Abstract

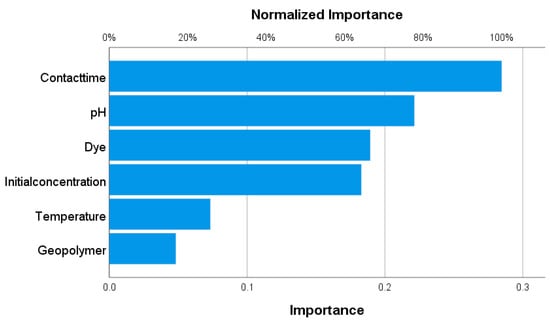

The main goal of this study is to address the problem of environmental water pollution caused by organic dyes through waste valorization by synthesizing geopolymer-based adsorbents. In this work, geopolymers were synthesized using fly ash modified with chitosan and polyvinyl alcohol as a starting material. The obtained materials were characterized by scanning electron microscopy, Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy, X-ray diffraction, and determination of the point of zero charge. We examined the adsorption potential for organic dye (methylene blue, brilliant green, crystal violet) removal through the influence of contact time, initial pH and concentration of adsorbate solution, and temperature on adsorption. The obtained results were analyzed using theoretical kinetics and isotherm models. Interpretation of the obtained results was performed using the Box–Behnken design and chemometric methods of multivariate analysis. The findings showed that modification with chitosan significantly enhanced the adsorption efficiency of the synthesized materials up to 95.9% for methylene blue adsorption. The parameters identified as having the greatest influence on the adsorption process were contact time, pH-value, initial dye concentration, and the type of dye being adsorbed.

1. Introduction

The constant development and progress of industry over the past 100 years have led to significant negative effects on the environment through the emission of various pollutants into water, air, and soil. Special attention is given to organic pollutants present in aquatic ecosystems, which can have a detrimental impact on human health and the survival of living organisms. Organic pollutants include synthetic dyes, pharmaceutical residues, pesticides, artificial sweeteners, hormones, sterols, UV filters, and numerous other organic compounds generated by human activities. Synthetic organic dyes have attracted considerable attention as pollutants due to their chemical stability in the presence of light, heat, and oxidants, as well as their resistance to biodegradation [1,2,3]. Approximately 10,000 different types of synthetic dyes are estimated to be produced annually, in quantities exceeding 700,000 tons. They are mainly used in the textile industry, but also in other industrial sectors such as printing, plastics, cosmetics production, the pulp and paper industry, the leather industry, as well as in the dye manufacturing industry itself [2,4]. Around 50% of the dye used during textile dyeing remains unbound to the fabric, making the textile industry one of the biggest polluters. It is estimated that this industry is responsible for between 17 and 20% of water pollution with organic dyes during fabric production and dyeing processes [4,5]. The presence of these chemical compounds, even in small amounts, leads to significant changes in refractive index and light absorption, which disturb the photosynthesis process in aquatic plants. Furthermore, organic dyes reduce the amount of dissolved oxygen, negatively affecting respiration processes in aerobic organisms [6,7]. The presence of organic dyes in water, even at very low concentrations, can cause various health problems in humans, such as skin irritation, eye burns, nausea, respiratory problems, increased heart rate, diarrhea, vomiting, and cancer [1,4,6,8].

The development of an efficient and reliable technique for the removal of organic dyes from water, therefore, is highly important. Literature review reveals various techniques explored for the removal of synthetic organic dyes from aquatic ecosystems. These techniques include membrane filtration [9,10], ion exchange [11,12], reverse osmosis [13], enzymatic degradation [8,14], as well as advanced oxidation processes: photocatalysis [15], ozonation, and UV/chlorine process [16]. These processes are characterized by very high operational costs and limited efficiency under certain conditions; moreover, the application of some of them may result in the formation of by-products more harmful to the environment than the initial compounds [17]. In contrast, the adsorption process is characterized by low cost, simple design, easy maintenance, high efficiency, and applicability on different scales [7]. It is particularly important to emphasize that the adsorption process does not produce harmful by-products [1]. Among the most efficient adsorbents are synthetic materials such as activated carbon and various metal oxides, which are not widely applied in industry due to their high cost and regeneration requirements [7,18,19]. Waste valorization and its application as adsorbents have emerged as an economically and environmentally viable solution, making the adsorption process cheaper and more accessible [19].

Geopolymers represent a relatively new type of inorganic polymeric materials rich in aluminum and silicium. The synthesis of these materials takes place at temperatures up to 100 °C, which contributes to the reduction in CO2 emissions. Various materials rich in aluminum and silicon oxides, such as kaolin, zeolite [20,21], and various natural clays [22,23], can be used as raw materials for the synthesis of geopolymers. In accordance with modern concepts of circular economy and sustainable development, increasing attention has recently been paid to the use of industrial waste materials as precursors for geopolymer synthesis. Among them, fly ash [24,25], metakaolin [26], ground granulated blast furnace slag [27], and red mud [28,29] stand out. In this study, geopolymers were synthesized using fly ash as raw material. The fly ash we used was generated as a by-product during coal combustion in thermal power plants in the Republic of Serbia. It is estimated that about 6 million tons of this waste material are deposited annually, making it the most widespread type of industrial waste [30].

The formation mechanism of these materials represents a set of chemical reactions through which aluminosilicate minerals present in the starting material are integrated [31]. This reaction is complex and includes the processes of dissolution, coagulation, condensation, polymerization, restructuring, and polycondensation [32]. The mechanism of this chemical reaction takes place in four stages: initially, aluminosilicate particles dissolve in the alkaline solution. The next stage is nucleation i.e., the formation of centers around which clusters are formed. Subsequently, oligomerization occurs, during which small chains and rings are formed, and finally, polymerization takes place, forming the structure of the final material in the form of a 3D network [33,34]. The entire geopolymerization process, as well as the hardening of the geopolymer mortar, takes place at room temperature, while drying in an oven can accelerate this process [35].

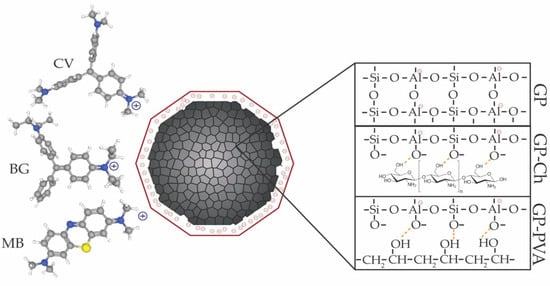

A review of the literature has shown that various modifications of fly ash have been used as adsorbents for a wide range of environmental pollutants: heavy metals [36,37,38,39], rare earth elements [40,41], pharmaceuticals [42], dyes [43,44,45,46,47], pesticides [48], and volatile organic compounds [49,50]. Also, the addition of organic polymeric components, such as polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) [51,52] and chitosan (Ch) [53], leads to the crosslinking of organic and inorganic chains, resulting in increased mechanical strength. Considering that both PVA [54,55] and Ch [56] possess good adsorption activities by themselves, the main goal of this study is to improve the adsorption properties of fly ash–based geopolymers by adding small amounts of PVA and Ch. In this study, we examined the adsorption affinity of the obtained geopolymeric materials towards synthetic organic dyes. Methylene blue (MB), crystal violet (CV), and brilliant green (BG) were selected as examples of cationic dyes most commonly used in industry. MB represents a phenothiazine dye, while CV and BG are triphenylmethane dyes. The material was characterized, and the parameters of the adsorption process were examined, including contact time, temperature, initial concentration, and solution pH. Process optimization and the examination of the influence of process parameters on the adsorption efficiency of geopolymer-based materials were carried out using Response Surface Design (Box–Behnken Design) and modelling by Artificial Neural Network.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals

Fly ash, generated in the lignite combustion process, was sampled from the Nikola Tesla thermal power plant in Obrenovac (Serbia). Used for the synthesis of geopolymers besides fly ash were chitosan (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and polyvinyl alcohol (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). Alkaline activation was performed with NaOH (Centro-chem, Lublin, Poland) and Na2SiO3 (Beohemik, Belgrade, Serbia). Testing was conducted for textile dyes methylene blue (Centro-chem) crystal violet, (Sigma-Aldrich), and brilliant green (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Solutions were prepared using demineralized water (18 MΩ·cm−1).

2.2. Synthesis of Materials

In this study, different samples of fly ash-based geopolymer were synthesized through the alkaline activation of fly ash. 100 g of fly ash was activated using 100 cm3 NaOH:Na2SiO3 = 1:1 (v/v) mixture, with the NaOH solution concentration being 8 mol dm−3. The obtained suspension was mixed manually and with a stirrer (500 rpm) to obtain a fresh geopolymer mortar. After drying the geopolymer mortar at room temperature (25 ± 5 °C) for 24 h and heating at 80 ± 2 °C for 6 h in an oven (VIMS Elektrik, Tršič, Serbia), the result was geopolymer sample GP. Geopolymer samples modified with Ch (GP-Ch) and PVA (GP-PVA) were prepared by mixing fresh geopolymer mortar with 2.5 g of organic polymer. Upon homogenization, prepared mixtures were also dried (25 °C, 24 h) and heated (80 °C, 6 h). Grinding of the obtained geopolymer samples followed after 28 days, after which the materials were sieved through a 63 μm sieve (CISA BA200N, Barcelona, Spain), washed with water to remove excess hydroxides, and subsequently characterized.

2.3. Material Characterization

The morphology and surface structure of the obtained materials were examined using scanning electron microscopy (SEM, TESCAN MIRA 3 XMU, Brno, Czech Republic) operated at 20 keV with a secondary electron detector.

The phase composition of the obtained materials was determined by powder X-ray diffraction (XRD) using a Rigaku SmartLab diffractometer (Rigaku Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) with CuKα radiation (λ = 1.54 Å) in the 2θ range from 10° to 70°, with a step of 0.02° s−1.

The functional groups and bonds present in the geopolymers were identified using Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy. ATR-FTIR spectra were recorded on a Nicolet iS10 FTIR spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) in the wavenumber range of 400–4000 cm−1.

The point of zero charge (pHPZC) of the examined materials was determined by immersing 0.05 g of the sample in cuvettes containing 20 cm3 of 0.01 mol dm−3 NaCl solution, with the initial pH (pHᵢ) adjusted to 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, and 12 (±0.01) using 0.1 mol dm−3 HCl or 0.1 mol dm−3 NaOH. Before sealing, nitrogen was purged into the cuvettes, which were then shaken for 48 h at room temperature. The final pH (pHf) was measured, and the ΔpH–pHi dependence was plotted to determine the pHPZC [57].

2.4. Adsorption Experiments

The materials we obtained were used for the adsorption of dyes from single-component aqueous solutions. MB represents a phenothiazine dye, while CV and BG are triphenylmethane dyes. The structures of these dyes and their basic physicochemical properties are shown in Figure S1 and Table S1 (Supplementary Materials). Adsorption experiments were carried out in glass Erlenmeyer flasks at a stirring speed of 150 rpm. A mass of 0.05 g of adsorbent material and 20 cm3 of dye solution with an initial dye concentration of 20 mg dm−3 were used. Dye concentrations were determined using a UV–Vis spectrophotometer (UV 21, ONDA, Mussolente, Italy), at the following wavelengths: MB 675 nm, CV 582 nm, and BG 630 nm. Adsorption efficiency (1) and adsorption capacity (2) were calculated based on the following equations:

In Equations (1) and (2), Efficiency (%) represents the adsorption efficiency, C0 (mg dm−3) is the dye concentration at the beginning of the adsorption process, C (mg dm−3) is the dye concentration after adsorption, q (mg g−1) is the adsorption capacity, m (g) is the mass of the adsorbent used, and V (dm3) represents the volume of the dye solution.

The adsorption process was optimized by modifying the parameters: initial pH value of the solution, initial dye solution concentration, contact time between adsorbate and adsorbent, and the temperature at which the process was conducted. The effect of the initial pH of the adsorbate solution on adsorption was studied by adjusting the initial pH to 4, 6, and 8 with an accuracy of ±0.01, using diluted HCl and NaOH solutions. In addition, an experiment without pH adjustment was conducted, whereby the pH values of the solutions were 6.5 for MB, 7.9 for CV, and 6.7 for BG. The effect of contact time was studied with 0.25 g of material and 100 cm3 of dye solution. The experiment was carried out at 25 °C, the initial concentration of the solution was 30 mg dm−3, and the pH value was not adjusted. Samples were taken at previously determined time intervals of 5, 15, 30, 60, 120, and 180 min. The obtained experimental results were analyzed using theoretical models: pseudo-first (3) [58] and pseudo-second order (4) [59], intraparticle diffusion (5) [60], and the Elovich model (6) [61].

In Equations (3)–(6), qe and qt (mg g−1) represent the amounts of dye adsorbed at equilibrium and at time t (min), respectively; k1 (min−1) and k2 (g mg−1 min−1) are the pseudo-first- and pseudo-second kinetic order rate constants; kid (mg g−1 min−1/2) represents the intraparticle diffusion rate constant, which can be determined from the slope of the linear plot of qt versus t1/2, and the constant C (mg g−1) is the intercept; β (g mg−1) and α (mg g−1 min−1) are the surface coverage and initial rate constant of the Elovich model, respectively.

The effect of the initial solution concentration was examined using 0.05 g of material and 20 cm3 of solutions with concentrations of 30, 40, 50, 75, 100, and 150 mg dm−3. The contact time was 180 min and the temperature was 25 °C, without pH adjustment. The obtained experimental results were analyzed using theoretical isotherm models: the Langmuir (7) [62], Freundlich (8) [63], Temkin (9) [64], and Dubinin–Radushkevich (10) [65] adsorption isotherms:

In Equations (7)–(10), qe (mg g−1) represents the amount of dyes adsorbed at equilibrium; Ce is the equilibrium dye concentration (mg dm−3); Q0 is the amount of solute adsorbed per unit mass of adsorbent required for monolayer coverage of the surface (mg g−1); b represents a constant related to the heat of adsorption (dm3 mg−1); Kf (mg g−1(mg dm−3)−1/n) is the Freundlich constant, related to the adsorption capacity; 1/n is the heterogeneity factor; A is the Temkin isotherm equilibrium binding constant (dm3 g−1); bT is the Temkin constant related to the heat of adsorption (J/mol); R is the gas constant (8.3145 J mol−1 K−1), and T (K) represents the absolute temperature; qm is the maximum adsorption capacity (mg g−1); β is the constant related to adsorption energy (mol2 J−2); and E represents the mean adsorption energy (kJ mol−1).

We examined the influence of temperature on the dye adsorption process on geopolymer materials at three different temperatures: 30, 35, and 45 °C. A geopolymer mass of 0.05 g was used, with an initial concentration of 20 mg dm−3, and a contact time of 180 min. Based on the experimental data and using Equation (11), the thermodynamic parameters ∆H° and ∆S° were determined from the slopes and intercepts of the lnK–1/T dependencies, respectively. The ∆G° values were calculated from the corresponding ∆H° and ∆S° values according to the van’t Hoff Equation (12):

To examine the behaviour of the obtained geopolymeric adsorbents during the adsorption from the water samples having a complex matrix, adsorption experiments were performed on three wastewater samples (W1, W2, and W3). Wastewater samples were spiked with the examined dyes to an initial concentration of 30 mg dm−3, and optimized adsorption parameters were applied. The sampling and pH of wastewater samples, collected in the period October–November 2024, are shown in Table S2 in the Supplementary Materials.

2.5. Box–Behnken Design for Adsorption Parameter Optimization

Analysis of the results we obtained was performed using the Minitab software package, version 21.2. Response surface design (Box–Behnken Design) was applied for the optimization of the adsorption process and 3D modelling of the obtained experimental parameters. The modelling of the adsorption process efficiency was conducted using the following continuous factors: pH, initial dye concentration, temperature, and contact time, while the categorical factors were geopolymer material (GP, GP-Ch, and GP-PVA) and dye type (MB, CV, BG). The modelling of experimental parameters was based on the following Equation (13) [66,67,68]:

Here, Efficiency represents the adsorption efficiency; β, βi1, βi2, and βi3 are linear coefficients; Xi and Xj are continuous factors.

2.6. Computational Modelling by Artificial Neural Networks

Artificial neural networks (ANNs) were used to correlate between the investigated materials and dyes, identify the parameters that had the most significant impact on the adsorption process, and simplify and reduce the data set. All analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics 26 (IBM Statistics software).

Unlike many statistical models that assume a linear relationship between response and prediction variables and their normal distribution, ANNs are able to map nonlinear relationships between system characteristics. ANNs develop a mapping of input and output variables, which can then be used to predict the desired output as a function of the corresponding inputs.

The network will strive to minimize the sum of squared errors (the sum of squared differences between the target network and the actual output for a given input vector or set of vectors). Three different criteria were used to determine the effectiveness of each selected network model: root mean square error (RMSE), bias (representing the number of neurons producing a constant signal), and coefficient of determination [69,70,71].

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Material Characterization

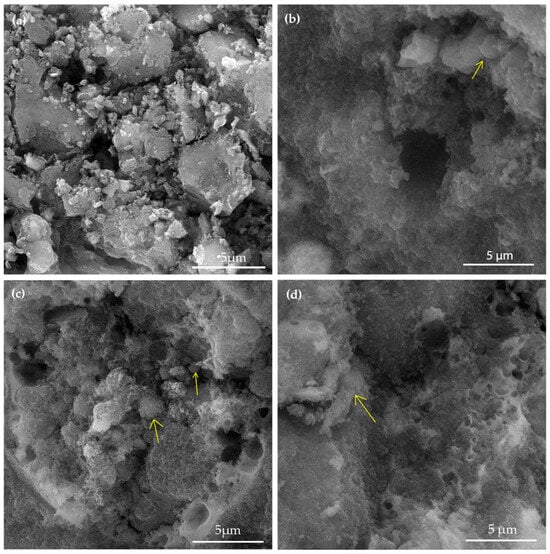

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was used to investigate the surface morphology and structure of the geopolymer samples, as presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Scanning electron micrographs of (a) fly ash, (b) GP, (c) GP-Ch, and (d) GP-PVA.

Unlike the microstructure of fly ash (Figure 1a), the surfaces of the obtained geopolymer materials were more uniform due to the dissolution of the silicate phase and the formation of the geopolymer matrix (N-A-S-H gel) [72,73,74]. Relatively heterogeneous surfaces of synthesized geopolymers were characterized by the presence of microcracks and pores of different sizes, which can lead to an increase in the surface area available for adsorption. In the structure of the obtained geopolymers, some unreacted and partially reacted fly ash particles, i.e., cenospheres [75] (marked with yellow arrows in Figure 1b–d), could still be found.

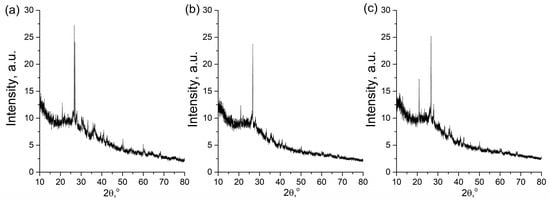

The phase composition of the geopolymer was examined using the XRD method. The results obtained from the XRD analysis are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

XRD spectra of (a) GP, (b) GP-Ch, and (c) GP-PVA.

The XRD spectra of the examined materials were quite similar, as we expected given the similar preparation method. Diffraction maxima appeared at 2θ values characteristic of the mineral quartz: 20.9°, 26.7°, 39.5°, 40.9°, 42.5°, and 50.1° (PDF #46-1045), and of the mineral mullite: 26.5°, 31.0°, 33.2° and 35.5° (PDF #15-0776). Also, at 2θ values between 10° and 40°, the spectra exhibited the highest background intensity, i.e., a characteristic “hump”, which indicates the presence of an amorphous phase [34,76]. In addition, the characteristic peaks at the 2θ values corresponding to quartz and mullite were of significantly lower intensity compared to those of pure minerals, indicating a transition from a crystalline to an amorphous phase. The obtained spectra are characteristic of this material and are consistent with the spectra of geopolymer materials prepared in a similar way, as reported in the studies by other authors [77,78,79].

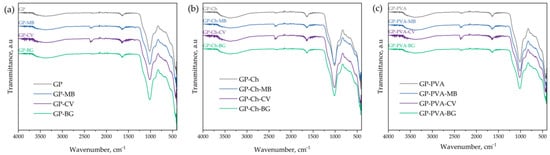

The identification of surface functional groups and the potential interaction between the organic dye and geopolymer materials was performed on the basis of FTIR spectra (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

FTIR spectra of (a) GP, (b) GP-Ch, and (c) GP-PVA materials before and after dye adsorption.

FTIR spectra, like the XRD spectra, of the produced geopolymers were very similar due to the similar synthesis procedure and the same starting materials. Since the starting material, fly ash, mainly consists of oxides of Si, Al, Fe, and Ca [80], the geopolymer material was expected to exhibit bands arising primarily from the formation of bonds between these elements and oxygen. Bands in the wavenumber range of 1010 cm−1 to 1020 cm−1 were characteristic of all synthesized materials and represented the most intense bands in the infrared spectrum. These bands originated from Si–O–Al and Si–O–Si bonds and corresponded to their asymmetric stretching. For the same bonds, bands observed between 700 and 800 cm−1 were characteristic of symmetric stretching, while bending vibrations were found in the range of 400–500 cm−1. In addition to these bands, FTIR spectra also showed bands originating from –OH groups of Si–OH bonds or from water bound during the polymerization process in the geopolymer matrix (N-A-S-H). The –OH stretching vibration corresponded to a broad band in the wavenumber range of 3000 cm−1 to 3600 cm−1, with a maximum around 3390 cm−1. Additionally, bending vibrations of the –OH group appeared at 1637 cm−1. Around the wavenumbers of 1400 cm−1, very low-intensity bands could also be identified, corresponding to the vibrations of CO32− groups [81,82,83,84]. FTIR spectra after dye adsorption on the geopolymers showed similar patterns. The difference between the spectra before and after dye adsorption was reflected in the band around 2360 cm−1. This band was particularly pronounced in materials after adsorption of MB and CV and originated from C=C bonds present in the organic dyes [85]. These spectral changes indicate the presence of dye molecules on the surface of the geopolymer, suggesting that adsorption has taken place.

The influence of the geopolymer modification with chitosan and PVA on the surface charge of the obtained materials was examined by determining the point of zero charge (Figure S2). The point of zero charge (PZC) represents the pH value of a solution at which the surface charge of the material is neutral [42]. The measured PZC values were very close, reflecting the similar preparation procedures used for all materials: 6.07 for GP, 6.20 for GP-Ch, and 6.45 for GP-PVA. At pH values above 6.5, deprotonation of functional groups occurred, resulting in a negatively charged surface. Conversely, at pH values below 6, protonation predominated, and the surface became positively charged. Given that the pH of the dye solutions was 6.5 for methylene blue, 7.9 for crystal violet, and 6.7 for brilliant green, in the dye solutions without pH adjustment, the geopolymers behaved as negatively charged. Since methylene blue, crystal violet, and brilliant green are cationic dyes (Figure S1), we can safely anticipate that they will demonstrate high adsorption efficiency on the synthesized materials.

3.2. Optimization of Adsorption Parameters Using Box–Behnken Design

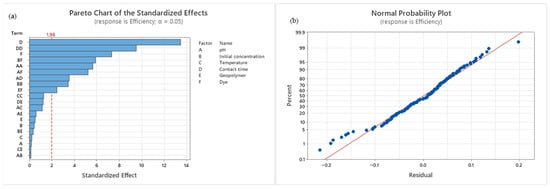

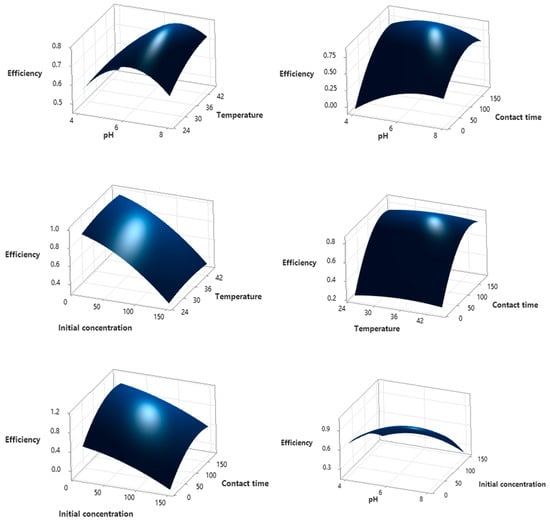

The results obtained using the Box–Behnken design are presented in Figure 4. The analysis of variance (ANOVA) for the investigated model is shown in Table S3.

Figure 4.

(a) Pareto diagram—Effect of adsorption parameters on process efficiency. (b) Normal Probability Plot.

The ANOVA test results indicate that the obtained model was statistically significant, as reflected by the F-value of 37.35 and the p-value of <0.001. The model error was low (0.0055), suggesting that the proposed model can adequately describe the experimental data. The Normal Probability Plot shows that the residuals were normally distributed, further supporting these findings, while also revealing that model errors were most pronounced at very low and very high adsorption efficiency values. Both the Pareto chart and the ANOVA test confirmed that the factors with the greatest influence on the adsorption process were contact time (F = 181.89) and the organic dye used in this process (F = 39.70). In addition, significant effects were observed for the square terms (t2, pH2, C02, T2) and for two-way interactions (pH–t, pH–Dye, C0–Dye, Geopolymer–Dye), while other interactions were not statistically significant. The obtained models in the form of equations are presented in Table S4. Overall, the results clearly demonstrate that contact time exerts the most significant influence on the adsorption process.

The graphical interpretation of the obtained equations is illustrated for sample GP-Ch since this sample showed the highest efficiency in dye adsorption. The graphical interpretation of the equations obtained for the adsorption of methylene blue onto GP-Ch is given in Figure 5, while the graphics for crystal violet and brilliant green are presented in Figures S2 and S3.

Figure 5.

Effect of process parameters on the adsorption efficiency of GP-Ch for MB dye.

3.3. Kinetic Models of the Adsorption Process

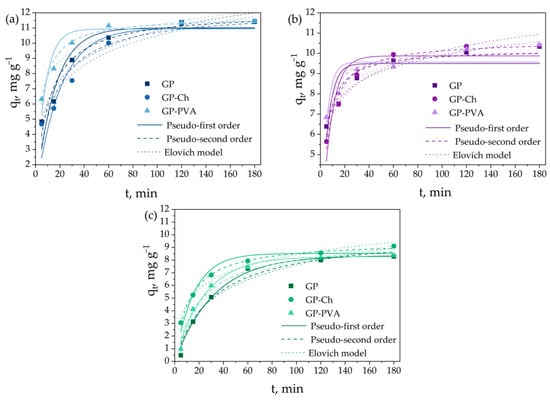

Contact time represents the parameter that most significantly affects the dye adsorption process on geopolymer materials. In addition, the kinetics of the adsorption process is highly important for the design of process systems employing this technology, providing insight into the removal rate of pollutants from water [86]. The dye removal efficiency on geopolymer materials within the first 60 min ranged from 83.9% to 93.0% for methylene blue, from 78.0% to 80.3% for crystal violet, and from 61.1% to 67.3% for brilliant green. The highest adsorption efficiency observed for methylene blue is most likely due to the relatively small size of its molecules, which results in minimal steric hindrance during the adsorption process. The experimentally obtained adsorption data were analyzed by theoretical kinetic models of pseudo-first and pseudo-second orders, the intraparticle diffusion model, and the Elovich kinetic model. The fitting of the experimental data is presented in Figure 6 and Figure 7, while derived kinetic parameters are summarized in Table 1 and Table S5.

Figure 6.

Influence of contact time on adsorption of (a) MB, (b) CV, and (c) BG onto obtained geopolymers, and fitting experimental data with pseudo-first and pseudo-second orders, and Elovich kinetic models.

Figure 7.

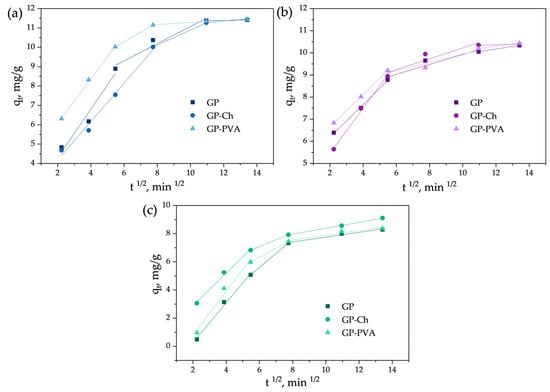

Fitting of experimental data obtained for the adsorption of (a) MB, (b) CV, and (c) BG onto examined materials with the intraparticle diffusion model.

Table 1.

Kinetic parameters of pseudo-first and pseudo-second orders, and Elovich kinetic models for dye adsorption onto geopolymers.

The correlation coefficient values (R2) given in Table 1 indicate that the adsorption of MB and CV on the GP sample followed the Elovich kinetic model, while BG followed the pseudo-second-order kinetic model. Modification of the material with chitosan (GP-Ch) led to a change in the adsorption kinetics of all investigated analytes, which then followed the pseudo-second-order kinetic model. Unlike the chitosan modification, modification with polyvinyl alcohol (GP-PVA) only altered the adsorption kinetics of MB to the pseudo-second-order model, while the adsorption kinetics of CV and BG remained the same as the unmodified GP material. Furthermore, applied modifications increased the adsorption capacities in all investigated cases, with the PVA modification having a more powerful effect. The adsorption capacities obtained experimentally (qexp) did not significantly deviate from the ones theoretically obtained using the pseudo-first and pseudo-second order kinetics. Since in all investigated cases the correlation coefficient value obtained by fitting with the Elovich model was higher than 0.9, the process can be well-described by this model. The coefficient α represents the parameter related to the adsorption process, while β represents the parameter related to the desorption process. As in all cases α > β, this process occurred efficiently.

The investigation of the adsorption mechanism and the identification of the processes that predominantly influence the rate of adsorption were conducted using the intraparticle diffusion model (Figure 7 and Table S5).

Interparticle diffusion plots for dye adsorption onto geopolymeric materials are presented in Figure 7. Obtained multilinear plots did not pass through the origin, suggesting that intraparticle diffusion is not the only rate-controlling step in the adsorption process. From the multilinearity of the intraparticle diffusion plots, it can be concluded that dye adsorption onto the examined geopolymeric materials occurs through three consecutive steps. In well-agitated systems, during the initial stage of adsorption when the dye concentration gradient is at its highest, the diffusion of dye molecules to the external boundary layer of the adsorbent occurs rapidly. This initial diffusion step is the fastest phase of the adsorption process, as evidenced by the high values of the corresponding rate constants (Table S5). Consequently, this step does not constitute the rate-limiting stage and therefore has negligible influence on the overall adsorption rate.

The second stage is characterized as a moderate adsorption step. Here, the diffusion of dye molecules within the porous geopolymer matrix affects the adsorption kinetics, and intraparticle diffusion emerges as the rate-limiting factor.

The third, equilibrium stage, is characterized by the lowest adsorption rate, evident from the values of rate constants (Table S5). At this stage, equilibrium or material saturation is reached, along with a decrease in dye concentration in the solution, which further slows down the process. Therefore, the process is rapid at the beginning, but its rate gradually decreases over time.

3.4. Isotherm Models of the Adsorption Process

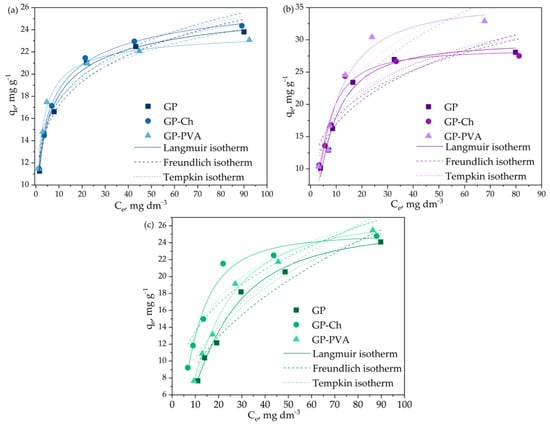

Figure 8 shows the influence of the initial concentration on the adsorption capacities of the examined geopolymers. The adsorption capacity was observed to increase with the initial dye concentration, while the efficiency of the adsorption process decreased (Figure S5). In the examined initial concentration range, the characteristic plot was not reached, indicating the lack of surface saturation, however, the obtained equilibrium adsorption capacities ranged from 23.81 mg g−1 to 28.08 mg g−1 for GP, from 24.36 mg g−1 to 27.52 mg g−1 for GP-Ch, and from 23.08 mg g−1 to 32.90 mg g−1 for GP-PVA. For a better understanding of the interaction between adsorbate and adsorbent, the experimentally obtained equilibrium adsorption data were analyzed using selected adsorption isotherm models. Experimental data fitting with the Langmuir, Freundlich, and Temkin adsorption isotherms are shown in Figure 8, while Table 2 summarizes the isotherm parameters.

Figure 8.

The influence of initial concentration of (a) MB, (b) CV, and (c) BG solution on the geopolymer adsorption capacities, and fitting of experimental data with the Langmuir, Freundlich, and Temkin adsorption isotherms.

Table 2.

Isotherm parameters of the Langmuir, Freundlich, and Temkin models for dye adsorption onto geopolymers.

The highest values of correlation coefficients (R2) were obtained by comparing the experimental data with the Langmuir adsorption isotherm, indicating that this model best described the adsorption of selected dyes onto geopolymers. Nevertheless, generally high values of correlation coefficients indicate that all three models can be successful in describing the examined adsorption processes. It was observed that the addition of chitosan and PVA to the initial raw mixture led to a slight increase in maximum adsorption capacity calculated by the Langmuir model. The constant b, which reflects the affinity between adsorbate and adsorbent, was the highest for the adsorption of methylene blue. The value of Freundlich heterogeneity factor 1/n was lower than one in all cases, which indicates a homogeneous distribution of active adsorption sites, which is in accordance with the highest correlation coefficients obtained for the Langmuir isotherm model. The value of Kf, which reflects the adsorption capacity per unit mass, decreased in the order MB > CV > BG for all examined geopolymers, and generally increased for modified geopolymers. The Tempkin constant A, which indicates the strength of interaction between molecules and the adsorbent, was highest during the adsorption of methylene blue. As in previous cases, the addition of polymeric materials to the raw mixture increased the affinity toward the adsorbate, as reflected by the higher A coefficient. The values of B, ranging from 2.620 to 8.308 J mol−1, indicate that the examined dyes are adsorbed on the surface of geopolymers through the mechanism of physisorption [87].

The Dubinin–Radushkevich (D–R) model was applied to estimate the mean adsorption energy and determine the mechanism of adsorption. The comparison of the experimentally obtained data with the Dubinin–Radushkevich model was performed through linear fitting, as shown in Figure S6, and the obtained parameters are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Isotherm parameters of the Dubinin–Radushkevich model for dye adsorption onto geopolymers.

The correlation coefficient between the experimental data and the Dubinin–Radushkevich model was lower compared to the other isotherm models. The best agreement with this model was observed for the adsorption of brilliant green (Table 3), while methylene blue and crystal violet showed weaker correlation values. The data for the maximum amount of adsorbed analyte (qm), obtained using the Dubinin–Radushkevich model, were significantly lower and closer to the experimentally obtained values compared to those obtained by the Langmuir model (q0). The mean adsorption energy decreased in the order MB > CV > BG, and its values were higher for geopolymers additionally modified with chitosan and PVA. Furthermore, the mean adsorption energy was below 2 kJ mol−1, indicating that the process is physical adsorption [88,89], i.e., adsorption due to physical interactions between the material and the analyte. The Dubinin–Radushkevich model confirms that the dominant adsorption mechanism is physisorption, which is consistent with the Temkin model results.

3.5. Thermodynamics of the Adsorption Process

By increasing the temperature, either the adsorption process or the desorption process may be favoured. The effect of temperature on adsorption capacity was investigated at 30 °C, 35 °C, and 45 °C. The results are graphically presented in Figure S7, while the values of thermodynamic parameters—standard Gibbs free energy change (ΔG°), enthalpy change (ΔH°), and entropy change (ΔS°)—are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Thermodynamic parameters (ΔG°, ΔH°, ΔS°) of dye adsorption onto geopolymers.

The standard Gibbs free energy change (ΔG°) had a negative value at all investigated temperatures, indicating that the adsorption process occurs spontaneously within the examined temperature range. It was also observed that in most cases, ΔG° showed a higher absolute value with the increase in temperature, suggesting that the process becomes more spontaneous at higher temperatures. Adsorption on the GP-Ch material was accompanied by a large positive entropy change (ΔS° = 105.3−167.3 J mol−1 K−1), which may suggest that this process is entropy-driven, with an increase in disorder at the adsorbent–adsorbate interface. The ΔS° values for the other investigated materials were lower. In cases they were lower than 55 J mol−1 K−1, the process cannot be considered entropy-driven. The enthalpy change of the adsorption processes was positive in most cases. The GP-Ch material exhibited higher ΔH° values in comparison with the other materials.

The thermodynamic parameters ΔG° and ΔH° provide valuable insights into the nature of the adsorption process, distinguishing between physical and chemical adsorption mechanisms. It is generally accepted that physical adsorption is characterized by enthalpy changes (ΔH°) in the range of 2–21 kJ mol−1 while Gibbs free energy changes (ΔG°) are between 0 and −20 kJ mol−1. In contrast, chemical adsorption typically exhibits ΔH° values between 80–200 kJ mol−1 and ΔG° values ranging from −80 to −400 kJ mol−1 [90].

In this study, the calculated ΔG° values were, in absolute terms, below 20 kJ/mol, indicating that the adsorption of dyes likely proceeds via a physisorption mechanism [91]. Similarly, the observed ΔH° values, all below 46 kJ mol−1, are more consistent with physisorption than with chemisorption. These findings suggest that no covalent bonds were formed between the dye molecules and the geopolymer surface. Instead, the adsorption likely occurs through electrostatic interactions between the negatively charged geopolymer surface and the cationic dye molecules (Figure 9). The obtained results are also in agreement with the assumption derived from the Temkin and Dubinin–Radushkevich models.

Figure 9.

Graphical representation of the adsorption mechanism and the structures of the obtained composites.

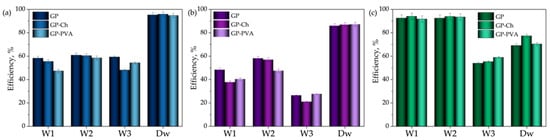

3.6. Application of Geopolymeric Adsorbents for Dye Adsorption from Real Wastewater Samples

The impact of the complex matrix present in wastewater samples on the adsorption performance of geopolymers was evaluated by comparing their efficiency in removing methylene blue, crystal violet, and brilliant green from real wastewater and from spiked distilled water (Figure 10). In the case of methylene blue and crystal violet, the presence of the wastewater matrix had a negative effect, reducing the adsorption efficiency of the geopolymers. On the other hand, the adsorption of brilliant green from samples W1 and W2 was positively affected by the complex matrix, with efficiencies exceeding 90%.

Figure 10.

The adsorption efficiency of geopolymer samples for the removal of (a) MB, (b) CV, and (c) BG from wastewater and spiked distilled water.

3.7. Comparison of Adsorption Process with Other Studies

To examine the relevance of the presented study, a comparison was made with materials reported in recently published studies that investigated dye adsorption on biowaste, industrial waste, as well as metallic and hybrid materials (Table 5). Comparison of the adsorption capacities of geopolymers synthesized in this work with those found in the literature for a similar initial dye concentration range showed that the obtained geopolymers had higher or comparable capacities for the adsorption of selected dyes.

Table 5.

Comparison of the obtained results with other relevant studies.

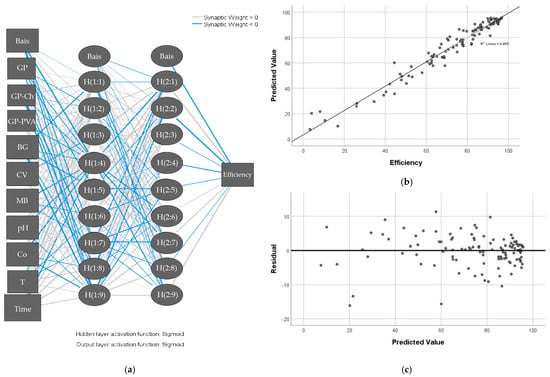

3.8. Prediction of the Dye Adsorption Efficiency on Geopolymers Using Artificial Neural Network

Artificial neural networks represent a complex computational model, which, unlike all others, assumes a nonlinear correlation between parameters. Similar to the human brain, it has the ability to learn. The type of network used for data processing is feed-forward, while the type of learning used is backpropagation [42]. The dye concentrations after adsorption, under different conditions, were in the input layer, whereas the materials that were used as adsorbents, as well as the parameters of adsorption (pH, Co, T and t), were in the output layer (Figure 11a). The artificial neural network automatically selected two units in the hidden layer with 9 units in both hidden layers after several iterations (training and testing). The Sigmoid activation function was used in the input and output layers, as required when designing the network. The network will strive to keep the sum of squared error as small as possible. With several iterations, the network reported that the sum of squared errors was 0.081 for testing and 0.058 for training. The dye concentrations after adsorption, the materials that were used as adsorbents, as well as the parameters of adsorption (pH, Co, T and t), were in the input layer, whereas adsorption efficiency was in the output layer as a dependent variable (Figure 11a).

Figure 11.

Architecture of artificial neural network (ANN). (a) Scatter plot of predicted from measured value for the selected efficiency variable. (b) Scatter plot of residuals from predicted value for adsorption efficiency (c) using an artificial neural network.

Figure 11b shows a scatterplot of the predicted values on the y-axis from the observed values on the x-axis for combined training and testing. Ideally, the values should lie approximately along the 45° line. The points in this graph represent the observed variable adsorption efficiency and followed the observed line well. The value of R2 was 0.955, which is an extremely good result [101].

The graph of residuals from the predicted value is shown in Figure 11c and represents the scattering of the residuals (the difference between the observed value and the predicted value) on the y axis by the predicted values on the x axis. The well-spaced points on either side of the horizontal zero ordinate line represent the average of the residuals, suggesting that the model fits the data well.

Figure 11 shows the results of modelling using an artificial neural network, which refers to testing the adsorption of the three selected dyes on synthesized geopolymers, in order to determine which one had the highest adsorption capacity, i.e., the highest removal efficiency from aqueous solutions.

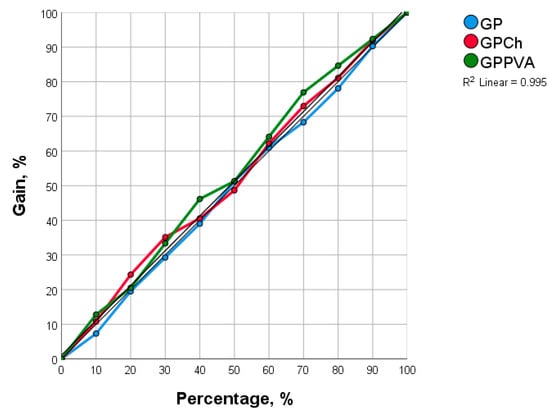

Considering all adsorption parameters, the network showed that the highest adsorption capacity was achieved for MB, then CV, and finally BG. Geopolymers synthesized on the basis of fly ash showed similar performance, but modification with chitosan was found to be the best option (R2 was 0.995)—Figure 12. This prediction could help in further research considering the application of new modified materials as adsorbents and also in testing their performance in removing residues of other dyes from water.

Figure 12.

Effect of the type of geopolymers as adsorbents on the adsorption efficiency of selected dyes obtained using artificial neural networks (ANNs).

Figure 13 shows that the highest level of significance in terms of the adsorption efficiency of dyes onto the geopolymers was shown by contact time, pH value, dye type, and initial concentration, respectively (over 60%). The type of geopolymer and temperature showed a lower level of significance.

Figure 13.

The significance level of the influence of various parameters on the adsorption efficiency of selected dyes on modified geopolymers as adsorbents obtained using ANN.

4. Conclusions

In this study, the valorization of fly ash as waste was conducted, and the obtained materials were characterized and applied for the adsorption of dyes: methylene blue, crystal violet, and brilliant green. This study addressed two significant environmental issues: (1) the accumulation of industrial waste and (2) environmental pollution caused by dye effluents. Among the synthesized materials, GP-Ch demonstrated the best adsorption performance, with adsorption efficiencies of 95.9% for MB, 87.3% for CV, and 77.3% for BG, which is comparable to other relevant studies. The optimization of process parameters was performed using the Box–Behnken design and chemometric multivariate analysis methods, revealing that contact time and the type of dye being adsorbed play a crucial role in the adsorption process. The negatively charged surface of the material (pHPZC) in the examined pH range additionally contributed to the increased adsorption capacity. Adsorption of methylene blue, crystal violet, and brilliant green onto all examined geopolymers showed the best correlation with the Langmuir adsorption isotherm. Values of the Langmuir maximum adsorption capacities that ranged from 27.35 to 36.07 mg g−1 indicated that modification with organic polymers improved the adsorption properties of geopolymers. The Elovich kinetic model and the Dubinin–Radushkevich isotherm model (0.245 kJ mol−1 < E < 1.380 kJ mol−1) suggested that the adsorption mechanism is predominantly physical, which was confirmed by thermodynamic analysis. The application of ANN confirmed the results of the adsorption experiments; the contact time, pH, initial dye concentration, and the type of the dye (significance level > 60%) were the parameters that had the greatest influence on the adsorption efficiency, while the type of material modification was less significant. All the obtained results indicate that materials synthetized in this study can be effectively used in dye adsorption processes, contributing to both waste reduction and environmental remediation.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/separations12110299/s1, Figure S1. Chemical structures of organic dyes: (a) MB, (b) CV and (c) BG, Table S1. Physicochemical properties of selected dyes, Table S2. The sampling sites of raw wastewater, and pH of wastewater samples, Figure S2. pHPZC values of GP, GP-Ch, and GP-PVA materials, Table S3. Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) of the Box–Behnken design model, Table S4. Model equations obtained using the Box–Behnken design, Figure S3. Effect of process parameters on the adsorption efficiency of GP-Ch for CV dye, Figure S4. Effect of process parameters on the adsorption efficiency of GP-Ch for BG dye, Table S5. Intraparticle diffusion parameters and correlation coefficients for dye adsorption onto geopolymers, Figure S5. Influence of initial dye concentration on the adsorption efficiency, Figure S6. The influence of initial concentration of (a) MB, (b) CV, and (c) BG solution on geopolymers’ adsorption capacities, and fitting of experimental data with Dubinin–Radushkevich isotherm model, Figure S7. Impact of Temperature on Dye Adsorption onto Geopolymer.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.V.T., M.M.M., M.M.V. and D.Z.Ž.; methodology, M.M.V., A.A.P.G. and D.Z.Ž.; software, D.V.T. and D.Z.Ž.; validation, M.M.M. and M.M.V.; formal analysis, D.V.T., D.Z.Ž. and Đ.N.V.; investigation, D.V.T., M.M.M. and Đ.N.V.; resources, D.Z.Ž.; writing—original draft preparation, D.V.T.; writing—review and editing, M.M.M., M.M.V., Đ.N.V., A.A.P.G. and D.Z.Ž.; visualization, D.V.T. and M.M.M.; supervision, D.Z.Ž.; project administration: A.A.P.G. and D.Z.Ž. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the Ministry of Science, Technological Development and Innovation of the Republic of Serbia (No. 451-03-136/2025-03/200135 and No. 451-03-136/2025-03/200287).

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article or Supplementary Materials.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the support given by Aleksandar Marinković in conducting the FTIR analysis.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Hmoudah, M.; Paparo, R.; De Luca, M.; Fortunato, M.E.; Tesser, R.; Di Serio, M.; Ferone, C.; Roviello, G.; Tarallo, O.; Russo, V. Adsorption of Methylene Blue on Metakaolin-Based Geopolymers: A Kinetic and Thermodynamic Investigation. ChemEngineering 2025, 9, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chafi, S.; Cuevas-Aranda, M.; Martínez-Cartas, M.L.; Sánchez, S. Production of Bioadsorbents via Low-Temperature Pyrolysis of Exhausted Olive Pomace for the Removal of Methylene Blue from Aqueous Media. Molecules 2025, 30, 3254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azlan Zahari, K.F.; Sahu, U.K.; Khadiran, T.; Surip, S.N.; Alothman, Z.A.; Jawad, A.H. Mesoporous Activated Carbon from Bamboo Waste via Microwave-Assisted K2CO3 Activation: Adsorption Optimization and Mechanism for Methylene Blue Dye. Separations 2022, 9, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milojković, N.; Simović, B.; Žunić, M.; Radovanović, L.; Prekajski-Đorđević, M.; Dapčević, A. Modified Z-scheme Heterojunction of TiO2 /Polypyrrole Recyclable Photocatalyst. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2025, 108, e20431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bounaas, M.; Bouguettoucha, A.; Chebli, D.; Derbal, K.; Benalia, A.; Pizzi, A. Effect of Washing Temperature on Adsorption of Cationic Dyes by Raw Lignocellulosic Biomass. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 10365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boumezough, Y.; Viscusi, G.; Arris, S.; Gorrasi, G.; Carabineiro, S.A.C. Synthesis and Characterization of a Nanocomposite Based on Opuntia Ficus Indica for Efficient Removal of Methylene Blue Dye: Adsorption Kinetics and Optimization by Response Surface Methodology. IJMS 2025, 26, 6717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gul, S.; Gul, A.; Gul, H.; Khattak, R.; Ismail, M.; Khan, S.U.; Khan, M.S.; Aouissi, H.A.; Krauklis, A. Removal of Brilliant Green Dye from Water Using Ficus Benghalensis Tree Leaves as an Efficient Biosorbent. Materials 2023, 16, 521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Šekuljica, N.Ž.; Prlainović, N.Ž.; Stefanović, A.B.; Žuža, M.G.; Čičkarić, D.Z.; Mijin, D.Ž.; Knežević-Jugović, Z.D. Decolorization of Anthraquinonic Dyes from Textile Effluent Using Horseradish Peroxidase: Optimization and Kinetic Study. Sci. World J. 2015, 2015, 371625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ong, M.D.; Vasquez, I.; Alvarez, B.; Cho, D.R.; Williams, M.B.; Vincent, D.; Ali, M.A.; Aich, N.; Pinto, A.H.; Choudhury, M.R. Modification of Cellulose Acetate Microfiltration Membranes Using Graphene Oxide–Polyethyleneimine for Enhanced Dye Rejection. Membranes 2023, 13, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzminova, A.; Dmitrenko, M.; Salomatin, K.; Vezo, O.; Kirichenko, S.; Egorov, S.; Bezrukova, M.; Karyakina, A.; Eremin, A.; Popova, E.; et al. Holmium-Containing Metal-Organic Frameworks as Modifiers for PEBA-Based Membranes. Polymers 2023, 15, 3834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.-S.; Liu, C.-H.; Chu, K.H.; Suen, S.-Y. Removal of Cationic Dye Methyl Violet 2B from Water by Cation Exchange Membranes. J. Membr. Sci. 2008, 309, 239–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Moselhy, M.M.; Kamal, S.M. Selective Removal and Preconcentration of Methylene Blue from Polluted Water Using Cation Exchange Polymeric Material. Groundw. Sustain. Dev. 2018, 6, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Lin, Y.; Luo, Y.; Yu, P.; Hou, L. Relating Organic Fouling of Reverse Osmosis Membranes to Adsorption during the Reclamation of Secondary Effluents Containing Methylene Blue and Rhodamine B. J. Hazard. Mater. 2011, 192, 490–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antanasković, A.; Lopičić, Z.; Dimitrijević-Branković, S.; Ilić, N.; Adamović, V.; Šoštarić, T.; Milivojević, M. Biochar as an Enzyme Immobilization Support and Its Application for Dye Degradation. Processes 2024, 12, 2418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, L.A.; Malik, T.; Siddiq, M.; Haleem, A.; Sayed, M.; Naeem, A. TiO2 Nanotubes Doped Poly(Vinylidene Fluoride) Polymer Membranes (PVDF/TNT) for Efficient Photocatalytic Degradation of Brilliant Green Dye. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 103291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, N.T.; Manh, T.D.; Nguyen, V.T.; Thy Nga, N.T.; Mwazighe, F.M.; Nhi, B.D.; Hoang, H.Y.; Chang, S.W.; Chung, W.J.; Nguyen, D.D. Kinetic Study on Methylene Blue Removal from Aqueous Solution Using UV/Chlorine Process and Its Combination with Other Advanced Oxidation Processes. Chemosphere 2022, 308, 136457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhatnagar, A.; Hogland, W.; Marques, M.; Sillanpää, M. An Overview of the Modification Methods of Activated Carbon for Its Water Treatment Applications. Chem. Eng. J. 2013, 219, 499–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebre Meskel, A.; Kwikima, M.M.; Meshesha, B.T.; Habtu, N.G.; Naik, S.V.C.S.; Vellanki, B.P. Malachite Green and Methylene Blue Dye Removal Using Modified Bagasse Fly Ash: Adsorption Optimization Studies. Environ. Chall. 2024, 14, 100829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radoor, S.; Karayil, J.; Devrim, Y.; Kim, H. Polyethyleneimine Functionalized Waste Tissue Paper@waste PET Composite for the Effective Adsorption and Filtration of Organic Dyes from Wastewater. Sustain. Mater. Technol. 2025, 45, e01494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Eswed, B.I.; Yousef, R.I.; Alshaaer, M.; Hamadneh, I.; Al-Gharabli, S.I.; Khalili, F. Stabilization/Solidification of Heavy Metals in Kaolin/Zeolite Based Geopolymers. Int. J. Miner. Process. 2015, 137, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, M.; Koksal, F.; Gencel, O.; Munir, M.J.; Kazmi, S.M.S. Influence of Micro Fe2O3 and MgO on the Physical and Mechanical Properties of the Zeolite and Kaolin Based Geopolymer Mortar. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 52, 104443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ettahiri, Y.; Bouna, L.; Brahim, A.; Benlhachemi, A.; Bakiz, B.; Sánchez-Soto, P.J.; Eliche-Quesada, D.; Pérez-Villarejo, L. Synthesis and Characterization of Porous and Photocatalytic Geopolymers Based on Natural Clay: Enhanced Properties and Efficient Rhodamine B Decomposition. Appl. Mater. Today 2024, 36, 102048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, W.L.; Fan, L.F.; Zhang, B. Experimental Research on the Flexural Properties and Pore Structure Characteristics of Engineered Geopolymer Composites Prepared by Calcined Natural Clay. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 98, 111244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Iqtidar, A.; Amin, M.N.; Nazar, S.; Hassan, A.M.; Ali, M. Predictive Modelling of Compressive Strength of Fly Ash and Ground Granulated Blast Furnace Slag Based Geopolymer Concrete Using Machine Learning Techniques. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2024, 20, e03130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faraji, M.F.; Ahıskalı, A.; Bayraktar, O.Y.; Ahıskalı, M.; Kaplan, G.; Aydın, A.C.; Ozbakkaloglu, T. A Green Approach to Construction: Fly Ash-Based One-Part Geopolymer Foam Concrete Reinforced with Waste Concrete Powder and Polypropylene Fibers. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 494, 143429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mladenović, N.; Kljajević, L.; Nenadović, S.; Ivanović, M.; Čalija, B.; Gulicovski, J.; Trivunac, K. The Applications of New Inorganic Polymer for Adsorption Cadmium from Waste Water. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym. 2020, 30, 554–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhang, Z.; Mao, J.; Lin, J.; Xiao, F.; Chen, S.; Liu, Y.; Qian, H.; Yan, D. Modeling the Thermal Conductivity of the Ground Granulated Blast Furnace Slag-Based Foam Geopolymer Based on Its Multi-Scale Pore Structure. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 105, 112487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J. Thermally Activated Red Mud-Based Geopolymer Concrete: Synergistic Design for High Strength and Multidimensional Sustainability. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 2025, 48, 102236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Liu, T.; Zhang, Y.; Wan, Q.; Zhang, R. Efficient and Green Utilization of Bayer Red Mud in Solid Waste Based Geopolymer. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 119717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buha Marković, J.Z.; Marinković, A.D.; Savić, J.Z.; Mladenović, M.R.; Erić, M.D.; Marković, Z.J.; Ristić, M.Đ. Risk Evaluation of Pollutants Emission from Coal and Coal Waste Combustion Plants and Environmental Impact of Fly Ash Landfilling. Toxics 2023, 11, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Djukic, D.; Suljagic, M.; Andjelkovic, L.; Pavlovic, V.; Bucevac, D.; Vrbica, B.; Mirkovic, M. Effect of Sintering Temperature and Calcium Amount on Compressive Strength of Brushite-Metakaolin Polymer Materials. Sci. Sinter. 2022, 54, 287–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Štulović, M.; Radovanović, D.; Dikić, J.; Gajić, N.; Djokić, J.; Kamberović, Ž.; Jevtić, S. Utilization of Copper Flotation Tailings in Geopolymer Materials Based on Zeolite and Fly Ash. Materials 2024, 17, 6115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genua, F.; Lancellotti, I.; Leonelli, C. Geopolymer-Based Stabilization of Heavy Metals, the Role of Chemical Agents in Encapsulation and Adsorption: Review. Polymers 2025, 17, 670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mladenović Nikolić, N.; Kandić, A.; Potočnik, J.; Latas, N.; Ivanović, M.; Nenadović, S.; Kljajević, L. Microstructural Analysis and Radiological Characterization of Alkali-Activated Materials Based on Aluminosilicate Waste and Metakaolin. Gels 2025, 11, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Obeidy, N.F.; Khalil, W.I.; Ahmed, H.K. Optimization of Local Modified Metakaolin-Based Geopolymer Concrete by Taguchi Method. Open Eng. 2024, 14, 20220561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzukashvili, S.; Sommerville, R.; Kökkılıç, O.; Ouzilleau, P.; Rowson, N.A.; Waters, K.E. Exploring Efficiency and Regeneration of Magnetic Zeolite Synthesized from Coal Fly Ash for Water Treatment Applications. JCIS Open 2025, 17, 100127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, S.; Zhang, G.; Wang, X.; Zang, S.; Jia, Y. Removal of As(V) and As(III) Species from Wastewater by Adsorption on Coal Fly Ash. Desalination Water Treat. 2019, 151, 242–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, Z.; Zhou, Q.; Chen, J. Enhanced Adsorption of Pb(II), Cd(II), and Zn(II) by Tannic Acid-Modified Magnetic Fly Ash-Based Tobermorite. Environ. Res. 2025, 283, 122206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joseph, I.V.; Tosheva, L.; Doyle, A.M. Simultaneous Removal of Cd(II), Co(II), Cu(II), Pb(II), and Zn(II) Ions from Aqueous Solutions via Adsorption on FAU-Type Zeolites Prepared from Coal Fly Ash. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 103895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Wang, Q.; Gao, J.; Guo, Y.; Cheng, F. The Selective Adsorption of Rare Earth Elements by Modified Coal Fly Ash Based SBA-15. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 2022, 47, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radojičić, T.; Trivunac, K.; Vukčević, M.; Maletić, M.; Palić, N.; Janković-Častvan, I.; Perić Grujić, A. Rare Earth Element Adsorption from Water Using Alkali-Activated Waste Fly Ash. Materials 2025, 18, 699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vukčević, M.; Trajković, D.; Maletić, M.; Mirković, M.; Perić Grujić, A.; Živojinović, D. Modified Fly Ash as an Adsorbent for the Removal of Pharmaceutical Residues from Water. Separations 2024, 11, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, Z.; Chang, N.; Sun, J.; Xiang, S.; Ayaz, T.; Zhang, H.; Wang, H. Modification of Coal Fly Ash and Its Use as Low-Cost Adsorbent for the Removal of Directive, Acid and Reactive Dyes. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 422, 126778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Ma, H.; Li, Y.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Y.; Li, Z. Efficient Adsorption and Performance Optimization of Coal Fly Ash/Desulphurized Manganese Residue Composite Microspheres on Dyes. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 357, 130174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, R.; Hapiz, A.; Musa, S.A.; ALOthman, Z.A.; Sillanpää, M.; Jawad, A.H. Hydrothermal Fabrication of Composite Chitosan Grafted Salicylaldehyde/Coal Fly Ash/Algae for Malachite Green Dye Removal: A Statistical Optimization. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 280, 135897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodwihok, C.; Suwannakaew, M.; Han, S.W.; Lim, Y.J.; Park, S.Y.; Woo, S.W.; Choe, J.W.; Wongratanaphisan, D.; Kim, H.S. Effective Removal of Hazardous Organic Contaminant Using Integrated Photocatalytic Adsorbents: Ternary Zinc Oxide/Zeolite-Coal Fly Ash/Reduced Graphene Oxide Nanocomposites. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2023, 662, 131044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malek, N.N.A.; Jawad, A.H.; Ismail, K.; Razuan, R.; ALOthman, Z.A. Fly Ash Modified Magnetic Chitosan-Polyvinyl Alcohol Blend for Reactive Orange 16 Dye Removal: Adsorption Parametric Optimization. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 189, 464–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrunik, M.; Skalny, M.; Bajda, T. Functionalized Adsorbents Resulting from the Transformation of Fly Ash: Characterization, Modification, and Adsorption of Pesticides. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2023, 309, 123106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Chen, Y.-L.; Zhang, X.-H.; Tian, F.-M.; Zu, Z.-N. Zeolites Developed from Mixed Alkali Modified Coal Fly Ash for Adsorption of Volatile Organic Compounds. Mater. Lett. 2014, 119, 140–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, T.; Zhang, X.; Han, Y.; Liu, T.; Wang, B.; Zhang, Z. Preparation of Zeolite X by the Aluminum Residue from Coal Fly Ash for the Adsorption of Volatile Organic Compounds. Front. Chem. 2019, 7, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, J.; Jiang, J.; Gao, X.; Ding, M. Improving the Mechanical Properties of Fly Ash-Based Geopolymer Composites with PVA Fiber and Powder. Materials 2022, 15, 2363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, S.; Malik, M.A.; Qi, Z.; Huang, B.; Li, Q.; Sarkar, M. Influence of the PVA Fibers and SiO2 NPs on the Structural Properties of Fly Ash Based Sustainable Geopolymer. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 164, 238–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Chen, R.; Zhang, L. Utilization of Chitosan Biopolymer to Enhance Fly Ash-Based Geopolymer. J. Mater. Sci. 2013, 48, 7986–7993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Yuan, N.; Tan, Z.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, L.; Tang, W.; Chen, C.; Lin, D. Transparent Elastic Wound Dressing Gel Supporting Drug Release: Synergistic Effects of Poly(Vinyl Alcohol)/Chitosan Hybrid Matrix. Gels 2025, 11, 771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jang, T.; Yoon, S.; Choi, J.-H.; Kim, N.; Park, J.-A. Simultaneous Removal of Heavy Metals and Dyes on Sodium Alginate/Polyvinyl Alcohol/κ-Carrageenan Aerogel Beads. Gels 2025, 11, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazar, M.M.; Ghiorghita, C.-A.; Rusu, D.; Dinu, M.V. Nanocomposite Cryogels Based on Chitosan for Efficient Removal of a Triphenylmethane Dye from Aqueous Systems. Gels 2025, 11, 729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalvand, A.; Nabizadeh, R.; Reza Ganjali, M.; Khoobi, M.; Nazmara, S.; Hossein Mahvi, A. Modeling of Reactive Blue 19 Azo Dye Removal from Colored Textile Wastewater Using L-Arginine-Functionalized Fe3O4 Nanoparticles: Optimization, Reusability, Kinetic and Equilibrium Studies. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2016, 404, 179–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagergren, S. Zur Theorie Der Sogenannten Adsorption Gelöster Stoffe. K. Sven. Vetenskapsakademiens Handl. 1898, 24, 1–39. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, Y.S.; McKay, G. Pseudo-Second Order Model for Sorption Processes. Process Biochem. 1999, 34, 451–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, W.J.; Morris, J.C. Removal of Biological Resistant Pollutions from Wastewater by Adsorption. In Advances in Water Pollution Research: Proceedings of the International Conference on Water Pollution Symposium; Pergamon Press: Oxford, UK, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Aharoni, C.; Tompkins, F.C. Kinetics of Adsorption and Desorption and the Elovich Equation. In Advances in Catalysis; Eley, D.D., Pines, H., Weisz, P.B., Eds.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1970; Volume 21, pp. 1–49. ISBN 978-0-12-007821-9. [Google Scholar]

- Langmuir, I. The Adsorption of Gases on Plane Surfaces of Glass, Mica and Platinum. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1918, 40, 1361–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freundlich, H. Adsorption in Solutions. J. Phys. Chem. 1906, 57, 384–410. [Google Scholar]

- Temkin, M.I. Kinetics of Ammonia Synthesis on Promoted Iron Catalysts. Acta Physiochimica URSS 1940, 12, 327–356. [Google Scholar]

- Dubinin, M.M.; Radushkevich, L.W. Equation of the Characteristic Curve of Activated Charcoal. Proc. Acad. Sci. USSR Phys. Chem. Sect. 1947, 55, 331–333. [Google Scholar]

- Grahovac, N.; Aleksić, M.; Pezo, L.; Đurović, A.; Stojanović, Z.; Jocković, J.; Cvejić, S. Box–Behnken-Assisted Optimization of High-Performance Liquid Chromatography Method for Enhanced Sugar Determination in Wild Sunflower Nectar. Separations 2025, 12, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsitsirigka, T.; Kalompatsios, D.; Athanasiadis, V.; Bozinou, E.; Sfougaris, A.I.; Lalas, S.I. Valorization of the Bioactive Potential of Juniperus communis L. Berry Extracts Using a Box–Behnken Design and Characterization of Kernel Oil Compounds. Separations 2025, 12, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mecheri, R.; Zobeidi, A.; Atia, S.; Neghmouche Nacer, S.; Salih, A.A.M.; Benaissa, M.; Ghernaout, D.; Arni, S.A.; Ghareba, S.; Elboughdiri, N. Modeling and Optimizing the Crystal Violet Dye Adsorption on Kaolinite Mixed with Cellulose Waste Red Bean Peels: Insights into the Kinetic, Isothermal, Thermodynamic, and Mechanistic Study. Materials 2023, 16, 4082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leardi, R. Nature-Inspired Methods in Chemometrics: Genetic Algorithms and Artificial Neural Networks; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2003; ISBN 978-0-08-052262-3. [Google Scholar]

- Lek, S.; Delacoste, M.; Baran, P.; Dimopoulos, I.; Lauga, J.; Aulagnier, S. Application of Neural Networks to Modelling Nonlinear Relationships in Ecology. Ecol. Model. 1996, 90, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basheer, I.A.; Hajmeer, M. Artificial Neural Networks: Fundamentals, Computing, Design, and Application. J. Microbiol. Methods 2000, 43, 3–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.H.; Law, D.; Patrisia, Y.; Gunasekara, C. Blended Brown Coal and Class F Fly Ash Based Geopolymer. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2025, 23, e05036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, H. Alkali Cation Effects on Compressive Strength of Metakaolin–Low-Calcium Fly Ash-Based Geopolymers. Materials 2025, 18, 4080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Li, K.; Shi, H.; Chen, C.; Yuan, C. Study on the Effects and Mechanisms of Fly Ash, Silica Fume, and Metakaolin on the Properties of Slag–Yellow River Sediment-Based Geopolymers. Materials 2025, 18, 1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.-L.; Wu, K.; Qian, L.-P.; Wang, Y.-S.; Guo, D. Effect of Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) Modification on Strength and Microstructure of Geopolymer Paste. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 489, 142378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mladenović Nikolić, N.; Kljajević, L.; Nenadović, S.S.; Potočnik, J.; Knežević, S.; Dolenec, S.; Trivunac, K. Adsorption Efficiency of Cadmium (II) by Different Alkali-Activated Materials. Gels 2024, 10, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kmiotek, A.; Figiela, B.; Łach, M.; Aruova, L.; Korniejenko, K. An Investigation of Key Mechanical and Physical Characteristics of Geopolymer Composites for Sustainable Road Infrastructure Applications. Buildings 2025, 15, 1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nath, S.K.; Maitra, S.; Mukherjee, S.; Kumar, S. Microstructural and Morphological Evolution of Fly Ash Based Geopolymers. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 111, 758–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Riessen, A.; Jamieson, E.; Gildenhuys, H.; Skane, R.; Allery, J. Using XRD to Assess the Strength of Fly-Ash- and Metakaolin-Based Geopolymers. Materials 2025, 18, 2093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankovic, A.; Cujic, M.; Stojkovic, M.; Djolic, M.; Zivojinovic, D.; Onjia, A.; Ristic, M.; Peric-Grujic, A. Impact of Leaching Procedure on Heavy Metals Removal from Coal Fly Ash. Hem. Ind. 2024, 78, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yavuz, E.; Kul Gul, N.I.; Kockal, N.U. Characterization of Class C and F Fly Ashes Based Geopolymers Incorporating Silica Fume. Ceram. Int. 2022, 48, 32213–32225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Ma, Z.; Gao, J.; Guo, Y.; Cheng, F. Synthesis and Characterization of Geopolymer Prepared from Circulating Fluidized Bed-Derived Fly Ash. Ceram. Int. 2022, 48, 11820–11829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Fan, X.; Gao, C. Strength, Pore Characteristics, and Characterization of Fly Ash-Slag-Based Geopolymer Mortar Modified with Silica Fume. Structures 2024, 69, 107525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, J.; Lv, Y.; Peng, H.; Han, W.; Pan, B.; Zhang, B. Performance and Characterization of Fly Ash-Metakaolin-Based Geopolymer Pastes. Mater. Today Commun. 2024, 41, 110293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhavyasree, P.G.; Xavier, T.S. Adsorption Studies of Methylene Blue, Coomassie Brilliant Blue, and Congo Red Dyes onto CuO/C Nanocomposites Synthesized via Vitex Negundo Linn Leaf Extract. Curr. Res. Green. Sustain. Chem. 2021, 4, 100161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokić, K.; Dikić, J.; Veljović, Đ.; Jelić, I.; Radovanović, D.; Štulović, M.; Jevtić, S. Preparation and Characterization of Hydroxyapatite-Modified Natural Zeolite: Application as Adsorbent for Ni2+ and Cr3+ Ion Removal from Aqueous Solutions. Processes 2025, 13, 818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prokić, D.; Vukčević, M.; Mitrović, A.; Maletić, M.; Kalijadis, A.; Janković-Častvan, I.; Đurkić, T. Adsorption of Estrone, 17β-Estradiol, and 17α-Ethinylestradiol from Water onto Modified Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes, Carbon Cryogel, and Carbonized Hydrothermal Carbon. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 4431–4445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrew Ofudje, E.; Sodiya, E.F.; Olanrele, O.S.; Akinwunmi, F. Adsorption of Cd2+ onto Apatite Surface: Equilibrium, Kinetics and Thermodynamic Studies. Heliyon 2023, 9, e12971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ofudje, E.A.; Adeogun, I.A.; Idowu, M.A.; Kareem, S.O.; Ndukwe, N.A. Simultaneous Removals of Cadmium(II) Ions and Reactive Yellow 4 Dye from Aqueous Solution by Bone Meal-Derived Apatite: Kinetics, Equilibrium and Thermodynamic Evaluations. J. Anal. Sci. Technol. 2020, 11, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vukcevic, M.; Pejic, B.; Pajic-Lijakovic, I.; Kalijadis, A.; Kostic, M.; Lausevic, Z.; Lausevic, M. Influence of the Precursor Chemical Composition on Heavy Metal Adsorption Properties of Hemp (Cannabis Sativa) Fibers Based Biocarbon. J. Serb. Chem. Soc. 2017, 82, 1417–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Işıtan, A. Sustainable Adsorption of Amoxicillin and Sulfamethoxazole onto Activated Carbon Derived from Food and Agricultural Waste: Isotherm Modeling and Characterization. Processes 2025, 13, 2528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, S.I.; Alsebaii, N.M.; Al-Ghamdi, A.A.; Aldahiri, R.H.; Alzahrani, E.A.; Hafeez, S.; Oh, S.; Chaudhry, S.A. Fe3O4/BC for Methylene Blue Removal from Water: Optimization, Thermodynamic, Isotherm, and Kinetic Studies. Materials 2025, 18, 2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mphuthi, B.R.; Thabede, P.M.; Modise, J.S.; Xaba, T.; Shooto, N.D. Adsorption of Cadmium and Methylene Blue Using Highly Porous Carbon from Hemp Seeds. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 9659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, R.; Elsagan, Z.; AbdElhafez, S. Lignin from Agro-Industrial Waste to an Efficient Magnetic Adsorbent for Hazardous Crystal Violet Removal. Molecules 2022, 27, 1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gul, S.; Gul, S.; Gul, H.; Khitab, F.; Khattak, R.; Khan, M.; Ullah, R.; Ullah, R.; Wasil, Z.; Krauklis, A.; et al. Dried Leaves Powder of Adiantum Capillus-Veneris as an Efficient Biosorbent for Hazardous Crystal Violet Dye from Water Resources. Separations 2023, 10, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.-T.; Shih, M.-C. Kinetic, Isotherm, and Thermodynamic Modeling of Methylene Blue Adsorption Using Natural Rice Husk: A Sustainable Approach. Separations 2025, 12, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, M.T.; Alazba, A.A.; Shafiq, M. Successful Application of Eucalyptus Camdulensis Biochar in the Batch Adsorption of Crystal Violet and Methylene Blue Dyes from Aqueous Solution. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Supelano, G.I.; Gómez Cuaspud, J.A.; Moreno-Aldana, L.C.; Ortiz, C.; Trujillo, C.A.; Palacio, C.A.; Parra Vargas, C.A.; Mejía Gómez, J.A. Synthesis of Magnetic Zeolites from Recycled Fly Ash for Adsorption of Methylene Blue. Fuel 2020, 263, 116800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemdjien, L.; Tchakounte, A.; Lenou, I.; Tome, S.; Kede, C. Optimization of Synthesis of a Geopolymer Based on Laterite/Beer Bottles Composites for Adsorption of Methylene Blue in Aqueous Solution. Desalination Water Treat. 2025, 322, 101189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurniasih, M.; Aprilita, N.H.; Roto, R.; Mudasir, M. Modification of Coal Fly Ash for High Capacity Adsorption of Methylene Blue. Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng. 2025, 11, 101101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.P.; Basant, A.; Malik, A.; Jain, G. Artificial Neural Network Modeling of the River Water Quality—A Case Study. Ecol. Model. 2009, 220, 888–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).