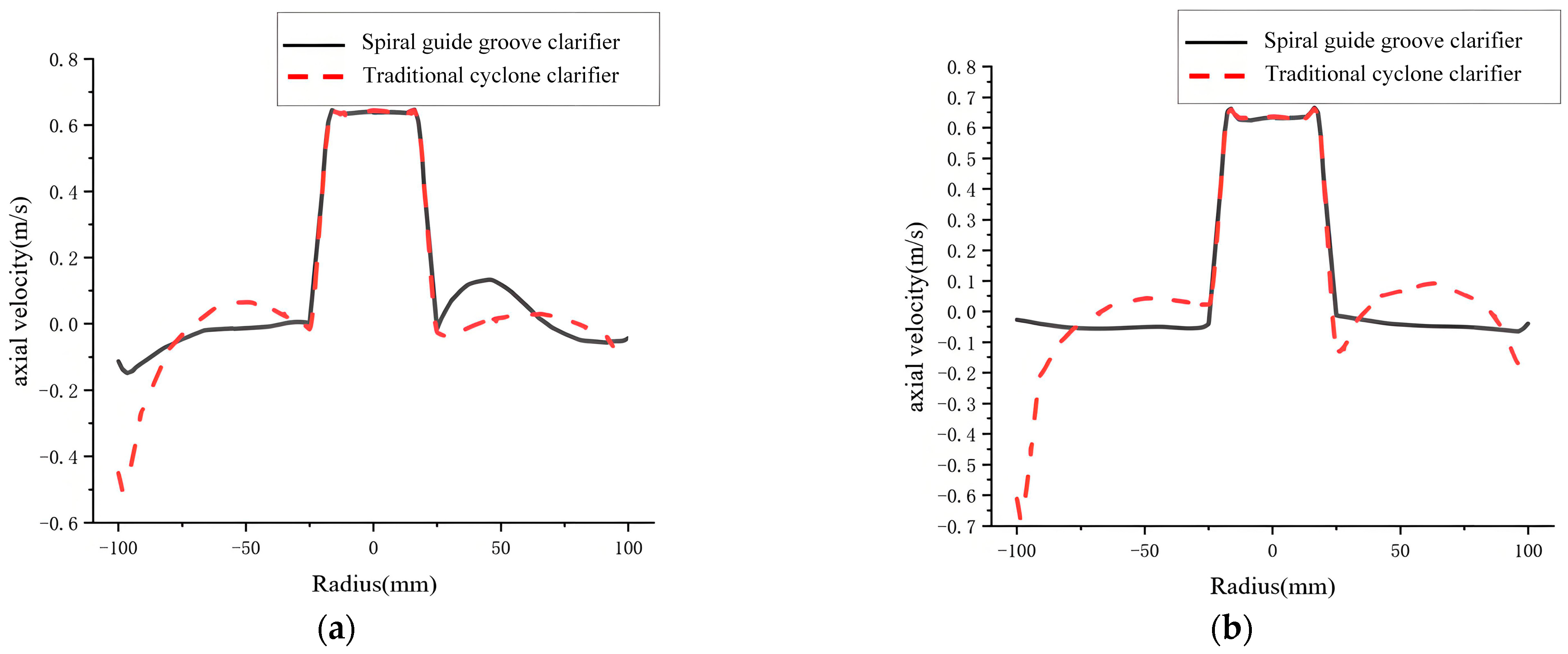

Figure 14 shows axial velocity comparisons for different sections. For the traditional cyclone clarifier at I-I and II-II, the initial axial velocity distribution is less uniform. Velocity is larger near the outer wall, reducing separation time. In the middle, fluid impacts the cone-plates and rebounds. Axial velocity direction changes upward. This causes significant velocity gradient changes at different radii. The spiral guide groove cyclone clarifier has a more uniform axial velocity distribution. Overall, axial velocity is lower than the traditional cyclone clarifier. This is mainly because the spiral guide groove effectively reduces local velocity gradients while guiding the flow. This reduces turbulent disturbance inside the clarifier. The flow field distribution becomes more uniform.

Figure 14.

Axial velocity comparison diagram. (a) I-I section; (b) II-II section; (c) III-III section; (d) IV-IV section.

At Section III-III, axial velocity is lower in the spiral guide groove cyclone clarifier. This extends particle separation time. This section is at the cone-plate location. Combined with the streamline diagram, streamlines are denser in the cone-plate region of the spiral guide groove cyclone clarifier. Lower axial velocity prolongs the time that fluid passes through the cone-plates. This fully utilizes the settling effect of the cone-plates. It favors the settling of particles carried by the fluid on the plate surfaces and gaps. This increases the chance of secondary particle separation. It improves overall separation efficiency.

At Section IV-IV, axial velocities are generally small in the spiral guide groove cyclone clarifier. Under the influence of the lower cone section, the fluid has less impact on underflow particles. It is more stable.

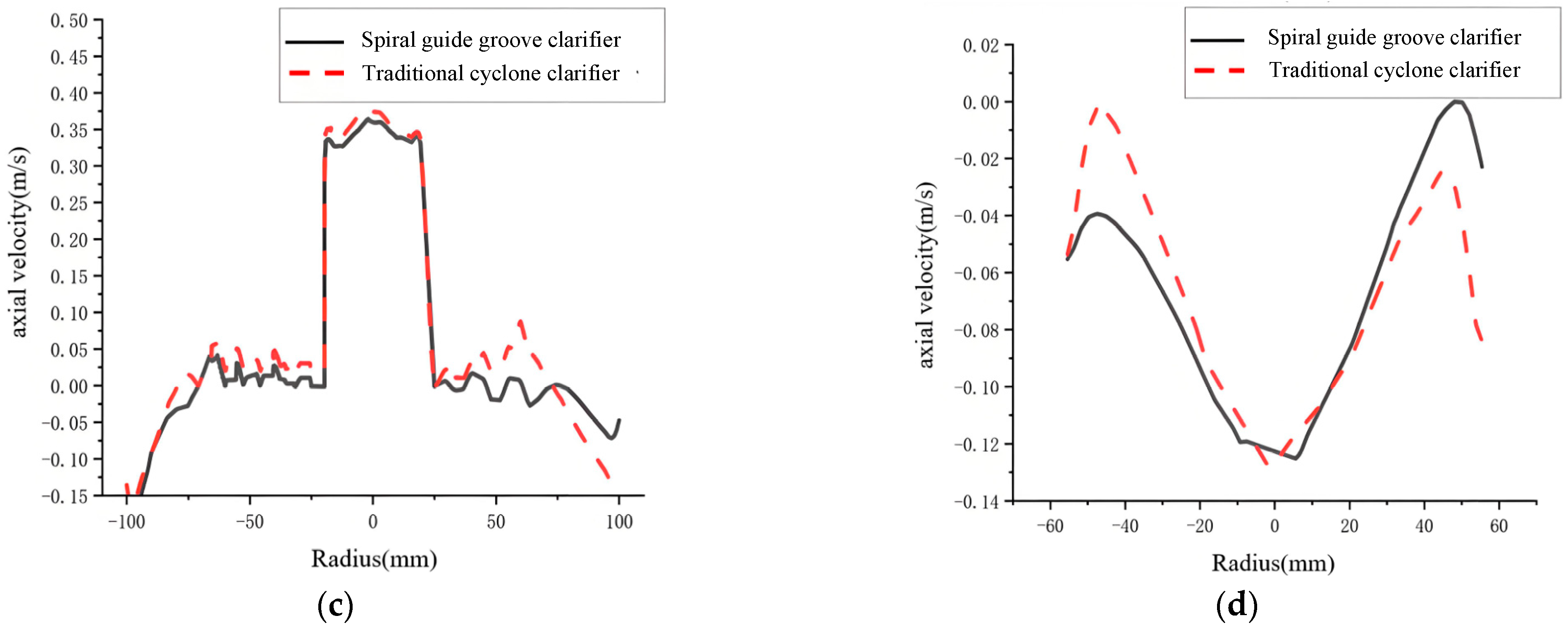

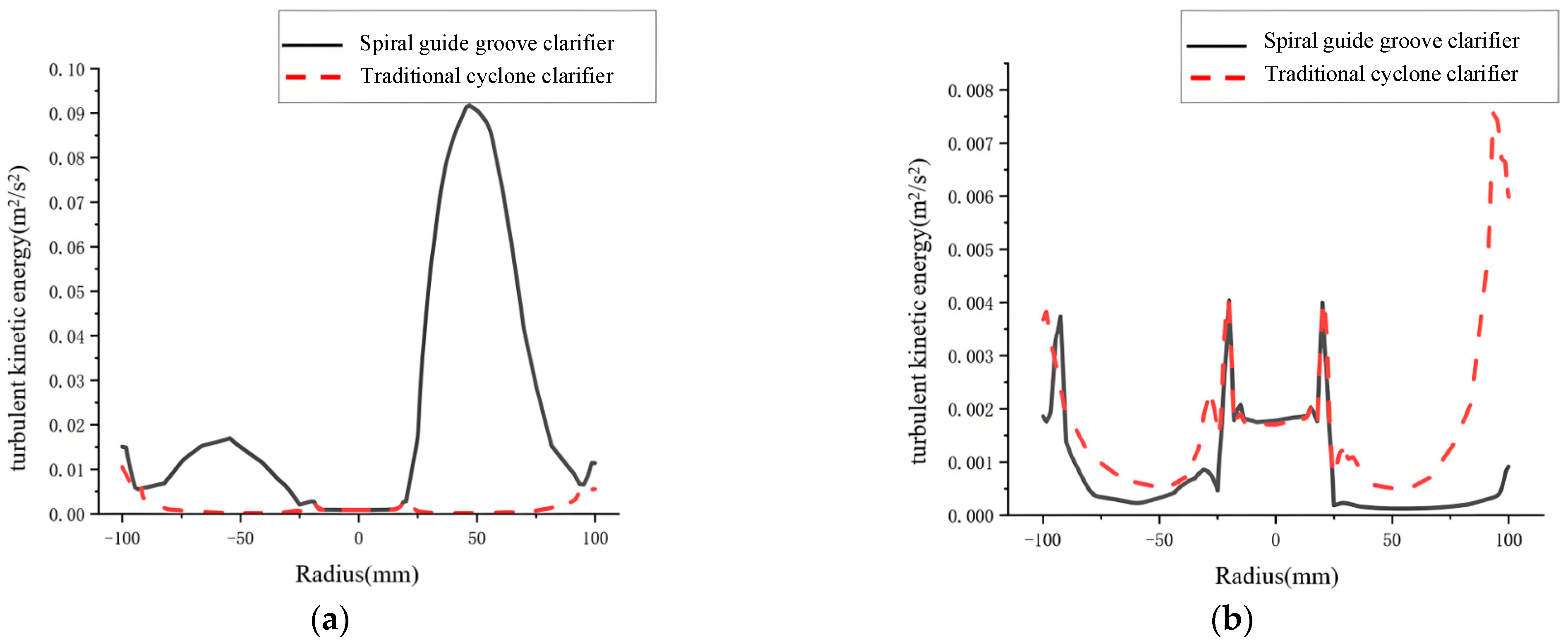

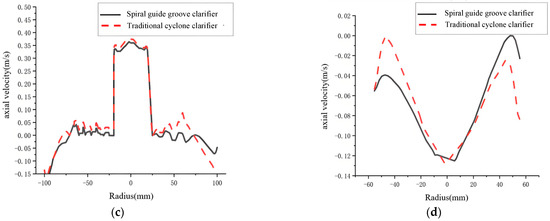

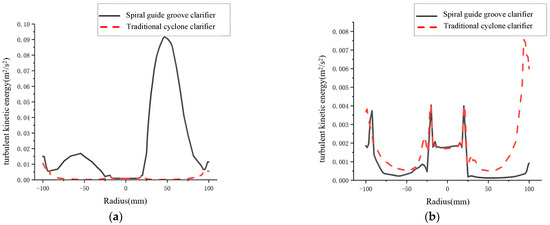

3.4. Turbulent Kinetic Energy Analysis

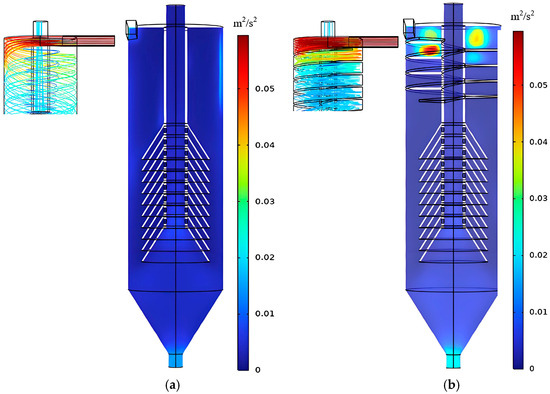

Turbulent kinetic energy is the kinetic energy generated by turbulent motion inside the clarifier. It is an important parameter measuring turbulence intensity in the fluid. It reflects the degree of random fluctuation of fluid velocity in different directions. It affects the motion behavior of fluid and particles and the separation efficiency. Turbulent kinetic energy distribution contours for both clarifiers are shown in Figure 15.

Figure 15.

Turbulent kinetic energy distribution contour plot. (a) Traditional cyclone clarifier; (b) Spiral guide groove cyclone clarifier.

Apart from the influence of the spiral guide groove, the distributions are roughly axisymmetric about the central axis. The traditional cyclone clarifier has a relatively uniform turbulent kinetic energy distribution. The overall fluctuation amplitude is small. The spiral guide groove cyclone clarifier shows obvious local fluctuations in the groove region. This change may affect fluid characteristics and particle separation efficiency.

Figure 16 shows turbulent kinetic energy comparisons on different sections. At Section I-I, turbulent kinetic energy increases significantly in the spiral guide groove cyclone clarifier. Combined with previous streamline and velocity distributions, the groove makes fluid rotate along the groove direction. Tangential velocity is large. Axial velocity is small. This forms the fluctuating characteristics of turbulent kinetic energy locally. Larger turbulent kinetic energy at the inlet can fully disperse particles of different sizes. Rapid separation occurs under a larger centrifugal force. This favors the next settling step.

Figure 16.

Turbulent kinetic energy comparison diagram. (a) I-I section; (b) II-II section; (c) III-III section; (d) IV-IV section.

At Section II-II, the clarifier with the guide groove has lower turbulent kinetic energy. This is because the spiral guide groove optimizes the fluid flow path after Section I-I. It guides the fluid to rotate along the groove direction. The fluid at Section II-II transitions from an initially high turbulence to stable rotational flow. This process reduces disordered turbulent motion. The fluid flow becomes more uniform and steady. This favors the next separation step. It also promotes a stable flow field. It improves the separation environment. It provides a good foundation for subsequent separation and settling.

The cone-plates play an important role in particle settling and secondary separation. At the Section III-III region, turbulent kinetic energy is lower in the spiral guide groove cyclone clarifier. Combined with previous tangential velocity, axial velocity, and streamline analysis, lower turbulent kinetic energy stabilizes turbulence. It reduces the disturbance of particles. Dense streamlines indicate that the cone-plates can settle more particles. Smaller tangential and axial velocities make particles settle onto the cone-plate surfaces more easily by gravity. They move further down along the plates. This achieves secondary settling. It improves settling efficiency.

At Section IV-IV, turbulent kinetic energy is generally low for both. The flow is relatively steady. This favors particle settling.

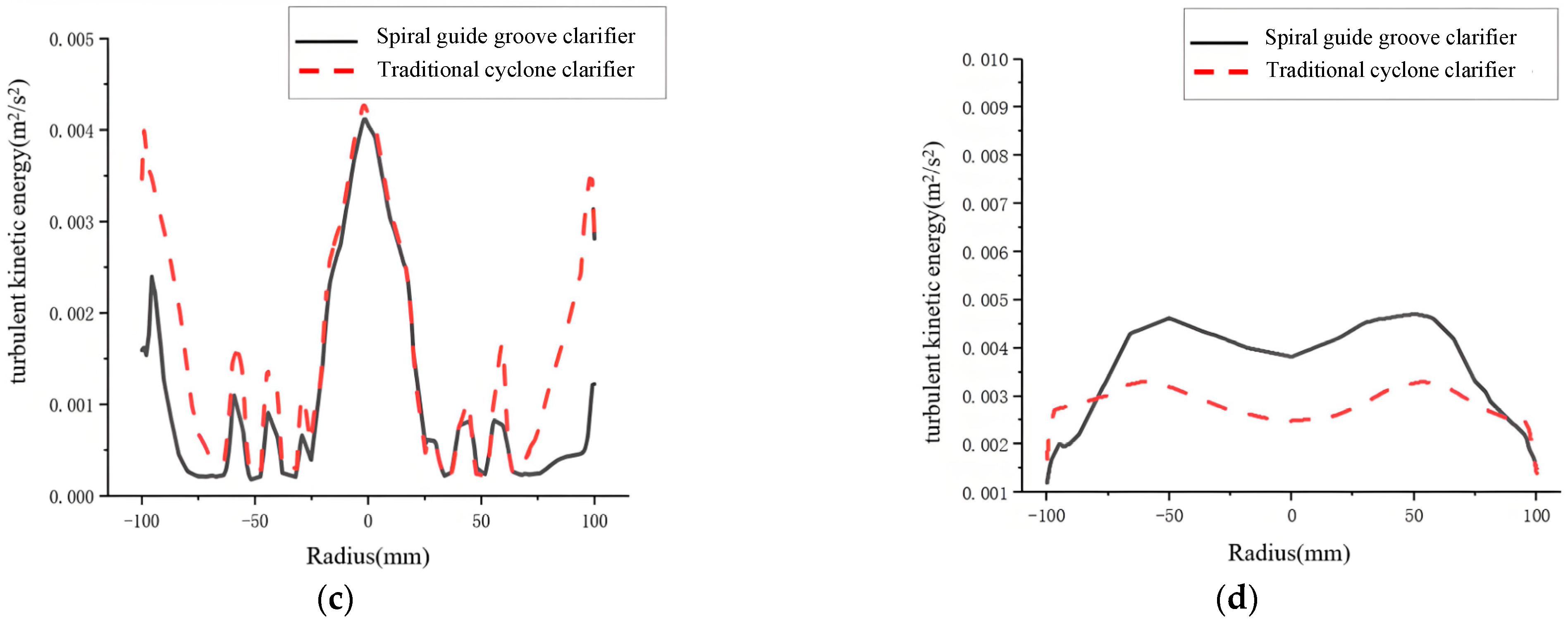

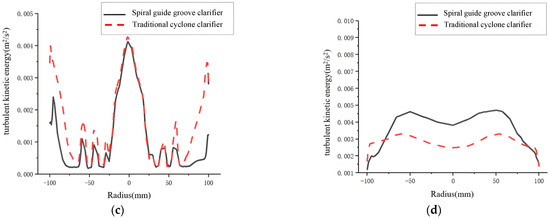

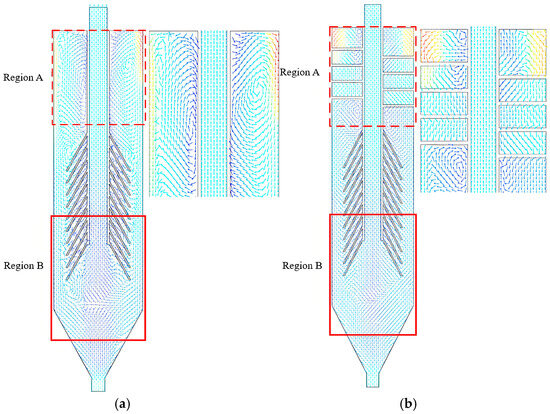

3.5. Velocity Vector Analysis

To further analyze flow field changes, velocity vectors are introduced. Velocity vector diagrams visually show the flow field motion laws. This includes the direction and magnitude of outer and inner vortices. It also shows motion characteristics in different regions. Velocity vector diagrams are shown in Figure 17. Fluid motion is mainly divided into outer and inner vortices. These two motion forms are significantly different. The outer vortex spirals down along the wall towards the underflow. The inner vortex moves up from near the underflow along the center towards the overflow. Particles not discharged in a timely manner from the outer vortex enter the inner vortex region. These two motion forms drive circulatory motion. They further promote more complex dynamic changes in the flow field.

Figure 17.

Velocity vector variation diagram. (a) Traditional cyclone clarifier; (b) Spiral guide groove cyclone clarifier.

As shown in Figure 17a, fluid enters tangentially. Under centrifugal force and wall constraint, it forms an outer vortex spiraling down along the wall. In Area A of the traditional cyclone clarifier, the extended overflow pipe provides more space. Also, fluid is blocked by the cone-plate’s upper surfaces. This forms large-scale circulating vortices in Area A. This explains why at I-I and II-II, axial velocity is larger in the traditional cyclone clarifier. Near the outer wall, axial velocity is downward. In the middle, the axial velocity direction changes upward. Large circulating vortices in Area A cause more turbulent states. This affects particle separation under centrifugal force. It further leads to disordered interaction between inner and outer vortices in Area B below the cone-plates. Velocity vector distribution is irregular. When particles settle downward in the outer vortex, they are easily re-entrained by the disordered flow field. Streamlines appear tangled and crossed. This reflects flow field interference with the separation process. It aggravates particle re-suspension. It reduces separation efficiency.

Figure 17b shows that, in the spiral guide groove cyclone clarifier, the groove structure forces fluid to follow a spiral path in Area A. There are some small vortices at the inlet. As fluid continues down along the groove and wall, the groove suppresses radial disordered flow. Vortex flow in the middle of the groove reduces significantly. Streamlines appear as layered spirals. Vortex strength and distribution are more uniform. This helps improve separation efficiency. After the fluid reaches the groove end, the constraint disappears. The inertia of tangential velocity and the radial pressure gradient become unbalanced. This causes local vortex flow.

In Area B, below the cone-plates, the forced vortex from Area A provides a uniform initial flow field. Tangential and axial velocities are small. Turbulent kinetic energy is small. Under the conical contraction, the outer vortex spirals smoothly down along the wall. The inner vortex moves in an orderly manner upward along the central axis. The flow field has no strong vortex interference. Streamline trajectories are clear and steady. They show regular spiral patterns. This enhances particle separation and settling efficiency.

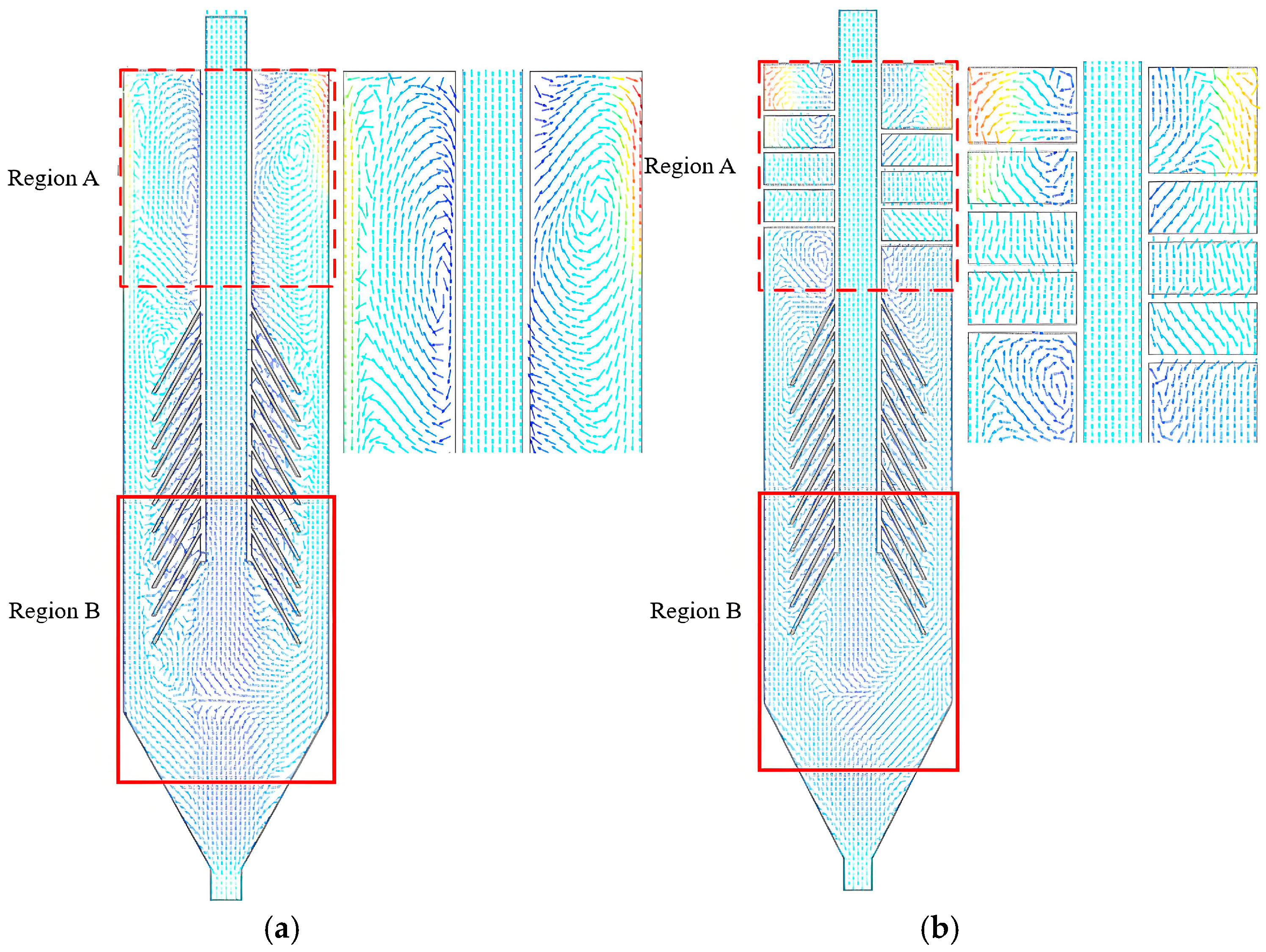

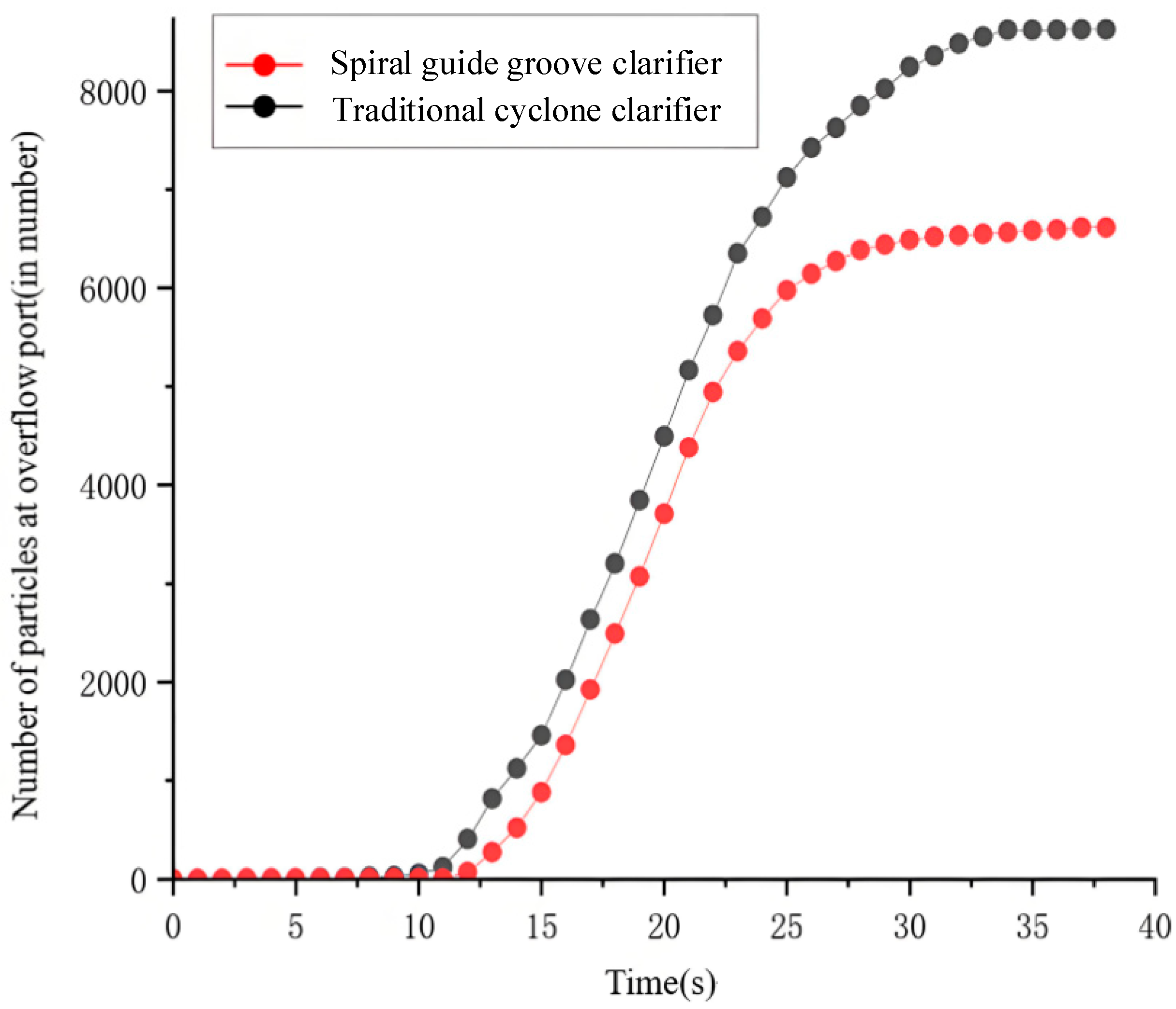

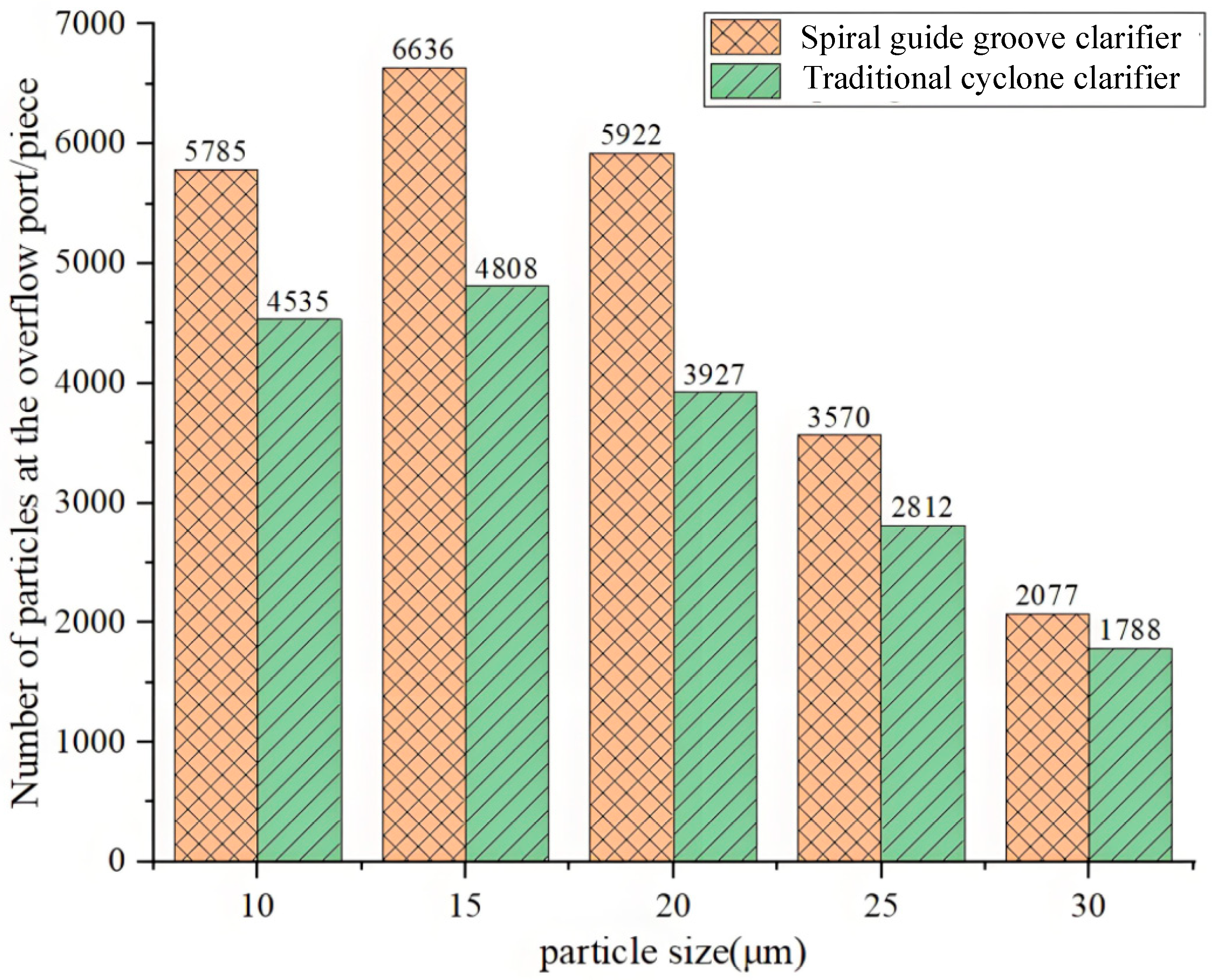

3.6. Particle Removal Efficiency for Different Sizes

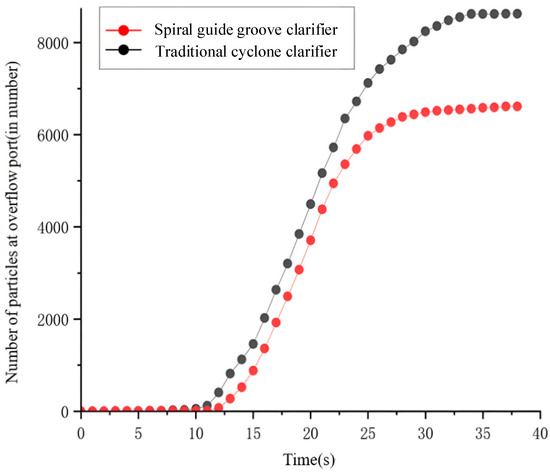

Simulating the pure flow field only allows qualitative analysis of fluid characteristics and motion laws. It does not directly show the impact on particle removal efficiency. To better study the effect of the spiral guide groove on separation performance, particle numbers at the overflow were counted. Figure 18 shows the number of particles at the overflow over time.

Figure 18.

Overflow outlet particle variation over time diagram.

As shown in Figure 18, after particles enter, no particles discharge from the overflow in the first 10 s for both clarifiers. The traditional cyclone clarifier has no guide groove. Axial velocity is larger. Separation time and residence time are short. At 10 s, particles begin to appear in the overflow of the traditional cyclone clarifier. Affected by the guide groove, the spiral guide groove cyclone clarifier has a smaller axial velocity. At 12 s, a few particles enter the overflow pipe through the gap between the groove and cone-plates and are discharged. After 15 s, particles at the overflow continue to increase. Some particles fail to settle effectively in the cone-plate zone. They enter the overflow pipe through holes and flow out. Others are carried by the inner vortex. They flow from the bottom cone-plate area to the overflow pipe. They are finally discharged with the fluid. At 30 s, particle count stabilizes in the spiral guide groove cyclone clarifier. At 34 s, particle count stabilizes in the traditional cyclone clarifier.

The traditional cyclone clarifier recorded 23,990 particles at the overflow outlet, corresponding to a removal rate of 73.34%. The spiral guide groove cyclone clarifier stabilized at 17,870 particles, achieving a removal rate of 80.14%. This represents a 6.8% improvement over the traditional cyclone clarifier. A detailed uncertainty analysis was performed by combining the grid convergence error and the turbulence model error. The Grid Convergence Index (GCI) was calculated to be 2.08%, and the standard uncertainty introduced by the turbulence model was 1.5%, resulting in a combined standard uncertainty of 2.56%. This analysis confirms that the 6.8% efficiency improvement is statistically significant.

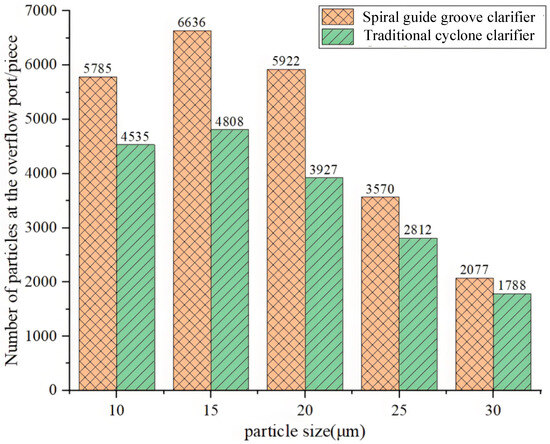

The overflow contains particles of various sizes. To more intuitively study the effect on different particle sizes, particle numbers for 10, 15, 20, 25, and 30 μm particles at the overflow were compared. The result is shown in Figure 19. For particles larger than 25 μm, settling performance is good due to the larger mass and centrifugal force. Particle numbers at the overflow are approximately equal for both devices. This indicates the spiral guide groove has little effect on large particle settling. For 15–20 μm particles, the spiral guide groove cyclone clarifier has better settling performance compared to the traditional cyclone clarifier. This indicates the spiral guide groove mainly improves removal efficiency for particles in the 15–20 μm range. It more effectively suppresses particle overflow from the outlet. It improves separation efficiency. For 10 μm particles, the settling performance of the spiral guide groove cyclone clarifier begins to decrease. This indicates the spiral guide groove structure has less impact on the removal efficiency of very fine particles below 10 μm.

Figure 19.

Diagram of the variation in particle count of different sizes at the overflow outlet.

4. Conclusions

This study systematically compares the flow field characteristics and separation performance of traditional cone-plate cyclone clarifiers and spiral guide groove cyclone clarifiers using numerical simulation. The research is based on the following key assumptions: The fluid is an incompressible water phase. The flow is steady-state turbulent. The standard k-epsilon turbulence model within the RANS framework is used to simulate the flow field. One-way coupling is assumed between particles and the fluid. Based on the above assumptions and simulation analysis, the following main conclusions were drawn:

- The spiral guide groove significantly influences the flow field structure. Compared with the traditional cyclone clarifier, the spiral guide groove integrated at the inlet induces more intensive rotational flow, increasing the number of fluid rotations. This configuration enhances the tangential velocity while reducing the axial velocity, prolonging the particle separation time, and thereby improving overall separation performance.

- In traditional cyclone clarifiers, the outer vortex tends to generate excessive circulating flows and vortices, which hinder particle separation and settling. The spiral guide groove confines the fluid to rotating within the channel, causing localized fluctuations in turbulent kinetic energy and promoting the dispersion of particles of different sizes. After the flow is optimized by the groove, turbulent kinetic energy decreases significantly, the flow field stabilizes, and particle disturbance is reduced—benefiting separation. Although local vortices persist near the groove outlet, the structure overall enhances centrifugal sedimentation efficiency.

- The spiral guide groove clarifier exhibits denser streamlines in the cone-plate zone, accompanied by lower tangential velocity, reduced turbulent kinetic energy, and diminished flow disturbances—all conducive to particle settling. The generally lower axial velocity extends particle residence time, fully utilizing the cone-plate settling effect. As a result, separation efficiency is raised, and effluent quality is improved.

- In the underflow region of the spiral guide groove clarifier, streamlines are sparser, and tangential velocity, axial velocity, and turbulent kinetic energy are all lower, effectively suppressing the intensity of both the outer and inner vortices. Under the contracting action of the conical section, the outer vortex spirals steadily downward along the wall, while the inner vortex moves upward in an orderly manner along the central axis. Free from strong vortex interference, the flow field demonstrates clear and stable spiral trajectories, significantly boosting particle separation and settling efficiency.

- The spiral guide groove clarifier achieves superior particle removal efficiency across all particle sizes investigated. Compared to the conventional design, the total removal efficiency is improved by 6.8%. Analysis of removal rates for 10, 15, 20, 25, and 30 μm particles shows the most notable enhancement in the 15–20 μm range, confirming that the spiral guide groove effectively suppresses the carry-over of particles within this size interval.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.Z.; data curation, K.G. and Q.L.; formal analysis, L.J. and A.L.; investigation, A.L.; methodology, P.L. and A.L.; resources, P.L.; software, K.G. and A.L.; validation, K.G.; validation, Q.L.; visualization, L.J.; writing—original draft, K.G.; writing—review and editing, Y.Z., Q.L., and P.L.; funding acquisition, Y.Z. and A.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province, China, grant numbers ZR2023QE121; and the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant numbers 22408213.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Huang, D.; Liu, Z.; Wang, W. Evaluating the impaction of coal mining on Ordovician karst water through statistical methods. Water 2018, 10, 1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, Y. Research review of coal mine water treatment technology. Asian J. Adv. Res. Rep. 2022, 16, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Gao, Y.; Jiang, X.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, W. Analysis on the characteristics of water pollution caused by underground mining and research progress of treatment technology. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2021, 2021, 9984147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gumińska, J.; Plewa, F.; Grodzicka, A.; Gumiński, A.; Rozmus, M.; Michalak, D. Economic analysis of the application of the technological system for removing suspended solids from mine drainage waters. Energies 2021, 14, 8232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atallah, C.; Mosadeghsedghi, S.; Kenari, S.L.D.; Hudder, M.; Morin, L.; Volchek, K.; Mortazavi, S.; Ben Salah, I. Removal of heavy metals from mine water using a hybrid electrocoagulation-ceramic membrane filtration process. Desalination Water Treat. 2024, 320, 100730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, C.; Zhang, Y.; Tao, Y.; Zhu, X. Competitive adsorption behavior and adsorption mechanism of limestone and activated carbon in polymetallic acid mine water treatment. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 23561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, M.S.F.; Assila, O.; Fonseca, A.M.; Parpot, P.; Valente, T.; Rombi, E.; Neves, I.C. Acid mine drainage precipitates from mining effluents as adsorbents of organic pollutants for water treatment. Molecules 2024, 29, 3521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Zhang, Q. Mine water treatment, resource utilization and prospects in coal mining areas of western China. Mine Water Environ. 2024, 43, 210–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, E.; Guo, W.; Tan, Y.; Wu, D.; Zhang, Y.; Wen, P.; Ma, Z. Green coal mining and water clean utilization under Neogene aquifer in Zhaojiazhai coalmine of central China. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 368, 133134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.; Huang, C.; Guo, Z. Treatment process and engineering practice for mine drainage water with high suspended solids and high salinity. Energy Environ. Prot. 2013, 27, 30–32+42. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Thorndahl, U. Improvement of sludge sedimentation by installation of upward flow clarifiers. Water Sci. Technol. 1994, 29, 227–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, H.-J.; Park, J.-W.; Jeong, K.J.; Hwang, N.M.; Hong, S.-T.; Han, H.N. Effect of pulsed electric current on TRIP-aided steel. Int. J. Precis. Eng. Manuf. Green Technol. 2019, 6, 315–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Saedi, R.; Smettem, K.; Siddique, K. The impact of biodegradable carbon sources on microbial clogging of vertical up-flow sand filters treating inorganic nitrogen wastewater. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 691, 360–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, B.-Y.; Wei, D.-Z.; Gao, S.-L.; Liu, W.-G.; Feng, Y.-Q. Numerical and experimental studies of flow field in hydrocyclone with air core. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2014, 24, 2642–2649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Cui, B.; Wei, D.; Song, T.; Feng, Y. Numerical analysis of the flow field and separation performance in hydrocyclones with different vortex finder wall thickness. Powder Technol. 2019, 345, 567–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Fu, W.; Jiang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, X.; Li, X.; Wang, H. The separation performance of a parabolic hydrocyclone in separating iron from red mud. Powder Technol. 2023, 416, 118205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Wang, W.B.; Feng, J.A.; Ying, R. Numerical simulation of the solid-liquid separation flow field in hydrocyclone. Comput. Simul. 2016, 33, 210–213. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Ghodrat, M.; Kuang, S.B.; Yu, A.B.; Vince, A.; Barnett, G.D.; Barnett, P.J. Numerical analysis of hydrocyclones with different vortex finder configurations. Miner. Eng. 2014, 63, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Li, X.; Liu, P.; Li, X.; Jiang, L.; Yang, G. Study on the separation performance of honeycomb cone hydrocyclone. Int. J. Coal Prep. Util. 2025, 45, 1051–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirom, K.; Devi, T.T. Application of computational fluid dynamics in sedimentation tank design and its recent developments: A review. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2022, 233, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salah Al-Kizwini, R. Improvement of sedimentation process using inclined plates. Mesopotamia Environ. J. 2015, 2, 100–114. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, K.; Li, Y.; Ren, S.; Yang, P. A case study on settling process in inclined-tube gravity sedimentation tank for drip irrigation with the Yellow River water. Water 2020, 12, 1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zha, Y.D.; Hou, P.; Liu, Z.Y.; Wang, K.Y.; Li, Y.K.; Wang, C.X. The impact of pipe inclination on sediment deposition at the sedimentation basin in the Yellow River. Water Sci. Technol. 2023, 42, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirom, K.; Devi, T.T. Determining the optimum position and size of lamella packet in an industrial wastewater sedimentation tank: A computational fluid dynamics study. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2022, 233, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castilho, L.R.; Medronho, R.A. A simple procedure for design and performance prediction of Bradley and Rietema hydrocyclones. Miner. Eng. 2000, 13, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Liu, P.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, L. Numerical simulation and experimental study on a cone-plate clarifier. Adv. Mech. Eng. 2019, 11, 1687814019826788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, P.; Xiao, L.; Chang, L.; Yan, F.; Jiang, L. Effect of cone-plate clarifier structure parameters on flocculation efficiency. Separations 2022, 9, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dianyu, E.; Xu, G.; Fan, H.; Cui, J.; Tan, C.; Zhang, Y.; Zou, R.; Kuang, S.; Yu, A. Numerical investigation of hydrocyclone inlet configurations for improving separation performance. Powder Technol. 2024, 434, 119384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.T.; Wang, D.S.; Su, Y.X. Performance improvement of cyclone separator by integrated compact bends. Powder Technol. 2019, 353, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Wang, X.; Jiang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, X.; Li, X.; Wang, H. Effect of spiral vanes width on the separation performance of a hydrocyclone. Physicochem. Probl. Miner. Process. 2023, 59, 173563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrêa, R.G.; Andrade, J.R.; de Souza, F.J. Improving separation prediction of cyclone separators with a hybrid URANS-LES turbulence model. Powders 2023, 2, 607–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasilewski, M.; Anweiler, S.; Masiukewicz, M. Characterization of multiphase gas-solid flow and accuracy of turbulence models for lower stage cyclones used in suspension preheaters. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 2019, 27, 1618–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Chen, G.; Yan, X. Evaluation and improvement of particle collection efficiency and pressure drop of cyclones by redistribution of dustbins. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2018, 139, 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves de Moro Martins, D.; Andrade, J.R.; Ribeiro Duarte, C.A.; de Vasconcelos Salvo, R.; de Souza, F.J. A large eddy simulation study of cyclones: The effects of interparticle collisions on erosion prediction. J. Energy Power Technol. 2022, 4, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, S.K.; Shukla, P.; Ghosh, P. The effect of modeling of velocity fluctuations on prediction of collection efficiency of cyclone separators. Appl. Math. Model. 2013, 37, 5774–5789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsayed, K.; Lacor, C. Modeling analysis and optimization of air cyclones using artificial neural network response surface methodology and CFD simulation approaches. Powder Technol. 2011, 212, 115–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, S.; Sivapirakasam, S.P.; Sakthivel, M.; Krishnaraj, R.; Leta, T.J. Investigation on hydrocyclone for increasing the performance by modification of geometrical parameters through CFD approach. Desalination Water Treat. 2021, 244, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, N.; Pericleous, K.A.; Drake, S.N. The prediction of hydrocyclone performance with a mathematical model. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Hydrocyclones, Oxford, UK, 30 September–2 October 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Schuetz, S.; Mayer, G.; Bierdel, M.; Piesche, M. Investigations on the flow and separation behaviour of hydrocyclones using computational fluid dynamics. Int. J. Miner. Process. 2004, 73, 229–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heydari, M.; Khoshkonesh, A. The comparison of the performance of Prandtl mixing length, turbulence kinetic energy, k-ε, RNG and LES turbulence models in simulation of the positive wave motion caused by dam break on the erodible bed. Indian J. Sci. Technol. 2016, 9, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gronald, G.; Derksen, J. Simulating turbulent swirling flow in a gas cyclone: A comparison of various modeling approaches. Powder Technol. 2011, 205, 160–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Cheng, X.; Zheng, X.; Chen, H. Reynolds-averaged Navier-Stokes equations describing turbulent flow and heat transfer behavior for supercritical fluid. J. Therm. Sci. 2020, 30, 191–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinz, S. The large eddy simulation capability of Reynolds-averaged Navier-Stokes equations: Analytical results. Phys. Fluids 2019, 31, 021702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giancarlo, A. Reynolds-averaged Navier–Stokes equations for turbulence modeling. Appl. Mech. Rev. 2009, 62, 040802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Chen, F.G.; Liu, X.H.; Ge, W.; Li, J.H. Discrete Particle Simulation of Gas-Solid Two-Phase Flows with Multi-Scale CPU-GPU Hybrid Computation. Chem. Eng. J. 2012, 207, 746–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.L.; Kou, M.Y.; Xu, J.; Guo, X.Y.; Du, K.P.; Shen, W.; Sun, J. DEM Simulation of Particle Size Segregation Behavior During Charging Into and Discharging From a Paul-Wurth Type Hopper. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2013, 99, 314–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.